Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 92

June 19, 2019

5 Ways to Ensure Readers Don’t Abandon Your Book

Photo credit: Pensiero on Visualhunt / CC BY-NC-ND

Today’s guest post is by H.R. D’Costa, an author and writing coach specializing in story structure and story stakes.

Book abandonment.

Yep, it’s a thing. The scenario looks like this:

Readers discover your book, perhaps by browsing the categories on Amazon, perhaps through a Bookbub ad. And with so many enticements—

steeply discounted price

mouthwateringly gorgeous book cover

compelling book description

—they click the buy button. But after the first chapter, the third chapter, or even the first half of your book, they abandon your novel—never to return again.

Therein lies the fatal flaw of the marketing tactics mentioned above. While they’re essential for readers to discover your book, they can’t get readers to finish your book. And if readers don’t finish your book, then all your savvy marketing plans are for naught.

On the other hand, if you create the kind of emotional experience that readers crave, they won’t be able to put your book down—and you’re one step closer to igniting word of mouth that can help you effortlessly sell your novel, month after month, year after year.

That’s why improving your craft is an essential component of your marketing strategy (although, at first glance, it might not seem like it). But what storytelling elements should you focus on?

I humbly suggest an element that might not even be on your radar: the stakes, or the negative consequences of failure. Without stakes, your protagonist doesn’t have a reason to keep on pursuing his goal. Readers may question why he perseveres despite the obstacles mounted against him. Once readers question the plot, they’ll disengage from your story. And once they disengage…well, book abandonment becomes almost inevitable.

With stakes, however, the protagonist does have a reason to continue—and there’s no cause for readers to disengage. Not only that, stakes put readers under tension. That’s because they don’t know how your protagonist is going to avoid those nasty negative consequences. The only way to relieve that tension is to—wait for it—finish your book.

Indeed, when you wield stakes wisely, you’ll create the emotional intensity that’ll make your book impossible to put down. The plotting tricks here (adapted from my writing guide Story Stakes) will show you what to do.

As a quick overview, here they are:

If a multitude of people will suffer if your protagonist fails, focus on a few of them.

Build a subplot around the stakes.

Have your protagonist put some skin in the game.

Bind your protagonist’s failure to the sting of regret.

Take the personal stakes out of play last.

Before we dive in, a few caveats:

This article doesn’t really discuss different types of story stakes. If you’re looking for something like that, here’s a convenient, printable list of 11 types of story stakes.

I tend to use masculine nouns and pronouns (you may’ve noticed that already). But rest assured, as a female, I know females make amazing protagonists.

Because films are more universal, I generally use examples from films to illustrate my points. However, the principles behind the examples apply equally as well to novels.

The tips in this article are suitable for novels with elements of physical danger (i.e. thrillers, mysteries, etc.). In other words, the tips are less applicable if you write rom-coms, but you can still save them for future reference!

Okay, with those caveats sorted, let’s get to it.

1. If a multitude of people will suffer if your protagonist fails, focus on a few of them.

The fate of a nation. The fate of the world. Objectively speaking, these are high stakes indeed.

However, it might not feel that way to readers—not at an emotional level. That’s because these stakes are too vast to grasp. Subjectively, these stakes might not generate much emotional weight. As a result, the reader experience can become more of an intellectual exercise, and your story may not contain the emotional intensity you anticipated.

That’s why, if you want readers to invest in your novel, you should draw their attention to the plight of a few individuals within the larger group comprising the stakes.

The connection between readers and this subset creates a conduit for reader emotion to flow through, and thus carry over to the group as a whole. This way, the stakes remain high, and at the same time, they feel high.

To accomplish this, make sure readers get a chance to spend time with the stakes (the subset, to be clear) at the beginning of your novel. Give readers the opportunity to get to know and like the stakes—the same way you give readers an opportunity to know and like your protagonist. To create such an opportunity, consider starting your story with a celebration.

In the film adaptation of Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, the fate of all Middle-earth hangs in the balance. But audiences worry about the effect of evil on one area in particular: the Shire. Moreover, the connection between audiences and the Shire is formed by depicting preparations for a special birthday party.

Likewise, in Braveheart, William Wallace wants to free all of Scotland from the tyranny of King Edward I. But audience investment in this worthy goal emerges, in part, from their connection to Wallace’s own village—which they get to know through scenes depicting a wedding.

Once you’ve created a bond between readers and the stakes, you’re not home free yet.

If you don’t take the appropriate measures, this bond can slowly wither. Consequently, readers won’t be as emotionally invested in the climax, whose outcome will determine what’ll happen to the stakes.

To prevent this, take the time to fortify the reader-stake bond. Periodically remind readers about the stakes throughout your novel.

Just to be clear, the same techniques should be used even when your protagonist is only charged with saving one or two people (as opposed to a multitude). Forge a bond between readers and the stakes, then maintain it.

2. Build a subplot around the stakes.

Need to get your novel to the right length? Subplots are quite handy for that. You accrue even more benefits when you build a subplot around the stakes. That’s because doing so also enables you to accomplish the aims discussed above, namely:

forming a connection between readers and a subset of the stakes

bringing the stakes to the forefront of your story in a natural way (i.e. subplots = stake reminders)

To build a stake-based subplot, it might be useful to view it according to Scott Myers’s definition of the small story:

I read a lot of scripts, and one recurring issue I find, regardless of genre, is a lack of emotional resonance. There can be all this huge stuff going on in the plot, literally in a sci-fi story at the scale of blowing up an entire planet, but if there aren’t points of connection for a script reader to the story’s characters, where we actually feel something authentic for them, then the effect can be so much noise.

That’s why I have this writing mantra: Substantial Saga / Small Story. That is whatever the big story is, what I call the Plotline, there have to be some intimate subplots and dynamics going on which engender a human connection between the reader and the characters.

To show you how you might integrate a small story into your own novel, let’s play around with the plot of Wonder Woman. In it, moviegoers got the “substantial saga” of World War I. But they didn’t get the “small story.” Let’s fix that.

In the film, Diana and Steve rescue a village which, despite their heroic efforts, is ultimately destroyed. Poignant stuff, to be sure. But now imagine how much more poignant it would be if a subplot were built around this village.

For example, the film could introduce this village to audiences long before Diana and Steve arrive there, and highlight the attempts of one or two villagers to survive amidst the chaos.

As in the actual film, the outcome of the war would hinge on Diana and Steve’s actions. But in this alternate version, audiences would feel the effect of those actions through their connection to the villagers.

Furthermore, because audiences have gotten to know the villagers through the small story, when Diana and Steve finally arrive on scene, audience joy over the rescue of the village is going to crest higher. At the same time, audience pain over the village’s ultimate destruction will cut deeper.

3. Have your protagonist put some skin in the game.

It’s a basic truth: By and large, readers invest more in your protagonist than in any other character. So when you use this plotting trick and make your stakes personal—when your protagonist’s potential failure directly affects him—your story will have greater emotional intensity. It’ll be even more difficult to put down.

Returning to The Fellowship of the Ring, the Shire is home to Frodo, one of the central protagonists. Because audiences have invested in him, the potential destruction of the Shire carries more emotional weight than if it were a place that wasn’t so near and dear to Frodo’s heart.

However, “skin in the game” means you usually have to go beyond a protagonist’s connection to a place and focus on his connection to a person. Someone close to him—

love interest

child

mentor

friend

—will die (or suffer other grave consequences) if the protagonist fails to achieve his goal.

At this moment, you might be recoiling from this idea. Indeed, many writers resist it because it occurs too often. That’s their argument, at least. But if you’ve done your job well—and readers have emotionally invested in your protagonist as well as in the stakes—then readers will be too engrossed in your novel to compare it to something else.

Think about the ending of Ant-Man. I doubt any members of the audience were thinking, “I can’t believe the hero’s daughter was taken captive by the bad guy.” The same exact thing happened at the end of Live Free or Die Hard.

No, I’d wager audience members were thinking, “How in the world is Scott going to save Cassie in time?”

If you still remain unconvinced, well, maybe you can try out the next plotting trick instead.

4. Bind your protagonist’s failure to the sting of regret.

Here’s how this works: Although your protagonist has a dream, he hasn’t been pursuing it. He’s all talk (or thought), no action. Then the inciting incident comes along, bringing with it a new goal for the protagonist to pursue, the overall goal driving the main plot of the story.

Now, the protagonist can’t pursue his dream at all. That’s not an option anymore. Instead, he must save the world, save the day—whatever the overall goal may be. And now, failure carries double meaning.

It doesn’t just mean that the day won’t be saved. It also means that the protagonist, having lost all chance of pursuing his dream, will be consumed by regret. This, you’ll note, makes a bad situation feel even worse, which is why this trick is so effective at adding another emotional layer to your story.

To see it in action, study the film Collateral. If Max fails to outwit a hit man, Max will die, filled with regret. However, if Max succeeds, he’ll not only survive the night; he’ll also be able to start the limo business he has always dreamed about.

At first glance, the limo angle might not seem like it contributes much. But think about it. This dream, along with the specter of regret that accompanies it, is much more relatable than dealing with a psychopathic hit man. In other words, it creates another pathway for audiences to connect to the story, thereby supercharging their experience.

That’s not all. If you employ stakes of regret in your own novel, you won’t just be heightening its emotional intensity. You also might motivate your readers to take action and pursue their own dreams—before it’s too late.

5. Take the personal stakes out of play last.

Whenever your story involves general stakes and personal stakes, be careful about when you take the stakes out of play, i.e., bring them to a place of safety.

If you take the personal stakes out of play first (e.g. the protagonist rescues her daughter—and then everyone in her daughter’s summer camp), your story ending will be anticlimactic.

If you take the general stakes and the personal stakes out of play at the same time (e.g. the protagonist rescues everyone at summer camp, including her daughter), your ending won’t be anticlimactic (not for this reason, at least).

However, you will be missing out on an opportunity to elicit even more emotion from your readers.

To take advantage of this opportunity, take the general stakes out of play BEFORE the personal stakes (e.g., the protagonist rescues her daughter’s campmates, and then her daughter). Notice, to accomplish this, you’ll probably have to come up with a credible way to separate the personal stakes (in this case, the daughter) from the general stakes (the other girls at summer camp).

But why bother?

Remember, readers are emotionally aligned with the story’s protagonist. Consequently, they’re going to have a stronger emotional response when they see the protagonist rescue her daughter than when they see the protagonist rescue the other girls. By virtue of contrast, the latter half of the climax is going to feel escalated compared to its initial half. As a result, the reader experience—already intense—is going to feel even more intense.

Confession: This plotting trick isn’t like the others. Whether you use it at the climax or not, readers aren’t likely to put down your novel at this point. They’ve come too far to throw in the towel now.

Even so, the tactic is still valuable to apply. With it, you’ll prove to readers that you know how to prolong the tension and deliver a roller-coaster ride, right up until the last minute. So when they eventually walk away from your story—not because they’ve abandoned it, but because they’ve reached THE END, and that’s what they’re supposed to do—they’ll eagerly search for the other books you’ve written.

A happy ending, in more ways than one!

Note from Jane: For more tips on how to use story stakes, check out Story Stakes by H.R. D’Costa.

June 17, 2019

Writer’s Block Is a Gift. Here’s Why.

Photo credit: magical-world on Visual hunt / CC BY-SA

Today’s guest post is by writing and creativity coach Julia Roberts (@juliadecodes).

Despite its infamy for robbing people of their careers, writer’s block can give you a powerful gift—insight into your own relationship to the creative process.

Writer’s block is nothing more than a drain of energy when you come to a certain part of the process, and we all have natural ebbs and flows of energy as we move a project through its paces. So, think back. What part of your project were you on when you felt stymied?

Here are four possibilities, each tagged with a creative thinking style that we’ll discuss. Does one of these forms of writer’s block describe you?

Maybe you love the research and inquiry phase, but get stuck when it’s time to write. (Clarifier)

Maybe you have so many ideas, it’s hard to determine which idea is best for you. (Ideator)

Maybe you can’t let it go; it needs a little more polishing. (Developer)

Maybe you dash it off but later find sloppiness and errors in it, after getting it out into the world. (Implementer)

Yes, there is an easier way

When we think back to an episode of writer’s block—and mostly we don’t—we remember vats of ice cream or too much wine. We don’t remember the cause because that is what these coping mechanisms were designed to do—keep us from noticing a failing that is too painful to acknowledge. But take a look at the four possibilities above once more. Does one description fit you better than the others?

Clarifier – You like to get it right.

Ideator – You like ideas. You live in the possibilities.

Developer – You like to get it perfect.

Implementer – You like to get it done.

When you have a strong propensity for one phase of creativity—clarify, ideate, develop, or implement—you often lose energy and even obstruct creative progress in another phase. This creative phase and creative process research are based on the work of Dr. Gerard Puccio, the Department Chair and Director for the International Center for Studies in Creativity at Buffalo State College, part of the SUNY system. To test subjects for their creative thinking preferences, Dr. Puccio designed an assessment called Foursight.

My big learn

I took the Foursight assessment during my Master’s program at BuffState, and I had an enormous “a-ha” about my creative thinking style. I knew I had very high energy and skill for ideation. I’d been a professional brainstormer for most of my adult life. I’d go in, sit in a room with candy and toys, and blatt out ideas on one marketing project after another.

I could do it all day long. And I was in high demand and well paid for it. So, it was no surprise when my Foursight profile showed me as a high Ideator.

What was revealing is that I profiled as a very low Clarifier. I prefer to jump right in and not ask many questions. Furthermore, I was such a low Clarifier that I actually obstructed clarification. The very help I needed most, I didn’t value, and didn’t invite into my process. I got ideas, loved ideas. I lived in the idea zone where anything is possible. Clarity just harshed my thrill, right?

Though I couldn’t see it, what was happening was when I didn’t clarify, I didn’t commit. Or I’d commit to the wrong idea and just hop to a new one when the first one petered out. There’s always more ideas, right? I never took into account the amount of time lost because I hadn’t clarified or chosen my ideas thoughtfully.

I didn’t finish things I started because of the lack of commitment to any one idea. I know I’m creative, but I wasn’t managing to create, i.e., produce, enough of my ideas, and I didn’t know why. It was frustrating and sort of embarrassing. The Foursight assessment helped me see precisely why.

The Creative Selfie

Because that insight helped me immeasurably, I feel compelled to help writers see themselves in relation to their creative process strengths and struggles, and provide tools and support for areas where they need to bridge from one process phase to the next to bring their ideas to fruition. (I developed the Creative Selfie that I offer to all of my new clients; it includes the Foursight assessment plus two other tests to help you see quite clearly your creative gifts, and gaps, in 360 degrees.)

Consider how, armed with self-knowledge, you might be able to eradicate, prevent, prepare for, and survive writer’s block with your project intact. I learned to Clarify. In fact, I learned to value clarifying. I didn’t stomp my feet and roll my eyes when people tried to help me clarify. And with this one safeguard in place, I quit jumping from idea to idea. My life stopped going in circles—start, stop, start again—and started going in a straight line as my ideas were completed. I accumulated work, a foundation, on which to continue building.

Parting advice

Writer’s block can offer a powerful, even life altering gift of discovering your own style of creative thinking. Once you know, you can make choices. You can live only within your strength and hand off the rest of the process to your minions (which is what I did successfully as a professional brainstormer), or you can seek help and tools for your gaps.

The pain of writer’s block is not just in the actual work stoppage but even more in the denial and fear that result, that leave us embarrassed, ashamed, helpless and maybe eating brownies in secret.

The pain of writer’s block is not just in the actual work stoppage but even more in the denial and fear that result, that leave us embarrassed, ashamed, helpless and maybe eating brownies in secret.

I hope you can look at your last writer’s block with more compassion and insight now, and separate the work stoppage from the stories you told yourself about why you stopped writing. Maybe you’re not lazy, crazy, stupid, or lame. Maybe you’ve just entered a creative phase that is not in your wheelhouse. There’s help for that.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, take a look at Julia’s Powerful Help for Stuck Writers (free with your email address).

June 12, 2019

Indiana in July: Beginner and Advanced Workshops for Writers

In late July, I’ll be returning to my home state of Indiana to offer two workshops.

July 27: Author Platform and Career Development Bootcamp

As part of the Midwest Writers Workshop, I’m offering a 6-hour intensive session for published (or nearly published) authors.

Professional authors always have one thing in common: they seek an audience for their work, and almost always a bigger audience. Having a strong and growing readership helps turn writing into a sustainable, full-time career. But what leads to readership growth? And what can you do, especially without a publisher’s help (or a large bankroll), to encourage that growth and launch your next book successfully?

This full-day bootcamp for career-minded authors offers hands-on guidance and discussion to help you better develop a strategic launch plan for your work, and identify and grow a readership over the long term, whether you’re traditionally published or self-published.

Location: Muncie, Indiana (Ball State)

Learn more about the bootcamp

Register at MWW ($155, includes lunch)

July 28: How to Get Published: Traditional, Self, and Everything in Between

In this 4-hour master class, in partnership with the Indiana Writers Center, I discuss everything you need to know about how book publishing operates today, in plain English, to help you understand the pros and cons of every major publishing path available. I’ll cover New York traditional publishing and what projects are well-suited to being represented by literary agents; the capabilities of mid-size publishers and independent publishers; how to evaluate small presses, micro-presses, and digital-only presses; what “hybrid” publishing is (or thinks it is) and how to evaluate such companies; and all forms of self-publishing and e-publishing practiced today.

Location: Indianapolis area / Marian University

Learn more and register at IWC ($100 for non-members)

Have questions about whether a session is right for you? Comment below or ask me directly—I want you to make the right investment of time and money, and my classes aren’t right for everyone. Contact me here.

June 10, 2019

The Challenge of Book Cover Design

Photo credit: Philippe Put on Visualhunt.com / CC BY-ND

Some of the most bitter disagreements I’ve witnessed in book publishing (aside from contract disputes) are about title and cover design.

At the mid-size publisher I once worked for, we had two catalog seasons (spring and fall) and thus two (very extended) rounds of title and cover design meetings per year. The marketing department was in charge of administrating the process, and it was my least favorite meeting. Conversations would go in circles, everyone’s opinion was more or less equal, and even the smallest differences could upend the process as it neared the finish line. (This is one reason why authors’ publishing contracts rarely give them approval over title and cover—only consultation.)

In my latest column for Publishers Weekly, I discuss an aspect of the cover design process that has become popular among traditional and self-published authors alike: social media feedback.

Unfortunately, as you’ll see, I think sharing your cover on social media to solicit meaningful direction is like throwing a bomb into the process. Read: Don’t Crowdsource Your Cover Design.

June 3, 2019

How I Caught a Publisher Unexpectedly

Photo credit: Traveloscopy on Visualhunt / CC BY-ND

Today’s guest post is by Nancy Jorgensen (@nancyjorgensen), co-author of Go, Gwen, Go: A Family’s Journey to Olympic Gold.

My book is published by a company I never heard of and didn’t query.

After years of writing, workshopping and revising our book, my co-author (who is also my daughter Elizabeth) and I marketed it to agents and publishers. It was the story of Elizabeth’s sister, Gwen, a CPA turned Olympic triathlete.

In our first round of submissions, large publishers and established agents concurred: Sports stories are a tough sell even when the athlete is high profile. Our memoir about a little-known sport, narrated by the Olympian’s mother and sister, gained little traction. Several suggested we rewrite the book, as ghostwriters, in the Olympian’s voice. But our book was more than an Olympian’s story—it was a family story. We stood by our concept.

In a second round of submissions, we received an offer to publish, laden with compliments about our writing. But on closer inspection, we realized we had mistakenly submitted to a vanity press. We declined. Then, a lawyer spotted us on Twitter and pressured us to pay him a large sum in return for “contacts.” We declined him, too.

In our third round of submissions, a publisher sent this reply,

Thank you for your submission of Go, Gwen, Go. Unfortunately, at this time we are unable to publish your title. We feel that your title is not the best fit for our publishing line as we typically do not publish triathlon titles. … We wish you the best success moving forward and hope you find the perfect fit in a publisher. Thank you for your time and consideration. … However, we distribute a publisher that publishes many books on marathons and triathlons. Would you like me to forward your query to them?

Although discouraged, and growing less optimistic with each rejection, we encouraged the editor to forward our query. We also investigated the publisher that specialized in our topic, wondering how we had missed them in our own research. It turns out they’re a European company and so weren’t included in our predominantly domestic lists.

Within a week, Meyer & Meyer Sport, the largest sports publisher in Europe, replied with an offer to publish.

In preparation for submission, we had scoured online sites, bought books that catalogued agents and publishers, paid a coach to improve our query letter and research—and missed a major publisher interested in our book.

But our hard work was valuable. Because of our wide-ranging queries, we piqued the interest of an editor who knew an editor—someone in the United States who knew someone in Germany, someone who saw promise in our idea and took the initiative to pass along our work. A final deal emerged out of our campaign.

But our hard work was valuable. Because of our wide-ranging queries, we piqued the interest of an editor who knew an editor—someone in the United States who knew someone in Germany, someone who saw promise in our idea and took the initiative to pass along our work. A final deal emerged out of our campaign.

Of the 75 contacts we made, many queries met no response. Only four publishers requested the full manuscript. One agent conversed via email, offering suggestions and support but no representation.

As my daughter and I work on our next book, we use lessons learned from our first collaboration. Although queries and marketing are months away, our first overture will be to Meyer & Meyer Sport. If they don’t have a place for our title, we plan to cast an even wider net than our first one. The more waters we troll, the better chance an agent will bite or direct our idea to another big catch.

May 30, 2019

9 Ways (and 2 Rewards) of Marketing Your Own Book

Photo credit: Sharon Drummond on VisualHunt.com / CC BY-NC-SA

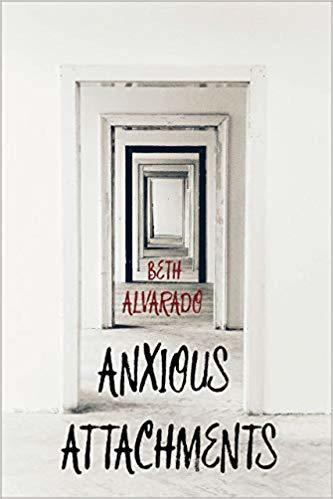

Today’s guest post is by writer Beth Alvarado.

When I found a good home for my essay collection Anxious Attachments, I knew I would have to take an active role in marketing. After all, while Autumn House Press is a fine press, it’s also small and independent, with no marketing department and limited funds. I published both of my earlier books, Not a Matter of Love and Anthropologies, through university presses—also wonderful, prestigious presses that don’t have marketing departments.

The main problem, however, was me: I knew nothing about marketing and, honestly, didn’t realize I would need to do it.

Because university and small presses published all three books, I can describe to you what those publishers are able to do with their limited resources:

They send emails and your book to their own lists, including reviewers, as well as to a list of people and possible reviewers you provide.

They nominate your book for prizes.

They might advertise your book in magazines or online venues.

They might help you network with other writers who might promote your book.

They might do a book launch, if you can travel to their site and they’re launching a spring or fall list.

They might help you set up readings, but you would have to pay for your own travel.

While this isn’t a marketing campaign like one you might get from a big press—which would only occur IF your book happened to be one of the books it wanted to push—it does help you cover all four areas outlined in Jane Friedman’s post, A Book Launch Plan for First-time Authors with No Online Presence:

Market and promote to the people who know you (existing readers or fans, even if there are only a couple).

Encourage existing readers and fans to share your book with their network.

Get influencers to help spread the word.

Market to strangers or readers who don’t know you yet—but have demonstrated interest in work similar to yours.

I soon recognized I would have to fill the marketing gaps myself. It’s not that hard; it just takes time. And the rewards amount to more than just book sales.

The first two steps are definitely easier to take than they used to be even ten years ago. Email and social media go a long way towards notifying readers and helping you network so you can set up readings and get reviews. With my first book, I created a website. For my third, two friends completely updated and revamped it.

With my second book, I’d done one very important thing: Because Anthropologies was a lyrical memoir and very unusual in structure, I decided teachers of creative writing were important influencers, so I sent a copy of the book out to every teacher I thought might want to teach it. I’d been training teachers at the university level for eleven years, and I’d been in the job market, meeting faculty at interviews. So I sent quite a few copies to this network, each with a personal note, reminding the recipient about when we’d met. I knew that course adoptions would be great and, that if teachers liked the book, they would tell other teachers.

This must have worked because the book has been taught by people I’ve never met and those to whom I sent a copy. I had hoped that some of those teachers might also write reviews, a gamble that didn’t pay off but could have.

Steps 3 and 4 on the list are the harder, of course—reaching influencers and strangers. Just how do you do that?

1. Hire a publicist

By the time the third book, Anxious Attachments, was accepted for publication, I knew at least two people who had hired publicists for their books. One had done an excellent fund-raising campaign to hire her publicist, and she probably got more online exposure from the fundraising than she did from the publicist. The second friend had very good results from a partial campaign. I interviewed both friends to find out what they recommended, and I read a few articles about hiring publicists, including a really helpful entry, again, on this site: Choosing a Publicist: Ruling Out and Ruling In. Then, I interviewed a few publicists.

I ended up hiring the publicist who would do a partial campaign, partly because that was all I could afford, partly because my friend recommended him, and partly because he’d worked in small literary houses for ten years in New York City, with contacts possibly receptive to my work. He coordinated with my publisher to avoid duplicating efforts, and my publisher, of course, had my list of contacts for reviews.

I ended up hiring the publicist who would do a partial campaign, partly because that was all I could afford, partly because my friend recommended him, and partly because he’d worked in small literary houses for ten years in New York City, with contacts possibly receptive to my work. He coordinated with my publisher to avoid duplicating efforts, and my publisher, of course, had my list of contacts for reviews.

Both of their lists increased my potential influencers exponentially, but, as it turned out, the only reviews so far have come from people on my own list. This doesn’t mean the publicist’s partial campaign was ineffective, in my view. There may be reviews yet to come, and for some contests or prizes, books cannot be submitted or nominated. Instead, reviewers out in the world select books.

The more reviewers see your book, the more likely it is to be selected. Any campaign is a matter of increasing your exposure, and the publicist has helped me do that.

2. Make readers out of strangers

As for reaching strangers or new readers, again I bought boxes of my books and gave them away at readings, asking people to post a review on Amazon or Goodreads in exchange. I gave one to a perfect stranger in a restaurant who commented on my book because I had it sitting on the table. But so far there are only seven reviews on Amazon and five on Goodreads. I’ve received many more emails than that from readers, those I know and those I don’t, and people have posted on Facebook. All of that is gratifying, but it doesn’t help me reach those people under item #4: strangers who don’t yet know my work. I am trying to encourage people to post, though it feels self-serving.

So here are a few things I’ve done—that I feel good about—to reach new influencers and readers.

3-6. Make events connected to but not “about” the book

3. For instance, a small press sponsored a salon called “Matters of Life and Death,” where my friend and I each read short passages from our recent books and then facilitated a conversation with other people about those moments where you realize you are in the presence of mysteries you don’t understand. There were at least 40 people there, over half of whom I’d never met. I sold all of the books I’d brought, so did my friend, and it was a moving and enjoyable evening.

4. For the same small press, I held a fundraiser with five other women, a kind of Moth storytelling event, where we told stories about motherhood, riffing off earlier essays that we’d had published on the press’s blog. There were probably 100 people at that event, most of them unknown to me. So again, I reached readers who otherwise would never have heard of me and, in preparing, challenged myself in ways that were totally scary and rewarding.

5. At a bookstore, I arranged an “in conversation with” event with another woman who’d written an essay collection. Together we discussed recent essay collections by women and read from our own. The bookstore was interested in sponsoring this event because it was different from the usual readings where, typically, a small number of the reader’s closest friends show up.

6. I also hosted a more conventional reading but, again, with another writer and we were both reading about borderlands issues. Again, we both sold out.

These experiences have taught me that finding an unusual approach will attract both venues and an audience. I especially like events that also lift other writers. And so, as I go on to set up future events, I’ll apply what I’ve learned. I like approaching marketing sideways. But how could I do more of this? And how could I do it online?

This is where my publicist really helped me with ideas.

7. Write a craft essay

When we weren’t getting the reviews that we’d hoped for, he asked if I could write a craft essay. Fortunately—or not—my daughter had just opened my book to a random place, a scene she found objectionable. This resulted in a long conversation where she told me I was no longer allowed to quote her without her permission, and that conversation led me to write an essay called “When Your Daughter Refuses to Be in Your Essay.” The publicist was able to place it on LitHub, just in time for Mother’s Day. Because this essay was funny but conflicted, it generated many responses and reached quite a few new readers.

8. Design a playlist

Next, he asked if I could write a playlist to go along with the essay collection because Largehearted Boy, a blog about music and literature, publishes playlists by authors in its Book Notes section. This was quite an undertaking for me because the events in my book take place over the 40 years of my marriage to my late husband, Fernando. I was reminded of everything from opera to mariachi music to seventies rock and roll to the indies rock my children loved. I found myself listening late into the night. My playlist turned out to be an essay in its own right, about 3,000 words.

After I had a draft, I read the instructions in the publicist’s email: “one track, explain the track,” so I whittled my list and my essay down to a manageable length. The entry for the final essay in the collection is: “If I were to make a playlist for Fernando, it would be filled with guitar music. Eric Clapton, George Harrison, Duane Allman, Jerry Garcia, Santana, B.B. King, Steve Winwood, Mark Knopfler. And Hendrix. Of course, Hendrix. Especially ‘Little Wing.’ If, when someone dies, the person we were inside of them also dies, then this is the girl I am mourning when I mourn Fernando.”

Again, something I undertook to promote the book turned out to be valuable in and of itself, and my book was exposed to a number of new readers, 150 of whom liked the playlist.

9. Write a review essay

The third thing I’ve written with the sole intent of promoting my book is a review essay. My publicist asked me to write a few reviews, but I ended up writing an essay tentatively called “What is it? A memoir in essays? A collection?,” wherein I consider ten recent books by women essayists, 12 when I add my own to that list. My own struggles as a writer have often been about structure, and so I was interested to see how other writers structured their collections.

I didn’t want to write critiques, as some reviewers do, but instead an analysis of others’ projects: How is this working? What are its strengths? In what ways is it unique? I learned a lot by articulating, in this essay, the differences between a “memoir in essays,” “an essay collection,” and “a book-length essay,” something I would not have done otherwise and that will be, I’m sure, valuable when I go to market other projects. And, in the meantime, I am filling the role of influencer for others’ work. At least, that is my intent.

Marketing and creativity

In short, like all of you, I have limited time, so doing this marketing has meant I haven’t had time to write anything brand new. However, I’ve realized that, through marketing, I’m laying the foundation for my story collection, Jillian in the Borderlands, which comes out next year. In the process, I’ve learned two crucial things about the role of marketing in a writer’s life:

Marketing can become a part of your creative life, adding fuel and clarity to your writing.

Whether you’re also promoting others’ work or simply making new connections, marketing can help expand your literary community.

The line between creating something and selling it doesn’t have to be a hard boundary, and crossing that line need not be painful. Instead, let it be a zone of creative exchange supporting your work and its readers.

May 29, 2019

4 Elements of Narrative That Anyone Can Learn

Today’s guest post is excerpted from the book Seven Steps to Confident Writing. Copyright ©2019 by Alan Gelb. Printed with permission from New World Library.

Narrative is a form that can be learned, like a dance move or a golf swing. I break down narrative into four elements: The Once, The Ordinary vs. the Extraordinary, Conflict and Tension, and The Point. When you understand how these elements act and interact, you’ll have a much stronger sense of how to tell a story.

1. The Once

One of the first problems a writer must figure out when undertaking a narrative is how to handle time. After all, no writer (or reader) has all the time in the world. Every single narrative ever told, from a knock-knock joke to Gone with the Wind, has had to deal with that issue. Those that have survived have dealt with it successfully.

The Once is that specific point in time at which your narrative is set — and narratives always have a beginning point. Think of fairy tales and “Once upon a time.” Think of the Bible and “In the beginning.” Think of Moby Dick and “Call me Ishmael.” Think of The Color Purple and “You better not tell nobody but God.” The beginning of any piece of writing is usually the most difficult part. You need to set a mood and a tone that will invite your reader in, and that is a challenge.

Sometimes all you need to break through the challenge of The Once is some serious pruning at the start of your piece. Maybe all you have to do, in fact, is lop off a chunk. I see this kind of problem and resolution all the time when I work with college applicants on their essays. They’ll decide to write a narrative about their two-week trip to Louisiana to build houses with Habitat for Humanity, let’s say, and they’ll start in their room, back in New Hampshire, as they’re packing their bags. Or they’ll start on the plane to New Orleans. Or they’ll start on the tarmac at the Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport. By the time we finish our work, all those openings have gone away.

Sometimes we have to be very patient until we get The Once just right. The reason for that is because it is not unusual for writers to not really know or understand what a piece is about until they are well into it. “Ah! Now I see that this piece is not just about baseball; it’s really about my relationship with my father!” And then, when that understanding clicks in, a writer can go back and readjust the time accordingly. The parts of the narrative that don’t work toward the real theme of the piece can be pruned back or discarded altogether, leaving more room to support the theme that has now been identified.

The college applicant who is writing about building houses in Louisiana cannot expect a reader to be satisfied with a flabby travelogue. That writer must locate the meaning of her story. Is it about being thrown in with people she might never have met otherwise? Is it about overcoming a feeling of ineptitude that has accompanied her all her life? Is it about escaping her overprotective family and experiencing the exhilaration of being on her own? Any or all of those could be worthy themes to explore, but once the writer decides which of those is the real story she wants to tell, then she can begin to tailor the time to support that story. As I say, writers need to be patient, because often that kind of insight does not emerge until the drafting process is well underway.

2. The Ordinary vs. the Extraordinary

Another essential challenge that a writer faces when constructing a narrative is to figure out the “extraordinary” thing in the story that is going to arrest the reader’s attention. However, the extraordinary thing does not have to take place at the beginning of the story. But whatever choice you make, you must locate the extraordinary thing that either ignites or “turns” your story.

3. Conflict and Tension

The “extraordinary” event that ignites or turns the narrative does not take place in a vacuum. It needs to be connected to a second frame that shapes your narrative, and that frame has to do with conflict and tension.

The main reason we all read, go to a movie, watch TV, or even play video games is to see how our heroes resolve conflict. Whether that hero is Hamlet or Arya Stark from Game of Thrones, we want to see how people (or characters) resolve conflict, that is, how they live, as life is essentially about conflict and how we resolve it. Simply put, conflict is the struggle between opposing forces. Conflicts can occur between individuals (Superman and Lex Luthor), between groups (the Montagues and the Capulets in Romeo and Juliet), between individuals and society (Josef K. and the totalitarian bureaucracy in Franz Kafka’s The Trial), between individuals and their own self-destruction (the unnamed insomniac hero of Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club), between individuals and nature (Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe), and more. Whenever you tell a story, it is imperative that you have some aspect of conflict in it (otherwise, why tell it?).

4. The Point

The last of the four elements that will play a critical role in your narrative is The Point. By the end of any given narrative, readers should come away with an understanding of why they have been asked to read it. They should have a sense of having come away with something real, whether it is an insight or a feeling, a laugh or a cry, a sense of indignation or empathy, or any number of other reactions. They should know The Point of what they have read.

Sometimes The Point of a narrative jumps out and shakes you by the hand. Take the fables of Aesop, with which you are probably familiar. In “The Milkmaid and Her Pail,” the young woman is going to market with a pail of milk on her head, fantasizing about all the things she’ll buy when she cashes her milk in for coin. When she gives her head an impetuous toss, the pail falls to the ground, the milk is spilled, and her fantasies are dashed. The Point of the story is clearly stated in a moral (present in every Aesop fable): “Don’t count your chickens until they’re hatched.”

Sometimes The Point of a narrative jumps out and shakes you by the hand. Take the fables of Aesop, with which you are probably familiar. In “The Milkmaid and Her Pail,” the young woman is going to market with a pail of milk on her head, fantasizing about all the things she’ll buy when she cashes her milk in for coin. When she gives her head an impetuous toss, the pail falls to the ground, the milk is spilled, and her fantasies are dashed. The Point of the story is clearly stated in a moral (present in every Aesop fable): “Don’t count your chickens until they’re hatched.”

Although you may choose to explicitly state The Point in your narrative, there is absolutely no obligation to do so, and modern readers may prefer to have The Point brought home with more subtlety. There is nothing wrong with that. Writing is a two-way street, and making readers do their part of the job is completely appropriate and often quite welcome.

If you enjoyed this article, be sure to take a look at Seven Steps to Confident Writing by Alan Gelb.

May 28, 2019

Identifying the Best Self-Published Books by State: The Indie Author Project

Longtime authors in the self-publishing community may recall the library program known as SELF-e, launched in 2015. It’s a partnership between Library Journal and BiblioBoard to make self-published ebooks available to libraries nationwide. Any author can submit their work for inclusion in SELF-e (at no cost); Library Journal curates what ebooks go into the national SELF-e collection. Books not selected are still accessible to local library patrons through state collections.

At the time of its launch, SELF-e sparked some controversy because it didn’t pay self-published authors for library usage. Rather, it was positioned as a marketing and discovery service aimed at helping authors build an audience of readers. Today, that is still mostly the case, although the program has continued to develop and grow—and now offers a way for authors to earn money.

This potential for payment begins first with the annual Indie Author Project contests. The purpose of these contests is to identify the best self-published fiction by state; thirteen states participate so far. Winners receive cash prizes, marketing and promotion in Library Journal, and of course print and ebook (paid) sales to state public libraries, among other benefits.

But even beyond the contest winners, SELF-e is partnering with OverDrive—the main ebook distributor for libraries—to offer payment for any ebook that is curated for SELF-e’s national collection. Details on payment for both programs will be announced this summer.

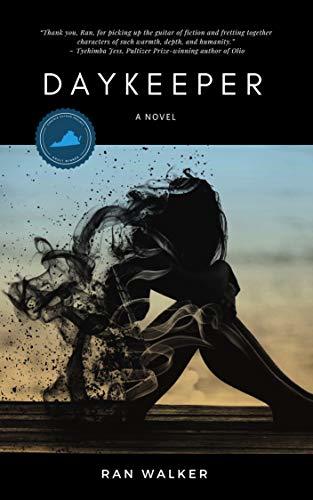

Back to the contest: This year’s national Indie Author Project winner is Ran Walker, author of Daykeeper, among many other titles. Walker has also just been awarded the 2019 Black Caucus of ALA Best Fiction Ebook.

Ran was gracious enough to make time to answer some questions about his work.

Jane Friedman: The various turns of your career fascinate me. You started out earning an English degree from Morehouse, then earned an MS in publishing as well as a degree in law several years later. You practiced law in Mississippi for a while until then becoming a creative writing professor.

Was your plan to pay the bills as a lawyer and write on the side? If so, what happened? (And how did you obtain the confidence or courage to step away from law to pursue writing full time?)

Ran Walker: When I was a lawyer, I don’t think I actually did much writing at all. It wasn’t until I completely stepped away from the active practice of law that I really began to test the waters to see if my writing was any good. At that point I didn’t have a real plan.

I knew when I left law, I was going to have to reinvent myself in some kind of way so I could make a living, but I didn’t initially know it would be connected to writing. I had always wanted to write a book, and one night I sat down in front of my laptop and began to do just that. It took me three months to complete that one. I truly believe that it was only through the writing of that novel that I became a real writer.

I began reading a variety of writing magazines and books, I got an agent and won a writing fellowship. It was at that time that I knew teaching would be the best vocation for me, as it afforded me the time to write and it allowed me to help others with their writing. Ultimately, teaching creative writing is how I have chosen to support myself.

You have a substantial body of work—sixteen books to date. I think most writers would consider you quite productive and focused, especially considering you’re a writing professor as well. Is there a routine you follow or some method you use to hold yourself accountable?

I keep hearing writers talk about having your “tail in the seat” to get your writing done. I think for me it’s a bit simpler. I know what a life of “not writing when you so desperately want to” looks like. I want to leave behind a library of books when I’m gone (more than 100), so I know I have to always be writing—or at least thinking about what the next project will be.

I tend to keep two book ideas on me most of the time. My routine so far has been to take long walks while listening to music or a writing podcast or take a drive while listening to a Spotify playlist until the ideas begin to shake loose. I start seeing characters and scenes. Then I ask myself what the conflict of the scene is and why. The actual writing takes place late at night during the Witching Hour. I will put on my headphones and pull up a playlist of music that sets the scene and just write.

You’ve described the genre or category you feel most at home in as Afro Nerd. Do you think the traditional publishing industry is open to such literature? Or what has your experience been?

When I wrote my first Afro Nerd book back in 2011, there were not very many books like this in the traditional space. Chris Jackson, who is now the head of One World, has been about the business of putting those kinds of books out into the world, but the industry as a whole has not entirely caught up.

When I wrote my first Afro Nerd book back in 2011, there were not very many books like this in the traditional space. Chris Jackson, who is now the head of One World, has been about the business of putting those kinds of books out into the world, but the industry as a whole has not entirely caught up.

It is my hope that, with the success of people like Donald Glover and Jordan Peele, the publishing industry will invest more heavily in works that are designed for Blerds (Black nerds) and those readers who enjoy speculative works and smart stories written with them in mind. I feel like my novel Daykeeper being selected as the Virginia Indie Project Winner, the National Indie Author of the Year Winner, and the Black Caucus of the American Library Association Best Fiction Ebook Winner is proof that the world might just be ready for this kind of work—and that would be wonderful.

I recall you saying that, until now, you’ve more or less written what you’ve wanted, but perhaps going forward, you’ll write more with the market in mind—e.g., you might write a series, which is the thing to do as a fiction writer these days. Tell me more.

I have written some commercial books in the past, but I’ve also written some books where I knew I was writing for only my literary twin out there somewhere. One of my books, Work-In-Progress, was written using a style of narrative created by the Argentinian writer César Aira, where the book just spins out into nowhere and keeps going. None of the characters have names and the plot is next to nonexistent, yet there is this meta-surreality going on there that I really love. A book like that is not commercial by any means, but it’s fun to write.

While I have swung a little closer back to center, I’m still a bit off to the left. Writing something more commercial, I believe, would help to bring new readers into my writing universe without taking away things that help them to ground themselves.

The series I’m thinking about now would be the ultimate Neo-Soul/Afro Nerd novel, drawing off what I love most about the music, films, and books already in this genre. The ironic thing is that as I begin to think more “market-minded,” I am seeing works out there that, in many ways, resemble some of the offbeat things I’ve been writing. I see my work in the same space as Donald Glover and Jordan Peele, if you were looking at visual media, and Phonte (of The Foreign Exchange and Little Brother), if you were looking at it from the music side. I am envisioning great stories that have a unique African-American male perspective, like the works of Victor LaValle, Kiese Laymon, Mat Johnson, and the artists I mentioned earlier.

As a creative writing professor, what do you most hope your students will learn or take away from a class with you?

As a professor, I just want my students to feel free to write what moves them and to take chances. I also hope that they will discover a family of writers that reinforces their ideas for their art. If they write a good story, but build a better personal library for themselves, I’m pretty happy.

Interested in the Indie Author Project? This year’s contest launched on April 1; submissions will be accepted through May 31. You can find out here if your state sponsors a contest and how to submit. There is no entry fee. Note that it is possible to submit your work to the contest without participating in the larger SELF-e distribution program. Even if you win, you are not obliged to enter into a library distribution agreement through SELF-e. Furthermore, participation in the program is nonexclusive, and winning authors can continue to sell and distribute elsewhere.

May 21, 2019

The Two Basic Rules of Editing (and the Rookie Mistake)

Photo credit: Nic’s events on Visualhunt / CC BY-SA

Today’s guest post is excerpted from How to Work With a Writer by editor Allegra Huston (@allegrahuston).

Many people who find themselves in an editorial role make the same mistake. They think they’re supposed to fix the book. They’ve identified the problems and they expend a lot of mental energy on coming up with solutions. The classic version of this is the film development executive who tells you to put in a car chase (yes, it’s happened to me). The story is sagging, the pace is dragging: you need some excitement! In this case, the car chase solution is like a sugar hit: a rush followed by dissatisfaction. Far better to address the underlying story issues—but it’s hard to do that if a car chase, or some other plastered-on idea, is occupying the center of the discussion.

Landing on a solution and sticking to it distracts both you and the writer from identifying what the problem is. I’ll talk later about what the problem might be. For now, I want to make this important point: once you’ve identified what isn’t working, stop there for now.

Remember: It’s not your job to fix it! Your job is to help the writer fix it.

Big-picture editing is a series of judgment calls. But how should those judgment calls be conveyed to the writer? I have formulated these two rules, which have stood the test of decades of working with writers from the most eminent to the most fledgling:

Rule 1. Praise

Rule 2. Ask questions

Rule 1. Praise

Too often people think being a critic means being critical. That’s only part of it, and not even a necessary part. A good critic assesses what’s strong ahead of what’s weak—because if a work has no strengths, why should anyone care what its faults are? And if, as a reader or editor, you don’t lift up those strengths, what yardstick are you measuring the rest of the writing against? And why should the writer even want to struggle on? I believe that if you can’t say what’s good about a piece of writing, you have no business telling the writer what’s not good about it.

Praise serves different functions:

It sets the tone. A writer is much more willing to entertain your criticisms and ideas if they know that you like their work.

It sets the parameters of what the book can achieve. A pedestrian stylist is never going to write like Jane Austen—but maybe the writer is good at ingenious plotting, like Agatha Christie, or explaining difficult concepts, or mounting a convincing argument, or eliciting sympathetic emotion in the reader. Whatever the writer’s strengths are, they will be stronger in some places than in others. Identify those benchmarks so the writer can set their sights on them.

It sparks ideas. When you tell a writer what you really loved—what surprised you, what moved you, what shocked you, what made you laugh, what made you see something in a new light, a turn of phrase that delighted you, the places where you absolutely couldn’t stop reading—they will often see ways to deepen those responses, or play with them, or find other places in the book that chime with the section you mentioned. The writer will see ways to improve the book that you hadn’t noticed, and that they themselves might not have noticed without your enthusiasm. Which leads to:

It energizes the writer. Now they’re excited! They can see what the book (or script, or story) will look like when they make that change, and they’re longing to get to work on it. When a writer feels that they’re succeeding, they want to add to that success by improving what’s less successful. A writer who feels that they’re failing may be dogged and keep at it, but inspiration is less likely to come, if it comes at all. Often the writer will simply give up.

It gives the writer confidence going forward. The chances are the writer will meet rejection along the way to publication, and beyond. Praise from a reader or editor works as both gasoline and armor.

But what if the work is really awful?

Let’s say you read the first 10 pages as a trial. You can stop there and say, “I didn’t connect with the story, so I guess I wasn’t the right reader for you.”

If you continued beyond the first 10 pages, what’s gone wrong? There must have been something promising, or you wouldn’t have kept reading. Was it the quality of the prose? Was it the premise or the subject matter? A character that drew you in? Praise what you can, but don’t tell the writer the work is terrific if it isn’t. Tell them in broad terms what didn’t work for you, but try not to get pulled into saying critical things you’d prefer not to say. The situation can get uncomfortable fast, so it’s best to stay vague and end the conversation as quickly as possible.

You may feel that the writer is wasting their time, but this isn’t your call to make. They may get better with practice, or they may be gaining benefits from writing that don’t depend on its quality.

Rule 2: Ask questions

This rule covers everything that is not praise—in other words, anything that’s not working for you as a reader. Remember: it’s not your job to fix the book. It’s your job to focus the writer’s attention on problems and spark the writer’s imagination about how to address them.

As an editor, I feel more confident if I don’t expect myself to know the solution to every problem. As a writer, I am far more energized by being asked to think about my work in a new way than by being told what to do.

The purpose of asking questions is not to get answers. Questions give the writer ideas. Prompted by your question, the writer may come up with an alternative plot event or character motivation, a clearer or different chain of argument or narrative, perhaps even an entirely different way of telling the story. Your question may help the writer articulate something that’s obvious to them but that isn’t at all obvious to you.

I don’t mean that you have to laboriously phrase every remark as a question. I mean that you should keep an open mind. If you speak from a position of “I know,” you put yourself in an authoritative, even oppositional, role in relation to the writer. If you speak from a position of “I don’t know,” you ally yourself with the writer, who also doesn’t know. If they knew how to fix what’s wrong, they’d have fixed it already.

Asking good questions is somewhere between a skill and an art. You will certainly get better at it with practice. The best questions come from an imaginative engagement with the story or the subject matter, along with some background knowledge, which will differ according to what kind of writing you’re working on and the intended audience.

If you have a specific solution, remember that it might not be the best one. I usually say something like, “This may not be a good idea, but what if there was a car chase here?” The writer may have already tried that solution and it didn’t work. They may be viscerally opposed to it, perhaps because it’s a cliché. They may love it and be thrilled that you gave it to them. Or—best-case scenario—your idea sparks a better one. And the writer’s imagination is why you’re both here to begin with.

When you talk with a writer, don’t feel that all issues have to be solved by the time you stand up. You are not leaving the writer with a to-do list (at least, not in the early stages of editing). Your goal is to leave them with ideas to try out and explore—and, perhaps, a few things they can easily fix. Don’t be afraid to point out niggly little issues. It feels good to be able to fix a few things quickly.

You may find the writer is touchy and resistant to suggestions. They’re not helping themselves in the long run, but it’s their work and their choice. You can try to crack the writer’s overly vigilant defenses by making them feel safe; praise will be your best tool. But you may have no choice other than to gracefully back away.

You may find the writer is touchy and resistant to suggestions. They’re not helping themselves in the long run, but it’s their work and their choice. You can try to crack the writer’s overly vigilant defenses by making them feel safe; praise will be your best tool. But you may have no choice other than to gracefully back away.

If you enjoyed this piece, be sure to take a look at How to Work With a Writer by Allegra Huston.

May 20, 2019

Choosing a Publicist: Ruling Out and Ruling In

Today’s guest post is by writer Barbara Linn Probst.

Nowadays, many writers elect to hire their own publicists. That’s especially true for those who publish with small, independent, or nontraditional presses, since that may be the only way for them to secure media attention. It’s also true, however, for writers who take the traditional route. Unless you’re a major name, your publisher will have limited time and resources to devote to your book. If you want more exposure, you’ll have to make it happen yourself.

Getting a book on the radar of potential readers is a complex, multi-faceted process. An author can do a lot of the networking herself, but it’s rare for her to have the knowledge, contacts, and clout that a professional can offer—and, without which, the radius of her outreach will remain limited. Thus, a partnership with an experienced publicist can be invaluable.

However, there are a lot of publicists out there. How can you pick the right one?

The author-publicist relationship is a particular, time- and task-specific partnership. While publicists do turn down people who want to work with them, in general the choice is the author’s. It’s a critical decision, intuitive as well as analytic, requiring awareness of oneself along with evaluation of the publicist’s skills and strengths. That is, it’s a look in two directions.

Other essays on this site have described what a good publicist does (and doesn’t) do or given advice on how to prepare for a productive relationship. Posts elsewhere suggest questions to ask a potential publicist—e.g., can you tell me about sample campaigns you’ve overseen, have you ever worked with a book similar to mine, how much do you charge and what is included in the price?

These questions are necessary, but they’re not sufficient. They don’t get at the heart of the matter, which is the fit. Without the fit, the relationship won’t work, regardless of the publicist’s stellar credentials.

As Socrates said: Know thyself. The corollary to that is: Know what you’re looking for. You can’t embark on an intelligent search for a publicist until you’ve examined your own needs, expectations, and transactional style. There are, in fact, two aspects to the search: finding the right expertise, and finding the right relationship. Conflating the two, or focusing only on the first, can lead to an unproductive, unhappy experience. You entrust your book to someone, and then feel let-down when things don’t turn out the way you expected.

The good news is that this kind of disappointment can be avoided by asking the right questions—and then adjusting (right-sizing) if needed—before you hire someone.

Step One: Ruling Out

The first step is to identify publicists who are reputable and affordable. You need to eliminate those you would not want to work with—e.g., people with no references or no experience representing books similar to yours, people who are not transparent about cost or whose fees are beyond your means.

An initial screening should include ethics, competence, and clarity about the nature of the agreement, should you decide to engage the firm. This should be clearly stated on the person’s website or in her written material. What are you paying for: hours, tasks, or results? If you’re buying professional time, the publicist’s proposal should state how many hours are included and/or what the hourly rate is. If you’re buying the accomplishment of certain tasks, regardless of how long they take, those tasks should be listed on the proposal. If you’re buying results—be careful. No publicist can guarantee results. Whether a pitch leads to a placement, or a placement leads to sales, is outside the publicist’s control. There are just too many other factors. All a publicist can guarantee is what she will do, not how the world will respond.

It’s during the ruling-out stage that talking to other authors can be useful. Their experience will help you eliminate any publicist who’s unresponsive, has hidden fees, has misrepresented her experience, or has never represented anyone with a book like yours.

Assuming you’ve covered the questions above, you now have a list of good publicists. The next task is to decide who, among these candidates, is good for you.

In other words, the fit.

Step Two: Ruling In

During the ruling-in stage, when you’re looking for the person who’s right for you, talking to other people may not be helpful. It might be just the opposite, since you’ll always find someone who loved Publicist Mary and someone else who hated her. Too much subjective information, without a way to sort and rank that information, can be confusing rather than useful.

How can you decide, then? People will tell you, “Follow your instinct.” But what is “instinct?” What are the components of the highly personal inner sensitivity that can serve as a guide?

In my experience—as a therapist and teacher, long before I became a novelist—there are three primary areas to consider when seeking the right fit: expectations, temperament, and communication style.

Expectations

From my conversations with authors and publicists, I’ve learned that the biggest source of discord and disappointment is a mismatch in expectations. You need to be clear about what you want, what you can realistically expect to get, and what the publicist can realistically deliver. Mutual understanding is critical; without it, problems are inevitable.

To get to that mutuality, you may need to right-size your expectations, especially if they don’t map well onto the kind of book you’ve written, your author platform, and the amount of time and money you’re willing to invest. The publicist who tells you how much she adores your book or offers a laundry list of promotional activities—with no priorities, options, or ways to tailor efforts to a book like yours—may be inflating your expectations in a way that will backfire later. In contrast, the publicist who delivers a dose of “tough love,” right at the outset, may have your best interest at heart.

It’s important to distinguish between marketing and publicity so you’ll understand what you’re asking for—and what you’ll be getting. People may identify themselves as publicists when, in fact, they’re offering marketing services or just marketing advice. What’s the difference? Other articles have addressed this question. Simply put, marketing refers to the things you pay for, in order to become known (like ad placements), while publicity refers to attention from the media (like interviews and reviews) that you do not pay for. You pay for them indirectly, of course, by paying for the time (that is, the connections and clout) of a professional publicist.

There’s nothing wrong with paying someone to help you with marketing. Just think through your priorities and look for someone who does the kinds of things you want to focus on. After all, there are countless ways to promote a book.

Questions to ask a publicist in order to identify your expectations:

For my particular book, where do you expect to focus your energy? (What works for one book won’t work for all books, authors, or publicists.)

What are you really good at?

Which parts of this process do you enjoy least? (Will you need to find someone else to handle these aspects, are they things you could do yourself, or are you fine with shifting energy elsewhere?)

How will I know if the campaign has been successful?

Temperament

Temperament has to do with the kind of person you are—whether you flare up quickly or have a slow burn, switch gears readily or need time to adapt, have intense feelings or take things in stride. People are different, so it’s natural that they will have different responses to the same situation—or the same publicist.

Think about your previous experiences and relationships. Do you like to plan and know you can rely on that plan, or do you enjoy spontaneity and surprise? Do you gravitate and get along best with people who match your tempo and style, or with people who provide balance?

Think back, too, about other professionals you’ve hired. Do you need to be closely involved, or do you prefer to step back when you know you’re in the hands of someone you trust? Do you need a sense of human connection, or is it enough if the person knows his or her job?

With this self-knowledge, consider the author-publicist relationship and ask yourself: are you looking for a partner (a collaborative relationship) or an expert (someone who will work on your behalf)? Do you need someone who’s passionate about your particular book, or is it enough to know that she’s good at publicizing books, in general? Will you feel disappointed or de-personalized by someone who’s very businesslike?

Questions to ask a publicist in order to identify your temperament:

Will you read my book? What if you don’t like it?

Have you ever signed a client, only to discover that the arrangement isn’t working? How did you deal with it?

What is it about my book that excites or intrigues you? Why would you want me, specifically, for a client?

Can you tell if a client is going to be a good fit or a poor fit for you? If so, how?

Communication style

Do you want to be included in some or most of the decisions, or would you rather receive a report of what’s been done, after it’s been done? Some people want to be closely involved and kept in the loop at all times. They need frequent communication and a chance to voice their views. Other people want to hire someone they trust and then step back; frequent communication feels like a burden.

Each interactional style has its pros and cons. The highly involved client has to be careful not to demand constant reassurance, slip into trying to micromanagement, of details, or tell the professionals how to do their job—after all, that’s what you’re paying them for. On the other hand, the uninvolved client risks feeling disappointed and unhappy, later, when the publicist didn’t read her mind or things didn’t turn out as she’d imagined.

Questions to ask a publicist in order to identify your interactional style:

What kind of reporting or accounting do you send me? How often will I hear from you?

Which tasks might I be able to handle myself? Which would be better for me to handle myself, in order for you to use your (paid) time strategically?

Describe the client from hell.

Tell me about a time when you had a misunderstanding or difficulty with a client. Why do you think it happened, and how did you resolve it?

Parting advice

The twelve bulleted items above are questions that the publicist will be answering. However, your response to her answers can also provide important information. If some of her answers make your heart soar (or sink), that’s information you need to pay attention to. Can you live with what she’s told you? As with all relationships, you can’t embark on a partnership with the hope that the person will be different once you get to know each other.

At the same time, there’s no perfect fit, so you will need to prioritize. Which of the elements above are “must have,” which are “nice to have,” and which are deal-breakers?

This is a crucial decision, so it needs to be approached with care. After all, the purpose of a book is to be read. Your publicist plays a pivotal role in helping to make that happen.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers