Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 95

March 7, 2019

When Words Are What You Love Most of All

Photo credit: pamipipa on Visualhunt.com / CC BY-NC-SA

The writers who visit you in class, when you’re still a student—especially if you’re young and impressionable—these writers stick with you for a lifetime.

I recall vividly a visit from Dana Gioia to my undergrad poetry class, then his reading afterward, and handing him a book to sign. I thought there was no person more intrinsically a writer, so thoroughly in his being and essence someone who loved words. He was nothing less than a prophet.

In her essay for Glimmer Train, Marian Palaia describes Barry Hannah, a writer who made a dramatic impression on her. She writes,

The way I saw it then and still see it today: Barry was blindly in love with everyone and everything, and words are what he loved most of all, and they are what he had with which to express his love. He didn’t hedge his bets, and the sentences he fashioned—those holy, celestial, bonkers sentences—oh my god. As Wells Tower put it after Barry died, “He wouldn’t leave a sentence alone until he’d electrified every word… After Hannah, you couldn’t let yourself write a ‘Then he picked up a coffee cup’ sort of sentence ever again.”

Read more from Palaia: Words, and Barry Hannah, the Guy Who Taught Me to Love Them.

Also in this month’s Glimmer Train bulletin:

We All Do It! Don’t We? by Devin Murphy

The Political Lives of Characters by Siamak Vossoughi

March 6, 2019

When Your Query Reveals a Story-Level Problem

Today’s guest post is by author and editor Susan DeFreitas (@manzanitafire).

As a freelance editor and book coach, I help my clients with all kinds of tough tasks, from untangling plot problems to finding ways to cut 60,000+ words from an already polished manuscript.

But there’s only one job that ever keeps me up at night, and that’s when someone comes to me for help with their query letter and I can tell right away that the problem lies not with their query letter, but with their actual book.

Writing a query letter is hard for almost everyone, so the problem isn’t always obvious from the get go. The author may not have found a way to boil the story down to its essential elements (or may even lack a sense of what those elements are).

The author may have tried to include too much in their query, or not made it clear how the various plot lines connect. They may not have succeeded in communicating the stakes of the novel, or the takeaway—basically, why the story has value, and why a reader might care.

But sometimes a novel cannot be boiled down to a few essential elements because the story itself lacks coherence. Its various story lines cannot be connected in the course of a few clear, punchy sentences because those story lines themselves aren’t clearly connected by cause and effect. The stakes of the novel can’t be stated in a way that’s compelling because the stakes of the story simply aren’t high enough; there is no emotional takeaway because the novel lacks an effective character arc.

Yes, boiling down an 80,000-word novel to just a couple paragraphs is a brutal business, but it also tends to reveal the overall shape of a novel, just the way a map reveals the overall shape of a country, in a way that simply can’t be intuited while making your way across the landscape it describes.

And what I’ve noted here are just a few of the ways that structural or thematic issues can reveal themselves at the very last stage of the writing process—the point where you’re ready to pitch—making it virtually impossible to write a query letter that will sell.

A novel that can’t meet the standards for a query letter generally will not meet the standards of the marketplace for fiction. Agents and editors know this; that’s why they require pitches that adhere to this form. (Editors who specialize in memoir will tell you the same thing.)

And part of why this sort of scenario gives me nightmares is that the author who comes to me for help at this stage is generally no slouch. They’ve studied creative writing, taken classes, attended conferences, seminars, etc.—oftentimes they’ve even hired an editor to help them perfect the language.

How can I explain that despite all the time and effort—and often, money—they’ve invested in this book, it’s unlikely anyone will publish it? This is not the stage at which anyone wants to go back to the drawing board.

As far as I can tell, people wind up in this position for three reasons:

1. The line editing happened before developmental editing.

Having your novel line edited before you receive developmental feedback on the story as a whole is like rearranging furniture in a room that might need to have a wall knocked out.

You might get lucky and wind up with a floor plan that works on your very first attempt at building a house, but chances are, you won’t. And while it’s fine to discover your story by writing it (hello, pantsers!), you owe it to yourself to bring in a seasoned architect or two to at least take a look at the place before you start unpacking Grandma’s china.

2. They believe they can write a publishable novel intuitively.

This is not to say that some writers don’t possess this ability—especially if they’re writing in a genre with a pretty set pattern, like the cozy mystery, and they’ve read a ton of books in this genre.

It’s only to say that such people tend to be outliers, especially when they’re first starting out. Flannery O’Conner once said, “Everybody knows what a story is until they sit down to write one.” In my experience—as both an author and an editor—truer words were never spoken.

3. They’ve studied story structure, but they haven’t figured out how to apply it to their own book.

This isn’t surprising, since many creative writing teachers (and authors of books on craft) essentially teach their own idiosyncratic process. Which is great if your work and process aligns with theirs—but if it doesn’t, you’ll excitedly scribble away notes and insights that feel like revelations at the time, but later, when you go back to try to apply them to your novel, you’ll struggle to see how they apply (or how they might help you solve the issues you’ve already identified).

The novel is novel, in that it’s endlessly open to reinvention; in my experience, it’s only the truly foundational principles that apply to nearly any type of long-form fiction. The kind of person who generally has insight into the most broadly applicable principles—and the role they play in producing publishable fiction—is a freelance developmental editor.

And personally, I’d rather be the bearer of good news than bad. Which is why I’d so much rather work with first-time authors early in the development of their novels than at the end, when they’re asking me to help them accomplish something that simply isn’t possible.

Note from Jane: Starting March 26, Susan is offering a new online class through LitReactor called Nail Your Novel. She’s spent nearly a year developing this class, which reflects—in the simplest possible, most actionable terms—what she’s learned over the past ten years as a freelance editor and book coach.

Note from Jane: Starting March 26, Susan is offering a new online class through LitReactor called Nail Your Novel. She’s spent nearly a year developing this class, which reflects—in the simplest possible, most actionable terms—what she’s learned over the past ten years as a freelance editor and book coach.

This class will help you get a handle on what it really takes to meet the standards of the marketplace for fiction, and how to make it happen—not in the abstract, not in someone else’s book, but in your own. Which, in the end, is going to make your book a whole lot easier to pitch.

March 5, 2019

On March 8: Join Me for The Magical Marketing Trifecta

Sorry, the online session is sold out! There is still room for in-person attendees.

When writers ask me about “must haves” for marketing or overall career development, I always hesitate to list requirements. Every writer is different; every career is different. However, I do think you can gain better momentum and traction if you’re willing to build a foundation with these three integrated components:

Author website: your 24/7 business card to the world and official hub

A presence at one social media network: where you are regularly visible to all in the community

Your email newsletter: your most valuable outreach to those who are interested in your work

This Friday evening, I’m teaching an online class, The Magical Marketing Trifecta: all about your website, social, and email outreach. It’s super affordable—just $15 to register. If you can’t attend live, you’ll get the recording.

While the class is hosted by Creative Nonfiction, it’s suitable for writers of all genres and backgrounds.

If you happen to be in Pittsburgh, you can join me in-person for the class! It will be longer than the online broadcast and include discussion and critique. Learn more about the in-person class.

March 4, 2019

A Primer on Estate Planning as a Writer

Photo credit: Ken_Mayer on Visual Hunt / CC BY

Today’s guest post is an excerpt adapted from The Law (in Plain English) for Writers by Leonard D. DuBoff and Sarah J. Tugman. It is run with permission from Allworth Press.

Awareness of estate planning issues can be especially important to writers because of the unique nature of property rights in written works. Proper planning ensures that the ownership of a writer’s works after his or her death will end up in safe and knowledgeable hands.

In addition to giving the writer significant posthumous control over his or her works, an estate plan can greatly reduce the overall amount of estate tax paid at death. Because valuations of written works for estate tax purposes are not precise, estate taxes may turn out to be significantly higher than might have been anticipated. Thus, it is very important for writers to reduce their taxable estate as much as possible.

An estate plan may be either will-based or trust-based. Each type has advantages, but both are legitimate forms of estate planning. Estate laws and probate procedures vary throughout the United States, and a plan that works well for one person in one state may be inappropriate in other situations. Proper estate planning requires a knowledgeable lawyer and sometimes the assistance of other professionals, such as life insurance agents, accountants, and bank trust officers.

The Will

A will is a unique document in two respects. First, if properly drafted, it is ambulatory, meaning it can accommodate change, such as applying to property acquired after the will is made. Second, it is revocable, meaning it can be changed or canceled before death.

When carefully prepared, wills not only address how the assets of the estate will be distributed, but also foster better management of the assets. Those persons responsible for administering the estate of a decedent are known as executors in some states and personal representatives in others. It may be a good idea for writers to appoint joint executors so that one has publishing or writing experience and the other has financial expertise. In this way, the financial decisions can have the benefit of at least two perspectives. If joint executors are used, it will be necessary to make some provision in the will for resolving any deadlock between the two. A lawyer’s help will be necessary to set forth all of these important considerations in legally enforceable, unambiguous terms.

It is essential to avoid careless language that might be subject to attack by survivors unhappy with the will’s provisions. A lawyer’s help is also crucial to avoid making bequests that are not legally enforceable because they are contrary to public policy.

Trusts

A common way to transfer property outside the will is to place the property in a trust that is created prior to death. A trust is simply a legal arrangement by which one person holds certain property for the benefit of another. The person holding the property is the trustee; those who benefit are the beneficiaries.

To create a valid trust, the writer must identify the trust property, make a declaration of intent to create the trust, transfer property to the trust (this is often a step that is missed and can create a multitude of problems), and name identifiable beneficiaries. Failure to name a trustee will not defeat the trust, since if no trustee is named, a court will appoint one. (The writer may name himself or herself as trustee.)

Trusts can be created by will, in which case they are termed testamentary trusts, but these trust properties will be probated along with the rest of the will. To avoid probate, the writer must create a valid inter vivos or living trust.

Advantages of Using a Trust

The use of trusts to prepare a trust-based plan will, in certain situations, have significant advantages over a traditional will-based plan. For example, the careful drafting of trusts can allow the writer’s estate to avoid probate, which in some states is a lengthy and expensive process. Similarly, the execution of an estate through a trust-based plan can ensure a level of privacy not possible in probate court. Although these kinds of provisions provide some control over the estate, writers are cautioned that trusts cannot adequately substitute for a will if used haphazardly. Professional assistance is strongly recommended.

Life Insurance Trusts

Life insurance trusts can also be used for paying estate taxes. The proceeds of a life insurance trust will not be taxed if the life insurance trust is irrevocable and the trustee is someone other than the estate executor. Even when the trust is irrevocable and the trustee is a third party, the proceeds are taxed to the extent they are used to pay taxes to benefit the estate. The advantage to this arrangement, then, is not so much tax avoidance as guaranteed liquidity. This advantage is especially important for writers and other creative people, since otherwise survivors can be forced to sell remaining works for much less than their real value in order to pay estate taxes.

Life insurance trusts can also be used for paying estate taxes. The proceeds of a life insurance trust will not be taxed if the life insurance trust is irrevocable and the trustee is someone other than the estate executor. Even when the trust is irrevocable and the trustee is a third party, the proceeds are taxed to the extent they are used to pay taxes to benefit the estate. The advantage to this arrangement, then, is not so much tax avoidance as guaranteed liquidity. This advantage is especially important for writers and other creative people, since otherwise survivors can be forced to sell remaining works for much less than their real value in order to pay estate taxes.

For an in-depth guide to legal issues for the writer, check out The Law (in Plain English) for Writers by Leonard D. Duboff and Sarah J. Tugman.

February 25, 2019

3 Types of Contracts Every Writer Should Understand

Today’s guest post is an excerpt adapted from The Law (in Plain English) for Publishers by Leonard D. Duboff and Amanda Bryan. It is run with permission from Allworth Press.

Many aspects of publishing—including arrangements with authors, agents, illustrators, freelancers, employees, printers, binders, and distributors—involve contracts. The terms of a contract vary depending on the situation, but in every case, the nature of legally binding agreements is the same. Here are three common forms of contract.

Implied Contracts

Contracts that are not explicitly stated in words may be implied by conduct. For example, suppose that a writer submits a manuscript to a publisher, which publishes the manuscript but does not compensate the writer. Even though they did not sign a contract, there is an implied contract between them. The terms of that contract depend upon the relationship between the writer and the publisher.

If the facts indicate that the writer submitted the manuscript with no expectation of payment, then none would be due. On the other hand, if the writer has historically submitted manuscripts to this publisher and received payment from the publisher for publishing them, it is likely that the writer expected to receive compensation and that a promise by the publisher to pay would be implied. The implied terms of the contract would be legally enforceable. But absent a clear written agreement, the parties could be faced with lengthy and expensive litigation to determine the amount due and other issues.

Oral Contracts

An oral contract is one in which the parties have verbally agreed to something but have not recorded the agreement in writing. Most oral contracts are valid and enforceable, although some kinds of agreements are legally required to be in writing to be enforceable. As a practical matter, oral contracts are often difficult to prove in court, since the main evidence is usually the conflicting testimony of the parties. It has been said that oral contracts are not worth the paper they are written on. While not technically correct, this adage does reflect the harsh reality that many worthy claims cannot successfully be enforced because oral agreements lack the strength of written ones.

Written Contracts

Written agreements should adequately describe the obligations of the parties and the consideration involved. Custom dictates that written contracts be signed and dated by the parties.

Under the Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act (ESIGN) and various state laws, transactions executed electronically, such as by email, cannot be invalidated solely because an electronic signature or electronic record was used in their formation. An electronic signature is any identifying mark, such as the sender’s name at the end of an email or email address in the header. Some kinds of documents, such as wills, are typically covered by these laws, as are most publishing agreements.

Some types of agreements are legally required to be in written form. The Statute of Frauds, a law adopted to inhibit fraud and perjury, provides that any contract that cannot be fully performed within one year must be in writing in order to be legally binding. This rule has been narrowly construed to mean that if a contract can conceivably be performed within one year of its making, it need not be in writing.

Assume that a writer has agreed to submit two manuscripts to a publisher—one within eighteen months after the contract is signed and the second within eighteen to twenty-four months thereafter and no earlier. In this situation, the terms of the agreement make it impossible for the writer to complete performance within one year. If, however, the writer agrees to submit both manuscripts within twenty-four months, it is possible that the writer could submit both manuscripts in the first year and the requirements of the Statute of Frauds would be satisfied.

The fact that the writer might not actually complete performance within one year is immaterial. So long as complete performance within one year is possible, the agreement need not be made in writing. The Statute of Frauds applies to other kinds of contracts as well, but these rarely involve writing activities.

For a contract to be enforceable, the parties must be capable of understanding their contractual obligations. Minors are deemed by law to have diminished capacity to contract. A person is legally a minor until the age of majority. This age varies from state to state but is either eighteen or twenty-one years of age in most states.

Persons who have the capacity to enter into contracts and who sign written agreements are generally bound to the terms of those agreements, irrespective of whether they read or understood the agreement before signing. The law imposes the burden on the parties to read proposed agreements and understand the terms prior to signing them. The fact that an  agreement was lengthy, obtusely drafted, or complicated will seldom justify rescission, except when the terms are unconscionable or against public policy.

agreement was lengthy, obtusely drafted, or complicated will seldom justify rescission, except when the terms are unconscionable or against public policy.

For an in-depth guide to legal issues from a publisher’s perspective (especially helpful for prolific indie authors and small presses), check out The Law (in Plain English) for Publishers by Leonard D. Duboff and Amanda Bryan.

February 12, 2019

Understanding Audiobook Production: An Interview with Rich Miller

Today’s guest post is by author Kristen Tsetsi, who is a regular contributor to this site through the 5 On series.

Like many indie authors grateful for new outlets for their work, I was drawn last year to the world of audiobook production. This was thanks in large part to the recommendation of author friend Ian Thomas Healy, who’d had a positive experience adapting his work for audio. His personal history with it, combined with the rise in audiobook popularity, led me to follow Healy’s example and create an audiobook at ACX, Amazon’s audiobook production platform.

When I entered into that first relationship with an audiobook narrator/producer, I knew absolutely nothing about how an audiobook was made (beyond the obvious “skilled voice actor records a reading of a book”). This meant I also had no idea how much there was to know. My “extensive” research involved learning the difference between the PFH (per finished hour) and RS (royalty share) payment systems offered on ACX and browsing voice samples in ACX’s pool of available narrators.

What I learned as part of the production process was that the more an author knows going in, the less potential there is for strain in the author/producer relationship. As uninformed as I may have been, and as lucky as I was to find a narrator who was easy and fun to work with, one element impossible to be blind to was the explosive potential of this recipe: writer/artist protective of original work and its intent + narrator/artist protective of professional ability to deliver a valid interpretation of the original work.

And that doesn’t even graze the issue of fair payment. What I didn’t learn until recently was that the $100-$200/PFH I had seen offered by many narrators at ACX and therefore thought was reasonable compensation is, according to seasoned professionals who frequently discuss pay issues in a Facebook group for audiobook narrators, woefully inadequate. Had I done more research in my earlier audiobook days, I’d have learned that other production companies, such as ListenUp Audiobooks, charge $450 per finished hour. This in turn would have helped me not balk at the $250/PFH minimum requested by many ACX producers in the Facebook group. (The group’s regular users often direct new narrators to audiobook narrator Julia Sage’s website, which hosts a helpful cost calculator as well as a comprehensive explanation of the differences between Per Finished Hour, Royalty Share, and Hybrid agreements. Highly recommended for authors considering adaptation.)

Pay issues can be resolved fairly easily, but artistic conflicts can be trickier. How much input should an author have when it comes to the narrator’s interpretation? When is feedback helpful, and when is it frustrating?

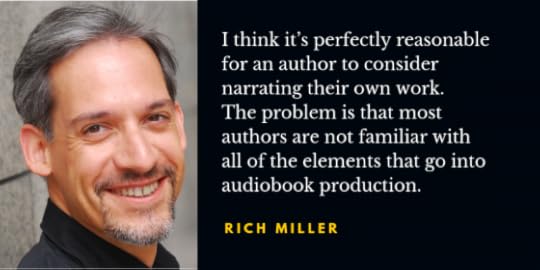

For answers to these and other questions, I reached out to someone who’s not only experienced in the field of audiobook production, but who has also interviewed countless other narrators, and a few authors, about their own experiences with audiobook production: Rich Miller (@RichMillerVO), stage and screen actor, audiobook narrator, and creator and host of The Audiobook Speakeasy podcast.

Rich has been a storyteller since he was a kid. When he was around 10, he started reading to his family after dinner (his favorites were The Lemonade Trick and The Big Joke Game, by Scott Corbett). As an adult, Rich started acting in musicals and plays, and from there went into theatrical sound design and voiceover work. For the past five years, Rich as been focusing on telling stories through audiobooks. When he’s not in the recording booth, he’s dodging Tucson drivers on his bicycle or creating a new cocktail.

KRISTEN TSETSI: What awkward moment or mistake, whether mechanical or self-inflicted or in an exchange with an author, did you experience as an audiobook narrator that you don’t believe you’ll ever forget?

RICH MILLER: I think the worst mistake I’ve made is agreeing to narrate a book that was primarily made up of text that was handwritten by dozens of people, often poorly photocopied. It was grueling work, more stopping-and-starting than any other book I’ve narrated. It reinforced something that I knew was true, but that’s easy to forget or minimize when you’re working as an entrepreneur: it’s okay to turn down work when there’s a good reason to do so.

You’re both a stage-and-screen actor and a book narrator. Does narrating take a special skill, or could most actors also be audiobook narrators?

I’d actually answer “yes” to both questions.

Stage actors who cross over into film learn that the mediums are very different, so they learn how to use the skills they already have in a different way. So it is with audiobooks: having a background in any form of acting gives you a leg up, you just have to adapt the tools you already have for use in a different medium.

When going from stage to audiobooks, an actor needs to learn how to be “small”: you have to be able to portray the same level of intensity as you might do on stage moving around expressively and shouting, but without moving your mouth away from the mic too much and without actually shouting. This is similar to going from stage to film, with the added constraint of knowing that you can’t rely on facial expressions to convey anything to your audience: they may help you deliver lines believably, but alone they don’t add to the listener’s experience.

With fiction, there’s usually also the need for the ability to portray a character who is not the same gender as the narrator without taking the listener out of the story. There are a few narrators who can do this so well that it’s easy to believe that the audiobook is actually a full-cast production, but most listeners are fine as long as the characters are clearly differentiated without the narrator resorting to methods that make it obvious they’re faking something (e.g., a male narrator using a falsetto for all female characters). Subtlety is generally a good thing.

What made you decide to dedicate a podcast to audiobook narration?

I’d been narrating for a couple of years, and in that time I’d been listening to more and more podcasts about a variety of topics. I thought, “There’s got to be some podcasts out there about audiobooks,” so I searched and found some.

The problem was that most of the ones I found catered to listeners, and while occasional comments about why the narration in a particular audiobook did or didn’t work were interesting, I found myself wanting more content that would be helpful to narrators: input from coaches, engineers, casting directors at publishing companies, etc.

I met Scott Brick at the Audiobook Publishers Association Conference in 2017 and mentioned my idea to him, and he was kind enough to share some ideas with me based on the many interviews he’d participated in. During that same conference, I enjoyed sharing a few drinks with many friends in the industry, and since I’d become somewhat of an amateur mixologist over the past few years, framing the podcast as a friendly chat about audiobooks over drinks seemed like a natural fit. Thus, the Audiobook Speakeasy was born.

Your first episode, an interview with Sean Allen Pratt, includes a discussion about the three questions to ask yourself before agreeing to a contract: is the pay satisfactory, what will it do for your career, and will you have fun? How do you know whether you’ll have fun? That is, how much of the book do you typically read before deciding whether it will be fun, and what else helps you decide?

I think Sean’s advice is great. After doing this for awhile, I have found that I don’t actually think of those questions one at a time anymore, but each one of them absolutely plays a part in my overall decision-making process. In terms of fun, I feel like I usually get a good sense of the tone of a book within a few pages. If that tone doesn’t excite me in any way, I’m definitely focusing more on the other aspects — pay and career — when deciding whether to pursue a project.

In episode 17 of the Audiobook Speakeasy, Audiobookworm creator Jess Herring says in a conversation about sound quality of audiobook recordings, “Some authors want to record their own books.” In response, you almost inaudibly murmur in the negative. She goes on, “…which is a bold choice…”

Though it could easily be argued that you and Herring are right to warn authors not to read their own material unless they have an acting background (whether stage or straight voice), it could also be argued that there is legitimate concern on the author’s part that the narrator won’t correctly deliver a certain line of dialogue or the personality of a character. All writing is of course open to personal interpretation, but a silent reading allows for any number of interpretations; a voice reading, on the other hand, determines a single interpretation for all listeners.

What would you say about this to an author considering audiobook production for the first time and uncertain about whether to hire a narrator?

I think it’s perfectly reasonable for an author to consider narrating their own work. The problem is that most authors are not familiar with all of the elements that go into audiobook production.

In addition to the performance aspect, there’s understanding how to properly set up and treat a recording space; mic choice; mic technique; and recording software proficiency, to name a few.

There are certainly ways to deal with a lack of knowledge in those areas, such as hiring a director and an engineer and booking time in a professional studio, but many authors are not thinking along those lines, they’re thinking about self-producing. So whenever I hear that an author wants to narrate their own work, I try to caution them about everything they need to know before going that route.

I think that it’s also perfectly reasonable for an author, especially one who has never had an audiobook produced before, to have concerns about how a narrator is going to interpret their text. But a well-selected audition piece and open communication with the selected narrator should allay any fears. It’s also important to remember that while an author knows the characters that they created, it’s possible to get too close to one’s own work: a character that is portrayed differently than how you hear them in your head may resonate more with the audience.

And there, I think, is where the author/producer relationship has potential to get delicate. Actor and audiobook narrator Barbara Rosenblat says in episode 28 of your podcast, of her first time narrating an audiobook, “I thought, ‘That was the most incredible piece of work I’ve ever done. I mean, the control of being able to create all your own characters in this setting.’ And I thought, ‘Oh my god, this is brilliant!’”

An author might be of the mind that s/he is the creator of the characters and may be uncomfortable with someone else re-creating them, or re-envisioning them. Actors are used to taking direction when performing on stage or set, but novels don’t have directors—only their authors. Is feedback/guidance from authors received as it might be from a play or film director? That is, do you welcome their input or their suggestions about delivery, or are they generally not trusted because they’re writers and not actors (or not otherwise involved in the acting world)? Is there a commonly understood “just right” amount of input?

Unfortunately, there is no “just right” amount of input. I know narrators who are very explicit with rights holders when starting on a project, and go so far as to send a detailed description of how they’re going to work, including a statement about the fact that they will accept no creative or directorial change requests once the first fifteen minutes have been approved. In a recent podcast episode, I had a chat with an author/narrator pair who knew each other prior to audiobook production, and it was clear that the author gave a great deal of direction during the process. So it really depends on the people involved.

I think the important point is that the author is not the director: either the book is being recorded in a studio with a director and an engineer and a narrator, as often happens at the major publishing houses, or the book is being recorded by a single person who is self-directing (with an occasional outlier, e.g., an engineer is hired but no director), but in neither case is the author the director. That doesn’t mean that an author’s input can never be considered; it simply means that how much input will be welcome should be determined by the parties involved before embarking on the journey.

What list of helpful notes should any author provide after finding a narrator/producer but before the recording begins?

I think the most important things that should be communicated are whatever the author is most concerned about. This will vary from author to author, but generally speaking I think characterizations are most important: his words are bold, but are they coming from a place of power or insecurity? Her words are whiny, but is she simply spoiled or is she being manipulative? A lot of times, the answers to questions like that are fairly clear from the text; sometimes they’re not.

Pronunciations are also important: it’s up to the narrator to pronounce actual names (e.g., names of places that exist) correctly; but if your novel has fictional place names where the pronunciation can’t be researched, if you care about how it’s pronounced, make it clear.

If every author would provide this type of information up front, I think 90% of the conflicts that arise during self-directed audiobook production would disappear.

What kind of author is a horror to work with, and what kind of author is a joy to work with?

I think the most difficult interactions are with authors who want to micro-manage a project: requesting a pause be lengthened by a half-second, giving a line-reading on a character’s line of dialogue (or 100 lines of dialogue!), etc.

Again, most of those things can be avoided with a well-selected audition piece, good feedback on the audition and/or an initial submission (e.g., the first fifteen minutes through ACX), and a list of concerns before production begins.

The authors that I love working with are the ones who understand the creative and interpretive nature of the work, and can share a thought like, “That’s not at all how I heard that in my head, but that’s fine, what you did works great!”

There’s a recurring conversation on an audiobook producers’ Facebook page that centers on producer pay. Last year, when I was looking for a producer for my first audiobook, I would often see “Available for royalty share (no money paid up front, and author and producer split profits 50/50) or $100-$200 PFH (per finished hour).”

But what’s being said in the Facebook group is that no producer should accept less than $250 PFH (nor should they enter into a royalty share with any author who isn’t a sure-thing big seller) unless there’s a hybrid royalty share + PFH agreement.

This is a multiple-part question:

What is the minimum an author should expect to pay for a narrator/producer, and why?

When will an author know the producer is clearly overcharging?

What is expected of an author who does manage to secure a royalty share agreement with a producer, and what is expected of the producer?

When would you say to an author, “You’re not a likely candidate for a royalty share agreement”?

Recurring conversation is right! Hardly a day goes by when I don’t see a new conversation about rates, either because of an initial question or as a tangent to some other topic.

It’s a bit of a dicey subject, because colluding with others to set a minimum rate would be price-fixing, which is illegal. So I want to make it clear that I am not trying to organize any sort of movement, or get any group of people to agree to a rate structure. But I can explain why the $250PFH number comes up so often.

Many of us look to SAG-AFTRA, the union that covers this type of work, as a good guide when deciding on a rate to charge. The union has negotiated minimum rates for audiobook narration with all of the major publishing companies; these vary from company to company, but I believe they range from somewhere around $175PFH to somewhere just north of $250PFH.

This rate is for narration only; post-production is not included. When a narrator produces an audiobook on their own, post-production IS included, and most editors charge between $60PFH and $100PFH. So the argument is that, in order to net a rate that would fall within union guidelines for reasonable pay for this type of work, a rate of $250PFH is the lowest a narrator should charge for full production.

One thing that’s important for authors to understand is the amount of time and/or money that goes into audiobook production. It’s easy for someone unfamiliar with the process to think, “Why should I pay someone more than $100 an hour to talk into a microphone?” But if someone is handling all aspects of the production, they will likely be putting in 4 to 6 hours of work for every finished hour of audio (probably more if they’re new to the work), bringing the rate down to just north of minimum wage. And if they’re outsourcing post-production (always a better choice), they’ll be cutting the time probably in half, but they’ll also be cutting the revenue: if they’re paying an editor $75PFH and then taking 2 hours to narrate every finished hour of audio for the remaining $25PFH, they’re once again down to somewhere around minimum wage. For work that requires the skill set and equipment that professional audiobook narration requires, this is unreasonable.

I think the only reason that an author should think that a producer is overcharging is if they paid a reasonable rate for professional audiobook production and the finished product didn’t sound like a professionally produced audiobook. But that’s always going to be at least somewhat subjective, so I think it’s impossible to come up with some sort of “test” that will give a definitive answer in every situation.

When doing a royalty share through ACX, the ACX contract that is generated is fairly explicit in many areas of responsibility. In my mind it boils down to: the author should provide the manuscript, give me any feedback on the audition that will help with the rest of the book, provide any information on characters, pronunciations, etc., that are important to them, and give me detailed feedback on the first fifteen minute submission. In return, I’ll provide them with a professionally-produced audiobook. As long as we both make a good faith effort to work with each other, we should be fine. I don’t really see the responsibilities any differently than for a PFH project (other than the responsibility of the author to pay me!).

When considering a royalty share project, I look at content, Amazon reviews (both the number of reviews in relation to how long the book has been out, and how the reviews look in terms of overall rating and whether anything negative is mentioned over and over), and social media presence of the author.

If I’m still not sure, I’ll ask for sales figures if the book has been out for more than a few weeks. I don’t do many royalty share projects these days, because the number that I think will earn out over time is very small.

What is the biggest challenge to you personally as an audiobook narrator?

My biggest challenge is borborygmi. Colloquially known as “tummy rumbles.” Gut noises are totally normal, but my gut makes a lot of noise. No, really, a LOT of noise. Frequently. Eating makes it noisy. Not eating makes it noisy. Drinking water makes it noisy. On the surface, it sounds sort of funny; but when you’re sitting in a small room with a very sensitive microphone, it can be incredibly frustrating to have blocked out a few hours to record, only to have an hour or two stolen by your own body. I’ve learned to be very flexible with my time, but it’s still a challenge.

In terms of performance, I think my biggest challenge has been “warmth”: making nonfiction more of a conversation than a lecture, and third-person fiction narration more engaging. Fortunately, with great coaches like Sean Allen Pratt and Carol Monda, I feel like I’ve come a long way on that front.

Thank you, Rich.

February 11, 2019

The Myth of Plan First and Write Later

Photo credit: Sebastian Niedlich (Grabthar) on Visualhunt.com / CC BY-NC-SA

Today’s guest post is by writer and creative writing tutor Louise Tondeur (@louisetondeur), author of The Small Steps Guides.

I hadn’t heard of plotting versus pantsing when I wrote my first two novels—and I didn’t know much about planning at all.

For those who haven’t heard of plotting versus pantsing, it refers to one group of writers who prefer to plan first then write, as opposed to a second group who prefer to write by the seat of their pants. (As a Brit, I had to learn that this meant trousers and not knickers.) The polite term—and my preferred one—for pantsing is intuitive writing. Intuitive writers, according to the common story, simply write, however the mood takes them, and plan later on.

Plotting versus pantsing is one popular version of the plan first/write later myth. This myth basically would have you believe that generating ideas, planning, writing, redrafting, submitting and publishing happen sequentially, in that order, in a linear fashion.

The myth also has its mirror image, the idea that there are some writers out there (for some reason I’m picturing them with flowing scarves) who simply cannot plan first and must write a draft then turn it into a novel. To me, this mirror image (although it’s the opposite) is simply part of the same story.

How did the myth of plan first/write later arise?

I don’t know for sure, but after twenty-five years of teaching (and therefore sometimes having to read dodgy writing advice) I have a feeling that the idea that you have to plan first/write later (or that you simply can’t) came about because of these four things:

The idea that, to be truly creative, you must be an intuitive writer, who writes with their soul, who doesn’t need to plan first.

The idea that a creative person is synonymous with a messy person. Therefore, so the story goes, a truly creative person couldn’t possibly plan first—they wouldn’t be able to find their plan under all those piles of creative outpourings for a start.

The opposite idea: that an efficient, productive person is someone who plans, with business-like rigor, but that their business-like efficiency prohibits them from being “truly creative.”

Bestselling writers, for whom the planning process was probably pretty hazy by the time they did the interview, claiming either to “plan first” or “simply write.”

I seem to remember that Jeffrey Archer was one of those hailed as a planner. Back in the day, I gasped at the idea of doing nothing but planning for three months and nothing but writing for six months—it seemed like such an unreachable goal.

Why the plan first/write later myth (or its mirror image) is damaging

Any time I’m presented with an either/or, one thing versus another, I get suspicious. That’s because there it’s almost always an oversimplification, or there’s more context than the either/or choice suggests. There’s a game gets played on kids’ TV over here where they interview a pop star by asking them to choose between either/ors. Cat or dog. Pizza or salad. Tea or coffee. Which begs the question: why on earth can’t I like cats and dogs, pizza and salad, tea and coffee? Or feel indifferent about all of them? What if I run a pet-friendly café?

Of course, if you have successfully used a linear method of plan, write, publish, or indeed, write, reshape, publish, then I raise my glass to you. I’m not telling you to stop! However, the myth can be damaging to people who are starting out because:

An inflexible, fixed plan feels restrictive, and in some cases can lead to “fear of the blank page” so bad that you don’t write a thing.

It leads people to (mistakenly) think that they plan once, then get on with it.

It could mean that intuitive writers (those who like a bit of meandering and pondering) never get going with their story and lack narrative drive.

Here’s what to consider instead

Plan all the time. Plan at scene level, too. Use any planning tool you like – but do not do it once. You don’t plan, then forget about the plan. Redo your plan at least once a month. Tweak your plan weekly.

Consider using scene cards (write the scenes from your novel on separate index cards). This is because it makes your plan portable, and you can see all of it if you lay it out on a table or stick it up on the wall.

Write intuitively all the way through the process. Write to your plan, but in addition have writing sessions where you go out and observe the world and freewrite about it. Observing the world like this will add depth to your characters and the locations in your stories.

Just as you do not have to choose between cats and dogs or tea and coffee, you don’t have to choose between planning and “simply writing.” Do both, at different times, all the way through the novel writing process.

February 5, 2019

How to Grow an Email Newsletter Starting from Zero

Today’s guest post is by Christina McDonald (@Christinamac79), author of The Night Olivia Fell.

An email list is your secret weapon for selling books—it is a direct connection to your reader. But when I got my first book deal, I had no audience, no author Facebook page, and no email list. I knew I needed to build awareness to give my book the best chance to succeed. Here is my step-by-step guide to how I built my email list to 6,000 subscribers in one year.

1. Draft a plan

The first thing I did when I got my book deal was sit down and come up with a plan to build an email list. Coming from a digital copywriting background, I knew that social media sites like Facebook and Twitter were good for brand building, but not for getting people to buy. Buying happens through an email list. I also knew I would need to provide people with a benefit to get them to sign up. Here’s what I decided to provide:

Quarterly newsletters

Interviews with authors

Free book giveaways

2. Get the tools you need

Once you have a plan to grow your email list, you’ll need to get the tools to implement it. The tools are:

An email marketing tool. I use Mailchimp because it’s cheap and easy. Mailchimp is where I collect the names and emails of people I communicate with. It allows me to send emails to everybody on my list at one time.

Website. I use WordPress, which offers free accounts at WordPress.com.

A Facebook author page. This is different from a personal page. The main reason to have this is to run ads, but it also helps you build your audience and connect with readers.

Prizes and books to give away. I decided to give away free books signed by the author as a way of encouraging people to sign up for my email list. If you can’t get an author to give you a signed copy, you can still buy a copy and give it away.

3. Set up the giveaway page

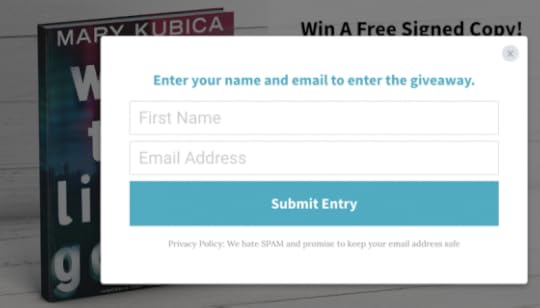

This should be a very simple page with one goal—to get people to sign up for the newsletter. The design should include a headline with the main benefit, some additional text explaining how the giveaway works, and a way for them to enter. Try to get an image of the book cover if possible.

4. Create an email capture form

Create a form using your email marketing tool (such as Mailchimp) to capture names and email addresses and add them to your email database. I make clear on this giveaway page that subscribers are signing up for my book club to enter to win the book. The Enter To Win button takes the reader to a form asking them to enter their name and email address. (See note on GDPR at the end of this article.)

Here’s a great article on how to create an email capture form using Mailchimp; it includes information on GDPR as well.

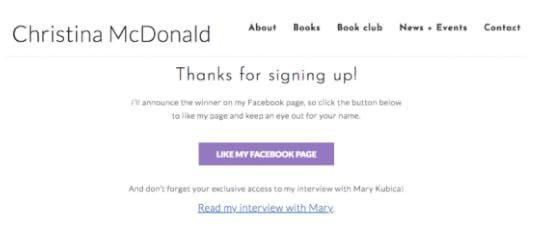

5. Create a thank-you page

Once someone submits their information, you can choose where to direct them. Rather than a generic thank you page, I take users to a page that encourages readers to like my Facebook page, as this is where I announce the winner. Because I announce winners on my Facebook page, I get a number of email list subscribers also following me here. At this point I also give them access to my interview with the author of the book as free, extra content.

Here’s what my thank you page looks like:

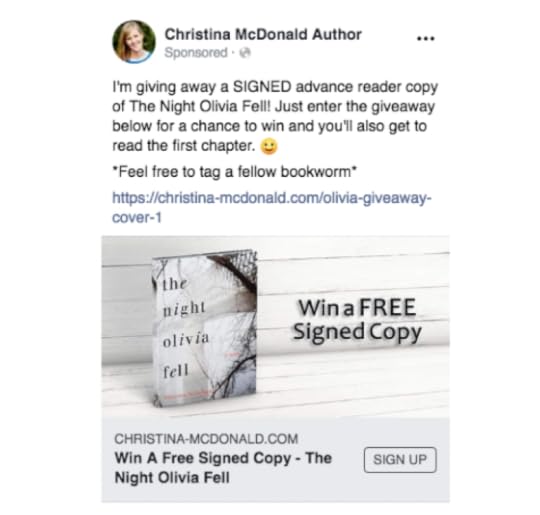

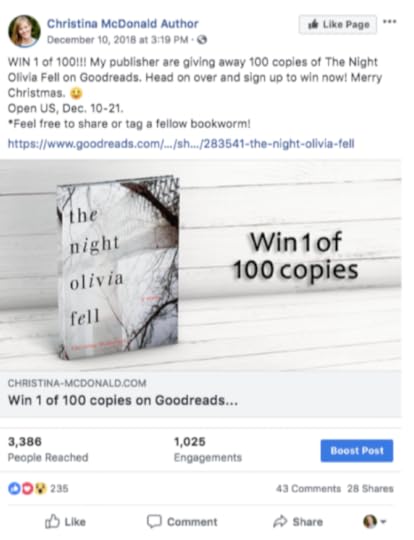

6. Get signups through Facebook advertising

I used Facebook advertising to drive people to my giveaway landing page. There’s a lot of depth and complexity to Facebook advertising, but an easy way to start is to just boost your posts. Even if you have zero followers, you can target others with a Facebook account based on their interests. For example, you can target fans of similar authors in your genre.

Create your post. To start, create a post on your Facebook author page announcing you’re giving away a free signed book. Include the link to your giveaway signup page where readers can enter their name and email. Once the giveaway is finished, you’ll then choose a winner from your email list.

Keep your design and copy simple and clean, with some benefit-driven copy on it. I did the 3D book cover image in Photoshop, but you can get this done on Fiverr.com or if you’re happy with a simple 3D cover, just use DIY Book Design.

Boost your post. Once your post is up, you’ll see a blue box on the bottom right hand corner called ‘Boost Post’. When you click this you’ll see a number of options for boosting your post, including people you want to target, your budget, how long you want it to run, and how you’ll pay for it. This is a great way of getting audience engagement to develop brand awareness and grow your following.

Spending and frequency. You can spend as little as $5 to boost your post. I started out spending $20 on a week-long boosted post, and I did one giveaway a month for the first few months. When I got more comfortable using boosted posts, I started doing two giveaways a month, and increased my budget to $50. The more money you spend, the more people see the boosted post, and the more signups you’ll get. Make sure you check your boosted post at least daily to be sure you’re getting results and not wasting your money.

Targeting your audience. Getting the right target audience for who will see your post is really important. It’s also a really cheap way of getting results. When choosing who you want to see the boosted post, it’s better to have a smaller, targeted audience, rather than making the audience as broad as possible. Narrow your target audience so they like one interest AND another. For example, they like Goodreads AND a certain author.

I measured my results by how much I paid for each subscriber. I checked how many subscribers there were in Mailchimp and divided the amount I spent for the ad by the number of new subscribers gained. I typically spent 25 cents per new email on my list.

Once you have a bit more experience with boosting posts, you’ll want to move on to using Facebook ads. These are a little more complicated, but they allow you to refine your targeting and give you more control over the audience you show your posts to.

Tip: I didn’t find Facebook ads worked to get people to directly buy, but getting them to sign up for a freebie was fairly cheap and easy. Once they were on my email list I could then foster a relationship, which made it easier to generate pre-orders and sales.

7. Start sending your email newsletter

Now that you have subscribers, you need to implement an email marketing strategy. This includes continuing content, author interviews, and book giveaways to keep readers engaged and grow your email list.

I designed a newsletter using Mailchimp’s free email designer. I send my newsletter out quarterly, but you can choose how often you want to do one.

My newsletter includes upcoming book giveaways, competitions I’m holding, and recommendations for books I’ve read. I also choose one subscriber each newsletter issue to win one of the books I’ve recommended in my newsletter. Again, everybody likes a benefit, and it helps ensure they’ll engage with the newsletter and open it to find out if they won.

In addition to designing my newsletter in Mailchimp, I also design a similar page on my website. It takes more time, but the benefit is I can share it across social media, and it is mobile ready so people can read it on their phones.

Here’s an example of a newsletter I sent out.

In today’s highly competitive publishing space, we must all be much more than just authors. No matter what publishing route you take, to be a successful author you’ll need to promote yourself and your book. Building an email list fuels your platform and helps you develop direct, long-lasting relationships with your readers so you can sell more books.

A Note About GDPR

Depending on where you live and the audience you’re targeting, you may need to abide by General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) rules when you run contests or giveaways. GDPR is a set of rules designed to give EU citizens more control over their personal data. Here’s a plain-English guide to staying on the right side of the law.

February 4, 2019

Voice Is How You Dance on the Page

Photo credit: PhotoCo. on Visual hunt / CC BY

Recently, after a writing workshop, I was having dinner with a long-time bestselling author, book editor, and literary agent. The question arose (as it often does in such contexts) of how to counsel new and early-career writers whose efforts appear low quality—and if you can tell the difference between writers who will eventually succeed in the market and those who will not.

Such questions always spark energetic debate. My old standby response is that it all depends on how well the writer can use critical feedback and improve over time. Others discuss the importance of reading. Unsurprisingly, the word “talent” is never far away from such discussions, but it’s rarely considered of utmost importance—just one factor among many.

The bestselling author then brought up that ineffable quality of voice: It’s either there in the writing or it’s not. And some writers haven’t developed or “found” their voice yet. While many structural and development issues can be fixed, no agent or editor can infuse a story with voice if it’s not there to begin with.

In the recent Glimmer Train bulletin, author Scott Gloden says that voice is comparable to how you dance on the page:

It was three years into writing short stories without much guidance that this role of voice finally unlocked for me. I was reading Taiye Selasi’s Ghana Must Go, and somewhere in the opening chapters, she uses the phrase “easy peasy.” Easy peasy. How could something so smart contain such a passingly goofy phrase? But in the context of her voice, it felt entirely natural, nothing lost. It was Selasi dancing out the story, and the rest of that excellent novel is steeped in this same energetic language.

Also in this month’s bulletin:

Research for Fiction Writers by Susan Messer

January 30, 2019

Don’t Focus on Marketing Tactics at the Expense of Strategy

One of the hardest things to do—for any individual, organization, or business—is to define a vision and strategy. It involves diving deep into one’s strengths and weaknesses, while having a clear view of the market opportunities and threats. Talking strategy usually means dealing with uncomfortable realities, as well as risking disagreement with others.

It’s much easier to deal in tactics.

For example, we could have a very benefit-oriented conversation about the pros and cons of certain social media networks, and how to post effectively and engagingly on social media for marketing purposes. But that’s a fairly useless conversation if social media is later determined to be unattractive or unsustainable as part of your overall marketing strategy, given other tactics available to you.

However, tactics are seductive because they are tangible, and offer the feeling of improvement and progress. But what if that progress is taking you in the wrong direction?

My column this month at Publishers Weekly tackles how to reduce your marketing anxiety by getting clear on your strategy first.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers