Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 98

October 17, 2018

How to Research Your Writing to Ensure Technical Accuracy

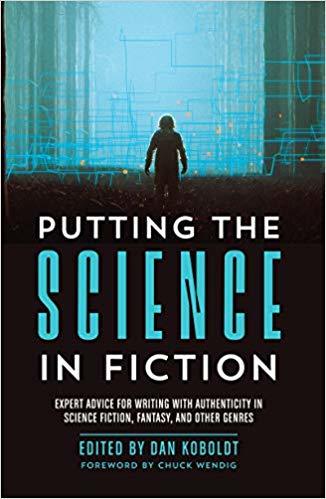

Today’s guest post is by novelist Dan Koboldt (@DanKoboldt), author of Putting the Science in Fiction.

Science and technology are fundamental elements of many literary genres. Unfortunately, the depictions of these subjects in books and movies are entirely fiction.

A classic example of this is in the movie Avatar, when the character played by Sigourney Weaver uses a micropipette. These hand-held instruments are used in a laboratory to move tiny, precise amounts of liquid from one tube to another. They’re a vital—and expensive—piece of lab equipment.

There’s just one rule for using a micropipette: they must be held upright. If you turn a micropipette upside down, the liquid that it just picked up will get into the mechanism. And that’s exactly what Sigourney Weaver did while using a micropipette in Avatar. Amusingly, the makers of that micropipette, Eppendorf, even chided them about it on Twitter. The amount of lab equipment that’s irreparably destroyed on-screen would give university accountants a heart attack.

Space explosions are another trope with no basis in real-world science. Space is a vacuum, so spaceships (and death stars) don’t explode in massive fireballs (fire requires oxygen). Realistically, a spaceship that loses hull integrity would decompress and implode. Oh, and you wouldn’t hear an explosion either, because sound waves also can’t travel through space’s vacuum.

Researching Your Writing: Source Reliability

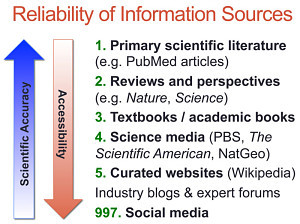

These are just a few of the misconceptions that pervade popular science fiction. Many, if not most, could have been avoided if the writers spent some time doing research. During this crucial phase, not all sources are created equal. Let’s take a brief tour of the various places you might get information, from most accurate to least.

The most scientifically accurate sources are the papers published in peer-reviewed journals, but these can be pretty dry for the casual reader. I personally read a lot of scientific reviews, which summarize the current state of knowledge about a topic while drawing on that literature. After that, textbooks and reference books tend to be very reliable information, though these (let’s be honest) are prohibitively expensive.

Science media aimed at a general audience—such as PBS, The Scientific American, and National Geographic—lose some of the nuance, but are much more accessible to non-technical readers. Curated websites like Wikipedia are nice resources for casual reading and research, and tend to be updated as new discoveries emerge. Still, these are written and maintained by the general public, so use with caution.

You’ll note that social media ranks as #997 in terms of scientific accuracy. Remember, social media companies are for-profit organizations. You don’t pay to use them, because you are the product. An increasing proportion of the “sources” you may encounter have paid to show up in your feed or search results. Simply put, anything served to you by a social media network should not be treated as factual information. Especially when you’re performing research that you plan to use for your own work.

How and Why to Ask an Expert

All of the things I’ve discussed so far are passive research sources—that is, materials you go find and read on your own. However, one of the best ways to research your writing is to ask a real-world expert. I do this all the time. For the past few years, I’ve hosted guest posts from numerous experts for my Science in Sci-fi, Fact in Fantasy blog series. If I need spaceship design advice, I can ask a Boeing engineer. If I need to know something about brains, I ask my go-to neuroscientist.

This works well for two reasons: first, because real-world experts are usually versed in the current state of the art for their field. They don’t just read those research papers; they write some of them. Second, most scientists, engineers, and other professionals love talking about their work. All you need to do is find one and approach them the right way.

If you’d like to ask an expert for advice, here are some tips to make sure it’s a pleasant experience for all parties involved:

Do your homework. Give some thought to the technical subject in question (and how it applies to your story) before you start the conversation.

Briefly provide some context. In a few sentences, summarize your story and how the technical element comes into play. This will help the expert understand what you’re looking for.

Be considerate of their time. Experts don’t exist for the sole purpose of answering writers’ questions, so don’t monopolize their time. Keep your interaction polite, concise, and respectful.

Recognize that you might need a different expert. People who work in medicine, science, and other technical fields tend to specialize. You might find out in the course of conversation that you need a different type of expert.

Balancing Accuracy with Story

Balancing Accuracy with StoryYou’ll probably get far more information from your research than you can actually use in your writing. It’s up to you to select the most important elements to convey on the page, and to leave the rest out. If you have to choose between telling a great story and being technically accurate, go with the former. Story should come first.

If you enjoyed this post, I highly recommend Dan Koboldt’s Putting the Science in Fiction. It’s a collection of expert advice from scientists, engineers, medical professionals, tech experts and more, who debunk the myths, correct the misconceptions, and help writers create more realistic yet engaging stories to satisfy discerning readers.

October 11, 2018

How to Understand Your Reader’s Level of Awareness to Grow Your Fanbase

Photo credit: derpunk on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-SA

Today’s guest post is by Dave Chesson (@DaveChesson) of Kindlepreneur.

The more educated a customer is about a product, the more they’ll understand what they are looking for—and therefore be more likely to buy it.

Imagine a reader who thinks they like science fiction books, as compared to one that can specifically tell you they love sci-fi military space marine adventures. The latter is more likely to know what they are looking for and quicker to buy the book when they see it.

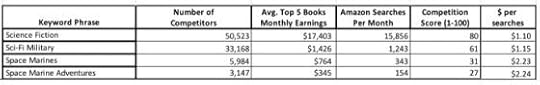

While more people may type “science fiction” into Amazon’s search box, there is more money being made (per search) for the phrase “sci-fi military” and even more for “space marine adventures.”

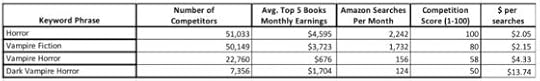

Numbers from KDP Rocket

Readers start their journey in a very broad sense, and over time, as they gain experience and understand more about what they are looking for, they refine their searches. By understanding the awareness level of a reader, we can better position our books or better craft content on our author websites that not only brings in more potential readers, but helps convert them into long-term fans. This all begins with the understanding of the five levels of awareness.

The Five Levels of Awareness: A Buyer’s Path to Success

In 1966, Eugene Schwartz, a renowned advertising specialist, described the buyer’s journey using the five levels of Awareness in his book Breakthrough Advertising.

These 5 levels are:

Unaware: People who don’t know there is a better way.

Problem aware: Aware of the problem, unaware of the solutions.

Solution aware: Aware of solutions in general, not yours specifically.

Product aware: Aware of your product, but haven’t bought it.

Most aware: Your best customers. Brand loyal.

A modern day example of this would be if someone overheard how a food delivery service made someone’s life easier (unaware). So, they do a search for “how to get any food delivered” (problem aware) and they find this article. As they research more, and progress through the stages of awareness, they discover that smoothie delivery services exist—something they love. Now, they just need to figure out which smoothie delivery service to use (most aware), so they read this article.

Which article do you think made the sale in the end? The second one, right? So, how can this be useful to an author?

Using Eugene’s Principles in Book Sales

When readers go to Amazon to find their next book, they start by typing something into the search box. Upon doing this, Amazon presents to them list of books.

However, if the reader types something very broad like “self-help” or “fantasy” do you really think Amazon will be able to show the perfect match? Probably not. Instead we are witnessing a reader who is probably in Eugene’s “problem aware” or “solution aware” level.

It is for this reason that even though broad keywords for your book might get lots of traffic, they are very competitive and also not at the “most aware” level—thus they are less likely to actually land the sale.

To illustrate this, here is a nonfiction and fiction example.

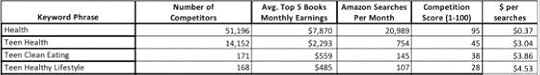

Numbers from KDP Rocket

Numbers from KDP Rocket

As you can see, even though the broad keyword gets more searches, they are both more competitive and have worse conversion (fewer sales as a percentage of searches). However, as we niche down, the long-tail keywords have better conversion and less competition.

So, when you do your keyword research, you want accurate, long-tail keywords that still get traffic. To learn more about this, check this article out if you write fiction, and this one if you write nonfiction.

Using Eugene’s Principles in Author Websites

A lot of authors have websites but don’t know what to write about. Eugene’s awareness levels can help.

While it’s fun to write about what you’re doing, writing, or thinking about, this only helps if we already have fans reading your stuff and care to know about your comings and goings in the author world.

If you’re like many, and don’t already have a bunch of raving fans, here are two article types any author of both fiction and nonfiction can write about that meets Eugene’s Most Aware level in style.

The Power of Lists and Your Favorite Things

We all have a list of favorites. It could be a list of your favorite books or a list of your favorite writing places. The point is, lists are a beautiful thing so long as you aren’t broad.

Like our discussion on long-tail keywords above, writing about a “List of your favorite books” resides in the unaware level territory. However, writing about your “List of favorite Victorian era romance novels” or your “List of Best Nanotech Fiction books” can really win the day.

Here are examples of authors using this method and reaping the benefits:

Jane’s own list of best books on writing

Top sci-fi books created a list of books like Ready Player One

Casey Calouette listed the best science fiction weapons ever

Self Publishing School listed their favorite nonfiction writing prompts

AMZ Prof listed the best lights for reading

A test prep site listed their favorite study guides

Early Bird Books wrote about the 5 scariest vampires in literature

Using a site like SimilarWeb.com or Ahrefs.com, it’s easy to see that those articles are one of the best traffic generating articles on their entire sites. So, ask yourself, what list can you start writing?

Writing Review Articles

Lists are wondering things. Reviews are even better. Not sure what to review? Here are a few ideas:

Review of a favorite book in your genre

Review your favorite tool or software

Review conferences you’ve been to

Review your favorite writing or publishing training you’ve taken

Review the products you use—like coffee, Red Bull, or wine or any other author necessity

My wife plans ahead for my “writing bouts”

An example of this in action was a review I wrote on ProWritingAid. I didn’t write about a mistake I had (unaware) or why an author needs an editing software (problem aware). Instead I focused on the “most aware” stage: it is a review of a particular product and even offers a major discount for readers. However, because this was for my readers, I ensured it covered bits of the other levels so that someone new could follow along.

Parting advice

Eugene Schwartz illustrated the importance of getting our content or product displayed in the “most aware” levels. This doesn’t negate the importance of the other levels. However, it does go to show the importance of things like specific long-tail keywords, and the end state of a buyer’s mentality. Using these principles we can get our books in front of the reader who is ready to buy, and our content in front of the right person who’s truly self aware about what they want.

October 10, 2018

5 Tips for Selling Your Books at Events—on a Budget

Photo credit: craftivist collective on Visual hunt / CC BY-NC-ND

Today’s guest post is by Chrys Fey (@ChrysFey), author of Write with Fey: 10 Sparks to Guide You from Idea to Publication.

Being one of many authors at a book festival or signing event can be pricey when you add together the cost of the table, books, swag, travel, meals, and anything else the event requires of you. Sometimes it’s challenging to make back the cost of your books and the price of the table. So, finding cheap but cool things to use at book events is essential.

1. Create business cards for free ebooks

Do you have an ebook that’s permanently available for free at Amazon or another retailer? Create a business card with the cover on one side and the book’s tagline and a QR code on the other side. If you can fit it in, include a short review—just a few quoted words works great. Then hand out the cards to anyone and everyone who stops at your table or passes by. Let them know your ebook is free and that the QR code will take them right to the page to download.

With VistaPrint, you can get 500 standard business cards with color on the front and back for about $30—and they always offer promo codes for 20% off.

If you want to charge for your ebook

BookFunnel allows you to create unique codes so readers can download ebooks for free. Each code works for one reader. You can then use these codes as a way to allow readers to purchase your ebook at in-person events (they redeem the code any time after purchase, one-time use), or you can use codes as a free bonus for people who buy the print edition. Note: You have to be on BookFunnel’s MidList or higher pricing plans to generate codes. If you already use BookFunnel, then this isn’t an extra expense for you. Score! Go here for more information on BookFunnel’s Print Codes.

2. MailChimp Subscribe

If you have a newsletter, you can get verified subscribers by using a tablet and MailChimp Subscribe (for iOS and Android) that allows you to get email sign-ups when you’re offline. Then when you get Internet access, those subscriptions will be added automatically to your list. No more paper forms. No more worrying about being GDPR compliant, because you will be! This app takes care of all the hassle. In your newsletter’s subscriber’s list, you’ll be able to see the new sign-ups from your events, and the source will be listed as “MailChimp Subscribe.”

3. Square

An easy way to accept credit and debit card transactions at events is to use Square. It’s a device that plugs into your phone’s jack. The best part: you can these for free! All you have to do is sign up and they’ll send you one in the mail. Once you get it and plug it into your phone, you’ll have to sign in to get your account. And just like that you’re ready to go! FYI: There’s a small fee per credit card swipe, similar to PayPal fees.

4. Dollar Tree

My favorite store is Dollar Tree, where everything is a dollar, my favorite price tag. Surprisingly, they have great products. Their glassware and kitchen utensils are quality items, and I often get makeup, nail polish, and bath supplies there, too. And I get decorations for my book event table.

Part of my author logo involves sparks, a theme that carried over from my blog, and when Fourth of July came around, I found some cute star decorations at Dollar Tree that went perfectly with my theme. Once, I bought baggies of plain shells from Dollar Tree and painted them bright colors with black heart outlines and gave them away as swag. And my mom found felt Halloween stickers to complement her Halloween picture book. I always find neat items and use them for giveaways—coffee mugs, votive candle holders, and ceramic figurines.

Dollar Tree Book Event Table Décor Ideas

Flameless candles

Picture frames

Chalkboards/white boards (for prices)

Balloons

Artificial flowers and vases

Battery-operated string lights

Holiday and seasonal décor

Candy and candy dish

Kids’ toys (plastic handcuffs are perfect for crime writers)

Birthday party favors and décor

You never know what you’ll find at Dollar Tree until you go looking. If you don’t have one nearby, use their website where you can order in bulk.

5. Do-It-Yourself Swag

Swag can get expensive, especially if you order paper swag like bookmarks and postcards, as well as little gifts for your readers. Popular swag items include pens, magnets, keychains, and small notepads or Post-it notes. You can save a lot of money by making swag items yourself. Many of the materials needed for DIY projects can be bought in bulk, which is ideal when you need 50 to 100+ pieces of the same thing.

Coasters are a neat swag item that I’ve received from other authors and love to use. These are usually some type of thick cardstock, but Patricia Lynne shares how to make coasters out of tiles. On Patricia’s blog, she also explains how you can make your own magnets.

Other DIY Swag Ideas

Ornaments made out of old paperback book pages (books too beaten to donate).

Salt dough ornaments cut out with cookie cutters in the shape of something related to your book. There are cookie cutters in just about every shape, including mermaids, unicorns, crowns, and much more.

Hand-painted rocks. Many cities have their own fun project that encourages residents to paint rocks and hide them in public for others to find, like Brevard Rocks. Why not use the inspiration for that to create hand-painted rocks for readers to take home and set in their garden? These stones can be palm-sized or small.

Hand-painted rocks. Many cities have their own fun project that encourages residents to paint rocks and hide them in public for others to find, like Brevard Rocks. Why not use the inspiration for that to create hand-painted rocks for readers to take home and set in their garden? These stones can be palm-sized or small.Buy pin backs to make your own pins/buttons.

No matter what you do at an event, or what you are offering as swag, or how you decorate your table, be proud of it and your books. That is key.

Your turn: What are your cheap and cool book event tips?

For more information like this check out Chry’s Fey’s Write with Fey: 10 Sparks to Guide You from Idea to Publication.

October 9, 2018

Don’t Be Too Smart or Clever in Your Book Descriptions

Photo credit: Judy ** on Visualhunt / CC BY-NC-ND

One of the most compelling panels I attended at BookExpo 2018 was “Preorder Sales Secrets from the Publishing Pros.” It included book marketers from HarperCollins, Kensington, Macmillan, and Penguin Random House. An overarching point of the panel was that running preorder campaigns helps publishers gauge what marketing appeals succeed with the target readership. Preorder campaigns act like the canary in the coal mine: bad results indicate that the marketing direction or metadata could be wrong.

For one example, a marketer admitted that her department didn’t want to call an upcoming vampire book, well, a vampire book. Because the department was coy in the marketing and advertising copy, and avoided using that label, reader response was poor. The publisher received the message loud and clear: if you have a vampire book, say it’s a vampire book. Subtlety is not your friend.

In my latest column for Publishers Weekly, I explore how thinking your reader can help you write better book marketing copy. Read the column.

October 8, 2018

Writing Immigrant Characters: Avoiding Exoticism

During the last weekend in September, I had the good fortune to speak at the Writer’s Digest indieLAB, where children’s author Zetta Elliott gave the keynote address. She spoke about the great need for children to read stories that act as mirrors and referenced an essay by Rudine Sims Bishop, “Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors.”

In that essay, Bishop writes: “When children cannot find themselves reflected in the books they read, or when the images they see are distorted, negative, or laughable, they learn a powerful lesson about how they are devalued in the society of which they are a part. Our classrooms need to be places where all the children from all the cultures that make up the salad bowl of American society can find their mirrors.”

I was reminded of Elliott’s talk when I read May-lee Chai’s experience in elementary school, when she was forced to read a story about a Japanese-American girl embarrassed by her mother, who spoke in broken English—which was supposed to be funny.

I wanted to sink into the earth when my class read this story aloud. The plot of the story—the narrator learning to appreciate her mother despite her “flaws”—was offensive. Worst of all, it was the only story in all my five years of elementary school that even had an Asian character in it.

I remember being afraid that my classmates would think that my family and I were like the characters in that story, which was flat and certainly did not celebrate immigrants’ ability to code-switch.

Read Chai’s full essay in the latest Glimmer Train bulletin.

Also this month in Glimmer Train:

Novel and Story by William Luvaas

September 26, 2018

Overcoming Creativity Wounds

Photo credit: Adam Foster Photography on Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC-ND

Today’s guest post is by Grant Faulkner, executive director of Nanowrimo and author of Pep Talks for Writers.

For writers unaware, Nanowrimo is National Novel Writing Month, where writers around the world challenge themselves to write 50,000 words in 30 days. It starts November 1. Learn more.

Somewhere deep within most of us, there is a wound. For some, it’s vile and festering; for others, it’s scarred over. It’s the type of wound that doesn’t really heal at least not through any kind of stoic disregard or even the balm of time.

I’m not talking about a flesh wound, but a psychological wound—the kind that happens when someone told you in an elementary school art class that you didn’t draw well, or when you gave a story to a friend to read in the hopes they would shower you with encouragement, but they treated the story with disregard. We put our souls, the meaning of our lives, into the things we create, whether they are large or small works, and when the world rebuffs us, or is outright hostile, the pain is such that it might as well be a flesh wound. In fact, it sometimes might be better to have a flesh wound.

To be a creator is to invite others to load their slingshots with rocks of disparagement and try to shoot you down.

I’ve been hit with many such rocks. Perhaps the most devastating rock was slung by a renowned author who I took a writing class from. My hopes were ridiculously high, of course. I wanted her to recognize my talent, to affirm my prose. I wanted her to befriend me, to open up the doors of her mind and show me the captivating way she thought. I was young, and I walked into her class as if I was a puppy dog, my tongue wagging, expecting to play. My first day of class might as well have been the opening scene of a tragic play.

When I turned in my story for her feedback, not only did she not recognize my talent, but she eviscerated my story. She might as well have used shears. “No shit!” she wrote in the margins of one page. I met with her in her office hours to ask her questions and hopefully make a connection, but she was equally cold and cutting, offering nothing that resembled constructive critique, just the pure vitriol of negativity. She said my story was boring, pretentious. She said my dialogue, which others had previously praised, was limp and lifeless.

That was the only time in my writing life when I felt truly defeated. It was the only time in my life when I was utterly unable to pick up a pen to write anything. I’d been critiqued in many a writing workshop before—relatively severely even—so I wasn’t a naive innocent. But I’d never experienced such slashing and damning comments. I’d always been resilient and determined in the face of such negativity, but this time I lay on the couch watching TV for several days afterward, my brain looping through her scissoring comments again and again.

I hope you haven’t experienced anything like this, but, unfortunately, almost every writer I’ve talked to has a similar story. When something you’ve created—something that glows so brightly with the beauty of your spirit—meets with such an ill fate, it can create the type of wound that never truly closes. You can stitch it closed, but the swelling puss within it can still break the stitches back open. It’s always vulnerable to infections, resistant to salves. Time heals . . . a little, but not necessarily entirely.

The question is how to begin again, how to recover the very meaning and joy that we found in our first stories—to recover the reason we write. It’s difficult. I still see that “No shit!” in the margin and sometimes wonder if I have anything worthwhile to impart, or if the quality of my prose allows me to impart my stories and ideas in an interesting and engaging way. I’ve wondered this even after getting a story or essay published. I wonder if somehow the editor didn’t realize what an imposter I am. I wonder this even now, as I write this book on the subject of writing of all things, a book that has a publisher, a book that has been guided by a fine editor, a book that is sold in stores. Wounds can open when least expected, and from them self-doubt riles with a snarl.

This pep talk is titled “Overcoming Creativity Wounds,” which is quite different than healing them. To overcome means to prevail. To overcome means not succumbing to the wound, but to bandage it and move on. To overcome means that you have to tell yourself that you’re creative, that the only significant thing you’ll accomplish in this life will come from that singular imaginative force that is you—that you deserve to frolic with words, to explore worlds, to dance with the characters in your stories (or follow them down dark alleys and go to war with them). To overcome means to say no to the naysayers and yes to your indomitable will. (Trust me, you do have an indomitable will, even if you’re thinking about turning on the TV.)

This pep talk is titled “Overcoming Creativity Wounds,” which is quite different than healing them. To overcome means to prevail. To overcome means not succumbing to the wound, but to bandage it and move on. To overcome means that you have to tell yourself that you’re creative, that the only significant thing you’ll accomplish in this life will come from that singular imaginative force that is you—that you deserve to frolic with words, to explore worlds, to dance with the characters in your stories (or follow them down dark alleys and go to war with them). To overcome means to say no to the naysayers and yes to your indomitable will. (Trust me, you do have an indomitable will, even if you’re thinking about turning on the TV.)

To overcome is to write your story, to believe in it.

There’s no one recipe to overcome a creativity wound, but putting a pen between your fingers and then resting it on a piece of paper is a pretty good start to finding one. Start writing. Keep writing. And the wound will fade and even fuel your work, even if it might not truly go away.

September 25, 2018

3 Principles for Finding Time to Write

This week, I’m a guest on the Marginally podcast, which is about writing (or the creative life) when you also hold a day job. I immensely enjoyed the conversation with Olivia and Meghan, not least because it was free of the usual nuts-and-bolts of how to get published. Instead, we discussed the vexed issue of writing and money.

In every podcast conversation or interview, there is at least one question where I wish I’d offered a better, more considered answer. This one was no different and it was related directly to the premise of the podcast: How do you navigate the writing life when you have an intense day job? Does such a thing as balance exist?

Few things are more personal than making time or finding balance. Today, my idea of balance is keeping email off my phone and only working about four hours on the weekends. Ten years ago, while I held a corporate job, my idea of balance was not looking at email after 10 p.m. daily. Each of us must deal with shifting personal circumstances (e.g., our family needs us, we need a day job for health care) and psychological demons (e.g., that awful teacher who told us we’d never make it as a writer).

Unless you’re a trained Zen monk, or you experience perfect days, harnessing your energy consistently and productively takes years of trial and error—of learning how to establish and improve habits that support your creative goals. And that requires some modicum of self-awareness.

That said, here are a few principles that I find universal.

1. Ideal conditions never arrive.

This is the biggest trap of all: I’ll start writing when…

When I have the time, when my kids are grown, when I quit this job, when I have more job security…I’ve heard it all.

While such thinking can be rooted in self-sabotage and fear of failure, most of us do face a tangible barrier to getting writing done. It’s just that the better conditions we think will arrive never do. A new barrier inevitably takes its place.

I’ve always loved Claire Cook’s story of how she wrote Must Love Dogs. As a middle-aged parent, the only time she had was the five minutes in her van while waiting to pick up her kids at school or soccer practice or whatever. And so that’s what she used. She wrote a whole novel that way—and it launched her very successful career.

So, the best thing you can admit, straight away, is that you will never have ideal conditions for writing. You may know that already. But have you considered that having ideal conditions may hurt your writing?

2. Too much freedom can hurt your art.

I’ve heard all the excuses for not writing, and I’ve also observed the people who have absolute freedom to write when, how, and where they wish. This rarely confers them any advantage. In fact, writers who are least in need of their writing to pay off tend to be the most concerned with monetary gain or recognition. Because that’s the most common way we determine if what we’re doing has any value, especially in the US. If we can’t show a pay off, how do we justify the activity? We become uncomfortable and guilt sets in. We blame ourselves for being frivolous or self-indulgent.

Even if guilt is not an issue, too much freedom can also produce writer’s block, prolific experimentation that goes nowhere, and a paralyzing lack of focus.

Borges did his best work when burdened with a day job. Louisa May Alcott wrote her best work because she had to earn money to support her family—and she was told a story for young girls would sell. Austin Kleon keeps a file of creative people whose physical shortcomings led to their greatest work.

I often say the friction between art and business can be productive—it forces innovation and can be the basis of creative work and not just a barrier to that work. As Kleon mentions, Ryan Holiday’s The Obstacle Is the Way elaborates on this philosophy—the philosophy of stoicism. Marcus Aurelius said, “The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way.”

3. The writing life is not without compromise.

Or, more starkly, it’s not without sacrifice. Some writers are known to be lousy family members. (Here’s a piece on whether great novelists make bad parents.) That’s not to say being a writer gives anyone permission to be cruel or neglectful—but that a devotion to writing means less time and energy for everything else. Most writers thank their family and friends profusely in acknowledgments (or in award acceptance speeches) because they understand that we express our love through attention, and attention for our work means less attention for everything else.

I have no children and few family obligations, and so issues of compromise for me look quite different. It’s more about: How much am I willing to give up this other thing that I love? Am I willing to give up TV time? Cooking? Sleep? Running? Travel?

Making a sacrifice for one’s writing can be scary, because the energy cost is high and a tangible return is rarely guaranteed. If you don’t have supportive loved ones, it’s all the more difficult.

If all else fails, take the pressure off yourself.

This is something I mentioned during the podcast. There are periods in your life when focused, sustained writing is simply not realistic. You have other priorities, work you enjoy, or unique demands. Acknowledge it and stop beating yourself up about it—it’s possible to expect too much of yourself. John Cleese said, “If you’re racing around all day, ticking things off a list … and generally just keeping all the balls in the air, you are not going to have any creative ideas.” During some stages of your life, you will not get writing done.

The big life challenge is having the self-awareness to recognize your situation for what it is. Either it’s the best you can do right now or you’ve made the wrong turn at Albuquerque. If you’re not sure of your status, then ask: What’s the one thing you know you must do, but you’ve been avoiding it or putting it off?

I’m often asked how I’m so productive or keep things in balance. Irony: when I last wrote about this subject, it was because I was disappointed by my answer during a podcast! Keep in mind that a writer who pulls off the balancing act doesn’t necessarily mean they feel balanced—and they may not even know how they manage it. While it doesn’t hurt to try out someone else’s work-life approach, finding time or balance is ultimately a challenge we each face alone, in negotiation with our loved ones. And it almost always comes at the cost of something else.

September 24, 2018

Pre-Publication Marketing: A Van Tour to Bookstores

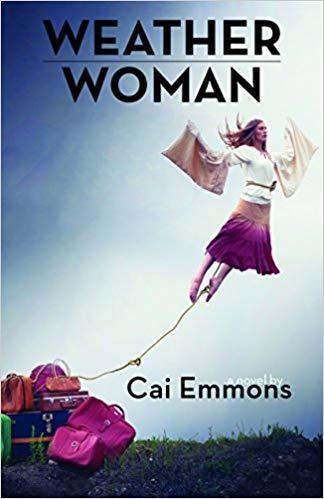

In November, Weather Woman by Cai Emmons will release from Red Hen Press. To spread the word this summer, Cai drove “the Weather Woman van” to independent bookstores in the Western United States, distributing advance reader copies and chatting with booksellers. She’s also speaking at a variety of venues across the country (see the full list).

Given the unusual nature of her pre-publication marketing, I asked her why she’s pursued this strategy and what the payoff has been thus far.

Jane Friedman: What inspired you to do this van tour to bookstores?

Cai Emmons: I felt that my first two novels could have had a wider readership, so when I received a contract for my third book from Red Hen Press, I decided to educate myself about book promotion as thoroughly as I could.

Red Hen was emphatic that I needed to take responsibility in getting my book out there, something Harcourt and HarperCollins had not said to me so directly. As I went about educating myself, a remark of yours made a deep impression on me: You said that it made no sense for a writer to force herself to do things she hated to do or was bad at, but that she should do the things she liked and was good at. That comment prompted me to evaluate my strengths. I’m pretty good at talking to people one-on-one. And I love booksellers.

As I was thinking about this, I spotted the owner of my yoga studio in a yoga pose on the side of a bus. Then the idea came to me: I would put my book cover on the side of a vehicle and drive around to independent booksellers and chat them up in advance of publication to encourage them to carry the book.

I got hold of a Ford transit van and put a blowup mattress in the back for sleeping. I wrapped the side of the van with the book cover art and some quotes, along with my website and social media handles. Red Hen was very enthusiastic and supportive about the idea, and they supplied me with ARCs to give to the booksellers.

How did you decide where to go?

Sine I live in the Pacific Northwest, I began with a list of bookstores from the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association. Their purview is Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Montana, so I decided to go to those states.

I divided the tour into three legs. The first one was a week long and it took me throughout Western Oregon (up to Portland and Astoria and down the coast). The second tour, also a week, took me up to Seattle (so many bookstores in that one city alone!) and Bellingham, then down through Anacortes, Port Townsend, Bremerton, Bainbridge, and Olympia.

The third and longest leg lasted three weeks, and it began in Eastern Oregon and Eastern Washington (Walla Walla, Spokane, etc.) then to Idaho (Moscow and Coeur d’Alene) then across Montana (Missoula, Bozeman, Butte, Billings), then down through Wyoming and into Colorado because my niece was getting married in Denver. In Colorado I hit Fort Collins, Boulder, Denver, Aspen, and Vail.

In the future I might opt to go south to California, and if I had the time I would drive east, as I have lived in New York and New England and will be going to those places for readings.

How did you arrange your visits? Did people know you were coming? Did your publisher help out?

My publisher had the list of places I planned to visit and sent each bookstore an email telling them who I am, what my book is about, and that I was coming.

But I could not be sure about how long it would take me to get from place to place, so we did not specify an exact time, or even day, only the week that I would be arriving. What this meant is that often the person behind the counter was not the person who had received the email, so I found myself doing “cold calls.” At first that was a little intimidating, but over time I became fairly comfortable initiating conversations and telling people what I was up to.

In general the reception was very positive. People liked that I was getting behind the promotion of my book (and they understood the need for it). I learned to engage with the booksellers not just about my book, but about books in general, and about what it was like to own a bookstore. I now feel even more simpatico with people who have decided to devote themselves to books in this way.

Since the intent of the tour was to cultivate a relationship with booksellers in advance of the book coming out, I tried to follow up my visits with emails thanking them. Many responded suggesting possible events. I will be going to the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Convention in a week and hope to see many of those same booksellers there.

What role did the branded van play?

I intended for the van to serve as a kind of passive publicity, something people would see as they passed me on the freeway, or as they waited behind me at a stoplight. That seemed to be exactly how it functioned. A number of people got in touch with me through Facebook or my website as a result of seeing me drive by. Also, many people flagged me down to engage me in conversation in parking lots and gas stations.

I intended for the van to serve as a kind of passive publicity, something people would see as they passed me on the freeway, or as they waited behind me at a stoplight. That seemed to be exactly how it functioned. A number of people got in touch with me through Facebook or my website as a result of seeing me drive by. Also, many people flagged me down to engage me in conversation in parking lots and gas stations.

A particularly amusing moment was the paraglider in Chelan, Washington, who told me there was a major gathering of paragliders happening that very day. He said that he was sure every paraglider would buy my book because of its cover, which features a woman looking as if she is taking flight!

How do you think your tour will affect sales?

I will get back to you on that once the book comes out!

What kind of financial investment did this involve?

The primary investments here were the cost of “wrapping” the van—a couple of hundred dollars—and then the cost of lodging when I did not camp or stay with friends. Then there was the investment of a chunk of time. But I think this is a project that can be scaled up or down in terms of both time and money. Some other Red Hen authors plan to do modified versions of a bookstore tour.

What did you learn about bookstores these days?

One of the things that was striking to me is that the best bookstores are aware of functioning as a kind of community center, a comfortable and convenient place for people to hang out, bring their computers, maybe their children, drink coffee (and in some place alcohol), and browse books. They are beginning to understand that a sense of community is hard to come by in our culture, and they are trying to fill the gap.

What did you learn about yourself?

The best part of this tour was the way it empowered me. I was forced to really take ownership of the promotion of this novel, something I didn’t do nearly as fully with my first two novels.

In the past I was timid about pushing my book on people, uncomfortable with the idea of being a salesperson. I learned from this tour that I actually do have a sense of how to get my book into the hands of the people who would enjoy reading it without being pushy or boastful. I have even begun spotting readers (people with their eyes in books) in airports—or once on the subway—and handing them a card with a synopsis of the book. In all cases these readers have responded well. If people don’t know about your book, they can’t possibly read it!

Is this something you would do again for another book?

Absolutely. I think it is true that some books are easier to promote this way than others. Weather Woman was easy to pitch in one line: “It is the story of a meteorologist who discovers she has the power to change the weather.” Not all novels, memoirs, or books of poetry are so easy to describe briefly.

Also, the cover art for my book is very evocative. Some covers are not as suggestive and might not provoke the same degree of curiosity. But in general, I think that creating alliances with booksellers is always a productive expenditure of energy. We are in business together, the business of selling books, and we need each other. It is a very natural alliance.

September 20, 2018

5 On: Russell Rowland

In this 5 On interview, author Russell Rowland discusses the big mistake he made with HarperCollins, whether the journey of writing is truly its own reward, why his Indiegogo campaign worked so well, and his experiences with publishing–from one of the Big 5 to self-publishing.

Russell Rowland has published four novels, all set in Montana. He also published a nonfiction narrative, Fifty-Six Counties: A Montana Journey, based on his travels to every county in Montana. Rowland also co-edited an anthology, West of 98: Living and Writing the New American West, with Lynn Stegner. He has an MA in Creative Writing from Boston University, and he lives in Billings, Montana, where he teaches workshops and works one-on-one with other writers.

5 on Writing

KRISTEN TSETSI: You write in one of your Facebook comments, in response to a woman who shared that she continues to write for the love of it in spite of the challenges she’s faced working with small presses, that “The journey is its own reward.”

It seems there’s a period in a person’s writing (or other artistic) life when that sentiment is an easy, 100-percent truth. But then something happens, or a time comes, when “The journey is its own reward” becomes more of a daily affirmation that doesn’t feel true without some deep meditation and reflection.

Did “The journey is its own reward” ever change for you?

RUSSELL ROWLAND: I love this question so much. “The journey is its own reward” is, of course, fabulous in theory but impossible to sustain, especially once you’ve been published. So yeah, I’ve had moments—many of them—when I was in this zone of being satisfied with just being able to do what I love. But there are just as many moments (okay, more) when I wonder why writers who are not very good become incredibly famous and wealthy, and writers who I really admire and respect are still struggling to find a publisher for their next book.

And of course it applies to me, as well. I’ve been fortunate to publish several books, now, but it’s been like starting over from scratch each time. People are constantly saying, “You must be able to get anyone to publish your stuff by now.” And I thought the same thing before I got published. I just assumed that once you got your foot in the door, you established yourself. But as you know very well, it comes down to money, and if you’ve never had a huge seller, it will always be a struggle. So you have to TRY and focus on getting satisfaction from the writing, the occasional great review, the beautiful compliments that come your way. It’s usually enough for me, but I have my dark moments like anyone.

Prior to it being purchased in March of this year by independent publisher Dzanc Books, you’d planned to self-publish The Difference Between Us. Congratulations on the sale! When will it be available, what’s it about, and what inspired it?

Thank you!! I was thrilled to have Dzanc take that book on, and I think I owe that almost entirely to Steven Gillis, who suggested I send it to them when I was doing my Indiegogo campaign.

The book is scheduled to come out in the fall of 2019. It’s inspired by a period of my childhood where we moved to a ranch that was in a very tight-knit community right on the Montana-Wyoming border. A rich construction magnate owned this ranch and he hired my dad to manage it, although I’ve never been quite sure why he hired him, because my dad was a schoolteacher. There were several ranch hands that had been there for years, and they didn’t understand it either, so they resented my dad from the moment we showed up.

It was a very rough period for our family. I used that scenario and threw in a murder, one where the new guy is a possible suspect. And there’s also a twist where, in the process of the investigation, the authorities discover that the victim, who is one of the wealthiest ranchers in the area, was a cross-dresser.

The story is about being different, basically, and being an outsider, even in an area where everyone seems to be pretty much in the same boat.

I love this bit from your website bio: “After deciding to become a writer at the age of 28, he gave himself one year to get published. Fifteen years later, IN OPEN SPACES (HarperCollins 2002) hit the bookshelves.”

I love this bit from your website bio: “After deciding to become a writer at the age of 28, he gave himself one year to get published. Fifteen years later, IN OPEN SPACES (HarperCollins 2002) hit the bookshelves.”

In a 2003 January Magazine interview, you chronicle the litany of what had to be crushing blows (which can only be crushing if they follow very high hopes) as you waited to learn whether In Open Spaces would be published, but it’s now been fifteen years since you reached that goal. Looking back now, how would you characterize that fifteen-year-long year, and how does that period influence how you approach writing now? What’s your current writer-goal?

That period of waiting really was excruciating. Seven editors and three and a half years of delays with HarperCollins sometimes made me crazy. And there is nothing warm and fuzzy about the world of major publishers. I never had anyone giving me any reassurances that they were going to try and make this happen. It was a guessing game right up to the time it came out. I finally had a very young assistant editor take it on, and she left Harper a month before the book was released, so even then I had very little solid footing.

But the release itself was just as magical as I’d always imagined, or more so. They sent me on a big book tour that they paid for, with hotels and everything! I was so ignorant about the business that I just assumed it was going to be that way from there on out. I had no idea that would be the end of that! They actually made an offer on my second novel, but I was still feeling my oats enough that I wanted them to put the second one out in hardcover. My editor told me he thought he could get that for me once the book was finished. So I turned down their offer. But of course he left before I finished the book, and the person they turned me over to rejected the novel. My biggest regret in the business.

My current writer-goal is to continue writing books that hold my interest, and I’m thrilled to be working with Dzanc Books, a publisher I’ve admired for years. Because their reputation is one of quality writers, I’m hoping they won’t try and get me to stick to a genre. I have several books in mind, and if I’m able to finally establish a relationship with one publisher, that would be a dream situation. Oddly enough, although I’ve had six different agents through the years, not one of them ever found a publisher for any of my books. I’ve always either found them myself or had a friend refer me.

You teach writing workshops. How many writers do you usually have at a given time, and how do you run the workshop? Do you assign authors or specific works to read in addition to the writing they’re doing (if so, which ones and why)? What do you most hope they’ll get out of the workshop?

My workshops are falling off a bit, but I still do an occasional online workshop, usually with less than ten people. I don’t assign them readings. I focus on writers that are already well into something, usually novels. So it’s all about the work, giving each other feedback and getting helpful feedback. My main objective has always been helping writers find their own voice, so I focus on what they’re doing right first, and then try and give them suggestions for how they can improve on the areas where they’re struggling. I do a lot more one-on-one work now with people who are working on their own books. That to me is way more satisfying.

Speaking of writing workshops… I’ve seen many negative opinions about the MA/MFA pursuit. Arguments include, “People can’t be taught to write”; “Masters’ programs churn out dull, ‘literary’ clones focused on style over substance,” or (and this may be in the same vein), “The programs discount in their study of fiction writing the rich variety of valid commercial genres.” What was your experience getting your MA, and would you recommend such a program to others? What were the benefits, and in what areas do you think the programs could improve?

I understand what people mean about these masters’ programs cranking out clones. I do think there’s something to that. People who write for other writers. I think the great challenge of every writer who goes through one of those programs is to learn the craft of writing without losing your own voice. I think great writers have a balance of great storytelling and fine tuned craft, and it’s sometimes hard to sustain the latter without losing the former. I saw this happen in our program when people lost their confidence. I would absolutely recommend going to a graduate program, but that’s one of the dangers.

I think MFA/MA programs are a classic example of “You get out of it what you put into it.” Boston University had a very competitive program, with only eleven of us, and several of the people in our program came in with the attitude that they were already writers, which I never understood. There was one guy in particular who spent the entire program arguing his case every time we critiqued one of his stories. He was talented, no question, but it didn’t surprise me that he only published one book. He didn’t think he needed to learn any more. I went in with the attitude that I had some talent but didn’t really know what I was doing, and the people who shared that approach were the ones who seemed to get the most out of it. Plus they were much more fun to hang out with.

But it was hard to make friends in that program. It made me realize that maybe not all writers are the insightful, warm people I had always envisioned. It’s just like any other group of people. Some of them are nasty.

The best thing I got from the MA program was getting in the habit of writing. I ended up finishing In Open Spaces my second year there, and before I arrived, I was struggling to write stories that were four or five pages long.

5 on Publishing

There are probably three big fantasies people have when they imagine being traditionally published for the first time: 1. Their book will be reviewed in the New York Times, which will mean crazy fame and a solid writing career; 2. Their book will be in all the bookstores. Even airports! Which means they’ll have definitely, legitimately “made it.” 3. Doing it even once will be enough.

Of all the writers hoping to be published by one of the Big Houses (or even a smaller press), only a small percentage make it. Making it through even once would seem to be an achievement to last a lifetime. So, as someone who’s done it, what else would you say about these fantasies and how they match up with reality?

I would say that the reality matches the fantasy in terms of what it feels like to be able to tell people that you’ve been published, that your book has been reviewed in the Times (I still love that part), that you’ve made something of a mark.

The part that I never quite understood was the lack of support from the publisher, but it did give me a strong understanding that this is a business where you can’t rely on others to toot your horn. If they do, it’s a bonus. But marketing is up to the writer, even if you’re with a major publisher. And although making it once is really nice, there’s always a part of you that wants to go back to that. It’s one of the hardest things I’ve had to come to terms with, knowing that someone thought I was good enough to be published by a major publisher, that I ended up getting a starred review with Publisher’s Weekly, and sold a lot of copies, but can’t somehow convince someone that I’m still that same writer.

After Harper rejected Arbuckle, you were determined to keep trying to find a publisher for it. Why did you ultimately decide to self-publish, and what did it feel like to commit to that option?

After Harper rejected Arbuckle, you were determined to keep trying to find a publisher for it. Why did you ultimately decide to self-publish, and what did it feel like to commit to that option?

That decision came out of complete desperation. My last publisher had decided not to do any more fiction, and I was getting crickets back from every query letter I sent to agents and publishers, so I honestly felt like it was the only option I had left. It was a pretty low point of my career, although I did enjoy the feeling of being in control of the whole process while I was putting that book together. But in the end, I knew that I will always prefer having a publisher. Self-publishing takes a lot of time that I would much prefer to devote to writing.

You started a Kickstarter campaign to fund your travel through all fifty-six counties of Montana for Fifty-Six Counties, which has since published, and you far exceeded your requested amount during the Indiegogo campaign you launched to fund the self-publication of Arbuckle, which has since released, and The Difference Between Us. What’s the key to having a successful fundraiser as a writer, and can you break down your costs either for publishing yourself or going through smaller publishers? What are the costs associated with going through a small press?

Another great question. I was so fortunate to be able to raise the money for both of those campaigns. I wouldn’t have been able to do the traveling I had to do for Fifty-Six Counties without that Kickstarter. And just as a small side note, the reason I didn’t use Kickstarter the second time was because I learned later that Indiegogo doesn’t have the rule that if you don’t reach your goal, you get nothing. I would have used them to begin with if I’d known that before. The percentage they charge is almost exactly the same.

The key for me was having a strong following already. I don’t think it was the concept of either book that inspired people to contribute. It was having a strong fan base, especially on Facebook, which has been very good to me. You know as well as anyone that I’ve managed to create something of a presence there by posting a painting every day and just sort of being a constant presence. It has never been a contrived thing, so I think that has a lot to do with why it has worked for me. I’m just being myself, posting things that are of interest to me, and things I’m passionate about. And people have responded to that in ways that surprised me.

As far as the costs, I was very pleasantly surprised at how easy it has become to produce your own book, in this age of the internet. And I would point people in the direction of Jane Friedman’s blog for advice on how to go about it. I was surprised to learn that you can actually publish your own book through several different companies at the same time, so I used both CreateSpace and IngramSpark, and they both have a nominal fee for the basic elements of downloading your work and processing it. Less than $100. I paid for someone to design the cover for Arbuckle, and I also paid Z.Z. Wei (way less than he deserved, bless his heart) for the cover painting. I probably should have paid someone to copy edit the book, but I was trying to keep the costs to a minimum.

Those were my only expenses. The books themselves cost about $3 to print, so that’s the major expense. I’m not great at keeping track of how well my books have done, so I don’t really know that about Arbuckle, but because I offered copies of the book as an incentive for people to contribute to the fund, I sold several hundred right up front, which was a good way to get the word of mouth going. But it has been painfully obvious that this book hasn’t done nearly as well as the others by publishing it myself. Sales are way less than any of my other books.

Those were my only expenses. The books themselves cost about $3 to print, so that’s the major expense. I’m not great at keeping track of how well my books have done, so I don’t really know that about Arbuckle, but because I offered copies of the book as an incentive for people to contribute to the fund, I sold several hundred right up front, which was a good way to get the word of mouth going. But it has been painfully obvious that this book hasn’t done nearly as well as the others by publishing it myself. Sales are way less than any of my other books.

This is from the blog post titled “Costly Errors” on your website:

[I want to] apologize to anyone that I treated with that smug arrogance of being published by a major publisher. Because now I know what it’s like to be on the receiving end of that snobbery. The people in the club seldom realize they’re being snotty, I think. But there’s a natural assumption, and I remember it well, that you are in the club for a reason. And that others are not in the club for the very same reason. So now that I know this not to be true, I would like to apologize to the Richard Wheelers of the world, to the Matt Paveliches, the Adrian Jaworts, the Aaron Parretts, and the Tami Haalands. These are people whose writing I greatly admire, and they are people who carry themselves with much more dignity than many of the people in the club. Of course there are exceptions there, too. I have many good friends who have managed to be in the club without letting it go to their heads.

Why do you single out those authors in your apology? And do you think there will come a time when more traditionally published authors will separate from the “club snobbery” and take the same view you now have, that there’s plenty of good work to go around and that sometimes a good writer getting a publisher is a combination of luck, timing, and marketability (which may fall under “timing”)?

How odd that I have no memory of writing this, although of course this is a topic that I’ve been very conscious of since I got published. I guess I picked those particular writers because they are all people who I believe should have received more acclaim for their work, and because they’re friends of mine, so I know from personal conversations how hard it has been to NOT get that acclaim.

I’ve also had very meaningful conversations with people who are incredibly successful and have paid a price for that, as in being away from home much more than they’d like, living in hotels, not having enough time to write or do other things. I’d happily trade places with those folks, but it’s been good to realize that there’s no ideal situation, either. There’s always something that’s not quite perfect.

I don’t think there will come a time when traditionally published authors will accept “the rest of us,” and of course I mean that in a broad sense. There are some who have been very generous supporters of my work, including Larry Watson, Jamie Ford, and Tom McGuane. But my theory on that is that once you’re in that club, you have to somehow justify being there in order to not feel guilty about not being one of those who are struggling to get published.

It’s human nature. I know that’s what I felt like until I got slammed to earth. And being treated like shit by some of these people made me realize that they will probably never get it, that some of it is pure luck.

Not for all of them, of course. I’ve always believed that the real cream rises to the top, so I’ve had to accept that I’m probably not in that category. But I know plenty of very good writers who are good enough to be published by a major publisher, but who simply never got the break. So the people who act snooty about it, and there are plenty of them, are of very little interest to me, which means I’m probably missing out on some good books. But there are plenty of amazing books to keep me reading for the rest of my life, anyway.

I want to get back to The Difference Between Us being picked up by a press. How did this come about, and what’s it been like working with them for the last six months? Have your experiences varied from publisher to publisher?

When I was making a nuisance of myself on Facebook, trying to get people to contribute to the Indiegogo campaign, Steven Gillis emailed me and said I should give Dzanc a try. I have submitted to them many times before, and entered their contests, so I had very little hope that this time would be different. But I suspect he gave the senior editor there, Michelle Dotter, a bit of a nudge, so I will always be grateful to him.

As far as the various publishers I’ve worked with, yes, the experiences have varied wildly. I talked about Harper already. The publisher who did my second book was very small, but they did practically no editing on the book, and I found out later that they might be engaged in some shady practices as far as paying royalties, so as soon as I could manage it, I bought the rights for that novel back and republished it with a company that allows you to do the layout and design work yourself if you choose. They offer editing and layout services at a cost, but I didn’t use those. I used them mostly for distribution, which has been a mixed success at best.

My best experience with a publisher was with Bangtail, a very small press out of Bozeman. Allen Morris Jones runs that press and he published both my third novel, High and Inside, and Fifty-Six Counties. (He has decided not to publish any more fiction, because it just hasn’t been profitable for them.)

Allen works very closely with the author to edit their books, and he designs the covers (he’s fabulous at this, and has designed four of mine). He is also one of the nicest guys in the business. Fifty-Six Counties was a terrific experience and has sold over 5,000 copies, which is pretty unusual for a regional book. So if I ever do another non-fiction book, I will approach Allen again.

Thank you, Russell.

September 11, 2018

6 Questions to Help Nonfiction Writers Find Their Niche

Today’s guest post is by Erica Meltzer of The Critical Reader.

In 2008, I took a trip to the bookstore that altered the course of my career.

I was working as a freelance tutor and had recently been hired to help prepare a student for the Writing (grammar) portion of the SAT. In need of practice material, I went down to my local Barnes & Noble and began flipping through the standard prep books. As I read, I grew increasingly frustrated: in some, the questions were too easy, in others too hard. Some of them targeted concepts that were not tested, or omitted concepts that were tested. And overall, the tone and style seemed somehow…off.

I’d had a handful of gigs writing practice questions for various test-prep companies, but until that point, it had never occurred to me that I could publish my own materials. But as I stood in Barnes & Noble flipping through those books, I thought, “I can do so much better than this.”

Although it would be more than three years before my first book, The Ultimate Guide to SAT Grammar came out, I stumbled upon a couple of key lessons about the business of bookselling that day:

First, no matter how many books have been written about a topic, there is probably some important facet that has not yet been covered thoroughly or well.

Second, a key driver behind success is understanding how you fit into the existing landscape, what distinguishes your work, and why it is likely to appeal to a particular audience.

One of the downsides self-publishing is that you don’t receive support or feedback from publishers about how best to position yourself; as a result, you must be willing to devote time to investigating your market and analyzing your role within it. I write nonfiction, so that’s what I’m going to focus on here, but that said, much of what I discuss here can be applied to fiction as well.

Even if you do not go so far as to type up an actual document, you should be able to answer the following questions.

1. How saturated is your market?

You can get a good sense of the answer to this question with just an eyeball test: do the books on your topic cover a shelf in the bookstore? A couple of shelves? An entire bookcase? (Or, if you’re looking online, how many pages of titles come up when you type in the category?)

If there are already dozens of books available, you’ll need to spend some time reading through them in order to understand what’s been done. As a general rule, the more that’s been written, the more specifically you’ll need to define yourself. For me, this happened to be a straightforward matter: as someone whose verbal score was more than 200 points points higher than her math, I had never been able to tutor all sections of the exam and was in no position to author a general SAT book. If I wanted to write a halfway decent guide, I would have to focus on the verbal portion only.

2. Where are the niches?

Unless you are capable of offering a truly unique perspective, you should avoid aspects of your subject that have already been written about extensively. Instead, try to tailor your expertise to important but neglected sub-topics or sectors of your market. Grateful readers become loyal readers (and are more likely to leave glowing reviews).

For my first book, I deliberately chose to focus on a relatively overlooked portion of the SAT. Although there were several combined reading/writing guides available, there was not one guide that dealt exclusively with grammar in an in-depth way. Having spent years mastering everything from relative pronouns to the subjunctive in various foreign language classes, and then teaching those same concepts over and over again in context of the SAT, I was exceptionally well positioned to write a serious grammar book aligned with the exam.

In addition, there was almost no material designed specifically for students aiming for top scores. Even if they made up only a small percentage of the 1.5 or so million annual test-takers, they still numbered in the tens of thousands and, as I learned when they began contacting me via my blog, they were desperate for challenging material.

In fact, this group proved so enthusiastic that I barely needed to spend money on marketing: both students and parents discussed my books extensively on highly trafficked websites, allowing me to build readership naturally. I followed the same subject-specific approach for my following books, first moving to the more daunting SAT reading and then repeating the process for the English and reading portions of the ACT.

Note: If you’re not sure how to go about matching your expertise to your readers’ needs, spend some time reading through websites and blogs devoted to your topic in order to get a feel for what issues readers face and what questions aren’t being answered. While writing my books, for instance, I spent hours reading a popular test-prep forum so that I could address students’ questions and misconceptions directly.

3. Who are the major players in this genre? Is there a single title or set of titles that dominates the market?

Regardless of what you intend to write about or how many books have already been devoted to that topic, you need to understand your competition. Even if you do manage to suss out a neglected corner of the market, your book will almost certainly overlap with other titles, some highly successful.

The question is: why do the top-selling titles do well? Do they sell briskly because they have a devoted following (as evidenced by hundreds of enthusiastic reviews) or do people buy them merely because they are the only books available (as suggested by a smaller number of lukewarm or generic reviews)?

If the former, you shouldn’t expect to seriously compete, at least not right away; if the latter, you might have a better chance of breaking in. I was lucky in that most of the top-selling titles in my genre held that position simply because there were few alternatives; given the option, many readers were happy to try something new.

4. Are any successful titles self-published?

The appearance of self-published books among the more popular titles signals that readers are open to trying works by less established authors. While it isn’t always possible to tell whether a book is self-published, check the book’s copyright page to see if an established publisher is listed.

If your market is dominated by traditionally published titles, you are not necessarily at a disadvantage. Because traditional publishers are by necessity driven by their bottom line, they are less likely to take on potentially risky projects. As a result, there may be ample room for new voices or fresh takes on familiar material.

When I finished my first book in 2011, for example, the same few names had essentially defined the SAT/ACT market for decades, and there was plenty of room to shake thing up—even though the market appeared closed from the outside. The standard books were written either by tutors who knew the tests well but weren’t particularly well versed in the actual subjects, or by classroom teachers who knew their subjects well but had limited knowledge of the exams.

With the advent of platforms like CreateSpace, tutors who were also math or English experts could publish materials that had been extensively tested with students. Because those books did well, other tutors were encouraged to publish guides, fundamentally reshaping the market. Today, about 10 of these books typically rank among the top-selling SAT/ACT guides on Amazon.

It’s gratifying to know that I’ve played a role that shift: shortly after his first book was released, the author of the top-selling ACT Science guide informed me that my books had inspired him to go ahead and write his own. Like me, he had noticed a gaping hole in the market—there was not one guide devoted solely to that subject—and decided to plug it.

5. What do the existing books do well, and where do they fall short?

As you read, notice—and preferably jot down—what aspects you find most enjoyable and engaging, and which ones you find wanting. While it is important to consider obvious factors (content, tone, style, and flow), you should also consider subtler issues such as formatting and font. When I went through the existing SAT prep books, for example, I noticed that from a visual standpoint, their questions often looked nothing like those on the exam. As a tutor, I understood that students were frequently thrown off by deviations from the actual test and wanted to practice on material that felt authentic in form as well as content. As a result, I made sure that my practice questions were identical in terms of font, size, and spacing, to those on the real exam. That kind of subtle attention to detail helped reader feel that my books were preparing them for exactly what they’d face and made them more inclined to trust my work.

And finally…

6. What do you do better, or know more about, than anyone?

In other words, what specifically can you offer readers that will cause them to bypass other works and zero in on yours? Obviously, this isn’t a zero sum game—readers will often buy multiple books on a given topic—but you must know what sets you apart. All the market research in the world won’t matter unless you are genuinely invested in your topic and able to write about it with ease and (ideally) flair. Readers almost certainly won’t be passionate about your book unless you are as well. This is the biggest question you need to answer, preferably before you even write a word.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers