Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 100

August 2, 2018

How Traditionally Published Authors Can Repackage and Self-Publish Their Backlist

Today’s guest post is by author Jess Lourey (@jesslourey).

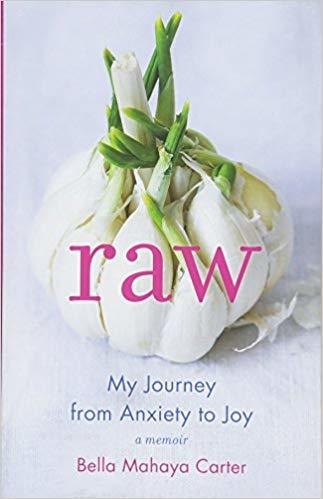

My first published book, May Day, was released in March 2006. In the intervening twelve years, I’ve released ten more books in that series, watched glowing reviews come in, made an average of $6,000 a year off them (less than minimum wage), and grumbled to myself that if I had only self-pubbed the series, I’d be rolling in the hay by now.

Fast forward to June 2018.

I got my rights back to the first ten books in that series. I hired a cover designer, bought book layout software and the computer I’d need to run it, and took a quick and dirty dip in the marketing pool. It’s too soon for me to provide sweeping data on what works best, but one thing I know for sure: successfully publishing a book is a hundred times harder than I’d imagined (apologies to my original publisher for my negative thoughts).

Read on for the lessons I’ve learned. Use it as a checklist for your repackaging your own backlist, a behind-the-curtain peek at the life of a hybrid writer, or a cautionary tale.

Getting Your Rights Reverted

When I signed the contract for May Day back in 2004, ebooks were barely a spark in Jeff Bezos’ eye. As such, the rights reversion language in my contract didn’t mention them. That meant that as long as my Murder by Month Mysteries were available to buy—which they would be forever as long as my publisher had a digital copy available—that I couldn’t get the rights back.

When I signed the contract for May Day back in 2004, ebooks were barely a spark in Jeff Bezos’ eye. As such, the rights reversion language in my contract didn’t mention them. That meant that as long as my Murder by Month Mysteries were available to buy—which they would be forever as long as my publisher had a digital copy available—that I couldn’t get the rights back.

When my publisher offered me a contract for the eleventh book in the series, I took a cut in my normal advance in exchange for updating the rights reversion language in my older contracts. Happily, my publisher agreed. The new language gave me back my rights after the books sold fewer than 300 copies a period over two sales periods (a year total).

That gave me my rights back this past June. Moving forward, in future book negotiations with traditional publishers, I’ll make sure to check my rights reversion language. If your book isn’t selling and has been relegated to the dreaded backlist, you want the chance to revive it.

Note from Jane: The SFWA has some helpful advice for those of you seeking rights reversion. Also, the Authors Alliance offers a free guide on the topic.

Starting Your Business

A few years ago, I filed with the Minnesota Secretary of State to create my own LLC. It cost less than $100. I also set up a post office box and a business checking account under that LLC, and I use that name, account, and address on all the paperwork I fill out for my self-publishing distribution and sales accounts. Privacy is mostly an illusion these days, but it seems like common sense to keep my business address and income separate from my personal life and finances.

Editing, Designing, and Distributing Your Backlist

Suddenly, I had my books, ten of them, in PDF form. I’m a writer and an English professor, not a book designer. How to turn these PDFs into books?

Editorial changes. First, I checked the market to see if I wanted to update my books. For example, romances sell fantastic, and romance readers are loyal. Did I want to add more sexy scenes? In the end, I decided to merely proofread all the books, eliminating scenes and words that younger-me didn’t know were filler, and tightening what remained.

I used Kindle Rocket to check out what was selling and found it easy to use and informative.

I added a series-long secret to book one (a mysterious “open in case of emergency” box that the protagonist finds but holds off on opening). It gets opened in book ten. My goal was to increase series read-through.

Cover design. Once I decided on the market I was writing to—comic caper mysteries—and researched what those readers expect in a cover (Kindle Rocket was good for this, too), I hired a cover designer named Steven Novak. He did great work at a reasonable price.

Interior design. I’d heard that Vellum, a Mac-specific formatting software, was the only way to go, so I bought a Mac, and I bought Vellum. It lived up to the hype, making it incredibly easy to format paperback as well as ebooks across platforms. It also allows intelligent links, so when you list other books in the series in your front or back matter, your reader can click on them and be brought to their preferred bookstore.

A golden tip I received from a successful romance writer: the line after “The End” is the most important real estate in your book. If your reader has read that far, they’re going to want to buy the next book immediately, so format your book so there is only an ornamental break after the end of one book and before the buy link/teaser for the next book.

Distributors. I set up publishing accounts with IngramSpark (paperbacks for libraries and bookstores), Kindle Direct Publishing (ebooks and paperbacks for Amazon), iBooks (this one took over a month to set up because of loops on their end), Nook, and Kobo.

I had a choice between going with KU (Kindle Unlimited) for my ebooks, or going wide (Kindle, iBooks, Nook, Kobo, etc). I chose KU because, several years ago, I saw a dramatic benefit to that path. That hasn’t been my experience this time, though, and I regret not going wide with my mysteries. I’m locked into a 90-day contract with KU and will publish wide after that.

Affiliate accounts. Next, I created affiliate accounts with iBooks and Amazon. What that means is that if someone finishes reading May Day, for example, and clicks on my affiliate-coded link to buy June Bug, I get a percentage of anything they spend in the Amazon store within the next 24 hours. It doesn’t cost them anything, and I am not told what any specific person bought; I just get a check. I made $27.66 last month. Not enough to retire on, but it’s free money.

ISBNs. I went to Bowker and bought 100 ISBNs. Because there are ten books in my series, I matched up ISBNs with series number. So, May Day as the first book has a print and ebook ISBN that end in 1, June Bug as the second book has a print and an ebook ISBN that end in 2, etc. This has saved me time and stress in quickly proofing to make sure I’m using the correct ISBN.

I didn’t buy bar codes for my paperbacks from Bowker at $25 a pop. Instead, I used Bookow’s free generator and donated to their business.

Book description. I rewrote my book description so it was zingier and shorter.

Administration. I created a master document for all ten books. Each page in the document is devoted to a single book: its updated title, subtitle, page count in print (Vellum makes this easy to generate), description, blurbs, and ebook and print ISBNs. I estimate having this all on one document has saved me at least twenty hours this past month.

I also started using Genius Links. There are a lot of benefits, but the biggest is that if I need to update a URL—say Kobo’s version of May Day moves—I can change the URL a single time in Genius Links, and it’ll update the May Day link in the back of all my books.

Marketing Your Backlist

Uff da. When I started this indie pubbing process, the thought of marketing gave me huge hives. I’ve since acquired a mountain of information. Now, the thought of marketing only gives me small hives. Here’s what I’ve learned.

Reviews. If you’ve really overhauled your books, you’ll need new reviews. I recommend BookFunnel for sending out Advance Review Copies (ARCs) as well as building a newsletter list.

Email newsletters. The romance community—which I am not currently a part of but have found to be a wise and generous group—is genius at this. I have a friend who is a full-time, successful indie writer who has over 16,000 newsletter subscribers. That’s a whole slew of people who can’t wait to hear about her next book. Authors often set up newsletter swaps. That is: readers love to hear about new books from authors they respect, and so why not cross-promote?

Reader magnets. This traditionally means, make your first book low-priced (99 cebts) or free to entice new readers to check out your series. I tried making May Day 99 cents and running promotions on it, but I didn’t see a lot of downloads. What I plan to do with May Day is raise it to $2.99 but have it be a free download for anyone who signs up for my newsletter. If you do price one book low, or run sales, here is a helpful list of sites to help you spread the word. I found some of them to be repetitive (same company, different fronts), but it was a good starting point. (Note from Jane: Here is another good resource list of promo sites.)

BookBub Feature Deal. These are hard to get but the Holy Grail of book marketing. I wasn’t able to land one for May Day, but my indie-pubbed magical realism novel, The Catalain Book of Secrets , was selected for a 7/21/18 BookBub Feature Deal. The week leading up to the BookBub, I ad-stacked, running Amazon and Facebook ads. On the day the BookBub ran:

Catalain reached #48 in all of the Amazon paid books, #1 in magical realism, #1 in alchemy, and #2 in sagas.

It sold 2106 copies in Amazon, 376 in iBooks, 337 in Nook, and 168 in Kobo. The sales remained elevated the next day.

Facebook ads. I mentioned above that I ran Facebook ads, which many successful writers do. To create a Facebook ad, you craft your ad image (Canva lets you do it for free), create your ad text (make it short, sweet, and full of the feels), select your audience (successful writers in the genre you write in), then select your budget (I cap my total ad spend at $10 a day). Then, submit the ads for review; if Facebook approves them, they’ll start running immediately. You’ll be charged every time someone clicks on your ad until your daily budget is exhausted. I’m getting better at making Facebook ads, mostly because I use AdEspresso (the Facebook ad manager page is incomprehensible to me). AdEspresso allows me to test which variables (image, text, audience) are working and which aren’t. I set a personal threshold of thirty cents per click for each ad; if it costs more than that for someone to click on my ad and be brought to my Facebook page, it’s not worth it to me.

For a more in-depth look at Facebook and Amazon ads, I’ve heard wonderful things about Mark Dawson’s Ads for Authors course.

I found this free Amazon ads course to be helpful. And personally, I prefer Amazon ads to Facebook ads because I can see whether someone bought my book based on the Amazon ad. It feels less like I’m throwing money in a fire that way.

Traditional marketing. Some of the common marketing methods work here, too, like setting up an online book launch (I didn’t have the energy), setting up signings, and/or arranging a blog tour to spread the word (I have one coming up).

Managing Yourself

Get a budget and stick to it. (I should do this one.)

I’m naturally gifted in this area, but here’s the thing: becoming your own publisher, if you do it right, is a financial and emotional investment. It’s intimidating. Find a good support group, preferably people who know more than you do about indie pubbing.

Stay dynamic. For example, I repackaged my Murder by Month Mysteries as the Mira James Mysteries: Hot and Hilarious. When they didn’t sell as well as I would have liked, I swapped out Hot and Hilarious for Humor and Hijinks. The sales immediately shot up. Being your own publisher means you can be more responsive. This is a good thing.

Finally, do everything you can, and then surrender. It’ll work itself out. I bet I tell myself that ten times a day, and every time, it’s true.

Write on!

August 1, 2018

The Rewards and Challenges of Self-Publishing Children’s Books: Q&A with Four Authors

Today’s guest post is a Q&A by Sangeeta Mehta (@sangeeta_editor), a former acquiring editor of children’s books at Little, Brown and Simon & Schuster, who runs her own editorial services company.

As the traditional book publishing landscape becomes increasingly complex and competitive, more writers are considering independent paths. But given their audience, children’s book authors who self-publish face very different challenges from those who write for adults, especially in terms of design, production, and promotion.

Back in 2014, I asked literary agents Kevan Lyon and Kate McKean if children’s book authors should self-publish. In light of the many changes in book publishing since then, I thought I would continue the conversation, this time by speaking directly with writers who have published both traditionally and independently. Separately, I interviewed Zetta Elliott, who has released several books under her own imprint, including picture books; Brent Hartinger, who self-published a young adult series and a new adult series; Cheryl Klein, the author of a self-published a work of nonfiction; and Stephen Mooser, who released a middle grade book on his own.

As with all of my interviews, none of the participants were aware of the others’ identity until after they submitted their answers to my questions. Here they are, in alphabetical order by author name.

What prompted your decision to self-publish? For example, were you looking to jump-start your writing career? Share a specific idea or message? Experiment outside of your usual genre?

Zetta Elliott: Rejection! I never would have self-published if the publishing industry had shown interest in my work. My first traditionally published book with Lee & Low (Bird, 2008) won a number of awards, but I couldn’t get an agent or interest editors in my twenty other manuscripts. I’m a Black feminist; I’m a scholar and educator; I’ve worked with kids for thirty years. I write realistic fiction but also historical fantasy—time travel and ghost stories to connect the past to the present. African Americans make up 13% of the population but we’re only 3% of kid lit creators in the US. Last year, according to the CCBC, less than a third of kids’ books about Black people were by Black people. Most of the writers I know who self-publish are people of color who have been systematically excluded from the traditional publishing community.

Zetta Elliott: Rejection! I never would have self-published if the publishing industry had shown interest in my work. My first traditionally published book with Lee & Low (Bird, 2008) won a number of awards, but I couldn’t get an agent or interest editors in my twenty other manuscripts. I’m a Black feminist; I’m a scholar and educator; I’ve worked with kids for thirty years. I write realistic fiction but also historical fantasy—time travel and ghost stories to connect the past to the present. African Americans make up 13% of the population but we’re only 3% of kid lit creators in the US. Last year, according to the CCBC, less than a third of kids’ books about Black people were by Black people. Most of the writers I know who self-publish are people of color who have been systematically excluded from the traditional publishing community.

Brent Hartinger: It was as simple as the fact that my publisher at the time wasn’t putting out ebook editions of my earlier books. I was getting a lot of interest from readers, so I finally asked my publisher for all the rights back.

I knew that my book Geography Club (HarperCollins, 2003), the first in the Russel Middlebrook series, was about to be adapted as a small indie film. I decided to take advantage of the publicity and continue the book series on my own, and also market it and package it as a series, which was incredibly satisfying, because my publisher had always bizarrely refused to do that. A year later, after finishing that first series, I aged the characters a bit and started a second series, featuring these formerly teen characters as twentysomethings. My YA characters became New Adult.

All these books did extremely well. Each book made at least as much money as any of my traditionally published books—and probably a lot more. Then again, back then self-publishing was so new it was hard not to make money.

Cheryl Klein: I’m a little different from the other contributors because I am an editor within traditional children’s publishing, and hence I was very familiar with the entire publishing process from the beginning. In 2005, I started a blog that often touched upon writing for children and young adults, and later began posting some of my talks for writers on my nascent website. A few years later, I decided I wanted to put together a collection of this material, but I wasn’t sure anyone would want to publish a miscellany that had first appeared online.

Then I heard about Kickstarter—still in its infancy at the time—which gave me the opportunity to gauge support and raise funds for my first printing. My project got a great response, thanks to the audience I’d built, so that made me confident enough to move forward. And while I usually work with book designers and production and manufacturing people on titles I edit in-house, I was excited about the opportunity to put a whole book together myself. I released the book in April 2011 under the title Second Sight: An Editor’s Talks on Writing, Revising, and Publishing Books for Children and Young Adults.

Stephen Mooser: After traditionally publishing 60 books over more than three decades I had trouble selling my middle grade book, Class Clown Academy, despite the best efforts of three agents. The book was not unlike Louis Sachar’s Sideways Stories from Wayside School, and the one of the agents who tried to sell it said when he had been an acquiring editor he had been looking for such a book. In the end, however, we were not able to place it with a traditional publishing house. I loved the book, loved the characters, thought it was very funny, and thought it deserved a chance to reach an audience. From my experience at the SCBWI I was aware of the obstacles, knew that I had to produce a quality book, and then had to find a way to sell it. All this, I realized, would also require time and money.

Did you hire anyone to help you create or sell your book, such as an illustrator, a designer, a developmental editor or copyeditor, or a publicist?

Zetta Elliott: I hire illustrators on sites like Upwork; that’s also where I found my designer. I use CreateSpace and they provide free downloadable templates, so I have done some text-only books myself. But for picture books, I definitely collaborate and hire artists to do cover art as well. I edit my own work and have a few readers who also provide feedback.

Brent Hartinger: I’ve hired freelance editors, copyeditors, jacket designers. Now what I do is sort of crowdsourcing all the editing, with a combination of some smart writer/editor friends (where we trade manuscripts), and also lots of beta-readers and proofreaders (who are mostly hardcore fans). But I still hire someone to do my book jackets.

Brent Hartinger: I’ve hired freelance editors, copyeditors, jacket designers. Now what I do is sort of crowdsourcing all the editing, with a combination of some smart writer/editor friends (where we trade manuscripts), and also lots of beta-readers and proofreaders (who are mostly hardcore fans). But I still hire someone to do my book jackets.

If you’re not a professional writer with a lot of professional editor friends, hire (1) an editor, (2) a copy editor, (3) a jacket designer. The self-published market is now extremely competitive, and if your book has any whiff of amateurism, I think you’re sunk.

Cheryl Klein: I did hire a freelance book designer/typesetter, which was very useful, as I doubt the book would ever have gotten done if I had to undertake all that work myself. I felt hubristically proud enough of my own copyediting skills that I didn’t hire a proofreader … and then kicked myself with every typo my readers found in the book. (Not a lot of them! But enough.)

Stephen Mooser: I hired a friend who was a designer and could format the book and prepare it for print-on-demand publication by CreateSpace. She also found an illustrator, a professional, who worked in animation to do the spot art.

Finally, to help with promotion, we hired a web developer to build an online virtual school, Class Clown Academy, in which visitors could play various games and engage in a number of activities, all with a humorous approach. There is a science lab; a library; a cafeteria; a music room where kids can create music on whoopee cushions, record their compositions and then send them to their friends. There is also a Class Clown theater where you can watch a film, “Farts and You,” created by my son-in-law, who writes for children’s television. He patched together old educational film clips into a very funny movie.

How did you promote your book? What were some of the pros and cons of your promotional efforts?

Zetta Elliott: I’ve never hired a publicist and find word of mouth can work just as well. One of my self-published picture books, Benny Doesn’t Like to Be Hugged, got a starred review from School Library Journal and was subsequently selected as a first-grade fiction title for the Scripps National Spelling Bee. But not all review outlets accept self-published books, or only after charging exorbitant fees. I submit to the inclusive indie column at Booklist and they’ve reviewed three of my titles. I send out review copies to select bloggers, librarians, and educators, and then use social media to spread positive reviews. I also give talks on college campuses and at conferences; I was a professor for almost ten years and still have academic colleagues who assign my books and essays. I find I’m better at discussing racial disparities in publishing than I am just talking about my books. If I give a compelling talk about issues in kid lit, I find people are naturally drawn to my books.

Brent Hartinger: At first, I tried to launch the book exactly like a traditional launch: I sent the book and a press kit to all the industry review outlets, and also all the mainstream media. I honestly think that was a mistake. They don’t have time to vet all the traditionally published books being produced, much the less the deluge of self-published ones. I thought my name would help, but it didn’t. I chalk that up to industry bias against self-publishing.

What worked? My existing fan base was passionate, and it helps that I directly engage with them on social media.

I’m not a fan of book trailers, which I don’t think anyone watches except the author’s friends, but for one book, I did partner with a musician-friend to write a song based on the book, then I partnered with a filmmaking friend to shoot a music video. For another book, I wrote and sang a song myself, and had my filmmaking friend put together a short film with clips from the movie.

The music video cost me $1700, and the second one cost me $500, and I know they paid for themselves, and more, because I saw the resulting sales figures.

Cheryl Klein: I sought reviews from book bloggers and relevant media for children’s and YA writers (the Horn Book, the SCBWI Bulletin). I also appeared at multiple writers’ conferences and arranged to sell the books there, and of course I talked about it on social media.

Stephen Mooser: Selling the book was harder than I ever imagined. I still don’t regret the expense, but today when people tell me they are going to self-publish, the first thing I ask is “Do you realize it is not enough to post your book on Amazon? There are millions of books already there. How do you plan to drive people to your book and then convince them to buy it?”

Stephen Mooser: Selling the book was harder than I ever imagined. I still don’t regret the expense, but today when people tell me they are going to self-publish, the first thing I ask is “Do you realize it is not enough to post your book on Amazon? There are millions of books already there. How do you plan to drive people to your book and then convince them to buy it?”

I did promote the book on social media. We spent a little money on some banner ads. I also considered trying to organize a Class Clown Association and then hold a conference in order to grab attention, but, in the end, I didn’t care to devote my time to something that time consuming just to sell a few more copies of the book.

How and where do you distribute and sell your book?

Zetta Elliott: I have two books with Skyscape, Amazon Publishing’s teen imprint (A Wish After Midnight and Ship of Souls) and those titles are regularly put on promotion in the US and elsewhere. I don’t particularly enjoy vending but it’s sometimes necessary at events since many bookstores refuse to stock indie titles. I just did a university event and the organizer said the local bookseller wouldn’t even return her calls! The majority of my sales come from Amazon, though libraries generally purchase through distributors like Ingram or Baker & Taylor.

Brent Hartinger: These days, I upload ebooks to Amazon, and have Smashwords (which is a self-publishing distributor) do all the other platforms. I used to do all the outlets individually, but it was too much work, and I hated doing all the updating. I also do a print edition through CreateSpace. Most self-publishers say they don’t sell print copies of their books, but that’s been less true for me. I actually end up in libraries, unlike most self-publishers, probably due to my career as a traditionally published author. My books continue to sell steadily. Every time I release a new book, my backlist sales go way up.

Cheryl Klein: The first printing was available through a distributor’s website, Amazon (their Advantage program), and my events. Later printings were only available through Advantage and events. To some extent I regret not fulfilling orders through my own website, where I could have collected customer info and built out my email list. But setting that structure up and maintaining it was more than I knew how to do in 2011, and I did not anticipate writing or publishing future books of my own at the time, so an email list felt like less of a necessity than it is for marketing now.

Cheryl Klein: The first printing was available through a distributor’s website, Amazon (their Advantage program), and my events. Later printings were only available through Advantage and events. To some extent I regret not fulfilling orders through my own website, where I could have collected customer info and built out my email list. But setting that structure up and maintaining it was more than I knew how to do in 2011, and I did not anticipate writing or publishing future books of my own at the time, so an email list felt like less of a necessity than it is for marketing now.

Second Sight is no longer available for sale. After its third printing, I decided I wanted to revise the text, and I sold the new version to W. W. Norton, which published it as The Magic Words. As part of that deal, Second Sight went out of print in 2016—but I didn’t mind that, since The Magic Words is a better book.

Stephen Mooser: I sell on Amazon and CreateSpace as print-on-demand in paperback. I have sold a few copies at conferences, but not that many.

So far, it looks as though adult genre fiction, particularly romance, has fared best in the self-publishing landscape, though there are exceptions (as shown by John and Jennifer Churchman , Beth Reekles , and Amanda Hocking , among others). Do you think we’ll see more such success stories among self-published children’s books down the road, or does this depend entirely on the targeted audience, format, and publishing plan?

Zetta Elliott: It depends on how you define “success.” I’m an advocate for community-based publishing that puts people over profits. But if you’re talking about sales, then I do think we’ll see more success stories as more marginalized writers realize that self-publishing is their only option. Most kid lit awards accept indie submissions; if a self-published book wins a major award, that might also change perceptions.

Brent Hartinger: There will always been exceptions, but yeah, self-publishing has become almost exclusively romance, with a bit of paranormal too, and a few other extremely popular genres.

Self-publishing other genres like historical fiction? Literary fiction? Quiet realistic fiction? Fuhgeddaboudit! Especially in children’s books. I’m sure there are exceptions, but I suspect they’re either niche books, or the exceptions that prove that rule.

I’ve always divided books into two different categories: “dessert” books (which tend to be light and frothy, but are always immediately desirable, and you want it no matter what anyone else says) and “broccoli” books (which are more difficult or more challenging, maybe literary fiction or award-winners, books you’re “supposed” to read, because they’re “good for you”).

You can still successfully self-publish a “dessert” book, but I think it’s much more difficult to self-publish a “broccoli” book. For the most part, broccoli books need the imprimatur of a publisher. That’s literally the function of publishers, to say that the unusual or different book you’re reading has been vetted by lots of smart people who say, “Yes, this is one of the best books written this year!”

By the way, I’m not making a value judgment. I love broccoli!

Cheryl Klein: I’m sure we’ll see some individual successes, but in the main, I think self-published children’s books are going to continue to have a hard time, honestly. In print, they’re expensive to produce in a small print run, and hard to distribute without a lot of preexisting infrastructure. Most parents are disinclined to read ebooks to their kids, and the kids themselves usually don’t (or even can’t) go looking for new ebooks/authors online the way that adult genre readers do. They’re much more inclined toward discovering books in print, as are most of their gatekeepers. If someone new does break out, my guess is that it would be either a graphic novelist or a YA writer.

Stephen Mooser: For most people, self-publishing will remain a challenge primarily because of the marketing. For people who have a large social media following (meaning hundreds of thousands of followers or more) or those with a book targeted to a specific, reachable, audience, there’s a greater chance for success. For instance I’ve put together a picture book, filled with photos from the internet, called Kittengarten, where kittens learn how to manipulate the humans who share their home. I have a dummy, but it will require some permissions and time before I might choose to self-publish. However, I believe there is a market for cute kitten books, and between the internet and cat associations and clubs I could reach my intended audience.

Again, when people write for advice on self-publishing I begin by asking how they plan to sell. If someone is writing a book on nurses and they have access to a list of nurses nationwide then I’d say give it a try. If they are doing a picture book about the joys of springtime I’d warn them away.

Years ago, there was a stigma associated with self-publishing. Would you say that it still exists today? What can we in the book publishing community do to minimize it?

Zetta Elliott: The quality of self-published books is improving but the stigma remains—too many booksellers, libraries, and review outlets hold blanket policies that keep writers of color locked out of the kid lit community. To eradicate the stigma, members of the publishing community need to acknowledge that there is far more talent than opportunity. The industry is dominated by one group (straight, White, cisgender women without disabilities) and those professionals have proven they’re unable or unwilling to share power. Until they do, many marginalized writers will have no choice but to self-publish. A commitment to diversity means accepting that there are multiple ways of telling stories and producing books.

Brent Hartinger: Well, some of that stigma is there for a reason. There’s a huge amount of crap in self-publishing. Personally, I think there’s a huge amount of crap in traditional publishing too, but there’s definitely less crap. Editors and publishing houses make a big difference in terms of overall quality.

In traditional publishing, you “prove” yourself by writing a book that makes it through the gauntlet of agents and editors. Readers weigh in too, but not until the end. In self-publishing, you’re “published,” but you still haven’t proven yourself. Readers do all the vetting.

Traditional publishing and self-publishing seem to me to perform very different functions in our media landscape. At its best, the fundamental function of traditional publishing is to celebrate quality and break new cultural ground. At its best, the fundamental function of self-publishing is to celebrate and empower fandoms and niches, and also break ground, but in smaller or less “serious” ways (like Fifty Shades of Grey normalizing S&M). Although I will say that sometimes self-publishing can champion ideas or readerships that traditional publishing is ignoring through sheer bias or bigotry.

Cheryl Klein: I think it is much more widely accepted as a viable publishing choice.

Stephen Mooser: There still is a stigma, but not nearly to the degree there was five years ago. The SCBWI Spark Award for independently published books gets many excellent entries that are as good (and sometimes better) than anything published by traditional publishers. Naturally, there’s also a lot of sub-standard entries, but quality seems to be improving.

As a community we can help the independent book community’s reputation improve by continuing to educate the creators of those books, by raising the awareness of the good books through awards like The Spark, by publishing helpful articles in the SCBWI Bulletin, and by including workshops and panels on the subject at conferences.

If you were to self-publish again, what would you do differently? Do you have any advice for children’s book authors planning to self-publish in today’s market?

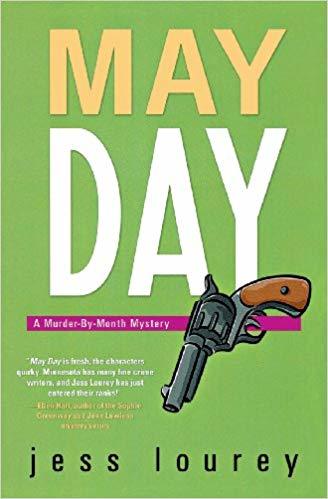

Zetta Elliott: I’ve self-published over twenty books and my most recent title (The Return) came out last month; it’s my first hybrid graphic novel and my most expensive book at $18. It’s a bridge project for me; the next book in the series will be a traditional graphic novel. I think it’s important to be clear on your goals—are you writing to make money? Do you want to win awards or wind up on the New York Times bestseller list? That’s not why I write, so I’m not discouraged when a book I’ve self-published sells a couple thousand or a couple hundred copies.

When I self-publish, I’m showing what types of stories are getting rejected by traditional publishers. I’m affirming the value of the stories that matter to me and my community. Books are commodities but stories have more than commercial value in many cultures. When the traditional publishing industry says, “Your stories don’t matter to us,” it’s an act of resistance to walk away and make the book yourself. It’s also therapeutic and empowering! You don’t know what you can create on your own until you give yourself permission to experiment. That’s why I self-publish.

Brent Hartinger: I’d keep it to YA, not middle grade, and only very popular genres and/or sub-niches. I’d be very wary about self-publishing middle grade or chapter books unless you have some kind of built-in, underserved audience.

Honestly, I’m reluctant to recommend self-publishing for anyone now, except those very niche books. There’s a real renaissance in children’s publishing right now. If you have a book you think is special, I’d absolutely try to traditionally publish it first. Lately, the money can be really great too.

As for me, if I do self-publish new books, they’ll be part of my existing series. The market is very, very different now. The Gold Rush is definitely over. There is now an absolute deluge of content, and the market has become extremely competitive. Your idea needs to be really, really marketable, or your book needs to be really, really good, and preferably both.

I actually think it’s easier to land a traditional deal right now, especially in children’s books, than it is to successfully self-publish. A lot easier, actually.

Cheryl Klein: I was happy with my experience, but I’ll offer three pieces of advice.

(1) Think carefully about what you want to get out of being published, and whether self-publishing is the best way to fulfill those goals. If you just want a book with your name on it—which is a totally valid desire—self-publishing can fulfill that. If you want to reach thousands of child readers across the United States, you may need the support of a traditional publisher.

(2) Make a marketing plan before you even create the book, and start laying the groundwork for your marketing early on, while you’re still writing. A good rule of thumb is to spend 5-10% of your writing time on establishing a platform, connections, and community, and spend the rest on your writing.

(3) Life is short, and dealing with all of the small headaches of self-publishing can take up a lot of time. Don’t self-publish unless you’re nearly as excited to work on publishing the book as you are to work on writing it. If you’re not that excited, then the publishing can easily become just another thing that takes you away from the writing.

Stephen Mooser: I would give much more thought to marketing before investing in self-publishing. And I might add it can be a long and sometimes expensive journey, but if you believe in your book and you are willing to spend the money to do a book that looks as professional as anything put out by Simon & Schuster or HarperCollins, then give it a try so you don’t have any regrets down the line. But keep in mind if you don’t have a solid marketing plan you will probably not succeed.

Zetta Elliott, PhD, (@zettaelliott) is a Black feminist writer of poetry, plays, essays, novels, and stories for children, many of which she has self-published. Visit her website.

Brent Hartinger (@brenthartinger) wrote the YA classic Geography Club (2003), which was a Lambda Award finalist, was adapted as a 2013 feature film, and is now being developed as a television series. He’s since published twelve more novels and had eight of his screenplays optioned by producers. Visit his website.

Cheryl B. Klein (@chavelaque) is the editorial director at Lee & Low Books and the author of The Magic Words: Writing Great Books for Children and Young Adults as well as two forthcoming picture books. Visit her website.

Stephen Mooser (@stephenmooser), co-founder and president of the SCBWI, is the author of over 60 books for young readers, including his self-published middle grade title CLASS CLOWN ACADEMY. Visit his website.

July 31, 2018

The 13 Most Common Self-Publishing Mistakes to Avoid

Today’s guest post is by Lauren Bailey from Kirkus Reviews.

For every new venture, there is a learning curve. When it comes to self-publishing your book, however, that curve can be steep. After spending all that time and effort writing (and maybe even illustrating) your book, you want to make sure you do everything right—or at least as right as you can.

The shiny side of this coin is that a lot of authors have already made their mistakes, and many of them have been generous in sharing both their trials and successes. In other words, you are now in the very enviable position of being able to learn from other people’s experiences so that your own experience is positive.

1. Skimping on cover design

When it comes to book sales, first impressions aren’t just important—they are everything. Many authors opt to save money and create their own front covers. Unfortunately, unless you have a background in book publishing and serious design chops, going the DIY route could mean a sales disaster. There are many ways to invest in your book with your own hard-earned cash, but the best possible value for you is to hire an experienced book designer with a good reputation; check out design firms like The Book Designers, The Book Makers, and Damonza. This is very much a “get what you pay for” scenario, but a polished, professional, and visually arresting book cover is worth its weight in gold (by which we mean “sales”).

For advice on cover design:

5 Ways a Book Cover Could Hurt Sales—and How to Fix It

The Importance of Your Book Cover: Achieving the Right Fit

5 Steps to Great Cover Art

2. Not optimizing your book description

Every retailer gives you a page describing your book to potential readers. It’s another case of “make your first impressions count,” because nothing will send your readers running faster than a description that is boring, rambling, or full of self-congratulation. The best way to train yourself to write a good book description is to read as many of them in your book’s genre as you can; you’ll soon notice a common structure to the writing and what kind of plot points are highlighted. Plan to spend some time reading book jackets at your local library or bookstore or cozy up to your computer and cruise your favorite online book retailer.

For more advice on writing book descriptions:

How to Improve Your Amazon Book Description and Metadata

How Writers Can Optimize Their Book’s Description on Amazon

3. Insufficient research and market analysis

Forbes has suggested that between 600,000 and 1,000,000 books are self-published every year. That’s a lot. In order to get the maximum leverage for selling your book, you’ll want to figure out which books are selling best (and more importantly, why), what readers want to read right now, who your key demographic is and how to reach them, and if you have any competition.

For advice on conducting reader and market research:

How Authors Can Find Their Ideal Reading Audience

How to Find and Research Influencers to Help Promote Your Book

4. Slacking on (or entirely skipping) the editing process

Editors are hyperliterate—they’re adept at spotting typos, spelling mistakes, and grammar errors a mile away. They’re also going to be merciless about inconsistencies, plot holes, poor structure, clichés. Before you hire one, first edit the book yourself and try to get it as “clean” as possible. Then make sure you understand the different types of editing available: development/content editing, line editing and copyediting, and proofreading. It’s nearly impossible for one editor to accomplish all levels of editing in one pass, and manuscripts require different types of editing.

For advice and resources on editing—which is a complex topic!

Should You Hire a Professional Editor?

When You Shouldn’t Hire and Pay for a Professional Editor

What Is a Developmental Editor and What Can You Expect?

How to Find an Editor as a Self-Published Author

6 Ways to Vet Freelance Editors

5 Ways to Find the Right Freelance Book Editor

5. Bad timing

You’d be surprised at how many people try to publish their books at the wrong time. Books about elections after the Presidential election. Christmas books released on Christmas Day. Beachy reads in November. Look at your calendar and do a little digging online to find out when you should release your book. Beyond the obvious holidays and seasons, try to find a timely connection that might help position your book as particularly relevant. This especially comes in handy for pitching it to news media or planning a book tour: perhaps the release of your historical pirate novel could coincide with an upcoming anniversary celebration of a famous shipwreck discovery or your travelogue about painting across Europe could be ready to launch in time for Henri Matisse’s 150th birthday.

Learn more about the best timing for book launches.

6. Not selecting a specific release date and sticking to it

A big part of marketing is setting up your audience’s expectations. And nothing will destroy that relationship faster than becoming unreliable. Make sure you’re being realistic about your publishing date, and don’t let your readers down.

Learn about pre-order strategies to increase your sales.

7. Incorrectly formatting your book

Every bookseller has different technical requirements that need to be strictly observed. Check their guidelines to find out which file type they prefer you upload—the usual suspects include a Microsoft Word document, an Adobe PDF file, or a MOBI or EPUB file—and if they accept more than one, make sure you choose the one best suited to your manuscript. (Whether your book contains graphics is a big consideration here.) Beyond the file type itself, formatting your manuscript cleanly and simply ensures that readers enjoy a seamless experience, so be mindful of fundamentals like paragraph and section breaks and uniform line spacing.

For guidance, read Joel Friedlander’s extensive how-to articles on interior design (and more).

8. No one read your book before you published it

Known as “beta readers,” these nice folks love books enough to read them and give you feedback, letting you know if your book is enjoyable and where it might need some work. Sometimes it’s as simple as asking friends and family members for honest critical feedback, but your best bet is to join a writers’ group. Writing communities are supportive, and the only cost to you for this service is returning the favor. No one likes criticism, but it’s a critical process for authors. Beta readers can be the difference between publishing a bad book (because you can’t always trust your mom or bestie) and a great book.

Note: A great online tool for organizing your beta readers (and maybe finding new ones) is Beta Books.

9. No marketing

If no one knows about your book, no one will buy it. As much as self-published authors dream about being “discovered,” it’s your responsibility to tell as many people about your book as possible—even before it’s published. These days, even traditional publishers are asking their authors to help out with marketing and social media. Engaging your readers and fans during the writing process invites them to be part of the journey, help you spread the word about your book, and buy it when it’s released.

For more advice on book marketing:

Browse the archive of marketing how-to posts on this site.

Take a look at Tim Grahl’s book marketing checklist.

BookBub offers great ideas for book marketing.

Here’s Jane’s roundup of best book marketing advice in 2017.

10. Selling through only one distributor

It may require some extra time on your part, but don’t restrict yourself to selling your book through one channel. It’s important to get your book out there to as many people as possible. Explore options IngramSpark and CreateSpace, which give you access to different types of retail outlets. And don’t forget the library market, which you can reach through ebook distributors like Smashwords and Draft2Digital. For in-depth advice on book distribution, here is Jane’s 101 article.

11. Charging the wrong price

Price your book too high, and no one will buy it. Price it too low, and you may increase your sales—but you won’t be selling your book at what it’s worth. Worse, readers may assume that because your book is cheap, it isn’t good. Research what other books in your genre and at your page count are selling for. And remember that while promotional discounts can be a valuable bump in your sales, customers are savvy enough to wait until the price drops another time.

For more advice:

Written Word Media regularly discusses ebook pricing trends.

IngramSpark offers advice that pertains to print pricing.

12. Not using your personal network

Your friends and family love you, and hopefully they want you to succeed. Don’t be afraid to ask them to mention your book on their social media channels. Mostly, remind them that the greatest support they can give is to buy your book for themselves—and perhaps as gifts for other people.

For more advice:

Go Local: Marketing Books to Targeted Communities

A Book Launch Plan for First-Time Authors Without an Online Presence

13. Quitting if your first book tanks

At some point in your life, someone probably intoned that annoying “If at first you don’t succeed, try try again” proverb. The truth is that when it comes to writing, persistence really is key. Every project and every book is an experience that will help you get to the next level. Sometimes it’s just a matter of timing. Sometimes it’s just a matter of luck. And sometimes, our first effort isn’t always our best. The trick is to keep going.

Remember that when it comes to publishing your book, you don’t want to rush through the process. It’s easier to fix mistakes before your book is out in the world, and only good things can come of taking your time and doing it right the first time.

You’ve already done the hardest part of the process—writing. This is a huge feat alone, and worthy of celebrating. Remember that not only will your next book be better but you will have all the experiences you’ve learned. You’ll already have a fan base to help and encourage you. Better still, every new book you publish will boost the sales of your older books, as readers want to explore other work you’ve written. And that is where success begins.

Your turn: What advice would you give to authors who are self-publishing for the first time? What mistakes have you learned from?

July 30, 2018

5 Ways to Sell More Books for the Holidays

Photo credit: kevin dooley on VisualHunt / CC BY

Today’s guest post is by Penny Sansevieri (@bookgal) and is excerpted from 50 Ways to Sell a Sleigh-Load of Books.

I used to laugh at the “Christmas-in-July” ads until I promoted my first holiday-related book. We actually started the promotion in July, and July turned out to be the perfect time. Why? Maybe no one buys or thinks about December in July, but the holiday buying season is tough. To make any kind of headway, you must start early. When those “Christmas-in-July” ads start to hit radio and TV, social media, and your inbox, consumers— those who like to shop early—start gathering ideas for their shopping lists.

When is it too late to start thinking about storming the holiday market? November is definitely much too late. October is iffy. If you’re staring September in the face and haven’t done a lick of marketing towards holiday sales, now might be your last chance.

Better to start early—mid-to-late summer is ideal. Here are several ideas to get you started.

1. Do Holiday-Themed Hashtag Research

The holidays are full of excitement and enthusiasm, and hashtags play right into that added fervor. Hashtags exist for every traditional activity or element of the season you can imagine. Your goal is to figure out which hashtags get the most attention, or what’s trending. Hashtags might be somewhat evergreen when you add the current year. A very basic example is #ChristmasCountdown2018.

Know your competition, and learn from authors in your genre who are a couple of rungs up the ladder from you. Success leaves clues. And yes, you can find out what your competition did right last season. It takes some scrolling, but the data is there.

Here are some evergreen hashtags that have stood the test of time in recent years. Remember to insert the current year to make your hashtags timely:

#ChristmasCountDown

#ChristmasInJuly

#ChristmasPresents

#ChristmasTraditions

#ChristmasTree

#ChristmasFail

#ChristmasDecorating

#Christmas

#ChristmasMood

#ChristmasReading

#HolidayRomance

#ChristmasBreak

#TisTheSeason

#SeasonsGreetings

#ChristmasShopping

#HolidaySavings

#BlackFriday

#CyberMonday

#ChristmasGiftIdeas

#StockingStuffer

#WishList

While a certain hashtag might be trending, or even evergreen, if the hashtag goes against your branding or doesn’t fit your personality, look for a different hashtag that makes more sense. Hashtags enhance searchability and relevance, but they’re also an extension of your personality, so be thoughtful.

2. Coordinate with Other Authors for Social Media Promotions

Now is a perfect time to join forces and coordinate holiday sales efforts with authors in a similar genre. What if you did a bundled book together? What if you and four or five other authors gather your best books and offer them as a special holiday bundle? If bundling is not an option, organize your marketing efforts so you each share the other’s stuff on your websites and in social media posts.

Let the authors know what you’re planning, such as a string of promotions or BOGOs around the holidays, and find out what they’re doing. If the other authors have promos planned, they might be interested in combining forces by sharing your stuff if you share theirs. Keep in mind that this reciprocity only works with authors in similar genres. You’re each pulling in your own market, which is your core readership. Don’t try to sell a puppy to a cat person.

3. Do Your Own 12 Days of Christmas Giveaways

Consider whether you can organize your giveaway and promotion ideas into a 12-day series to play into the “12 Days of Christmas” theme.

If your book has an “easy to shop for” reader audience, you can invest in 12 small gifts to encourage readers to engage with your brand. Think stocking stuffers. For example, women’s fiction, which is broad and relatively easy to shop for, a 12-day theme could include a small box of chocolates, a beaded bracelet, or a Dead Sea mud mask.

You can offer one of the stocking stuffers for giveaway each day so your fans and followers engage with your promotions. Maybe to earn an entry, a readers emails you a receipt for one of your books they’ve purchased. Day 2 they share a link to your book on Amazon on their Facebook account, and day 3 they submit a screenshot of their review of your book on Goodreads.

Focus on 12 valuable things your readers and followers can do, match those with 12 inspiring rewards, and you’ve got a 12 Days of Christmas promotion.

4. Make Custom Tree Ornaments for Superfans or Giveaways

Imagine being on someone’s tree every year—what an amazing honor! Consider making keepsakes to represent your books. Reserve these keepsakes for your superfans, use them as giveaways, or a little of both. Maybe superfans receive one kind of keepsake, and everyone else can vie for another style in a giveaway.

Etsy is a fantastic place to find small artisans doing amazing things. Dig around and you might be inspired with even more ideas for and beyond.

5. Create a Gift Guide

You’ve probably seen how retailers offer “employee favorites,” and highlight a certain brand or product to call attention to them. Many stores now also offer “gifting guides” for everyone on your shopping list. Why not do the same thing? Create a gift guide for your readers’ best friend, spouse or child—whatever suits your reader market best. Yes, you can recommend your book, but also find things that speak to the consumer’s desire to find that perfect gift. If, for example, your book is sci-fi, create a “for the sci-fi lover in your life” package. Or combine your book with a cool Star Wars poster you saw on Etsy. Some authors create an actual gift basket that readers can give as a unique Christmas gift.

You’ve probably seen how retailers offer “employee favorites,” and highlight a certain brand or product to call attention to them. Many stores now also offer “gifting guides” for everyone on your shopping list. Why not do the same thing? Create a gift guide for your readers’ best friend, spouse or child—whatever suits your reader market best. Yes, you can recommend your book, but also find things that speak to the consumer’s desire to find that perfect gift. If, for example, your book is sci-fi, create a “for the sci-fi lover in your life” package. Or combine your book with a cool Star Wars poster you saw on Etsy. Some authors create an actual gift basket that readers can give as a unique Christmas gift.

If you found this post helpful, check out 50 Ways to Sell a Sleigh-Load of Books by Penny Sansevieri.

July 23, 2018

How to Skillfully Use Subplots in Your Novel

Photo credit: Theen … on Visual hunt / CC BY-NC-SA

Today’s guest post is excerpted from Plots and Plotting by UK author Diana Kimpton.

Subplots help pace your story and keep the tension rising. Unfortunately, the name “subplots” wrongly suggests they are somehow inferior or substandard. It also gives the impression that they are something separate from the main plot—a second story running under the first one and completely disconnected from it. Sometimes I find subplots exactly like that in novels I read—usually the ones that aren’t very good. When the authors realize there’s not enough going on, they stick in a completely irrelevant subplot, about a lost cat or a child’s birthday, that gets in the way of the main story and slows the action.

I prefer to think of story strands rather than subplots as that better explains how they work. The main storyline is your central strand carrying the reader forward toward the final conclusion of the book. Other story strands (or subplots) intertwine with the main one, building it up from a single strand into a fascinating, deeply textured plot that will hold your readers’ interest. If you’ve ever plaited hair, you’ll know that different strands become the top one as you work, and writing an interwoven plot is just like that. Although you have the main storyline running through the whole novel, other story strands will be more important at various stages of the book, and some of the twists and turns in the plot come when you move from one strand to another or when two strands collide. The story strands work together to carry the reader toward the end of the book and some, but not necessarily all, will be resolved at or around the same time as the resolution of the main storyline. Others will be resolved during the progress of the story, but this needs to be done with care or, going back to our hair analogy, you’ll end up with an untidy plait with lots of straggly bits sticking out the sides.

One big advantage in thinking about story strands rather than subplots is that you don’t have to worry whether a strand is big enough to count as a subplot in its own right or is really part of the main story. It won’t make any difference to your writing either way so you can leave that question for people who try to analyze your book after it’s finished. All you need to know is that the strand is there so you can use it to the best possible effect. (Incidentally, the better your book is plotted, the harder it is for analysts to tease apart the various strands of the story.)

How many strands does a book need?

Short stories and children’s picture books work well with just a single storyline. (In writing jargon, they have a basic linear plot.) However, longer novels are more interesting if they have more than one strand and the longer the book, the more strands you can include. My Pony-Mad Princess books are around 7,000 words long and usually have two strands. Usually one is about the ponies and the other is about the royal world, and I always aim to end both strands in the final chapter. For example, the strands in Princess Ellie’s Secret are:

A. Ellie trying to stop her first pony being sold.

B. The problems caused by grumpy Great Aunt Edwina coming to stay at the palace.

(Warning: Spoilers ahead for pony-mad children.)

The plot starts with strand A. Ellie has outgrown her Shetland pony, Shadow, and is horrified when the King declares he must be sold because he has no work to do. She decides that she could drive him instead of riding him so secretly starts training him to pull a carriage. Then, just as everything seems to be going well, the plot twists with the introduction of strand B. Great Aunt Edwina has invited herself to stay at the palace and Ellie’s parents give her the task of entertaining the grumpy old lady. This means Ellie can’t spend any time at the stables.

After a frustrating time with her great aunt, Ellie manages to escape for a while to take Shadow for his first drive (back to strand A). Everything is going well until they turn a corner and come face to face with Great Aunt Edwina, who has gone out for a walk (strands A and B collide and join together). To Ellie’s surprise, Great Aunt Edwina is delighted. She always liked driving when she was a girl and insists that Ellie moves over so she can take the reins. The King is so pleased to find something that makes his difficult aunt happy that he agrees to keep Shadow so she can drive him (strands A and B end together).

Mirrored strands

In the plot I’ve just described, the strand about the outgrown pony is the main storyline while the strand about Great Aunt Edwina is a secondary strand that’s designed to complicate the plot. But you can also achieve a strong plot by making two strands of your story complement or mirror each other.

In my young adult novel, There Must Be Horses, one story strand is about the way Sasha’s troubled background has left her unable to trust other people, and another strand is about a horse whose troubled background has made him unable to trust humans. As these mirrored strands weave together, the girl and the horse heal each other and solve each other’s problems.

Unconnected strands

In another type of plot, the story strands are completely separate at first, and readers don’t see the connection between them until later in the book. For instance, in a disaster story, you might introduce three or four completely separate characters in different situations and move between them, building up their individual story strands until some big event (like an earthquake or a war) brings them together. Similarly, in a thriller, you might create one story strand about a detective and another strand about a girl, both of which seem completely unconnected until the girl is murdered.

When you jump around between strands like this, experienced readers will assume that there will eventually be a link between them so they will be looking for it. You can play along with this by hinting at possibilities and building up some tension about when the link will be revealed.

Although this approach can work well, it can be hard to hold your readers’ attention if you jump between characters so much that they are not sure which one they should be caring about. You can make life easier for them by introducing one character first and only introducing the others when their strands meet. So, in the thriller, you could concentrate on the girl until she’s murdered and then introduce the detective’s story strand. Alternatively, you could concentrate on the detective until the murder and then let him piece together the girl’s story as he investigates the crime.

Weaving strands together

If your story has two or more main strands, it’s sometimes difficult to decide how to weave them together. When I’m faced with this problem, I find it helpful to write a step outline for each strand of the story, putting each step on a separate sticky note and using different colors for each strand. Then I experiment with different ways to join those steps into one coherent plot by moving the pieces of paper around. The result is a single, multi-colored line of sticky notes—much like the plait I talked about earlier.

Staying flexible

The main storyline of your book is the one you would talk about if you were asked to describe your book in one sentence. This is sometimes called the elevator pitch, because it’s what you might say if you got in a lift with a top publisher or agent and had to sell your book to them between floors.

If you work on your plot before you start writing, you may find that one of your story strands resonates with you and starts to take over from that original idea. If that happens, follow your instincts. If you’re sure that you can make the new strand work better than your original main storyline, swap them over. You are only at the plotting stage so it’s easy to do and there’s no major rewriting involved, even if you eventually decide to swap them back.

If you work on your plot before you start writing, you may find that one of your story strands resonates with you and starts to take over from that original idea. If that happens, follow your instincts. If you’re sure that you can make the new strand work better than your original main storyline, swap them over. You are only at the plotting stage so it’s easy to do and there’s no major rewriting involved, even if you eventually decide to swap them back.

If you enjoyed this article, be sure to check out Diana Kimpton’s Plots & Plotting.

July 9, 2018

The First Half of 2018: Traditional Publishers Stand Strong with Nonfiction and Backlist

BookExpo 2018

As one of the editors of the The Hot Sheet, produced in collaboration with journalist Porter Anderson, I regularly read and report on publishing industry developments that affect writers. Here are the stories and trends that stand out so far in 2018.

Traditional Publishers Doing Well—Despite Decline in Ebook Sales

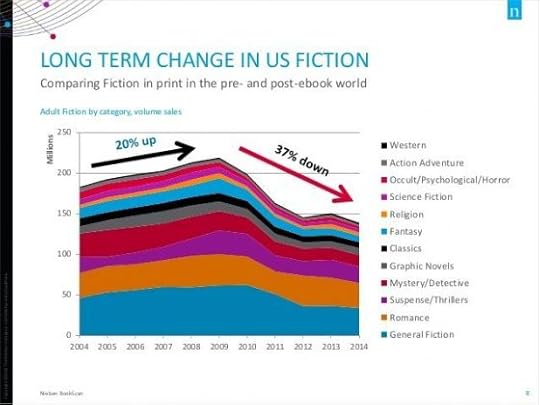

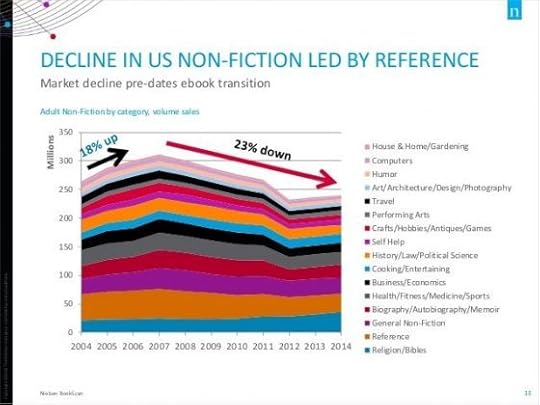

Globally, for the Big Five publishers, print and ebook sales currently stand at 80-20 in favor of print when averaged out across all categories. (Fiction has the highest percentage of ebook sales, with a 50-50 split between print and digital.)

The Big Five CEOs at BookExpo this year publicly commented on how pleased they are with the fairly stable business model that has developed despite pressures of the digital age and online retail. For example, the number of units sold in physical outlets, as a percentage of their overall business, has remained solid. But the CEOs admitted that it will take work to keep it that way in the face of a competitor like Amazon. John Sargent of Macmillan said, “There are some serious issues we will face in the coming years over changing consumer buying behaviors … and the issue of discoverability. … What we need to protect is lots and lots of shelf space in America for people to browse books.”

Side note: Just because ebook sales have been declining for traditional publishers doesn’t mean ebook sales are down for the entire industry. This article from Quartz discusses what is an increasingly confusing issue.

The strongest category this year for traditional publishers: political books

According to reports from NPD BookScan—which tracks traditional publishing sales—the number of political books (in print format) sold following the 2016 election is nearly double the volume following the 2012 election. It’s not that more books are being published; each title is just selling better. Political books are also showing digital growth and are up 22 percent compared to a decline of 5 percent for all ebooks tracked by NPD. The biggest selling title of the year thus far—in any category—is Fire & Fury by Michael Wolff.

The political landscape is also boosting other categories, such as dystopian fiction (where sales have doubled—led by Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale) and prescriptive nonfiction. Personal growth and motivational/inspirational titles (such as The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F— by Mark Manson and You Are a Badass by Jen Sincero) have seen double-digit print sales growth, and the latest era of self-improvement titles has been driven by younger consumers—millennials in particular—in what NPD called “adulting with attitude.”

The weak spot for traditional publishers: fiction and ebooks

Broadly, traditional print book sales continue to grow at about 2 to 3 percent per year, but growth is driven by nonfiction, backlist titles, and children’s/YA. Fiction sales have been flat for several years now, with frontlist fiction down 5 percent due to a lack of big titles. Five years ago, ebooks were at 28 percent market share for traditionally published books; today they are at 20 percent. NPD’s explanation for the drop: people are shifting from e-readers to tablets and phones that offer more distractions, and ebook pricing has gone up, which they call “the biggest barrier to entry.”

Whatever you would like to believe about traditional publishing’s performance, it’s quite easy to find the statistics to support your story. “Print is back!” is the story favored by mainstream media and the publishers themselves, especially when looking at the strength (or “return”) of independent bookstores. However, a frequent talking point is now the frontlist-backlist divide in fiction sales, or how new fiction titles are not selling as strongly as in past years. Simon & Schuster finished 2017 with record profits but admitted to declining sales of “important” authors. CEO Carolyn Reidy of Simon & Schuster commented, to Publishers Marketplace, “We’re talking about these real powerhouses that have fueled the industry for a lot of years. It’s still a challenge to help an established, bestselling author maintain and grow his or her audience.”

The Challenges of Fiction Frontlist May Put Additional Marketing Expectations on New Authors

Once upon a time, it was relatively safe to say that, prior to a book deal, novelists weren’t expected to know much about the marketing process—or to have a platform in place. Novelists would be expected to market and promote their work once a publication date was set, but manuscripts would be sold primarily on their storytelling merits and appeal in the marketplace; the marketing discussions would come later. But that may be changing.

Carly Watters, VP & senior literary agent at P.S. Literary Agency, tweeted in April that because the industry is changing, so are her fiction submission requests. Aside from a synopsis, any author asked for a full manuscript will have to provide a list of five comparable titles from the past five years, a short marketing plan, a description of the next work in progress, and a list of alternate titles for the work being submitted. She added, “This reflects the seriousness authors need to take when launching their career & it starts with you.” If there was any good news for the debut novelist, it was that this request applies only to writers being asked for a full manuscript, not to writers sending initial queries.

This tweet landed right during London Book Fair, where nonfiction deals were riding high and fiction deals weren’t. As discussed above, fiction performance is weak globally, and backlist is driving sales. When NPD BookScan released their first quarterly summary for 2018, adult fiction was down 3 percent.

When I reached out to Watters about her Twitter thread, she illuminated more of the thinking behind her request. First, she said this is more of a “test” of mindset and understanding than anything. “I care about how the author responds to my request, that they engage with it, and that they have some idea about how their book fits in the marketplace.” The marketing plan is the most test-oriented part of the equation; Watters wants to see that writers have given the marketing of their work some thought, even if their points are off the mark or things the publisher would do. “I just want to learn what they know at this stage,” she said. “What I don’t want to see is a short list of things that they ‘will do in the future once they get a deal.’” She’s most interested in what they’re doing now to grow their platform and brand.

Watters says one thing that’s working for her lately is pitching a book with blurbs already in the pitch package. Therefore, she’s interested in knowing if the writer has author-friends who could lend a blurb to help her create the best possible package. She says, “With debut [novelists] I don’t send a marketing plan, but I often try to get them blurbs before submission—even if it’s just my pubbed clients helping each other out.”

I asked other agents active in the industry to see if they or their agencies are looking for more marketing information from querying novelists. Donald Maass, president of Donald Maass Literary Agency, said, “I know that publishers are these days thinking ahead to marketing of fiction, so it’s natural for ideas of comp titles, next work, and so on to pass up the line.” He said his agency works with writers to come up with the information, then added that this process applies mainly to debut fiction, and that after the first book, acquisitions decisions turn more on prior sales than anything. He cautioned, “Marketing bullet points reassure bookstore accounts but have little influence on book consumers. For fiction consumers, the most influential factors are in-store display, word of mouth, and page one.”

Jeff Kleinman of Folio Literary said, “Platform, for both novelists and memoirists, seems more and more important. It’s not the deciding factor for taking on a novel—that’s still the premise and voice—but it’s definitely a major consideration to know that an author actually has a plan to get the novel to consumers.” He said that plan could involve things as varied as email newsletters, radio, or TV shows, but it might also be as simple as being a good literary citizen—being engaged and interacting with other writers and the writing community. Like Maass, he was quick to add that writers should not focus primarily on platform: “It’s still all in the writing: the book itself has to deliver a great read.”

Watters emphasized that, like any good agent, she collaborates with her clients to assemble a convincing package for editors. She doesn’t write off anyone who has a fantastic manuscript but no platform or marketing expertise. But she does have to do a lot more work on such books, so it becomes a time-management issue.

If the market for fiction becomes more competitive and risk-averse due to continued dwindling sales, it’s natural for agents and publishers to shift their preference to authors who appear better positioned to sell—or at least to authors who demonstrate they have a vision for their career and the marketing work involved in that career.

Barnes & Noble’s Struggles Continue

At the end of 2017, the biggest chain bookseller in the US reported a worse holiday season than anticipated. Their sales fell 6.4 percent compared to the prior year. And the news hasn’t improved since then.

Just before Valentine’s Day, Barnes & Noble announced a “new labor model” that eliminated certain store positions to save $40 million annually. Even though the store claimed to be “pivoting” back to books in November 2017—emphasizing discoverability and bookselling interactions with customers—the layoffs appeared to target long-standing and full-time staff who would likely be essential to that goal. Their earnings report last month reflected a 6 percent sales decline during the most recent fiscal year, but B&N continues to grow its membership program and focus on the benefits of its new national book club launched in May.

So, are Barnes & Noble’s struggles preventable or inevitable—and who’s to blame? This is where you’ll find considerable debate. There’s a reliable contingent that argues Amazon is to blame or points a finger at bad government policy (see the Department of Justice case against Apple and the Big Five). Others see the resurgence in independent bookstores and believe B&N has failed to innovate or at least capitalize on its strengths. In a presentation at BookExpo on the future of retail, Kristen McLean of NPD said that the retailers who are losing right now are those swimming in debt, those who can’t innovate or don’t have the leadership to innovate, and those who don’t have the right footprint (they’re locked into particular real estate contracts, for example). She said physical retail is not dead, but retailers have to give consumers a reason to visit stores—there has to be an “experience”—and that highly local businesses will compete.

In a podcast from Knowledge@Wharton, a few marketing professors discussed what the future holds for the beleaguered retailer. Wharton’s Peter Fader said, “They’ve tried lots of different things from devices to experiences to broadening the merchandise. Nothing’s working. At this point, they haven’t found that hook to save the business; nor have they found the vision or leadership to give people any confidence in it.” Wharton’s Barbara Kahn said that while the retailer probably does a good job overall, “The problem is they’re not the best at anything.”

Digital Subscription Services Help Publishers with Discoverability and Backlist Profits

In the US ebook subscription landscape, two services compete against one another for market share: Kindle Unlimited and Scribd. KU offers more than a million titles for $9.99/month; many titles are from Amazon Publishing and self-publishing authors, with limited participation from the Big Five publishers (only Harpercollins as of this writing). Scribd, meanwhile, has deals in place with the Big Five.

Back in 2015 and 2016, Scribd’s model appeared wobbly: the unlimited model was showing strain. Scribd announced cutbacks to its romance selection and then limited subscribers to one audiobook per month and three ebooks per month. However, in 2017, Scribd announced it had become profitable and now has about 700,000 subscribers.

Earlier this year, Scribd returned to a (mostly) unlimited model for $8.99/month. The heaviest users of the service will continue to be limited in what they can consume. CEO Trip Adler says fewer than 10 percent of subscribers will experience such limitations, but those subscribers will receive recommendations for alternative reads if an “expensive” title is unavailable.

During a BookExpo panel this year, two publishers described how and why they sell ebooks through digital subscription services such as Scribd. The panel was moderated by Andrew Weinstein, a vice president at Scribd, and included Chantal Restivo-Alessi, chief digital officer of HarperCollins, and Nathan Henrion, vice president of sales for Baker Publishing Group, a Christian book publisher.