Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 104

April 3, 2018

Building a Strong Author Platform: It’s Not Just About the Numbers

When writers are trying to build platform—in order to land a book deal—they often ask me questions like:

How many Twitter followers do I need?

How many Facebook likes should I have?

How many website or blog visits are required?

How many people need to be on my email newsletter list?

Every agent or publisher will throw out a different number to such questions, and usually that number is made up. What’s even more frustrating: building a platform only to land a book deal usually ends up short circuiting. (Here’s why.)

A smarter and more strategic author should evaluate their platform strength on three levels:

ability to reach new readers,

ability to engage existing readers, and

ability to mobilize super fans.

Over at Writer Unboxed, I explain how to take a holistic view toward building your author platform.

April 2, 2018

Your Characters Don’t Have to Change to Be Compelling

Photo credit: Rooners Toy Photography on Visual hunt / CC BY-NC-ND

I recently finished watching the first season of Star Trek Discovery. When I was only a few episodes in, I felt a little betrayed, as it seemed this particular Star Trek iteration was discarding what I loved about the show: its idealism and optimism for the future. But I stuck with it, and eventually realized the show was inspecting the very existential roots of how Star Trek (or Starfleet) ended up that way in the first place.

As part of that inspection, we see two different versions of a few key characters: a Starfleet version and then the “evil” version. But regardless of whether we’re watching the “good” or the “evil” version, it’s clear that the character, at their core, is the same. It’s just that the forces that have been applied to them over time have created different outcomes.

Which brings me, in a rather roundabout way, to Bret Anthony Johnston’s insights into how to know your character. He says:

When the [character] “change” feels beautiful … I think it’s because the character has confirmed what we’ve hoped or suspected all along. Maybe the character hasn’t changed at all, but rather has finally been put in a situation where her truest self can be revealed. … Stories, to my mind, are never about change. They are always and only about the possibility of change.

His thoughts about character development feel particularly appropriate for our times. Read the entire essay.

For more from the latest Glimmer Train bulletin:

It Is All Ours to Make by Laura van den Berg

Writing Advice by Baird Harper

March 28, 2018

Writing Scenes: Crafting the Setup and the Payoff

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Learn more about getting a first-page critique.

First Page

My jaw clenched at Mother’s cryptic phone message the dorm aide left on my bed: Wednesday May 26, 1954, Sunday dinner at 2:00. Come early. Not another boring afternoon with my older sister, Mikki. I hadn’t had dinner with my family since Christmas break. Chemical compounds, histology, and patient charts occupied my time in Temple University’s nursing program.

Sunday, I took the bus over to my parents’ brownstone in Brooklyn, my heart chanting my old refrain: The first daughter is the one Mother loves, but the second is the one she keeps. Outside, in their newly unfurled bright green, oak trees were heralding a change. Inside, new paint, kitchen cabinets, and a large electric range revealed Mother’s pride in what she called, her “new permanent home.” After thirty years of military moves, my parents were settling down.

“Conni’s here,” my brother Joey, fourteen, yelled. Rolling his eyes toward Mikki, he mouthed, No attention for you today, and handed his collie a biscuit. Mikki kept bouncing her baby on her hip and chatting with Mother, who nodded at me as she slid a pie in the oven.

“How’s school, Conni?” Mikki’s husband Cal asked.

“Yeah, Conni,” Mikki chimed in with an affected Brooklyn accent. “How you doin’?”

Dad hurried in to give me a hug. “Thanks for coming, honey,” he whispered, and glanced at his watch. “Go wash up,” he said in his military voice.

By the time everyone had gathered around the dining room table and Dad pronounced the blessing, my watch said one forty-five. Mother rose as solemnly as if she’d won a victory medal and announced: “Your father will head up the new logistics department at NATO South.” With a faint smile, she added, “Late August, we move to Naples, Italy.” June, July, my fingers counted. Slowly her eyes touched everyone at the table, everyone but me. Didn’t she want me along?

First-Page Critique

“If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off.” —Chekhov

This first page ends with a surprise that launches the narrator out of her routine and into her story, but the way there is confused and rushed, and squanders many opportunities.

You’ve heard of Chekhov’s Gun, the principle that states every element in a dramatic work must either be relevant or removed, that whatever else we do as writers we must not hold “false promises” out to our readers. Consciously or not, we’re always loading Chekhov’s Gun. Every sentence we write is a rifle hung on the wall. Sooner or later it will—it must—go off.

Other terms for this are setup and payoff. We’re always either setting up some moment or scene, or paying it off. Since scenes are the building blocks of narrative, we should always be writing scenes.

Always be writing scene. It’s one piece of advice I don’t hesitate to give to give to my students. But for the advice to be practicable, the word “scene” must be understood to mean not just a dramatic incident characterized by action and dialogue, but background information regarding prior events and circumstances, physical descriptions, and other contextualizing matter necessary to support it: the setup.

When well-intentioned people exhort, “Show, don’t tell!” they forget that showing and telling needn’t be mutually exclusive, that they go hand-in-hand, that one is part of the other. When I say, “Always be writing scene,” I mean always be aware of the dramatic moment you are leading your reader to, that is being prepared or setup through telling. As long as you have that dramatic payoff in mind as your goal, the telling won’t feel inert; it will be imbued with tension, with the sense that Chekhov’s Gun will go off.

In this opening page, the dramatic payoff being set up is the moment when, at a dinner gathering at her parent’s Brooklyn home, the narrator’s mother announces that she and the narrator’s father, who works for NATO and has received a new assignment, will be moving to Naples, Italy.

It’s big news—news that (we may deduce from the novel’s working title, From Naples’ Ashes) conveys the novel’s inciting incident, the event that will launch the protagonist out of her status-quo routine into a series of dramatic episodes, i.e. a story. A wild guess tells me that those events will take place not on this side of the Atlantic, but in that bewilderingly beautiful Mediterranean port city cradled between Vesuvius and the Phlegraean Fields.

Though both setup and payoff are given to us in this opening page, the former exists more in embryo than as something developed.

Let’s start with the first sentence: “My jaw clenched at Mother’s cryptic phone message the dorm aide left on my bed: Wednesday May 26, 1954, Sunday dinner at 2:00. Come early.” Always be writing scene. Here the scene takes place in the narrator’s dormitory bedroom. Though the “cryptic” note specifies (improbably) the month, day, and year, we aren’t told when the note has been seen. Not in the morning, presumably, but some time later, with the narrator having returned home to find it on her bed. Does the time matter? It does in that time forms part of the setting, as does the dormitory room itself, which is likewise not described: a pity, given that this is a period piece.

It matters also insofar as the quality of the bedroom, the narrator’s mood or condition in coming home to it, the event from which she has just returned—all these things present opportunities not only to further contextualize this narrator’s situation, but to reveal her character. In the same vein whether the note is written on the back of an envelope or a torn piece of paper may not matter as far as understanding the basic scene is concerned, but it may make a big difference between a grounded, concrete, visceral experience and information derived from an experience. Though strictly speaking we get a scene here, that scene is more implied than tangible. It occurs in something like a vacuum in which the narrator’s perceptions are scarcely brought to bear.

On the other hand, by emphasizing the narrator’s jaundiced response to her parents’ dinner invitation, in setting her (and our) expectations extremely low, the author sets both her protagonist and us up for the surprise that, sure enough, will follow. Do we know there’s a surprise in store? Has the narrator told us? No, but we assume it.

The next paragraph puts us on a bus bound for that Brooklyn brownstone. Logistically the bus journey is at best confusing. A bus from Philadelphia (Temple University) to … Brooklyn? The narrator would have to ride several buses, and maybe a subway to boot. As confusing as this bus journey is, it’s also rushed. We dip into the narrator’s thoughts (“The first daughter is the one Mother loves, but the second is the one she keeps.”), but get none of the passing scenery. This rushed bus trip squanders other opportunities: the chance to establish the story’s domestic setting (setting up the contrast with the exotic Neapolitan venue to come), or to further elaborate the narrator’s situation vis-à-vis her parents, or to highlight an issue that’s been on the narrator’s mind and that may inform events to come. By elaborating on this bus trip and availing herself of these opportunities, not only would the author increase tension toward the inferred pay-off, she would add meat to her protagonist’s bones.

The author is in such a hurry she doesn’t let the bus reach its destination before, with a nod to those oak trees, thrusting Conni into her parents’ newly appointed kitchen. The effect is jarring to say the least. It also deprives us of the chance to see the brownstone from outside, or to have us experience, with Conni as she walks toward it from the bus stop, her memories, associations, and feelings vis-à-vis visiting her parents’ new home. More context; more character. Can the author and her opening do without these things? They can, but at a loss, I think.

The rushed quality persists through our introductions to Connie’s relations, her brother, her brother-in-law, her sister, and her father—none of whom are given to us physically, and whose dialogues (“How you doin’?”) are at best perfunctory. Of this ensemble the one developed character is Joey, the brother who “[rolls] his eyes toward” his sister: a rare moment of character evocation through action.

The rushed quality persists through our introductions to Connie’s relations, her brother, her brother-in-law, her sister, and her father—none of whom are given to us physically, and whose dialogues (“How you doin’?”) are at best perfunctory. Of this ensemble the one developed character is Joey, the brother who “[rolls] his eyes toward” his sister: a rare moment of character evocation through action.

To sum up: so intent is the author on delivering us to a surprise—the payoff—that she neglects to build sufficient context, characterization, and tension toward it. A dozen or so more sentences and this first page could fly. As written it functions, but only barely.

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.)

March 27, 2018

A Brief History of the Fantasy Genre

Today’s guest post is by author Jeff Shear (@Jeff_Shear).

George R.R. Martin says, “Fantasy is silver and scarlet, indigo and azure, obsidian veined with gold and lapis lazuli. Reality is plywood and plastic, done up in mud brown and olive drab.”

While fairy tales are ancient, dating back to the Bronze age, fantasy turns out to be a revival movement, rising from the grave of the recent dead. Mention of the word fantasy is minimal through through the twentieth century, with some peaks here and there depending on your source. Around 1945, fantasy took flight, soaring up and up, well into the twenty-first century. Why the change? What summoned the word fantasy back to life in 1945?

The first people I called on for an answer was my house painter, Rob Cordones, who was then painting my kitchen (lemon). He replied instantly to the question, “Edgar Allan Poe.” He then quoted him, “All that we see or seem is but a dream within a dream.” He added Mary Shelly (Frankenstein) and Bram Stoker (Dracula) to the list, all of whom wrote well before there was much mention of the word fantasy. Poe was dead by 1849, Shelly by 1851, and Stoker made it into the twentieth century, dying in 1912. Still, fantasy had a stake through the chest for another 35 years.

I put the question to Jane Friedman; her answer: “That sounds like a mystery worth chasing,” she said. “I wonder if Tolkien might’ve had something to do with it?” J.R.R. Tolkien hit the sweet spot all right. He and C.S. Lewis were members of a writers group called the Inklings, which met for nearly twenty years. The Lord of the Rings took 12 years to complete, not reaching print until 1949. The Hobbit published in 1937 might have served as kindling.

Ian J. Simpson, a brilliant Brit who’s known as the “Librarian” at the protean site known as the Geek Syndicate, says, “I suspect the term fantasy rose after World War II in part due to an increased optimism and need for release from the horrors of that time,” he wrote. “However, I’m thinking you could also attribute it to the publication of the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, first published in 1949. And then there was the publication and popularity of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950) and Lord of the Rings (1954).”

Simpson is spot on. The word fantasy does not appear in the English language used as a word for “a genre of literary compositions,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary, until 1949. And its first usage as such appeared in a title: The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. Added up, fantasy’s sudden growth in popularity was born of talent and terror in the 1940s, and specifically, I would argue, from singular event.

I’ve been haunted by it for many years by an introductory line from a five-time Emmy Award winning two-season HBO series, Carnivàle. Airing from 2003 to 2005, its story arc connected a dust-bowl depression narrative to an epic battle between good and evil. What stirred me was the show’s prologue, which opens on a very tight shot of the dimly lit visage of Samson, a lead character played by Michael J. Anderson. Samson is a little person who manages the carnival, and he has his own theory of fantasy. As he lifts his gaze to the camera in the show’s opening seconds, he grows oracular. His lips move before he speaks, and he slowly pronounces his lines, his voice like gravel stirred into sentences: “Before the beginning,” he intones, “after the great war between heaven and hell, God created the Earth and gave dominion over it to the crafty ape he called man. In each generation was born a creature of light and a creature of darkness, and great armies would clash by night in an ancient war between good and evil.” Samson tilts his head sadly, takes a pause, and tells us. “There was magic then… nobility… and unimaginable cruelty. So it was until the day when a false sun exploded over Trinity and man forever traded away wonder for reason.”

Trinity was the name of the first atomic blast, a second sun described then as a “cosmic light” that rose over ground zero at Alamogordo, New Mexico, in a valley called Jornada del Muerto (“Journey of the Dead Man”). This other sun was visible for 180 miles. But Samson, I fear, missed a beat. Humans did not trade away wonder for reason in that awesome moment. Reason is a good thing and in short supply. The opposite is true. At 5:30 a.m. on July 16, 1945, reason evaporated in a fireball as hot as the stars and rose into an iconic mushroom cloud requiring shelter, beneath the wings of fantasy.

March 26, 2018

5 On: Ian Thomas Healy

In this 5 On interview, author and publisher Ian Thomas Healy shares what he learned from his experiences with literary agents, what to look for when submitting to small press publishers, his feelings about Amazon KDP Select, and more.

Ian Thomas Healy (@IanTHealy) is a prolific writer who dabbles in different speculative genres. His popular superhero fiction series, the Just Cause Universe, is ever-expanding, as is his western fantasy epic The Pariah of Verigo. He is also the creator of the Writing Better Action Through Cinematic Techniques workshop, which helps writers to improve their action scenes.

When not writing, which is rare, he enjoys watching hockey, reading comic books, and living in the great state of Colorado, which he shares with his wife, children, house pets, and approximately five million other people. Follow him on Facebook.

5 on Writing

KRISTEN TSETSI: You have a day job, and you created and run Local Hero Press, which is currently accepting submissions from writers interested in contributing story lines to the existing Just Cause Universe, which you also created. I know how time consuming it can be to read submissions, so I’m naturally astonished that you’re also, somehow, always writing. You’ve written and published upward of 30 novels, and if you’re not writing, you’re editing, or you’re planning your next project, or you’re releasing a new book or a short story or a collection of stories. How do you balance all of that with fatherhood?

IAN THOMAS HEALY: You say it like it’s got a simple answer. I guess in a lot of ways, it is simple. My kids are and have always been supportive of my work. When they were younger, I got most of my parenting out of the way before bed and writing/publishing work done afterward. As they’ve gotten older, they’ve become much more self-reliant and I don’t have to stay up until midnight just to write (but I still do, because old habits die hard!).

IAN THOMAS HEALY: You say it like it’s got a simple answer. I guess in a lot of ways, it is simple. My kids are and have always been supportive of my work. When they were younger, I got most of my parenting out of the way before bed and writing/publishing work done afterward. As they’ve gotten older, they’ve become much more self-reliant and I don’t have to stay up until midnight just to write (but I still do, because old habits die hard!).

By the necessity of this lifestyle, I have become an efficient planner. I’m efficient because I’ve developed time-saving techniques for preparing ebooks and print books. I don’t agonize over editorial decision. I’m always churning my next project in my mind while working on the current one. As I’m writing one project, I’m preparing another for release, and likely plotting the next one.

I’m a planner, because having an outline in place makes it easier for me to write a string first draft, hopefully devoid of the kind of truck-sized plot holes that require major rewrites. I’ve been told by my beta readers that I send them some of the cleanest first drafts they’ve ever seen, which makes it more efficient for them to do the important task of Finding the Flaws.

In your online shares about writing and publishing, you seem perpetually optimistic and impressively driven. You move ever forward. In your private writer/creative mind, do you ever have moments of doubt or frustration (and if so, over what—can even be about writing, period, like whether the story will come together the way you want it to, or whether you ever get impatient about achieving X goal, or whether you ever have a hard time managing your creative focus, etc.)?

Of course I have moments of doubt and frustration. I’m a writer; in my low moments I don’t consider myself any more than a talentless hack.

Logically, I know I’m not, though, and I’ve managed to keep my company running in the black for six years now, which I suppose must mean I’m doing something right. My superhero stuff is keeping Local Hero Press in cover art and physical inventory, so it must be good enough to build and keep a fan base. It’s hard to stay down on myself for long, because I get to write stories I want to write and people give me money so they can read them. If that’s not a dream come true, I don’t know what is.

My biggest fear is that my readers will lose interest. “Oh, it’s just another superhero story. *yawn*.” But on the other hand, my non-superhero stuff, which I have very much enjoyed writing as well, simply doesn’t attract readers.

Am I taking advantage of the market interest in superheroes right now? You bet I am. Sell books while I can and tighten my belt when I can’t. I’m always apprehensive with a pending new release, though. What if this one doesn’t sell? What do I do then? Honestly, I have to keep going. Nobody can write an unending string of hits. Hopefully I got most of my stinkers out of the way early.

Am I taking advantage of the market interest in superheroes right now? You bet I am. Sell books while I can and tighten my belt when I can’t. I’m always apprehensive with a pending new release, though. What if this one doesn’t sell? What do I do then? Honestly, I have to keep going. Nobody can write an unending string of hits. Hopefully I got most of my stinkers out of the way early.

Related: My book Arena is releasing on April 1, 2018. It’s the latest in the Just Cause Universe of superhero fiction. This one is about an alien invasion, which I’ve wanted to write for a long time. Stop by Local Hero Press for the skinny on where to preorder. #alwayshustling

For a time, you wrote a series of blog posts on writing better action scenes (and ultimately released the book Action!: Writing Better Action Using Cinematic Techniques). What problems were you seeing in the action scenes you were reading that prompted you to want to offer instruction?

People have always complimented me on my action scenes, and a lot of them asked me how I did it. I never really thought about it until I considered writing the book. The answer was that I write action cinematically, like I’m writing the book version of the movie of my book, if that makes sense. A lot of writers still think of themselves as writers when they approach an action scene, but to be really effective, you have to think of yourself as a director, camera operator, and stunt coordinator instead. The writer just transcribes what those people are doing.

The main problem I see with action scenes in works-in-progress is that they are being written by people who clearly don’t want to write them. So many writers falter when they get to the point in their stories where an action scene is warranted, because it may be an unfamiliar aspect of storytelling to them. The only way to break that fear is to learn how to write an action scene, just like writing dialogue or clear narrative. There are tips and tricks, lingo and vocabulary to learn, and an understanding of pacing.

If I had to point to a single issue most writers have with action scenes it is improper pacing. Action scenes by their very necessity are fast-paced, and writers have a glorious tendency to want to describe things. After all, we’re told early on that it is important to show more than to tell. It’s important to do that in action scenes, too, but writers must learn to do so economically.

My best advice to write your first action scene is to stage it like a director would. Use storyboards or models to plan it. Outline your blow by blow events. Then when you write it, don’t stop until you finish the scene. Just like a director can go back and do reshoots, you can always fix problems in rewrites.

You write mostly non-mainstream fiction—superhero, steampunk, vampire, western fantasy—but you’ve also written mainstream fiction (your The Three Flavors of Tacos YA trilogy: The Guitarist, Making the Cut, and Scene Stealers). How does it feel to you when you’re writing mainstream vs. non-mainstream?

The Guitarist got me my last agent, but she couldn’t sell it. I wrote Making the Cut to try to give her something else to sell, but she couldn’t sell that one, either. I wrote The Scene Stealers, but I decided to fire her before I finished it.

The Guitarist got me my last agent, but she couldn’t sell it. I wrote Making the Cut to try to give her something else to sell, but she couldn’t sell that one, either. I wrote The Scene Stealers, but I decided to fire her before I finished it.

Writing mainstream can be fun if I’ve got a good idea for a story, but here’s the thing: the way I approach superheroes, there’s not a mainstream story I could write that I couldn’t make better by approaching it through a superhero lens. Want a murder mystery? Read Champion (JCU book 6). Want a New Adult coming-of-age? Read Just Cause (JCU book 1). Want a political thriller? Castles (JCU book 7).

You said in a “Daily Author” interview that you enjoy upending some superhero tropes and inventing new ones. What new tropes have you invented, and what tropes, if any, do you wish would die?

I’d like to think I’ve invented a trope, but I’m sure I haven’t. New tropes are extremely difficult to develop, and in today’s 6-second attention span, a trope becomes a meme and it’s gone a week later, consigned to the scrap heap of pop culture.

There are two tropes I hate for superheroes. The first is making a superhero a collection of powers and not a person first. I see that in lots of younger/less-experienced writers. They say, “This guy shoots fire from his eyes and he can fly and he’s a secret lab experiment gone wrong,” and I come back with, “Where does he go when he’s not a superhero? What’s his favorite kind of pie? What’s the last book he read? What scares him?”

I always remind people that a superhero story should hold its own weight without superpowers. They’re just special effects. The characters are what is important.

The other trope I hate is the origin story, and I say that having written a few. Hollywood has been the most egregious offender, because those making the movies tend to think of viewers as idiots who have to be spoon-fed an origin story or they won’t get it. Here’s a hint: people aren’t that dumb. Give them a chance. A good story will draw them in even if it’s in an established setting with established characters. I have intentionally written all the JCU books so anyone could pick up any book in the series and start it without feeling like they have to have read others first.

5 on Publishing

In an answer to a 2012 QueryTracker “Success Story Interview” question about what advice you have for writers seeking agents, you say, in part, “Learn what makes a good agent different than a bad agent, and realize it’s okay to say no if the agent making the offer is not right for you (a mistake I made with a former agent).” You’ve been represented three times. What did you learn in your relationships with agents about what makes a good agent and what makes a bad agent? And will you talk about the mistake you made with a former agent?

A good agent is a partner, a co-conspirator, and an advisor. They don’t make any money unless you make money, so it’s in their best interest to represent your best work if it is marketable. They may dearly love something you write, but if they can’t sell it to a publisher, all you have are dwindling hopes.

A bad agent wants you to change your story, drastically perhaps, to make it more attractive to prospective buyers. They’re putting the money ahead of the story, and I think that rings hollow. I once had a prospective agent tell me he liked one particular book I had queried, but he wanted me to rewrite it without superpowers. Yes, I could have done that and made an admirable thriller, but that wouldn’t have been me being true to myself. A good agent wouldn’t have asked me to do that.

It was hard to say no to that agent, especially since I’d been trying so hard to land one because that was what you were supposed to do. To me, the compromise would have been trying to write something I didn’t really want to write to make someone like me. At this point in my career, that is less important to me. Sure, it’s nice to be liked and respected, but it’s not my reason for doing this. I do it because I want to. Because I dream of telling these stories. Because I can’t not write them. It did make things harder for me, but I never stopped moving forward, and it’s gotten me this far. Hopefully, it’ll get me much, much further.

The mistake I made with my former agent was trying to write to what she wanted to represent instead of writing what I wanted to write. It put me into a lengthy creative funk, and when we parted ways, it was a relief.

In a more recent interview, you talk about the release of Caped: An Anthology of Superhero Tales. It was the first collection you’d edited and released that was composed entirely of work by other authors, and it came about, you said, because you “wanted to do small publishing the right way after being involved in it on the author side with a company doing it the wrong way.” What was that company doing wrong, and what should writers look for in a small press?

It’s real simple: pay the authors. If you can’t pay them, you’re not ready to publish them. If you can’t stand by your own contract and fulfill your obligations, you’re not ready to publish them.

It’s real simple: pay the authors. If you can’t pay them, you’re not ready to publish them. If you can’t stand by your own contract and fulfill your obligations, you’re not ready to publish them.

That other company, which I think is out of business now, breached their contract with me. It was for the best, because it inspired me to start Local Hero Press. When I did so, I promised I would never be “that guy,” the publisher who screwed up and didn’t make royalty payments or fulfill contractual obligations.

Writers should look for a small press with a steady stream of releases instead of a huge number in a short time period. The latter likely means the company is overextended and will collapse at some point. Likewise, a publisher should be run by someone with relevant, verifiable industry experience. Anyone can look at my books and see I’ve been releasing them since 2011 and see that they’re done with quality and care. I’m a writer, and I know what I want from a publisher, so as a publisher, I try to fulfill that need for other writers.

I asked you years ago whether I could interview you for 5 On, and between then and now—when I finally got to it—you never once reminded me about it. It was I who finally nudged you with something like an apology that it had taken so long, followed by, “Still interested?” Which made me think of the two types of self-promoters: those who’ll ask others for help marketing their work or improving their visibility—writers asking other writers for endorsements, or for help getting connected with a reviewer or interviewer—and those who, like you, at least seem to be completely self-reliant. Have you ever asked anyone for help, and what are your feelings about asking for help when it comes to marketing and publicity? What do you do to market your work?

I am a terrible marketer. Really, I’m awful. I could have reminded you years ago and as you pointed out, I didn’t. I have in the past asked people to write prefaces to my books, but that practice ended several books ago.

In this industry, a lot of success depends upon who you know and how they can help you get ahead. I’m bad at networking, too. Social media is a nightmare for someone like me who is so busy. Blogging requires a huge commitment and a regular, involved fan base. Meet-and-greets, hanging at the bar at cons, or professional groups are anathema to an introvert like me.

How do I market my books? I write them and put them on sale. I have a Facebook page and a Twitter account and I try to use those. I occasionally buy inexpensive advertising to try to make connections. Sometimes it works.

Many indie writers go back and forth about whether to enroll their ebooks in Amazon’s KDP Select, which requires that they sell their ebooks only on Amazon in exchange for a percentage of a global fund. You sell your ebooks on multiple platforms—Smashwords, iBooks, Kindle, etc.–and you also have audiobooks. A. Did you try KDP Select at one time (and if so, what did you like and not like about it), and where do you see most of your work selling? B. How easy or how difficult is it for an indie writer to have an audio book made, and how has having audio versions affected your sales?

I dislike KDP Select. It’s a zero-sum game, which means that your earnings come at the expense of someone else’s, or someone else’s come at your expense. The popular authors would be just as popular without the benefit of KDP Select and would still earn the lion’s share of royalties, but it wouldn’t happen by taking away potential royalties from other authors.

KDP Select is a tremendous money-maker for Amazon, and it’s important to remember that Amazon is not in the business of doing anything except making money by moving product. It does not have your best interests at heart. I may not have a lot of sales outside of the Amazon orbit (which includes CreateSpace and Audible), but I do have some, and those customers would not have access to my work if I only listed it on KDP Select. I don’t like that you are stuck in it for three months at a time. I don’t like that you have to be exclusive. Net royalties for KDP Select books are generally lower than they would be for non-Select books. I have seen this firsthand, having experimented with KDP Select to see if it would be a benefit to me.

I resisted getting into audiobooks for a long time because, well, I thought it would be difficult and time consuming to get into. When I finally took the plunge, I did so using the ACX platform, which is an Amazon-based application. It turns out that it is very easy to list your works on there and then accept auditions for narrators until you find one you like. As I began having audiobooks produced, I found myself enjoying listening to the chapters for review purposes during my commutes, and have since become an audiobook subscriber myself.

The audiobook “pool” is much smaller than the ebook pool, so right now it is easier for people to find my work in random searches than it is to find my ebooks. My audiobook sales are exceptional, and this month (March 2018), they are keeping pace with my ebook sales, which is a complete surprise to me. It tells me audiobooks are an important aspect of a complete line, and any author looking to maximize his or her exposure should definitely consider them.

You’ve said you often sell enough of your books at conventions—such as Myths and Legends Con, WhimsyCon, MileHiCon—to generate a profit. What have you learned about how best to attract people to your table and—after that—how to sell books? Is there a way to do a convention wrong?

A good display helps. A smile. Talk to people. Ask what they like to read. Listen to them. If you can’t have a conversation, you can’t sell a book. It’s a give and take. Potential buyers will tell you what they want, even if they can’t put it clearly into words. Listen to them and then you might have a book that can make a connection with them. I actually do a lot of repeat business at cons from people who tried one of my books and liked it enough to buy more a year later.

Know your con ahead of time. Some cons are more oriented toward movies and television, or art, or cosplay, and you might not be able to hustle enough sales to those people to cover your expenses. Some are expensive, and even with a good fan base you might end the weekend in the red even if you had decent sales. A huge con doesn’t necessarily mean huge sales. You could be a very tiny fish in a big ocean. Try to find readers’ cons, because those are the people who do love books and love to read them. Those are your people.

As far as things to avoid at cons, don’t let people who are clearly not going to buy something stand at your table and take up your time wanting to talk about aspects of your work (or their work!) at length. Every con has several of these people who will stand there talking at you and possibly preventing a new customer from coming up to take a look. You have to learn to recognize the difference between someone who wants a brief chat and someone who wants to suck away your day. Ask them if they’re going to buy something and if not, ask them to please clear the area. You’re a shopkeeper, and even though “the customer is always right,” they don’t get to be considered a customer unless they spend money with you. Otherwise, they’re just loitering.

Finally, don’t be afraid to ask someone to buy. I’ve had more people come back to my table an hour or a day later after talking with them because they couldn’t stop thinking about one of the books after I’d talked about it with them. That’s how you sell stuff. Plant seeds; they’ll grow.

Thank you, Ian.

March 22, 2018

What You Need to Write Your First Book After Age 50

Today’s guest post is by Julie Rosenberg (@J_RosenbergMD), author of Beyond the Mat.

As a girl, I absolutely adored the Little House on the Prairie series. I would wake early in the morning, sit at the kitchen table, and devour each book. I was inspired by young Laura and her adventures on the prairie. What I could have never known then is what an inspiration Wilder the author would be for me as an adult.

Wilder didn’t publish her first book, Little House in the Big Woods, until she was 64. During the earlier part of her life, she had taught and farmed and raised a family. She had written a bit on the side for small local publications in her fifties, but it wasn’t until her retirement investments were wiped out in the 1929 stock market crash that she wrote Little House in the Big Woods. The book was published in 1932, and it was the start of a writing career that has resulted in the beloved TV series, spin-off books, and millions of copies sold. Like Frank McCourt, whose Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir Angela’s Ashes was published when McCourt was 66, Wilder is proof that it’s never too late to write a book.

I’ve previously written about why I believe that it is not only possible but in some ways advantageous to start a writing career after the age of 50 (see “Is it Too Late to Start Writing After 50?”). I am all for older writers taking the plunge, but it is important to be aware that it will be a different process than starting a writing a career at 25 may have been.

Here are a few things that are particularly important in order to start writing after 50.

Realistic Expectations

First and foremost: Set realistic goals. Is this book going to change your life? No. After publication, you will not be a different fifty-plus-year-old person. You won’t be richer (most likely) or instantly more popular or somehow more glamorous. You will be pretty similar to the person you were before, only this fifty-plus-year-old person has written a book. You might get some good reviews and some nice invitations to speak, but, for the vast majority of authors, your life will not be utterly and instantly and dramatically transformed as the result of having written a book. So ask yourself: What are you hoping to get out of the experience?

Time

Finding time to write is hard at any age, and at this stage in your life, you likely have more commitments and responsibilities than you did in your twenties. But the need for self-discipline when writing a book cannot be underestimated, and, establishing writing discipline is not easy. Stop trying to “find time” to write; you need to make time.

Also, keep in mind that writing is a solitary exercise. You must schedule and tolerate alone time. I am a morning person. I devoted time in the wee hours of the morning to write. I also write better in blocks of time, so I utilized weekends and blocks of vacation time for writing. I sought out quietude, as I don’t focus well with background noise. I found scenic places in the mountains of Woodstock, Vermont, and by the ocean in Sanibel Island, Florida, to write; changing environments over time helped to spark my creativity. While your preferred timing and choice of venue may differ from mine, you must allocate time to write on a regular basis. Document your progress in a journal, as you may find that certain days and times are more productive for you and foster better discipline. That said, it’s also important to pace yourself. If you need to take a break, take one. Walk in nature. Have coffee with a friend. Taking scheduled writing breaks throughout your writing process is a healthy habit and should help to keep your thoughts and ideas fresh. Try to balance breaks with a sense of accountability. Just make sure that you are setting goals—they could be time-based goals or word count goals—and meeting them.

Self-care

When taking on something new, maintain good health by staying in shape both mentally and physically. It’s difficult to stay disciplined and write constructively if you are stressed and exhausted. A daily meditation practice (even as short as 5 minutes per day) will help you to discipline your mind—to de-stress, focus, and erase mental blocks. It will help silence the critical voices in your head. Meditation will help to train your mind to get into the “writing zone” more quickly.

Confidence and drive

As a writer, you must have self-confidence in your ideas and your ability to successfully execute the work. If you’re a bit of a perfectionist like me, you must accept that your first draft will not be perfect. Nor will your second draft.

All writers feel frustrated at times and want to quit. So, it’s not just you. You may have, at this stage in your life, reached some level of success in other arenas, so it may be exasperating to find yourself a novice again. Voice the commitment to hang in there when things get tough. I found that continually learning more about the skill of writing as well as about the publishing industry helped me to more fully embrace this new discipline. A can-do attitude is essential.

Community

Writing is a solo endeavor, but that doesn’t mean you have to do it all alone. You may want to join a writing group or engage a writing coach so that you have regular check-ins and can receive encouragement and support as well as constructive feedback. I worked on my book manuscript with the help of a developmental editor to keep my writing on track and to have a system of checks and balances in place.

I also highly recommend teaming up with younger people in the industry. You may be accustomed at this stage in your life to dealing with the most senior people in their fields. However, while they might have some perspective because of age, you don’t necessarily need that, as you have your own. A younger person offers fresh eyes, with accompanying insights and clarity about the publishing industry. The same way you don’t want to be judged for your age, don’t assume that because they are younger, they don’t have anything to offer. A little bit of youthful energy might be just the magic ingredient that you need.

Parting advice

Recognize that publishing is a business. If you go through a traditional publishing house, publishers need to be certain that you have the ambition and fortitude to do all the things that it takes to sell books. Showing up with a sense of vitality will help to improve your chances of getting an agent or an editor to take on your work, but ultimately what matters is what you put on the page. There’s no reason that age needs to be a part of the conversation you have with publishing professionals. On the other hand, your life experience affect your writing and your approach to a new endeavor, so, if your age offers you an advantage, use it! I did—and I wrote a better book than I ever could have written twenty years ago. And you can, too. Just always remember: Your talent doesn’t have an expiration date.

The post What You Need to Write Your First Book After Age 50 appeared first on Jane Friedman.

March 21, 2018

The Pleasures of Genre

Photo credit: kickize on VisualHunt.com / CC BY-SA

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Learn more about getting a first-page critique.

First Page

January 1, 1806 | Stanford On Avon, Northamptonshire

“A burial is not the way to start a day, let alone a year.”

Cranny—Lucien Charles Sedgewick, 12th Duke of Cranleigh—took no comfort from his friends’ grunts of agreement. The corpse-grey morning seemed surly, as if it knew 1806 had arrived with Death as its companion.

And a close friend—Edward Melton, heir to the Earl of Highgate—was Death’s first prize.

Faust squeezed Cranny’s shoulder. “Come on, Cranny. It’s time.”

Cranny trudged over the snowy ground and under the earl’s stricken gaze, joined his friends around the funeral wagon. For the first time in two years their close-knit group of ten were together, though not as they’d imagined. Not with Edward in the casket. Even Chipper had left his sick bed and made the arduous journey north, though ill health rendered him too weak to do more than walk behind the casket.

They carried Edward’s casket into the Melton family graveyard where gravestones huddled together like hardened conspirators, forever guarding their grim spoils, even as time and the elements erased the epitaphs they bore. Solemn funerary attendants stepped forward. The urge to scream at them to be gone clawed at Cranny’s throat, but dear, departed Father’s edict—whipped into his flesh and burned by pain into his memory—prevailed.

Do nothing to bring shame on the family name.

They surrendered the casket to the attendants and soon the drone of the clergyman’s voice joined the low moan of the wind. Eyes narrowed against the whirling snow, Cranny braced himself. As the casket descended into the grave a great knot formed in his throat, every creak of the straining ropes hitting his brain with all the power of a blacksmith’s hammer striking the anvil. Edward did not belong in the waiting maw in the cold earth. Not at twenty-six.

Guilt crunched Cranny’s heart, and his blood hammered in his ears while his muscles bunched and quivered with an odd need to do… violence. Some unspeakable cur had attacked Edward and his men and left them dead or dying while the snow bloomed scarlet with their blood. And it is all my bloody fault. His chest hollowed and the ache behind his ribs sharpened, snatching his breath. His vision blurred. God’s teeth. I will not cry like a whelp. Spine rigid, he thrust his hands into the pockets of his greatcoat and pulled in a lungful of frigid air.

He would see the murderer hang. Dammed if he wouldn’t.

Another gust of wind whipped about him, its icy claws slapping at his greatcoat. What lay beyond the grave? The image of a small, white-haired ghost flashed through his head on a stumbling heartbeat. What in Hades? Perhaps the memory was a reminder that life was fragile. Transient. Perhaps it was a reminder he had yet to fulfill his obligations to his dukedom, lest he fall victim to the family curse and end up in an early grave too.

God. Death was a damned sight more appealing …

First-Page Critique

No one had more lovers,

No one needed love more

Than PLEASURE’S DAUGHTER.

She had seven lovers

But only one love and he was…

The King of England.

A “genre” is a type of something, for our purposes a type of novel. Sci-fi, mystery, detective, western, thriller, fan fiction, YA … these are just some of many popular genres of the “novel”—which, once upon a time, was itself a literary genre.

A genre implies all the conventions and expectations that adhere to it. As John Mullen explains in How Novels Work, his superbly insightful survey of fictional techniques, “A genre is not just a category for literary critics, it is also a resource for the writer. … Genre offers a challenge by provoking a free spirit to transcend the limitations of previous examples.” Genre gives the writer something invaluable: a set of requirements or constraints to work with or against, rules to obey, or flout—or both.

Novelists and critics alike haven’t always viewed genre in such a positive light. As G.K. Chesterton, whose own detective novels featured a priestly sleuth named Father Brown, lamented back in 1901: “Many people do not realize that there is such a thing as a good detective story; it is to them like speaking of a good devil.” While some, like George Orwell, admitted to enjoying Sherlock Holmes and Dracula, even Orwell drew the line at taking genre fiction seriously.

Others were even less charitable. “Reading mysteries,” Edmund Wilson wrote, “is a kind of vice that, for silliness and minor harmfulness, ranks somewhere between crossword puzzles and smoking.” Such appraisals didn’t go unchallenged. When Wilson’s views went public in 1944, they provoked more letters of protest than anything he’d ever written. Among the dissenters was Raymond Chandler, whose detective novels Wilson judged inferior to anything by Graham Greene. Chandler’s response? “Literature is bunk.”

More recently when President Obama awarded horror novelist Stephen King the Medal of Arts, it caused an uproar among critics, including Harold Bloom, who sniffed, “King is an immensely inadequate writer … [of] what used to be called ‘penny dreadfuls’”— another genre.

Given the rise in both popularity and sophistication of the young adult novel over the past ten years, it’s no longer so easy to look down on genres from the lofty heights of “literary fiction” (itself a genre, albeit with an exalted air, and not really comparable with others since its conventions aren’t fixed). Far from being frowned upon, genre is seen, especially by younger writers, as a vital and vitalizing force. More and more literary novelists—David Mitchell, Annie Proulx, Gish Jen, Jhumpa Lahiri, Haruki Murakami, and Kazuo Ishiguro, to name a few—incorporate or pay tribute to genre through hybrid works. The Hunger Games is romance. So is Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Emily St. John Mandel’s critically acclaimed Station Eleven is science fiction. Literary fiction’s subsumption by other genres and vice-versa has become so pervasive one must wonder what distinction if any can still be claimed by “pure” literary fiction beyond … uhm … pretentiousness.

Tempting though it may be to flout or otherwise challenge the conventions of genre, there’s also a lot to be said for playing by the rules. In the case of this first page, the genre is the regency romance, a subgenre of the romance novel, the conventions of which Margot Livesey outlines for us in The Hidden Machinery, her delightful book of essays on the novelist’s craft:

The lovers are unlikely in some obvious way.

They meet early and are then separated—either physically or emotionally—for most of the narrative.

There must be significant obstacles—“dragons and demons”—to be overcome.

Changes of setting, even from drawing room to street, are vital for revealing the characters and moving the narrative forward.

Many minor characters will assist the lovers on their journey.

A subplot, or two, is required to keep the lovers apart, to allow time to pass, to act as a foil to the main plot, and to entertain the readers.

Set in the time of the British Regency (1811–1820), regency romances evolved from the “novel of manners” as practiced by Sir Walter Scott and Jane Austen, who dramatized the domestic affairs of the English gentry. The modern regency—written long after but set in the same period—was first popularized by Georgette Heyer, who penned several dozen between 1935 and her death in 1974.

With its provocative opening (“A burial is not the way to start a day, let alone a year”), our first page holds out a model of the form. Though starting right off with dialogue has its risks (namely the confusion attendant with confronting readers with an ungrounded, disembodied conversation-in-progress), it also gets right down to business—namely the business of evoking character, as this opening dialogue does very well. We haven’t met Cranny; we don’t even know his name, yet already this dialogue nails him to the page. It does more: it nails down the point-of-view. Until further notice—to the bottom of this first page, anyway—everything will be filtered through Cranny’s gloomy sensibilities.

That filtering makes use of a technique known as “free indirect discourse” by which the narrator’s voice is colored by the point-of-view character. Note, in the fourth paragraph, the choice of modifiers and verbs (“trudged”, “stricken,” “arduous”), how they convey Cranny’s grim outlook.

Fifth paragraph: the gravestones “huddled like hardened conspirator’s”—more Cranny. All is filtered through his perspective, his personality. Though the “free” in free indirect means that it could be, nothing here is neutral, objective; everything is flavored by our protagonist’s bleak disposition. It’s the salt in this stew.

Rather than attempt to describe characters’ abstract feelings (hard if not impossible), wise writers evoke them as concretely as possible. With “Guilt crunched Cranny’s heart, and his blood hammered in his ears while his muscles bunched and quivered” this author does just that, balancing abstractions (“guilt”) with active, solid nouns (“blood/muscles”) and verbs (“hammered/quivered”). This is but one of many approaches the author uses to render Cranny’s emotional state, from dipping into his thoughts (“I will not cry like a whelp”), to precisely rendering his visible gestures (“he thrust his hands into the pockets of his greatcoat and pulled in a lungful of frigid air”).

Whatever else good writing does, it evokes character. A good rule for determining what to put in and what to leave out: If it evokes character, keep it.

Through a wisely chosen, thoroughly engaged close third-person narration, this author injects us richly, vividly, clearly and precisely into this opening scene, one we inhabit thoroughly. The weather (the wind, the whirling snow), sounds, temperature, thoughts, memories, opinions, and attitudes—all are there, as are actions, gestures, etc. “Literary” or not, genre or no genre, this is good writing.

Through a wisely chosen, thoroughly engaged close third-person narration, this author injects us richly, vividly, clearly and precisely into this opening scene, one we inhabit thoroughly. The weather (the wind, the whirling snow), sounds, temperature, thoughts, memories, opinions, and attitudes—all are there, as are actions, gestures, etc. “Literary” or not, genre or no genre, this is good writing.

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.)

The post The Pleasures of Genre appeared first on Jane Friedman.

March 19, 2018

What I Earned (and How) During My First Year of Full-Time Freelancing

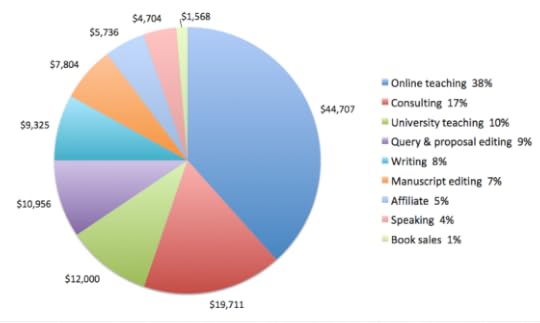

Note from Jane: In 2014, I made the leap from conventional, full-time employment to a full-time freelance career. On the one-year anniversary of that transition, I wrote a feature about it for Writer’s Digest magazine, detailing my earnings to the dollar. In honor of the release of my new book, The Business of Being a Writer, I’m re-publishing that article here today, with those first-year earnings.

Here’s the truth: I never had a freelancing dream. I was happily and continuously employed for 15 years after college graduation. Yet as I grew in experience and knowledge, I found myself increasingly at odds with the red tape and inevitable office politics that come with even the best of jobs. I started to wonder if I’d do better and be happier on my own.

Even though I’ve spent most of my career working in the publishing industry, I doubted my ability to build a sustainable freelance life. There are so many negative messages surrounding freelance careers—how hard it is, how you have to be prepared to hustle, how it’s more competitive than ever, and let’s not forget: the great masses are all trying to write and will do so for free.

I internalized those negative messages. I thought about all the reasons I would fail: I don’t like pitching, I’m a terrible networker, I procrastinate, and I’m not willing to work long hours.

After several years of weighing the pros and cons, I made the jump, with all my fears intact. (The fears never really go away.) Now I’m one year into my freelance life, and I’ve beaten my previous annual income by more than 50 percent.

Your motivations or desires to freelance might be different than mine, but the process of transitioning away from conventional employment will raise similar questions and psychological barriers. While I was positioned to do well given my career history, it was by no means a golden ticket. Someone else with the same set of experiences and connections could find themselves empty-handed and struggling (and in fact I know of some who are). So what laid the groundwork?

3 Key Qualities of a Successful Freelance Career

Here’s the good news: You don’t need all three of the following assets for a successful freelance career. You can focus on one to begin.

1. Connections and relationships

Freelancers’ first clients often come from previous employers or an existing network. You tap the connections you already have, and build from there. Each job you successfully complete or each client you satisfy creates word of mouth. Each new editor you meet holds the seeds of new relationships with other editors. Former colleagues who believe in your work refer new opportunities your way. This is networking at its heart.

Writer Grace Dobush, who has been freelancing full-time for three years, says that the biggest thing that prepared her for success was networking. For example, she met her editor at Wired through calculated stalking: determining who at the magazine might be willing to meet her and then reaching out to editors, finally meeting one in person and developing a relationship with her. “You’ve got to create the career you want yourself, knitting together the relationships you create with the threads that interest you. No one else can do that for you.”

If you’re literally starting from zero, relationship building might not be the area to focus on, especially if you lack confidence in your writing skills or are still building your body of work. Even I personally don’t focus on building connections; instead, I try to draw people to me, which brings us to …

2. Visibility

My biggest strength has been putting myself out into the community, continuously and consistently through online media. As marketing guru Seth Godin has said, “I think that showing up every day for 10 years or more in a row gives people a hint as to what it is you’re actually trying to accomplish.”

I’ve been blogging since 2008. I wasn’t very good at first, and even three years in, I considered my effort fairly average and a bit unfocused. I wasn’t particularly charismatic, witty, or a big personality—but I was attentive and genuinely wanted to help people. I said yes to every interview and guest post opportunity, even if it meant free labor. People tend to find me because of all my self-produced online work and the surrounding footprint through social media. When it came time to jump, I was visible to an audience I had built over years.

Similarly, Benjamin Vogt, a freelance writer and gardening consultant (and former writing professor!), says a key factor has been his attitude of saying yes to everything. “If someone asks you to talk or write an article or sends you questions, address it right away. I’d also say being far too active on social media has helped make connections.” Vogt’s passion for sustainable and native gardening led him to blog, which led him to a community, which led him to better blog posts, which led to freelance articles, which led to garden tours and garden consults, which led to a weekly column.

Today, I continue to help people and organizations in ways that don’t benefit my bottom line, to increase my visibility for paying opportunities. But you do eventually have to make difficult judgment calls on which opportunities really deserve “yes.”

3. Time

Many experts advise writing or freelancing on the side until it overtakes your full-time work, to reduce your risk and experience a more seamless transition. Not everyone has the luxury of time, but if you do, then take small steps to build the assets just discussed, not to mention your portfolio. You’ll gain confidence and resources needed for freelancing—or you may realize that it isn’t actually the dream you thought it was.

When I initially started blogging and created my own website, I didn’t intend for it to pave the way to a freelance career. Rather, I wanted to build an identity that wasn’t tied to any particular company; I wanted to be visible to future employers and opportunities. The happy result? When I had only three months from the time I gave notice at my full-time job until I was fully independent, I already had four years of groundwork laid, if you start the clock from the year 2010, when I first put up my website.

Before writer and editor Ginger Moran went freelance, she took several years to explore the alternatives to full-time employment. She accepted side gigs coaching other writers, and took time to get her book and essays published. Then she added certifications as a life coach and creativity coach that rounded out her degree in creative writing. She reached out to mentors and advisors, and put all her spare time and energy into her future freelance life. “When it was time to leap, it was still scary, but it was worth the risk. I have never once for a single second regretted it,” she says

5 Steps You Can Take Right Now to Build a Freelance Life

If you’re already freelancing or writing on the side, list these gigs religiously in a spreadsheet. How did these opportunities come to you? How much did you earn? How much time did you spend on the work in relation to what you earned? It’s important to see and track where the work comes from as well as the profitability of the work.

Establish your own website under the name you will write or work under. (This could also be a company name.) Don’t wait until the day you open for business; do it on the day you decide you’ll develop a business.

Commit to a weekly practice that Grace Dobush did: Meet at least one new person a week. Invite a new person to coffee or lunch (and offer to pay!), or attend a networking event with the goal of building at least one new professional relationship. But, as Dobush advises, don’t meet only people who could give you work. Meet other writers, marketing people, tech entrepreneurs and nonprofit folks. Allow network serendipity to work its magic.

Research industry events or conferences where you can meet people important to your freelance life. Invest in attending that event every year; go to see people and to be seen. Plus, showing up where the opportunities are concentrated can be critical for those trying to build a freelance career outside of major cities.

Aside from proactively building connections, brainstorm how you can be more visible to your intended audience. There is no one-size-fits-all solution; everything starts with your assets and what you can comfortably sustain. My key asset was a blog. Assets you might have or build: a podcast, a highly visible volunteer position, a regular teaching gig, guest writing for influential websites, a reading or event series you organize in your town, a witty Twitter account. As writer Bethany Joy Carlson says, “I can’t control whether someone chooses to do business with me, but I can control whether and how I am getting my message out to my audience.”

While you might have a specific type of desired work, assume and plan from the outset that you’ll accept many types of gigs as you build up the more desirable opportunities. This has been true for freelancer Andi Cumbo-Floyd. “Sometimes, I think we consider ourselves to have failed or sold out if we do things that seem less artistic or more commercial,” she says, “But those things allow me the space to do what I really love. If I need to write web copy and tweets to have that opportunity, I’m happy to do it.”

One income stream I’ve developed that I never quite expected has been editing queries and book proposals. Initially, I wasn’t sure how to offer such critiques while making it worthwhile for both me and the client, but eventually I found the right model—which still continues to evolve. Writer and editor Lydia Laurenson says that this evolution is inevitable. “After ongoing conversations with other independents, you will learn that these failures and pivots are okay, and you will start to see helpful patterns in them, but the fact remains that resilience to failure is a key quality.”

Understand the Very Real Psychological Barriers

When I spoke to other freelancers about their transitions, fear was a consistent part of the equation. Dobush says, “Even the most successful freelancers have moments of doubt and are often on the cusp between making it and not making it.”

Looking back, I probably could’ve have transitioned successfully a couple of years before I finally made the move, but the insecurity of not having a regular paycheck prevented me, as well as fear of not knowing if I was suited to the freelance lifestyle.

After making the switch, what I discovered is that until you truly commit to giving up the day job, it’s hard to behave as a freelancer would because your head space, time, and energy remain consumed with traditional employment. You can be blind to the opportunities around you. At some point, you must leap and assume the net will be there. The great writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe once wrote, “The moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one’s favor all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance, which no man could have dreamed would have come his way.”

I find that largely true, but be careful when asking other people if you should commit to freelance. By and large, people did not encourage me; mostly, they made me second-guess myself. Even when I announced I was leaving full-time employment, despite the majority of positive messages, I still received warnings, e.g., “You’ll go from a full-time job to a 24/7 job,” and “Welcome to the cliff. No parachute, golden or otherwise.”

Even after a successful first year, it still amazes me every month to see the money come in consistently. I’m really making that happen? I’m proud of the accomplishment but fear still lurks that one day the “magic” will run out. I’ve come to accept that feeling as part of my new job.

My First Year of Freelance Income (before taxes)

Online teaching. This includes all teaching I do on my own as well as in partnership with other companies.

Consulting. My clients include authors, publishers, universities, nonprofits, literary journals, and digital media companies. This bucket is a mix of short-term hourly consulting as well as long-term arrangements that extend six months or more.

University teaching. I worked as an adjunct at the University of Virginia.

Query and proposal editing. I offer writers assistance with their submissions materials.

Writing. This is traditional “freelance writing”—where I’m paid for my writing contributions to magazines, anthologies, websites, and so on.

Manuscript editing. This is an area where I turn down more work than I accept, since I prefer other jobs.

Affiliate income. This is primarily from being an Amazon affiliate, but I occasionally get referral fees when I recommend classes or other products.

Speaking. I speak at about a dozen events per year, but they tend to pay little. I accept invitations because it helps keep me in front of potential clients and other opportunities.

Book sales. This is from my self-published work, Publishing 101, released in late 2014.

Some people may be surprised that more of my income isn’t from writing. Can I really call myself a writer or freelance writer? Yes. It’s common for even “full time” writers to make less than half of their income from writing.

How Has My Income Changed Since 2015?

Today, the lion’s share of my income comes from helping writers with their submissions materials and business consulting with individuals, businesses, and organizations. Online teaching is next, followed by writing. In 2018, it’s possible that writing work will become my second biggest revenue generator, partly due to the success of my email subscription newsletter, The Hot Sheet. Speaking is my smallest earnings category, which I hope to change by increasing my speaking fees. I stopped taking manuscript editing work and I stopped adjuncting at the University of Virginia.

Recommended Resources

Recommended ResourcesMake a Living Writing by Carol Tice

Chris Guillebeau’s The $100 Startup or his free manifesto (old but still relevant), 279 Days to Overnight Success

Nicole Dieker at Ask a Freelancer or Writing and Money podcast

Who Pays Writers? to find out what publications pay

Learn More About Making a Living as a Writer

Check out my book from University of Chicago Press, The Business of Being a Writer.

The post What I Earned (and How) During My First Year of Full-Time Freelancing appeared first on Jane Friedman.

March 16, 2018

My New Book, The Business of Being a Writer, Is Now Available!

Thousands of people dream of writing and publishing full-time, yet few have been told how to make that dream a reality. Some working writers may have no more than a rudimentary understanding of how the publishing and media industry works, and longtime writing professors may be out of the loop as to what it takes to build a career in an era of digital authorship, amid more competition—and confusing advice—than ever.

Releasing today, my newest book, The Business of Being a Writer (University of Chicago Press), takes it on principle that learning about the publishing industry will lead to a more positive and productive writing career. While business savvy may not make up for mediocre writing, or allow any author to skip important stages of creative development, it can reduce anxiety and frustration. And it can help writers avoid bad career decisions by setting appropriate expectations of the industry, and by providing tools and information on how to pursue meaningful, sustainable careers in writing and publishing on a full-time or part-time basis.

Despite ongoing transformations in the publishing industry, there are fundamental business principles that underlie writing and publishing success, and those principles are this book’s primary focus. Writers who learn to recognize the models behind successful authorship and publication will feel more empowered and confident to navigate a changing field, to build their own plans for long-term career development.

One underlying assumption in this guide is that many creative writers—particularly those pursuing formal writing degrees—want to build careers based on publishing books. It seems like common sense: literary agents sell and profit from book-length work, not single stories or essays; and getting anyone (whether a reader or a publisher) to pay for a book is easier than getting them to pay for an online article or poem.

But book publishing is often just one component of a full-time writing career. Perhaps you’ve read personal essays by debut authors “exposing” the fact that the average book advance does not equate to a full-time living for even a single year. Such essays reveal unrealistic expectations about the industry—or magical thinking: I will be the exception and earn my living from writing great books.

My guide does offer guidance on how to get a book published, a milestone that remains foundational to most creative writing careers. But because very few people can make a living solely by writing and publishing books, it goes further, showing why this one pursuit should not constitute one’s entire business model. Earnings can come as well from other sectors of publishing, other activities that involve writing and the types of skills one picks up as a writer. Online media and journalism, for example, now play a significant role in even fiction writers’ careers, so The Business of Being a Writer spends considerable time on skills and business models important to the digital media realm. When combining these skills with the entrepreneurial attitude and knowledge this guide teaches, a writer will be better prepared to piece together a writing life that is satisfying and sustainable. In the end, some writers may discover they prefer other types of writing and publishing—and not just because it’s tough to make a living wholly from books.

If you are a writer looking for the business education you feel you never received, I hope this book provides the missing piece. While I try to be encouraging, and want you to feel capable and well informed, I don’t sugar-coat the hard realities of the business. When you decide to pursue a writing career, you’ll experience frustration, again and again, and not just in the form of rejection letters. But it helps to know what’s coming and that your experience is normal. Writers who are properly educated about the industry typically feel less bitterness and resentment toward editors, agents, and other professionals. They are less likely to see themselves as victimized and less likely to be taken advantage of. It’s the writers who lack education on how the business works who are more vulnerable to finding themselves in bad situations.

To learn more about this book

Read the review in Publishers Weekly, which says the book “is destined to become a staple reference book for writers and those interested in publishing careers.”

Read the early Goodreads reviews from writers.

Review the table of contents for the book.

Here’s my Q&A with the Chicago Manual of Style on the business of being a writer.

Visit the companion website for the book.

Buy the book at Amazon.

The post My New Book, The Business of Being a Writer, Is Now Available! appeared first on Jane Friedman.

March 15, 2018

There Are Only 2 Types of Stories—and Why That Matters

Photo credit: JD Hancock on Visual hunt / CC BY

Today’s guest post is by writer Eli Landes (@writing_re).

You may have heard the argument before: There are only a finite number of possible story types.

No matter how much we might wish otherwise, creativity is as limited as we are. We can never invent something truly unique. The most we can hope for is to sprinkle a dash of novelty into the same worn-out trope and, with an illusionist’s flourish, let out a cry of ta da! and hope no one in the crowd sees through the trick.

And so, the argument goes, though there are millions or billions or even trillions of stories in existence, there are really only a very limited amount of stories possible.

How many?

I’d like to argue that there are just two.

I know. You’ve probably heard a different number before. And I’ll get to that in a bit. First, though, I’m going to deal with a more pressing question:

Why should you care?

The thing is, it actually matters. Like a chef, knowing what defines the concoction you’re about to create will help you figure out how to make it work.

And how to stop it from failing.

The two categories are:

Stories about abnormal characters, and;

Stories about abnormal situations.

I’ll explain.

Abnormal Characters

Superman. Sherlock Holmes. James Bond. Gandalf. Shrek. All these characters have something in common.

They’re nothing like you or me.

They’re the basis of the first type of story. Books about abnormal characters—characters that are different to the average person on the street. Maybe he has superpowers. Maybe she’s unnaturally brilliant. Whatever the case, these characters have something that makes them stand out from the crowd.

And that’s the essence of what makes these stories work. Take James Bond, for example. In Thunderball, 007 has to stop a powerful crime syndicate after they steal two atomic bombs. Sure, it’s an interesting plot, but that’s not what catches your attention. Even before you read the story, you know that Bond will dodge the bullets, survive the explosions, and defuse the bombs—all while keeping his tie immaculately straight.

It’s James Bond himself that captivates the reader.

The situation the abnormal character faces is far less important. It could be an abnormal situation—like the plot of Thunderball—or even a perfectly normal situation. In Jim Butcher’s Spider-Man: The Darkest Hours, a large portion of the book deals with Spiderman trying to coach a basketball team. If Peter Parker was just a regular person, a story about him trying to coach a basketball team would be pretty dull. But he’s not a regular person. He’s Spiderman.

And that makes all the difference.

The reverse is true as well. Even if the situation is so abnormal that your character struggles to handle it, the book can still fall squarely in the “abnormal character” category. The Dresden Files—one of my favorite series and also from Jim Butcher—is an example of such a story. Dresden is a wizard PI who frequently finds himself over his head, fighting forces beyond his abilities. Yet there’s no doubt that these books are all about Dresden. The plot may be intriguing, but it’s Dresden that sells the books.