Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 106

February 14, 2018

How Works of Fiction Can Be Boiled Down to Two Types of Plots

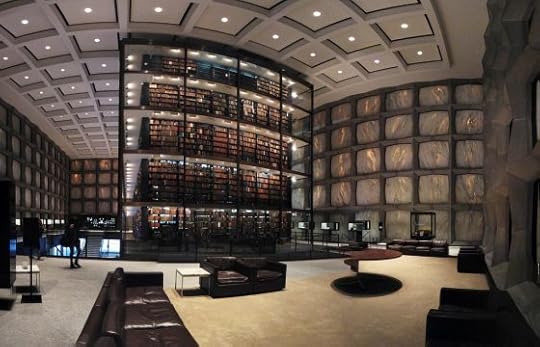

Photo credit: Lauren Manning on VisualHunt.com / CC BY

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Learn more about getting a first-page critique.

First Page

New Haven, October 1952

When I was a boy I used to wake up thinking today could be the day when everything changes. When something miraculous happens. What it would be I couldn’t articulate but I knew it would catapult me from the life I had into the one I was destined for. Everything I wanted would be mine for the asking. Power, fame, riches and glory would fall glittering from the sky like a meteor shower. After thirty-five years of waiting, some part of me still hasn’t given up.

But a day that began with a two-hour commute from New York to New Haven in a rocking overheated carriage that smelt of damp overcoats and inadequately deodorised armpits wasn’t one that augured well for miracles. And now, second in line at the desk fronting Yale University’s Rare Books and Documents Reading Room, I’d begun to think the only miracle coming my way might actually be getting inside the Reading Room. My field of vision was filled by the bearlike back of the patron in front of me. Whoever he was addressing, presumably the librarian, was totally obscured by his line-backer shoulders canted at an angle that suggested a head-on tackle.

“I’m asking you to look again. Is that so hard?” The voice matched the posture, belligerent, boorish.

“I’m sorry sir. I’ve checked and re-checked but I can’t find any record of your request. If you’d just like to step over there …” A pale long-fingered hand emerged from behind his right shoulder and pointed to a desk against the wall, “and fill in another request form, I’ll be happy to …”

“Fuck that,” came the reply and the shoulders straightened. “I’ve got better things to do. I’ve got a dissertation to write lady. If you even know what that is.” With the snort of an aroused bovine, he thrust into reverse, rammed into me and planted the Cuban heel of his right size twelve solidly on my toe.

First Page Critique

In all works of fiction—and probably nonfiction, too—there are essentially two plots, Plot A and Plot B. With Plot A, a character’s status-quo condition of discontent (H. is lonesome) is challenged when opportunity presents itself (H. meets S.). With Plot B, a character’s status-quo condition of contentment (H. loves his quiet evenings of classical music) meets with an obstacle or irritant (rap DJ moves next door).

With most novels and even most stories, Plots A and B do a sort of “opportunity/irritant” tango with each other, with opportunity leading to irritant (the lover met at the coffee shop turns out to be a serial killer), and irritant leading to opportunity, and so on.

On this first page we are treated to a sly blend of Plots A and B, with the nameless first-person protagonist reaching all the way back to 1952 to tell us of a day in his life that started out less-than-auspiciously, first with a damp, “inadequately deodorized” train ride from New York to New Haven, and then with a fellow library patron stepping on his toe. Neither of those events would seem to suggest “opportunity presenting itself,” or Plot A; if anything they plant us firmly in Plot B territory.

But wait: what about that first paragraph—those devoutly-to-be-wished-for miracles falling “glittering like a meteor shower” from the sky? Thanks to that opening paragraph, by frontloading our expectations with miracles, or anyway the hope for them, the narrator performs a kind of alchemy whereby smelly armpits and stubbed toes become the stuff of dreams. We know—anyway we’re given good reason to believe—that somehow or other this will turn out to be a “miraculous” day in the narrator’s life. And so before our very eyes Plots A and B are joined in matrimony. Which isn’t to say that they are going to live happily ever after. However strong it may be, our belief in miracles doesn’t extend to them lasting forever. Still, we sense that this rude snorting bear who has injured our narrator’s toe will be important to him and to his story, that he’ll play—if not the lead—a key role in this miracle in the making.

As inciting incidents go, a stubbed toe may seem a paltry event from which to launch a novel. Yet the history of literature is rife with trivial events having epic consequences. Appointment in Samara, John O’Hara’s most famous novel, owes much if not all of its plot to a single fateful act: the moment when Julian English, the protagonist and owner of a used Cadillac dealership, throws a highball in the face of one Harry Reilly, a major investor in his business.

Similarly, were it not for an errant snowball, there would be no Deptford Trilogy, Roberston Davies’ novel sequence set in a fictional Ontario village. Instead of it striking its intended pubescent target, the snowball hits a pregnant woman, sending her into premature labor and precipitating a series of mostly tragic events. That incident opens Fifth Business, the first novel of the trilogy. As with the opening page in question, it too plants us firmly in a particular year:

My lifelong involvement with Mrs. Dempster began at 8 o’clock p.m. on the 27th of December, 1908, at which time I was ten years and seven months old.

More typically, stories whose openings catapult us into the past are apt to land us at the brink of a momentous event. From Endless Love, by Scott Spencer:

When I was seventeen and in full obedience to my heart’s most urgent commands, I stepped far from the pathway of normal life and in a moment’s time ruined everything I loved—I loved so deeply, and when the love was interrupted, when the incorporeal body of love shrank back in terror and my own body was locked away, it was hard for others to believe that a life so new could suffer so irrevocably. But now, years have passed and the night of August 12, 1967, still divides my life.

Apart from being well strategized, the opening page under scrutiny is also well-written. From its yearning first paragraph through those odoriferous commuter armpits through its rendering of the bear-like, boorish, toe-stomping library patron, it invests us vividly in its narrator’s world. That the Rare Books bear metamorphoses into a linebacker and subsequently into a bovine we might take issue with, but we would be nitpicking. This is a strong opening and I for one would keep reading.

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.)

February 7, 2018

Avoid Nagging False Suspense Questions in Your Story Opening

Photo credit: aluedt on Visualhunt.com / CC BY-NC-SA

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Learn more about getting a first-page critique.

First Page

August, 2006

Henry winced and lowered his hands like a conductor shushing the strings.

“You’re talking too loud.”

Olivia adjusted the volume and continued to talk; it didn’t really matter what about, most likely a new poem, or a story she was working on, something she’d read in the paper that got her blood boiling; or maybe a juicy bit of gossip she thought he’d appreciate.

She knew she should have stopped after the wincing, definitely after the shushing. But she hoped that if she told the story just right, he would laugh, see the irony, share her outrage or amusement. As always, she hoped this time would be different; that something other than pathology would engage him.

Olivia had been told by experts to bury this hope, that Henry would never enjoy the give and take of conversation again, even though he was quite talkative himself, but this felt too much like a death. She allowed herself to be sucked in, say too much. She did her best to speak in simple sentences, to keep herself from spinning the stories he once cherished, the sort of thing the rehab people routinely told families to avoid. She resented the notion that a successful patient was one whose partner suppressed her personality for the good of the other.

“Calm down,” he said, glaring at her.

“I am calm,” she said, “just animated.”

“You do that to torture me.”

“My talking is torture to you?”

“You know it is.”

“Why don’t I just control my heartbeat.”

She hadn’t meant to snap at him; she never did. It wasn’t his fault.

Still.

As long as she could separate Henry from the angry stranger inhabiting him at times like this, she was okay. Brain injury didn’t give a damn that it was a summer day and she wanted to enjoy a walk with her husband, hold hands; maybe stop somewhere nice for lunch, preferably al fresco. Twenty-two years had taught her that. It didn’t leap out of bed and bound into conversation, especially with a wife who’d been up for hours, a writer who lived to tell stories …

First Page Critique

This novel opening presents us with a man and a woman bickering. The man’s name is Henry, the woman Olivia. Although eventually we learn that they are husband and wife, for the better part of this first page their relationship is mysterious, nor do we know in what setting their bickering occurs. Indoors, outdoors? At a restaurant? In their living or bedroom? What we do soon come to realize is that Olivia, whose perspective we share, is frustrated by her inability to converse as she used to with her husband, who—we also discover—has suffered brain damage.

Among a novelist’s chief challenges is that of determining what information to supply when and where: how to balance the desire to arouse suspense with the need to prevent confusion. In this opening the balance tips toward confusion. The nature of the relationship, the setting, even the precise subject of the conversation (something to do with Olivia’s writing) are withheld from us, as is the cause of Henry’s disability, how long he has been ill, and how long he and Olivia have been together.

Our ability to invest emotionally in the given scene, to care about these people, depends on our being supplied with at least some of that context. Otherwise we’re left with a couple of indeterminate conjugal status bickering in a vacuum owing largely to the husband’s unspecified mental condition.

What information to supply, and when to supply it: It’s a question not of plot, but of structure. Often as authors we know our plot; we’ve got all the causal-relation puzzle pieces. We just aren’t sure how to put them together, in what order. Supply too much information too soon, and you destroy suspense. Supply too little and you create false suspense, otherwise known as confusion.

To put to rest some of the nagging false suspense questions raised by the given opening, and establish the necessary context for it, would it not make sense to enter this story earlier, with the inciting incident, i.e. the event that resulted in the circumstance at the story’s center—namely, the incident or accident that caused Henry’s brain damage? Whether Henry’s affliction was caused by a tumor, a stroke, a car or sporting accident, or something falling from the sky, doesn’t matter. What matters is that we know what happened and aren’t made to “guess” when that “guessing” has nothing to do with the relationship under scrutiny. As openings go, it would also be more dramatic.

That’s the strategy taken by Ann Packer in The Dive From Clausen’s Pier, her bestseller about a woman’s conflicted sense of responsibility toward her fiancée after he breaks his neck and becomes paralyzed as a result of diving off the titular pier into a too-shallow reservoir. Packer’s novel begins, “When something terrible happens to someone else, people often use the word ‘unbearable.’” Though the accident itself is alluded to rather than dramatized, by the end of the first page Michael is comatose in a hospital bed: the inciting incident has been supplied to us.

Tom McCarthy’s Remainder likewise begins with an accident—indeed, one that alters his first-person protagonist’s brain. It begins:

About the accident itself I can say very little. Almost nothing. It involved something falling from the sky. Technology. Parts, bits. That’s it, really: all I can divulge. Not much, I know.

Though skimpy on details (excusably if conveniently, since the protagonist’s memory was affected), we have all the context necessary to proceed.

Another celebrated novel that open with memory and an accident is Stephen King’s Misery.

Memory was slow to return. At first there was only pain. The pain was total, everywhere, so that there was no room for memory.

Here, too, at first the accident that delivers author Paul Sheldon into the guest room (and the clutches) of a pathological fan is merely alluded to; we learn of the car accident only as Paul remembers it, through a fog of pain. If we’re confused, it’s Paul’s confusion that we share. The suspense is organic: it isn’t false; it’s real. King gives us everything we need to inhabit the moment of that opening scene.

Ian McEwan’s Enduring Love presents us with another writer (of science) whose emotional equilibrium is shattered by an accident—in this case, a stranger’s death in a freak hot-air balloon accident.

The beginning is simple to mark. We were in sunlight under a turkey oak, partly protected from a strong, gusty wind. I was kneeling on the grass with a corkscrew in my hand, and Clarissa was passing me the bottle—a 1987 Daumas Gassac. This was the moment, this was the pinprick on the time map: I was stretching out my hand, and as the cool neck and the black foil touched my palm, we heard a man’s shout. We turned to look across the field and saw the danger. Next thing, I was running toward it.

Though not a work of fiction, Floyd Skloot’s In the Shadow of Memory recounts his experience of disability as the result of brain damage caused by a virus. The author wastes little time getting to his “inciting incident.” Skloot’s memoir opens thus:

I used to be able to think. My brain’s circuits were all connected and I had spark, a quickness of mind that let me function well in the world. I could reason and total up numbers; I could find the right word, could hold a thought in mind, match faces with names, converse coherently in crowded hallways, learn new tasks. I had a memory and an intuition that I could trust.

All that changed when I contracted the virus that targeted my brain. More than a decade later, most of the damage is hidden.

Here, the author takes a less dramatic (scene oriented) approach, with the POV character confronting us directly, through exposition, with his situation. I can imagine a similar opening for the novel-in-question. But I can also imagine one in which, one way or another, we experience the cause of Henry’s brain injury. It might be a brief prologue or a new first chapter, one that sets up the given opening wherein we re-enter Henry and Olivia’s marriage however many months or years following the event.

Here, the author takes a less dramatic (scene oriented) approach, with the POV character confronting us directly, through exposition, with his situation. I can imagine a similar opening for the novel-in-question. But I can also imagine one in which, one way or another, we experience the cause of Henry’s brain injury. It might be a brief prologue or a new first chapter, one that sets up the given opening wherein we re-enter Henry and Olivia’s marriage however many months or years following the event.

However different, with each of the above examples, directly or indirectly, via summary or scene, the novelist gives us the inciting incident, the event that caused the conditions that set the plot in motion, thereby framing the question[s] that, presumably, the novel will go on to explore. And as Chekov said, the fiction writer’s job isn’t to give answers, but to frame the questions correctly.

February 6, 2018

Launching Your Second Book and Beyond: 4 Questions to Ask

Photo credit: Leonorah Beverly on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-SA

Note from Jane: Today’s guest post is by novelist Andrea Dunlop (@andrea_dunlop), formerly a publicist at Doubleday.

There is so much publishing and marketing advice for debut authors since they don’t know much—if anything—about the process on their first go round. But for most authors—particularly novelists whose work is not necessarily attached to specific moment in time—book marketing is a long game that involves building an audience and a brand over the course of many books.

This week I launch my second novel, She Regrets Nothing, almost two years after my debut. Given that I’d worked in book publishing for eleven years before Losing the Light was published, I knew more than most authors going in, but I’ve learned so much in the two years since! Here are four questions to consider between book launches that will help you maximize your long-term marketing efforts.

1. Who are you core audiences?

Before your debut novel releases, you spend a lot of time thinking about who the audience might be, but once it’s been on-sale for a while you have more information to work with about who they actually are.

Which readers did you hear from?

What did they gravitate towards?

Which other books did they buy?

Like a politician playing to their base, your marketing efforts should always consider your core audiences. Unless you are writing for a very specific niche, your audience probably includes crossovers from different groups. For example, folks who bought my book were primarily female and read a mix of literary and upmarket women’s fiction, domestic thrillers, as well as some new adult fiction and contemporary romance. One of the best reasons to be on social media as an author is because it allows you to see and connect with your audience, giving you real time insight with which to tailor your marketing efforts.

2. What’s new about this book?

2. What’s new about this book?Of course you’ll want to go back to anyone who loved your first book, but to grow your audience you need to either reach more of the same type of readers, or reach new readers. Consider what elements your second book has that your first book didn’t.

My novels have plenty in common— female protagonists, coming-of-age elements, a strong sense of place, disastrous romantic entanglements—but identifying what was new about She Regrets Nothing helped me and my marketing team figure out how this book could reach a wider audience than the first. My second novel is the story of a young woman who discovers a wealthy family that’s been kept from her and decamps to New York to join them. Right away the book started garnering comparisons to Gossip Girl, a show that’s endured as a cultural touchstone of New York City (and which I happen to love) and Edith Wharton, who wrote so beautifully about social class in New York. There are also darker, edgier elements to my second novel that have sparked conversations about sexual dynamics, class, and wealth that the first one didn’t.

3. What worked well for your first book launch? What didn’t?

Before you publish their first book, your marketing plans are mostly speculative. But once you’re a year or two in, you’ve seen which efforts were successful in terms of generating publicity, boosting your social media engagement, and converting into sales—in other words, what worked for you and what didn’t. I threw many different tactics at my first book’s launch, meaning that at this point, I can double down on the former and abandon the latter.

Before you publish their first book, your marketing plans are mostly speculative. But once you’re a year or two in, you’ve seen which efforts were successful in terms of generating publicity, boosting your social media engagement, and converting into sales—in other words, what worked for you and what didn’t. I threw many different tactics at my first book’s launch, meaning that at this point, I can double down on the former and abandon the latter.

I hired an outside publicity firm—Booksparks—to handle the PR for my first book and since they did a stellar job, I hired them for the second book. Because they knew me and my work already they’ve been able to get significantly more attention for my second book.

A counter example: for the first book, I spent a lot of time trying to get Amazon customer reviews, and while this can certainly help with a book’s visibility and sales, for me the cost-benefit of the outreach wasn’t worth it. Now that I know that, I can take it off my to-do list.

4. How can you fine tune your social media strategy?

Social media marketing takes a long time to pay off. If you’re a neophyte, it takes a while to learn how to use the various platforms well, understand their audiences, and feel comfortable enough to generate good content. Many novelists only get serious about social media when a book launch is imminent, meaning that social media might not have been a major factor in your first launch because your platform wasn’t that big. And that’s okay! That time between books is a great time to get your sea legs on social. Once you have a better idea of who your audience is, you’ll have a better idea of how to find and communicate with them.

I wasn’t hugely into Instagram before my first launch, but Bookstagrammers such as Book Baristas and Swept Away By Books became some of my first evangelists and really helped my work find its initial readers. After experimenting with the Instagram a bit more, I discovered I really liked using it, which is always a key component to being effective on a given platform. I also experimented with some new platforms between books, such YouTube, which I abandoned once I discovered just how work intensive it is to create great videos (hats off to the YouTubers!).

When a book launch isn’t imminent, it’s easier to approach social media with a spirit of experimentation, creativity, and fun, and to freely abandon what isn’t working for you. Much of the social media overwhelm I see comes from the idea that you need to be on all the platforms all the time—something even most large corporations don’t de especially well. Find one or two you love and focus on those.

Book launches are intense and can feel very high stakes, so use the time between them to take a step back and consider how to build a career over many years, and many books, to come.

Now it’s your turn: What did you learn between book launches? How have you adjusted your strategy?

February 5, 2018

Hedge Words and Inflation Words: Prune Them From Your Writing

Today’s guest post is by editor Jessi Rita Hoffman (@JRHwords).

As writers, we all know wordiness is something to avoid: never say in ten words what you can say in four. But while we get that in theory, it’s often hard, in practice, to produce tight writing. We look at the sentences on the page, suspecting they are verbose, but don’t know what to change or to eliminate. Learning that is part of the art and craft of writing, of course, and no one blog post can identify all the secrets. But as a book editor who sees lots of writers make many identical mistakes, I’d like to highlight two common writing flaws that clutter the manuscripts of many aspiring authors. I call these culprits “hedge words” and “inflation words.”

Inflation Words: The Problem

Inflation words are intensifiers a writer adds to a sentence in an effort to make something he wrote sound punchier. Very, extremely, highly, truly, literally, precisely, key, and totally are examples of inflation words. The author hopes that by using them, the point she is making will carry more weight, or have more intensity, but the opposite usually results. It’s true that used sparingly, a well-placed intensifier can add flavor, like a dash of salt on one’s food. But when paragraphs are laden with intensifiers, word inflation results. Everything said is so overemphasized that readers become desensitized. You’re shouting so loud that nobody can hear. You’ve spiced the soup so heavily that no one knows if it’s turkey noodle or beef barley under there. The boy has called, “Wolf!” too often, and no one is listening anymore.

Some aspiring authors do the same thing with italics and bolding that others do with inflation words: they overuse them to the point where, when they really want to emphasize something, there’s no way to make it stand out (because everything has been made to stand out). That’s when some writers, in frustration, add underlining to the mix, or all capital letters, or (God forbid) an increase in font size, and soon the manuscript has the visual appearance of a sign or a flier. Or maybe it looks like something a middle-schooler wrote, complete with !!! or !?! at the end of the sentences. Uh-oh, not good!

Inflation Words: The Cure

Instead of trying to prop up weak writing with inflation words or heavy formatting tricks, achieve emphasis in a controlled and tasteful way by selecting the single, precise word that perfectly conveys the flavor you intend to express. For example, replace very confidently with boldly. Replace extremely clever with genius. You don’t need to add an intensifier if the word you select in the first place has the intensity you’re looking for.

Alternatively, sometimes emphasis is better achieved by understatement—by dressing the writing down and making it less blustering. Very important to note becomes, simply, the words you want the reader to note, without the bombastic prelude.

Hedge Words: The Problem

On the other end of the inflation/deflation spectrum, we have authors who prefer to use hedge words: words that deflate the power of the writing by qualifying or limiting other words in the vicinity. These are the hesitant writers, who feel shy about making their points boldly. They are apt to couch their sentences in apologetic words like: generally, more or less, relatively, seems to, on average, potentially, and usually. This, of course, weakens the power of the point they are making, because it sounds to readers like the writer himself isn’t convinced of the truth of what he’s saying.

Hedge words show up more in nonfiction than in fiction, but sometimes even fiction writers over-qualify what they are saying. If hedge words are allowed to proliferate in descriptive writing, they weaken the power of the image the author intends to create.

It’s not that these limiting words are intrinsically “bad”—hedge words certainly have their place, particularly in mathematical and scientific writing. It’s also fine to use them in ordinary prose so long as you do it occasionally and when qualification is needed for accuracy. But if you notice limiting qualifiers sprinkled liberally across all of your paragraphs, you suffer from the malady of being a hedge-words writer.

Hedge Words: The Cure

The cure for deflationary writing is to relax and have more faith in your readers. They know when you write “a thousand soldiers came over the hill” that you mean more or less a thousand. They know when you write that Marilyn rises on weekends after the sun comes up that you mean she does this generally. Those qualifiers (more or less and generally) are understood without being explicitly stated. If you do include them, it may sound like a bigger deal than you meant. We think you’re implying some soldiers perhaps have gone AWOL and that Marilyn is erratic in her sleeping habits. If you’re a hedge-word enthusiast, take a breath, be bold, and trust your readers’ intelligence.

Taking Inventory

Look at some samples of your own writing, and see if inflation words or hedge words frequently appear there. If they do, that awareness alone will help you start to catch yourself. I know, for instance, that I tend to err in the direction of word inflation. I had to delete really, truly, and highly several times from this post. But because I’m sensitized to my personal tendency to overemphasize, I’m able to catch myself and remove that flaw from my writing.

(Confession: I did allow myself one well-placed really in this article—did you catch it?—even though it’s an inflation word. Remember: it’s perfectly fine to use both inflation words and hedge words so long as you do so judiciously and rarely. Like germs that are always with us, inflation words and hedge words only become a problem if they multiply.)

Below is a list I’ve compiled of common hedge words and inflation words. Can you think of any I missed?

Common Inflation Words

Very

Highly

Extremely

Literally

Truly

Really

Totally

Greatly

Key

Immediately

Suddenly

Precisely

Absolutely

Intrinsically

Very important to note

Specific key concept

Common Hedge Words

Usually

Generally

Relatively

Almost

At least

Nearly

Roughly

Typically

Potentially

Ultimately

Around

Approximately

Seems to

For the most part

More or less

On average

Nearly

In the neighborhood of

Upwards of

If you found this discussion helpful, you might enjoy another article I wrote about a related bad writing habit: Two Stammer Verbs to Avoid in Your Fiction.

February 2, 2018

You Can’t Get to “Once Upon a Time” Without “What If?”

Photo credit: yewenyi on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC

Lately, I’ve been reading Thomas Merton’s Confessions of a Guilty Bystander (thank you, Ed!), which was first published in 1968 but remains as relevant as ever on the 50th anniversary of its publication. Here’s one of the first passages I underlined, from Merton’s introduction:

I do not have clear answers to current questions. I do have questions, and, as a matter of fact, I think a man is known better by his questions than by his answers. To make known one’s questions is, no doubt, to come out in the open oneself.

This quote came to mind as I recently read Danielle Lazarin’s essay in the latest Glimmer Train bulletin, Question Everything. She discuses her use of writing notebooks, where she tops and ends pages with questions. She writes:

At every stage of my work, questions are my most essential writing tools. I use them to move through to the other side of murky. It’s only by stepping into that unknown and uncomfortable space repeatedly during my process that I can become more deliberate in the story I’m telling.

Also this month from Glimmer Train:

Writing Archival Fiction by Thomas Fox Averill

On Rejection by Aline Ohanesian

February 1, 2018

The Risks and Rewards of Bringing Your Spouse or Partner Into Your Business

Today’s guest post is adapted from the book Start Love Repeat: How to Stay in Love with Your Entrepreneur in a Crazy Start-up World by Dorcas Cheng-Tozun (@dorcas_ct) Copyright (c) Dorcas Cheng-Tozun by Center Street. Reprinted with permission of Hachette Book Group, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

Note from Jane: Dorcas’s book is addressed to the partners or spouses of those who are undertaking an entrepreneurial lifestyle—such as authors! I’m excerpting it here because I’m meeting more and more writers who are drawing their loved ones into their business life, whether by necessity or choice. This specific excerpt is drawn from the book chapter “Getting Involved—Or Not.”

When my husband, Ned, was running his children’s music business after college, he had the brilliant idea of promising his customers that every Christmas CD would come with a personalized letter from Santa that was hand signed.

Ned has many talents, but neat handwriting is not one of them. So, for weeks, I would go to his place after work each night and join the assembly line of family members and friends processing the orders. I signed Santa on thousands of letters until my hand cramped up. I occasionally added flourishes, like curls or hearts or stars, to the signature, just to keep it interesting.

Ned did not approve. “You’re making Santa’s signature way too feminine,” he told me, as if he knew what the handwriting of a magical man who lived in the company of elves and flying reindeer should look like. I raised my eyebrows at him—I’m doing all this for free and you’re asking me to do what?—and he wisely backed off.

Chances are that you’ve also helped out with your entrepreneur’s business at some point, whether you were keen to do so or not. In the beginning phases of a new company, there is always too much to do, and never enough free labor to do it. As a result, significant others are often called upon to be involved in some way with the business, even if they are not officially business partners.

That’s what happened to Leah Everson of Minneapolis, Minnesota, when her mechanic husband, Tim, opened an auto shop out of their garage. Since Tim was not particularly business minded, she volunteered to help with the books. “I was helping with invoices, making sure sales were logged, all while trying to find an accountant to help us,” she told me. Their business relationship led to quite a bit of conflict; today Leah realizes that “our conflict came out of trying to work out details we didn’t understand.”

There are some real risks to working together, especially if you are both still learning how to run a business and manage your household through the uncertainty of the start-up existence. If neither one of you is entirely certain what you’re getting into and you’re both figuring things out as you go, it’s likely that you will experience a high degree of stress and anxiety—and end up taking it out on each other.

There are, of course, plenty of couples who work together in a business and enjoy it. The extra level of partnership actually enhances their relationship. The reason these couples make it work seems to boil down to the issue of control. Can the partner who is the entrepreneur fully trust her spouse to fulfill his responsibilities in the way he sees fit? Or, if both partners are company founders, can each commit to allowing the other to be fully empowered in his or her area of responsibility? Significant others who feel respected and empowered, and who are given roles that match well with their interests and skills, tend to be able to stick with the business longer.

Unfortunately, most couples don’t know how they’ll respond to one another in such a situation until they try it. Working together, even if it’s with the best of intentions and the most hopeful of expectations, will likely create additional tension in your relationship. If you and your significant other already wrestle over control and decision-making in other areas of your life, you may want to approach the idea of working together with an abundance of caution. That being said, if you have confidence in the resiliency of your relationship and are genuinely interested in supporting your beloved’s venture, there is plenty to be gained from the experience.

Up until I started working full-time for Ned and d.light, I had been content to assist Ned’s business on an ad hoc basis, leaving a clear demarcation between his career and mine. The separation was practical as much as it was emotionally fortifying. I could bring in a steady income, albeit a pathetically small one, and I could retain something that was wholly mine, untouched by the ever-increasing reach of d.light.

But when we relocated to China, I had few career options. Ned was strangely excited. “You should work for d.light,” he encouraged me. “We really need the help. You could make a big difference. And it’d be fun to work together.”

Despite my many concerns about having my husband as my boss, working with Ned was one of my favorite parts of our otherwise challenging time in China. Ned and I were partners in the fullest sense of the word, relying on each other in every aspect of our lives. We underwent what felt like an accelerated marriage track, learning far more about each other and how we could best support one another in two years than many couples do in ten. We experienced a deep level of bonding that has remained with us ever since, and for which I am deeply grateful.

But I have never returned to working for d.light full-time since we left China. Now that we have a young child, I don’t think it would even be possible for both Ned and me to keep up with the demands of the company. I am still involved, stepping in occasionally to help with a project or to provide guidance to a new employee taking on some of my old responsibilities. However, my most prominent role in d.light today is simply as supporter-in-chief, providing affirmation, encouragement, and advice whenever Ned needs it.

Working together with your spouse can be a gloriously rich experience. But it also makes your marriage far more complex. When both of you are working on the same business, the issues that every couple wrestles with—such as power, communication, conflict resolution, and boundaries—seem to come center stage with greater urgency and higher stakes. If you’re not able to work through these issues together, not only will your relationship suffer, but so could the business and everyone it touches, including employees, business partners, and customers. That’s why co-preneurial couples, more than any other type of couple I’ve interviewed, tend to have particularly detailed and formal agreements on how they interact with one another. Some specific strategies I’ve heard include:

“I am the majority shareholder with 51 percent; my spouse has 49 percent. This helps us make decisions for the business when we can’t reach a consensus. The marriage is equal but the business can’t be.”

“We don’t discuss work issues when we’re in our pajamas. We interact as colleagues only when we’re in our work clothes.”

“We have a meeting every Sunday night to do a detailed review of our schedules for the upcoming week.”

“When we finish our work for the day, we come out of our home offices, physically close the doors, and focus on just being spouses.”

“If we want to take a vacation, we set a budget, scope out our to-do lists to prepare for it, and make sure we’re organizing our lives to make it happen.”

“If I have a work question for my spouse, I will email him about it, even if he’s sitting just a few feet away from me.”

“I take care of the business side, my spouse does the technology side. We give each other full authority in those areas and don’t interfere at all with one another’s work.”

“We regularly do big outings with our daughter for the distraction and to practice doing normal family stuff.”

“When we have fights, we have to be able to forgive one another wholeheartedly and give each other a clean slate.”

“We do one weeklong getaway each year as a retreat to reconnect with each other.”

As fastidious as some of these agreements may sound, having such practices in communication, decision-making, and boundary-setting can significantly help a couple navigate through the stickiness of being both spouses and colleagues. Even then, there is no magic formula to ensure that a couple will work together well. Some amount of trial and error is unavoidable in learning how to be business partners—or in discovering that the two of you just aren’t meant to be professional colleagues.

As fastidious as some of these agreements may sound, having such practices in communication, decision-making, and boundary-setting can significantly help a couple navigate through the stickiness of being both spouses and colleagues. Even then, there is no magic formula to ensure that a couple will work together well. Some amount of trial and error is unavoidable in learning how to be business partners—or in discovering that the two of you just aren’t meant to be professional colleagues.

If you enjoyed this post, take a look at Start Love Repeat.

Now it’s your turn: Have family members become business partners in your writing career? What have you learned?

January 30, 2018

The Essential First Step for New Authors: Book Reviews, Not Sales

Photo credit: B Tal on Visualhunt.com / CC BY-NC

Today’s guest post is by David Wogahn (@wogahn) of Author Imprints and author of The Book Reviewer Yellow Pages.

You know how good your work is. You created it. You lived with it through the phases of publication gestation: idea, brainstorming, outline, research, writing, and rewriting. You have improved, enhanced, and polished your work to a degree you didn’t think possible. You believe it’s perfect.

Alas, your opinion is not the most important at this point in your publishing cycle. You need third-party confirmation to attract readers. You need (positive) independent assessment to convince readers to spend money and time—money AND time.

British sociologist John Thompson, an expert in the influence of the media in the formation of modern societies, identifies five resources or capital that are essential for publishing success in his book titled Merchants of Culture: The Publishing Business in the Twenty-First Century. Thompson writes that besides cash, the most important resource is symbolic capital, which he defines as “the accumulated prestige and status associated with the publishing house.”

Book reviews build symbolic capital

New authors—certainly self-published authors—have no symbolic capital. They are not (yet) known for producing quality books that seduce readers to the degree that they are willing to part with some of their disposable income, not to mention time. Is it possible for self-publishing authors to create symbolic capital? Absolutely yes, and many have.

In today’s increasing online world of book shopping, I argue it is book reviews that build symbolic capital. A shopper evaluating a book for purchase when it has no, or few, reviews is like the hungry guest walking into an empty restaurant. How good can this place be if no one is here eating?

Even traditional publishers with symbolic capital “in the bank” must actively solicit book reviews so their authors’ books can succeed in our unimaginably crowded retail market.

Where should you begin?

The key to a successful book launch is prospecting for reviews in safer territories first, and expanding in stages. The goal is to have some number of reviews in place—the book’s social proof and symbolic capital—before investing in general promotions. How many? As many as you can but 10 is a good goal.

The key to a successful book launch is prospecting for reviews in safer territories first, and expanding in stages. The goal is to have some number of reviews in place—the book’s social proof and symbolic capital—before investing in general promotions. How many? As many as you can but 10 is a good goal.

Let’s walk through the four territories illustrated in The Book Review Journey.

Loyal Fans. These are people that know, like, and trust you. They are also the ones most likely to leave a review. For an established author, they are readers who reviewed previous books. For new authors, the circle can be very small indeed—it depends on the depth of their network, and the extent to which that network is familiar with the author’s writing. But be careful—approaching close contacts to review your book carries three risks.

Amazon is good at spotting reviews from friends and family and may reject the review (or worse) if it is from a known family member.

If your Loyal Fan network hasn’t left reviews for other books, their sole review of your book will carry little weight with shoppers who happen to look at who wrote the review.

The third risk relates to number two. Some Loyal Fans go overboard and review the author rather than the book, or gush without including any meaningful feedback.

Addressable Audience. I define this group as those who have given you permission to contact them, in some way related to your writing or the subject matter of your book. This last part is important. It isn’t enough that someone gave you their email address, liked your page/profile, or follows you. If you run a dry cleaning business, and decide to tell your mailing list about your new romance novel, the level of engagement with this list will be proportional to their awareness of you as a romance author.

The purpose of having an Addressable Audience is so you can notify them when you do something they might find interesting, which is presumably the reason why they gave you permission to contact them in the first place.

Addressable Audience members become Loyal Fans when they buy something, and/or act to tell others about it.

Chosen Reviewers. The first two stages take time to build and nurture, but it’s friendly territory and engaging them to review your book should come naturally. Proactively seeking reviewers is different. There are many options and a successful strategy takes time, and potentially money, to execute.

The most important guidance is to seek reviewers who enjoy books like yours. These readers are far more likely to respond favorably to an invitation to invest the time to read your book and offer an informed view.

I call them Chosen Reviewers because you still have some measure of control over whom you approach.

Reviewers of comparable books. Look up books similar to yours on Amazon, Goodreads, and other retailers, and contact those who have left reviews about reviewing your book. Or use a service to help you harvest possible reviewers to approach.

Book bloggers are an excellent source of potential reviews. True, they must be willing and available, and even identifying them requires work, but the advantages are two-fold: (1) you’ll get a review, often posted in multiple places and (2) your book receives promotion when the blogger shares their review on their website and via social media.

Blog tour organizers are a third source. They help authors organize review tours—a type of tour where getting book reviews is the objective of the blog tour (as opposed to promotional tours). Some even offer co-op style arrangements for submitting books to a reviewer network such as NetGalley.

What about paid reviews?

I believe that it is too simplistic to say that “spending money on reviews” is bad, or unethical. There are several perfectly legitimate and ethical instances where spending money is necessary, or advantageous, even when pursuing reviews from reviewers associated with the above three categories. And review services such as Kirkus are an accepted and trusted resource by many in the book trade.

Rather than make a blanket statement, I say that it depends on the book, the author, and the marketing plans for the book, not to mention your budget. Also consider what’s important to your primary audience of readers.

Even if you can afford to pay hundreds of dollars for Kirkus to review your book about hiking in Colorado, it’s doubtful your readers will care, and concentrating on Amazon customer reviews is probably just the ticket for your self-published romance book.

For a more in-depth discussion of this topic see Jane’s post, Are Paid Book Reviews Worth It? Be sure to scroll down and read the comments, especially the exchange with one of the paid book review companies. It’s important reading.

The Public. Unfortunately, this is where many authors begin—the uncharted wilderness. Cold and unforgiving, we’re at the mercy of someone who does not know us or does not pay much attention to whether our book is a fit for their reading interests. And that’s if they even bother to take a chance since there are few or no reviews. We’re living on hope, and dying from despair.

The alternative is patience and prioritizing reviews before promotions

The point is that we do have control. Instead of a straight-to-the-public Hail Mary our intrepid explorer has blazed a path through the first three territories of their review journey, in the order outlined above. They have several—perhaps ten or more—reviews to show the public before investing in marketing programs to drive readers to their book.

Then when the general reader arrives they see social proof; the book has symbolic capital.

You cannot control what reviewers say, but approaching those most likely to enjoy your book will set the tone for reviews and sales to follow.

Let us know in the comments: How have you approached getting reviews for your books? Do you have a formula or strategy that’s worked?

January 29, 2018

Can You (Should You) Typeset Your Own Book?

Photo credit: iandolphin24 on VisualHunt.com / CC BY-NC-ND

Today’s guest post is by Arielle Contreras of Reedsy.

If people judge books by their covers, then typesetting is the difference between a brief or a lasting impression. The cover may grab a reader’s eye, but what the reader sees when they crack open the book is what will hold their attention.

What’s more, it will do so without the reader being any wiser. Or at least, that’s what good interior design is meant to do. As world-famous typographer Erik Spiekerman says, “Design works not because people understand or even appreciate it, but because it works subliminally.”

Indie authors want control throughout the writing and publishing process. They also, typically, want to keep the process as cost-friendly as possible because going the self-publishing route means going without the marketing, editorial, design, and other teams that come as part of the traditional publishing package.

However, since typesetting can be a largely technical art, are self-publishing authors able to do it themselves? Thanks to the growing number of adept typesetting softwares out there, the answer is yes. Whether or not they should DIY is a different question, and one with an answer that depends on the type of book you’re publishing.

Why is typesetting important?

Publishing a book with grammatical errors or typos is guaranteed to leave your audience with a bad impression. Likewise, a book with design flaws will contribute to a negative reading experience. It distracts the reader and pulls them away from the content by interrupting the pace, tone, and atmosphere. Therefore, the goal of typesetting is to create a seamless flow of words that allows a person to read without obstruction. Think of it as a phone call between an author and a reader: with typesetting, the connection is clear and the message gets through. Without typesetting, the call experiences static and the author’s voice drops in and out.

Typesetting also involves choosing the relevant font for the content of a book. For instance, you wouldn’t your war memoir to use a chapter header font of Comic Sans (although, apart from your Grade 4 book reports, when is this ever really an appropriate font?). Good typesetting also ensures your margins are not too big, not too small, but just right; eliminates rivers of whitespace; and removes ladders (when there are a number of hyphens in a row). How does typesetting achieve smooth reading? Through technical details, such as removing widows and orphans. Widows occur when the first line of a paragraph is on its own at the bottom of the page; an orphan is when the last line of a paragraph is alone at the top of a page.

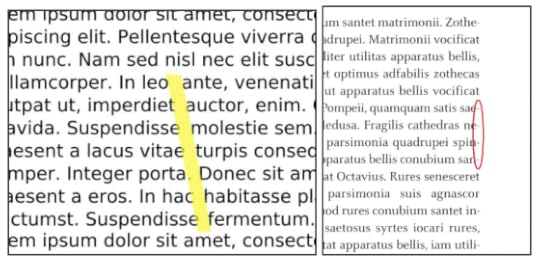

Typesetting faux pas: on the left is a “river of white space” and on the right is a “ladder”

The margins are too big on the left, too small in the middle example, and ideal on the right.

Do-it-yourself (DIY) typesetting software

Not all books require a professional typesetter. Traditional novels generally have straightforward interior designs which can sometimes be handled by the author with one of the many softwares available. A more complex book (children’s picture book, cookbook, photo book, graphic novel, etc.) should be designed by a professional to ensure that all of the visual aspects look clean, appealing, and are appropriate for the content. Here are some of the DIY softwares available for books with both complex and simple interior needs.

For simple, text-driven books (such as a paperback novel)

Reedsy Book Editor (free). Launched in 2016, the Reedsy Book Editor enables self-publishing authors to produce a professional-looking book without hiring a professional designer. It incorporates both the word processing elements of Microsoft Word and the interior formatting capacity of a layout software. The Book Editor requires no design knowledge, provides automatic typesetting, supplies professionally designed templates, and is compatible with most ebook stores and print-on-demand publishers. However, the Reedsy Book Editor does have its limitations in terms of customization. For this reason, it is best suited for fiction and simple nonfiction books.

Vellum ($$). Another easy-to-use typesetting option for indie authors is Vellum—and it’s a popular one, too. Simply import your Word doc file, and you’re off to the races. It offers more customization options than Reedsy’s Book Editor, but again, it’s primarily for simple text books and not for anything image heavy. It has a few different “Book Styles” if you want something unique, and templates for copyright pages, about the author, and other standard front and back matter. Vellum’s one downside is that it’s only for Mac users. It’s free to download and use, but when you’re ready to generate your book, you have to pay.

Draft2Digital (free). Draft2Digital is mainly known as an ebook distribution platform, but they also offer a handy free formatting tool which they revamped in 2017 to offer more customization possibilities. Here’s how it works: You upload your Word manuscript, specify your chapter breaks, and highlight your chapter titles. And then D2D takes it from there: they add a table of contents, custom front and back matter, and ensure it meets the standards of most digital stores. This process is free, and while D2D will then encourage you to use their service to distribute your ebook, you can also just take the files and leave.

For complex books (such as an illustration-heavy book)

Adobe InDesign ($$). Adobe InDesign is what traditional publishers and professional typesetters or designers use. It’s the most powerful typesetting software of all, with the most features, but nearly impossible to use without proper training.

Bookwright by Blurb (free). Intended for books with strong visual components. You can customize the layout of each page, easily adding text and photo boxes to your liking. There are also several templates available for specific genres. Bookwright is a good choice if you want to publish an illustrated or photo book but don’t have the budget for a proper designer.

If you are planning to self-publish your book, you ought to be the first one to invest in it, whether that’s an investment of time to learn a new software or an investment of money to pay for one. Formatting your own book as an independent author clearly comes with a smaller price tag than hiring a professional. However, as professional Reedsy designer Kevin Kane notes, “Investing in the purposeful, careful, and practiced skills of a book designer is probably the safest investment you will ever make.”

Tips for hiring a professional typesetter

The search for the right professional to typeset your book can be a little bit like finding the right editor—you want someone who understands your work, who won’t try and change the core of what your book is about about, but who will elevate it to its fullest potential. Here are a few tips for finding the right typesetter.

Start by looking for designers who have experience in your specific genre. Their experience will not only help them better understand your book and its requirements, it will also allow them to make your book stand out as they will have market-specific knowledge.

Communicate. The beneficial effect that typesetting will have on your words will increase with a good relationship between author and designer. “Ask questions about the designer’s process, and about the decisions they make while designing a book. If you find a designer who doesn’t have thorough answers to your questions about book design, you’ve probably hired the wrong designer,” suggests Kevin Kane.

Familiarize yourself with their portfolio. The simplest way to determine how a designer will improve your book is by understanding their approach to typesetting and whether you believe this approach will translate well to your work.

For aesthetic and practical reasons, proficient typesetting ensures that the interior design of a book is tailored to what the author is saying. It elevates the artistic aspect of your book and can help bring the words to life. Therefore, deciding whether to hire a professional typesetter or to go the DIY route is a personal decision that should be influenced mainly by the kind of book you are publishing—and the message you hope to convey.

January 25, 2018

4 Affordable Ways to Master Book Marketing

Today’s guest post is by Dave Chesson (@DaveChesson) of Kindlepreneur.

Learning the art of book marketing is a pursuit which can often feel like an unending demand on your limited resources. But it’s a craft we must improve over time, as well as keep up-to-date with using newest book tactics. Our book marketing landscape changes, and so we must too.

Keeping up with the latest book marketing trends and learning new tactics can be expensive. Couple this with the growing cost of self-publishing, and it’s important that we be economically shrewd in our endeavors.

Courses are a wonderful way to effectively and efficiently learn how to market our books, but it seems like the price of a course increases every year. Plus, new tactics also pop up, requiring another course to take, like Facebook messenger bots or Amazon ads.

So, how are cash-strapped but talented authors supposed to rise above?

Luckily, there are some effective ways, platforms, and methods for the cost conscientious and time-starved authors out there.

Since you’re here reading one of my personal favorite book marketing blogs, we won’t discuss top writer websites, but we will instead focus on some other methods to help you learn, grow, and improve your book marketing skills, without breaking the bank.

1. Free video content (YouTube channels)

Video is one of the most popular and fastest growing ways to share and acquire information online. Platforms such as YouTube are a great way to learn, and there are several advantages to choosing video as a medium for learning book marketing. These include:

The ability to learn anywhere with your smartphone

The chance to see book marketing actually done

The benefit of the personality and charisma of the teacher

The ability to rewind and listen again to key sections

The ability to increase the speed to 1.25x to learn faster – in case you’re not patient like me

There are a lot of great book marketing channels out there. However, here are some of the channels I constantly check out:

Dale Roberts – Focusing on great how-to and reviews for the book world, Dale consistently creates videos and increases his list of resources by the day.

Emeka Ossai – Like Dale, Emeka is centered on how-to in the self-publishing world and focuses on ways that authors can get more out of less.

Derek Murphy – Excellent at cover design and formatting, Derek also dives into new trends and self-publishing news with his vlog-style channel.

Jenna Moreci – The always funny and talented fiction writer who talks about the craft, writing better fiction books, and even the planning process.

Kristen Martin – Like Jenna, Kristen covers the art of writing, but with a different style. She’ll help you with your writing process and everyday road blocks.

The Creative Penn – One of the smartest and biggest names in self-publishing, Joanna uses some clips from her podcast and offers bite-sized bits of book marketing genius.

2. Book marketing podcasts

With podcasts, you can turn your morning commute or time on the treadmill into valuable book marketing education time. I’ve even listened to favorites of mine while waiting in line to see the doctor.

Podcasts are a great way to hear book marketing explained in the words and voice of the people who do it best. It’s an ideal way to hear in-depth conversations that explore the ins and outs of book marketing topics in more detail than a blog post.

A few ideas for book marketing podcasts you can learn the most useful information on include:

Mark Coker’s Smarter Author Podcast: A newer podcast where Mark Coker, the creator of Smashwords, covers one book marketing lesson with each episode.

The Creative Penn: Joanna Penn brings on top guests to talk about strategies, marketing and their successes. It was one of the first podcasts I ever listened to when I first started.

Sell More Books Show: Bryan Cohen and Jim Kukral are two of the top book marketers out there. Each week, you not only get to hear what’s going on in the publishing world, but also their thoughts on the latest news and recommendations for authors.

Backmatter from Leanpub: One of the best things about podcasts is the opportunity to hear top names in the publishing industry share their insider secrets about what really works.

Self-Publishing Formula: Mark Dawson is one of the biggest names in the world of self-publishing. In his Self-Publishing Formula podcast Mark shares top marketing tactics for authors.

[Note from Jane: Also check out Dave’s podcast, The Book Marketing Show.]

3. Book marketing audiobooks: 2 free downloads

Audiobooks offer many of the same advantages to podcasts. But, unlike podcasts, audiobooks explore topics in a lot more depth and allow you to drill deep in a way which is not possible with a podcast episode.

What many authors don’t know is that you if you sign up for a Audible account, you get two free downloads. Even better is that if you have an Amazon Associate account, you can get a link that if anyone clicks and signs up for a free Audible account, you get paid $5.

Like Jane’s link here — her coffee fund will thank you.

So, if you haven’t already, go ahead and signup for a free trial of Audible and download two book marketing books free, such as:

Your First 1000 Copies by Tim Grahl

Write to Market by Chris Fox

Book Launch by Chandler Bolt

Book Marketing Is Dead by Derek Murphy

Secrets to a Six-Figure Author by Tom Corson-Knowles

Write. Publish. Repeat. By Johnny B. Truant and Sean Platt

4. Discounted or free online courses

Online courses have exploded in popularity in recent years with sites like Udemy, which make online learning accessible to more people than ever before. You may have experienced courses as very expensive, premium options—often marketed via email with slick sales copy. While some premium courses may be worth the investment, there are more affordable options if you want to learn book marketing on a budget.

For example, Udemy runs a sales period where all of their courses are heavily discounted. No matter their original price, the new price is $15 and sometimes even $10. So wait for one of those deals and jump on board.

Even at their regular price, Udemy courses are a lot more affordable than premium options. You can take a course on everything on how to market and publish an ebook, including:

Building a mailing list

Setting up a search engine optimized blog

Social media marketing

Customer relationship management

Facebook advertising

Taking a course allows you to explore a topic in more depth than a typical YouTube video or podcast episode allows, and grants you the freedom to learn on your own schedule.

There are many free, legitimate and full courses out there. I myself created a free course to help authors with Amazon’s book advertisement system, AMS. It’s free and you can learn how to not only set up ads, but watch me create profitable ads for big-name authors, as well as first-time authors. You can check it out here.

Do you agree that these are the best affordable ways to master book marketing? Do you have any other methods that haven’t been included here? Let me and Jane know and we’ll chat in the comments!

January 24, 2018

How to Rock a Free Day Promotion for Your eBook

Today’s guest post is by author K.B. Jensen (@KB_Jensen).

If you are an indie author on Amazon, as part of Amazon’s Kindle Select Program, you can use five free days to promote your ebook in exchange for three months of exclusivity. Many traditional publishers are increasingly doing free promos as well, and the competition is growing with thousands of free ebooks available every day. So how do you stand out?

First, here’s what not to do

While it’s tempting, marketing your free days to family and friends, predominately on Facebook or Twitter, is a bad idea. These are readers who are more likely to pay for your book. Ideally, you should be marketing to new readers who’ve never heard of you before.

I do not recommend doing a free day promotion close to your book’s launch, because you don’t want to poach paid sales from yourself. Friends and family can definitely help spread the word after they’ve read your book, however.

Do not sit back and expect the free downloads to roll in without doing any advertising. I’ve heard from two authors who’ve run free day promotions without advertising, and heard crickets in response.

Don’t wait until the last minute to advertise your free day promotion. I recommend approaching book discovery sites four to six weeks before your promotion, so that you are more likely to get a slot.

Carefully evaluate ebook promotion sites. Be wary of any sites that guarantee downloads or look like possible scams. If its sounds too good to be true, it probably is. You don’t want to get flagged by Amazon for violating their policies.

Do not run a promotion without any reviews on your book. Reach out to your early readers and ask for reviews. It may seem like a catch-22, but readers likely won’t give your book a chance if it has zero reviews, and many book promotion sites won’t pick it up without solid reviews to start.

The Top Ebook Promotion Site

A quick explanation for those new to ebook discovery and promotion sites: basically, readers sign up to receive recommendations for discounted or free ebooks in their favorite genres. The sites then regularly offer recommendations. The best sites curate their lists and offer a limited number of highly rated books.

The king of book discovery sites is Bookbub, and for good reason. The site has more than 10 million book fans on its email lists. It selects only 10 to 20 percent of books that apply for a featured deal; the key to acceptance is having strong reviews and lots of them.

I recently advertised my literary novel, A Storm of Stories, on Bookbub, where it reached #8 in the top 100 free books in the Kindle Store and #1 in free contemporary fiction short stories and literary books with 18,069 downloads on Dec. 30. The ad cost $301 but went straight to my target audience. After the promotion, A Storm of Stories reached #5 on the paid bestseller list for literary short stories. The book had about 18,000 pages read in a week on Kindle Unlimited, as well as a spike in paid sales—not bad considering the book’s genre, literary short stories, and that it was around the New Year’s holiday.

I recently advertised my literary novel, A Storm of Stories, on Bookbub, where it reached #8 in the top 100 free books in the Kindle Store and #1 in free contemporary fiction short stories and literary books with 18,069 downloads on Dec. 30. The ad cost $301 but went straight to my target audience. After the promotion, A Storm of Stories reached #5 on the paid bestseller list for literary short stories. The book had about 18,000 pages read in a week on Kindle Unlimited, as well as a spike in paid sales—not bad considering the book’s genre, literary short stories, and that it was around the New Year’s holiday.

Bookbub provides handy pricing information and subscriber stats. You can also find more information about their submission guidelines on their site.

But what do you do if you don’t have enough reviews to get Bookbub’s attention? There are several other players out there with growing email lists of readers hungry for free books.

Other Places to Promote Your Free Ebook

In November, I ran a smaller book promotion for A Storm of Stories and garnered 3,468 free downloads and more reviews. I saw a modest spike in paid sales and Kindle Unlimited pages read, as well after the promotion was over. Here are some of the sites that were worthwhile for me.

Freebooksy has more than 368,000 registered readers across categories. It has 110,000 subscribers in the literary genre and costs $60 to advertise a literary book, for example. You can also submit for editorial consideration for a free slot. It’s one of the best-looking sites for free ebooks, in my opinion.

Ereader News Today is another one of my preferred sites to promote a free book on with a total of 200,000 subscribers and 135,000 in the literary fiction genre. It cost $40 to advertise a free literary book.

Another one of my favorite sites is the Fussy Librarian. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to promote on the Fussy Librarian, during either of my recent promotions because I wasn’t early enough to book a spot. The Fussy Librarian has 122,000 email subscribers. In the literary fictioncategory specifically, it has 97,118 subscribers and costs $16 to advertise a promotion. It’s one of the best values out there for advertising a free book. As a result, its calendar fills up quickly. The Fussy Librarian is also unique in that readers get to choose not only the genre, but the level of violence or profanity in the books they get suggested.

Some of the smaller players I used

I advertised on Booksends.com and EreaderIQ, which claim to have well over 150,000 active readers together. Booksends has 16,000 readers in the literary category.

I also liked BookRaid, which charges based on clicks, with a maximum of $20. While they politely declined to release subscriber numbers when I contacted them, they did tell me that my book had 450 clicks during my promotion.

EbookSoda cost $15 and has more than 22,000 subscribers, with 4,000 literary subscribers.

Ebook Betty has more than 24,000 subscribers on its email list and had an option to advertise for $18.

Overall, the two recent free promotions boosted my Amazon rankings and visibility, and increased my reviews from 47 with a 4.2 star rating to more than 72 reviews with a 3.9 star rating.

Weeks after the Bookbub promotion, A Storm of Stories was still in the top 100 bestsellers in the literary fiction short stories category on Amazon. Ultimately, stacking promotions can help you hit the bestseller lists for your categories, increase your reviews and help you find new readers.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers