Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 101

June 22, 2018

Character, Writers, and Portrait Photography

Today’s guest post is by author Jeff Shear (@Jeff_Shear).

Philip Roth died on May 22, and I am looking at Irving Penn’s famous portrait of him that appeared in a recent issue of the New Yorker magazine. The photo, shot in 1983, depicts Roth at age 50, a time when many say a writer’s gifts are fully ripened. Penn’s photos of other writers—Joan Didion, Truman Capote, Carson McCullers—are icons.

The Roth image is a character study of an author known for the characters he’d created—the sexually absorbed Alexander Portnoy, the tortured writer Nathan Zuckerman (who leads us through nine books), and Seymour “Swede” Levov, among them, the protagonist of Roth’s Pulitzer Prize–winning American Pastoral.

In many ways, a portrait photographer encounters the same great issue as fiction writers, chiefly, creating and revealing character. So how does does Irving Penn go about telling us the story of Philip Roth, limited by a fraction of time, an image in two dimensions, one background, and whatever hues he can create?

Penn lights Roth in black-and-white, not color, leaving nothing to distract from the author’s unhandsome hard-wrought good looks. He has Roth’s face tilted slightly upward and away into the distance, so that we don’t see him head on but posed in triumph, indomitable, his balding pate, black with curls from temple to temple. The hair looks like—and is meant to look like—nothing less than the laurels bestowed upon a conquerer. In lesser men, before a lesser lens than Penn’s, those same curls might frame the face of Bozo the Clown. Writer beware!

Almost always, Penn tells his stories through tight shots of the face. Roth is rarely pictured by any photographer when smiling. Instead, Penn recognizes Roth’s thin lips, so that they appear sealed, withholding some pent up message. What—rage? intellect? how it all ends? The large, nearly bulbous nose looks almost architectural, structured and bent to shape; it becomes a prow, a bowsprit. And then we notice, just barely, at the bottom edge of the photo, that Roth’s wearing a shirt, probably white; only the collar is visible, so that it could be a towel worn around the neck of a prize fighter fresh from the ring. Wouldn’t Norman Mailer be jealous? In Penn’s treatment of Mailer, Roth’s contemporary, the author’s hands are folded against the face and probably flipping us the bird, and if that isn’t the story of Norman Mailer, the portraitist got it wrong.

In part, character is in the eyes, and, most of all, how the eyes are used. Take the screen goddess of the forties and fifties, Lauren Bacall. In virtually every shot, she’s looking askance, the eyes peering off to one side, on the make, or checking over her shoulder. She’s chic and dangerous. In Penn’s image of Roth, the eyes look far off into the distance, trained on the next higher shelf.

For writers, eye color is an obsessive, almost compulsive, element in character description. I plead guilty. For certain I’ve read about every description possible of green “alluring” eyes. But Penn’s portraits ignore color. An image of the poet Patti Smith by Penn, shows her looking louche, bare shoulder, her eyes stoned and lost and not giving a damn.

It’s worth a note that it’s not just the shape of the eye that matters, or the pupillary distance, or the lashes. The better story emerges though the view taken by the subject. He or she is looking at something, and what the subject sees, or finds important, tells a story all by itself, maybe the whole story. Often, maybe too often, writers describe eyes narrowing, sparkling, or suddenly getting larger. Rarely do we see eyes described by their fixation. What the hell is the character so interested in seeing? How important to story is it to know what the character wants? Most often, someone wants what they’re looking at. Skip the the 50 shades of blue “sparkle.” Better to show the reader the character’s focus; what is it that most attracts their attention and reveals an element of their being?

It might be asked here what the great young portrait photographers of our era are doing. The answer is pretty much the same thing as portraitists like Penn, but more often with color. The great Annie Leibowitz of Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair, and Vogue fame, says that, in school, “I wasn’t taught anything about lighting, and I was only taught about black and white.” She learned color on her own. Yet, when she takes her portrait of the poet and song writer Patti Smith (as does Penn), color is incidental, barely there. Maybe she’s created a moody blue ambience instead of cold purity of black and white. Still, it’s Smith’s cold dead stare and the dark props surrounding her that says “horsemen pass by.”

Today, the portrait is still chiefly about the face, but even with the introduction of color, backgrounds often remain almost incidental. The talented photographer Sue Bryce demonstrates that background is less about information than capturing a “look.” Peter Hurley calls himself a “headshot photographer” and sometimes completely dispenses with backgrounds. Face predominates and serves as its own setting, which is why setting may get in the way of a headshot portrait. And has the depiction of character, the description of face and figure, changed over the decades? Hardly at all. It still must reveal the beating heart of the living breathing person, which is also the writer’s single greatest challenge.

June 21, 2018

The Psychology of Author Marketing

Today’s guest post is by Dave Chesson (@DaveChesson) of Kindlepreneur.

Convincing book shoppers to buy your book is an art form, and not a task.

It’s one thing to know how to setup something technical like an advertisement, an email system, or your book’s sales page on Amazon. However, crafting them so a potential reader will take action is something else.

This was something I honestly struggled with when I first started selling books or working on my websites. I would follow steps presented in tutorials, but would never see the kind of results that others would see.

I was failing at the art of influencing my potential market.

However, a while ago, a friend gave me a book called Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion by Robert Cialdini. He discusses the different principles to the art of influence and how we, as marketers, can create conditions to compel readers to take action.

So, with Robert’s principles in mind, we’ll dive into three that have made the biggest impact, and look at how we can apply these principles to book marketing with specific tactics.

The Law of Reciprocity

Multiple studies have shown that people are geared to want to return a favor. It’s in our nature to feel obligated to take action due to someone else’s request because we don’t want to feel indebted to others.

Therefore, by creating a condition where our target audience feels somewhat like they owe us a simple gesture, we have a higher chance that they will take action upon a clear request. This isn’t about holding something over someone’s head. Instead it’s about making them feel like they want to return the favor. Below are a couple of common tactics to illustrate this.

Offer genuine value to readers on social media

When you understand how you can best serve your readership through your social channels, your engagement will start happening naturally, without the need for desperate pleas. There’s no better example of this than Brian Meeks and his Mastering AMS Ads group. He spends hours every day helping authors and answering their questions. So, it’s no surprise that when his AMS book came out on Amazon, he had an insane amount of buyers and reviews.

Give a priced book for free

Most authors will entice readers to signup for their email list by giving them a book or short story for free. However, if that free book is actually listed with a price of $2.99 or greater elsewhere, an author has not only increased the perceived value of the book, but also proven to the reader that they are giving them value of $2.99+. Readers may not know how much it really costs to produce that book, but the simple $2.99 price tag is all you need to incur the law of reciprocity.

My Favorite Reciprocity Book Tactic

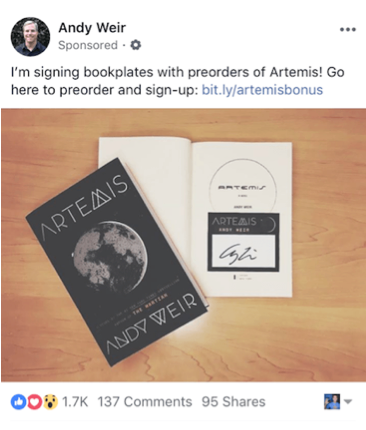

One specific example where an author used the law of reciprocity to an epic level was in Andy Weir’s latest book launch for Artemis. A couple of weeks before the book release, I saw a Facebook ad that said if I pre-ordered a copy of Artemis, and emailed them a copy of the receipt, they’d send me an autographed name plate.

After emailing them my receipt, they now have my email address, and after the book launch, they sent me an email asking if I would leave a review. Just like the law states, I felt obliged to leave a review because of the awesome name plate he shipped to me for free. The best part about this is that his actions were fully compliant with Amazon’s review policy, as you can see explained here.

So, as you craft your Facebook ads, or offer content at your site, think of the law of reciprocity and ways to leverage this to increase your chances of an action being taken by your readers.

Social Proof & Book Validation

We’re always consciously and subconsciously looking for clues of how to behave like others. Seeing that others enjoy something, or have bought something, gives us strength to follow as well. Therefore, if readers see positive indications that other readers like your book, or visit your website, or trust your writing, they are more likely to behave in the same way. Other than reviews, here are other ways you can ethically apply social proof as an author.

Gain best seller status

When you become a best seller in a category on Amazon, your book gets the best seller tag on it. This is a form of social proof that drives people to trust your book more. You can also put it on your website or email signature, but that’s a conversation for another time.

Feature reviews in your editorial review section

If you setup an Amazon Author Central account, you can add reviews that others have made, as well as any authorities you know that can vouch for you. This is powerful if done right, like Jane did on her book The Business of Being a Writer.

Mention awards or recognition

There are many ways authors can find recognition for their books. An example of this is TopSciFiBooks.com which has lists of top perceived books in different subgenres. Imagine the power of claiming that your book is listed as one of the best post-apocalyptic books. Then the next step is to leverage this either in your book description or an editorial review as discussed above.

Liking: If We Like, We Follow and We Buy

This may sound simple, but it’s deceptively powerful. The feeling of “liking” someone can override our logic and other judgmental factors. Have you ever felt a strong sense of liking toward someone or something, and felt very loyal as a result?

But here is where authors get this wrong. Just because someone likes our book doesn’t mean they like us, the author. There are many books that I absolutely love, but I can’t remember the author’s name. Therefore, authors need to engage further and connect in memorable ways.

Craft an author bio that really connects

Your author bio is the one thing that helps you define yourself to your readers. Do not make the mistake of many and treat it like a resume. It’s your one chance to connect with readers and get them to follow you. This can be put on your book, and even on your Amazon Author Page.

Humanize before the review

A tactic that I personally love is that right before I ask for a review at the end of my book, I humanize myself. Sounds silly, but I remind readers that I am an artist who loves writing and I care about what readers say. This helps remind readers of how important that review is, and that I am a human with emotions. You’ll find you’ll not only get more reviews this way, you’ll also get better ones as well.

Put pieces of yourself in your writing

Over 150,000+ people read Kindlepreneur every month. However, to most, I am just a nameless writer. That’s why I find it important to add pictures of myself when they are pertinent and allow some of my personality and background to shine through. Just recently, I wrote an article reviewing Grammarly. In it, I had a personal story about how I used it to check my thesis, and showed a picture of a happy Navy LT holding his master’s degree. This wasn’t about playing the readers or being cheesy. It was just taking an opportunity to remind my readers that there IS a human behind these words. Another place for this is your About Me page on your website. Like your bio, don’t treat it like a resume. Give it a little personality.

Taking Influential Actions

When I was in the Navy, my captain used to tell me that mastery only comes when you combine knowledge with experience. Through this, we create intuition—the ability to see and feel the right decision. So, start looking for opportunities in your own book marketing plan so as to gain experience with the art of influence. Combine that with your knowledge and you’ll start seeing the right path.

June 20, 2018

Why It’s Hard to Successfully Start a Story With a Dream

Photo credit: Thomas Hawk on Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page, now available as an ebook. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Learn more about getting a first-page critique.

First Page

It was a lonely sound. A sad lament in the early morning. It was the quivering, somber sound of a wind organ. At least that’s what it sounded like to me. A man with a blue voice was singing and the quiet drumming followed. Plodding lethargically, and vacant… and a slow jangly guitar. The day was cloudy and grey, and there I was, in a bright sliver of sun, peeking through the clouds. I had no idea where I was, but I wasn’t scared. All around me were odd flowers. Startling rich nonagons, bright with color. Searing red, blazing yellow and lavish blue. I wanted to ask, “Why so sad?” but I couldn’t. I opened my mouth to speak and nothing came out. The man with the blue voice sang these words, “nothing is real.” How can that be? Nearby, a herd of horses escaped from a carousel, and headed towards a convertible train. I hopped on, and the sadness went away. The music of a backwards calliope accompanied the ride while hurtling through rolling hills, on loops and curls, like a roller coaster. The train blew its whistle to alert the horses. But the whistle was more like a siren not intended to warn, but to delight. The wind was blowing through my hair and I was smiling so big, my face hurt. It wasn’t a dream. I had been invited to this place through a song playing on the radio. I was really there, I went to Strawberry Fields.

I opened my eyes and I was in my bedroom lying in my bed. The radio next to my bed was playing, softly. My mother gave me the radio, because she knew it would help me sleep, and I was permitted to have it on through the night as long as it wasn’t too loud.

First-Page Critique

Two of the most common admonitions delivered to fiction writers are:

Never begin a story with a character getting out of bed.

Never write, “And then she/he woke up” (or the equivalent).

As with all rules, not only can these two be broken, leave it to a genius to break them brilliantly: “When Gregor Samsa woke one morning from uneasy dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a giant beetle.” With that first sentence of The Metamorphosis, Kafka strikes a definitive blow not only against both rules, but against realism, establishing a parallel universe in which such things happen. No explanations; take it or leave it.

Similarly, in what has been credited as the world’s shortest story, Augusto Monterroso signs the death notices of rules #1 and #2. Here are all seven words of “El Dinosaurio,” or “The Dinosaur”:

Cuando despertó, el dinosaurio todavía estaba allí.

(When he awoke, the dinosaur was still there.)

As with “El Dinosaurio,” this first page gives us a protagonist waking up from a dream, but instead of a dinosaur, what’s still there are the haunting strains of John Lennon’s most famous song, “Strawberry Fields Forever,” playing “softly” on the radio next to the narrator’s bed. In her music-inspired dream, the narrator is transported to a place where “nothing is real,” a realm of “odd flowers” in blazing, searing color, of horses “escaped from a carousel” hurtling toward a train “to the music of a backwards calliope.”

Dreams have their own logic, one that doesn’t play by the rules and is therefore hard to argue with. The same can be said of the best fiction: it makes its own rules by spinning (in John Gardner’s words) a “vivid and continuous dream.” And since a work of fiction is already its own dream, reading about a fictional dream puts us at a two-step remove from our own lives. It’s like kissing through two screen doors.

That said, dreams have played crucial roles in literature. Without Scrooge’s nightmare Dickens couldn’t have written A Christmas Carol. Before he murders the pawnbroker, in a dream symbolizing the soul’s dual nature, torn between bloodlust and compassion, Crime and Punishment’s Raskolnikov revisits a time when as a boy he watched a group of peasants beat an old horse to death. And what is Alice’s looking glass but a doorway to her dreams?

As Francine Prose writes in “Chasing the White Rabbit”, her fine essay on fictional dreams:

Literature is full of dreams that we remember more clearly than our own. Jacob’s ladder of angels. Joseph saving Egypt and himself by interpreting the Pharoah’s vision of the seven fat and lean cows. The dreams in Shakespeare’s plays range as widely as our own, and the evil are often punished in their sleep before they pay for their crimes in life.

The problem with dreams is that, translated into lucid, rational prose, they often sound artificial. Whatever “stuff” dreams are made of, words aren’t it. As Francine Prose goes on to say in the same essay: “What’s [hard] to recreate on the page is anything remotely resembling the experience of actually dreaming, with all the structural and narrative complexities involved, the leaps, contradictions, and improbable elements.” This may be why poets write the best dreams: they’re better at making those improbable leaps.

But a bigger problem with fictional dreams is that they ask us to invest emotionally in an experience only to have that investment rendered null and void when the experience turns out not to have been—by waking standards, anyway—“real.” Just as in life I tend to grow restless when someone buttonholes me with their dream, whenever I come upon a dream in a novel or story I read it with my emotions in check. Heck, it’s just a dream.

On the other hand, if the dream presents itself as real (as this one does) and I invest in it accordingly only to learn that it never really happened, like any bait-and-switch victim I feel cheated. Depending on how much I invested, I may just want to strangle the author.

Here the dream itself is quite well rendered, replete with the sorts of sensuous, specific details that make for a vivid fictional experience (the “quivering” wind organ; the man who sings in a “blue” voice,” those escaped carousel horses hurtling over hills). Though vivid, it’s also rife with the jump-cuts and non-sequiturs that characterize real dreams. And so I can’t help feeling disappointed when I learn that, as the song says, “nothing is real.” There are no carousel horses; there is no “convertible train” (whatever that is). It was all just a dream prompted by a song playing on a radio.

Maybe the dream has symbolic import; maybe it will resonate and/or recur throughout the rest of the story, thus earning back my initial investment. I hope so. I hope, too, that whatever story follows, this dream is the best place to enter it. Perhaps the point of the dream, and the radio that (softly) plays the song that inspires it, is to underscore the protagonist’s fear of the dark and—again, possibly—of the dreams she’d been having, not good dreams like this one, but nightmares that scared her so much she was afraid to sleep. How else explain a mother letting her child play the radio all night long? Raising the possibly pertinent question: What happened to this kid?

Maybe the dream has symbolic import; maybe it will resonate and/or recur throughout the rest of the story, thus earning back my initial investment. I hope so. I hope, too, that whatever story follows, this dream is the best place to enter it. Perhaps the point of the dream, and the radio that (softly) plays the song that inspires it, is to underscore the protagonist’s fear of the dark and—again, possibly—of the dreams she’d been having, not good dreams like this one, but nightmares that scared her so much she was afraid to sleep. How else explain a mother letting her child play the radio all night long? Raising the possibly pertinent question: What happened to this kid?

But if the dream is just this author’s carnival barker way of luring us into her fictional world, I don’t know about you, but I’ll want my emotional deposit back.

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.)

June 19, 2018

The Introvert’s Guide to Launching a Book

Note from Jane: Today’s guest post is by publisher and author L.L. Barkat (@llbarkat) of Tweetspeak Poetry.

If you write a book, it’s natural to want to promote it, right?

As an introverted writer—who for many years misdiagnosed herself as an extrovert because she was outgoing—I can say, without a doubt: no, it’s not natural.

While it might be natural for the extroverted writer, it is anything but natural for the introverted writer when promotion means constant extension of that writer’s self into the world.

Of course, this is a serious problem. No promotion, no discovery. No discovery, no sales. No sales, no impact.

And impact is often what first drives us to write. We want to share a story or a secret that will change people’s lives, entertain them, or give them vision and hope. What a conundrum!

Hope for the introverted writer

There’s a very important distinction tucked into what I’ve said so far, and that is found in the word “when,” as in “when promotion means constant extension…”

This distinction is especially critical for the writer who wants to launch not just one book but multiple books over time. Successive launches make the long haul feel very long indeed. And they make the haul feel like just that: a constant carrying, a burden you simply can’t put down if you want your work to make its way.

Now, unless you are Harper Lee, you are probably going to launch more than one book during your career. In that case, for you, the introvert, I’m sharing six ways to keep your head above water not just for your first book, but also for the long haul.

Here’s the key: each of these ways represents mindsets and methods that mean less constant extension of the self, with an emphasis on things that feel small-scale and limited-time. And remember, just because something feels small-scale and limited-time, doesn’t mean its impact is tiny and timebound.

1. Keep the focus on others

As a new author (ten titles ago), I followed the crowd and focused primarily on my own book and my personal platform. I started a blog that took endless hours to maintain, I entered the social media scene, I spoke at large venues (some upwards of 1,300 people). I knocked myself out, and eventually felt exactly that: knocked out.

In the past few years I’ve come to recognize that my approach was anti-introvert and often anti-me. Some of that work can now be considered important dues paying, but much of it has actually become grist to consider a gentler way for introverts to launch their books.

The first launch principle is to keep the focus on others. For me, that means:

No launch team. Launch teams are often charged with what feels like thinly veiled “look at me!” messages from the author. This can be okay if the author is good with it and the message is creative, but I’ve personally opted out on this, because it goes against my introvert grain. So, if you’re an introvert, consider skipping the launch team.

No professional publicist. About five books ago, I hired a publicist. She came highly recommended, but ultimately I had to “sell” my work to her in ways that I now realize were not compatible with my introverted self. While she did her job in a professional and timely manner, the process was not enjoyable, and the outcomes were minimal. Bottom line: if you decide to hire a professional publicist, consider how hard you’ll have to sell your work to them and whether the two of you are really a fit.

Hire a publicity assistant. If you have connections, and really, if you’re publishing a book, you should have already taken the time to develop some solid connections, then you might be able to hire a publicity assistant instead of a professional publicist. After all, one of the big things a publicist should offer is connections, and if you’ve got them, why pay $5,000+ for someone else’s. I’m doing this for my latest title,

The Golden Dress

, and I’ve chosen an assistant who loves my work and was one of the first to purchase the title—no “selling” to do here; she gets me, she gets my writing. We plan to have fun together, as she’ll be the bold one to make constant contact, and I’ll enjoy giving her a paid means to exercise her personality and skills. If the idea of making constant contact with multitudes for even a few months makes you shiver, too, go smaller and work with an assistant whose personality and camaraderie you’ll enjoy.

Hire a publicity assistant. If you have connections, and really, if you’re publishing a book, you should have already taken the time to develop some solid connections, then you might be able to hire a publicity assistant instead of a professional publicist. After all, one of the big things a publicist should offer is connections, and if you’ve got them, why pay $5,000+ for someone else’s. I’m doing this for my latest title,

The Golden Dress

, and I’ve chosen an assistant who loves my work and was one of the first to purchase the title—no “selling” to do here; she gets me, she gets my writing. We plan to have fun together, as she’ll be the bold one to make constant contact, and I’ll enjoy giving her a paid means to exercise her personality and skills. If the idea of making constant contact with multitudes for even a few months makes you shiver, too, go smaller and work with an assistant whose personality and camaraderie you’ll enjoy.Content marketing (even at someone else’s place). Writing evergreen book-related material is a great way to connect people with your title while giving them something else in the bargain. The content lives on long after you provide it, connecting more and more people with your book over time. For example, to connect people to The Golden Dress, I wrote 10 Terrific Little Red Riding Hood Tales (at Tweetspeak) and A Magical Summer Reading List (at Edutopia). While content marketing is generally understood as something you do at your own place, for the introvert it can be more satisfying to put the focus on others by writing for their sites instead. As an added benefit, you reach audiences that go beyond your own space.

Promote someone besides yourself. This may be easier with titles where you have a partner. For instance, I have a lot more energy when it comes to promoting my collaborators like Gail Nadeau, Donna Z. Falcone, and LW Lindquist—all illustrators whose work either makes me smile or takes my breath away. Still, with a little creativity, you can find ways to promote those who inspired you to the work or who can benefit from the work. It’s not that all this promotion will result in sales, but you’ll feel happier overall, which will give you important staying power.

2. Make art (and encourage art making)

When you first wrote your book, it probably felt like you were making art (at least that’s how book-making feels to me).

If you have a little design flair, or a friend who can lend a hand, I highly recommend continuing in the spirit of art-making by creating a few fun products at a provider like Zazzle.

These products will mostly sell to your die-hard fans, but you’ll receive a small amount of extra cash while launching your book with accompaniments that will outlast the launch date. Also, you can affordably acquire some swag for yourself in a way that creates seamless conversation pieces at work or on-the-go. (I carry my A Is for Azure tote everywhere. It’s beautiful and functional, and it makes me happy.)

Additionally, do you know anyone artistic who might enjoy extending or interpreting the themes in your book? Art is energy. And art is joy. Personally, I encourage all types of artistic responses, especially ones that I don’t have the skills or vision to create myself, like these videos from my daughters (and yes, daughter-the-second will do videos for hire, if you are in need of a trailer for your book).

3. Think beyond sales

As I noted in the opening of this article, “No sales, no impact.” And, while it makes a good general point, it’s not altogether accurate. There is impact to be made by taking the approaches above: focusing on others and art-making. There is also impact to be made by simply giving your books away—and not only to achieve sales.

While a sustainable career will eventually need to rely partly on sales (unless you are professionally set due to lifestyle or other forms of support), sustainability is also about the soul, which, for many of us, means feeling a sense of purpose and impact. Giving your books away will ensure they get into the hands of at least some fans, across a base you might not otherwise reach.

Unfortunately, for the introvert, formal giveaways can feel like another round of “me-me-me.” That’s why I’ve shied from them in the past. However, with a modest budget (under $1,000), you can enlist an entity like Goodreads to do the shoutouts on your behalf (here’s what they’re doing for me).

The extra advantage of Goodreads is that you’re reaching a reading community, as opposed to a more general audience that may or may not spend their precious dollars on books.

4. Use automated services

One of the current prime directives for authors is to offer a newsletter and use it to market their books to readers. Besides adding carrying costs, this model requires a constancy that spells “overwhelm” for the introverted author. If you’re like me, this will mean you won’t do the required newsletter marketing, because, again, it feels too “me-me-me.” Eventually, you’ll end up paying dearly to carry a big list, with little return in book sales.

What’s your alternative? Try using automated services that allow you to design once, then them let roll. My services of choice, through MailChimp, are Google ads and the creation of education series. The most effective Google ads lead potential readers to your education series. Your education series will communicate multiple times with the reader, in a way that leaves you out of the constancy picture and gives them something that invites and intrigues. While this doesn’t always lead to book sales (though it certainly sells more books than non-existent newsletter marketing), it definitely creates impact, as people engage in their own creative acts in conversation with your work.

Interested in seeing a sample? Feel free to borrow ideas from my Rumors of Water series or The Golden Dress series.

5. Stretch just a little

I like to think of a book launch as something that actually happens again and again—kind of like batting a balloon into the air then keeping it airborne with small taps over time. In fact, the author who treats the book launch like one big helium balloon marked “Buy my book now!” is almost sure to find that balloon deflated in the next canyon over, sometimes within mere months.

The problem for the introvert, yet again, is that a million taps over time leaves us feeling tapped. This is especially hard when the taps are happening via live gigs that require us to interact with crowds.

For me, that means I now forego making live appearances (though I might be really tempted to attend a golden dress ball, and wear this dreamy number, minus the prom date, should anyone wish to plan the event).

As an alternative to live appearances—with the benefit that I can immediately retreat and recover in solitude afterwards—I make time for select live audio and print interviews, like these at Joy on Paper and Shelf Awareness.

Whatever it is that tires your introverted self out, I suggest you avoid it for the most part, but do choose to stretch yourself a bit at intervals—as a way to keep the book balloon in the air. The freshness of these intermittent experiences will create a bit of power, and that power contains a vitality that can be appealing to potential readers.

6. Decompress daily

The Internet is a constant place, filled with hype and, sometimes, hopelessness. This is damaging for many people, and it’s quite likely even more problematic for introverts.

Still, the current call to authors is to engage via social media, constantly.

Since I take the long view of my writing career—and that means I’ve got to keep whole and sane—I’ve lately chosen to refrain. I’m not doing Facebook groups. I’m rarely on Twitter. And Instagram has yet to convince me of its allure (despite that I do understand how if you put yourself out there night and day, you can become a celebrity writer of sorts).

For a long time, I did play the Internet constancy game. But it wasn’t sustainable for my introverted heart and soul. I now decompress daily, removing myself from technology, by sitting outside with a cup of tea and gazing off into the green. I take the kinds of approaches presented in this post. If you’re an introverted author, you might give yourself permission to do the same.

June 17, 2018

The Key Book Publishing Paths: 2018

Note from Jane: On Tuesday, June 19, I’m teaching a 90-minute live class on the key book publishing paths today, the pros and cons of each, and which path is right for you. Learn more at Writer’s Digest.

Since 2013, I have been annually updating this informational chart about the key book publishing paths. It is available as a PDF download—ideal for photocopying and distributing for workshops and classrooms—plus the full text is also below.

One of the biggest questions I hear from authors today: Should I traditionally publish or self-publish?

This is an increasingly complicated question to answer because:

There are now many varieties of traditional publishing and self-publishing, with evolving models and diverse contracts.

You won’t find a universal, agreed-upon definition of what it means to traditionally publish or self-publish.

It’s not an either/or proposition; you can do both. Many successful authors, including myself, decide which path is best based on our goals and career level.

Thus, there is no one path or service that’s right for everyone all the time; you should take time to understand the landscape and make a decision based on long-term career goals, as well as the unique qualities of your work. Your choice should also be guided by your own personality (are you an entrepreneurial sort?) and experience as an author (do you have the slightest idea what you’re doing?).

My chart divides the field into traditional publishing, self-publishing/assisted publishing, and social publishing.

Traditional publishing: I define this primarily as not paying to publish. Authors must exercise the most caution when signing with small presses; some mom-and-pop operations offer little advantage over self-publishing, especially when it comes to distribution and sales muscle. Also think carefully before signing a no-advance deal or digital-only deal. Such arrangements reduce the publisher’s risk, and this needs to be acknowledged if you’re choosing such deal—because you aren’t likely to get the same support and investment from the publisher on marketing and distribution.

Self-publishing and assisted self-publishing: I define this as publishing on your own (with or without assistance) or paying to publish. I’ve divided up the self-publishing paths into entrepreneurial or do-it-yourself (DIY) approaches, where you essentially start your own publishing company, and directly hire and manage all help needed, and assisted models, where you enter into an agreement or contract with a publishing service or a hybrid publisher. With the latter approach, there’s a risk of paying too much money for basic services, and also for purchasing services you don’t need. If you can afford to pay a publisher or service to help you, then use the very detailed reviews at Independent Publishing Magazine by Mick Rooney to make sure you choose the best option for you.

Social publishing: In the 2017 version of this chart, I removed social publishing because it seemed marginal and of little interest to the average writer. However, I think that was a mistake. Social efforts will always be an important and meaningful way that writers build a readership and gain attention, and it’s not necessary to publish and distribute a book to say that you’re an active and published writer. Plus, these social forms of publishing increasingly have monetization built in, such as Patreon. In 2017, two of the top ten selling titles of the year were by Rupi Kaur, an Instapoet who began her career by posting her work on Instagram.

Feel free to download, print, and share this chart however you like; no permission is required. It’s formatted to print perfectly on 11″ x 17″ or tabloid-size paper. Below I’ve pasted the full text from the chart.

Big Five (Traditional Publishing)

Who they are

Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Hachette, Simon & Schuster, Macmillan (each has dozens of imprints).

Who they work with

Authors who write works with mainstream appeal, deserving of nationwide print retail distribution in bookstores and other outlets.

Celebrity-status or brand-name authors.

Writers of commercial fiction or genre fiction, such as romance, mystery/crime, thriller/suspense, science fiction and fantasy, young adult, children’s.

Nonfiction authors with a significant platform (visibility to a readership).

Value for author

Publisher shoulders financial risk.

Physical bookstore distribution nearly assured, in addition to other physical retail opportunities (big-box, specialty).

Publisher will pursue all possible subsidiary rights and licensing deals worldwide.

Best chance of mainstream media coverage and reviews.

How to approach

Almost always requires an agent. Novelists should have a finished manuscript. Nonfiction authors should have a book proposal.

What to watch for

You receive an advance against royalties, but most advances do not earn out.

Publisher holds onto all publishing rights for all formats for at least 5-10 years.

Many decisions are out of your control, such as cover design and title.

You may be unhappy with marketing support, and find that your title “disappears” from store shelves within 3-6 months. However, the same is true for most publishers.

Mid-Size & Large (Traditional Publishing)

Who they are

Not part of the Big Five, but significant in size, usually with the same capabilities. Examples: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Scholastic, Workman, Sourcebooks, John Wiley & Sons, W.W. Norton, Kensington, Chronicle, Tyndale, many university presses (Cambridge, Oxford).

Who they work with

Authors who write mainstream works, as well as those that have a more niche or special-interest appeal.

Celebrity-status or brand-name authors.

Writers of commercial fiction or genre fiction, such as romance, mystery/crime, thriller/suspense, science fiction and fantasy, young adult, children’s.

Nonfiction authors of all types.

Value for author

Identical to Big Five advantages.

How to approach

Doesn’t always require an agent; see submission guidelines for each publisher. Novelists should have a finished manuscript. Nonfiction authors should have a book proposal.

What to watch for

Same as Big Five, but advances and royalties from mid-size publishers may be lower than Big Five, especially the more specialized or enthusiast publishing houses.

Some mid-size publishers may be more open to innovative or flexible agreements that feel more like a collaboration or partnership (with more author input or control).

University or scholarly presses typically pay low advances and have small print runs, typically with a focus on libraries, classrooms, and academic markets.

Small Presses (Traditional Publishing)

Who they are

This category is the hardest to summarize because “small press” is a catch-all term for very well-known traditional publishers (e.g., Graywolf) as well as mom-and-pop operations that may not have any formal experience in publishing.

Given how easy it is in the digital age for anyone to start a press, you must carefully evaluate a small press’s abilities before signing with one. Legitimate small presses do not ask you to pay for publication.

Who they work with

Emerging, first-time authors, as well as established ones.

Often more friendly to experimental, literary, and less commercial types of work.

Value for author

Possibly a more personalized and collaborative relationship with the publisher.

With well-established small presses: editorial, design, and marketing support that equals that of a larger house.

How to approach

Rarely requires an agent. See the submission guidelines of each press.

What to watch for

You may not receive an advance or you’ll receive a nominal one. Your royalty rate may be higher to make up for it. Diversity of players and changing landscape means contracts vary widely.

There may be no physical bookstore distribution and/or the press may rely on print-on-demand to fulfill orders. Potential for media or review coverage declines when there is no print run.

Be very protective of your rights if you’re shouldering most of the risk and effort.

Self-Publishing: Entrepreneurial or DIY

Key characteristics

You manage the publishing process and hire the right people/services to edit, design, publish, and distribute.

You decide which distributors/retailers to deal with. You are in complete control of all artistic and business decisions.

You keep all profits and rights.

What to watch for

You may not invest enough money or time to produce a quality book or market it.

You may not have the knowledge or experience to know what quality help looks like or what it takes to produce a quality book.

It is difficult to get mainstream reviews, media attention or sales through conventional channels (bookstores, libraries)

Key retailers and services to use

Primary ebook retailers that offer direct access to authors: Amazon KDP, Nook Press, Apple iBookstore, Kobo. Primary ebook distributors: Smashwords, Draft2Digital, PublishDrive, StreetLib.

Print-on-demand (POD) makes it affordable to sell and distribute print books via online retail. Most often used: CreateSpace, IngramSpark. With printer-ready PDF files, it costs little or nothing to start.

The above retailers and distributors operate primarily on a nonexclusive basis and take a cut of sales; you can leave at will. There is no contract, just terms of service.

If you’re confident about sales, you may hire a printer, invest in a print run, manage inventory, fulfillment, shipping, etc.

When to prefer DIY over assisted

You intend to publish many books and make money via sales over a long period.

You are invested in marketing, promotion, platform building, and developing an audience for your books over many years.

Self-Publishing: Assisted and Hybrid

Key characteristics

You fund book publication in exchange for assistance; cost varies.

Hybrid publishers pay royalties; other services may pay royalties or 100 percent of net sales. You’ll receive a better cut than a traditional publishing contract, but usually make less than DIY.

Regardless of promises made, books will rarely be stocked in physical retail outlets.

Each service has its own distinctive costs and business model; always secure a clear contract with all fees explained. Such services typically stay in business because of author-paid fees, not book sales.

Value for author

Get a published book without having to figure out the service landscape or find professionals to help. Ideal if you have more money than time, but rarely a sustainable business model if you are frequently publishing.

Some companies are run by former traditional publishing professionals and offer high-quality results (with the potential for bookstore placement, but this is rare).

What to watch for

Some services have started calling themselves “hybrid publishers” because it sounds more fashionable and savvy, yet offer low-quality results and service.

Most marketing and publicity service packages, while well-meaning, are not worth your investment.

Avoid companies that take advantage of author inexperience and use high-pressure sales tactics, such as AuthorSolutions imprints (AuthorHouse, iUniverse, WestBow, Archway, and others).

To check the reputation of a service: Mick Rooney’s Independent Publishing Magazine

Social Publishing

Key characteristics

You write, publish, and distribute your work in a public or semi-public forum, directly for readers.

Publication is self-directed and continues on an at-will and almost always nonexclusive basis.

Emphasis is on feedback and growth; sales or income can be rare.

Value for author

Allows you to develop an audience for your work early on, even while you’re learning how to write.

Popular writers at community sites may go on to traditional book deals.

Most distinctive categories

Serialization: Readers consume content in chunks or installments; you receive feedback that may help you to revise. Establishes a fan base, or a direct connection to readers. Serialization may be used as a marketing tool for completed works. Examples: Wattpad, Tapas, LeanPub.

Fan fiction: Similar to serialization, only the work is based on other authors’ books and characters. For this reason, it can be difficult to monetize fan fiction since it may constitute copyright infringement. Examples: Fanfiction.net, Archive Of Our Own, Wattpad.

Social media and blogs: Both new and

established authors alike use their blog and/or social media accounts to share their work and establish a readership. Examples: Instagram (Instapoets), Tumblr, Facebook (groups especially), YouTube.

Patreon/patronage: Similar to a serialization model, except your patrons pay a recurring amount to have access to your content.

Special cases

Agent-run efforts

Some agents have created publishing arms, either as part of their agency or as a separate business. The most significant example is Diversion Books from agent Scott Waxman. Usually these efforts are limited to print-on-demand or ebook only distribution.

Amazon Publishing

With more than a dozen imprints, Amazon has a sizable publishing operation that is mainly approachable only by agents. Amazon titles are sold primarily on Amazon, since most bookstores are unwilling to carry their titles.

Digital-only or digital-first

All publishers, regardless of size, sometimes operate digital-only or digital-first imprints that offer no advance and little or no print retail distribution. Sometimes such efforts are indistinguishable from self-publishing.

For more information on getting published

Start Here: How to Get Your Book Published (traditional publishing)

Start Here: How to Self-Publish Your Book

How to Evaluate Small Presses

A Definition of Hybrid Publishing

Should You Traditionally Publish or Self-Publish?

Earlier versions of the chart

Click to view or download earlier versions.

2017 Key Book Publishing Paths

2016 Key Book Publishing Paths

The Key Book Publishing Paths (2015)

4 Key Book Publishing Paths (late 2013)

5 Key Book Publishing Paths (early 2013)

Note from Jane: On Tuesday, June 19, I’m teaching a 90-minute live class on the key book publishing paths today, the pros and cons of each, and which path is right for you. Learn more at Writer’s Digest.

June 15, 2018

The Power of Silence in a Pitch Situation

When writers ask me for advice about pitching their work in-person, my favorite tip is: Get the other person talking and asking questions. Rather than dominating the conversation with everything you want to say, figure out what’s going on inside the head of your target. That’s where the valuable information is. The nature of their response will help you learn the publishing business and how to position your work.

I have similar advice for anyone talking about their book to a (possibly) uninterested party—or someone who is not necessarily inclined to listen. By leaving out some detail, you leave room for a conversation to develop, to generate some curiosity in the other individual.

My latest column for Publishers Weekly, How to Network Better By Saying Less, expands on this idea.

Part of being a good salesperson for your work is developing a rapport with others and understanding their interests and needs. The conversation can’t be focused on you. You’re not sitting down with Terry Gross and divulging your origin story as a writer, how you were inspired to write the book, the twists and turns the story takes, and the research surprises along the way. Instead, you’re focused on how your product (book) might fill a need for someone else or on looking for points of commonality. You have to put aside any impulse to digress about the content of the book, and instead be curious about and interested in exploring a business connection.

June 14, 2018

What Does It Mean to Write a Scene That Works?

Photo credit: dan.boss on Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC-SA

Today’s guest post is by Rebecca Monterusso, a Story Grid Certified Developmental Editor and writer.

What the heck is a scene, anyway?

“A scene is an action through conflict in more or less continuous time and space that turns the value-charged condition of a character’s life on at least one value with a degree of perceptible significance. Ideally, every scene is a story event,” writes Robert McKee in Story.

Meaning: it’s an event that takes place through conflict that changes the life value of one or more characters. Alternatively: it’s action that results in the character’s quality of human experience changing from the beginning to the end. Put simply: change that occurs through conflict.

You know something is a scene when it pulls a character out of their comfort zone, progressively complicates (for better or worse), asks the character to make a decision, shows that decision, and describes what it means. Or, when a character has fully experienced an inciting incident, progressive complications, a crisis, climax, and resolution. When something has happened to them to cause a change.

Why does it matter?

Because, says Shawn Coyne, “scene is the basic building block of a story.” A bunch of scenes compiled together builds your novel. So you must know what constitutes a scene (and what doesn’t) in order to know whether or not it should be in your novel or thrown into the nearest garbage bin. No one said writing was easy.

So what is a scene, really?

Change through conflict. On the whole, stories are about change. And scenes are a boiled down, less intense, mini-story. They should do the same thing your global story does: upset the life value of the character and put them on a path to try and restore it.

What are value shifts?

Value shifts measure the change in a character’s life. They are on a spectrum based on what’s at stake. For example, the scene where the criminal is caught. The change might move from injustice: the criminal has thus far escaped being discovered, to justice: he is brought in. Compared to the proof of love scene where the change moves from hate or indifference to love or commitment or intimacy. In each of these examples, the start of a scene is very different from its conclusion.

The value spectrum in a scene depends upon what the character wants. Think of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. What they want in any given moment will determine how that scene turns. Either they’ll get it, or they won’t. In any case, there must be a change from the start to the end or a scene doesn’t go anywhere. And, if a scene doesn’t change in life value, it’s either description or backstory. And it shouldn’t be there.

Genre: the overarching structure of your scenes

In the bigger picture, all the scenes weaved together build your novel. And that novel will fit into a certain genre, which determines what’s at stake overall. Genre isn’t meant to be scary or confining. It merely gives you an idea of the expectations your audiences comes to your story already having.

Genre will even help you, the writer, decide which scenes are necessary to your novel and which aren’t. For example, if you’re writing a thriller, you’d better include a “hero at the mercy of the villain” scene or you’ll alienate your audience. And, unless you’re writing a love story subplot, you probably don’t need to worry about a scene where the lovers experience their first kiss.

At their core, scenes boil down to a certain event. The lovers breakup. A stranger knocks on the door. All is lost. Etc. Etc. And, depending on what you want your story to say, you get to decide what those scenes look like and whether or not you even need them in your novel. Genre is the key to making those decisions in a way that will impress your audience and keep them coming back for more.

How to use core emotion, core event, and change to judge your scenes

So you have a scene. In it something takes place and the value shifts for one or more characters from beginning to end. Great. But, how do you know whether or not it should be in this particular novel? By looking at the core event and core emotion. And by evaluating the change that takes place.

To do this, you should know why you decided to write the novel you did instead of the infinite number of other possibilities you could have chosen. What are you trying to say? How do you want your audience to feel after having read your novel? Genre combined with controlling idea will give you an idea of what you were thinking when you rushed this idea to the keyboard.

Then, when you’re evaluating a particular scene, look at its core and how it relates to the bigger picture. What is the event that takes place? The change the character experiences? And the emotion you want to evoke?

Once you have that written down for every scene, you’ll be able to track the overall change and evaluate how each scene gets your character closer to or farther from their ultimate goal. If any scene doesn’t fit with the overall story’s core (the emotion, event, and change) it should probably be cut.

Probably because only you can be the judge. Just make sure you’re a fair one.

What this means for your writing

Hopefully this doesn’t make your head swirl into the unproductive resistance realm from which some never return. My goal is to help you be more critical of your writing, but in a way that is actually helpful. To give you tools and language to evaluate what’s on the page and whether or not it should be included in a final draft.

Being able to look at your writing objectively is key to being a good writer. You can neither be too harsh nor too gentle. And being able to see your scenes from this angle might help you be honest when evaluating something you’ve written.

The goal is to keep readers reading. You do that mostly at the scene level. Knowing how to write a scene that hooks, builds, and pays off will satisfy your readers. And, being objective as to whether or not it should be included in your novel is key.

June 13, 2018

Writing About Addiction: It Often Takes Two Perspectives

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page, now available as an ebook. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Learn more about getting a first-page critique.

First Page

CHAPTER 1: XANAX 2011

“KEVIN!”

My husband, Kevin had never denied me anything. And Sunday October 9th, 2011 was no different. Six months earlier, he had given me his kidney. That morning, all I needed were my pills.

All 97 pounds of me quivered in bed with one objective. Kevin has to pick up my Xanax. I could hear him walking in and out of the house, packing up our one car with his tripod, lights, and zipping up the pockets of his camera bag. He had to be in Orange County by noon to work a wedding. Plenty of time to get my pills, come home, and go to work. Dragging my shaking hands through my hair, I glanced at the alarm clock. 10:07 am. Why was he dawdling? Why was he not at Rite Aid by 9:59 am as the pharmacy’s steel door rolled up offering its medicinal charms to the world? He was such an ass.

I was not sick, but dopesick. A bag of bones wracked no longer with the nausea associated with renal failure, but straight up addiction. My legs twitched under the sheets, knowing my prescription was ready and waiting. I rubbed at my eyes with agitated fingers, aimless fingers that had no purpose unless they were plucking pills from the bottom of their plastic home.

Kevin and I had gone to the pharmacy the day before. I had been told it was “too soon” to pick up my prescription—the dreaded phrase sinks the hungry heart of every pharmaceutical whore. I had thrown myself across the counter angling my scrawny frame towards the pharmacist. Trying to explain why it would be just fine to give. me. my. pills.

First-Page Critique

Writing about addiction is tricky business. While most stories have a single protagonist, addiction narratives are usually about two people: the addict deep in the throes of their addiction, and the recovered narrator looking back objectively on the experience. In that sense, addiction narratives are schizophrenic, offering two perspectives—one reliable, one unreliable—opposing and informing each other. How those two perspectives are apportioned determines the nature of the result.

From its capitalized one-word opener (“KEVIN!”), this first page of a memoir about a woman’s addiction to Xanax put us firmly in the mind of an addict so obsessed with her next fix (“my pills”) she can think of nothing else. Owing strictly to his failure to drive to the local Rite Aid “by 9:59 a.m., as the pharmacy’s steel door roll[s] up offering its medicinal charms,” the same husband she shouts for—the one who, six months earlier, “gave [her] his kidney”—is now “an ass.”

Does the narrator see the irony and injustice in this? If so, she doesn’t let on, not to us readers. She is—at best—unreliable.

Though this opening has us in unreliable territory, it does so retrospectively, in the past tense, with its narrator looking back across so many years. Whether or not we gain any, hindsight almost always gives us some perspective on events. For this reason we expect a past tense narrator to not merely tell us a story, but to shed some light on it.

If, on the other hand, the author’s purpose is to describe addiction subjectively, from within the experience, the present tense would be more fitting. With the present tense, we’re locked with the narrator into the moment, able to see only as far and as clearly as she sees, with as little objectivity, and no reflection. That’s the technique James Frey uses to launch his addiction memoir (novel?):

I wake to the drone of an airplane engine and the feeling of something warm dripping down my chin. I lift my hand to feel my face. My front four teeth are gone, I have a hole in my cheek, my nose is broken and my eyes are swollen nearly shut. I open them and I look around and I’m in the back of a plane and there’s no one near me. I look at my clothes and my clothes are covered with a colorful mixture of spit, snot, urine, vomit and blood. I reach for the call button and I find it and I push it and I wait and thirty seconds later an Attendant arrives.

How far we’ve come from the diffident opening of Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater, the original addiction memoir:

I here present you, courteous reader, with the record of a remarkable period in my life: according to my application of it, I trust that it will prove not merely an interesting record, but in a considerable degree useful and instructive. In that hope it is that I have drawn it up; and that must be my apology for breaking through that delicate and honourable reserve which, for the most part, restrains us from the public exposure of our own errors and infirmities.

Which isn’t to say that the past tense can’t convey an addicted psyche. In Pill Head, his memoir of addiction to prescription painkillers, Joshua Lyon uses it to superb effect:

I was feeling no pain.

I cared about nothing but this.

It wasn’t just an absence of pain. It was warm waves pulsating through my muscle and skin. Breathing was hard, my chest felt weighted down by my own ribcage but I didn’t panic because it’s impossible to feel anxiety about anything when every inch of your body is having a constant low-grade orgasm.

I don’t know how long I lay there on my bed, watching the blades of my ceiling fan slowly turn, lazily spinning tufts of dust before they floated down through the air around me like so much gray snow. Through half-lidded eyes I watched Ollie, my cat, go ape-shit chasing the dust puffs, and it took every ounce of strength to turn my head toward the other side of the bed. …

While it painstakingly recreates his experience (“warm waves pulsating through my muscles and skin”), this opening also objectively reflects on the narrator’s experience (“I cared about nothing but this”). We’re aware of his wish to describe that experience as precisely as possible—down to admitting when he can’t be precise (“I don’t know how long I lay there”). Here the presence of what Philip Lopate calls “the intelligent narrator”—the narrator who has not only lived to tell his tale, but to tell it accurately—is everywhere in evidence.

With the first page in question, on the other hand, we wonder how much we should trust the narrator, or if we can trust her at all. She doesn’t lie. But though she is looking back at her experiences over time, she offers no perspective, no reflection, nothing to suggest a survivor’s hard-won grasp of her experiences. Unless leavened by the sort of insights that only come with reflection, memories and memoirs boil down to anecdote. We get experiences vividly rendered—but, with no perspective to go with them, aside from the vicarious thrills, why should we care? A memoir with no reflection is sex without love, wine without the glass.

Maybe the reflections come later, on the next page. But why not have the intelligent narrator there from the start? I’d do that or lock us into her addictive psyche in a present tense prologue, one that raises the two most pertinent questions: (1) How did the narrator get here? and (2) How will she get out? Then, switching to the reflective past tense, answer them. Either strategy beats having the narrator looking back on the past without perspective.

Otherwise this well-written first page suffers from impatience, with the author trying to do too much at once. It can be whittled down.

Here, whittled, as present tense prologue (minus those hectoring ALL-CAPS):

“Kevin!”

Six months ago my husband gave me his left kidney. This morning all I want are my pills.

“Kevin!” all ninety-seven pounds of me shouts from my bed.

Footsteps pad across the kitchen, a screen door slams. I hear the Honda trunk open, zippers zipping, picture Kevin packing his camera, tripod and lights. My bones twitch under the sheets. My hands shake. My aimless fingers quiver as they pluck absent pills from the bottom of an empty plastic vial. I look at my dresser clock. 10:07. My Xanax is ready and waiting at Rite Aid. Why the hell is he dawdling?

Footsteps pad across the kitchen, a screen door slams. I hear the Honda trunk open, zippers zipping, picture Kevin packing his camera, tripod and lights. My bones twitch under the sheets. My hands shake. My aimless fingers quiver as they pluck absent pills from the bottom of an empty plastic vial. I look at my dresser clock. 10:07. My Xanax is ready and waiting at Rite Aid. Why the hell is he dawdling?

“Kevin!”

More foot treads, more zippers, more doors slamming …

I think: you are such an ass.

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.)

June 7, 2018

You Have a Voice and It Means Something

Last week I was in New York City and had the opportunity to attend In & Of Itself, a one-man show that deals with issues of identity. As you enter the theatre, you have to choose a card to define yourself (as shown above); the show then explores how we see ourselves, how others see us, and how we convey to the world (or not) who we are or what we do. I noticed my reluctance to choose any identity related to writing and publishing—or any label related to my work. (!)

In the latest Glimmer Train bulletin, Jon Chopan discusses how one of his greatest struggles as a writer and human being is to find purpose in what he does, and to help students find purpose. He writes:

Despite the notion that we are voiceless, it seems to me that the challenge of a good creative writing instructor is to teach students that they do indeed have a voice and that their voice, that all our voices in concert, have meaning. … We should be struggling with our students as writers, and students of writing, to leave behind something worth protecting, worth defending, something that contributes to the growth of this culture.

Read his full essay at Glimmer Train.

Also this month at Glimmer Train:

On Discipline by Andrew Porter

The Beginning of a Long Trajectory by Jennifer Egan

June 6, 2018

Art’s Highest Purpose: To Complicate Our Feelings

Photo credit: turbojams on Visualhunt / CC BY-SA

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page, now available as an ebook. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Learn more about getting a first-page critique.

First Page

Mom told me just yesterday not to ever leave the Lovin’ Cup Cafe at nightfall. That even in the tiny city of Pleasantville, nestled up against the Canadian border, strange things can happen as night descends. Note to self: listen to Mom more often.

I watch as Jeff McKinney and Ralph Jones walk into the triangle of light formed by the street lamp next to the road and pause. I walk back into the alcove formed by the handicapped ramp as it rises to meet the cafe’s entrance.

“Well, look what we have here,” Jeff says, smiling right at me and then at Ralph, who smiles back at Jeff like he always does.

I slip my hands into my jacket pockets so they can’t see they’re shaking.

“If it isn’t Jamie Domedian,” Jeff says, pronouncing my last name so it rhymes with comedian. It doesn’t, but I won’t correct him.

Tonight is a first. I’ve never been alone with these two. Their harassment always takes place in crowded school hallways or waiting in line for the bus ride home.

As they walk toward me, I take another step back and feel my thigh up against the wheel of my ten-speed. I do a half-turn, insert the key into my bike lock, and yank the lock cord free, stuffing it in my pocket.

“Don’t you two have cows to milk back at the farm?” Everyone knows McKinney and Jones live miles from here in cow town with all of their farmer neighbors.

Turn the handlebars toward the parking lot. Run, left foot on the pedal, sit on the saddle, and go!

It’s a grand exit until McKinney makes a lunge and grabs the center of the handlebars.

“We’re not here to talk farming,” Jeff says.

First-Page Critique

Now and then my students and I broach the unavoidable question: What makes a work of art? The question can be stood on its head: What makes art work? They’re the same question, really, with (to me, anyway) the same answer: a true work of art is something that doesn’t merely elicit our emotions—as any Hallmark card will do. It confronts us with emotions that don’t quite fit into any of our ready-made boxes.

A simple but good example of this may be found in Jasper Johns’ famous painting of the United States flag. From a distance it looks like any U.S. flag, but step closer and you see the heavy impasto strokes of encaustic (wax) paint. It’s not a U.S. flag; it’s a painting of the U.S. flag. A flag is a symbol; it has a utilitarian purpose. It represents a nation. It’s no more open to interpretation than (for most drivers, anyway) a stop sign. By converting it through an unusual medium and removing it from ordinary contexts, Johns’ painting of the flag opens it up to interpretation. It no longer merely denotes. It connotes. It suggests feelings beyond its literal meaning.

Complicating our feelings: that, to me, is art’s highest purpose.

Which may seem a highfalutin approach to discussing this first page of a young adult novel in which a boy is menaced by two bullies, but the fact is that, in its humble way, this first page does what great art does: it complicates our feelings by confronting us with an unstable blend of danger and humor.

The opening sentence (“Mom told me …”) establishes not only the youthful narrator’s voice, but the setting—both time and place—while foreshadowing conflict: something bad has transpired at the Lovin’ Cup Cafe at nightfall. By saying “Mom” rather than “My mother,” the narrator instantly establishes intimacy with his readers, an intimacy that bonds us to him before we set eyes on his nemeses.

The next sentence of this deft opening nails down the location: not only the size (“tiny”) of the small-town setting, but its situation “nestled up against the Canadian border.” The last sentence of the paragraph drives home the foreboding hinted at in the first, and does so wittily via a note to the narrator’s “self.” Dangerous humor; humorous danger.

Having established setting both generally (tiny city near Canada) and specifically (cafe at nightfall), the author paints an exterior street scene with a few expressionistic strokes, the “triangle of light” from a “street lamp,” and the more specific “alcove formed by the handicapped ramp”—a detail that, because it’s so specific, adds gritty authenticity. We have all we need now to form a solid picture and inhabit this scene.

The first two paragraphs having engaged our sense of vision, with the third paragraph a snatch of dialogue (“Well, look what we have here”) pricks up our ears. However tinged with cliché (and—let’s face it—bullies are clichés), the words offer their own touch of menace, as does the smile that goes with them and that Bully #2 mirrors. (If there’s one thing worse than an antagonist, it’s a smiling antagonist.)

The next paragraph treats us to yet another authenticating touch: how the protagonist’s name isn’t pronounced. Note how this is delivered not as a piece of inert information, but through a dramatic moment, an active description. It’s also ironic in ways that are, again, equally funny and dangerous. Though his name may not rhyme with one, Jamie is something of a comedian. His sense of humor puts him at risk.

Lest we wonder if we might be dealing with routine, Paragraph #6 (“Tonight is a first”) smashes that. What we have here is an event, an inciting incident: something that breaks with routine (“I’ve never been alone with these two”). The next sentence contextualizes the routine against which this exceptional event occurs. It gives us a frame of reference for the bullying that, apparently, has been going on for some time.

The next paragraph has the narrator backing into his bike, feeling “his thigh up against its wheel.” In the movie version, this is one of those moments when the audience gasps and jerks up in their seats. Without needing to be told, we imagine the narrator’s nearly simultaneous responses: first, the shock of being touched by someone/something he didn’t know was there; then relief on realizing it is his means of escape.

Next paragraph, first line: “Don’t you two have cows to milk back at the farm?” Like all good dialogue, it does double-duty: evokes character while carrying information. From this one line we know that (a) however dangerous they are, wise-ass Jamie doesn’t have much respect for his enemies; and (b) our two bullies live in the boonies.

Next: “Turn the handlebars toward the parking lot. Run, left foot on the pedal, sit on the saddle, and go!” Why simply describe a series of actions (“I turned my bike around and pedaled out of the parking lot”) when you can describe them so they convey character? Remember: whatever we do that evokes character is probably a keeper. My one quibble here is that I’d eliminate pronouns and conjunctions: “Turn handlebars toward parking lot. Run. Left foot on pedal, sit on saddle. Go!”

Next: “Turn the handlebars toward the parking lot. Run, left foot on the pedal, sit on the saddle, and go!” Why simply describe a series of actions (“I turned my bike around and pedaled out of the parking lot”) when you can describe them so they convey character? Remember: whatever we do that evokes character is probably a keeper. My one quibble here is that I’d eliminate pronouns and conjunctions: “Turn handlebars toward parking lot. Run. Left foot on pedal, sit on saddle. Go!”

I’ve said more than enough. Humor and danger on the same page—what more can we ask for? This opening got me. Has it got you?

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.)

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers