Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 99

September 9, 2018

10 Ways to Build Traffic to Your Author Website or Blog

Note from Jane: Tomorrow (Sept. 11) I’m teaching a 2-hour online class on how to blog more effectively and grow your readership. Even if you can’t attend live, all registrants get access to the recording. Learn more and register.

Today’s post was first published in 2012 and is regularly updated.

First things first: an author’s website, whether it gets much traffic or not, is foundational to your career. It offers readers as well as the media the official word on who you are and the work you produce. If you blog, then it can also be a way for the public to engage with you. But mainly author websites help you shape the story surrounding your work—and ought to be found when readers go searching for you. It allows you to focus people’s attention and interest to what’s important to you—as opposed to what other sites might think is important.

When writers ask me, “How do I get traffic to my site?” I usually try to downplay the importance of numbers—especially for unpublished fiction writers and memoirists. You can safely assume that traffic to your site will grow as your career grows, whether you try to make that happen or not. (Nonfiction authors might be rightly concerned with traffic to their site as a part of their platform—overall visibility and reach—but platform is about so much more than website traffic!)

So, I don’t think it’s worth unpublished writers’ time to manufacture traffic to their site when they have no work available to be read in the first place. That said, if you’re active on social media and/or regularly sharing work online elsewhere—or have a set release date for your first book—then it can pay to get serious about your website strategy and what role it will play in your platform. But unless you’re generating content, blogging, or doing something interesting at your site, it will be hard to motivate people to visit.

With that preface out of the way, here are some of the tried-and-true methods of getting traffic to your website.

1. Make sure your social media profiles always link to your website.

Twitter, Facebook, and other social media networks always offer—as part of your static profile—an opportunity to link to your homepage. Be sure to do so.

An advanced version of this strategy: Send people to a customized landing page on your website. You may want to create a special introduction for people who visit your website from your Twitter profile, Facebook fan page, Goodreads page, etc.

If you blog: Share a link to new blog posts on each social media network where you’re active. But don’t just post a link. Offer an intriguing question, lead in, excerpt, or explanation of why the post might be interesting to people on that specific social network.

While it may be possible to automate your social postings whenever a new blog post goes live, it’s more effective to give each post a personal introduction based on what you know appeals to that particular community. So avoid bot-like behavior; readers care about hearing from you. (Note that scheduling posts in advance is fine—it’s the automated, unpersonalized posting that you should avoid.)

2. Include your website address on all offline materials.

Whether it’s business cards, print books, handouts, flyers, bookmarks, or postcards—any print collateral—don’t forget to put your website address on it. It’s helpful if you briefly explain any perks only offered at your site, e.g., “Visit my website to sign up for my Savvy Reads newsletter” or “Visit my website to download free worksheets.”

3. Work toward appearing at the top of search results for your author name.

Search engines such as Google should pull up your site whenever people search for terms highly relevant to you, your books, or your content. For most authors, the most important search term of all is the name they publish under. Unless your name is exceptionally common, it shouldn’t be too hard to rank well for your name. But if you are one of those unlucky “John Smiths,” then a better goal is to rank well for something like “John Smith author” or “John Smith book.”

The most straightforward way to ensure your author website ranks well for your name:

Use a domain name that’s similar to the name you publish under

Put your name in the site title (e.g., my site title “Jane Friedman”)

If you get confused for other people with the same name, make sure your site title or subtitle differentiates you as the one who writes and publishes

It also helps to strictly follow #1 above: always link to your author website from your social media accounts to help reinforce, across the board, who you are and what you do.

4. Create pages on your website for each book you publish.

Beyond your author name, it’s great if you can also rank for your book titles and keyword phrases related to your genre. For instance, if you write middle-grade spy novels, wouldn’t it be great if your website came up when people searched for that term in Google?

Some authors go the extra mile to optimize their site in this way. Being consistent in how you describe your work across your website (and elsewhere—like on social media and in your book descriptions) can increase the chances of this happening. Be sure to:

Create a dedicated page on your website for each and every book title

For each book page, make the page title identical to the book title

Use a full or extended description for each book (don’t leave out mention of your genre/subgenre in those descriptions)

All of this falls under the practice of SEO, or search engine optimization. SEO can become quite important if you’re trying to make money online or otherwise build a career through online writing or blogging. However, authors don’t need to have specialized knowledge of SEO in order to follow best practices. Mainly, as I’ve instructed here, make sure your author name is in your site title, have a dedicated page at your website for each book you publish, and use a plugin like WordPress SEO from Yoast to help you follow best practices beyond that.

Here are some beginner guides to SEO:

The Beginner’s Guide to SEO by Moz

The Complete Beginner’s Guide to SEO by Buffer

5. Install Google Analytics and study how people find your site and use it.

If your site is self-hosted, then you should have Google Analytics installed. If not, get started today—it’s a free service and easy to set up. (Instructions here.) After Google Analytics has collected at least one month of data, take a look at the following:

How do people find your site? Through search? Through your social media presence? Through other websites that link to you?

What pages or posts are most popular on your site?

If you sign up for Google Search Console (also free), you can identify what search terms are bringing people to your site.

By knowing the answers to these questions, you can better decide which social media networks are worth your investment of time and energy, who else on the web might be a good partner for you (who is sending you traffic and why?), and what content on your site is worth your time to continue developing (what content will bring you visitors over the long run?).

6. Create free resource guides on popular topics.

If you’re a nonfiction writer, then this probably comes naturally: Put together a 101 guide, FAQ, or tutorial related to your topic or expertise—something people often ask you about. (My most visited resource on this site is Start Here: How to Get Your Book Published.)

If you’re a novelist, this strategy may take some creative thinking. Good thing you have an imagination, right? Consider the following:

If your book is strongly regional, create an insider’s guide or travel guide to that particular region. Or think about other themes in your work that could inspire something fun: a collection of recipes; a character’s favorite books, movies, or music; or what research and resources were essential for completing your work.

If you’re an avid reader, create a list of favorite reads by genre/category, by mood, or by occasion.

If you have a strong avocational pursuit (or past profession) that influences your novels, create FAQs or guides for the curious.

If you’re an established author, offer a list of your favorite writing and publishing resources that you recommend for new writers.

Keep reading for more suggestions!

7. Create lists or round-ups on a regular basis.

A popular way to make people aware of your website is to link to others’ websites; this makes you visible to a broader community and helpful to your readers. If you can do this in a genuine way (that doesn’t look primarily engineered to get you traffic), it’s a win for you, for your readers, and for the sites you send traffic to.

In the writing and publishing community, weekly link round-ups are very common. See Elizabeth Craig for a long-running example.

You can create such lists or round-ups on any theme or category that interests you enough to remain dedicated, enthusiastic, and consistent for the long haul—at least six months to a full year, if you want to see a tangible benefit.

8. Do something interesting on your favorite social media site.

If you’re not blogging, consider what creative project you might undertake on a community-oriented site. Consider:

Daily themed notes on Facebook. (See this guy from 2011.)

Photographs or visuals on Instagram or Pinterest. (See the Instapoet trend.)

Twitter chats (ScriptChat is one example of many in the writing community.)

YouTube videos. (These guys are the masters.)

9. Run regular interviews with people who fascinate you.

Believe it or not, it’s rare to come across an informed, thoughtful, and careful interviewer and interview series (and not just someone looking to fill a slot or post generic content based on pre-fab questions).

Think about themes, hooks, or angles for an interview series on your site/blog, social media, or email newsletter, and feature them on a regular basis—but only as frequently as you have time to invest in a well-researched and quality interview. Such series also offer you an excellent way to build your network and community relationships.

Check these interview series for an idea of what’s possible:

Creative Nonfiction podcast

Other People with Brad Listi

The Creative Penn

10. Be a guest blogger.

Whenever you guest at other websites, that’s an opportunity to have multiple links back to your own site. This helps over the long term with your site’s authority and visibility in search.

A meaningful guest post means pitching sites that have a bigger audience than you, but they should also have a readership that’s a good match for your work. If you need a strong introduction to guest posting how-to, visit this excellent Copyblogger post.

A note of caution: Don’t focus on guest post or interview opportunities strictly tied to the writing and publishing community (unless that is your true audience). You may need to research websites and blogs that feature authors or books similar to you to break out of the publishing industry echo chamber and find people who aren’t writers, but readers. An easy way to start this research is to Google similar authors or book titles—ones with the same target readership—and see what sites feature interviews, guest posts, or essays.

Whenever you make an appearance on another site, always promote the interview on your own social networks and create a permanent link to it from your own website.

Whenever you make an appearance on another site, always promote the interview on your own social networks and create a permanent link to it from your own website.

While these are some of the most popular ways to build traffic to your site, there are many other ways. What has been successful for you? Share your experience in the comments.

Note from Jane: Tomorrow (Sept. 11) I’m teaching a 2-hour online class on how to blog more effectively and grow your readership. Even if you can’t attend live, all registrants get access to the recording. Learn more and register.

September 7, 2018

Writing for Connection Brings Both Hope and Fear

Photo credit: auspices on Visual Hunt / CC BY

As a creative writing student—both undergraduate and graduate—I encountered two predominant philosophies among my professors. (This is stereotyping to some degree, but stick with me for a moment.) One philosophy says: You have to write according to your own internal motivations or creative impulses. If you’re serious as an artist, you’re not thinking about the reader or the audience—doing so leads you astray from the purpose of art, which may discomfit or challenge the reader.

The other philosophy is more concerned with establishing a relationship with the intended audience. How would readers react to or be engaged by the material? How do you create a bond between writer and reader? How much can you demand of them?

Here’s another stereotype: the more literary the work, the more likely the author ascribes to the first philosophy. The more commercial or genre-driven, the more likely the author has concern for the reader.

But that’s not to say the two approaches don’t co-exist in the same author or in the same work. I was reminded of this when reading Victoria Alejandra Garayalde’s piece in the latest Glimmer Train bulletin. She writes:

Mostly, I write because I need you and see you, and I write out of the desperate and fragile hope that you might see and need me too. I see writing as a way for me to create a path of connection to others, to this life, and to myself. It’s not easy to forge a path through all the debris of self-doubt, fear, self-hatred, and outside messages of selfishness and expectations. This is why I write in the mornings, because that is when anything and everything feels possible—or at least enough to warrant an attempt.

Read her full essay, I Write for You?

Also this month in Glimmer Train:

Vast by Valerie Trueblood

The Curious Border Between Fiction and Nonfiction by Nellie Hermann

September 6, 2018

10 Instagram Tips for Writers

Today’s guest post is by novelist Annie Sullivan (@annsulliva). Her debut work, A Touch of Gold, released in August 2018.

The other day, a high school freshman walked up to my book signing. When I asked if she had a Facebook account, she said, “No, Instagram.”

I should’ve known. For a while now, I’ve heard that Instagram is the new social media place for writers, but it felt confirmed in that moment. Younger generations (and even some older ones!) flock to Instagram for its feed of beautiful pictures.

So how can writers use Instagram to their benefit? Here are some easy things to keep in mind to find and engage your target readership on Instagram.

1. Use Hashtags Strategically

Hashtags help your Instagram posts be seen by people not following you. There are countless numbers of hashtags you can add to your post, but if you add more than 30, Instagram deletes your caption entirely—so keep below that limit.

To find the hashtags where your readers are hanging out, looking through #bookstagram is a good place to start. If nothing else, find authors with books similar to yours and see what writing hashtags they’re using and copy those.

Here’s an example of a post where I’ve added hashtags.

2. Run Giveaways

Giveaways help you gain followers while marketing your book at the same time. I’ve found my most successful giveaways include signed copies of books or bigger prizes. I also love pairing a signed copy of my book with a signed copy of an even more well-known author in a genre similar to my own. That way, I can draw on that author’s established fanbase. Plus, more people will want that more well-known book and enter.

I set up the giveaway so that entrants have to tag a certain number of friends (I’ve found two to three to be a good number) in the comments section to enter. Thus, those friends see the giveaway and hopefully enter too.

Note: There is some official language you need to include in your giveaway, which you can find out about here.

3. Stick to the 80/20 Rule

There’s a marketing rule that says you should promote your own work 20% of the time and post other things 80% of the time. If you simply self-promote over and over again, people will get bored with your content and unfollow.

Instead, share engaging, new content that relates to what you write—maybe fan art of your character, an idyllic setting that could appear in your books, you sitting at your computer writing. Figure out what posts get the most interaction and lean on those.

4. Engage Engage Engage

Find out what other Instagrammers your ideal reader follows and engage with their posts. Strike up conversations with fans about shared passions, and you might just find yourself with new followers.

5. Make Opportunities

Make anything into an Instagram opportunity—especially something you were already using for marketing purposes. Did you just get some cool new swag or bookmarks—either for your book or someone else’s? Post that! And tag the authors/creators/gifters/whomever, so they might see it and comment.

When I had my book launch party, I had a massive book-themed cake. Not only was it delicious, but it made for a great picture—a picture that had my book placed front and center as the cake topper!

6. Post Often

Don’t go weeks (or even a week!) without posting. Try to post every day if you can. This will keep you top of mind and show Instagram that you’re an active user.

Experiment to see what times of day get you the most engagement. If your target market is teens, posting at 9 a.m. on a Tuesday may not be great because they’re most likely in school. Try to think like your target market to see when they might be online. Again, when in doubt, copy the authors you follow and post when they do.

7. Ask Questions

Asking questions in your caption gives people something to comment on, and the more comments your post gets, the more likely the Instagram algorithm will think it’s engaging content and push it to more feeds.

You can ask followers what they’re reading, what their favorite book is, or what they plan to read this weekend. For example, two days before A Touch of Gold launched, I posted this photo asking followers what they would turn to gold if they had the power.

8. Don’t Buy Followers

While it may be tempting to spend a few dollars to increase your following quickly, those fake followers aren’t going to be liking your content, commenting on your posts, or buying your books. It’s best to build your following organically so you know you have followers who actually like what you do.

9. Sponsor a Post

Using Facebook, you can create ads that run on Instagram, and boosting a post can be a great way to target your readers. Just keep in mind that if you’re cross-promoting across Facebook and Instagram with the same ad, a whole bunch of hashtags don’t look good on a Facebook ad—and no hashtags means your discoverability on Instagram won’t be as good. So create a good balance. I recommend hiding hashtags below text so they can’t be seen on Facebook if you’re promoting the ad on both.

10. Study and Experiment

No one will look at your pictures if they’re out of focus, boring, or uninteresting. Study what other authors and bookstagrammers are doing in their photos and copy them. Use interesting props (some of which you can find at the Dollar Store!). Experiment with lighting and angles. Use good backdrops. A sheet can work in a pinch, but I’ve found regular black or white poster boards provide a good, clean backdrop.

For more inspiration

Check out some of my favorite Instagrammers:

darkfaerietales_

elizabeth_sagan

readthewriteact

elle_modesto

Additionally, Instagrammer mybookfeatures curates great book content from all over Instagram. Whatever photos you post, try to keep consistent themes throughout so people will start to recognize them as yours!

September 5, 2018

How Writers Can Overcome Their Fear of Public Speaking

Photo credit: TEDxStuttgart on Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC-ND

Today’s guest post is by Betsy Graziani Fasbinder (@betsygfasbinder), author of From Page to Stage: Inspiration, Tools, and Simple Public Speaking Tips for Writers.

“Your assumptions are your windows on the world. Scrub them off every once in a while, or the light won’t come in.” —Isaac Asimov, author, professor of biochemistry

Lots of people look at a skilled public speaker and think: I wish I could do that. I wish I could speak with such confidence. I wish I could be so engaging, dynamic, and fascinating. I wish I’d gotten that gift.

Perhaps you are holding assumptions about whether you do can do public speaking well, or even have the potential to do it well. I ask that you take the advice of Isaac Asimov in the quote above; scrub those assumptions off. The skills of good public speaking can be learned. The tools can be utilized. It’s not rocket science. The biggest obstacles for most potentially fabulous and inspiring speakers are the attitudes and assumptions they hold, and the lack of a few simple skills they can develop when willing.

I coached one author to help her prepare for her book launch. She wrote a stunning book. In the first moments of our time together, she boldly announced, “I know that I’ll never be one of those WOW kind of dynamic, charismatic public speakers. I just want you to help me to get through my book launch without humiliating myself.”

Doesn’t “not humiliating yourself ” seem like a pretty low bar? What self-limiting beliefs do you hold about yourself as a speaker? I propose that these beliefs may or, more likely, may not be accurate. What’s more, even if they’ve been accurate in the past, they do not have to be so going forward.

Public speaking skills are more akin to musical or athletic skills than intellectual knowledge alone. Mastery does not take place simply in your brain; it takes place in your body, in the “doing” of it.

So let’s address the key fears of public speaking, which fall into a few categories.

Fear of Looking the Fool

Over and over again my coaching clients say things like, “I just don’t want to look foolish.” For many of us, the simple fear is this: I just don’t want to feel embarrassed in front of a group of people. This fear may come from our past experiences of feeling embarrassed, being made fun of, or even being ridiculed. Those who’ve had such experiences deserve support and empathy, of course. You also deserve to have your own confident voice, even if you’ve had such experiences. Can there be embarrassing moments in public speaking? Sure!

But if you connect vulnerably, intimately, and authentically to an audience, they’ll forgive you nearly any kind of natural mistake or mishap. Being flawed and human are strengths, not weaknesses. It is our unrealistic, often perfectionistic drives that make us think we must be flawless in front of an audience. If handled with humor and heart, our mistakes may not only be unimportant, they can serve to connect us more intimately with our listeners by showing our humanity and compassion.

The “Too” Problem

I hear a lot of people voice their fear by using the word too. I’m too old. I’m too inexperienced. I’m too shy. I’m too young. I’m too unknown. I’m too overweight.

If you are legitimately under-qualified to talk about a given topic, either get qualified or don’t talk about it. Seems simple. That’s not what the “too” problem is. What we’re talking about here is unfounded self-doubt or what a lot of people call the “inner critic.” This fear is uttered by some of the most highly qualified people in their fields.

I once coached a double-PhD chemist who had served as lead in discovering and developing a revolutionary pharmaceutical product. I coached him for an upcoming presentation of his team’s research findings to gain multimillion-dollar funding to bring the product to market. Despite his education, his qualifications—and what I assert is his freaking genius—this scientist feared that he was “too young” to be perceived as credible. He suggested that a more senior member of his team should make the pitch. “They’ll never take me seriously and grant millions of dollars to someone they think of as a kid,” he said. When I probed, I determined that though he had a youthful appearance, he was no more than a few years younger than the investors to whom he was presenting and senior by far to all of them in his experience and education. His perceived “too young” problem became a little laughable when we did the math.

Finally, he surrendered. “I think I’m just looking for something to disqualify myself, aren’t I?”When we feel we are “too” something, it’s usually self-doubt and little more. After crafting his story and practicing its delivery, my chemist client not only got his funding, he got more than triple what he requested. The investors saw not only the value of his idea, but also the importance of him being the public face of the product as it goes to market. His age was never a factor to them, just a smoke screen of his self-doubt and fear.

The “Not Enough” Problem

The fraternal twin of the “too” problem is the “not enough” problem. I’m not smart enough. I’m not experienced enough. I’m not charismatic enough. I’m not funny enough. I’m not fill-in-the-blank enough.

The “not enough” problem stems from comparison. We measure ourselves—and all of our perceived shortcomings—against someone we estimate as superior. Introverts envy extroverted presenters who appear at ease, funny, dynamic, engaging, and charismatic and think, “I could never be as good as that.” Extroverts, who have plenty of dynamic energy, may envy a calm, poised, focused, self-possessed speaker, and say, “I could never be as good as that!” Others are more beautiful, more famous, more educated, more whatever. In the game of comparison, the one comparing always comes up short.

The irony here is that when they are in casual conversations, the same people who feel they are not funny/engaging/etc are often all of those things. It’s just when they stand up and feel that they’re doing a “presentation”—when they’re “public speaking”—that they clam up, look down, shut down, and indeed appear “not enough” for the task when they are more than qualified to speak about their topic. But believe me—you’re enough.

What If I Cry? Freeze? Trip? Or Goof Up Big Time?

Now we’re getting specific.

My clients, across all kinds of industries, have shared anxiety about their autonomic responses (tears, freezing up, panicking, getting hives, shaking, sweating, digestive trouble, the list goes on) that they avoid public speaking for fear that one or more might happen. It’s important to know that it is not the reality of public speaking that causes sweaty palms, hives, trembling, or digestive problems; it is the fear of it that causes these maladies.

Forgetting what you’re going to say or losing your train of thought is a common experience for most speakers, newbies and those with boatloads of experience. It happens all the time and to everyone. Do what the experienced speakers do: Roll with it. Relax. It’ll come to you. People won’t judge you harshly if you lose your train of thought, but they’ll judge you harshly if you freak out about losing your thought, especially if you let it taint the rest of your talk.

The fear of forgetting is often key to the rest of these symptoms. Good preparation for your talk and having simple notes as backup will prevent most public memory loss along with quelling some of the anxiety. The real trick for this worry is to relax and trust that you know your topic and can retrieve the ideas you need to. If you lose your train of thought, simply stand still, pause, put a pleasant, neutral expression on your face (like you’ve planned this all along) and breathe. Take a sip of water. Check your notes if you need to. The thought will come back to you. If it doesn’t, move on. Nobody will be the wiser.

Let’s face it—if you give lots of presentations, some will be better than others and occasionally you’ll have an off day. Preparing and improving your speaking skills will increase your average by a big bunch, but everybody has days when they’re “in the zone”, or when they’re a bit off. I’ve delivered thousands of hours of training, coaching, and speaking. Not every moment would get an A in my own mind—the burden of having high standards—even when the participants gave me high marks. Accepting this disparity as well as the fact that even when I give a stellar class, the occasional participant may not like it, my message, or me, has freed me of worrying about it. I’m not going to say I love it when a class isn’t up to my standards, just that it’s occasionally true. The more you speak, the better you’ll get, but perfection and one hundred percent approval cannot be the goal.

Most audience members will accept human errors and mishaps. It’s all about how you handle them. Do they unravel you, or do you roll with them? Do you have a sense of humor about it, or does your inner perfectionist come out and cause you to show your frustration?

As a writer, you know that sometimes you have to write before the muse arrives, and long before you’re confident in what you’re writing. It’s the same with speaking. Showing up and letting ourselves be our most honest, vulnerable selves ultimately results in courage. If we wait for courage to arrive, it never does. If we act courageously, and show up, courage arrives.

As a writer, you know that sometimes you have to write before the muse arrives, and long before you’re confident in what you’re writing. It’s the same with speaking. Showing up and letting ourselves be our most honest, vulnerable selves ultimately results in courage. If we wait for courage to arrive, it never does. If we act courageously, and show up, courage arrives.

If you found this post helpful, be sure to check out From Page to Stage: Inspiration, Tools, and Simple Public Speaking Tips for Writers.

September 4, 2018

How Long Should It Take to Write a Book?

Today’s guest post is by author Merilyn Simonds (@MerilynSimonds). Her newest book is Refuge.

Writing a novel requires the creation of a living, breathing, fully populated world. Deities can pull off a trick like that in six days, but how long should it take to write a book?

William Faulkner wrote Light in August in seven months, a slog compared to As I Lay Dying, which he wrote in less than six weeks while working the night shift at a power plant. Jack Kerouac spent seven years on the road, but the actual writing of that iconic book took less than a month, typed on a single, taped-together roll of paper. Anthony Burgess wrote A Clockwork Orange for money and churned it out in three weeks. John Boyne gave voice to The Boy in the Striped Pajamas in a breathless two and a half days.

Surely years, not weeks or months, is the norm. A quick glance at the oeuvre of writers like Margaret Atwood, Alice Munro, and Louise Erdrich suggests that writers devoted to their craft can manage a new work of fiction every two to four years.

It used to bother me that I took twice that long, sometimes longer, to finish a manuscript. Am I lazy? Word-challenged? Easily distracted? Or just plain slow?

I drew solace from writers such as Junot Díaz and Margaret Mitchell, who took a decade to write The Brief, Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao and Gone With the Wind, respectively. J.R.R. Tolkien labored twelve years over Lord of the Rings, one of the bestselling novels of all time. Alistair MacLeod, with whom I often commiserated on being a slow-mo writer, worked on No Great Mischief for 13 years before his editor wrested it from his hands.

When I started Refuge, my latest novel, I was determined to shorten my writing time. Three years, I told myself sternly. Four, max. And I met that deadline. Exactly four years later, I submitted the manuscript to my agent, who sent it to my editors at McClelland & Stewart and W.W. Norton. I scheduled some minor surgery, imagining myself recovering on my couch, eating bonbons and contemplating the six-figure offers.

“It’s not a novel,” my editors said. My agent sent the manuscript to other publishing houses. Editor after editor rejected it. Many offered suggestions. Put the last chapter first. Focus on the son. Focus on the sister, on the time in Mexico, on New York, on the love story.

I was devastated. I put the novel away amid gloomy thoughts that I would never write again. I started a literary festival. I started a biweekly books column. I started a gardening blog.

That was in 2008. I had laid down the bones of the story of Cassandra MacCallum, a 96-year-old who had made a sanctuary for herself on a small island behind the farm where she was born, in my 2004 notebook. Now this smart, feisty woman refused to stay in my bottom drawer. Every so often, I’d get an idea of how I might rework her story and I’d haul out the manuscript, mess with it for a few months, then give up as her sharp, sassy voice was drowned out by my editor’s pronouncement. It’s not a novel.

I am stubborn by nature. Put an obstacle in front of me and I’ll wear myself to the bone trying to find a way around, under, over it. But no amount of thinking could break through my idée fixe of how this story should be told: a woman’s life from birth to death, the reader knowing Cass MacCallum in a way we almost never get to know anyone in real life.

Four more years passed. I tried not to count. Then, in 2012, I was a guest at the San Miguel de Allende Writers Conference with a Famous Writer friend. We never talk writing: we talk gardening, and life, and books. We laugh. Sometimes we sing silly songs in Edith Bunker falsettos. But sitting over coffee one morning, our conversation turned to how many drafts of a book we typically write. Fifteen, she said. My usual is also fifteen, which somehow gave me courage to add, “But I’m having real trouble with this one.”

“Tell me about it,” she said. So I did.

“It’s the story of a woman who is the ninth daughter of an amateur naturalist/inventor who dies of tuberculosis. She contracts the disease and recovers in a sanatorium where she is inspired to become a nurse…”

“Stop!” she moaned. “This is like being on a bus and someone sits down beside you and opens their photo album and says, This is a picture of me in Paris, this is a picture of me in Rome, this is a picture of me in London. In ten seconds you want to slit your wrists!”

She was right. Recounting the story out loud, even I was bored.

“You need a shish-kebab rod to hang those stories on,” she said.

That was the prod I needed. Within a week, I had my story rod. I printed all the scenes I’d written so carefully over the years, cleared a space on the living room floor, and started moving the shish-kebab bits around. Instead of a rigid chronology, I had a mosaic that could be worked and reworked a thousand different ways.

That was the prod I needed. Within a week, I had my story rod. I printed all the scenes I’d written so carefully over the years, cleared a space on the living room floor, and started moving the shish-kebab bits around. Instead of a rigid chronology, I had a mosaic that could be worked and reworked a thousand different ways.

Three more years passed. Finally, I had a final draft—my 22nd. The story was still the same, but the way it unfolded had changed dramatically. My agent loved it. An editor bought it.

When someone in the audience asks, how long did it take you to write this book, I say, “Fourteen years.” But of course that’s not true. I wasn’t writing during all those fourteen years: I worked on the manuscript in bursts, the pages languishing for months and sometimes years while I gathered my thoughts for the next revision.

Carl Honoré, author of In Praise of Slow and guru of the Slow Movement, had his wake-up call to the North American obsession with speed when he caught himself admiring a book of one-minute bedtime stories. Refuge was my epiphany.

I no longer think that a book should be written in a prescribed amount of time. I’ve stopped beating myself up for coming to a structure slowly, for needing to get to know my characters as gradually as I get to know people in life. I welcome the pauses in the work, knowing that my thinking deepens in that time away. I don’t worry that I’ll change over the years it takes to finish a novel because I know the story is growing, too, becoming more layered, more nuanced. And yet, miraculously, the heart of it stays the same. The opening paragraph of the published novel is almost identical to what I scribbled in my notebook 14 years ago.

What is impossible for a writer to predict is the world their novel will be released into. In 2008, this story would have been an anomaly. In 2018, its exploration of who we give refuge to and why is part of one of the most important conversations of our time.

It isn’t easy to embrace writing as a long game. I’ve learned to smile when I answer the well-meaning queries of family and friends with, “Yep, still working on it.” I don’t force myself to write a certain number of pages a day or set a deadline for each draft. I work at the pace the story needs. I still rail against the way life can sabotage my writing time and I still struggle to find the best way into a story. But I’ve stopped feeling guilty and inadequate, afraid that I’m not a real writer because of the pace at which I work.

I’m halfway through a new novel called ~then~. I have no idea when it will be finished. Within my lifetime, I hope. My mantra is simple:

Write. Write well. Write to the end. Take as long as you need.

August 15, 2018

5 Steps to Writing Better How-To

Today’s guest post is by Betsy Graziani Fasbinder (@betsygfasbinder), author of From Page to Stage: Inspiration, Tools, and Simple Public Speaking Tips for Writers.

In the age of YouTube—where instructions for many of our daily how-to challenges can be answered with a click—the needs for books in the how-to genre are changing. If the answers to your potential readers’ questions can be satisfied by watching a video, inquiring of Siri or Alexa, or consulting one of the plethora of For Dummies books already on the shelf, you may not need to write a book on that topic.

While the landscape of the how-to genre is changing, it’s not disappearing. Authors who have a unique voice or vantage, special knowledge and expertise, or can provide useful tools and a deep understanding of their subjects fill a valuable niche on the how-to shelves. Whatever your how-to topic—from techniques for a meditation practice, a method for inviting more songbirds to your yard, or encouraging an eco-friendly lifestyle—it’s by using great writing skills and telling an engaging story that authors of how-to books can offer value.

The following five steps can help you to simplify the writing process for how-to books and help you to write them in a way that allows today’s readers find value in their pages, and in you as an expert and valued resource.

1. Simplify your writing process.

A how-to book is not a literary novel and shouldn’t try to be. Still, it’s useful to remember that the best way to convey information is to tell a story, rather than doing a data dump. You’re telling the story of how to whatever subject you’re writing about can enhance your readers’ lives in one way or another. Information, wrapped in inspiration, conveys your passion for the subject.

It’s a mental shift to think of a how-to as a story, but a necessary one if you want to capture the attention of readers.

Beginnings are how writers hook readers. I suggest starting your how-to book—and indeed each chapter within it—by offering a high level statement of the problem, challenge or opportunity of your subject. Then, offer your point of view about that as a high-level solution to that problem at the beginning of every chapter. By doing this, you’ll engage your readers from the start.

Notice how I began this article. Just as I’m suggesting for a how-to book, in this article I begin with a high-level statement of the challenge, my point of view on the subject and the high-level solution. Once you’ve set up the issue and your point of view, you have the rest of the pages for offering details. Too many books in this genre start out in the trees (details), rather than in the forest (the big picture). Open with the big picture, and then offer the details.

While you don’t want your writing to feel like a formula—which can feel repetitive and boring—a repeated structure in a how-to for each chapter offers readers a sense of order. Repeated features, like using quotes, having a “try it out” section, or offering a list of links and resources at the end of each chapter or section can offer structure, which readers find comfortable. Determining a pattern for such special features can also help you to abbreviate the process of writing the book.

2. Don’t try to teach every single thing you know.

If you’re writing a how-to book about a topic, one would hope that you have fair knowledge about that topic. Even in book length you’ll likely not have enough space to convey everything you know. What’s more, if you try to write every nuance, example and detail, you’ll have to write an entire set of encyclopedias, rather than an accessible and marketable how-to.

Today’s readers don’t look for encyclopedias. They look for resources and inspiration. That means editing what you know down to what your readers want and need to know, with some surprises and delights along the way. That’s where your good writing skills are needed.

I like to think of selecting the information I want to share in any form as akin to packing for a trip. What are the things I know I must have? What are the items that would make the trip easier, and perhaps more fun? And, what things might I toss in the bag only if I have enough room? Sorting your content into the musts, mights, and truly optionals helps you pare down and resist over packing.

Feedback from beta readers and editors are invaluable at this point. If you leave something out that keeps them from understanding your idea, they’ll let you know. If you’re redundant, or the book is too long, they can let you know that, too. Pack the essentials and the important comfort items, and be selective about those optional luxuries.

3. Modernize for today’s audience.

Not so long ago, a bibliography included almost exclusively references to books and articles. Today, you can offer a more vivid set of resources including recommendations for blogs, vlogs and online videos filmed by others or by you. You can offer TED Talk references, social media sources, and if yours is an ebook, you can offer links to resources you believe are stable and will not be deleted. Of course, your website is another important resource, particularly if there are downloadable resources there that supplement your book. Think beyond books and articles when you’re sharing examples. It will make your book more interactive.

4. Use spellbinders to make the ideas clear and memorable.

Writers of stories, novels and memoirs are accustomed to the age-old instruction, “show, don’t tell.” Simply put, this means that if you’re trying to convey the grief of a character, using action, dialogue and interaction reveals more of the emotional essence than simply saying that the character “felt sad after the loss of her father.”

“Show, don’t tell” works in this genre in another way. A story, metaphor, case example or visual image can “show” an idea you’re conveying more vividly than simply providing a list of information.

I call these devices “spellbinders” because they entrance readers. Tell the story of how you once thought bird watching was the nerdiest hobby ever, then describe the first time you saw a red-tailed hawk. Describe how it made your soul soar, how you got obsessed with birds of prey thereafter or describe the swooning flight. This goes a lot farther toward casting a “spell” than if you just “tell” by saying, “bird watching is fun.”

Offer examples, metaphors, brief stories, sensory details and emotional experiences about your topic. If photography or designed graphics can help, this is where to use them. Dig deep. If you care about your topic, you’ll have spellbinders. If you share them, your readers will care too.

5. Keep your audience front of mind.

On most smartphones there’s a function on the camera that allows you to flip the screen: in one position you can see your own image, on the other you can see the audience. It’s important to remember that a how-to should not be like a selfie, focused only upon the author and his or her knowledge. Instead it’s better to think about the impact of the information, inspiration, vivid details and your colorful writing voice will have on your readers. As you write—and certainly as you edit—I advise flipping the screen. Look at your subject from the vantage of the reader who may learn differently than you do and who may, or may not, be new to your subject matter.

Keeping your reader front of mind will help you to determine the musts, mights and luxury items. It will also help you to determine the tone, style and level of detail you’ll include or edit out. This is another way to employ those beta readers, who represent your target audience, can help you know if you’ve hit the mark.

Keeping your reader front of mind will help you to determine the musts, mights and luxury items. It will also help you to determine the tone, style and level of detail you’ll include or edit out. This is another way to employ those beta readers, who represent your target audience, can help you know if you’ve hit the mark.

A great how-to book is a conversation between a reader who wants or needs some information or inspiration, and an author who has some to share. By providing simple structure, modernizing resources and keeping your writing conversational and the needs, wants and especially interests of your readers in mind, your how-to can become an invaluable, and highly buyable, resource to readers.

August 14, 2018

For Indie Publishers: When and Why to Work with a Trade Book Distributor

Photo credit: risaikeda on Visualhunt / CC BY-NC

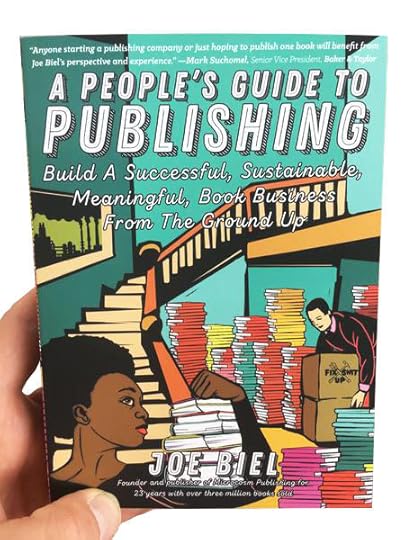

Today’s guest post is excerpted from A People’s Guide to Publishing: Building a Successful, Sustainable, Meaningful Book Business From the Ground Up by Joe Biel (@joebiel_) of Microcosm Publishing.

As a small and new indie publisher, it’s hard to sell even 100 copies of a book in a month, let alone every month. Bookstores will give you the runaround of why they can’t stock your book because of such-and-such ordering policy. If a book is not published with advance notice and it’s by an unknown author and an unknown publisher, that’s three strikes for most major accounts and you’re not even considered.

Many new publishers thus believe that gaining access to trade distribution would be the holy grail of their publishing quest. But like all things that we think we want, the results are not exactly what you might expect.

A trade distributor is a partner company who takes over the tasks and responsibilities of selling your books to trade accounts like bookstores and wholesalers. Because of their size and scope, trade distributors often have better leveraging power to sell books, get good placement for the books they represent, and, last but not least, get paid for books that have been sold. A trade distributor typically takes 27% of each invoice as their compensation. In this way, they are never losing money on a sale—though you may be.

Independent Publishers Group (IPG) invented the concept of a trade distributor for independent presses in 1971. The explosion of independent publishers at that time created a problem because bookstores were reluctant to set up accounts with every new publisher due to the extra work that it creates. A trade distributor brought credibility and stability to new publishers, and stores were more comfortable working with a familiar entity. IPG was bought in 1987 by Chicago Review Press, and today they employ 150 commissioned sales reps with the most boots on the ground of any distributor, including 100 gift reps, 20 commissioned education reps, and a special sales force that was up 14% in 2016.

There are smaller trade distributors like Midpoint, SCB, and National Book Network. There is the family of larger trade distributors owned by Ingram: Consortium, Publishers Group West, Two Rivers, and Ingram Publisher Services. Other large trade distributors include Baker & Taylor Publisher Services, Diamond Book Distributors, Hachette, and Penguin Random House Publisher Services.

The two greatest functions of a distributor are helping you with title development—they are experts in making it easy to understand what a book offers—and getting you into all of the stores that would love to have your books but just “can’t” purchase directly from you. A good distributor allows a bedroom publisher to operate competitively with major houses. Distributors create demand for books by contacting account buyers. Wholesalers fulfill that demand and keep stores stocked quickly after the initial push.

Once you have a book that has sold at least 5,000 copies and at least three titles that are selling consistently month over month, it’s a good time to begin shopping for a trade distributor. These stats show that you have an audience who will buy your work and is hungry for more.

Shopping for a distributor is like seeking any other kind of relationship, business or personal. You want to shop around and go with the one that seems to really get you and your books the most. You also will want to negotiate your terms, and continue to work on improving the relationship so that you can both succeed. It is vital to stress that it works best when it’s symbiotic and you are working together.

According to Mark Suchomel, Senior Vice President of Baker & Taylor Publisher Services, a publisher should approach a distributor “when they have plans for a good, ongoing publishing program. I’ve taken on publishers who have just a few titles where I saw that they could take that into a program and make it work. The distributor has to invest a bit of time and resources in order to make a publisher successful. Most distributors should have some room to make those investments. I’ve watched publishers go from a few books in a few years to a few million dollars in annual sales.”

Still, working with a trade distributor is a risk. There are many publishers competing for the same shelf space; meanwhile that space is shrinking. Of the millions of books published last year, Barnes & Noble stocked a small fraction of them—and returned many copies. A trade distributor takes a much bigger cut than retailers or wholesalers—you normally only get paid 40% of your book’s cover price or less on the books that do sell through—and there are many little costs and fees that can add up quickly. It’s easy to get in over your head, but this is the math you must stay on top of to make the relationship work.

Remember that the staff at your distributor is doing work that you either can’t or don’t want to do yourself. The work is often not nearly as glamorous as the artistic side and involves a lot of paperwork and rejection. Appreciate trade distributors for what they do and don’t approach them until you are ready and can’t move forward on your own. It’s like having a new partner that you work with to reach new places rather than a new person to do part of your work for you. Signing with a trade distributor means you are changing your distribution model, and it’s not necessarily a better one than staying small. The things that are profitable for your distributor are not necessarily in your best interest.

The perception of many new and would-be publishers is that having a trade distributor allows you to cease focusing your efforts on selling and marketing. But the best way to make this relationship successful for you is to already have a growing audience that is eager to get its hands on your books from all kinds of outlets.

That means: Distribution is not a substitute for building an audience. It’s tempting to assume that once your books are widely available via trade distribution, readers will organically discover them. But that’s not how it works.

Just World Books, a leftist publisher of global affairs distributed by IPG, has created an effective strategy for convincing stores to stock its titles. They consistently and effectively encourage their fans that support their political mission to march into independent bookstores to buy their books. This direct influence to drive customers to stores gives stores a great reason to stock their books.

Laura Stanfill of Forest Avenue Press says, “As we grew, I realized that we were spending so much time and money on marketing our titles that having them available regionally wasn’t sustainable. We needed to make our books more available nationally—and not just by print-on-demand, which has high overhead, low economy of scale, and doesn’t really convince random booksellers to order copies unless there was some sort of local connection we could bring to their attention.

“When we accepted Ellen Urbani’s novel, Landfall, set during Hurricane Katrina, I knew we would need southern bookseller buy-in, and, for that, we needed a distributor with a sales team that could reach the South. I began looking, soon realizing I didn’t print the five or so titles per year required to qualify for most trade distributors. Then I discovered a newer boutique distributor, Legato Publishers Group, a sister company to Publishers Group West (PGW). I sent some books to the president, he liked what he saw, we met for breakfast when he was on a business trip, and then his sales team watched me interact with booksellers at a local trade show a few weeks later. I’ve been with that team ever since.”

Eventually Adam Gamble, founder of Good Night Books, went to a distributor to keep up with his own success. “I just don’t see how a small press can afford to do all that a traditional trade distributor does, without it being even more expensive. Really, I don’t see much choice for publishers, unless they want to spend huge amounts of time and money dealing with issues of billing, collections, fulfillment and sales.” Good Night signed with Independent Publishers Group (IPG) and handed over their lucrative gift sales accounts to IPG’s sales team, who continued to grow these relationships and sales.

Still, distribution is not everything. Laura Stanfill learned many lessons along the way. “Distribution definitely has surprised me in terms of the inability to predict returns; that may get better as I have more titles out, and a better set of numbers to help me project, but with fiction it’s always variable. But I do know, for sure, every time we publish a book, our reps are selling it into stores across the U.S.—and a lot of small-press publishers and micro publishers don’t have that kind of reach. I have found that one of my top obligations as a publisher of a distributed press is to constantly ask myself how readers in a certain city or town will hear about our book and want to order it. With nonfiction, that’s subject-based, but with fiction, it’s a mix of getting the right reviews, creating events, making the book available in galleys to churn up interest, having eye-catching covers, picking the right sales descriptions and phrases, and building a brand that is recognizable by readers.”

To reach an audience:

You need to be clever—more clever than the other people who are doing what you do.

You need to spell out exactly what the book is.

You need to have an online presence that appeals to your reader base.

You need to work hard to promote your book through traditional media as well as more creative channels.

You need to find ways to interact with your readers and keep them invested in your output and success.

You don’t need a trade distributor to do any of these things—good ones that are a good match for your work will do them, but not as well as you can and not in a way that replaces your own efforts. A trade distributor can expand your reach, but if you haven’t yet built up a way to connect with your audience, that expanded reach may not stick or be sustainable.

A distributor doesn’t always have congruent goals with a publisher due to their economy of scale. It’s a physical impossibility to show every book to every buyer or even to put every book in every catalog. It’s impossible to answer every email, and, in the end, corners must be cut and decisions must be made. Again, a distributor’s goal is not always your goal. Your distributor can make money through storing your books, shipping and processing returns of your books, and the various aspects of managing data and inventory that goes into publishing—without ever actually selling any books. You have to evaluate when your goals are in sync and when they are not. Someday maybe you’ll outgrow your first trade distributor and collaborate with someone else. Or maybe you’ll find that you preferred (or have a better bottom line) being smaller and getting more personal mail and doing fulfillment for some stores selectively.

A distributor doesn’t always have congruent goals with a publisher due to their economy of scale. It’s a physical impossibility to show every book to every buyer or even to put every book in every catalog. It’s impossible to answer every email, and, in the end, corners must be cut and decisions must be made. Again, a distributor’s goal is not always your goal. Your distributor can make money through storing your books, shipping and processing returns of your books, and the various aspects of managing data and inventory that goes into publishing—without ever actually selling any books. You have to evaluate when your goals are in sync and when they are not. Someday maybe you’ll outgrow your first trade distributor and collaborate with someone else. Or maybe you’ll find that you preferred (or have a better bottom line) being smaller and getting more personal mail and doing fulfillment for some stores selectively.

No matter what, the bottom line is that your job as a publisher is first and foremost connecting readers to reading. Evaluate if and when a distributor makes sense towards those goals for you or how to best reach your most important customer, the readers.

If you found this post helpful, I recommend A People’s Guide to Publishing: Building a Successful, Sustainable, Meaningful Book Business From the Ground Up.

August 13, 2018

Nonfiction Writers: Beware the Curse of Knowledge

Today’s guest post is excerpted from Writing to Be Understood by Anne Janzer (@AnneJanzer) a professional writer who has worked with more than one hundred technology companies, writing in the voice of countless brands and corporate executives.

Few of your readers care about what you know, no matter how many years you have spent accumulating that wisdom. They care about what they need or want to understand.

You share much in common with your readers: you both live a world with numerous, competing demands on your attention, limited time for “deep reading,” and perhaps a longing for simplicity and clarity.

How do you provide the right amount of information without either oversimplifying the subject or overloading the reader? You’ll have to decide what to include and what to leave out. The more you love your subject, the harder this decision can be.

Beware the curse of knowledge

Think of a well-known, familiar song, like “Happy Birthday” or “Jingle Bells.” Sing it to yourself in your head. Then, find a friend and ask them to guess the song as you tap out its rhythm.

You won’t expect them to get it right away, but you might be surprised and frustrated by how long it takes them to correctly guess the tune rattling around in your head. At least, that’s what psychologist Elizabeth Newton found when she tested this very thing.

In 1990, Newton was a graduate student in psychology at Stanford University. She conducted an experiment in which half of the participants (the tappers) were asked to tap out the rhythms of common songs, while the other half (the listeners) guessed the songs. The tappers estimated how long it would take the listeners to name the right tune.

The people tapping were inevitably surprised by the listeners’ inability to hear the tune that matched the rhythm. It seemed obvious to the tappers. This study illustrates a phenomenon known as the curse of knowledge, or the challenge of getting out of our own heads.

Once we know something, it’s difficult to remember not knowing it. We take our knowledge for granted.

We can spot other people suffering from the curse of knowledge pretty easily. We’ve all seen it:

The physician who speaks in medical terms you don’t know

The academic author who writes a paper, intended for a general audience, filled with terms that only a graduate student would understand

These people aren’t trying to hoodwink or confuse you. They simply forget that you don’t know what they know. It’s much harder to detect symptoms of this tendency in our own behavior. When smart, caring people write incomprehensible stuff, the curse of knowledge is usually to blame. It plagues experts who write for the layperson, or the industry insider addressing an outsider. Of course, a few knowledgeable and expert communicators avoid the curse of knowledge with apparent ease, but let’s consider them outliers and confess that the rest of us struggle with it. The greater your knowledge, the stronger the curse.

Nonfiction writers confront this problem in many phases of the work. For example, we cannot proofread our own work effectively because we already “know” what’s on the page. We use terminology that readers don’t know because it is habitual to us. You can defeat the curse of knowledge during later phases of the work by enlisting others for editing and proofreading. But you must avoid the curse earlier still, when deciding what to cover and how to approach it. Get outside your own head.

Go wide or go deep

Before you write a single word, you face a fundamental decision about exactly what you want and need to cover. Answer these three questions.

Breadth: Will you cover a single issue or a wide range of topics?

Depth: Should you dive into details? How many are necessary?

Background: How much does the reader already know, and how much will you need to backfill?

These decisions depend almost entirely on your readers. For a distinct, well-defined audience, you may be able to cover a wider range of concepts related to your topic. When addressing a general audience, you may choose to focus on the most important things, and avoid excessive detail.

The final form also matters. A book gives you more room to roam; readers expect a greater breadth or depth of coverage.

If you are expert in a topic, you may choose to cover it in great detail. For example, masterful biographers like Doris Kearns Goodwin and Walter Isaacson do deep dives into their subjects’ lives, creating works that span several hundred pages. If that’s your approach, you will need to dedicate time and effort to maintaining the reader’s interest. The depth of a treatment can narrow the potential audience of readers.

For some books, breadth is part of the essential value, as in Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Astrophysics for People in a Hurry. As the title promises, it describes a massive topic in a slim volume. Tyson went wide, not deep. Writing about complex topics effectively at this level is a rare skill. Tyson deploys analogies with care, frames the content in a human context, and shares his personal enthusiasm and sense of wonder to guide the reader through the universe. The book is a masterful example of writing about a complex and abstract topic.

There’s no easy answer to the question of how broad or deep your treatment should be. It depends on your purposes and the needs of your audience.

Self-indulgent writers include everything they feel like covering. Thoughtful writers who seek to be understood focus on fit and purpose. Sometimes you have to let things go or put them aside for another project. Focus on serving your reader.

Simplicity vs. oversimplification

Designers, businesspeople, and others often refer to of the KISS principle, which is an acronym for Keep It Simple, Stupid.

As a design philosophy, Keep It Simple, Stupid makes sense. Don’t create systems that are more complex than necessary. However, people mistakenly apply the KISS mantra as a filter in other fields, including political messaging, sales materials, and descriptions of technology.

Simplicity isn’t always the answer. The KISS mantra can become a convenient excuse for hiding complexity that you would rather people not see, such as:

Removing transparency from investments, because investors don’t need to know the possible risks

Not disclosing details of policies because voters won’t bother with the fine print

Not communicating to patients the complete range of treatment options available or the potential risks of a recommended course of action, for fear of delaying the preferred course of treatment.

Taken to the extreme, the KISS mantra shields us from the complexity that we should understand. Certain readers crave simplistic explanations or easy answers that spare them the cognitive work of understanding things that don’t hold their interest. Others, however, may suspect that you’re hiding important details or talking down to them.

When explaining complicated topics, beware of the boundary between simplicity and oversimplification. We want to believe that the world is simple enough for us to understand. We like to think that we don’t need layers of experts arbitrating between reality and ourselves, but when we ignore the true complexity of situations, we can inadvertently mislead readers.

Sabine Hossenfelder has heard some pretty wild theories about physics—hypotheses that she believes arise from the oversimplification of scientific topics for the general public. Hossenfelder is a theoretical physicist at the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies, and writes about physics for publications like Forbes and Scientific American. She is also author of the book Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray.

Her insight into the dangers of oversimplification, however, arises from years spent running a “Talk to a Scientist” consulting service, which she started as a graduate student and still maintains today on her blog, BackReaction. For a small fee, members of the public can pose questions about physics, neuroscience, geology, and other topics, or submit their own ideas about physics. Those theories are creative, interesting, and often not grounded in scientific reality.

She blames this, in part, on the tendency of journalists covering the field to simplify the message so much that they mislead readers.

In describing the experience of running the physics help line, she reports, “The most important lesson I’ve learned is that journalists are so successful at making physics seem not so complicated that many readers come away with the impression that they can easily do it themselves. How can we blame them for not knowing what it takes if we never tell them?”

Deciding what to include

Deciding what to cover and what to leave out challenges everyone. Writers, speaking coaches, and others share their advice about striking the right balance.

When you’re an insider in an industry, seek advice from those who are outsiders. Just make sure you find the right people to ask.

Linda Popky could be considered a Silicon Valley insider. She was named a Top 100 Women of Influence by the Silicon Valley/San Jose Business Journal, and works with tech companies as the founder and president of Leverage2Market Associates. She’s also the author of the book Marketing Above the Noise: Achieve Strategic Advantage with Marketing That Matters.

When writing about topics in which she has expertise, Popky takes care to counteract her insider status. “There are two dangers to knowing your subject matter well. First, you think everyone else knows it already, and as a result, no one understands what you write. Or, you think that nobody knows this stuff, and you go into excruciating detail.”

She handles the situation by finding other people to give her an outsider’s perspective. The key, says Popky, is getting feedback from the right individuals. “You need people who understand the audience and provide the right level of feedback at the right time. Find individuals who can express themselves and identify when something doesn’t work for them. They need the honesty to say if something is confusing.”

She handles the situation by finding other people to give her an outsider’s perspective. The key, says Popky, is getting feedback from the right individuals. “You need people who understand the audience and provide the right level of feedback at the right time. Find individuals who can express themselves and identify when something doesn’t work for them. They need the honesty to say if something is confusing.”

If you found this post helpful, check out Writing to Be Understood by Anne Janzer.

August 7, 2018

Fix Your Story By Focusing on Place

About a year ago, I formed a small writing group that meets every month to discuss each other’s works-in-progress. One of the group members reliably asks, for nearly every piece, questions about the setting. Oftentimes, even if the piece is fairly clear about where the action is taking place, there is missing context or grounding detail about the environment.

Hearing those questions frequently has, of course, sparked me to ask them pre-emptively when crafting my own work—to take the setting more seriously as a character in and of itself.

I was reminded of this recently when reading Marian Crotty’s piece for Glimmer Train, Committing to Place. She writes:

For beginning fiction writers, focusing on place is one of the easiest ways to improve stories that aren’t quite working. Doing so requires almost no imagination—simply looking closely, paying attention, mining your memory and/or conducting research. Paying attention to place, though, often addresses many of the common problems that plague the early stories of beginning writers—lack of detail and specificity, unrealistic characters and situations, and reliance on factual information that taxes readers instead of creating a sharp, sensory world that can simply be experienced.

Also this month in Glimmer Train:

Notes on Writing by Laura Furman

August 6, 2018

Resolving My Cheater Shame: Listening to Books Instead of Reading Them

Today’s guest post is by author Kristen Tsetsi, who is a regular contributor to this site through the 5 On series.

When I told my husband, Ian, several weeks ago that I’d finished reading Andre Dubus III’s Townie, I corrected myself by hastily adding air quotes.

“I mean, finished listening to it,” I said, feeling like a poseur.

“Whatever,” he said. “Same thing.”

“You think?” The hope in my voice was embarrassing. I so wanted them to be the same, wanted to be authentically “well read.” Surely, though, the passive act of being read to by someone who’d decided for every listener where to inflect and what tone to apply to each line of dialogue wasn’t the same as determining those things for myself.

Author Betsy Robinson confirms the value disparity between reading and listening in her Publisher’s Weekly piece, “Look, Read, Listen.” In it, she cites the research of cognitive psychologist Sebastian Wren, who found that reading uses more of the brain than does listening. When listening, Wren claims, we don’t use our occipital cortex to visualize as we do when reading.

Cognitive psychologist Daniel T. Willingham, “Ask the Cognitive Scientist” columnist for American Educator magazine and author of The Reading Mind, among others, notes another difference: “[Reading] requires decoding and [listening] doesn’t.”

“Reading” it would be, then, air quotes and all.

(But only with Ian. No one else had to know I was cheating to build my “read” list.)

I’ve been air-quoting “reading” since my first legitimate introduction to audiobooks this past winter. Before then, the only time I’d heard a book—well, part of a book—was in a hot car during a summer visit to Minnesota in the eighties. It had put thirteen-year-old me to sleep, and so it had also put me off audiobooks. But exactly thirty years later, Ian would get an Audible account to ease the pain of stop-and-go work commute traffic, and not long after that, on a drive to Litchfield, Connecticut to do some Christmas shopping, he’d convince me to listen to J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy.

I warned him that I might fall asleep.

I didn’t. I was captivated, fully immersed in the narrative flooding the car as we slipped into the snowy beauty of a winding country road.

After our Christmas shopping, Ian pulled into the garage, turned off the engine, and still had the rest of Hillbilly Elegy to listen to the next time he got behind the wheel.

I had no Hillbilly Elegy, and I suddenly very much wanted not only Hillbilly Elegy, but other books. I’d had so little time for reading for such a long time that listening to a story unfold had made me realize how desperately I’d been missing the electrifying magic of other people’s words.

Too, audiobooks had worked so well for Ian and his traffic problem that I thought they might kill the monotony of the twice daily dog walks I’d been taking for two years. Music wasn’t cutting it, anymore. As audible scenery went it held all the excitement of the dull evergreen shrubs Lenny and I passed on Hackmatack every afternoon.

I added the Audible app to my phone and chose my first book, watching with Christmas-morning impatience as the files downloaded, downloaded.

The first month of mobile “reading” was dedicated to some books Ian had already bought. Barry Eisler’s John Rain series filled my head for weeks, Eisler’s voice accompanying me as Lenny and I stepped through and over Hackmatack’s sidewalk snow.

Because Eisler reads his own novels (and with such skill that AudioFile Magazine has twice awarded him the Earphones Award), while I may have been denied the freedom of my own interpretations, I was at least hearing the words in the precise way the author intended. It was no different from being at a (very) long author event, really, which even literature professors would agree is an acceptable way to be read to.

When my Eisler stash was gone I considered other fiction, but I chose nonfiction, instead, believing listening to it would be not only educational, and therefore justified, but also every bit as harmless as listening to authors read their own work. After all, how many literary or tonal nuances could possibly grace the biography of Walter Cronkite? Or the history of human evolution, as chronicled in Sapiens?

My first exposure to a novel read by someone other than the author came only after I’d exhausted the list of available, and interesting (to me), nonfiction. In a “why not?” moment of reckless abandon, I downloaded Liane Moriarity’s The Husband’s Secret.

Reader Caroline Lee was utterly fantastic. By the time I finished, I was ready to listen to virtual stacks of novels not read by their authors, and one after another they engrossed and delighted. I was insatiable!

And then came a jarring confrontation with the other power of a voice.

The book’s synopsis promised a suspenseful page turner. I pressed “play” the moment I stepped outside with Lenny. As the woman read, I noticed that my pace slowed. Five minutes in, I was getting distracted by things to kick on the sidewalk—acorns, small rocks, a clump of dirt. Ten minutes in, I yawned, bored almost to the point of feeling anxious by the slow, spiritless voice in my ear buds. I pressed “pause,” switched apps, and listened to music.

There, then, was another critical difference between reading and listening: the wrong voice/tone/energy could murder an otherwise absorbing book.

I was thinking about the unfairness of it all—poor writers, losing readers for reasons other than the writing!—when author Ian Thomas Healy, in the course of my 5 On interview with him, suggested that I have my own novel adapted into an audiobook. He’d had a few of his adapted, he said, and he’d seen an increase in sales as a result.

“Reading” someone else’s work, pressing “pause” and returning a book if I didn’t like the voice or reading style, was one thing, but I certainly didn’t want anyone doing that with my book.

I also shared Betsy Robinson’s sentiments about the desired nature of the writer/reader relationship: “[W]hen I spend four years honing a novel, I’m not imagining some intermediating interpreter conveying it to a reader,” she writes in “Look, Read, Listen.”

When I ultimately decided to go ahead with the audiobook, it was because of the important words Healy had used: “increase in sales.” I swallowed any discomfort—discomfort that can pull like sickness when it’s a fear of your hard work being misrepresented—and began the process.

In the months since, the audiobook has been published and I’ve thought a lot about the artistic conversion from text to voice. While Willingham does say reading requires more decoding from the reader than does listening, he adds, however, that “…most of what you listen to is not that complicated. For most books, for most purposes, listening and reading are more or less the same thing.”

Decoding is more important for those learning to read, he explains. Those who have been reading for some time are generally already fluent at it.

Well, whew! That eliminated some of my own cheater guilt, but as it happens, listening to a novel is valuable even for those who don’t read text well. Educational website Reading Rockets lists among the benefits of listening to audiobooks that listeners gain access to work above their skill level, they’re given a model for interpretive reading, and they’re more likely to explore new genres.