Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 93

May 15, 2019

Why Read Women Writers? An Interview with Bill Wolfe

While scrolling through my Facebook feed some years ago, I came across a link to Bill Wolfe’s website, Read Her Like an Open Book. Someone had posted a link to a book review he’d written, and I’d clicked on it, finding myself at a website dedicated to reviewing and showcasing books by women.

As a female writer, I admittedly find myself rolling my eyes when males express surprise if they’ve enjoyed a novel by a woman, or when they brazenly don’t accept that men and women (and everyone in between) are equally competent writers, so I naturally thought Bill Wolfe’s book review blog was a refreshing idea. Who better than a man to persuade other men that women’s books are worth their time? (After all, men who refuse to read women certainly aren’t likely to listen to any woman who tells them they should.)

When Bill recently appeared in my feed again—this time in the form of a link to his interview with author Kali Fajardo-Anstine about her short story collection Sabrina & Corina—I was suddenly curious about the “why” of his website. Why was he focused on women’s writing? Why put so much time into it? Why (from his perspective) impress upon men that they should read women?

He was gracious enough to answer those questions and more.

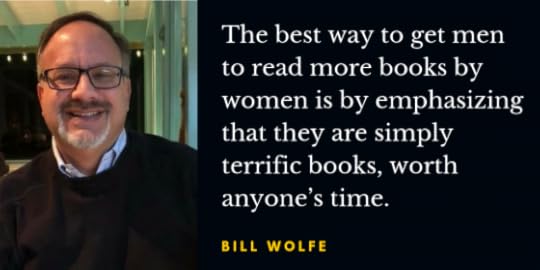

Bill Wolfe taught high school English for 19 years in the Bakersfield, California area. He was named District Teacher of the Year in 2005. He also taught Journalism and coached the Mock Trial team for a time. Before teaching, Bill practiced law in Los Angeles and Bakersfield. He earned a BA in English, magna cum laude, from California State University, Northridge and a Juris Doctor degree from Loyola Law School in Los Angeles. Bill began blogging in 2013 and started a photography business, Inner Light Photography, in 2015. Currently, he is a freelance editor and writer. He is married and the father of two sons (27 and 22). He lives in Shafter, California.

KRISTEN TSETSI: You explain the purpose of Read Her Like an Open Book on your “About” page like this:

It’s “common knowledge” that men don’t read books by women. But the truth is a little more complex; in fact, some men do read books by female authors. But in my experience, I seem to be a relatively rare creature: a man who not only reads many novels by women but often prefers them. […] Perhaps my perspective on literary fiction by women will be of interest to other readers, writers, and publishers. And maybe, just maybe, I will be able to convince some other men to pick up a novel with a woman’s name on the cover.

I shared a link to that “About” page on Facebook, and I received the following responses: “I don’t think I will ever truly understand this concern about the gender of an author,” wrote Person One, a male. Person Two, a female, wrote, “I’m annoyed anyone finds this relevant to blog about in 2019.”

You started the blog in 2013. Do you think it’s still necessary today to try to encourage men to read women, or to shine a targeted light on female writers, or have you seen any changes in men’s reading habits over the last five years?

BILL WOLFE: Yes, I think it’s still necessary and worthwhile to try to encourage men to broaden their reading to include more books by women, whether fiction or nonfiction.

Men claim they don’t pay attention to gender, and in a sense they’re right. But they tend to read in genres dominated by men, like history, biography, and genre fiction like sci-fi/fantasy and mystery/thriller. Ask most men who their favorite writers are, and you’ll hear few if any women’s names.

The comments your Facebook post received suggest a naiveté. It reminds me of people who can’t understand why people are “concerned” about things like racism, misogyny, and gender-related issues. I mean, it’s 2019! Aren’t we beyond that? As if 2019 is some kind of magical date beyond which all social ills are nonexistent.

I should add that there is a small percentage of men, who read a lot of literary fiction and might be considered “bookish” in that regard, who do read plenty of books by women. But I’m still convinced that the majority of men wouldn’t want to be caught dead reading a book with a woman’s name on the cover.

Sadly, publishers often don’t help this situation, because the cover design of much literary fiction by women is still directed at women readers. You know, the back of a woman looking out a window or standing on the beach looking out to sea, etc.

You further explain on your “About” page:

“I have always been more interested in realistic fiction that addresses the human condition and relationships than in the genre fiction most men read (thrillers, mysteries, military strategy, sci-fi, fantasy, etc.). I’m sure being an English major had something to do with it.”

That’s interesting to me, because as an English major myself, and then a creative writing student in the early 2000s, although we certainly read those same women, we were probably introduced—at least in courses not titled “Women in Literature”—to a heavier load of male writers of realistic fiction that addresses the human condition: Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, Cormac McCarthy, J.D. Salinger, George Orwell, Kurt Vonnegut, William Golding, Henry James, etc. (etc., etc.).

I know I, at least, spent my college years believing that outside of a handful of female authors, only men were the “real,” “serious” literary writers. (Movies would still have us believe this, by the way.)

So, how did you come to be more interested in the literary writing women are currently publishing than in the literary writing men are currently producing?

I read most of those authors in college, as well. I came to contemporary women writers in the ’90s, when Jane Smiley, Barbara Kingsolver, Toni Morrison, Louise Erdrich, and Alice Munro seemed to be much more visible. There was something in their sensibility that was different from that of the male authors, even if the subjects were similar (say, divorce or parenthood or the lifespan of a relationship).

I think the main appeal was simply getting the female perspective for a change. I’m a man, and I think I know how men generally feel about a lot of things. (Maybe that’s my fundamental problem right there; I’m arrogant in believing that.) And then, as something of a feminist (depending on how one defines that word), I became interested in promoting the women writers I liked.

As an English teacher, were you permitted to select the stories/novels your students studied? If so, what did you select? If not, what were they assigned, what was the male/female ratio, and if mostly male, how did you feel about that? Did you find a way to incorporate more female writers?

We were permitted to choose a book occasionally, usually from among a group of 3-5 books the department had approved. (For example, in 12th grade English, we had a Cultural Perspectives Unit in which students could choose one of five books for an outside project. The choices included The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan, The Bean Trees by Barbara Kingsolver, and A Lesson Before Dying by Ernest Gaines, among others.)

I didn’t object to this because I thought the required reading choices were very good, if a bit traditional. We were trying to introduce students to works that stood out for their literary value but that had also become part of the culture.

Those two criteria did result in a male-heavy reading list, but I worked in a lot of women through our free reading program. We were given $300 each year to buy books at the local Barnes & Noble (with the Educator discount of 20%, of course) to add to our classroom library, and most of the books I bought were by women (lots of mature YA, contemporary literary fiction with a high-interest level for teens, and a few classics).

As I was compiling these questions, I happened upon a link to a New Republic article about David O. Dowling’s A Delicate Aggression: Savagery and Survival in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Maggie Doherty writes in the article, “The experiences compiled in A Delicate Aggression help us better understand not just the history of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, but more generally a literary history in which women’s voices have been discouraged, ignored, or suppressed.”

As I was compiling these questions, I happened upon a link to a New Republic article about David O. Dowling’s A Delicate Aggression: Savagery and Survival in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Maggie Doherty writes in the article, “The experiences compiled in A Delicate Aggression help us better understand not just the history of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, but more generally a literary history in which women’s voices have been discouraged, ignored, or suppressed.”

I thought, “Well, surely the publishing industry has since improved in that respect.” But then I came across The Male Glance: How We Fail to Take Women’s Stories Seriously, published just last year in The Guardian, in which Lili Loofbourow observes, “Generations of forgetting to zoom into female experience aren’t easily shrugged off, however noble our intentions, and the upshot is that we still don’t expect female texts to have universal things to say.”

You write on your website, “Perhaps my perspective on literary fiction by women will be of interest to other readers, writers, and publishers.” You also specify that you don’t consider self-published fiction for review.

But if publishers traditionally show less interest in literature by women, thereby leading more women to self-publish, isn’t there a chance that drawing publishers’ attention to quality self-published literature by women might help publishers look at literary manuscripts not written by men with a more interested eye?

Yes, I think writing about self-published fiction could help attract the attention of a publisher.

But my concern with self-published books is that the lack of a gatekeeper, whether it’s an agent or an editor, largely eliminates quality control. Anyone can self-publish anything. It means something when someone with experience and a discerning mind believes that a book is worthwhile. The few self-published works I’ve read needed that kind of mind to guide the writer through revisions and improvements. It was a little like listening to demo versions of songs. You can tell there is potential, but it’s still pretty rough and needs a lot of polishing.

I’m a little selfish with my reading time in the sense that I want to read books that have been cultivated to the point that they’ve reached their full potential.

Two comments left by a single reader after your “About” page explanation of why you read women include the following: “I suppose to be an active participant within the current societies of the human race, one would read women writers as well as male. [Next comment, same author] I, unfortunately, fall into the category of men who read men but [my wife] is more likely to follow your site about women.”

What would you say to men who will say they agree that the voices of men and women are equally important but, in the same breath, admit to not being interested in the voices of women?

I would say that they’re not as interested in women’s voices as they say they are.

How can you be interested in someone’s perspective but not read or listen to them? I would ask this man why he reads only/mostly men. What is he seeking that he finds in books by men and that he assumes he won’t find in books by women?

The answer should be revealing. Part of the “problem” is that most people read primarily for entertainment and take the path of least resistance: a beach book, an airplane read, something fast and fun. That shows a misunderstanding of literary or serious fiction—thinking that it must be difficult, a slow read, work.

That’s why in my reviews I emphasize the reading experience, rather than focusing on the female perspective, why the issues in the book should interest men, etc. I take a reader’s approach, not a scholarly or theoretical approach.

I think the best way to get men to read more books by women is by emphasizing that they are simply terrific books, worth anyone’s time. Then, when they read the book, they’ll find the other things that give it both a distinctly female perspective and universal value. Infiltrate and double-cross!

Thank you, Bill.

May 13, 2019

How to Plan a Book Reading That Delights Your Audience

Photo credit: Ian Muttoo on Visual hunt / CC BY-SA

Today’s guest post is an excerpt from the writer’s guide book How to Read for an Audience: The Stuff Nobody Teaches You, co-authored by public speaking coach and creative mentor James Navé (@JamesNave) and author and workshop leader Allegra Huston (@allegrahuston).

When you’re nervous about reading in public, you tend to picture the audience as the enemy, distant and judgmental, just waiting for you to mess up. If you think about this for a moment, you’ll realize that it’s an illusion born of fear. In fact, your audience wants to love you and your work. Some of these people probably already do.

The audience is on your side. They love writing just as you do; that’s why they’re there. These wonderful people have taken time out of their lives, probably traveled some distance and spent some money, just to hear you read. They’ve come to witness your imagination at work. They’ve come to be moved, entertained, motivated, validated, informed, provoked, stimulated and inspired. In short, they’re receptive.

They are your allies.

So, what are you going to read? Here are things to keep in mind as you make your selection.

Crafting an emotional connection

The strongest impact you can make when reading aloud is emotional, not intellectual. For that reason, you will do best if you choose content you have a strong emotional connection with: passages that make you laugh or cry—if you let yourself.

Pre-select more material than you will have time to read, with a wide emotional range. You’re not a robot. You’re not going to feel the same way every day, or want to read the same material.

Make your final selection on the day of your reading. If you’re going through a difficult time in your personal life, you may want to present material that reflects your emotional state—though if you don’t trust yourself to keep control of your emotions, go with something safer. Include as wide a range of emotion as you can manage—or, if it’s a short reading, choose material that builds to a powerful climax. Either way, take your audience on a journey.

If the event has a theme, take it into account. Even if you have to stretch to make a connection between the material you want to read and the theme, make sure you do. The organizers will not invite you back if you totally ignore the brief they gave you.

If you are one of two or three readers at an event, you will probably have about 20 minutes (more on timing below). Unless you are an expert at this, DO NOT choose one continuous passage or one long poem. You will find it challenging to hold an authentic emotional connection for that long, and your audience’s attention is pretty much guaranteed to wander. Instead, choose poems of varying lengths or three- to six-minute passages from different parts of your book. For an event where you are the sole author reading, select five or six passages or 12-15 poems.

Even though you have been asked to do a reading, it doesn’t mean that all you’re allowed to do is read. You may do better to structure your presentation as a talk about your work.

Timing your reading

After you’ve identified the passages or poems that you might include in your reading, or developed a talk about your writing, the next step is to get an accurate timing. This is where many rookie readers run into trouble. They don’t time their reading in advance, they time it inaccurately, or they decide it’s okay if they run over a bit. Almost always, it’s not okay.

Find out how much time you will have for your reading. Open mic slots run three to six minutes. Curated multi-writer readings allow 10-20 minutes. Solo events can run an hour or more: usually 30-40 minutes of reading followed by an interview and/or a Q&A.

Staying within your allotted time is one of most professional moves you can make. Less is more. If you have 5 minutes, prepare for 3 minutes. If you have 10 minutes, prepare for 8 minutes. If you have 20 minutes, prepare for 16 minutes. The extra time allows for introductory remarks, pauses, off-the-cuff comments, and audience response. If you finish under time, your audience will want more, your fellow readers will appreciate you, and your host will ask you to come back.

If you’ve ever been to an open mic, you’ve almost certainly seen a reader exceed the time limit. This is not only unfair to the other readers, especially those last on the list; it’s unfair to the audience. Some people have come specifically to hear those people who have just been elbowed off the program. Everyone has come to hear a variety of voices. Being greedy, even unintentionally, makes a reader unpopular all around.

We’ve often heard people say, “I only have five minutes. If I read fast, do you think I can get through all five pages?” Sure, it’s possible if you read like an auctioneer, but you’ll lose your audience. It’s always better to read less and read it well.

Time your pieces with the stopwatch on your phone. Begin by reading each piece aloud at what seems to be a normal speed. Chances are it will take longer than you expected. If that’s the case, trim your material rather than speeding up your pace. As you rehearse, your pace is likely to slow down even further, so cut your selections down far enough to give you room to expand.

Editing your material

Many writers don’t realize that they’re “allowed” to make changes to what’s on the page. You can leave out words, sentences, even paragraphs, if that serves the reading. The reading is its own thing: It’s not “a chunk of the book” or legally binding testimony of its contents. It’s an event, and your task is to engage your audience.

What should you leave out?

Wherever possible, omit phrases and sentences that refer to other characters or plot lines that will distract or confuse your audience. And leave out anything that starts to feel inauthentic or clumsy in rehearsal. It happens frequently that you’re happy with a passage when you read it over on the page (perhaps you’ve read it over a hundred times on the page), but when you read it aloud, putting full emotional weight into the words, you realize you’re not happy with it at all. If you’re uncomfortable with even one word, cut or replace it.

Parting advice

When you stand up in front of your audience, you’re making a bargain with them. In return for the effort they’ve made to be there, you will give them an experience of human connection, though the emotions you share may range from ecstasy to hilarity to rage. This sense of shared emotion is why we read. It reminds us that we are not alone, that life is infinitely sad and infinitely sublime, and that there is always something new to fascinate or appall or delight us.

For more insight on reading or performing your written work, check out How to Read for an Audience: The Stuff Nobody Teaches You by James Navé and Allegra Huston.

May 7, 2019

Considering Your Reader Is Not Coddling Them

Writing advice is so often contradictory. Take, for example, the advice to write only for yourself or in service of your vision. But just as often you’ll hear: write with an intended readership in mind.

Neither piece of advice is wrong; they’re just prioritizing different things. Writers who consider themselves “serious” (or literary) tend to emphasize genius and artistry, which can result in challenging or difficult work. Writers who make a living wage from their work tend to emphasize service to the reader.

Of course, there’s usually a middle way; it’s not an either-or proposition every time. I like Stanley Delgado’s essay in the latest Glimmer Train bulletin, There Was a Man in El Salvador Who Owned Four Dogs, where he discusses his grandmother’s method of storytelling. He noticed that she told the same stories differently to him than to his mother—different elements, different drama. He writes:

The man in El Salvador who owned four dogs … and what happens next was based on her audience. And I think it helps to do that, to consider an audience. My grandma’s is an extreme example, but it helps to remember that a story exists to connect one person to another, for however briefly. My mother wanted high drama, I wanted spookiness. Considering an audience—a reader, in my case—doesn’t mean that they are going to be coddled, either, not like in my grandma’s example; considering a reader, to me, simply means realizing the power and weight and authority of words.

Also in this month’s Glimmer Train bulletin:

Patience by Polly Rosenwaike

Deepening Characters by Lee Martin

What Else Can I Tell You? by Ed Allen

This Knotted Labyrinth of Self by Douglas W. Milliken

May 6, 2019

How to Bring Value to Your Readers

Photo credit: Tiomax80 on VisualHunt / CC BY

Today’s guest post by Paulette Perhach (@pauletteperhach) is an excerpt from her book Welcome to the Writer’s Life.

What’s the difference between these two writers: David Sedaris, who people pay fifty dollars to see read out loud for an hour, and the open-mic writer, who is allowed five minutes to read before the timer interrupts him to get off stage? In business speak, the difference is value. Specifically, the power to create value through art.

“Truly reaching your audience and offering them something of value is perhaps as good a definition of successful writing as I’ve ever heard,” says Dinty W. Moore, essayist and writer of both fiction and nonfiction books.

I’m using a word as abstract as “value” for a reason. It’s subjective, and it varies by writer. The value I get from a powerhouse Dorianne Laux poem is totally different from the value I get from a hilarious Sanjiv Bhattacharya essay. Value comes in many flavors. Finding your flavor will be part of finding your voice.

In order to be valuable in the strictly economic sense we’re talking about (all art is valuable to its artist in the more transcendent sense), art has to stir up the insides of the viewer or listener. People pay for the emotional experience art brings them. They pay for the hit of dopamine that a gripping story releases in their brains. When the time and energy they spend reading return only confusion, boredom, or redundancy, readers don’t feel as if they’re getting much value for what they put in, and they put the book back on the shelf.

Until your work becomes art, it’s not doing anything for readers. If a story or poem is not working, it’s literally not working, the same way a drug might not work. It’s as if someone went to score coke and got a bag of baking soda. There’s no emotional value, so people don’t want to trade monetary value for it. If they’ve already traded time and/or money for it, in the form of a book purchase, tickets, or hours, they’ll get annoyed and tweet about it.

In the beginning years, chances are your writing is not art just yet. This is exactly how it should be. And it’s exactly why you’ve got to work on improving your skills if you want to make money from your words.

During the first part of your writing process, the value in the writing is all for you, the writer. You get the relief of getting your feelings out in a rant or the joy of writing a scene that makes you laugh. The act of writing provides value to you.

That does not mean it’s valuable to the reader yet. Most likely, when your friend or your mom or your husband reads your raw writing, it’s not doing anything for them.

How do you make sure what’s valuable to you will be valuable to your readers?

Bust out your tools. Get your red pen and slash away at the adverbs. Get out your plot chart, and make sure your work has stakes. Use your literary devices to lay in rhythm and imagery that please human readers.

People value writing when it entertains, introduces them to characters and cultures they might not otherwise meet, surprises them, paints a character they relate to, or helps them understand a deeper truth they never considered.

There are a thousand ways to make a story valuable, but all of them require work.

Writers who make money with their words offer something readers are happy to give perhaps an hour’s worth of income for—income they could have spent on a martini, a bouquet of dahlias, or a subscription for premium pornography. We pay David Sedaris to read a story in a room with us because he cracks us up and makes us feel good. That’s the particular flavor of value he offers. Some people prefer the value offered by Hubert Selby, Jr. or Anis Mojgani.  Some people find value in watching two people pummel their knuckles into each other’s faces. That is not my flavor.

Some people find value in watching two people pummel their knuckles into each other’s faces. That is not my flavor.

Value is subjective, but it has to be perceived by the reader.

You have to find the people who like the kind of value you think you can create, and work until you figure out how to make it. The longer you practice, learn, and hone your craft, the more value you’ll give your readers, and the more they will be willing to give you to keep you going as a writer.

Copyright 2018 by Paulette Perhach. All rights reserved. Excerpted from Welcome to the Writer’s Life by permission of Sasquatch Books.

May 2, 2019

5 On: Jonathan Westbrook

Writer and graphic designer Jonathan Westbrook discusses what it’s like to win an extraordinary screenwriting contest, what it’s like to have that win fall through, screenwriting vs. novel writing, and more in this 5 On interview.

Jonathan Westbrook (@JonWestbrook) lives in Connecticut with his wife, two daughters, and three fur babies. He holds a degree in graphic design, is a member of the Connecticut Authors and Publishers Association (CAPA), and is a fair-weather golfer. For more information, visit his website.

5 On Writing

KRISTEN TSETSI: What’s the first thing you remember writing creatively?

JONATHAN WESTBROOK: I wrote a Conan-like fantasy with two enemies becoming friends in the end while fighting off a common foe. Unfortunately, one of them died and the other carried him home to enemy territories. When asked why he did it, he said, “Because I fight with my friends,” meaning alongside and not against. It was such a short piece, but my two characters did go through a growth arc. I remember it fondly because it was my first.

The story was written for creative writing class, junior year in high school, so I was about 16. It was only four pages long (handwritten), but I enjoyed the concept of bringing a new world to life, albeit a small one. I don’t remember the grade it received, but it must have been pretty good because my teacher told me she could see me writing a book one day. I didn’t believe her at the time, because this was just another assignment in the doldrums of high school and I had no aspirations back then of becoming a writer. The writing “bug” hadn’t hit me yet, but to this day I often wonder how my own growth arc would have been different had I listened to her.

How similar to or different from that subject matter or area of interest is the material you write now? What has held your attraction/drawn you in a different direction over the years?

During my teens I read a lot of Robert E. Howard and Edgar Rice Burroughs as I was drawn to the lonesome, heroic tales of Conan and Tarzan. And on television, I loved sci-fi shows like Star Trek, The Outer Limits, and The Twilight Zone. I love the strange, the unexplained, the weird tales that spell out the human condition.

My writing is definitely influenced by my past interests; I still love sci-fi and weird tales, which my books reflect. My trilogy: A Legend in Time, Onboard the Marauder, and Future Dark all deal with James Sutherland and his experiences as a time-traveler. My fourth book, Eat My Shorts is a tasty collection of short and flash science fiction, but I believe they all speak of survival. We’re only here for a short time, so let’s make the most of it while we’re here.

My writing is definitely influenced by my past interests; I still love sci-fi and weird tales, which my books reflect. My trilogy: A Legend in Time, Onboard the Marauder, and Future Dark all deal with James Sutherland and his experiences as a time-traveler. My fourth book, Eat My Shorts is a tasty collection of short and flash science fiction, but I believe they all speak of survival. We’re only here for a short time, so let’s make the most of it while we’re here.

My (unproduced) screenplays take on a lighter tone, as four out of seven of them are comedies. I’m not a comedian, but I’m sort of drawn to comedy in my screenplays. Go figure. I guess we all need a laugh once in a while, including myself. I’ve been pitching two of the seven to Hollywood execs; one is a rom-com (think The Wedding Ringer meets Hitch), and the second is a family comedy (think National Lampoon’s Vacation meets Captain Fantastic).

You’re a graphic designer, a writer of screenplays, plays (“coming soon,” your website says), and novels, and you also carve wood. As someone who’s also a husband and father, how and when do you find or make the time for all the creativity ?

By day I also work full-time as a technical illustrator for Pratt & Whitney, an aircraft engine manufacturer in Connecticut. I’m proud to say that my drawings fly all over the world. There aren’t a lot of people who can say this.

In an introduction article written in the CAPA zine, I was called a “Renaissance Man.” I liked that. I like to draw, paint, carve, and write. I get an idea stuck in my head, and I need to express it in one form or another, else I get grumpy.

I was 10 years old when I was first published. It was a drawing of three seagulls in the Kid’s Corner magazine of the Hartford Courant, and I’ve been hooked since. Creating is in my blood, now, but technical illustrating doesn’t always placate my creative needs, so I write whenever I get inspired, at night after everyone has gone to bed (an hour of writing is better than no writing at all, but sometimes I’m just too tired) and on the weekends, where I try to fit it in around family and pets, the chores, and playtime.

I would love to become a quondam illustrator and write full-time some day, but I don’t think that will happen until after I retire. Unless you’ve made a big name for yourself, writing doesn’t always pay the bills.

Your screenplay Language of Love is the one that won the screenplay competition alluded to in this interview’s intro. What is the story about and what inspired it?

Language of Love is a comedy of miscommunication between a man and a woman. It’s a funny look at barriers surrounding love: getting it, understanding it, revealing it, losing it, and finding it all over again. The logline is “A couple discovers the differences in their relationship after an Italian man learns to speak English.”

The story originated from a screenwriting prompt I received from an online class: “Write a story about a relationship where one person no longer wants to be in the relationship.” We had to keep it to four pages, which is very short in screenplay format compared to manuscripts. In screenplays, one page roughly equates to one minute of screen time.

I took the class when I first became interested in screenwriting. I had purchased the correct screenwriting software, but after attempting to convert A Legend in Time into a screenplay, I found that screenwriting is nothing like writing a novel. Think about it–when you’re watching a movie, there are only two things to stimulate your senses: sight and sound. That is all there should be in a screenplay.

When I entered Language of Love into the contest, it was nothing more than, “Oh, hey, I have a one-setting short I could use.” I wasn’t looking for a vehicle for the screenplay. I just happened across the contest online and figured I’d give it a try. Sometimes lightning strikes and sometimes it doesn’t. The trick is to keep trying.

If you had to choose a favorite movie based on the writing alone–y ou’re selecting from a stack of scripts–what would it be, and why? Would your favorite be different if you were choosing a produced film?

Before I started writing screenplays, I took the time to read a lot of them. If you wish to be a writer, you must first read, yes?

There are tons of screenplays available on the internet, and I’ve found that screenwriters have their own style, just like novelists do. Some can be prosy, and others are bare-boned and straight to the point. Some have a defined subtext while others veer off in distracting tangents, or they’re so subtle that the subtext is almost missed.

I have favorites just like I do with the books–Silence of the Lambs, Die Hard, and A Few Good Men to name a few.

But to answer the question, if I had to choose just one screenplay based on the writing alone, I’d pick The Princess Bride by William Goldman because he knew the subject matter better than anyone because he had also written the novel.

My favorite movie is quite different. Can you guess it from this quote: “Take your stinking paws off me, you damned dirty ape!”

The Planet of the Apes with Charlton Heston is my most watched movie, but it’s not my favorite screenplay because it took the actors and scenery to bring it to life for me. Sometimes the movie is better than the book (or the way a screenplay is written).

5 On Publishing

In a March 6 public Facebook post, you shared a screenshot of a message informing you that your screenplay, Language of Love, was the grand prize winner of the short-form screenplay competition you’d entered. What were your feelings going into the contest about whether you would win, and what were the first few weeks like for you after the win, including the hours after you found out you won?

My script, albeit short, was going to be made into a movie! I was over the moon!

On March 6, my daughter and I flew home from Florida after spending a few days there celebrating her 10th birthday. She and I were telling her mother all about our trip when I looked at my phone to see that I had won. To my family’s surprise, as well as my own, I jumped up and yelled, “No way!”

The email said, “Your script is imaginative, funny and wildly entertaining.” Wow! What a thrill! But the excitement didn’t stop there.

I was told they wanted to include me in everything, from choosing locations to casting. They invited me to fly out to LA to be on the production set as the script supervisor “overseeing every part of the process and offering input at every turn.”

Holy moly! I couldn’t believe it. When I had entered the contest, I’d hoped that my script would do well, but even when I was told I made the Top 100, I shrugged and said, “That’s nice,” never thinking I would be the winner.

After the initial contact, they told me, “Before we even get into production, though, we need to lock down the script.” They asked me to “punch up” the ending.

You see, my original submission of Language of Love was only four pages, yet I was allowed five pages in the contest. They said I could write that last page as a revision, with complete artistic license to make it “pop.”

“We trust your skillset,” I was told.

So, I sent in four very different revisions, with one of them being my favorite. Everything was going great. We just had to pick one, but which one would they choose?

On March 16, you posted on Facebook, “Everything is happening at once! I’ve sent off my 4 revised endings tonight for my winning screenplay to the film producer to choose from.” Then, on March 28, you wrote, “Everything is upside down in my world now. 3 weeks ago I won a screenwriting contest and now I’m being threatened with a law suit! Welcome to Hollywood!”

I understand there’s not much you can legally say about this, but what can you say about what happened?

How quickly things can change. I went from elation to disappointment to concern seemingly overnight, and I never made it out to LA.

I got stuck in the middle over a contract issue between the sponsor and the owner of the contest, and, unfortunately, I had to decline the prize due to the changed atmosphere surrounding it.

I was hurt. My pride had taken a hit, and my ego became deflated. I thought I had finally opened the door to Hollywood only to have it slammed shut in my face! I wanted to see my name in lights. I wanted the promised IMDb.com writer’s credit. But I wasn’t comfortable signing anything over to anyone and was forced to back away from the whole thing.

Ultimately though, at the end of the day, I’m taking my win as a tally mark in the positive column of storytelling and will continue on.

What are your options with the script now? Can you continue to try to sell it or enter it into other competitions? I imagine the fact that it won the contest has to be a persuasive selling point.

I still own the rights to my script, and I have since entered it into a few more contests. Unfortunately, no one will care if it has won previously. New contests mean new readers/judges, so I’m back where I was before . . . still trying to crack open the door to Hollywood. With any luck, that lightning will strike again.

If not, maybe in the future I’ll rewrite my screenplays into novels.

Why don’t I just do that now? Well, novel writing takes a long time when you’re a part-time writer. At this point in my life, I’m not willing to commit to that lengthy of a project. I started my trilogy when I was first divorced and living alone, so it was a lot easier to become engrossed by it. It was like having a second job, and you need that commitment to make your writing good enough for publication.

Now that I have more balls to juggle, I have chosen screenplays as my creative output. They’re still a lot of “work,” but the time commitment is shorter, 90 pages versus 300.

Having them produced would be icing on the cake, but it’s not a deal breaker to me if they aren’t. I write for me. I tell the stories I want to hear. But it would be a little upsetting if no one besides me ever got to read or see them, so maybe when I retire I’ll convert them into manuscripts. Then I’ll have two sidewalks to hawk my wares on.

Considering the amount of control afforded to a fiction writer—really, the 100% control you have over a majority of your creative pursuits—what has sharing control of/collaborating on a project like a screenplay taught you, either about the process or about yourself as an artist, that you might not have anticipated?

Even though the sponsors gave me “complete artistic license,” they ended up asking me to tweak one of my revisions to create better audience “buzz.” It was fine, I rolled with it because it was only a small tweak of my idea, and it really did make what I had written better.

Screenplays are always going to be a collaboration; it’s the nature of the business. If a production company options your screenplay, don’t think for a minute that it’s not going to change either by your hand or someone else’s, especially when it’s not your money being used to make the film.

And if they suggest to change the story into something you don’t like, well, it’s up to you whether you want to be paid to make those changes. If it were up to me, and I’ve already been paid for the original and they want to pay me more for a rewrite, then I’ll write their story. In this scenario, that’s what writers are paid to do. I wouldn’t have a problem with it.

What advice would you give screenwriters entering their work into competitions for the first time?

Enter your work into as many legitimate contests with written feedback as you can afford (yes, unlike in the literary world, emerging screenwriters have to pay to play).

If interested, I recommend (in no order of preference):

Austin Film Festival

HollyShorts Film Festival

ISA Fast Track Fellowship

Nicholl Fellowships in Screenwriting

PAGE International Screenwriting Awards

Scriptapalooza

Table Read My Screenplay

Put yourself out there. Don’t be afraid to get bruised. Remember that a writer isn’t a writer until someone else has read their words. All that’s left after that is to cross your fingers and hope your words are liked. Being a writer is like parenting. Once they’re out in the world, you hope your children do well wherever they may end up.

Thank you, Jonathan.

May 1, 2019

Getting a Memoir Published in a Difficult Market: Q&A with Margaret McMullan

One of my first creative writing professors in college was Margaret McMullan. While I took several meaningful classes from her, the one I most appreciated was an independent study on creative nonfiction. At the time, there were no university classes offered on the “fourth genre,” and she was willing to put in the extra time to work with me on personal essays (even though she was focused on writing and publishing fiction).

Today marks the publication day of Margaret’s first memoir, Where the Angels Lived. Despite being a published author of multiple novels—and an accomplished essayist—she had a difficult time finding a home for this latest work. The current market can be rather unfriendly to memoirists, unless you’re a celebrity or have landed a plane in the Hudson.

In the following Q&A, we discuss her writing and publishing journey for the book.

You’ve published seven novels, but this is your first memoir. Of course you have an incredible track record of publishing creative nonfiction and journalism—all kinds of articles and essays—and it’s not like you’re inexperienced. But is this memoir something you very deliberately set out to write and publish, or was it more gradual than that?

Where the Angels Lived began as an assignment I did not ask for.

In 2008 I visited Yad Vasham, the Holocaust museum in Israel. I looked up my mother’s maiden name in their Shoah Victims Database and saw a name I did not recognize. I never heard of a Richárd in my mother’s family, and there he was, my relative, on this List of murdered persons.

When I asked the archivist to print out the few lines about Richárd, she told me I was responsible for him and for his memory. She said I was the first to ask about him and that I was responsible for his memory now. She said, “You must remember him in order to honor him.”

When I asked the archivist to print out the few lines about Richárd, she told me I was responsible for him and for his memory. She said I was the first to ask about him and that I was responsible for his memory now. She said, “You must remember him in order to honor him.”

She gave me a form called Page of Testimony, which she said I had to fill out and send back to Yad Vashem, apparently so others could remember Richárd too.

I took the form and I went to a falafel stand outside the museum, drank two beers, and tried to forget what I’d just learned about my Jewish relative from the museum of remembrance.

When I got back home to Evansville, Indiana, I started my research and applied for a Fulbright grant to teach in Pecs, Hungary, Richárd’s home.

So, the idea was to research and collect enough information to write a novel about Richárd. But as I met family members I never knew existed and as I experienced Hungary, my journey became more a part of the story.

Interestingly, surnames come first in Hungary. Whenever Richárd was introduced, he was Engel de Jánosi, Richárd. He was part of a bigger picture. His identity belonged to his family first, and, his surname, Engel means angel. Angels are immortal. His story, like all family stories, goes on forever. The more I researched, the more I understood that Richárd’s story was also my story and my son’s story.

Compared to your novels, you found it more difficult to find a home for this work. Do you have a sense of why publishers were reluctant to get onboard? What did they tell you, if anything?

Here are some of the responses I received from New York publishers:

“Too many upcoming Holocaust books.”

“This was an enjoyable read with a compelling subject. You are a great writer with an interesting story, but just don’t see a wide enough audience.”

“Too close to another title we’re publishing.”

“The themes here—lost family members, a town full of secrets, Margaret’s experience in Hungary compared to her ancestors’ horrible experiences—are all fascinating. I found myself wanting more reporting on the refugee situation to make the ties linking Hungary’s present and past that much more vivid.”

“I’m not sure this book could successfully compete in a crowded marketplace of Holocaust literature.”

“I can’t buy this type of book here.”

One editor invited me to her New York office to say she wasn’t taking the book. Maybe she thought a face-to-face rejection was nicer. It wasn’t.

After that office visit, my agent, Jennie Dunham, took me out to lunch to eat mountains of sushi, our version of getting drunk. Jennie took me on as a client sixteen years ago, and, at lunch, she reminded me how many times my novel In My Mother’s House got rejected. Twenty-three.

Did I want that reminder? No! But she wanted me to put things in perspective. She said she had believed in In My Mother’s House, just as she believed in Where the Angels Lived. But the industry has changed. Back then there were 23 big publishing houses and still others to send to. Now there are less than half as many. She asked me what I wanted to do.

I told her I wanted to get this story out there because I felt it was important. Where the Angels Lived is a deeply personal story of a family betrayed by its own country. The anti-Semitism, the immigrant’s journey resonates more than ever.

“Let’s get this out there, then,” Jennie said. She told me she would try some independent presses with great reputations.

We ordered green tea and talked about my next book.

A few weeks later, we had three offers from three different independent publishers.

Calypso is a nonprofit press typically known for fiction and poetry—and your last book, a novel in stories, is with them. How did they end up becoming the home for your memoir?

Where the Angels Lived is Calypso’s first book of nonfiction, so this publication is extra special.

I’d worked with Calypso editors on Aftermath Lounge, and we got along really well. Robin Davidson, Tony Bonds, Martin Woodside and Piotr Florczyk are an extraordinary group. They are themselves teachers, writers, translators, and academics. Many of them are also former Fulbrighters. They understood Where the Angels Lived, and they were up for the rigorous proof-reading and copy-editing.

Robin is a poet, and I especially appreciated how she was meticulous with every sentence, every word choice. That’s invaluable, and that’s when working with a small press really pays off.

I loved working with Tony because he’s always up for trying something graphically new. When he was working on Aftermath Lounge, I really wanted to put my friend Alan Huffman’s dog on the cover. Tony fit Girl Dog into another picture he already had, making it perfect, green, and menacing for a book about the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

I sent him a ton of pictures and family trees for Where the Angels Lived, all of which he sifted through. He came up with a simple, elegant design.

How would you compare the experience of working with the larger New York publishers (where most of your other work has landed) and working with a nonprofit like Calypso?

I have had remarkable editors at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, St. Martin’s, Picador, and McPherson & Company. Honestly, I have never had a bad experience with an editor. Knock wood.

Small presses don’t provide those nice advances, but they give you lots of love, attention, and tender care.

I work a little harder hawking books, going on the road, giving readings. But I’ve been holed up with this material for about five years, so it’s good for me to reach out to people and say, hey, can I come read at your school/church/synagogue/book group/bar/ for next to nothing?

I’m visiting friends I haven’t seen since college. That’s a long time ago! I’m even hoping to find someplace to give a reading in Georgia just so I can visit my college literature professor, Jim Kissane.

I also find myself reading more about PR and marketing. I turn to pros like you for advice. Otherwise, I’d be clueless.

When you were on your Fulbright in Hungary, I well remember your vivid Facebook posts about the experience, and I now strongly associate that place with you and your family history. And I’m sure I’m not the only one! Even though those posts happened some time ago, has that process led to any noticeable marketing or publishing outcomes for this book?

Fulbright urged us to share as much as we could on social media. They said, Beat the drum! They wanted their organization to be more inviting and user-friendly. They also welcomed family pictures and activities. My husband Pat kept a blog and our son, James, who was 14 at the time took tons of pictures, which I’ve used shamelessly.

I thought I would write a novel about Richárd with my research, but as I posted, and read responses, I realized the facts were more interesting than anything I could make up. To do his story justice, I needed to tell the truth. His truth.

Posting in real time helped me as a researcher. I had an instant timeline, which helped me later, especially when I got bogged down with historical details and back story. I also had the pictures, which helped me recall everything more accurately.

Facebook became a part of the story too. I posted a piece I wrote for The Washington Post and someone shared it on their timeline and it reached someone in Paris who was trying to connect with someone in my family. This person contacted me—she was trying to find out why her aunt never married and who “the love of her life” was, the man she always talked about. His name was Richard, my great uncle, the man I was researching.

We’ve stayed in touch ever since.

Take a closer look at Margaret McMullan’s Where the Angels Lived.

April 29, 2019

Knowing When to Fly: Leaving Your Critique Group

Photo credit: JanetandPhil on Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC-ND

Today’s guest post is by writer and public librarian Lisa Bubert (@lisabubert).

In order to survive, every baby bird must eventually launch from the nest. Imagine that first instinctual leap, the one that comes because it has to, because even a bird, weeks old, knows what must happen for it to thrive. That leap is what it’s like to leave a critique group.

When I was a little baby writer (and, yes, I am still a little baby writer—I believe we are all little baby writers no matter what the future brings), I was a lost girl. I wrote poems at random in notebooks I couldn’t keep track of. I kept an online journal that was intensely personal, a journal that, turns out, was only written for my friends. Once they stopped reading it, I stopped writing it. I was writing a book, a very bad book, and then a short story, a very bad short story, with a fresh, false start each week. I kept at this story for months. No, I never finished it, thank god. In other words, I was completely aimless. That is, until I joined my first critique group.

Typically, it takes a few tries to find the right group for you. I was incredibly lucky to find my group on the first try.

This group met weekly, every Tuesday night at the local library. I joined for a year, dropped out to get my library degree, and came back three years later. I still remember that first session coming back, how terrified I was. The opening pages of my novel shook in my hand. The group read it in silence. I tried not to vomit. Then, the timer went off and critique began.

Reader, they loved it. It was as if no time had passed since my last visit. There was work to be done, but it was work worth doing. “Come back again next week,” they said. And I did, unfailingly, every week for the next three years.

I wrote the entire first draft of my first book with them. I wrote the drafts of the first three short stories I ever published. For years, we shared our work, our successes, our let-downs—and then I moved to Nashville with my husband.

I did immediate Googling and found a couple of critique groups right off. None that met weekly or all that often. None with regulars. None with that same unique center that held me together for so long. I started my own group, somewhat in vain. I knew I was just trying to recreate something that couldn’t be copied. What I’d had was magic. Now it was gone, and I was struggling.

I kept in touch with my old group; we emailed our work back and forth. But I had gone from having others read my work and give me feedback face to face every week to a big black hole that looked strangely like a blank Word doc on my computer screen. I wanted my group back so badly. I wanted anyone to read my work and tell me it was okay, that what I was doing was worthwhile. But now, hundreds of miles away in a new city, the only person to tell me my writing was valuable and important was me.

So I did. I took the leap. (Imagine me, the baby bird.)

I eventually published a short story I had drafted with the group but struggled to finish since leaving them. I was struggling because, ultimately, I was waiting for someone else to tell me it was finished. All this time, I had always waited for permission to submit. Now, I had to give that permission to myself.

I took the story as far as it could go, I figured out what “done” meant to me, and I submitted it, again and again. Six months later, it was accepted for publication at one of the oldest, established print journals in the country. I cried. And then I immediately sent the news to my old group, who were ecstatic.

Since then, I have tested my wings and published more stories in more amazing journals, side by side with writers I admire. I have stopped trying to recreate the exact group I once had but instead focus on finding a handful of readers willing to share their work with me.

Turns out, Nashville does have a burgeoning literary scene, thanks to The Porch, which I joined and now work for. I collected enough writers looking for feedback that we started Draft Chats, a monthly feedback circle held at The Porch headquarters. I still have my original group to lean on when I need them. Like right now—as soon as I finish the draft of this piece, I will be going to our Facebook group to ask if anyone wants to read it. I know there will be takers; there are always at least two.

So how will you know when it’s time to leave your critique group? More important, how will you know when it’s time to go back? Here’s how I break it down:

Use trusted readers on the early drafts.

Those writers in my first critique group know more about me and my process than anyone else in the writing world. They encouraged me when I didn’t have the ability to believe in myself. Even now, years later, they can still see through the blemishes of my early drafts to the concept underneath, even when it’s still a shaky concept for me. So when I have a draft I’m not sure about, or a story that frankly scares me, I turn to them first for feedback. They know how to strengthen my weakened heart.

Use targeted readers on the later drafts.

Since I have been actively collecting writers for feedback, I now have a handful of people in my back pocket I can ask to give specific critiques. One who is great with essays, another with genres, a poet, short story editors, novelists, those with MFAs and those without. I have a perfect feedback reader for nearly every situation.

How do I find these readers? Simple. I offer to trade work. They read my stuff and I read theirs. It becomes very clear to us both if we’re a match for each other’s work or not.

Find your formula for the right amount of feedback.

If there is a piece you’re struggling to finish, it might be because you’ve gotten too much feedback. All readers are different and all experiences are subjective. One reader may notice one issue while another focuses on something completely different. (This is why it’s good to have targeted readers.) If you were to “fix” every issue every reader brings up, you’re guaranteed never to finish the piece, and may even lose what it was you loved about it to begin with. (Remember the story I mentioned restarting every week for months? Yeah.) After years of tinkering, I now have a “formula” I use for feedback:

Draft quickly. Set the piece aside.

Read it later, and write a “clean-up” draft.

Send to trusted readers. This second draft is the one I usually send to my trusted readers. I will either have it read in a critique group setting and or send it to my shortlist of trusted crit buddies.

Receive feedback from trusted readers. Edit.

Send to targeted readers. Re-read, identify the issues I am still struggling with, and send it to targeted readers–usually just one or two other writers who I know will have good insight on the issues.

Take a few more passes.

Make my own final decisions.

Submit.

This process can take days, weeks or several months, depending on how confident I feel about the work. Which means that you must…

Learn how to trust your gut.

This is the hardest part of writing and the part that is most rewarding. This is what separates hobbyists from professionals. And it is only earned through time, practice, and experience. The more you write, the more you receive feedback, the more you are able to discern what works for you and what you like.

This is how you find that elusive voice—it can’t be found if others are constantly speaking. You’ve got to hear it with your own ears. You’ve got to learn how to fly.

Imagine you, baby bird, soaring from the nest.

April 24, 2019

How I Won My Third Essay Contest

Today’s guest post is by writer Tammy Delatorre (@tammydelatorre).

Writing an essay that wins a contest is not an easy task, but it’s not impossible either. I’ve been fortunate enough to win three essay contests, and each time I’ve learned something different about the essay-writing and contest-entry process.

Here are a few things I learned in the process of writing and submitting, “I Am Coming for You,” which ended up winning CutBank’s Montana Prize in Creative Nonfiction.

Be willing to be haunted.

A lot of times something will begin to trouble me. For this essay, I had a general sense this “something” was about my mother. A thought or image of her would rise up in the middle of work or while I was doing something else. Or, it’d be the middle of the night, and I’d finally sit up in bed, realizing thoughts of her were keeping me from sleep. Wasn’t she beautiful? Where’s she now? Did she ever love me?

This haunting began to give me an inkling of where the essay might head. You see, my mother abandoned me in the middle of the night when I was six, a formative incident in my childhood—one that impacted the rest of my life. So, I knew it was something I wanted to explore further on the page.

If you experience such a haunting, welcome it in its unique incantation. Let it keep you up at night; let it speak to you in its own strange language. For me, before the topic of the essay was clear, it spoke to me through my body, and I tried to serve as a tuning fork for its messages. Old wounds, they still haunt—came to me so I wrote that down. And it was true my body was filled with aches from physical injuries long past, but emotional ones as well. The pain wouldn’t let me sleep. Insomnia had always been an issue for me, since I was a child, since my mother left me, I wrote.

This time the insomnia lasted for a while, so I tried to use these waking hours to face down what was really beneath the surface ponderings about my mother, under the sleeplessness, under the pain in my body. Haven’t I already gone through therapy to deal with this? Was there something else that needed unraveling? Then a realization occurred to me. I didn’t really have a hard time falling asleep. I had a hard time staying asleep, and the hour of night when I usually rose was around the same time when I woke and found my mother gone when I was a little girl. Maybe in a sense, my unconscious was forcing me to revisit that dark hour for new information.

Write the fragments as they come.

I decided that when I couldn’t sleep. I would get up and write down whatever came to me. As a young girl, I had buried a lot of emotions, so it was hard to have them rise up and make sense of them, so I’d just write what was right in front of me, hoping understanding would follow. I wrote about the quality of the night. I wrote about going to the gym that day, about working out, about exercising out old demons. I wrote about the soreness of my muscles. I wondered why I pushed myself so hard physically—to the point of pain, to the point of fatigue. And then I wrote this: it makes me feel close to my mother.

Some fragments grew into threads, which I soon realized were related—the pain in my body, the insomnia, my mother leaving me. I added what I could remember of my life around the time she left. I added things I intuited she had done with her body, done with men with her body, and how I had repeated similar behaviors as a woman myself.

I weaved the threads together as best I could. Then one morning, after another night of not much sleep, I was headed to the gym again. I was tired. I was half listening to the radio when a phrase came to me. I said it aloud: “I am coming for you.” The phrase came to me, as if I wanted to go after someone, and then the next thought came: that’s probably what my mother said when she went after that man, the one she kidnapped and tried to kill, and by going after him, she had not come back for me. And if she had done that, could she have loved me? Right there, I had uncovered the structure for my essay, with this consistent refrain in my life. Is anyone coming? Now, I just had to put it together.

Choose a piece you believe in.

The impetus for getting to the crux of this story was strong—I lost my mother in an unusual way, what I saw as a mental health issue, which led her to commit a crime of passion—kidnapping and attempted murder—which landed her in prison. I was willing to come back to the material again and again to explore every facet of losing her, how it affected me, and why it continued to plague me.

I wrote what I remembered of her lover, the man she went after:

a man who knew how to hurt, years of experience honed behind his methods. He didn’t stop and consider; he didn’t plot and scheme. It came natural, fingers that grab and dig, fists that hold, then hit.

Although the situation with my mother was somewhat unique, I knew it would matter to readers because we’ve all experienced loved ones letting us down—sometimes in big ways—and readers would relate to the essay’s central questions: do we ever truly get over it? Do we forgive?

For me, when the haunting began, the answer was no. I had not forgiven her. I’m a Taurus and not a very forgiving person to begin with, but I was also holding onto to the hurt. I was recreating the pain of it, so I could be close to her. I wrote into the essay the various ways I was holding on and why.

And of course, as an adult, I promised my life would be nothing like my mother’s, and yet, when I considered it, in many ways I had followed in her footsteps. I hadn’t committed a crime and gone to prison, but I had been with men like she had, men who didn’t love or care about me, simply used me for my body. Perhaps these men were incapable of love, perhaps that’s why I choose them. Perhaps I had internalized my mother’s behaviors and feelings of being so desperate for love she’d do anything for it.

I had started writing fragments of the essay in August 2016, and by January 2017, I had a pretty good draft. I started to submit the piece out to essay and creative nonfiction contests. Within that first group of 10 submissions, I had received two positive responses. I was a finalist in contests sponsored by New Ohio Review and Black Warrior Review. I felt this was a good sign that the material was resonating with readers.

Get feedback along the way.

Now to discuss a bit of logistics. Every 10 or so submissions, I would bring it back to the re-visioning table. While the essay was recognized as “good,” it had not yet won, so I thought I should get some feedback.

I took the essay to a workshop where I knew I’d be able to read the piece out loud. I wanted every word, every sentence to work at its highest level. I wanted the voice of love and anguish to track. I knew by reading it aloud to a room full of skilled writers (albeit complete strangers), I’d have a good sense for how the material affected them and the places where it lulled.

At the end of my reading, people were quiet at first. Slowly, a few people raised their hands and said things like, “It was powerful…full of pain.” But I also received some feedback on how to make it stronger. And this is the tricky part. Some notes you receive may be clear, and it’ll be easy to make those changes. “You went on too long about the broken bones.” I agreed and simply cut the entire thing. Other pieces of feedback may not provide a simple path forward. One woman said, “What you think is interesting is not necessarily interesting to us.”

Now, I knew what parts she was alluding to as interesting—the parts about my mother going after that man. There’s an inherent sense of danger and impending violence. I also intuited what they felt was less interesting—the child being left. It’s sad, yes, but in comparison, not as engaging.

As the writer and the ultimate arbiter of the essay’s terrain, my goal was to convey my experience in losing my mother and how it affected my life. My goal wasn’t necessarily just to give readers what they wanted, although during the reading I saw how listeners sat at the edge of their seats during the scenes with my mother and that man.

I also knew about the concept of withholding. Theoretically, I could use what I knew the reader found interesting, eke it out slowly, withholding what they wanted to know until the end. And in the meantime, I could get across all the information I wanted to convey, which was the pain and grief of losing my mother in this way.

What I did with the feedback was put it on its head. I made the reader wait to find out what happened to my mother and her lover, while I forced them to sit through what happened to me.

Be willing to cut it up.

By the time I had read my essay out loud at the workshop, I had already been working on this piece for a little over a year, so I immediately “heard” what was wrong with it. That very night I came home and made most of the changes, staying up until 4 a.m.

In this all-night revision session, I used a technique that’s worked for me before. I printed a copy of the essay. Alongside that, I had a pair of scissors and tape. And usually in my storage cabinet—for this very purpose—I kept thick photo paper taped end-to-end in a long sheet. I used the scissors to cut sections, and according to my desired revision, I taped the pieces back together in a way that withheld and disclosed as needed. Any cut-up pieces left on the floor were collected and thrown in the trash.

If you think that’s a time-consuming process, it is. For me, it’s meant to be. My life was in pieces when my mother left me; here I was years later putting the pieces back together.

Be willing to pay for feedback.

After the late-night revision session, the essay still wasn’t quite there. How did I know? The essay was making it to the finalist stage consistently with top-tier literary journals. So, I finally sent the piece to a person who I paid to read it. I knew in paying someone I would receive a fair response to what was on the page—and not necessarily what that reader wanted the story to be (which is what I get a lot of times). The reader said she could see why the essay was making it to the finalist rounds, but she thought the ending fell flat.

Ugh. That was hard feedback to receive. By then, I had been working on the essay for a year and seven months. How could I find a different ending? Hadn’t I explored every possible angle? Hadn’t I added and subtracted to the point that I had nothing left to try?

But then, I remembered something: a dream I had about my mother. It was a dream filled with emotional pain, and I didn’t want to “go there”—which was a good sign I should. Because it came from my subconscious it boiled down to the truth of how I felt. I quickly scribbled out the short scene, and in this particular instance, it was a lot easier to get down than all the energy I had wasted trying to avoid it. And I had finally found my ending because when I submitted it again, it achieved a few more finalists’ recognitions, and then it finally won at CutBank’s Montana Prize for Creative Nonfiction, a literary journal I had long admired and wanted to appear in.

Get encouragement along the way.

I submitted the essay to 36 contests, I was a finalist in seven contests, and won an honorable mention at another. When it finally won, I withdrew it from three contests. Over time, I see the entry fees as money I invest in becoming a better writer. I also learned what publications resonated with my work. The journals that ranked me as a finalist ended up on a short list of literary magazines I knew might appreciate and accept future pieces.

To be able to endure such a long creation and submission process, you need encouragement along the way, from readers whom you trust and value. By “trust,” I mean they won’t inadvertently let a hurtful comment slip, like “So, how many rejections have you received now?” (Imagine the snide tone.) Really? That’s what you want me to focus on rather than all the good feedback I’ve gotten? Those types of people are careless, and their comments will hurt you at times when you may already be feeling low. When you identify those inadvertent hurters, do your best to eliminate them from your creative circle.

By “valued,” I mean your readers should have a high degree of experience in writing, as well as providing feedback that will strengthen your work. Choose a person who feels like a natural coach, who will know what to say and how to push you to make your writing better. They’ll tell you to keep at it, to submit again, to write something different, to look at it upside down, to print it in a different font. No matter what, they’ll encourage you to keep going.

Be persistent.

I developed more than 50 versions of this essay. Believe me, I counted. Some versions had very few edits, but still that’s a lot of drafts. I will usually send an essay out to about 3-5 venues at a time, depending on when deadlines fall. But spacing out submissions gave me time away from the piece. By the time the next set of deadlines rolled around, I conveniently had some distance to look at the piece with fresh eyes to revise and make it stronger.

I also believe that there is magic in sets of 10. If there’s good feedback in the first set of 10 submissions, then you can be assured it’s got potential to be recognized in a contest. It’s just a matter of how persistent you want to be. Along the way, some contests in which I had made it as a finalist asked to publish my piece. This can be a hard decision. For me, I always turned those opportunities down. I didn’t want an essay about my mother—whose story seemed to reside in the very fibers of my muscles—to be sent out into the world for anything less than a top honor. In a way, it was my way to pay tribute to her.

There are other bonuses you don’t want to miss out on. As the winner of a contest, you usually receive a nice prize, maybe $500 to $1000, and the finalist, nada. The winner usually receives a thoughtful quote from the contest judge; the finalist, not so much.

Here is what the essay contest judge, Sarah Gerard, had this to say about my work:

“I Am Coming for You” is a bloody, vivid, gut-wrenching account of inherited violence, abandonment, and reckoning. It’s the kind of story that demands to be told in spite of, or maybe because of, the courage it takes to write it. Rage and sadness pulse through it like a heartbeat through an umbilical cord.

By now, with three essay-contest wins under my belt, I may have developed a sixth sense about the pieces I pursue for contest submission. It takes a little trial and error, and it can be a long journey that doesn’t ensure success. With this piece, I was willing to stay the course because I got to spend time with my mother again, late nights with everything I could remember about her, every memory of her I realized I had never let go of, every scene, a loving devotion. There’s still a bit of mystery around why she did the things she did. Maybe I’ll never fully understand, but in the end, I also found a trace of forgiveness. And to top it off, I received an email from an agent interested in seeing more of my work, and that’s a nice, unexpected bonus indeed.

To read my award-winning essay, obtain a copy of CutBank Issue 89.

April 16, 2019

Beyond Good Writing: Two Literary Agents Discuss What Matters Most

Today’s guest post is a Q&A by Sangeeta Mehta (@sangeeta_editor), a former acquiring editor of children’s books at Little, Brown and Simon & Schuster, who runs her own editorial services company.

Almost anyone who has spent time in the query trenches knows how challenging it is to capture the attention of a literary agent. Most agents, even new agents eager to build their client list, pass on over 90 percent of the queries they receive. In some cases, the reason is obvious: The agent doesn’t represent the writer’s genre; the writer has written a synopsis rather than a query letter; the agent isn’t accepting queries, at all.

In other cases, the writer might be doing everything right—researching agents, following submission guidelines, querying only once they have a polished manuscript—but still experience radio silence. Or, maybe they are receiving requests for pages, or feedback from the agent along with the opportunity to resubmit, but an offer of representation just isn’t coming through. If the writing is good or at least shows potential—how else would they have come this far?—shouldn’t this be enough to land an agent? Does the writer’s professionalism count for something? I asked literary agents Linda Camacho and Jennifer March Soloway. As with all my agent Q&As, neither knew the other’s identity until after they submitted answers to my questions below.

Sangeeta Mehta: Most agents warn that it’s best not to write to the market. By the time the book is written, sold, and published, the trend the writer was trying to capitalize on is usually over. But if you came across a manuscript that speaks to the current zeitgeist, or is at the top of the manuscript wish list (#MSWL) of an acquiring editor you know, would you offer representation, even if the writing isn’t as strong as you’d like?

Linda Camacho: The writing has to speak to me in some way for me to take it on, so if the writing isn’t quite there, I won’t likely offer rep, even if it has a great premise. Because if I didn’t fall for the writing and I took it on solely on the basis of a cool premise, I’ll be reading that manuscript many times as my client and I revise. Working on revisions is no easy task, so if I find the writing “meh” on the first read, I shudder to think at how I’ll feel on the tenth.

On the rare occasion, however, if there’s something special—a spark—in that writing, I might offer feedback and ask that the writer resubmit if those editorial notes make sense to them. If they get back to me later with a revision that has addressed those issues well, then there’s talk of representation.

Jennifer March Soloway: My goal is to have long-term working relationships with my clients. If I fall in love with the writing and voice, and I see great potential, plus I feel I could help the author to polish the story for publication, I might offer representation under those circumstances. But for me, it would be less about the current zeitgeist or an editor’s #MSWL, and more about my personal connection to the story and writing. I have passed on projects with offers of publication in hand when I felt like I wasn’t the right person to champion the project or author.

When evaluating submissions, how much weight do you place on current market expectations? For example, would you automatically pass on a novel written in the omniscient point of view, in spite of the fact that many famous 19th-century novels were written in this style? Similarly, would a moral message or an allegorical approach (also a hallmark of some classics) be a deal breaker for you?

LC: I certainly keep market expectations in mind, as they’re general markers of what is most likely to sell. Still, they’re not the end-all be-all of publishing, and I try to remind myself of that when I’m reading submissions. The market is ever-changing, so what works today is not necessarily what will work tomorrow. Because of the mercurial nature of the market, I am definitely open to working with something considered less marketable.

I’m not personally drawn to an omniscient point of view style, but in that instance, if I started reading and fell in love with that project, I’d still give it a shot. What I’d have to focus on is managing the expectations of the potential client by being upfront about the current marketability of the manuscript. I’d tell the client that, yes, it’ll be a tough sell and it might not make it past an acquisitions board, but that I’d do everything in my power to try and get it out into the world.

JMS: The market is always changing, and it’s impossible to write to the trends. That said, if the market is currently saturated with a particular genre or subgenre, such a project can be difficult to sell. If I think I won’t be able to sell a particular project, I will let the author know I am not the right agent for that project. However, if I like their writing and storytelling, I will ask the author to please keep me in mind for future projects if they do not find representation.