Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 88

October 28, 2019

For Writers, Silence Might Not Be Golden After All

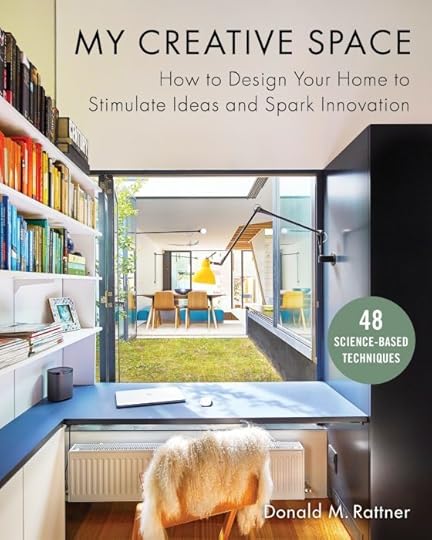

Living area and deck. Architecture and interior design by Mark Dziewulski Architect. Photography by Nico Marques.

Today’s guest post is adapted from My Creative Space: How to Design Your Home to Stimulate Ideas and Spark Innovation, 48 Science-based Techniques by author and architect Donald M. Rattner (@donaldrattner). Illustrations are courtesy of the designers and author.

As an architect and the author of a book about the psychology of creative space, I have long wondered why contemporary creatives cluster so willingly in noisy coffee shops. Granted, there’s scientific research that caffeine fuels the imagination, but doesn’t the surrounding din interfere with their ability to think creatively such that no amount of chemical stimulation can compensate for the distraction?

Certainly, many eminent writers from the past shunned clamor. Consider Marcel Proust. To remark that the French writer was sensitive to auditory interference would be an understatement. The man was positively neurotic about it. He treated the bedroom in his Paris apartment where he wrote like a sensory deprivation chamber—shutters closed, drapes drawn, the walls lined with sound-absorbing cork. It wasn’t enough. He wore earplugs too.

Anton Chekhov was similarly beset by hypersensitivity to sound. So was fellow obsessive Frank Kafka, who described his condition in his signature surreal style by saying that “I need solitude for my writing; not ‘like a hermit’—that wouldn’t be enough—but like a dead man.” Sadly, by the time he got his wish, it was too late to do anything about it.

The correlation between high-level inventiveness and difficulty in filtering out sensory inputs is understandable, given that open-mindedness is a hallmark of the creative personality. The problem for off-the-chart geniuses like Proust, Chekhov, and Kafka was that their minds were a bit too open. Everything got through. Hence the extreme measures they took to avoid being immobilized by incoming stimuli.

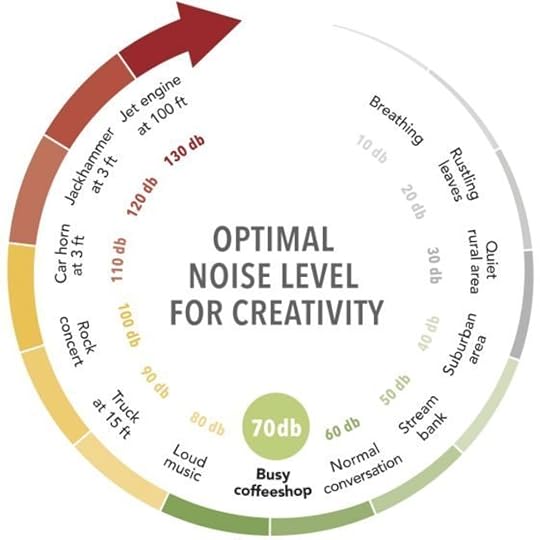

Fig. 1: Optimal noise levels for creative processing compared to other conditions. After Ravi Mehta, Rui (Juliet) Zhu, and Amar Cheema (2012). Illustration by the author.

Then again, most of us aren’t Marcel Proust. According to research data from 2012, most people reach peak performance under moderately noisy conditions—70dB (decibels), to be precise. It just so happens that this is roughly equivalent to the chatter in a typical coffee shop or restaurant on a relatively busy day (Fig. 1). It also approximates the crash of ocean waves breaking on the shore, the study thrum of crickets, and wind rustling tree leaves.

As to why this is the case, the scientists who authored the study offer a theory:

We theorize that a moderate (vs. low) level of ambient noise is likely to induce processing disfluency or processing difficulty, which activates abstract cognition and consequently enhances creative performance. A high level of noise, however, reduces the extent of information processing, thus impairing creativity.

Translation: silence isn’t as golden as it sounds. Absolute noiselessness tends to focus our attention, which is helpful for tasks that entail accuracy, fine detail, and linear reasoning, such as balancing our checkbook or fixing a Swiss watch. It’s less supportive of the broad, big-picture, abstract mind-wandering that leads to fresh perspectives and a creative work product. On the other hand, excessive noise overwhelms our sensory apparatus and hinders our ability to properly process information at all. In between lies the sweet spot—noise not so loud that we can’t hear ourselves think, and not so quiet that we can’t help but hear ourselves think.

Living room and fountain details. Bellevue, Washington. Architecture by David Coleman Architecture. Interior design by Elizabeth Stretch for Stretch Design. Photography by Paul Warchol.

There’s a caveat to the data, however: the noise has to be white. For the record, the technical definition of white noise is noise containing multiple frequencies with equal intensities. More colloquially, the phrase refers to a constant background noise, especially one that drowns out other sounds, and which takes the form of meaningless or distracting commotion, hubbub, or chatter.

Why is it important that the noise be white? Because otherwise you’re prone to tune into and attempt to discern the source and meaning of the sound, which diverts too much of your conscious attention from your task to be a useful tool for diffuse thinking.

How to Make Noise When There Isn’t Any

How can we creative mortals who don’t care for the smell of coffee, lack the funds to construct an oceanside villa, or live in urban environments where trees are scant benefit from the finding that a particular type and level of noise can promote insights? Here are a few options to consider:

Get the app. Yes, Virginia, there really is an app for everything. Use the search term “noise” to bring up dozens of sound generating programs in your smartphone’s app store. You’ll also see a broad selection of metering apps for measuring decibel levels at home.

Some of the app companies operate websites that let you download audio files of white noise soundtracks onto your computer or play them directly through a browser. A couple of my favorite sites include Raining.fm, which offers tracks simulating—what else?—downpours, rolling thunder, and heavy thunderstorms, and Coffitivy, which specializes in—what else?—coffee shop buzz.

Get or hack a sound generator. Another option is to purchase a desktop appliance designed to emit white noise. They’re smallish devices, typically placed on night tables and in babies’ rooms to help occupants fall asleep. For an architectural solution, think about installing an indoor or outdoor fountain—few things in life are as pleasantly hypnotizing as the mellifluous whoosh of water descending onto water. Price points run the gamut from low cost store-bought products to sky’s-the-limit custom installations.

DIY contrivances also abound; consult the Internet for guidance.

Let in or keep out external noise. City dwellers and people who reside along busy highways might have a ready-made noise machine right outside their window: road traffic. Open your windows to varying degrees or use sound muffling, such as drapery, to see if you can calibrate ambient noise to fall within the optimal range.

A less cacophonous strategy for harnessing exterior sounds would be to park yourself on a bench or beach that lies within earshot of ocean waves. It’s like having an always-on fountain, only bigger.

A less cacophonous strategy for harnessing exterior sounds would be to park yourself on a bench or beach that lies within earshot of ocean waves. It’s like having an always-on fountain, only bigger.

Listen to music. Like noise, music can have a positive effect on idea formation, while affording the listener far greater pleasure than the usual restaurant ruckus. But music is a huge subject in itself, and so must wait for another day!

Note from Jane: if you enjoyed this post, check out My Creative Space: How to Design Your Home to Stimulate Ideas and Spark Innovation, 48 Science-based Techniques by Donald M. Rattner.

October 24, 2019

How to Reach Out to Influencers for Book Promotion

Today’s guest post is an excerpt from The 10 Commandments of Author Branding by editor and author Shayla Raquel (@shaylaleeraquel).

An influencer is an individual who has built a reputation for his or her knowledge and expertise on a particular topic and likely uses social media to get that message across. Pat Flynn is a notable influencer in the entrepreneur and podcaster niche, best known for Smart Passive Income. People gravitate toward him because he’s an expert in his field (who happens to have a large following: very important). People listen to influencers’ recommendations because they have credibility. You trust them. Think of some people you follow and trust. Chances are that’s an influencer. Here are some of my favorite influencers in the book world:

Joanna Penn

Mark Dawson

Jerry B. Jenkins

David Gaughran

You don’t need an influencer’s clout to make your book and brand successful. But if you want to reach a larger audience and make more sales, then keep reading.

As with many things, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to pitching to influencers and borrowing their tribes. But we are going to cover the basics and some important do’s and don’ts.

Which Influencers Do I Approach?

You start with people you already know or have connected with: notable authors, bloggers, speakers, podcasters, artists, or business people who would be interested in endorsing or promoting your book.

Once you have a list of the notable people you have connections with, it’s time to make a second list. Do you know anyone who is connected to someone notable? Maybe you’ve never met Joyce Meyer, but your cousin helped her with a few details in her latest book or acted as her personal assistant’s assistant during her most recent conference tour. Write down those names! It’s okay that you don’t have BFF bracelets with that person. You have a mutual friend, and that’s a start—but I do recommend having your connected friend write an introduction or the initial pitch, not you.

Your third list: a cold call list. You won’t actually call these people, but you will be emailing them. This one is tricky, and we’ll cover it below—but write down a list of influencers you’d just love to have endorse or promote your book. The sky’s the limit!

How Do I Pitch Influencers?

Flattery never hurts. Tell them not only who you are but why you’re worth their time. Did you practice something they preached? Did you follow their courses with excellent results? Did you write a five-star review of one of their romance novels? (Keep the compliment section brief, though.) Here are some do’s and don’ts to keep in mind.

Do be brief. When I started pitching to influencers, I was one verbose cookie. Thanks to Mike Loomis (literary agent, brand marketer, and author of Your Brand Is Calling), I’ve learned to cut it way down. Remember: Influencers are busy people. They don’t have time to read a novel-length email.

Do give influencers plenty of time to say yes or no. If your book has to be finalized for publication by June 1 and you want endorsements in the front matter by then, ask for an endorsement in April (maybe even March). They need time to read and review your book.

Don’t be pushy. Hounding them will result in a huge no. It’s okay to email them to check in, but don’t drive them nuts.

Do write up five to ten boilerplate endorsements for their use. Bet you didn’t know that authors often write their own endorsements, huh? The influencer can tweak them or add to them—it’s just nice to have a few prewritten endorsements for the influencer’s convenience.

Don’t get your feelings hurt when they say no. Thank them for their time. Don’t burn any bridges! Always be grateful.

For tracking down their email addresses, you can try these methods:

Go to the influencer’s website and use his or her contact form or use the Find/Search function and type in the @ symbol to scan for an email address.

Go to the influencer’s Facebook page, click About, and look under email address.

Go to the influencer’s LinkedIn page, ask to connect, and if you get a yes, look under his or her contact information.

Look for press inquiries or publicist inquiries while on the influencer’s website if the first three options don’t work.

When Should I Start Pitching?

Tim Grahl (author of Your First 1,000 Copies and Book Launch Blueprint) recommends starting six months before your release. I’ve started at three months and done fine. However, these are busy people, so it can take much longer to get things moving along with an influencer.

Final Thoughts

Don’t forget: You are an influencer to others and have the power to absolutely make a fan’s day. Some readers out there are obsessed with your books. If they were to meet you in person, they would probably cry or jump up and down. You have touched their very souls, and they love you for that.

For me, this person is Mary Kubica. Once I read The Good Girl and I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I did a couple of shout-outs on Instagram, and she responded. I asked her for an interview, got it, and eventually wound up with a signed copy of the book that started it all for me as a book blogger.

I. Went. Bananas.

To have this incredibly successful author actually talk to me made my day. My whole week, really. I’ve never forgotten that moment.

To have this incredibly successful author actually talk to me made my day. My whole week, really. I’ve never forgotten that moment.

And you have the power to make a fan’s day just as Mary did mine.

When fans tag you, say thank you and talk to them. Repost their photos of your book. Retweet the interview someone did with you. Show that you care, and the reader will never forget it. You want to do this author thing forever, right? Then be grateful to the readers who make it happen.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, check out Shayla Raquel’s new book The 10 Commandments of Author Branding.

October 23, 2019

The Value of Touching Details

Photo credit: angus mcdiarmid on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Submit your first page for critique.

First Page

Early September

Phoebe is looking through a one-way mirror at a row of seven men lined up against a white wall marked with ruler-like black lines and numbers too faded to read, especially if you are blind as a bat. Behind her is another row of men, all police officers. Well, actually, there is one woman among this blue uniformed group. Unlike the rest, who stand, she sits to Phoebe’s left on a molded plastic chair with a crack along the front. It squeals softly whenever the policewoman shifts her weight, as now when she leans forward, settles elbows on knees, chin between her fists. Phoebe looks over and the two lock eyes. “Not at me, darlin’” the policewoman says. She nods toward the big mirror “At them.”

Everyone is waiting for Phoebe to react in some way, just as they were when they had her look through dozens of photos, six at a time. The seven men behind the glass, a few standing with their feet apart and hands clasped in front of their groins, cannot see Phoebe. She knows this. Even so. Even so.

She stares as instructed but doesn’t focus, doesn’t even try to focus. Ten minutes. Long enough. She drops her head, looks down at the floor and over at the policewoman’s feet. She’s wearing black leather shoes with fat laces and thick soles. A wad of pink gum attached to the left has attracted grimy bits—a tiny stone, strands of hair, a piece of grass or something else green and living—and it’s a good inch or so thicker than the right sole. Evidence. The woman must be lopsided—need this accommodation to keep from limping, to camouflage some embarrassing infirmity. For some reason this, of all things, makes Phoebe want to cry.

* * *

Phoebe had only swum 33 of her usual 52 back-and-forth’s that day. Out to the enormous cloud-shaped rock, one; back to the weather-beaten cement gnome, two. She’d been doing the breaststroke—head down for the glide, then up for a breath. Taking a breath: that’s when she caught sight of him, standing by the gnome at the water’s edge.

First-Page Critique

Not long ago on a friend’s recommendation I read a novel; or I half read it, not having been compelled to finish. When the friend (perturbed) asked me why, I answered, “I didn’t believe it.” This answer raised my friend’s eyebrows—as it has raised the eyebrows of many students of mine to whom I’ve suggested that a work of fiction should be credible.

“But it’s fiction!” they protest. “It doesn’t need to be believable!”

I disagree. The whole point of fiction, if you ask me and as I tell them, is to make believers out of us, to convince us that a world that’s mostly if not completely invented is real enough to invest in emotionally. Whether the world resembles the one that most of us inhabit daily, or it exists in another dimension, in another solar system, in an alternative universe, it must be rendered convincingly such that as readers we suspend our disbelief.

How do we writers get our readers to not doubt the worlds that we create for them? One way is through the use of details, and especially of what I call touching details.

A touching detail is one that, though it may seem arbitrary or trivial, supplies a note of authenticity. In this sense touching details are paradoxical: the less substantial they are, or seem to be, the better they tend to work. But rather than try to explain to you what a touching detail is, let me show you some examples. This first page holds a few.

The scene: a police line-up. Surrounded by uniformed officers, a woman—Phoebe—stares through the one-way mirror at “a row of seven men” lined up against a calibrated wall. She has either been the victim of or witnessed a crime and has been summoned to identify the perpetrator. The scene raises all the right questions: What crime did Phoebe witness or endure? Will the criminal be caught? Why does she seem so detached? However functional, the scene is also familiar. While few of us have experienced a police line-up first-hand, most of us have experienced dozens in books, movies, and TV shows. Since it’s so familiar, any author who writes such a scene runs a risk of cliché.

This is where touching details come in, for among the best ways to disarm a cliché is through their use. Here, for instance, within the first paragraph, just when a jaundiced reader might begin to question the authenticity of this police line-up, our attention is drawn to the “molded plastic chair with a crack along the front” in which the policewoman to Phoebe’s left sits. Does it really matter what sort of chair that woman sits on, or whether or not it’s cracked? Inasmuch as those minor details convince us that both the chair, its occupant, and the scene that contain them are real, it does. Those details exist for one reason: to disarm us, to make us question any doubts we might have as to the scene’s authenticity. That’s their only purpose, but it’s a noble one. Absent such touching details, this scene would join the endless parade of generic police line-ups, each of which resembles its brethren so closely they might as well be the same scene.

The second paragraph of this first page furnishes us with another touching detail, how some men in the line-up “[stand] with their feet apart and hands clasped in front of their groins”. A detail with symbolic significance? Maybe, depending on the nature of the crime. Symbolic or not, those clasped hands qualify as a touching detail. In the third paragraph we get the policewoman’s black leather shoes “with fat laces and thick soles.” If those soles and laces aren’t sufficient in themselves to disarm us, the author goes on to describe “[a] wad of pink gum attached to the left [shoe, one that] has attracted grimy bits—a tiny stone, strands of hair, a piece of grass or something else green and living.” So precisely is that shoe described, with touching detail added to touching detail, can we possibly doubt that the owner of said shoe is real, let alone the shoe itself?

Looked at this way through a microscope, such touching details may seem exotic; in fact they’re to be found in nearly every paragraph of good fiction, and other sorts of writing, too. But while most writers use them, some have a particular gift for the touching detail. One who comes instantly to mind is Emmanuel Bove (1898–1945), a Parisian son of Jewish immigrants born into extreme poverty. His first novel, Mes Amis (translated as My Friends), consists of little more than a catalogue of touching details. It opens:

When I wake up, my mouth is open. My teeth are furry: it would be better to brush them in the evening, but I am never brave enough. Tears have dried at the corners of my eyes. My shoulders do not hurt any more. Some stiff hair covers my forehead. I spread my fingers and push it back. It is no good: like the pages of a new book it springs up and tumbles over my eyes again. … When I bow my head, I can feel that my beard has grown: it pricks my neck.

Another champion of the touching detail is the Italo-German author Natalia Ginzburg (1916–1991). Her most famous novel, È Stato Cosi (translated as The Dry Heart), is a first-person account of mariticide that holds this first-page passage:

He had asked me to give him something hot in a thermos bottle to take with him on his trip. I went into the kitchen, made some tea, put milk and sugar in it, screwed the top on tight, and went back into his study. It was then that he showed me the sketch, and I took the revolver out of his desk drawer and shot him between the eyes.

Note how the screwing tight of the thermos top—an insignificant detail—is given as much (or as little) importance as the act of murder. By giving them equal weight, by treating touching details as matters of great or obvious significance, we endow them with an authority that draws our attention to them and away from the clichés that would otherwise rush in to fill the vacuums left by their absence. In an ideal world, every page would hold at least three.

Is it just a matter, then, of peppering our stories with any old trivial details? Alas, no. They have to be the right touching details, the perfect details, used judiciously, like cilantro or certain spices, lest they wear out their welcome. How do we know if our details are right, let alone perfect? We don’t—or we do, but only by an instinct peculiar to gifted writers.

We have to choose between the quick and the dead. The quick is God-flame, in everything. And the dead is dead. In the room where I write, there is a little table that is dead: it doesn’t even weakly exist. And there is a ridiculous little iron stove, which for some unknown reason is quick. And there is an iron wardrobe trunk, which for some still more mysterious reason is quick. And there are several books, whose mere corpus is dead, utterly dead and non-existent. And there is a sleeping cat, very quick. And a glass lamp, alas, is dead. … What makes the difference? Quien sabe! But difference there is. And I know it.

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.) Here’s how to submit your first page for critique.

Note: The publisher of Your First Page is offering free shipping if you order the book directly from their site. Use code YFPfreeship.

October 18, 2019

Current Trends in Traditional Book Publishing: Fiction, Nonfiction and YA

photo by Annick Press

As publisher of the The Hot Sheet newsletter, I regularly read and report on market trends that affect traditionally published and self-published writers. In today’s post, I’ve gathered some of the trend information we’ve published in 2019; while it’s most pertinent to traditionally published authors, self-published authors may recognize these trends in the market as well.

If you’re interested in The Hot Sheet, you can subscribe for 30% off the usual rate as part of our 4-year anniversary sale. Sign up for a 30-day free trial and use code 4YR at checkout for the discount. This code will work through the weekend.

Traditional Publishing: The long-term market is flat.

According to reports from NPD Bookscan, after six years of growth, the print market for traditional publishers has started to decline. High-profile titles drove growth in 2018, while backlist gained market share, thus squeezing the midlist. Political fatigue is setting in, but lifestyle themes (e.g., Marie Kondo) remain strong.

While print sales are roughly flat, the ebook market for traditional publishers has declined every year since 2014; the market has remained stable in part because of the growth of digital audiobooks—where revenue grew 37 percent year on year through November 2018. One of the key questions moving forward is whether audio can grow the digital market without cannibalizing existing formats. Dominique Raccah, CEO of Sourcebooks, said during BookExpo that cannibalization is not happening from where she sits: more formats means more sales.

While nonfiction is still performing better than fiction, political book sales are down. During the first quarter of 2019, political book sales declined 28 percent compared to last year, according to NPD Bookscan. But it’s not for lack of new titles; title output is up 16 percent. Editors and agents are becoming far more critical when acquiring political titles; see more below under nonfiction trends.

The top YA growth categories in 2019 are in nonfiction—history, sports, people, and places. The biggest YA decline was in general fiction, but the top fiction category is now science fiction / magic—a rebound after a significant decline for that category in 2017. As a whole, the YA category is marginally positive.

Trends in Adult Fiction

At this year’s New York Rights Fair (held at BookExpo in late May), a panel of agents and editors discussed what they’re looking for in fiction. It included agent Melissa Flashman (Janklow & Nesbit), editor Sally Kim (GP Putnam’s Sons / Penguin Random House), editor Amy Einhorn (Flatiron/Macmillan), and agent Dorian Karchmar (William Morris Endeavor).

Psychological suspense remains popular. This genre has been trending since the publication of Gone Girl. However, Karchmar said fatigue and skepticism have started to develop around the category, and more derivative books are getting published. Still, there’s a sizable market for it.

The current reader mood: escape combined with nostalgia. Kim believes this is driven by current events, or how the world is “a little bit upside down”; people look to books for an escape. She also pointed to horror as experiencing a nice resurgence, partly due to nostalgia—readers want to recapture that time when they were a reader in high school and loved such books. Flashman added that Millennial readers are nostalgic for life before social media (the cutoff is around 2006), and so we’re starting to see novels that tap into that sentiment.

Some of the panelists expressed surprise at the success of darker narratives. One example offered was When Breath Becomes Air, a memoir by Paul Kalanithi, a story posthumously published about his metastatic lung cancer, represented and sold by Karchmar to Random House. She said, “A lot of people [in the industry] were scared about that book. There was a lot of skepticism about whether that could work.” However, she believes there is a hunger, curiosity, and sense of urgency “for readers to understand and experience POVs that are not their own—which of course is sort of the whole freaking point of fiction.” She added, “It’s quite wonderful to see this growth and profound interest that has emerged that proves some of the truisms wrong—that dark can be great as long as we’re being immersed in an experience that is being fully excavated for its meaning.” (Note that those on the panel said they group fiction and memoir together when describing qualities they look for in a story.)

High concept was once important—and can still sell a book—but that doesn’t necessarily lead to a long sales life. Kim said, “For a while it seemed everything had to have a high concept to cut through all the noise. … But those that really last are those books that have really good storytelling, good voice, books that really move you. … It has to have the deeper layers.” She later elaborated that what makes a book succeed sales-wise is word of mouth, and that is driven by writing that is “really, really good” rather than by an original or a high-concept conceit.

However, a great hook is critical to marketing. Flashman said that, regardless of how great the writing is, “It remains as important as ever to still have a pitch around it. It doesn’t have to be that extreme high-concept pitch, but looking at A Gentleman in Moscow, you can pitch it. … There’s still a way to talk about it: ‘Right after the Russian revolution, an unabashed aristocrat is sentenced to life imprisonment in the fanciest hotel in Russia.’ There’s still a hook.”

The panel expressed, with a very apologetic tone, that authors are more responsible than ever for marketing. Kim said, “We put a lot of responsibility and onus on our authors to do a lot of work. We do look to our authors to be the best [marketing] person for their book.” Karchmar agreed and said that the importance of the author promoting the work has really amplified in the last five years. She said the authors who think of themselves as public figures are well positioned to succeed. She said it’s a necessity for the writer (even the introverts) to be part of the conversation and understand the other books and writers with whom their work is in conversation, as well as what it is they care about most deeply—usually what the book has been written in service of. Karchmar added that publishers aren’t aggressive enough about promoting the author as opposed to the book, which hurts the author in the long run. “We do see people who are huge fans of a given book but don’t even remember what the author’s name is,” she said. Karchmar said the author brand-building effort falls to the author, sometimes with the agent’s help, “to be promoting him or herself through other forms of writing and engagement other than just the novel and readings that the publisher sets up for them.”

Trends in Adult Nonfiction

Adult nonfiction continues to drive sales in traditional publishing, with 5 percent growth since 2015. Again, at the New York Rights Fair, agents and editors discussed what’s happening in the category.

First, we’re entering the era of Trump fatigue in book publishing. The new Michael Wolff book has not zoomed up the charts like his first one, and people have become desensitized to the news coming out of the Trump administration. The bar is now set high for the acquisition of political nonfiction. In addition, agent Keith Urbahn from Javelin said that too many politicians’ books lack self-awareness; to work properly, you have to “take something out of their background that feels different” or find something in their experience that can speak to book buyers. (Urbahn represents Senators Ben Sasse and Tom Cotton.)

With journalist-authors, when making acquisition decisions, Paul Whitlatch at Hachette said they’re “thinking about access and freshness of story and something that hasn’t been covered to death elsewhere.” The panelists believed journalists are under contract to write some of the next and most important books in the political category. (The New York Times especially is feeling the effects of this as their staff members request leaves of absence after securing book deals.)

Regardless of category, with any big nonfiction deal, editors and agents look for what will pop in the media. Whitlatch said too many public figures want to write books for the wrong reasons and don’t understand what will get the media excited. Sagalyn agreed, saying that media drives everything. “It’s not just what will get on, it’s what won’t get on. It’s so hard to get access to media that it really influences what publishers are buying and what we are considering. … What’s going to make this stand out in the marketplace? What’s your elevator conversation?”

So what’s the media looking for? Urbahn said there’s a hunger in media to talk to diverse voices, and agents/editors must take that into account: “If you’re not responsive to it, you’re not doing your job.” Whitlatch said, however, that publishing still needs to do better in its acquisition of diverse authors. “Change doesn’t come overnight, but it’s something everybody cares about.”

While the idea of authors cultivating their tribe is not new, agents/editors still talk about seeking authors who have one. Nelson said, “I’m always looking for someone who has an existing tribe and is building around an existing idea. The thing I say most to authors who reach out to me … is a book is the worst way to build a tribe. It’s how you feed a tribe that you’ve already built. Get out there and do something else.” He went on to say, “My favorite author is one who is a celebrity to their tribe and no one knows who they are. Non-celebrity celebrity is my favorite kind of author.”

Trends in YA and Middle Grade

While YA fiction sales have flattened out in the past year, the entire YA category, alongside adult nonfiction, has been driving growth in traditional publishing for several years. A New York Rights Fair panel of agents and editors discussed recent trends.

One of the first topics discussed was the re-emergence of dystopian and horror genres. Stacey Barney from Penguin Random House said, “We’re in some dark days right now, so I’m not surprised if dystopian starts to come back.” David Levithan of Scholastic said acquisitions are shaped by the times and pointed out the rise of horror. “It does not take a brain surgeon to see why this is happening,” he said. “We’re seeing middle-grade horror, which I think is one of the best things for these times. … [Young readers] want to be afraid, but then they want the book to make them unafraid by the end.”

There’s also been an increase in YA and middle-grade nonfiction—not school texts, but books for fun. Levithan said Scholastic has launched a new narrative nonfiction imprint, Scholastic Focus, because “facts and truth are more important now than ever.” He said they’re looking for voices in nonfiction that will help young readers understand their own history and the history of people around them. He said readers now must navigate an era in which there is plenty of information yet no context. “We have to give them the context,” he said. Barney said that a lot of the nonfiction she’s doing is memoir and inspiration—and that kids read memoir and inspirational stories for the same reason adults do. She noted that these stories are from kids who are exposed to a lot: “These are not the 12-year-olds of my day.” With the advent of social media, young people have more information, and they’re doing extraordinary things, she said. “They are their own sources of inspiration.”

Graphic novels are exploding across all publishers. Stimola said it’s a trend that cuts across age groups and affects everything from chapter books to middle grade to YA and adults. “With all the screens and gaming they’re doing,” she said, “it’s a kind of reading that brings them to the printed page more easily, a little more comfortably.” Agent Jenny Bent agreed: “That’s exactly my daughter’s experience. She was a very reluctant reader … she experiences life so much more visually than we did. Everything is images. They are on their phones, they are watching TV, so the thing that was her gateway into reading was graphic novels.”

Agents and editors are seeing growth in TV/movie adaptations for middle grade and YA work. Bent said that it’s easier to get deals than in the past. “[Studios and producers] are open to all kinds of voices and all kinds of stories that they weren’t even two or three years ago,” she said. Stimola added that, on the film side, for a very long time the focus had been on front list—what’s new and what would work for the big screen. But now with all of the streaming options out there, adaptations are a growth area—especially for works that are better suited to episodic format. She said, “Episodically you get to keep a lot [of the book] and even expand on it. And there were things that went to the big screen that failed miserably—it just didn’t work—but now they’re begin given great new life in episodic format. They’re very hungry for content and there’s going to be a lot more happening.” According to NPD Bookscan, bestselling children’s books are often driven by content available on streaming services. However, when asked if film or TV potential affected what books they would acquire, the panel responded with an emphatic no.

Audio is also an area of growth. Levithan said that, at one time, an audiobook would be a weird outlier for Scholastic, but not anymore. “It’s a time thing. They can walk with it, they can have it in their cars. I think it is fitting in to the culture, filling in the time.” He mentioned that when Scholastic struck a deal with Audible to do the Baby-Sitters Club series, he was surprised when Audible decided to release all 131 titles on the same day. The reasoning? Binge listening. Apparently, he said, there are people who have a bad day and decide they’re just going to listen. “That has changed the game to a significant degree,” he said. For Barney at PRH, audiobook sales follow the life of the book itself—they increase if the book has won an award, for instance. “I don’t know that you see audio outpace the physical copy, but it is for sure becoming a robust market for us.” She said for a recent title, audio was a key component in the P&L and helped her get to a certain level for an offer. “I was blown away by that.” And in a comment that sparked laughter and surprise (with suggestions to take the money and run), Stimola said she recently received an audio rights offer for a wordless picture book.

In a separate session with NPD Bookscan’s Kristen McLean, she expressed concern about the midlist children’s author. Unfortunately, as there’s further sales consolidation in the top titles, the midlist suffers in children’s, just as it does in the adult market. McLean believes that the future for the midlist author—or someone not in the top 100—will be driven by finding passionate groups of people. She sees innovation coming from digital audio content and distribution—“in children’s it will be about interactivity,” she said—as well as in brand licensing, where big publishers typically have an advantage.

In a separate session with NPD Bookscan’s Kristen McLean, she expressed concern about the midlist children’s author. Unfortunately, as there’s further sales consolidation in the top titles, the midlist suffers in children’s, just as it does in the adult market. McLean believes that the future for the midlist author—or someone not in the top 100—will be driven by finding passionate groups of people. She sees innovation coming from digital audio content and distribution—“in children’s it will be about interactivity,” she said—as well as in brand licensing, where big publishers typically have an advantage.

If you’re interested in The Hot Sheet, you can subscribe for 30% off the usual rate as part of our 4-year anniversary sale.

Sign up for a 30-day free trial and use code 4YR at checkout for the discount. This code will work through the weekend.

October 17, 2019

7 Non-Literary Ways for Writers to Get into the Flow

Photo credit: letavua on Visualhunt.com / CC BY-SA

Today’s guest post is by writer and publisher Rosalie Morales Kearns (@RMoralesKearns).

If you’re a creative writer looking to feel inspired and nurture your creativity, you’ll find all kinds of advice out there, with Write every day at the top of the list. A close second is Read voraciously, within your own genre and outside it.

The idea is that when you sit down to work on your manuscript, your imagination has been fed by all that reading, primed by that daily writing practice. We hope to reach a state of mind where we’re dreaming the scene, where images, dialogues, entire scenes come effortlessly. An altered state of consciousness. Flow.

But sometimes you just feel drained. Reading seems like a chore, and writing every day is like squeezing blood from a stone.

How do you achieve flow when the well has run dry?

I was at that point this past summer, and here are some things that helped me.

What I especially love about these is that they don’t involve reading and writing. They engage your senses—touch, hearing, taste, sight—and feed you as an artist.

1. Light Up

I’m talking about candles. What did you think I meant?

I got out of the habit of using candles after we started adopting cats, terrified that one would get too close to a flame and singe her whiskers. Finally I said to myself, “Self, there are tall glass candleholders. There are tiny tea lights that can sit way at the bottom, well beyond a cat’s reach. You can do this.”

Sit quietly for a few minutes with the flame, that small glowing thing that needs oxygen, that converts fuel to energy, just like you do. No need to stare at it. It draws your attention without effort, leaving you both relaxed and focused—basically the definition of what it feels like to be in flow.

If possible, keep the lit candle near you while you write.

This doesn’t have to be expensive. A wide-mouthed canning jar will do fine, and you can buy a metal thingy to clip on the side and hold a tea light for under three dollars.

2. Look, Don’t Think

My next suggestion: art books, or any heavily illustrated book with images that you enjoy.

Remember, we’re not reading. Don’t read the text, no matter how interesting, at least not when you’re just trying to fill the well.

Turn off your critical mind, the part that creates a running commentary. Page through the book, taking in the images. Just be there, in the presence of a different kind of art than what you’re creating with words on a page.

Recently I did this with Paint the Revolution: Mexican Modernism, from a truly memorable exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. After that, I delved into an Edward Gorey compilation my cousin Gwen sent me.

The images don’t have to relate to what you’re writing. The experience doesn’t have to result in a specific piece of writing inspired by an image (although that can easily happen).

Granted, exhibition catalogs are pricey. But library books, and library cards, are free. I guarantee you there are art books on the shelves at your local library, and they can acquire others for you through interlibrary loan.

3. Put It Together

Next up: jigsaw puzzles.

Okay, hear me out.

There’s something amazingly comforting in knowing that hundreds of disparate pieces will fit together into a coherent whole.

Yes, it’s hard. Where’s the fun in doing something easy?

But it’s another surefire way to get into the flow. When you settle into a puzzle, you’re both relaxed and focused (remember how you felt with the candle?). Time flies by. You’ll get to a stage where you reach out and grab a piece that’s in your peripheral vision and without looking too closely, put it exactly where it belongs. That’s because you had seen that piece already and you understood how it related to the others without any conscious thought.

And the next time you sit down to write, things that you couldn’t figure out before—a plot development, a character’s next action—are suddenly clear. Your subconscious was working on them back at the puzzle table.

A typical price of a 1,000-piece puzzle is $18 or $20. But book sales at libraries often include inexpensive ones that patrons have donated; also you can exchange with other puzzle lovers. Fun fact: if people know you like puzzles, they also give them to you as gifts.

4. Close Your Eyes and Listen

Another thing I recommend is listening to fairy tales in audiobook format.

This is less like reading and more like absorbing. Don’t try to take notes (you can go back later and do that, with audio or text). Don’t try to analyze what you’re hearing. Just let the stories wash over you, one after another.

So then, why fairy tales? Why not just any great book in audio format?

For one thing, tales were meant to be told aloud. For another, it’s fun to revel in the outlandish coincidences, gloriously enigmatic characters, and colorful turns of phrase (“It is not so, nor it was not so, and God forbid it should be so”).

In fairy tales, it’s all off-kilter and yet exactly right.

And then there’s the simple pleasure of being told a darn good story.

You can download audiobooks for free from your library’s website, and find great discounts from audiobook publishers. I bought the entire compilation of Grimms’ fairy tales on Audible for five dollars, and 100 Russian Folktales for $4.90.

5. Play the Music of the Cosmos

“All you have to do,” my friend Donna said, “is search for the phrase ‘healing music’ on YouTube. Trust me.”

I picked one of the first items that came up, mostly because it lasts six hours and features a big purple-and-pink lotus. The music meandered around, gentle and unobtrusive, with no melody and no beat. Instead of being annoying, it was incredibly relaxing and energizing at the same time.

Turns out, music tuned at the frequency of 432 hz is … well, admittedly I don’t understand the theory behind it. It’s in tune with the earth, somehow.

All I know is, when it’s playing quietly in the background, somehow my brain works better.

Really, Rosalie? Cosmic music? What’s next, incense and crystals?

Glad you asked.

6. Get Down to Earth

I’m an earth sign. I love stones in their natural state. Small chunks of rose quartz, moonstone, tumbled ruby—all kinds of unfinished crystals have a home on my bookshelves.

Don’t worry about figuring out which stone has which properties. There are endless interpretations out there. Pick something that resonates with you on whatever level. If you think it’s pretty, that’s reason enough. Take it home and set it next to you, alongside the candle and whatever device is playing the healing music.

I learned the rudiments of jewelry making so I could order the stones I like in bead form and make simple bracelets. One of the first ones I made was of small polished chips of black obsidian, on three intertwined strands.

For me, a black stone means the protective, warm embrace of our mother Earth. It also stands for that place you go when you’re dreaming the scene, when you’re in the flow. It stands for the mystery.

When I put on that triple-stranded obsidian bracelet, it’s like magic. The words come, the scenes come, the pieces of the story fall into place.

Call it a self-fulfilling prophecy if you like. What matters to me is, it works.

You can find rough crystals and simple gemstone bracelets in New Age-y stores, at arts fairs and farmers’ markets, or go to Etsy and search for “raw emerald crystals,” “rose quartz bracelet,” etc. You think emeralds are expensive? Here are half-inch unpolished pieces for $1.30, and look how pretty they are.

7. Give Yourself a Treat

Dark chocolate is brain food. That’s just science.

Last year my friend Alice sent me a gift of chocolate-covered dried cherries from a company called Chukar Cherries, and now I’m addicted. Just my luck, they’re on the other side of the country from me, and the only time shipping costs are reasonable is winter. Did I mention winter is my favorite season?

Admittedly, these are pricey. You can find less expensive chocolates. You could be admirably healthy and have a sliced apple or some dried cranberries.

The point is that you’ll associate your writing time with something sweet and enjoyable—something to look forward to.

Put a few chocolates in a little dish close to hand, near your candle, your phone playing healing music, your gemstones. Now open up your journal or your laptop or whatever random scrap of paper floats your way—and write!

October 16, 2019

Why Writers Should Use a Clearly Defined Perspective—Not an Indeterminate One

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Submit your first page for critique.

First Page

Dr. Zokosky, or Dr. Z as his students had warmly referred to him, was alone in his basement. However, he wasn’t exactly there at all. The wrinkles around his eyes and the deep furrow of his brow had been released by the limp weight of unconsciousness. His lanky, 74-year-old body was reclined against the pea-green vinyl of a repurposed dentist chair. A white helmet sat heavily on his head and framed his slumped face and unkept, grey beard.

The basement, which Dr. Z had ardently re-named “the lab,” was quiet except for a delicate whine coming from the helmet. The glow of the laptop screen and a hint of sunlight from the stairwell door were the only mentionable sources of light. They stood little chance of countering the dark and musty atmosphere of the space. The silhouettes of stacked boxes, laboratory stands, and various armatures littered the room and created the illusion that the basement was crowded with dancing robots that had been frozen in time.

Though the pea-green dentist’s chair looked to be playing some important role in Dr. Z’s current state, its only purpose was to provide a reclined position for his unconscious body. The device itself was made of two primary elements: the helmet and the control box. The helmet, currently on Dr. Z’s head, was made from a 1973 motorcycle helmet. It was one of several items that Dr. Z had purchased from a local pawn shop. Three circular shaped canisters, each roughly the size of a five ounce can of tuna, were attached to the helmet—one on top, one on the left side, and one on the right side. Inside each of the canisters were carefully balanced, and currently spinning, rare-earth magnets. Dr. Z had “acquired” the magnets from the university lab.

An overwhelming bundle of thin wires led from the magnet-filled canisters to the black control box, which was sitting on a nearby workbench. The control box was relatively small—roughly the size of a paperback book. Only two wires led out of the box. One wire snaked its way under the table and into a wall outlet. The other wire was plugged into Dr. Z’s laptop. If not for the steady rise and fall of Dr. Z’s chest, one might think that he was the now-deceased victim of a cruel, human experiment.

On the workbench, sitting alongside the small control box and laptop, was Dr. Z’s handwritten journal. The journal was currently open and ready to receive the next entry. The only comment thus far on the page was the date and time that the session had begun: Wednesday, June 13th, 2018. 2:30pm.

Dr. Z’s index finger twitched lightly. The time on the computer screen changed from 5:29pm to 5:30pm. The control box clicked and the light hum of the magnets drifted toward a deep and fully audible wavering. The magnets eventually slowed to a stop and the room returned to its musty silence.

First-Page Critique

Every now and then a first page perplexes me. All the ingredients of a compelling opening are—or seem to be—there. In this case, a university professor performing—or having just performed (he is no longer conscious)—an experiment involving a vintage motorcycle helmet, a dentist’s chair, and “rare-earth magnets” on himself.

A mad scientist in his underground laboratory; a bizarre experiment gone (possibly) very wrong. Who could ask for anything more?

Yet something isn’t quite right or is less right than it could be. I’m not talking about the style, which strains for effects (the doctor’s wrinkles “released” by his unconsciousness; a hint of sunlight “[standing] little chance of countering” the basement’s darkness)—effects that call more attention to a talented but self-conscious author than to the scene in question. Something bigger troubles this first page.

If my years of teaching have taught me anything, it’s that when a piece of narrative writing isn’t quite working, the prime suspect is point of view. When in doubt, blame the narrator.

Who is this narrator? What particular set of sensibilities and awarenesses define him (for convenience’ sake, let’s make the narrator a man)? From what vantage point or points does he convey the experience of this passed-out professor in his laboratory, so we experience it as clearly as though it were our experience?

For us to experience an event clearly through a narrator, the narrator has to experience it clearly, meaning from a specific angle or perspective rather than a vague, general one. In this opening, either the author doesn’t have a firm grip on his narrator, or he has failed to thoroughly create one in the first place. Though presented to us as an experience filtered through a narrator’s knowledge and sensibilities, what we’re getting here is an unstable mixture of the narrator’s experience and the author’s information. And as I’ve said here and elsewhere before, readers of fiction don’t want information; they want experiences.

Let’s look at this opening line by line, starting with the first: “Dr. Zokosky, or Dr. Z as his students had warmly referred to him, was alone in his basement.” The perspective here is that of someone who knows the professor well enough to know the nickname his students have given him and that he has a “warm” relationship with them. Could the narrator be one of Dr. Z’s students? Possibly, though apart from referring to him as “Dr. Z” nothing else in this opening suggests so.

Nor is the perspective that of Dr. Z, who, being unconscious, isn’t privy to this moment. In spite of this, the first sentence of the second paragraph unites us with Dr. Z’s experience. Who else could know how “ardently” he re-named his basement? The paragraph goes on to render the setting, with its glowing laptop screen and sunlight poking through the door and laboratory accoutrements that look like “dancing robots … frozen in time”—all presented objectively, as a stranger unfamiliar with the doctor’s laboratory might view it.

This alien objective perspective extends to the first sentence of the following paragraph (“Though the pea-green dentist’s chair looked to be playing some important role in Dr. Z’s current state, its only purpose was to provide a reclined position for his unconscious body.”)—a sentence that, however convoluted, suggests little if any awareness of context. The same alien objectivity applies to the next sentence (“The device itself was made of two primary elements: the helmet and the control box.”). The sentence after that, however, in which we’re told that Dr. Z. bought the motorcycle helmet in a pawn shop, breaks with that perspective, as do the paragraph’s final sentences, which put us in the mind of someone who not only knows what’s in those canisters, but where the doctor “acquired” them.

The next paragraph (“The overwhelming bundle of thin wires …”) re-establishes the alien point of view—implicitly at first, then explicitly with “one might think,” the “one” clearly referring to a stranger. Apart from calling the doctor by his nickname and that last sentence mentioning those magnets (apparent only someone who knows of their existence), the rest of the page is—or could be—from the perspective of an outsider.

Without looking for them, would anyone reading this first page notice these slight shifts? It’s doubtful. But there they are. And though they don’t entirely negate it, they dampen the effectiveness of what should be a riveting opening.

Can a narrator’s perspective never vary? Does it always have to be consistent? Can’t it shift from paragraph to paragraph, or even from sentence to sentence? It can, provided it does so such that at any given moment the perspective is clear. Case in point: the opening to Katrina Bivald’s The Readers of Broken Wheel Recommend. It begins:

The strange woman standing on Hope’s main street was so ordinary it was almost scandalous. A thin, plain figure dressed in an autumn coat much too gray and warm for the time of year, a backpack lying on the ground by her feet, an enormous suitcase resting against one of her legs. Those who happened to witness her arrival couldn’t help feeling it was inconsiderate for someone to care so little about their appearance. It seemed as though this woman was not the slightest bit interested in making a good impression on them.

Here, too, the perspective is that of someone unfamiliar with the “strange” subject, but unlike our first page it is unequivocally, determinedly so. That perspective is maintained solidly through the next three paragraphs, is which “the strange woman” is described in greater detail. Then we get:

In actual fact, Sara had taken in almost every detail of the street. She would have been able to describe how the last of the afternoon sun was gleaming on the polished SUVs, how even the treetops seemed neat and well organized, and how the hair salon 150 feet away had a sign made from laminated plastic in patriotic red, white, and blue stripes. The scent of freshly baked apple pie filled the air. It was coming from the café behind her, where a couple of middle-aged women were sitting outside and watching her with clear distaste. That was how it looked to Sara, at least. Every time she glanced up from her book, they frowned and shook their heads slightly, as though she was breaking some unwritten rule of etiquette by reading on the street.

We haven’t changed narrators. But the perspective has taken a 180-degree turn, putting us into Sara’s (the strange woman has a name now, being no stranger to herself) sensibilities. Is the narrative perspective consistent? No. Is it clear and determined? Yes. Does it work? Well enough to have made Bivald’s novel a bestseller.

We haven’t changed narrators. But the perspective has taken a 180-degree turn, putting us into Sara’s (the strange woman has a name now, being no stranger to herself) sensibilities. Is the narrative perspective consistent? No. Is it clear and determined? Yes. Does it work? Well enough to have made Bivald’s novel a bestseller.

Were the opening of our first page written exclusively and thoroughly from an outsider’s point of view, that of a stranger witnessing this scene, it would read far more effectively. But any clearly determined perspective(s) would work better than an indeterminate one.

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.) Here’s how to submit your first page for critique.

Note: The publisher of Your First Page is offering free shipping if you order the book directly from their site. Use code YFPfreeship.

October 15, 2019

Intellectual Property: The Big Picture for Authors

Today’s guest post is by literary agent Ethan Ellenberg (@royaltyreminder), founder of Royalty Reminder.

Book publishing has changed dramatically over the last twenty years, and authors of all stripes have new opportunities to manage. Whether you are a long-time author with published work and contracts, or you are a self-published or “hybrid” author with some titles self-published and some licensed to publisher-partners, you need to do some serious thinking and track all of those licenses. This is truly a life-long journey for all writers and their heirs. The earlier you start comprehensively tracking this information, the better.

Let me sketch the big picture, which has two foundation blocks: copyright and the internet. First, copyright in most cases is the life of the author plus 70 years. This is your property—only you have the right to exploit it. The second, the internet, has many distinct but interrelated consequences, and involves two key elements for authors: digital versions of your work and 24/7/365 marketing worldwide.

Subsidiary rights and the internet

Ebooks can be produced, published, and marketed around the world at very low cost. This goes for original ebooks, but you can also revert rights to out-of-print titles and re-publish them digitally.

The same is true of audiobooks. Granted, producing them can be expensive, but the revenue potential in this growing market is enormous. There are platforms where voice acting talent will agree to split royalties (Findaway Voices or ACX), which can bring down upfront production cost. We aren’t quite there yet, but one can imagine a similar partnership with a translation partner in France, Germany, Turkey, etc.

It goes further. The internet giants are warring over TV streaming, spending by the billions. Spotify is trying to build a massive podcast business. A new venture capital backed short-form video streaming platform called Quibi plans to spend $500 million acquiring content before it even launches. It’s still early, but it appears as though each of these will be their own subrights—TV separate from short-form video, and podcast separate from audiobook.

Now, I’m not saying that you will be able to monetize each subright for every one of your titles. But the picture is clear—creators have never had more power. The world is hungry for storytelling in a plethora of mediums that seem to be spawning by the minute. And it’s all because the internet has enabled new formats, new markets, and fluid pipes.

This is a challenging task. To help with that, I’ve provided an overview for different author types on how to maintain your rights and income.

Authors with print books through a traditional publisher

For books that can be reverted to you or have already been reverted, you need to consider their potential as ebooks, print-on-demand editions and other opportunities that exist now or may emerge, as noted above. Consider:

Are my books in print?

What formats are in print — hardcover, trade paperback, mass market paperback, ebook, audiobook?

Are my books in print in all the right formats?

Are my books ever marketed or promoted?

Am I receiving royalty statements? Am I making any money?

Can any of my books be helped by a new cover or price change?

What subsidiary rights has my publisher sold? What is the status of those licenses/editions? Are they making any money? If they are translation or audio licenses, have I seen the royalty statements?

At my literary agency, we have seen substantial revenue generated by ebooks and audiobooks, two formats that your older books may not be in yet. If books are out of print and/or your publisher is willing to revert rights to you, revert those rights and make plans to pursue a second life for them. Be patient but be persistent. Have sound suggestions for how to help your backlist grow.

If your agent or agency is still active and performing services for you, all this work can be performed by them or by them in concert with you. Work with your agent but don’t feel that your agency agreement precludes you from pitching in and being an active author. Be a diplomat and work to sustain your career, protect your books and earn the income that you deserve.

Authors who are self-published or hybrid

Many self-published authors run complex, small businesses in addition to being prolific writers. Though for the most part they are dealing with a very different landscape, they also have to manage a great deal of information about their books and think about the future. With multiple accounts paying monthly balances, it’s key to be organized. Below are just some of the many items you need to keep track of.

What platforms are you on? Review their sales.

What platforms are you marketing on? Are you also creating social media ads and leveraging other channels?

Are you in Kindle Unlimited or are you using a “wide” model with distribution at many retailers?

Is it time to change your cover or price? Are there any other promotions out there worth exploring?

What rights have you licensed out? For how long?

What rights do you still control? What can you do with them?

Literary executors and estate planning

Besides generating more income for yourself, it’s important to track these licenses and agreements for your heirs. You may not be immortal, but the books you’ve written could be. This is true especially if you make arrangements in your will for who will manage your literary estate after you are gone.

A literary executor is the person entrusted with the management of a deceased author’s literary property (published and unpublished), including overseeing copyrights, making and maintaining contracts with publishers or book retailers, licensing rights, and collecting royalties.

You can designate any willing person to be your literary executor. But it is best to pick someone who understands publishing, who can ensure your works are handled so that they continue to be available to readers and generate income for your heirs.

Having all this information in one place makes it easier for you—and, in the future, your literary executor—to track all your contracts. Decisions must be made on how to generate the greatest earning potential for the length of the copyright plus 70 years after your death. I know estate planning and thinking about your will can be uncomfortable, but preparing and organizing your intellectual property information is the best way for your books to continue to generate earnings now and for decades to come.

Note from Jane: Ethan Ellenberg has created Royalty Reminder, a software platform that offers a cloud-based searchable index of all your contracts and sends reminders about contract expirations and royalties due. It also helps you track which licenses remain in your possession. Authors can now create their own accounts, and Ellenberg is seeking beta testers to help him make the tool as useful as possible for all authors. You’ll get three months free, with no cost for onboarding. If you’re interested in being part of an early group of writers shaping what this platform looks like, please contact Ethan.

October 11, 2019

Loss: The Exact Reason to Read and Write

Given the times we live in, I’ve noticed more articles and books, for writers and artists, discussing the value and importance of pursuing creative endeavors, such as:

Keep Going: 10 Ways to Stay Creative in Good Times and Bad by Austin Kleon

Your Art Will Save Your Life by Beth Pickens

The Gift by Lewis Hyde, first published about 40 years ago, re-released this fall

In the latest and final Glimmer Train bulletin, author Bret Anthony Johnston writes eloquently about the losses we’re all now experiencing—including the loss of Glimmer Train itself. (Its last issue has now been printed and sent.) He says:

[Loss] can make fiction—reading it, writing it—feel like an obnoxious waste of time. And maybe it is. … But what if all of this loss is the exact reason to read? To write? This is what I keep thinking; this is the rope to which I cling. What if stories are the light that will enable us to navigate the dark?

Read his full piece, Even in the Gathering Darkness.

As anyone who’s read Glimmer Train knows, it has been a publication with a singular and special mission, not once veering off-course. I greatly admire how its founder-editors have chosen their exit; may the light of their work shine for many years to come.

October 10, 2019

Manuscript Evaluations: What They Are and What to Expect

Photo credit: e-magic on Visual Hunt / CC BY-ND

Today’s guest post is by freelance editor Sarah Chauncey (@SarahChauncey).

Whether you’re writing a novel, memoir or how-to book, a manuscript evaluation can be an economical opportunity to have your work reviewed by a professional editor before you begin querying and submitting. It ideally happens only when you’ve taken your manuscript as far as you can—since it’s not going to do you much good if your feedback consists of comments about revisions you already know you have to make.

A manuscript evaluation is a high-level analysis of your manuscript through multiple lenses:

Structure. Does the story advance appropriately? How are characters introduced and developed? How is the pacing?

Story. Are the stakes high enough? Is the story goal clear? Is the voice or perspective clear or strong? Does it earn each plot development? Does it require more suspense (or sensuality, or action)?

Mechanics. Are there recurring grammatical issues? How effective are your word choices, including adjectives and adverbs?

Genre. For genre fiction, does the manuscript follow the accepted conventions?

A Manuscript Evaluation Is Not Developmental Editing

A manuscript evaluation is much less detailed than a developmental edit and therefore will almost always be less expensive. Developmental editing is a deep-dive edit that takes significantly more hours than a manuscript evaluation. For example, during a developmental edit, I do multiple deep reads (and then look away and come back). I often make hundreds of comments. I might rewrite lines or paragraphs to show the author what X technique looks like. And I pose lots of questions, asking the author to be more specific, go deeper, or show how they might develop a given idea in an earlier chapter. (One editorial letter I wrote was 30+ pages—one client called it a personalized writing handbook.) So, it’s far more comprehensive than a manuscript evaluation; however, it’s also proportionately more expensive.

If a developmental edit involves asking the author multiple questions, a manuscript evaluation gives you a high-level overview of what works and what doesn’t. In an evaluation, I might refer to books, blogs and other resources that explain a given concept in depth.

If you have tons of notes or chapter drafts, or if you’re not yet clear what story you’re telling, or if you don’t have a cohesive manuscript yet, developmental editing is probably more appropriate for you.

A manuscript evaluation letter typically runs a few pages, usually no more than 10 pages. Some editors (not all) include light markup as well because the editorial letter can often seem abstract. The markup makes the concepts more concrete and directly relevant. For example, I might show where the author has successfully used a strong metaphor, or written great dialogue. I also comment on passages or single lines that can help the author connect the abstract, overarching comments in the editorial letter to specific moments in their work.

Below are other types of editing you might hear about. The variety of names used for each level of editing can be confusing; when in doubt, ask the editor to explain their definition:

Structural editing. A structural editor helps you to find the right structure for your manuscript. This is a big-picture edit, more creative than technical.

Content editing. Also called substantive editing, comprehensive editing or heavy editing. This is a macro-to-micro edit that blends structural and line editing.

Line editing. Also called stylistic editing (Canada), this type of edit focuses on making sure the writing is clear and tight, as well as improving the flow of your manuscript.

Copyediting. A detailed, technical edit to make sure the writing is as tight and complete as possible. Copyeditors check grammar, correct usage, spelling and punctuation.

Proofreading. A final word-by-word review and polish for punctuation and spelling.

A manuscript evaluation may touch on any of the above areas if it poses a problem for getting your work accepted or published. For example, if you consistently punctuate dialogue incorrectly, an evaluation will mention it, but not correct it for you.

Partial Manuscript Evaluations and First Pages

If you’re seeking feedback on specific areas you’re unsure about, some editors offer a partial manuscript evaluation. And some will review your first 10 or 50 pages. In most cases, editors can spot recurring writing issues in a 5,000-word sample, from passive voice to flat dialogue. We can probably glean enough to know whether the writing flows, and to address storytelling skills, use of dialogue and exposition, among many other stylistic issues.

However, there are many things editors can’t address with a short excerpt: overall structure and plot, character development, arcs, themes, and other full-manuscript expressions of story. An editor simply doesn’t have enough information to offer useful feedback in these areas.

What You Can Expect to Pay

Most reputable editors who offer manuscript evaluations charge in the same ballpark: $300 to $500 for a partial manuscript evaluation (typically 20-25 double-spaced pages), $1200 to $1500 for a full manuscript up to 60,000 words. Most of us will evaluate longer manuscripts and either bill a small per-word amount after the initial 60,000, or a stepped increase, like $250 for each additional 10,000 words. Beware of too-good-to-be-true prices. A manuscript evaluation, properly done, takes quite a bit of time, energy and knowledge.

Depending on how you file taxes, the expense of a manuscript evaluation (and other editing/publication expenses) may be deductible. Check with your accountant.

Finding the Right Editor

Hiring an editor can be a surprisingly difficult decision. As human beings, we have different worldviews and life experiences, different personalities and communication styles. Many of the new clients I’ve worked with looked at several editors before making their decision.

Ask writers in the same genre as you for recommendations. Read editors’ blogs and see whether their style resonates with you. If you’re writing an academic book, look for editors experienced in your field, if possible. Also, most freelance editors will make available on their site (or by request) a sample editorial letter from a past project. That way you can see the editor’s communication style and what type of feedback you can expect.

October 9, 2019

The Seductive Power (and Danger) of Metaphors and Similes

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Submit your first page for critique.

First Page

Sometimes you wake up with a hole in your heart and you’re not sure why. It’s a circle, carved by something you can’t touch, something that opens up in your sleep and wakes you up, hungry. This morning, before I got on the plane, it was like that, like those lagoons left by old, erupted volcanoes. They pull things and people into them because the core of the earth, after it’s shot out molten lava, is as hungry as I am.

Now, from 10,000 feet in the air, looking down at all these street grids, I still feel the hole in my heart. And the free-fall between me and the messy muck of being in the city again. I hate New York. Because when you’re there, inside the grid, you can’t see the whole picture, just what lies in front of you; you can get lost. Not like painting, where whether you’re inspired to the point of bliss or you think you’re losing control, the canvas is always there—whole in front of you like a map—and you’re the one drawing lines of perspective. You can always find your way out.

Landing in LaGuardia all alone, it’s cold. I forgot what this felt like, the sharp invisible burn through your clothes, going straight for the bone. I zip my jacket, wrap my scarf, and off I go onto the M60 into Manhattan. Straight through Queens. The houses with Christmas lights still on from six years ago, even in September; nothing’s changed. Strolling through Harlem—an Old Navy now near the Apollo—and then there I am on 110th street, getting on the subway, on my way to Chelsea to see Lee. Lee, who told me to get my “painter ass” over here because it might change my life. And my life needs some change—in every sense of the word; in my pockets, definitely.

First-Page Critique

The invention of airlines has fostered a grand tradition of novels and stories opening at cruising altitude, with characters bound toward (or departing from) the places where their stories have taken or are about to take place. One such novel, Erica Jong’s scandalous Fear of Flying, honors that tradition through its brilliant opening line, “There were 117 psychoanalysts on the Pan Am flight to Vienna and I had been treated by at least six of them.” Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses twists the convention by opening with its protagonists in mid-flight in more than one sense, having literally tumbled “without benefit of parachute or wings” out of their hijacked, blown-up jetliner:

Gibreel, the tuneless soloist, had been cavorting in moonlight as he sang his impromptu gazal, swimming in air, butterfly-stroke, breast-stroke, bunching himself into a ball, spreadeagling himself against the almost-infinity of the almost-dawn, adopting heraldic postures, rampant, couchant, pitting levity against gravity. Now he rolled happily towards the sardonic voice. “Ohe, Salad baba, it’s you, too good. What-ho, old Chumch.” At which the other, a fastidious shadow falling headfirst in a grey suit with all the jacket buttons done up, arms by his sides, taking for granted the improbability of the bowler hat on his head, pulled a nickname-hater’s face. “Hey, Spoono,” Gibreel yelled, eliciting a second inverted wince, “Proper London, bhai! Here we come! Those bastards down there won’t know what hit them!”

The first page under scrutiny here, while offering no such sensational thrills and spills, plants us firmly in the tradition, with a painter poised to descend upon the New York City he or she left behind some unspecified amount of time ago, without regret, apparently, since she/he still hates the place.

If a successful opening is one that raises intriguing questions while providing enough information to ground the reader, this opening certainly succeeds. On the one hand, we know the protagonist is an artist (though of what sex and age we don’t know; doesn’t matter, we’ll find out soon enough). We know that New York City has left a bad taste in her (let’s assume she’s a woman) mouth. We know, furthermore, that for some reason she has been compelled to return—possibly against her wishes. We know too that the protagonist is poor, or at any rate not flush. Else why travel into the city from the airport by bus—and by way of Harlem, to boot?

The author opens with a metaphor—a vague one about a hole in the protagonist’s heart. Like all descriptions of feelings, though it tries through metaphor to obtain some concreteness, it remains abstract and subjective. However, no sooner does the author plunge us into subjective territory than she grounds us aboard a passenger jet at 10,000 feet.