Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 81

June 16, 2020

Writing, Pitching & Promoting in the Age of the Coronavirus

Today’s guest post is a Q&A by Sangeeta Mehta (@sangeeta_editor), a former acquiring editor of children’s books at Little, Brown and Simon & Schuster, who runs her own editorial services company.

Like everyone in the book industry, writers have experienced considerable change over the last few months. Although they might be used to working from home, being forced to do so has impaired creativity and made it nearly impossible for some writers to focus. For others, being under lockdown has provided just the right push for them to finally finish their book project and research agents and publishers.

For those writers who are able to work at this time, questions loom:

If they’re writing fiction, should they adjust their story to reflect current events?If they’re already published, can they effectively promote their book through social media?What’s the best way to help fellow writers, booksellers, and others who may be struggling?I asked literary agents Stefanie Sanchez von Borstel of Full Circle Literary and Leslie Zampetti of Dunham Literary, Inc. these and other similar questions, and as with all my Q&As, neither knew the other’s identity until after they submitted their answers.

Please note: Although both agents answered my questions as best as they could when the interview was conducted in May, it’s a very changeable situation. Still, their answers suggest that it’s possible for writers to thrive even during unpredictable times.

Sangeeta Mehta: Many agents are advising fiction writers not to write about the pandemic, urging them to write something escapist or uplifting instead. Do you agree, even though the books being written now won’t be published for a couple of years, and the world might be ready for pandemic fiction by then? Would subplots or references to the virus be appropriate or expected?

Stefanie Sanchez von Borstel: While we’re all still deep in the pandemic, I am advising fiction writers not to center on the pandemic. We’re inundated with COVID-19 news 24/7, and so much is changing week-by-week that it would be difficult right now.

For fiction projects, at the moment I’d prefer to represent feel-good stories and stories that explore our humanity rather than pandemic fiction. As we’re all trying to figure out how best to navigate work, school and family life, I think we can all use laughter, hope and happy moments.

Since I work with many writers of fiction for young readers, I am also concerned about young people today. Rather than focusing on the virus, which has brought so much pain and loss to many, I am encouraging my clients to dig deeper to write about people and experiences that are most meaningful to them.

Leslie Zampetti: My advice to writers stands firm: write what you need to write. Write what you’re good at. Write what excites you. Trying to chase trends will drive you crazy. I do feel that writing about the pandemic while in the midst of it is challenging. Getting your thoughts and reactions down while they’re fresh, as they happen, can be cathartic and provide material for a later book, but I feel that trying to write a novel based on the pandemic means writing about events and emotions none of us have fully processed yet.

Not writing about the pandemic doesn’t mean you’re not thinking about its impacts. Leaving out those impacts will place a book solidly pre-2020, just as details about flying place a book either pre- or post-9/11. Details matter. I’m advising my clients writing contemporary fiction to think about how the pandemic would affect their characters, even if they’re not writing about it yet.

How should those writing fiction that takes place in 2020 and beyond deal with the societal changes we’re all experiencing? For example, should their characters meet up on Zoom and wear masks if they leave their homes? Should coronavirus vocabulary, which has now become ubiquitous, be incorporated into their dialogue?

SSVB: My advice is to encourage writers to continue with their works-in-progress as planned. Manuscripts selling this summer will be published in 2022 and beyond. As quickly as COVID-19 has changed our world from just two months ago, in a few months or weeks there will be more changes.

Even for fiction manuscripts with delivery dates this month, COVID-19 references are not being incorporated. My suggestion is to write what feels natural and don’t attempt to incorporate all of the societal changes happening right now. Any specific COVID-19 vocabulary/references can be addressed with your editor closer to publication.

However, I’d recommend keeping a written journal and photo/video journal documenting what is happening in your family and community. At a later time, you may want to incorporate COVID-19 vocabulary or references into your fiction, and can use your primary resources.

We just attended a 12-year-old’s Zoom surprise birthday party and a school graduation car parade. These were firsts for our family! Document everything since we’re living through history and these moments might become part of a story one day.

LZ: Speaking of details! These are choices a writer has to make consciously. Is their book intended to be of the moment, or is it okay that it’s obviously pre-virus? The details have to feel organic, woven into the world of the book and not just sprinkled in.

One concern of mine is that we’re living so completely in the present these days. We don’t know what the future holds, and it likely will look different in different places. For example, those of us living in crowded cities will probably be wearing masks for the foreseeable future—but will people living in suburban, rural, or isolated areas do so?

I do think that writers will have to allow for common changes in vocabulary and action, just as they have had to allow for other societal changes like technologies (cell phones), political movements, social mores and etiquette, etc. These choices need to be made thoughtfully—for example, choosing to write a YA novel without cell phones simply because it’s easier logistically is a lazy choice and one that signifies a weakness in the plot.

How is the pandemic changing how you are pitching manuscripts to acquiring editors? For example, are you submitting less frequently and more cautiously? Are you finding that publishers are more responsive but less willing to take risks? Or is business continuing (almost) as usual, as this piece from Publishers Marketplace suggests?

SSVB: While agents are handling submissions in different ways, I am continuing to pitch and submit projects in specific areas. I represent many children’s books and nonfiction projects, which, according to the Publishers Marketplace and Publishers Weekly reports, are two of the areas continuing to see strong sales during the pandemic.

(BTW, Publishers Weekly, the publishing industry trade magazine, is offering open access for all to digital issues of PW during COVID-19. Here is a link where readers can keep up with latest book news and reviews.)

Editors have been very responsive, especially to middle grade submissions. Most editors tell me they are looking ahead to the future. This week, I just closed an auction on a middle grade novel that resulted in a two-book, six-figure deal. Yet the key is to send projects that will stand out.

I’m seeing response times are split. Some editors have shared they have more reading time right now, and are responding to submissions within a couple of weeks. Other editors have less reading time as they juggle working from home and family schedules, and are letting us know they will be taking longer to read. I’m doing my best to keep communication open on projects to accommodate varying schedules and response times.

LZ: Every agent is different. I’m submitting in smaller rounds and focusing even more on editors with whom I’ve connected. I’m finding that editors are eager to meet virtually and talk about their changing wish lists. Responses to pitches and submissions seem to be slower than usual in some cases, likely due to the constraints editors are experiencing while working from home.

School and public libraries are a big market for children’s books, so I hope that we’ll see increasing stability and purchases from them in the fall, whether schools re-open or virtual education becomes more successful. That would boost publishers’ confidence, hopefully meaning more acquisitions.

But business is continuing: I have several submissions out and recently made a deal.

Do you have any suggestions for authors who are promoting books that have recently released or are about to release? For example, should they avoid referring to the pandemic, or could that be seen as inconsiderate or irresponsible? Do you think authors will be encouraged or required to make themselves more visible on social media as publishers rely more on online marketing? Will virtual book tours likely become standard?

SSVB: We’ve had several titles released this spring and summer releases coming soon, and my advice is for authors to embrace the situation and try to think creatively about how to make changes work for you. If you’re going to be home with your kiddos 24/7, how about getting your kids involved?

For example, debut author Adrianna Cuevas filmed a video with her 12-year-old son baking guava pastelitos (favorite food of main character Nestor Lopez in her book) to share both her book and a baking activity. She also photographed her son doing a reenactment of the front cover of her book, The Total Eclipse of Nestor Lopez, which is coming out this July. Families can enjoy these together and might be inspired to reenact book covers or try foods featured in their favorite books. Hopefully they pre-order, too!

Virtual book tours, online panels and read-alouds are now accessible to more readers. These online events can be attended by everyone everywhere and archived for sharing. For example, I enjoyed the recent Everywhere Book Fest! This festival brought together authors with spring releases who had launch events cancelled, and I hope these online festivals become standard (in addition to the live festivals, if possible!). Several authors are pairing up for Q&As or participating in multi-author events that would have never been possible before due to geographic limitations or scheduling.

LZ: We’re all looking for good news these days, and a book birthday is always good news!

I don’t think authors need to apologize for promoting their books, but the purpose of social media is to connect with others. It’s a two-way street. Celebrate and promote your book, but also offer something to your audience. Maybe writing advice, or little extras about your characters, or just encouragement in these difficult times.

Virtual book tours are both a blessing and a bane. Making events available to people who don’t have access to in-person book launches, discussions, etc., is wonderful. But we need to be concerned about accessibility for those who lack good devices, access to broadband, or accommodations for disabilities. If virtual events become standard, then we need to pay attention to how they can become another way of privileging certain groups of people just as in-person events have.

There’s also a difference in the energy and joy between in-person and virtual events. Try to harness that joy in your promotions, whether through video, emoji, or even exclamation points!

Given that the traditional publishing route has always been uncertain, and self-publishing might give writers a sense of control, would you encourage those who have already been considering self-publishing to go through with it? If so, should they focus on creating ebooks and audiobooks since such formats are probably easier to sell at this time?

SSVB: Traditional publishers are trying to navigate printer closures, shipping/warehouse restrictions, and distribution to readers in the midst of bookstores, libraries, and school closures. Ebooks make the most sense in the current market, especially if you have a timely topic. While I don’t have enough experience with self-publishing to share concrete suggestions, it seems like a challenging time for writers to self-publish since they’d need to manage these extra distribution challenges, in addition to editing, designing, marketing, etc.

LZ: Self-publishing requires a tremendous commitment from an author if it’s going to be successful. My usual advice applies: if there’s a highly targeted market that isn’t served by traditional publishers, and/or if the author is willing to put in the time, effort, and money needed, then it can be a positive experience. Self-publishing looks easy, but there’s a reason that publishers have editors, copyeditors, designers, and many other roles contributing to the process. Does the author have the energy and expertise to fill those roles, or do they have the funds to hire freelancers?

If an author is determined to self-publish, I would recommend focusing on ebooks right now, because there are supply chain issues with hard copies. That doesn’t mean cutting corners on editing or design, though. Audiobook narration is a specialized skill; the narration makes or breaks the reading experience, so I’d be careful about focusing on that format.

Just as the pandemic has magnified the class divide in our country, in that lower income populations tend to be at a higher risk due to their living and working conditions, is the same happening in the writing community? After all, most writers can’t just escape to the countryside and instead have to keep working second or multiple jobs. How can this latter, already disadvantaged group take back any strides they may have achieved in recent years?

SSVB: Not sure how to answer this one. As a Latina working in publishing for 25+ years, I don’t agree that underrepresented writers have made significant strides in recent years. According to the latest Cooperative Children’s Book Center statistics available for children’s books, Black, Latinx, and Native authors combined wrote only 7% of new children’s books. Only 34% of books about Latinx were by Latinx authors/illustrators and only 29% of books about African/African-American people were by Black authors/illustrators.

Most of my clients have full-time jobs in addition to writing, and parents are now carrying the extra responsibility of 24/7 childcare and home schooling. At the same time, there continues to be misrepresentation of underrepresented groups, as book creators, agents, and editors do not reflect our society. A statistic that stood out in Lee & Low’s 2019 Diversity Baseline Survey: the percentage of people in editorial positions who identified as White increased from 82% in 2015 to 85% in 2019.

I’ve had a long commitment to underrepresented writers and artists, and I strongly believe that each successful book we represent opens the door to new writers and artists. So although this is a challenging time, we all press forward!

LZ: This is a difficult question. Current conditions are obviously exacerbating inequalities in the writing community. (Though virtual events should help if they are accessible to all and offered at a lower cost.)

The burden of reclaiming the small strides that have been made should not be placed solely on those who are disadvantaged. Those of us who are more privileged need to consider what we can do to keep the focus on marginalized voices and help to make opportunities available, like donating critique opportunities or helping to provide scholarships to events. I work with organizations like Dominican Writers and Inked Voices to encourage these voices.

Common advice is to keep writing. Writing means effort and time spent thinking, dreaming, reading other work—and that is the hardest time to claw back from other responsibilities. How do you choose to write for 15 minutes instead of sleep when you’re already drained from working, caring for others, making your voice heard?

On the one hand, writers are hearing that they shouldn’t pressure themselves to write or worry if their books aren’t selling, but on the other hand, they’re being asked to donate to independent bookstores and writing organizations undergoing financial hardships. Is there a way to strike the right balance between focusing on their individual careers so they have the means to donate, and keeping our literary ecosystem healthy so that all can benefit?

SSVB: The pandemic has impacted writers in many different ways as they also navigate childcare needs and extra support to families and neighbors. Taking care of yourself and your family needs to come first.

I admire writers Shea Serrano and Celeste Ng for funding scholarships and grants to support writers and interns from diverse backgrounds. However, there are many other ways to give to the writing community such as volunteering your time as a mentor to writing organizations or pitch events, offering critiques to new writers, or providing guidance to debut authors based on your experience. Boost links and drive your readers to the online bookstore Bookshop.org or to the audiobook service Libro.fm, both of which designate a portion of profits to the indie bookstore of your choice. Writers can offer to host virtual author events or giveaways with book sales directed to their local indie, building a mutually beneficial relationship.

LZ: I firmly believe that we need to take care of ourselves right now. And if that means focusing only on your individual career, then make a note to yourself to pay it forward later on.

But giving to others benefits the giver as well, and donations of time and/or effort are just as important as money—maybe more so, given the high opportunity cost of time for many writers. Writing down budgets or mapping out schedules on a calendar can help make visible how much time and effort you have available to help others.

Will you have more impact locally or by participating in large organizations? Making small choices, such as linking to indie bookstores instead of Amazon, can have plenty of impact. Consider where your donation can have the most impact.

According to a recent Publishers Weekly campaign , “Now more than ever, books are essential to the well-being, education, and entertainment of our society and culture.” Not everyone agrees with this statement, however. Do you have an opinion on this issue?

SSVB: During this uncertain time, I’ve come to realize how much I value all of the people that make books and get them into the hands of readers. I miss stopping by my local bookstore, Run for Cover Bookstore, regularly to pick up books for gifts and weekend reading. Now that my sixth grader son is deep into online school from home, I have a renewed appreciation for teachers and librarians who use books creatively with students.

I’ve come to appreciate even more the editors that take extra care in every detail and the publicists who champion a book with new opportunities as the marketplace has changed so suddenly. I am grateful for editors and art directors who are looking ahead to the future.

LZ: I would say stories are essential. Connecting with others through books is essential. Educating oneself about other perspectives, other places, and other experiences is essential. But to say “books are essential” implies that booksellers and the workers who make up the supply chain for publishing are essential, and I don’t think that most of those employees are being supported as if they are.

However, I can’t imagine life without books. I can imagine never travelling again, or not eating out, or not enjoying museum visits. Even not being able to watch movies or TV. But not reading? No.

How would you describe the writer who is most likely to withstand all this uncertainty and come out of the pandemic stronger than before? Do you have any other advice for writers on how to navigate the new publishing terrain we’re currently living in?

SSVB: The writer with perseverance and commitment will withstand the pandemic. Loads of patience helps! We’re all hearing about some of the greatest accomplishments that have occurred in difficult times in history. Newton began observing laws of gravity when he was forced to quarantine in Cambridge during the Great Plague. So who knows what will come out of our quarantine?

As we’re living through these uncertain times, keep observing. Keep writing. Keep illustrating. Continue to revise and work on new projects, consider trying something new (a new genre or writing for a different age group than your past works) to give yourself an extra challenge. With summer almost here, enjoy time reading and listening to the birds!

LZ: Persistent and patient. That’s a good description for writers at any time.

Inform yourself as best you can about the changing conditions of the industry, and then focus on the positive. Focus on the things you can control—your craft, your writing habits, your creativity. Focus on the reader who needs your book, whoever that may be.

Stefanie Sanchez Von Borstel (@fullcirclelit) is a literary agent and co-founder of Full Circle Literary with 25 years of experience in publishing. Prior to agenting, she worked in editorial, publicity, and trade marketing with Penguin and Harcourt. Since she is currently at home reading lots of middle grade lit with her 12-year-old, Stefanie would especially love to bring more exciting middle grade writers (contemporary, historical, magical realism, narrative nonfiction) and graphic novels to her list! Find out more about Stefanie and Full Circle Literary at .

After years of experience as a librarian and writer, Leslie Zampetti (@leslie_zampetti) became a literary agent with Dunham Literary. Her clients include Ann Clare LeZotte (SHOW ME A SIGN, now available) and Lisa Rose (THE SINGER AND THE SCIENTIST, forthcoming). For children, Leslie represents picture books through YA, but middle grade is her sweet spot. Right now, Leslie is seeking more humor (dry or sweet, not gross), mysteries for all ages, and friendship/sibling/found family stories. For adults, Leslie is seeking upmarket mysteries and romances. Inclusivity and stories by marginalized creators are a priority.

June 15, 2020

Stop Staring at a Blank Page: 4 (Not So) Silly Writing Tips to Get Words on Paper

Photo credit: matthewebel on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-SA

Photo credit: matthewebel on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-SAToday’s post is by editor and book coach Sandra Wendel.

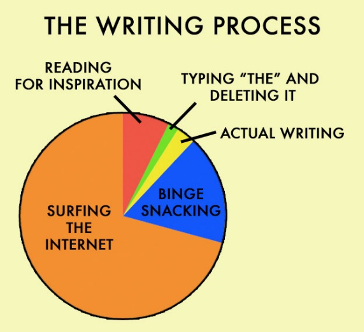

Imagine the first writer’s block: perhaps a caveman with a rudimentary stick staring at a large, blank rock. Today’s equivalent of the blank rock may be a computer screen, and your process may seem like the pie chart below.

When you sit down to write (and there’s a problem right there; you may not do well sitting down), do you find yourself with a sudden urge to clean out a file drawer? Throw in a load of laundry? Search the internet for ways to clean wine stains out of carpet? Check the refrigerator for the third time? Bake a cake instead?

You have something to say, but what’s holding you back?

In my writing classes, I ask my students to consider this question: When you go somewhere new, do you prefer to tap the address into a smartphone GPS and hear the turn-by-turn directions? Or do you stop and ask directions? Or do you just want to see the map? Maybe you wing it and get lost before you stop and ask directions. Which technique do you use?

If you want to hear the directions, you are an audio learner. If you want to see the map, consider yourself a visual learner. And those who wing it would be considered kinesthetic learners.

Let’s translate that into writing techniques.

1. The I-Need-to-Hear-It WriterThe audio learner may well be an audio writer. You are easily distracted by sound. So the birds chirping outside take your attention away from the computer. The furnace clicking on and off, the clock ticking, the refrigerator cycling, a hum from somewhere—all distract your brain from the task at hand.

Audio writers are fascinated with sound, and we can harness that ability to help in the writing process because audio people are often magnificent storytellers. Capture those thoughts in words by dictating a story, a scene, a paragraph, a description of a crowded train station.

I recommend the Voice Memos on your iPhone and various speech-to-text apps like Speechy (free) and Dragon (paid) that turn your sounds into words. You then email those dictated files to your computer and have raw words on paper, so to speak, without keyboarding.

Another app called Rev captures sound/dictation and even conversation among two or more people. You send off the files to their transcribers and have written text within hours (for a fee based on per-minute recording). I’ve worked on memoirs written, rather dictated, entirely on Rev. I use Rev for interviews and oral histories too.

Your version of Word may already have speech-recognition software built in. All you need to do is get an external microphone (or headset) and talk to yourself. Use the Help feature and search text-to-speech for directions on finding this well-hidden bonus you may have right in front of you.

Desperate to just capture a thought and you either have no paper or pen or hands free to write? Phone yourself and leave yourself a voice message.

Another option is to tell your story to someone else, in an interview format. Use a recorder.

2. The I-Need-to-See-It Writer

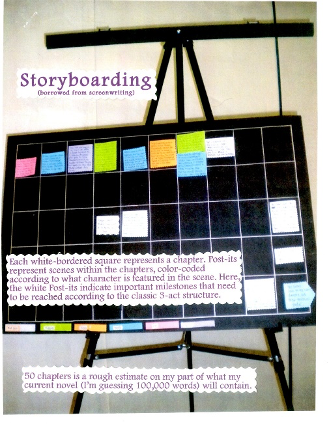

The visual learner needs to see the big picture. These writers make outlines (outlines can turn into the book’s table of contents). They use index cards for ideas and shuffle them or lay them out on a table to visually see the story as it unfolds. Post-It notes do the same thing when placed on a board or table, as a storyboard. Others may simply draw out the plotline through time for each character.

Do you identify with this type of writer? I don’t know about a thousand words, but doodles and drawings can sometimes make the unclear clear, like when I was buying special nails for affixing new siding, and the associate was saying, “Blah blah blah,” (that’s what I heard until I asked him to draw a picture). Do you ever find yourself telling someone to “draw me a picture” or drawing one yourself?

Example of a mind map

Example of a mind mapThe act of drawing will help you organize and “see” the story. A mind map, therefore, is you drawing a picture of your plot, your characters, your complete story, a chapter, a through line, a story arc. Your central theme is usually the center point, and the subplots or characters branch out from that main theme. It’s like an outline. Yes, and even a tried-and-true outline is an ideal way to lay out your book (especially in nonfiction). Outlines don’t need to be elaborate or detailed, and you don’t need software, just a page of notebook paper. Mind maps can help you visual writers get started.

3. The Quirky Kinesthetic WriterNeither visual or audio driven, the kinesthetic writer needs movement, which is why sitting down at a computer/laptop isn’t going to work well.

So stand up. Put your laptop on the kitchen counter. Take a walk and then come back and dump your brain onto paper.

We know the best ideas come when we are least expecting them. Thus the brain is tricked, during activity, to trigger a bright idea. Do you know the three most common scenarios for ideas to jump into your head (P.S.: Those ideas are already there.)? The answer is while sleeping, driving, or taking a bath/shower.

What is it about water? If you’re stuck for an idea, wash the dishes. Put your hands in water. Or take a bath. I go kayaking.

If those ideas pop into your head while driving, be sure to grab your dictation device and capture it. Or for god’s sakes, pull over and write it down.

Use the sleeping trigger to set your intention before you go to bed. Keep a paper and pen or smartphone dictation device handy so you can brain dump it the moment you awaken.

One of my kinesthetic authors was writing about barefoot running. He would take long runs and return to his computer with a jumble of ideas and thoughts and brain dump immediately into his computer. Sometimes he’d type, but as his thoughts came too quickly for his fingers, he’d dictate on voice recognition software.

Some writers need to change their venues. That’s why we hear about prolific novelists such as William Kent Krueger thanking the staff in the coffee shops where he writes for allowing him to commandeer “booth #4” for far too long. Or Malcolm Gladwell who seeks out coffee shops when he travels, less for the brew and more for the right kind of distracting atmosphere.

For some of us, our blank pages can be electronic or something else. Yes, some authors continue to write out their books on yellow legal pads. One woman in my class confessed to typing on an old manual Remington Rand.

4. Start at the Beginning—or NotWhen you are wondering where to start, just jump in. Anywhere. Somewhere. And not necessarily at the beginning. Write what feels right at the moment without the pressure to start at the beginning.

People writing memoirs like to start at the beginning chronologically, and that’s fine to start with. But a smart editor can often see the big picture and move something life-defining to the opening chapter as a grabber for readers.

I worked with a bank robber, Richard Stanley, who grew up in a gang-controlled San Diego neighborhood. The influences of his surroundings were tough to break out of. In fact, he started robbing banks and ended up in prison for nearly eight years.

He started his story when he was doing petty shoplifting and stealing CDs from Target and reselling them to his classmates in the fourth grade.

I revised the narrative to start with the defining moment in his life: his first adrenaline-powered, hands-sweating bank robbery. A stolen getaway car, hasty disguise, a quickly scratched note—“Put the money on the counter”—and the need for cash to buy a meal at Taco Bell. As his story unfolded, we dipped back into the events of his tumultuous childhood.

The lesson here is that Stanley started his manuscript at the chronological beginning because that was comfortable to him, then had an editor help reorganize. Editors can deliver stunning results when you have the materials all there in the first place.

Parting AdviceNo time to write? Make time or schedule the time. Get up early and grab some time before work or school. Say no to outside activities. Start with just five minutes a day. Then increase it to ten minutes. Build the habit of confronting the blank page.

June 9, 2020

How to and (Especially) How Not to Write About Family

Today’s post is by Sharon Harrigan (@harrigan_sharon), whose novel Half is available now.

Writing about the people you are closest to can be one of the most rewarding experiences a writer can have—but also the scariest. This is a big topic, so I will cover it in two parts. First: what to put on the page. And second: how to deal with your subjects’ reactions to what you write about them.

Let’s start, as some of my favorite memoirs do, with a cliffhanger. Here is what you should not do: When your publisher gives you a January 1 deadline for submitting the final manuscript, you should not print out a copy for each of your family member-characters and send those copies all at the same time, which guarantees you will receive their responses right before Christmas.

But who would do that? Such recklessness would be really dumb, right? I know. At least I know now. But I’ll get back to my own experience later—so you can learn from my mistakes. First, let’s talk about best practices when writing about your family. (All quotes are from Writing Hard Stories, edited by Melanie Brooks.)

Don’t worry about what your family will think when you’re writing the first draft.One way to invite writer’s block is to imagine the people you are writing about looking over your shoulder. “I try to just write alone and worry about the publishing part later,” Joan Wickersham says. “My feeling is you can write whatever you want, and then you think about it again when it’s time to publish.”

Richard Hoffman adds, “Writing and publishing are two different things. Don’t confuse them. As soon as you start thinking, I could never publish that, then the censor is in the room with you crossing stuff out as fast as you can write it. You can’t work that way.”

Examine your motives.Don’t write out of revenge. If your purpose is to get even or settle a score, consider waiting until you have processed the experience enough to not be angry about it, or at least enough to have some distance and perspective. You may need to write about things that will be hard for your family to read, but avoid being, as Joan Wickersham puts it, “gratuitously nasty.” “I didn’t want [my memoir] to be nasty,” she says, “both for my family, but also because I’ve read memoirs like that—where you feel there’s an axe to grind—and it always makes me back away from the memoir and not really trust the writer.” Readers don’t need to like the narrator of a memoir, but they need to trust her as their guide, or they will close the book.

Also: “You really don’t need to hurt anybody,” says Abigail Thomas. “The person you’re exposing is yourself.” But what if some people in your family behaved badly? You can’t lie and pretend they were model citizens. Thomas’ solution is simple. She says, “People who might be injured simply don’t appear.”

Tell your story only.If you don’t pretend to be able to tell everyone’s story, readers will trust that you know your material. As Michael Patrick MacDonald says, “I only told stories that are my stories. Of course, they involve other people, and that’s the problem, but I only told parts of their stories if they intersected with my trauma.” Kim Stafford, who writes about his brother’s suicide, says, “There is no way I can tell my brother’s story … Instead, I write my stories of my brother.”

Treat some people with extra caution—for example, children.All the memoirists I’ve heard talk about this say children are more vulnerable and need to be treated with more sensitivity. For instance, at an AWP panel on this topic, one writer said his rules are to respect the secrets his children would not want repeated, including anything mental-health-related. Another said she gave her children carte blanche to change how they were portrayed, a privilege she didn’t give anyone else, and another said she kept asking for her nineteen-year-old son’s okay, even though she didn’t ask any of her other characters.

Write down your own memories before you ask other people to fact-check you.Memoir is not about what you remember but why you remember it that way. Your subjects will try to correct your facts, so wait until you have arrived at the emotional truth before that gets buried in the controversies about the literal or physical truth.

Monica Wood says, “I deliberately didn’t ask [my siblings] about family history. I wanted it to be my memory.” Mary Karr, in The Liar’s Club, sometimes stops in the middle of a paragraph to add a parenthetical telling us her sister remembers the scene she just described differently. You might choose to do that, though it is a difficult technique to pull off without sounding gimmicky. Even if you don’t write like Mary Karr (and how many of us can?) it is best to keep your memories distinct from those of others.

Should you give your family control over the work, or ask for permission to publish?Writers tend to agree on the above guidelines while drafting. There is a lot less consensus about what comes after. How much control should you give your subjects—those family members you have turned into characters? What should you let them see, and when? Will you allow them to change anything?

One question you will have to grapple with is whether to allow some people to say you can’t write about them. Before I started writing my memoir, I asked for my mother’s permission to use the stories she had been telling me about her life, and I would not have proceeded without it. On the other hand, I wrote a Modern Love essay about when my husband and I started dating, and I only told him about it once the New York Times required him to sign a form. I agree with Kyoko Mori that “anyone who marries or goes out with a writer, they should understand that they are signing up for this … I’d love to say to people, don’t worry, I’ll never write about you. But it would just not be true.”

A surprising number of writers (surprising to me) say they don’t show their manuscripts to their subjects at all before their memoir is published. Sue William Silverman, for example, explains, “I didn’t want anybody influencing what I had to say. I didn’t show it to my sister and say, Are you okay with this? If she’s not okay with it, I’m still going to write it … If she disagrees with it, then she gets to write her own book, if she wants.”

Melanie Brooks says, “I’d heard from a number of authors I interviewed that they were intentional about not sharing the finished work with their families before publication because they didn’t want anyone dictating what should or shouldn’t be in there.”

Maureen Woods was an exception. “These people did not ask to be in my story,” she says. “If they were writing a memoir, I would want to see what they wrote before it came out and have the chance to say something about what feels like an invasion of privacy.”

Your family will react.What kind of reactions will you get from your family—whether they see the memoir before or after it is published? I posed this question to an online group of memoirists and received a wide range of answers. Some told me their families had threatened to sue or cut them out of their wills. One writer said her sister refused to talk to her for a long time, but she thought the rift was caused by jealousy not injury. And sometimes people respond in surprising ways. Instead of wanting you to take them out of your book, they will complain because they are not in the spotlight more. Edwidge Danticat says, “My brothers asked why the book was all about me. I said, Because I’m the one writing it.”

Not all responses from family are negative. Sometimes the process of gathering information brings people closer. That happened with my mother and me. She is finally comfortable talking about herself. She no longer thinks her life is not important enough for people to care about it. She now knows that people are interested in women like her, women who, for much of history, have been invisible, soft-spoken and self-deprecating women eclipsed by loud and powerful men. My mother attended two of my memoir book launches. After the second one, she sat around a table with my brother’s friends and answered questions about how she coped as a twenty-something widow with three small children, after my father’s strange and mysterious death. She talked about how she managed to grow up quickly after her mother kicked her out of the house at age sixteen. She talked about how a working-class girl with few opportunities became interested in art, and how that helped her survive a traumatic childhood and marriage. I am closer to my mother than I have ever been because we have nothing left to hide from each other.

Now back to my cliff-hanger. I was at the post office, about to send off a copy of my manuscript to every family member-character in my memoir. I know I’m anxious because my FitBit shows my heartrate: over 100 beats per minute. It is the beginning of December. What could possibly go wrong? I feel as if I’m about to jump—not off a cliff but off the edge of a swimming pool. I know how to swim but I hate water rushing up my nose. I tell myself I can handle being uncomfortable. I tell myself I am allowed to write whatever I want and that I am sending these copies simply as a courtesy.

Then the week before Christmas, I receive a letter from one of my aunts detailing everything wrong with my story. The list is long. I can’t even handle reading it myself, so I ask my husband to read it to me. I feel like I should be wearing a hazmat suit—it’s that harsh. What’s more, my aunt says she has sent her letter to everyone else in my family.

I immediately call my mother and apologize. She says I didn’t do anything wrong, that she doesn’t agree with my aunt. But I have the terrible feeling that I have done something wrong, and I need to make it right. I watch the film Manchester by the Sea, in which a man accidentally burns down his house and kills his children. I feel like that man.

My brother flies in to spend the week between Christmas and New Year’s with me, and he helps me address my aunt’s grievances, page by page. We revise the manuscript together.

My aunt is finally satisfied with my revision. She doesn’t forgive me, though, and says she can’t forget what I wrote in the first version.

What would I have done differently? What would I advise you to do, based on my experience? Have one trusted reader, preferably someone who knows all the characters in real life, comb through the manuscript first, imagining what others will think. In my case, that person would have been my brother. He is the one who helped me afterwards, but it would have been so much less traumatic if I had asked him to be my first character-reader.

What if I’m not up for any of this?Maybe you are thinking, This sounds kind of complicated. I’ll just keep my family out of my story. I thought I could do that, too. But “you can’t write a family memoir without writing about people in your family,” Joan Wickersham says. “Your experience is all tangled up in theirs.”

Maybe you are even thinking, Why write my story at all? It sounds like a lot of heartache. Maybe so, but it is also true that once a memory moves from your mind to the page, it can feel like a burden lifted. To quote Joan Wickersham again, “A police sketch artist said that one of the things she liked about her job was that before meeting her, these people had to carry the memory of that face, but once they gave it to her, she hoped they could forget it a little bit.” The same can be true with memoir. Once you write about a memory, you don’t have to carry it around, trying not to lose it, anymore.

The other day someone asked me about when I introduced my then-boyfriend to my seven-year-old son. I couldn’t remember. But then I realized: I don’t have to anymore. The memory is out there in the world, in a Modern Love column, and in my memoir. I no longer have to carry it around, afraid that otherwise it might disappear.

print / ebook

print / ebookI bristle when people ask if writing my memoir was therapeutic. I am afraid they mean, Was it only therapeutic? I want to say, No, I wasn’t trying to heal, I was trying to make art. But the truth is, you can do both: create something beautiful and arrive at a deeper understanding of yourself.

I won’t lie: Writing memoir can be grueling, both in terms of hard work and emotional fallout. So allow yourself to enjoy the benefits. That’s one of the most important tips I want to share.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, check out Sharon Harrigan’s new novel, Half.

June 8, 2020

Questions to Ask Your Publisher Before You Sign the Contract

Over the weekend, you might have seen a writing-and-money topic trending on Twitter, #PublishingPaidMe, where authors started publicly sharing their advances. Such transparency is long overdue and—in this particular case—is meant to reveal stark differences between what Black and non-Black authors get paid.

Amidst these tweets, I saw a repeated call to action for Black authors: Before you agree to a deal, ask your publisher about their marketing and promotion plans for your book. Ask how they plan to support you. Ask, ask, ask. (Because their support falls short of where it needs to be, and publishers have to be pushed.)

To assist with that call to action, I’ve collected and expanded information from my past books and articles to help authors ask questions of their potential or existing publisher. I’ve tried to also include indicators that will help you notice and challenge unhelpful answers. If you have an agent, start by asking them these questions or having them assist you with this conversation.

While this is a long article, it’s still not an exhaustive list of questions, and it so far remains a general list that could be used by any author. I welcome advice and insights from BIPOC to help me improve this; moreover, I grant permission to anyone who would like to build on it, revise it, and republish it elsewhere with their additions and experiences.

As with most things I write about the business, I must offer a critical caveat: This industry can be like a dozen industries all smushed together. Small or independent publishers might have little or nothing in common with the Big Five houses in terms of marketing muscle. Their support may look very different than a corporate publisher, but it doesn’t mean that support isn’t valuable or meaningful. A small press may offer more personalized attention and enthusiasm that lasts long beyond the book launch window. They can be more nimble and also laser focused on what marketing leads to profitable sales—because they have to be, or they’ll go out of business. Respect that every publisher has unique strengths (and, certainly, weaknesses).

The responsibilities of traditional publishersTo greatly simplify matters, a traditional publisher has four overarching duties:

Producing the best-quality book, regardless of format. This includes editorial, design, packaging and production. Selling the book into accounts, such as bookstores, wholesalers, all types of retailers, and libraries—basically, any place books are sold or available. Marketing and publicizing the book to the trade, such as booksellers, librarians, and trade book review outlets (e.g., Publishers Weekly or Library Journal). Marketing and publicizing the book to readers, whether that’s through consumer marketing (email and social media, for example) or through traditional media and publicity (newspapers, magazines, TV, radio, and so on).You’ll want to ask questions regarding each of these four areas.

1. Producing the best-quality book Who will your editor be? Is it the same person acquiring or making the offer on your work, or will it be someone else? Will you be working with people who are in-house or freelancers? How are those freelancers selected? Look at the publisher’s recent cover designs. If you can’t easily view the past season or two of titles at their website, check out the publisher’s catalog at Edelweiss—free to sign up. What story do these designs tell? What audiences are being spoken to? Would you be comfortable with your cover looking like what you see represented? Compare the covers for white authors and BIPOC authors. Have a discussion with the acquiring editor if what you see concerns you. What formats does the publisher plan to release and when? This will depend on the type of publisher you’re working with—and their plans may change—but a Big Five publisher contract usually includes rights to publish in all formats, including audio. They tend to release A-list fiction titles—the ones they really get behind—in hardcover, ebook, and audio to begin, then they’ll wait 1-2 years to release the paperback. Or the publisher may release a trade paperback instead of a hardcover. For some genres, like romance, a mass-market format might also be in the mix. All of these formats get priced differently and the royalties vary for each. So figure out what’s standard or expected for your publisher. You can usually tell from the catalog of new releases—and your agent should know, too.2. Selling the book into accountsPart of the value a traditional publisher is the ability to sell your work into bricks-and-mortar bookstores, wholesalers, library distributors, and so on. Your book gets pitched, even if it’s just for seven seconds, to accounts like Barnes & Noble. Most traditional publishers still work according to seasons, meaning they have a fall list and a spring list—so there are fall sales meetings and spring sales meetings to determine what books will get placement.

Does the publisher have its own sales team? If not, do they work through a distributor (or a larger publisher) to pitch your book to accounts? Ask your agent or editor about this, or you can figure it out from visiting your publisher’s website. The sales team carries a lot of responsibility for how your book gets pitched and they’re the ones on the hook for securing orders and placement. They communicate to the accounts and can be responsible for building enthusiasm. You want to know who’s going to be making the case for your book, and if your editor has a direct line to these people. If your editor doesn’t, then who does? Can you be at the sales presentations? Can you make your case to them in person or virtually? Press for it if possible. Worst case, make a video that can be shared with sales, as Amy Stewart discusses here. What’s the planned release date? Does it make sense to you? Publishers often put their “big” books in the fall, but not always. Beach reads might release in the summer. Books that tie into New Year’s resolutions will launch in time for January publicity. Ask your agent or editor what they think about the release timing and why a particular month was chosen. Read recent book descriptions at the publisher’s website and at online retail sites. What audience is implied in the marketing copy for their titles? What does the publisher emphasize? How is the book being positioned? How does the publisher expect to position your book?Important: Your editor is largely responsible for distributing early versions of your work to the in-house sales and marketing staff to drum up enthusiasm and support. The editor will also pitch your work during a season sales meeting, and make suggestions for how the book can be best positioned in the market. Important decisions are made while you are still writing or revising the book, and you might not realize it. Stay in close touch with your editor and ask about those sales meetings and marketing plans!

Around six to twelve months before your book is released, once your book has a relatively final cover and title, the publisher’s sales process will begin. This tends to coincide with the release of the publisher’s seasonal catalogue of titles. Get a copy of this catalogue by asking your editor. Turn to the page that lists your title. How is it positioned? If it has a full-page listing near the beginning, that indicates A-list treatment and support. If it’s buried, not so much. What does the catalogue say about the publisher’s marketing plan for your book? If you’ve been communicating well with your editor or publisher, nothing you see in the catalogue will come as a surprise. (More on this below.)

By the time the sales calls are made, the publisher has already determined and budgeted for the most important marketing initiatives for each book. Advance praise will often be secured, large-scale advertising campaigns will be on the calendar, and forthcoming media commitments—such as an excerpt set to run in a magazine—may be touted as a reason to commit to a strong sales number.

3. Marketing and publicizing the book to the trade“Trade” is defined as publishing industry insiders, or: booksellers, librarians and reviewers who are typically first in line to make your book known and visible to readers. A publisher is quite unlikely to have a full marketing plan at the time of contract signing, so you may not get clear or straight answers on these issues until later in the process. But you can get a general idea of their strategy or thinking—and the size of the advance is likely to indicate their seriousness.

Will your publisher invest in advance review copies (ARCs)? Publishers often produce advance review copies of your book about four to six months prior to release, and send them out to whomever they think will most likely offer placement, reviews, or coverage. ARCS are sent as print copies through the mail and/or digitally through services like NetGalley. Ask your publisher who they expect to target with ARCs. They might focus on independent booksellers, certain types of libraries, influencers such as Bookstagrammers, book clubs, or a combination of communities, but ideally you’re looking for a plan that is specific, realistic, and tangible. Note that some small presses can’t play the ARC game anywhere near like the Big Five—it can be time consuming, expensive and frustrating. This isn’t necessarily a deal breaker; just get clarity on what they plan to do instead. Will your publisher help you meet booksellers, librarians, or others prior to the book release? Assuming there’s not a pandemic going on, publishers’ sales and marketing teams will attend bookseller and librarian conventions, and other industry-facing events, to market upcoming books. Select authors get invited to these events, too. And editors are often asked to select one or two titles they’re most excited about from each season’s list (such as the “buzz” books at BookExpo). When you sign your contract, it may be too early for the publisher say where your book is positioned in the season, and if you’ll be one of these select authors, but the quicker you can find out, the better. Will you go on tour? Publishers aren’t as gung-ho about funding tours as they used to be, but regional tours or targeted city tours still happen, especially when there’s a heavy emphasis on appealing to independent bookstores and libraries. Where will the publisher advertise? Some publishers advertise new releases in Publishers Weekly, Library Journal, Shelf Awareness, book club sites, and more. One outlet is not necessarily better than another; it depends on the sales and marketing strategy. Does the publisher plan to push for recognition—such as book awards, club selections, etc? There are all kinds of book club picks, literary awards, and special types of recognition a book can receive. Does your publisher think your title is right for such exposure? Why or why not?Publishers may attempt to secure promotional display for your book at a major retailer. Such displays are always paid for, and the retailer (not the publisher) makes the final call on what gets display space. It’s unlikely for a publisher to secure such placement until after they pitch the book to their accounts, so display confirmation may not happen until close to the release date.

4. Marketing and publicizing the book to readersSome publishers can do a tremendous job of producing a quality book, selling a book into accounts, and getting books on shelves throughout the country … but then no one shows up to buy those books. These days, it’s necessary to evaluate a publisher’s ability to reach readers directly.

Does the publisher have a publicity staff? Will you be working with a publicist? Are they in-house or freelance? Once you’re put in touch with a publicist, you’ll want to ask about their strategy. A general, mass outreach plan is rarely to your benefit, especially if it can’t be measured; a specific plan of attack (“Let’s make sure everyone who loves XYZ knows about this book”) can be measured and more effective.Will there be a pre-order campaign? A pre-order campaign by the publisher might try to drive advance buzz about the book, particularly through digital channels. Some publishers will advertise pre-orders on social media and use that information to help inform the overall marketing campaign—perhaps even tweaking the title and cover design if they believe the positioning is off. Similar to the previous: Will there be an early review or influencer buzz campaign prior to release? Publishers might invest in giving away ARCs on Goodreads, NetGalley, or over social. This is typically done in two waves: several months prior to release, then just preceding the release. This helps build visibility and reviews on Goodreads and other media outlets. (Note that Amazon doesn’t allow for customer reviews prior to the release date.)Does the publisher have an email newsletter list, social media accounts, or other places where it discusses new releases? Figure out all the assets of your publisher so you can ensure they’re promoting your book through all their owned media. Where will the publisher advertise? Warning: People inside the industry often say advertising in places like the New York Times doesn’t sell books and is done only to satisfy an author’s ego. Whatever you think about this, it is true that an ad that runs in a special-interest publication or in a niche email newsletter may be far more effective in driving sales than mass-market advertising. Much depends on the book and the overall nature of the campaign.Study recent titles from the publisher at their website or an online retailer—what’s the review activity like? Are there editorial (professional) reviews listed that indicate someone avidly reached out to the media? Follow the publicity breadcrumb trail for recent titles. You want evidence that the publisher submits the book to appropriate media outlets for coverage.Ask for the author questionnaire. Most publishers will ask you to complete an author questionnaire. This document asks about every facet of your network and platform, including names and contact information for important relationships or professional connections, information about your local and regional media, and much more. The more the publisher knows about your resources and potential networking opportunities, the more they can potentially support your book. They’ll want to build on your existing assets. After you submit this questionnaire, follow up about it. Ask what the marketers or publicist will do with the information. Ensure it gets used.It’s well known and even acknowledged by publishers that not all books are adequately or equitably marketed and promoted. Partly this is because publishers sign more books than they can sufficiently support with existing staff, plus they’re likely to throw their weight behind a handful of titles each season (the ones that received the largest advances, usually).

Promotional opportunities for books can be competitive given the limited (and sometimes shrinking) number of book review outlets and other coverage opportunities. Publishers are also guilty of not thinking creatively about how, when, and where books can be reviewed or talked about. The end result is that publishers can rely on hope alone that a book finds its audience.

It’s important to realize that, once your book releases, most of the publisher’s sales and marketing work is—in their eyes—already finished. Much of the media coverage that happens will have been seeded weeks or months earlier. If nothing happens to help the book gain sales momentum in its first three months or so, the publisher will turn its attention to the next season of books. If the book doesn’t sell in sufficient quantities in its first six months on the shelf, it will be returned and not restocked, to make way for next season’s titles.

If your launch ends up being a disappointment, and it was a hardcover release, there is still hope. It may find a new life as a paperback release and have a second shot at bestseller lists as well as editorial coverage. Or, if your book scores a major award or media attention after its release, that may give the publisher a way to re-sell or re-pitch the book to accounts, to argue for a bigger buy.

What a cookie-cutter marketing plan looks likeI’ve seen a good number of book marketing plans from publishers that are terribly generic and could be applied to nearly any title they release. Here’s a stripped down version of how they look. Notice there are no specifics—no specific people, publications, or communities mentioned. No specific retailers or libraries or reviewers mentioned. No specific bookstores mentioned. This is simply a boilerplate, a starting point, without much value to anyone in its current form.

Pre-PublicationARC mailings to sales reps and accounts, librarians, booksellers, reviewersPublisher’s catalog sent to media, libraries, booksellersDuring PublicationSecure review and feature coverage with print, online, and radioPursue targeted outreach to blogsPitch bookstore and library events in the author’s regionDigital MarketingPost on publisher’s Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accountsTie into currently trending topicsBookstoresFeatured title at publisher’s booth at ABA Winter Institute and BookExpoAwardsMailings for state awardsMailings for book industry awardsRetail placementPitch for merchandising at accountsYour turnIf you’re a published author, what did you ask your publisher about their marketing plan? What sort of answers did you receive (or not)? What do you wish you had asked your publisher?

For authors currently struggling with whether to accept an offer, I hope that your agent can adequately guide you. If you don’t have an agent, you’re welcome to reach out to me with questions using my contact page. However, I’m not an agent, and I’m not a lawyer, and sometimes the best next step is finding one to assist you. I can send suggestions if you reach out.

May 28, 2020

What I’ve Learned Writing Middle Grade Nonfiction

Photo credit: MizGingerSnaps on VisualHunt.com / CC BY

Photo credit: MizGingerSnaps on VisualHunt.com / CC BYToday’s guest post is by historian and author Tim Grove. His latest book for young readers, Star-Spangled: The Story of a Flag, a Battle, and the American Anthem, is now available.

Most people don’t “fall into” writing middle grade books with a major publisher. But I did.

I was working at a high-profile museum and had published two books—one for practitioners in my field, and another with a university press, both for adults.

But on the job, I was writing in different formats for family audiences. Several work colleagues completed a children’s book project with Abrams and the publisher was looking for another project at the museum. I was working on an exhibition that featured an airplane with an amazing story few people knew. It was an adventure story that I would have loved as a young reader. I decided to pitch it, and despite the risks involved in signing an unknown story and an unknown author, Abrams approved it.

The finished product, First Flight Around the World, received some great reviews. I had enjoyed the process so much that with the support of my boss (because writing books was not in my job description), I pitched another book that Abrams accepted.

First Flight gained some major attention as a finalist for the YALSA (Young Adult Library Services Association) Excellence in Nonfiction award. I began looking for an agent when one came to me. I signed with the Trident Media Group, and suddenly gained momentum as an author.

print / ebook

print / ebookToday, my third middle grade nonfiction, Star-Spangled: The Story of a Flag, a Battle, and the American Anthem, has recently been published and my fourth will launch in 2021. Many librarians and teachers tell me there is a great need for history nonfiction for students. My goal as a trained historian is to make history accessible to readers and to help them understand the process—how historians look at source materials and draw conclusions. It’s the detective aspect of the work that gets lost in history class. And if I can change perceptions along the way, even better. Changing perceptions of history is not always easy, but book by book, I hope to do my part to try.

Here are some things I’ve learned about traditional publishing.

Topic relevance. Why should the reader care? You must be able to show an editor that your topic will be of interest to a wide audience. Although my book Star-Spangled is set in and around Baltimore, most Americans know the national anthem, so a young reader in Idaho will already have a personal connection. Narrative is key. The more you can add elements of fiction the better: narrative arc, character development, plot, tension, etc. While demand exists for survey-type books or how-to books, narrative has a better chance to capture an editor’s attention. Author platform. As with any nonfiction, you must show an editor why you are the person to write this book. What gives you authority? While many good writers can do research and can write a good history book, I bring a greater authenticity than some because I am a trained historian with years working in the history field. Timing is crucial. You must trust the editors to know what will sell and when. For history books, it’s helpful to be aware of trends and anniversaries in history. The 250th anniversary of the USA is 2026, for example—and editors will be looking for books that tie into this milestone. Back matter. The best middle grade nonfiction books include end notes, a bibliography, a glossary, and an author’s note about his/her process. This adds extra authority. Visual images. If you’re writing history, try to include images of your sources. This helps readers see where the information comes from: letters, historic maps, paintings. I am fortunate that my editor encourages this. Often in history books, maps are crucial visuals that help a spatial learner see how things fit together. Quotations. Use original quotations when possible. I try to infuse my writing with the best quotations I can find from my research. In nonfiction, you can’t put words into your characters’ mouths, so you must choose characters that have spoken in the form of journals, letters, diaries or official military or government papers. Sometimes that writing is archaic and stilted, with difficult words for young readers. You may decide to only use part of it, or use brackets for clarification, but giving readers a taste of another time is important. Subject matter. Choose your subject with great care. As with any book project, you must live with it for a long time. The topic must sustain your interest on a personal level. Your passion will come through. And the source materials must provide sufficient variety of perspective and insight into character that allow you to spin an interesting story.Sometimes it feels like every writer I meet wants to write fiction, but librarians and teachers need more nonfiction for young readers. Several large publishers have recently launched new imprints for young readers of nonfiction.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, check out Tim’s latest book Star-Spangled: The Story of a Flag, a Battle, and the American Anthem, published by Abrams Books for Young Readers.

May 27, 2020

On Multi-Genre Publishing: Q&A with Hybrid Author Catherine Stine

In this interview, multi-genre author Catherine Stine shares her love of suspense, discusses writing “what you know” and writing to the trends (or not), and talks about her experiences with traditional and self-publishing, from both creative- and business-minded perspectives.

Catherine Stine (@crossoverwriter) is a USA Today bestselling author of historical fantasy, paranormal romance, sci-fi thrillers, and young adult fiction. Witch of the Wild Beasts won a second prize spot in the 2019 Valley Forge RWA Sheila Contest. Other novels have earned Indie Notable awards and New York Public Library Best Books for Teens.

She lives in Manhattan, grew up in Philadelphia, and is known to roam the Catskills. Before writing novels, she was a painter and children’s fabric designer. She’s a visual author when it comes to scenes, and she sees writing as painting with words. She loves edgy thrills, perhaps because her dad read Edgar Allen Poe tales to her as a child. Catherine loves spending time with her beagle Benny, writing about supernatural creatures, tending the garden on her deck, traveling, and meeting readers at book fests.

On WritingKRISTEN TSETSI: What draws you to wanting to write suspense, and what’s the most fun you have when writing a highly suspenseful scene?

CATHERINE STINE: I love a page-turner, and I get a thrill out of crafting twists and turns and ratcheting up the tension to a fever pitch. It’s a fun challenge, as it’s not that easy to create scenes that readers can’t guess at, that keep them disturbed, thoroughly surprised, shocked. I consider it a success if they are still thinking about the theme or the characters a few days later, a week later, what with all of the diversions and media we have at our fingertips.

Probably my two most proud suspenseful creations are the ending of Pictures of Dorianna that no one’s ever guessed at correctly (unless they cheated and skipped to the end!), and what happens to Evalina’s second nasty employer in Witch of the Wild Beasts! No spoilers here, you’ll have to read the tales.

This love for suspense started with my first novel, though I was unaware of it. In Refugees, Johar runs from his home in Afghanistan to seek shelter for himself and his little niece while, on the other side of the world, Dawn flees from a cold, unloving foster home and arrives in NYC right before 9/11.

In the Fireseed series, the world in 2089 is falling apart from excessive heat and lack of food, and there is eco-terrorism, even a murder.

At the moment, I am developing a romantic suspense series set in contemporary Los Angeles that I’m having wicked fun with. I’m clearer on what I love to do, and that has made all the difference. The only downside is that to plot suspense, one must piece together a very intricate puzzle even before most of the writing occurs. As in a mystery, it is mostly plotted backwards.

You say in an Authorturf interview, “Write about things you are passionate about, not to the trends.” Anyone who’s seen the success of the many zombie efforts—all of the money made chasing that trend—might ask, if trends are so trendy, why not write to them?

Yes, I did say that… back in about 2012, when I was climbing out of my traditionally published platform into my first breakout indie moment. LOL.

The first part of my line from Authorturf still rings very true for me: “Write from a raw place, just beyond what you know for sure yet intuit strongly. Enter into a place of wonder and horror, love and brutal honesty.”

In traditional publishing it makes sense not to chase trends because what is popular at the time of writing will not necessarily be popular two years hence. This is how long it takes a traditionally published novel to come to market.

In the indie market, where one can publish very close to the time the novel is completed, authors do write to trend more often.

Interestingly, the trends that come and go in the traditional market are often at odds with the indie market. I remember a few years back when paranormal went way out of favor in the traditional market, while it was still quite lucrative in the indie market. I tell my writing students not to be a slave to trends, while at the same time, to keep an eye on the market. So, I would say, try to do both.

But the “passion” part factors in because if you have no personal energy for a trend (zombies, shifters, Gone Girl clones, fairytale twists), no matter how popular it is in the market, your work will fall flat. If you are bored with it, your readers will be.

I find that what an author is truly fixated on becomes exciting fiction. For me? Cults, shady beach towns, bizarre methods of murder, reluctant heroes, witches, tortured nature, animals and hybrid critters are some.

Whatever it is for you, embrace it and be fearless in presenting it!

You’ve said you don’t necessarily like the advice, “Write what you know,” and think it should instead be, “Write some of what you know, and some of what you’re curious about.” Are there certain things you think you, or any writer, would be better off not writing about without having first experienced them?

Joan Didion says in her landmark essay “Why I Write” she writes to find out what she’s thinking, looking at, and what it all means. To write “What I want and what I fear.” To answer questions that “shimmer” in her mind.

I so get that. Characters filter in and they demand attention sometimes years before I build them on a page. Part of this process is rational and mathematical, the other part pure poetry, magic and obsession. In this regard, an author cannot say in all honesty that they write novels using only experiences and elements they are thoroughly familiar with.

Why bother if you aren’t stretching, learning, discovering. Think of it as method acting, where one inhabits a strange, new character completely out of their comfort zone. Great actors do this all of the time.

As an author of historical fiction, I adore research. I learn so much in the process. I grew up in Philadelphia and figured I knew my city in and out, but in the process of researching Witch of the Wild Beasts I learned tons about its darker history, about the wacky medical trends of the 1850s, about the roving, racist gangs and more.

The one thing that I would not do again is write a novel located in a part of the world I have not personally visited. When writing Refugees, I could not visit Afghanistan because a war was being waged there. Instead, I did exhaustive research and interviewed people who had grown up there and fled.

It worked out, but it’s very hard and not advisable. I also feel that when a Caucasian author writes a person of color as a main character it can be very tricky. I got around this once by writing my heroine Joss as biracial. But as bestselling romance authors Courtney Milan and La Quette insist when writing people of color, one must have a sensitivity reader and be up on the newest set of guidelines.

Aside from Paris (or, if you’re a Hemingway idol, Cuba), nothing inspires authors’ fantasies like living and writing in New York City. A Carrie Bradshaw apartment, computer set up at a window overlooking quirky neighborhood life…material for years. But is that true? Is New York City a major source of inspiration for you? Can you imagine writing the same way in a different place—like a suburb of Connecticut? This isn’t a trick question or a trap.

Haha, you crack me up. Yes, New York City has been a source of inspiration. I grew up in Philly, but I’ve lived in Manhattan for years, though I also live in the Catskills, which is a great counterpoint and provides inspiration for rural storylines. Hey, I had two Vietnamese potbellied pigs!

But yes, I love the city’s international feel, its diversity of people. It has a fast pulse and a driving soundtrack—classical, jazz, hip-hop, fusion. It’s really a myriad of tightly woven neighborhoods. I wrote a romance series about an artist set in NYC (in the process of being rebranded). I wrote a YA set in the East Village. Part of my first witch book, Witch of the Cards, was set in depression-era Manhattan where a shantytown was built in Central Park!

Oddly enough, it’s the sketchy beach towns nearby that hook me the most. Pictures of Dorianna was set partly in Coney Island, Witch of the Cards in 1930s Asbury Park, NJ. Even my futuristic thriller Ruby’s Fire was set partly in a city called Vegas-by-the-Sea. I love me a creepy beach town. LOL.

But seriously, NYC has endured so much—9/11, the hurricane Sandy blackout, being an epicenter of the COVID-19 virus. It makes us tough, caring, soulful, full of heart. And that is inspiring.

Author Sue Grafton angered many self-published authors when she said in 2012 that self-published authors are “too lazy to do the hard work.” There was, and surely still is, a perception among many that those who self-publish get to skip the process of editing and revising until they meet the standards we expect when reading something (something good, that is) that is traditionally published.

As someone who publishes both traditionally and independently, what can you share about the editing and revising process for each? Are you more careful with one than you are with the other?

Sue Grafton didn’t live to see the market as it is today, but if she had, I’m sure she would rethink her statement.

Many authors are now proudly hybrid, and those who started as indies do not always accept contract offers from trad markets. Some indie authors make huge pots of money. Others who started with big publishers have diversified, depending on their projects.

All of the indie authors I know go through multiple drafts and hire top-drawer editors before their manuscripts see the light of day. Many editors who worked full time in the traditional publishing world now happily work freelance for indie authors.

That said, there are no doubt some indie authors who don’t follow a professional standard, but these days they don’t get far. And over the years, I’ve read plenty of horrid trad fiction.

What contributed to publishing changes? The economic crash of 2008 was a factor in transforming the market. My agent was sending around my Fireseed series at that time, and as soon as we would put together a sub list, 90 percent of the editors at big houses were laid off. It was crazy! Houses were only purchasing sure-shot blockbusters, and very few even of those.

Another factor was the explosion of ebooks. A larger and larger percentage of folks read on digital tablets, and so many brick and mortar bookstores have folded. It’s encouraging, though, to see indie bookstores emerging, and people still love to buy paperbacks. I love hand selling at book conferences because I get to chat with readers!

I have published with big houses such as Delacorte and American Girl/Pleasant Company, smaller houses such as Evernight Teen and Inkspell, and of course with my own line, Konjur Road Press. I have also gotten my rights reverted when I could do better marketing on my own.

The control I had with my first indie project (Fireseed One and Ruby’s Fire in my Fireseed series) spoiled me. I learned so much about putting together my publishing team – connecting with great editors, cover artists, personal assistants and advertising outlets. Now I can format a book with Vellum, so I cut out that middleman step, too.

I like being involved in the book’s design and hiring just the right cover artist, as I came from the art world. I know Photoshop, so I can put together teaser promos. The advertising and social media game is always changing, so it’s a constant educational challenge. But one I’m here for.

The only downside is I miss the monster distribution machine of a huge publisher. But the indie community has many creative workarounds and we all share new avenues and tactics. I would still sign a trad deal, with a close look at the contract, the publisher, and their marketing ideas.