Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 79

September 2, 2020

4 Lessons from 4 Years of Self-Publishing

Today’s guest post is by author Deanna Cabinian (@DeannaCabinian).

It’s been four years since my young adult novel One Night was released. Time has flown by, and during the past 1,460 days I’ve learned several things about myself, my writing, and indie publishing. But four lessons stand out.

1. There isn’t a magic bullet for selling books.There isn’t any one thing that sells books; it’s a lot of things. I’ve tried every promotion avenue I can think of, including whatever’s hot at the moment: Amazon ads, free book promotions, BookBub (my book was featured in their international deals newsletter), NetGalley, Goodreads giveaways (before they started charging), local author fairs.

That’s in addition to my email newsletter, blogging, refining book descriptions and keywords every six months, and placing guest articles when I can. You name it, I’ve tried it in some form or another. Someone asked me recently, Have you tried Instagram? I just smiled and nodded.

2. For every ten doors that slam in your face, one or two crack open a tiny bit.When I started promoting my book in 2016, I was frustrated by the number of nos I received. My hometown library, a modest operation, couldn’t be sold on letting me do an event. I offered to host a writing workshop, a Q&A, a reading. Nope, nope, and nope. The teen librarian offered to place some bookmarks at the circulation desk, however.

Despite the resistance, I’ve had a few surprising wins along the way. I’ve been fortunate enough to be featured on this site and several others. I got to speak to over 300 students at my high school’s writing festival (I don’t think many books were sold as a result, but it was nice to get paid a speaking fee). And there have been many kind bloggers willing to give my book a chance even though I don’t have a publisher.

3. I still love the writing part the most.I’ve made a few good connections from pitching my work, and I enjoy having creative control, but it has been exhausting because my full-time job requires the bulk of my mental energy. I want to save what’s left of my head space for writing, not worrying about how to get my books into the hands of readers. I want a traditional publishing contract, which includes marketing and production support and wider distribution. I’ve discovered I would very much like to have a publisher sell books for me. Granted, a lot of marketing still falls to the author, but having publisher support is still an advantage. I am getting closer to that goal as I’m now represented by an agent, but our agreement is for other projects, not One Night.

4. I have no regrets.Someone asked me recently if I thought self-publishing was a good idea. She said her neighbor’s daughter was interested in putting out a book and did I have any advice for them? I told her it is much harder than it appears. Does she want to hold her work in her hands? Or does she want to use this as a gateway to New York publishers? Does she consider herself a salesperson? It’s what I would ask anyone trying to embark on this path. I emailed her a dozen articles to review.

Despite the challenges, I feel proud to have my book out there. My audience is not huge, but it’s passionate. I’m grateful for every reader who contacts me and hope they’ll follow me throughout my career.

What have you learned from your publishing journey? I would love to hear about it in the comments.

August 24, 2020

How to Find Publishers

Note from Jane: If you’d like guidance on researching either traditional book publishers or literary agents, I’m offering a class on Sept. 9, Research Agents and Publishers Like a Pro.

The following post was first published in 2011 and is regularly updated to include new resources.

If you have a book idea or a manuscript, one of your first questions is probably:

How do I find a publisher?

Or, if you’re more advanced in your knowledge of book publishing, you may ask:

How do I find a literary agent?

The good news: there’s no shortage of resources for researching publishers and agents. The bad news: you can easily spend hours going down the rabbit hole of available information.

For years (since 1920), the most comprehensive resource in the United States was the annual Writer’s Market directory. It used to be accessible and searchable online via paid subscription, but no more. And unfortunately, the future of the print edition is unclear. The 2020 guide may be the last, and it’s now at least one year out of date.

Going forward, writers will have to rely on other guides, primarily those online. Some of the sites I mention below offer useful features such as submission trackers, community message boards, and stats generated by users—which can be just as useful as the listings themselves.

Here’s a summary of the most well-known and popular places to find publishers and agents. If I’m missing an important resource, contact me.

Where to Find PublishersBe aware that most New York book publishers do not accept unagented submissions, so sometimes “searching for a publisher” really means finding an agent (see next list).

Jeff Herman’s guide. This is a well-established print-only competitor to Writer’s Market, assembled by a literary agent and updated every couple years.Duotrope ($). You’ll find thousands of listings in this online database, with an emphasis on literary journals, magazines, and online publications, many of which don’t pay. (E.g., they have more than 2,000 listings for markets that accept flash fiction, but fewer markets for full-length novels.) But they do include a sizable number of agents, publishers, contests, and anthologies.QueryTracker. Free to start, with premium ($) levels—but more agent listings than publisher listings.Manuscript Wish List. Editors and agents often post on social media what kind of books they’re actively seeking. This site aggregates those mentions. (However, this site is not endorsed by the agent who started Manuscript Wish List; the official site is here.)Submission Grindr. Free, focused on science fiction & fantasy.Ralan. Free, focused on science fiction & fantasy.Poets & Writers. Free database of small presses that are best for literary novelists, poets, short story writers, and so on. Use with caution; many of the listings are out of date.New Pages. This is a curated list of markets popular with creative writing programs and instructors; it’s a good place to go if you’re publishing short stories, poems, and essays.Where to Find AgentsMany of the same resources that offer publisher listings also list agents. But there are a couple of resources that are unique and irreplaceable when conducting an agent search.

PublishersMarketplace. Pricey ($25/month), but if you search the deals database at this website, you can study what books agents have sold going back to 2001, by category and keyword.AAR Online. This is the official membership organization for literary agents. Not all agents are member of AAR, but it’s not a bad place to check if you want some reassurance on the professionalism of your agent.Duotrope ($). See above.Manuscript Wish List. See above.Jeff Herman’s guide. See above.QueryTracker. See above.Other Helpful ListingsThe Big, Big List of Indie Publishers and Small Presses (September 2019)Literistic: excellent resource for contestsThe Christian Writer’s Market GuideFor UK writers: Writers’ & Artists’ YearbookAustralian Writer’s MarketplaceFor more informationStart Here: How to Get PublishedHow to Find a Literary AgentAugust 19, 2020

What Your First 50 Pages Reveals

Today’s post is by regular contributor Susan DeFreitas (@manzanitafire), an award-winning author, editor, and book coach. She offers a first 50-page review on works in progress for novelists seeking direction on their next step toward publishing.

Is your manuscript ready to pitch, or does it still need work? It can be a maddening question to answer. Even for seasoned authors, the question of when a manuscript is ready to pitch can be a tough call.

Leonardo da Vinci is credited as saying, “A work of art is never done, only abandoned,” and it’s easy to feel like there’s always something else you can do, some new element you can add to make your manuscript stronger.

Of course, that’s usually true. But if you’re ever going to write another book, there comes a point where you’re going to have to take a deep breath, cross your fingers, and hit submit.

So: How do you know when that time has come?

The most effective process I’ve found for determining whether a manuscript is ready to pitch is to look at its opening the way a publishing pro would. This means first reading the query letter and synopsis and then turning a critical eye to the first fifty pages.

First, synopses tend to reveal story weaknessesQueries are notoriously hard to write, but synopses might just be harder: How could anyone possibly encapsulate the epic sweep of their novel in the course of just one single-spaced page? Even so, learning how to write a synopsis is an essential skill, not just for pitching, but for getting a sense of the overall sweep of your story.

When I work with clients to determine whether they’re ready to pitch, I look first at that synopsis, because when it doesn’t quite make sense, that’s a good indication that there are issues with the plot and/or character arc.

For instance, the synopsis may indicate that there’s no clear through line with this story, no central source of conflict that escalates. It may indicate that the different storylines involved don’t clearly connect—or that the story has no real climax, a point where the different themes and sources of conflict in the story come to a dramatic turning point, a moment of truth, a transformation.

But let’s say all of that is there in the synopsis. That, plus a compelling query letter means the pitch for this book may well get the attention of an agent or editor—which means the next step is to dig into the first fifty pages of the manuscript.

What agents and editors look for in the first pagesFirst, there are the basics: Is it clear whose head we’re in within the first few paragraphs? Is there a sense that there’s something real at stake in this story, that it matters? Is the voice compelling, the prose clear? If the answer is yes on all accounts, I look for more complex things.

Exposition and backstoryIs there enough exposition for the reader to make sense of what’s happening in the story, and to understand where the protagonist is coming from? There are many writers who skimp on providing information about both the world of the story and the protagonist’s backstory, thinking that doing so makes their story sound more sophisticated—and generally speaking, it’s true: less is more. But if you withhold too much of this information for too long, you won’t be able to let your reader into the story and get them hooked.

The promiseAnother thing I look for is “the promise of the premise.” Maybe the premise, as laid out in the synopsis and query—to give a somewhat ridiculous example—is something like “boy meets unicorn, boy loses unicorn, boy gets girl instead” (though come to think of it, that might be a book I’d like to read…). If the unicorn doesn’t appear until page 40, I know this novel isn’t starting in the right place. It’s not delivering on the promise of the premise until too late.

PacingThis touches on another key issue, pacing. Because no matter how big and sprawling a story may be, if I don’t see the inciting incident and at least one more major plot development within the first 50 pages, I know that the pacing is off.

In fact, when a writer sends me the first 50 pages of a manuscript that really is ready to pitch—or close to it—there’s almost always some compelling plot development that has just occurred by page 50, usually without any planning or forethought on the author’s part. That shows me that the author has an intuitive command of the art of pacing—and that an agent or editor is likely to request the full manuscript.

Narrative tensionFinally, a big thing I look for within the first 50 pages is narrative tension. That tension may arrive from a source of conflict—whether that’s a falling out between two longtime friends or World War III in the making—or it may arise from questions the story has raised.

Who killed the jogger on that early morning run we glimpsed in the prologue?

Or: Who will be guilty of the infidelity we know is coming in this marriage?

Or: Will this troubled teen drift further into juvenile delinquency, or will her relationship with her drama teacher help her turn her life around?

Narrative tension is critical in both novels and memoirs, as it’s the fuel that keeps the fires of story burning—which is another way of saying that it’s what keeps the reader turning the pages, in order to find out what happens next. And at the end of a 50-page sample, it’s a big part of what will compel an agent or editor to request the full.

Parting advicePrepare your query letter and synopsis, then put both them and your manuscript aside for a few days, or even a few weeks. Then go back and read your query and synopsis as if you yourself were a publishing pro, and turn a critical eye to your first 50 pages.

Does this opening sound like the opening of the book described in your pitch materials? Does it have a compelling voice, the right pacing, and enough fuel to keep the fires of story burning, all the way to page 50—and beyond?

If so, you’re probably ready to pitch.

August 11, 2020

Building Your Career-Long Marketing Foundation

Note from Jane: On Wednesday, Aug. 12, I’m teaching an online class, Effective Book Marketing for Every Author.

Traditionally published authors everywhere tend to experience the same disappointment when working with their publisher: lack of marketing and publicity support.

Sometimes this is more perceived than real. Publishers tend to do a poor job of letting authors know about all the things they do to market and promote books, especially within industry channels that the author might not see visible evidence of.

But whatever your experience—and however you decide to publish—it’s unwise to depend on a publisher, publicist, or any third party to build your career, or be responsible for growing your readership. Publishers will be focused on the short-term, or on their immediate return on investment. You, the author, have to take care of the long-term career building. While you may delegate tasks or hire help, only an author can truly take ownership of their career and carry out the vision for it. It will also largely fall on your shoulders to execute marketing activities that don’t have immediate payoff but are important for future success and sales.

First things first: Career authors need a websiteThe first and most important step in your marketing journey is establishing your author website—a website that serves as a hub and information clearinghouse for everything you publish. Once upon a time (I hope this is no longer the case), publishers advised authors that they were better off creating and maintaining a Facebook page rather than a website. But it’s no replacement for an author website.

Your website is the number one calling card for a successful digital-age author. Whatever type of marketing strategy you pursue, it will be more effective with a website in place. That’s not to say that every author should put the same amount of time and energy into it—every author career is different—but there is no reason that any published author should say “no” to a website given how much book discovery now happens online. (However, having a website does not mean you have to blog. If you’re interested in blogging, I have 101 advice on starting.)

More important than a blog: Have an email newsletter signup on your website. It allows you to communicate reliably and directly with your audience from one book to the next. While it’s less than ideal to send an email newsletter only when you have a new book coming out, at the very least you’ll want it for that purpose. Learn more about email newsletters for authors.

Social media: pick at least one place where you can sustainably and consistently contributeMost new authors, upon securing a book contract, are advised they need to establish a Twitter account, a Facebook page, any number of social media profiles. Why? To market their book, of course.

This presents an immediate dilemma: If you’re not already active on these channels, of your own interest and volition, you now have the mindset of using these tools to “market”—and more importantly, you may have no idea what that means beyond telling people to like your page or follow you.

The other problem is that social media, while not going away, is constantly in flux. Its use is also highly dependent on the type of work you write and publish, your own personality and comfort level, and where your readers can be found.

If you’re in it for the “right” reasons, there are three benefits of using social media: (1) Building relationships in the writing and publishing community, (2) encouraging word of mouth about you and your work, and (3) nurturing reader relationships. Relationship building is the kind of activity that’s largely unquantifiable, and it’s a long-term, organic process. It would be counterproductive in many cases to measure sales from it, especially if you’re new to it or not well known.

For authors who have a limited social media presence, but soon realize they need to do something to support their book, there is a work around: Get your friends and influencers who already have relationships and trust in place to help spread the word for you on social media.

That brings us to perhaps the most important principle for building a decent marketing plan. A strong campaign tends to build on existing relationships and networks—not aspirational ones.

Relationships quickly become key for meaningful book marketingFor every book launch, brainstorm a list of all the meaningful relationships you have—people or organizations/businesses you can count on to read your emails or respond to your calls. Include people who would definitely want to be alerted to your new work, including peers and colleagues; people or organizations/businesses who have significant reach or influence with your target readership (say, a blogger or an established publication); and your existing and devoted readers/fans who may be willing to spread the word about your new work to their friends and connections.

Now: What marketing ideas or opportunities present themselves when you look at that list? How could you use the assets you have today to build an actionable marketing plan? Rather than try to obtain Oprah’s phone number, look at the phone numbers you do have. It’s okay to be aspirational or have stretch goals—but don’t rely on them.

As far as those aspirations: Do brainstorm a list of the influencers, gatekeepers or bigger names who could help spread the word (but that don’t yet fall into the “established relationship” column). For example, if you write romance, then popular romance review blogs would act as a gatekeeper to your readership. Do those blogs accept guest posts? Can you contribute to their community in some way? Look for tangible and realistic ways to work beyond your existing network.

Many times, when an author’s marketing efforts fail, it’s because they tried to go it alone. Relationships can be critical. When you see a successful author, what you see may only be the visible aspects of their presence or platform. What you can’t see are all of the relationships and conversations that go on behind the scenes that contribute to a more amplified reach (like on social media!). Just because you can’t see it doesn’t mean it’s not there. Virtually no successful author has been able to spread that precious word of mouth all by themselves.

Note from Jane: On Wednesday, Aug. 12, I’m teaching an online class, Effective Book Marketing for Every Author.

August 10, 2020

Are Editors Responding to Submissions During Coronavirus?

Photo credit: Mykl Roventine on Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC-SA

Photo credit: Mykl Roventine on Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC-SATodays guest post is by author Denise Massar (@denisemassar).

Since the coronavirus has upended the professional and social practices we all used to take for granted, I’ve seen a lot of writing-community chatter on Twitter wondering:

Should I query during coronavirus?

Should I go on submission?

Are editors even responding?

And I can tell you from someone currently on submission: Yes! To all of it!

It took me three and a half years to write my memoir, Matched, the story of my obsessive search for a baby in the ultra-competitive world of domestic adoption, and how my son’s adoption served as the catalyst for finding the woman who’d given birth to me. It took me nine months of querying to get an agent. From there, it took another four months to get my proposal where it needed to be, which mostly consisted of beefing-up my platform (more on that later).

Finally, everything was exactly where we wanted it; my agent—the fabulous Jacqueline Flynn of Joelle Delbourgo Associates—was ready to send my book on submission the third week of March. The same week schools shut down, and shortly thereafter, the country. It was…not ideal.

Jacquie and I talked strategy.

“Are editors still working?” I asked.

“Don’t know yet,” she said. “Maybe not. Or maybe because they’re working from home, they’ll have fewer meetings, and actually have more time to read. Or editors with kids might not have time to read at all.”

“Mmmm…” I said, the accuracy of her statement stinging as my six-year-old chatted non-stop in my other ear about the latest FGTeeV video he’d watched on YouTube.

I imagined my dream editor—a middle-aged mom with a sharp mind and an indelicate sense of humor—with her feet kicked over the arm of her favorite chair, reading my proposal. I hoped she had teenagers who could mostly fend for themselves.

“We could wait until this is all over, but who knows how long that’ll be?” I said. “I don’t know.”

“Me either,” Jacquie said. “But, ultimately, it’s your call.”

One side of my brain was screaming, Go for it! As a hopeful author, “going on submission,” was the dream—the moment I’d been working toward. Would my voice, my story, speak to a publisher strongly enough to snag a book deal? If an agent had connected with my writing, it wasn’t such a stretch to think that an editor might, too, was it?

But another voice, a quieter one, said that waiting was the safer move. If Matched went on submission and failed to sell—not because of my writing, but because the world was on fire and editors had stopped acquiring anything—I would’ve still blown my shot. But that was fear talking. The manuscript on my desktop could still be the next Wild; a manuscript on submission was going to receive criticism and rejection. A Michelle Obama quote I’d seen on Instagram had stuck with me and nudged me forward: “Don’t ever make decisions based on fear. Make decisions based on hope and possibility. Make decisions based on what should happen, not what shouldn’t.”

“Let’s send it,” I told Jacquie.

She sent my proposal to the first group of editors. Responses trickled in. It was hard for Jacquie to follow-up with editors via phone because they weren’t in their offices. But then, in April, publishers seemed to adjust to their new normal, and responses started rolling in.

And they were big, juicy, personal responses! As a hopeful author, I found myself encouraged by the rejection letters—they held thoughtful feedback on my book from big-name editors at big-name houses, people I followed on Twitter:

“Denise Massar is a really good writer! I have no doubt that there is an audience for Matched, but I don’t find myself excited enough about the subject to make an offer.”

“I have finally had a chance to read Denise Massar’s very well done proposal for Matched. Denise seems wonderful—thoughtful, smart, writes with an unflinching eye but a lot of compassion. But I’m afraid I just don’t have a vision for how to publish this book in a big way. It feels rather journalistic to me.”

“I admire Denise Massar’s frank and punchy tone, and the holistic lens she brings to adoption. In the end, though, I just worry this isn’t a fresh enough look at the issue to break through in the market. So, sadly, this is a pass for me, but I appreciate the chance to read all the same.”

“Thanks for sending along Matched. I like the book a lot but I couldn’t get enough enthusiasm from my colleagues.”

“At this point, I’m going to pass on all rights, but should you find a print publisher and are able to retain audio rights, please circle back! I’d be interested in making an audio offer.”

(Okay, I’ll admit, that last rejection above was brutal. She was an editor I would’ve done anything to work with and she’d gone to bat for me!)

On a Thursday, I received this rejection: “I’m afraid this leans a little too commercial for me.” And Friday, this one: “…just didn’t have that commercial pull we look for in memoir.”

As crazy-making as it sounds, the contradictory comments about Matched served as a reminder that writing is subjective, every editor has different tastes, and to keep going.

If you’re still wondering if sending your book on submission in the middle of a pandemic is a good idea, consider this: Doing so allows you to shift your energy—full time—from manuscript and proposal (always one last tweak, right?) to platform. Platform is a bigger deal than most authors realize, and ideally you’ve been building your platform all along. It’s an important factor in an author’s appeal to a publisher because an active online network equals built-in sales of your book. If a publisher is enticed by your proposal, they’re going to click around your website or social media to see:

How many sales can the publisher assume before they spend money marketing your book?Is your website, Facebook, Twitter, Goodreads, Instagram (etc) presence fresh, or was your last blog post in November 2019? (I think my agent’s exact words were, “Perhaps this is more of…an article than a blog?”)What articles have you published? What podcasts have you been on?What people or organizations or sites are you partnered with or connected to?Editor responses during the coronavirus have been steady, generous, and thoughtful. If you’re nearing the querying or submission stage, I encourage you to move full-steam ahead. Make your decision based on hope and possibility—your wildest dreams just might come true.

August 4, 2020

The Joy of the Work: Q&A with Author Caroline Leavitt

In this interview, author Caroline Leavitt discusses the unique challenges of embarking on a book tour during a pandemic, her indefatigable and unapologetic enthusiasm for writing and publishing after all these years, the importance of writers helping writers, the writers who helped her when she was an emerging author, and more.

Caroline Leavitt is the New York Times Bestselling author of twelve novels, including Pictures of You, Is This Tomorrow, and Cruel Beautiful World, some of which were on the Best of the Year lists, as well as Indie Next Picks. A New York Foundation of the Arts Fellow in Fiction, and a Sundance Screenwriters Lab finalist in pilots and feature, she is also a book critic for People Magazine and AARP. Her work has appeared in The Daily Beast, Salon, New York Magazine, Modern Love in the New York Times, Real Simple, and more. She teaches novel writing online at Stanford and UCLA Writers Program Extension and works with private clients. To learn more, visit her website.

KRISTEN TSETSI: Your protagonist in With or Without You, Stella, goes into a coma. You recently published a piece in The Daily Beast, “I Was in a Coma and No One Will Tell Me What Happened,” explaining that you wrote Stella’s experience, her consciousness during, and her memory of, her coma, because you had been in a coma, but one that you had no memory of, and “I wanted someone, anyone, to experience what I had and remember it, so I could process it.”

What you say you do remember, such as the terror you would experience when you saw things that turned out to have connections to your hospital stay, sounds absolutely horrifying. What did it take for you to go back there—how did you do it, what was your process? And how did it feel?

CAROLINE LEAVITT: When I first told my agent I was going to write about coma, she said, “What, again?” because I had written an earlier novel, Coming Back to Me, about a woman in a coma who remembers nothing. But it hadn’t healed me, because there was nothing for me to grab onto and process. I still had these terrible triggers that would flare up. Certain smells or colors reminded me of something in the hospital I couldn’t remember and I felt unnerved. I still hate going to sleep at night because I’m so terrified about what might happen.

The funny thing is that originally I had not planned to go so deep. I was going to write about a woman who has a near-death experience and wakes up with a healing ability, but I couldn’t grab onto it. Something wasn’t working.

Then I was thinking about this longtime couple my husband and I knew who were the perfect couple until, after 17 years, the guy suddenly had an abrupt personality change. He became a weightlifter, dragging trucks by ropes in his teeth! His body and his mind changed, and they divorced.

So I was thinking about that, and I started to research, and BOOM, there was coma popping up. And then after all this time, my husband was talking about the pandemic and he said, “I haven’t felt this kind of dread since you were sick in the hospital,” and when he said that, it surprised me, because he had never wanted to talk about it.

I began to think more and more about my coma, about how it still unnerved me. Then I thought, well, if writing about a woman who couldn’t remember anything about her coma hadn’t helped, what if I wrote about a woman who remembered everything? What if I were able to process my coma that way?

I wrote and wrote and wrote and it was disturbing and terrible and then I’d remind myself Stella wasn’t me. Stella was able to not only remember and process everything, she was able to heal for the better. And that was my lifeline.

A piece of writing advice I love and often use comes from you. If there’s a stuck point while writing, you said, have a character say or do something completely unexpected or take the story somewhere unexpected. (Using that advice added an entirely new dimension to a relationship I was writing, which in turn generated a larger idea for their story as a whole, so I’m ever-grateful to you.)

Did you have an opportunity to use that trick/technique while writing With or Without You?

I’m so happy that was helpful!

Writing to me is all about shaking things up when you feel stuck. I’ve printed out my manuscript in another font or another color to trick my mind. I’ve also read it out loud. But I always wonder, when I get stuck, how to push my characters to their limits.

I had to figure out Stella’s personality change and her coma talent, and I kept researching and nothing seemed right. First I thought, maybe she’s suddenly a great athlete, but it didn’t feel like a good choice, because I kept thinking, well, so what? Then I thought she would be a writer, and then while she was just drawing circles, because I had no idea what she would even write about, I started to remember that R. Crumb, the famous underground comic, had a brother who drew in circles, and so I gave that to Stella. Then suddenly everything opened up and she was not only drawing people beautifully, but she could see their inner lives. It was something I just never expected.

“Writing is lonely work” is a popular writer’s lament. Do you think writing is lonely work?

I love this question. Because the answer for me is, oh no, never! I actually don’t think it is at all!

I’m surrounded by people/characters I love in my work, and living in their world is amazing. I tend to get into a kind of zone, so that if my husband says, “Caroline, the house is on fire,” I won’t hear him or see him.

I’m just in that other world.

I love anything quantum physics, and who knows if when I am in the zone of writing, it really is another world I am inhabiting? If light can be both a wave and a particle at the same time, which is supposed to be impossible, maybe this can be true, too, and isn’t that incredible?

My watercooler is social media, so I am always grabbing chats with friends or other writers every few hours, plus my husband works at home. Plus again, I’m just so grateful that I get to do something I love so much. How amazing is that? I never take that for granted.

A lot of the writers I see on Twitter have (or exhibit) a fiddle-dee-dee calmness about Author Life after a while. Even when talking about writing, they come across more like writer stereotypes with raised eyebrows, corncob pipes, and some bitterness and cynicism rather than people who are bright-eyed and enthusiastic about writing.

But you, in the previous answer and always, even after so many books, seem bright-eyed and enthusiastic. Excited. Wowed by the whole process. What excites you about all of it, even now?

Oh, what a lovely thing to say about me! Thank you.

I tend to look at the world with a sense of wonder. I know from my own life (let’s see, fiancé dies in my arms two weeks before our wedding, I go into coma three days after giving birth to my son, ninth novel rejected as not special, then it becomes NYT bestseller…) that things can change in a nanosecond—and that means things can change in WONDERFUL ways, too.

I feel so incredibly lucky to be able to do something that I am passionate about, that I love, and that I’m good enough at to be published. I have held job-jobs and I was always fired, or I didn’t fit into the corporate culture (one performance review, a “competent plus,” said that I needed “to dress more coherently”), and I was pretty unhappy. But truthfully, who knows what is going to happen next? I could sink into obscurity and never publish again, or I could get a movie deal.

What matters is the work—the joy in doing it. Every day, I stop and think, I’m so lucky that I get to be a writer, I’m so lucky, and I’m so grateful.

I know you recently experienced a change in editors at Algonquin. How long did you have your previous editor there, and what’s it like when that kind of change happens to someone so firmly established at a publishing house?

Algonquin is my home! I’ve had about five other publishers before them, including the really big ones, and Algonquin was the first place where I really felt seen, taken care of, and cared about. All the editors and marketing and sales and publicists know the authors, and it really is like a family.

Before I got to them, my ninth novel, Pictures of You, was rejected on contract by a different, big publisher as “not special,” and they didn’t want to see anything else from me, so I was sure my career was over. Then a friend got me to this fabulous editor at Algonquin, Andra Miller, who was virtually a “soul sister on the page.” Algonquin took that “non-special book” and got it into six printings before it was even out, and on the NYT bestseller list its second week out!

I did three novels with Andra over a period of about six years. Then a great opportunity came her way and she left, and I cried and cried and cried—and I was frightened. How would I write with someone else? What if it didn’t work out? Who else would be my editor?

But then, legendary editor Chuck Adams asked if he could work with me, and I was so honored that I instantly felt better. Of course, I was also scared, because how would this work? Turns out it worked beautifully.

Chuck is so, so smart and intuitive, and so incredibly kind and gentle—and he’s also really, really fun to work with and he helped me solve so many issues, including backstory. Best of all, he bought my next book after With or Without You, which I am writing now. I’m totally indebted to him, and I’ve already told him he can’t leave!

What is your next novel about, or what does it explore (as much as you’re willing to say), and what prompted it?

This is from Publisher’s Marketplace, because it’s too hard for me to explain what it’s about right now because I’m still writing it!

NYT-bestselling author Caroline Leavitt’s DAYS OF WONDER, about a young troubled woman, released six years early from prison for a crime she and her then 15-year-old boyfriend may or may not be guilty of, struggling to reinvent herself as she searches for the baby she gave away when she was incarcerated and for the boyfriend who might have betrayed her.

I was interested in memory (again), and who we are, and it was precipitated by a friend of mine who had a best friend she loved—everyone loved this friend!—and she introduced me, and I loved her, too, and then my friend told me that this woman had been sent to prison for murder when she was just 15.

My mind exploded! Here was this amazing, amazing woman and she had done something so terrible when she was so young, and even though America is always saying how much we love second chances, this woman felt the need to keep her past as much of a secret as she could.

How long, on average, does it take you to complete a first draft, and how do you know when the story is one you’re prepared to spend that much time and energy working on? Have you ever started and abandoned a novel because it just didn’t end up fueling you the way you thought it would?

Wow. Another great question. The truth is that my novels are usually percolating for years before I’m able to actually write them—mostly because I don’t know how to tell the story yet. It takes a lot of wrong starts. I abandon a lot of false starts, but the story always gets to get told—sometimes in the wrong way, so I have to start yet AGAIN, but it gets told.

I used to panic when I felt a story wasn’t fueling me, but now I know it’s just my pesky subconscious roaming around and that the next day will be better. I’ve come to love the moments when I feel, “What the hell am I doing? Why didn’t I go to dental school? This is the worst thing I’ve ever done”—because I know that my subconscious is digging a little deeper, excavating, and in the next day or two, it will show me at least a glint of something gold.

You spend a lot of time, and you put a lot of energy into, helping other writers. You blurb their books, you interview them on your blog CarolineLeavittville, and more.

Writers helping writers is also something you frequently write about on Facebook, and it makes me think you must have received similar help as you were coming up. What was the most helpful thing, or what were the most helpful things, others did for you when you were emerging as an author?

I had so much help!

My two biggest fairy godmothers were Jodi Picoult and Annie Lamott. Jodi Picoult initially said she was too busy to read Pictures of You for a blurb, but that she would try, and she read it, blurbed it gorgeously, and then, without telling me, raved about it in the print edition of Newsweek! People would email me and say they had gone to see Jodi, and in front of a 500-person crowd she told people about my book! We’ve become friends! And I don’t know why I did this, but one day when I was really blue, I thought, “Annie Lamott would understand this kind of sorrow,” and I wrote her a letter. And she called me! We became friends. She interviewed me for my book launch, and now she emails me authors she wants me to promote, and I always do. For a lark, I invited Lisa Scottaline to a reading, never expecting anything, and when I got to the bookstore, the owner told me she had called to say she couldn’t make it and had bought 12 hardbacks of mine! We, too, are now the best of friends. Adriana Tragiani did this amazing thing at a library talk. There were 100 librarians there and four authors, and she went last, and the first thing she did was hold up all our books and talk about them and tell everyone to buy them. I adore her. Gail Godwin has been amazing. I told myself that if I were ever in a position to help someone, I would pay it all forward.

Sometimes it was just someone tweeting to me that they had read my book, or that they liked it. I almost feel that it is karmic. I started my interview blog to help writers because I felt I had been helped and also because I had a hunger to know other writers, and it soon ballooned. Writers really do help writers, and it is a truly wonderful thing. It creates a better world, and it makes you feel so freaking good. Plus it helps the indie bookstores and readers, too.

A Mighty Blaze, the book initiative I co-founded with Jenna Blum, promotes this kind of culture. We try to put authors with other authors for interviews, to have “authors interview bookstores,” too.

With this week’s release of With or Without You and our talk of interviews and blurbs, I’m reminded of you telling me in an earlier interview about the colored folders you would prepare for book tour visits to brick-and-mortar stores. What’s it like to have a new novel coming out during a time of isolation, face masks, no gatherings…?

print / ebook

print / ebookIt’s so strange! I am actually busier than ever! Before, the day might be rush to the airport, get to the hotel, calm down, do an event. Now, it’s rush to the shower, Zoom an interview for an hour, have a free hour, then Zoom a festival, wait an hour, then talk to someone on the radio.

There are gatherings on Zoom, with people asking questions and showing their faces, which I love, but I’ve traded the anxiety of missing flights and trains with Zoom not working.

Oh, and those neatly organized colored folders? A total mess now! Those author outfits I bought specially for tour? In the closet, because who wears a dress now when you can wear yoga pants?

Thank you, Caroline.

August 3, 2020

How to Do Honest and Legal Giveaways as an Author

Today’s guest post is by author Chrys Fey (@ChrysFey), author of Keep Writing with Fey.

When doing giveaways as an author, it’s important to conduct a lawful giveaway (and stay on the right side of Amazon’s terms of service) that protects the rights of the entrants.

Before I outline important principles to follow, I’d like to recommend Rafflecopter, a free-to-join website that makes setting up a giveaway easy. In fact, a number of the techniques I’ll discuss are specific to their platform. Rafflecopter takes a lot of the work off your shoulders. You don’t have to worry about storing entrants’ information and keeping it private, because this data is stored by Rafflecopter. You also don’t have to manually input entrants into a random generator to pick a winner; when you’re ready, Rafflecopter will do that for you at the click of a button.

Through Rafflecopter, you can create a giveaway form for your website. People who want to enter can easily do so and earn points by completing tasks such as visiting a Facebook fan page or tweeting a message about the giveaway. (More on that in a bit.) Rafflecopter also provides a direct link to your giveaway page, which you can use when you announce the giveaway on social media sites.

Decide on giveaway entry optionsThere are many ways to allow people to enter your giveaway, and which ones you choose will depend upon your ultimate goals: Are you trying to grow your mailing list? Boost your social media following? Drive engagement? Here are some common options:

Visit a Facebook fan pageTweet a messagePin an image (Pinterest)Answer a pollSubscribe to a mailing listFollow an account (Twitter, Pinterest, etc.)Comment on a blog postInvent your own!Some of these options, such as subscribing to a mailing list, are available only in the paid tiers of Rafflecopter. If you do not want to pay to upgrade (I never have), you can use the “invent your own” feature to steer around the restrictions. For example, when you use the “invent your own” option to get subscriptions for your newsletter, you can use a link button that takes entrants to your mailing list sign-up form. (However, don’t forget to add wording in this option explaining that entrants have to confirm their subscription to your newsletter to be eligible. This helps you guarantee that most entrants will follow through.)

Earning entry pointsFor each entry option you create, you can assign a value from 5 points to 1 point. You’ll want to give your most desired options the largest value. I strongly suggest offering 5 points for the mailing list signup, given its importance.

I’d also create a free entry option worth one point where people who want to enter your giveaway don’t have to do a thing to claim that point.

Include terms and conditionsTerms and conditions are essential; this offers information that entrants have the right to know and can protect you in case of problems. Fill out the Terms & Conditions for your giveaway on Rafflecopter on the righthand side of the setup page. Even if you aren’t using Rafflecopter, you want to have this information available on your website or blog or wherever your giveaway is hosted. Here’s what to add or consider.

Right away, by itself, insert the words “NO PURCHASE NECESSARY.” This is essential and necessary. More on this below.Giveaway NameSponsor: Your NameContact Details: Your EmailEligibility: Is your giveaway open to US only or other countries?Number of WinnersPrizes Given to Winner: What are you giving away? List them.Giveaway Starts: Date and timeGiveaway Ends: Date and timeHow to Enter: Explain how people can enter the giveaway. For example, you might say. “Subscribe to My Newsletter. By subscribing to my newsletter and completing the double opt-in process, entrants are consenting to receive my author newsletter after the giveaway ends. Only entrants that have confirmed and fully subscribed will be eligible.” For each entry method, I include wording that says something like “This task is optional. Entrants willingly choose whether to complete it.”Social Network Disclaimers: Mention that the social media sites where you may share your giveaway announcement or use to gain entry points do not endorse, sponsor, or administer your giveaway.Winner Selection: How will the winner be picked? For Rafflecopter you can say, “The winner will be randomly chosen by Rafflecopter’s generator.”Winner Notification: Who will be contacting the winner and how (usually it’s through the email address provided by the entrant when logging in to the giveaway)Shipping: How long will it take you to send or ship the prize(s) after receiving the winner’s address? Include a statement that says you won’t be held liable for prizes that are damaged or lost in transit. I also add, “All prizes are mailed in excellent condition.”Privacy Policy: State that all information will be kept private and that the only data you will use will be for the purposes of contacting the winner(s) and shipping the prize(s). You can also provide a link to Rafflecopter’s Privacy Policy if you’re using their service.Giveaway Don’tsYou cannot use entrants’ information for anything other than to contact the winner. That means you can’t use their email address or mailing address or any other information to contact them for marketing purposes, unless—for example—they willingly signed up for your email newsletter to enter the giveaway.You cannot use entrants’ information to manually sign them up for your newsletter/mailing list. Make that an option that they can choose to do themselves.You cannot require people to buy your book (or anything else) in order to enter your giveaway. This is illegal. It can’t even be an optional entry. And, because you can’t require people to pay for something to enter, you can’t ask for proof of purchase. This is known as the NO PURCHASE NECESSARY law.You cannot force the winner to pay for shipping. This goes along with the above. You are responsible for shipping costs.You cannot require people to review your book in order to enter your giveaway. This is against Amazon’s Terms of Service.By following these steps, you will have a sound and ethical giveaway. If you see someone else running a giveaway that’s against the law, you may want to let them know privately, because many are not aware of these guidelines and laws and don’t know they are doing anything wrong.

Good luck to you, and good luck to your future giveaway entrants!

July 30, 2020

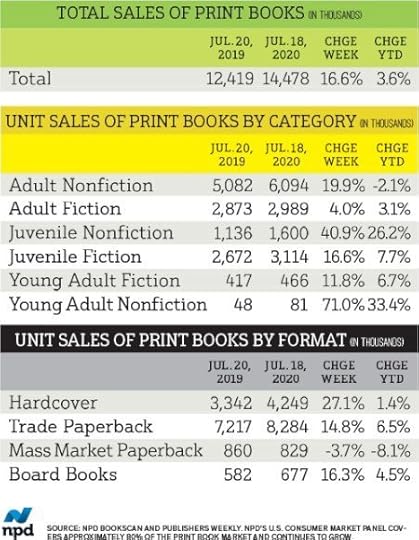

US Book Publishing Remains Resilient: Print and Ebook Sales Are Growing

Today’s post features information that originally appeared in my paid newsletter, The Hot Sheet.

As much of the retail world faces crisis, book publishing is positioned to grow in terms of unit sales when compared to 2019. In fact, 2020 may prove to be one of the strongest sales years in recent memory.

A few factors are likely contributing to the resilience of sales:

the prevalence of online purchasing in the US market (driven by Amazon, of course)the strength of Ingram’s print-on-demand operations in the US—and the overall robustness of the US supply chain thus farthe current events/bestseller effect, with race relations and politics driving high sales of titles such as White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo, How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi, John Bolton’s The Room Where It Happened, and Mary Trump’s Too Much and Never Enough. (Outperforming titles can bring a book category into a growth position or soften—even turn around—a decline for the market.)the high adoption rate of ebooks and audiobooks in the US market prior to the pandemicthe migration of print sales to big-box retailers, as written about by the New York Times.Let’s dig deeper into what’s happening.

US print unit sales are up by 3.6% so far versus 2019

This data comes from NPD BookScan, which tracks sales through retailers; it’s the best industry measure available for traditional publishing sales. According to their latest report, print sales growth is driven by:

children’s nonfiction, up by 26% over 2019nonfiction books on race relations and social justicechildren’s fiction (excluding YA), up by 7.7%YA fiction, up by 6.7%adult fiction, up by 3.1%graphic novels, up by 10.3%To find signs of trouble, you have to look at the challenged textbook market (a result of closed schools), a sales category not really captured by NPD BookScan. Other markets, like the UK, are seeing that same decline.

It’s possible that even though unit sales will increase in 2020, dollars may decline. A high volume of sales during the COVID lockdown have been for lower-priced books, such as juvenile nonfiction titles.

In the juvenile sector, the best performing categories include education and reference (of course, due to schooling needs), games and activities (to keep kids occupied and entertained), and other educational categories like history/sports/people/places and biographies. Publishers with nonfiction content in the educational and homeschool space—especially those serving the younger end of the scale—will have a very good year.

US ebook sales are up by 4% versus last year—an excellent resultUS traditional publishers report 4.3% growth in ebook sales through May 2020, after years of decline. All of that growth is the result of the pandemic; during the first three months of 2020, NPD showed ebook sales down 18% versus 2019. Publishing Perspectives offers more detail on ebook sales trends, with category-specific information.

Bricks-and-mortar bookstore sales are downThe US Census Bureau publishes preliminary estimates of bookstore sales, and even though print unit sales are up according to NPD BookScan, the government report shows bookstore sales declining by 33 percent in March, 65 percent in April, and 59 percent in May. The most obvious explanation for why book publishing continues to perform well as an industry: print sales have drifted to online channels, such as Amazon or Bookshop, and to big-box stores.

Barnes & Noble CEO James Daunt says that its sales are down about 20 percent overall from last year.

UK print sales aren’t doing as wellUK started the year positive: the first quarter saw 3% growth in unit sales. But that growth started to decline in February, and sales dipped even further once lockdown hit. Right now, the UK market is estimated to be down by 11% versus last year. Interestingly: UK’s online book purchasing in 2020 has modestly increased to 38% from 2019’s 36%. We have to wonder if this has contributed to the UK’s weakness in sales versus the US market—or maybe it’s simply that the US market has a higher rate of online purchasing already, at an estimated 50% of sales.

Audiobook sales grew in 2019, but at a slower pace

According to the Audiobook Publishers Association, audiobook growth slowed considerably in 2019, declining to 16.4 percent dollar growth versus 34.7 percent in 2018. Review more data from the Audio Publishers Association.

Regardless, everyone expects more growth in audio—and it will come from many parts of the world and from multiple formats and business models. Javier Celaya of Dosdoce believes, at current growth rates, audiobook/podcast revenue will surpass ebook revenue by 2023. Although there are twice as many podcast listeners as audiobook listeners, each audiobook listener generates more than 2.4 times the annual revenue of a podcast listener.

Subscription services are growing at a faster rate in Europe and emerging markets. And they are growing faster than audiobook unit sales, still the dominant model in the US (which is perhaps not the happiest trend for big US publishers who have pulled out of subscription services due to profitability concerns). In Sweden, perhaps the most mature market for audiobooks—where subscription service Storytel is based—audio makes up half of all fiction sales.

What might happen next?According to Kristen McLean at NPD Books, it won’t be demand that determines the industry’s future. Rather, she says it will be driven by:

The stability of the channels which are currently selling and delivering books. Will stores stay open? Will the supply chain (printers, print-on-demand facilities, other delivery channels) remain resilient?The length and depth of the economic crisis which has been unfolding. Will governments help consumers, businesses and others?The pre-existing (financial) health of the businesses in the traditional book industry. Do they have the capital and the resources to get through this?

The stability of the channels which are currently selling and delivering books. Will stores stay open? Will the supply chain (printers, print-on-demand facilities, other delivery channels) remain resilient?The length and depth of the economic crisis which has been unfolding. Will governments help consumers, businesses and others?The pre-existing (financial) health of the businesses in the traditional book industry. Do they have the capital and the resources to get through this?If you enjoyed this post, consider signing up for The Hot Sheet, the essential industry read for authors. You can try the first two issues for free.

July 29, 2020

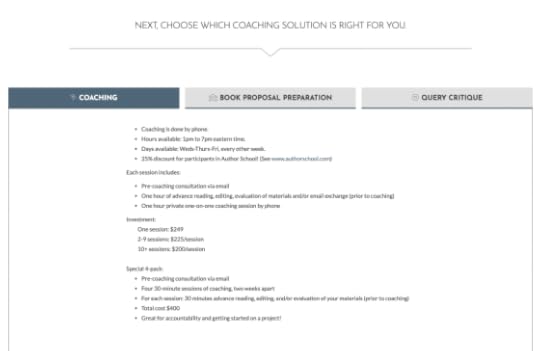

3 Keys to Freelance Editing: Position, Package, and Price

Note from Jane: Next week, in partnership with Creative Nonfiction, I’m teaching an online class on The Key to Freelance Success: FOCUS! Today’s post offers a look at some of the key areas I’ll be discussing.

When you’re starting out as a freelancer, it can be tempting to say yes to every project that comes your way. This is a trap that full-time writers, as well as those who supplement their income with freelance editing or coaching, can fall into.

But, as in writing, the key to success is often to go narrow. You can develop a more successful freelance business—and in particular an editing business—by being more focused and strategic with the three Ps: positioning, packaging, and pricing.

PositioningFirst things first: If you’re selling your services as an editor, you need to know the difference between the various types of editing out there. Be sure you understand terms like developmental editing, content editing, copyediting, and more. While it may be tempting to offer every type of editing that a writer might need, the truth is that most editors excel at or simply prefer one type of editing. And from a business perspective, it’s much easier to focus on marketing yourself for one type of editing.

Next: Consider what kind of writing you’re best positioned to edit—or the type of client you’re most qualified to help. Where do you have special experience or expertise? Where do you have credibility or credentials that your clients would find meaningful or trust? Here are some examples:

You’ve been a staffer at a romance review publication, have read and reviewed countless romances, and help judge contests. You’d be in a position to help beginning romance writers with their manuscripts, probably as a development or content editor.You have a degree in science and work in the communications department of a hospital. You know how to make complex ideas accessible to a general audience. You might be in a position to help doctors or other scientists develop their ideas into general-interest books.You worked in production at a small publishing house and performed copyediting and proofreading on books before publication. You could offer copyediting and proofreading services to book authors, likely in all categories.If you don’t have much in the way of experience or credentials, you might need to get some first. You could consider taking an online class to help you develop your skills; for example, there are a range of certification courses for copyediting and proofreading.

It greatly helps if you can specialize in not just the type of editing you perform, but in a particular type of client. For example, some editors focus on just emerging and early career authors or just authors in a particular genre; some focus on authors in a particular profession or from academia; still others will market themselves primarily to businesses or established professionals (like book publishers and packagers).

PackagingOnce you know who you’re trying to help, you can land more work by creating specific service packages to meet your clients’ needs, especially if you’re marketing to individuals. When potential authors see tangibly what you offer, it helps develop expectations and build trust—and it should give them a clear idea of whether there’s a match between the two of you. Packages can help clients better understand next steps when they’re feeling confused and unsure of how to proceed. By anticipating and establishing how clients’ key problems or challenges can be solved through your services, you’re showing you understand them and will be a valuable guide.

(What’s the opposite of offering packages? Telling people to reach out via email if they’re interested in working with you. For most freelancers, that’s not a good starting point, and it can waste a lot of time for both you and the client.)

Here’s an example of well-defined packages from Rachelle Gardner:

Doing this well requires truly understanding your target client. If you don’t have a good idea of who you’re serving, your packaging and your copywriting may be way off and unappealing to your potential clients. You must understand why your target client is driven to hire an editor, plus show you understand their fears and concerns in hiring an editor (often, that the editing will make things worse or be a waste of money).

You can cheat at your copywriting and package building by looking at established editors who are already catering to your target market, and seeing how they frame and package their services. But don’t lift other people’s copy wholesale; it has to be positioned to fit your voice, your capabilities, and what distinct value you bring to the table.

PricingBecause freelance editing is not scalable (you can’t take on an increasing number of clients without increasing hours worked), pricing can quickly become critical to a sustainable business.

Because you’re selling your time for money, and your time is limited, I find flat fees preferable to hourly fees. I’d rather sell the value of my service, and not my time. If I sell a $500 edit package that typically takes me two or three hours to complete, what matters most is (1) that my work or service is worth $500 to the client, (2) that I can attract clients at that rate, and (3) that I am satisfied to work at that rate.

Pricing can also play an important role in attracting the right client. If a service is priced at the low end of the market, this can actually attract less desirable clients, who are shopping only based on price and not the value or expertise you bring to the table. Furthermore, if you were indeed hired based on price and not expertise, the client may lack confidence in your work and be more likely to pick it apart.

This isn’t to say that high pricing is a panacea—people who pay premium prices expect premium services—but that competing based on price is risky, especially for a personalized service like editing.

All of the above raises a challenging question, though: Is charging per word for editing considered charging based on time or value?

Charging per word for novel editing is like charging based on time, given that you likely have calculated how long it takes for you to edit something like an 80,000-word novel and you charge accordingly. However, let’s consider three different scenarios.

1. Copyediting or proofreading jobs. Often editors will charge per-word or per-page. This gives the client an assured, fixed cost, and probably there’s some assurance for you as well because copyediting and proofreading tend to be straight-forward jobs. To charge based on value, consider variable per-word or per-page rates for copyediting and proofreading based on whether the job is heavy, medium, or light. You need to figure this out based on a look at the manuscript before you quote the job. This way you can charge for the value you’re providing and not just based on length. I would avoid a rate that applies universally to every single manuscript. On your website or in your marketing, you can list a cost range instead of a single price or fixed word rate.

2. Developmental or content editing. These are, IMHO, hardest to quote, because the work can be very intensive and span weeks or months, and involve a lot of back and forth with the client. If it makes sense for the project, quote a flat fee based on the value of the work you’ll be putting into the manuscript development (and the level of commitment required from you over time) rather than the number of hours you expect to put into the project. Of course you’ll want to mentally calculate how many hours the project will likely take you, but I’d come up with a figure that would make you feel satisfied or reasonably happy even if the job takes longer than expected. Try to have fixed deliverables to avoid mission creep. Build in a hard stop date or a specific milestone that, once reached, can trigger a new contract or additional payment so you’re not on the hook indefinitely when quoting a flat fee. (Still others will quote a retainer. There is no right way; only what best suits your personality and how you like to work.)

3. Manuscript evaluations. These are the easiest to quote and to charge for value, because you’re determining what clients send you and what you deliver back to them, and there’s usually a fixed value that doesn’t change from project to project. E.g., you agree to write a 2-page editorial letter for any manuscript up to 80,000 words that evaluates the strengths and weaknesses of the work, followed by a phone call to discuss. Or you look at the first 50 pages and do the same. Etc.

Parting adviceFor better or worse, the current marketplace is overrun by mediocre and poor editors. That’s partly because the growth of self-publishing has increased the number of people who are putting out their shingle. There isn’t any formal accreditation process for freelance editors, so anyone can call themselves one, and many set up shop with little experience or qualifications. This means that freelance editors can quite easily point to published works they’ve edited, which may not in fact be very high quality. So, it can take time to distinguish yourself from the many types of help available. Specializing in a type of editing or a particular client will help speed your start.

Note from Jane: Next week, in partnership with Creative Nonfiction, I’m teaching an online class on The Key to Freelance Success: FOCUS!

July 22, 2020

Why Write Memoir Right Now

Today’s post is by author and memoir coach Marion Roach Smith (@mroachsmith). On July 29 she’ll teach an online course called How to Research Your Life: A Memoir Writer’s Guide to Reporting; find out more and register here.

How will this global pandemic story play out? For most of us, this is the question for now. We stare off and wonder, thinking we have little control. If this is you, I have hard-won advice for this odd moment in our lives: Write. Specifically, write what you know.

If there are two phrases used more and understood less in writing than “write what you know,” and “show don’t tell,” I cannot think of them, and yet they are the two that will provide you some control right now.

Writing is a great portal to self-discovery. Specifically, writing memoir provokes the kind of discovery that often eludes us. As anyone who has experienced trauma will tell you, healing begins in having words for the experience. Name it and we begin our way home.

At the beginning of the pandemic, when I read Gwyneth Paltrow’s suggestion that this would be a great time to learn a new language, I spit my tea right onto my computer screen. No one I know is capable of conjugating in Italian as we scramble to survive. What we can do, though, is share our humanity across the virtual back fence by writing what we know. It’s not that writing memoir will fix what’s wrong. But writing what you know will give you the kind of insight that begets control, and if you show us how you got some control, we might find ways to get some, too.

Why write now?Why write, you might ask, when all I am going to discover right now is my fear?

Maybe. But let’s start with that fear. What fear is it like? What is familiar about it, and why is it familiar?

A few mornings ago, I awoke to a note in my own handwriting by my side of the bed. I am a writer, so this is normal. With notebooks tied to the gearshift of my car, in my purse and in the bathroom, I am forever scribbling. This note read, “Don’t flip the car keys to her.” Reading it, I smirked and snorted, since the “her” in that note refers to my inner child. I have an unsteady relationship with her, at best. Not a bit woo-woo, I live more on the delicatessen plan of spirituality, having taken small bites from a Lutheran Church beginning, Episcopalian girls school curriculum and a Universalist-based university at which I ingested the requisite 1970s menu of Carlos Castaneda, Taoism, Buddhism and the dawning of New Age.

But, as I focused on the note, the panic that produced it at 4:30 AM made me think, “You’re right, Marion. There’s a scared kid in there, and she’s not the one to ask to drive right now.” But I had been doing just that, so I was terrified.

Not flipping her the keys makes sense, not only because of the peril to my psyche, but also, since I’m a writer, because she is not a reliable narrator from which to write. What she does present is a perfectly good topic to write about. Each of us is experiencing this through the lens of our singular pathologies. Unexpressed, this leaves us alone and trembling. Examined, we are offered some control.

In 25 years of teaching, editing, coaching and writing memoir, I’ve worked with many people from what we now call the #MeToo movement. These folks lost a lot, not the least of which was their voice. They were told not to tell, that they wanted it, or liked or deserved what was being done to them, and that if they told they’d lose even more. Now, given language for what happened, these writers begin to take control of where that story goes next.

What is memoir?Memoir is what you know after something you’ve been through. It requires that the writer change, and that we get to watch that change. This is the definition of write what you know, that phrase that everyone tosses around but few bother to explain. What you know is how you changed. Along your way to your transcendence, you show, not tell, your way through those moments of change.

How do you show us? In scenes. Like beads on an abacus, your scenes merely need to add up to show us how you learned what it is you now know.

Oh, you’re probably saying now, no one wants to read about me.

You’re right. We do not want to read about you. We want to read about how your experience reveals something universal that we either do not understand, that is weighing on us, or that is beckoning our wonder. When I read a book by someone who ice picks her way up a frozen scree in Nepal, I do not do so because I plan to do it too. I read it to expand my expectations of human potential, refill my nearly empty well of courage and sharpen my flinty sense of determination. I read it to feel and feed. I read it to change.

How to write memoirSo, no, do not write about yourself. Write about the universal as illustrated by the personal. Give a name to those transactions you are now having over your masks, eye-to-eye with the check-out person at the grocery. Write from the lost sense of touching one another. Write from a vanquished—or renewed—sense of faith. Write from your knees with tears in your eyes or laughter in your mouth.

Why? Because we need to figure this out together and the shared universals are thrumming in the air like a tune waiting for some John Prine lyrics. Go on: Supply the words for what this is. Share them. We need them now more than ever.

If it’s not about you, what is it about?

Here is how to determine that. Use my little writing algorithm, offered to you in lieu of foreign language lessons in these perilous times. It goes like this:

It’s about x as illustrated by y to be told in a z.

It’s about something universal to be told by some deeply personal tale in some length—blog post, essay, op-ed or book. For example:

It’s about how mercy is a process that must be worked daily, as illustrated by forgiving my abuser, to be told in a personal essay.It’s about how dogs do things for people that people cannot do for themselves, as illustrated by the joy our dogs are creating in this time at home, as told in an op-ed.It’s about how grief is a mute sense of panic, as illustrated by my response—and transcendence through that response—to my mother’s descent into Alzheimer’s, as illustrated in my first book.Perhaps your anxiety dipped when baking in the cupcake tins of a grandmother who survived the 1918 flu and two world wars. That’s a laying on of hands like no other. Throw open the window and shout it out. Or better yet, write it down.

Share your humanityWe are not looking for big truths here. We are looking for small ones. And that is where memoir rules. There, amid our shared scatterbrained sense of panic, or in the indomitable hope of a Zoom seder, are expressions of humanity that bond us across every possible divide.

In a recent update to a book I wrote on how to write memoir, I edited out phrases like, “check your Blackberries,” swapped the word, “smartphones,” and added new observations on how to write what you know. It has been updated before, though in nine years in print, one of the book’s tales that needs no refresh goes like this:

.ugb-4806428-wrapper.ugb-container__wrapper{background-color:#eeeeee !important}.ugb-4806428-wrapper.ugb-container__wrapper:before{background-color:#eeeeee !important}.ugb-4806428-content-wrapper > h1,.ugb-4806428-content-wrapper > h2,.ugb-4806428-content-wrapper > h3,.ugb-4806428-content-wrapper > h4,.ugb-4806428-content-wrapper > h5,.ugb-4806428-content-wrapper > h6{color:#222222}.ugb-4806428-content-wrapper > p,.ugb-4806428-content-wrapper > ol li,.ugb-4806428-content-wrapper > ul li{color:#222222}If you’ve ever visited Woodstock, New York, you know the place is populated by a distinct kind of person—artistic, flamboyantly individualistic. Perhaps per capita, there are more poets and potters there than anywhere else on earth. I now teach online, but when I taught in person, many came to my class. Some years ago, three young women from Woodstock taught me more than I taught them. All weavers, they were a pair of sisters and the sisters’ best friend.

The first night, as I was asking what the class was going to write, the women—sitting in order of older sister, younger sister, and best friend—each replied that they were there to write the story of the recent death of the younger sister’s husband: For one another, not for publication, it was how they chose to honor his life.

And I imagine that the world kept spinning and they kept talking while I wondered how I was ever so fortunate to be asked to assist in such a purely noble effort. For one another, not for publication, because it needed to exist. The very idea stayed in my head until the following week, when they came in, each with her version of the death.

But they had switched seats, the two women no longer cushioning the young widow. This time, she was last of the three, as first her sister read a piece about taking the call that reported the young husband had been accidentally killed on the job. The best friend wrote of standing in the sun at the memorial, looking out over what would need to be the future for them all.

And then the little sister read. Maybe she was 30, married for only a few years, deeply in love with her husband, and after I tell you the next detail you will never forget it, perhaps even thinking of it most nights, as I do, all these years later, when I climb into bed with my husband.

The night her husband died, her sister stayed on after everyone else left. At bedtime, she asked her little sister how he had held her at night, and gently cupping one hand on her shoulder and the other over her hip, just as he always had, they fell asleep.

Feel what just happened?

That’s the kind of experience that memoir provides.

So, write.

Note from Jane: if you enjoyed this post, join Marion on July 29 for her online course How to Research Your Life: A Memoir Writer’s Guide to Reporting; find out more and register here.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers