Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 75

January 18, 2021

How to Restart Your Unfinished Book

Photo by

Bich Tran

from

Pexels

Photo by

Bich Tran

from

Pexels

Today’s post is by Allison K Williams (@GuerillaMemoir). Join Allison on January 22 for her next class, This Is the Year You’ll Finish Your Book.

Is this the year you recommit to a project that’s languished, unfinished, for months or years? The one where you think:

one day…

when I can dig out my notes…

and have a few solid hours to really dive in…

Newsflash: Your calendar will never magically pop up “Today You Can Focus Entirely on That One Project.” To finish that book on the back burner, you must actively bring it forward.

First, pick one. (You know you have more than one.)Which project gets you closer to a big life goal? Or envision boarding a lifeboat, where you’re allowed to bring only one manuscript. You probably already know in your heart. Part of every artist loves to dither, saying, Yeah, but if I work on that other thing, maybe… That dithering part of us is basically a three-year-old negotiating between a sundress or their superhero suit for preschool today. Mother Creativity doesn’t care, as long as we get out the door.

Pick the one you’re excited about, especially if it’s your first book.If you make money as a writer and you need money now, pick what makes the most money the fastest.If you make money as a writer and you don’t need money now, or you write for fun but want to make money eventually, pick the one you’re excited about. When you reach the murky middle, half-heartedness won’t get you through.It’s important to commit.Ask your project: What’s holding me back? Do you need more information? An outline of your story so far? A writing buddy for supportive coworking? Therapy?

Once you’ve chosen, your other works-in-progress will clamor for attention. Every project sounds more fun, more interesting, more exciting than sitting down to what you’ve chosen. This is normal. Your brain is afraid of a big commitment without guaranteed success, so it generates distractions. Stay committed. Write down shiny new ideas, but move on. Remind your brain they’ll be safe until you come back.

Restarting doesn’t have to mean from the beginning. You don’t have to rethink the whole project or make a huge plan or set aside two weeks when your decks are clear (let me just pencil that in for never).

Start small, by “touching” the manuscript almost every day. Don’t sternly assign yourself a word count yet—just take a walk or a shower and actively think about the story. Open up the file and read one page. Tweak a couple of paragraphs. Make a playlist that brings you back to the mood and voice. Keep touching your book, gently renewing your interest and energy until you’re ready to write.

Choose your most supportive, least critical reader and share passages you liked when you originally wrote them. For a restart, I read pages of an abandoned novel to my decidedly non-literary husband. I kept finding bits I liked and thinking OK, not as awful as I remembered. His questions and his “That’s not too bad” (he’s British, so that’s practically seventy-six trombones of enthusiasm) made me excited to dive back in.

Not finding that energy?You don’t actually have to be “inspired.” Inspiration is like walking into a factory, seeing conveyer belts and drill presses and steam generators and saying, “I could make something with this!” Someone still has to clock in and start work. Give it your best try for a week:

Use a prompt within your book. For example, every new sentence starts with the next letter of the alphabet. Or imagine an elevator stopping at a particular numbered floor—write about the main character at that age.Write the book jacket copy or synopsis to clarify the story in your head.Write about what you’re going to write: Scene with Sandy and me in the kitchen, when I realized she was dating my ex and it made me really uncomfortable. She had just dyed her hair blonde and I was alphabetizing the spice rack so I wouldn’t say she looked awful. She said…And before you know it, you’re writing the scene instead of about the scene. Or at least getting down the first draft by telling the story to yourself. You’ll fix the narrative in the second draft.

Showing up to your project whether or not you’re inspired creates energy and momentum. The most successful writers I know are not waiting for the conveyor belt to bring them the next widget—they’re unpacking parts with no instructions, rolling up their sleeves and tinkering. Working without inspiration can feel weird and awkward and not like your normal happy routine of writing when circumstances are just right (rarely!). See what it feels like to do whatever it takes, to revise or rebuild or seek help with your story.

And if that feeling sucks?

Let the project go.

Sometimes the space for what you want is filled with what you’ve settled for. Don’t settle for half-finished.

Let go of the hundredweights of half-pages that were once a great idea. Trust that in your head, in your heart, in your skill, there are multitudes more ideas. Your next beautiful book may be hiding under the weight of a project that feels like an obligation. Be grateful you learned what that writing taught you—then set it aside and commit fully to something you want to finish.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join me and Allison on January 22 for the online class This Is the Year You’ll Finish Your Book.

January 11, 2021

The Differences Between Line Editing, Copy Editing, and Proofreading

Photo by Maksim Goncharenok from Pexels

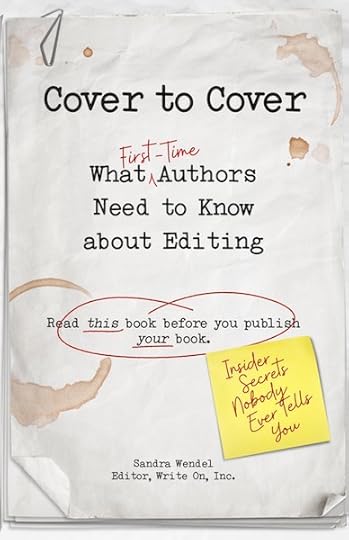

Photo by Maksim Goncharenok from PexelsToday’s guest post is an excerpt from the new book Cover to Cover: What First-Time Authors Need to Know about Editing by Sandra Wendel.

Editors disagree about many of the finer points of their work such as whether to capitalize the word president (no, generally, but yes with President Lincoln), whether to spell out numbers (some styles say yes to every number lower than 10 or lower than 100), or whether to use the serial comma that preceded this clause (Chicago Manual of Style says yes). Some purists would argue that this post’s headline should read among instead of between. But I digress.

Editors also disagree about whether to start a sentence with And. And of course editors disagree about what constitutes the levels of editing that are often labeled copy editing, line editing, and proofreading—or just simply editing.

For guidance, I turned to the authority, the Chicago manual. Yet even that widely accepted all-knowing guide doesn’t make a distinction among editing levels: “Manuscript editing, also called copy editing or line editing, requires attention to every word and mark of punctuation in a manuscript, a thorough knowledge of the style to be followed, and the ability to make quick, logical, and defensible decisions.”

New authors are often confused about what level of editing they need, and rightly so. I hope to offer insight into the differences between line editing, copy editing, and proofreading.

[Note from Jane: If you’d like to learn about development editing and content editing, which should come before copy editing, line editing, or proofreading, please see this comprehensive post on finding an editor.]

What to Expect with a Line EditIn a line edit, an editor examines every word and every sentence and every paragraph and every section and every chapter and the entirety of your written manuscript. Typos, wrong words, misspellings, double words, punctuation, run-on sentences, long paragraphs, subheadings, chapter titles, table of contents, author bios—everything is scrutinized, corrected, tracked, and commented on.

Facts are checked, name spellings of people and places are confirmed. This is the type of edit I perform most often.

Your editor will likely do the following:

Conduct heavier fact checking (for example, exact titles of movies in italics, death date of a famous person in history, the protagonist was using an iPhone before they were invented).Make suggestions about moving or removing text (or actually doing the task and explaining in a marginal note why).Initiate a discussion about why the dreary Introduction could be cut.Offer a new scheme for moving a chapter or two around to better accommodate a time line. (Actually doing the moving and writing transitions might fall into the category of developmental edit or left to the author to do.)Query the author in a marginal note about why Susan in chapter 2 was wearing a winter coat when the scene takes place in summer. Or whether the author intended for the detective described earlier with a full beard to be scratching his stubble.Point out repetition and inconsistencies in the story line. But not rewriting. Actually revise awkward sentences, break up long sentences, streamline sentences with clauses and parentheticals. Recast sentences that begin with There are and It is. Those constructions are simply not strong. That’s why line editing is considered a sentence-level type of edit.Substitute stronger words for the commonly overused words (very, pretty, things, great, and good are my pet peeves).Let me show you what an edit can do. This is a paragraph from Chris Meyer’s book Life in 20 Lessons. Chris is a funeral home director. A line edit would turn this rough paragraph—

The more regular are the things that make life so cruel and unfair: a healthy man has a heart attack on his bike ride, a child stricken with cancer, a mother dying before her children reach middle school, a father on vacation with his children, a son abalone fishing because it brings him joy, a daughter in an auto wreck with her best girlfriends, a simple slip and fall, gunshots, the list is as endless as it is tragic.

—into this:

What to Expect from a Copy EditMore likely are the events surrounding death that make life so cruel and unfair: a healthy man has a heart attack on his bike ride; a child is stricken with leukemia; a mother dies before her children reach middle school; a father suffers a fatal stroke while on vacation with his children; a son drowns while abalone fishing; a daughter is killed instantly in an auto wreck with her best girlfriends; a simple slip and fall, gunshots, the list is as endless as it is tragic.

When an author says, “I just want a copy edit,” I ask what they mean. Again, there is confusion about what a copy edit includes. Most of the time, authors want that thorough line edit. If a manuscript is so clean, so squeaky clean, so perfectly written with lovely paragraphing and fine-tuned punctuation, then maybe the manuscript just needs a copy edit. Like never. I can’t even recall a manuscript that has come to me this clean that it would need just one pass for a polish for mechanical issues. Never. Not even books written by professional writers. And not even my own book. I hired out my line editing, and it’s a humbling process.

So let’s just agree that when someone says copy edit, they really mean a much deeper and more thorough edit than putting commas in the right place. A copy edit is the lowest level of edit. Rarely does a manuscript need “just” a copy edit. Sometimes a copy edit is a final step performed separately by your editor or someone else with fresh eyes. Some editors (like me) do copy editing all along looking for these types of errors, and a copy edit is part of the line edit.

Here’s my simple checklist:

Correct any typos, which would include misspelled words.Fill in missing words.Format the manuscript before production, and that includes just one space between sentences (I don’t care what you learned in typing class in high school, the double space messes up the document when it is converted into real book pages).Streamline punctuation and properly use commas, periods, and em dashes—like this.Avoid overuse of ellipses to denote a break in thought … when they are really used to show missing text. And those exclamation marks! I allow authors about five in each manuscript. Overuse them, and they lose their punch.Make sure the names of characters and places are spelled consistently throughout (Peterson in chapter 1 may or may not be the same Petersen in chapter 6).Find and replace similarly sounding words that have different meanings (for example, effect and affect).Conduct a modest fact check (perform a Google search to find the exact spelling of Katharine Hepburn or the capital of Mongolia). This isn’t Jeopardy!, so you do get to consult resources. I keep a window open to Google just for such searches.Make new paragraphs to break up long passages.Question the use of song lyrics and remind the author to get written permission.Point out, in academic work, that footnote 6 does not have a reference source in the citations.Remove overuse of quotation marks. For emphasis, use italics, but sparingly. Books generally do not use boldface.Impose a consistent style for the text (this means using a style guide for capitalization and hyphenation, treatment of numbers, heading levels). The Chicago Manual of Style is preferred unless the work needs to conform to an academic convention such as APA, AMA, or MLA.What to Expect from a ProofreadLet’s say your manuscript is fully edited (no matter which level you chose, sometimes even a developmental followed by a line edit with the same or different editors). Your work will need a proofread either in manuscript format or after it is designed in pages as PDFs.

Should you proofread your own work? The short answer is later, if you’re in writing mode. The shorter answer is never. Why? Because it’s your work. And your brain plays funny tricks on you. It will fill in your words, and you’ll be completely shocked when a professional editor returns your edited manuscript. What? How could I miss that?

Most editors won’t admit this, but we, too, miss things. We’re human (or many of us are). So the question on the table is when to proofread.

I prefer to hire proofreaders to proof for absolute error when the manuscript is in final pages or PDFs. But you can also proofread before it goes into production (and into PDFs), just knowing that you do need another proofing of the PDFs.

Use a different person, a different editor, even someone who is a professional proofreader. This person brings a fresh set of eyes to the work and scours for absolute error such as name misspellings, wrong URLs, bad URLs, numbers that don’t add up in a table, double words, missing words, and those crazy stupid errors you as the author have missed and your editor missed, and you question your sanity. Those errors.

A proofreader doing the proofing at the PDF stage will look for all these types of errors plus others: bad word breaks and hyphenation at the end of a line, hyphen stacks (many words hyphenated at the ends of lines, stacked), widows and orphans (single words or lines at the top or bottom of a page), wrong captions with photos, page numbering, missing and misspelled headers and footers, page numbering matches with the table of contents, lines too tight or too loose. Many of these production issues are introduced as pages are created.

Proofreading is not the time to revise, rewrite, and delete. Your interior page designer might actually kill you. At the very least, major changes in proofing in PDFs can be time intensive and expensive. Put in the work way before you see your baby in actual page layouts.

Parting Advice print / ebook

print / ebookAs Random House copy chief Benjamin Dreyer said in his exceptionally fascinating book, Dreyer’s English, “My job is to lay my hands on that piece of writing and make it … better. Cleaner. Clearer. More efficient. Not to rewrite it … but to burnish and polish it and make it the best possible version of itself that it can be.”

In editing world, even if editors disagree on what constitutes certain types of editing, we do agree that your manuscript deserves a professional and sound edit to make it free of typical errors of spelling and punctuation, with proper use of the right word, judicial paragraphing, logical chapter breaks and chapter titles, and prudent fact checking for accuracy—and, above all, consistency.

Note from Jane: if you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out Sandra’s new book Cover to Cover: What First-Time Authors Need to Know about Editing.

January 4, 2021

The Key Book Publishing Paths: 2021–2022

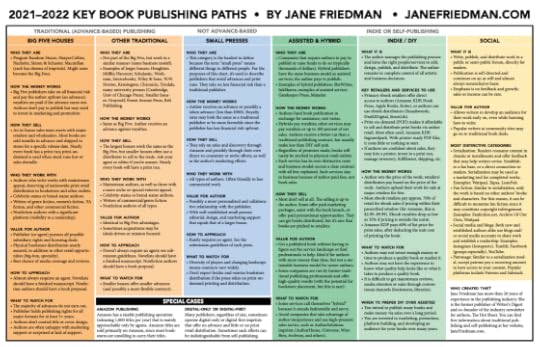

Since 2013, I have been regularly updating this informational chart about the key book publishing paths. It is available as a PDF download—ideal for photocopying and distributing for workshops and classrooms—plus the full text is also below.

One of the biggest questions I hear from authors today: Should I traditionally publish or self-publish?

This is an increasingly complicated question to answer because:

There are now many varieties of traditional publishing and self-publishing, with evolving models and diverse contracts.You won’t find a universal, agreed-upon definition of what it means to traditionally publish or self-publish.It’s not an either/or proposition; you can do both. Many successful authors, including myself, decide which path is best based on our goals and career level.

Thus, there is no one path or service that’s right for everyone all the time; you should take time to understand the landscape and make a decision based on long-term career goals, as well as the unique qualities of your work. Your choice should also be guided by your own personality (are you an entrepreneurial sort?) and experience as an author (do you have the slightest idea what you’re doing?).

My chart divides the field into traditional (advance-based) publishing, small presses, assisted publishing, indie or self-publishing, and social publishing.

Traditional publishing (the big guys and the little guys): I define traditional publishing primarily as receiving payment from a publisher in the form of an advance. Whether they’re a Big Five publisher or a smaller house, the traditional publisher assumes all financial risk and typically invests in a print run for the book. The author may see no other income from the book aside from the advance; in today’s industry, it’s commonly accepted that most book advances don’t earn out. However, authors do not have to pay back the advance; that’s the risk the publisher takes.Small presses. This is the category most open to interpretation among authors; for the purposes of this chart, I’m defining small presses as publishers who take on less financial risk because they pay no advance and avoid print runs. Authors must exercise caution when signing with small presses; some mom-and-pop operations offer little advantage over self-publishing, especially when it comes to distribution and sales muscle. Also, think carefully before signing a no-advance deal or digital-only deal, which are sometimes offered even by the big traditional houses; you may not receive the same support and investment from the publisher on marketing and distribution. The less financial risk the publisher accepts, the more flexible your contract should be—and ideally they’ll also offer higher royalty rates.Assisted and hybrid publishing. This is where you pay to publish and enter into an agreement or contract with a publishing service or a hybrid publisher. Once upon a time, this was called “vanity” publishing, but I don’t like that term. Costs vary widely (low four figures to well into the five figures). There is a risk of paying too much money for basic services or purchasing services you don’t need. Some people ask me about the difference between a hybrid publisher and other publishing services. Usually there isn’t a difference, but here’s a more detailed answer. The Independent Book Publishers Association also offers a set of criteria for evaluating hybrid publishers.Indie or DIY self-publishing. I define this as publishing on your own, where you essentially start your own publishing company, and directly hire and manage all help needed. Here’s an in-depth discussion of self-publishing.Social publishing. Social efforts will always be an important and meaningful way that writers build a readership and gain attention, and it’s not necessary to publish and distribute a book to say that you’re an active and published writer. Plus, these social forms of publishing increasingly have monetization built in, such as Patreon.

Feel free to download, print, and share this chart however you like; no permission is required. It’s formatted to print perfectly on 11″ x 17″ or tabloid-size paper. Below I’ve pasted the full text from the chart.

Big Five Houses (Traditional Publishing)

Who they are

Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Hachette, Simon & Schuster, Macmillan (each has dozens of imprints). Might soon become the Big Four if Penguin Random House does in fact acquire Simon & Schuster (deal requires regulatory approval).

How the money works

Big Five publishers take on all financial risk and pay the author upfront (an advance); royalties are paid if the advance earns out. Authors don’t pay to publish but may need to invest in marketing and promotion.

How they sell

The Big Five have an in-house sales team and meet with major retailers and wholesalers. Most books are sold months in advance and shipped to stores for a specific release date. Nearly every book has a print run; print-on-demand may be used when stock runs low or sales dwindle.

Who they work with

Authors who write works with mainstream appeal, deserving of nationwide print retail distribution in bookstores and other outlets.Celebrity-status or brand-name authors.Writers of genre fiction, women’s fiction, YA fiction, and other commercial fiction.Nonfiction authors with a significant platform (visibility to a readership).

Value for author

Publisher (or agent) pursues all possible subsidiary rights and licensing deals.Physical bookstore distribution nearly assured, in addition to other retail opportunities (big-box, specialty).Best chance of media coverage and reviews.

How to approach

Almost always requires an agent. Novelists should have a finished manuscript. Nonfiction authors should have a book proposal.

What to watch for

The majority of advances do not earn out.Publisher holds onto all publishing rights for all major formats for at least 5+ years.You don’t control title or cover design.Authors may be unhappy with marketing support or surprised at lack of support. Here are questions to ask your publisher before you sign a deal.

Other Traditional Publishers

Who they are

Not part of the Big Five, but work in a similar manner (similar business model).Examples of larger houses: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Scholastic, Workman, Sourcebooks, John Wiley & Sons, W.W. Norton, Kensington, Chronicle, Tyndale, many university presses (Cambridge, Univ of Chicago Press). Smaller houses: Graywolf, Forest Avenue Press, Belt Publishing.

How the money works

Same as Big Five. Author receives an advance against royalties.

How they sell

The largest houses work the same as the Big Five, but smaller houses often use a distributor to sell to the trade. Ask your agent or editor if you’re unsure. Nearly every book will have a print run.

Who they work with

Authors who write mainstream works, as well as those that have a more niche or special-interest appeal.Celebrity-status or brand-name authors.Writers of commercial/genre fiction.Nonfiction authors of all types.

Value for author

Identical to Big Five advantages.Sometimes acquisitions may be ideals driven or mission focused.

How to approach

Doesn’t always require an agent; see submission guidelines for each publisher. Novelists should have a finished manuscript. Nonfiction authors should have a book proposal.

What to watch for

Smaller houses offer smaller advances (and possibly a more flexible contract).

Small Presses

Who they are

This category is the hardest to define because the term “small press” means different things to different people. For the purposes of this comparison chart, it’s used to describe publishers that avoid advances and print runs. Thus, they take on less financial risk than a traditional publisher.

How the money works

Author receives no advance or possibly a token advance (less than $500). Royalty rates may look the same as a traditional publisher or be more favorable since the publisher has less financial risk upfront.

How they sell

They rely on sales and discovery through Amazon and possibly through their own direct-to-consumer or niche efforts, as well as the author’s marketing efforts.

Who they work with

All types of authors. Often friendly to less commercial work.

Value for author

Possibly a more personalized and collaborative relationship with the publisher.With well-established small presses: editorial, design, and marketing support that equals that of a larger house.

How to approach

Rarely requires an agent. See the submission guidelines of each press.

What to watch for

Diversity of players and changing landscape means contracts vary widely.Don’t expect bricks-and-mortar bookstore distribution if the press relies on print-on-demand printing and distribution.Potential for media or review coverage declines without a print run.Carefully evaluate a small press’s abilities before signing with one. Protect your rights if you’re shouldering most of the risk and effort.

Assisted and Hybrid Publishing (Self-Publishing)

Who they are

Companies that require you to pay to publish or raise funds to do so (typically thousands of dollars). Hybrid publishers have the same business model as assisted services; the author pays to publish.Examples of hybrid publishers: SheWrites, InkShares; examples of assisted service: Gatekeeper Press, Matador

How the money works

Authors fund book publication in exchange for assistance; cost varies.Hybrid publishers pay royalties; other services may pay royalties or up to 100 percent of net sales. Authors receive a better cut than a traditional publishing contract, but usually make less than DIY self-pub.Regardless of promises made, books will rarely be stocked in physical retail outlets.Each service has its own distinctive costs and business model; secure a clear contract with all fees explained. Such services stay in business because of author-paid fees, not book sales.

How they sell

Most don’t sell at all. The selling is up to the author. Some offer paid marketing packages, assist with the book launch, or offer paid promotional opportunities. They can get books distributed, but it’s rare that books are pitched to retailers.

Value for author

Get a published book without having to figure out the service landscape or find professionals to help. Ideal for authors with more money than time, but not a sustainable business model for career authors.Some companies are run by former traditional publishing professionals and offer high-quality results (with the potential for bookstore placement, but this is rare).

What to watch for

Some services call themselves “hybrid” because it sounds fashionable and savvy.Avoid companies that take advantage of author inexperience and use high-pressure sales tactics, such as AuthorSolutions imprints (AuthorHouse, iUniverse, WestBow, Archway, and others).

Indie or DIY Self-Publishing

What it is

The author manages the publishing process and hires the right people/services to edit, design, publish, and distribute. The author remains in complete control of all artistic and business decisions.

Key retailers and services to use

Primary ebook retailers offer direct access to authors (Amazon KDP, Nook Press, Apple Books, Kobo), or authors can use ebook distributors (Smashwords, Draft2Digital, StreetLib).Print-on-demand (POD) makes it affordable to sell and distribute print books via online retail. Most often used: Amazon KDP, IngramSpark. With printer-ready PDF files, it costs little or nothing to start.If authors are confident about sales, they may hire a printer, invest in a print run, manage inventory, fulfillment, shipping, etc.

How the money works

Author sets the price of the work; retailers/distributors pay you based on the price of the work. Authors upload their work for sale at major retailers for free.Most ebook retailers pay approx. 70% of retail for ebook sales if you price within their proscribed window (for Amazon, this is $2.99–$9.99). Ebook royalties drop as low as 35% if pricing is outside the norm.Amazon KDP pays 60% of list price for print sales, after deducting the unit cost of printing the book.

What to watch for

Authors may not invest enough money or time to produce a quality book or market it.Authors may not have the experience to know what quality help looks like or what it takes to produce a quality book.It is difficult to get mainstream reviews, media attention or sales through conventional channels (bookstores, libraries).

When to prefer DIY over assisted

You intend to publish many books and make money via sales over a long period.You are invested in marketing, promotion, platform building, and developing an audience for your books over many years.

Social Publishing

What it is

Write, publish, and distribute work in a public or semi-public forum, directly for readers.Publication is self-directed and continues on an at-will and almost always nonexclusive basis.Emphasis is on feedback and growth; sales or income can be rare.

Value for author

Allows writers to develop an audience for their work early on, even while learning how to write.Popular writers at community sites may go on to traditional book deals.

Most distinctive categories

Serialization: Readers consume content in chunks or installments and offer feedback that may help writers to revise. Establishes a fan base, or a direct connection to readers. Serialization may be used as a marketing tool for completed works. Examples: Wattpad, Tapas, LeanPub.Fan fiction: Similar to serialization, only the work is based on other authors’ books and characters. For this reason, it can be difficult to monetize fan fiction since it may constitute copyright infringement. Examples: Fanfiction.net, Archive Of Our Own, Wattpad.Social media and blogs: Both new and established authors alike use their blog and/or social media accounts to share their work and establish a readership. Examples: Instagram (Instapoets), Tumblr, Facebook (groups especially), YouTube.Patreon/patronage: Similar to a serialization model, except patrons pay a recurring amount to have access to content. Popular platforms include Patreon and Substack.

Special cases

Amazon Publishing

With more than a dozen imprints, Amazon has a sizable publishing operation (1,000+ titles per year) that is mainly approachable only by agents. Amazon titles are sold primarily on Amazon, since most bookstores are unwilling to carry their titles.

Digital-only or digital-first

All publishers, regardless of size, sometimes operate digital-only or digital-first imprints that offer no advance and little or no print retail distribution. Sometimes such efforts are indistinguishable from self-publishing.

For more information on getting published

Start Here: How to Get Your Book Published (traditional publishing)Start Here: How to Self-Publish Your BookHow to Evaluate Small PressesA Definition of Hybrid PublishingShould You Traditionally Publish or Self-Publish?

Earlier versions of the chart

Click to view or download earlier versions.

2019–2020 Key Book Publishing Paths2018 Key Book Publishing Paths2017 Key Book Publishing Paths2016 Key Book Publishing PathsThe Key Book Publishing Paths (2015)4 Key Book Publishing Paths (late 2013)5 Key Book Publishing Paths (early 2013)

December 29, 2020

Writing With Sharpness: Q&A with Elinor Lipman

In this interview, author Elinor Lipman discusses writing effective humor and non-dialoguey dialogue, how she gets readers to see her characters without describing their looks, rejection, and the book that became a Helen Hunt movie.

Elinor Lipman (@ElinorLipman) was born in Massachusetts and is the author of more than a dozen novels. Her first one, Then She Found Me, was published in 1990 and was adapted into a film starring Helen Hunt, Bette Midler, and Colin Firth. She won the New England Book Award in 2001, and her novel My Latest Grievance won the Paterson Fiction Prize.

She lives in Manhattan, as well as in upstate New York.

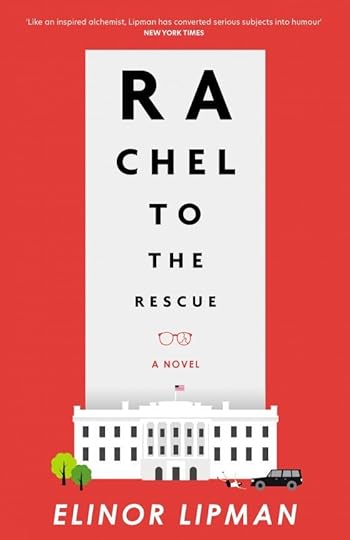

KRISTEN TSETSI: In 1981, your first published story (possibly the first short story you wrote?) appeared in Yankee Magazine, and then your first collection of stories published six years later, followed by the publication of your first novel three years after that (a novel that would later be optioned and, much later, adapted to film). Until Rachel to the Rescue, you’ve said, not a single book of the fourteen (I apologize if I missed any) you’d written had been flat rejected by publishers. (More on that later.)

print / ebook

print / ebookThere’s something about what you have to say and how you say it that clearly connects not only with readers, but also with the people who judge what readers want and what’s marketable. What do you think it is about your writing that appeals to people so broadly?

ELINOR LIPMAN: My first published story, “Catering,” wasn’t my first story; I think it was my fifth or sixth. Rachel to the Rescue is my 13th novel/16th book. As to their appeal—I often hear that they offer comfort by being funny but not brittle-funny; warm-funny. I do believe in happy endings—I mean, if I’m the god of this world, why would I make my characters suffer?

What changes in the publishing industry, if any, have been apparent to you since you began publishing, and how, if at all, have you had to adapt as an author?

Ebooks, audio books, social media. Even email didn’t exist when I was first writing books. I’ve had to adapt by getting myself onto those platforms, and I wouldn’t mind if they all disappeared. I’m always trying to gauge how much me-me-me my followers can tolerate. I grew up with a father who often said, “Self-praise is no praise at all.”

You say on your website that you only endorse books you genuinely love. What does any book that comes into your life need to have or be in order for you to love it?

I love wry writing, a gripping story, sympathetic characters, intelligence, no clichéd language, no reaches for poetic descriptions that feel self-conscious. I like wacky but believable. I love Steve McCauley, Maria Semple, Tom Perrotta, Mameve Medwed. The late Carol Shields was a huge favorite.

On the art of writing humor, you’ve said, “I’m not consciously trying to make jokes. If I sense I’m making a joke per se, then out it goes.”

It can be hard to not be trapped by moments of wanting a character to say something funny, writing the quippy dialogue, and believing it should stay in the story because it made you, the writer, laugh. How do you recognize when you’re telling a joke for the joke’s sake rather than creating organic humor, and how do you stop doing that?

I don’t try to make jokes, so it’s hard to answer the when and how of that. I’d say that what I always try to find is the better, stronger word, and often that word or phrase makes people smile. Henry James called the opposite of that “weak specification.” I rewrite and polish, then polish some more, trying to sharpen the sentences. I think it’s the sharpness that makes people laugh.

I don’t laugh when I’m writing and am usually surprised at what people find funny. I once looked up at a reading and asked the audience what was funny about that particular sentence they’d just laughed at. Someone answered, “We identified with it. It was a laugh of familiarity, which makes it a comedy of manners.”

I just read a novel (truth be told, didn’t finish it) where every character spoke with what I consider a West-Wing (i.e. dialogue by Aaron Sorkin), too-quick wit that came fast, that was wise-cracking in such a way that I thought, No one speaks like that every time, let alone every character one encounters. It seemed funny in a brittle way that said “This is dialogue” more than “This is two people talking in real life.”

Rachel to the Rescue incorporates a good amount of dialogue between Rachel and her parents in its early pages. Through their distinct ways of speaking to each other, their conversation introduces readers to the family dynamic, the parents’ personalities, and tucked inside all of it are some background details of Rachel’s life.

Many Amazon reviews about your novels praise your use of dialogue, and as a reader, I love a lot of good dialogue. But as a writer, what makes you enjoy writing it, and what dialogue-writing tips can you offer writers who might struggle not only with writing it, but also with how best to use it?

Dialogue is the easiest thing for me to write. I have to remind myself to let the characters pause, to take a sip of water, to notice their surroundings. An editor once wrote in the margin of a page, next to a long exchange, “Could someone here please pass the potatoes?”

I might not always succeed, but I try to give the dialogue the feel, the timing, the pacing of real-life conversation: the hesitations and the physical gestures. Also, I try to get into the scene as late as possible and leave it as early as possible, eliminating the hello-how-are-yous.

And third piece of advice—watch out for direct address when two people are talking. Newer writers often have their characters saying things like, “Well, Mary Jane, would you like to watch the news?” (In real life, it’s rare to use direct address in casual conversation.) Don’t worry about the “he-saids” and the “she-saids.” You don’t have to think up new attributions, because the readers’ eye skips over those, anyway. They become invisible.

And lastly, do NOT plant information in dialogue; i.e., do not have a character say over dinner, “I very much like the new sales job I recently started at a car dealership in Fair Lawn, New Jersey.”

Your description of your mother in your essay collection I Can’t Complain: (All Too) Personal Essays is captivating for its tiny, mundane, fascinatingly unique details that individualize the person who was your mother.

“She gave birth to me, the second child, at forty-one. My birth certificate lists ‘mother’s age’ as thirty-four, and it wasn’t a clerical error. […] Her bed slippers were mules, and her French twist required hairpins. […] …she didn’t like drinking water out of mugs.”

These are the same kinds of observations that lend authenticity to fictional characters. How do you select your details?

Your question made me smile. Nonfiction is one thing, such as those details above, but I have to push myself to describe things in fiction. I let the reader imagine what the character looks like—and they do.

print / ebook

print / ebookI give the minimum description, maybe one or two things that help the reader see the character and the place. In The Pursuit of Alice Thrift, I gave a male nurse in the neonatal unit a toy koala bear clinging to his stethoscope and mentioned that his cheeks were acne-scarred. Interestingly, reviewers almost always described him as handsome, which was their take-away from what I saw as his goodness. In Good Riddance, I gave the male love interest braces and described his living room with no more than its couch.

When I’d finished my first novel, Then She Found Me, my agent said about my narrator, “If I wanted to buy her a present, I wouldn’t know what to get her.” That said it all, and guides me: What’s in her room? What does she wear or how does she adorn herself? Give the reader that much.

But I dislike long passages about the weather, the sky, the flowers. To quote the late, great Elmore Leonard, “I try to leave out the parts that people skip.”

In 2003, five years before Then She Found Me would release as a movie starring Helen Hunt, Bette Midler, Colin Firth, and Matthew Broderick, your novel had already been in adaptation limbo after having been optioned many years before. “My son was in first grade when Then She Found Me was optioned and then bought by Sigourney Weaver. He’ll graduate from Columbia next year,” you said at the time.

I’m curious to know more about this experience. Before it was first optioned, had you hoped for movie adaptations of your work? And once the 19-year wait was over and the movie was being made, what was that like? I don’t mean your feelings about how loyal the screenplay was or wasn’t to the novel, which you addressed in the Huffington Post, but purely the experience of the adaptation taking place. Had it been such a long, slow process that it was anticlimactic, or did the reality live up to whatever you might have imagined? And what did you imagine?

Six questions! I’ll be brief. (Plus I wrote about the movie experience in my essay collection.)

I hadn’t hoped or known that manuscripts were circulated to producers, so that was a big surprise. There was the long dry spell when I gave up hope of it ever being made. Once I realized that it had gone into Helen Hunt’s hands (clued in by an email my son, then graduated from college and working at the Wm. Morris Agency, saw), it moved along.

I heard about the casting. I corresponded with Helen and met her; I visited the set and went to the premiere. I didn’t mind that the movie departed from the book because I loved the movie. I’d been advised by Meg Wolitzer, when the manuscript was first optioned, to think of it “as a movie based on a character suggested by the novel.” It was excellent advice.

In an essay titled “My Book the Movie” (published in the collection I Can’t Complain), you wrote:

Decades ago, on an unseasonably cold and rainy May morning, my phone rang, and it was Hollywood calling. “How would you feel on this miserable day to know that Sigourney Weaver loves your book?” this agent asked. She was talking about my first novel, Then She Found Me, and even though I surely knew that books could be turned into movies, I had no idea that mine had been circulated to producers. My husband and I threw an impromptu party to which I wore, aiming for Hollywood-tinged irony, a strapless dress, a rhinestone bracelet, and sunglasses.

I think many authors fantasize that having a book adapted to screen would mean a substantial increase in that book’s sales due to new, or renewed, interest in the novel. How did the movie impact sales of not only Then She Found Me, but your larger body of work?

print / ebook

print / ebookThe movie-tie in edition of Then She Found Me did hit the NY Times bestseller list, but not even in the top 20 (the part you don’t see in the newspaper).

Has it helped sales in other books? I never ask about sales. It’s a matter of “know thyself.” I don’t want to be depressed hearing a number that will disappoint. And if there is good sales news, you get it, something like “going back to press.”

My goal is to do well enough that my publisher wants to publish my next book. I don’t need to know numbers. (One exception: the publisher of Vintage wrote me a real letter on paper when sales of the paperback The Inn at Lake Devine went over 100,000. I didn’t mind hearing that at all.

You say in an interview on author Caroline Leavitt’s blog that Rachel to the Rescue was the first book rejection you’d faced. Publishers loved it, but they were worried it wasn’t the right time for something that pokes fun at Trump; they feared Trump fatigue.

As lovely and positive as the rejections were, however, they were still rejections. What was that first-time experience like for you?

It was terrible. Each rejection was a kick in the gut. But I didn’t give up.

You went on to publish Rachel to the Rescue with independent UK publisher Eye Books, which prides itself on working with authors, allowing them to be part of the conversation when it comes to cover art, pricing, and marketing and promotion.

How would you compare that relationship and overall publishing experience to relationships and experiences you’ve had with past publishers (which include divisions of Viking, Houghton Mifflin, Simon & Schuster, and Random House)?

Another question requiring 1000 words!

Because I’ve always had terrific editors, who bought my books because they loved them, I’ve enjoyed almost every step along the way. I’d still be with my first editor (and the next one and the next one) if they hadn’t moved on.

The different and most fun part of bringing out books with my British publisher is that one person can make almost all the decisions. It was fast and painless getting Rachel out. As fast as it was, my involvement in the editorial end of it was about the same as big publishers, except I turned around the edits based on the U.K. editor’s notes and suggestions. The cover artist, Ifan Bates, who’d done the UK covers for Good Riddance and On Turpentine Lane, is so quick and so good that I loved and said YES! to his first renditions for every one of those books.

I’m more involved with promotion of Rachel to the Rescue than any other book, by far, because I wanted it to have a life over here and saw myself as the U.S. vehicle for big-mouthing it. I made the decision for the first time ever to hire a publicist to help reach readers and bloggers, the very thing that publicity departments did for my U.S.-published book. I’m very glad I did.

Thank you, Elinor.

December 28, 2020

How I Landed a Book Deal Via Twitter—Unintentionally

Today’s guest post is by author Pam Mandel (@nerdseyeview).

Pitching a manuscript isn’t for cowards, the thin skinned, or those with no endurance. Believing your project is worthy, truly believing in it, is required, as is the patient of a saint.

75 rejections taught me this.

I have a spreadsheet listing every agent I contacted. It includes the date I pitched, a follow up date, their proposal requirements (they were not all the same), an expiration date, and some additional notes, if relevant. It is 75 rows long.

Every line is marked in red, indicating a rejection, either directly via email or indirectly via silence.

print / ebook

print / ebookMy memoir, The Same River Twice, published on November 3, 2020—on Election Day, during a pandemic, by Skyhorse, distributed by Simon & Schuster.

I sold it without an agent.

“Your following is too small.”

Shortly before my book’s release date, I had a call with my press publicist. She asked if I was on social media.

I started to laugh. I’ve been active online for nearly 20 years. “Yes, I have a blog,” I said. “I’m on Twitter and Facebook, I am on Instagram, I even have an IG for my dog.”

“Great,” my publicist said, “Many of our authors aren’t even on social.”

Yet the rejections often said my following was too small. “Apparently, you can’t sell a memoir unless you have Kardashian level followers,” one writer friend joked.

I’ve been on social for twenty years now, and while my following isn’t huge, it’s tightly targeted, plus it’s organic. I didn’t buy followers or join Instagram pods or go crazy with the hashtags. I followed people I liked conversing with or who posted interesting things. Sometimes they followed me back.

Among those followers was the acquisitions editor who later sent me my book contract.

Proposal procrastination

I finished my manuscript in the winter of 2018. Well, first draft finished. Pitch ready finished. Not final edit finished.

I followed by spending several months not writing a book proposal, really committing to telling myself I couldn’t do it. Instead, I talked to my published friends, shared my manuscript with a handful of beta readers, and tried not to fuss with the pages I’d written. I worked on other freelance projects, paid my bill, and continued to not write a book proposal.

In spring, 2019, I decided it was time. I cracked open Jane’s guide to writing proposals and… I wrote a proposal. Honestly, I felt a bit of an idiot for putting it off for so long. A few things were more difficult than others: the chapter synopsis and the marketing plan come to mind, but the entire project took me no more than a week.

Without knowing what parts of the proposal agents would want, I made myself write all the components. This tactic came in handy when I started pitching. Agents don’t, it turns out, all want the same things. But because I’d written each chunk, it was easy for me to snap the bits together like Lego when it came to customizing the proposal for each pitch. Chapter summary? Got that. Comps? Got that too. I used every piece, though not for every proposal.

Show your work

Next up, the research. Finding out who to pitch.

I headed to Twitter to talk about my project. This was helpful because several writer friends offered to introduce me to their agents. That was so kind and so welcome, and even the rejections were useful. Personal introductions came with more personal rejections.

Those personal rejections were how I learned my social following was too small, or that maybe I’d have better luck pitching the story as fiction, or, more commonly, travel memoir is just such a hard sell right now. (Oh, 2019, you had no idea, did you?)

Weekly I researched agents, read the submission guidelines in exhaustive detail, and sent customized submissions. The right number of chapters. A proposal with the right pieces. Just the proposal. Just the chapters. A less than detail oriented person by nature, I was meticulous about reading guidelines and sending in exactly what each agent had asked for.

Weekly, I posted my pitch score to Twitter. 10 pitches, 3 rejections, 7 no responses. 17 pitches, 9 rejections, 12 manuscript requests, 16 no responses. 49 pitches… you get the drill.

I pitched.

I posted my count to Twitter.

And I posted about the rejections. One agent called my book “gutsy” while another said it was clear I had chops at the keyboard. One agent sat on my book for months, and would occasionally email me to say she loved the book and was conflicted about if it would sell. Others said a simple “not for me” or sent me a canned “best of luck” notice.

Those terse rejections were easy to take, easier than the rejections from agents who said they liked the book but just couldn’t see a way to bring it to market.

The rejections piled up. There were 75 in November 2019. I was tired and sad and demoralized. My next step was to quit pitching agents and try to get on an academic or smaller press after the holidays.

Then I got a tweet from an acquisitions editor. “I’ve seen your tweets about pitching a book. I’ve been following your work for a while; I’d like to see what you’ve got.”

I had all of it, of course. I’d done the work.

This process isn’t replicable. Or maybe it is.

Fast forward, we inked a deal, I signed, the book came out in November 2020. The editing process was great, I had a lot of say in the cover, and the early reviews have been complimentary.

But.

I didn’t have an educated negotiator on my side, so I didn’t know what to ask for. I was lucky to have friends who shared information with me about their contracts. I was able to make educated requests for minor changes to the terms—though I don’t know what I left on the table. I also don’t know if an agent would have been helpful in getting more publicity for the book once it appeared in the world.

Without an agent, I chose to trust my editor. I decided to believe he had my best interests in mind and would get me a deal that was, if not as generous as I wanted, certainly standard for a first memoirist of my status. Yes, I’d have liked a bigger advance, a bigger cut. Also, my book is now in bookstores. That’s thrilling.

While the way I found my press was unconventional, I followed all the rules of traditional process to get there—with one exception. It was the confessional nature of my process that clued this interested editor into the fact that I had a book I was trying to sell.

Also, it turns out my follower numbers weren’t too small at all. It’s not how many followers you have, writers, it’s who they are. Mine included the acquisitions editor who bought my book.

I figure my follower count is just right.

December 21, 2020

Using Book Promotion Newsletters to Increase Sales

Today’s guest post is by author and publisher Mike O’Mary (@Lit_Nuts).

I ran an indie press for seven years and published thirteen books, including three New York Times bestsellers, three Hoffer Book Award Winners, and a book that was optioned for a film. We averaged 6,000 copies sold of each title—including two titles that sold more than 20,000 copies each.

To put those numbers in perspective, I think a Big Five publisher would consider 5,000 copies sold to be “respectable,” and most small publishers would consider that to be a “home run.”

We achieved success without traditional distribution and on a shoestring budget. And one of the keys to our success was using newsletters and websites that promote books.

There are dozens of book promotion newsletters (more than 100 by some counts), and I used many of them as a publisher. In this blog post, I’ll tell you why authors should include book promotion newsletters in their marketing plans, and why I launched my own such newsletter, LitNuts, despite the crowded playing field.

The Book Promotion Newsletter Industry

You are probably familiar with some book promotion newsletters. Some of the more prominent ones are BookBub, Bargain Booksy and eReader News Today. And for every prominent newsletter, there are many other smaller ones like Book Basset, the Choosy BookWorm and the Frugal eReader.

Most of these newsletters follow a similar business model in that they are free to subscribers, and authors and publishers pay to have their books featured in the newsletter. The cost to have a book featured in one of these newsletters ranges from as low as $10 (even less in some cases) to several hundreds or even thousands of dollars (in the case of BookBub).

The newsletters are great for readers. In addition to being free, the newsletters mostly focus on bargains, and everybody loves a bargain.

The only problems from the reader’s perspective are (1) the focus on bargains means a limited universe—not every great book is $2.99 or less, and (2) uneven quality because the only requirement for most newsletters is payment—they are not looking at quality, which means there’s a more-than-middling possibility that the 99-cent self-published “bargain” ebook you just downloaded isn’t worth the time you spent to download it, let alone read it.

There are additional problems from the perspective of the author, including convoluted promotion “packages,” tiered pricing structures, and a maze of sometimes complicated order forms.

Submitting to Book Promotion Newsletters

Another thing that can be complicated from the author’s perspective is coordinating promotions. A lot of times, an author will plan (or “stack”) promotions with multiple newsletters in support of a sale—for example, putting the ebook edition of your book on sale for $2.99 (or even free) for a few days or a week. You can set up the promotions yourself with each newsletter, but be prepared to spend lots of hours at the computer filling out online order forms.

There are some economical services that will handle submission to multiple book promotion newsletters and websites if you are giving away free copies of an ebook:

Taranko1 on Fiverr: Will submit free ebooks to multiple promotion services for as little as $5.Book Marketing Tools: Will submit free ebooks to multiple services for $29.Author Marketing Club: No charge, but they don’t submit for you. Instead, they have consolidated the links, to take you directly to the order forms of multiple promotion services. You still have to submit the books yourself, but having all of the order forms in one place will save you time.

That said, when it comes to submitting books that are on sale for $0.99 or more, you’re pretty much on your own. Which is fine—you can do it! It just takes time. But I will tell you about a service that I recently came across called Book Rank, which has two options: (1) “We Build It” Promotion Services, in which they select the book promotion newsletters/websites for you, and (2) “Build Your Own” Promotional Services, in which you tell them which venues you want to use.

I’ve not used Book Rank, and the “We Build It” prices are not cheap. But the “Build Your Own” service looks pretty reasonable. It’s $50 plus 6.9% of the total cost of the sites you want to submit to. You can choose from 33 book promotion newsletters/sites, and your cost will be $50 + the total cost of doing a promotion with each newsletter/website + 6.9%. That’s not a bad deal. But you need to know which ones to use.

Which Book Promotion Newsletters to Use?

There’s a good list of book newsletter/promotion services on Reedsy and an even longer one on Kindlepreneur—but be careful. Many newsletters don’t generate enough sales to cover the cost of doing a promotion with them.

Here are a few that I recommend that are likely to generate at least enough sales to pay for the promotion.

Bargain Booksy: Definitely one of the better ones. Polished newsletter and website. Easy to use order form. $20-$95, depending on genre.Free Kindle Books & Tips: Straightforward newsletter run by Michael Gallagher. $25-$100. Links to Amazon only.Hot Zippy: Umbrella for four newsletters. Well-established husband-wife operation. $24 and up, depending on service. Amazon only.Book Basset: From the website: “I hand-pick the best freebies available on Amazon.com. I pepper those freebies with a few stories about my anything-but-ordinary life, my kids, my cat and dog, and of course, my chickens and my bees.” Feature your book for $24+.eReader News Today: The longest running daily ebook newsletter in the industry. $40-$130, depending on genre and price.Choosy Bookworm: Multiple advertising options clearly presented, from $20-$100.Kindle Nation Daily: Can generate sales, but has some of the most convoluted (and expensive!) promotion options. If you use KND, go for one of the lower-priced promotions.

And then, of course, there’s BookBub. BookBub is expensive, but it gets results. The catch is that you have to apply to be featured in their newsletter—and they are very selective. They only accept 10-15% of the books that are submitted to them. Some of that has to do with price; BookBub requires that your book must be discounted to at least 50% off the predominant recent price and your book cannot have been offered for a better price in the recent past. In other words, you essentially need to price your book at the lowest price in its history to have it included in BookBub.

BookBub looks at everything else, too: book cover, professional reviews, online reader reviews, awards, etc. BookBub doesn’t give a number, but I tell people you’d better have at least 25 reader reviews averaging 4 stars or more on Amazon or Goodreads before submitting to BookBub (some say 50 reader reviews averaging 4.5 stars).

If you think your book will qualify, submit it to BookBub. Prices range from $113 (to promote a free ebook to a very small audience) to as much as $4,000 (to promote an ebook that costs more than $3 to a large audience). The average price to promote a 99-cent ebook is currently $600. That’s a lot—but you will sell hundreds, if not thousands, of ebooks as a result of doing a promotion with BookBub.

A Different Approach

I decided to create my own book promotion newsletter, LitNuts, with several improvements in mind. One is that we don’t solicit or accept book promotions from the Big Five publishers or their ~250 imprints. Our focus is on quality indie books from authors and small publishers. No other newsletter has this focus.

We also go beyond bargains and bring readers more choices. So while we have plenty of deals, we also feature books across a range of price points, including many new releases and award winners, as well as collections of short stories, essays and poetry—forms of writing that most newsletters exclude simply because collections don’t usually sell as well as book-length works.

Finally, we’ve made things easier for authors and publishers: no convoluted “packages” to analyze, no tiered pricing, just a simple order form and a flat price for all book promotions.

LitNuts also focuses on quality. An unprofessional cover or a sloppy description will get you a quick refund. We also take into account reviews (professional and reader reviews), ratings, and awards/recognition.

Parting advice

Book promotion newsletters are a dynamic component of the overall book industry and should be part of any marketing plan. But as with all things, proceed with caution. Readers need to be wary of the disproportionate focus on “bargains” that may not be bargains at all, and authors need to do their homework on which newsletters actually get results and which ones are just taking your money.

Ideally, the book promotions will generate enough sales to at least pay for themselves. But even if an author just breaks even on a promotion, you can regard that as a “win.” You got your book into the hands of more readers, which should lead to more online reader reviews (worth their weight in gold) and more word-of-mouth marketing (the Holy Grail of book publishing).

Note from Jane: Through Jan. 31, 2021, authors can do a LitNuts book promotion for only $5 with discount code BookPromo5.

December 16, 2020

Is Your Writer’s Block Really Writer’s Indecision?

Photo credit: snigl3t on Visualhunt.com / CC BY

Photo credit: snigl3t on Visualhunt.com / CC BYToday’s guest post is by writer and creative writing tutor Louise Tondeur (@louisetondeur), author of The Small Steps Guides.

While I was planning my current novel and annotating that plan, I asked myself a series of questions in the annotations. I know I’m not the only one to make notes on a draft in the form of questions, but until recently I wasn’t aware that I was creating problems for myself by not categorizing the questions. (I’m taking part in a coaching program for writers called Dream Author, run by bestselling crime writer Sophie Hannah, and this realization came to me as a result of one of the exercises we did.)

Some questions have to be answered before I can make any progress with a draft. But others are simply the result of indecision; I could simply make up my mind and move on, knowing I can always change my mind later.

Now I am convinced that two things can hold me back (for years on some projects) and they are:

not knowing the answers to crucial questions, andnot knowing which questions were which in the first place.

What types of questions are there?

Here are the types of questions I found when examining my current novel. You might have other categories of question when you make notes on your work. (I would love to know what they are! Please leave a comment.) Of course, many of these questions could fall into more than one category—a kind of overlapping Venn diagram of questions if you like.

Crucial questions

These are the most important questions to identify and could be what’s holding you back, especially if you don’t know about them yet. Here’s an example from my work in progress: When do the police start to treat the death as suspicious?

Unless I can answer this, I can’t make progress. This question is like a wall I can’t get over without a ladder. If you are similarly stuck with your manuscript, attempt to identify these unanswered crucial questions.

Artificial questions

These are written as authentic questions, but they hide the actual question and are hard to spot.

Example: When does Character B tell Character A what happened?

This later became: Should I use two viewpoint characters instead?

Consistency questions

This is when I forget how I organized or described something or someone earlier. These are easy to sort out using an old-fashioned read-through with a colored pen or your word processor’s “find and replace” function.

Example: Weren’t his eyes blue earlier?

These questions shouldn’t hold you back because you can sort it out in the revision.

Decisions disguised as questions

With this kind of question, I know what I want in my head, but I’ve still phrased it as a question—maybe because I don’t want to make the effort it would necessitate.

Example: Should I use Character B’s point of view in this scene?

This translates into: I want to write some scenes from Character B’s point of view so I need to look again at my plan with this in mind, but it’s going to take me several days and I’d rather avoid it.

Masks for indecision

These are questions I could easily answer, and I don’t need any further information to do so. I simply have to make up my mind.

Example: Where shall I set this scene?

The answer to such questions is always: Just decide already!

Problem questions

These are usually about the plot or structure, and you need to give yourself permission to answer these. Write down every idea you have, however wacky. If you like, you can deliberately ask your brain to come up with the answer and mull it over for a while, then make copious notes.

Example: How could character C feasibly gain entry to Character A’s house after dark?

Process questions

These could be described as “meta” or “contextual” and have to do with the writing process.

Example: Should I be planning the novel in this way? Or Should I plan this scene in more detail?

Often process questions can be negative, translating to: I shouldn’t be doing it like this! Sometimes they are positive: Maybe I should try it like this?

Research questions (two types)

Most fiction writers are familiar with research questions that come up while writing.

Example: What’s the name of the main shopping street in High Wycombe? Or: Is this the procedure the police would follow to investigate this crime?

Right there, we have examples of two very different types of research questions: those you can move on without answering (what’s the name of the street?) and those you can’t move on without answering (how would police investigate?). If you can move on without knowing the answer—because you can easily change the information later—no problem. But for some questions you must know the answer because it’s crucial to the plot line or story development.

Technique questions

These questions often relate to how you’re writing each chapter or scene.

Example: Should I write this in first person? Shall I put this in the present tense?

With these, unless you need to seek information or guidance, it’s often best just to decide and change your mind later if you need to, although it does take a long time to change from first person to third and back, as I discovered when I wrote my last book!

How to resolve your questions or indecision

You don’t need me to tell you that there are a lot of things that can get in the way of the writing process. But what we think of as writer’s block can often be “circumstances,” in that we have limited quiet time and space in which to focus, or that our mental load—what we carry around in our heads—is too much. Be kind to yourself if that’s true for you. But don’t let writer’s indecision disguise itself as writer’s block.

First, keep a list of your questions all in one place so it is easy to refer back to and amend. I keep mine in a notebook or folder and then type them up, mainly because my handwriting is messy.

I divide questions into three main types:

Those I definitely need to answer before I can make any more progress. This might be to do with the setting, or it may be a crucial structural or plotting decision. Prioritize these questions.Those I possibly need to answer before I can make any more progress. Mindset is everything here. If you feel these are holding you back, answer them.Those I definitely do not need to answer before I can make any more progress. Did you make his eyes blue in chapter 3 and green in chapter 17? Maybe. Make a note to check. You can keep writing.

It helps to write down why you haven’t already answered a question, but it should be fairly straightforward (although not necessarily comfortable if you are a procrastinator) to tell the difference. Once you have identified whether you are being indecisive or whether you lack certain information or guidance, you can move on to the next step: What action do I need to take? Write down the decision you have made or what steps you must take to make the decision. For example, if you’ve decided to set your novel in X town, you can change your mind later if you want to. And you might need to phone your historian friend to help you better develop that book’s setting in the 1920s. Crucially, make a commitment to take that next step, whatever it is.

Let us know in the comments if this resonates with you and the kinds of questions you ask yourself as you plan and redraft. Happy writing!

December 14, 2020

How to Effectively Manage Multiple Narrators in Your Novel

Photo by Tim Gouw from Pexels

Photo by Tim Gouw from PexelsToday’s guest post is from author Ken Brosky (@KenBrosky).

I read a book recently that will remain unnamed. The book was entertaining, and at its core was a pretty darned good mystery with some fantastic twists that made the ending a payoff for the ages. I enjoyed it from start to finish.

But I just couldn’t shake some negative feelings about the narration. This particular book, you see, was entirely first-person narration (“I did this, I did that, I thought this,” etc.) with a crucial tweak: multiple narrators. This meant each chapter had a different character telling a different scene in the story. In this case of this book, all the narrators were suspects in a murder. And as the clues fell into place, it became clear that every one of the narrators was keeping secrets … and could ultimately be the murderer.

But here’s the thing that kept bugging me: all the narrators sounded pretty identical. They didn’t have enough flavor to distinguish themselves, so I found myself continually flipping back to the beginning of the chapter to ensure I was imagining the right person telling the story in my head. That lack of distinct “voice” caused the multiple narrators to mix together.

There’s nothing wrong with this book, just like there’s nothing wrong with using multiple narrators in a first-person story. But—and I think this is a big but—you need to ensure their voices are distinct. This isn’t easy. It requires a lot of practice. It requires an intricate understanding of narration. And it requires some serious background work.

1. Identify why you’re doing this

Why does your story need multiple first-person narrators? You gotta have a reason, Dear Writer. And it should be compelling. Are the narrators separated from each other? Do they come from drastically different backgrounds, thus ensuring every scene is interpreted differently? Are they working against each other or with each other? Keep in mind that your audience will need to mentally keep the narrators separate, which requires extra work. Reward your audience for actively reading!

2. Make sure the narrators’ voices are distinct

This is the most important step. The characters you choose to tell the story need to come out. Watch the incredible movie Knives Out. Think about how differently the narration would sound from the mouth of Inspector Blanc, compared to the snarky Ransom Drysdale, compared to the kind-hearted Marta Cabrera.

Everyone speaks a little differently—use this. For example, I say “ain’t” all the time at home, but not at work. I don’t have a huge vocabulary; I get by on a thesaurus way more than any professional writer should. On the other hand, my wife uses a lot more big words (she read a dictionary for fun once, so she’s got me beat there!). She’s a farmer, I’m a teacher. The way we would narrate midwifing a calf (which we’ve both done on our farm) would be drastically different. For example, I—the city slicker—would be much more grossed out by the various fluids on my hands and clothes … she would be much more professional in her narration given the fact that she grew up on a farm!

All of this does not mean simply using a few different slang words or lazily switching up how often narrators use contractions. First-person narration has to embody the character’s language and personality. The best way to explore this is to write dialogue. Let your narrators get together in a room and talk for awhile. What differences pop up? If you’ve developed your characters well enough, they should begin to distinguish themselves the more they talk. You should be able to take out all the dialogue tags and still know exactly who’s talking.

3. Come up with a killer plan

This is arguably the hardest part of the entire process. Every chapter needs a reason for existing with a specific narrator. As if planning out chapters wasn’t hard enough to begin with! Now, you have to make an even more crucial decision: who tells this part of the story? A single mistake here can come back to bite you during revisions, potentially throwing off the entire novel! So what do you do?

I have an idea I’ve used, and it’s an idea tried by other authors as well. It’s not going to make you happy, though. Ready? Are you sure? OK, here it is: write the chapter in third-person narration first. Get a sense for what happens in the scene, then think about which character in the scene will tell their version of what happened in the most compelling way. Imagine a dinner scene with all your narrators. Who’s got the most interesting perspective? The most important perspective? This kind of planning can go a long way.

Further reading

Sometimes, it’s good to learn from the best. Try these five super-distinct novels to get a better sense of how authors approach “voice” in first-person narration.

When No One Is Watching — Alyssa Cole wrote an awesome thriller about disappearances taking place in Brooklyn. Cole switches between two narrators: a black woman and a white man. Her writing is absolutely fantastic. Cloud Atlas — David Mitchell crafts a sci-fi epic that uses multiple narrators from different time periods. Beyond daring and innovative, taking obvious care to ensure the narration is distinct and realistic for its time period. The MaddAddam Trilogy — Margaret Atwood uses third and first-person narration. Read the entire trilogy to see how she utilizes both, and when she uses them to show unique perspectives! Getting Mother’s Body — Suzan-Lori Parks is a master storyteller. The unique voice of her narrator in this classic is a testament to her greatness. The Shadows — Alex North switches between third and first-person narration at crucial points. While it may feel jarring at first, this is becoming a more commonly accepted form of narration, so it’s worth studying from the best.

December 9, 2020

The End May Only Be the Beginning: Infusing New Life Into Your Fiction

Photo credit: Andrew_D_Hurley on Visualhunt / CC BY-SA

Photo credit: Andrew_D_Hurley on Visualhunt / CC BY-SAToday’s guest post is by editor and author Joe Ponepinto (@JoePonepinto).

As an editor who has worked at several literary journals, I’ve read thousands of fiction submissions over the past 15 years, so many that the endings—the climax and resolution—are too often predictable or uninspiring. Like many journal editors, when it comes to selecting work for publication, I’ll always choose stories that take me someplace new and unexplored.

How do you add intrigue and a sense of exploration to your fiction?

One way is to start at the end and move forward instead of back. That may sound counterintuitive, so let me describe how and why it works.

When reading from the submission queue I often get the feeling the writer has started by envisioning the climax or epiphany of the story and then worked backward to provide a well-grounded and logical path toward reaching it. There are several potential problems that arise from this approach. The most obvious ones are that the story fills up with background details and becomes tied to that logical and therefore predictable path. Such an approach mutes the story’s potential tension, and can turn the work into something more like an essay than creative writing, dependent on facts instead of narrative tension.

That may be when it’s time to ask what if and play with the story’s possibilities. What if the story started at the point of climax, with all that background and development already incorporated into the characters and their situations? Where would it go from there? What greater or more profound revelation might it achieve?

For starters, the characters would begin the story as fully-formed human beings, with motivations and goals, with pasts that readers can identify with through inference instead of exposition. It would also begin at a point of greater intrigue, challenging the reader to deduce how character traits and allusions to past events influence the characters’ decisions as they move forward. It would preclude much of the backstory that overwhelms many otherwise good works of fiction, and immerse the reader in an exploration of some deeper meaning, one in which readers can become willing participants. Working with this model also eliminates another problem I often see in the submission queue, that of the writer withholding evidence in an attempt to create a surprising reveal later on. Trust me, the surprise is never as satisfying as your reader expects.

Personally, when I write I often try to begin the story from a place at which another writer might choose to end. I may have little idea where the writing will take me, and that’s partly the point—if I am intrigued to find out where the narrative might go, the reader might be also. The idea is in line with Kurt Vonnegut’s famous advice to begin a story “as close to the end as possible.”