Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 72

May 4, 2021

When I Decided to Write My Own Story—And Not Someone Else’s

Photo by Mike from Pexels

Photo by Mike from PexelsToday’s post is an excerpt from the memoir Word for Word: A Writer’s Life by Laurie Lisle (@LiteraryLaurie).

The digital revolution was upending the publishing world, and I worried how authors, especially biographers like myself, would work in the future without the existence of handwritten letters, diaries, and other words on paper. Nevertheless, I pulled from the back of a file cabinet my abandoned book proposal about writers Neith Boyce and Hutchins Hapgood. As I read it again, my excitement returned about writing a literary biography; I still relished the intellectual adventure of investigating primary materials. Three decades after I wrote the proposal, the couple’s extensive papers, including their letters to each other, had been organized and indexed at the Beinecke library in New Haven.

I had been able to learn relatively little about Neith in the 1970s, before the days of personal computers and internet searches, when it would have taken years—long after a book contract was signed—to discover the details of her life. Two decades later, after digitized books and databases revolutionized research, I was able to read in a matter of months almost everything that had ever been published about the couple. Two books of excerpts of their work edited by feminist scholars had also been published. As I read, I discovered that Hutch resented Neith’s attention to writing and neglect of housework and the family. I also learned that while he had a number of affairs, when she did, too, he became tormented by the fear that they meant more to her than his flings did to him. When she fell in love, then reluctantly gave up her lover for the sake of the children, she suffered a nervous breakdown from which she never fully recovered. And in a collection of Eugene O’Neill’s letters, I was very dismayed to find a description of Neith lying on the floor in an alcoholic stupor “as always.”

After her last two books were published in 1923—the novel Proud Lady and Harry: A Portrait, a nonfiction account about her eldest son who died in the 1918 pandemic—she wrote and published very little. I was disturbed that a memoir, which she called an autobiography, was written in the third person, under a pseudonym; most appalling, it ended abruptly on her wedding day, as if she didn’t want to face what came afterward. When I was in my thirties, I had known about a few of Neith’s disappointments, but her failure to publish her autobiography and any novels after the age of fifty-one, when I had begun to write in a personally meaningful way, had not been as important to me then. I was no longer the same young woman in an unhappy marriage who had imagined that Neith and Hutch’s was a thrilling romantic relationship.

Instead of Neith’s being an inspiring life, I realized it was a cautionary tale for women writers, especially for those who want to become wives and mothers. It was the same conflict between career and children I had wrestled with, and which many young writers still valiantly struggle with today. As I learned the truth about Neith’s life, I developed the crise de confiance I had experienced in the middle of writing my biographies, when I was forced to reconsider my innocence or idealism about my subjects’ imperfections, but then I had contracts with publishers, and I was motivated to work my way through my disillusionment to degrees of understanding. It wasn’t long before I developed a sickening feeling in my stomach about the prospect of thinking about Neith’s tragic life every day for the next few years. I vacillated for a while, unwilling to undertake a pathography or give up the biography again.

When I talked about my dilemma with a friend, he remarked that at our ages we should not do anything without passion. Not just interest or pleasure, he emphasized, but passion. As my seventieth birthday approached, I found myself asking how many more writing years I had left, and I was startled to realize there were only twelve until I turned eighty. “Twelve precious, productive years, if I’m lucky. How to best spend these precious years?” I asked myself. Biology, and mortality, too, suddenly appeared as different kinds of deadlines. I remembered that Neith’s daughter, Miriam, had been in her mid-seventies when she worried aloud to me about whether she had enough time and energy remaining to publish some of her parents’ prose, and it turned out that she did not. By the time I finished writing another biography, I recognized that I would probably be her age, and there was something else I wanted to do.

Would there be enough time to write another biography and then a memoir? While a biographer’s time is finite, I knew very well that biographies often take more time than anticipated. I asked myself if I should search the forty-eight boxes of another family’s papers or read my forty handwritten journals. Spend my days researching in an archive in New Haven or working at home near my garden? One sunny spring day, while looking through a box of letters at the Beinecke library, I finally acknowledged that it wasn’t passion motivating me as much as curiosity and eagerness to get back to work. Maybe I would settle for meaningfulness, but I wasn’t finding enough of that either.

When writing my biographies of strong women while enduring the opposition of men I had married, I had kept working, in retrospect readying myself for telling my own story. I had begun, but was I ready to do more? When I asked myself if it would be presumptuous for me to write a memoir, I knew the question was an old one. In 1655 Margaret Cavendish, the English Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, a prolific writer and childless wife, had hoped readers would not think her “vain” for writing about herself; her memoir might not be important to them, she admitted, “but it is to the Authoress, because I write it for my own sake, not theirs.” Her defiant words reminded me that writing for oneself was often a writer’s motivation, but I hoped what I learned might be meaningful to others, too.

Finally, on a summer day I put the book proposal about Neith and Hutch back in the file cabinet with a mixture of regret and relief and went to look for my handwritten journals. I gathered them together, numbered them, and arranged them on a bookshelf—from the college spiral notebooks to the more recent hardback Moleskine volumes—and then opened the fragile first page of the 1963 journal. When I had read passages in the past at a crossroad or a time of confusion, it had made me feel skinless, so I had stopped. Now I vowed to ignore the feeling of vulnerability and to read every one of them, most for the first time since writing them.

As I read and remembered, searching for dialogues and descriptions, what had been lost in memory became alive again. Former emotions rushed back, and I was astonished to experience the exact same indignation or hopefulness or pain I had felt many years earlier. “How can that be?” I asked myself. “It was so long ago.” It was as if everything I had ever thought or felt remained imprinted deep in my memory. As I deciphered the handwriting on page after page during my decade in Manhattan, the erratic penmanship and outpouring of turbulent feelings enabled me to inhabit a younger self who had struggled for energy and exuberance while also looking for love and security as well as a way forward. At moments I applauded her daring or despaired at her hesitancy, gyrating from exhilaration about an insight to excruciating sadness about the loss of love. Some days I was afraid of what I would read next.

“When the fear is upon you, write for yourself,” Richard Rhodes had written, I recalled. “You and your fear, wrestling like Jacob and the angel.” I interpreted this angel—not at all like the angel of the house—to be a more honest and brave part of myself that refused to free me from its grip until I addressed it. It was the self who recognized my flaws, when I was thoughtless or insensitive or wrong. It was an especially fierce struggle when reading old letters and journal passages about boyfriends and husbands, when what they regarded as love didn’t feel like love to me at all. When reading a former husband’s letters, I felt sorry that I had met him and then sad that I had to leave him. One morning at my desk my throat tightened and I thought I was having a heart attack, but in the emergency room of Sharon Hospital a sedative dissipated my difficulty breathing. A doctor diagnosed stress, but I knew the feeling near my heart had been caused by a toxic brew of anger and grief. My violent reaction to what I was reading, I realized, meant that I was getting down to memories that mattered.

“Why am I doing this?” I asked myself some days. “Why am I remembering the past?” As I searched for answers, I recalled that even the extraordinary women I had written about had not risked remembering everything. Georgia O’Keeffe had said don’t look back. Was she right or wrong? Her few self-portraits—pinkish watercolors of female nudes with no distinguishing facial features—were evidently done because she needed a model, not because she wanted to reveal herself. Early on I had wanted to be like her, but as I got older and became more myself, I became more open. Was my urge to understand an act of recklessness or a matter of fearlessness? “Why not just try to enjoy myself like everyone else my age?” I asked myself another time. I hoped that examining my earlier years might excavate and expel something, but I wasn’t sure it would. At a panel discussion about memoir in Manhattan, none of the memoirists claimed that writing their books had given them catharsis, only a sense of creative satisfaction. At the end of captivity narratives, whether told by black slaves or white women abducted by Native Americans, there is often what is called the “telling,” a story of survival that results in recovery, so I continued, hoping for a sense of closure.

Bookshop • Amazon

Bookshop • AmazonAs I worked my way through fifty years of journals, trying to read a month a morning, I didn’t want the past to ruin the present. I resolved that remembering would be for weekday mornings, and afternoons and weekends would be for everything else. Remembering became less painful as I began writing and putting memories and other material into orderly sentences and paragraphs, then organized them into chapters, and the dynamism of composing took over. As this happened, it became easier to accept my mistakes, which I eventually decided were not more misguided than anyone else’s. And if I had not always acted wisely, I always had the resiliency to go on. Fortunately, there were moments of closure after all: one afternoon I removed two former wedding rings of mine from my bank safe-deposit box and took them to a jeweler, who placed them on a little gold scale and gave me a few dollars for them. While working on the memoir was depleting at moments, it was also deepening. At the fiftieth high school reunion of my day school in Providence, a childhood friend remarked on my aura of intensity; I wasn’t exactly sure what she meant, but I imagined it had something to do with writing the memoir.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, check out Laurie Lisle’s memoir Word for Word: A Writer’s Life.

April 29, 2021

What If It Takes 12 Years to Get an Agent?

“Sharpening pencils” by BWJones is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Sharpening pencils” by BWJones is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0Today’s post is by author Catherine Baab-Muguira (@CatBaabMuguira). Her book, Poe for Your Problems, releases in September 2021.

About a week before my nonfiction debut went to auction, I received two requests from editors who planned to bid if I did what they asked. The first editor wanted me to take my 4,000-word writing sample and rewrite it in a purely comedic vein. The second requested a rewrite, too, only he wanted me to make the book ultra-serious. No jokes.

It was 2019. I was childless, but I did have a demanding full-time job I couldn’t shirk, so I got up at 5 a.m. every morning and banged out new drafts before work. In the evenings, my friend Lizzie hunkered down beside me while, over beers and takeout, I walked her though the new material. Then we punched it up, or slathered on the sad. The adrenaline rush of all this was real, and also very far from pleasant. I felt like the comedy-tragedy mask come to unshowered, greasy life. If I didn’t satisfy both briefs, my book might not sell.

A dozen years prior, when I’d first started trying to get a book published, I wouldn’t have been up to the task. Fortunately, by the time all this went down, I’d already spent 12 years in the query trenches. I’d also spent a year in L.A. pitching movie ideas to producers in deep V-necks who absolutely loved the idea, wow, beautiful, brilliant, only change the entire thing, okay?

It’d been like a fitness boot camp for my ego: sadistic and deeply wrong, probably in violation of multiple health-department codes. In the end, though, I was glad to have survived, and the conflicting requests found me in shape. I’d already made pretty much every stupid, humiliating mistake you can make. Perhaps without all those years of unanswered emails, form rejections, close calls and ghostings, I would’ve been tempted to be like but but but! How dare you question my Art!

Instead, my feeling was: Thank you for the suggestions. Hand me that brief. Lemme see what I can do for you.

This kind of compromise isn’t for everyone, I realize. Depending on your ambitions, your age, where you are in your writing career and/or the happiness of your childhood, you may be on a different path. My goal was getting my book’s big idea out into the world, whatever form it took, whether comic or tragic. And for me, in the most literal way, humor triumphed over depression. Running Press, a subsidiary of Hachette, bid on the funny version and won.

I want to say I learned a lot in my years of querying and perhaps most especially in those last few hysterical days before auction—as Nabokov wrote, “The last long lap is the hardest.” But I also know it’s all too easy to recast the struggle as edifying and educational when you find yourself, for however brief a moment, lifted out of it. Who’s to say the self-congratulation phase is not, in its way, just as blind as what came before?

Putting it mildly, the world demands different dues from different people. We don’t all have the same access, resources or, for that matter, masochistic streak, dark sense of humor, what have you. I do, however, feel comfortable presuming that your experience of querying has been horrible and painful, too. Disheartening. A mashup of Cinderella and The Road.

You may take heart in hearing that you are almost certainly savvier than I was when I sent my first queries in 2006, when I was 24, and it turned out no one wanted the bildungsroman I’d written hoping to sway an indifferent ex. I queried two more novels off and on over the next 10 years before starting work on a nonfiction proposal in late 2016. It was 2018 when I signed with an agent.

Here’s what I came to see in my dozen years of disappointment. Maybe this hard-won knowledge can help you, too, wherever you are in your—the word is hard to dodge—journey.

Lottery truisms apply. You can’t win if you don’t query, yet the odds are grim.It can be better to think of querying as a process rather than a matter of sending an email, or even a whole season of sending emails. Finding the right agent may take years and years even if you’re 99.8% less naïve and deluded than I was when I started out.Literary agents aren’t therapists or fairy godmothers. They’re more like realtors searching for developed properties who, several hundred times a year, find themselves the target of strangers’ bizarre emotional entreaties. People target agents, in short, with some very weird stuff. This is what explains their occasional caginess, overall reticence and long response times. The major obstacle standing between many (perhaps most) writers and a book deal isn’t a polished manuscript or proposal. It’s a sense of the publishing landscape as it really is. It’s market information, market know-how: a considered view of where the opportunities lie, of how to pitch and market successfully.Writing and marketing are distinct skill sets. Busting out of the bull pen tends to require that you develop both and then wrestle them into overlap.Yes, yes, I know: Some people will see the word “marketing” and equate it to insincerity. But some of history’s greatest and most recognized writers also spent years studying and adapting to the market, adjusting their original visions so that they more closely resembled popular literature and what was in demand. Edgar Allan Poe, by way of example, shifted his lofty and high-minded vision considerably downward to crank out such pop hits as “The Raven” and “Annabel Lee.” Now those are the works we all remember. Dickens and Shakespeare wrote expressly for their markets, too.

Of course, nonfiction and fiction may be marketed and sold very differently. With nonfiction, it can be easier to make an objective case for who will buy a book, while fiction—you will hear again and again—is more subjective. As a novel-querying friend of mine said, after I told her I was writing this piece, “When your No. 1 response is ‘This industry is very subjective,’ you’re not running an industry. You’re running a sorority.” And she’s right. It’s distressing how often it’s the case in book publishing, as in so many other areas of life, that cultural capital, cache and opportunities just keep accruing to those who can already boast of a boatload.

Still, this is our task in trying to sell our work, no matter what that work is. We have to try to take the subjectivity out of it to the greatest possible extent, which means seeing our own market positions as clearly as we can, and trying to put numbers and data to our business cases in the form of platform, market research, and comps—in addition to developing a unique premise and an appealing presentation of your connection to your material, et cetera. It may mean acting on feedback, too, if that’s something you’re open to.

With querying, it’s almost as though you’re working a long, sometimes-awful, unpaid internship. You’re discovering how to think like a salesperson, learning to address objections, assembling a compelling commercial vision in real time as you rack up the rejections. In short, you’re preparing to move to the next level and face the final boss, so what would be the point of complaining? (I mean beyond the amazing #amquerying gallows humor on Twitter.)

The truth is that no one is ever going to care about your book as much as you do, which is the major reason you’re qualified to do not just the writing but the selling. Then there’s the fact that we’re all simply stuck with the task, anyway, so may as well get cracking. Who knows? You may scoop up, in the end, some valuable skills—in fact, the exact skills you’ll need to sell your book or next big project. The stamina, too. I can’t think it’s just a coincidence. Life itself is a tragicomic grind full of highs and lows, hard lessons and slow-boil jokes. And of the #amwriting, #amquerying life, that’s only more true.

April 27, 2021

3 Key Tactics for Crafting Powerful Scenes

Photo by Josh Hild from Pexels

Photo by Josh Hild from PexelsToday’s post is by regular contributor Susan DeFreitas (@manzanitafire), an award-winning author, editor, and book coach. She offers a first 50-page review on works in progress for novelists seeking direction on their next step toward publishing.

It’s one of the things we love most about fiction, the illusion that we’re not just reading a story about this character, we actually are this character.

Brain science tells us that when we read about a character doing or experiencing something, our brains light up in much the same way as if we were doing or experiencing that thing for ourselves—and nowhere is this illusion more complete than in scene.

Scene is where the pace of the story slows to “real time,” and we’re privy to every word, gesture, and sensory detail. Not only does this allow us to inhabit the story in a visceral way, it sends a clear message that what’s happening here is important—important enough that it cannot simply be narrated. Listen, the author is saying. You really just have to experience this for yourself.

Scene is also where the emotions of the story are at their most intense—the place where, to paraphrase Ursula K. Le Guin, the reader leans forward and bites her lip. Scene is the place in the story where we find tears welling up in our eyes, or find ourselves scowling at the antagonist’s unconscionable cruelty.

That’s because, no matter how much the author tells us about the characters, scene is where characters show us who they really are. And in doing so, they’re often unpredictable—which of course only adds to the appeal. When we read scenes where the characters surprise us, we want to keep reading, to see what wild thing they’re going to do next.

Powerful scenes make for powerful stories, and as both a writer and book coach, I’ve found that these are three key tactics for achieving them.

1. Dramatize turning pointsTo articulate means to give shape or expression to something, such as a theme or concept—it also means to unite by means of a joint. Maybe that’s why dramatizing the turning points of a story, its joints, is one of the strongest ways to give shape and expression to the story as a whole.

Situating scenes at the turning points of your story also ensures that something will actually occur in these scenes, beyond sharing the basic exposition, characterization, and conflicts. Which is to say, situating your scenes this way helps to ensure that there will be a major development within that scene that moves the story forward.

Often, writers have no real intentionality about where they place their scenes, or what work they’ll actually perform for the story. They write scenes to explore a situation or setting, to get a sense for the dynamics between the characters, to explore the conflicts between them—and there’s nothing wrong with that, especially in an early draft.

But powerhouse scenes are made of stronger stuff: they do all of this while also dramatizing the story’s major developments, and articulating its contours as a whole.

2. Employ reversalsScreenwriting guru Robert McKee holds that every scene must employ a reversal of some type, be it a reversal of power or a reversal of expectation.

A reversal of power is a scene in which one character holds more power than the other when the scene begins and that dynamic is reversed by the time the scene ends. A reversal of expectation is a scene in which the character goes in expecting one thing to happen but something else happens instead.

It’s easy to see how well this technique works by watching movies: Reversals keep us engaged by providing a regular shot of dopamine in the form of surprise, a sense that the story isn’t just going to settle down into ho-hum predictability.

It’s a technique that works just as well for fiction, and part of the power of this tactic, to my mind, is the help it affords the writer. How do you know when you’ve pushed the conflicts in your scene out far enough? When you’ve achieved some type of reversal.

3. Set it up, then step backYou’d think that, because scene is the place where the reader experiences the emotions of the story most viscerally it’s also the place to include a lot of information about what the POV character is feeling. But the opposite is actually true.

Remember, scene is the place where our brains most fully buy into the illusion that we’re not just reading the story, we’re living it. And nothing breaks that illusion more reliably than the author butting in to tell us what’s going on inside the character’s head.

Doing so is appropriate at times—necessary, even. But generally speaking, the best time to let the reader know what the character is feeling is not during the scene itself, but before that scene begins.

For instance, there’s a powerful scene in Midnight at the Bright Ideas Bookstore in which the protagonist sees the father she’s been estranged from for the first time in decades. As the character is driving to her father’s cabin, the author shares with us, for the first time, the extent of their conflicts when she was a teen, including a key detail: When she dared to push back on her father’s strict rules, he retaliated by removing her bedroom door.

Then we get the scene itself—a powerful scene, alert to the real-time nuances of dialogue, diction, tone, and body language as the protagonist and her father have their long-delayed reckoning. But the author doesn’t have to butt in to tell us why the character is so angry in this scene, how a certain line of the father’s denies the truth of his past behavior, or the way that makes her feel. We can feel all that for ourselves, because the author has given us the emotional context beforehand.

Scene is one of the most powerful tools in the writer’s toolbox. Placed intentionally, crafted well, and set up via emotional context and backstory, they may in fact be the most powerful tool of them all.

What’s a powerful scene from a novel you’ve read that stayed with you over time? And why do you think that scene had so much power?

April 20, 2021

How the Pandemic Is Affecting Book Publishing

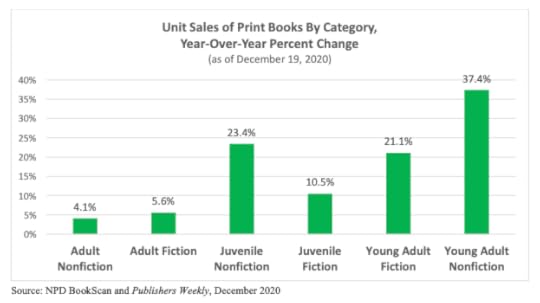

In a recent article at the New York Times, you’ll find a big-picture overview of what’s happening to US book sales as a result of the pandemic. Despite print sales being up around 8 percent overall—a record-breaking year—the NYT article paints a doom-and-gloom scenario, with considerable nail biting about the “profound impact on literary culture.”

Why so glum? Well, like other retail sectors, book sales have shifted online during the pandemic, which tends to favor older (backlist) titles and known favorites. Plus, some indie bookstores aren’t doing all that well with the transition to online sales.

Unfortunately, the New York Times frequently gets stuck on independent bookstores as the way for new talent and new titles to get discovered, even though they represent maybe 4-5 percent (optimistically) of overall book sales in the US. The chart below, from 2012, shows them at 3.7 percent after the Borders bankruptcy. Further, the New York Times tends to interview and quote people who dislike Amazon and are Very Concerned About Literary Culture.

According to a Publishers Weekly ongoing survey of bookstore owners across the country, some independent bookstores have been managing well during the pandemic, with one store reporting 50 percent more sales than in 2019. To be sure, not all stores are thriving, and a few have experienced serious declines—but in the end, declines have been less drastic than predicted. All stores saw a shift to online ordering and have had to meet the challenge of fulfilling such orders. According to US government estimates, bookstore sales were down by 30 percent in 2020 through the month of November.

What you won’t find the New York Times discussing: the fortunes of self-published authors (many of whom reported growing sales during the pandemic), or much critical exploration of why some new titles didn’t do so well in the US when others did perform well in the UK. The Bookseller reported (subscription required) in January 2021 that debut novelists performed better in 2020 than in 2019, by a whopping 151 percent! (There’s one very famous author in there with a debut, but even without his help, debuts did fine.)

I’ve been reporting on how the pandemic has shifted and shaped book sales over the past year, relying on reports from Bookscan, Nielsen (UK), the Association of American Publishers, Ingram, and Publishers Lunch—plus I attended countless online industry events. Here’s the context and meaning that you won’t find in the New York Times piece.

Yes, more book sales are happening onlineMore people are shopping online than ever before due to the pandemic, and consumer behavior hasn’t shown any sign of reverting to pre-pandemic routines. During two recent webinars hosted by Ingram Content (the largest US book distributor), marketing experts described a dramatic change in the consumer environment. The US has experienced 10 years of ecommerce growth in three months, with books, music, and video seeing some of the most dramatic shifts to online sales. This new environment makes it critical that publishers and authors adjust marketing and sales strategies and build new skill sets, as these changes are likely to become permanent. (Nielsen UK, too, is seeing “stickiness” in the consumer transition to online retailers.)

While Amazon is still the largest online retailer for books, they have in fact lost a small amount of market share in the US. Target and Walmart have performed well, and they even took away a small percentage of Amazon’s share in book sales (about 2.5 percent), according to Jess Johns, consumer insights manager at Ingram Content. This may come as a surprise, given the large increase in revenues that Amazon has reported, and it’s true that the pandemic has been very good to them. However, Peter McCarthy, director of consumer insights at Ingram Content, pointed out that the online retail marketplace has become more diverse during the pandemic, not less. People are willing to shop at many different types of stores; they pay attention to business and brand values as well as to the impact of their buying decisions on the community. Furthermore, consumers know they have power and are using it. “What we stand for as companies matters more to consumers than ever before,” McCarthy said; bookstores, publishers and authors are not exempt from that.

The shift to online sales has benefitted all publishers

Full-year financial reports from 2020 are now available from the Big Five publishers with the exception of Macmillan, which is privately held. A quick summary:

Penguin Random House increased sales by 4.6 percent and profits by 23.3 percent.HarperCollins increased sales by 7.9 percent and profits by 33.2 percent.Simon & Schuster increased sales by 10.7 percent and profits by 11 percent.Hachette increased sales by 3.9 percent. Its parent company, Lagardère, saw sales decline by .4 percent and profits increase by 11.8 percent.In the UK, print sales grew by about 5 percent.Michael Cader of Publishers Lunch has noted (subscription required) that children’s books account for a significant chunk of sales growth. He also credits publishers’ good performance to lower returns—20 percent lower than in 2019—which helps not only sales but profits. There are also increased ebook and digital audiobook sales for just about everyone.

Cader also recently pointed out that large publishers have been slowly losing market share due to the shift to online sales, which favors other publishers and self-published authors. He writes, “BookScan’s basket of ‘other publishers’ outside of the top 15 companies has been rising steadily year over year for some time now and would comprise their largest segment by far if you included the distribution clients who sell through Ingram Publisher Services, Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster, and others.”

Learn more about those smaller, independent publishers across the country that have performed better in 2020 than 2019.

What about Barnes & Noble?In a recent conversation at IBPA Publishing University, Barnes & Noble CEO James Daunt spoke about the effect of the pandemic on the chain’s performance and how its strategy is changing to give local booksellers more power over what they stock and merchandise. But what caught our attention is Daunt’s comment that the shift to online sales for Barnes & Noble has been “relatively minor.” Given how much e-commerce has grown in the last year (and Ingram’s many webinars pointing out that these behavior changes are here to stay), this seems worrisome, but apparently not for Daunt. “I don’t think the book you get in your mailbox delivers the same pleasure as the book you selected by interacting with a knowledgeable bookseller,” he said. Read more in Publishers Weekly.

The shift to online sales favors backlist titlesPeople today discover books through varied platforms and channels—retailers, libraries, social media, and subscription services—and that variety favors backlist sales. Backlist titles are older titles (usually more than one year old); their share of overall book sales in the US increased to 67 percent in 2020 from 63 percent in 2019. McCarthy said, “Online, things flatten out a lot” because there are no front-of-store displays, no face-out promotions, no end caps, and so on, which tend to feature new titles. Publishers and authors need to smartly respond by paying attention to a broader set of titles in their marketing, not just frontlist. McCarthy advised marketing relevant backlist alongside new releases. “An older book a consumer hasn’t seen is new to them, and that’s evident in the [sales] numbers.”

Recent research by the Panorama Project shows that the number-one way people discover books is word of mouth—that is, a recommendation by a friend. The second method? Whether the book is by a favorite author, reinforcing the truism that a strong author brand is vital. But an equally important message from Panorama’s research is that—despite these top two methods of discovering books—book discovery today is incredibly varied and involves different media, such as video games, TV, and movies, especially for Millennials.

It’s not all about the independent bookstore recommendation, and publishers who still rely on that set of influencers absolutely must rethink their approach.

Audio sales and subscription services continue to growAll formats have seen sales growth during the pandemic; readers like different formats and tend to read multiple formats. During the pandemic in particular, Ingram saw increased interest in subscription models and libraries, but those options did not have a negative impact on print sales, according to Johns. Rather, Ingram sees an increase in readership, which is increasing sales, not cannibalizing sales.

Digital subscription service Storytel recently released its 2020 annual report, showing that it exceeded its 2020 revenue goals, although the company is not yet profitable as a whole, only in specific markets. As of January 2021, it reported 1.5 million subscribers to its unlimited subscription model, which pays out to publishers and authors based on time consumption. It anticipates growing subscribership to 2.1 to 2.2 million people by the end of this year.

Kindle Unlimited also continues to grow—or so it’s assumed, given that payouts to indie authors continue to grow and Amazon doesn’t release any other figures that can be compared over time. Ebook distributor PublishDrive reported that it saw sales through subscription services double in 2020.

There’s also increased dealmaking during the pandemicDeal volume, which increased in 2020, continues to grow in 2021, according to reports at Publishers Marketplace, which has been tracking deals for more than 20 years. Total deals are up 19 percent over 2020, with gains across all categories. Nonfiction has seen jumps in memoir, religion/spirituality, and business; in fiction, debuts and women’s fiction/romance are doing well. Read more from Michael Cader (subscription required). See the comments of this post for additional detail.

How long can strong sales last?In 2021 so far, print unit sales are up about 30 percent versus last year, according to NPD BookScan.

Three consultants have written a free report on COVID’s anticipated impact on traditional and higher ed book publishing and related sectors in 2021. They anticipate consumer price sensitivity in the market, high demand for library ebook lending, continued analog-to-digital evolution, and a need for publishers to revisit and strengthen direct-to-consumer marketing.

The report concludes that “the seismic change is in digital,” and that “from now on publishers must treat bookselling as digital-first, physical-second, with no further questions asked.”

If you enjoyed this post, take a look at my paid newsletter, The Hot Sheet, which offers business intelligence for professional authors.

April 14, 2021

Which Comes First: Character or Plot?

Today’s post is adapted from the new book Writing the Novella by Sharon Oard Warner.

In college classes, bookstore readings, and writer’s conferences, someone always asks:

When I’m writing a _______ (story, novella, novel) which do I develop first, character or plot?

Sounds silly, in part because it echoes the chicken and egg conundrum. But the question is legitimate and deserving of a thoughtful answer.

In my experience, the inquiry comes most often from undergraduates working on short fiction. Here’s what I tell them: If the story is brief and the character captivating, that’s two-thirds of what the writer needs to keep the reader in her seat. (The other third is a compelling prose style.)

Because the ride is quick, short fiction readers are happy with a quick jaunt around the block in someone else’s car. But if you make it longer, a road trip, you are likely to be peppered with questions:

Where are we going?

How much of my time and attention will it take?

And, what will I gain from the experience?

Even if your protagonist is engaging and articulate, most readers won’t commit unless they’ve been sold on the trip itself. Reading a novella or a novel is an investment of sorts. And readers see it precisely that way.

So do writers, that is if they are looking at the bigger picture. Their investment is considerably larger than a reader’s. The time it takes to write and revise 100 pages is roughly ten times what it takes to write ten pages. The bigger the project, the higher the stakes, and if you are looking to publish your fiction, well, length makes it more challenging. I started as a short story writer, and my stories tended to be lengthy. As a rule, they ran 20-30 pages. More than once, I received a regretful rejection letter from an editor expressing his/her frustration at having to decide whether to publish my story (and make me happy) or two or three shorter pieces (and please those writers). Generally, I lost out.

Genre versus literary debateIf you have read your share of books on the craft of writing, you will be familiar with the assumption that writers of genre fiction are plot people, while writers of literary fiction are character creators. Graduate students are often dismissive when it comes to plot.

Here’s what I tell them: Whether you are writing horror or haute literary, your novella or novel needs both an engaging protagonist and a compelling plot. Don’t believe me? Maybe you’ll believe novelist John Irving:

What makes a novel “commercial” is that a lot of people buy it and finish it and then tell other people to read it; both “literary” novels and failed, messy novels can be commercially successful or unsuccessful. The part about the reader finishing the novel is important to the book’s commercial success; both good reviews and an author’s preexistent popularity can put a novel in the bestseller list, but what keeps a book on the list for a long time is that a lot of those first readers actually finish a book and tell their friends that they simply must read it. We don’t tell our friends that they simply must read a book that we are unable to finish.

Ask and answer this question. And answer honestly:

What compels you to finish a book; what keeps you reading to the very end?

It’s not just an interesting character, is it? It’s finding out what happens to that character.

Wait, you say. Who cares what happens to a forgettable character? An excellent question with an obvious answer—the forgettable character’s mother and no one else. That is, if the forgettable character has a mother, and she may not. One of the reasons characters end up being forgettable is that they lack a family history. Why? Because they arrive on the page without a background or a backstory. But more about that in a minute.

Planner versus pantserRead a few articles on writing book-length fiction in Writer’s Digest, Poets & Writers, and The Writer or browse the discussion boards for Nanowrimo (National Novel Writing Month), and you are bound to encounter the terms planner and pantser. These terms refer to two different approaches to writing a rough draft. Planners, well, they plan obviously, and pantsers make it up (by the seat of their pants) as they go along.

I don’t know who came up with these terms, but they are cringe-worthy. Planner sounds like plodder. I imagine a slow, methodical, cautious writer, someone conservative and anal-retentive. And pantser sounds like prancer, which conjures up a free spirit dancing her way through the writing process, waving scarves, no less. I do not identify with or endorse either approach. Too much planning discourages serendipity and inspiration. It’s deadening to the spirit, or so it seems to me. Too little (or, shudder, none at all) results in a muddled, meandering draft.

Character + PlotOkay. I’ve been hedging on which comes first, plot or character. Honestly, you can’t divorce one from the other.

Have you ever heard the phrase “character is destiny”? It is attributed to Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who must have been a keen observer of human nature. Thousands of years before the advent of psychology, Heraclitus asserted that one’s inner life manifests in one’s outer life. Put another way, it is not so much what happens to us as it is how we react to what happens to us. And because life gets complicated fast, so does fiction. Even in the most mundane situations, we have choices, lots of them, and how we react affects our destinies, sometimes by inches and other times by miles.

The example I’ll offer is one I use often because it’s so ordinary—and we’ve all been there. Picture it: you have stopped off at the grocery store on your way home from work. You are waiting your turn with the cashier even as you juggle the makings of dinner: a boxed frozen pizza, a bag of mixed greens, and a cucumber. That’s not all. Wedged into your armpit is a slippery bottle of pinot noir. You’re nearly at the front of the line when abruptly, and without a glance in your direction, a wiry man with a jar of pickles sidles in front of you. It’s blatant—he’s cutting in line. What are you going to do about it?

Surprisingly, there are numerous ways to react, and among them is my husband’s likely response: Tap the guy on the shoulder and firmly advise him to get to the back of the line. My late mother-in-law would have been subtler. She would have turned to the person behind her and complained loudly about the rudeness of “some people.” Lots of us would suffer in silence; others would be too engrossed in their phones to notice the intrusion. Someone out there might draw a gun, and at least one frazzled young mother would burst into tears.

Think about it: Unless you have real insight into your fictional characters, you don’t know how they will react in even the most mundane of circumstances, and without that knowledge, you aren’t ready to plan or pants your plot. The answer isn’t simple, but that’s life—and fiction.

Note from Jane: if you enjoyed this post, check out Sharon’s new book Writing the Novella.

April 12, 2021

How to Turn a Microsoft Word Document Into an Ebook (EPUB)

Note from Jane: This post has been updated to reflect changes in tools available on the market.

So your book is sitting in Microsoft Word, and you’d like to get that material converted into an ebook format you can sell through ebook retailers such as Amazon.

If you’re patient and willing to format your Word document carefully, you can use the automated conversion processes of Amazon Kindle, Smashwords, Draft2Digital, or similar ebook retailer and distribution services. They want to make it easy for you to get published, so they’ll convert your Word document into an ebook file instantly, as soon as you upload it.

But the results may look subpar if you don’t prepare your document first. I’m grateful to Dave Chesson at Kindlepreneur for sharing the following information on how to prep your Microsoft Word file to convert cleanly into an ebook file. Although it won’t have all the bells and whistles you’d get with professional book formatting software (e.g., Vellum or InDesign), it is cost-effective and used by many novelists. (This method will not work well if your work is highly illustrated or has many different styles, charts, etc.)

Side note: It’s possible you’ve also heard of MOBI files. These used to be the preferred ebook file format for Amazon. However, in 2021, Amazon announced that they would stop accepting MOBI files and prefer EPUB.

Before your start formatting your Microsoft Word fileBefore you begin, make sure you include all the different parts of a book. For example, most books have front matter and back matter.

The front matter consists of things like a Title Page, Copyright Page, and Dedication Page.The back matter could include an Author Biography, Acknowledgments, a Note from the Author, and sometimes a CTA (call-to-action).For your font, start with a black, 12-point standard font like Times New Roman.

Update your Microsoft Word paragraph settings and marginsAfter the font is set and you’re ready, change the indentation in the Paragraph settings. When writing a book in Word that you intend to export as an ebook, you need to refrain from using the Tab key and implementing hard indentations for every paragraph because this results in an indentation that is much too large for a book.

Instead, click into the Paragraph settings and change the indentation to First Line, then 0.2” or 0.3.” You can try a few different indentation sizes and see which one looks better. The line spacing should be changed to Single and the alignment should be set to Left for the body text.

The margins should be changed to 0.5”. Since ebooks are read on various types of tablets and digital devices and have reflowable text, the page size doesn’t matter and you can leave it at the default, which is 8.5” x 11” letter in the US.

Make your chapter headings consistent

Make your chapter headings consistentIt’s best to keep all the Chapter Headings the same throughout the book. To make sure Chapter Headings are uniform for all chapters, select the Chapter Heading in the document, then navigate to the Styles tab.

There are several options provided by Microsoft Word, such as Heading 1, Heading 2, Title, etc. You can modify the font type and size if you would like it to be different from the ones provided by Microsoft Word.

Then, select the Chapter Heading you’re modifying and apply the Chapter Heading style you created to every chapter in your book. Customizing the headings allows you to easily change all Chapter Headings or other types of headings in your book without having to change them manually.

After the chapter headings have been standardized, you can go to the View tab and check the box by Navigation Pane. This will allow the Navigation Pane to pop up on the side of the document. It shows all the chapter headings, making it easy to click to the beginning of each chapter without scrolling through the document.

Upload your Microsoft Word file to KDPSo you’ve successfully formatted your book in Word. Now what? Can you just upload it to Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) or another book service as is? Or do you have to do more?

Technically, you don’t have to do any conversions. However, pay special attention when previewing your file. Complex formats such as tables, images, and so on may not convert well. Verify everything looks good before publishing. You may also want to use one of the tools mentioned below to convert your Word file into EPUB outside of KDP and make direct changes to the EPUB file (which you can then upload to KDP).

There are more advanced aspects of book formatting, such as adding drop caps to the beginning of each chapter, creating fancier chapter headings, etc. As you become more comfortable with book formatting, you can experiment with more advanced style choices.

If you would like further information about book formatting check out Dave Chesson’s full guide on all things book formatting.

If you don’t want to mess around in WordHere are workable options that don’t involve buying software, with one exception. Again, these methods will only be appropriate if your book is predominantly text, with few images and specific formatting requirements.

Use CalibreCalibre is a free software that can convert your Word file into any ebook format. You can download Calibre here. Converting your book is painless, but preview your file extensively to make sure all your formatting translated well. You’ll likely need to make additional changes.

Start with Draft2Digital’s free conversion toolAuthors often report the Draft2Digital conversion from Word to EPUB to be the smoothest and easiest they’ve used. Fortunately, you don’t have to distribute through Draft2Digital in order to take advantage of their conversion; their terms of service allow you to set up an account, upload your Word doc, export the EPUB file, then take it elsewhere, to another retailer or distributor. (Not all ebook distributors are so kind in their terms.)

Once you’ve downloaded the EPUB file from the automated conversion process, you may be happy with it exactly as is, or you may want to open it up in Calibre to make adjustments.

Use Amazon’s free Kindle Create softwareAmazon offers Kindle Create to help you design and format ebook files using Word, but there’s one huge caveat: They will create ebook files that work on Kindle, but they will not be EPUB files. That means that the files you prepare using Amazon’s tools will not work at other retailer or distribution sites.

Use Reedsy’s free cloud-based editing toolsReedsy is best known as a freelance marketplace where you can find editors and other publishing professionals to help you edit, publish, and promote your work. They also offer a suite of editing and collaboration tools that can help you format and export EPUB (and print book) files out of their cloud-based system. Then you can load up your EPUB in another software, such as Calibre or Sigil, to make further adjustments if you don’t want to keep working in Reedsy.

For Mac users: Vellum ($)One of the most beloved tools of indie authors, Vellum is an intuitive software that helps you design, format, and export great-looking ebooks, in EPUB format. It allows you to start by uploading Word documents (among others). However, it will cost you. While the software is free to download, being able to export ebook files will cost you a one-time fee of $199. This option makes the most sense for authors who expect to be producing multiple ebook files over many months or years.

Dump your Word doc into some other word processor that can export EPUB filesIf you own or use any of the following tools:

Apple PagesScrivenerGoogle Docs… then you can export your document as an EPUB file. Sometimes it’s not a bad idea to take your Microsoft Word document, import it into or open it inside another one of these systems, then see how well it exports as EPUB.

For the unafraid and adventurous: SigilSigil is a free, open-source editor for EPUB (ebook) files. Probably the most difficult part of using Sigil is identifying how to download and install it, since it’s on Github and isn’t exactly marketed to the average non-tech consumer.

However, once you have the application installed, it’s not difficult to work with if you know a little HTML. If you can use WordPress—or even if you’re comfortable with Microsoft Word’s quirks—you can probably handle Sigil once your content is imported properly. It’s a very lightweight software.

Your turn: What tricks or tips do you have to share about creating and editing EPUB files? Let me know in the comments.

A Debut Novelist in a Pandemic: How to Navigate a Launch Through Social Media

Today’s post is by author Kathleen Marple Kalb (@KalbMarple), author of the Ella Shane Mysteries series.

It sure sounded like the happy ending: an agent and a three-book deal for my mystery series after two brutal years of querying, most of it during a family health crisis. All I had to do was get myself and my book ready for the big debut, and the heavens would open and the sun and spotlight would shine upon me, the wonderful new author.

Just one little problem: that big debut was in April 2020.

New author who?

No one cared about a fun little Gilded Age mystery with the world crumbling around them.

All entirely understandable. Even I didn’t care much some days.

But it was my book, my lifelong dream come true, and I had to find a way to promote it, even if I couldn’t leave the house to do it.

The only thing left to me was social media.

Sure, authors are told to have a “platform” these days, but I’ve thought of it as a part of the whole package, not my sole means of support. I’m a radio news anchor in my day job, and most of my knowledge of social media comes from the trolls who call me and my colleagues the “Spawn of Satan.” I wish that weren’t a direct quote, but it is.

With that experience in mind, I’d simply set up what my agent and publisher advised, never expecting to use it as much as my email, phone, and train pass.

Called that one wrong, too.

The good news: I had a traditional publisher, with a publicist and social media expert behind me. If you’ve ever wondered what you get for spending years of your life in the soul-killing swamp of querying, this is the answer: a team of very smart people who are on your side and have invested real cash money in your success.

While I was bailing a tsunami with a paper cup, at least I wasn’t fighting alone.

The publicist set up some virtual events, and the social media director gave me pointers. And then I held my breath and jumped. It wasn’t nearly as horrible as I’d feared.

Most folks in the reading and writing community are pretty nice, and most were very understanding and helpful when I showed up begging for attention, whether it was a guest post on their blog, or an interview, or just a few crumbs of useful advice. The founder of a Facebook genre group took me under her wing, and I ended up becoming an admin on the page. I made actual friends in the Twitter #WritersCommunity. A reviewer who liked my book pointed me to established authors who gave me more ideas.

Soon, I developed a routine. Every morning, after I get my son settled in Virtual School, I’d go online and prowl through social media, looking at what other writers were up to. If someone had done a guest post or interview, I’d track down the blog, host or podcaster and pitch myself. Shamelessly, but always politely and professionally.

I’ve also started managing my own content. And there’s a lot of it. I write two regular blog posts every week: one for the genre page and my website on querying survival tips, and one for my Goodreads page on fun historical facts. Every morning I put up a fun vintage image on all of my pages, followed by a series-related afternoon post on my Facebook author page. Then in the evening, it’s the daily goodnight post on the genre page, and some kind of vintage image for my own Twitter and Instagram feeds.

All of this sounds like a full-time job, and it very nearly is.

I approach it that way, anyhow. Being a pro never hurt me in my work life, and it’s certainly been a help now. No matter how scared or stressed I am (and I am, a lot!) I’m always polite, grateful and friendly. Nobody wants to hear me whine. They’ve got their own problems.

Now, I’m coming up on a new release. A Fatal First Night is due April 27th, and I’ve definitely taken a different approach, making social media the engine instead of an extra. Months ago, I started contacting the people I’d met along the way, setting up interviews, guest posts and more with an eye to this next book. It’s a lot less scary now, because I know the players, and what they expect. Easier, too, because it’s no longer the great unknown void of social media: it’s now a world I see every day.

So, did I save my publishing career with social media? Well, the jury’s still out on that. As an historical mystery author, I was probably never going to be a huge bestseller anyway. But I definitely have a good foundation for whatever comes next.

And maybe this time, it really IS a light at the end of that tunnel.

April 7, 2021

Everything You’ve Always Wanted to Know: Hybrid Publishing

Today’s post is by author Barbara Linn Probst.

As someone who has published (twice) with a hybrid press, I’ve become aware that there’s a lot of confusion about what the term means and how hybrid publishing really works.

Before I became a novelist, I was a qualitative researcher, so I did what comes naturally: I investigated. I looked at the websites of presses that call themselves hybrid (or use words like co-publishing, collaborative, or bespoke) and talked with ten people who had published with hybrid presses to learn about their experience. While ten isn’t a huge sample, clear patterns emerged from their stories that sometimes surprised me—and may surprise you, because they debunk some of the myths about why people choose to go hybrid.

I’ll begin by explaining what a hybrid publisher is (and isn’t) and conclude with questions you may want to ask if you decide to explore this option. In between, I’ll share what 10 authors had to say about why they chose the hybrid path, what they liked best and least, and what advice they would give to others.

What is a hybrid press?Hybrid publishing combines elements from two different sources.

It resembles self-publishing because the author carries the cost and financial risk; thus, it involves an investment of your own capital. It resembles traditional publishing because professionals, not you, carry out the tasks required to transform a Word document on your laptop into an object called a book that people can buy and read.It’s like hiring a contractor. You pay the contractor to oversee the design, construction, plumbing, electricity, and so on, because he has the contacts and expertise that you lack or don’t have the bandwidth to acquire. When it’s done, you own the house; the contractor produced it (for a fee), but he doesn’t own it.

The chief advantage of the hybrid model, for those who choose it, seems to be control—over timing, rights, outcome, and the product itself. The chief barrier, for those who do not choose it, seems to be money. For some, there may be a second issue—the dream of being traditionally published by a major publishing house and the fear that you won’t be a “real author” if a publisher/fairy godmother doesn’t tap you with her magic wand.

Yet here’s the truth: if it’s a good book, professionally produced, readers don’t care what imprint is on the spine. In my survey of what makes readers give an unknown author a chance (with over 750 responses), “publisher” was never mentioned.

The salient words are “professionally produced,” since “good book” is a matter of opinion. Not all presses that call themselves hybrid are equally professional, however, with equal track records. For a would-be author, the question is: how can I make a reliable assessment?

To help writers navigate this sometimes murky, often misunderstood landscape, the IBPA (Independent Book Publishers Association, 2018) issued a set of criteria for determining if a press is a reputable “hybrid.” While these standards are not enforceable, they do provide a helpful set of guidelines. According to the IBPA, a hybrid publisher must:

Define a mission and vision for its publishing program.Vet submissions.Publish under its own imprint(s) and ISBNs.Publish to industry standards.Ensure editorial, design, and production quality.Pursue and manage a range of publishing rights.Provide distribution services.Demonstrate respectable sales.Pay authors a higher-than-standard royalty.The way a publisher fulfills these criteria will vary, of course. Nonetheless, you should be able to get clear answers about how each item is addressed and what it really means.

Note: A hybrid press is not what used to be called a vanity press, where all you had to do to publish was write a check. Nor is it the “partnership” arm of a traditional press, as Jane Friedman warns in her article defining hybrid publishing, that uses a so-called hybrid option as a bait-and-switch: “Oh, sorry, your work doesn’t meet our editorial needs for our traditional publishing operation, but would you like to pay for our hybrid publishing [or self-publishing] service?”

Why do people choose hybrid publishing?The people I spoke with, all women, had published with eight different hybrid presses; in two instances, I spoke with more than one person using the same publisher. Two of the authors were about to launch their second books with the same press; another had published two books, each with a different hybrid publisher. They represented fiction, memoir, self-help, and parenting (nonfiction).

I had assumed that most had chosen hybrid publishing because they had tried, and failed, to get an agent and a traditional contract. I was wrong. Although three of the people I spoke with did have that experience, most did not. Time and again, I heard: “I never queried any agents, but went straight to hybrid.” There were two key motivators for that decision.

One was the desire for ownership and control. They didn’t like the idea that a traditional publisher, having “bought” their book, could change the title, choose the cover, edit or even restructure the contents. By retaining the rights, they could control both immediate and future decisions—for example, about reissuing in a different format.

The other reason was time. These were, in general, women over fifty who didn’t feel they had the time (or desire) to embark on the long and highly uncertain path to agented publication. They understood that getting an agent, difficult enough, did not guarantee publication. Some had watched friends, elated to find an agent after months or years of trying, sink into new despair when the agent couldn’t find a publisher for the manuscript—for reasons that might have nothing to do with its merits.

For those who had tried to find an agent, without success, the pivot to the hybrid route brought relief and a restoration of agency. As one person told me: “I’m never going to put myself through that soul-destroying process again.”

When I asked people why they chose hybrid rather than self-publishing, most felt that self-publishing was too much to manage. They didn’t have the time, skills, or inclination to take on a daunting set of tasks that they knew nothing about. The traditional distribution that the hybrid press offered was another important factor.

I then asked: “Why this particular hybrid press?” In many cases, it was serendipity—a referral, a chance encounter, something that “just fell into my lap and was a perfect fit.” The authors did their due diligence—made sure that the press was respected, produced books of high quality, and had a strong team—but few investigated other hybrids. Rather, they learned about the hybrid model and this particular hybrid at the same time.

One author used a different hybrid publisher for her second book. “I had done my first book with a hybrid that was much more expensive. By the second time, I’d learned a lot and could do a big part of it myself, so I switched to a different hybrid press that was much more affordable.”

How does hybrid publishing work?The first step is submission. Sample pages (or the entire manuscript) are evaluated, or “vetted,” to determine suitability for publication. To meet IBPA standards, not all submissions will be accepted. Some might be accepted on a contingency basis—that is, on the condition that the author pay for additional developmental and/or copyediting. Several people I spoke with had to do this, but none saw it as a ploy to get more money. Rather, they viewed it as a valuable step to make their manuscripts as strong as possible—and, secondarily, to protect the reputation of the publisher’s brand, which would benefit all.

Note: It can be difficult to interpret “acceptance rates,” since these contingency manuscripts might or might not be included in the reported rate. For any number of reasons, a contingency manuscript might not make it all the way to publication. A high (initial) acceptance rate doesn’t necessarily mean that the press will “take anyone,” just as a low acceptance rate doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s “more selective” and thus “better.”

Once an author’s work has been accepted, most hybrids offer a choice of packages, covering services from basic (design, production, and distribution) to enhanced (such as developmental editing, marketing material, or media outreach). Others take a strictly a la carte approach, either recommending a custom-designed plan or allowing the author to put together her own plan. Still others have a single fixed package.

Several people noted that the final price at “check-out time” was significantly higher than the price they were quoted on signing—not because the publisher had done anything improper, but because, as inexperienced authors, they didn’t know what else they would actually need. As the saying goes, they didn’t know what they didn’t know. Naively, they assumed that the contract price would be all they would have to pay.

In fact, there were additional costs before the book could get into readers’ hands—for advance reader copies, shipping, storage, permissions, etc.—that came as an unwelcome surprise. Those costs might be billed by the publisher, who took care of them, or the author might have to find a way to get the tasks done herself. One person told me that she had to obtain her own ISBN and pay for a proofreader—tasks she hadn’t realized were needed, but were not included in her package.

Assessing the hybrid publishing experienceThe best parts of the experience, for those I spoke with, were:

How professional everything was, from start to finish; the meticulous care and high quality at every stage, culminating in a beautiful finished productThe participation, control, respect, and veto powerThe communication and responsiveness; their patience in answering my questionsThe commitment and support that continued well past publication dateThe traditional distributionThe “insider education” about the entire publishing process; how much was learnedAspects that people regretted or found disappointing tended to center on the cost of tasks that they realized, in retrospect, they could have handled themselves. Several also wished that the publisher had helped more with marketing or offered a publicity add-on, since they overestimated the publisher’s role in promoting their book. Others were unhappy about the smaller-than-expected sales.

The big question, for some, was whether the investment had been worthwhile.That’s the question that arises most often about hybrid publishing, and a difficult one to parse because it depends so much on individual resources and goals. The cost for hybrid publishing might fall into a “discretionary spending” bin for one person—like a new car or a remodeled kitchen—while, for another person, it might mean dipping into precious savings. It might represent a lifelong dream, well worth the cost even if the money is never recouped, or a step in an entrepreneurial chain.

For some, the rationale for the expense was relatively clear:

I earned it. I’ve invested it well, and I’d like to spend some of that money on the things I most desire and care about.

In the end, it isn’t about the money. It’s about sharing my work with the world and receiving recognition of my ability as a writer. By writing a memoir, I’ve also given life to people who are no longer alive and preserved a time in history that many have forgotten or never understood. I spent large amounts of my life to accomplish this, and I’m glad I did it. How many people fulfill their lifetime dream? Who wouldn’t pay for that privilege, if they could?

For others, it was more complicated:

I felt a little guilty about the amount of money I spent and didn’t want to share that with anyone. I questioned how much I spent, especially when my book sales weren’t as good as I’d hoped. I think eventually, I just accepted that it was my money and in the long run I was proud of myself for having published my first book. Still the money remains a sticky issue for me. I’m not sure I’ve made my peace with it yet.

Some authors raised the funds in creative ways—and that’s important to know, because it debunks the myth that you need to have a large amount of disposable income in order to take the hybrid path. One person crowdfunded her first book and paid for the second one with the royalties she earned. Another found a relative willing to underwrite her first book, and then re-invested the royalties to earn enough to fund a second book at a much lower cost, since she had learned enough to handle many of the tasks herself.

I heard that it takes at least five years to start turning a profit when you’re an author like me, so I view this as a business start-up investment and hope it will pay off! Every book I add will create a new royalty stream, and I’ll keep reinvesting and building from there.

I concluded my interviews by asking people what they would say to a writer who was considering the hybrid path. Again and again, I heard three themes:

1. If you can afford it, do it.Authors said:

If you want to be a more active participant in the process, then hybrid is a good option because you don’t have to be out there on your own, doing it all yourself.

It’s a professional, respectable way for a debut author to establish an identity as a published author, a way of building legitimacy and credibility, that you can use as a stepping-stone.

2. Do your homework so you understand what you are committing to financially, and choose your publisher carefully.It’s the path of the future as traditional publishing becomes less and less accessible. It’s a good middle ground, especially for a first-time author. If you want to get your book out fairly soon, this may be a good path for you.

Authors said:

It’s a great option but make sure you really understand all the costs that are going to be involved, including printing and publicity.

If you have the money and it’s a high-quality hybrid press, do it. You’ll get your book out there a lot faster. Just make sure that the publisher is strong, with good credibility and the staff to support what needs to be done.

This is a crucial point. Because of the tremendous variety in cost, approach, and quality of presses that call themselves “hybrid” (though not all use that word), it’s important to do your research and avoid going with the first quote you’re offered or the first company you find.

3. Know your goals, vision, and expectations.Look inside and clarify what you want from this experience. Let go of the need to apologize for your choice.

How to research hybrid publishersIn addition to the IBPA criteria, here are some additional questions you may want to consider as you explore working with various hybrid publishers:

How long have they been around and how many books have they published? How many do they publish a year, on average?Do they do a print run, or ebooks only, and/or print-on-demand? Do you care?Do they offer a single fixed-price package, several packages, or a customized a la carte menu? If it’s a package, does it include everything you’ll need start-to-finish, such as printing and shipping to the distributor? If not, what other items will be needed and how much are they likely to cost?How big is their staff? Does it seem large enough to do everything they say they will do? What is the turnover?Look at the Submissions page. What does “vetting” actually mean?What kind of distribution do they offer? Are their books in bookstores and libraries?What is the projected time frame, from start to finish? Is there a queue or waiting list, or can they take you right now? How important is that to you?Look at the Amazon pages for some of their authors. Do their authors get trade and customer reviews? Win awards?Look at the titles. Do I see my book fitting here? If possible, order a couple of their books to see the quality of the finished product.What do people have to say who have published with this press?Rather than including a list of hybrid presses—especially since, in most cases, I have no direct experience and would not want to imply an endorsement (or a lack of endorsement of those I don’t happen to be familiar with)—I encourage you to explore for yourself through IBPA or other trusted sources.

One of the advantages of the hybrid route is that you get to choose a publisher and publishing package that’s right for you. My aim in this article has been to offer tools that can help you make that choice.

April 6, 2021

What Every Writer Needs to Know About Email Newsletters (They’re Not Going Away)

“Thomas Paine” by Leo Reynolds is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

“Thomas Paine” by Leo Reynolds is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0Today’s post is by author Catherine Baab-Muguira (@Greedzilla1), who offers the newsletter Poe can save your life.

You probably remember this one from history class: Thomas Paine, in 1776, dashed off a pamphlet called Common Sense, encouraging the American colonists to revolt against British rule, with the pamphlet supposedly proving so popular that, in its first three months of publication alone, it sold more than 100,000 copies. Also, it helped kick off a war.

Paine himself, it turns out, was the primary source of information regarding those astounding sales figures. If we take him at his word, then Common Sense remains the bestselling book in U.S. history. Stephen King can’t unseat it. Dan Brown? Can’t compete. Danielle Steele? GTFO! But what’s all this got to do with you, one more aspiring, ink-stained wretch, vainly attempting to build your author platform today, some 250 years later?

Everything.

Paine faced the same problem that you and I face. He and his fellow “pamphleteers” couldn’t rely on Buzzfeed and the New York Times to deliver up an audience. They had to discover it for themselves. Yes, the audience was there, in abundance, but to reach it, they basically had to start a Substack.

I’m not the first to notice the overlap between the pamphleteers of the 18th century and popular present-day mediums. For better or for worse, some 20th-century political operatives not only ran the same play as Paine—bypassing media outlets and instead mailing their messages directly to their would-be audiences—but wrote entire self-aggrandizing books about the strategy. They understood the power of building one’s own means of distribution, one’s own mailing list. In fact, “direct mail” was, arguably, how the right bankrolled the Reagan revolution. It’s how Karl Rove got his start.

Yesterday’s pamphlets and mail packages closely resemble today’s email newsletters. And now, in related news, just about every big tech company is announcing that they’re getting into the newsletter game, too. Both Facebook and Twitter are launching newsletter products, while the CEO of Medium recently declared the platform is pivoting from magazines to focusing on “individual voices,” i.e. newsletter-like offerings. Substack has even started paying six-figure advances to established writers they believe have the power to draw large numbers of paid subscriptions.

And you? If you haven’t already started your own newsletter, you’re probably mulling it, just seeing how everyone else is doing it.

Which brings us to the #1 thing writers need to know about newslettersEven as you and I are witnessing this 2021 crush of both tech companies and individual writers into the newsletter game, it’s crucial to understand that these developments are not new. (Neither are the, uh, sometimes-controversial politics.)

The difference is how newsletters are being reshaped by the internet and related trends in the larger economy, namely:

The continued move of advertising dollars away from traditional media and into Facebook and Google, which allow for much more specific ad-targeting;How this is pushing heavyweights including the New York Times and Washington Post to rely more and more on subscriptions, rather than advertising, as their primary source of revenue;The overall rise of the “subscription economy,” in which you and I and everyone else on the planet pay a few bucks each month for access to all manner of media, services, and products, from Amazon Prime to Netflix to diapers—really, we could keep listing things all friggin’ day.It’s a complex reality, but writers like us will misunderstand it, or attempt to ignore it, at our own risk. You don’t need to grasp the more intricate details, anyway, beyond the fact that Wall Street loves recurring revenue (i.e. subscription-business models, which give a lot of insight into a company’s financial performance), plus the other salient fact: You and I are on our own, here.

In a sense, all writers are “direct to consumer” brands now. Major publishers, from Slate to Simon & Schuster, are relatively risk-averse, reluctant to invest in anything but proven winners. Whereas it’s easier than ever, if also a very crowded scene, to build and reach your own audience through channels such as Instagram, or better yet, your own email newsletter. Picture yourself standing by the side of a choked digital freeway, holding up a little hand-scrawled sign that reads “Drop your email here, and I’ll come to your inbox with tips and updates!!”