Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 70

June 21, 2021

Starting Your Novel With Character: 3 Strengths and 3 Challenges

Today’s post is by regular contributor Susan DeFreitas (@manzanitafire), an award-winning author, editor, and book coach. She offers a first 50-page review on works in progress for novelists seeking direction on their next step toward publishing.

In my work as a book coach, I’ve found that writers of fiction generally fall into three camps: those who start with character, those who start with plot or story concept, and those who start with theme. In the course of this three-part series, I’ll address the natural strengths of each type, along with challenges faced in revision.

Writers who start with character tend to be empathetic people—“people people,” you might say. A new story for these folks may arrive in the form of a certain voice in their head, or a line or two that seems promising.

Or they might be struck at first by a type of character—for instance, a character who’s a bit like an intriguing person they happen to know, or a bit like a character in a book or movie they loved.

Regardless of how the character arrives, when given a name and a context, that character quickly develops a compelling backstory and three-dimensional depth, taking on a life of their own.

Often this type of writer has had this character in her head for years—sometimes even decades. She knows the character well, including their family dynamics, early childhood traumas, passions, phobias, secret insecurities, you name it. This type of writer is also prone to carrying over the same characters from one book to another, because they’ve come to know those characters so well.

Starting with character can be a very effective way to begin a novel, and writers who do so have these natural advantages on their side:

Strength: Characters make us care.A twisty plot, compelling themes, and fascinating setting are all great assets for a novel, but character is what makes us really care about the story.

Writers who start with character don’t struggle to create characters who seem alive on the page, whose struggles touch upon universal themes, and who exhibit the sort of complexity that makes us as readers really feel what it is to be human. All of this comes naturally to this type of writer, because her characters are so real to her from the get go that they only become more complex and compelling over multiple drafts.

Strength: There’s a solid market for character-driven fiction.The vast majority of novels that fall into the genres known as contemporary fiction, women’s fiction, and literary fiction are character-driven. Which is to say, there’s a solid contingency of readers who read fiction for exactly what writers who start with character are generally able to deliver, on every single page: The sense of being someone else, seeing the world through their eyes, and going through a meaningful transformation or change over the course of the story.

Writers who start with character generally don’t struggle to determine if there’s a market for the sort of thing they do, because that market is broad and well defined.

Strength: There’s no question whose story it is.Other types of writers may spend some time in the planning stages of a novel wrestling with the question of who their protagonist should be. But for writers who start with character, this generally isn’t an issue (unless there are so many compelling characters in their head that it’s just hard to choose among them).

These type of writers are not like directors looking for actors to play a part in their story—they’re more like directors making a biopic, with the story as a whole built around a certain character. (Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge is a good example.)

That said, there are several challenges writers who start with character tend to face.

Challenge: Too many POVsIf you do something well as a writer, why not do more of it? That’s often the position taken by writers who start with character, whether they realize it or not, by adding many different POVs in their novels.

Taking the points of view of other characters comes easily to such writers, and they generally find it fun, because they don’t struggle to get inside the heads of the protagonist’s husband, for example, or her kids, or even the checkout clerk at the grocery store where she shops.

And generally speaking, these other POVs are compelling and well written. But that doesn’t mean that including them serves the story; sometimes these other POVs are no more than game trails that lead the story off on tangents without contributing anything in particular to the main story line, and, as such, should be avoided.

Challenge: Lack of arcSometimes writers have so much love and sympathy for their protagonists that they have a hard time imagining a real flaw for that character, or some real issue in the way that person sees the world.

But without an issue or flaw—what story coach Lisa Cron calls a “misbelief”—there’s no real basis for a character arc, no clear way that the story will push the protagonist to grow and change. The first drafts of such novels tend to explore situations, events, and issues in the protagonist’s life without necessarily tracking a clear arc of change.

Challenge: Episodic or slow plotYes, readers in general find deep character work compelling. But that doesn’t mean a novel can just rely on character to keep the reader turning the pages. For that to happen, there needs to be a causally linked series of events, with emotional stakes, that escalates over the course of a story to a distinct breaking point—in other words, a real plot.

Because such writers often start by essentially following their characters around to see what they will say and do, they often face a real challenge in their second draft, which is to find a dramatic arc for the events of the story. This may involve moving events around in time, finding ways to link them in a more causal way, and/or working out a climax for the story and then restructuring it, so it builds to that point from multiple angles.

None of these issues are in any way insurmountable, and the more you get to understand yourself as a writer, the more comfortable you’ll become with your own process, both in drafting and revising.

Do you consider yourself a writer who starts with character? If so, I’d love to hear about your process in the comments below.

June 15, 2021

How Authors Can Leverage Facebook Ads to Sell More Books

Today’s post is by book advertising consultant Matt Holmes.

When authors want to advertise their books, three advertising platforms spring to mind for most: Facebook ads, Amazon ads, and BookBub ads.

And while each of these platforms can be amazing in their own right and even more so when used holistically together, without a strong foundation (i.e. a great book that has been edited and proofread, a strong book description, right pricing for your category or genre, a professional-looking book cover that fits in your genre, etc.), no amount of advertising can sell a poor quality book.

Once you have a strong foundation, the truth is that advertising takes time to perfect; it takes testing; it takes patience, persistence, and, ultimately, it takes money.

However, let’s brighten things up.

When you get your ads dialed in, they can truly transform your career.

As an example, my wife is an author of fantasy novels. Before we started advertising her debut series of books, we were lucky if they pulled in $40 per month!

Last month, this same series earned $8,550 in royalties, with $5,200 of profit—and that’s with just one series of three books; the fourth book is due out later this year.

And the advertising platform that did the brunt of the leg work was…

Facebook ads.

Let’s dive into it. Here’s what you’ll learn.

Why Facebook offers authors an incredible opportunity to position themselves in front of their ideal readersWhen to use Facebook adsAre Facebook ads worth your time and money?How to create scroll-stopping Facebook adsMy top 5 Facebook ads tips for authorsThe Facebook ads opportunityFacebook’s biggest and most valuable asset is data. As an advertiser on Facebook, you can tap into this data and pinpoint the exact people (readers) you want to reach with your ads.

As an example, if you know your readers:

Live in New YorkAre femaleAged between 45 and 55Work as an accountantHave been a newlywed for 6 monthsRecently movedEnjoy French cuisineOwn a dog and a fishAnd do yogaYou could potentially target them! Now, I wouldn’t recommend being this granular with your targeting; this is just an exaggerated example to show you how much Facebook knows about its user base. In fact, I have seen better results by leaving my targeting fairly open. I trust Facebook enough to go out and find the right people to position the books I’m advertising in front of.

So what sort of targeting should you be doing with your Facebook ads?Targeting is a big topic and what works for one author won’t necessarily work for another. However, myself and many other authors have seen the best results by targeting:

Author namesBook / series titlesTV showsMoviesGenres (e.g., romantic fantasy)As long as your targeting is relevant to the book you’re advertising, it’s worth testing. That’s not to say that every target you test will be a winner, but the more relevant you can be, the higher the chance of your Facebook ads converting into sales and therefore providing you with a positive Return on Ad Spend (ROAS); in other words, profit.

When researching potential targets, I can’t recommend enough that you keep track of all your tests in a spreadsheet. I have built my own Targeting and Tracking spreadsheet which you can use for free; it’s included in my Author Ads Toolkit, which comes with several other valuable resources.

It’s also worth noting that Facebook ads allow you to advertise not just on the Facebook News Feed, although that is where you are likely to see the majority of your traffic coming from, but also on Facebook Stories, Instagram Stories, Instagram Feed, Facebook Messenger and many more.

Before we move on, let’s first take a quick look at what a Facebook ad actually looks like.

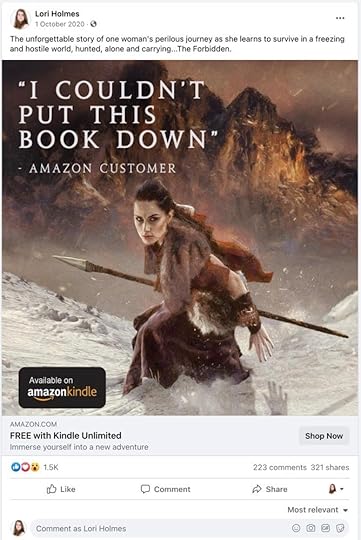

This is one of the ads I’ve run for my wife’s series of fantasy novels.

If you’ve spent any length of time scrolling on your Facebook News Feed, I’m sure you recognize the layout and style of this ad. As you can see, Facebook wants their ads to fit in with an organic post (i.e., not an ad) that you might see from one of your Facebook friends.

I’ll be walking you through the different assets that make up a Facebook ad, as well as some tips and best practices on how to create scroll-stopping ads.

When to use Facebook adsFacebook ads can be extremely powerful in many scenarios; whether you use them in all these scenarios or just one or two will depend on your ultimate goals and your strategy for building a career as an author.

Here are the 6 scenarios I like to use Facebook ads for:

Book launchesPromotions (e.g., $0.99 sale for 7 days)Evergreen sales (e.g., continuously advertising Book 1 of a series)Cross-series Retargeting (e.g. retarget people who have seen Book 1 of your series in a Facebook ad with Book 1 of another of your series in a similar genre)Same-series retargeting (e.g. if your books can be read in any order, retarget people who have seen one book from your series in a Facebook ad and show them another book from that same series)Building your mailing list (e.g., giving people a free copy of one of your books in exchange for their email address)By no means do you need to use Facebook ads for each of these scenarios! Start slow and then build at a pace that works for you once you begin to see results.

I started by purely running ads for Book 1 of a series; I learnt the ropes, so to speak, got my head around the Facebook ads interface, started testing different audiences and discovered some that completely flopped and others that worked like gangbusters!

I also tested a variety of different ad creative (i.e., the ads that people see on their Facebook News Feed), and once again, I found some images resonated more with my target audience better than other images did; the same was true with the text I used in the ads.

This process of testing and finding my feet took around three to four months, but I was only spending $10-15 per day to begin with.

If I were spending $50-$100 per day, I would gather the statistically significant data I needed much quicker than the $10-$15 I was spending each day.

This statistically significant data I’m talking about here is the data in my Facebook Ads dashboard that I look at, then decide whether to turn an ad off, or stop showing ads to a particular audience, or maybe increase the ad spend on one of my campaigns, for example.

After all this experience (and the mistakes I’ve made along the way), I now use Facebook ads for book launches, promotions, and I continue to use them for evergreen sales and same-series retargeting; there’s never a day goes by when I don’t spend money on Facebook ads!

Are Facebook ads worth your time and money?After what we’ve been through so far, you may be thinking, “This all sounds great, but do I really need to spend the time and money on Facebook ads? Can’t I just let Amazon and the other retailers do the selling for me?”

This approach of letting Amazon and the other retailers (e.g. Kobo, Barnes & Noble, etc.) sell your books for you did work back in the early days of self-publishing. But today’s marketplace is much more competitive. There are millions upon millions of books vying for readers’ eyeballs and wallets.

The Amazon algorithm for one has become much harder to crack; in order to tickle the algorithm enough for Amazon to start promoting your book for you, you first need to generate some sales. If you have a big email list, great! This is one way to sell books.

But if you want to build a thriving career as an author, you need to reach people who haven’t heard of you or your books before. In the marketing world, these people are known as a cold audience. And Facebook ads offers one of the most cost-effective ways to reach a cold audience.

Yes, it’s going to take some time to learn how to run Facebook ads, to understand the data and what to do with that data in order to optimize and scale your ads.

And yes, it’s also going to take money, because, although it does happen from time to time, you’re unlikely to hit a home run with your first Facebook ad! It’s going to take some testing to find winning audiences and winning ads.

The beauty of Facebook ads, however, is that you don’t need hundreds or thousands of dollars to see success from them. You could spend just $5 a day if you’re not comfortable budgeting more than that to begin with. And if at any time you don’t like what you’re seeing in your Facebook ads dashboard, with one click of a button you can turn your ads off and you won’t spend any more money; you are in complete control.

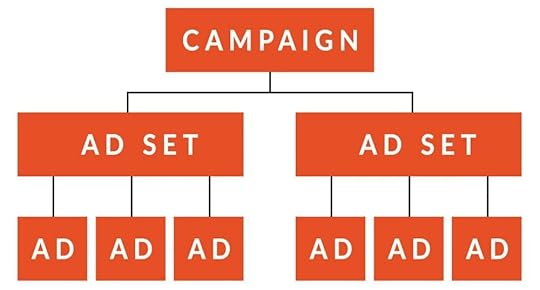

The Facebook ads structureBefore we dive into what makes a scroll-stopping Facebook ad, it’s important that you first understand how Facebook ads are structured.

It’s a very simple structure with only 3 levels:

LEVEL 1: CampaignsLEVEL 2: Ad SetsLEVEL 3: AdsHere is a visual representation of the Facebook ads structure which clearly shows how each of these 3 levels work cohesively together:

Let’s look at each of these levels in a little more detai

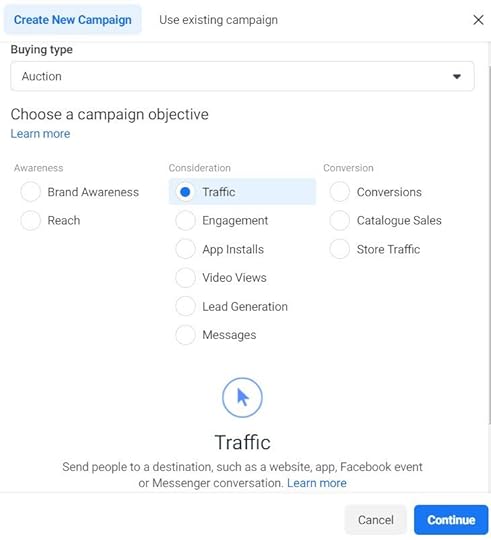

LEVEL 1: CampaignAt the Campaign level, you are setting your Campaign Objective: what you want your Facebook ad to do for you. At the time of writing, there are 11 Campaign Objectives to choose from. The one that I recommend you choose is Traffic. This will let Facebook know that you want them to send as much traffic (i.e., people who click on your Facebook ad) to your Amazon book product page (or wherever you want to send them).

Put simply, with the Traffic objective selected, Facebook will find people within your target audience who have a strong history of clicking on Facebook ads, as they are highly likely to click on your Facebook ad too!

LEVEL 2: Ad SetsThis is the exciting part, as the Ad Set is where you define the targeting: who you want to see your Facebook Ad. You can base your targeting on:

Location: Country, State, Postcode/Zip CodeGender: Men or Women or bothAge: 18–65+ (and everything in between)Languages: English, French, German, etc.Detailed Targeting: For example, authors, books, TV shows, films, genres, etc.You also decide at the Ad Set level where you want your Facebook Ads to appear within the Facebook ecosystem. As I mentioned a little earlier, you will find that most of the action takes place on the Facebook News Feed. However, I have found that giving Facebook free rein on where it decides to show my ads delivers better and cheaper results.

This is why I choose Automatic Targeting for Placements; every layer of targeting you add at the Ad Set level throttles the Facebook algorithm and performance can suffer because you’re not letting Facebook do its thing.

Some Facebook advertisers (outside of the author world) use a tactic known as Open Targeting with their Facebook Ads. Essentially, they provide Facebook with a location (e.g. United States) and that’s it! No age range, no genders, no detailed targeting.

Facebook’s algorithm is clever enough to figure out who are the right people on Facebook to achieve the advertisers Campaign Objective. Unbelievable, right? To achieve this unfathomable goal of Open Targeting, however, your Facebook Ads account needs lots of previous data to work with.

And that’s what you’re building when you are testing audiences and ads.

Speaking of ads, let’s move onto level 3 of the Facebook ads structure.

LEVEL 3: AdsThis is where you get creative! You build your ads (i.e. the ads that people will see on their Facebook News Feed) at the Ad level.

And to be honest, based on my experience, the ads really move the needle in your Facebook ads success. Yes, audiences are vitally important, but if the ad doesn’t resonate with your audience, they’re unlikely to click on them and won’t even visit your book product page.

You can include up to 50 individual Ads within a single Ad Set, however, I recommend keeping the number of Ads in an Ad Set to 3 or 4. The more Ads you have in an Ad Set, the more budget you will need as there are more variables for Facebook to test. With 3 or 4 Ads in an Ad Set, Facebook will be able to find a winner (i.e. the Ad that resonates most with an audience and generates the most clicks for the lowest cost) relatively quickly.

How to create scroll-stopping Facebook adsNow you have a better understanding of how Facebook ads are structured, let’s drill down into level 3, the Ads and what makes a scroll-stopping ad.

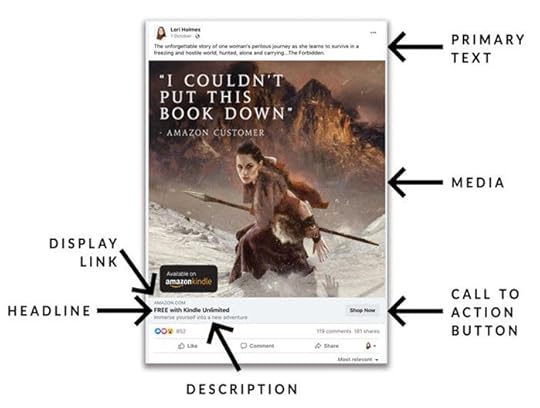

A Facebook ad is made up of 6 core assets or elements:

Media (i.e. Image or Video)Primary TextHeadlineDescriptionDisplay LinkCall-To-Action ButtonBelow, you can see a labeled visual representation of a Facebook ad to put everything into context for you:

Let’s take a look at each of these assets that make up a Facebook ad and cover some best practices and ideas you can use for your first Ads.

Primary TextStarting at the top of the ad, the Primary Text is the text that sits above the Media (typically, an image or video). There really is no right or wrong way to use your Primary Text; you just need to test different angles, different approaches and structures and see which option performs best for your books.

If this is your first time writing any sort of text for advertising or marketing purposes, you may be struggling with where to start. Below, you’ll see a simple structure I like to use that performs incredibly well. Feel free to adapt this as you see fit:

Start with a strong, powerful review of the book you’re advertising (including where the review came from, e.g., Amazon)Then move on to a 1-2 sentence teaser of your book (conflict, stakes and tension)Include 1-3 review quotes from the reviews on your book product pageEnd with a Call-To-Action, such as “Start Reading Today”, followed by a linkTo put this into some context, here is a real-life example of one of the best performing pieces of Primary Text I’ve written for Book 1 of my wife’s fantasy series:

“If you enjoyed Clan of the Cave Bear you should read this” Amazon Customer

The unforgettable story of one woman’s perilous journey as she learns to survive in a freezing and hostile world, hunted, alone and carrying…The Forbidden.

“It was a book I found hard to put down. The story grabs you from the start.”

“I couldn’t help but imagine what the characters in this story were experiencing.”

“You’re immediately sucked into the story and feel yourself becoming entwined with the main character”

Start reading today and escape into our own dark and forgotten past… → [LINK]

Another option for your Primary Text is to use a short passage from your book, word for word, as this gives readers a taste of your writing style or the story. After this short passage, end your Primary Text with a call-to-action and a link where readers can purchase a copy of your book. This approach can work exceptionally well when you choose a passage that leaves the reader wanting to know more.

The following example is again, for my wife’s fantasy series and, to date, is the best-performing piece of Primary Text for this book:

The lie that had got her this far crumbled as the truth closed its merciless jaws around her heart and sank in deep. He was dead. Her senses had already told her what she needed to know, but some masochistic part of herself reached out for him all the same.

He promised.

The nothingness that came whipping back to her was crippling. She screamed her loss to the frozen, uncaring sky.

Rebaa did not know how long she crouched there, lost in her grief. The wind howled, whistling through the rocks, tearing relentlessly at her furs. The loneliness of its wail settled the true extent of her situation around her quaking shoulders.

She was utterly alone; abandoned far from her native land with no tribe to protect her. Her breath came faster. She was a dead woman walking.

— From ‘The Forbidden’ (The Ancestors Saga, Book 1), by Lori Holmes

Start Reading Today → [LINK]

Warning! Your Primary Text is NOT the place to write a blow-by-blow account of what happens in your book! Nor is it the place to write a full synopsis! You need to put your advertiser’s hat on to write your Primary Text.

MediaYou have a couple of options with your Media: use an image or a video. I have done extensive testing of both and have always found that images deliver better results than video.

This is great news because you don’t need to spend a lot of money and/or time creating videos! You can create images for your Facebook ads relatively quickly using free tools such as Canva, or paid tools such as Adobe Photoshop.

With this in mind, let’s take a look at some possible ways you can use images in your Facebook ads.

When creating your images, make sure the resolution is 1080 x 1080 pixels (i.e. square) as this is what Facebook recommends; square images also take up more real estate (i.e. space) on a mobile phone screen, which is the device that the majority of people use when scrolling through their Facebook News Feed.

The following options I’m about to walk you through are by no means exhaustive; these are just three possible ideas for you to consider and test for your own books. By all means, get creative and test a range of different ideas and discover your winning images!

The 3D Mockup. You can use a tool such as BookBrush to create these 3D mockups of your book in either paperback or ebook format. Then use an image editor such as Canva or Adobe Photoshop to place the mock-up on the main background image of your book cover.

I like to include a strong review quote in the image as well and make it big and bold! This layer of social proof can be incredibly powerful and really makes your image stand out.

Idea 2. Book Cover Image. This image layout has been my best performing idea. It’s simply taking the main image of your book cover, without the title and author name, and adding a review quote.

If your book cover includes a character, as in the example above, this can really help with engagement, especially if said character is looking directly at the viewer as it will draw the viewer’s eye into the image and into your ad.

You could also add the logos of where your books are available (e.g. Amazon, Kobo, etc.), but this won’t have a massive impact on performance.

Idea 3. Shake it up! I like to test new image ideas on a monthly basis; this way, I always have other options I can use if a previously winning image becomes less effective.

The image above is one that I tested after experimenting with the different elements of the book cover in Photoshop, and it’s one of my best performers to date. You never know how something will perform until you test it.

HeadlineThe next element of your Ad is the Headline, which is the bold line of text that appears directly underneath the Media.

You can write anything you like here, within reason. However, from my testing, I have found the following to be the best performers…

A review quote (in quotation marks, to signify that this is a quote/review)A comparison to another book, series or author (e.g. “if you enjoyed XXX [BOOK] you’ll love XXX [YOUR BOOK/SERIES]”If you are running a time sensitive promotion, let people know (e.g., $0.99 until March 30th)Or, if your books are exclusive to Amazon and therefore available in Kindle Unlimited, let readers know (e.g. FREE with Kindle Unlimited)DescriptionThe Description on your Facebook ad is the small line of text underneath the Headline, but it isn’t always visible; it depends on the device someone is using when they see your ad (e.g. iPhone, iPad, desktop, etc.) and also how long your Headline is and whether it runs onto 2 lines.

You don’t have to use a Description at all, as it is optional in the Facebook Ads Manager and, truth be told, from my experience and testing, adding a Description has very little, if any, impact on the performance of your ads.

If you do want to include a description however, here are a few ideas for you to consider and test:

Short quote from a review (in quotation marks)How the book can be consumed (e.g. Kindle | Audio | Paperback)A tagline that calls out to your ideal readers/genre (e.g. Begin an Epic Fantasy Adventure)Call-To-Action ButtonYou can choose from a number of preset buttons to include in your Facebook Ad, or you may decide not to have a button at all.

The button that has consistently performed the best for me is Shop Now, which is the one I recommend you start with. However, feel free to test any of the other relevant options, such as Learn More and Download.

Display URLThis is simply the abbreviated version of where you are sending people when they click on your Facebook ad and it will be automatically populated once you enter the URL of your book product page in the Facebook Ads Manager.

For example, if your book product page URL is https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0937HVNDH, Facebook will shorten this and use AMAZON.COM as your Display URL.

And that is how you create scroll-stopping Facebook ads! Clearly I’ve just scratched the surface here, but what I really want to drill home to you is that when you’re testing ads, that you test 1 variable at a time.

What do I mean by this?

Let’s say you want to test three different images to see which one performs the best. You would create three identical ads, with the only difference being the Image. The Primary Text, Headline, Description and Button would be exactly the same in each version of the ad.

Once you have found a winning image, you can move onto testing a different asset of the ad; for example, the Primary Text. For this scenario, you would, again, create 3 identical ads, with the only difference this time being the Primary Text. The Image, Headline, Description and Button would be exactly the same in each of the 3 ads.

If you were testing 3 different ads in a single Ad Set and each ad was completely different, you wouldn’t know if it were the ads or the audiences that resulted in the positive or negative results from that test. So always test 1 variable at a time!

Regarding which assets of the ad have the biggest impact on performance, and therefore the assets I recommend you focus your testing on initially, are, in order of impact:

MediaPrimary TextHeadlineAs humans, we consume images 60,000 times faster than we do text, so it’s no surprise that the Media of a Facebook ad has the biggest impact. The Primary Text allows you to speak to readers and entice them enough to click your ad. And the Headline is a bold piece of text on your ad that stands out, so use it to drive home a clear, concise message.

If you want more inspiration for creating your own Facebook ads, I highly recommend checking out The Facebook Ads Library. This is a free tool provided by Facebook whereby you can quickly and easily search for any advertiser on Facebook (i.e., authors) and see what ads they are running.

Clearly, I’m not saying to copy these other authors’ Facebook ads. But analyze them, look at their ad images, how are they writing their Primary Text? What are they using as a Headline? What Button are they using, if any?

This is an amazing resource and one that you should definitely be referring to on a regular basis.

My top 5 Facebook Ads tips for authorsI could write even more about all the tips I’d like to share with you! But these 5 are the most important based on my experience.

1. Be patient and start small.Facebook ads take time to mature; they are like a good cheese, or a fine wine and improve with age! When you first set up a Facebook ad, the Ad Sets within your Campaign will go into something known as the Learning Phase.

Essentially, the Learning Phase is where Facebook shows your ads to pockets of people within your target audience and sees which ad is resonating most. It is also analyzing the characteristics of the people who engage with your ads the most, and will then go out and find more people like that in a different pocket of your target audience.

The Learning Phase lasts for around 1–3 days, depending on your budget, as an individual Ad Set needs to receive 50 clicks before it can exit the Learning Phase.

During the Learning Phase, you may notice that costs and performance aren’t quite as good as you’d like them to be. Don’t panic! Performance will stabilize and improve once your Ad Sets are out of the Learning Phase.

Even after the Learning Phase is complete, Facebook will continue to learn and improve for as long as your ads are running.

There will come a time when ads just stop performing as well as they did in the past and your costs will start to increase, or you will see a decline in sales, page reads and royalties. However, there’s no set amount of time when this can happen; I’ve had ads that have performed well for 2 weeks, then they start to deteriorate. On the other hand, I’ve had ads that have run for 6–8 months with superb, consistent performance.

But ultimately, don’t tinker with your ads every day! If you do this, you run the risk of your Ad Sets falling back into the Learning Phase.

Personally, I like to make all my optimizations, create new Campaigns, Ad Sets and Ads (if required) on a weekly basis at most, typically on a Monday morning. I then let them run untouched until the following Monday morning, where I review the data and adjust accordingly.

And don’t feel you have to launch into Facebook ads with a $100 per day budget! Start at whatever you can afford. That could be just $5 or $10 per day; it’s where I started and where a lot of authors start.

Once you are comfortable with the Facebook Ads interface and you’re seeing a positive return on your investment, then you can start increasing your ad spend gradually.

When you start increasing your ad spend, however, do so slowly; I recommend no more than 10% to 15% per week. If you increase your spend too aggressively, your Facebook Ads account could be shut down, so take it steady.

2. Test multiple audiences and ads.Facebook has 2.85 billion (yes, that’s billion with a B) monthly active users. That’s a lot of people! Clearly not all of these people are going to be readers who enjoy books like yours. However, you should be consistently testing new audiences and ads as you never want to be in a position where you’re relying on one audience and one ad to do all the leg work for you.

Audiences change over time, as do their preferences in terms of what ads they like and what ads they don’t like. Keeping your ads fresh is one of the best ways to avoid ad fatigue, which is where your ads start becoming less and less effective, people start seeing the same ads too often and your costs start to rise.

Likewise, you don’t want the same people to be seeing multiple different ads for the same book, which is why testing different audiences is so important too; you want to be reaching new people every week and positioning your books in front of readers who have never heard of you. That is how you build your career as an author, by introducing your books to new readers.

Personally, I test new audiences every single week, and I test new ads at least once per month, sometimes more frequently than that. You don’t have to test new ads and audiences that regularly, particularly if you only have a small budget to work with. I would recommend, however, that you test new ads and audiences at least once per month.

3: Keep an eye on the dataUnfortunately, there is no real way to track how many sales your Facebook ads are generating. You can use Amazon Associate Tracking Links, but it goes against Amazon’s terms of service (TOS) to use their Associate links in Pay-Per-Click Ads (which is what Facebook Ads are).

So, the best way to track the performance of your Facebook ads is to compare them to your baseline numbers

Your baseline numbers are the sales, KU page reads (if applicable) and royalties you were generating before you started running Facebook ads. It’s also worth noting your sales rank here too. Ideally, you should use a period of at least 30 days where you weren’t running any ads, or had any promotions or book launches.

Then, once you’ve run Facebook ads for 30 days consistently (again, with no promotions or books launches), compare your results (sales, page reads, royalties and sales rank) to your baseline numbers.

It’s not 100% accurate, but unfortunately, there’s no real way to see the data without using the Amazon Associate links.

I recommend tracking all your numbers in here on a daily basis in a spreadsheet; this way, you will be able to spot patterns in the data and make adjustments accordingly.

4. Don’t think of ad spend as wasted money.Many authors are understandably worried about spending money on ads and not seeing a return on that investment. If this is you, I can’t recommend enough that you work on changing your mindset around this, because it will really hold you back from achieving your dreams and goals as an author.

When you see advertising as an investment, rather than an expense, it becomes a lot easier to make rational decisions with your ads. You could be days away from one of your Facebook ads hitting the big time, but if you are worried about the ad spending too much money, you may hastily come in and turn it off.

As I mentioned earlier, I recommend leaving your ads to run for at least 7 days before making any decisions on whether or not to turn them off. If something isn’t working after 7 days, it’s unlikely to improve if you give it more time. This isn’t always the case, but it’s a good rule of thumb. If you’re spending $5 per day on an ad, then I recommend leaving the ads to run for 10–14 days, just so that you have the time to collect statistically significant data.

When you’re testing different ads and audiences, you are buying data. You are investing in understanding what works and what doesn’t work. This is invaluable! Iif you know what audiences and ads work for your books and which ones don’t, you know not to use those ads and audiences again. This is the mindset you need to approach advertising with.

5. Enjoy the process!Another mindset shift here: You are learning something new; you are building skills and you are crafting and investing in your future. Facebook ads have the potential to put your books into the hands of thousands, hundreds of thousands, millions of readers around the world. Isn’t that an incredible feeling?

I completely understand that learning something new, such as Facebook ads, can be daunting and overwhelming, but if you do nothing about it, you can be left in a state of paralysis by analysis, whereby you end up taking no action at all.

Once you get the ball rolling, it’s much easier to keep it rolling. Similar to pushing a car, it’s hard to get the car moving at first, but once you’ve got it going, it becomes easier. The same is true with learning how to advertise your books.

Final thoughtsAfter reading this article, I hope you now have a better understanding of the potential of Facebook ads. It is an incredible advertising platform and although it’s not a magic bullet, Facebook ads can truly transform your author career. Sure, it has its challenges, but life would be boring without challenges, right? Just take it steady, start small, learn, build your skills, analyze the data to make informed decisions, and enjoy the process of learning something new.

June 14, 2021

How to Be a Great Podcast Guest: A Guide for Authors

Photo by Soundtrap on Unsplash

Photo by Soundtrap on UnsplashToday’s post is from book marketing coach Sue Campbell (@suecampbell_) of Pages & Platforms, who offers a podcast appearance checklist and a host of free marketing resources when you join her newsletter.

Being on a podcast can be a great way to promote your book, but if it’s your first time on a show, you might not have a clue how to proceed. Even frequent guests may not realize how they can improve their appearances with straightforward preparation and a little bit of strategy.

Guesting on a podcast can raise your visibility by piggybacking on the audience the host has already built. Someone has taken the time and effort to create a community, and now you have the opportunity to interest their listeners in your book and get them subscribed to your newsletter. In other words: the podcast’s audience could become yours.

One of the great things about podcasts is that the interviews don’t take up much of your time. Once you get the hang of it, they take far less time than, say, writing a guest post. But you do need to spend a little time preparing.

PreparationDouble check your call time. Everybody’s in different time zones, so clarify what time the call is scheduled for. I’ve had clients who got the time wrong or the host got it wrong. Put the call on your calendar, set a reminder, and show up a bit early and ready to go.Send your media kit. Your media kit includes pictures of you, your bio, and a description and images of your book. This gives the podcast host all they need to create show notes for the episode and share it on social media. Send it to your host ahead of time to make their life easier. In your kit, include a call to action inviting listeners to sign up for your newsletter (it’s great to offer them a little freebie in exchange), and ask your host to put that in the show notes too.Listen to as many episodes as you can. If you pitched the podcast yourself, then I hope you’ve already listened to the podcast. Either way, once you’re scheduled for the interview, you want to listen more closely to some episodes. Whenever you’re doing the dishes, doing laundry, or going for a walk, listen to that podcast so you become familiar with the host. You will get a feel for what works and what doesn’t for that audience and what questions to expect.Read the podcast’s reviews. Think about how you can best serve that audience. Read the reviews for that particular podcast and you’ll get a sense of that audience and how you can best serve them. What information can you share, what resources can you offer, that will help them? If you manage to intrigue, inform or entertain them, they will seek you out online.Prepare talking points and stories that you are going to tell on the podcast based on the research that you’ve done by listening to episodes, reading reviews and, of course, whatever you said you’d talk about in your pitch. (For more tips on how to talk about your book, see this post.) Most hosts will tee you up to tell their audience where to learn more about you, so be sure to prepare a call to action as well. You want something like, “I have a free gift for your listeners on my website, just visit [website] to get the prequel to my series for free.”Get the tech rightRead through any tech instructions the host gives you. Many podcasts send you a document or email that tells you what to expect and has instructions for how to set up the technology for recording. Some hosts will even send you a microphone. Make sure that you read, understand and follow their instructions.Use a microphone! I don’t know about you, but if I turn on a podcast and the sound quality is abysmal and I can’t understand what is being said, or there’s background noise, I will turn that nonsense off. I once asked a podcaster friend to have someone on their show and he reported back annoyed that the guest I’d recommended didn’t have a microphone and was wandering around their house with tons of background noise while recording. Ouch. Ideally, you want a mic and headphones to prevent feedback during recording. If you’re going to be doing a ton of podcasts you may want to purchase a professional quality microphone. You can get a durable, great sounding mic for around $100, even less. (And you can use it for all your Zoom calls, too.) If you’re just dipping your toe in and don’t want to invest any money yet, the earbuds that came with your phone will work better than nothing.Think about how you’ll make your space quiet. You want to minimize background noise as much as possible. Think about how you’re going to make your space quiet. Bedrooms have lots of sound dampening qualities. Unfortunately, in my house, the bedroom is adjacent to the neighbor dogs who never stop barking. Think about what’s going on in your neighborhood—all of the sounds that you have learned to tune out but other people can hear. It might warrant a conversation with the neighbors or mean hanging a sign on the front door telling people not to knock during a certain time period. You can even buy a portable voice booth isolation box thingy for your desk. You stick your microphone inside it to dampen unwanted sound.Practice your talking points using your tech setup. Of course you should practice your talking points, but I recommend going a step further and practicing using the tech setup that you’re going to be using for the interview. Arrange a call with a friend to rehearse. You could use Zoom or the like. Ask your friend how you sound and how things in your background look while you’re at it. It will also help you get used to seeing yourself on screen if that’s part of the podcast tech. (By the way, many podcasts are simulcast on video these days, so it’s good to assume you’ll be on video—or find out beforehand.)Measure response and capture readersCheck your stats (sales, subscribers, website). Just before the episode airs, check all of your stats. See how many subscribers you have and how many books you’ve sold. See how many website visitors you have had. These numbers will give you a snapshot of where you are before the episode. Check again afterwards to gauge the impact of being on this podcast.Extra credit: Set up a landing page. You get bonus points from the marketing fairies if you set up a landing page specifically for listeners of the podcast that will deliver your reader magnet (your free thing you give to new subscribers). This allows you to keep stats so you know how many people actually sought you out as a result of hearing you on the podcast. You also want to look at how many people actually subscribed versus only visited the page. You’re aiming for about 30% of the total visitors subscribing to your reader magnet. If you’re not hitting that, look at the language on your landing page. Maybe you need to tweak your reader magnet. There are a lot of things to consider, but a dedicated landing page will give you the data to start making some informed decisions.During recordingA podcast is really just a conversation. Concentrate on connecting with the interviewer and you can’t go wrong, but here are some things it can be helpful to think about while recording.

Side note: You definitely want to eat something that agrees with you and pee before you are on a podcast! You don’t want low blood sugar—fainting while recording is not recommended. Eliminate potential bodily distractions so you can focus on having a pleasant conversation with someone.

Be yourself. What got you on the podcast in the first place is you, your book and your unique perspective. So be yourself. Of course, you’re likely to have a few butterflies in your esophagus (mine are never in my stomach) and that’s perfectly fine.Redirect questions if needed. If you get asked a question you’re not sure how to answer, just redirect. Buy some time while you collect your thoughts. You can use answers such as, “That’s a great question. You know who you should ask about that…” Or answer with what you wish you had been asked.Understand that nobody is perfect. No one is perfect on a podcast! Even if you feel like you’re rambling, you’re probably not as much as you think you are, so just keep rolling. If there’s a huge mistake or interruption, you can stop and ask the host to start that section over.Pretend you’re only talking to the podcaster. Especially if you’re an introvert, it helps to pretend you’re just talking to that one person. Don’t psych yourself out by thinking about the thousands or millions of people in the audience.Deliver your call to action. If you want to stick the landing, you need to deliver your call to action at the end. You don’t want to go through all of this work of research, pitching and preparation and then not tell them how to find you and your book. Write your call to action on a piece of paper and put it right in front of you so you don’t flub at the end.After the showNow that it’s over, resist the urge to dwell on any small missteps and do these things instead:

Thank the host! I grew up in Minnesota where the thought of not thanking someone is absolutely abhorrent. Mind your manners and send a thank you either by snail mail (for a nice touch) or a quick email of appreciation.Promote the episode. When the episode comes out, you want to promote it on social media and to your email list so it’s not just about getting exposure for you, it’s also about bringing your audience to the podcast.Recommend other guests. Hosts are always trying to fill their roster with engaging guests. If you think of someone who would be a great fit for that podcast, share that.Ask the host for referrals to other influencers. You can also ask the host for referrals to other podcasts or for the names of other influencers who might be interested in you and your book. You might be surprised at how often they will think of someone you didn’t know about.Ask someone honest for feedback. If you’re not used to being on the podcast circuit, ask for feedback from someone in your life who you know is going to give you an honest assessment. You want to know any annoying quirks you may have (ums, ahs, repeat phrases). You’re probably not going to nail it your first time out and that’s okay. You’re also not necessarily the best judge of your performance, so if you can get another set of eyes on that (or ears, in this case), it can help you improve going forward.Check your statsCheck your stats again to see what impact being on that podcast had. You can determine if this is the kind of audience who really appreciates what you bring.

Oftentimes we want to focus on the big podcasts because we assume they can move the needle the most, but that’s not always the case. Sometimes smaller podcasts have a more engaged following and you can get a bigger spike in traffic and increase in subscribers.

Stats will help you get a feel for what kind of podcasts do well for you and what topics work to build your audience.

Send another pitch!Finally, send another pitch as quickly after your guest spot as you can. You don’t want to think of any one podcast as a golden ticket that means you don’t have to do this anymore. On the flipside, if it was a disaster, you needn’t think “Now I’m doomed to failure and can never do this again.” Just keep pitching.

Follow these tips and you will be more than prepared to guest on any podcast. You will relax, enjoy the conversation and grow your audience.

June 9, 2021

I’m Selling Books on TikTok, No Dancing (or Crying) Required

Today’s post is by Ashleigh Renard (@ashleigh_renard), author of the memoir Swing.

Two months ago, mentions of TikTok flooded my online writers groups, all due to a New York Times headline: How Crying on TikTok Sells Books.

Yes, it’s true, TikTok does have the remarkable power to sell books. Ever since I started marketing and promoting my memoir, sales have correlated to the popularity of my videos on TikTok. Visitors who come to my website from TikTok are ten times more likely to click through to purchase my book than those who come through targeted (and expensive) Facebook ads.

TikTok has also driven the increase in my Instagram audience (+33k in eight months) and my newsletter sign-ups (+3k in eight months).

How in the world am I getting people interested in my writing (and actually buying my book) by using a video-only app?

TikTok doesn’t care if you’re popular.Whereas Instagram can feel like a meadow overgrown with Momfluencer Clones (duck—wide-brimmed hat!), TikTok is more like a house party with witty and intelligent conversation in every corner. This app, created with the singular focus of easily creating lip-sync videos, has evolved into an entertainment and educational hub.

Want to hear teenagers on the spectrum talk about the misconceptions about autism? TikTok’s got that. Want to see a sneaker artist transform a pair of Air Force Ones into a masterpiece with a couple sharpies in thirty seconds? TikTok’s got that. Want to hear how to keep monogamy hot from the world’s worst attempted swinger? That’s where I come in.

I had five followers (two of my kids and three of their friends) when my first video took off. It was called My Favorite Way to Stay Not Pregnant. I stood in front of a lunar phase calendar that I used to track my menstrual cycle. I explained that we do not have intercourse around ovulation. Instead we, well … it’s sort of like Taco Tuesday … but he eats taco and I have burrito. It got 250k views in two days.

It doesn’t matter if you have zero followers. TikTok will show your video to a few people, maybe five to start. If some of those five people do not swipe away and watch at least a few seconds, you’re on your way. Then TikTok will push it out to a few more people. If any of those users watch the whole thing, watch it more than once, click like, comment, start conversations with others in the comments, share it, or click on your profile to see if you have any other great videos, the algorithm shouts “PRAISE BE” and makes plans for you to go viral.

As your video is pumped out to more accounts, the algorithm continues to assess if your video is good or if it is boring. For this reason, you cannot effectively trick TikTok into making your video go viral by asking friends to engage on it early.

How to make something good on TikTokOkay, this sounds obvious, but for a video to do well on TikTok it has to be REALLY GOOD. TikTok users are generous with their time—spending an average of 89 minutes a day on the app, but they will not think twice about swiping off your video if you do not hook them in the first second. By “second” I don’t mean quickly or somewhere in the first third of the video. I mean you have less than a literal second to grab their attention. Then you have to keep it.

If you make something entertaining or engaging it will get views. If it’s not getting views (1k–10k in the first day) think about it like you would an essay that doesn’t get picked up on the first pitch. Is it the concept or is it the execution? Usually, it’s the execution.

How would you sum up a 1,000-word essay in 30 seconds? Now tell it to me so I am on the edge of my seat. Break it into four evenly balanced sections, or strategically imbalanced sections, whatever will hold the attention, because I firmly believe the best performing videos have impeccable pacing. Now you have your first good TikTok.

Know how to use titles on TikTok.Videos do not need titles, and most users never use titles. But I think one of the reasons I’m closing in on 170k followers on TikTok is because of the way I use titles.

Reading is faster than speaking. Remember that we have less than one second to convince viewers to stick around? Well, it takes me about three seconds to announce the title of each of my videos. I’m guessing it takes most people less than a second to read it. For this reason I start every video with a face to camera shot and the title of the video.

One of my very first videos was called “How to Keep Monogamy Hot – Part 1.” I had no idea what I would make for Part 2, but titling it this way made me think quickly about the second installment, and had users clicking like crazy to my profile to see similar content.

My other regular video series are Before You Get a Divorce and How I Get My Kids to Clean the House. Additionally, I’ve done a set on Intimacy and Enneagram Types, Intimacy and Astrology Signs, Love Languages, How I Talk to My Kids About Sex, and How I Talk to My Kids about Politics.

Well, you must write a bit in the captions, right?Nope. TikTok limits captions to 100 characters, so it’s wise to fill it with hashtags.

I use hashtags not to categorize my videos, but strategically to attract my target viewer. I don’t try to target people searching for my kind of videos—I want to delight people who didn’t even know they needed my kind of videos.

Here are my usual hashtags for TikTok and the reasoning behind using them.

#fam – Fertility Awareness Method (won’t shy away from details about sex, as half of this method is saying hi to your cervix everyday)#nfp – Natural Family Planning (same as above)#enm – Ethical Non-Monogamy (practicing/curious individuals or couples, sex-positive, open to or looking for conversations about intimacy)#mykonmari – Marie Kondo tidying method (who’s tidying? Women 25–55, who’s my target reader? Women 25–55)#intimacytips, #intimacytiktok – sex positive, looking for improvement in sex life#beating50percent – Christian operation: stay married movement (many Christian couples follow me for sex advice)#marriagegoals – usually looking for something sappy or cute (then they stumble across me and are like, holy, wow, I am actually on the verge of divorce I am so grateful I found you)All video delivery is not created equal (aka you don’t need to buy friends).I’m investing a lot in Facebook ads to drive awareness of my book, and I’m using many of the same videos that have performed well on TikTok. So why are users on TikTok ten times more likely to click on a purchase button when they come to my website?

The Facebook ad is one video. Then they are asked, “Do you want to buy this book?”

On TikTok, very often users find me because one of my videos comes up on their For You Page. They watch it, click like, visit my profile, like another one of my videos every 30 seconds for five minutes, then follow me. By the time they click on my link in the bio and land on my site they feel like we’ve already hung out. We’ve enjoyed witty and intelligent conversation. Maybe they’ve even shared one of my videos with a friend.

And how would you introduce a new friend you had just met at a house party?

I’m guessing it might be something like, “You just have to meet Ashleigh. Did you know she just wrote a book?”

June 8, 2021

You Can’t Sell an Idea

“1/52 ideas” by DaNieLooP is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

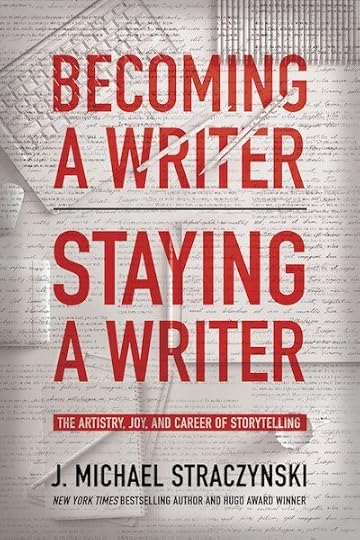

“1/52 ideas” by DaNieLooP is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0Today’s post is excerpted from the new book Becoming a Writer, Staying a Writer: The Artistry, Joy, and Career of Storytelling by New York Times bestselling author and Hugo Award winner J. Michael Straczynski (@straczynski), published by BenBella Books.

The emails come almost daily.

I’ve got this great idea for a movie/TV series/novel/short story, would you like to buy it? Tell me how I can sell it to a studio/network/publisher.

If I give you my idea and you write it we can split the money 50/50.

And one more literally from this morning:

I’m looking for someone who can work with me to package my ideas and sell them, can you help me?

No.

Because nobody wants your ideas.

(And I don’t know what package my ideas even means. Put them in a box? Staple them together? Here’s a six-pack of ideas, want ’em? They also come in twelve and sixteen packs of double-ply ideas in decorator patterns that won’t clog the pipes.)

Unless you’ve figured out a Unified Field Theory or faster-than-light travel (in which case yeah, contact me and we’ll split the money 50/50), ideas are worthless, a dime a dozen. Give ten writers the same basic idea and you’ll get back eleven stories. What matters is the execution of that idea (rather than its assassination), which is entirely a function of the person writing it.

Talent is the product of training and natural inclination focused through a unique point of view, implemented with an insane degree of dedication and the determination to strive for a level of achievement sufficient to set them apart from the crowd and lift them out of the ordinary. Lots of people can sing. Nina Simone is a one-off. Paul Simon is a one-off. Aretha Franklin is a one-off. Frank Sinatra is a one-off. Janis Joplin is a one-off. They could take songs you’ve heard a thousand times and, through their interpretation, make you hear them in ways you’d never even thought about before.

Writers are performers no less than singers; we’re just quieter. Whatever success we achieve is the direct result of how we interpret the story we wish to tell, and how well we are able to communicate that interpretation to someone else. Ideas are just the start of that process, they are not the process in toto.

Let’s say you have the most amazing idea in the history of amazing ideas. What’s a studio or publisher to do with it? They can’t publish it as is, or build a film shoot around it. Can you imagine tuning in to a TV network one evening and someone on-screen says, “We had this guy come to us yesterday with an amazing idea, check this out,” and he reads you something covering about half a page? Ideas are useless on their own terms; even if someone were to buy your idea (which they won’t because no one does), they’d still have to give the idea to another writer who could actually render that into something practicable, and whose interpretation would be so vastly different from your own that it’s no longer even the same idea, so why do they need you?

As much as we like to think we’ve come up with an idea no one’s thought of before, the odds are pretty good that whatever we’ve stumbled upon has been encountered by other writers over the long course of human history. That should not be taken to mean that there is nothing new under the sun, or that all art is just reinterpretation of what went before, justifications that are often used for plagiarism and excessive sampling. There is a profound difference between an idea, which can be, and in many cases is, generic or broadly thematic, and the expression of that idea in ways that are unique to the artist and specific to the time and culture in which it is created.

It’s the interpretation of an idea that makes it feel fresh; by the time it comes out the other end of the crazy-straw of your particular talent as a finished work, it looks like nothing that’s been done before because you haven’t been here before.

I was pursued online for years by a guy who said he had an idea for the perfect ending for a series I’d produced that never went past the first season. Even though there was no way he could have the right ending because the information needed to reach it would only have been brought out during the intervening seasons, he was adamant about getting me to read his ideas. He came at me on Facebook. I blocked him without looking at his material. He created a new account. I blocked him again. He got my email and came at me directly. I blocked him. He changed email addresses, and when my assistant intercepted his next volley, he became abusive with her.

Another individual popped up online saying that he had written a story set in one of my fictional universes and wanted me to read and give it my stamp of approval for his own personal satisfaction. Once again, I said no and blocked him. In response, he switched up accounts and came at me again. Over and over.

I’ve never read either of these pieces and will never read them, because I don’t like being stalked and bullied, and because I have the right to say no. (I suspect that guys like this, and they’re always guys, have problems with being told “no” that extend far beyond TV writers.)

And the thing is, this sort of thing has been happening for as long as I’ve been working in television. Somebody will come at me with ideas or stories set in worlds I’ve created, demanding I read them. Some can be discouraged, but others simply don’t get the message. On three occasions the stalking—online and, in one case, in person at conventions—became so virulent that I had to enlist the services of private investigators to find them. Usually it only takes making their family members (or in one circumstance, the stalker’s employer, since he was using the office computer for purposes of harassment) aware of what’s going on to trigger an intervention and make it stop. But that doesn’t make the months and dollars spent, and the emotional turmoil endured, any easier.

Writers spend their lives building careers and reputations because doing so gives us the leverage and freedom to tell stories that are personally resonant and important to us, not so that we can tell your stories. We don’t need some stranger’s ideas, we don’t want to risk being sued, and harassment is not the appropriate response to either of those preceding clauses.

Returning to the point about selling one’s ideas instead of giving them away or posting them, whenever I conduct a writing workshop there’s always at least one person who approaches me afterward to say that despite having no prior experience writing TV scripts, they’ve spent the last six months writing a pilot for a new series and do I have any advice as to how they can get it sold?

Though it pains me deeply, I have to tell them a very hard thing: that they spent those six months writing something they cannot and will not sell. Naturally, they don’t want to hear it and try to cite prior examples of people selling pilots without prior TV credits, but those stories are like unicorns, rumored and reported but never actually seen in the wild. The examples evaporate in the harsh light of web searches confirming that the person in question was either an established writer’s offspring or had at least some prior experience writing for TV.

An unproduced, inexperienced writer cannot sell a pilot. It just never happens.

Here’s why.

As noted, story ideas have no value because it all comes down to how that idea is expressed. The same applies to television, with the added caveat that whoever writes the pilot is generally the same person who goes on to run the show, and before handing over that kind of authority, the networks and studios want to understand your process as a storyteller and have a comfort factor with your experience as a producer. The only way to get that experience is to come up the ranks from freelance writer to staff writer to story editor, then on to co-producer, producer, and eventually executive producer, until you’ve finally acquired the clout needed to run your own show, and the networks have some idea of your approach to storytelling.

If that seems unfair or closed-minded, let me turn the question around: If you were boarding a flight from New York to Melbourne, who would you prefer to have at the controls: a pilot who has logged hundreds of hours of flight time on this route, or the guy who plans to start attending flight school next Thursday? The queasy feeling you just got in the pit of your stomach is exactly why there’s not a TV network or streamer on the planet that will hand you millions of dollars to make a series unless they’re absolutely confident that you won’t drive the car off the road halfway through shooting. It’s about trust as much as what’s on the page.

And the prospect of convincing a working writer/producer who does have the chops to sell a series to collaborate with you is extremely unlikely (unless that person is already a friend, but that situation can get very awkward very fast). The gift of being allowed to create a new TV series is hard won, extremely remunerative, and can be easily torpedoed if something goes wrong. If a writer/producer can sell shows on his/her own, why would they bring in a project by an unknown writer, for whom they’ll have to fight like hell to get network approval (which likely won’t come), and sacrifice 50 percent of what they’d normally earn for one of their own series, with absolutely no guarantee that you won’t blow up the entire process through inexperience?

Answer: they wouldn’t.

And they don’t.

Which is why it hasn’t happened, isn’t happening, and isn’t going to happen.

If you want to sell a TV series, start by writing for established shows and work your way up. Focus on stories that let you demonstrate your unique perspective, and take the time to learn your craft on the writing and producing sides. Gradually, as you move up the ranks, the networks and studios will get comfortable with you and your creative process. Only then will you have the opportunity to sell a pilot and run your own series.

Amazon / Bookshop

Amazon / BookshopAgain, it’s not about ideas. Ideas that lack interpretation, effort, and the willingness to put them into workable form are the currency of people with short attention spans and no discernible ability. It’s about stories, about what that idea means to you and where you want to take it, followed by all the hard work needed to transform that idea into a script or a novel or a short story.

That being said: If you’ve worked out the whole faster-than-light travel thing, seriously, call me.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out J. Michael Straczynski’s new book Becoming a Writer, Staying a Writer: The Artistry, Joy, and Career of Storytelling.

June 7, 2021

The Alchemy of Emotion: 6 Key Strategies for Emotionally Affecting Fiction

“six triangular stones” by Jos van Wunnik is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“six triangular stones” by Jos van Wunnik is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0Today’s post is by regular contributor Susan DeFreitas (@manzanitafire), an award-winning author, editor, and book coach. She offers a first 50-page review on works in progress for novelists seeking direction on their next step toward publishing.

People sometimes talk about emotion in fiction like it’s some discrete quantity you can just dial up in your prose—like perhaps if your novel is too plot-heavy, or too cerebral, you can just turn a few knobs here and there and wind up with an emotionally affecting story.

The most obvious indicators of emotion are found in scene, so this is where newer writers tend to focus in their quest, interlarding their scenes with the body language associated with emotion—the pounding hearts, the sweaty hands, the chills up the spine—along with overt statements of emotion (“walking into the meeting, he felt nervous”) and a preponderance of adverbs (“she snarled angrily”).

The body language of emotion is important—and certainly, there are times when overt statements of emotion are called for. And personally speaking, I’m not in the “no adverbs” camp (though I do think they tend to backfire in the hands of less experienced writers). But these are just the most obvious techniques for generating emotion in fiction, and relying too heavily on them tends to have the opposite of the intended effect, coming across as cartoonish, exaggerated, forced.

There are techniques that are subtler, less obvious, and they work best in tandem with one another. Because the truth is, emotion is an emergent property of fiction, a sort of alchemical magic generated by the synergy between multiple elements of the story; to create it in your fiction, you need to approach the challenge from more than one angle.

1. What’s at stake?When we talk about what’s at stake in a story, we’re talking about what the protagonist stands to gain or lose, and in stories with strong emotions, both of these possibilities hold a real emotional charge for that character.

What does your protagonist stand to gain if they achieve their goal? If it’s a large sum of money, for example, that goal will have more emotional stakes if the protagonist is on the verge of dropping out of college because she can barely afford her tuition.

And if failing to achieve that goal means not only losing that large sum of money, it means losing her scholarship to her dream college, the one her folks were so proud she got into? So much the better.

When you up the stakes in your story, you dial up the emotions involved.

2. How close is the relationship?Interpersonal conflicts are one of the hallmarks of effective fiction. But conflicts with friends matter more than conflicts with strangers; conflicts with close friends matter more than conflicts with acquaintances; and conflicts with family members tend to matter most of all.

If you find yourself struggling with how to strengthen the emotional quotient of your story, take a look at the primary relationships in it. Is there a way you can make one or more of those relationships closer?

Sometimes it’s just a matter of making a friend an old friend—one who was there for the protagonist at one of the toughest moments of her life. Maybe the neighbor lady, the one who’s dying of cancer, is actually the nanny who helped to raise the protagonist. And maybe that conversation with the old man in the park should actually be a conversation with the protagonist’s dad.

When the relationships are closer, the emotions involved tend to be stronger.

3. What’s the backstory?Backstory is a big part of the emotional power conflicts hold in a story, because it’s a big part of what those conflicts mean for the characters going through them. Backstory also helps the reader put herself in the character’s place, giving her the background info necessary to understand and sympathize with those strong emotions.

For instance: A conflict between a mother and her teen daughter will be more powerful if the mother had strong conflicts with her own mother as a girl. A conflict between two brothers will be more powerful if one of them has always dominated the other. And a conflict between two friends over a new love interest will hold a lot more charge if the one who’s fallen in love has a history of falling for abusive men.

For any given scenario, emotionally charged backstory will increase the emotional quotient—so a key strategy for generating the sort of emotion you’re looking for in any given scene or conflict is to first set up the backstory to support it.

4. What does the character say?Scene is the place where the emotions of the novel are at their strongest, but as I noted at the outset of this post, newer writers tend to rely too much on the most obvious markers of emotion here, which tends to make those emotions feel forced.

The stronger strategy with scene is to sharpen up the dialogue until the words themselves carry the charge of strong emotion, without the author having to employ a whole lot in the way of stage effects, so to speak, to alert us to the fact that the characters are feeling things.

A useful technique in this regard is to strip the scene down to just its dialogue. Can you tell what the characters are supposed to be feeling? And can you tell where the emotions shift?

If so, you can rely on that dialogue to do a lot of the heavy lifting, in terms of carrying the emotions, in a way that will be largely invisible to the reader.

5. What does the character do?A character who’s paralyzed with fear over the revelation by a family member of some long-buried secret might find herself suddenly making a wrong turn on her familiar commute to work.

A character overwhelmed with jealousy at the revelation of his best friend’s upcoming nuptials might find himself at the bottom of a bottle of bourbon on a Tuesday night.

A character whose parents have just announced they’re getting divorced might immediately book a flight home to try to talk them out of it.

As writers, it can be tempting to wax eloquent for paragraphs of summary that detail exactly what the character is feeling and why. But in keeping with the old adage “show, don’t tell,” there’s often more power in just having the character show us what they’re feeling by actually doing something.

6. What are they thinking?Finally, one of the tools I consider most central to emotion in fiction is one I think a lot of newer writers overlook, and that’s what the character is actually thinking.

Think of your actual experience of emotion, in real life. If body language is the first thing that tells us what we’re feeling, what we’re thinking tends to come next. As in “Suddenly, my face felt flushed. Why were all of these people looking at me? What had I done wrong?”

Compare that to a more overt statement of emotion: “Suddenly, my face felt flushed. I was nervous I’d done something wrong.” Not only is the POV closer in the first example, the emotion feels more vivid and real.

None of the techniques I’ve detailed here will, in and of itself, generate emotion in a story. None of these techniques will, in and of itself, cause the reader to bite her knuckle, lean forward, and maybe even feel some unexpected wetness in her eyes.

But taken together, these techniques can do just that—and that, you’ll have to admit, is magical indeed.

June 3, 2021

Strained Brain? How to Stoke Your Mental Fire

“Home” by Phil Gradwell is licensed under CC BY 2.0

“Home” by Phil Gradwell is licensed under CC BY 2.0Today’s post is by author and editor Kim Catanzarite (@kimcanrite). Her psychological thriller They Will Be Coming for Us is out now.

It happens to everyone from time to time: You’re just not too excited about being a writer anymore.

As we all know, the road to writing “success” can be a long one. One that seems, at times, never ending. Because even if you reach your goal, whatever that may be, there’s a new goal waiting for you beyond that one. A new book. A new series, article, or essay. You have to finally admit it: you’re tired.

Is that a surprise? Most people who write have a small battalion of flying objects in the air: young children to raise or elderly parents to care for or a significant other or friends who require time and attention (and nights out)—in other words, a life. We’re constantly racing to meet a self-imposed deadline, upset that we “never have enough time.” Is it any surprise that we eventually reach a point of exhaustion?

Not feeling the burnWhat I’m describing is not writer’s block (Jane’s blog). What I’m talking about has more to do with mental fire: the kind that burns when your creativity is stoked, that “can’t wait to get up in the morning” zest, the “I have the best idea for the scene I’m working on” thrill. When you’re not feeling any of that, when your writing sessions end with a sigh instead of a “that was awesome,” when you feel like you just don’t care anymore—it’s time to take a break from writing.

To some, this is a scary prospect. You might say, “But I’ve worked so hard to get in the habit of waking at 4:30 am, and if I stop now, I may never start again.”

My answer to that is very simply “Make the plan and stick to it.” That’s all. Stick to the plan. If you decide to stop writing for one solid week, if you absolutely forbid yourself to write for an entire 168 hours, you can come back refreshed and, more than that, eager to get to work, all cylinders firing. The plan is simple but powerful. And it’s only one week. But what a difference one week can make.

Diagnose yourselfDoes any of the following sound familiar?