Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 69

September 16, 2021

Succeeding with Self-Published Memoir: Q&A with Ashleigh Renard

I first met author Ashleigh Renard (@ashleigh_renard) in early 2020, when we worked together on her query and synopsis for her memoir, Swing. By April, she had signed with a literary agent, but the submissions process stalled out. By January 2021, she was working on a plan to self-publish and launch her memoir during the summer.

She has now done that—and with tremendous success. This is no small achievement for someone with a memoir. Of all the categories that one might self-publish into, memoir is probably the most challenging. There is limited demand for most memoir—unless the person is a famous historical figure, a celebrity or politician, or someone generating headlines. (The example I always use is the pilot who landed a plane in the Hudson, which did result in a published memoir shortly thereafter.)

That’s not to say there aren’t hundreds or thousands of wonderful memoirs deserving of publication each year that readers would enjoy. There is just a lot of competition. So I was delighted when Ashleigh agreed to lift the veil on her marketing and promotion for Swing, and let us know how she made the magic happen.

Jane Friedman: Unlike most self-publishing debut authors I know, you focused on pushing pre-orders and trying to build word of mouth in much the same way a traditional publisher might—which can be challenging without a publisher’s support. There are two aspects of this I’d like to explore.

First, you invested in a traditional bookstore partnership and trying to get wider bookstore community support, so that pre-orders wouldn’t be exclusively through Amazon. I believe you sent stores advance review copies along with a personal note. How did this go?

Ashleigh Renard: The near impossibility of getting a self-published book onto bookstore shelves is widely reported. It’s one of the reasons that hybrid publishers have a market, because they offer that possibility. Many self-publishing blogs encourage authors to completely put to bed the dream of seeing their title on a bookstore shelf. Amazon offers higher compensation than other POD (print on demand) options and they reward authors for cutting brick and mortar stores out of the equation. Their incentives are so convincing that pushing ebook sales (often exclusively with Kindle Unlimited) have almost become synonymous with self-publishing.

I had already begun coaching traditionally published authors on building platform and connecting directly with their readers. I appreciated what I was learning about the reciprocal relationship between authors and bookstores. My own platform was growing quickly, but just because I could go direct to consumer didn’t mean I wanted to.

Taking a bookstore-centered approach felt like the most credible way to establish myself as a debut author who was committed to learning the publishing landscape and supporting the already established community of writers and booksellers.

I couldn’t accept that bookstores wouldn’t want to make money off a book just because it was independently published. I needed to show them that customers would enthusiastically open their wallets to purchase my book.

For this reason, I did not ask any bookstores to carry it. I just asked my audience to order it.

A couple years ago, I reformed my purchasing habits and instead of relying on Prime shipping from Amazon, started pre-ordering books through my local indie, Doylestown Bookshop. Each time, I posted about it in my stories, tagging the author, bookstore, and quite often the imprint and editor (often all of these accounts would re-share my story, getting more eyes on my profile while also amplifying the endorsement of the book). I shared the reasons I was excited about the book and why preorders are important.

By the time my book was available for preorder many of my audience members had started preordering books from their favorite authors and could list off these facts:

Preorders help a publisher determine how much they will invest in marketing and publicity.Strong preorder numbers improve the likelihood that bookstores will carry the title in store.All preorders count for first week sales, giving a writer their best chance of making a bestseller list.My audience also knew that buying from independent bookstores doesn’t just support small business, but also supports authors, as those sales are more heavily weighted on the curated bestseller lists (NYT and WSJ). Strong orders through an indie bookstore make it more likely that a bookseller will take a liking to a title and display it prominently or give it cover-out rather than spine-out placement.

I polled my audience on Instagram to find out their favorite independent bookstores and I sent ARCs (advance reader copies) to those stores. I chose these stores because I knew it was most likely that these stores would also be receiving preorders. I included a handwritten card, with personalization if I could find the name of the stores’ owners, and let the store know I was educating my social media following (150k at the time, now over 300k) about the importance of preorders and supporting independent booksellers.

My local indie had over 600 preorders because they agreed to be the exclusive retailer for signed copies. McNally Robinson in Winnipeg (where I went to university) also got a ton of orders, enough for my book to hit #1 on the McNally Robinson Winnipeg bestsellers list, beating out fellow Canadian author Dr. Jen Gunter’s The Menopause Manifesto (we shared a pub day), the same week Dr. Gunter made the New York Times list. McNally stocked my title in their stores across Canada and placed several reorder shipments.

You also had an interesting audiobook giveaway strategy that helped support the pre-order. Would you describe the reasoning behind this and how well it worked for you? Well enough to do it again?

I have been a performer (figure skater) and coached performers (coach and choreographer) for most of my life—also, my audience loves my video content—so narrating my own audiobook was an easy decision. My priority throughout the process was maximum print sales, not maximum profits. I was willing to give my audiobook away for free to anyone who preordered the print.

In order to get the audiobook link, readers had to send their screenshot to my assistant. Preorder numbers do not show up until about ten days before pub day, so the steady stream of emails with proof of purchase helped me gauge the effectiveness of my promotional endeavors. Bonus: Many people listening to the book in advance made the early reviews roll in quickly on Goodreads.

About a month before pub day I posted a funny video where I listed the reasons I love my Hitachi Wand (a bedroom electronic). My audience went so wild with questions that I decided I would give away a wand a day until my book released. Preorders from each day would be considered for entry. It led to a steady stream of orders. For many who were on the fence about ordering, it was a fun incentive to just buy.

Your book hit the top 10 IngramSpark bestseller list when it released, and I believe IngramSpark reached out to you. Have they been helpful or supportive in getting the book more placement or sales?

This took me completely by surprise. A week before my pub day I got a phone call from an IngramSpark representative, indicating my title was “exploding” and they wanted to move it into their wholesale distribution pipeline.

Every Friday, Ingram sales reps have a virtual meeting with booksellers from across the world. There is a “Hot New Titles” segment where the Ingram reps make booksellers aware of titles that are selling well and that their customers may soon be asking for. Ingram wanted to include my title in this initiative.

He and I took a look at my website and social media profiles to make sure they were “bookstore friendly,” which basically means linking many purchasing choices, not just Amazon. This was easy, as I had already been educating my audience on this for so long. I put together some materials, my website link, social media profile links, and a handful of videos I had made educating about ways to support authors and bookstores and he shared them with the sales team.

I don’t know for certain how many sales or orders this resulted in, but I do know some friends who ordered through established independent bookstores and received an update email letting them know the book would not be fulfilled by a warehouse, but rather fulfilled in store.

You’ve successfully used TikTok and Instagram in particular to reach your audience. How much of your sales would you credit to your own social media content and engagement with people? Is this the engine that’s driving it all?

My engagement on social media is the engine that’s driving it all—not just because my audience is big, but because I am incredibly attentive to them. I respond to every message and have an average of 80 conversations going in my DMs (direct messages) each day. I feel like I’ve hand sold every single book, either through responding to DMs, comments, or questions on livestreams.

When people come into my DMs saying they found my videos really helpful for shifting their perspective in their relationship or that watching them has opened up a new conversation with their partner, I listen like they are already my friend, because I can often tell they don’t know who else they can talk to without judgment. When they ask for more advice that I haven’t covered or only skimmed in my videos, I’ll tell them they can find more detail in the book. This has led to countless couples reading it together—something I never expected.

You paid for some advertising on social media. How much did you invest (if you’re open to saying)? Did it work? Are you still advertising?

For several weeks I forgot I was launching a book and behaved like a PhD student studying “The Engagement and Conversion Likelihood of Women 25–55 Years Old across Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, and Pinterest Ads.” I spent 8–12 hours a day analyzing every metric I could grab—and Jane, my goodness, there are so many damn metrics. I tested different ad creative, static images vs videos, multiple landing pages, whether I mentioned the book at the outset or let them “find” the book themselves a few steps in, what difference was made if I sent them directly to an online retailer or to my website to get to know me better. If an ad platform was performing well, like Pinterest and Snapchat consistently did, I upped my daily spend to see the increase in book sales, then matched that spend on the other advertising platforms so I could test my hypotheses for why those others were not leading to sales.

I considered the investment to mostly be about my own education—I didn’t just want to learn what worked, I wanted to learn why and why not so I could help other writers make advertising decisions. I advertised heavily ($1,000 per day) for a few weeks before launch and a few weeks after. I then stopped all advertising to see if I could move the needle on sales by simply posting great content on Instagram and TikTok and my sales climbed to their highest point.

So far you have more than 250 ratings on Amazon and close to 400 ratings on Goodreads. Did you have to work particularly hard to get that many? Any secrets to share?

Getting reviews was the easiest part of this process. I think there are two reasons for this. First, I show up for my audience every day and they truly value me sharing my time with them. They know I have a ton of conversations going in my DMs and am still quick to respond. When I ask them to do me a favor, like request the book from their library or leave a review, they jump on it.

Second, they consistently see me shouting out other writers and mentioning that I am leaving a review for a fellow author. I model how to support authors I love all the time, so when the time came they knew how to support me.

So … the big question: can you tell us your sales so far?

I am about to hit 10,000 sales, with 80% paperback and 20% ebook. I think the high print sales can be explained by two things: I chose to price the ebook at the same price as the paperback, and because my audience wanted to post about my book and print books have a nicer aesthetic than ebooks.

Is there anything that you’ve stopped doing to market and promote?

I’ve found that organic reach and word of mouth are driving the sales, so I’ve stopped all paid advertising and giveaways.

Is there something you wish you’d started doing sooner?

I wished I would have trusted that showing up with a genuine desire to support people and a curiosity to learn would bloom into a community and a purpose and even provide financially—that the incredible conversation I had with one person a day was enough, even when my followers didn’t grow.

I worked really hard on social media for years, with super slow growth, and I wondered what hacks or strategies I needed to employ to connect with more people. What I didn’t realize was that the people I was watching grow were buying followers and likes. I was comparing myself to something that wasn’t real.

It’s not about building a feed that looks good, it’s about creating and connecting in a way that feels good, that fills me up rather than stressing me out.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed Ashleigh’s insights, then you should know she is the co-host of The Writers’ Bridge biweekly Zoom Q&A for writers looking to build their platforms. You can find her on Instagram at @ashleighrenard. Join her on Sept. 22 in partnership with Lounge Writers for the online class How to Sell Books on TikTok, No Dancing Required.

September 15, 2021

Why and How I Got My Rights Back from HarperCollins

“lets start over” by lonely radio is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

“lets start over” by lonely radio is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0Today’s post is by author, journalist and entrepreneur Anna David (@annabdavid), founder of Launch Pad Publishing.

When I sold my first book, Party Girl, to the ReganBooks division of HarperCollins in 2005, I thought I’d won the book lottery. Judith Regan was the rainmaker—so successful at making her authors successful that she’d actually become famous for it.

After the acquisition, the dream continued. I had exciting, glamorous lunches with Regan executives who were so important that they had assistants that came to the lunches (a move, my then-agent told me, was “classy”). My editor thought we should try to sell a reality show about me. Judith thought I should be featured on the cover—an idea she shared with me several hours before she was fired.

Because that’s what happened to the woman allegedly responsible for half the revenue of HarperCollins: suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere (depending on your point of view), she was unceremoniously dismissed in December 2006, and the ReganBooks imprint immediately dissolved.

Ignorant to the ways of publishing, I thought my book would still be a runaway success. Party Girl was scheduled to come out the following May and the New York Post, New York Daily News, Cosmo and Redbook were all scheduled to cover the book. The Today Show had booked me for an appearance the week of release and CAA was already fielding inquiries for the film rights.

But publicity and buzz, I learned, doesn’t sell books. Publishers sell books. More specifically, publisher support sells books.

I had no publisher support because I had no publisher. ReganBooks no longer existed, so I was put under the William Morrow imprint. Authors talk about being orphaned when their editor leaves for another house; this was like being orphaned and then having the orphanage burned to the ground, leaving chaos in its wake.

The cover decisions were messy. The first cover was, in a word, terrible. No one asked my opinion but luckily the team in charge of things agreed with me because it was abandoned for a less terrible one. But the first, really terrible one was sent out to the press so most of the coverage showed the wrong cover.

In the 14 years since then, I’ve published four more books with Harper, one with Simon & Schuster that became a New York Times bestseller and a few more with indie presses. Through that process, I’ve discovered what a rube I was.

But my true publishing education has occurred since founding my own hybrid publishing company three years ago.

It’s through this process that I’ve truly learned all the things my traditional publishers never told me—things that seem to be key to a book’s success. About, say, getting the author’s opinion on the cover. About advance reader teams. About effective book descriptions. About bulk orders. About keywords and categories. Oh, and speaking of categories, HarperCollins categorized Party Girl on Amazon as “Humorous Science Fiction.” While I’d agree that the book is funny, it’s a novel about a girl getting sober but having to fake being wild; in other words, it is in no way science fiction.

When “Quit Lit” started becoming a “thing” a few years ago, it occurred to me that I could republish the book. Last year, when it began to look like the Party Girl movie, after numerous options, would finally get made, I decided I wanted to republish the book under my own imprint. The book was over a decade old and out of print. It had barely been released. How hard could getting the rights back be?

Turns out, harder than you might think. My lawyer told me that because the book was out of print, the rights had officially reverted back to me but because of how the contract had been written, it would be a lot “cleaner” if I received written confirmation from Harper.

And so, in August 2020, he wrote the legal department of Harper a formal request for the reversion of rights, asking for a written response within four months. Four months later, nada.

I got my agent involved. She wrote Harper over and over. And over. Eventually, a woman at Harper named Helen responded that my lawyer’s letter had never been received, despite the fact that it had been sent registered mail. Helen promised they would discuss Party Girl at their next “reversion meeting.” The following month Helen said the decision had been postponed another month.

And then, just when I’d reached the point where I was going to go ahead and republish the book without their permission, I received a letter from Helen telling me that I could have my rights back so long as I didn’t use Harper’s layout or cover. No problem, Helen!

I’m now getting ready to launch my first baby the way I wanted it launched in the first place. I’m sure there will be numerous frustrations, disappointments and annoyances I’ll want to complain about. At least this time I’ll know where I can find the publisher.

September 14, 2021

Want to Win NaNoWriMo? The Secret Is Preparation

Today’s post is by author, editor, and book coach Julie Artz (@julieartz), who’s currently running a free 12 Weeks to a NaNo Win email course.

The first time I signed up for National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo), I failed. The story idea I’d come up with on October 31 ran out of steam after about 20,000 words and so did I. So I came back the next year ready to learn from my mistakes and get that coveted first NaNoWriMo “win.” Here’s what I did.

First, redefine winningI don’t really like the term “win” when it comes to NaNoWriMo because anything writers do to cultivate a regular creativity practice is a win, even if they don’t write 50,000 words in a single month. And I’ve heard many in the writing community admit that setting such a lofty goal actually creates feelings of failure in an already fraught industry.

So redefine what it means to win NaNoWriMo right now. Do you want to write every day in November? Do you want to write 25,000 words? Do you want to sketch out the bare bones of your new story? Whatever your goal, make it something that you can reasonably achieve given the demands on your time.

Set yourself up for successEven if you set a lower-than-50,000-words goal for November, there are still non-writing things you can do to help set yourself up for success. Consider whether you can:

Stock your fridge and freezer with quick, easy, nourishing meals that will free up cooking time in November. I love this set of make-ahead meals from The Kitchn.If you share responsibility for groceries, meal-prep, or other household chores, bargain with other members of your household—can you pick up more in October so that they can give you a break in November?Set expectations with family and friends that you will be spending the bulk of your free-time in November writing. Creating a sign for your office or bedroom door might help remind them to stay out when you’re writing.Reschedule any non-critical appointments for either before or after November. No need to spend writing time at the dentist!In addition to preplanning some meals, stock up on your favorite snacks and beverages. Don’t be afraid to reward yourself with your favorite sweet as you achieve milestones. It really does help!Panster —> Planster —> PlannerListen, I’m a reformed pantser. I only had the vaguest idea of a premise when I first sat down to write that failed contemporary women’s fiction novel in 2012. The reason I came back and won in 2013 was less about will power or caffeine intake and more about doing a little planning in advance.

That doesn’t mean you can only do NaNo if you’ve created a 52-page outline and detailed character sketches. In fact, I never do that, even when I’m drafting outside of NaNo. But spending time priming the pump with ideas during September and October—sometimes called #plantober on social media—can help you get off to a good start on November 1.

Here are some things I like to think about in advance:

Comp titles and genres and mashups (oh my!)Reading widely in your genre and age category is the best investment you can make in your writing. The last thing you want to do is waste November writing time dithering about whether you want to include a witch or a gumshoe detective or a murderous villain (or all three). Get familiar with the tropes for your chosen genre, including deciding how you’d like to reinforce or subvert them, before November comes and panic sets in.

The beginning of an arc: character motivationIf you were only going to read one craft book before or during NaNoWriMo, I would recommend Lisa Cron’s Story Genius (although I’ve recommended a great book on revision toward the end of this article as well for post-NaNo reading!). It digs deep into how a character’s backstory, desires, and misbeliefs about the world influence the actions they take as their story unravels.

That character motivation is often the first hint of the character’s ultimate change arc during the story. For more information on the strengths and challenges of starting with character, see Susan DeFreitas’s article.

The five-line outlineAlthough I definitely lean toward character-driven writing, I know it doesn’t work for all writers. That’s why I recommend creating at least a high-level outline before you begin NaNoWriMo. Here’s a technique I use with my planning-averse clients to get them thinking about plot without getting bogged down in an endless outline.

First, describe your story in three parts, beginning, middle, and end.

Your three parts are probably something like this:

Once upon a time. (Ordinary world)But then this happened. (Story Problem)And they all lived happily ever after. (Resolution)What if you added two more parts to your three-line story?

Ordinary WorldBut then (moment everything changed — story setup)…It was awful until (confrontation)…Then the hero figured it out (climax)…And they all lived happily ever after (resolution)See if you can map out these five major story beats. If you know more than five, by all means jot them down. But try to at least get five down on paper.

Learn to turn off the internal editor…Even if you spend hours and hours working on your character arc and plot points, one of the key techniques for NaNoWriMo success is learning to turn off the internal editor. That not only means just continuing to write forward even if you know you’re going to have to change something in revision, but it means being flexible enough to realize when you need to make changes to the planning you did prior to November 1.

…and explore your story idea with abandonBecause what you’re ultimately trying to do is explore a story idea with maximum creativity, minimal doubt, and total abandon. That means it should be fun, exhilarating, challenging, and new. Not a chore. And not punishment for not doing more planning in advance. That’s your internal critic talking. Kindly escort him off the premises.

Creating a routineEven with all this great planning in place, writing every day for a month can be exhausting, especially if you’re not already in the habit. Each time I’ve done NaNo, I’ve produced significantly more wordcount per hour toward the end of the month than I did in the beginning because creativity is a muscle that strengthens with practice.

To make sure you’re getting that practice every day, consider setting aside a window of time at the same time every day to write. Regardless of your time zone, there’s usually some activity on #5amwritersclub on Twitter, and writing with a virtual friend can help you keep to your routine. And the @NaNoWordSprints account hosts regular get-togethers if having community around you is motivating.

I also like to use sensory input to help get me into the right mindset. I put my favorite essential oil blend in the diffuser, make myself a pot of tea, and sit with the same window view for each writing session. I’m too easily distracted for music, but many writers enjoy either white noise or a set soundtrack to give them an auditory cue that it’s time to write.

First draft does not equal “query ready”Many agents and editors tell horror stories about the unedited first drafts that end up in their inboxes in the month of December because of NaNoWriMo. Don’t be that writer. Understand that even if this isn’t your first novel or your first NaNo, whatever you finish in the month of November is far from query-ready.

I love Cheryl Klein’s Bookmapping technique as a way of reverse outlining and assessing your plot and character arcs after a draft has been completed and recommend you check out The Magic Words from the library or your local indie bookseller if you’re struggling to know what to do next. Cheryl shared a sample Bookmap on her website for reference as well.

Have you ever fast-drafted a novel? What tips do you have to share? I’d love to hear them in the comments.

September 13, 2021

Why Write This Book?

Photo by Polina Zimmerman from Pexels

Photo by Polina Zimmerman from PexelsToday’s post is excerpted from Blueprint for a Book: Build Your Novel From the Inside Out by Jennie Nash (@jennienash). Join her on Sept. 22 for the online class The Inside Outline.

In 2013, Pixar storyboard artist Emma Coats wrote down the rules for storytelling she learned while working at the legendary animation studio. I especially love Rule #14. It’s not actually a rule at all, but a question:

Why must you tell THIS story? What’s the belief burning within you that your story feeds off of? That’s the heart of it.

If you’re like most writers, your story has been haunting you for quite some time. It keeps you up at night. It nags at you when you are reading other people’s stories. It pops into your head at times when it is least welcome. It wants to be told.

It can be extremely useful to know why you think it’s haunting you. There is probably some clue in your answer that holds the key to your whole story.

Why yes, I’m referencing Simon SinekI start with why because of Simon Sinek’s mega-selling business book, Start With Why. I have learned an enormous amount about coaching writers from reading business books, and this one is at the top of the list. If you haven’t read it, do it now. If you’re not really going to read it, then listen to Simon Sinek’s TED talk on how great leaders inspire action. It’s 18 minutes long, but even if you only listen to the first six minutes, you’ll get it, because his message is crystal clear: “People don’t buy what you do; people buy why you do it.”

In other words, it’s not enough to create a product that people might want to buy, or a book that readers might want to read. Your story has to spring from a deep conviction on your part, or it risks not resonating with the readers you want to captivate.

So all this work you’re going to do on what your book will be? It actually all hinges on why you want to write it—on why it is haunting you, or why you care. If you can articulate that, it will give your story all kinds of power. Your readers will be able to feel the why.

I actually believe that not knowing the answer to why is one of the things that holds a lot of writers back. They know they like to write, they know they’re good at it, they know they have a story to tell, but they don’t know why it matters to them or what, exactly, it means to them. As a result, they write a book that doesn’t ever really get down to anything real and raw and authentic. They write pages that skate along the surface of things. And if there’s one thing readers don’t need, it’s to skate along the surface of things. That’s what social media is for.

I can already hear you protesting that a book is not a product, not a commodity. So let me ask: do you want strangers to read your book? If so, you have to write a book people will want to buy. Even before we talk about dollars and cents, we want agents, editors, and readers to buy that we have something to say worth listening to. What that means is that we want our story to be generous and alive—and that requires knowing your why.

Knowing your “why” is going deepListen to what literary agent Ann Rittenberg says about generosity in a speech she gave at Bennington College in 2002. I have been referencing this speech for almost twenty years, because it gets so precisely at why you need to know your why:

.ugb-2a723ff-wrapper.ugb-container__wrapper{background-color:rgba(142,209,252,0.2) !important}.ugb-2a723ff-wrapper.ugb-container__wrapper:before{background-color:#8ed1fc !important}.ugb-2a723ff-content-wrapper > h1,.ugb-2a723ff-content-wrapper > h2,.ugb-2a723ff-content-wrapper > h3,.ugb-2a723ff-content-wrapper > h4,.ugb-2a723ff-content-wrapper > h5,.ugb-2a723ff-content-wrapper > h6{color:#222222}.ugb-2a723ff-content-wrapper > p,.ugb-2a723ff-content-wrapper > ol li,.ugb-2a723ff-content-wrapper > ul li{color:#222222}What kind of writer can make characters [you care about]? I think the kind of writer who is not afraid to access the deepest places in himself and is not afraid to share what he comes up with. Such a writer can set those discoveries down on a page without interference from an internal tribunal. I’m sure you all have some kind of internal tribunal. It might be one voice, or it might be many, but it’s the thing that says, “You can’t do that. That’s insignificant. That doesn’t make any sense. Do you have any idea what you’re doing?”

I have a client whose writing I absolutely love, the way I love the writing of all my clients. I’ve gotten to know her well in the dozen or so years we’ve worked together, and I once told her she had no skin between herself and the outside world. Such a condition can make daily life painful, but it can also make for wonderfully particular, wonderfully alive writing. It’s writing that’s stripped bare of the kind of chatty filler that makes the writer feel more secure, that assuages the writer’s fear of what she’s seen in those deep recesses. Every sentence is pointed, to the point, a working part of the whole machine.

I see plenty of writing that has kernels of good in it, but it’s hedged around with so much tentativeness or uncertainty or excess or stinginess, that it doesn’t allow the outsider—the reader—in. It doesn’t reveal the character. And if I can’t find a chink in the wall, I know that the agent/author relationship isn’t going to be successful.

Yet when I read something that speaks to me, that absorbs me, that remains vividly in my head even when I’m not reading it, I’ve been intimate with the person who wrote it before I’ve even met him. This isn’t to say I know anything about him. I only know he or she is the kind of writer who’s willing to explore the deep essence of character….

You can see why the concept of authenticity and generosity of spirit is so important to writing fiction, so the very first thing to do is to get honest with yourself about your why. Dig deep and write one page on why you must write this book. What does it mean to you? Why does it matter? Why do you care?

Amazon / Bookshop

Amazon / BookshopNote that asking why you must write this book is different from asking why you are writing a book or what you want from the experience. Your motivation probably has to do with any number of things—fame, money, leaving a legacy, or proving to yourself or someone else that you can do it. Writers want to write! We want to raise our voice and be heard! We want to make an impact on readers the way writers have impacted us. The vast number of writers I work with say that they want to write a book before they die. It’s often a thing they have dreamed about doing since they were very young. These are powerful and important motivations, and I am all for knowing the answer to these questions—what you want out of writing a book, what your goal is, what you would consider success.

But for the Blueprint, we are talking about the why for this particular story. Why do you want to write this specific book? Why do you care? Because if you know why you care, your readers will get it, too.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, please join Jennie on Sept. 22 for the online class The Inside Outline.

September 9, 2021

Choosing a Publicist (Again): Assessing Your Changing Needs

Photo by Mikhail Nilov from Pexels

Photo by Mikhail Nilov from PexelsToday’s post is by author Barbara Linn Probst. On Sept. 17, she’s teaching an online class in partnership with me, Hybrid Publishing 101.

Should I hire publicist?

How can I choose a good one?

Is it worth it?

These are questions that many new authors ask, regardless of their path to publication. I did too. In fact, a year before the launch of my debut novel, I wrote an article that offered guidelines for choosing a publicist, with an emphasis on personal fit, based on factors like temperament, communication style, and how involved you like to be.

The 2019 essay grew out of my own experience selecting a publicist for my first novel, Queen of the Owls. The choice I made was perfect for my needs at the time. I wanted impressive announcements to share on social media—national hits that would enhance my bio, build credibility, and gain followers. I understood the warning that all publicists issue, if they’re candid: “Publicity is not sales. Publicity is buzz.” That was fine with me. I wanted buzz, and I got buzz.

Two and a half years later, however, as I look to publication of my third novel in fall 2022, I’m in a different place. That realization has come to me gradually, since it’s natural to assume that one ought to keep doing what’s worked. But the situation can change, and I had to stop and examine what I need and want now.

A major difference between spring 2019 and fall 2022 is that I now have experience to draw on. Although every book has to be viewed in context, and it’s tricky to apply “lessons learned” from one launch to the next, there is still a qualitative difference between no experience and some experience. As a third-time author, I have a better sense of what to expect. I also know what didn’t feel “worth it” to me, personally, and what did.

Since I’m no longer a debut author, it means that my forthcoming book is not a debut novel. This may sound like two different ways of saying the same thing, but it’s not.

A debut author is a greenhorn, dependent on the advice of others—and thus at a disadvantage.

A debut novel is a mysterious package—which can be an advantage.

A first novel will attract attention, precisely because it’s unknown.There’s a sense of curiosity, of limitless possibility, of uncovering something that might turn out to be important. A second, third, or fourth book doesn’t typically have that mystique. On the other hand, there may be a ready-made audience of readers who’ve enjoyed the author’s previous books.

With a debut, you’re announcing your arrival as a writer, and you want the world to know. For that reason, it might make sense to go big and spend big on a first novel. You might want to cast your net as widely as possible and test a range of waters, since it’s hard to know where a cache of interest may lie. You might also want to collect some stellar media hits that will always be part of your track record and can be incorporated into the “praise sheets” and press releases for future books, as well as permanent fixtures on your website.

For a later novel, a different marketing strategy might make more sense.You might want something more targeted and strategic, aiming at sales rather than buzz. That could mean allocating a larger portion of your resources to “hard” marketing (that is, paid advertising) rather than “soft” publicity, or narrowing your outreach according to geography or demographics—or simply spending less because there are things you’ve learned to do yourself or have decided you don’t need.

The best way to figure out which PR firm, package, or combination of a la carte services will meet your present needs—e.g., if you want to hire a separate social media consultant or someone to create and manage a newsletter—is to do a forward-leaning assessment based on where you are now, as an author, and where you might be able to go next. As hockey great Wayne Gretzky is famous for saying: A good hockey player plays where the puck is. A great hockey player plays where the puck is going to be.

How to do a forward-leaning assessmentThis assessment starts from the understanding that, as a second- or third-time author, you have a history and are no longer an “unknown voice” for whom all things are—or seem—possible.

If your first book did well, the stakes may feel higher, bringing pressure and the expectation, perhaps unrealistic, that subsequent books will garner or even surpass the kind of high-level interest that your publicist was able to secure for your debut. You may be fearful of making any changes in what seemed to work, even if the strategies used for your debut are no longer be the most appropriate.

In contrast, if your first launch felt disappointing, there can be pressure of another kind—a doubling-down of the stakes, leading to a “grass is greener” hope that a new publicist will deliver the kind of high-level results that the first one did not.

Both attitudes have their pitfalls. There’s no general principle about the merits of staying with the same publicist (consistency of relationships and approach) versus changing publicists (a fresh perspective)—and there can’t be, given all the factors such as timing, context, genre, budget, turnover, and availability.

All that can really be said is that your goals, as an author, will likely be different over the course of your career, and thus the strategies for achieving those goals may be different. Strategies and strategists are not the same thing. It is certainly feasible to switch strategies while utilizing the same publicist.

At the same time, any new arrangement, by definition, will be unknown. It’s natural to wonder if it’s worth the risk. That’s why the process has to be undertaken thoughtfully, beginning with a realistic self-assessment.

Here is a four-step approach that can help you identify your needs and goals—which, in turn, will help you find a publicity firm or combination of services that can help you achieve them.

Prioritize your goals for this particular book—just the goals that are reasonably achievable right now, not your long-term goals. It’s helpful if there are one or two goals that are more important to you than the others. For example: Is your priority securing reviews in top-tier media, getting into libraries, making it onto those “best of” lists, reaching a particular community, selling a lot of books even at a discounted price?Make a list of marketing and publicity strategies you are most interested in. You might want to color-code them. For example: blue for those you found to be effective in the past, red for those you never or barely tried but find intriguing, green for those you’re on the fence about due to cost or other factors.Place your two lists side-by-side and (literally) map out the likely relationships. For example: if one of the strategies you want to utilize is “podcasts,” draw a line from podcasts to the goals that podcasts might help you achieve. Reaching a particular community—yes. Getting reviewed by Booklist and Library Journal—no.Examine the density of connections, and circle the strategies that offer the highest potential for helping you reach your top two goals. These are the strategies you want to use. That means you need to look for people or services that can provide them. Forgo the bucket-list items that would give you the greatest thrill but are unlikely to contribute to your goals. Be a pragmatist.Here’s the tough partYou might have a publicist you feel loyal to and guilty about “abandoning.” There might be a publicist your friends swear by, who seems to have achieved enviable results for them, or one whose high-profile client list you’re longing to join. But are any of them the right fit for you, at this particular time, with this particular book?

Perhaps you can stay with your current publicist, but renegotiate your arrangement. Can you use her for certain things, while outsourcing some of the services you now want that she can’t provide? Or do you need to thank her for her help and move on?

This attitude is likely to feel different from the one you had as a brand-new author who didn’t really know what she needed. Born of experience, it is more collaborative and empowered. Choosing a publicist for a second or third book, even if you end up re-choosing the same person you used before, is a choice based on knowledge, not just on hope.

To return to the questions at the beginning of this essay: Should I hire publicist? How can I choose a good one? Is it worth it?

“Should” and “worth it” are personal judgments that can only be assessed in relation to your aims and resources (e.g., time and money), as well as the larger context in which you are publishing. What others have done might not be relevant; as I’ve tried to indicate, what you did earlier might not be relevant either. Among the questions to ask yourself now:

What can you do yourself to promote your book (without paying someone else to do it), and do you want to?Are you willing to spend more than you’re likely to make in royalties for the sake of a long-term aim?For a second- or third-time author: do you feel differently about this book (or yourself as a writer) than you did about your previous book/s?How comfortable are you with risk and change?As with everything in the world of publishing, there is no formula. Sometimes we grab on and sometimes we let go. We make the best choices we can—remembering that what we really want, at heart, is to reach people with our words and offer something that matters.

September 7, 2021

How to Turn Trolling Into a Fine Art

Illustration by Javier Olivares

Illustration by Javier OlivaresToday’s post is excerpted from Catherine Baab-Muguira’s Poe for Your Problems: Uncommon Advice from History’s Least Likely Self-Help Guru, published by Running Press.

From his earliest days on the Southern Literary Messenger, Edgar Allan Poe reviewed books the way Jack Torrance swung an axe.

Take Norman Leslie, a novel written by Theodore Sedgewick Fay, a popular associate editor at the New York Mirror, which was then one of the most respected publications in the country. Poe didn’t give a damn. In his 1835 review, he screamed that Fay’s style was “unworthy of a school-boy,” the larger novel “full to the brim of absurdities,” “gross errors in Grammar,” and “egregious sins against common-sense.” In a subsequent article, Poe struck again, labeling Norman Leslie “the silliest book in the world.”

These attacks did not go unanswered. The staff of the Mirror swung back, gleefully informing their far-reaching audience that Poe’s own work had been turned down by Fay’s publisher and sneering at the Messenger for “striving to gain notoriety by the loudness of its abuse.” Other magazines joined in, too, calling Poe a quack, a jumped-up faux expert who couldn’t, were there a gun to his head, produce one good page himself.

This was the exact fight Poe had been seeking, and—more or less—for the reasons his enemies identified. He didn’t care how his nasty reviews unnerved his Messenger boss, T. W. White. Instead of backing off, he doubled down.

Over the next fifteen years of his career, Poe’s criticism remained so caustic and hostile that one victim would characterize it as “generally a tissue of coarse personal abuse.” Poe leaped between professional and personal grievances, then back again, not only inveighing against bad writing, but heaping scorn on people whom he disliked. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, another of Poe’s victims, observed: “The harshness of his criticisms, I have never attributed to anything but the irritation of a sensitive nature, chafed by some indefinite sense of wrong.”

He would know. Poe initiated his “Longfellow War” in 1845, first in the pages of the Mirror, and later in the Broadway Journal. To hear Poe tell it, Longfellow was a dastardly plagiarist: a plagiarist so devious and prolific that his plagiarisms could hardly be detected, so rife was the plagiarism, so deep did the plagiarism lie. Equally as bad, Longfellow also had a rich wife, and what appeared to be a serene family life, and a professorship at Harvard. What a jerk!

And Poe still wasn’t done.

In 1846, as a freelancer once again after the Broadway Journal collapsed, he began publishing his critical coup de grâce: a series of articles for a ladies’ magazine that amounted to a literary-world burn book à la Mean Girls.

In “The Literati of New York City,” he profiled several dozen of the writers he’d known and or just brushed wings with during his high-flying, “Raven”-fame days in Manhattan, not limiting himself to throwing shade on their work, but also repeating gossip and inserting lengthy comments about these writers’ height and weight, posture, facial features (the size of their noses, the shapes of their mouths, etc.), education (or, as he said, their appalling lack thereof), family backgrounds, intimate relationships, even his best guess at the current balance of their bank accounts.

Incredibly, some of those Poe covered so ruthlessly were friends, former colleagues—in other words, people who might still have done him favors, and this at a time when he was as about as poor as he’d ever been. When he was unemployed, unwell himself, and when his beloved wife, Virginia, was desperately sick. In fact, dying.

Such behavior may seem out of bounds, even morally revolting. And it is.

Frankly speaking, from this vantage point in history, it’s hard to see how Poe’s unfiltered criticism was a great use of his time, except to the extent that it brought him notoriety, attracting the nineteenth-century equivalent of clicks and eyeballs. I hate that it’s true, and I expect you do, too, yet trolling—the practice of deliberately provoking others in order to elicit an outsized reaction, whether through an 1840s magazine profile or the modern-day internet—is a powerful method of personal PR. A veritable dark art.

Just like us, Poe lived in a chaotic, explosive information age, and he faced the same set of problems about how to stand out amidst a constant torrent of content. To use an oversimplified example: Say you want to create a thriving YouTube channel. Helpfully, the means of video production and distribution have now been democratized, making such a path accessible at all.

At the same time, you’re competing with millions of other people with the same goal. You can’t possibly keep track of all the other content being created, while cultural trends and even whole platforms emerge and disappear with terrifying speed. Producing your videos may take days or weeks. Monetizing those videos and building your audience, however, may take years.

It doesn’t matter if you’re a YouTuber, a writer, a singer-songwriter, a comedian, or trying to establish yourself in any other field. Standing out is a near-impossible task, and you could be forgiven for trying to find ways of gaming the system—of hacking other people’s attention spans so you come to public attention, fast.

Two roads diverge before you. On the left is the Tom Hanks High Road, the virtuous route. You can be polite, even-handed, self-effacing, supportive of others, and here to make friends along the journey. Good luck.

On the right, there is the iconoclast’s path, which you will walk alone.

You can, like Poe, pose like a fearless truth-teller while letting your aggrieved psychology, your envy of those more successful, and your profound unhappiness with yourself and the world hold sway. You can seek the kind of world-leveling vengeance that Poe sought, at the same time taking advantage of the way human brains are wired to home in on threats and negative statements. Even toddlers understand that “bad” attention is still attention.

You can mine this primitive vein by being pissy, antagonistic, combative, impossible to please or placate, always operating in bad faith. If you choose this path, other people may hate you, and they may be right to.

What’s more, in strictly practical terms, this route is arguably far more crowded today than it was in Poe’s era, and even then, Poe’s peers could readily recognize and name his method. Exceptional harshness is now just as likely to work against you as for you: Users of YouTube, Twitter, and so on have necessarily learned to tune it out, given how overused and over-applied trolling has become.

What if you were to carve out a middle path?Poe’s best criticism was more than mere trolling, and Poe himself, despite some terrible tendencies, more than a mere troll. He was also a literary expert, versed in verse, classic literature, and popular forms, and his command of his field was damn near second to none, even if he occasionally cribbed or exaggerated his knowledge.

Your task is to become an expert, too. To really stand out—all the more so now as a negative presence—your criticism needs to be on point, your blows must land. You don’t want to be a one-trick show pony, sh*t-posting only, with no original insights to contribute.

What would you think of an aspiring filmmaker who’s ignorant of film history? An artist who can’t discuss her own discipline, who by choice never visits a museum? A writer who thinks reading books is a waste of his precious time?

Such attitudes are for hobbyists and posers—not pros. It’s crucial to grasp the history of your field as well as the current landscape of what you’re trying to do—a badge of honor amounting to an urgent personal responsibility.

That does not mean you must be a slave to fashion, conventional wisdom, and elitist favor-trading, or that you should automatically accept what is popular as what is good. There’s nothing wrong with having an oppositional sensibility if you also develop mastery of the material and your own models for judging new work. In this happy case, your iconoclasm is no longer a pose, and your tendency to iconoclastic overstatement may be fun for everyone involved.

Think of Kanye West or Nassim Taleb, endlessly beefing and complaining as though their careers depend on it, yet still being wildly entertaining while they’re at it, and at the same time advancing the standards by which they want their own work to be judged. [To be clear, I’m not speaking of West’s politics or his comments on vaccines.]

This is elevated trolling, trolling as a fine art. Well educated, well executed. Canny. Worthy. Frequently very funny, too.

We might call this middle way The Path of the Pain in the Ass. Trolling for its own sake, when you have no original thoughts or contributions yourself, is just a way of being mean. Aim to be more of an articulate pain, someone for whom others can feel at least a grudging respect. The game’s no fun for anyone without worthy combatants—and you will have more fun when you know what you’re talking about, too.

So, what’s the Poe tip, the takeaway?

Develop a grasp of your field’s history and cultivate your own keen critical sensibility. In other words, become a giant pain in the ass.

Amazon / Bookshop

Amazon / BookshopAnother benefit: by becoming an expert, you’ll know whom to suck up to, which is every bit as crucial as being able to call out your chosen discipline’s sacred cows. You want the people you admire to admire you, don’t you?

Poe did, too. Just as he insulted his overly successful, under-talented peers, he craftily cultivated his literary heroes—particularly Charles Dickens and Elizabeth Barrett Browning—sucking up to them privately as well as writing public paeans to their work.

In the process, he turned them into advocates for his own work. This strategy can work just as well today, for you. It costs you nothing to send a flattering, even fawning, email, while the upside of doing so may be virtually unlimited. And my email address is on my website for whenever you’re ready.

Excerpted from POE FOR YOUR PROBLEMS: Uncommon Advice from History’s Least Likely Self-Help Guru by Catherine Baab-Muguira. Copyright © 2021. Available from Running Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

September 3, 2021

I Like Substack. But the PR Is Getting Ridiculous.

I subscribe to more than 50 Substacks. I even pay for a handful. I think it’s a great platform and I recommend it often to clients. That’s not so much because I love Substack the company, but because I believe in email. And Substack, if anything, makes it easy for non-tech people to harness the power of email, whether free or paid.

I myself have published a free newsletter for a decade (Electric Speed); it now has 24,000 subscribers. In 2015, I launched a paid newsletter, The Hot Sheet, before Substack existed. I had to roll my own tech for it, which I’ve been using for six years. (I stack ChargeBee, WordPress, and Mailchimp.) The newsletter grosses about $75,000 per year. In 2022, if I put more effort into it, I’ll get into the six figures.

So I have a lot of reasons to believe the hype around Substack. But the PR and media coverage it’s getting is all out of proportion to reality. Journalists are falling for Substack’s PR machine without an ounce of critical thinking. Let’s take a look.

Serialized books are a burgeoning business at substack (Publishers Weekly)This article is about a nonfiction book traditionally published in 2014 that the author wants to revisit and re-promote. The publisher, Norton, doesn’t see sufficient benefit to releasing a new edition or designing a new cover. So to pacify the author, Norton has granted the author permission to serialize the first two chapters on Substack.

That’s it. A “burgeoning business”? No. As Guy Gonzalez tweeted, Publishers Weekly confuses a story about a traditional publisher not knowing how to market a minor backlist title into a story about Substack.

So let’s move on to the next article; this one’s about an author who is in fact serializing a new, original work.

Substack signs ex-Forbes writer as it seeks to disrupt book publishing (New York Post)Substack paid an advance to author and entertainment writer Zack O’Malley Greenburg to serialize a book, We Are All Musicians Now, on Substack. Each week a new installment drops to paid subscribers. Greenburg told the New York Post that he opted to go the “Substack route” because it offered him more financial upside, although the terms of the deal were not disclosed. He said, “All in all, with the advance money being in the same ballpark, I’d rather go to a place where I can be my own boss with a higher upside than try to force it through an old business model that I think is broken.”

The New York post headline claims that Substack seeks to “disrupt” book publishing, but later the article acknowledges that serialization isn’t a new model. In digital media, for 20 years, authors have serialized and market-tested their work on blogs, podcasts, and email newsletters; on social media sites like Twitter and Facebook; through creator platforms like Patreon, Kickstarter, and Wattpad; and even through Kindle, particularly when Amazon Publishing had a clunky serials program (nothing like Vella) in 2012.

There’s also nothing new about a startup luring a creator away from an established player with cash and/or freedom. Lots of Internet companies, established businesses, and startups have done this. Amazon. Spotify. Apple. Etc.

Most important, the market for a serialization and the market for a book are not the same. I learned that when talking to Amazon years ago about their serialization program. More than half of the revenue arose from book sales after the fact. And I’ve seen that same dynamic play out for other authors in both nonfiction and fiction. Some people like the serialization experience, and some people like books—and the overlap between the two is smaller than you might think. So I hope that Greenburg negotiated his deal carefully.

Why writers are turning down lucrative deals in favor of Substack (The Guardian)This article was written today, now that Salman Rushdie was lured in by a Substack offer. Yes, Salman Rushdie! So what will he do there? He says, “Just whatever comes into my head, it just gives me a way of saying something immediately, without mediators or gatekeepers.” (Wait, is he not on Twitter?) More formally, Rushdie says he will serialize a 35,000-word novella, and I have to wonder if his publisher refused to take it.

I find this akin to Margaret Atwood working with Wattpad some years ago. Sure, it was neat. But it did not change the fortunes of Wattpad. A bunch of A-list writers didn’t migrate over to the platform as a result. Wattpad’s business model remained the same. Is Atwood doing any work now on Wattpad? No. I doubt Rushdie will continue on Substack in any meaningful way beyond his first year.

Substack is clearly trying to spread its wings, but will it work?After getting $65 million in funding in March, Substack must be under pressure to grow. With its focus now turned to fiction as well as comics, Substack may be trying to compete with the likes of mature and developed creator-publishing platforms such as Wattpad, Tapas, or Webtoon.

But this doesn’t make a lot of sense to me, given what really stands out right now on Substack: political commentary, opinion, and various types of journalistic content. Perhaps they can honestly be called disruptors for a certain type of writer: op-ed columnists, professor-pundits, political journalists, or people in news-adjacent industries.

I’m the least surprised by its success in that realm. When I worked at the Virginia Quarterly Review (a very literary journal), I learned something critical on the first day of the job: fiction and poetry sank like a stone in terms of online traffic. Only nonfiction gained traction. Our audience simply did not read fiction online. They read books—usually print books.

Who does read fiction online, particularly on mobile devices? If you look at the established demographics of Wattpad, Tapas, and Webtoon, they’re all quite similar: young, diverse readers who consume comics, manga, graphic novels, and genre fiction. There are also sites like Radish and Royal Road (and now Vella), where you’ll find troves upon troves of genre fiction—lots of romance, science fiction and fantasy, and RPG stuff. It is possible to make money on those sites, but you are writing in established corners for established interests. It is not the same as going off to your Substack garret to pen the Great American Novel.

As far as I can tell, Substack has a different core audience than Wattpad, Webtoon or Tapas. They currently reach the type who also visit independent bookstores, probably know about LitHub and Bookshop, and prefer and maybe fetishize print. We shall see if Substack can successfully push beyond this literary type.

That brings me to Elle Griffin, a writer who has spent this past year analyzing how writers make money by publishing fiction, through her own Substack newsletter (but of course). She started a Discord server, Substack Writers Unite, where people gather to talk about how to build their author platform and get subscribers. Her work has garnered a lot of attention and sharing, as it should—it’s valuable insight for anyone who wants to know how authors today earn a living outside of the traditional publishing path. But her primary goal, as she’s made clear all along, is meant to accomplish one thing: support her paid Substack serialization of her upcoming novel.

I wish Griffin every success and I hope it works out. But so far she has established an audience for writers who want to learn how to make money writing. And that is not the same audience who reads fiction online. Sure, there could be some overlap, but it’s a well-known problem among writers that blogging about writing and becoming an expert on publishing doesn’t translate into readers for your fiction. You end up in an echo chamber.

The gritty reality for Substack’s middle class (Simon Owens)Here is an article that speaks the truth, finally. Journalist Simon Owens has been trying to achieve lift-off on his own paid newsletter effort. He harbors no ill-will toward Substack, but like me, he’s a little tired of the hype.

Many aspiring creators have this fantasy that they’ll be able to work on their newsletter as a side hustle and then quit their full-time jobs at the exact moment that the newsletter revenue replaces their full-time income.

This scenario is known to happen sometimes, but it’ll be difficult to achieve for most. Why? It all ties back to growth.

While we’d all like to say that content quality is the biggest driver of growth, the truth is that publishing consistency often plays a much bigger role. You can produce the most brilliantly-research[ed], well-written newsletters, but if you’re only publishing twice a month, you’re not going to grow very fast, at least without a large following on some other platform or a sizable marketing budget. All things being equal, a daily newsletter will grow much more quickly than a weekly newsletter, even if the daily newsletter is slightly lower in quality.

What does this mean in practice? That embarking on a newsletter career requires a leap of faith — a departure from full-time work so you can increase your content output, even though you’re not yet generating enough income to replace your salary. In other words: you need some sort of financial cushion.

For my own paid newsletter, it took me a couple years to hit what I’d call “salary replacement income.” And that was with (1) 100,000 visits to my website, (2) more than 20,000 free email newsletter subscribers, and (3) 200,000 followers on Twitter. Now that I’m six years in, I might be able to hit six figures if I put aside other work in favor of it. As of today, the majority of my income is from online classes.

None of these projects I’ve discussed here are foolish or bad—nor am I against people using Substack. I applaud innovation and experimentation. I love seeing new paths and opportunities open up for writers. But Substack is just one option among many. And let us not forget Substack is a VC-funded enterprise, just as Medium was. Remember The Atavist? Byliner? Vook? Pronoun? Oyster? No? That’s because they’re buried very deep in the graveyard of publishing “disruptors.” Keep your eyes wide open.

September 1, 2021

That Second Book: To Write, or Not to Write?

Today’s post is by Rachel Michelberg, author of the memoir Crash.

In my writing feedback group recently, I was complaining. Kvetching, my mother would say—the whiny, petulant kind of grumbling that’s really annoying for those subjected to it.

I was stuck—for blog topic inspiration, put-your-butt-in-the-chair-and-write motivation. Still well within the post-pub-honeymoon period of publishing my memoir, Crash, I had an excellent excuse so was heartily forgiven by my teacher and group-mates. It’s normal, they said. Give yourself a break. You’re in a kind of withdrawal, happens to lots of writers. (I wrote about that here.)

But it leads to a bigger, more existential question: Am I a one-hit wonder?

Not that Crash is a hit—yet—but it’s gotten a better response than I ever imagined. Is it a one-off? Or, as I’ve affirmed in so many interviews, do I really have a second book in me?

Writing a book is a herculean task. I don’t have to tell you that. This is a writer’s blog, I’m preaching to the choir here. Blood, sweat, tears, time, energy, and money—lots and lots of money. I suppose there are authors that just need a working computer, God bless them. Not me. I’ve lost track long ago of how many dollars flew out the door for classes, feedback groups, retreats, editing services. And that’s before a publisher accepted me. Since then, it’s payment for the hybrid publisher, publicist, social media coaching, contest entry fees. Yes, you have to pay to be considered for all of those book awards. Those little stickers for the book when you win? Those too.

Luckily, despite my kvetching, I’m in a comfortable financial place in my life so it’s really not about the money (though that’s always a consideration, isn’t it?). I can afford to follow my passion. But is it a passion?

I started writing Crash because I had one of those you-don’t-make-this-shit-up kind of stories, not because writing is a profession. I had no real idea what I was doing when I started. Do I really need to keep writing?

Who am I kidding? The real question is—do I, deep in my guts—my kishkes as my mother would say (don’t you just love Yiddish?), really want to write another book? Or am I feeling obligated, to please my friends and readers? Am I still that little girl wanting to make mommy and daddy proud?

No one’s pushing me. My husband would probably be relieved if I didn’t (see above, re: $$ and energy) but he’d support me. As I brood, a pro/con list emerges:

Pro: I have a career and some status as a voice and piano teacher and singer. I don’t need to prove myself or carve out an identity. Or do I?Con: $$. Knowing how I work, I couldn’t resist attending retreats, conferences, classes, etc. Ka-ching ka-ching.Con: The constant pressure. How many pages have I written today? I need to put my butt in the chair, but I don’t wanna.Pro: A great way to avoid feeling like an imposter. Calling myself an author after writing one book feels…sketchy but acceptable. Working on a second? Definitely!Pro: Feeling like a valid, relevant part of the author communities I’ve joined, not a has-been.Con: Writing fiction. My idea for book #2, historical fiction based on fact, is terrifying. For my memoir, I was there. I didn’t have to make anything up, be truly creative.Pro: Who knows? I might really enjoy the process.For now, I’ll find some contentment in my vacillation. After all, Crash took me eleven years to write, so what’s the hurry?

August 31, 2021

How to Make Six Figures Self-Publishing Children’s Books

Photo by Karolina Grabowska from Pexels

Photo by Karolina Grabowska from PexelsToday’s post is by author and indie publisher Darcy Pattison (@FictionNotes). This post has been edited and adapted from a presentation delivered at the SCBWI’s Big Five-Oh! Virtual Conference.

Let’s talk about making money as a self-publisher of children’s books.

I bet you think that I’ll start out with something like running a Kickstarter campaign. This year, I did indeed run a campaign for The Plan for the Gingerbread House, but it was my first Kickstarter campaign ever, and it was a minor project for my company.

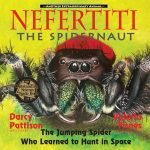

Instead, I’d like to walk you through some of the issues of self-publishing by looking at one of my books, Nefertiti: The Spidernaut, which was published on October 16, 2011.

During the summer of 2010, I heard a radio interview with Astronaut Sunita Williams, Captain U.S. Navy about a live animal experiment on the International Space Station (ISS). She was the astronaut who dealt with Nefertiti, a jumping spider who was sent to space.

Most spiders spin a web to catch food. But jumping spiders actively hunt, leaping to catch their prey. What happens when a jumping spider jumps in the microgravity of the ISS? It’ll float away. Would Nefertiti be able to adapt and hunt? Or will it die?

Williams said, “It was a suspense story for me as it happened. I didn’t know if she would survive when I unpacked her for the first time, or when I packed her up and sent her back home to Earth.”

I knew it would make a suspenseful book for kids to read, too.

Here’s the question, though: why self-publish THIS book?

It helps to publish a seriesOne reason I decided to publish Nefertiti is that I already had the makings of a successful picture book series of animal biographies.

Wisdom: The Midway Albatross won the Writer’s Digest Self-Published Award for picture books, a $1,000 prize, and subsequently received a starred Publishers Weekly review.Abayomi: The Brazilian Puma was named a 2015 National Science Teaching Association (NSTA) Outstanding Science Trade Book.Self-publishers know that publishing in a series makes a lot of sense. You don’t have to recreate the audience for each book. If a reader liked a previous book in the series, they are more likely to like this one, too.

So, I decided to publish the book.

Publish in multiple formats and distribute wideI decided early on to simultaneously publish hardcover, paperback, ebook and audiobook versions of each title. Because I use print-on-demand services, instead of offset printing, I made about the same profit on each version. I decided to let the customer decide on the format they preferred.

I also distribute widely, refusing to limit my books to any exclusive agreement. Readers can find the books wherever they are accustomed to shopping, in whatever format suits them best.

I also send books for reviews, just like any other publisher. Unfortunately, there’s a lot of discrimination in the industry about self-publishing, but I ignore all that, and my publishing company submits books anywhere the book belongs. However, sending books out for reviews is risky!

School Library Journal gave Nefertiti the worst review I’ve ever read: “Skip this bland treatment and share the news clippings instead.”

I don’t know. Maybe the reviewer’s opinion really was that the writing was bland. Perhaps she just hated spiders. Or maybe she knew this was a self-published book and slammed it for that reason. Who knows?

I was upset. But not very upset—yet. I knew the conversation wasn’t over.

Live and die by your opinionPublishers live and die by their opinions. I once talked with a Dial/Penguin editor who said that for their fall list of 25 titles, they knew that half of them wouldn’t earn out. The problem? They just didn’t know which half would perform? The professionals—the publishers with a long track record of producing children’s books—they didn’t know what would succeed and what would fail.

The editor said, “In this business, you live or die by your opinion.”

In my opinion, Nefertiti was a great book. Ultimately it was named a 2017 NSTA Outstanding Science Trade Book. One judge told me later it was his favorite book of the year.

Now, here’s what I know. If I’d been traditionally published, the book would never have won the award. First, it likely wouldn’t have been accepted for publication. Second, it would never have been submitted for that award. Traditional publishers will only submit a season’s lead book from their most popular authors. Mine wouldn’t be submitted!

My book would’ve failed because it was ignored.

The only reason it received the NSTA recognition is because I care more about my work than anyone else. I submitted. And the book did its work.

Network your way to special salesBecause Nefertiti was named an NSTA book, when I attended the Arkansas Reading Association convention later that fall, I contacted the NSTA representative to tell her I’d be attending. I stopped by her booth and visited. She recommended that I meet Emily Morgan and Karen Ansberry, who were working on Picture Perfect Science workbooks, which provided elementary teachers with lesson plans for teaching science using picture book texts.

A couple weeks later, Emily and Karen were presenting at a school district just an hour away, so I attended and stayed to eat dinner with them.

The result was that two of my books, Nefertiti (space & spiders) and Burn: Michael Faraday’s Candle (light and fire), were included in their next volume of Picture Perfect Science STEM Lessons, Grades 3-5.

I was thrilled when the NSTA decided to create a book bundle of all the books recommended in the Picture Perfect series. They ordered thousands of copies of Burn and Nefertiti to include and sell to teachers and school districts in the book bundle.

Special orders are an important addition to a self-publisher’s income. These sales came from networking. (Don’t you dare call it luck. I networked!) But you can also go looking for special sales. In fact, traditional publishers have whole departments dedicated to special sales.

The key is to learn the basic business of the sales process from purchase orders to invoices, not something I can teach you here. But something to investigate and learn.

More paths to special salesNefertiti also caught the attention of the subscription box service Little Passports. A box service offers a monthly box filled with—in this case—children’s books about traveling the world. Their flagship box promised a tour of the world for kids. But they decided to add STEM boxes, too.

They contacted me first about CLANG! Ernst Chladni’s Sound Experiments because it was an NSTA Outstanding Science Trade Book, for a box about sound experiments. But they quickly became interested in Nefertiti as a fun way to talk about space.

They asked if it was possible to change the trim size from 8.5” square to 8” square, and they wanted to co-brand the books. That is, they wanted their logo on the book cover’s corner. That meant I couldn’t sell these books anywhere else. Apparently, some traditional publishers stumbled over that request, but it made sense to me. I was glad to accommodate them. I negotiated a reasonable price, did offset printing for the special orders, and received a nice profit on each book. In return, I’ve sold tens of thousands of copies of both books to Little Passports.

Think like a publisher, not like an authorBulk or volume sales is thinking like a publisher. An author says, “I want to do school visits and sell books to kids afterward.” There’s nothing wrong with that idea in the early years. In the first few years of your business, do anything you must to stay afloat. But eventually, you’ll learn that you can’t scale up author visits. Your time is too limited. You may sell a couple thousand books in a year that way. If you really travel and work it, it could be very lucrative.

But that meant you weren’t home writing the next book. And eventually, you run out of days in the year to present. After a certain point, you can’t scale up.

Instead, think like a publisher. I want to wholesale the books to someone like Little Passports because they work to acquire the end customer, not me.

Pursue international salesSo far, the Another Extraordinary Animal series hasn’t received any solid offers for international translation deals. I’ve done well with the Moments in Science series, which sold a four-book deal to Dandelion Children’s Books in China, and a six-book deal to Dabom Publishing in Korea.

The feedback, however, on Another Extraordinary Animal has been that the series is too focused on American animals. Calaveras County, California holds an annual frog jumping contest based on Mark Twain’s short story, “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County.” Over 30 years ago, Rosie the Ribeter set the world-record for the longest triple-jump, a record that still stands. Yes, it’s an American story.

But next year, I’ll add a new title to the series, Diego: The Galapagos Giant Tortoise. This is the amazing true story of saving a species from extinction. Sixty years ago, scientists thought the tortoises from Española Island were extinct. They only found 14 individuals, 2 males and 12 females. And then, they found one more in the San Diego Zoo, whom they named Diego. For 60 years, the scientist worked on a breeding program, figuring out what the tortoises needed in a breeding ground, protecting the hatchlings until they were big enough to survive on their own, and eventually reintroducing the tortoises to their home island.

In 2020, they declared the breeding program a success, with over 2,500 tortoises now on Española Island. And in June 2020, they loaded up the original 15 tortoises and returned them to the island of their birth. After being gone for about 100 years, Diego came home.

I am hopeful that this book will expand the series into a stronger international focus and will find interest in other markets. In other words, Nefertiti remains part of that series has a bright future!

Value your copyright: rights and licensingAs a self-publisher, I know the value of my copyright. Each right (hardcover, audiobook, merchandising, etc.) has potential for income. I didn’t sign away all my rights in a single contract.

A website that teaches reading to kids needed some solid nonfiction texts. They licensed the right to display on their website Nefertiti and another book, Pollen. Both contracts were for text-only and for a five-year period. After that, they would have to come back and negotiate a new contract.