Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 68

August 18, 2021

The Secret to a Tight, Propulsive Plot: The Want, The Action, The Shift

“Vine swing” by rrriles is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

“Vine swing” by rrriles is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0Today’s post is by editor Tiffany Yates Martin (@FoxPrintEd). Join her on Oct. 6 for the online class 5 Steps to an Airtight Plot.

Creating a story without at least some idea of your plot is like planning a trip without a route: You’re likely to wind up meandering, stuck, or lost.

But strong plot is more than just a series of interesting events. It’s a foundational element of what creates story—the road along which your character travels and is changed en route to a strongly held desire.

This basic definition of story means that plot is intrinsically tied to character. As a story element it doesn’t exist in a vacuum, but is both driven by and drives the protagonist: what she wants, the steps she takes to get it, and how she’s affected by each step on that journey.

You can adapt how much you decide to plot in advance of drafting based on whether you’re a die-hard plotter, a pantser, or something in between (“plantser”), but framing the overarching story as well as each scene within it through the lens of your characters and these three key elements—the want, the action, and the shift—will help guide you through creating a consistently cohesive and propulsive plot.

Think of your protagonist(s) as Tarzan.If you want him to fly through the air with the greatest of ease, your job as the author is to make sure there’s a vine within reach when he needs it, that it swings him smoothly through the jungle canopy, and that there’s another vine ready for his grasp when he reaches the end of that arc. He can travel the whole jungle that way, all the way home to Jane.

That’s the sense readers should have of your character’s journey—that they’re effortlessly borne along with your protagonist on an unbroken series of arcs toward the final destination. The want is the vine awaiting the character’s grasp; the action is the swing; and the shift is the transfer from one vine to the next awaiting vine.

If any of these three stages fail, that smooth momentum is broken and you risk sending your protagonist—and your reader—plummeting to the forest floor, or stranded in the treetops or on a motionless vine.

This formula applies not just to each individual scene, but to the story as a whole. Before you even begin drafting, see if you can define your story through the lens of the want, the action, and the shift:

Hypercautious Marlon is desperate to keep his sole remaining child close to the safety of home and his protection after the rest of their family is killed, but when his son is swept out to sea, Marlon must face the dangers of the open ocean in trying to find him—and learns that life must be lived fully, despite the risks.

Did you recognize the key plot points in Finding Nemo?

The want is clownfish Marlon’s desire to keep Nemo safe in their little anemone and corner of the sea.The resultant action is his journey to track Nemo down and bring him safely home, and all the challenges, obstacles, setbacks, and advances along the path to that goal.The shift is Marlon’s realization that he can’t shelter Nemo from every danger, and that a meaningful life can’t be lived in fear.Even if this is all you establish before starting to write, it will still create a map to keep you on track as you travel the road of your story. And as a bonus, it can also double as a clear, concise log line to use when you’re ready to query and pitch.

How scenes work with want, action, and shiftThe want, the action, and the shift should also form the foundation of each scene within the story, either as you outline or as you’re drafting. In stories with the strongest momentum, every single scene in the plot comprises a necessary step along the protagonist(s)’ path toward their ultimate goal—each scene is a “mini-story” of its own, with its own want, action, and shift, each in service to the über want-action-shift we defined above.

The WantOne of the most important skills an actor learns is never to walk onstage without knowing what their character wants in that scene. The same goes for fiction: Before you begin writing a scene, know what “want” your character enters with. That’s how you put that vine in Tarzan’s hand as he reaches for it.

A character’s want in a scene might be a strong, tangible, urgent goal: to rescue the princess, to escape the bad guy, to win a promotion or a love interest or a battle.It might be a less concrete, internal one: to attain a parent’s approval, to assuage a spouse’s anger, to help a friend.The immediate want could also be a subtractive goal: Your characters might want to not feel a certain way, or to avoid a particular outcome.You don’t have to have a major story- or character-defining goal in every scene—as long as whatever that “want” is directly or indirectly serves the character’s overarching want in the story: i.e., attaining this immediate goal will (theoretically) move the character closer to her end-goal.

The ActionAs a direct result of her desire for that goal, your character should take some definitive action to attain it—this is the swing of the vine that moves us through the story.

If, for instance, your protagonist’s “want” in a scene is to avoid yet another fight with her partner, what does she do to pursue that goal? Does she come into the house with a big smile and a bouquet of flowers? Slink in the garage door as quietly as possible so as not to draw her partner’s attention or ire? Not go home at all, but instead delay her arrival with an extended happy hour with friends?

This scene, then, will be about her attempting to achieve her want by taking those specific actions—and whatever results from what she chooses to do (or not do) will create further action within the scene:

Maybe she succeeds in disarming her partner with the flowers, and the two wind up having an unexpectedly pleasant evening together over wine and a nice dinner.Perhaps she tries sneaking silently inside, but her partner intercepts her with a hurt expression, asking why she’s avoiding them, and the evening ends in wounded feelings and tears the protagonist can’t assuage.Maybe she gets home late from her unannounced happy hour, only to find her partner waiting up for her, loaded for bear, and a spectacular fight ensues.The ShiftThe character’s action in the scene will either move her closer to her end goal or cause a setback from it. In either case, readers need to see how she is affected by the results of her actions, and how they change her behavior, thoughts, and actions going forward—the “shift” that directs readers toward that next vine, a.k.a. the new want that results from the character’s shift.

If our hypothetical protagonist enjoys an unexpectedly nice evening with her partner, for example, maybe it changes her attitude toward them, and the next day she finds herself eager to get home, planning to surprise her partner with dinner from their favorite restaurant.

That original shift led to a new want, which will lead to new action. Is her partner not home and our protagonist tries to figure out where she went? Or have they reverted to their resentment of her and start another fight? Or do the two sit down over dinner and decide to work on their relationship and save it? Which will lead to a new shift…a new want…new action…and so on.

This pattern of want-action-shift creates powerful momentum, vine to swing to new vine, over and over, and creates a plot that keeps readers carried effortlessly, seamlessly along throughout your story.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, please join me and Tiffany on Oct. 6 for the class 5 Steps to an Airtight Plot.

August 16, 2021

Should You Publish Your Book with a Small Press? Two Literary Agents Advise

Today’s guest post is a Q&A by Sangeeta Mehta (@sangeeta_editor), a former acquiring editor of children’s books at Little, Brown and Simon & Schuster, who runs her own editorial services company.

As Big Five publishers merge and the competition to land a book deal becomes increasingly fierce, small press publishing can seem like an ideal option for some writers. And for those who prioritize being traditionally published but aren’t concerned with the size of their advance, it can be a win-win situation. Many small presses invite unsolicited manuscripts during specified reading periods or year-round, offering writers the ability to bypass securing representation before being published.

Small presses have produced Pulitzer Prize winners and International Booker Prize finalists, in spite of sometimes limited budgets or distribution. A tiny indie press is responsible for one of the titles longlisted for this year’s Booker Prize. But not all small presses achieve the same level of success. In some cases, signing with a small press can hinder rather than help a writer’s career, as the Writer Beware website and blog warns.

To get a better sense of the nuances of small press publishing, I spoke with literary agents Michelle Brower of Aetivas Literary Management, whose “Insider Advice for Small Press Publishers” panel I virtually attended at the AWP Conference this past spring, and Jennifer Chen Tran of Bradford Literary, who worked at an independent press before becoming an agent. As with all my Q&As, neither knew the other’s identity until after they submitted their answers to my questions below.

Let’s start with your definition of a small press. Is this a traditional publisher that operates much like a corporate publisher but on a smaller scale? How else would you differentiate a small press from, for example, a Big Five publisher and one of its imprints? Is it correct to say that all small presses are independent presses?

Michelle Brower: Small presses, to me, are both independent entities that publish fewer titles than most imprints at a Big Five publisher. There are independent publishers that I would not consider “a small press,” because they have bigger or medium-size budgets that can compete with Big 5 imprints.

Jennifer Chen Tran: In my view, a small press is a press that focuses on publishing a limited number of titles each year and usually generates less revenue than major publishers, due to having a smaller list. Some small presses follow a traditional model and provide advances, functioning much like larger publishers. Small presses may not have the same distribution reach that a Big Five publisher does, and they may or may not have more than one imprint.

Even though every small press is different, many are publishing important books that may be overlooked by bigger publishing houses. The vast majority of small presses function independently, but I also know of other small presses that may be nonprofits or be beholden to a certain mission. For instance, when I served as Of Counsel to The New Press, which is considered an independent publisher (but is also a nonprofit publisher), it was clear that the books they were acquiring were social justice-oriented and centered on issues important to the public interest.

What are some advantages of publishing with a small press as opposed to a corporate publisher? (For example, is the author given more personalized attention? Creative control?)

MB: What I’ve learned is that this can vary widely across small publishers. What you do know is that you are a bigger fish in a smaller pond, and it’s more likely that you’ll have contact with the owner of the press and be more involved in the publication process.

JCT: I think this varies on a case-by-case basis. Some small presses give their authors a lot of attention, partially because of their smaller list, and partially because this is just how they do business. Publishers that treat their authors well, by being more responsive, by giving their authors more attention for marketing and publicity, or even consulting with their authors on cover designs, demonstrate that they understand the give-and-take of a creative relationship. I’ve found that the size of the press often isn’t the defining factor when it comes to the overall dynamics of the relationship. Additionally, a smaller publisher may be more open to negotiating certain terms of the publishing contract, which often works in the author’s favor. Furthermore, you may or may not need a literary agent to pitch a smaller press.

Conversely, what are some of the disadvantages of publishing with a small press? (Small advances? Limited distribution?)

MB: Distribution is definitely an issue, as well as small or no advances and a potentially overstretched staff who are responsible for the same tasks that a larger publisher does (publicity, marketing, editorial), just with fewer people and smaller budgets.

JCT: Smaller presses usually don’t have the backing of a major corporation so the advances can be lower, but I have to say that I’ve been pleasantly surprised by the offers some of my clients have been receiving from smaller presses. Distribution is less likely to be robust, but this may become less of a disadvantage given how consumer buying habits have shifted due to the pandemic (and it remains to be seen if retail will bounce back). Smaller presses may not have the same marketing and publicity bandwidth that bigger publishers do.

When you’re ready to go out with a client manuscript, how likely are you to include small presses in your first round of submissions? In later rounds? Does your decision depend in part on who the acquiring editor is? If your client is a debut author or a multi-published author?

MB: I almost never include small presses in my first round except for a few very well-regarded literary presses; it often doesn’t make sense financially for the author. But I do frequently include them in second rounds and if there is a specific reason that particular press would be the best fit.

JCT: It depends on the project. I usually include major publishers in the first round because they tend to pay higher advances. This really helps my authors out, some of whom have been working diligently on their projects for over a year! There are some projects that I represent that might be more niche, or perhaps another agent had previously represented the author but was not successful selling the project, in which case I try to be more strategic about where the project will be best placed.

Matching the right editor to the project is as much an art as a science and so yes, who the acquiring editor is will greatly factor into my pitching strategy, as well as where the author is in his or her career. It can be harder to pitch a midlist author if their previous books didn’t sell as well as we had hoped, but I am continually surprised by how things pan out and remain ever optimistic for my clients. I have a different strategy for every client and I really believe that enthusiasm goes a long way, both on my end when I’m pitching projects and also from the acquiring editor. I’ve had a situation where an acquiring editor at an independent publisher told me that the support for my client’s project was unanimous and unprecedented—not to brag, but that was a very good day!

If a small press is upfront about their ability to offer your client a contract that leaves little room for negotiation, what would your role be in the book deal? How would you be involved with your client’s book once the contract is signed? Once the book is published?

MB: I will always try to negotiate the best contract possible for my client, even with a small press. I would also not hesitate to tell my client to not sign a contract that would be detrimental to them in the long run. But beyond that, my role is the same as with any book, doing everything I can to be a partner in helping it reach an audience.

JCT: I’m pretty adamant about obtaining the best terms for my client. I also have the backing of an established agency, which helps me negotiate better terms for my client based on past course of dealing. I never accept a contract at face value and I truly believe that most everything is negotiable. If a small press (or any press for that matter) has a “take or leave it” attitude, that is a red flag. After the contract is executed, I try to take a step back and let the editor take over, so to speak, but I also want to be informed of any major editorial feedback and support my authors during the marketing/publicity stage.

Since many small presses accept unagented submissions, many writers are inclined to query them at the same time they query agents. If a writer who has queried you follows up to tell you that they have an offer from a small press, what is the best way for them to inform you? In what instances would you offer representation? Encourage the writer to pursue this opportunity on their own?

MB: If they have an offer, they should definitely inform me over email. However, since I work on commission and small press advances are often quite small, it often makes more sense for the writer to use a publishing attorney to vet their contract than use an agent.

JCT: The best way to tell me is via a direct message on Query Manager (which is what I use to field queries) or via email directly if we’ve already corresponded via email. I would only offer representation if I felt that the potential client was a good fit for my list and that I’m also a good fit for the potential client—sometimes the best way to find out if it’s a good fit is through a phone conversation. Over the years, I’ve had quite a few writers come to me with offers in hand, but I decline offering representation if I don’t think they are a good fit for my list or if I have another client that is writing something very similar. I don’t want my clients to be competing with each other so I’m also very mindful of my current client list when offering representation.

As corporate publishers continue to merge (Penguin Random House—once two separate companies—has proposed purchasing Simon & Schuster, and HarperCollins has now acquired Houghton Mifflin), do you think more authors will sign with small presses? Or will the remaining Big Five or large independent houses be in a better position to attract those authors who are concerned about the industry’s move toward “megapublishers”?

MB: My prognostication is that the books that sell to the Big “whatever number we arrive at” will sell for higher advances, but there will be fewer of them. I also think small presses will be at a disadvantage in terms of distribution and pushing back on the terms from online retailers compared to corporate publishing. But I always believe that publishing needs an ecosystem to flourish, and that includes small presses, self-publishing, corporate publishing, and the formation of new, medium-sized publishers.

JCT: I predict that small presses will only have a more important and vital role in publishing as corporate publishers continue to merge and consolidate. Often, small presses will take on projects that might seem too risky or on the “fringe” for Big Five publishers. Authors will continue to sign with small presses, independent presses, and hybrid presses because Big Five publishers might not be willing to invest in clients and projects that seem more niche. Big Five publishers are still taking risks, but I think there are a lot more hoops for the author to jump through at a major publisher. For instance, for nonfiction projects, platform is only becoming more important and often it can be a deal killer if the author doesn’t have an extensive enough platform. Nevertheless, I am hopeful that small publishers will continue to publish great talent, and I truly believe that their continued success is vital to the publishing industry. There is no one-size-fits-all solution and authors are becoming savvier about how many options are available to them too.

Do you have any other advice for writers who are considering submitting to and publishing with a small press?

MB: If you do want to sign with an agent and try to sell your book to a big publisher, I would not query small presses at the same time. And if you decide to work with a small press, be prepared to put a lot of elbow grease into your publication. Lastly, make sure to vet your contract! There is no standard small press contract, and they can vary wildly; make sure you are not signing away something valuable.

JCT: Yes, consider your long-term goals and ask yourself where you want to be in five years. Do you want to have multiple deals published with a major publisher or would you rather publish your book with a smaller publisher first and then perhaps try a major publisher on your next go? Publishing is a marathon, not a sprint, so educate yourself and read as much as possible about the industry while also perfecting your craft. At the end of the day, there are so many amazing authors and stories out there that deserve to be published, and it’s just a matter of fit, timing, and a bit of luck. You can and will find the agent, editor, or publisher that is right for you. Believe in yourself, stay open-minded, and never give up!

Michelle Brower (@michellebrower) began her career in publishing in 2004 while studying for her Master’s degree in English Literature at New York University. After stints at Wendy Sherman Associates and Folio Literary Management, she joined Aevitas Creative Management, where she is a partner. She is looking for literary fiction, suspense, “book club” novels, genre fiction for non-genre readers, and literary narrative non-fiction. Her authors include Tara Conklin, Kathy Wang, Erika L. Sanchez, Jason Mott, Erika Swyler, Clare Beams, Riley Sager and Jaquira Diaz, among many others.

Jennifer Chen Tran (@jenchentran) is an agent at Bradford Literary. She represents both fiction and non-fiction. Originally from New York, Jennifer is a lifelong reader who now lives in California (please send bagels). Prior to joining Bradford Literary, she was an Associate Agent at Fuse Literary and served as Of Counsel at The New Press. She obtained her Juris Doctor from Northeastern School of Law in Boston, MA, and a Bachelors of Arts in English Literature from Washington University in St. Louis. Jennifer is the child of Taiwanese immigrants and hopes to continue to work with authors from marginalized backgrounds. She is looking to grow her list in the areas of upmarket women’s fiction, graphic novels (particularly for Middle Grade and Young Adult), adult and children’s non-fiction, cookbooks, lifestyle titles, narrative nonfiction, and business books. Her ultimate goal is to work in concert with authors to shape books that will have a positive social impact on the world—books that also inform and entertain. She is honored to work with her talented clients, including Dierdre Wolownick, Stuart Palley, Dr. Elizabeth Landsverk, Missy Dunaway, Steve Casino, and others.

August 11, 2021

How to Harness Community to Build Book Sales and Platform

Photo by Chris Montgomery on Unsplash

Photo by Chris Montgomery on UnsplashNote from Jane: This Wednesday, I’m teaching an online class on effective book marketing for any author. A recording will be available if you can’t attend live.

When it comes to the differences between traditional publishing and self-publishing, marketing is a key area where strategies diverge, often dramatically. Professional self-published authors tend to focus on Amazon or Facebook advertising, sometimes giveaways, and they speed through marketing campaigns in record time—not least because another book release can be right around the corner. Traditional publishers, on the other hand, will spend months or even a year or more planning a campaign and thinking about content marketing, influencers, and brand partnerships.

This summer, at The Bookseller’s Marketing & Publicity Conference, publishers large and small discussed how they work with authors to plan book launches and long-term marketing and promotion, especially in relation to online communities or social media—ever more important, given the rise of online sales. While not all authors receive the same level of in-house support from their publisher, it helps to know what a strong effort does look like, to be educated and aware of what’s possible.

To start, authors have to buy in to the core message of the publisher’s marketing campaign as early as possible. At the start of every campaign, the publisher is thinking about how to use the author’s platform effectively. But this must be approached in a collaborative manner to work. Senior marketing executive Sian Gardiner and senior publicity manager Jess Duffy, both of Bluebird and One Boat (imprints of Pan Macmillan), discussed how to avoid “battling with authors to get them to post something that we know is going to help the book but they don’t feel truly represents them.” Early conversations with authors help bring marketing in line with the authors’ persona and community. “[Our] tailored strategies are informed by the authors’ unique knowledge of their online communities and supplemented by our expertise,” they said.

The community surrounding the author (and/or publisher) should be engaged early in the process and be part of the journey, said Gardiner and Duffy. The marketing campaign will fall flat if there are scattered calls to pre-order and vague mentions of the book without sufficient “content wrapping.” The right strategy is to drip-feed information about the upcoming book (or existing books) through the year. If planned early enough, there can even be requests for input from the community (almost like a focus group), with lots of free content sharing and behind-the-scenes footage. “That means when it comes time to truly hammering home that pre-order messaging, the audience is already completely invested in the print purchase,” they said. However, Gardiner and Duffy warned that, with nonfiction authors in particular, the majority of an author’s community may not be book buyers and are not necessarily choosing to follow them for book content. “This means it’s crucial that the author integrates the book messaging that feels true to the spirit of what they usually post.”

As a case study, Gardiner and Duffy referenced Laura Thomas’s nonfiction book Just Eat It. They knew the author’s audience had huge potential for growth. Through influencer engagement (more on influencers in a bit), exclusive snippets from the author’s podcast, and a series of giveaways, the publisher built the author’s following from 20,000 to 100,000 in six months. For Nikesh Shukla’s memoir, Brown Baby, the publisher helped the author launch a parenting podcast that was shared by the high-profile guests he interviewed—and the publisher also secured a lot of podcast interviews for Nikesh himself.

In a similar vein, Penguin Random House (UK) has been focused the last couple years on bolstering its editorial content for readers, according to Indira Birnie, a senior manager at the company. She described, ultimately, a content marketing strategy for reaching any and all readerships—content that can be created ahead of time and used for months if not years, including podcasts, online articles, video, etc. For instance, with Obama’s memoir (yes, it does need to be marketed, and without much access to the author!), Birnie’s team compiled a list of all the books he’s publicly recommended over the years and published it at the PRH site. That piece of content has been popular and has continued to perform well even more than a year after the book’s release. Birnie said, “It makes a lot more sense to me to create one really good piece of content”—something that is tailored to the readership and to a particular platform—rather than churn out substandard pieces that get blasted everywhere but fail to engage.

Social media plays a significant role in just about every marketing campaign. Gardiner and Duffy said one of the biggest sticking points when it comes to social strategy can be the regularity of posts required. Some authors worry about spamming their followers or appearing overly sales-y. But the lifecycle of social posts is incredibly short: 18 minutes for Twitter, 2.5 hours on Facebook, and 48 hours on Instagram. It’s possible for followers to miss most posts, in fact. That’s why an author’s book must be incorporated into an author’s regular posting strategy, so the majority of their following will be aware of the book even if they miss most posts.

Birnie said it’s interesting to watch influencers work on social media, since they have “guerrilla tactics” and don’t stick to certain rules to keep people engaged. They might run polls or Q&As where it’s very easy and quick for audiences to respond. “You’re not asking them to do much, and you’re not asking them for much time.” It becomes a really canny way, she said, of getting the algorithm to favor your content; informal methods of engaging can be some of the most powerful methods.

Social media platforms often roll out new features, and while it may be frustrating for authors to have to keep relearning the tools, Birnie said it can work in your favor to jump on them early. Far fewer people use those new features (like Reels on Instagram), and if you’re there first, you can grow your audience. However, she acknowledged, “It is a resource thing,” and PRH has to allocate its time wisely. Elise Jackson, a senior marketing executive at Pushkin Press, said that video is very tricky—it can cost money or be a significant time investment. “We have to be sure about the content.”

Influencers, particularly those on social media, can be central to a campaign’s success. Jackson said, “I love influencers, they’re my favorite people.” She outlined three different types that she works with at Pushkin. First, there are people who essentially act as brand ambassadors for the publisher and love everything that Pushkin does. “They trust us as a brand and shout out about anything that we do. They are amazing, and we have really good personal relationships with them.” Second, there are influencers they reach out to in a strategic way as they plan a marketing campaign, on a case-by-case basis, and tailor the pitch or approach to their particular interests. This takes time, of course, but leads to better results.

A third type of influencer marketing is a brand partnership. Jackson gave an example of a children’s book they marketed that’s a work of climate fiction. Pushkin was working with teacher influencers but also established a relationship with a sustainable children’s clothing brand. “That brought in hundreds of people to [our] newsletter and massive engagement not only on our channels but on their channels,” Jackson said. “That’s a better use of time than emailing a bunch of climate change activists who might not have any interest in a children’s book—knowing where to place your influencer investment depending on the campaign that you’re working on.” She said that every influencer should be treated as a complex consumer; they are not all alike.

Email newsletters, as usual, were cited for their dramatic importance in driving sales during the pandemic. Jackson said the pandemic changed how the publisher uses email, and the effort has been worth their time. “We became our own booksellers through the newsletter. Before that we hadn’t put that much time into segmentation or who was opening these newsletters.” But it became clear it was the most immediate way to gauge what people were actually interested in buying. They now rely on newsletter engagement data and segment/tag readers appropriately, to better understand who is going to buy what and avoid saturating the subscribership. They also have separate lists for influencers, teachers, librarians, and so on.

Birnie said that PRH has moved away from driving clicks to retailers from their email newsletters and now focus on disseminating content and getting their audience engaged with that content. They do five newsletters a month, and most are full of editorial content. Only one is sales focused. Like Pushkin, they’re focused on more personalization or a more tailored experience for each subscriber.

Some marketing fundamentals never change and must be optimized before a campaign can lead to sales. Namely: the book cover, the book description, and the overall positioning. At NetGalley, when people request review copies, they answer a series of questions, like whether they like the cover, why they’ve requested the title, and so on. Stuart Evers of NetGalley UK said the book’s description is by far one of the most important reasons why people have selected a title. For example, for one book, the survey data revealed that very few people were choosing a title because of the author, despite that author being a significant name. The publisher started digging into why (partly by asking sales reps), and realized that many people had not read the author in many years, or younger people hadn’t heard of the author or thought the author old-fashioned. So, for the paperback release, the publisher changed the positioning. They highlighted the book itself and the story line, not the author, and the paperback sales hugely increased.

An ideal to strive for? A year-round marketing campaign. Gardiner and Duffy advocated for this approach, even though it may seem like an impossible task. In fact, it’s less labor intensive than people think. Start with the basics, they recommended. “We make sure to always let our authors know when there is new activity happening around the book and often will draft copy for them to post on their social channels.” For example, this could be a new Kindle deal, a new piece of media coverage, the launch of an international edition, or a shout-out from a high-profile social account. “We also ask our authors to forward any and all event requests they receive,” they said. Often an event that doesn’t seem to directly correlate with the book can still be a meaningful sales opportunity. “After the authors wow [the audience] with their brilliance, the book becomes a perfect physical takeaway from a potentially life-changing or inspiring moment.”

Bottom line: One of the long-held maxims of marketing—To go wide, start narrow—was expressed a number of times at the conference. Be focused and specific about who you’re trying to reach. Evers of NetGalley said that publishers and authors can be guilty of thinking they want a book to go out to as many people as possible when what they actually need to do is focus. “Get your community really excited about it, and they can talk about it to a wider society,” he said. Look to partner with specific authors, creators, and brands to harness the power of these communities. Successful campaigns find a core message everyone can get behind and make it the driving force, especially on social. “If the content is creative and well thought out, there should be no fears around oversaturation,” Duffy and Gardiner said.

This piece first appeared in Jane’s newsletter, The Hot Sheet.

August 10, 2021

Dual Point of View: What to Know While You Write

“two people, two windows, nothing else” by Georgie Pauwels is licensed under CC BY 2.0

“two people, two windows, nothing else” by Georgie Pauwels is licensed under CC BY 2.0Today’s post is by author E. J. Wenstrom (@EJWenstrom). Her dystopian YA novel, Departures, is out now.

Writing a novel with a dual narrative—where two different characters get to share their point of view as narrator—can be a particularly fun creative project for an author. But it comes with its own unique set of challenges, too.

How do you make it clear which character is narrating? How do you fit the two arcs together? What makes these two narratives one novel, instead of two separate stories?

These and other crucial considerations can make the difference between a manuscript that sings with resonance and tension, and one that flops under the weight of confused story lines, conflated characters and frustrating breaks between arcs.

Here, we’ll explore some of the most important aspects to consider while drafting.

Which character is the primary protagonist?Yes, you really do have to choose, even if the narratives will share the spotlight abut 50/50 throughout the novel. Something has to give your book a clear center and keep it propped up, like the pole at the center of a tent. This is the plotting and thematic heart from which everything else should stem—even if that’s through creative interplays across space, time or perspectives.

When in doubt, consider: Which character’s perspective does your story start with? Which does it end with? They should be the same character. And that character is your tentpole.

What distinguishes your point-of-view characters?When flipping back and forth between two perspectives, you can do your reader a great favor by making it easy to distinguish between the two at a glance. While tags at the start of each section are nice, what I’m really talking about here is voice.

As each character is brought to life on the page, look for opportunities to make them distinct from each other, including factors like different perspectives, word choices and body language. The more easily a reader can flip to a random page and tell which character is narrating, the better.

Are both points of view absolutely necessary to the story?If this answer isn’t an easy yes for you, pause and reconsider your dual structure. Can the same story be told through one character’s perspective? Maybe it’s a story just as well told if one of the characters is supporting cast!

But if your gut gives you a resounding yes to this question, both perspectives are absolutely necessary, then great. What do these two characters bring to the story that must be told together?

I know many authors, including myself, who don’t identify the themes of their manuscript until after the first draft. There’s nothing wrong with that, but this is an important question to be able to answer for dual narrative, so if you don’t know it going in, noodle on it as you draft and look for opportunities to make the answer an easy yes. Make sure you have an answer about why both narratives are necessary before you revise, so it can inform how the manuscript takes shape.

How will each character’s arc interplay with the other?Part of the enjoyment of dual narrative is the way the two arcs bump up against each other.

Sometimes this is a literal crossing of paths at key moments, such as in Lauren Oliver’s Replica, in which two characters from completely different worlds must help each other at a crucial juncture.

But for others, especially if the characters are in different time periods or otherwise separated, this might be done through thematic interplay or parallel scenes. In The Lost Apothecary, one modern-day woman wrestles with the aftermath of leaving her cheating husband, while in the 18th century, another doles out poisons for husbands to women who have no other means of escape.

In my novel Departures, the two sisters may seem very similar at first glance, but really, they are foils. Their arcs reflect this by offering an inverse of each other in their setting, twists and the characters’ different responses to similar circumstances.

Or, as Susan Elliot Wright explains, dual narrative can also be used to undermine the characters’ reliability and build suspense—such as in Gone Girl.

The creative possibility here is endless.

How and when can the story transition between threads?The conceptual and thematic aspects of dual narrative are crucial, but at some point, the rubber must meet the road. Personally, I found the logistics of executing dual point of view the hardest part.

In each section of the narrative, the story must spend enough time to allow the reader to get emotionally invested, and to move the plot forward. When you transition to the other character’s perspective, it can be a careful balance to find a suspenseful hook to conclude on that will keep the reader eager—but not so eager they’ll resent the break in narrative.

Knowing where the line is can come down to genre, style, and story—in other words, it’s a judgment call. So if you’re writing dual narratives, be sure to read a lot of dual narratives, too, especially within your genre, to study what works and hone your instincts. Beta readers can also be invaluable for this as well, so ask them for their feelings about these important transition points between characters.

Dual narratives are rewarding to writeWriting a dual perspective novel can easily tie you up in knots. But it also opens up the doors to rewarding opportunity between characters and story lines. With some consideration during the early drafting process, dual narrative opens the door to new creative space for your story, and a lot of creative interplay. Don’t be afraid to dig deep into its layers and experiment with it.

August 9, 2021

Should MFA Programs Teach the Business of Writing?

Photo by Vladislav Reshetnyak from Pexels

Photo by Vladislav Reshetnyak from PexelsAnyone who knows me even a little can guess my answer to this question. I even wrote a book, The Business of Being a Writer, that’s meant to be used in university writing programs to help students understand the publishing industry and what it means to earn a living from writing. My perspective is informed by my work in the publishing industry, as well as being someone who has a degree in writing. A few background details:

I earned a BFA in creative writing and an MA in English. My undergrad education led to some school loans; my graduate degree was funded entirely through an assistantship.I was employed at a mid-size publisher while I earned my master’s. I really had no choice—I needed the money. I decided not to pursue an MFA in creative writing for a variety of reasons, but primarily because I couldn’t afford to take time off work or enroll in a low-residency program. Neither was I eager to step away from my publishing career, which was teaching me far more about writing than I ever learned in school.I was an AWP member for many years and attended AWP’s annual conference first in 1998, then every year between 2004 and 2018. Often I was a panelist or speaker. (More on this later.)I’m a regular speaker at MFA programs around the country, both in person and virtually, and moreover I hear the concerns of early-career writers daily via email and social media.Several years ago, I was hired by Southern New Hampshire University to help develop the curriculum for their online MFA program, which includes a strong professional development and publishing education component. Their goal: to graduate writers who learn the fundamentals of craft while also understanding what it takes to publish professionally and successfully.Despite the books I’ve written, the keynotes I’ve delivered, and the courses I’ve taught, I’ve never laid out, in a public forum like this, why I think it’s problematic when MFA programs or professors argue that the business of writing lies outside their purview. Why? Well, the type of person often attracted to the MFA likely believes the same and I don’t see my role as persuading the unconvinced or barging in where I’m unwanted. Rather, I am here if people see the need, as I do, for writers to understand the business they’re entering.

However, I think times are changing, for many reasons which I won’t delve into here, but part of it has to do with the gig economy and/or creator economy and the greater variety of writerly business models we now have than we did twenty years ago. More writers are ending up in undergraduate and graduate writing programs who need and want this information. I also believe writers should leave degree-granting programs prepared for the pragmatic and professional issues they will face as a writer. They’re often working alone, with limited or bad business guidance, confused about what’s “normal.” The anxiety and confusion is apparent at every AWP conference I attend. So is the bitterness and resentment for those who wake up to the reality of their situation, after they’ve invested thousands of dollars into a writing education.

And so MFA programs need to acknowledge what’s happening and evolve.

Still, there is resistance—and the more prestigious the program, the more resistant they are. Here are the most common arguments I see against introducing business into an MFA program.

Writers should focus on craft first, business later.It can appear boorish or second rate to suggest that business could or would ever be as important as art, craft, or technique. Because art is everything, right? Without quality work, there is no business—right?

(Let’s put aside the fact “quality” is subjective and MFA programs tend to be concerned with the kind of quality that’s of less interest to publishers than you might think.)

This “craft first” argument has a big assumption behind it: that art and business are antithetical to each other or can’t be in conversation. This belief is so ingrained in the literary writing community that few even question it.

Just look at the stories we tell about great writers, which all generally sound the same: we focus on the development and discovery of their literary genius. Business conditions rarely enter into it, much less business acumen. George Eliot is celebrated as a great moral novelist, but she also left her loyal publisher for another house that offered her a bigger advance. The bestselling work of Mark Twain—a novel that funded his career—was sold door-to-door in a very low fashion instead of properly, in a bookstore. (Today’s equivalent might be selling your ebook through Amazon rather than the print edition through your local independent bookshop.)

Why don’t we share these business stories? Because it is typically taboo to produce for the market or to be too good at business, lest you get pilloried by your peers and accused of selling out. Amy Lowell met this fate: she was criticized by T.S. Eliot for being a “demon saleswoman” of poetry. Even one of the earliest successful authors, Erasmus, was pitied by his peers for taking money from his publisher. (No self-respecting author at the time took money for their work; you were supposed to be above that.)

What a bind: writers get shamed if they’re not successful but also get shamed if they are too successful or overly concerned with success. How to Reform Capitalism wisely notes, “There remain strict social taboos hemming in the idea of what a ‘real’ artist could be allowed to get up to. They can be as experimental and surprising as they like—unless they want to run a food shop or an airline or an energy corporation, at which point they cross a decisive boundary, fall from grace, lose their special status as artists and become the supposed polar opposites: mere business people.”

The prevalent belief, at least in the literary community, is that “real writers” don’t worry themselves with commercial success or with how the sausage gets made. That’s someone else’s job, that’s for the agent or publisher to worry about. In fact, if one is good at art, then good business will follow or take care of itself. (won’t it?). Quality will make it or cream will rise to the top (right?).

Of course anyone with an iota of life experience knows that’s not true. In her excellent book Make Art Make Money, Elizabeth Hyde Stevens says, “The romantic image of the artist we have been given coyly ignores the fact that all artists are affected by the market.” And sometimes artists are inspired by what’s happening the market. Or they can use market conditions to their benefit. The tension can be productive. Louisa May Alcott first wrote thrillers for money to support her family, and later was persuaded to write a story for girls, Little Women, because a publisher saw market potential in it.

Former NEA chairman Dana Gioia, who holds both an MFA in poetry and MBA degree, and was once an executive at Kraft Foods, said that once you get into middle and upper management, the decisions that you make are largely qualitative and creative. Likewise, writers are in the middle and (hopefully) upper management of their careers, and their business decisions are creative ones. Business and art are often portrayed as antithetical because we think of business in terms of cartoon caricatures. But business is just as a complex and creative as any “pure” art form. Just ask a book publisher.

The other problem with the “craft first” argument: Where do you draw the line? Some writers enter traditional MFA programs well into their thirties or even forties, after decades of writing experience and maybe an undergrad degree in writing. Low-res MFA programs have writers of all age groups. Learning the craft does not come with an end date. You don’t graduate from an MFA program, then presto, you’re done—you are “ready” to attend to the business.

Anyone entering an MFA program, I believe, is raising their hand and saying, “I’m serious about this and I identify as a writer.” If that’s the case, aside from studying the craft, writers ought to understand the basic mechanics of how to get published and the industry that supports them (namely, book publishing and/or various forms of literary publishing). And one hopes there is transparency and frankness about how little most writers earn from book sales or advances.

And finally, have you ever noticed the “craft first” argument gets subverted all the time, not least by those who teach at MFA programs? It’s fashionable to say that writing can’t be taught or that MFA programs don’t teach writing as much as they support and nurture talent, or offer a community. Fair enough, but don’t use “craft first” as the fig leaf for abdicating responsibility for helping students understand the full picture of what they’re attempting. Art and business intersect, and it is artificial to separate them.

This brings us to the next argument often trotted out by MFA programs: that it’s a time and place to focus on one’s writing and not be distracted by the outside world/real world or commercial concerns.

Writers attend MFA programs to focus on craft.This is true for some, but as I indicated above, I think that’s changing. Also, writers may say they’re only interested in craft, but do they really mean it? Why are the most popular panels at AWP the ones that discuss getting published? Or those that feature agents, editors, and business people? The steps that occur after completion of the manuscript are part of the fundamental work of any working writer who wishes to be published.

Also, while students may compete to get into MFA programs and pay for the privilege of devoting a couple years to developing their craft, that’s not their only motivation. They also attend MFA programs seeking the status and prestige that comes with the degree and with the reputation of the school in some cases. They want to study with certain known authors. They want to rub elbows with celebrities in the writing community. Connections are a big motivating factor, and that is very much a business concern: who will help facilitate that next step in your career?

Learning the business subverts the craft—or is otherwise a distraction.It’s true that writers can potentially get distracted by submissions protocol and agent etiquette and all the secret handshake stuff they think exists, but that’s another reason the business needs to be taught. There is no secret handshake and a lot of what the business of writing is—well, frankly, it’s boring. The more quickly that writers can start seeing agents and editors not as mystical beings who anoint them and make their careers, but as average and flawed business people, the better.

Also, we’re not talking about MFA programs switching over to half-craft, half-business curriculum. (Or I’m certainly not.) The basics could be covered in a single required course. There might be a series of optional business-related courses for those who are interested.

I don’t think there is a downside to teaching business if we assume (and we must) that MFA students can be treated as mature adults. Safeguarding them from business talk is infantilizing them and making them vulnerable to bad actors and bad deals if they don’t know what standard business practices are.

And might I suggest that the only students who can afford to not consider the business side of the writing life are those who already have money or a safety net.

Students can learn about the business elsewhere.Well, yes, it’s true. This site, in fact, is one of the places where people end up. I am delighted to offer a basic education that is, I hope, affordable and accessible to many. And I will continue providing it for as long as I can. But there’s a problem.

Many don’t find me, or they don’t know who to trust. A lot of people rely on gossip/whisper networks. Or what their author friend told them to do. I pity the writer who must sift through all the conflicting and even harmful advice. They might wrongly conclude it’s all a crapshoot or that no one knows anything at all. Worse, they might decide the system is rigged or that publishers and agents are vultures, or buy into any number of misconceptions and conspiracy theories that float around the internet.

I’m not the only reputable source of advice out there; there are many valuable books, courses, and resources available to writers. But it would make more sense if MFA programs could lay the groundwork for their students and introduce them to the landscape, who they can trust, and how to spot advice or guidance that is suspect.

People teaching in MFA programs don’t really know the business themselves.This is perhaps the best argument of all, because I think it’s true. Professors may not know best business practices for the average working writer, and their earnings outside of their university salary may be minimal. Their experience with publishers and contracts may be outdated or out of touch. It’s also problematic when professors’ experiences are narrow and specialized yet are represented as either standard or desirable.

I don’t think the solution is that challenging. A program can have visiting professors fill in these gaps as necessary, especially those based in a city like Chicago, New York, Boston, San Francisco, or DC, where publishing professionals tend to live. A professor could invite guests to speak on business topics (I’m invited to speak every year to MFA classes). Perhaps MFA programs should even have a full-time professor whose job is to assist students with professional development, internships, business know-how, etc.

The real challenge is one of mindset, where the directors or professors in these programs promulgate the idea that business doesn’t belong in the curriculum, or that it’s not their responsibility to help students with anything but craft. It’s a shame this attitude persists when the publishing industry has become more multi-faceted and complex—as well as rich with opportunity. Some of it is fear of the unknown and some of it is a desire to hang onto an aura of prestige, to be a program that’s only for the “serious” artists who don’t concern themselves with the market.

Even if we buy into that thinking, though, I don’t see why it should be a problem to at least teach students how agents and publishers work; how book advances and royalties work; how to read a publishing contract; what rights and responsibilities a writer has to the agent and publisher and vice versa; and the varied models of publishing today. It helps writers avoid a lot of frustration and disappointment—and wasted time.

If MFA programs refuse to teach the businessI’d like to see them inform every enrolling writer of the latest Authors Guild survey that shows author incomes declining. While I think these surveys are problematic given the narrow range of authors surveyed, they’re close to the truth for any author with an MFA.

Did you attend (or are you currently attending) an MFA program? What has your experience been?

August 5, 2021

Should I Hire a Coach Or a Therapist?

Photo by Alex Green from Pexels

Photo by Alex Green from PexelsToday’s post is by author, editor and writing coach Mathina Calliope (@MathinaCalliope).

I have no psychoanalytic credentials whatsoever.

Even so, my clients often joke that I’m their therapist, our coaching sessions their therapy. Apart from giving writing advice (which, okay, Anne Lamott conflates with life advice), I don’t counsel. But since so many people I coach write memoir, our work does periodically veer into therapy territory.

Same-SameHere are some similarities:

We excavate. Good personal writing must dig deep. In early drafts, we often are unsure of our protagonist’s (i.e. our) motivations. A coach can draw attention to this unexplained material, and this is often the first time a writer has considered the question. Why did I do that? Speaking from the writer’s perspective, I can’t count the number of times outsiders’ feedback has prompted me to wonder what my psyche knew that my ego didn’t.

Writing coaches and therapists listen; we attend closely. We may offer personal anecdotes if we think they will help illustrate a point, but mostly we listen with the pure intention of understanding. The same way it might be therapeutic to chat with a work buddy or your hairdresser—both people who know you a bit but aren’t friend friends—it can feel healing or clarifying to hash stuff out with a neutral party.

We meet regularly. There’s something powerful about having a block of time on your calendar—weekly, biweekly—dedicated to the pursuit of one aim, whether it’s personal fitness, psychological growth, or improving craft and meaning in writing.

But make no mistake, a writing coach is not a therapist (unless she is … some actually are).

But DifferentIn therapy, the subject is you. In memoir coaching, it’s the protagonist and narrator. Also you, yes, but with huge differences, the biggest of which might be distance. Even though you know and your coach knows that the character in the book is the person on the Zoom call, the fact of the page creates a bit of space. This is why we use the third person to speak about this character. A book is a rendering of an aspect of a life. A person is much bigger, more complex, and layered than that. Even so, figuring out memoir is in large part figuring out that character’s motivations, which the writer might or might not actually understand.

In therapy, all conversation is very obviously about the client, even if it’s a younger, past version of the client, as when dealing with childhood events. In memoir coaching, the conversation is ostensibly about the protagonist, which might permit the client to understand something about themselves indirectly. Sideways.

So what?Why does it matter that coaches and therapists are similar but different? It’s important to get clear about what kind of help you want with your writing. If it’s technical—structure, sentence-level craft, audience, voice—a coach or editor can do the job. If it’s mostly technical and a little bit of deeper stuff—examining one’s motivations, teasing out meaning from events—a coach is your person. If it’s mostly inner work, you might want a therapist.

Coaches and editors have helped me with various writing projects, but about a year ago, when I struggled to determine the point of the Appalachian Trail journey my memoir describes, I decided to reach out to a different kind of professional. I hired a Jungian analyst.

Though he has read none of my writing, our work together has helped me understand the deeper forces driving the actions my protagonist (hi! it me!) takes in my memoir. It makes really good sense for a storyteller to work with a Jungian because Carl Jung trafficked in stories—ancient myths and archetypes. The work of writing one’s memoir is almost exactly parallel to the work of Jungian analysis.

Although I don’t exclusively discuss my book with my analyst, a lot of the material in the book is worth excavating in order to free myself from “complexes.” In other words, unpacking the clump of feels driving my unexplained, puzzling AF behavior. Behavior like, um … quitting my job to walk through the woods for two and a half months.

Readers of my early drafts repeatedly asked me the same question: Why did you do this? And the question puzzled me—not because I didn’t know the answer (I didn’t) but because I couldn’t see why it mattered. Couldn’t see that in fact it was the only thing that mattered, the only reason anyone would read yet another hiker memoir.

My therapist offered no practical solutions to the technical problems of structure or framing for what he did help me uncover. For that, I need a writing coach or developmental editor.

We may think we have Specific Story A to tell, but in the course of writing, if we pay attention and see our actions as readers may see them and ask ourselves what we really, really mean to say, we may discover Story B, or Story C. Your coach can point you toward those questions, but a coach may not be qualified to sit with a client as she discovers their answers. Those can evoke bottomless loss, they can trigger the beginning of a journey through our psyches and encounters with our shadows.

So, writing coach or therapist … why not both?

August 4, 2021

The Secret Ingredient of a Commercially Successful Novel

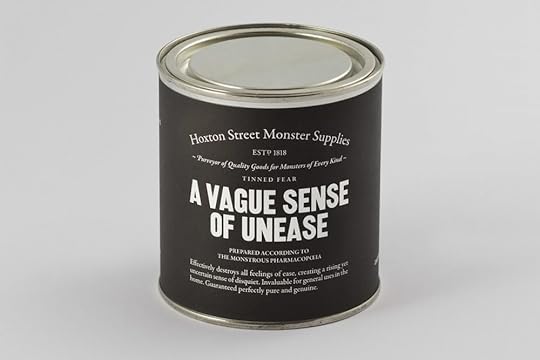

“tinned fear – a vague sense of unease” by ministryofstories is licensed under CC BY 2.0

“tinned fear – a vague sense of unease” by ministryofstories is licensed under CC BY 2.0Today’s guest post is by writing coach, workshop instructor, and author C. S. Lakin (@cslakin).

There are a number of ingredients that make up a commercially successful novel, regardless of genre. Scenes that end with high moments that deliver a punch in the last lines. Evocative, rich sensory detail. Dynamic dialogue that accomplishes much more than conveying information … and the list goes on.

But the greatest and most understated ingredient of a commercially successful novel is microtension. And few writers understand what this is and how it can be used brilliantly in fiction.

A constant state of tensionTension is created by lack. Lack of understanding, lack of closure, lack of equilibrium or peace. When your readers have questions, that creates tension. When they need to know what happens next, that is tension.

Masterful writers keep their readers in a constant state of tension. And that’s a good thing.

But here’s something to keep in mind: our characters may be tense, but that doesn’t mean readers are tense in response. A character with a tightened fist or clenched jaw does not ensure readers will respond in the same way. And that might not even be the desired response a writer is hoping for.

What the characters think, feel, and show must be carefully executed to evoke the desired emotional response in readers.

The tension we writers want to focus on most is the tension our readers feel. If we don’t keep them in a state of expectation, they’ll start nodding off, and next thing you know, our novel slips unread to the floor.

That means getting tension on every page. How is that possible?

By focusing on microtension.

The difference between tension and microtensionJust what is microtension? Just as the prefix suggests, it’s tension on a micro level, or in small, barely noticeable increments. Your big plot twists and reversals and surprises are macro-tension items. And those have great potential for sparking emotional response in readers. But microtension is achieved on a line-by-line basis.

For example, anytime a character has conflicting feelings, you have microtension. Microtension can be small, simmering, subtext, subtle. Even the choice of words or the turn of a phrase can produce microtension by its freshness or unexpected usage.

Microtension is created by the element of surprise. When readers are surprised by the action in the scene, the reaction of characters, or their own emotional reactions, that is successful microtension at work.

A sudden change in emotion can create tension. A character struggling between two opposite emotions creates tension. Odd contradictory emotions and reactions can create microtension.

Microtension is created when things feel off, feel contradictory, seem puzzling.

Maybe that sounds crazy, but if characters are sitting around happy with nothing bothering them, you have a boring scene that readers will stop reading. Sure, at the end of your book, you might have that wonderful happy moment when it’s all wrapped up and the future, finally, looks bright, but that’s why the book ends there.

Let’s take a look at part of the opening scene of the 2012 blockbuster best seller Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn. The characters, Nick and Amy Dunne, greet each other one morning—like any married couple, we’d expect.

At the start of the scene we get this strange thought in Nick’s head that seems to be interrupting the typical “wake up in the morning” ritual we tend to experience each day:

The sun climbed over the skyline of oaks, revealing its full summer angry-god self. Its reflection flared across the river toward our house, a long blaring finger aimed at me through our frail bedroom curtains. Accusing: You have been seen. You will be seen.

The sun is not warming and bright and inviting; it’s angry, accusatory. We immediately are piqued with curiosity—What is Nick feeling guilty about? What has he done? That alone might get many readers turning pages.

Action in a scene creates tension all by itself. Any element of mystery in the plot makes readers want to know what happens next. But masterful writers will also embed words, phrases, and lines of microtension that charge the pages. Describing the sun as angry and watching him, juxtaposed with the word frail (which perhaps hints at the condition of his marriage or his ability to keep his secrets hidden), is microtension.

Note the interest and tension created by the unexpected and incongruous thoughts and reactions Nick has as this moment plays out:

It was our five-year anniversary.

I walked barefoot to the edge of the steps and stood listening, working my toes into the plush wall-to-wall carpet Amy detested on principle, as I tried to decide whether I was ready to join my wife. Amy was in the kitchen, oblivious to my hesitation. She was humming something melancholy and familiar. I strained to make it out—a folk song? A lullaby?—and then realized it was the theme to M.A.S.H. Suicide is painless. I went downstairs.

I hovered in the doorway, watching my wife. Her yellow-butter hair was pulled up, the hank of ponytail swinging cheerful as a jump-rope, and she was sucking distractedly on a burnt fingertip, humming around it. She hummed to herself because she was an unrivaled botcher of lyrics. When we were first dating, a Genesis song came on the radio: “She seems to have an invisible touch, yeah.” And Amy crooned instead, “She takes my hat and puts it on the top shelf.” When I asked her why she’d ever think her lyrics were remotely, possibly, vaguely right, she told me she always thought the woman in the song truly loved the man because she put his hat on the top shelf. I knew I liked her then, really liked her, this girl with an explanation for everything.

There’s something disturbing about recalling a warm memory and feeling utterly cold.

Amy peered at the crepe sizzling in the pan and licked something off her wrist. She looked triumphant, wifely. If I took her in my arms, she would smell like berries and powdered sugar.

When she spied me lurking there in grubby boxers, my hair in full Heat Miser spike, she leaned against the kitchen counter and said, “Well, hello, handsome.”

Bile and dread inched up my throat. I thought to myself: Okay, go.

What made you stop and think, essentially, “Wait … what”? That’s how I spot microtension. We expect a couple acknowledging their anniversary to be happy and full of warm thoughts. What do we find here?

First, the mention of carpeting Amy detested. That’s odd he’d think about that. Then he’s hesitating before joining her. It makes us wonder why. She’s humming a tune, and instead of a romantic song or one that has pleasant lyrics or visual associations, it’s a song about suicide from a TV series about medics in the Korean War. Suicide? Wait … what?

Nick doesn’t spend time thinking about this but instead sneaks a glimpse at his wife, who seems the picture of childlike innocence with yellow-butter hair and a ponytail swinging “cheerful as a jump-rope.” This image and the author’s choice of words is incongruous with the song and her sucking on a burnt fingertip, followed by Nick feeling “utterly cold” at this warm memory of his wife botching lyrics.

We already know there is trouble in paradise by the things Nick notices about Amy and his behavior, thoughts, and reactions to her. Again, we have a contradictory, unexpected reaction when Nick, thinking of how sweet his wife would smell in his arms and her apparently friendly greeting to him, prompts bile and dread to inch up his throat.

Wait … what? Readers now are asking questions and wanting answers. What is he dreading? Amy seems to be perfectly pleasant and cheerful, so why is Nick reacting like this?

A few paragraphs later, we learned Nick borrowed a lot of money from Amy to open a bar in town, and he’s feeling guilty about this. He’s determined to make it a success, and off he heads to work. Here’s the high moment at the end, where the unease and microtension ratchets up ten notches.

As I walked toward the bar across the concrete-and-weed parking lot, I looked straight down the road and saw the river. … The river wasn’t swollen now, but it was running urgently, in strong ropy currents. Moving apace with the river was a long single-file line of men, eyes aimed at their feet, shoulders tense, walking steadfastly nowhere. As I watched them, one suddenly looked up at me, his face in shadow, an oval blackness. I turned away.

I felt an immediate, intense need to get inside. By the time I’d gone twenty feet, my neck bubbled with sweat. The sun was still an angry eye in the sky. You have been seen.

My gut twisted, and I moved quicker. I needed a drink.

Here we see, as Nick heads to his bar, not a pretty garden of colorful flowers but a “concrete-and-weed parking lot” and a river running “urgently” with strong “ropy currents.” These are deliberate images and word choice by the author meant to reflect Nick’s mind-set and mood.

Concrete and weeds conjure up hard, ugly things. The river isn’t gaily rippling or gently flowing, it’s described in a way that we subconscious sense Nick is feeling—some sense of urgency and distress, and ropy currents make readers picture ropes, which are constricting, even violent. Strong ropes evoke images of people or things tied up, restrained, or perhaps whipped or beaten. Nothing there implies joy, peace, beauty, contentment, or happiness.

Then, strangely, Nick sees a line of men walking single file (wait … what?) beside the river, which evokes a prison gang, with eyes fixed on the ground, their bodies tense. And they are walking “steadfastly nowhere.” How in the world does he know that? Why are they in this scene? Why would Nick look at them?

It’s all very intriguing, giving us the feeling that Nick is reading into them what he is presently feeling—trapped, imprisoned, made to “toe the line” as a dutifully faithful husband, tense, but wandering nowhere, as if being pulled by an invisible current against his will … all because of something he’s done that we have yet discovered.

His pressing need to go inside creates more microtension, as does his neck bubbling (interesting choice of word to tie in with the river water) with sweat. He notices again the angry eye of the sun and is reminded that he’s been seen, prompting his gut to twist and need a drink—first thing in the morning.

We are now really itching to know: What has Nick done that has made him so tense and fearful?

Not a lot of action has occurred—Nick’s woken up in the morning, greeted his wife, and gone to his bar—but look at all that’s been implied yet not shown or told. We don’t get Nick thinking, I’m really worried about my marriage. I’ve been cheating on my wife, and if I get caught my life is in the toilet. I don’t know if I can keep up this ruse of being the loving, devoted husband. Amy is controlling and weird and crazy, and I made a mistake marrying her.

Flynn could have told us a lot through Nick’s thoughts to explain what all these strange feelings are all about, and that’s perhaps what an amateur author would do. But instead she chose to pack her opening pages with microtension that create more questions than provide answers.

At any given moment, we humans feel a number of different emotions, and they often clash. By going deep into your characters and drawing out that type of inner conflict as often as possible, you can bring microtension into your scenes.

Yes, you will have outer conflict as well (hopefully a lot of it). But by adding the inner conflict, you can ramp up the microtension.

Try to avoid common expressions we’ve all heard before. Think past the obvious first emotion and find something deeper, something submerged and underlying the superficial emotion. Strive for the unexpected.

3 ways to add microtension to your scenesDialogue: Examine each line of dialogue. Take out boring and unnecessary words and trivial matters. Go for clever. Find a way to give each speaker a unique voice and style of speaking. Subtext can hint at what characters are really feeling below the surface, and that creates mystery. Keep in mind the tension is in the relationship between the characters speaking, not in the information presented.

Action: This can be with any kind of action—high or low. Even a gesture is action. So think how to make an action incongruous. What does that mean? Real people are conflicted all the time. Real people are complex, inconsistent. So having a character react in an incongruent manner, and having incongruent developments in the storyline, will add microtension. Have things happen and characters react in ways the reader does not expect. And, most important, show everything through the POV character’s emotions. Action will not be tense unless the character is experiencing it and emotionally reacting to it.

Exposition: Exposition is the prose, your writing. It is the way you explain what is happening as you show it. It includes internal monologue. Find ways to add those conflicted emotions and create dissonance. Show ideas at war with one another. Use word choices that feel contradictory. Find fresh, different ways to describe common things.

The emotions readers feel when an author is a master at microtension are intrigue, curiosity, excitement, fascination, unease, and dread. In other words, when you sense something coming around the corner and you don’t know what it is, it triggers emotions. Depending on the story and genre, those might be fear, anguish, giddiness, mirth, terror, or titillation.

If a writer masterfully creates microtension, she is going to get readers committed to her story and her characters, feeling tense all the way to the last line of the novel.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, check out C. S. Lakin’s online course 8 Weeks to Writing a Commercially Successful Novel. It includes more than 10 hours of lecture and dozens of scenes from bestselling novels analyzed, plus handouts and worksheets galore—for fiction writers of any level.

August 3, 2021

The Importance of Curiosity and Tension to Storytelling

Photo by eberhard grossgasteiger from Pexels

Photo by eberhard grossgasteiger from PexelsToday’s post is excerpted from The Eight Crafts of Writing by Stefan Emunds (@StefanEmunds).

“Make the audience put things together. Don’t give them four, give them two plus two.”

—Andrew Stanton

“Drama is anticipation mingled with uncertainty.”

—William Archer

Your goal is to get total strangers to read the first chapter of your book and hook them enough to read the second. And the third. And the fourth. And so forth. But what makes readers open a book and keeps them turning the pages?

In part, curiosity and tension.

Curiosity is an intellectual affairPeople are curious souls. They wonder how it feels to walk in someone else’s moccasins for a moon. Or in someone else’s high heels. Is the grass really greener on the other side? How does it feel to have no garden? How does it feel to have an entire park as a garden? How does it feel to have a house in the middle of a desert? People read to experience things they can’t or don’t want to encounter in real life.

Curiosity manifests in two ways:

Expectation or anticipation (positive curiosity)Worry (negative curiosity)Writers maintain readers’ curiosity by raising questions, in particular, the global story question: Will the protagonist succeed or not?

But don’t just raise any questions. Questions need to come with challenges.

To maintain reader curiosity, you can raise and answer multiple questions on multiple levels—for example, a story question, an act question, a chapter question, and a scene question. Try to keep two to three questions open at any given time. Raise two questions in your opening and answer one. Then, raise two new questions and answer one. Then raise two new questions and answer two.

Take the world of TV and movie writing: screenplays have seven or eight sequences, and each sequence begins with a challenge/question and ends with an answer—success or failure. You can do the same thing with chapters and acts.

You can boost reader curiosity with dramatic devices, like a cliffhanger. A cliffhanger separates a question and delays the answer with a chapter, act, or even book break.

Tension arises from the discrepancy between want and realityTo feel tension, readers must sympathize and/or empathize with characters or at least want to know what happens to them. Dwight V. Swain once said, “Your reader must care what happens. Otherwise, he won’t worry, and worry is the big product that a writer sells.”

Tension manifests in two ways:

The reader wants something to happen—e.g., the protagonist succeeds.The reader wants something not to happen—e.g., that the protagonist fails.The antagonist and adversity keep the protagonist from realizing her want. The greater the power divide between the protagonist and antagonist, the greater the tension.