Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 64

February 15, 2022

A Year Without Social Media as a Freelance Writer

Photo by ready made from Pexels

Photo by ready made from PexelsToday’s post is by SaaS copywriter Alexander Lewis (@alexander-j-lewis).

I became a full-time freelance copywriter and ghostwriter in spring 2016. Over the years, I’ve used social media to source new leads, maintain client relationships, distribute articles, and grow my newsletter. I’m convinced that these channels—LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, in particular—are some of the most effective marketing tools ever created, especially for writers.

But like many creatives, I’ve also found social media to be a major source of unwanted distraction. These channels are magnets for attention, often pulling me away from my most important work. A few years ago, I began taking this pull more seriously. How much more writing could I accomplish in a week without social media’s constant drag on my time and attention?

I tried many short-term solutions. I took social media fasts. I deleted the apps from my phone. I logged out of my profiles so that I would have to type the password each time I wanted to log in.

None of these tactics offered a permanent fix. At best, they helped me push through a single day, week, or (occasionally) month. In the end, I always returned to the habit of mindless news-feed scrolling.

In December 2020, I chose to try a more drastic approach. I took a one-year break from social media (which officially concluded in January 2022). Here’s how a year without social media impacted my writing business.

The pros of a year without social mediaThe first few months of the experiment were scary. My blog readers, email signups, and cold leads slowed substantially down. I wondered if I’d be forced to quit the experiment early just to keep my writing business alive.

Since I no longer had social media for content distribution or marketing, I had to find new ways to get my name and articles in front of my ideal readers. My two primary marketing tactics became writing guest posts (mostly for tech and business blogs) and SEO articles on my copywriting website. And these tactics turned the fate of my experiment around.

Almost every new client last year found me through Google or referral. At the beginning of my experiment, I was receiving about 3 website visitors per day from search engines. Today, that number is north of 40.

This traffic helped me grow the writing business. I was able to double my small email newsletter last year, as well as grow my writing revenue by about fifty percent.

Most notably, I believe my writing improved last year. One understated problem with social media is its ease of publishing. Before my break from social media, I might have a strong idea for an article. Instead of doing the hard work to flesh the idea into an article, I would often take an easier route: write a short synopsis, which I would publish as a tweet.

Taking a break from social media helped me develop greater patience with my ideas. If I liked an idea, I didn’t have the option to publish the one-sentence version. I was forced to sit with it, research it, and ultimately turn the idea into something of substance. Only then could I release the idea to the world.

The result: I was prolific in 2021. Beyond having more client work than any year before, I found the time to write and publish about forty articles across my blog and various guest posts. All this distraction-free writing culminated—I believe—in stronger prose in both personal and client projects.

The cons of a year without social mediaBefore launching the experiment, I wondered if my writing business would even survive without social media. Twitter, LinkedIn, and Facebook Groups were such easy forms of marketing and distribution. What would be the cost of ignoring all this low hanging fruit?

Obviously there was no way for me to split-test my year without social media to see what I missed. I can’t name the exact benefits I sacrificed last year because I don’t know.

What I do know is that social media used to be an easy place to grow my email list. Before the experiment, I regularly posted about my newsletter. Every mention—especially on LinkedIn and Twitter—resulted in several immediate email signups. By giving up social media, I also gave up that turnkey approach to finding subscribers. In 2021, I suspect that I worked a lot harder to earn each subscriber compared to the years before.

I also lost easy distribution last year. I was proud of many articles I wrote in 2021, but I had only one place (my newsletter) to share them. I didn’t miss the likes and comments of social media so much as I missed knowing that I had an easy way to tell the world about my latest article.

The biggest drawback of my social media break became clear after the experiment ended. In January 2022, I decided to return to just one social media channel: LinkedIn. The way I see it, LinkedIn offers the greatest benefits to my business, with the lowest drag on my time and attention.

I started publishing regularly on LinkedIn a couple weeks ago and immediately saw what I’d been missing for a year. It’s been like turning on a faucet. Almost every time I share a copywriting article on LinkedIn, a lead reaches out to me via email or direct message. It’s impossible not to wonder how many quality writing gigs I missed last year by disengaging from social media.

My relationship to social media going forwardOn a personal level, I love life without social media. Every writer must strike a balance between deep work and platform building. This experiment taught me that I can indeed sustain (and grow!) my writing business without some of the most distracting social media channels.

For now, I will remain logged out of Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. I will continue to pursue SEO and guest posting as the primary marketing tools for my freelance writing business and newsletter, with LinkedIn reserved as a channel for distributing my latest articles.

As a copywriter, I’ve learned that focus is one of the most underrated strategies in marketing. It’s more effective to go all-in on a few channels than to engage lightly across many. Time to put that theory to practice.

February 9, 2022

3 Shifts You Need to Make to Finish Your Book

Today’s post is by editor, publisher and coach Janna Marlies Maron (@justjanna).

When I first met Cat, she had been working on her book for more than three years, since finishing her MFA program. She was frustrated and discouraged, feeling like she didn’t know what direction to take with her manuscript. She questioned whether anyone would ever want to read her book and, worse, she felt burned and discouraged by her MFA program because she didn’t feel she got the support she needed to write the story she felt compelled to tell. She learned a lot in the MFA program, but not how to actually finish a book. And she wasn’t able to figure out how to make progress on her manuscript without the external structure of the MFA program.

Maybe you can relate, because I hear these kinds of stories from writers all the time. They can’t seem to make progress on their own, without being in a workshop or MFA program. They also get stuck because they are overwhelmed by the amount of material they have, they don’t know how to organize it, and can’t figure out what structure will work best.

The writers I talk to also attempt to get unstuck in similar ways:

You read all the books and articles on writing you can get your hands on, thinking that if you can just unlock some mysterious craft secret then everything will magically fall into place.You attend as many workshops and seminars and master classes as you can, thinking that if you can just get the exact perfect feedback from so-and-so famous author who has all the answers, then you will have all the answers too.You keep doing the same things you’ve always done, thinking that if you just spend more time, work harder, attend one more workshop, or get more feedback, you’ll finally figure it out.There’s just one problem with this thinking: It’s all a version of expecting external solutions, when the reality is that most of the time the solution is internal. You need to make three internal shifts to help you finish your book and become the writer you’ve always imagined: structure, story, and sanctuary. Let’s take a closer look at each element of this framework.

Shift 1: Embrace structureThinking about structure often makes creatives, especially writers, cringe a little bit. You want to write when you’re feeling inspired, when you’re in the mood, or when you feel like it. But the problem with that is you’re making time for your book project in a reactionary way that is sporadic, unsustainable and, ultimately, exhausting.

Instead, embracing structure means planning and finding consistency in your creative practice so that you can truly start to see the progress you want to see on your manuscript.

You can embrace structure in your writing life with these three actions:

Work your why. If you don’t know it already, figure out the WHY behind your book project and your life as a writer. What is the one compelling reason behind writing your book and telling your story? Once you have this, treat it like a vision statement—one sentence that summarizes your WHY, that you can post somewhere you’ll see it everyday, that keeps you motivated to keep returning to your manuscript.Gather your goals. Once you have your WHY, identify 3-5 goals that support your vision. These are milestones along the way toward accomplishing your vision, and completing your manuscript. As soon as you achieve one goal, you know you’re that much closer to the finish line.Safeguard your schedule. Now that you have your WHY and your GOALS, you need to establish a schedule that will support both by planning time to take action. Your schedule should be a calendar that you use every day. You don’t do anything unless it’s on your calendar, and you don’t make plans without checking your calendar first. And, most importantly, you treat all appointments as equal, even appointments that are only with yourself.Shift 2: Love your storyWhen I say “love your story,” it may sound a little cheesy or even a little cliché. But compared to other things you might say you love, like cooking or playing music or spending time with your family, it becomes pretty clear that you don’t love your story in the same way.

Let me explain. If you love to cook, you might spend time searching for new recipes. And when you find one you want to try, you might go out of your way to a specialty grocer to pick up some exotic ingredients that they don’t carry at Whole Foods or Trader Joe’s. Because you love it, you nurture it, and infuse the time you spend cooking with tender loving care.

It’s like one of my clients, Susie, says, “It’s not that my manuscript changed, but that I changed in relation to it. I started to believe, ‘Okay, I can write this. I can finish this.’ And that proved to be way more important to me.”

You can begin to love your story with these three actions:

Develop your draft. Sure, it’s easy enough to generate words, get feedback, and revise. Most writers feel like they have that part down. But if you try to force the material into submission and control its outcome, that’s not a very loving way to treat the project. Instead, how can you listen to the draft and let it tell you what it needs? Can you bring a sense of lightness and play into your work, holding it loosely so that it becomes what it’s meant to be? Master your mind. Your mindset affects you more than you know. It creates the story you tell yourself about the story you are writing. One of the best things my therapist ever did for me years ago was to give me the mantra: The story I tell myself creates the reality I experience. So as long as you tell yourself that your story doesn’t matter, that no one will want to read it, or that you don’t have what it takes to write a book—guess what? It will be true.Invest in yourself. When you hear the word “invest” you might automatically think: money. But investing in yourself is about giving yourself—and your book project—what you need to be successful. That means time, energy, attention, and, yes, sometimes money. If you are neglecting yourself, your skill development, or your creative process, then ultimately you are neglecting your story and you won’t make progress toward finishing your book.Shift 3: Create a sanctuaryIf you hear the word “sanctuary” and think of a physical place, like a church or yoga studio or a botanical garden, in this context I want you to understand it as something you create in your mind so that you can take it with you anywhere you go.

When you do that, you can access the mindset and energy you need to work on your book without worrying about whether you are at home with all of your creature comforts or in a hotel room on a personal writing retreat. You can access it at any place and any time because you have everything you need within you.

You can create a sanctuary with these three actions:

Renew your rituals. Reflect on how you begin any time you sit down to work on your book. Is it rushed? Frantic? Forced? You can shift this energy so that it is calming and uplifting by incorporating rituals as a way to begin your writing time. Rituals are habits in an elevated form, an action you take intentionally that triggers your body and mind, and prepares it for the creative work ahead of you.Cultivate your creativity. As a writer, you are naturally curious and creative, and so you are probably drawn to forms of creativity other than writing. But, again, how intentional is it? I like to think of cultivating your creativity as cross training for your brain. It’s a way to stretch and train your creative muscles so that they are stimulated and ready to get to work when you sit down to make some progress on your manuscript.Watch your wellness. Your physical wellbeing is just as important for making progress on your manuscript as your craft skills and your mental wellbeing. I like to say, when I am not well, my work is not well. Just as athletes train and watch what they eat so that they can perform at their highest level on game day, you need to take care of your body by sleeping well, eating well, moving and exercising every day so that when you sit down to write, you are also ready to perform at your highest level. If you want to have the mental clarity, energy, and stamina required to generate the output necessary for a book-length manuscript, then you must watch your wellness.You may have noticed that there is some overlap in each of these shifts and associated actions. Rituals can support mindset, wellness, and creativity; and investing can support all of those things as well. The framework is intentionally designed to be a layered approach, where one aspect supports the next, building on itself to create a more holistic approach to your book project that allows you to integrate your writing with every other aspect of your life.

It’s so easy to get caught up seeking external solutions to your problems, when the truth is if you take time to get quiet with yourself, you’ll realize that making these internal shifts will have a profound effect on your progress.

After working through this framework and making these three internal shifts for herself, not only did Cat finish her memoir manuscript, but she also told me that she now feels the way she wanted to feel at the end of her MFA program: Like a real artist.

February 8, 2022

3 Things to Ask Yourself Before Writing about Trauma

Today’s post is by writer, coach and editor Lisa Cooper Ellison (@lisaellisonspen). Join her on Feb. 24 for the online class Writing About Trauma.

“Let’s rip it off quick!” My grandmother pointed at the Band-Aid on my knee.

At four, I equated Band-Aid removal with peas, waiting my turn, and going to bed. Still, I loved and trusted my grandmother, so I let her yank it off. After a momentary flash of white-hot pain, I experienced an exquisite relief. Soon after, I adopted “rip it off” as my motto.

Three decades later, during my master’s in counseling, I discovered James Pennebaker’s research on how writing about difficult events improved your health. The trauma survivor in me saw this as a dream come true. So, I began a memoir.

My initial drafting plan combined Pennebaker’s research with Grandma’s sage wisdom. If ripping off a Band-Aid created some relief, churning out one hundred pages of “look what terrible thing happened” would elevate my health and happiness to the Oprah Winfrey level. Bottle that and I’d become the world’s greatest writing coach.

Except, the exact opposite happened. Writing about endless pain depressed me. Eventually, I avoided my writing desk. When I did show up, an essential part of me cried, “No, no, no.” If I forced myself to write anyway, the work felt flat and superficial.

To write sustainably about trauma, you must P.A.CE. yourself.

P roactively engage in self-care. A ctivate your internal wisdom. C hoose wisely and keep it contained. E xplore your stories with curiosity and compassion.P.A.C.E. is an integrative approach to writing about trauma that combines proactive self-care, mindful awareness, and targeted strategies that help writers discover insights and resilience inside their painful experiences.

Activating your internal wisdom (the A in P.A.C.E.) helps you to assess what you should write, when to get started, and how to manage the process before working on painful material. The process can also help you if you’re feeling stuck.

But before you assess, you need to know the difference between journaling and storytelling.

Journals are private places where we record what’s happened to us. Sometimes we share entries with safe people like close friends or counselors, but they’re not meant for everyone. While you might delve deeper into certain topics, there are no rules to follow and no bar to meet when it comes to the quality of your writing. Journaling is a safe way to bear witness to your experiences and develop insights around them—especially if you’ve never shared these moments with anyone.

Memoirs and personal essays are curated stories about transformation that have gone through extensive revision. They’re tailored for a specific audience who will glean wisdom from them. That means you must reveal lessons learned in addition to writing dramatic moments well. Getting these projects to a publishable stage requires critical feedback from writers and editors.

Assess your readinessIf you’re interested in writing personal essays or a memoir about traumatic events, you might have some work to do before your project is ready for a critical eye, let alone the public. Many trauma survivors associate being seen with danger—either because something painful happened when they were seen, or they were not seen in some fundamental way, especially early in life. Wounds around being seen can make workshops and publications feel like a walk through an active minefield.

If you’re interested in writing a story, ask yourself why this experience needs an audience. If your goal is to show others what happened to you, it’s likely you need to journal for a while. This is a normal and healthy part of trauma writing. Early on, we need someone to attend to our wounds. If this is the case, the best audience is a counselor or other mental health professional—not a workshop or writing group. Workshops are designed to help writers improve their storytelling skills. Most writers, no matter how compassionate, aren’t equipped to help you make sense of your pain.

Assess your energy bank accountWhether you choose to journal or work on a formal project, you must manage the limited funds in your energy bank account. Rest, self-care, fun, and supportive relationships deposit energy into this account. Everything else draws from it. Illness communities talk about energy levels in terms of spoons. If we feel great, we might wake up with ten spoons. Experiencing a relapse? Cut that number in half. Our job is to use these spoons wisely by selecting the day’s most important tasks.

As a writer, replace spoons with pens. You’ll spend most of your pens on daily living. A tiny fraction are for your writing life, so use them well. The more emotionally intense the topic, the more pens you’ll need. If you’re writing about a highly traumatic event, allot at least three to five pens, and an additional pen or two for the recovery time you’ll need after you write.

For some of you, this is all you’ll need. But if you take pride in a high pain tolerance and an ability to write about hard things no matter what, there are a few stop signs to watch out for.

Assess your timingYou don’t need to wait for the perfect conditions before working on a tough story, but there are times when writing about trauma won’t serve you. Here are just a few.

It’s too soon: While you can journal any time, stories require enough distance from an event to know what it means—a phenomenon called psychic distance. The amount of time needed to develop psychic distance is relative. For some experiences, all you’ll need is a few days. But if you’re planning to write about a buried-never-spoken-of event, fifty years might not be long enough. Before writing publicly about buried events, work with a trained professional.Part of you doesn’t want to: Motivated writers love to see their work in print, but that doesn’t mean the wounded part of you is ready. Trauma frequently involves a lack of choices or coercion. Forcing yourself to write about painful things can re-enact the trauma you’ve experienced. This can make you hate writing or give up. If part of you is saying no, ask what it needs to feel safe before proceeding.You’re going through a major life transition: Many writers want to capitalize on the extra time a job loss, divorce, maternity leave, surgery, or pandemic had granted them by writing a memoir. But major life changes—even happy ones like a new baby—are stressful, and that stress requires more pens. Your tough times aren’t going anywhere. At these critical junctures, focus on happy times and joyful activities that replenish the pens lost to transition stress.This is your first writing rodeo: If you’re a beginning writer, start with material that has a low to moderate intensity. That way you can focus on developing new skills around scene writing and dialogue rather than how you’ll deal with the pain of reliving a difficult moment.Your writing time butts up to important tasks: Perhaps you write directly before work or before the kids return from school. Writing about traumatic events requires both pens for writing and a recovery period where you’ll rest and regain a full sense of the present moment. If your current writing schedule doesn’t contain any recovery time, rearrange your calendar to create some mental, emotional, and energetic room for your emotionally intense writing sessions.When it comes to writing about trauma there are no gold stars. No one will give you a trophy for writing about unending pain. But you can make yourself miserable and stall what could become a valuable project. Your stories have too much healing potential to treat them like Band-Aids. Proceed gently and P.A.C.E. your writing process.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, please join us on Feb. 24 for the online class Writing About Trauma.

February 7, 2022

Want to Write a Great Novel? Be Brave.

“Bravely Done” by David Camerer is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Bravely Done” by David Camerer is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0Today’s post is by regular contributor Susan DeFreitas (@manzanitafire), an award-winning author, editor, and book coach. She offers an online course, Story Medicine, designed to help writers use their power as storytellers to support a more just and verdant world.

For the recent launch of my new online course, Story Medicine, I interviewed one of my mentors, Jennie Nash, a seasoned book coach and the founder of the Author Accelerator book coaching certification program. When Jennie and I work with fiction writers, a big part of our focus is character arc, and in the course of this conversation, I noted that great character arcs tend to connect with the author’s own personal journey.

Jennie agreed, saying, “That’s where the power is, because that’s where you connect with your deep-level why.”

At first, that statement may sound just a bit vague. But as Jennie knows, this connection manifests in a very concrete way, in terms of literary craft, in the protagonist’s character arc: the way that character grows and changes over the course of the novel.

I write on this subject a lot, because I believe that a strong character arc really is the key to an emotionally affecting novel, one that will make a strong connection with readers. And over my decade plus as a book coach, I’ve seen it over and over: the strongest, most affecting character arcs are anchored in the author’s own experience.

Say the character arc is about a woman gaining the courage to leave an abusive relationship. For one writer, that sort of arc will basically just be a device, something that’s there to serve the plot—say, of a mystery or thriller. That arc might work well in this regard, but it won’t necessarily cause reader to connect with the story, or find any particular sense of meaning in it.

But if the author has actually been that woman? The same arc can have a great deal of power—the power to truly connect with the reader. The power to make that same thriller or mystery feel hugely meaningful.

Maybe even the power to change the world.

When the protagonist’s character arc connects with the author’s own personal journey, it has a sense of reality, intensity, and nuance that just can’t be faked. That’s because it’s not based on stereotype, hearsay, or other forms of received information. It’s actually based on the truth of that experience—and chances are good that it will carry some of the deepest, most hard-won truths of the author’s life.

Many of us started writing fiction because we didn’t relish the idea of laying bare the real stuff of our lives—the hard stuff especially. And it’s true that it takes courage to “go there,” in terms of writing from the truth of your own life.

But I believe it’s the greatest gift you can give your reader, because in doing so, you can share the insights that got you through the hard stuff, and how you lived to tell the tale.

And this is true whether you’re writing about the actual circumstances of your life or simply circumstances that touch upon them. Which means this holds true even if you’re writing speculative fiction, set in an entirely different world.

For instance, maybe you’re writing a sci-fi novel about a young man whose best friend was kidnapped by interstellar smugglers. One option would be to go with a familiar, recycled character arc: the protagonist who starts off feeling like a coward and goes on to discover his courage and confront the man who kidnapped his best friend.

That’s a character arc we’ve seen many times in Hollywood movies. A stronger tactic with this scenario would be to work out an arc more clearly centered in the truths of your own life.

For instance: Maybe these interstellar smugglers have actually been terrorizing the protagonist’s region of space for years, and this taps into your own history of being bullied as a kid, and the strong emotions you have around that.

Now it’s personal for you—so when the protagonist finally confronts that antagonist, the leader of this gang of smugglers, at the climax of the story, a lot of emotional power will be unleashed, because you’ll be confronting that bully in a way you never got to in real life.

I mentioned before that this takes courage, though, and here’s the tricky part: remembering how you really felt, and really thought, before you arrived at the insight or realization that helped you to overcome the challenges you faced.

Because hindsight is 20/20, and once you’ve figured out the way out of that escape room you were locked in, the answer seems obvious. But it wasn’t obvious when you were stuck in there, trapped not just by your circumstances but by whatever internal block was keeping you from seeing the solution, and finding your way out.

It’s only by sharing the whole truth of the journey—the good, the bad, the ugly, and, hopefully, the transformation that helped you get free—that you can give this great gift to your reader, this gift of the heart, and unleash the full emotional power of your novel.

February 2, 2022

Use Telling Details to Connect Description to Character

Photo by Pixabay from Pexels

Photo by Pixabay from PexelsToday’s post is by editor and author Joe Ponepinto (@JoePonepinto).

Some editors (like me) will occasionally admit they might decline a submission after reading only a few paragraphs. It’s not that they are mean-spirited, or jaded, or working too quickly to get through the submission queue. Instead, their experience allows them to instantly recognize when writing doesn’t meet their journal’s standards. Often it’s in the details—in the lack of telling details, that is.

For example, very often we begin reading submissions that start with a description of a person or a place. Too often the details offered are flat and generic, describing only superficial aspects. Kind of like reading a police report:

The man in the airport had brown hair and blue eyes, and wore a black suit and shiny shoes. He walked briskly toward the shuttle to the international terminal.

This approach creates distance between the reader and the character because it offers no depth, no insight into the person described, and therefore it encourages the writer to adopt an explanatory tone, one that treats the reader as a passive listener who must be educated, lecture style, about the world of the story. But good fiction creates an illusion of real life. If so, then shouldn’t the details of a story be presented in a way that reflects how we discover the world in our real lives, rather than a classroom?

One main key to compelling, immersive fiction is in how details are conveyed. Dull fiction assumes the reader doesn’t know the basics of a scene—if it takes place at a bar, then that bar must be thoroughly described; if it’s a hospital, everyday details about the hospital must be expressed. Good fiction assumes the reader is familiar enough with bars and hospitals to not have to describe them from scratch—only the details that are important to the characters are conveyed.

Which approach is more organic and more effective? Think about how you encounter the world. What things do you notice and what things do you not? Human beings are evolved to notice what is out of the ordinary. We tend to pay less attention to the things we see on a regular basis. This allows us to move forward more efficiently in our lives—imagine what it would be like if we had to pause and consider what the red, yellow, and green meant on a traffic signal every time we encountered one. But because we have seen these signals many times before we don’t have to think about what they mean.

That’s a simple example, but consider how this applies to fiction. Stories that offer the surface details treat readers as though they don’t know what a traffic signal is for. They tend to describe everything in a scene, even the details that don’t matter:

At the party, Sue stood against the green wall, watching. There was a landscape painting across from her. She watched people choose beers from the blue ice chest and food from the spread on the linen-covered table.

That may be real, but it is not life. Do we need to know that the wall is green and had a painting hung from it, or that the ice chest is blue, or that there is beer and food at a party? What does this tell us about Sue? Not much. The writer needs to connect Sue’s surroundings to her character. Also, the delay created by overdetailed description works against the need of a story to move forward.

Good stories concede the banal and instead offer details that have deeper meaning. The writer considers, “What would the character notice and why?”

Let’s go back to that man in the airport. If you’re in an airport you probably pass hundreds of people on your way to your gate. You can’t notice them all, so what about this man makes him stand out?

The man in the airport seemed to be watching me.

You don’t have to describe his height, weight, hair color, eye color…not until they matter. What matters at the start, and what the character notices, is that he is watching. It’s out of the ordinary. It portends possible danger, or at least something unusual.

And as for Sue:

At the party, Sue found a niche away from the crowd, too shy to talk to anyone. These were not her people. But knowing them could mean a big break in her career.

We no longer know what the room looked like, but we know several important things about Sue. Which will lead to the more interesting story?

This is a concept I first encountered reading James Wood’s How Fiction Works. It’s another way of describing close third person POV, but I like the term “telling detail” because it reminds the writer that the details need to inform us not just about what the character saw, but why they mattered—why they are “telling.” And that leads to character depth, the kinds of characters that populate good fiction. We learn about them subtly, through their reactions—how they act and speak in response to the world around them, and the situations in which they find themselves. If fiction is an illusion of real life, then you have to give your reader both parts—the real and the life. It often makes the difference between a dull story and an engrossing one.

February 1, 2022

When a Writer Dies: Making Difficult Decisions About the Work Left Behind

Photo by Tara Winstead from Pexels

Photo by Tara Winstead from PexelsToday’s post is by editor and media consultant Eric Newton (@EricNewton1).

Nine days before my wife died, she forwarded me a Brevity post, The Death of a Writer, which asked:

Who is going to deal with your literary legacy, and what do you want done?

My wife wrote, “…interesting re what to do…”

She added a lifesaver emoji.

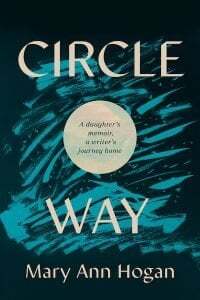

My wife, Mary Ann Hogan, journalist and teacher, died June 13, 2019, her “tango with lymphoma” ended, her life’s literary work unfinished.

Her manuscript explored her relationship with her father, William Hogan, longtime literary editor of the San Francisco Chronicle. Though he spent his life writing about books, Bill Hogan never wrote one of his own.

Mary Ann died thinking her book would redeem them both.

Now what?

In The Death of a Writer, Allison K Williams reported what she did as a friend’s literary executor. Read everything, she advised. Get help deciding what needs to be published.

So I read everything. My wife’s private journals, texts, social media, photo captions, drafts, published work, all of it. Not to snoop, as Williams noted, but to separate the beauty from the garbage.

Took a year. Could have taken longer.

Literary executor is one thing; grieving husband is quite another. Her death had transformed me from an experienced editor into a forgetful, fragile widower crying rivers without warning. Every time I learned something new—and even in a 40-year relationship, there were a few surprises—I had to slow down to digest them.

A word of advice. It would have been easier if we had talked more about her personal journals and communication beforehand. If you are a writer, yes, get a literary executor of one type or another. But talk about where the lines should be.

My wife’s friends and writing partners agreed to help me read and judge what to save for the book or elsewhere. Then there would be drafts of the book to react to and fact-check. Her posse was more than willing. Mine, too.

We puzzled over things such as:

Should the final chapter be in my voice or hers? Both, we said. I would not pretend to be her. But I would quote her all the time, and we found those quotes.What about the references to mental illness? She talked about panic attacks and flying thoughts, but never named the various diagnoses. What about wine? She talked about how she and her father all were big drinkers, without details. Leave it as she wrote it, we said.What about the title? Circle Way came from the posse. Larger illustrations? That idea came from her writing mentor.Rewrites? Mary Ann had created a lyric essay that jumped around like Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, becoming at times a duet with her late father’s journal entries. This mosaic, we said, is best as is.There’s more of her work to publish, in time, and now that we have a system, it can happen.

Finishing Mary Ann’s manuscript was not as hard as finding the right publisher. Parts of Circle Way had won three writing competitions. Publishers said it was “beautiful.” They also said it was “too literary” for the commercial marketplace.

My promise to my wife—to finish her book—felt shattered.

But then a writer friend suggested hiring Jane Friedman. With her help, I decided I wanted a hybrid publisher, in between traditional publishing and self-publishing. Jane recommended one, as well as an agent, to review the contract.

Lucky me. The publisher, Wonderwell, has been spectacular. Smart ideas for adding more art to the book. A fantastic, innovative design. Solid editing. Ways to get books when supply chains break. Every deadline met, the book will be in stores Feb. 15. Reviews to date are good.

In all, the project involved at least 50 people; our sons and their partners; a dozen writer and editor friends; neighbors; an art center; colleagues who scanned and sorted images; and the many who comforted me whenever I fell apart reading Circle Way aloud.

One friend talked about how Mary Ann’s death was a miracle. She died in the family house, in the arms of her husband, sons and dog. She planned her own memorial. Wrote her own obituary. Talked with everyone. Went over her book one last time.

Bookshop / Amazon

Bookshop / AmazonNow Circle Way is real, her book “about the people who can escape from prisons of their own making, and the people who can’t.”

“You know what,” she said one day with a grin.

“The worst thing about dying is you can’t tell people what to do anymore.”

“Don’t worry,” I smiled. “You’ll find a way.”

And she did.

January 31, 2022

Yes, Writers Need to Hear the Hard Truths. But Warnings Can Go Too Far

“Inspiration Arch Plaque” by Bold Frontiers is licensed under CC BY 2.0

“Inspiration Arch Plaque” by Bold Frontiers is licensed under CC BY 2.0Today’s post is by author Shannon A. Thompson (@AuthorSAT).

As an author, program librarian, and writing instructor, I’ve been thinking a lot about my responsibility as a speaker to educate versus inspire. The two go hand in hand, as they should, but I’ve noticed the tone of conference programming has changed over the years.

When I attended my first conference in 2012, programs were focused on the basics of writing and networking. Since then, conferences near me—and now online—have become more sophisticated, offering programs for seasoned writers as well as newbies. Most notably, getting a behind-the-scenes look at the state of the publishing industry has become popular, especially due to changes from the pandemic. Conversations about how to query have become focused on who not to query, the horrors of querying, the worst of the worst. That might be followed up with a discussion dedicated to rejection, in brutally honest fashion.

While warning each other is necessary—especially when it comes to predatory practices or people—I do wonder what happens when we spend too much time on the negative. I myself recently attended a conference where over half of the lineup was dedicated to the pitfalls of publishing. Even a program that I thought would be inspirational had a discouraging tone. After watching three of the five programs I had registered for, I gave up. I closed my laptop and just sat there, staring into the void.

“Why am I doing this?” I thought. “Publishing is impossible. A game of luck. I can’t succeed at anything. My genre is wrong. My age category is wrong. Everything is wrong.”

Warning each other is good. Necessary even. But what happens when we scare artists away from even trying? If I am leaving panels discouraged—when I have more than ten years of publishing under my belt—how are newbies feeling when they hear this information?

As a speaker, I want those who attend my programs to feel uplifted, energized, and excited. I admit that I didn’t always know how to do this. Many years ago, when I was invited to guest speak about my writing journey, I spoke about my trials and tribulations. When I opened the floor for Q&A at the end, a teenage girl in the front row raised her hand first. She asked me, “Why should I even bother?”

Whereas I thought I had been inspirational by sharing all the hardship I had been through, it had frozen a teen writer in her boots.

I had never felt so terrible. Discouragement was not what I wanted my audience to take away from my speech. I knew right then that I needed to correct my speaking style.

Over the next few weeks, I did a deep dive into what inspired me to write when I was first starting out. I thought back to when I told my dad I wanted to pursue writing. He didn’t sit me down and say how hard it would be, how much rejection I would face, my mediocre chances, etc. He knew I would face that on my own and keep going if I truly wanted that dream. He simply told me he believed in me. The next day, I sat down and wrote—and wrote, and wrote again.

I made a lot of mistakes along the way. Heck, I still do. But making those mistakes was part of the journey. If I had known everything I knew now about publishing at the beginning of my writing career, I can’t say I would’ve attempted to pursue my dream. The weight of the future might’ve felt like too much to bear, when really, I needed to focus on creating and exploring (instead of what could go wrong). Learning came with the territory. Networking, too, weaved its way in, and slowly, my understanding took shape.

When I think back on my first conferences, I remember so many more success stories. How I got my book deal. How I got my agent. How you, too, can organize your writing space, your book, your dreams, and make them a reality.

I learned more about the negative side when I was ready to learn, and a lot of being ready required real-life experience. There’s only so many craft books you can study before you must write your first sentence. You can read all the rejection stories in the world, but that won’t stop you from getting rejected when you finally put yourself out there. You may know how other people have reacted, coped, and kept moving, but that is a unique experience to you that you will learn with time.

Sometimes I worry for the writer who attends a conference for the first time and hears discouraging conversations over and over. Yes, those discussions are important to have. But hope is a powerful thing. I don’t want the world to miss out on fantastic art because a writer left a program wondering why they are even trying. To make that happen, we need more encouragement. More dreaming. More “Yes, you can! I believe in you. Here’s how you can succeed, too.” Our educational programs can also be inspirational.

January 25, 2022

What Kind of Book Translates Well to the Screen?

This article was first published in my paid newsletter for authors, The Hot Sheet.

Given the increase in book-to-screen deals in recent years, and the tendency of the TV/movie industry to build off existing intellectual property, it’s natural for authors to wonder if their own work is suitable for adaptation—or if they can increase their chances of writing something that will be adapted. In a panel last year at the virtual Bologna Book Fair, several players in the industry discussed what they look for in projects.

Compared to scripts, books might have a better chance of becoming a recommended project. Annie Nybo, a reader for Netflix, sifts through more than 200 potential projects in a year for the streaming service. Her job requires her to read a book or script, write a three-page summary or synopsis as well as a one-page analysis, and rate the project on five criteria. Those criteria include premise, structure (hitting the plot beats), story line (how that plot is working), character, and dialogue. Even for books, Nybo is able to rate dialogue based on how the characters speak and if they sound unique (versus everyone kind of sounding alike).

Last year, Nybo read 215 scripts and books combined and recommended eight of them. That’s about a 4% acceptance rate for projects coming to her. As far as books specifically, she read 22 and recommended four. That’s a 14% acceptance rate and half of what she recommended. (Stand proud, authors, agents, and publishers!)

Nybo tends to start by first analyzing the premise when recommending projects. “We all have to write loglines and summarize a whole project in one sentence, and so for me, finding a project where the premise is the conflict is really important.” As an example, she offered To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before, in which the main character’s secret love letters somehow get mailed to each of her five crushes: that’s the premise and the conflict.

It doesn’t matter how many copies the book has sold. Nybo said if the book is popular or has an established following, she has to take that into consideration when thinking about the adaptation, especially when there’s a plot point she doesn’t think will work well for the screen. If the fans are very invested in the story, it could be more challenging to adapt. “There’s more room to shift things when you don’t have an enormous audience,” she said.

Characters are critical. Caterina Gonnelli, EVP of content at Xilam Animation (France) said, “We want authentic characters and characters who are really moved by a strong drive and a clear drive. For children’s content we would want this character also to embody positive character traits—which does not mean that he or she is flawless. Of course we also want flaws, because otherwise there is no salt in the recipe.” Speaking again to children’s work, she added that the themes need to be clear, but not preachy, and the character’s trajectory must be clear. “What doesn’t work for us is what is static,” Gonnelli said. For example, a story might be static because there isn’t sufficient action or there aren’t any turning points or surprises for the characters.

Ellen Doherty at Fred Rogers Productions agreed and added that some stories just don’t pop. “You don’t get to know enough of the character or the world,” she said. “Sometimes there’s just no growth.” The characters are so important that if they’re strong enough, what might at first appear as a very local or regional story can in fact be adapted into something universal and appealing for global audiences—regardless of the source country of the material.

How loyal an adaptation should remain to a book—and how much the author ought to be involved—remains an open question. Gonnelli said, “We could debate for hours.” On the one hand, she said, one can argue that the author is in the best position to know the characters and the world they’ve built. But one might also argue distance is required to produce the best adaptation. “I guess what is really key is the relationship—to build a relationship that is based on trust, mutual trust—and for that you need to factor in a lot of time,” she said. She warned that if producers totally skip looping in the author—partly to offer reassurance that the book is in good hands—then there will be trouble. “You’re in a lot of anxiety from both sides.”

Doherty said, “That relationship between the producer and the author is key.” Ideally, the vision for the TV or film version can be built together during the development phase, so that when production starts, there’s already been a meeting of the minds and everyone knows what’s going to happen. However, Doherty said, “Ultimately when it comes to a TV version, for me the producer has to have the final say because we know our medium the best. I have seen instances where the author has too much control and the translation to the new medium doesn’t work so well.”

It’s more common than ever for producers and studios to find ideas and stories by following creators on social media. This is especially true in the case of graphic novels, comics, and illustrated children’s work. Doherty said there’s now a “profusion of opportunities” to find content on social media. Doherty said, “To follow individual creators that way is really interesting because you get to see more of their personality, you get to see maybe their playfulness and things that are in process, and I really like that. There are people that I’m watching to see what they do next; I’m checking out their books as they go.”

How can an author increase their chances of adaptation?All panelists agreed that they look for stories that are the best example or expression of their genre. Nybo and others look for that blend of familiar and fresh, where the author clearly knows what genre they’re working in and hits those structural points but includes interesting and surprising twists and turns. Perhaps it goes without saying, but the quality of the writing on the page doesn’t matter. Rather, it’s more important that the story is “working on all cylinders,” according to Nybo. Excellent literary writing can’t translate to the screen as well as snappy characters.

Angela Cheng Caplan, president and CEO of Cheng Caplan Company, said (in a separate panel at Bologna): “Honestly, it’s all about the narrative. It’s really about the author’s narrative. We really, really pay attention to that. What is the author’s back story? What is the author trying to say? I’m always big on context. And I always have the authors that I work with put together an author statement that really sort of addresses why they’re the only person in the world to tell this story—what exactly it is that they’re going through that makes this relevant for this moment in their lives and how it can relate to everybody else.”

She also offered a warning: “Within the past year we’ve actually started looking at potential clients and their social media. I’m very, very aware of when someone is a troll, quite frankly—if they’re trolling for the good or trolling for the bad at some point in time. Whatever energy is put out there sort of comes back in some way, shape, or form. So I would say for authors who are out there trying to create publicity for themselves … be very aware of the kindness or lack of kindness you’re putting out into the world.”

If you enjoyed this article, consider a free trial subscription to my paid newsletter, The Hot Sheet.

January 19, 2022

How to Plan and Host Worthwhile Online Book Events

Photo by Andrea Piacquadio from Pexels

Photo by Andrea Piacquadio from PexelsNote from Jane: Tomorrow I’m hosting a class taught by Barbara Linn Probst, Book Publicity 101, to help authors understand when and how to hire professional help for a book launch.

Since the pandemic arrived in early 2020, the entirety of the publishing community has turned its eye toward online events as a key way to spread word of mouth about books. And a lot continues to ride on the success of these events. Yet how many authors have been effectively trained in staging a meaningful online event—especially one that translates into sales?

I reached out to some of the most experienced and astute authors and marketers to share their best practices for online book events, regardless of the platform you’re using.

First, decide what you want from the event.Former literary agent Mary Kole (who runs the Good Story Company) says you need to decide if you want readers or if you want sales—the two are not necessarily the same thing. “By hosting a great event where you have hundreds of attendees—but no sales—you have maybe gained some readers. They came, they saw, they enjoyed, they maybe signed up for your email list. Is this enough?” Sometimes it is, Kole says. But you need to be clear about what you’re hoping to achieve so you can adjust how you frame the event from the start and what you ask people to do.

Novelist Hank Phillippi Ryan of Career Authors says, “A book event does not necessarily need to translate into sales at that very moment. If an author can drum up interest in their new book and themselves, and create a general excitement about it, and a sense of anticipation, I think that’s very helpful. Then the next time the reader sees your book, they remember, Oh—I just saw that! Or I just heard about that.”

As marketers are fond of saying: People buy books they’ve heard about, and events create word of mouth and a needed impression. If successful, the event will endear you to readers and increase the future likelihood of a sale. Novelist Caroline Leavitt recommends, “Be casual. Be yourself. Readers want to see the real you, so the more unpracticed and unrehearsed you sound, the better. If you can be warm and funny, readers will love you, and they will want your book that much more!”

Build marketing support or find partners for your event.Author Angela Ackerman of Writers Helping Writers suggests reaching out to your existing audience and letting them know you’re planning something fun. In other words: form a street team or launch team. Provide a signup form that lists all the ways your team can help; then they can decide how to support you. Ackerman says she and her co-author rely on the teams’ blogs to point to the event, a strategy she describes as lots of windows, one house. “I craft the posts in text and HTML to make it easy [for them] to drop in, and create three different versions which I split into three groups so not every blog has the same images and content.” Also, she says, be sure to offer team members a thank-you gift afterward.

Rachel Thompson of BadRedhead Media offers a caveat regarding this approach: “I caution any author to not jump into this unless they have a body of work behind them,” she says. “I didn’t start my team until I had published four books.” That said, if you have a recognizable name already—or if your book is on a topic that readers can quickly and avidly get behind—she says it’s possible to create a team and people will jump right in.

If a launch team or street team is out of the question for you, look for other like-minded partners. “I think an online launch is all about increasing your reach,” says novelist Kristy Woodson Harvey. “Teaming up with other authors, influencers, bloggers, and, of course, a favorite indie bookstore for joint events can help grow the potential audience. And if you have a regional bookseller association that would get involved (SIBA, MIBA, etc.), so much the better.”

Likewise, novelist Karen Karbo suggests, “Being in conversation is more interesting than a talking head. If you can talk with someone with her own following, even better.”

Determine the event theme, content, and structure.Ackerman says that she and her co-author try to do events with an emotional pull, so they look at three components for each event.

Offering entertainment. This isn’t a hard one to understand: people want to participate in something fun. Ackerman says, “We think about why our readers are online, what sort of escapism might appeal to them, and how can we cater to that. People tend to respond to creative things that pull them out of their day-to-day as long as it’s easy to do.”Adding value. Often, this takes the shape of a giveaway and gives people a reason to attend. More on this below.Satisfying a need. Ackerman says, “As human beings, we have common needs, like connection, belonging, fellowship, creativity, etc., and if you can find a need that your audience is receptive to, you can build a theme into your event they will connect to emotionally and so rally behind. This makes them more motivated to participate in the event and share it with others, which in turn means visibility and books sold.”Whether it’s better to use Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, Zoom, or something else will depend on where the author has a following or is otherwise comfortable engaging. Consider these factors:

“If the event takes place on social media, think about what the audience is there for. Entertainment? A break from routine and work? Information?” Ackerman says. “What do they like, and what will catch their attention on that platform?”Facebook launch parties. Thompson says these aren’t likely to sell a lot of books, “yet you’ll connect with your readership and build relationships and visibility for future sales.” If you have a street team, you’ll gain new membership, new followers on other channels, and newsletter subscribers. Indie author and marketer Shayla Raquel hosts Facebook launch parties specifically on the day of release to push for last-minute sales, so she always hosts them in the evening. She says, “The launch party in no way is meant to replace any other marketing components—it’s a little bonus tool to help you end the day with a bang.” Keep the event fast paced and fun, Raquel says, and ensure posts have relevant and unique photos of you, the book, and/or the prizes; avoid stock photos. Thompson recommends that if you have no experience doing a Facebook launch party, consider hiring someone who does. “There are lots of ins and outs. They’re a lot of work.”Twitter chats. Thompson suggests authors look for and participate in a chat already running in their genre or on their topic. If there isn’t one, consider starting one. “Be forewarned, though, chats take coordination and commitment,” she says. “I’ve been doing these chats every week for about five to six years. You need to pick a weekly topic, research it, invite guests, and share summaries. I also create blog posts from the chat. This can help immensely in your Twitter growth and author branding.” (Thompson hosts #BookMarketingChat every Wednesday at 9 p.m. Eastern.)Author Q&A. As suggested earlier, try to coordinate with another author or influencer so that you’re not a lone talking head, and do these live. Thompson says you can invite readers to ask you questions about your inspirations, writing process, books, writing life, cats, etc.Author Kristina Stanley had a very successful Facebook launch party several years ago that pushed her to number one on Amazon Hot New Releases. But her later events were not as successful. “I’ve heard from other authors their first Facebook launch party goes better than the others. One thought is all your friends are super keen about your first book. … To make my first party work, I reached out to hundreds of my friends directly and asked them for help. After my third book, I stopped doing the online parties because of the effort/payoff ratio.”

Ackerman says that whatever you do for an event, it can’t look like the same old same old. “Thinking outside the box to do something fresh is what attracts attention and gets people talking and sharing.” In other words: your first successful online event may not be replicable; you have to mix things up to keep attention over a series of events.

Give people a reason to attend by offering giveaways.Just about every event—especially a launch event—includes book giveaways and other prizes. Raquel and Thompson both recommend using gift cards; the grand prize can be a signed copy of the author’s book.

Ryan says such enticements have escalated over the past couple of years. “At first, people were giving away things—notebooks and coffee mugs and tote bags,” she says. Eventually, she saw that people grew tired of those, so she and some authors switched to “buy one, get one.” For example, if a reader bought her new book and sent a proof of purchase, she sent a backlist book for free. But that also lost its allure over time. Ultimately, she says, the strongest factor of all is whether the reader really wants the book no matter what (and may end up purchasing it anyway).

Novelist Amy Impellizzeri has found that the promise of future book club appearances (whether live or FaceTime or Zoom) is a fan favorite. “When readers know their favorite authors are willing to make an appearance to their own book clubs after the online launch, they are more likely to buy and even read!” she says.

Ackerman says while she and her co-author might give away books at their events, they tailor prizes to their readership. “I think that’s important—anyone might stop by to win an Amazon gift card, but only people interested in writing would want to win my critiques, seats in a writing webinar, or writing swag.” Another option to consider is access. “People, especially readers, like to be part of an inner circle, and all authors can incorporate this into giveaways or freebies. I’ve given away lunch dates, Skype sessions, etc., but you could be accessible in lots of ways—offer membership in a Facebook reader’s group, send ecards and recipes on their birthday—whatever fits the author.”

Know how to design a sales-focused event, if that’s your goal.This is where your intended ask comes into play—your call to action. Kole says you should know what it is long before the event takes place; it determines how you set up the event and how you close it. As discussed, it’s acceptable to plan an event more focused on building a readership than making sales. But what if you want to be sales focused?

Kole says that an event focused on “come hear a reading” doesn’t prime anyone to buy; the expectation is entertainment. “The writer doesn’t ask for a sale and doesn’t get one. If the writer does ask, their audience may not be expecting it and may be turned off,” Kole says. “The writer’s icky feelings about sales come to the surface. It is a mismatch between expectation and call to action.”

Alternatively, a call to action like “come support my book launch” is a bit better because the attendee knows there’s an expectation: support. Kole says, “To me, this is the writer’s ‘nice and polite’ way of asking for a sale without asking for it because, again, they feel icky about it.”

But the ideal way to frame an event that leads to sales? Kole suggests “Be the first to get your hands on my new release.” This might attract fewer attendees but result in more sales because the language is very clear. “The expectation is that you come and buy,” Kole says. “This is a straightforward call to action with very little dancing around the issue. With the audience primed to expect a sale, the writer will have less trouble working up the courage to deliver the call to action at the event.”

To further increase sales and visibility from her online events, Raquel creates book-related prompts that attendees have to complete for a chance at winning a prize. For example, attendees might have to follow an author’s Amazon page, sign up for the author’s email newsletter, and/or recommend the book on Goodreads to three friends.

Ackerman says she rarely pressures people to buy during online events, although it can be prudent for pre-orders and Amazon ranking. When she did a more sales-oriented pre-order push, it was separate from online events. “I did three things to encourage people to get the pre-order. First, we made a big deal about a ‘surprise book’ we were writing but wouldn’t tell anyone what it was. We even had a fake cover. So, we built excitement and encouraged guessing. Second, we announced the pre-order the day we announced the book and shared the cover. So, people who were excited by the book’s topic could ride that excitement all the way to Amazon and pre-order. Third, we offered a freebie to anyone who did pre-order. We set up a Gmail account just for this and asked people to submit proof of purchase to it. When they did, the autoresponder sent them a link to a website page with the freebie. This worked well and made it easy for us to distribute the free item.”

Kole says any ask for a sale can be galvanized if you offer a promo code or discount with an expiration date. However, that can obviously lower your earnings—which takes us back to where we started this piece. “What is it that you want with this event? To get readers? To transmit books into hands? Or to make royalties?” Kole says. “It doesn’t just have to be about the dollar amount of the sale … it can be about gaining a fan.”

Keep in mindOver the long term, Ackerman suggests using events to build relationships with readers rather than just sell books. “I’ve seen Zoom dinner parties, Netflix-watching parties, online pub nights, memes for days, all kinds of stuff,” she says. “We need more of this connection and less ‘buy my book’ promotion.” Once those reader relationships get established, she says, even though they take time to build, the audience then does the promoting for the author. Whatever tactics you adopt—whether sales oriented or relationship oriented—Kole says, “Writers need to market now more than ever. There are people out there marketing their work, and they are getting ahead, while writers who succumb to overwhelm or analysis paralysis miss opportunities.”

Enjoy this article? It was first published in The Hot Sheet, my paid newsletter that’s full of trends and business guidance for authors. The first two issues are free.

January 17, 2022

The Role of Causation and Plot Structure in Literary Fiction

Photo by Ron Lach from Pexels

Photo by Ron Lach from PexelsToday’s post is by author and developmental editor Harrison Demchick (@HDemchick).

A few years ago I was visiting a local writers’ group giving a lecture on narrative structure, in particular the role of cause and effect. It’s the sort of thing any editor or creative writing teacher is going to touch on in some form or another: Causation is the driving force of narrative. Each plot beat is in some respect the effect of what precedes it and the cause of what follows.

But as I began to provide examples, a woman raised her hand and asked a very important question: What about literary fiction? What about character drama? These chains of cause and effect don’t seem nearly so prevalent in quieter, less action-oriented genres.

She had a point. So many resources you’ll find on writing plot focus on genre fiction and thrillers. My talk was no exception: I was highlighting examples from Ghostbusters, Jaws, and Spider-Man. The reason is that the mechanics of plot are far easier to see in action-oriented narratives. The hero needs to follow the clues to find the bomb before it destroys half of Manhattan. The zombies have broken through the door and our pack of plucky survivors need to move quickly to survive. In a well-constructed thriller, it’s very easy to see how each moment leads to the next, and very easy to explain it.

But that’s not what everyone wants to write. It’s not what everyone should be writing. In focusing on those examples, I’d neglected something very important: Yes, causation is fundamental in character-driven literary fiction too, but it doesn’t look the same. It’s subtler. It’s quieter. And we editors need to be precise in defining how the mechanics of plot relate to literary fiction as well.

Character is plotMost well-written thrillers are going to have a character arc. But one of the fundamental differences between most thrillers and a lot of literary fiction is that in literary fiction, quite often, the character arc is the primary narrative. Understanding that is important in understanding as well how causation drives character.

Imagine a story covering years in the life of a college professor. Fairly early in the narrative, his wife dies. Five years later, his poor habits and half-hearted lectures have the dean calling for his resignation.

Now, did his wife’s death cause him to lose his notes for last week’s lecture? Of course not. But it did change him. It left him less passionate about what he does. Five years on, maybe he’s a good deal more cynical about the world. Maybe he doesn’t see the point in trying.

The causation, then, is not in the direct plot connection between cause and effect, but rather cause and effect over time as reflected in small but meaningful shifts in character.

Circumstance and happenstanceIn most commercial fiction, happenstance is the opposite of causation, reflecting plot beats that occur not due to preceding events but by the whim of the author. But life itself introduces new and unpredictable circumstances, and it’s not wrong for literary fiction to reflect this. Take, say, a film like The Shawshank Redemption (adapted by Frank Darabont from Stephen King’s novella Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption), where much of the latter action hinges upon a new character who just happens to have spent prison time with the true culprit of the crime for which protagonist Andy Dufresne has been falsely imprisoned.

Were this a novel about how Andy gets out of prison, this could easily come across as forced or contrived. But The Shawshank Redemption is a steady character drama set over decades. Because the actual story is the changes in the character and his circumstances and how this influences subsequent decisions and action, our focus is less on the happenstance of the development and more on Andy’s response, which is absolutely the result of a subtle but consistent chain of cause and effect.

In literary fiction, then, the notion that every plot beat is the effect of what precedes it and the cause of what follows is a good deal looser. You don’t want all action to come out of the blue, but you accept that events can occur outside the protagonist’s control and ken. And if Andy hadn’t been through everything else that precedes this new character’s arrival, he wouldn’t be in a position to learn what this character knows or to respond to it the way he does, both as a matter of character and as a matter of plot.

So happenstance doesn’t supplant causation. Happenstance is used to support and develop causation.

Nonlinear storytellingNow let’s make things really complicated. How do you establish the principles of causation and narrative structure in a story in which events are revealed to the reader out of order?

Certainly literary fiction doesn’t hold exclusive rights to nonlinear storytelling, but literary fiction is likelier to play around with story structure. The farther you separate one plot beat from the next, the more challenging it is to establish causation and continuity in a way readers can understand and engage with.

But this doesn’t mean we lack structure. It means we need to consider structure on two tracks.

The first is the linear story. However that story is presented to readers, it still needs to be cohesive on its own not only in terms of causation, but also in narrative arc: inciting incident, rising action, climax, falling action, denouement.

The second is the story as it’s told. There may not be a narrative connection between two subsequent plot beats for the simple reason that they occur at entirely different times in the protagonist’s experience—but there is nevertheless a thematic connection, or something one plot beat reveals about the other. You, the author, have cause to present these specific moments in this particular order.

The arc, then, is in readers’ understanding of the story. Each beat causes the next in that it causes you, the author, to reveal it. So the action still rises toward that climax.

None of this is to say it’s simple. Balancing a nonlinear narrative can be enormously complicated. You want to be sure readers still have a sense of an advancing plot, character-based or otherwise. That’s why the integrity of the narrative at the core of the story is so important, regardless of the order in which the details are revealed. But there’s an art to nontraditional, nonlinear storytelling, and that art is set firmly in the realm of causation and structure.

So if you’re a writer of literary fiction, don’t get caught in the trap of imagining story structure is not for you just because so many of the defining examples are in different genres. The principle of causation may be less obvious, but it’s no less important—and it may just be the key to crafting a great character-driven story.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1885 followers