Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 62

April 14, 2022

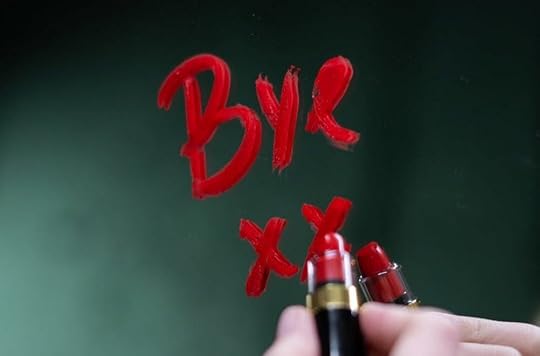

How to Gracefully Leave Your Writing Group

Today’s guest post is by editor and coach Lisa Cooper Ellison (@lisaellisonspen), who is teaching a class this month on Build Better Critique Groups.

You’ve been avoiding this for so long, but the problem is now unavoidable. Your fists clench on workshop day, your jaw tightens before every critique. You skim workshop submissions and check out of group discussions. Your anxiety has gotten so bad, you’ve “forgotten” a few submission dates or had “unavoidable scheduling conflicts” with Netflix or your dog. Some days, you feel like the world’s biggest jerk. On others, you dream up elaborate escape plans.

Deep in your marrow you know the truth: it’s time to leave your writing group.

You’ve left groups before, like the one with Douchebag Ken who mansplained all the things you didn’t get in his latest draft and Humblebrag Kate, who lorded her latest “Oh it was nothing” publication right before tearing your manuscript to shreds. You’ve largely blocked out that library-sponsored writing group that turned into a one-woman therapy session, and the one that quickly became a coffee klatch.

Ghosting those groups felt easy and justified. In retrospect, you can’t believe you stayed for so long. But this time, you love the people in your writing group. They’re your friends, your peeps. Only a monster would desert them.

A wise woman once told me some relationships are for a season, some for a reason, but only a few are for a lifetime. Most writing-group relationships fall in the season or reason category. That means leaving is a normal and healthy part of the workshop cycle. The question isn’t whether to leave, but how.

As a workshop aficionado and writing coach, I’ve discovered five reasons groups stop serving writers. The first is personality conflicts. But the other four have nothing to do with writer temperament or the stage of your work in progress.

1. Sometimes you outgrow your group.Writers progress at different rates. Sometimes one critique group member leaps ahead of the others, either because they’ve studied harder or written more. Signals you’ve outgrown your group include feeling a need to catch everyone up on a missing skill and craving more sophisticated critiques. At times, you might resent the basicness of the feedback given to you.

2. It’s possible your interests have changed.Maybe you’ve spent the past three years in a speculative fiction group, but now you’re working on a memoir. Cheers about your fantastic worldbuilding have morphed into beady-eyed glares at the three-horned, navel-gazing beast who dares to write about herself. Or maybe you’re in a memoir group and recently turned to poetry. Your memoir friends are scene-writing whizzes, but they know nothing about line breaks or meter. When a poetry group invites you to join, you feel torn between your growth and your friendships. Do you stick with the writers you know or seek the right audience for your work?

3. Sometimes priorities shift.At first, the biweekly critique group that allowed forty-page submissions made you feel so alive. A recent promotion has whittled your writing life down to a few precious hours, turning this commitment into a burden. Sometimes the internal pressure feels so intense you avoid your inbox on submission day. Then there was that time you almost wrote I really hate you on a forty-five-page first draft. Part of you believes a real writer would tough it out, but these lengthy submissions are chipping away at both your creativity and time to generate new material.

4. Even great groups can develop unhealthy habits.Perhaps you’ve become—or have always been—the group’s scheduler and taskmaster. You’re eager to hand the reigns to someone else, but the last time you tried, no one stepped up. Or maybe someone else has decided they’re the group’s unofficial honcho. Over time, they’ve subtly, and not so subtly, dictated meeting times, submission rules, and expectations about what, when, and how things are workshopped. You absolutely love the talented people in this group, but you already have a boss.

Leaving your writing group can elicit the same feelings as any other breakup, including grief about not seeing writing friends as often, anger that it must be this way, and fear that you won’t find anyone else to work with. But staying in a group that no longer serves you can not only stunt your growth, it can harm the relationships you’re so eager to preserve.

Tips for leaving your group with graceFind out why you want to leave.Make time to feel your feelings. If needed, discuss them with someone you trust. But don’t talk to other group members or people who gossip, especially if they know the writers you’re working with. Honor your desire for growth, expansion, and nourishment. Remind yourself that leaving something that doesn’t serve you is both normal and healthy.If fear of not finding another group arises, explore your options. Knowing what’s available will help you communicate from a place of power. If you discover other options don’t exist, maybe what you need is a reframe or a different conversation with this group.Once you’re ready, think about what you’re going to say. Keep it clear, concise, and kind. Set a positive tone and communicate using “I” statements. Maintain a focus on your needs and how this is good for everyone. Here’s an example to help you. “Hey guys, I’m really sad about this, but my priorities have changed, and the group isn’t working for me anymore. I love you too much to stick around when I’m not fully committed. Leaving gives you a chance to find someone who is. Because you’re so important to me, I look forward to seeing you at other times. Who’s going to next week’s reading?”Prepare for reactions and pressure to stay, especially if you’ve played a pivotal role. Affirm how sad and disappointing departures are, then repeat the key lines from your rehearsed speech.Refrain from hopping on the guilt train, and don’t buy into phrases like “we can’t go on without you,” or “I guess this means the group’s breaking up.” If the group breaks up, it probably wasn’t that strong or large enough to begin with.If you’re feeling generous, you can offer to introduce the group to someone who might be a good fit, or you can share resources that can helps them regroup. But don’t place their writing lives on your shoulders.Commemorate your time together through a closing ceremony. If the people in your group truly are friends, there’s no reason to say goodbye. Instead, have a picnic.While writing group horror stories abound, many of us have belonged to special groups that have furthered our growth. And, while we continue to love those writers, we’ve had to move on. You can too. Wanting to leave doesn’t make you a jerk. Departing with grace is an act of kindness that furthers your development and the friendships you cherish.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join Lisa and me for the online class Build Better Critique Groups.

April 12, 2022

Why So Many Blogs and Newsletters Aren’t Worth the Writer’s Effort

Note from Jane: On April 21, I’ll be teaching a class in partnership with Writer’s Digest, Blogging Strategies That Work in 2022.

Writers are told so often, and so adamantly, that they need to blog or have an email newsletter that I read countless confused and half-hearted attempts. I fell into that category myself years ago, directionless but feeling like I had to do something.

Unfortunately, doing something can be worse than nothing if it takes time away from more valuable writing and marketing activities. And more often these days, I’m telling writers to stop their blogging activity (and even sometimes their newsletter sending—until they come up with a better strategy). Here are the key reasons why.

The writing amounts to “musings”Once upon a time, around 2001, blogging was informal and akin to journaling, but those days are long gone. If you’re trying to blog or send an email newsletter with a marketing or platform building effect, random thoughts and ideas you had over breakfast isn’t likely to cut it. Social media is the best place for musings, especially if you’re in the mood for conversation or to compare notes with other people.

Instead, for blogging: Think about the potential value and longevity of the content and why people might be compelled to share it with others. Blog content, despite being free, should offer some of your most iconic and impressive material to be noticed and competitive. Here at my site, you can find such material under the blog tab—you’ll see my “greatest hits” where I give away essential information on the business of publishing. If people enjoy it, they’ll certainly find their way to my books or classes on the topic.

For email newsletters: musings might be acceptable for an intimate audience of fans. Just make sure that it matches your voice and what people come to you for. Which brings me to the next reason blogs/newsletters fail.

The writing is overly informational and without voiceBoth blogs and email newsletters excel when there is an identifiable voice behind them or a particular angle or POV offered. My POV here is to educate writers on the business. I’m frank, honest, and don’t hold back on the realities. Other blogs for writers might be more encouraging or inspiring. I err in the opposite direction.

The greatest sin you can commit, unless you are writing entries for Wikipedia, is to simply convey information. There may be a few rare occasions where that is merited, like when you need to offer instructions on how to do something. But otherwise, blogs and newsletters thrive on you creating a connection with the reader. People tend to stick around because they value and want to hear from you.

It took me years to find my voice, and it’s a journey that’s hard to speed up. But here is one secret: envision one person you know well, who you feel comfortable and confident with, that loves to hear from you or learn from you. Write for them to help find your way.

The writing doesn’t consistently connect to current or future workOne author I consulted has been blogging for years how to be your best self, then segued into racism after George Floyd’s murder. What’s her upcoming book about? A memoir on reciting Kaddish for her father for a full year. It’s a fascinating story, full of internal and external conflict, but her blogging and newsletter effort didn’t connect to it. (For an in-depth look at this case, watch my Business Clinic from last month.)

Sometimes writers cite their own boredom as a reason to write about anything and everything, while others think that any blogging will do, and the topic doesn’t matter. But it does matter because each piece of writing you take time to write and publish creates both an impression and an opportunity. When you add up those impressions over time, you become known for something. You want to be intentional in what you’re getting known for.

If you have little or no consistency in what you’re writing, it’s difficult to create impressions or opportunities around the work you want to be known for—or earn a living from.

For more guidance on writing effective blogs and email newslettersHow to Start Blogging: A Definitive Guide for WritersEmail Newsletters for Writers: Get Started GuideBlogging Versus Email Newsletter: Which Is Better for Writers?On April 21, I’ll be teaching a class in partnership with Writer’s Digest, Blogging Strategies That Work in 2022.

April 6, 2022

Why Your Amazing Writing Group Might Be Failing You

Today’s guest post is by editor and coach Lisa Cooper Ellison (@lisaellisonspen), who is teaching a class this month on Build Better Critique Groups.

I met a woman we’ll call Tina in a college creative writing class. With a 10-inch band of black jelly bracelets and burgundy-striped, black hair, Tina exuded 1990s cool. Every outfit she wore included fishnet stockings tucked into a worn pair of Doc Martens. Fans like me willingly stood in clouds of her clove cigarette smoke, perhaps hoping to inhale a few atoms of talent from this published, twenty-something author.

If “show, don’t tell” is the first advice writers receive, the second is to join a writing group. I secretly hoped Tina would slip me an invitation to the coveted critique group she called a salon. Sadly, that never happened. Still, writing friends told me all the cool kids had a writing group. So I searched for one at coffee shops, open mics, and writing classes, hoping a great group would help me not just finish my projects, but help me get them published.

Three decades and multiple writing groups later, I can attest to their value. As a writing coach, I regularly extoll their benefits to students and clients. In my experience, 99.9% of writing group members are generous souls who’ll spend hours poring over your manuscripts. The most successful groups—like the one in Portland that Chelsea Cain, Monica Drake, Cheryl Strayed, Lidia Yuknavitch, and Chuck Palahniuk belong to—can launch the careers of bestsellers. It’s the reason so many writers use words like amazing, necessary, and sacred to describe them.

But if writing groups are so helpful and so beloved, why do some writers never graduate from project-in-progress to project done? Is it a matter of following the twelve-step slogan “keep coming back; it works if you work it,” or could a healthy, highly coveted writing group fail you?

When most people think of writing groups, it’s the workshop-driven critique group they have in mind. In these groups, writers exchange pages and give each other feedback. But other groups exist, and not all dissect manuscripts. Some are designed for accountability or focus solely on helping writers generate new material. That’s important because each stage in the writing process requires something different.

Yet not every writer or writing group knows this. Even when they do, their helpful nature might compel them to honor your feedback requests. Unfortunately, ill-timed critiques can lead to resentments that make your writing group feel less like a helpful resource and more like a swamp full of Grendels whose sole purpose is tearing your project limb from limb.

The real reason writing groups sometimes fail us has nothing to do with the lovely people in them. The failure is due to a mismatch between what you need and what the group offers. Most people wouldn’t try to buy beef from a gynecologist, nor would they bend over and ask the produce manager at their favorite grocery store for a prostate exam. But sometimes that’s exactly what we ask the wrong writing groups to do. And that’s why the very best writing groups with the very best people will occasionally fail you.

When working through a first draft, your goal might be to race to the end so you can get a sense of the story you’re trying to tell. But workshopping scenes along the way will thwart your forward motion, no matter how skilled or kind your reviewers. Instead of drafting new chapters, you’ll feel compelled to revise and then resubmit the same material to your group, hoping they’ll confirm you’re on the right track. And therein lies the problem. Not only will that slow your drafting down, but you’ll waste valuable creative energy on something that might get cut. Think of it as the polishing a turd problem. Even if the writing doesn’t stink, you might need to flush it. Resubmitting potential turds can also lead you down tangents that stall your story or bloat your word count.

That doesn’t mean you can’t ask for feedback, especially if you’re struggling with doubts. Instead of asking for a literary proctology exam, tell your group you need nourishment, then request positive feedback. Ask group members to flag what’s working, what makes them curious, and what they want more of. Let that feedback fuel your creativity so you can race to the finish line and then see what really matters.

But that’s not the only way writing groups can unwittingly thwart your progress. The opposite of the critique group is the generativity group where writers respond to prompts and then share their freshly created works. If the critique group is the proctologist of the literary world, then generativity groups are more like produce stands. They can be loads of fun, and if you find the right one, you’ll feel nourished and generate a ton of new material.

That’s fabulous if you’re early in your writing career, between projects, or just starting a new one. But when you’re in the throes of heavy revision and you know where you’re going, what you need is an accountability group or occasional course-corrective feedback from one or two highly skilled writers. Get that and you’re likely to shift from project-in-progress to project done, even if your group doesn’t contain a Tina or refer to itself as a salon.

So how do you choose the best writing group for you?

Know the stage of your main project.Think about what you need based on that stage.Find a group that meets your needs. If your group’s purpose doesn’t align with your needs take a break. If you depart with grace, they’ll still love you.What writing group issues have you faced? Share them in comments. I’d love to hear from you.

If you enjoyed this post, join us for Lisa’s class on how to build better critique groups.

April 5, 2022

Why You Should Consider a University Press for Your Book

Today’s guest post is by Adam Rosen (@adammmmmrosen).

For many authors, there’s a certain template for book publishing “success”: signing with an agent, getting a decent advance, and watching the awards and social media followers roll in. Achieving this fantasy, as you no doubt know, is famously challenging—and arguably getting more so every year as Big Publishing continues to consolidate (to say nothing of recent employee turmoil).

While it’s an oversimplification to declare that the big houses stake too much on celebrity memoirs, former Trump staffer tell-alls, IPs, and other supposed sure bets, there’s more than a kernel of truth here. Platform and brand arguably matter now more than ever, especially when it comes to nonfiction.

Despair not, though. If you have a small platform and a big idea (and strong writing skills), there are other options. Enter the humble, often overlooked university press.

Within the past few years university presses have been publishing some of the most exciting, critically acclaimed trade books around. Last year, for instance, three out of the ten books longlisted for a National Book Award for Nonfiction were published by university presses. West Virginia University Press, which puts out 18 to 20 books a year and is the state of West Virginia’s only book publisher, has earned the sort of recognition and media attention you’d typically expect from a hip new indie press or house ten times its size. In 2020, Deesha Philyaw’s The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, a short story collection published by the four-person WVUP staff (now five), was named a finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction and earned a PEN/Faulkner Award, among several other prestigious accolades; last October it was announced that a TV adaptation of the book was in the works for HBO Max. The next month, Ghosts of New York by Jim Lewis, another West Virginia release, made the New York Times list of 100 Notable Books of 2021.

University presses have carved out a unique place in the trade publishing landscape, says Kristen Elias Rowley, editor in chief of Ohio State University Press, by providing an opportunity for “books that can’t find a home elsewhere.” This often translates to “projects that are either pushing boundaries in terms of form or content or voice. Projects that a larger press is going to say, ‘You know, we can’t sell 50,000 copies of this, so we’re not going to do it’ or ‘We don’t think this is mainstream enough.’” She points to two upcoming titles on OSUP’s catalog, cultural critic Negesti Kaudo’s collection of personal essays, Ripe (a Lit Hub Most Anticipated Book of 2022), and Finding Querencia: Essays from In-Between by Harrison Candelaria Fletcher, as examples. Both collections will be released through OSUP’s trade imprint, Mad Creek, this month.

Elias Rowley estimates that at least half of all university presses publish books by non-academics. While the core mandate of UPs is to advance scholarship through journals and scholarly monographs, they also have a mission to “put important literary or other general public or regional works out into the world,” she says. Of the 40 to 60 books a year OSUP publishes, roughly a dozen are trade books released through Mad Creek.

“It never seemed like the point was to be insular,” says Derek Krissoff, director of West Virginia University Press. “Part of the value proposition for [UPs] is building bridges that go out to other communities” beyond the confines of academia. In Krissoff’s view, this larger purpose gives university presses leeway to make decisions that are less commercially driven. “We’re very concerned about being thoughtful stewards of people’s resources, because we are part of the state of West Virginia. But we don’t have shareholders who need to be rewarded, and we can be a little bit freer in terms of what we choose to invest in,” says Krissoff. In light of WVU’s recent wave of success, this (winning) strategy feels more than a little ironic.

The backbone of many university presses’ trade programs is probably familiar: local and regional history, cookbooks, photography books, and other sorts of consumer-friendly titles with an obvious connection to the area or university. But many also offer a home for books that are niche, experimental, challenging in various ways, and/or just kind of weird.

I’d like to think of my own as an example of the latter. In February 2018 I put the finishing touches on my proposal: a collection of essays, from various contributors, on the cult film The Room, widely considered “the worst movie of all time” and a personal obsession of mine. My prototype was the Indiana University Press series The Year’s Work: Studies in Fan Culture and Cultural Theory, a heady series devoted to dissecting pop culture bric-a-brac. Its topics of focus ranged from the straightforward (The Worlds of John Wick) to the strange (Household Horror: Cinematic Fear and the Secret Life of Everyday Objects).

I discovered the series after coming across a 2009 entrant, The Year’s Work in Lebowski Studies, a deconstruction of, you guessed it, The Big Lebowski. The essay collection felt revelatory, offering enlightening historical and critical analysis that helped less-savvy viewers (such as myself) uncover the layers upon layers of meaning in the film, whether related to the Gulf War, the failures of the New Left, or the influence of literary critic Paul de Man on the Coen brothers (and, of course, nihilists and white Russians). It was often hilarious, but it took its subject matter seriously. For its efforts it snagged reviews in the New York Times and Washington Post.

A few of the agents I submitted my proposal to told me they liked my idea but the scope felt too narrow; one suggested I expand the focus to bad films in general. Alternatively, it was too academic. The bottom line was that they didn’t think they could sell it in its current form.

After several dozen rejections, I changed tacks and started submitting directly to university presses, who I knew were open to unsolicited queries and proposals. This time the feedback was more encouraging, but I still ran into the same problem, just from a different side: several editors said they liked my idea, but it felt too trade-y—they wouldn’t know how to sell it.

The sweet spot, it turned it out, was with an academic press with a strong trade arm who published on pop culture: Indiana University Press, i.e., the publisher who put out the very book I was meticulously, and possibly shamelessly, modeling my own book on. I ended up exactly where I began.

Initially I was a bit surprised that they’d have me. I have a BA in political science, and while as a freelance writer I’ve written about pop culture (including a piece on The Room), I don’t have a film beat. And yet, four years later, I’m the editor of and contributor to a collection of essays about a film, a book whose vast majority of contributors are academics. Another, related data point: an author whose book proposal and sample chapters I recently edited has received an encouraging amount of initial interest from her first-choice publisher, a university press in her geographic area, despite not having a bachelor’s. But she does have excellent research skills and deep professional expertise in a field related to the topic of her book, an iconic bridge.

All of which is to say that (a) university presses are not just for scholars; and (b) many are far more open-minded than you may think—as I once thought.

If you are interested in submitting to a university press, Elias Rowley and Krissoff have a few suggestions. Given the unique focus areas and track record of each press, any place you contact should be a good match for your topic. Proposing a book about birding in Maine probably isn’t a great fit for, say, University of Nevada Press. That said, “fit” can be expansive, thematic as much as geographic. “I think what our books have in common is that they are grounded in place,” says Krissoff. “And it doesn’t always mean they’re grounded in our place, although a lot of our books are about Appalachia or about Appalachian topics.”

While having a decent platform doesn’t hurt, says Krissoff, it’s not necessary; he says he doesn’t look for an author’s metrics when he’s reviewing a project. If he likes their idea, it’s much more important that the author is willing to truly commit to the writing, revising, and marketing processes. “Platform is always a bonus and can really make a difference in the outcome for a book, but it’s not going to be the thing that makes me decide not to do a project,” says Elias Rowley. “I’m not looking for a bare minimum of certain kinds of requirements. I’m looking for [if] this is a book that should be out there in the world.”

To that end, Elias Rowley says that it’s rarely too early to get on an editor’s radar. She advises authors to reach out and connect with editors early on, whether it’s through email or in-person events like the Association of Writers & Writing Programs (AWP) conference. She’ll even respond to queries that are submitted before the proposal’s been written. This way, if she likes an idea and thinks it might be a good fit, she can help develop it from the beginning. “We’re interested in forging those relationships and having it be a collaborative partnership,” she says.

The downsides? University presses typically don’t offer an advance, and if they do, it’s probably going to be pretty modest. That said, if your book sells well, you earn royalties immediately, since you don’t need to “earn out.” As Belt publisher Anne Trubek puts it, “Advances are royalties. They just come sooner.” It’s also expected that authors supply their own index, which means either using software to do a bad job or hiring someone to make one (what I did). I also gave each essay contributor an honorarium.

So when my book publishes this October, technically I’ll already be in the hole. Will I sell enough books to break even? Hard to say. I do think it could be a strong backlist contender. As I argue in my book, The Room has become The Rocky Horror Picture Show for the millennial generation. There are (or were, before Covid) monthly Saturday night screenings of it around the world, each replete with a set of established viewing rituals. The film’s notoriety continues to grow alongside that of its eccentric creator, Tommy Wiseau. But this may be wishful thinking.

On the other hand, I already consider my journey a success. Having a book title under my name with a well-respected university press has brought me a level of professional prestige, boosting my credibility as freelance book editor and opening doors for various writing projects. I also have the satisfaction of having taken the germ of an idea, turned it into a proposal, wrangled together 16 smart (and, blessedly, easy to work with) contributors, and executed the entire thing into the form of a book I will eventually hold in my hands. And, certainly last but not least, I’d like to think I’ve played a small part in furthering the world’s knowledge of the worst movie of all time, which surely counts for something.

It’s not the typical publishing success template, much less a show on HBO Max. But it just may be good enough.

March 23, 2022

The Secret Ingredient of Successful Openings

Photo by Susanne Jutzeler from Pexels

Photo by Susanne Jutzeler from PexelsToday’s post is by regular contributor Susan DeFreitas (@manzanitafire), an award-winning author, editor, and book coach. On April 14 she’s teaching the online class Maybe It’s Not Your Plot.

There’s something it took me years as an editor to figure out: many of the most common problems novelists face with their stories appear to be issues with plot but in fact are issues with character.

Openings that don’t quite work are a good example.

The conventional wisdom on the opening of a novel tells us that it must have:

A clear point of viewA compelling voiceCompelling charactersSpecific detailsTension of some typeThat’s all excellent advice. The only problem is, when writers think of “tension of some type,” they tend to think of external trouble—say, a car crash, or the protagonist being fired from her job.

This type of conflict might compel the reader’s attention for a few pages, but what really sucks us in—and what really makes agents and acquisitions editors sit up and take notice—is internal trouble, because it’s trouble of this type that signals the beginning of a character arc.

Some story gurus refer to this sort of trouble as the protagonist’s wound, or shadow. More commonly, it’s known as the protagonist’s internal issue: Some problem on the inside that, by the end of the story, they’re going to overcome—or, perhaps, tragically fail to.

As readers, we’re generally not aware that we’re even on the lookout for this element of a story. But if we’re three chapters in and the protagonist just appears to be a 100% happy, well-adjusted person—or even just a perfect person facing imperfect circumstances—where’s the story in that? (The exception to this rule is mysteries and thrillers—genres in which character arc isn’t a requirement.)

And here’s where it gets tricky, in terms of craft. Because at the beginning of the story, the protagonist herself can’t see what her internal problem is—she doesn’t even know she has one. (That’s what the story is going to force her to see.)

So how do you make sure the reader gets it, in those all-important opening pages, even if your protagonist doesn’t?

Here are three effective strategies.

1. Nagging doubts or misgivingsSay you open with a new venture—a business deal of some type, or even a marriage. In this sort of scenario, nothing so clearly signals the presence of internal trouble as mixed feelings.

Maybe the protagonist has chosen the wrong business partner, or life partner. Or maybe they’re entering into this partnership with the right person but for the wrong reasons.

Either way, misgivings on the part of the protagonist—even if they immediately tamp down, rationalize, and dismiss them—send a clear signal to the reader that something isn’t quite right with this character. Because if they have misgivings about this venture, why are they going through with it anyway?

2. Self-generated troubleEarlier, I mentioned two examples of external trouble: a car crash, or being fired from a job. Neither of those scenarios necessarily signal the presence of an internal issue for the protagonist—but they could.

The car crash that resulted from a drunk driver T-boning your protagonist? That’s external.

The car crash that resulted from them fuming over being passed over for a promotion? That’s self-generated.

Being fired from a job because their boss is a generally horrible person? That’s external.

Being fired from a job because the protagonist herself was always late? That’s self-generated.

Self-generated trouble indicates some way that the protagonist is getting in their own way. It tells us that there’s some issue on the inside this character isn’t dealing with, and now it’s come to the point where that issue is starting to have a negative impact on their life.

3. The voice of dissentMaybe your protagonist doesn’t have mixed feelings about what’s happening at the beginning. Maybe they’re headed into that business deal with stars in their eyes, and every expectation of success; maybe they’re walking up to the altar in full confidence that they’ve made the right choice.

Even so, if there’s someone else who expresses doubts about that new venture, your reader will wonder if those doubts might be valid—if there might be something the protagonist isn’t seeing, because of some internal block or blind spot.

And this is true of virtually any ground situation where the protagonist thinks everything in their life is perfectly fine: if someone else shows up to tell them that it isn’t, that they need to get their act together and change, the reader will have a clear sense that the story to come will in fact chronicle that change.

Now I’d love to hear from you.

What is your protagonist’s internal issue in your story? And what is it, in the first few chapters of your novel, that indicates the “trouble on the inside” to your reader?

Drop a reply in the comments.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on April 14 for the online class Maybe It’s Not Your Plot.

March 22, 2022

Weaving Flashbacks Seamlessly into Story

“Blue Imp 1960s playground slide” by John Maddin is marked with CC BY-ND 2.0.

“Blue Imp 1960s playground slide” by John Maddin is marked with CC BY-ND 2.0.Today’s post is by editor Tiffany Yates Martin (@FoxPrintEd). Join her on May 4 for the online class Master the Flashback.

Imagine this: After an old, familiar argument with your spouse that, as always, goes nowhere except to hurt feelings and hard silence, you’re walking in the park to cool off when a young family comes by, parents, two kids, and a dog.

The kids go tearing off with screams of glee toward a nearby playground while the dog barks joyfully and the parents settle onto a park bench, the husband’s arm around his wife as he leans in and whispers something in her ear that makes her smile.

The sight makes your heart ache, remembering when that was you and your spouse, young parents struggling financially. Every summer you felt guilty there were no big vacations to Disney World or Six Flags, but you just didn’t have the money.

All you could do was take the kids down to the public playground, but you both tried hard to make it fun: packing picnics with special treats like peanut butter and jelly sandwiches cut into animal shapes, big bags of popcorn you’d made at home, the occasional forbidden can of soda the kids treated like the Holy Grail of refreshments.

Your spouse never worried about getting dirty or looking ridiculous. She’d climb right up on the monkey bars with the kids, crawl through plastic tunnels not meant for grown adults, beckon you over with a big smile to join them and slide down the cheap metal slide—scorching the backs of your legs—in a four-person caravan with the kids sandwiched between you.

You remember one such time in particular, tumbling to the turf at the bottom of the slide in a big family pile, laughing so hard you got a stitch in your side, which made the kids laugh even harder. Sprawled half across you, your spouse leaned over and placed a soft, warm kiss on your mouth, and you felt as if nothing mattered—not the unpaid water bill, the leaky car radiator, your crappy entry-level job you hated thinking about going back to on Monday—except these three people you held in your arms.

You notice that your eyes are wet and this little family in the park has grown blurry, and you abruptly turn around and head for home, determined to apologize to your spouse.

You just had a flashback.

Authors often think of flashbacks as separate, self-contained scenes that serve to fill in essential backstory for characters—and sometimes this can be their format and function.

But this separatist approach is often at the root of why flashbacks can be so tricky for authors to incorporate without pulling the reader out of the smooth flow of the story or stalling momentum, and why they may wrestle with smoothly moving in and out of a flashback.

What is a flashback?Flashbacks are simply another form of backstory—events from your characters’ lives that happened before the events of the current story—that help flesh out your characters and their histories, dynamics, and arcs.

Flashback often works with the two other main types of backstory—context and memory—to create seamless, intrinsic flow, as in the above example. They don’t need to be treated as a standalone entity (which may be awkwardly inserted into the main story), but rather can be an intrinsic part of it.

The main components of a well-integrated flashbackLet’s look closer at the hypothetical flashback situation above to identify the main components of weaving in flashback smoothly and organically.

The character’s current situation: Before you introduce the flashback, we see your character experiencing something directly relevant to the main story—in this case, the protagonist has just had a fight with his spouse that’s one they’ve had many times, and which always ends in an impasse. Context tells us he’s upset—he’s walking in the park to cool down.A “real-time” impetus: Something in the present-day main story happens to or around the character that sparks an association or personal experience: Here it’s his seeing the happy young family that reminds him of his own.General memory: The protagonist thinks of his family when they were younger: their situation (young, financially strapped, worried about giving their kids a vacation), and similar activities to the one he’s currently seeing in the present-moment encounter with this young family.Detailed memory: The general memory leads into more specific ones that paint a clearer picture: the snacks they’d pack, the specific jungle gym equipment they’d use, the heat of the metal slide.Specific anchor memory—the flashback: The general memory and concrete details coalesce into one distinct occasion the protagonist revisits: a particular time his family all heaped up on top of each other at the bottom of the slide, his wife kissed him, and his heart was full.Transition: The protagonist returns to the present moment in some clear way that signals the shift to the reader, in this case his wet eyes that blur the sight of the family in the park that sparked his memory.Connection: Something about the flashback serves to spark a reaction or action in the protagonist in the present-day story. In this case, context suggests it reminds him of his love for his family and makes him want to set things right with his spouse.Notice some of the key characteristics of weaving in flashback in this way:

There’s no clunky, overt “announcement” or setup of the flashback in our hypothetical example, like, “He remembered as if it were yesterday coming to the park with his own family…” or the dreaded “The scene played in his mind like a movie.” Instead the character simply falls naturally into it based on his current situation and the real-time impetus that sparks one association and memory at a time, until a particular one is tapped into.The same goes for coming out of the flashback—the character is drawn out naturally (he realizes his eyes are wet because the scene he was watching blurs), rather than the reader being led out of the flashback with some overt narrative device like, “His awareness returned to the family in the park…”Flashbacks don’t have to be set apart, or even fully developed scenes: they can be snippets of experience, momentary journeys back to a past moment that integrate into the present one, as above.You don’t need to adhere to strict chronology as you would in a full scene—memory happens in fragments and flashes like this, not in chronological order. A general image or idea engenders a few salient details, which may lead the character to a specific instance.For the love of all things narratively holy, flashbacks aren’t set in italics or a different font. Well-used flashbacks don’t need visual tricks to “cue” readers to their identity; in fact, doing so is part of what pulls readers out of the story. Leading into and out of a flashback organically brings the reader naturally along on the journey with your character; context and verb tense will usually do the rest.Full-scene flashbacksFully developed flashback scenes set apart in separate sections can follow these same guidelines.

Let’s say you start with the same present-moment scene of our protagonist seething from the fight with his spouse, the family playing in the park nearby as simply part of the background as he thinks about how frustrated and angry he is that his spouse never seems to understand him or to give an inch in this old familiar clash.

Suddenly one of the kids shrieks out, “Mommy, Daddy, watch me!” And our protag glances up to see the child perched on the top of the slide, waiting until his parents are looking before pushing off.

You could dive right into a full flashback scene here—often a space break helps cue readers—and then begin a new scene from the past as if it’s unspooling before our eyes:

“Daddy, Daddy, look!”

He’d been lost in worry about his annual review on Monday—if he didn’t get that raise then how was he going to repair the car?—but his son’s shrill cry yanked his focus up, his heart pounding. The last thing he needed was a trip to the hospital—they couldn’t even pay the copay this month.

Instead he saw both kids at the top of the slide, Alex bracketing them with her long legs, her mouth spread wide in the kind of smile that had been scarce for too long, with all their money worries.

She winked at him and inclined her head. “Come on, Daddy. Let’s make a family train,” she called out…

You can write a full scene this way, then return readers to the “real-time” scene post-fight in the park, either with transition cues or by inserting another space break and rejoining the present-day scene.

But notice how this follows similar guidelines to the above: the real-time impetus—in this case the child calling for his parents’ attention—leads straight to the flashback, but one anchored by a particular, not-necessarily-chronological moment: the remembered cry of his own child in a similar situation that draws him in medias res into a scene from the past.

After the flashback you might subtly cue readers to the transition by simply establishing the setting as you would at the beginning of any other scene: “The little boy pushed off down the slide, squealing happily as his parents looked on,” or “The hard ground cutting off circulation in his feet told him he’d been standing here too long.”

Context tells readers we’re back in the “real-time” scene without needing to overtly announce it, and you can then show the connection the protagonist makes in this current moment: “His eyes were wet—Alex had always made him a better father, a better husband…a better man. He turned around and headed back home. They’d solve this the way they’d always done things best: together.”

Flashback is a powerful tool for weaving in important backstory with immediacy and impact—but as with any power tool, using it well requires knowledge and care. Incorporate the “safety guards” above and you’ll enhance readers’ experience of your story and characters smoothly and seamlessly.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on May 4 for the online class Master the Flashback.

March 17, 2022

Children’s Dialogue: They Don’t Talk Like Adults

Photo by cottonbro from Pexels

Photo by cottonbro from PexelsToday’s post is by developmental book editor Jessi Rita Hoffman (@JRHwords).

Are you struggling with the task of writing children’s dialogue? Some of the worst dialogue ever written, in both film and fiction, has been dialogue for kids. We all know children are not just miniature grownups—they don’t think like adults or talk like adults. Yet writers seem to forget that when they go to write a story and place words in the mouths of child characters that real kids never would say.

Here is one example, from a novel I’m editing for a first-time author. For the most part, this client’s dialogue writing is spot-on—it sounds like real people talking—but when he has Matthew, the two-year-old, speak, we find the kid spouting sentences like this one: “So we’re moving today?” A two-year-old, mind you!

Not only do tots of this age not possess enough life experience to understand the meaning of “moving today,” but their level of speech development is not advanced and refined enough to construct such a sentence. A more realistic way of showing a two-year-old’s confusion on moving day would be to have him crying over something small that normally would not upset him, or showing aggression toward the baby, whom on most days he loves. If words are even needed here, “Me not go” or “Matthew stay home” would be far more realistic than the adult words the author has stuck in this little boy’s mouth.

Very young children have a limited vocabulary. They speak in simple sentences or small sentence fragments. They are developmentally incapable of grasping abstract concepts, speaking in abstractions, or constructing fancy sentences, according to psychologists. They typically don’t know the “correct,” abstract word for a concept (such as “moving”) and instead use a substitute, concrete word that they do understand (such as “go”). And don’t forget that when authors write dialogue for characters of any age, accuracy doesn’t mean writing grammatically—it means writing the words the way the character would actually say them, whether that’s grammatical or not.

Let’s look at another example of unrealistic children’s dialogue from a different beginning author, who writes this about a six-year-old:

“Daddy, can you make me some lunch?” Anna called from the hammock. She lazily threw her arm over her face in hopes of shielding out some of the heat.

These words sound far too adult for a six-year-old. Moreover, a child of that age doesn’t have the conceptual capacity to intellectually plan out that putting her arm over her face might make her feel cooler. She would put her arm in front of her face instinctively, not consciously. (In hopes of shielding out some of the heat implies conscious intent).

Here is how I would rewrite that paragraph:

“Daddy, I’m hungry.” The sun shone down, and it felt hot. She covered her face with her arms.

Let’s look at one last example from the same manuscript. This time the six-year-old is telling a friend about her mother abandoning the family. She states:

“I heard Daddy talking, and he said it was just a matter of time before this happened. He said Mama couldn’t get away fast enough. She was just looking for the right time.”

But a six-year-old would never say that. Look at the complex sentence construction of the first sentence. And observe the conceptual complexities of “just a matter of time” and “looking for the right time.” An eleven-year-old might say this, not a very little girl.

To understand what kids are capable of thinking and saying at different ages, familiarize yourself with the four stages of cognitive development described by renowned child psychologist Jean Piaget. And if you’re writing a story with a child character, take time to really listen to how kids of that age talk. Make listening part of your research, and be as diligent about that as you are about researching any factual material you will include in your story.

Writing children’s dialogue does not have to be the downfall of your novel. The lines you pen will reflect reality if you let real children be your guide.

March 16, 2022

Which Social Media Platform Is the Best?

Today’s post is by book coach, author and editor Caroline Topperman (@StyleOnTheSide).

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, Pinterest … Where do you start? How do you find the time? What do you post? Do you have to be on all of them?

Before you scroll through or dismiss this entirely, I’m going to ask you to take a moment to breathe.

Most of the advice that we see online is geared toward people who are trying to build a business and already use social media regularly. But what if you don’t spend time on social media? Maybe you have an account but it’s dormant, and all you want to do is sell some books and meet some other writers. Let’s start the very beginning.

We writers come in all shapes and sizes. Some of us are working on building a portfolio and pitching articles. Others are building a following that could become a readership for a book we will be publishing. And still others want to approach influencer status and may be willing to spend more time on social media than the average writer.

Before diving in, consider your goalsDo you want to sell more books?

Hint: Take your pick, any social media platform will do.

Do you want to grow your email list?

Hint: Take your pick, any social media platform will do.

Are you promoting your blog or articles you’ve written?

Hint: Facebook and Pinterest might be your best bet.

Do you write poetry (micro work) that you want to publish directly to a platform?

Hint: Twitter and Instagram might be your best bet.

Are you trying to connect with people and share more personal information?

Hint: Instagram and Facebook might be your best bet.

Let’s break down the platforms.

InstagramBest if you want a little bit of everything; writing, photography and/or video

Full disclosure, this one is my favourite because in addition to writing, I also love photography. I like taking pictures and matching them to my text. Even though I know that a lot of people won’t take the time to read what I write, there are enough that do. To date I’ve made a substantial number of contacts this way. As Instagram competes with other sites, more features are being added. You can create short videos (aka Reels) and longer live videos. As a bonus, since it is under the same umbrella as Facebook, you can choose to automatically crosspost on Facebook. This is where a lot of people start to have heart palpitations since it sounds complicated, but it really is as easy as sliding a toggle.

TwitterBest if you want to focus on one liners and short text

If you have time, prefer to stick to text, and if you can think fast (the average lifespan of a tweet is 18 minutes), then Twitter might be the platform for you. This is where agents and editors like to hang out, so there’s a good chance that you’ll hear about the latest trends or what they are specifically looking for. I have also found that quite a few magazine editors post their wishlists on there, and some will even answer your questions. If you are trying to get a reporter’s attention, this is a great platform for that. This comes in handy if you are trying to be featured in an article.

TikTokBest if you want to create short videos that are easily set to music

Ah, the new kid on the block (which at this point isn’t that new, but still seems to make people nervous) that has already taken the world by storm. I believe that it’s here to stay but I would approach it differently than Instagram or Twitter. I would absolutely use it to build a following to promote my books, but because of its fast-paced nature, I wouldn’t use it solely to build a community. While it is possible to send someone a message, the platform isn’t built to promote that.

The key to TikTok: bite-sized videos that you can swipe through quickly. If pressed, I would say it’s a bit like a dating site. You can meet someone but you’ll move elsewhere to get to know them.

While you do not need to be on camera to create TikTok videos, it’s actually a great place to get comfortable in front of the camera. They have also made it very easy to share your videos to other platforms, once you are comfortable of course.

FacebookBest if you want to write a lot and have longer conversations with your community

The old workhorse of social media. If you aren’t already on it, then I wouldn’t recommend trying to build a following from scratch. Facebook is just too slow for that. If you already have an account, then this is the place to find existing writing groups that can offer things like marketing advice. If you self-publish and you are building a street team, this is the place to curate that team on a private page. It’s conducive to long-form text, and more drawn out, in-depth conversations.

PinterestBest for people to find you

Fun fact: Pinterest is actually considered a search engine and doesn’t have the same social aspect as the others. It is, therefore, easy to use, and worth having because the time you will put into it is minimal and doesn’t involve much strategy. It’s worth setting up an account and cross posting from sites like Instagram. If you are building a business, you could post tips for your target audience, as your potential customers might be looking for information on Pinterest.

The beauty of all these platformsYou can use them symbiotically. The most obvious is Meta, which owns Facebook and Instagram. So, when you post something to Instagram you can immediately post it to Facebook. I’m currently less active on Twitter, but I use IFTTT to post my Instagram posts to Twitter. It took about five minutes to set up and I don’t have to worry about them.

Here is the big secretThe best platform for you is the one you are going to use. Yes, at the end of the day, it’s that simple, because you are still making a connection with the outside world.

Instead of asking, “What’s the best platform”, you should be asking, “Which platform is right for me?” It comes down to your personality, what you like to do, and most importantly, what you want to achieve.

Whichever you choose, don’t be afraid. It’s very difficult to have the wrong approach. You can always change your mind and press delete. I have been on social media for over ten years and in all that time I’ve had one or two unpleasant moments that weren’t about me. My advice? Set up the platform that speaks to you, take another deep breath, and go for it!

March 15, 2022

How to Make Money Through Social Media Without Being an Influencer

Photo by Anete Lusina from Pexels

Photo by Anete Lusina from PexelsToday’s post is by Ashleigh Renard (@ashleigh_renard), author of the memoir Swing. Join her on March 17 for the online class Instagram Smarts for Writers.

Landing a book deal and getting published isn’t a guaranteed paycheck. And frankly, there isn’t a ton of money in book sales. Often, the bulk of a writer’s income will come from speaking and teaching.

Fortunately, you don’t need a publisher, literary agent or a book contract to make an impact and earn money from your writing. If you have a social media presence and a following online, you already have an audience that wants more of what you have to give.

While most writers know it’s possible to make money on social media, it seems like something an influencer would do–not a “real” writer. I’m here to change your mind about that.

Can a writer really make money off social media?The answer is yes—and it’s probably easier than you think.

You don’t need to be a tech guru, have a fancy payment system, or use a pricey platform to host your content, courses, or teaching materials.

You don’t even need to have a website.

All you really need is an Instagram account, a PayPal link, and something to offer your audience. (Spoiler: if you are a writer, you already have something to offer.)

Here are six simple ways to start making money with social media.

1. Crosspost your videosTo compete with TikTok, Facebook is encouraging creators to post videos through the Facebook Reels Bonus Play program. (Instagram is offering Reels bonuses, too, but Facebook is pushing out video content in a bigger way to make up for being very late to the video party.)

Facebook pays about $1.80 per one thousand views, which may not seem like much, but if you’ve spent any time creating videos for Instagram it’s worth crossposting them in bulk just to see what happens. My first month netted $16,000 and a client with a smaller but fabulous video library made $4,000.

Right now, it’s invite-only, but the bulk upload trick seems to trigger the invite with a high level of consistency. It’s as if the platform says, “Whoa, someone who’s never posted videos here just uploaded twenty. They must be regular creators on TikTok. If we throw money at them, maybe we’ll become their favorite platform!”

Don’t tell Facebook, but you don’t need to create anything on TikTok. I recommend using Instagram to make video content, because you can easily create a great video with their superior editing tools, save it, and crosspost it to your personal Facebook profile and Author Page (and even TikTok, if you wish).

Side note about Instagram: There are a ton of social media platforms out there, but Instagram is my one-stop shop for a multitude of reasons, starting with its great editing tools. By creating all of your content on Instagram, you’re creating a catalog of your work that you can refer back to and repurpose down the road. Plus, it’s easier than ever to share your content directly from Instagram to other platforms, which takes the stress out of keeping your social media up-to-date, aligned, and impactful.

2. Recommend a product or service that you loveIs Scrivener your go-to writing app? Does Substack take the hassle out of your email marketing?

Reach out to the companies behind your favorite things, or shout out a teacher or another writer who inspires you, and let them know why you love them. Then ask if they have an affiliate program you can sign up for.

You might be surprised at how many people say yes.

Alternatively: An easy way to start making some extra cash today is to set up your Amazon and Bookshop affiliate accounts. Once you’ve activated your accounts, use those links anytime you recommend a book online, or even when you buy books yourself, and enjoy a little kickback from your reading list.

3. Provide a done-for-you serviceWhat comes easily to you? What do you love doing that other people prefer to avoid?

Could you help other writers by editing their pitches and recommending ideal publications for their work? I’d love to pay someone to make my essay pitch super sharp and tell me the five best places to submit.

Are you a Canva whiz, killer with Quickbooks, or highly effective with Evernote? There are a lot of people who would happily pay you just to set up templates for them.

Think about how you can leverage your skills to help your people, and then spread the word. Pick one thing and run with it.

4. Offer coaching or teach a courseMaybe you’re an efficiency pro who could offer one-on-one coaching sessions around time management, or a virtual how-to webinar to maximize productivity for writers working from home. Or you’re an author with a number of interviews and publications under your belt who could teach best interviewing practices for new writers.

Think about what you do really well and how you might be able to solve a problem for your people by sharing your practices and know-how.

5. Create a membership or subscription communityI subscribed to Jane’s publishing industry newsletter, The Hot Sheet, because I want to stay up-to-date on industry news—and I will happily pay so that I don’t have to worry that I’m missing something crucial if I am not constantly keeping on top of it myself.

What research are you already doing that might benefit your audience? What tools, support, or resources can you offer your community?

6. Sell a productYour product could be as simple as creating a printable PDF that applies to your area of expertise and will solve a problem for your audience. If you work with other writers, you might offer “10 Tips to Stop Procrastinating and Start Writing,” or “5 Simple Exercises to Break Through Writer’s Block,” or “How to Set Up Your Author Website in One Hour or Less.”

Your PDF doesn’t have to be all-encompassing. It just needs to be effective. (And if you charge $4.99 per download, you could wind up making more money from your PDF than you would from book royalties.)

Make it easy for your audience, and yourselfAfter you get clear on what you can offer, writing and using a clear Call to Action (CTA) is essential to monetizing your social media. The easier you make it for your audience to find your offers and opt-in, the easier it is for you to get paid.

Whether you’re sharing a phenomenal freebie, promoting your book, or sharing your latest offering, “Get XYZ at link in bio” is the most actively, and successfully, used CTA on Instagram. Use it whenever you post related to your teaching or product. Your audience needs more reminders than you would think in order to see and engage with your offers.

You have to start somewhereA lot of times, we hesitate over our offers, telling ourselves an idea isn’t “good enough” or that we “just aren’t ready yet.” The problem is that then we don’t start at all.

Instead of stalling, give yourself permission to start small. Set aside some time to batch load your IG Reels onto your Facebook.

Send a few emails to your favorite authors or the creators of your favorite products and find out if they have an affiliate program.

Consider the questions your audience asks most often and brainstorm ways to turn the answers into a printable PDF or an ebook.

Yes, you’re a writer—and a damn good one at that. Still, the wisdom and knowledge you have to share extend far beyond what can be offered to you in any book deal, grant, or residency. You have something to offer the world today and every day, and it’s perfectly okay for your bank account to reflect that.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on March 17 for the online class Instagram Smarts for Writers.

March 9, 2022

A Thousand New Email Sign Ups in a Week? It’s Possible.

Photo by Liza Summer from Pexels

Photo by Liza Summer from PexelsToday’s post is by Ashleigh Renard (@ashleigh_renard), author of the memoir Swing. Join her on March 17 for the online class Instagram Smarts for Writers.

Speak to any group of writers about platform-building and within five minutes you’ll hear someone mention that they “should” be building their email list or how nice it would be to have a paid newsletter.

We’ve all received the memo that our email lists are one of the only pieces of owned media we have, rather than the audience we borrow from Twitter or Facebook. Emails are not at the mercy of the algorithm and do not take hours to master, like Reels. Then why are so many writers thinking about building their email list, but not really doing it?

List building and newsletter strategy are two different things.Many writers stall out while developing a complex newsletter strategy, or can’t conceive of what they would share in a regular email, so they don’t build their list at all.

But you don’t need to start strategizing newsletter content or setting a delivery schedule. All that can wait. Instead, you can (and should) start today by building your list.

I have grown my audience over the last few years, but mostly ignored my email list. That is, until the Instagram and Facebook blackout last October. I had interviews to promote and a book to sell, but I was left without any connection to my audience. For each of us, having a way to contact our audience directly is essential. I never wanted to worry about being cut off again, no matter what changes Meta (Facebook) introduces down the road.

That day I created my first freebie: a one-page document (PDF) in Canva. Since then I’ve gained 22,000 new signups and launched two paid newsletters. I’ve helped clients’ lists grow exponentially as well.

What can you offer that people need?Your audience journey goes something like this: someone reads an incredible essay you wrote, watches one of the videos that you shared, hears you on a podcast, or catches your Instagram Live.

They’ve made first contact.

After that initial impression that your writing or speaking made on them, they’re going to want more.

What did the reader love about the piece or the interview or the video?If your writing impacted them, what do they want from you?And how can you give that to them?As writers, we often feel that we could offer meaningful support, encouragement, inspiration, or education by sharing our personal perspective and experiences. We create connections by making people feel seen, and offering insight, camaraderie, and value to our audience. That value is the key to turning views and likes into email subscribers.

So give it away. Focus on the problem you can help people solve and then share your solution as a free (and simple) download that people can receive when joining your mailing list.

Your freebie is the answer to this essential question: what value are you putting into the world?

The right freebie should fit in naturally with what you are already writing and speaking about and what you know your audience wants. Your freebie can even act as a reverse mission statement. Looking at it should give people a one-page snapshot of who you are and the writing you do.

To visualize it, think of your freebie this way: if you were profiled in the New York Times, what photo would they choose for the main feature image? What would they highlight in the caption? If you were featured in Women’s Health or Cosmopolitan or Rolling Stone, what headline would make the cover of the magazine?

“Five easy ways to solve your big problem …” is a popular marketing approach that draws interest, creates curiosity, and tells the reader in two lines what problem that article is going to solve for them. Your freebie should do the same thing for your potential audience by homing in on the value that you provide.

Signing up for your email list will be an impulsive decision, just like grabbing that magazine at the checkout counter. Lead with a great title and don’t worry about oversimplifying. The one page freebie does not have to encompass all you know and have to offer. Consider it the gateway doc, the first invitation into your world.

Once you’ve developed your freebie and a simple call to action, set up your delivery system so that when folks sign up, your freebie is automatically sent straight to their inbox. Contact created. Value delivered. (Flodesk is my favorite email service for easily segmenting new audience members and putting together quick workflows.)

How to publicize your freebie and ensure signupsStart by linking to your freebie in your bio across social media platforms. If your freebie does not make sense in your bio, ask yourself if the rest of your bio makes sense. Where do you need to create clarity? Do you need to shift or pivot the way you’re positioning yourself as a writer?

Like a steel thread through your work, your freebie will help you make decisions on how you show up and what content you share. When you are about to post on Facebook or Instagram, ask yourself, does my call to action fit in with this post?

If it makes sense, fantastic, hit “publish.” If the post isn’t aligned with your CTA, ask yourself if the content you’re looking at is what you want to be known for in your writing.

You don’t have to link your freebie in every post, but asking yourself if each post fits your call to action before you share anything is a fabulous exercise for keeping yourself intentional.

That doesn’t mean that you’re only allowed to talk about one thing, but it will ensure that you are showing up consistently and being mindful of how you frame yourself and the work you put out into the world.

Offering a freebie will not only help attract people to you and your work, it will also guide your content creation and your newsletter strategy. Nothing inspired me to write a regular newsletter quite like 1,000 new people each week signing up to say they’d like to read my newsletter.

It’s not a question of the chicken or the egg. To make any progress one needs to come first, and let it be list building.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on March 17 for the online class Instagram Smarts for Writers.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1885 followers