Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 63

March 8, 2022

The Value of Percolation

Today’s post is by author Jyotsna Sreenivasan (@Jyotsna_Sree).

I love learning how the brain works during the writing process. I’ve mostly been interested in how to “turn on” the brain’s right, creative hemisphere through exercises like free writing. A book I recently read gave me insight into a different aspect of the writing process: the value of not writing—of setting aside an unfinished draft.

How We Learn by Benedict Carey (Random House, 2014) explains scientific research on how the brain learns. While much of the book concerns rote memorization, I was drawn to chapter 7, which details how the brain approaches long-term projects (such as writing a novel).

Most writers have heard this advice: set aside your draft to revise later. And most of us have experienced new insights when coming back to a manuscript. Why is it helpful to set aside a draft? Why do we sometimes get insights about our writing when we are not working on it? Carey calls this process “percolation.”

The first element of percolation: interruptionWhen a project is interrupted at an important or difficult moment, that keeps the project at the top of our brain’s to-do list. Most of us have limited time to write, and some of us believe we should not start a story or novel unless we’ll have time to finish. But interruption is actually good for a long project and means that you can start a book whenever you want.

When my children were small, I used to wake up at 5am and spend one hour working on my fiction before I went to work. That’s all the time I had: one hour per day. I had no idea if my writing would come together in anything publishable, but I treasured that quiet hour when no one was demanding my attention, and I could focus on something I craved. Because I interrupted my writing every morning, I was still thinking about it (consciously and I’m sure subconsciously as well) during the day, and when I sat down the next morning, I often had some new ideas. Although it took years, I was able to write my novel And Laughter Fell from the Sky in one hour per day (as well as some occasional longer stretches when my husband would take the kids away for a weekend).

As my children grew older, and once I started working as a teacher, I had longer stretches of time to write during school breaks. When in the midst of a project, I would often lose track of time. I’d work throughout the day, and as much as I enjoyed the process, I wondered: was I really being productive, or was I spinning my wheels re-reading, tinkering, or heading down the wrong path?

A few years ago, I found out about a practice called the “Pomodoro Technique,” which involves setting a timer for 25 minutes and working steadily during that time. Each “pomodoro” session is separated by a short break of up to 5 minutes. I set a timer on my phone and purposely put the phone in a different room, so I am forced to stand up from my computer and walk at least a short distance to turn off the pomodoro. If I’m in the flow of writing, sometimes I head right back to my computer after setting another pomodoro. At other times, I take a few minutes to wash some dishes or fold a few clothes. Even a short interruption can help, due to something Carey refers to as “selective forgetting.” A short break helps us forget about any blind paths or misleading avenues we were heading down. Even a tiny interruption helps my brain re-set. Sometimes, as I’m washing the dishes, I’ll get an idea about a line of dialogue to try, or an insight into a character.

The second element of percolation: the tuned, scavenging mindWhen you have a project in mind, you are subconsciously attuned to any clues or information in your environment that might be relevant. “Having a goal foremost in mind…tunes our perceptions to fulfilling it,” says Carey.

It is important, therefore, when setting aside unfinished work, to keep your mind open to solutions. In the past, when I did not have a solution to a problem in my writing, I felt uncomfortable. I would try to argue the problem out of existence, try to convince myself that everything was fine. The problem was still there, though. Inevitably, critiques would point out the flaw I was trying to ignore. But because my mind had been closed—because I had been telling myself there was no problem—I had not come up with any solutions yet. Finally, I realized it was better to accept that nagging, uncomfortable feeling that said “something’s wrong here,” even when I didn’t know how to solve the problem. Being open to solutions often allowed solutions to suggest themselves later on.

Recently, I was pulling together a short story from segments of an unpublished novel that I’d worked on years ago and then abandoned. This short story has three sections, and I didn’t like the way the first section ended. The last line seemed too final for the first section of a story. I had the urge to argue away the problem, but fortunately I allowed myself to feel uncomfortable with having a problem and not knowing how to fix it. Some days later, I hit upon a possible solution: make the last sentence of the section into a line of dialogue, and have the other character react to it. I tried it, and liked the way it worked.

The third element of percolation: conscious reflectionOnce we come up with a possible solution, we must try it and reflect on whether it works. Maybe that idea that seemed so brilliant in the shower is a dud when applied to the page. Or maybe it’s just right.

The process of percolation, over years, helped me write the novella that ends my new collection These Americans. The novella originally started out life as a novel that I was actively working on several years ago. It involved an elderly woman immigrant doctor from India and her semi-estranged daughter. It also involved an Indian-American woman whom the doctor hired to help her ghostwrite her life story, as well as the ghostwriter’s overbearing husband and three children. The novel was not bad (it ended up being a finalist for the PEN/Bellwether prize), but despite numerous attempts at revision, neither I nor my agent was satisfied with it. I set it aside.

Years later, while grappling with some unexpected life experiences, I mined them for fictional possibilities. Maybe I could use these experiences in that novel about the immigrant woman doctor. And, inspired by my fascination with novellas, I decided to tighten the whole thing into a novella. I collapsed the daughter and the ghostwriter into one character. And I added a story line inspired by my own recent experiences. The result was a novella I renamed “Hawk,” and many readers have told me it is their favorite part of my book. I believe one reason the novella works is because I was forced to allow time for percolation.

Understanding the process and value of percolation can help you get started on a project that may still be vague in your mind. For example, one day recently I made some notes about my mother and her messages to me (when I was a child) about my appearance, as well as what she had told me about how my grandmother had tried to control my mother’s looks when she was growing up. I had no idea what I’d do with these notes. I thought maybe I’d write an essay. Then, two weeks later, I woke up with the urge to write a story about a mother’s gift of a mysterious, deceptive mirror to her daughter. When I originally made the notes, I had no idea they would end up as a magical realism flash fiction piece.

Inspired by my new insights into the process of percolation, I even used it to write this essay. When I finished reading Benedict Carey’s book, I was excited by what I’d learned about percolation. But busy with work and other writing projects, I knew I didn’t have time to craft a full essay. Instead, I took 20 minutes to jot some jumbled notes. I set aside those notes on the top of a low bookshelf, where I saw them every day. I knew I would come back to them when I had time. And several weeks later, that time materialized when the school where I teach was closed for two days because of snow. Since I already had those notes, I could jump right in and draft this essay without wasting time wondering what to work on.

Percolation allows the brain’s subconscious to work while we’re busy with something else. Now that I know the value of percolation, I understand that any writing is useful, even if unfinished or abandoned. The time we spend writing is never a waste. Our brain is still working on those ideas, and we never know when that story, essay, poem, or novel will spring to life again.

March 3, 2022

When You Change Alongside Your Book: Q&A with Mansi Shah

The Taste of Ginger author Mansi Shah discusses the challenges she faced in her quest for publication, the evolution of her focus in the process of writing about the immigrant experience, the lasting impact of books and movies, selling books to Hollywood, and more.

Mansi Shah (@mansiwrites) is a writer who lives in Los Angeles. She was born in Toronto, Canada, was raised in the midwestern United States, and studied at universities in America, Australia, and England. When she’s not writing, she’s traveling and exploring different cultures near and far, experimenting on a new culinary creation, or working on her tennis game. For more information, visit her website or follow her on Instagram at @mansishahwrites.

KRISTEN TSETSI: What books did you most like to read as a child, and what attracted you to them?

MANSI SHAH: I was a voracious reader as a kid, and so I read anything I could get my hands on from our local library! The ones I most remember reading were Judy Blume books, the Nancy Drew mysteries, Sweet Valley Twins, and Sweet Valley High. I also recall reading books about WWII, like Number the Stars by Lois Lowry, and I am still drawn like a magnet to books about the Holocaust, but there were not too many middle-grade books that dealt with that subject. Even from my earliest memories, the books that stuck with me most were those that explored injustice, perseverance, and humanity.

I think what attracted me to books in general was that I could transport myself to other places and times through those pages. My childhood had financial ups and downs, and we moved several times, but I could escape into stories and take a mental break from whatever was going on at the time.

You wrote your first book at nine years old, turning in a chapter a week to your teacher (after getting permission) rather than the assigned short story once a week. Do you remember what you wrote your book about, or what you think you probably would have written about?

I do! Maybe better than I should! It was called Valley of the Dolls and was a mystery about two kids who got lost while hiking and stumbled upon an eerie abandoned small town. In one of the houses, they found dollhouses that represented a miniature version of the town. In one of them, they saw the dolls positioned to show a murder, and the two kids then went about trying to find out what happened in the town and why it was now abandoned.

My Grade 4 teacher, Mrs. Strube, had my handwritten book bound together at the end of the school year, and I wish I still had it with me so I could remind myself how the mystery was solved, because I’ve forgotten the ending! One day, I’m going to have to go digging through the boxes my parents have stored in their garage to see if I can find that original book.

You knew you wanted to “write a real book, some day,” but you went on with life and school, studying psychology in college and then veering into law. Did you do much creative writing between your fourth-grade book and The Taste of Ginger? If not, did you have other outlets throughout your years of professional work and studying to satisfy creative urges?

I dabbled in creative writing through my schooling years, doing some poetry and short stories, but not really doing much else. During my early lawyer years, I had started a couple novels but never got more than a few chapters into them before life and work took over.

In hindsight, I think the projects I’d started were never completed because I was writing what I thought I should write (legal mystery/thrillers) rather than what I was passionately interested in writing, which was The Taste of Ginger. I did, however, always maintain a creative outlet to balance my left and right brain, and I think the need for that balance comes from my mom. I grew up watching her engage in many creative endeavors, from cooking to ceramics to floral arranging to other artwork, so part of me was always inclined toward that.

My university years were spent diving into cooking and baking, and learning how to express myself through food (something I’m still obsessed with today!), because when I moved out of my parents’ home, I knew the only way I’d get to eat the Gujarati food I grew up with was to learn to make it myself. I also tried different painting classes, until I found the one that resonated most with me. Surprisingly, it was Chinese brush painting! For many years I painted in that medium and would probably still be doing it today if my teacher hadn’t retired many years ago!

I also found small projects along the way like scrapbooking, interior design for my home, photography, cross-stitch, and various other arts and crafts to keep myself engaged in artistic expression.

You said in a Good Life Project interview that years into your legal career you began to feel like writing was a better vehicle for impacting change and reaching people, that you could say more things “with fewer rules.” The driving force behind The Taste of Ginger, you said, was your mission to offer something to young people from immigrant families looking for books that represented them and their experience.

How easy or how difficult was it for you to balance the tasks of illustrating the challenge of half-belonging in two very different worlds and ensuring that the story, the characters, didn’t get lost in or diluted by the message?

This is such an interesting question! I think it was relatively easy for me to write immigrant characters who went through life while questioning their identity and belonging because that is my lived reality. My experiences and choices were not the same as my protagonist Preeti’s, but I believe the underlying question of belonging resonates for most people, regardless of background.

For me, the highest priority was to craft a relatable and engaging story that kept readers turning the pages. Part of that meant that the story and characters are intertwined with the underlying themes of acceptance, identity, and trying to find out what home really means to them, and I do think it means something different for each character in the book. My goal in writing The Taste of Ginger was to keep the story and characters at the forefront while giving insight into the introspective journey that so many immigrants experience, whether they go through Preeti’s specific challenges or not.

I have kept so much of my assimilation and acculturation journey to myself, and many people in my life would not have appreciated the many layers of thoughts I had as an outsider in even the simplest of situations, and I wanted to illuminate that process. The narrative around how my main character Preeti responds when someone cuts in front of her in line at the grocery store is a good example, because that seemingly innocuous transaction is more fraught and thought-provoking for her based on her past encounters than it might be for someone else who never experienced what she did as a teenager. My hope is that these small vignettes throughout the book help the reader understand her decisions and conflicts on a deeper level.

In your early days of writing The Taste of Ginger, you said in the Good Life Project interview, you thought you would need a primarily white audience for your book to sell, so you initially did a lot of “whitewashing” in the early draft, avoiding or watering down Indian elements that might trigger white readers. After you realized the story needed to contain those elements to honestly reflect the cultural experience you’re familiar with (and to resonate with the audience that drove you to write the story, in the first place), you brought them back in.

What kinds of things were you hesitant to include, at first, and what did it feel like as you were writing to discard that caution and just write the story you wanted to write?

Having been told early in my writing journey that I had to write for a white audience to earn a living as a writer made me hyper-conscious of that fact in my early drafts. I still wanted to raise the difficult issues that immigrants face but was cognizant that I shouldn’t go “too far” into any areas that might offend a white reader. For example, I didn’t address the notion of “color-blindness” that was a common and well-intentioned view that I had often heard while growing up. I also didn’t delve as deeply into what it feels like to be a non-white immigrant in a predominantly white law firm, and I wasn’t as direct about referring to America’s racial hierarchy as a caste system. I felt like I hinted at those issues but didn’t give them the justice on the page that they deserved.

And even beyond the ideas and how they were expressed, I kept my white audience in mind and italicized and provided embedded definitions for any Gujarati words, which was the norm at the time for non-English words. It seemed like it was an uphill battle to get a book centering on an Indian immigrant experience published in the first place, and I couldn’t also ask industry decision-makers to google the words.

But with each revision, I became bolder in what I wrote because simultaneously the world was changing, and I felt like society was evolving in a way that I could be more direct with each draft. And I was changing alongside it. I started writing The Taste of Ginger at the age of 29 and was 40 when I got my book deal. Highly formative years for anyone! During those years, I became less afraid of what would happen if I wrote something that challenged the way people think about immigration and assimilation.

Even with the personal confidence I’d been building, it wasn’t until the global racial reckoning in 2020 that I felt the freedom to fully write what felt authentic and true to my main character’s experience. Over the years, I began to feel an obligation to provide authentic representation to Indian immigrants, and to show our thoughts and experiences in an honest way that is relatable to us. White readers have countless books they can turn to and catch glimpses of themselves, so it didn’t make sense for me to focus on that audience when representation for readers from my own culture was so lacking. I kept asking myself who I would have grown into if I’d had more Gujarati representation in the stories I had read—seen familiar names, foods from my dining table, cultural customs that normalized those I never saw outside of our family home—and I wanted to provide that to the generation behind me. And given society’s awakening to the experiences of people of color in Western societies, I knew that people of all backgrounds were on a quest for understanding and appreciating the differences between us in a way that I had yet to see in my lifetime.

With that goal in mind, I delved deeper into the thoughts of my Gujarati-American protagonist and really painted a view of the conflicts she faced within her family, among her friends and colleagues, and in her romantic relationships. I removed the italics from the Gujarati words and the explanations that had never felt right to me. The Taste of Ginger is a first-person narrative of a Gujarati-American woman, and she knows what those words mean, so she would not pause to explain them. It is clear from context whether she is referring to an item of clothing or food or term of endearment, and I realized that is enough. The words are not foreign to her, so in the same way that an author writing from the perspective of a white American protagonist would not be expected to explain pizza, skirts, or sweetie, I gave my main character that same deference. (And all the words in my book can be googled for anyone who wants further understanding of any of them; I confirmed that myself before publication!)

Making these changes felt like I was finally writing the story I set out to write when I was 29, and it was liberating! I had crafted a story that I was truly proud of and that was authentic to everything I sought to achieve as a writer, even though I was terrified about how it would be received. I did not even let my family read it until just before its release date! Yet, even with my liberation high, I turned in my final draft to my editor and waited with bated breath worried that she would come back and tell me I’d gone too far, that some of the ideas in the book would be too alienating, that we needed to explain the “foreign” words. Fortunately, she loved everything about the changes, and I knew I had the right editor and ally in my corner!

The Taste of Ginger took ten years to sell. Part of the difficulty you faced when trying to get an agent was that some agents you queried would say they’d “just signed an Indian author” or would have recently had “a book like this” on their list. Considering how many books by white Americans are published that are similar to each other in their broader subject matter (soldier stories, murder stories, love stories, detective stories, coming-of-age stories, etc.), how did you receive that feedback, internally, and how did you stay motivated to keep looking for an agent?

That type of rejection was one of the hardest parts of the journey for me, because it was completely out of my control. I wasn’t being told that there was a problem with my writing, or voice, or story. If I had been told any of those things, I could have worked harder, spent more time revising, or come up with another story. But that there wasn’t room on the shelves for what I had written was both demoralizing and motivating.

I had all the thoughts you mentioned, including that no one would ever say that to a white author because there’s room for multiple stories from that point of view. I’d not yet read a single book that reflected my Gujarati immigrant experience, and very few existed featuring characters from other parts of India, but the message from the publishing industry seemed to be that the 1.4 billion people of Indian descent with their varying cuisines, languages, dress, and customs were interchangeable, and the handful of books that existed were enough to satisfy that readership.

My most memorable rejection was in 2011, when an agency meant to send an internal email but instead replied to me (that dreaded act that we all fear), so I saw their true unfiltered thoughts: “Solid voice. Great title. Though I’m worried because you said the India wave has passed…”

I spent a long time thinking about my culture as a passing “wave.” What kept me motivated from that response and others like it was that none questioned my writing abilities. I knew my culture’s stories were worth telling, so it was the fuel to keep going until I found the right agent and editor who wanted to join me in my efforts to disrupt the publishing industry!

Your editor passed on the novel, at first, but said she’d consider it again after a revision. Your agent advised against doing the revise-and-resubmit. Why?

At the time when my current editor initially passed on the book, I was deep into writing my second book. And I had been revising The Taste of Ginger for nearly a decade at that point, so I felt like it was time to move on from it. My agent suggested that I should only revise and resubmit if I felt I wanted to do that for myself, but that in her experience, when publishers weren’t willing to go through the revision process with the author—especially in my case in which the revisions were not that substantial—then it was unlikely that they would pick it up later.

Basically, she nicely told me, it was a longshot. Based on the feedback I’d been getting on The Taste of Ginger, I was more confident in my ability to sell my second novel, so I thought I would be best served focusing my energy there.

After about a year and a half, the same editor contacted you to ask if the manuscript was still available, and you had some mixed feelings about her interest. Can you talk about that a little bit and about how you’re feeling now?

The timing of my offer was strange, because we had stopped shopping The Taste of Ginger over a year earlier. We were amid the 2020 global pandemic, and a racial reckoning following the murder of George Floyd and too many others and rampant acts of Asian hate. Voices that had often been disregarded were calling out for change more than I could remember at any other point in my life, and people seemed to be listening.

The Taste of Ginger, a story about an authentic Indian immigrant experience and the search for identity and belonging when someone straddles two cultures without ever fully being accepted in either, is the type of story that it seemed like people were ready to hear. When my agent called me and told me I had an offer, I was stunned. When she told me who it was from, I was even more shocked, because I had not made any of the revisions that had been discussed 18 months ago—had not even moved a comma—but now that same manuscript was worth making an offer without those revisions.

I wrestled with what had happened in the world to lead to this point, and it was a complicated mix of emotions. I could not divorce the publishing industry welcoming content like my novel from the many lives that had been tragically cut short to lead to this pivotal moment in my life. My lifelong dream came true against the backdrop of all this pain, so that duality resulted in a lot of introspection. I questioned if I was getting an offer because it was the current “wave” to sign authors of color—I didn’t want to be seen as a token or quota metric. I wondered whether I’d have to change elements that a white audience might find uncomfortable or controversial. While my manuscript hadn’t changed, it felt like everything around it had.

I talked to my agent for two hours and asked her whether she thought it was the right career move for me to sell both books without having even tried to shop my second novel, yet. Both her gut and mine said that it was. It was a foot in the door, and then I’d let my writing and characters do the talking.

It was a gamble, but I’m thrilled with how things turned out! I love my editor, and she has steadfastly championed the authenticity of my stories, always encouraging me to delve deeper into the minds and hearts of my Indian characters. When I was worried that she wouldn’t like new elements because they handled controversial topics too directly, she would respond that those additions were among her favorites. I’ve gotten so much more than simply having a foot in the door, and I am forever grateful for the opportunity to bring these stories to readers.

As an entertainment attorney, you could have written a screenplay instead of a novel and had little trouble getting someone in the film industry to consider it for production (or at least read it). But telling the story was, you said, a creative journey that had to be authentically you, and books have always been authentically you—you read them in the library as a child, had them available when your family didn’t have access to movie tickets, and could “retreat into these characters, these pages.” Part of your goal was giving that same access to young people who can use it now.

You also noted in the Good Life Project interview that you think Hollywood “has shaped public perception around the world in so many ways. No matter where you go, American television and film is present.” Now that you’ve accomplished the novel (and have another on the way), would you consider writing for screen in order to expand your reach and influence?

It is so quintessentially me to make life more difficult than it needs to be! Yes, I am fortunate that I do have access to key executives and talent representatives in Hollywood and could get people to at least consider my work and give it a fair look, with no guarantees beyond that, of course!

I know Hollywood much better than I know publishing, so I could certainly envision expanding my writing for screen. The main goal I hope to accomplish with my writing is to amplify representation and tell authentic stories. In a perfect world, I’d love to do both books and screen and would be immensely grateful if life presents those opportunities to me.

In a November 1945 issue of The Atlantic, Raymond Chandler wrote of working as a writer in the film industry, “On the billboards, in the newspaper advertisements, [the writer’s] name will be smaller than that of the most insignificant bit-player who achieves what is known as billing.” This when it’s the writers who generate the stories, provide the words the actors speak, create from scratch the characters actors portray.

But the inequity isn’t just about visual recognition. Carrie Pilby author Caren Lissner writes in her 2017 Atlantic account of the adaptation of her novel into a movie for Netflix that authors who sell the screen rights to their novels “often get a sum equal to about 2.5 percent of the [production] budget,” and according to the video and television production company Beverly Boy Productions, there’s often a cap, so even if the budget increases, the writer won’t benefit from that higher budget. Writes #teambeverlyboy on their blog post, “That means, even if the [original $10 million] film budget increases, to say $100M? You’re still only going to get $225,000 for the rights, which is still a rather substantial amount of money.”

It’s hard not to be disappointed by the fact that many writers do still say, “Oh, yes, thank you,” to being one of the lower paid people on the team because not only are they being graced with the attention of a production company, which means exposure, but film rights probably do earn a writer more money than they would normally otherwise make. That doesn’t mean the payment, when compared with the rest of the budget allowances and/or the adaptation’s potential earnings, is anywhere near what should be considered adequate compensation for the writer’s inarguably critical contribution.

This all reads as naïve, surely—it’s just how things are in Hollywood—but based on what you’ve seen in your time working in Hollywood, is there potential for authors selling film rights to their work to unify, even in an unofficial way, and demand no-less-than compensation in their contract? For example, “Will not accept a budget cap,” or, “Budget cap, fine, but I also want 2.5 percent of the film’s/series’ earnings for the life of that film/series”? If writers were less willing to accept being treated as content creators for producers rather than as important contributors and artists in their own right, could there be a shift in the perception of their value to the industry?

This is such an important question! Like with publishing or any other established industry, shifting “business as usual” in Hollywood will be a heavy lift, but the optimist/activist in me thinks that we still need to try. As an initial matter, the odds of a book that is optioned actually being produced and distributed is exceedingly rare, so those initial option payments reflect that and are typically very modest. When the options are exercised and the project is being produced, that’s when the author gets the largest payment they are likely to get—typically a percentage of the production budget. Those amounts seem high to authors who are used to getting a very small royalty on each unit sold of their book, but it is often the case that the author gets less compensation relative to the other talent working on the adaptation.

Having had first-hand experience in both industries now, I can see the competing interests at play. Screen adaptations are expensive—generally much more than publishing a book—and decisions are driven by costs and budgets. There is a certain amount that the talent working on the adaptation will be paid from the budget, and that pot of money gets divvied between them, including the option/rights fees to the author. Given that system, it would involve talent and the studios working together to rethink how they allocate production budgets, because if the author is getting paid more, then it likely means someone else is getting paid less than what they have been accustomed to receiving. If it’s not other talent reallocating some of their compensation, then it would be sacrificing something else in the budget, like a special effect or location or wardrobe, and that is also difficult once someone has a creative vision. At the end of the day, it’s all tied to the numbers, and I think it’s going to take a lot of work to change how production budgets are allocated.

This is not to say authors shouldn’t fight for a new normal and seek to change how they are compensated for their source material, but the reality is that those fights gain more traction when done by the most prominent authors who can afford to withhold their rights and not see an adaptation made unless the standard changes. Very few writers are financially able to decline that hefty—even if comparatively less—rights payment that comes with an option being exercised. But if the prominent authors were to seek change, it is more likely that such changes would eventually trickle down and become the standard for everyone. For the time being, however, I think the best thing authors can do is attach themselves to the adaptations because there is more compensation for those who are actively working on the screen versions.

With so many streaming services forming their own production companies, there are increasingly more avenues for writers to have their work adapted. Is there something you think every writer entering into film rights negotiations for the first time should know, watch for, or ask for before signing a contract?

We are living in an era where content is everywhere and available on demand, and that has been great for expanding representation in so many areas. The best advice I have regarding a screen rights deal is to make sure to have the right talent rep in place.

All the studios have preferred agencies and/or talent firms with whom they deal, and those top representatives often have pre-negotiated deals with studios such that even if you are just starting out as an author and selling screen rights for the first time, you could benefit from the talent rep’s already established relationship with the studios. In Hollywood, my view is that those relationships matter just as much as the written source material when it comes to getting the right deal.

As versed as you are in the film entertainment industry, the publishing industry was new to you when you sold your novel to Amazon imprint Lake Union Publishing. In the decade you spent waiting to be published, you must have imagined what it would be like. How did reality match up?

Hearing the news from my agent that we had an offer on The Taste of Ginger and my second book was completely shocking! At that point we had shelved it, so I had no reason to think The Taste of Ginger would live anywhere outside of my laptop!

Having my childhood dream come true can only be described as surreal. The early reviews for the book have gone well beyond anything I ever expected. I’ve received heartfelt messages from immigrants who have felt seen and understood for the first time in a book, and from readers of all backgrounds saying that it gave them a better understanding of the immigrant experience and they will move through their lives with more empathy and compassion as a result. There is no higher praise I could ask for!

I have challenged myself to be open to the debut author process and not put demanding expectations on myself (no easy feat for this overachiever!), knowing that once the book was published, there was very little I could do to make it a success and its performance would rest on the opinions of my readers. Before the novel was published, I would have said getting 1,000 reviews was more than I could have expected, but the book blazed through that goal in a matter of weeks!

As time passes, I admittedly am moving my goalposts from what they had been pre-publication (Joanne Molinaro, The Korean Vegan, has a great post about moving goalposts that has stuck with me). It’s part of my personality to achieve one thing and then look to the next, but with this journey, I’m pausing to cherish the successes as they occur, before, of course, resetting that goalpost!

I’d say the biggest adjustment for me when it came to my publishing deal was that I wasn’t negotiating it myself. I’ve built an entire legal career in which I negotiate on behalf of others, and it was a bizarre situation to hand over the reins to someone else for the deal that I had dreamt of for so long! That said, as the adage goes, “A lawyer who represents herself has a fool for a client,” so I knew I needed to get out of my own way! I am still learning the publishing business and am beyond grateful to have my knowledgeable, experienced agent advocating on my behalf, while accommodating my higher-than-average need to know every detail of the negotiating process.

Author Paulette Kennedy asked what advice you would give up-and-coming writers. You said, in part, “There is so much happening all at once and so much of it is good, but it’s easy to get overwhelmed with everything there is to do. … Give yourself some grace if you can’t fit in everything that you wanted to do on the marketing and promotion side.”

What was the “everything there is to do” in your case, and how did you manage the overwhelming moments?

Getting the initial deal is just the first step, and I knew that if I wanted to keep getting deals the book needs to meet the expectations of readers and my publisher. By publishing with Lake Union, it is a unique model compared to traditional Big Five publishers, so my experience was different from that of the few other authors I knew. In my case, with the exception of a pre-release blog/social media tour in December, Lake Union focused on marketing rather than publicity. This meant their efforts were spent on things like getting my book selected for the First Reads Program (which is huge exposure for a debut author!), targeted ads via search engines, and using Amazon’s algorithm to make people aware of my book in the first place, given that discoverability is one of the biggest hurdles to a book being successful.

On the other side, Lake Union doesn’t assign every author a publicist (and I was not chosen to have one), so all the post-release PR opportunities were the result of my own hustle and the help of my friends. For example, I am fortunate to be friends with Jennifer Pastiloff, bestselling author of On Being Human, who has an extensive network and loyal following. She organized Good Life Project for me (and I still can’t believe it, because I’ve been a fan of Jonathan Fields for years before I had a book deal!) and put me in touch with Shelves Bookstore, a wonderful indie bookstore owned by Abby Glen, for my virtual book launch. Having been through her own book launch with a Big Five publisher, Jen was able to give me great advice and guidance on top of the great connections she helped me make. I honestly cannot imagine how I would have survived without her, because she became my de facto publicist!

My other podcast interviews, including Best of Women’s Fiction and The Jabot, were from me reaching out to those places on my own. I was given print and digital ARCs, but I was responsible for finding book bloggers willing to read and review and sending the materials out myself—there were many trips to the post office, but I am now friendly with the staff at my local branch!

My biggest hurdle and the area in which I had to give myself the most grace was social media. I’m not a natural at it and self-promotion is hard for me, so I knew I needed to focus on promoting other authors in addition to myself. I don’t think people realize how much time and effort goes into these posts or reels that we then spend a few seconds viewing.

Given that I still work full-time as an entertainment lawyer, balancing social media on top of my day-job and the actual writing was too much. I had talked to a friend in PR, who had told me I should have one post per day and 3–5 stories each day, and within days, I knew I couldn’t maintain that schedule. So, now, I do my best with the time I have, and I try not to get down on myself if I can’t stay consistent. And the reality is that I don’t have enough reach on social media to move the needle on sales in the way that Lake Union does, so that takes much of the pressure off, and I can use social media for the purpose I enjoy most—engaging with readers and authors!

Going from being a lawyer to being an author promoting her work online must be interesting. Are there platforms you’re more/less comfortable with than others?

Social media is the hardest part of the author job for me! I created social media accounts after I got a book deal because I knew it was necessary, but before that, I was the person who had gone years without engaging with it. My lawyer job is all about confidentiality and privacy, and I am an introvert who has always preferred quality one-on-one time with people than interacting on a mass scale, so I was not primed for this.

While I’m not the most regular content creator, and I’m not the person who is likely to have anything go viral, I’ve found it’s been a wonderful way to connect with readers and authors. Some of the heartfelt messages I’ve gotten from readers have been so moving and have helped motivate me to explore new themes and ideas for future works. And there are so many wonderful bookstagram and booktok accounts that are helping with discoverability of books like mine, and I’m grateful to them both as a reader and a writer. I have more books in my TBR list than I can likely consume in my lifetime, but it’s good to know that I’m spoiled for choice! And I’m grateful for the connections I’ve made with other writers through social media. I’ve genuinely made true friendships and found a community that is so generous and supportive, and I hope we will actually meet in person one day!

Amazon / Bookshop

Amazon / BookshopWhen it comes to platforms, I was given the advice early on to pick one and focus on that, so my platform of choice is Instagram, and you can find me @mansishahwrites. I tend to carry over my content to Facebook and Twitter as well, because they’ve made that easy for even a neophyte social media user like me to do! I’ve used Facebook, so I have a general understanding of how that works, but Twitter still mystifies me if I’m ever on the platform, and I probably need to watch a tutorial to learn some basics.

I knew I wanted my socials to authentically represent me, so they focus on the things I love most: highlighting books by underrepresented authors, exploring countries for my next novel, cooking the Indian food I grew up with, and finding the right European wine to pair with my culinary adventures…the same themes that are often present in my books!

March 2, 2022

What Your Writing Is Training You For

Photo by Atul Vinayak on Unsplash

Photo by Atul Vinayak on UnsplashToday’s post is by author, editor and coach Jessica Conoley (@jaconoley).

I had a coaching call this week with a client who was living the creative dream. A highly anticipated book launch with great reviews, support from the publisher, deals in the background that she couldn’t talk about yet. It was the moment many writers dream of.

And she was miserable.

To make it worse she knew she should be happy, but the non-creative part of her livelihood was sucking every ounce of life out of her—depriving her of the energetic emotion to feel anything at all, let alone celebrate this milestone. She needed to make some hard decisions about her life. And those life-altering decisions felt even harder to make because she didn’t know what was going to happen next.

Because we had worked together from her first manuscript through agent signing, and all the good beyond, and because she knew I had left behind a corporate life and am still standing she asked me for advice. Our conversation went something like this:

Jessica: As a writer you know that moment in a story. The moment where you’re writing in the dark. Where you’ve made it this far, but don’t see where the story is going, or what happens next. You’re worried you won’t figure it out, but you’re already twenty-thousand words in and you have to figure it out, but it feels impossible, like you’re a complete garbage human, and why even keep going…

But…you’ve been at this point before, and you know you figured it out last time, so you’re probably going to figure it out this time. And regardless of the horrifying feelings of suck and imposter syndrome, you have faith you’re going to get through it, and a book is going to come out of it. Have you ever felt like that when you write?

Writer: Yes. That’s pretty much it exactly.

Jessica: Living your life as a working creative is living in that moment of you don’t know what happens next. Again, and again, and again.

Your writing has been training you for this moment. Your writing has been training you, so you can start living your real life.

Living your life as a creative means having faith that you are going to figure it out and make it work when you’re sitting in the dark and can’t see what’s coming next.

You’re rarely going to know what’s coming next. At first that’s scary, just like when you’re writing. But also, just like in writing, there’s a point when scary turns into excitement, because what happens next might be cooler than anything you ever could have imagined.

Writer: What you’re saying makes sense, but if I knew when or how this next part played out, I feel like I could take that next big step.

Jessica: Right, but that’s the thing. Creative living isn’t the corporate world where there’s this gigantic machine that can honestly control the how and when things happen. This is a whole different world. And to survive and learn to be happy in this creative world, you focus on the WHAT you’re doing and WHY you’re doing it, and you leave the how and when up to something bigger than you.

I know that’s hard to swallow, because it’s a huge act of faith in yourself and your creativity. This is why we turn to the people we trust who have been there before. The people you know won’t lie to you.

I’ll tell you what my mentor, Deborah Shouse, told me when I was standing in your exact spot. “It always works out.” I couldn’t believe it. “Always?” I asked. “Always,” she said. When I made the leap, and my rational mind would tell me all the reasons I would fail, I would remind myself that Deborah wouldn’t lie to me. So, I was going to let her confidence propel me, until I’d established my own.

And she was right. It always works out.

I then went on to tell my client half-a-dozen examples of how it had always worked out. I also told her that rarely did things work out when or how I thought they were supposed to, and sometimes what felt like complete failure in the moment, ended up teaching me something really important or lead to a long-term success I couldn’t foresee.

At the end of our call, I was confident my client would get where she needed to be, and that her work was going to impact countless readers. But like the rest of us, I knew she would confront mindset issues as she detoxed from the conditioning of non-creative life and embraced the challenges of a creative career.

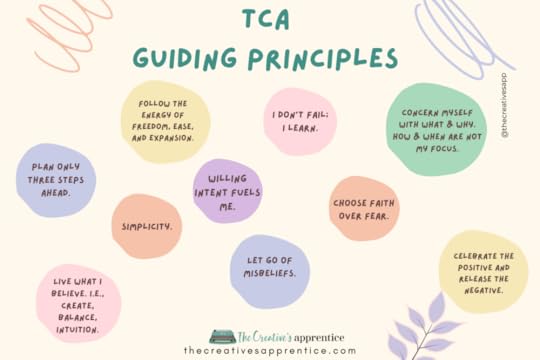

After we hung up, I sent her an image that included the guiding principles I established for myself, and by extension The Creative’s Apprentice.

Concern myself with WHAT & WHY. How & When are not my focus.Follow the energy of freedom, ease, and expansion.Live what I believe. i.e., create, balance, intuition.Celebrate the positive and release the negative.Plan only three steps ahead.Willing intent fuels me.Choose faith over fear.Let go of misbeliefs.I don’t fail; I learn.Simplicity.

Concern myself with WHAT & WHY. How & When are not my focus.Follow the energy of freedom, ease, and expansion.Live what I believe. i.e., create, balance, intuition.Celebrate the positive and release the negative.Plan only three steps ahead.Willing intent fuels me.Choose faith over fear.Let go of misbeliefs.I don’t fail; I learn.Simplicity.It was time for her to establish her own rules for how to Live Life as A Creative—something she could reference in those moments where she was sitting in the dark, unsure of what happens next.

Have you thought about what principles guide you through your creative career? If not, think of a moment you’ve been stuck, or felt like your work was irrevocably broken. What helped you through that moment? Make a list of qualities, lessons, or feelings that helped move you forward. Build off of that, and over time refine it. Post it in a visible spot, and next time you are faced with a hard decision, be it in your writing or your life, use it as a reminder that you have been in the dark before, and you always find your way out.

March 1, 2022

13 Ways to Freaking Freak Out Your Horror Readers

Photo by Pedro Figueras from Pexels

Photo by Pedro Figueras from PexelsToday’s post is by author and self-publishing mentor Shayla Raquel (@shaylaleeraquel).

People love to be scared. So if you’re writing in the horror genre, your ultimate yet obvious goal is to scare the pants off your readers. You want them to bite their nails down to nubs. Seeing an Amazon review that says “Kept me up all night! So creepy!” would make your horror-writing heart so happy.

But what are some methods for achieving that kind of feedback? How do you frighten a reader so badly that they text their mom at midnight saying, “OMG this book freaked me out so bad! You have to read it”?

Here are 13 ways to do precisely that.

1. Place something scary in a beautiful setting.We’re used to scary things happening in dark alleyways or creepy abandoned warehouses or Michael Myers-esque mental hospitals, but what if things could be even scarier when you put them in breathtaking places?

For example, if I wrote a scene in Japan with the cherry blossoms, you’d imagine the most gorgeous pink hues. It would feel like a wonderland. A place you’d want to get married or have the world’s best photoshoot.

Now take that setting—a place where romance buds—and slit a character’s throat. That is horrifying, but it works. When you use a lovely background for an odious purpose, it stings more. It’s unnatural, it’s unexpected. As a reader, I expect an evil clown to round the corner of a dark alley. I do not expect to see blood spurting from a neck amid cherry blossoms.

2. Push the limits of your antagonist’s sanity.In Misery, Annie Wilkes has a scrapbook with newspaper clippings from her past life as the Dragon Lady. That’s already nerve-racking, but it’s more messed up when we see that she drew in the scrapbook. What’s more horrifying to you—that Annie has a scrapbook of her murders, or that she glams it up with little handwritten sayings, like a sorority girl with Polaroids might?

Let’s say you’re writing a Mommie Dearest type of villain. Do you have a “No more wire hangers!” moment? Is there a scene wherein your villain pushes the limits of her sanity and does something so obscene that it becomes a pinnacle moment for your character(s)?

Speaking of sanity…

3. Study the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).I might get hater comments for this, but here we go: I don’t know how you can appropriately write about terrifying villains without having some basic understanding of psychology and nature versus nurture. Your antagonist is not just a serial killer or a cannibal or a human trafficker for no reason whatsoever. There was something (or somethings) that led your antagonist toward monsterdom.

Even if it’s a case of nature (the villain was born this way), that’s still a reason, an answer. Invest in the DSM-5 and study up on psychotic disorders.

For example, there is nothing inherently “wrong” with being a psychopath; many psychopaths lead perfectly fine lives with jobs and families. The twist is when, perhaps, a psychopath is raised by an extremely abusive parent, thus potentially setting the foundation for a violent antagonist in your crime thriller.

4. Show your villain right at the beginning or right at the end.Do you know when the great white shark fully appears in the movie Jaws?

One hour, 21 minutes in. You get glimpses, but the entire shark? Nope, not until the 1-hour, 21-minute mark (in a 2-hour film). It’s this tension that makes the movie superior. The viewers know there is a man-eating shark, but the anticipation in seeing it in all its grudge-holding glory? That keeps people on the edge of their seats, even decades later.

On the other hand, kicking off a story immediately with an in-your-face villain is a tried-and-true method. In Thirteen by Steve Cavanagh, you know by the third line in the prologue that Joshua Kane is a cold-blooded killer.

With this method, you eliminate the mystery of the villain (i.e., “Who could it be?”) and replace it with dread (i.e., “I know who the monster is, so whatever he’s about to do is going to be heart-stopping!”).

5. Cross the line. Big time.This could also be titled “cut the vein,” which I’ve talked about often. In 2019, author Sanderia Faye taught a class for Dallas-Fort Worth Writers Conference and explained that writers cannot skirt around the edge; they must cut the vein. They must bleed onto the page. Think of Sophie’s Choice or Beloved.

In horror, you’ll most likely have some blood and guts and definitely death. It’s expected. But sometimes cutting the vein means not going for death. Could a scene become more gruesome if torture was involved? Could a story become more memorable not because of an ounce of blood, but because of the deep psychological trauma your antagonist inflicted on your protagonist?

In Cujo, Stephen King achieves this by killing Tad, a 4-year-old boy, not from the bite of the rabid dog, but from dehydration and heatstroke.

Can you think of a time in your writing when you cut the vein? Have you ever pushed the boundaries in your story? You should.

6. Research what others won’t dare to.When I wrote Savage Indulgence, a short story about a cannibal named Joyce, I knew for a fact I’d be falling into an abyss that was not for everyone. Horror forces a writer to learn about topics that many humans probably shouldn’t know a thing about. If I was going to write about eating human flesh, I was going to have to read about that exact thing to get it right. Once I read what I read, I could never undo it. So there is a major caveat to this method.

That said, if you’re willing to, um, go where no man has gone before, you can terrify your reader on a totally different level. For example, I read literature published by actual cannibals so that my scenes were on point every time. It was really hard for me to digest (okay, awful pun, so sorry). It took a toll on me, to be honest. But the cold hard truth? It made my horror story better because I researched so deeply.

7. Reveal that any human being can become a monster.Breaking Bad, though not horror, did an exceptional job at this task. Can you take a beloved character or an average joe or a do-gooder and turn them into a savage? Can you make the lovable unlovable?

Horror so often shows us things about humanity we don’t want to see. We want to believe that everyone is capable of good, but maybe, just maybe, some people start out good and evolve into something sinister.

Try taking a character who is loved by all—she volunteers at her local nonprofit, bakes goodies for her neighbors, dotes on her husband—and turn her into a walking nightmare.

8. Push beyond “There is no way this could possibly get any worse.”In Misery (yes, again, I know), Paul Sheldon being held against his will is bad. Paul’s longtime stalker being his nurse? Oh, that’s bad too. But you know when things go beyond that? When Annie hobbles him. As a horror writer, you have to be willing to go beyond bad. You have to go to a dark, messed-up place. A place that’s just plain wrong.

Make your reader think, “There is no possible way this could get any worse.” Right when you have them in that moment, wreck them with something disgusting or god-awful or traumatizing. You want Hannibal Lecter moments? Then rub salt in a wound.

9. Interrupt a happy or nostalgic moment with horror.In Wanderers by Chuck Wendig, Charlie tells a cute story about his kids eating spaghetti. In this scene, it’s pure nostalgia and you find yourself smiling as you reminisce with him. But his sweet story is interrupted by a gruesome, shocking moment. Like, stop-reading-and-back-up shocking. (I shan’t spoil it.)

I read this scene three times. To me, this is true horror. This is true tension. To be able to take a nostalgic moment for Charlie as he retells it, then interrupt it with something so jaw-dropping—that’s a skill set I hope to have as a writer.

So if you know you’re going to write a shocking scene, set it up nicely with a sweet moment.

10. Learn from real-life monsters.True crime is a big part of my life, so I binge plenty of it. I use it as a method for learning. If I’m going to write about monsters, I need to study real-life killers from our past and present. Men are often the monsters in the real world and in fiction, so I like to make my villains female. In my research, I’ve found that women such as Marjorie Diehl-Armstrong and Michelle Carter and Aileen Wuornos are fantastic case studies. When I learn about them, I can implement my findings into my own characters.

Think about your antagonist. Is there anyone from real life who resembles him or her? If so, watch documentaries on that real-life monster; listen to podcasts, read books, study conspiracy theories. Whatever you can get your hands on. The more you learn about the real things that go bump in the night, the more your readers will crave your stories. (And sleep medication.)

11. Play with the “wrongness” of something.In Night Shift by Stephen King, “The Mangler” (short story) has a non-human villain: a laundry folder at a laundromat. You wouldn’t think it’d be scary, but it freaked me out. It was just…wrong. It shouldn’t be a thing, but it was and it worked.

What is unnatural in your story that you could work with? In the short story “Hive,” featured in Kitchen Sink by Spencer Hamilton, we meet a young boy who turns his entire house into an infestation of ants and spiders and creepy-crawlies. Two agents make their way inside the house, and there is no possible way you can read this story without feeling like bugs are on your skin. That’s “wrongness” in all the right ways.

12. Polarize your readers.This method deserves a pros and cons list before you do it, but if implemented correctly, you’ll leave readers thinking about your story for years to come.

In The Cabin at the End of the World by Paul Tremblay, the reader is left to decide who was right: Eric or Andrew. Even Paul himself has disclosed that he doesn’t know the answer. Sometimes, we don’t get all the answers. That leaves us polarized. Some readers don’t like endings like this, but I find them to be more accurate than most. Because that’s what life does in its most horrifying moments: it leaves us with more questions than answers.

If you want to leave your readers scared and talking, polarize them.

13. Embellish your own deepest fear.I’m petrified of spiders, porcelain dolls, childbirth, and clusters of holes (trypophobia). If I were to write about these topics—things I’m genuinely afraid of—that fear would resonate with my readers, even if they aren’t necessarily afraid of those things. My fear would become their fear.

Make a list of the things that strike fear in you, then use that list as a writing prompt. Take what you’re afraid of and embellish it. If you’re afraid of confined spaces, then put your character in a claustrophobic setting on steroids. Being stuck in an elevator that won’t move isn’t enough; add a dead body to up the stakes. If you’re afraid of heights, then placing your protagonist on a roller coaster may be interesting, but it’s not enough. Having the roller coaster stop still isn’t enough. Instead, have the roller coaster stop while the protagonist is upside down. Try to think of what would make you lose your mind.

That’s it, horror writers. I hope these methods help you scare the crap out of your readers!

February 28, 2022

What If Your Memoir Is Middle Grade?

Photo by cottonbro from Pexels

Photo by cottonbro from PexelsToday’s post is by Allison K Williams (@GuerillaMemoir). Join us on Wednesday, March 9 for the online class Writing Memoir for Young Adult and Middle Grade.

Many of the adult memoir manuscripts that cross my editorial desk share one issue: They start too early. Usually, about 50 pages too early. The writer spends time establishing the quirky small town/neighborhood they were born in, the family experiences that shaped them, the early realizations that they—or their family—weren’t like everyone else, carefully setting up the clues for later revelations about divorce, addiction, illness or triumph.

The reader needs some of that information, yes, but not all of it. A concrete, well-timed detail can give a lot to readers without spelling it out. For example: I could fill you in on my family history of alcoholism, how it manifested in my grandparents’ daily “cocktail hour,” my own shying away from drinking because I don’t like the taste and I’m scared, what it was like living with a father who was drunk or at least buzzed most of the time—or I could tell you, I have a hard time telling when someone else is drunk. I think they just seem “jolly.” For an adult memoir about an adult experience in my life, and in context, that’s probably enough background.

But what if your childhood is the whole point?

While some adult memoirs successfully cover childhood in depth (notably Mary Karr’s The Liar’s Club and Jeannette Walls’ The Glass Castle), there’s a whole new category out there, selling like hotcakes: memoir for young readers. Graphic-novel autofiction like Raina Telgemeier’s Guts and Jerry Craft’s New Kid and Class Act. Memoir in verse like Jacqueline Woodson’s Brown Girl Dreaming and Thanhha Lai’s Inside Out & Back Again, both winners of the National Book Award and Newberry Honors, and Laurie Halse Anderson’s Shout, the memoir version of her bestselling novel Speak.

These memoirs fall into Young Adult and Middle Grade, but they don’t shy away from hard subjects. Anxiety. Racism. Immigration. Poverty. Sexual assault. They embrace beautiful writing while dealing with issues their readers experience, in vocabulary their readers can understand and apply to their own lives. Not everything ends happily ever after.

In an adult memoir, childhood is usually a chance for reflection, as in Jenny Lawson’s Let’s Pretend This Never Happened:

By age seven I realized that there was something wrong with me, and that most children didn’t hyperventilate and throw up when asked to leave the house. My mother called me “quirky.” My teachers whispered “neurotic.” But deep down I knew there was a better word for what I was. Doomed.

Lawson takes us into the feelings of the child she was, but she’s processing her experiences through the reactions of the adults around her at that time, and her own knowledge now of her adult life. We know she survived—she wrote a memoir about it.

Thannha Lai’s young self in Inside Out & Back Again also feels doomed:

Every Friday

in Miss Xinh’s class

we talk about

current news.

But when we keep talking about

how close the Communists

have gotten to Saigon,

how much prices have gone up

since American soldiers left,

how many distant bombs

were heard the previous night,

Miss Xinh finally says no more.

From now on

Fridays

will be for

happy news.

No one has anything

to say.

This young narrator shows looming tragedy and fear through her eyes at that age, instead of looking back. There’s an urgency and immediacy to the child’s story. Memoirs from a younger POV bring extra tension, because we all know adulthood can turn out very differently from what we expected. The choices a child makes are often more fraught, with farther-reaching implications, and we don’t know if the narrator will be OK, or what “OK” will mean in fifteen years.

What might make your story right for YA or Middle Grade? Think about your most vivid and intriguing experiences: What age were you? How much of your current manuscript focuses on childhood, and more specifically, learning and realizing new things about yourself and the way the world works at that age? How much is adult reflection on adult problems? Maybe the memoir you’re working on now is right for adults—but there’s a big chunk of childhood you’d still like to share.

Think also about your desired audience. Who is going to benefit more from hearing your story: adults experiencing the same situation, or kids who might be able to choose another path, or gain more resources from knowing they aren’t alone?

Practicing writing through your younger eyes can bring a freshness and urgency to your prose, even when your finished work will be targeted to adult readers. Recreating childhood experiences on the page can bring up buried memories, sounds, smells, tastes, interactions that have faded for adult-you, and make your settings and characters more vivid and realistic for the reader.

What makes a memoir for young adults or middle-grade readers isn’t shying away from tough topics, or using childish language, but approaching situations and events with your childhood eyes. Sharing what the narrator sees and feels, with all the intense emotional engagement of a child, while letting the reader compare those things to what they, too, are seeing and feeling right now.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, please join Allison on Wednesday, March 9 for the online class Writing Memoir for Young Adult and Middle Grade.

February 24, 2022

If You Can’t Stand the Sight of Your Own Blood, Don’t Step Into the Ring

Photo by Musa Ortaç from Pexels

Photo by Musa Ortaç from PexelsToday’s post is by author Catherine Baab-Muguira (@CatBaabMuguira).

About 10 years ago, I was moaning to my longtime mentor about the mean comments posted on one of my articles. “What is wrong with people?” I asked him. He’s written for Vogue, the New York Times, and published a string of well-regarded books, and while I have done none of those things, I was sure he could use a gripe session, too.

Instead he shrugged and said, “If you can’t stand the sight of your own blood, don’t step into the ring.”

OUCH. I had not been looking for tough love. I wanted sympathy. Why couldn’t he understand that I’m a delicate artiste who needs everyone else to cater to my exquisite sensitivities? What was so hard to grasp about my needing endless external validation and not criticism, much less typo-riddled harangues from strangers?

Okay, so I was the confused one. My mentor had it right, I just needed a little time to come around to his way of thinking. Once I did, though, my worldview rearranged itself in a better order—I had fewer expectations and could accept a wider range of outcomes. It is difficult yet important to toughen up a little, and to develop enough confidence in your work that you’re not sunk every time someone dislikes it and says so, at length.

This isn’t to romanticize hard knocks, it’s to romanticize resilience. How else are you going to have a writing career that lasts more than a couple of weeks? How else can you maintain a crucial openness to feedback, so that when the helpful kind comes, you’re able to hear it? How else can you keep going amidst the often distressing realities of this profession? What are you gonna do—quit?

Fortunately, I only need to ask myself such tough questions every single day. Still, the foremost thing my friend’s advice reminds me of is not the knockdown but the joy: how great it is to be in the ring. How great is it? Oh my God, it is so great. I take it for granted that you also worked for years to get here. You may’ve wanted to be in the ring your entire thinking life. And like Drake said: Started from the bottom, now we here. It is a privilege. I for one am so glad. My guess is you are, too. This dream does not come for free and it never will, but you know, if you can’t stand the sight of your own blood, don’t step into the ring.

These days, just typing that sentence makes me grin at my desk, here in the predawn dark where I have foregone sleep so I can do this instead. Once, it was hard to hear. Now it guides me.

It’s what I told myself in 2018 when I had a different piece come out and a beloved internet personality spent hours making fun of me on Twitter, with a fair few of her 100,000 followers joining in. Seeing that thread was like a polar plunge of the soul, my sensation a refreshing combination of embarrassment and hurt. Soon it grew so long that I stopped quoting it to my therapist and just forwarded her the link. But you know, if you can’t stand the sight of your own blood, don’t step into the ring.

It’s what I told myself when, even more recently, an excerpt of my first book ran on Lit Hub in what was, for me, a dream very literally come true, and some people in the comments section were moved to call it “too cute by half and twice as contrived,” while others posted longer diatribes:

I signed up for this site just to comment on how terrible this article is. I mean, we’re discussing a man like Edgar Allen Poe here [sic], and the best advice you can construe from his life is “double your effort and move/run away”? Well, someone didn’t double their effort in writing this it seems.

I’d like to imagine that you didn’t ever think this was good, but that it’s your job to constantly write mediocre to shitty clickbait articles, and that you are really a talented writer just looking for your big break, and that you hate doing this. I want to believe.

The funny thing is, the excerpt was itself about rejection, so this person dunking on me was, so to speak, scoring double points in the video game. While I can’t say if they really did try to imagine my deeper fears, they landed close enough. It’s okay, though. I don’t agree with their assessment, I have more confidence in my work than that, and anyway I have grown used to the sight of my own blood. It does not shock me. It is essentially fine, close enough to fine for me to keep going.

So—submission rebuffed? Query dismissed? Book turned down by some acquiring editor? Nasty review posted for all to see? If you can’t stand the sight of your own blood, don’t step into the ring. Meanwhile it’s so wonderful to be in the ring. I can’t see leaving it voluntarily, because I want so much to be here. Don’t you? If you’re reading this, you’re probably a writer, too. So you know.

February 23, 2022

How Important Is Genre When Pitching and Promoting Your Book?

Today’s guest post is a Q&A by Sangeeta Mehta (@sangeeta_editor), a former acquiring editor of children’s books at Little, Brown and Simon & Schuster, who runs her own editorial services company.

This past fall, I came across an essay published by Literary Hub in defense of genre labels. Author Lincoln Michel argued that, while genre labels are fraught, they are “highly useful” and we “actually need them more than ever.”

This point of view intrigued me because it’s rare, especially coming from a fiction writer. Many novelists, especially those who consider themselves literary novelists, are loath to define their genre. Why reduce their work to a label or box? Doesn’t confining oneself in this way impede the very process of creating art? Some writers wouldn’t mind dissolving genre altogether.

As it turns out, publishing executives also have reservations about labels. Earlier this month in Poets & Writers, Dutton editor-in-chief John Parsley said that one of his biggest pet peeves is “the pressure to classify a book as either literary or commercial.” This also surprised me since, as Parsley notes, it’s generally those within the trade who encourage such classifications. It also made me wonder if “literary” and “commercial” could be considered genres.

To get a better understanding of what genre is and how much trade book publishing relies on this concept, I spoke with literary agents T.S. Ferguson of Azantian Literary Agency and Laura Zats of Headwater Literary Management, both of whom have spent several years working in the book industry in various capacities. As with all my Q&As, neither knew the other’s identity until after they submitted their answers to my questions below. Interestingly, their answers overlapped on several levels.

Let’s start with a broad question: What is your definition of “genre,” and how would you differentiate it from other literary terms that are often used in conjunction with it, such as “category,” “form,” and “audience”?

T.S. Ferguson: For me, genre is about setting an expectation with your reader. For example, when you tell someone a book is a “fantasy” they are going to expect some magic or otherworldliness, if a book is labeled a “romance” there’s an expectation that there will be a Happily Ever After at the end. It helps the reader wrap their heads around what kind of story they’ll be getting if they choose to read this book. Category does something similar, but in nonfiction, for instance, your book could be a wellness book, a memoir, a travel guide, etc.—but can also indicate the book’s target age (young adult, middle grade, etc.).

Form and audience are just other ways to give an initial sense of the best way to position your book in the market and in the minds of the industry professional you’re asking to read your book. And they can work together. For instance, maybe your book is a science fiction (genre) short story (form) that will appeal primarily to women in their twenties and early thirties (audience). Your book may find appeal beyond those labels, but it’s good for an agent, editor, or bookseller to know where to start. Who are the readers who are most likely to want to read your book?

Laura Zats: Pretending nonfiction doesn’t exist for the moment, I find it easiest to define the broad term “genre” starting with what publishing calls “genre books”—that is, thrillers, mysteries, romance, science fiction, and fantasy. Genre books are books that are writing to specific rules, things that a reader will expect to be there. This includes worldbuilding, settings, tropes, and even beats to the story. For example, you know a romance novel will always have an HEA (Happily Ever After) or at least an HFN (Happily for Now). From this, genre becomes a little more general, as there are fewer rules to follow, but still seeks to describe, succinctly, what the book is. An historical book will take place in an historic time period, for example. Genre is what the book is, compared to a term like category, which describes only the age range of who the book is for—this is why you have categories like middle grade and young adult and adult, but each category can have fantasy books in them.

Do you expect writers to indicate their genre in a query letter, or is it just as effective to leave it open ended, so that you can make the final call? Are you impressed when a writer deems their work “genre-bending” or “hybrid,” or is this too vague of an assessment?

TSF: Genre is very important to include. The purpose of your query letter is to intrigue the agent enough to want to start reading your work. Being able to give a sense of what type of book you’re asking them to read is a crucial part of that. It also shows you know your market.

I do love when a writer calls their work “genre-bending”—if that’s what it is—but I want to know specifics. Don’t just leave it there. Genre-bending in what way? Take a classic example in film. If I knew nothing about the movie “Alien,” calling it genre-bending or a genre hybrid would do nothing to tell me what I was getting into. But if you told me it was horror/science fiction, I’d be intrigued enough to want to read on.

LZ: Personally, I love working with books that are cross-genre or genre-bending, but crucially, every book still has a primary genre. Naming one primary genre tells me that you understand genre, that you’re a reader, and that you know where your book fits in the market. When I sell books that cross the boundaries between literary fiction and fantasy, for example, to literary fiction editors, I’ll call it a “work of literary fiction with speculative elements,” and to sci-fi & fantasy (SFF) editors I’ll call it “literary (literary being a quality mostly describing writing here) fantasy.” If a writer has a crossover, I encourage them to use the same technique for querying, with the caveat that stretching a description of your book to fit a genre will end up being a waste of your time.

Continuing this line of thinking, if a writer takes a granular approach to identifying their genre, does this give them an edge? A self-publishing writer who chooses an obscure enough genre often becomes a bestselling writer, at least in that genre. Could this same thinking apply to traditional publishing? Or is there a limit to the number of genres, subgenres, and other descriptors they should use when searching for an agent?

TSF: This is a difficult question because I think every agent and editor is different in what they’re looking for. I think the best thing to do is look at their websites and see what kind of information they’re asking for when you query them. For me, personally, if there’s a snappy marketing way of saying it (“this is an enemies-to-lovers, one-bed-only sci-fi/rom-com set on a spaceship orbiting Mars”) then I’m into it. (I’m not looking for a sci-fi/rom-com, but there’s a ton I am looking for and I love a well-done genre blend). However, if you need to go into more detail, it’s probably better to work it into the description of the plot or in a separate paragraph after you describe the plot.