Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 60

June 7, 2022

Looking for a Beta Reader? Flip That Question Around.

Photo by Ron Lach

Photo by Ron LachToday’s post is by author and editor Kris Spisak (@KrisSpisak).

Where can you find a “beta reader” for your manuscript?

It’s a question that writers often ask when they’re looking for early readers who can share advice on what’s working and what’s not yet there. Professional editors definitely can be transformational partners, but beta readers are often on the front lines of manuscript metamorphosis.

So, where are the beta readers we keep having recommended to us?

Well, to find them, smart writers should flip that question around: Where can you find writers in your genre looking for a beta reader?

Why do I argue for the flip? Two reasons:

Because helping each other is always a good thing (you’re not the only one with this dream!), andBecause the more you practice your editing skills, the stronger you will become as a writer.Voracious reading of well-written books empowers a storyteller, but so does donning an editorial hat. When we read as editors, it’s not just a matter of enjoyment. It’s an education, both for the writer we are helping and for ourselves.

Practice hones skills. We know that already. The more we write, the better we get. However, the creative journey is more complex than just putting words down onto paper. The revision process is often a less-examined segment of the writer’s life, yet we need practice here too. It is in the revision and editing stages where we cajole our characters to life, amplify the scenes our readers didn’t see coming, and where we spit-polish our language to a shine.

The more we examine entry points into stories and what is working and what isn’t, the more our own storytelling finds its footing.

The more we analyze someone else’s closing pages, the better we understand resolutions and the art of tying up all necessary threads.

Thus, the new question becomes: How can you be an awesome beta reader?

Think about more than grammar, punctuation, and spelling perfection.Think about celebrating strengths just as much as pointing out areas needing more work.When you see an awesome line, celebrate it.When you love a character, let the writer know.When you’re terrified or swooning or utterly fascinated, applaud how the scene is crafted.Think about specific notes that could be helpful to the writer.Where are you confused?Where does the story seem to wander off-focus?Where is a motivation or a plot twist unclear?Where does the story seem slow?When you finish, see if you can articulate what the book was about (the plot) in three sentences or fewer and what you saw as the overarching theme or takeaway. (The writer will be inspired when your understanding matches their own, or if it doesn’t, that too can be telling!)Think about what would be helpful to you if you were the writer receiving feedback.Critique with kindness not brutality.Remember you are in “editor” mode, not a “ghostwriter” tasked with rewriting anything as you would do it.When you can articulate to someone else why an aspect of a story isn’t working as well as it could, you will come to understand that element of craft in a greater capacity.

When you can pinpoint the moment that you were truly hooked in someone else’s manuscript and why (whether it’s page 1 or perhaps on page 37—hey, that’s what happens in early drafts sometimes), you’ll understand what might be necessary to create that hook in your own story.

While there are many books on how to write, there are far fewer focused on editing and revision. So, yes, read those (I might have a referral for you), but also practice. Practice on your own manuscript and practice with others. You can network and be a creative partner all while transforming your own creative future.

In the Q&As of my fiction editing workshops and webinars, the matter of where one finds a beta reader comes up almost every time.

So, I’ll repeat the answer I always give: Look to local writing communities you can join; look to genre organizations where you can network; look to online groups with solid reputations; look to those you know who read your genre who might have a thoughtful eye. But also look at yourself.

While you may be looking for a beta reader, so many others are too. Beta reading can be so much more than a chore. It can be a creative education. Lean into that. Your future books will be all the better for it.

June 6, 2022

Is Hybrid Publishing Ethical?

Photo by Karolina Grabowska

Photo by Karolina GrabowskaNote from Jane: Today’s post is by Meghan Harvey (@meggsaladpdx), Chief Strategy Officer at Girl Friday Productions. Girl Friday is a paid-for publishing service that also runs a hybrid arm, Girl Friday Books.

Last month, I wrote extensively about the nuances of hybrid publishing. It included two hybrid publishing case studies where the authors did earn a profit, which is not typical. Earning that profit required the authors to invest tens of thousands of dollars in printing, marketing and publicity.

I’m publishing Meghan’s perspective because I think she’s right that it’s problematic to equate ethical hybrid publishing with a positive return on investment for the author via book sales alone.

The publishing industry has been arguing for a long time about traditional vs. hybrid vs. self-publishing and which of these avenues are legitimate, and which are not, but a recent UK study that decries hybrid publishing as unethical has ruffled a lot of feathers.

Here’s the basic problem, in my view: these arguments ultimately conflate “ethical publishing” with positive ROI on a per-book basis. I’d like to take a closer look at that foundational premise, its inherent cracks, and offer a different paradigm.

Regardless of who pays for it, this is the cost to produce a bookMy operating assumption is that you want to create a quality book—a book that will be on par with the quality of every other book on the shelf next to it. Regardless of who is fronting the investment (the publisher, in the case of a traditional publishing, or an author, in the case of hybrid or self-publishing), it can easily cost upward of $20,000 to create the thing.

Yes, there is variance based on the book’s contents (if you need a fact-check or an index or photo permissions clearance, for example), word count, or printing specifications. There is also a great deal of variance in terms of the pricing you can find these services for—but generally speaking, you’re going to get what you pay for. Good designers and editors have fairly standard rates, so I’m using those here to illustrate what I call the actual cost of producing a high-quality book. If you cross-check these numbers with a traditional publisher, you’ll find they expect to outlay about the same amount when such responsibilities are handled by freelancers.

Three-pass editing (Developmental, Copyediting, Proofreading): $7,500

Cover and custom interior design: $3,000

Finding great editors and designers is an important task—one that many self-publishers have no interest, ability, or time to do. Partnering with a reputable hybrid publisher or a publishing services firm who continually vet their creative partners removes the onus of team curation from the author.

Project management and back cover copywriting: $5,000

Self-publishers can and often do take on their own project management. It takes around 120 hours of professional project management to produce a book, more for the inexperienced. A lot of authors decide this is not how they would like to spend their time and hire out project management accordingly.

Offset print run (let’s assume a relatively small run of 3,500 copies, for example): $8,750

Total creative investment: ~$24,250

These costs do not include marketing and publicity. A full-scale publicity campaign, for example, starts around $10,000. The vast majority of traditionally published authors receive limited marketing and publicity support from their publisher, so regardless of publishing route, the bulk of a book’s marketing and promotion responsibility falls squarely on the author.

The earning potential from a single bookPublishers, as well as many individuals deciding on a hybrid publisher or on self-publishing, are concerned with turning a profit on the project. So, let’s look at how many copies a book needs to sell to earn out the creative investment alone on a paperback with a list price of $18.95.

From $18.95, we subtract the wholesale discount. If the book is being sold into bookstores, 40-55% is standard.Then we subtract the distributor’s cut (18-20%).The hybrid publisher and author split the net revenue (let’s call that $9.23 in this case) along the lines of their specific deal, and these vary widely. Sometimes hybrids take 15%, others take 50% of net revenues. We’ll use 30% for this example, making author earnings ~$6.46/book.What this means is that, if all your books are sold through the brick-and-mortar channel, you would need to sell around 3,700 copies to break even on your up-front creative and printing investment. (Direct, non-retail-distribution-dependent sales channels earn more per copy.)

This sketch should shed some light on why traditional publishers are increasingly looking to acquire books that will sell more than 5,000 copies. It also suggests why publishers stress the importance of author platform: the author’s direct relationship with readers reduces the need to pile on marketing spend to reach sales goals.

Traditional publishers face ever-increasing printing costs and relatively stagnant retail prices (the market simply will not bear a $30 paperback novel, or even a $20 one). So they have little choice but to recover their margin with bulk rates for larger print runs. In other words, the sales projection threshold for a traditional publishing deal continues to move up, yoking publication to commercialization.

Is producing a book worth doing if it in and of itself is not a profitable project?There is not a single right answer to this. For some people it is, and for some people it isn’t. A book does not always need to be an ROI-positive event to be worthwhile. Many thought leaders and entrepreneurs write book-production costs off as a marketing expense, since they recognize the legitimizing value of a byline to their authority. A book can function as a lead-gen tool to drive conversion to contract sales; a book can act as a compelling business card that helps net new clients or speaking engagements; a book can drive an individual’s community engagement and retention. Many authors prefer to work in a hybrid or fully assisted self-publishing model because those avenues offer them more control over their work and rights, greater speed to market, and increased potential for return on their intellectual property.

I echo Jane Friedman in saying that “Most writers, regardless of how they publish, are motivated not by money, but some other reason. Prestige, Infamy. Status. Visibility. A million other things.”

This insight applies not only to nonfiction writers, but to novelists, children’s book authors, and memoirists as well, for many of whom producing a high-quality book is a lifelong dream. The value writers get from publishing their book often has little to do with the royalties it generates. As Jane describes in great detail in the aforementioned article, “The writer who makes a living from book sales alone is the exception and not the rule in traditional publishing . . . what most frustrates me, year after year, is why we believe or assume that authors have ever earned a reasonable full-time living from publisher advances or book sales.”

Hybrid publishing is not the best path for everyone. Here’s when it makes sense.Hybrid publishing is a business model; there is nothing unethical about it as long as everyone is clear on the terms. In a traditional publishing model, the publisher assumes most expenses associated with creating and releasing a book, and therefore takes the lion’s share of the reward or revenue. In most hybrid models, because the author takes most of the financial risk, they should also reap the majority of the royalties. If an author is willing to take on the financial risk for their project and would like to keep 100% of the royalties, they can certainly do that by self-publishing or even choosing a paid-for publishing service that offers 100 percent net.

So why do we need hybrid publishers at all? With the traditional model reducing risk for authors and the self-publishing model increasing stake and earning potential, why would anyone want to work with a hybrid publisher?

A good candidate for hybrid publishing is similar to an author who intentionally chooses to self-publish. However, the distinguishing factor of the hybrid model is national sales representation with brick-and-mortar retailers. What a hybrid publisher brings to the table is that sales muscle that a traditional publisher has, under a model that allows the author to retain control of their content and earnings. For some books this doesn’t matter so much, given that the majority of print books are now purchased online. For some books, the in-store channel is a key discovery point and will significantly contribute to overall sales volume. And for some authors, seeing their book on the shelves of a bookstore is a primary goal.

Measures of ethical practice for a hybrid publisherTo assign ethical purity to traditional publishers on account of their business model ignores the reality that there are bad actors across the industry. As in any industry, business ethics are about a commitment to transparency, integrity, and trustworthiness. Writers do need to beware. Armed with the following questions, writers can confidently select a trustworthy partner.

Does the hybrid publisher or services firm seek out clarity on your goals and idea of success before providing a bid for how they will achieve your vision?Does the hybrid publisher or services firm promise or even imply that you’ll be seeing a return on your investment over the course of a single book launch? If so, can they back that claim up with sales projections to support it? Does this publisher have comparable titles that have sold in the same volume range?Do they ever turn authors away? If so, what is their criteria for turning down a project? It’s a good sign if they turn down projects for which their capabilities do not align with the author’s expected results.Can they provide transparency about your anticipated royalty per book sold, by channel?Look closely at their terminology around distribution. “Distribution” is one of those smoke and mirror terms. If your hybrid publisher is offering distribution for your book but not sales representation, that basically means you will be in their catalog and orderable by booksellers, but buried amongst millions of other titles. Effectively, your books will not get bought into stores without sales representation.Are they transparent about the costs in their bid, as well as the potential for additional elective services? Beware of the bait and switch.The final and most important question to ask: Does your prospective publisher or publishing services firm have the author’s best interest at heart? Does their model reflect that posture? Does their relationship with prior authors reflect that experience? If not, keep looking.June 2, 2022

Getting Book Endorsements (Blurbs): What to Remember, Do, Avoid, and Expect

“i like you” by minnepixel is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

“i like you” by minnepixel is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.Today’s post is by author Barbara Linn Probst.

Seeking blurbs—that is, quotes and endorsements—is a pre-publication task that most writers absolutely hate.

However, unless yours is a front-list title from a major publishing house (in which case the publisher may get the blurbs for you), securing those important words of praise is up to you, the author. Not your agent or editor or publicist. You.

That means you have to ask established authors—people you may not know, who may have no particular reason for wanting to help you—to spend a significant chunk of time reading your book, write nice things about it, and affix their names to it forever-and-ever.

It’s hard to imagine why anyone would say yes to such an audacious request, yet people do, all the time; hardly a book is issued nowadays that doesn’t include a quote or two. The challenge isn’t how to get authors to provide blurbs; it’s how to get them to blurb your book.

With my third novel gearing up for release, I’ve been through the process three times. In some ways, the process has been similar each time, since behavior is shaped by temperament, and I’m still me. In other ways, it’s been different, since I’ve learned from experience (that is, from my mistakes).

I’ve also been on the receiving end of blurb requests. Experiencing the “blurb-seeking” process from the both sides of the desk has been quite illuminating. As I reflect on my responses and behavior as a potential blurber, I have new insight into the impact of my own actions—and, I suspect, the actions of others like me—as a hopeful blurbee.

First, though, some down-to-earth words on the overall subject of those longed-for endorsements.

Whom to ask?Unless the blessing of a specific expert is sought, I think it’s fair to say (in general) that who blurbs is more important than their exact words. “An engaging read” from a New York Times bestselling author with instant name recognition is, for most readers, more compelling than “one of the most fantastic books ever written” from someone they’ve never heard of. At the same time, getting that New York Times bestselling author to read and praise your book is hardly a slam-dunk.

For most of us, blurb-seeking is a balancing act between the clout of the potential blurber (aiming high) and the likelihood of obtaining a usable quote (aiming safe). Certainly, there’s nothing to be lost—except time—in writing to every famous author you admire in the hope that one of them will come through. On the other hand, there are so many pre-publication tasks that it’s hard to justify spending so much energy on a pursuit that’s unlikely to yield results—and what kind of results? How many blurbs do we actually need? Is quantity just as good as an A-list quote?

Asking high. If we want blurbs from people whose names will add perceived value to our book, it means we have to ask up. That is, we need to ask people who are more established than we are, better known.

But how far up? The higher we go—unless there’s a strong connection, as discussed later—the more the likelihood of a positive outcome diminishes. That may sound pessimistic, but authors are busy and many are understandably wary of affixing their good names to the work of someone they don’t know.

Not all authors are the same, of course, even the famous ones. Some give endorsements freely and frequently; other endorsements are nearly impossible to secure, although that doesn’t necessarily correlate with their perceived value. (By “perceived value,” I mean the weight the endorsement carries when a potential buyer looks at the cover or Amazon page and decides if the book is worth the cost. No judgment on the book’s “true” merit is implied.)

Asking safe. Some people prefer to ask peers—that is, writers they know, perhaps from a critique group or writing community—who are more likely to agree, whether from a sense of fellowship or the hope of reciprocity.

Asking “laterally” saves time and can spare us what can become an anxiety-ridden and depressing experience of silence and rejection, which may bring back unhappy memories of pitching to agents and publishers. Who wants to go through that again? Yet these peer endorsements might not add much to the book’s perceived value—or is any endorsement better than none?

There’s no universal answer to that question. Again, it’s a balancing act between energy, resources, temperament, and goals.

The big question, regardless of whom you ask: How to get to yes?When I ponder my own experience as the one being asked, a few things stand out. I’m only one person, and hardly a famous one, yet the things that make me say yes or no might not be that different from the things that make others say yes or no.

Each of my yes experiences has been different. In one instance, I had read the person’s previous book and thought it was excellent, so I was primed to expect her new one to be good too. We’d also established a bit of a relationship: we had common acquaintances; she had given me a lead on a blurb for my second book (though it didn’t pan out); and she’d commented on my social media posts. My agreement was likely from the start.

In another instance, the request came from a stranger who had clearly read—and understood—my first novel; she even included a quote from Georgia O’Keeffe that she planned to use for her own book’s epigram. I couldn’t resist having a look at the opening pages, which she attached. I was pleasantly surprised—and hooked. Here, my agreement was unexpected.

When I’ve said no, on the other hand, I’ve nearly always known I would decline as soon as I read the email. Sometimes, it was for a practical reason: because I don’t read ebooks, it won’t work if the person can’t offer a print version. On occasion, the timing was too tight. And at other times, it was the letter itself.

I’ve received several emails that began like this: “Because of all the awards you’ve received, I think you would be a very good person to endorse my book.”

My response is usually: “Oh? And why is that?” If there is nothing in the email to indicate that the sender had read (or liked) either of my novels and felt a resonance, I’m left with a feeling of being used. And that’s a direct path to no.

The first two examples, resulting in yes, were thoughtful and personalized. The last example, resulting in no, was not. A similar request (another no) even included the sentence: “I hope to read one of your novels someday.” Ouch.

What to remember, throughout the processYou’re asking a huge favor. Be grateful, but express your appreciation in deeds, as well as words. That means promoting the person’s book on social media, not just the fact that she’s blurbed you. Be sure you’ve posted glowing reviews of her books (on Amazon, social media, etc.) long before you ask for an endorsement.

At the same time, don’t apologize for asking. And don’t worry too much about “revealing” that you have, or will seek, additional blurbs and theirs won’t be the only one on the back cover. These authors have been through the blurb-seeking process too; they get it.

Have good manners. Thank the person for her consideration. If she says no, thank her again for her courtesy in letting you know and wish her the best. Don’t argue, bargain, or offer a work-around. It’s a small world, and you might meet each other again.

If she doesn’t reply at all, refrain from nagging unless the person has explicitly asked you to check back. She might be your dream blurber, but after one follow-up (two at most), let it go.

What to do (and avoid doing)Be concise and professional. The subject line should make it clear what the email is about. Do not be cute or coy.

Give some information about your book, including genre and length so the person will know what she’s committing to, if she agrees. Believe it or not, I’ve received requests that contain absolutely no indication of what the book is about, other than the title!

When I’m the one asking, I usually say that I’m pasting a summary at the end of the email or attaching a one-page summary. Make it easy for the person to get a sense of your work, become intrigued, and want to read more (yup, just like pitching to an agent).

Give her a way to find out more about you. Include a hyperlink to your website and Amazon page (if you have one).

Say when you need the endorsement. Allow enough time (say, a few months).

Be explicit about the fit. When I seek endorsements, I begin by telling the person why I loved her book, with specific examples to show how it’s touched me. Yes, I only ask people whose books I really love; it’s the best way to make a sincere request.

Admiration alone isn’t enough, however. There has to be a clear indication of the fit. You have to tell the person:

Why you’re asking her, specifically, rather than some other Famous AuthorWhy you think she might like your book, specifically, among all the other novels she might endorse. Why do you believe it will resonate with her?Telling the person how much a quote would mean to you, and how aware you are of how busy she must be, is courteous and appropriate. But it’s rarely enough to get you to yes.

Establish a point of contact. Make it personal. Show that you belong to similar worlds. Without that, it’s hard to get a quote from a busy author who has to make intelligent choices about how she spends her time.

The best kind of contact is a direct one: if you’ve cultivated a relationship over time, talked at a conference, attended one of her events. Shown up for her.

If not, look for a secondary point of contact. Do you have a common friend who can facilitate the introduction? Ask the friend if you can use her name in the email request, and cc her on it. One way to find that “common friend” is to look at the acknowledgement pages of the would-be blurber’s books and see if there is anyone you know on the list.

In a pinch, you can go to a bookstore and look at the new book displays to see whom this person has blurbed recently. “Because you loved X and Y books, I think mine may light a similar spark since it’s also about Z.” At the very least, this shows that you’ve done your homework and makes a case for that crucial fit.

Note: A “point of contact” has to be book-related. The fact that you both grew up in southern New Hampshire or have golden retrievers might be nice, but it’s not sufficient.

Offer choices. To help the person decide, offer to send sample pages and/or a synopsis. Unless the person already knows your work, it’s hard to commit to reading an entire manuscript without a preview.

However, do not attach a Word document of your entire book with your query email; that can appear presumptuous. And do not suggest that the person could “save time” by reading a few sample chapters that you’d be glad to select. If someone asks for that, of course you should agree, but it’s not your place to suggest it.

Offer a print copy/ARC or a digital version/PDF. If you don’t have ARCs yet and time is short, or if you are not going to have ARCs, offer to send a spiral-bound printed version for people who don’t like to read on devices.

If you mail the book, send it first class, not media mail! It’s worth an extra five dollars to make sure it arrives in days, rather than weeks. And always include a cover note that thanks the reader for her time and includes a way to reach you.

What to expectAn immediate yes is rare. Often, the response to your request will be some form of maybe.

There are different kinds of maybe, however. “I can’t get to it until April, will that work?” and “I’ll be glad to have a look” have different implications. In my experience, the former has a decent chance of resulting in a blurb, with flexibility and a bit of persistence; the latter, a slimmer chance.

There’s also the frustrating experience of what I’ll call the prolonged maybe: a series of heartfelt assurances that “I’ll do my best.” Some of the loveliest authors I know have kept me hoping for months with prolonged maybes until, eventually, the deadline passed. It’s possible, of course, that it never was going to become a yes, and the person didn’t want to hurt my feelings or close the relationship. I’ll never know—and it doesn’t matter.

My advice is not to take this kind of neutral placeholder as more encouraging than it really is. Stay in touch and then, when it’s clear that the blurb isn’t happening, thank the person for considering the possibility of a quote and tell her that you’ll ping her on social media when the book is published. That way, you might end up with a social media boost, which is also valuable.

Inevitably, some people will say no—immediately, eventually, or because they never respond.

There are many reasons you might hear no, even if your pitch was great and your book might be great, too.

The person doesn’t have time right now. This might be a polite excuse, or it might really be true. (This can be awkward if you were hoping for an early blurb to use on an ARC, but would still be thrilled with a blurb, later, for the final book. You can try to be honest and offer additional time, but be aware that it might be perceived as pushy and might not make a difference.)She’s working on a book of her own that is similar to yours and doesn’t want to muddy her mind. (Yes, this has happened to me.)She’s just gotten a ton of other blurb requests and has to prioritize those that are from people she knows better. Unlucky timing, but so be it.She believes that blurbing your book will not be good for her own reputation—though she won’t say that directly. Sad, but it happens. I had one person, whose novels I truly loved, express appreciation and interest in mine, and then ask, “Not that it matters, but who is your agent and publisher?” Obviously, it mattered—to her, although not to others I approached. Once I told her, I never heard from her again.The person just didn’t like what she read—although, again, it’s unlikely that you’ll hear this directly. Most often, there will be a radio silence or a last-minute: “So sorry, I just didn’t have time to get to it.” Don’t let it upset you, even as a potential explanation. There’s no book ever written that every single person liked.There are things going on in the person’s life that you have no idea of. In the era of COVID, that is a stronger possibility than ever.And sometimes, of course, the answer will be yes. When that happens, here are a few things to remember while you’re rejoicing:

Ask her how she would like to be identified on the book cover, Amazon page, press release, etc.Don’t change the quote without permission. Sometimes people will tell you to use whatever part of the quote you like, but you should still let them know (in advance) how the final blurb will read.Send a copy of the final book, later, with a personal note.Pay it forward.And most important…While stellar blurbs are great to have, they aren’t the only—or even the main—thing that readers care about. In my own research, 750 readers told me that the reasons they buy a book from an unknown author are: the cover and title, the short book description on the back, and recommendations from friends they trust. Not Kirkus reviews or awards or blurbs, and certainly not the logo of the publisher on the spine.

The purpose of blurbs is to help you attract the people who will read, enjoy, and find meaning in your work. They are just one of the many ways to find those people!

June 1, 2022

The Hybrid Publisher Debate: Do You Have the Right Mindset?

Today’s post is by author Debbie Weiss (@DWeissWriter).

As an author with She Writes Press—my first book comes out this fall—I’ve been following the articles about the costs charged by hybrid and paid-for publishers, and I think they’re missing the key point which is: does this author have the right mindset? The issue, at least to me, isn’t just about the contractual return on investment, but whether the author can make that investment worthwhile.

Publishing today is so much about the author as marketer. Do they already have a huge email list, or a business to which the book adds value, or perhaps a frighteningly cute cat who already has 30,000 Instagram followers and doesn’t mind sharing? The question is, can you be an effective salesperson for your book?

She Writes Press warns that most first books do not make a profit, and specifically recommends that their authors think of writing as a business. All excellent advice that I accepted in theory—until I came up against the fact that I found it far easier to be a task-driven insurance coverage lawyer than a self-starting book promoter.

Being an author means not just writing a book but reaching out to more established authors for blurbs, and developing an advertising strategy on multiple platforms, and asking to be on podcasts, and garnering the attention of influencers. We didn’t have the word “influencer” in my youth, and for that I am grateful. Or maybe I’m just jealous that I will never be one, unless I find a truly photogenic cat or discover a miracle diet.

In short, being an author today means asking people you don’t know to do stuff for you, and as my therapist said in our last session, “Most people don’t feel comfortable asking strangers for things.” As a lawyer, people asked me for things and since that’s the role I went to school for and knew well, I’m far more comfortable advocating for a legal position instead of my own creative work, or even more difficult, trying to promote myself.

This struggle was exemplified by my efforts to put together my first newsletter. I was at a loss for something interesting enough to say that people would want me in their inboxes. Then again I did spend most of my professional life interpreting insurance policies, which is about as interesting as it sounds.

I’ve blogged for years, and even had an essay published in the New York Times Modern Love column, as well as Woman’s Day, Good Housekeeping, Huffington Post and Reader’s Digest, but I never got a real following or many opportunities out of it. So despite years of writing—and trying to get that frowny faced SEO widget on my blog to smile—I have failed to influence.

Like most of the questions posed in my law school classes, the correct answer to whether a hybrid publisher is a good choice is “It depends.” The issue isn’t just whether the publishing contract is economically beneficial, but whether a given writer is someone who can benefit from the opportunity. Do they have the wherewithal and the resources to effectively promote their book? In this arena, chutzpah is a good thing.

Before making a publishing decision, I would recommend any aspiring author do a deep self-analysis about what they are willing, and want, to do in support of their work. This past year, after signing my publishing contract, I wound up moving from my home of almost thirty years to a new place. I also started living with a new partner. All of this has been good for me, but it hasn’t made me the most diligent author-marketer. In retrospect, I should have been more realistic about my life potentially being in flux when my book needed a lot of attention.

Another element missing from the current debate about paid-for publisher options is that not all of them are equal. My publisher provides its authors with an excellent education across many different aspects of publishing. And it includes a like-minded community of writers who are resources, or who sometimes just commiserate over how much time—and yes, money—it takes to be an author today. I appreciate how She Writes offers a comprehensive and professional framework for a motivated author to go after her dreams.

But no publisher can guarantee whether those dreams will come true. Any publishing choice has risks, and a book’s success depends on so many factors, from whether it happens to garner the support of a big influencer (that word again) to the state of the world, which seems to be spinning out of control these past few years.

In short, grouping all hybrid and paid-for publishers together is far too simplistic, and picking the right publishing option depends on every author’s own thorough self-assessment. Like the legal disclaimers state, individual results may vary.

May 25, 2022

Promote Your Book with Your Values

Photo by cottonbro from Pexels

Photo by cottonbro from PexelsToday’s post is by author Sonya Huber (@sonyahuber).

Like many authors, I had a book to promote during the COVID-19 pandemic and still today each one of us faces the threat of illness and too little bandwidth for a promotional blitz. Shilling our wares can be draining, so I decided to ask the unreasonable from my book promotion: that it give me something back.

At first this felt like a short cut. I was juggling Long-COVID, a full-time job, and the raising of a teen, so it seemed necessary to do what made me happy rather than adding to my exhaustion. I realized, looking back on past events, that the way to gain energy from book promotion is to focus on my values.

I’ll admit that this awareness started somewhat by accident. During the long promotion for a book of essays on chronic pain, Pain Woman Takes Your Keys and Other Essays from a Nervous System, I was asked to do a few workshops for people with chronic pain hosted by nonprofit organizations. As I enjoy teaching and interacting with workshop participants, I knew how to promote and prep for these events. Unlike a reading, where I often feel like I’m begging audience members to sit passively and listen to me for an hour, a class felt like a dialogue, a chance to connect, even if it was on Zoom.

Then I started to think about the numbers. As an author, I’ve experienced the discomfort of an in-person reading with two people in the audience, both of whom are bookstore employees. The time invested in planning a reading—never mind the task of getting a bookstore to agree to host a university press author—rarely offered meaningful returns in terms of book sales or visibility.

When I began to offer free workshops with writing prompts built around my book’s theme, my audience counts were ten times what I’d been able to pull in for a reading. Plus, the focus shifted from “me” to “us”: I got a chance to interact and be spontaneous, to read and hear writing from participants, to dialogue about questions that emerged from writing prompts, and even to do some writing myself.

So when I had my next book to promote—an essayistic memoir about a single day in my life (Supremely Tiny Acts: A Memoir of a Day)—I thought up a format for online classes that allowed participants to write and share on what had happened to them that very day. These “Day-Ins” ended up providing moments of calm focus amid our anxious pandemic lives and were, even over Zoom, a great social bonding activity.

This doesn’t mean that every book promotion event needs to be a class. Instead, I realized, I wanted to do book events that do double duty, that allow me to align the things I care about with the time I spend on promotion. My personal values include community engagement, but they also include a wide array of causes from disability rights to racial justice to the environment.

When I planned a tour for a book on identity and health insurance (Cover Me: A Health Insurance Memoir), my most satisfying event was a bookstore reading that was co-hosted with a health access nonprofit. I sold a few books and was joined on stage by an organizer who talked about legislative efforts and gave attendees a chance to get involved and contribute financially.

To think about your values in terms of your book, you might consider some of these questions:

What kind of setting are you comfortable or energized in?What themes from your book might connect to fun or meaningful activities?What causes and organizations might your book connect to?Are there existing non-book-related activities that might feature your book as an add-on?Are there specific populations you might reach out to in order to provide a free experience other than a reading, but with the same ultimate awareness-generating benefits for you as an author?What non-writing skills would you donate to a cause you care about, and how might those skills allow others to learn about you as an author?What kinds of events or experiences have you always meant to try? Could you use one of those to build a fun or meaningful group activity that also happens to feature your book?As I focused on building activities that feature my books, I found friends and strangers eager to take me up on the idea of a free class for their book group or community center. And in each case, I made sure to offer attendees a worksheet that had both a summary of my key points and writing prompts along with my contact information, an image of the book cover, promotional blurbs, order information, and a discount code. I don’t know whether these ultimately contributed more or less to my sales figures than traditional readings, but I am a happier author as a result, and the next book tour looks less like an onerous chore and more like a creative challenge.

May 24, 2022

The Julie & Julia Formula: How to Turn Writing Envy Into Writing Success

“happy birthday, julia child!” by Rakka is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

“happy birthday, julia child!” by Rakka is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Today’s post is by author Catherine Baab-Muguira (@CatBaabMuguira).

Genuine, widely applicable career-hacks are rare in the writing life. But I do know of one. In all honesty, it is the single greatest writing-career secret I’ve ever stumbled across—like really stumbled across, feet flying out from under me, coffee mug launched into space—and I won’t even make you skim 800 words to discover it.

The secret is fandom: dedicated and even obsessive engagement with another writer’s work. I learned this firsthand, the hard way, and it led to the agent, auction and “Big 5” book deal of my nerdiest dreams. I just never thought to codify until I heard it discussed on a podcast.

A couple of weeks ago, on You Are Good, a film-discussion show, the journalist Sarah Marshall happened to be analyzing Julie & Julia. “You can reach your dreams by loving another person’s work,” Marshall said, identifying this as the central dynamic of the 2009 movie. In case you haven’t seen it, Julie & Julia tells the true story of Julie Powell, a frustrated young writer who, in the early aughts, started blogging about her attempt to cook every recipe in Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking.

The blog eventually grew so popular that it became a book, then a movie directed by Nora Ephron. Which is a way of saying that, through her fandom of Julia Child, Julie Powell most definitely reached her writing dreams, and then some. Meanwhile, Sarah Marshall recognized her own career in this fan-guru dynamic. Turns out she’s a giant Nora Ephron fan, and Ephron’s work had helped her become successful in just the same way.

This is my story too, I thought, listening. Other people have had this experience??? We should call it the Julie & Julia Formula!

How the formula works in generalStep one: Desire to have a writing career.

Step two: Try to write. Fail.

Step three: While stewing in frustration and envy of those who’ve somehow made it, develop an obsession with the one person whose career looks so great, so transcendently beautiful and awe-inducing that you just want to puke.

Step four: Use this obsession as either less direct inspiration or very direct inspiration.

Step five: Profit.

How it worked for meThe process sounds simple and easy, and in one sense—the retrospective sense—it is. In my case, living it felt different. Sadder. Less funny, less straightforward.

I stewed literally, in a too-small bathtub in a too-small house I didn’t want to be living in. I wasn’t where I wanted to be in my writing career, either, and this fact helped tip me into the sheer worst depressive episode I’ve ever experienced. I couldn’t eat, sleep or function. I had to take mental-health leave from my job.

Some strange intuition led me to take Edgar Allan Poe off the shelf for the first time since I was a kid. My brain had gone limp, too broken down to make sense of TV or any other book than, apparently, The Complete Tales of Mystery & Imagination. Looking back, I reason that it was because only Poe’s work was bleak enough to match my mood. I was searching out evidence to confirm my darkest feelings, and I found it in Poe. But not only that.

Before I knew it, I’d grown completely obsessed, tearing through his stories, essays and poems, then moving on to the biographies—and there are dozens of Poe biographies. That’s before you get to the fan art or the academic criticism or the film adaptations. It’s hard to believe (a) how much he created and (b) just how much he’s inspired, and all this in spite of or possibly because of his tragic life. I was fascinated, drawn out of myself, weirdly yet wonderfully enlivened.

Betting that I wasn’t alone in finding Poe a perverse hero, I pitched an essay about all this to The Millions, and when it came out in September of 2017, it went viral in a literary-world sort of way. My inbox swelled with emails from fellow travelers. About this time, out for a drink with my longtime mentor, I rambled on about the experience and the larger Poe phenomenon.

“That sounds like a book,” he said.

Initially, I scoffed. “Oh yeah, I’m going to write a book about reading Edgar Allan Poe for self-help and call it How to Say Nevermore to Your Problems.” (Stop me if you’ve heard this one before.)

Soon enough, I got cracking on a book proposal, and in the week after I sent that to agents, I received four offers of representation. Eighteen months later, my book sold at auction to Running Press, a subsidiary of Hachette.

The delay in the sale came, in part, from me not understanding my book’s genre. Because what do you call an intensely personal take on a famous writer? Figuring this out took me lot of googling circa 2018; let me save you the trouble. It’s called bibliomemoir, and there are many, many comps in case you want to go this route. Look to Harry Eyres’ Horace and Me. Michael Perry’s Montaigne in Barn Boots. John Kaag’s Hiking with Nietzsche. The genre is prominent enough now that there are viral tweets dedicated to mocking it.

In time, I realized I wanted to take myself out of the project and focus entirely on Poe. For this, too, there is ample precedent, stretching back decades. Check out Alain de Botton’s 1997 How Proust Can Change Your Life. Or more recently, Sarah Bakewell’s At the Existentialist Café. Or any of Ryan Holiday’s mega-popular books on Stoicism.

They’re just the nonfiction examples. Anna Todd’s After and Robinne Lee’s The Idea of You both grew out of an obsession with Harry Styles, that great rival of Chekhov and Trollope. E.L. James’ Fifty Shades of Gray began as Twilight fan fiction. Seth Grahame-Smith’s Pride and Prejudice and Zombies explains itself. Grady Hendrix, for his part, essentially earns a living as a horror fan, burlesquing the genre and racking up bestsellers from The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires to The Final Girl Support Group.

How the formula can work for youYou may be laboring with a novel or focusing on nonfiction. It doesn’t really matter. To get a traditional book deal, you need a specialty—a story only you can tell, a topic only you can cover—plus an audience wanting that coverage.

So ask yourself: What writer does it for you? Who’s the Julie to your Julia? Is there some literary IP that you love so much it’s a borderline problem? Bingo.

Your audience may flow either from your own platform or, far more handily, from your subject. Anna Todd didn’t invent One Direction from whole, sweaty cloth. Nietzsche remains a lot more famous than John Kaag. The point is, it’s far easier to tap into a large existing audience for a subject than it is to try to build a platform of equal size. And if your subject is popular enough? Your own platform just became a lot less important.

Suddenly, agents return your emails. Acquiring editors call. Sales numbers start to stack up. And you’re launched.

This is the Julie & Julia Formula, some heretofore hidden wisdom coming to you via a Russian doll of influence that nests back to literary time immemorial, and for what it’s worth, you have my blessing. Go forth and publish. Lose yourself in envy, obsession, love. Maybe lust, too, why not? Could be your ticket.

May 18, 2022

Nonfiction Writers: Find Your External and Internal Why

Photo by Luke Webb from Pexels

Photo by Luke Webb from PexelsToday’s post is excerpted from Blueprint for a Nonfiction Book by Jennie Nash (@jennienash). Join her on June 9 for the online class Land a Book Deal with a Better Table of Contents.

When I ask my clients why they want to write a book, they will often start by giving a simple answer: “I want to share what I have learned” or “I don’t want other people to suffer like I did.” These answers are part of the truth, but they often shield deeper reasons. These reasons, this deeper why, form the core of your motivation and momentum; you’ll draw on these reasons when you feel despair or imposter syndrome.

If you never ask yourself why you are writing, you are far more likely to write in circles, fall into frustration and doubt, and come to believe that writing depends on some elusive muse or a series of special habits (e.g., write 1500 words a day, write for an hour every day, write when the full moon is waning) rather than deep self-reflection, discipline, and persistence.

Identifying your why first has an enormous impact on your capacity to both write and complete a book that resonates with your desired reader. It’s often the difference between writing a book that people want to read and either (a) never finishing, or (b) finishing, but writing something that is so watered down and wishy-washy that it fails to make an impact.

You can write your way to an answer—absolutely. I have done it, and writers I know have done it, and we have all heard of famous writers who have done it, but the truth is that for most of us most of the time, it’s wildly inefficient, ineffective, painful, and unnecessary. That’s why we start with why.

Your external whyLet’s start with the external reasons why you want to write a book—things you believe writing a book will get you in the world. These are probably connected to the return on investment (ROI) of your time, energy, and money.

At the top of most people’s list is the desire to be recognized more broadly for their expertise. Writing a book is about becoming seen and heard. Different people have different concepts of what recognition and validation look like. It might be that you are quoted in the publication of record for your field or offered a column there. It might be that you are invited to speak at a prestigious event. It might be that the people you admire in the field come to admire you.

Many people hope that writing a book will make them a lot of money in book sales, and it might. You could receive a $25,000 advance from a traditional publisher or a $150,000 advance or a $1,000,000 advance, and then you will receive 15 percent royalties on every book sold once that advance earns out.

Or you could work with a paid-for publisher, which requires an upfront investment from the author. Michael Bungay Stanier’s business management book, The Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead Forever (published by Page Two Books), has sold more than a million copies. He makes between $4 and $6 per book, plus the book drives business and revenue for his consulting firm. That all adds up to a robust return on the investment of writing a book.

Most people, in truth, don’t earn anywhere near that much money. The New York Times reported in 2020 that 98 percent of books sold fewer than 5,000 copies. This reality means that writing a book might not be a great financial bet if you rely solely on book sales to earn out your investment of time and effort. “The majority of writers don’t earn a living from book sales alone,” writes Jane Friedman in The Business of Being a Writer, “People don’t go into the writing profession for the big bucks unless they’re delusional.”

So why bother?

Because of the possibility of making an impact and extending your reach. My client Jenn Lim, author of Beyond Happiness: How Authentic Leaders Prioritize Purpose and People for Growth and Impact, a Wall Street Journal bestseller, introduced me to the idea of what she calls “the other ROI”—meaning ripples of impact. Lim’s book is about finding purpose in the workplace and living that purpose every day. The ripples of impact happen when you connect with fellow humans in an authentic way. Writing a book gives you a way to make an impact and spread your ideas far and wide. This often leads to lucrative consulting or speaking gigs, the opportunity to collaborate on interesting projects and initiatives, and the chance to be part of powerful conversations.

Here’s how Michael Bungay Stanier puts it: “We’ve all seen our marketing heroes grow a base of fans, then customers, then empires through ‘content marketing.’ And the big kahuna in content marketing is the book. This is how you officially rise to ‘Thought Leader’ status, it’s how you differentiate yourself from your competitors, you drive revenue, you launch your speaking career, you start hanging out with other cool authors.”

Thought leaders definitely hang out with each other. I love to listen to podcasts about business, personal growth, and creativity, and I am often struck by how all the authors at a certain level know each other and boost each other’s work. Adam Grant appears on Brené Brown’s podcast when his new book comes out, and Brené Brown appears on Grant’s podcast when her new book comes out, and then you see that they both have been on Guy Raz’s show and you start to notice that Indra Nooyi is in all the same places talking about her new book, too. All these thought leaders know each other and read each other’s work and promote each other’s work to their massive audiences. These are ripples of impact at a high level, but even at less stratospheric heights, the ripples work the same way, and they can be profound.

Here are what the ripples of impact can look like:

You attract followers who are interested in hearing more of what you have to say, expanding your ability to influence, educate, illuminate, comfort, or entertain people.You attract the attention of traditional media when they are looking for experts to quote in your industry.You attract the attention of podcasters and radio and TV producers.You receive invitations to speak at industry events and at events outside of your field.You can easily share your most powerful content with key audiences.You have reason to connect with other influencers—to strike up a conversation, collaborate, and connect with each other’s audience.You have the chance to build a legacy around your thinking.These are the reasons people invest the time, energy, and money in writing books—and some of these outcomes come with financial rewards far greater than the book itself.

It’s important to identify your external why for writing a book, but there is another layer of motivation to understand as well.

Your internal whyThe internal reasons people write are the ones that tend to sustain them through the roadblocks and challenges of a long development process. These reasons might come from a place of rage or injustice, simple jealousy, a different way of looking at things than the prevailing wisdom, or a deep-rooted sense of social justice. Often people who have something to say are saying it in opposition to something else—some other idea, or social movement, or injustice, or prevailing belief, or experience they’ve had.

Writing is all about raising your voice and staking your claim. You speak your truth, claim your authority, take a stand for what you believe in. We can talk all day long about how to write—both the craft of it and the practice of it—but the hardest part by far is stepping into your power.

I have the great privilege of working with people who are very accomplished in their fields—entrepreneurs and executives and thought leaders—and every single one of them rubs up against the difficulty of raising their voice. Will people care? Do I have the right to tell this story? Is it good enough? Will it matter? These are not only questions the beginner asks; these are questions every writer asks. And they are questions about raising one’s voice.

The way to answer these questions and combat the doubt that comes with them is to connect to your why. Tap into your motivation, the reason you care, your rage, and your passion. That is how you find your voice and how you finish your book.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, please join Jennie on June 9 for the online class Land a Book Deal with a Better Table of Contents.

May 17, 2022

How a Little Psychology Can Improve Your Memoir’s Setup

Photo by Lisa Fotios from Pexels

Photo by Lisa Fotios from PexelsToday’s guest post is by editor and coach Lisa Cooper Ellison (@lisaellisonspen). Join her on May 18 for the online class Memoir Beginnings.

Every memoirist faces the same dilemma: where to begin, what to keep, and what darlings to cut. Many writers either freeze or overwrite act one, because they want to immerse you in that special soup of hilarious-terrifying-crazy-and-weird that inspired them to write their story. But a setup that drags on too long can lose your readers.

In Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need, Blake Snyder calls the early part of act one the antithesis, or the world before your journey begins. Your main job in this section is to reveal the Six Things that Need Fixing—or the narrator flaws and problems you’ll resolve by the end of your book.

Narrator flaws generally fall into three categories:

Flaws of perceptionProblematic behaviorsInterpersonal issuesFlaws of perceptionFlaws of perception include misbeliefs and faulty thinking, what psychologists call cognitive distortions. These flaws are the internal problems that impact your narrator’s worldview. We form these flawed perceptions based on our assumptions or lessons we learn from our experiences. Common cognitive distortions include black-and-white thinking, jumping to conclusions, or catastrophizing. These cognitive distortions can lead to beliefs like I should never ask for help, if I’m not perfect no one will love me, and good women don’t get angry.

It’s not uncommon for writers to create extensive lists of faulty beliefs or cognitive distortions when first working on this exercise. But limit yourself to two or three, then laser in on the scenes that reveal them.

Studying lists of cognitive distortions, common flawed beliefs, and even Twelve-Step character defects can help you identify your narrator’s internal struggles. Once you know them, you’ll understand what motivates their behavior, which leads to our next item.

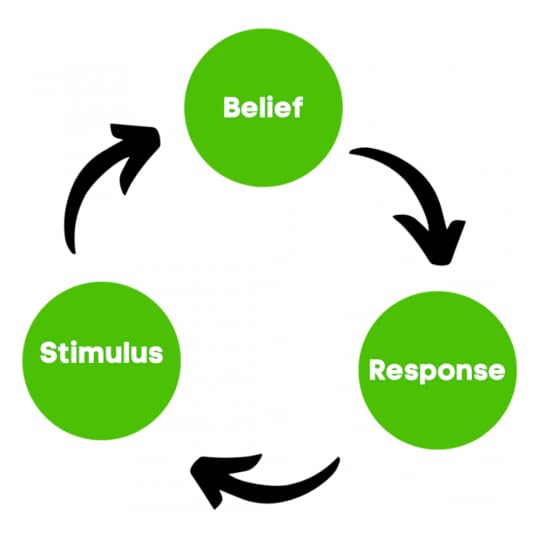

Problematic behaviorsBehavior arises from our worldview and follows the following format:

stimulus (outside event) › belief (internal filter) › our response (external action)

Some of our actions look great on the outside, but actually get us into trouble, like people pleasing or trying to be superhuman. Then there are the ones most people know are problematic, like passive aggression, hypervigilance, or using silence as a weapon.

When you link your narrator’s beliefs and thoughts with external behaviors, your manuscript will benefit in three ways:

If beta readers and critique group members have encouraged you to show more and tell less, identifying your problematic behaviors (actions) will help you pinpoint which things you must show in the forward-moving story. This can help you limit your opening’s backstory to the most essential items.You will develop a tight cause-and-effect chain between events, which is how you create a propulsive opening.Learning about how beliefs and cognitive distortions feed behavior will give you more compassion for your characters. For example, most people hate it when someone tries to control them. Yet, few know that control is fueled by deep fear of losing something we value.Returning to the Twelve-Step list of character defects and exploring lists of maladaptive coping mechanisms can help you uncover the two or three actions that need fixing. While it can feel painful or awkward to examine unflattering traits, revealing your flaws will turn you into a trustworthy narrator readers are more likely to care about.

Interpersonal issuesIn storytelling, every hero has an antagonist, or a character who creates obstacles in their path. That means most conflicts take place between characters. Many bestselling memoirs are populated with characters who behave badly—just look at Mary Karr’s parents in The Liars’ Club, Tobias Wolff’s stepfather in This Boy’s Life, or Krystal Sital’s grandfather in Secrets We Kept: Three Women of Trinidad. While these characters were either born or thrust into these relationships, many of our antagonists are people we’ve chosen to be with.

Before exploring the problems between your characters, return to your ending, so you can see which relationships have transformed. Look for ones that have fallen away as well as those that have taken on a new form.

Understanding which relationships have changed will help you determine who must be developed in act one, and who’s part of your story’s context. This is essential, because many memoirists use too many act-one pages to develop flawed parents, abusive family members, or painful situations that provide a context for the narrator’s current reactions. But if transformed versions of those relationships don’t appear in your ending, they’re probably not as important as you think.

Once you know who’s important, it’s time to determine what’s going on between them. Most issues fall into one of the following categories:

Communication: you share and listen equallyTrust: you honor your wordBoundaries: you’re not too close or too far awayRespect: you see and understand my perspectiveSupport: you’ve got my backWhen assessing each essential relationship (there’s probably one major and one minor one), consider which aspects have changed or improved. Do they communicate more honestly, see each other more clearly, or relate in a new way? In the setup, reveal the opposite.

Once you’ve explored these three areas, you’re ready to create your final list, which might look a little like this:

I see things in black-and-white (internal)I believe I need to be perfect (internal)I’m a chronic people pleaser (external)I don’t ask for help (external)My partner doesn’t respect my boundaries (between)My mother tells me what to do (between)Next, identify one scene that represents each item on your list. If you’ve written more than one, choose the best example, then repurpose the rest of your material in another project. Focusing on the Six Things that Need Fixing can eliminate your act-one dilemmas regarding which aspects of your story’s special soup readers need to consume. Develop them well, and you’ll hook your reader and keep them invested in your memoir.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join Lisa on May 18 for the online class Memoir Beginnings.

May 16, 2022

Why Write When the World Is on Fire?

“Sunrise w/Distant Fire” by Susan Smith is marked with CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

“Sunrise w/Distant Fire” by Susan Smith is marked with CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.Today’s post is by regular contributor Susan DeFreitas (@manzanitafire), an award-winning author, editor, and book coach. She offers an online course, Story Medicine, designed to help writers use their power as storytellers to support a more just and verdant world.

Over the course of the pandemic, many of us struggled as writers, and many of us independent editors and book coaches faced some version of the same question from our clients: Why write a novel when the world is on fire?

It certainly feels like a reasonable question. We don’t spend hours in universes of our own making when a hurricane is bearing down on the city where we live. We don’t occupy ourselves with imaginary conversations with imaginary characters when real people are calling for justice right outside our door. And we don’t spend time daydreaming about plot and character when the house is on fire.

But where do we turn when we’re waiting out the hurricane in the hotel of a distant city?

Where do we turn after the protest has passed, and we’re struggling to make sense of what we witnessed?

Where do we turn when we’re trying to figure out how to pick up the pieces of our lives and move on after the house has burned down?

We turn to stories.

Here are three reasons to keep writing, even when the challenges in the world at large feel overwhelming.

1. Novels offer solaceI don’t know about you, but in times of trouble, books have always been my refuge. They’ve been there for me in times when no one else was (like the cafeteria in sixth grade) and in times of great uncertainty (like the period of my life when I had cancer).

And in this I’m not alone: as print sales over the last two years have shown us, in times of trouble, people turn to stories.

It’s easy to feel like your story is only meaningful to you, because you’re the one who’s writing it. But the truth is, the author of every novel you ever loved probably felt that way at some point or another.

Keep writing because stories matter.

2. Novels change the readerYes, stories can offer us a much-needed escape from the pressures and challenges of this world. But they can also offer us a source of moral courage in grappling with those pressures and challenges.

When I think of the books that have had the most impact on me, books that have shaped the way I think, act, and see the world, I think of books like Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, Ed Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang—and, more recently, Rene Denfeld’s The Enchanted, Richard Powers’s The Overstory, and Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing.

Not surprisingly, many of these same sorts of novels have been targeted in our current wave of book banning crusades.

The next time you start to feel like writing fiction is pointless, in the face of the challenges we’re facing in the world at large, ask yourself: If fiction doesn’t have any real power in the world, then what are all these people so afraid of?

Write because stories have power.

3. Novels change the writerRemember when I mentioned the period of my life when I had cancer? As anyone who’s faced a diagnosis like that can attest, it has a way of clarifying what really matters to you, and what really doesn’t—and one of the few things I realized I regretted, at the point when I received mine, was the fact that I had not yet published a book.

If writing and publishing a novel is on your bucket list too, then let me just affirm this for you: doing so is one of the most meaningful things you will ever do with your life.

All in all, I’m a firm believer in the power of storytelling. That’s why I developed my course, Story Medicine: to help writers of fiction claim their power as storytellers, and use that power to effect positive change in the world.

In times of sickness, times of cultural upheaval, and times of real existential threats, like nuclear war and climate change—I think stories matter more than ever.

So wherever you are, if you’ve been struggling with this question, Why write when the world is on fire?, remember: Your words are water.

May 12, 2022

Your Journal as Time Machine

Photo by abdullah . from Pexels

Photo by abdullah . from PexelsToday’s post is by writer and creativity coach A M Carley (@amcarley).

You know how time expands and contracts? The feeling that you’re living your life in the middle of a cosmic accordion, and some force of the universe is working the bellows. Contracting—Where did the day go?—expanding—I can’t believe I just drafted an entire chapter!—and sometimes just chugging along normally.

Although who can say what’s normal?

One of the best places for me to meet and experience expansive time is in my journal. I like to think of it as my little readymade time machine. Open the pages of my marbled-cover composition book and I can stretch a few minutes into something meaningful.

For example, I have appointments today at 10 a.m., 12:30 p.m., 2 p.m., and 4 p.m. In those in-between spaces I won’t be able to focus on anything because I’ll know the next thing is hovering. My day is trashed, and it’s only 9:15!

But that kind of self-talk is not helpful. So it often makes sense, almost paradoxically, to make some time, from 9:15 to 10:00, for sitting comfortably with my journal. I can think out, with my pen, how to maneuver the day. Where will I be between appointments if some of them involve travel? If they are all virtual, and I’ll be under my roof all day, what to-do items will fit into the gaps and be flexible enough to allow for last-minute changes? When will I take breaks? Eat? Make some tea? Go for a quick walk? Write?

For years, I imagined I might be the only person who gets like this—who takes a passive stance as to the passage of time. Then I got into conversations with other people, often writers, who knew all too well that same sense of having “lost” or “wasted” chunks of time that they wanted to have filled with work. Bad enough that we’re graceless with our use of a day. Then the second arrow aggravates the loss when we berate ourselves for it.

There’s an overlap here with another phenomenon—the delaying tactic or mistaken belief that the only usable time for creative pursuits comes in big chunks of hours at a stretch. I won’t go there now except to mention all the essays and blog posts out there from authors who wrote entire books in the little moments they made: waiting in the car for their child to get out of school, stopping for ten minutes before going into the grocery store, etc.

We ARE timeFour Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals by Oliver Burkeman goes deeper. He suggests, as have others before him, that we ARE time. Not something outside of us that can be contained, managed, segmented, or mastered, time is inseparable from our embodied selves. From this stance, it’s even more up to us, right? There’s no point trying to objectify time as something outside ourselves that speeds up or slows down or sneaks away or runs through our fingers. It’s entirely up to us. So in that case, I’m for using my journal to savor the time that is my life.

Someone is due to arrive at 11:15 to look at the washing machine, and it’s now 10:57. I can’t DO anything because I’ll be interrupted as soon as I begin.

In this scenario, I’m pre-agitated, and the repairperson’s van hasn’t even pulled up yet. But I can perch near the front door and open my journal. Ahh. Something useful to focus on, disperse nervous energy, and—who knows—come up with an idea or two. And if the person due at 11:15 is delayed, that’s fine with me, because I’m occupied with something positive and useful.

Time confettiResearch indicates people nowadays “have” more free time than in previous eras, if the time is measured cumulatively over 24 hours. This may seem hard to believe. But it feels like we have less because available pieces of time are tiny slices of only a few minutes per slice: time confetti. That’s Brigid Schulte’s apt term for the little bits of time that are unprogrammed for people in western societies these days.

I’m supposed to leave at 5:30 and it’s 5:17. I can’t DO anything because there’s no time.

While tidying up is an option for those thirteen minutes, another option—especially attractive if the day so far has felt more like a forced march than a carefree saunter—is opening up my journal. I can stand, blank book in hand, and jot down ideas, lists, narratives, memories, questions, reminders, and more before I head out the door. When I go out, I’ll be feeling a little buoyed up from having given myself a few minutes of expanded time in that brief interlude between all the scheduled things.

Counter-productivityLearning what to do with those little slips of time can be a challenge. One main reason Schulte gives for how we wound up with confetti-size pieces of time is our incessant connection to email, social media, and other 24/7 communications. Spare time, even in tiny slices, is a boon. Often I find the best use of a sliver of time is to drop into an awareness of my breath and shift into a lower gear. One way to make that shift is to put pen to paper in my journal. I’m not interested in becoming a productivity fiend, driven to wringing the last second out of every minute. Reaching for my journal at odd moments feels calming, not “productive.”

When you begin to count on your journal as a companion, you may notice ideas surfacing that you want to be sure to add to the pages. You can develop habits to support that impulse. You can start to apply some of those awkward short bits of time to jotting things into your journal. Bits of time confetti, no longer thieves of your day, become useful, yet calm, moments.

Finally, with time and distance, the pages of your journal offer another kind of time machine—a portal that transports you from the here and now to multiple snapshots of your internal world, over the years.

Go ahead. Step into the time machine.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1885 followers