Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 56

October 25, 2022

What You Should Know About Writing a Co-Authored Book

Photo by “My Life Through A Lens” on Unsplash

Photo by “My Life Through A Lens” on UnsplashToday’s post is by Allison Kelley (@_alikelley), co-author of Jokes to Offend Men.

When people hear about my feminist, humor book, Jokes to Offend Men, first they ask: Do you actually hate men? (The answer of course is no, only on Thursdays).

And then they say: Wait there’s four authors? How does that work? A four-person book is an outlier, but what’s even stranger to me is that I am one of those authors.

Prior to writing this book I had none of the qualities it requires to write collaboratively. In fact I rejected the premise. But now, two plus years after I started, I am a convert. If you are also a type-A, control seeker that’s been scarred by having to work on group projects in school, I see you. I am you. But done right, group writing has some surprising benefits I hope you’ll consider.

When it comes to writing, I have always been wary of sharing the spotlight. In college, I took comedy writing classes in male-dominated spaces where I had to fight to have my voice heard. And on those rare occasions when I finally got people to listen to what I had to say, I held on for dear life.

I internalized those experiences throughout my twenties. I was always deeply protective of my writing and highly suspicious of anyone who was trying to “change my words.” I took all feedback extremely personally and didn’t know how to accept it without compromising my vision.

When people critiqued my work, all I heard in my warped brain was: You are not cut out to be a writer and you should give up now. What I didn’t realize until years later, was that (1) writers are not judged on the quality of their first draft, and (2) my self-preservation method was holding me back.

If you want to write collaboratively, you can’t be afraid to show the ugly stuff.In my thirties, everything changed. I managed to get a few clips under my belt, writing humorous personal essays about my holy trifecta: 1990s pop culture, teen angst, and the suburbs. I also started writing satire for sites like McSweeney’s. This boosted my confidence and then, critically, I joined an online community of writers who I grew to respect and trust. Eventually that led me to achieve the very thing I was terrified of in my twenties: Being vulnerable.

We swapped pieces and gave each other feedback and for the first time I had some measure of what other people’s early drafts looked like. I was relieved and genuinely shocked to find out other people worked through multiple revisions. With the assurance that I would not be laughed out of the group, I began to solicit feedback, and then I watched as my writing *miraculously* became so much better.

You have to trust each other.Over time, I developed a rapport with a few particular writers who both shared my sensibilities and were incredible editors. Then, a few years after I joined the group, the stars aligned. I finally had an idea and had the people who could help me write it.

The viral McSweeney’s piece, which served as the inspiration for Jokes to Offend Men, started out as a single joke. I knew it had potential, but on my own I had no clue where to go with it.

For 25-year-old Ali, the story would have ended there. I would have abandoned the idea, too afraid to show anyone my half-baked thinking and the judgment I was sure would follow. But 35-year-old Ali was learning to trust the people around her.

I emailed the other writers the joke: “A man walks into a bar. It’s a low one, so he gets a promotion within his first 6 months on the job.”

And then I asked, “Is this anything?,” knowing that at worst they too wouldn’t know what to do with it, but at best, it might inspire them and together we could make it “a thing.”

Through some mix of right time, right place, right painful lived experiences, the four of us were able to co-write and publish Jokes I’ve Told That My Male Colleagues Didn’t Like in a whirlwind 24 hours.

When that took off, I was ecstatic! It was the biggest thing that’s ever happened to me. I didn’t know it could get bigger. And again, if it was just me, the story would have ended there. Not bad, but certainly not a published book. It wasn’t until one of my co-writers suggested we expand the idea into a full-length book that a new dream began to take shape.

You have to slow down and be patient.My entire life I’ve been racing to the finish line. Somewhere in the two years it took to write and sell our book, I put this quote on my phone as a reminder to slow down: “Be patient with yourself. Nothing in nature blooms all year.” Patience is a virtue I wish for anyone in the slow-moving world of publishing, but when writing a book with three other people, it takes on a whole new meaning.

Writing collaboratively means taking the time to hear each other out, consider other perspectives, allow someone to talk through their idea even if it’s not fully there. While our book is funny, we’re pulling from heavy source material re: sexual harassment, reproductive rights, the gender equity gap. I had to learn to give my co-writers the space to express what was important to them and what was frustrating them.

There were many times throughout the process of writing our book where I so desperately wanted to skip ahead to the pretty, finished end. I am nothing if not a conflict avoidant child of divorce and I hate the murky middle of things. But that is life and as it turns out, it was those lively discussions where we hashed it out and dissected the validity of every single joke, that made the material stronger.

You have to be committed to the idea and each other.Another rule that applies to all authors: you better love your idea because you’re going to be spending a long time with it. But the particular nuance of co-writing comes from the commitment to each other. I think one of the scariest parts of writing on a team is that you are relying on others to get the job done. You have to be accountable to yourselves, and I’m talking about even before you sign any contracts holding you legally responsible.

Our original piece was published in February 2020 and shortly after we began meeting virtually on a weekly basis to write and talk. We were buoyed by the success of our one piece, but we knew writing a book-length volume of jokes was a totally different beast. It was awkward at first. We had to find our rhythm, not just in the writing, but as partners.

Amazon • Bookshop

Amazon • BookshopOther than giving each other feedback and meeting in person once or twice, prior to writing this book most of us did not know each other that well. But we believed in the idea and were committed to giving it a shot. It became clear early on that we each offered something unique and having an equal partnership was the only way it was going to work.

That was no small feat—at the height of our workload we were meeting every week for 3-hour phone sessions, in addition to independently writing throughout the week. But that’s a testament to how much we all wanted this book to work. And it’s a testament to the power of co-writers. They can push you to dream bigger and accomplish something you never could have done on your own.

October 19, 2022

Writing Through the Impossible

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

Photo by Markus Spiske on UnsplashToday’s post is by author, editor and coach Jessica Conoley (@jaconoley).

One of the most phenomenal (and underrated) parts of having a creative freelance career, like writing, is our ability to mold the job to our needs.

Need flexibility to pick up kids? You’ve got it.

Want to learn about poisons of the sixteen hundreds? No one is stopping you from researching for 72 hours straight.

We have ownership of our time and our projects. We also have the freedom to shut our work down and devote ourselves to some other aspect of our lives.

But sometimes shutdowns just happen. And even worse sometimes these unplanned shutdowns are due to hardcore life chaos. Maybe it’s the death of a loved one, dissolution of a partnership (romantic or business), or a house fire that stops your writing and everything else. What we think was a temporary shutdown ends up being a life-altering event, and we have to find a whole new way of existing in order to move forward.

So, what do you do when you’re faced with an unexpected shutdown? How do you stay true to your creative ambitions and still handle what life is throwing at you?

I struggled with that question for 16 months as my mom was dying.

Here’s what got me back on my writing track.

GratitudeIt’s hard to find things to be grateful for when your life is in cinders, but gratitude primes your brain to look for solutions and positive opportunities amidst your awful situation. It helps shift your perspective and eventually may lead you to hope. I spent those months feeling grateful for:

The freedom to take on as little work as I wanted to. If I had still been tied to a corporate job, I wouldn’t have had the same freedom over my time. I wouldn’t have been able to care for mom the way I wanted to.The ability to lose myself in work. A lot of those 16 months sucked. Bad. I didn’t want to face them or think about them or feel them. Sometimes I didn’t. Somedays I buried myself in work and was grateful my career could be a sanctuary.Clients and colleagues who showed time and time again they valued me as a person, not just as an editor, coach, or writer. I was careful with the details I chose to share, but my clients and colleagues consistently showed me the good in the world, when it would have been so easy to get lost in the bad.When you’re faced with the unimaginable and feel like writing is the farthest thing from possible, take five minutes to write about what you are grateful for at that very moment. You can start by listing five small basics: I ate today. I have fluffy slippers on. The sun came out, etc. If you’re feeling really ambitious, add some sensory details to flex that writing muscle. That simple list proves you have written—which as you know feels very, very good.

QuietA new reality was being built around me, and if I remained in autopilot-disaster mode, I would end up in a place I never intended to go—the place where writing had turned into something I used to do. I was the only person who could figure out my best way forward, but under the barrage of external pressures, I couldn’t hear myself think. To find some quiet I reduced external noise by:

Silencing phone notifications. Text messages, phone calls, email, and social media alerts were all paused. Immediate family, doctors’ offices, and my three BFFs were the only people I let ring through.Setting out-of-office notifications everywhere. I’m out on family leave and have delayed access to messages. If you need immediate access to me, please text. Thank you for your patience, and I look forward to speaking with you. Here’s the sneaky trick I pulled: I DIDN’T include my phone number in the out-of-office message. If the person didn’t have my number already, we didn’t have the level of relationship that warranted an immediate response.Curating my media intake. I only followed adorable animals and positive, introspective snippets. I stopped reading the news. My watching and reading habits turned to the familiar: I rewatched all of The Golden Girls. I let go of my self-imposed rule that I had to read only new books. Instead, I reread the same two books for 16 months straight.If you have a physical reaction when something pops on your radar, that’s a good place to set an out of office, hit mute, or establish a boundary. In the midst of chaos, it’s time to do what’s right for you. As you claim your quiet time, you make space to find clarity about the next best step for you—and don’t be surprised if the next best step is sleep. Your brain knows it’s much easier to write once you catch up on rest.

Self-careWhen I quieted all that noise, I realized that the path I was on led to mental and physical exhaustion—and exhaustion is not conducive to quality writing. While it felt like the last thing I could do was invest in myself, quiet, sensible me knew that feelings are just warning signs that something needs attention. Quiet, sensible me knew if I didn’t take care of myself, I wasn’t going to be able to take care of mom. Quiet, sensible me decided self-care was a top priority, regardless of time and financial restrictions. I looked at self-care that had worked for me in the past and recommitted to:

Exercise. I doubled the number of Pilates classes I was taking. Yes, it was good to move after so much time in waiting rooms and driving to doctors’ appointments, but having my teacher tell me what to do and not having to think for one whole hour was positively wonderful. I went on long, slow, walks outside because fresh air felt like a luxury after stagnant hospital air.Massage. Stress raises toxin levels in the body which leads to wear on your immune system. If I got sick, I couldn’t be around my chemo-treating mom. The clock was ticking on the number of days left with her, therefore getting sick was not an option. Massage had been an intermittent indulgence of the past, but it became a bi-weekly routine so my immune system could do its thing.Meditation. Sitting still, breathing, and sorting through the crap rolling around in my head helped bring that external quiet and calm to my internal thoughts. It gave me space to hear myself think and trust that the next step I was making was the right one for me. (I know some of you are rolling your eyes, and that’s totally okay. Early 2017 me thought meditation was a load of crap too, but that’s a different essay.)Writing. Writing is how I process emotions and learn lessons to my bones. Like many other creatives, if I am not actively creating, my mental health suffers. I committed to writing in any form I could muster and told myself judgement about the quality and usability of the writing was future-me’s job. All current-me had to do was get words on the page.Writing was the hardest self-care for me to implement because I didn’t want to process what was happening. If I processed what was happening, it meant mom was really dying. All the time I wasn’t writing, I was in denial, which served as a coping mechanism and helped me through some really horrible moments. But, in the quiet I knew it was time to start accepting the inevitable.

When you’re investigating the right self-care steps, if there’s one that feels impossible it may be because that’s the place you do your heavy emotional processing. If you aren’t ready to process yet it is okay. Only you know when it’s time to move to that next step of acceptance. (I strongly suggest muting anyone who is trying to force you to move on before you’re ready.)

The questions to ask yourself are: Am I not doing this because it’s hard? Or am I not doing this because I’m not ready, yet? When you have your answer take a moment to be proud of yourself. Asking that question is very hard to do. Answering it honestly is even harder. You can decide what you want to do with that answer tomorrow.

Baby stepsI’d accepted writing, even though it was going to feel hard, was my next right step. After a few weeks of physical self-care, I had the energy to contemplate what writing might now look like. But, as I contemplated what to work on, overwhelm set in—words felt impossible. I sat in paralysis for a few days, before realizing I needed to back up a step—I’d missed the before-the-words-on-a-page part of writing. I wanted to start with something I knew I could accomplish, so I set a few micro-goals like:

Open my writing software. That was it. I didn’t have to write. I didn’t have to read. I didn’t have to decide what I was going to work on, all I had to do was open Word because that small action was a step toward new words.Read something I had written. I only released one creative-ish piece of writing in 2021. I opened it and read it. Because I’d been on hiatus, I saw it more objectively. It was good. If I could do that once, in the middle of the worst of it I could do it again—because now I was taking care of myself.Set a timer for five minutes and sit in front of an open document until the bell goes off. I needed every hack I could find at this point and muscle memory is real. Minute-by-minute my body sunk into my writing chair and reminded my brain this chair, this time of day, this sitting in front of my computer looking at an open document was something I did. Eventually, my body tricked my brain, and I deleted a word or two.They were monumental, minuscule victories. (They also didn’t take very long, which was good because I was still running short on time.) I documented each win by adding a sticker to the calendar in my kitchen. As I made my morning tea, I’d look at the stickers. Most of the time I wished there were more, but sometimes I’d remember to be grateful for the handful that managed to make it onto the board.

What baby steps can you see that will move you forward? Even more important, how are you going to celebrate each of those baby steps you take? Place your celebration reminders in a place you see every day, multiple times a day. Subconsciously, each time you look at them, you acknowledge your progress and empower yourself to take the next step forward in creating your new normal.

BuildIt was time to leverage the momentum from those baby steps into permanent this-is-my-new-existence-change. The most effective way to do that was by turning writing into a ritual I craved as much my morning cup of tea—an act where the day just felt wrong without it. It was time to turn writing into a habit.

Habit stacking (when you pair something you want to start doing with a habit you do daily) held the way forward. The one self-care I consistently accomplished, regardless of how bad things got, was meditation. My brain and body were fully committed to that deep quiet time to myself and wouldn’t let me skip it. If I linked it to meditation, my brain and body couldn’t let me skip writing either. After meditating, I habit stacked by:

Immediately sitting down in front of my computer.Opening only the piece I wanted to work on. All other tabs and applications stayed closed.Silencing my phone and (gently) tossing it across the room. On days when phone distraction was particularly tempting, I stashed it in the really fancy wooden box on the mantle in a whole different room.Setting my nursemaid software time for one minute longer than I had the day before. (Nursemaid software is internet/app blocking software that won’t let you access certain websites until the time limit expires. The one I use is called SelfControl.)Writing until the timer went off. I built up from five minutes on that first day. For word count oriented writers, you may want to try the Mary Robinette Kowal method of shooting for one sentence the first day, two the second, three the third, etc.Build up your writing sessions by looking at tasks you have consistently completed throughout the chaos of your shutdown. What do you do no matter what? Drink coffee? Take the dog out? Listen to a podcast? Great, you’re halfway there. Now, how can you pair writing with that daily habit? It may take a few tries, but eventually your muscle memory and habits will automatically cue your body that it’s time to write and you’ll get to the desk on autopilot.

Try againSix minutes eventually led to seven, eight, and nine; but the real milestone would be if I could hit 25 minutes. In pre-sick-mom reality, that was when I made myself stand up and move around so I wouldn’t turn into the hunchback writer of Kansas City. I made it to eleven minutes. We got notice mom’s cancer had come back. I stopped writing. Then one morning I thought maybe I should try again:

I went back to the baby steps and began at opening a Word document. I built up to 14 minutes. Mom got put on hospice. I stopped writing. Then one morning I thought maybe I should try again.I went back to the baby steps and read something I had written. I built up to 17 minutes. Mom died. I stopped writing. Then one morning I thought maybe I should try again.I went back to the baby steps and sat in front of my computer for five minutes. I built up to 22 minutes. I got fantastic work news and wanted to call mom and tell her, but she wasn’t there to answer the phone. I stopped writing—but this time it was for a day-and-a-half, not weeks or months, so I sat down at my desk, set the Nursemaid timer for 23 minutes and tried again.I needed the stops. You may need the stops. The writing isn’t easy. The rebuilding your life isn’t easy. If today is a stop that’s fine. If this week is a stop that’s fine. If this month is a stop that’s fine. You will remember the baby steps and take them faster after every stop. You will try again because you get to create the life you want, and creation isn’t always fluid and linear. It’s made of starts and stops and trying again. And the good news is you don’t have to do it alone. You will try again when you are ready.

SupportI had a solid creative support triangle in place before mom got sick. In my newfound quiet, I understood also needed a mom-is-dying support triangle. Looking through all my silenced notifications I reached out to select friends, family, and colleagues asking for what I needed. Some of the more unusual ways I relied on my support were:

Having my roommate open any physical mail that looked suspiciously “well intended.” He knew whether the contents would send me into an emotional tailspin or not.Asking a friend who was beta reading the same manuscript as me if I should finish it. (There was a cancer diagnosis in the opening pages.) She immediately told me to stop. I emailed the author and politely bowed out of the beta.Publicly declaring I was writing again and sharing my daily sticker progress with social media followers. I engineered the situation so I felt like people were counting on me to keep writing. That amorphous social media commitment got me into the writing chair many times, when all I really wanted to do was go to bed.People want to help. When we’re in a shutdown they often don’t know how. Only you know what you need right now. It’s okay to get creative and specific in your asks. People appreciate when you are clear. Some people are going to “help” in ways they think are best, but you have no obligation to accept. It’s okay to say no. Does an offer of assistance bring you comfort, lower your stress level, or ease the situation significantly? Great, say “Thank you.” And take the help. Who listens when you tell them what you need? Those are good people to reach out to. Your support system is one of the easiest things to be grateful for when you’re looking for something to add to that gratitude list.

Before mom died, writing only these 11 pages in three-and-a-half months would have felt like failure. But in this new reality it doesn’t feel like failure, it feels like a baby step.

I’ll keep building up my time until I make it to four 25-minute blocks a day, and one of those days I’ll find the courage to start writing fiction again. That’s how and where I’ll really emotionally process what I have lost. But that feels too hard. I’m not ready, yet.

Just like writing this felt too hard not so long ago, but I needed to write it to know I still had the ability. And now it’s time to share it because someone out there needs to read it so they can move forward with their own feels-impossible project. And when they share their creation, someone will need it, too and so on. This is how we build our new way of existence. This is how we move forward.

October 18, 2022

How to Avoid Taking Edits Too Personally

Ask the Editor is a column for your questions about the editing process and editors themselves. It’s a place to bring your conundrums and dilemmas and mixed feelings, no matter how big or small. Want to be considered? Learn more and submit your question.

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by 805 Writers Conference. The 805 Writers Conference delivers the information you need to succeed in publishing—all of the tools, skills, and resources—available virtually and in person—November 5 & 6. Conference sessions, specialty workshops, and a book expo featuring 50+ authors. Join us at the beach!

QuestionI’ve just written my first nonfiction book, about gardening in my region. It’s a compilation of twelve years’ worth of newspaper and magazine articles and blog posts, about 45,000 words total. I’m planning to self-publish with a hybrid publisher, meaning I have to edit the manuscript, choose the fonts, choose and insert the photos in the right place, and so on. After the line edits, I have a proofreader in place, then I’ll send it off.

A retired editor friend of mine referred me to a working editor friend of hers to do the first edit, a line edit. I also asked for the editor’s thoughts about whether the title conveys what the book was about, and to see if the slant about gardening in the region was obvious. After she looked at the manuscript and did some editing on the first chapter, we agreed to work together and settled on a fee.

I didn’t realize how horrible I’d feel when the first round of edits came back. The changes in format and content, comments about structure, and questions about the content deflated me after two hours. I felt like nothing I’d done was right, that a year’s worth of work was being torn apart. In tears, I was afraid to tackle it the second day and the third.

My retired editor friend told me I was taking the edits too personally. She and I worked on a query and a book proposal of mine a couple years ago, and it took a toll on our friendship. We got through it and now we laugh, but she’s acutely aware of my response. She assured me that editors edit for the reader, not to chastise the writer. That was and still is hard for me to see.

So my question is, how can I detach from the process and thicken my skin?

—In Tears

Dear In Tears:First things first: This sounds like a really challenging project! Combining different short bits of writing into a coherent whole is quite a puzzle in itself. Plus, it’s very likely that over twelve years, your style and approach to writing have evolved, maybe in ways that you haven’t been able to notice, because you’re so close to it. Which is just to say that as a starting point, it might be helpful to remember that this is a very complicated project you’ve undertaken.

In fact, the nature of this project reminds me in some ways of another kind of project: home organization! I wonder whether it could help to think of your book project as a closet make-over: you have collected twelve years of stuff, and let’s say you’ve spent a fair amount of time working on it on your own; you’ve emptied the closet and tossed the truly no-good stuff, removed the stuff that actually belongs in the attic, grouped similar items, and so on. You’ve put everything you want to keep back in the closet, more or less. But you know it could be better.

You want your closet to look the way a stranger’s closet looks at the end of an HGTV episode—everything just so, orderly and easy to make sense of, with clever storage solutions and labels. A place for everything and everything in its place, etc.

So you’ve called in help! You’ve hired an expert closet-organizer, who has jumped in to do her thing. She’s re-grouped some of your items, in the process discovering that you have, actually, no fewer than fourteen blue scarves, and she’s wondering whether you really meant to keep them all. Where you had sorted things into a stack of shoe boxes, she’s brought in a system of nifty containers, with a slightly better size and more regular dimensions, clean panels so you can see what’s inside, and a spot for a nice label.

And, looking at it all now, you’re feeling a little embarrassed. You didn’t realize you had so many scarves, and ok, fine, that stack of shoe boxes was pretty wobbly and likely to fall over in the first week. You’re seeing all the things you might have done better, and the closet-organizer’s changes feel like a criticism.

But here’s the thing: the closet organizer isn’t thinking that at all. Sure, she saw problems, but she also understands that most people struggle with organizing the detritus of 21st-century life. In fact, she’s built a profession around helping them with this challenge!

The closet-organizer has two big advantages in this scenario:

First, it’s pretty easy to be objective about the contents of someone else’s closet. The closet-organizer doesn’t have a sentimental attachment to the shoes you wore to your wedding but can’t fit into now. (Do you need to keep these? she’ll ask politely. Could they be stored somewhere else, perhaps in the back corner of the closet or in the attic or maybe even not in your house at all?)

Second, the closet-organizer has organized a lot of closets, while you’ve probably mostly focused only on yours. That’s why you’re paying her! She’s learned, over time, which kind of hook holds up and which is plastic crap that will break the minute you hang anything heavier than a necklace on it. She’s learned that it’s worth it to get matching hangers, and she’s a whiz at that shirt-folding trick that lets you see everything in the drawer.

A small side note: can I promise that the heart of the closet-organizer is pure as driven snow? I cannot. It is possible, maybe even likely, that, deep down, she maintains a secret list of truly, exceptionally disastrous closets she’s encountered. (Yours probably isn’t one of them.) She might quietly be thinking, Lady, let some of the scarves go. (If she said that out loud, that’s a different story; I’m assuming your closet-organizer’s comments and notes were all polite and professional.) But you can’t really worry too much about that. And I can almost guarantee you that, ultimately, she’ll take some—maybe even a lot of—satisfaction from helping you tackle that closet. And you should, too: you’ve done a lot of work!

At the risk of stretching this metaphor too far, it’s also only fair to acknowledge that there’s another layer here, logistically: I’ve sort of assumed the kind of reality-show scenario where you left someone to organize your closet while you had a nice weekend away at the beach. But in fact, getting a manuscript back full of tracked changes is a little more grueling than that because you actually have to decide whether to approve each step: Do you need this blue scarf? How about this one? What if I move this blue scarf here, and stack this other blue scarf on top of it? Can I put the scarves in front of the wedding shoes, on the third shelf? Oh, but that doesn’t leave room for the shoes, so maybe they should move down a shelf.

And it’s true: that process can very quickly feel overwhelming. So I’m also going to suggest a little hack that might make it feel a little more like the reality-show beach-trip scenario. When I send line edits to writers, I almost always send two versions of the file. The first version has everything tracked in: formatting changes, sentence-level suggestions, queries, notes, straight apostrophes changed to “curly,” etc. It can look like a lot of changes, especially if global changes in formatting (every single apostrophe, changed!) are tracked in—sort of like getting a paper back covered in red ink. To make the second file, I save a copy of the first file and then accept all of my suggested changes in one fell swoop. I tell writers that of course they don’t need to accept all of my suggestions, but that it might be easier to start from that clean file and then go back to the other file when it seems helpful. In other words, it’s sort of like “Ta-da! Here’s what your closet would look like if I organized it, but see what works and what doesn’t work for you, and then we can go back and play around with it some more if you don’t like how parts of it look.”

Which is to say that, if you generally trust your editor—as it sounds like you do—maybe a way to approach the manuscript you got back is to take a bit of it, save a new file, hit “Accept All Changes” and see what it looks like. In the best-case scenario, you’ll be delighted by how well the manuscript reads: there’s all of your stuff, just a little more shipshape than you left it. Probably, you’ll still have a little bit of rearranging and polishing left to do. And ultimately, especially given that you’re self-publishing, you can decide to accept or reject any of the changes—keep every single scarf, if you really must. But I suspect that not having to engage with every single change might make the whole process feel a little less daunting.

Good luck!

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by 805 Writers Conference. The 805 Writers Conference delivers the information you need to succeed in publishing—all of the tools, skills, and resources—available virtually and in person—November 5 & 6. Conference sessions, specialty workshops, and a book expo featuring 50+ authors. Join us at the beach!

October 17, 2022

Using Weather to Convey Mood in Fiction

Photo by Erik Witsoe on Unsplash

Photo by Erik Witsoe on UnsplashToday’s guest post is by writing coach, workshop instructor, and author C. S. Lakin (@cslakin).

Writers are sometimes told not to write about weather. It’s boring, right? An unimportant element that adds nothing useful to a story. Dry details. Who wants to read about a dark and stormy night? No wonder Snoopy never got past typing that first line of his great magnum opus.

But weather affects us every moment of every day and night. We make decisions for how we will spend our day, even our life, based on weather. And weather greatly affects our mood, whether we notice or not.

Since we want our characters to act and react believably, they should also be affected by weather. Sure, at times they aren’t going to notice it. But there are plenty of opportunities to have characters interact with weather in ways that can be purposeful and powerful in your story.

Ways to use weather effectivelyWeather can be used to convey moods in fiction because we tend to associate specific feelings with certain kinds of weather. Rainy days to many are gloomy. Sunshine makes us feel happy.

But characters in our fiction—just like you and me—might react to weather much differently than expected due to the mood they’re in. I love the fog and rain and cold of autumn—especially after a scorching hot summer. But someone with SAD (Seasonal Affective Disorder) might find such weather depressing.

Weather is often used metaphorically and as motif in fiction. In my novel Someone to Blame, Matt is fighting his grief over the loss of his two sons. In this moment, the weather is used to show his unclarity about his life:

Matt brushed the remnants of broken glass off the passenger seat and got into his truck. Fog enveloped him as he left the parking lot, erased his surroundings. He leaned forward to find the road through his windshield. Gravel turned to asphalt; houses drifted by like ghosts.

As he drove back to town he searched his feelings, tried to assess whether he was upset, angry, or what. It wasn’t the lack of feeling that set him on edge as much as the realization that he didn’t care. His life had fallen into patterns of routine, of requisite conversation. Of measured responses and expected behaviors. He knew his heart was numb, all the nerve endings severed. He was sleepwalking through a different kind of fog. Somehow he couldn’t see a way to connect the dots of his life.

Note how weather is used strategically to both enhance and mirror Matt’s mood and feelings in that moment. The weather gets him thinking deeply about his life by the imagery used sparked by the weather.

Here is a passage from Carlos Ruiz Zafón’s novel The Shadow of the Wind, which brings mood and weather into play:

That Sunday, clouds spilled down from the sky and swamped the streets with a hot mist that made the thermometers on the walls perspire. Halfway through the afternoon, the temperature was already grazing the nineties as I set off towards Calle Canuda for my appointment with Barceló, carrying the book under my arm and with beads of sweat on my forehead. … A grand stone staircase led up from a palatial courtyard to a ghostly network of passageways and reading rooms. … I glided up to the first floor, blessing the blades of a fan that swirled above the sleepy readers melting like ice cubes over their books.

Zafón’s passage combines the elements of the weather with bits of physical description, setting a mood for the locale that affects what his character notices. He’s keenly aware of the heat, and though he never thinks Boy, it’s hot, we sense his discomfort by the beads of sweat, the appreciation for the swirling fan, and his observation of the “melting readers”—a strong and fresh image that sums up the impact of the weather.

Here’s another passage from the same book, again showing how the weather description helps set the mood of the character. I’ll put in boldface the masterful words used to paint a mood picture:

A reef of clouds and lightning raced across the skies from the sea. … My hands were shaking, and my mind wasn’t far behind. I looked up and saw the storm spilling like rivers of blackened blood from the clouds, blotting out the moon and covering the roofs of the city in darkness. I tried to speed up, but I was consumed with fear and walked with leaden feet, chased by the rain. I took refuge under the canopy of a newspaper kiosk, trying to collect my thoughts and decide what to do next. A clap of thunder roared close by, and I felt the ground shake under my feet. …

On the flooding pavements the streetlamps blinked, then went out like candles snuffed by the wind. There wasn’t a soul to be seen in the streets, and the darkness of the blackout spread with a fetid smell that rose from the sewers. The night became opaque, impenetrable, as the rain folded the city in its shroud.

Using strong verbs and adjectives will help you craft setting descriptions that are masterful. Every word counts. To borrow unfaithfully from Animal Farm: All words are created equal, but some words are more equal than others. Some words are plain boring, and others take our breath away.

And, of course, it’s not just the words but how they are used—a paintbrush in the hands of a master will create something quite different from the same brush in the hands of a toddler.

Throwing words and imagery around in a random, thoughtless way may present a tableau that resembles a Jackson Pollack modern art piece. It may be colorful but there’s no identifiable picture that emerges, no matter how long you stare at it. We don’t want readers scratching their heads trying to figure out what the mood of the scene is meant to convey.

Let’s take a look at a passage from James Lee Burke’s Bitteroot:

Early the next morning the air was unseasonably cold and a milk-white fog blew off the river and hung as thick as wet cotton on the two-acre tank behind my barn. As I walked along the levee I could hear bass flopping out in the fog. I stood in the weeds and cast a Rapala between two flooded willow trees, heard it hit the water, then began retrieving it toward me. The sun looking like a glowing red spark behind the gray silhouette of the barn.

Rain was moving out of the south, dimming the fields in the distance, clicking now on the asphalt county road at the foot of his property. … The air was dense and cool, like air from a cave, and the pine trees shook in the wind and scattered pine needles across the top of Kyle’s trailer.

A bolt of lightning crashed in a field across the road and illuminated the trees, burning all the shadows from the clearing, and Kyle saw the tinkling sound was only the wind playing tricks on him. A solitary drop of water struck his head, hard, like a marble, and he finished gathering the arrow shafts from the hay bale.

The weather in Burke’s novels is tactile, personal, evident, front and center. And this isn’t because the novels I’ve read of his are set in Montana, which is all about “big sky” and nature. Burke describes interiors just as deliciously as he describes exteriors.

Look at how Burke relied predominantly on visuals. But those bits of sound added the perfect texture to those sights. Bass flopping and rain clicking and tinkling (can you hear those?) and lightning crashing. The shift in focus to a single drop of water hitting his head hard, like a marble, makes the weather personal and tactile.

This is all about caring. Caring that every sentence uses the best words in a concise and specific way. You don’t need a lot of words to describe setting in a powerful way. Remember: mood has to reflect and inform the character in that moment of time.

Don’t discount the power of weather in your settings. Make weather an important element in your characters’ lives, just as it is in your life. And spend time choosing just the right words and imagery to reflect and inform your character’s mood. Your writing will soar to new heights when you do.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, check out C. S. Lakin’s new online course on how to craft powerful settings. Enroll before October 24 and get 30% off with coupon code EARLYBIRD.

October 13, 2022

Why It’s Better to Write About Money, Not for Money

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Photo by Annie Spratt on UnsplashToday’s post is by author Catherine Baab-Muguira (@CatBaabMuguira).

My neighbor and I were slouched on my couch, watching The Holiday and eating under-baked brownies from the pan, when the email came that changed my life.

For seven years, on and off, I’d been pitching national publications, hoping they would accept my essays and journalism. Local publications gave me no trouble. I enjoyed great relationships with my small city’s newspapers, websites and magazines, but I never could get the far-flung big guys to take a pitch. Instead, the fancy editors always ignored my emails. I couldn’t even get rejected.

Understanding the problem did not help. There’s an ancient catch-22 that says: You can’t write for large, popular, national publications until you’ve written for large, popular, national publications. It’s like when you’re applying for your first job. You need the job to get experience, but can’t get the job without experience.

I could see no way out of the bind, so I just kept on pitching into the void, growing more disappointed and bitter by the week. If only I’d gone to an Ivy League school, or had the cash to move to New York after college! If only I’d had well-connected alcoholic socialites for parents! I was sure my writing life would be different. Easier. Cooler. The opposite of desperate and doomed.

And then, in 2015, seven years into my pitching efforts, I dashed off an essay for a tiny personal-finance website about, of all things, my mortgage payment. My husband and I had recently bought a modest house in our hometown, and the monthly payments were low, running to just $624, or 58 percent less than what was then the median U.S. mortgage payment of $1,477.

My essay’s title was simple, classic clickbait: “Tradeoff: The True Story of My $624 Mortgage Payment.”The day it came out, Yahoo! picked up and ran the story, too, which I learned when coworkers began forwarding me the link. And that night, while my neighbor and I were complaining about Kate Winslet getting stuck with Jack Black, my inbox pinged. A senior editor at New York Magazine had emailed me. She’d seen the mortgage piece.

“Pitch me,” she said.

Wordlessly, I handed over my phone so my friend could read the email, and the next moment, we were flying off the couch, stomping and whooping like football players doing an endzone dance.

The next morning, I shot the editor a pitch—for another internet-friendly essay about money because, by this point, I’d gotten religion. She accepted the idea, and about a month later, I got my first big byline. Then I used that byline to get my next byline, to get my next byline, until I had enough bylines that I was able to sell my first book to a Big Five publisher. And to think it all started with an essay about my mortgage. Oh, the glamour of it all.

The internet has changed since 2015, but the great human interests have not.What allures people, what do they want to read about? Money, sex and death, but especially money. So when you write about money, you put the odds of a breakout on your side. It was true centuries ago and it’s still true now.

To mention just a few examples:

The very first line of Pride & Prejudice concerns a “large fortune.”Anna Karenina opens with a scene of a married couple fighting over money for their children’s coats.Madame Bovary is littered with itemized bills for Emma’s dresses, stockings, ribbons, et al.In one of the most magical moments of the Great Gatsby, we’re told Daisy Buchanan’s voice is “full of money—that was the inexhaustible charm that rose and fell in it, the jingle of it, the cymbals’ song of it.”No one has ever written more beautifully about money than Fitzgerald, yet we could keep naming examples all day: Kevin Kwan’s Crazy Rich Asians. Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt, or any of the innumerable memoirs that delve into experiences of extreme poverty. Also, any of the gazillion romance novels with “billionaire” in the title. Any of Poe’s many stories about extreme wealth. All of George Orwell’s early work. Etc, etc.

Money makes a story extra sticky, and this principle applies to fiction and nonfiction, great literature and clickbait.

Nowadays I evangelize to fellow writers: Write about money.And even more specifically—if you want to get an email opened, a pitch accepted, or your book picked off the shelf, try using a highly specific number in the subject line or the title. Try referencing money somehow. Detail your characters’ economic circumstances, or detail your own. It could help you get noticed. It could lead to the breakout you’ve been hoping for.

Of course there’s a big old bummer lurking just beneath this rule. Writing about money is a great strategy. Writing for money isn’t, and not because of some 20th-century preoccupation with “selling out.”

Genuine creative writing—the kind that’s done to fulfill some deeply personal vision—rarely turns out to be a high-earning proposition. It’s much more likely to cause financial problems than solve them. All those conferences, classes and editing services don’t come cheap. It can take a long time to get published, and there’s no guarantee you’ll ever get there. To call this a tough business is understatement.

There are vivid exceptions: So-and-so’s airport thriller, movie deal, indie publishing career, or MacArthur genius grant. But they just prove the rule. If creative writing offered reliable payouts, even more people would be doing it.

Even for those who do get published, rates tend to skew low. Freelance writing is notoriously badly paid, and only in rare instances do first-time authors receive six-figure book advances. I once calculated that writing my book earned me just $6.86 per hour—less than minimum wage. I could’ve earned more folding burritos or handing out Kohl’s Cash.

Honestly, though, it’s fine. Writing’s rewards lie elsewhere.For many of us, to become a writer is to realize a childhood dream, actualizing at last our nerdiest, most-earnest selves. It’s to keep a promise to a child, an earlier version of you who was tiny and vulnerable, stranded in a harsh world, utterly baffled, hungry, thirsty, lost, needing to pee but unable to speak the language—and who, in a very real way, still exists inside you. (Or is it just me?)

In the same way, writing can give you a sense of identity. It can provide a way of being who you are now and a way of becoming who you are becoming, and I don’t care how woo that sounds because it’s true. Writing can also be a first-class ticket to flow state, helping you reap intense psychological benefits that lift you out of depression and anxiety, while deep absorption in a subject can help you transcend your humdrum, dirty-laundry circumstances. The work is a kind of relief, and how often can you say that?

Finally, though writing can be a lonely pursuit, when you make friends with other writers, you may discover a deep core of mutual understanding and, even better, shared gallows humor: friends who understand you, friends whom you understand. People to go to happy hour with and to complain with. There’s nothing better.

Money? It may never come. It probably won’t. But considering everything else we get from writing, it’s worthwhile—a pursuit worth pursuing.

October 12, 2022

You Have a Great Idea for a Story. Where Do You Start?

Photo by cottonbro

Photo by cottonbroToday’s post is excerpted from Good Naked: How to Write More, Write Better, and Be Happier by Joni B. Cole (@JoniBCole).

You have a Great Idea for a story. You are so infatuated with this Great Idea that you gush to your friends and fellow writers, “I’m going to write a book about [insert your Great Idea here]!” Your Great Idea takes up residence in your psyche. It settles in, as entitled and undisciplined as lesser royalty. Weeks pass, then months, but nothing gets written. Your Great Idea begins to pace the shag carpet of your mind.

“What’s the holdup, hon?” your Great Idea asks. “These shoes are killing me.”

“I just need a little more time,” you tell your Great Idea. “I’m not sure how to get started.”

Life continues, crowding the inside of your head with more experiences, more people, more memories, more distractions: Ticks! When’s the last time I checked myself for ticks? Still, even with so much going on in your world, you keep revisiting your Great Idea in your mind. By now, its shoes are off. Its feet rest on the coffee table of your consciousness, next to a highball sweating on the once burnished cherry tabletop. You think, Why can’t it use a coaster?

“I thought you loved me,” your Great Idea nags. “I thought you were all, like, I want to spend time with you. You mean so much to me. I want us to have a future together.”

And your Great Idea is right. You did want that. You still want that. You loved your Great Idea then and you love it now, only now it is starting to feel more like a love-hate relationship because you cannot think about your Great Idea without feeling guilty. I’m just too busy to sit down and write, you tell yourself, citing your dependents, the crumbs in your bread drawer, your commitment to world peace.

Deep down, however, you know it is not family, or work, or even your ideal of planetary nonviolence that is keeping you away from your desk. This editorial paralysis is all about your fear of making a wrong first move. This is the real reason you cannot commit to your Great Idea.

Where to start? Where to start?

If this scenario sounds at all familiar, you do indeed have a problem. Only it is not the problem you think you have. When launching a novel or memoir—or any creative work for that matter—the issue isn’t that you don’t have a clue where your story should start; the issue is that you think you should have a clue, even before you start writing.

If you are like most writers, and by most writers I mean all but four, the perfect opening for your story will never manifest in your mind. Yes, there is always that one author we have all encountered at a book signing or writing conference who points to his receding hairline and explains to his rapt audience, “I write it all up here, and then just put it down on the page.”

We can admire this author and wish we were like him, perhaps with more hair, but know that this fellow is the exception to the rule, and perhaps not to be completely trusted. Typically, the creative process needs more than a head to sort itself out. Thus, thinking you need to figure out chapter one (or even more distressing, first figure out your preface, then your introduction, and then chapter one) before you start typing away will only succeed in eating up a lot of time, and will make you feel constipated and grouchy.

The good news, however, is that these bad feelings are also what push a lot of people past their reluctance to join a writing workshop, which is at least one productive thing that can come from such misguided thinking. I know my classes certainly attract people struggling with this issue, including Lynne, a professional feature writer who knows her way around a page. Regardless, when Lynne got an idea for a mystery novel about a woman whose teenaged son goes missing after soccer practice, she spent months feeling stuck because she didn’t know where to begin her narrative.

“I have a sense of what I want to happen, but I just can’t figure out the first scene,” Lynne told our group.

“So forget about the first scene,” I advised. “Write any scene you feel fairly certain belongs somewhere in the story. Even better, write the rescue scene where the missing son is discovered alive and well!” I offered this last suggestion because I have little tolerance for authors who kill off children or pets, even if these plot points are in service to the story. Having worked with so many aspiring authors like Lynne—who have gone on to complete powerful stories by following this same advice to start anywhere—I knew this was excellent counsel, from my perspective a no-brainer. But maybe because it is a no-brainer, literally, in that we need to temporarily disengage our brains from its insistence on first things first, this concept is often met with foot stomping.

But I can’t just start anywhere. It feels so loosey-goosey!

I will assume you are thinking this because most people respond to this advice in a similar fashion, at least until they try it. As writers, we may be described as creative types, but that does not mean we don’t like feeling in control, or crave the comfort of structure and predictability as much as the next guy. Human nature does not step easily into the unknown, especially if we think it will cause us more work.

But my book needs a proper beginning!

What book? At the moment, all you have is a feral pig. Perhaps that last comment was unnecessarily harsh, but so many writers tend to try to reduce the creative process to a linear equation because they think that is the proper way to proceed. Listen Great Idea, you are not leaving this head until you tell me where to start! Would that you and your Great Idea could cuddle up in your consciousness together, figure it all out, and then step out onto the page accompanied by a herald of Hallelujahs. No rings on the tabletop. No mess. But messes, you might want to remind yourself, can be fun. They can be the stuff of inspiration. And the reality is, even if the “perfect” opening for your Great Idea does present itself in your mind, it is just as likely to be a false start. By this, I mean that, more often than not, where you think you should start your narrative will actually end up being better suited as backstory embedded in a later chapter. Just sayin’.

Where to start? Where to start?

Shush. Of course, in the end, your narrative needs to open with exactly the right scene, and by exactly the right scene I mean exactly the right scene. For that matter, all the scenes, from the first to the last, must contribute to a flow that establishes not just a chronology but a causality that drives the plot forward and makes readers curious, if not frantic, to know what happens next. Still, none of that needs to be figured out at the front end of writing. And the future structure of your manuscript will not suffer one iota by not writing it from the beginning to the end. In fact, quite the opposite. Starting the creative process anywhere allows you to jump right into a scene, any scene, that demands your attention.

But I don’t want to waste time writing a jumble of scenes without any sense of order.

I imagine this is yet another concern on your mind, which I will counter by asking you this question: How much time have you already wasted not getting any of your Great Idea down on paper? If your answer is, say, six minutes or longer, then I would argue that writing something that might fall somewhere, anywhere, in your story is better than not writing your beginning, which may not even end up being your beginning.

But, but, but …

Shush! I’m sorry to keep shushing you because I know from personal experience how annoying that can be, but you need to quiet your mind and listen to the following good news. I have come up with the perfect writing exercise for people in your predicament! In fact, if you use this prompt to begin your work, I am certain that you will launch your story in the best way possible, and your relationship with your Great Idea will be restored to what it was before both of you did things that you would rather forget.

Amazon / Bookshop

Amazon / BookshopBut …

How do I know this is the perfect exercise to launch your particular Great Idea? I know because it is the same for every writer who has ever felt stuck before even getting started. When it comes to beginnings, saying goodbye is as good a way as any to send us off on our merry way.

“Goodbye. I’ll miss you.” There you go. That is the perfect writing prompt for you, guaranteed. “Goodbye, I’ll miss you.” Just put those words on the page, then keep writing, capturing whatever flows through your fingertips to your keyboard or pen. Write without judgment, or second-guessing, or thinking. Write without worrying about beginnings, middles, or endings. Write now. Right now.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out the revised and expanded edition of Joni B. Cole’s book for writers, Good Naked.

October 11, 2022

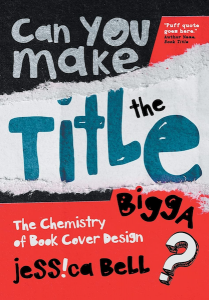

The Key Elements of Eye-Catching Book Cover Design

Photo by Andrea Piacquadio

Photo by Andrea PiacquadioToday’s post is an excerpt from the book Can You Make the Title Bigga?: The Chemistry of Book Cover Design by Jessica Bell (@IamJessicaBell).

The very first thing I’d like to mention is…

S p a c e

Not the book cover cluttered with galaxies of planets, stars and moons, but the one where you can walk into a room and not trip over the dog. A book cover with space allows the imagery and text to breathe. Utilizing space wisely draws attention to the elements that you want potential readers to focus on.

Here is a nonfiction example.

Here is an example of fiction.

And here is an example of poetry in which I’ve taken an extreme perspective. Be sure to take a close look!

As you can see in the first two examples, there is ample space for the text to breathe, and the imagery is clear and telling. You know exactly what you’re going to get with these books, and your eye is not wandering. The space on the poetry cover, however, is used as reader bait. It’s saying, “Hey, can you read the title from there? Probably not. You’d better zoom in and check this out.” It creates a little bit of mystery and intrigue.

Avoid clutterAs I’m sure you’ve noticed in the previous examples, it’s important not to clutter a cover. If there are too many elements fighting for attention, there is no focal point, and therefore nothing to attract the eye.

However, if you have a talented cover designer, it’s possible that strategic cluttering can work. Have a look at this as an example. I’m very proud of this one.

Here, I’ve pretty much filled in all available space with either text or illustration. But it’s still easy to read and understand what’s going on. This is due to the use of color. The various colors allow us to distinguish between the elements, so I’ve been able to get away with this kind of “clutter.”

But please don’t try to fit all your story elements in, like in this example. Not mine!

Color

ColorToo many different colors on a cover can be confusing for the eye or cause a cluttering effect. This is because colors help separate the elements on the cover, and draw attention to specific elements on a cover. I typically try not to exceed three main colors and two accent colors. In the following three covers, I’ve kept to very few for maximum effect.

Of course, this strategy doesn’t work for every genre or idea (especially when using photography), but it’s good to keep in mind that too many colors may push readers away.

The following color chart shows combinations that are a good place to start if you’re trying to decide on a color scheme for your cover. If you want to make more advanced selections, check out Adobe’s color wheel online.

Similarly, color plays a huge role in how a cover affects us emotionally. I find that I gravitate toward purple and turquoise for their sense of calm, blues/greens with yellows/oranges/reds for their air of confidence and reliability, and contrasty color combos like red, black and yellow/white, which not only draw the eye, but really do scream, “Hey, I know what I’m talkin’ about!”

Take a look at the following chart for a list of common colors and their meanings.

Amazon • Bookshop

Amazon • BookshopIf you’re familiar with advertising tactics, you’ll know that color is used strategically in product packaging and business logos. For a more robust list with deeper explanations, just search online for “color symbolism” and the color you are looking for.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out Can You Make the Title Bigga?: The Chemistry of Book Cover Design by Jessica Bell.

October 6, 2022

When Should Writers Stand Their Ground Versus Defer to an Editor?

Photo by Ketut Subiyanto

Photo by Ketut SubiyantoWelcome to the very first installment of a new column at this site, Ask the Editor!

Ask the Editor is a column for your questions about the editing process and editors themselves. It’s a place to bring your conundrums and dilemmas and mixed feelings, no matter how big or small. Want to be considered? Learn more and submit your question.

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by 805 Writers Conference. The 805 Writers Conference delivers the information you need to succeed in publishing—all of the tools, skills, and resources—available virtually and in person—November 5 & 6. Conference sessions, specialty workshops, and a book expo featuring 50+ authors. Join us at the beach!

QuestionI write dark fantasy stories for adults that explore survival after sexual trauma and war. My work focuses on the aftermath of sexual violence and the way my protagonists stubbornly live well after the unthinkable. There are no on-page depictions of SA in my work. Naturally, edits are a must and I am very receptive to feedback (I’m in journalism, so tough deletions and red pens are familiar friends of mine).

As a debut writer who was previously represented by a literary agent, I made structural, style, and developmental edits to my manuscript on the guidance of my agent. I wanted to ask how an agent’s edits differ from those of a publishing house’s editor?

Since I work as a newspaper editor, I often have strong opinions about what accessible writing looks like. Should I stand my ground with regard to edits (professionally, of course) or is it best for unpublished authors to trust the expertise of their agents and editors? Especially when it comes to issues such as sexual violence, racism, or war, I am very firm that my work shouldn’t be edited purely for the sake of “good taste” or “finding the book a home” in the commercial market. How can a debut writer navigate this challenge?

—Writer Who Writes Entire War Scenes But Is Afraid to Even Politely Disagree

Dear Polite War-Scene Writer:These are three great, intertwining questions, and the answers to all of them depend on a fourth: Do you want to traditionally publish?

For authors who self-publish, there are no gatekeepers and no intermediaries between their vision and the audience’s eyeballs. There’s also no one to save us from ourselves when we’re so wedded to our vision that we can’t see the red flags waving.

But questioning agent-editor-author relationships sounds like you do want to traditionally publish. Part of that process is finding an agent you trust and believe in, who trusts and believes in you, who will then negotiate a publishing deal that will support your vision while getting your book to as many eyeballs as possible.

A “good” agent—one who is the right partner to help you make your best book and sell it—may or may not be an editorial agent (that is, an agent who will also edit your work). The best publisher to support and distribute your book may ask for hundreds of revisions, or none. In both cases, sometimes the first round of revision requests come from the agent or editor’s assistant, to fix larger challenges before the agent or editor wades in for a last pass. What’s important is that you, the author, believe this partnership will help you. Perhaps you’ve admired books from this press or agency. Perhaps they said something profound in an interview. Or you loved their ideas on the pre-signing phone call. But whatever it was, you’re on board the We Can Do This Together Express, destination Bookshelves.

You should, of course, fundamentally agree with your partners’ advice, even if you want to quibble on the details. If your agent or publisher’s idea of “good taste” doesn’t line up with yours, they aren’t the right partners. Yes, there will be suggested edits where you say, “I really think it needs to be this way.” Very often, the problem the agent or publisher has identified isn’t actually at that exact place in the text. Sometimes the real issue is that a scene or a moment hasn’t been set up well, and the fix is adding or changing information in the pages before.

Writing about trauma survivors in itself brings trauma to the reader, who will feel personal trauma more or less depending on their own history. As the author, your writing must implicitly both warn and reassure the reader from page one: This is going to be well-written and worth reading. I’m going to show you some violence, but it won’t be gratuitous, and you can trust me that those scenes will be emotionally powerful rather than titillating.

Which brings us to “finding the book a home [in the commercial market].” If you don’t want to make your artistic product appeal to readers and be purchased by them, traditional publishing may not be for you. A major part of an agent’s job is to sell our books. It is the only way they are paid for their services. Taking an agent’s creative advice and making our manuscript something they are thrilled to share with publishers, confident that someone will recognize our greatness with cash, is the way we recompense them.

Right now, it sounds like your compelling belief—despite the red-pen love—is that your work is already finished and as good as you can make it. Or perhaps you haven’t yet had the editorial advice that rings the tiny bell in your heart of, “Yeah, I kinda knew that wasn’t working…” But the best partners to bring your book into the world aren’t coming to squash your dreams—they’re rolling up their sleeves to help your vision be as beautiful to the reader as it is to the writer.

May your red pen flow smoothly!

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by 805 Writers Conference. The 805 Writers Conference delivers the information you need to succeed in publishing—all of the tools, skills, and resources—available virtually and in person—November 5 & 6. Conference sessions, specialty workshops, and a book expo featuring 50+ authors. Join us at the beach!

October 5, 2022

Motivation Doesn’t Finish Books

Photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash

Photo by Nick Fewings on UnsplashToday’s post is by Allison K Williams (@GuerillaMemoir). Join her for the three-part webinar series Memoir Bootcamp, Oct. 19–Nov. 2, 2022.

A writer I work with asked, Should I take another class? Or should I just get down to business and crank out the rest of my memoir?

She certainly could get down to business—she’s smart, thoughtful, and a solid writer who’s taken plenty of workshops and gotten plenty of peer feedback. But will she?

I’ve heard the same questions from other writers, and I’ve asked them of myself. We think we’re asking about yet another class, “Do I need to learn more?” (Yes, forever.) But the real question is “Do I need an external structure to write?”

Finishing your book isn’t actually about motivation. Sure, you can want to spend the time writing, you can type with intensity, you can burn with the need to tell your story. But motivation isn’t enough.

Beyond the desire to write a book, we’re subject to our calendars—work, volunteering, fitness, housework, gardening, caring for spouses, parents, children and/or pets. Many of us want—or even schedule—time to write, but we shove the planned hour aside when something urgent (or “urgent”) arises. I am the number-one poster child for I Was Going to Work on My Book, But Then a Client Needed Me Syndrome.

Paying for a class or workshop, or even just being accountable to a regular writing group, knowing others are waiting for you, feels like a firm commitment in a way that’s very hard to honor with motivation alone. Our families and friends are more likely to treat an outside commitment with respect, too. “I’m sorry, I can’t, I have class,” is easier to accept—and easier to deliver—than “I’m sorry, I can’t, I’m planning to sit at my desk and maybe accomplish some writing but last time I got stuck on Facebook so who knows?”

Here are the obstacles most writers face that motivation may not fix.

A sense of overwhelmSitting down to a blank page, or even a multi-page outline, can feel like standing outside the forbidden castle, looking for the door in. My ideas are beautiful! My story is powerful and compelling! So…um…where do I start?

The right class can help you identify those doors—and teach you to build your own habits, writing practices and exercises to get the words flowing when you’re stuck outside the wall.

You can’t picture the finish lineWhere does the story end? Does addiction resolve with recovery, or with restitution and restoration? Grief famously never ends—so where’s the last page of the memoir? What if the main antagonist reformed before you got to the last chapter, and now the relationship with that character is completely different than the one already written?

Sharing ideas and brainstorming with fellow writers and your teachers brings solutions to story problems. Particularly with memoir, some of my greatest writing breakthroughs have come from a workshop leader or participant saying, “But it seems like this story is really about X, right?” A trusted outside eye can show me gaps I’ve overlooked in the dramatic arc, how I’m not treating a character fairly, or where my words just aren’t clear, and those tiny breakthroughs bring more words to the page, much more quickly.

Your audience is fuzzyWho needs your words, and where are they? Can you reach them through public speaking, or publishing essays, or being present on social media? Will you need a platform at all, or will the story and writing be enough?

Many writers have a vague idea they’d like to be traditionally published for the prestige, or they’d rather self-publish because it’s faster, but making the right choice demands a clear sense of who you’re writing for. A writing workshop is a great place to find out what happens on each of those paths—and think through whether you’re the right person to take those steps.

Difficulty finishing a manuscript is common. It’s common to attribute our trouble to procrastination, time-wasting, or just plain laziness. But it’s not a personal failing to feel obligations to the people you care about, your career, and your life. It’s not a character fault to have a hard time seeing the goal or be stuck in uncertainty about how to get there.

Can you get down to business and finish your book all by yourself?Sure! Many writers do. But even more of them have support systems, deadlines, teachers, exercises, instructions and help. If a workshop is out of your budget, grab a couple of other writers and start a regular meeting, with deadlines and goals. Consider a publishing or writing craft question every meeting, each researching and discussing what you find. Develop a rubric to critique each other’s work as professionally as possible. It’s not the teacher’s prestige that will finish your book—it’s creating a structure for showing up.

You might think to yourself that—surely, as a motivated, list-making, hardworking person—I don’t need other people to help me finish, and I don’t need to blow money on another class! Yet every time I sign up to show up with others, I write more. I write faster. And I write better. Assignments, deadlines and yes, the desire to show off, make me work regardless of my immediate level of motivation. (I think of my drive to avoid embarrassment by completing writing as “shame-couragement.”)

If your book is ticking along, great! Keep doing what you’re doing. But if you’re stuck, chances are it’s not lack of motivation holding you back. Instead of shoving your chair back and feeling discouragement reverberate through your body, identify the problem: lack of scheduled time, difficulty seeing the next step, or problems envisioning the finish line. Then get to class.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us Oct. 19–Nov. 2, 2022 for the three-part webinar series Memoir Bootcamp.

October 4, 2022

Write Small for a Bigger Impact

Photo by Nubia Navarro on Pexels

Photo by Nubia Navarro on PexelsToday’s post is by editor and author Joe Ponepinto (@JoePonepinto).

Writers have to recognize and accept an essential artistic paradox that the more specific and individual things become, the more universal they feel.

That’s from an essay written by Richard Russo a couple of decades ago. I’ve been thinking about it a lot lately as I read stories in the submission queue, especially those by newer writers. I can tell they want to say something profound in their fiction. Why not? If you can write something that makes readers take notice, that makes them sit up from their reading and say, “Wow, that’s so true,” it could mean publishing success is not far off.

But many writers go about it the wrong way. Since they want to say something big and universal, they tend to write their stories in the universal. They create settings and characters that adopt the traits of universal subjects, which is to say they become flat and generalized, homogenized into composites. Sometimes the characters in such stories seem written to represent a particular side in a philosophical or social discussion. In reality, though, those “big” topics are so complex and nuanced that they can’t be described efficiently and adequately enough in a short story. The result then is a narrative filled with characters and scenes that don’t connect with readers, and a message that sounds artificial and predictable.

So how can writing about something small illustrate the great truth you have in mind?

First, stop worrying about conveying “great truths.” If there is a truth in your story it will become apparent in a subtle way, allowing the reader to discover it instead of being lectured about it. Better to concern yourself with the smaller truths about human nature, which are just as universal, and often far more satisfying to readers because they are easier to identify with. Let’s create an example.

Imagine a reader in New York City, reading about a character in a rural setting. Their lifestyles, interests, economics are vastly different. But could there be some common ground? That rural guy feels the same way about his relationships and problems as the reader in New York does, whatever the nature of the relationships and problems may be. Describing the specific details of his existence brings those feelings to the surface, provided they are described in such a way as to connect the details to character desire and motivation.

Here’s an example from Breece Pancake’s “In the Dry”:

The front yard’s shade is crowded with cars, and yells and giggles drift out to him from the back. A sociable, he knows, the Gerlock whoop-dee-doo, but a strangeness stops him. Something is different. In the field beside the yard, a sin crop grows—half an acre of tobacco standing head-high, ready to strip. So George Gerlock’s notions have changed and have turned to the bright yellow leaves that bring top dollar. Ottie grins, takes out a Pall Mall, lets the warm smoke settle him, and minces a string of loose burley between his teeth. A clang of horseshoes comes from out back. He weaves his way through all the cars, big eight-grand jobs, and walks up mossy sandstone steps to the door.

Inside smells of ages and chicken fried in deep fat and he smiles to think of all his truckstop pie and coffee. In the kitchen, Sheila and her mother work at the stove, but they stop of a sudden. They look at him, and he stands still.

I can’t begin to tell you how foreign every detail of that passage sounds at first. I’ve never been to that part of the country, never seen a field of tobacco in person, never attended a whoop-dee-doo. (I did, however, play horseshoes with my grandfather when I was a kid.) And yet I’m right there with Ottie as he takes it in. These things are as natural and important to him as my neighborhood progressive dinners are to me, and that’s a shared experience I can identify with and learn from. Notice the vernacular: a sociable, sin crop, eight-grand jobs. Each of those terms isn’t so much a description as a way of thinking about the object—the gathering is a “sociable,” tobacco is a “sin crop”—and from that we develop an understanding of Ottie’s and his relatives’ values. I’ve never been to this place, but I can see it, and see myself in it, even though Pancake used far fewer words than most emerging writers would have.

And there’s the magic—by expressing the world in specific terms that are natural to the character, the writer creates a sense of identity not with what the character sees, but with what it means, and the fact that we all have a similar need to find value in our ways of living begins to bridge the divides of place and status and race and sexual orientation and our other differences. Offering those details in generalized terms that are disconnected from character doesn’t do that. That’s the real great truth of fiction—it has the potential to connect us in a way that modern media, social and otherwise, doesn’t, because it speaks to the heart of what matters, not the exterior.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile