Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 52

February 23, 2023

How to Minimize Hurt Feelings When Writing Your Memoir

Photo by cottonbro studio

Photo by cottonbro studioToday’s post is by Allison K Williams (@GuerillaMemoir). Join her on Feb. 27 for the online class Writing Memoir Without Fear.

You want to share your truth.

You also want to avoid hurting parents, children, exes—or being further hurt by them.

How can memoirists handle the paradox? The more broadly your story spreads, the more people your words help … and the more likely it is that your book will be seen by someone who is hurt by what you wrote. Your ex might threaten your custody. Your kids might stop talking to you. Your mom might say she’s “not mad, just disappointed.”

We’ve all heard the Anne Lamott quote, “If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.”

But not everyone feels confident laying out the whole truth.

What if I hurt someone I love?

What if I embarrass a friend?

What if my ex doesn’t like what I wrote and sues me? Can they even do that?

Your story matters, and you get to write it the way you remember. It’s called a memoir, not a “comprehensive review of all facts.” But you can take steps throughout your writing and publishing process to minimize fallout and family strife.

First, don’t borrow trouble.Write the book. Write the whole book. You may discover as you write that your story isn’t actually about the abusive ex or the troubled child. Maybe you end up with three scenes that show why you went to medical school, and the one where your dad says you’re not smart enough to become a doctor isn’t the strongest one. It doesn’t matter if he golfs with attorneys, you’re focusing on better scenes.

Show your antagonists’ behavior and their effects.You don’t have to call Grandpa an alcoholic if you show his collection of empty, hidden brandy bottles. Describing what actually happened without accusatory words will show the reader who they are. And your writing will be stronger for making the reader put the clues together—just like you had to when the situation was happening.

Very few of the people who hurt us woke up every morning, yawned, stretched, and said, “I can’t wait to start oppressing the narrator today!” Show why they behaved the way they did. It’s not excusing their behavior to give the context of cultural or family issues, addictions, or their own bad treatment they’ve been doomed to repeat.

Seek their perspective if you can.If you’ve gone no-contact, ask other family members what they remember. When you do, pretend you’re making a documentary. Instead of asking, “Mom, why did you make me eat lead paint chips as a child?” start with, “Tell me about how you fed the family while you and Dad were both out of work. What were our meals like?” Even if you’ve got to cry in your car after the interview, you’ll get better, deeper, more interesting details if you start from neutral.

Wait to tell people what you’ve written.Wait until you’ve got the deal—whether that’s a Big-Five publisher or a strong self-publishing plan—before telling anyone in the book what you’ve written. Don’t get everyone riled up if it turns out this is your “practice” book. Or your editor says, “Let’s make it self-help and take out all those bits about your ex.”

When you do have a publication date, give others awareness of it rather than asking permission. You’re not looking for a gold star, you’re letting them know, “I’ve written my memories, and I’m sure your story is a little different.” And stay real—how many of your relatives will actually seek out, purchase, and read your book? Generally, your family is not your audience anyway.

Rehearse how you’ll respond to questions you’re dreading.Tell your sibling, “Isn’t it fascinating how we can grow up in the same family and have such different experiences? I’d love to read your version of the story someday.”

Tell your parents, “You don’t have to read it, but I hope you’ll support me sorting out my own experiences on paper.” It’s not the first time you’ve hurt your parents’ feelings (we were all 13 once!) and it’s probably not going to be the last.

But what if someone sues?In most American jurisdictions, no one can sign away their right to sue. Anyone who wants to can file paperwork and demand their day in court. But suing is almost always an empty threat. Finding a sympathetic attorney and a judge who won’t laugh them out of the room is time-consuming and expensive. Then they must prove:

You lied.You lied on purpose.Your lies damaged them in terms of hard cash or public reputation.“I got my feelings hurt by a book,” isn’t a winnable case. Our best protection is that most of us aren’t worth suing. We don’t have enough assets for a long-shot winner to take. Generally, if you have enough money to be worth suing, you can already afford your own excellent lawyer to tell you all this. If you don’t have that kind of cash, it’s almost never worth the time and money for the plaintiff or their attorney.

Still, there is no memoir publishing without penalties.Someone you wrote kindly about will be unhappy anyway. Someone you didn’t even mention will be mad you left them out. People will remember things differently. Your mom will be upset you changed her name to “Mindy.” Your kid will be embarrassed you talked about changing their diaper.

You can’t stop people from feeling their feelings and having their own memories, and you will never finish your book if you are trying to please them more than you are trying to write your story.

A memoir is, by definition, one person’s memory. Be honest with yourself, be kind when you can be, and put in a disclaimer about memory at the beginning. Write your best work and brace yourself—sharing your journey is worth it.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Feb. 27 for the online class Writing Memoir Without Fear.

February 22, 2023

How Authors Can Build Relationships with Independent Bookstores

Photo by Ksenia Chernaya

Photo by Ksenia ChernayaThis article first appeared in my paid newsletter, The Hot Sheet. It touches on issues of literary citizenship, which is the focus of my upcoming class on March 1.

If you want your book to be carried by independent bookstores, the most important thing to remember is that every store is different; you need to carefully research each store before you make an approach.

That was the key takeaway from an Authors Guild panel hosted in fall 2022 on how to build a relationship with bookstores. The panel included two Georgia-based booksellers and one children’s author who has done incredibly well with bookstore events and promotion. (Note: Advice offered here also applies to your local Barnes & Noble store, where the staff makes buying and stocking decisions.)

Authors who want to focus on bookstore sales should begin by building a relationship with their local or regional bookseller far in advance. Author Mayra Cuevas started her relationship-building six years before she even had a book contract. She attended store events and book launches and participated in book clubs. She also formed a group of local kid lit authors who would gather multiple times per year and hold meetings in area bookstores. “That really helped me solidify a lot of relationships with booksellers early on,” she said. “By the time [my first book] came out … we already knew each other for years.”

Justin Colussy-Estes, store manager for Little Shop of Stories (one of the largest independent children’s bookstores in the country), agreed with the wisdom of this strategy. “Establishing an author community and connecting to that was very powerful,” he said. “There is an ecosystem of authors and bookstores. So being a part of that I think is important.”

Kim McNamara, owner of Read It Again, a new and used family bookstore, said that if authors spend money in their local store, then they will be more likely to sell your book. That said, it’s important to understand the store, its customer base, and what types of books the store carries. Despite the fact his store focuses on children’s literature, Colussy-Estes is often approached by authors of adult work, but it’s unusual for his store to stock adult books, even from local authors.

What if you don’t have years to develop a relationship—what if your book is coming out very soon? Colussy-Estes said you can support your local store by entering into a pre-order campaign partnership. This means approaching a local store, telling them when your book is releasing, and asking if you can direct people to their store exclusively for pre-orders in your publicity materials. “The store doesn’t have to do anything except order the amount people want,” he said. You can also offer the people who pre-order from your preferred store an incentive: You can go in and sign the books before they ship or before customers pick up their copies. And you can give the store a bit of swag to include with the book. Just make sure the store knows your ideas or plans for any extras so they can plan accordingly or suggest what would work best.

Getting your book into stores located far from where you live may not work out unless you can make a strong case. McNamara advocated for sticking with your own state or local community. “You get well known in your area with your people, and your name will grow organically. This is a very organic process.” But if you decide to try anyway, Colussy-Estes said you must be intentional about who you approach and your reason for approaching them. For example, perhaps you used to live in that area, you have family in that area, or you’re pitching a niche book to a store that specializes in that niche. Or maybe your book is set in that region or you have evidence your book sells really well in a specific geographic area. Tell the store directly why the book will be in demand by or of interest to its local customers.

A good way to meet a lot of booksellers in your area is to attend a regional bookseller conference. (Here is a list of regional bookselling associations.) Such conferences tend to offer “author speed dating,” where booksellers sit at a table and authors move from table to table, pitching their book. Colussy-Estes said it’s also helpful to leave advance review copies or free copies in the “galley room” at such events. The bookstores don’t sell such copies, but they do use them as customer appreciation gifts and put them in the hands of readers after they’ve had a chance to review and share with bookstore staff.

The best way to approach a bookstore about carrying your book? Unfortunately, there is no one approach that works for all. It depends on the store, so it’s absolutely critical for authors to do their research on the store and figure out their preferences and processes. McNamara prefers authors mail in a copy of their book rather than walk into the store. She doesn’t want an email pitch because she doesn’t always pay attention to emails or respond to emails. “It’s like telemarketers calling. It’s the same thing,” she said.

On the other end of the spectrum, Colussy-Estes doesn’t want copies of books sent in to him; he would prefer to be emailed. But he was frank: It’s rare that he stocks books based on authors reaching out. Only if he sees demand for the book will he stock it. “Unfortunately, that does put it on the author to sell the book,” he admitted. “Shelf space is at a premium. Everything has to pay for the shelf space,” he said. One of the reasons he decided to stock one of Cuevas’s books is that she told him directly that it was clean YA and works for younger YA readers. There isn’t a lot for younger YA readers on the market, so the book fills a niche for his store. That’s valuable information a bookseller wants to know and can use to sell the book.

If you want to have a bookstore event, realize that very few copies will sell, even when everyone puts in their best effort. “It’s hard to get people to come out for events,” Cuevas said. “Do not expect to sell unless you are a huge author with a huge following.” Even authors who can get a big turnout are likely to sell only a modest number of copies. Colussy-Estes said they had a huge turnout for an up-and-coming Australian YA author who is prominent on BookTok but doesn’t typically come to the US. She had a very long line for signing, yet the number sold was only 30 copies. “That’s because a lot of people brought copies from the outside,” he said.

McNamara said she’s open to events as long as she thinks the book can sell. But she rarely orders more than 10 copies unless the author is a well-known entity and has a huge following. She emphasized that the burden is on the author to sell their own book. “Press your family into going, press your friends. If it’s a good turnout, we sell your book. There’s no magic if the bookstore promotes it. It does not guarantee attendance. We really need the authors to do their own legwork. Get out there and tell people you’re doing an event. If there’s a local newspaper, put an ad in it. Share to all your Facebook groups.”

Cuevas said the author has to offer very clear communication with stores about who is doing what and how many people you expect to attend (and how you arrived at that number) so the store can prepare accordingly. To promote her bookstore events, Cuevas creates posters and takes them to local businesses that are kid-lit friendly and that get a lot of foot traffic—places where people who read books normally hang out, like coffee shops. “Hopefully you have a community of writers and authors in your area who want to support your book, and they’ll come out for your event,” she said.

The booksellers also offered these tips for self-publishing authors:

Having your book available through Ingram with a 42 percent discount is essential. (When using IngramSpark, this means setting a 55 percent discount, since Ingram takes a cut of the action.)Most stores require books to be returnable, although some stores might be willing to work on consignment or sell copies to the author after a store event. Note that while Amazon KDP offers an option for expanded distribution that makes print books available via Ingram, its discount is half of what bookstores typically require, and the books aren’t returnable.For store placement, Colussy-Estes said it’s important for indie authors to know what the market looks like for their genre and category. “If you’re thinking of a book for the four- to eight-year-old market, know what those books look like,” he said—indicating that many self-published books look nothing like other published work sitting on the shelf.Don’t forget to include links to Bookshop or your local bookstore on your author website.Never, ever pitch your book to a store by calling it an Amazon bestseller or sending them an Amazon link.One of the themes of this panel—aside from every store works differently—is that authors should be professional and friendly in their interactions, not pushy. Cuevas said that when she travels for work or pleasure, she often stops in the local bookstores just to say hi and tell them who she is. She’ll also share postcards with her book covers and trade reviews. If the store carries her books, she’ll offer to sign stock. “It’s just a friendly hi,” she said. “I’m not berating them because they don’t have my book on the shelf. It’s an opportunity to connect on a personal level.” She said this approach also works well with libraries.

Here’s the tough love: Bookstore placement is probably not your book’s avenue to success. Both booksellers indicated throughout the panel that merely having your book on the store shelf doesn’t take the place of author marketing and promotion. McNamara said, “You have to put in the work. As booksellers, we realize you have to put in the work. There’s nobody else who’s going to promote you. It’s all on you. And it’s difficult. It’s hard.”

Also, Colussy-Estes said, “If your dream is to have your book on a bookshelf in a bookstore, you’re failing your book because you don’t want your book on a shelf. You want your book in a reader’s hand. Think about where that reader is and what’s the best way for them to find your book or be led to your book.” He admits that if a big chain takes your book, then yes—you will sell a lot of books. But more often than not, it’s the legwork done by the author to find their readers and handsell that helps a book gain momentum. He pointed to examples of Kwame Alexander handselling one of his books at farmers markets when bookstores wouldn’t take it and Christopher Paolini’s parents selling his self-published books out of the trunk of their car.

If you’re interested in building relationships in the literary community, take a look at my upcoming class on March 1.

February 16, 2023

Authors Who’ve Launched Their Careers on TikTok

Photo by cottonbro studio

Photo by cottonbro studioThe following article first appeared in my paid newsletter, The Hot Sheet, which covers book publishing industry news and trends for authors. Learn more.

While book sales were down in 2022 compared to 2021, they’d be down much further if it weren’t for TikTok. In fact, the growing sales of adult fiction since 2020 can be credited partly to TikTok’s influence as well as to Colleen Hoover, who is active there. NPD BookScan’s Kristen McLean has noted in particular, “When we looked at romance author sales earlier this year, it was clear that BookTok is contributing to the most romance gains and helping to create a new romance fan base among young readers. … This truly is a whole new group of readers coming to this genre.”

Consequently, more authors than ever are wondering if they ought to join for the sake of book marketing and promotion. While there isn’t a right answer for everyone, late last year the Women’s Media Group hosted a panel on how to tap into the power of TikTok; it featured two successful self-published authors and a social media manager at Barnes & Noble.

Poet and author Shelby Leigh built her TikTok presence by creating engaging content for people dealing with mental health issues. When she first joined, she had self-published two poetry books; her bestseller of the two was re-published by Simon & Schuster in July 2022 because of her sales track record. She has a third book on the way and left her corporate job to pursue writing full time—and she says no one in the world believes her when she says she’s a full-time writer of poetry books. (Her success feels reminiscent of the success of Rupi Kaur and other Instapoets, who began using Instagram to share poems in the early 2010s and went on to commercial stardom.)

When she joined TikTok, Aparna Verma knew that she wanted to target South Asian readers with her Indian fantasy novel, The Boy with Fire. “One of the pitfalls as authors is we tend to make videos that are writing advice,” she said. “But you have to talk to the people who are going to buy your book, and those are readers.” Her book hit number one on Amazon in its category and was featured on NBC News. It will be republished as The Phoenix King next year by Orbit, a division of Hachette.

Both authors needed some time to warm up to TikTok and be convinced of its value. Leigh said, “It was nerve-wracking and challenging,” and very different from the type of content she was posting on Instagram and Tumblr. Verma was convinced to join by her younger brother, who told her it wasn’t just people dancing. And while B&N social media manager Livy Oftedahl joined TikTok in 2017, it wasn’t until 2020 that she landed on BookTok, where she rediscovered her love for books: “I found this beautiful community of people just talking about genres I really felt attached to.” She now plays a key role in developing Barnes & Noble’s social media content and strategy, particularly its TikTok account, @bnbuzz.

What makes a good BookTok video: Leigh said one of the most important things is hooking people in the first second. “You have to move fast and show your audience something engaging,” which might mean showing something visually interesting or adding text overlay that people will read. That text needs to hook people with a single line. The good news for time-strapped authors: You can use the same format once you’ve found what works. For Leigh, that’s reading poems and doing page-flip videos where you flip through the book, with text overlay and calming music. For nonfiction authors, Leigh recommends speaking directly to the audience related to your nonfiction topic, rather than general BookTokkers. She targets an audience interested in mental health, not poetry lovers. Research other nonfiction writers and readers in your category and see what they’re posting—what style of video. That’s the best way to see what works, she advised.

For novelists, learn the popular BookTok tropes and point to them in your work. Examples of such tropes include the meet-cute and enemies-to-lovers; the best way to learn about such tropes, said Verma, is to simply take a month or more to consume BookTok content and learn about them firsthand from community members. (That said, here’s a list to expedite the process.) Verma will show a quote from her book tied to the trope, then pair it with a Bollywood song or tune to appeal to her audience of South Asians; she knows her audience and what they want to read and calls it out explicitly.

Oftedahl says there are two main video types she uses for Barnes & Noble’s TikTok account. One is a transition video, which is useful for her because she’s working with a lot of books at once. So even if she’s trying to sell a particular title, she will put it next to others. “See this book? These are the rest of them I want you to buy,” is how she described the approach. The other type of video is audio-driven based on TikTok trends. The latter type of video, however, requires consuming a lot of TikTok content so you know what people want to see and hear, then twisting the trend to fit the book you want to put in people’s hands. (Oftedahl mentioned spending hours each week just scrolling through TikTok to absorb trends.)

Engage in the comments for your own videos and on others’ videos. Leigh recommends putting the name of the book in the comments and where to find it—especially if there’s any doubt the video is about a book (rather than, say, something in real life that happened to you). Usually she will add a question to get the audience engaged. Verma said she has created meaningful visibility for herself by commenting on other people’s videos in addition to engaging on her own. It demonstrates to others that she’s an invested member of the community. She will also sometimes post a video reply to a great comment, which TikTok might send out to a totally new audience, alerting more people to her book.

But what about the time sink? Or preparing to look good on camera? It might not be as burdensome as you think. Editing videos on TikTok has become very easy; no third-party apps or fancy tech is required. In fact, getting fancy is antithetical to the point of the platform, where authenticity is prized. “People don’t want to see professionally made videos,” Leigh said. “You can be dressed down. You don’t have to look a certain way. Don’t let that hold you back.” In 90 percent of her videos, Leigh does not show her face; she shows the book. While Verma typically shows herself—a format that works for her, especially since she sometimes wears traditional dress and jewelry—she’s had clients who’ve succeeded with TikTok videos that are very audio focused.

Once you make something and it does well, you can re-purpose or re-use it in many ways. Verma said, “It’s the same content, but just repurposing it by changing one or two things—the text, the song, the intro clip—that’s where you can get really creative. You’re not reinventing the wheel.” If you want to see explosive growth, Verma recommends posting three videos a day to help ensure that at least one breaks out. “It’s very much a numbers game,” she said. But once you find a format that really works for you, things become much easier. Today, someone like Leigh can get a meaningful video up in five minutes. And don’t assume that longer is better; Leigh typically produces content that’s less than 30 seconds, with seven to 15 seconds being a common recommendation in the community.

Parting thoughts

While TikTok is characterized as a young people’s platform, it has more than a billion users and encompasses people from all ages and walks of life. “There are going to be readers for you on TikTok,” Leigh said. “It’s just down to content. I’ve seen authors of all genres succeed.” However, for better or worse, the general BookTok hashtag has become overused, and it’s tough to research and understand the community from that alone. “What you really have to do is find something a lot more specific to the audience you’re looking for,” Oftedahl said. Then, once you’ve found your community, interact with them as much as possible. “No one wants an idol they look up to. They want a person they can talk to.”

If you’re interested in learning TikTok, join me and Rebecca Regnier in March for the online class TikTok Basics for Writers.

February 14, 2023

The Business Skill I Wish I Could Grant to All Writers

Photo by Sora Shimazaki

Photo by Sora ShimazakiIs it querying? No.

Networking? No.

Marketing? No.

Of course such skills are terrific assets, but if I could wave a magic wand, I’d grant all writers the skill of negotiation. By and large, writers don’t even consider trying to negotiate; they just accept the terms/contract/pay that is initially offered.

This is partly a quirk of an industry where writers regularly get stepped on and asked to work for free in exchange for exposure. Writers might see themselves as without power or agency, which is not unfounded, but it can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. You can’t wait for permission or the “right time” to negotiate a better deal for yourself. If you don’t ask, you don’t get.

Here are common barriers when you’re negotiating for yourself.

Fear that you’ll lose the opportunityYou’ve spent years trying to secure an agent or publisher, then the contract arrives from the other party. You may be tempted to quickly accept and sign. Because if you make a “fuss,” you’ll look ungrateful, right? If you ask questions, you’ll be a nuisance, a problem person. Maybe the other party will be offended if you ask for a better arrangement, or even retract the offer.

If you’re dealing with someone who works in the business, such as an agent or publisher, they will not be offended by questions or an attempt to negotiate. Just about every arrangement is negotiable on some level (with exceptions for blanket terms of service agreements from tech companies, among others). But few writing contracts or agreements are “take it or leave it”; those that are deserve to be questioned. Many “take it or leave it” situations arise, in fact, from either inexperience or fear. “My lawyer told me not to change the contract” is a familiar line from small publishers operated by people who may not understand the contract they’re sending you.

So what happens if you do encounter someone angry or offended by your attempt to negotiate? First, examine your approach. Is it respectful and in good faith? If you negotiate by saying, “How dare you insult me with this offer! Are you a second-rate operation? Don’t you know who I am!” then you might find the other side less cooperative. But if your approach isn’t combative, and the other side is resistant to answering questions or having a conversation, you have to ask yourself if that’s a business partner you want to move forward with. Your difficulties are likely to compound after signing with a partner that’s non-communicative.

When I negotiated contracts at a mid-size traditional publisher, most authors did not attempt to change the boilerplate contract. Nor did they ask any questions about it. Usually, when they did push, it was for a bigger advance. But they could’ve asked for something much more valuable in the long run: better royalty rates and escalators (increased royalties when certain sales thresholds are met).

But more surprising? Not even the majority of agents negotiated the contract as well as they should have, because they were so advance focused. I wish I could say that your agent will definitely negotiate all the finer deal points, but that’s not the case in my experience. So even if you do have an agent, you should be asking them questions, too.

You don’t know what’s negotiable or what’s reasonable to ask forOne of the big problems in publishing is the lack of transparency around earnings and what other people are getting paid. While there have been community efforts to dismantle this cloak of secrecy, there’s an additional challenge: so many scenarios and terms are unique to each publisher, agent, author, and book. And this is why agents can be so invaluable: they have experience that helps them know where and when to push on behalf of their clients (despite what I mentioned above). So what can you do when working on your own?

Aside from educating yourself by reading model contracts from the Authors Guild, Writer Beware, and other advocacy groups (as well as asking around privately), research your potential business partners to the best of your ability and ask a lot of questions about the agreement or terms, like “Is this typically what you offer?” or “Where is there flexibility in this deal?” You’ll be surprised at how willingly people offer up this information.

You don’t know what you’re worthThis issue is closely related to the above, especially when you’re new to the industry. I find writers struggle with this particularly when it comes to speaking and events, freelance gigs, consulting and editing, and side gigs. Mostly, writers undercharge because there is a culture of doing things for “exposure.” Sometimes the author who’s directing that big writing event does it for free or cheap, and they rely on volunteers, and perhaps the whole team works for exposure or platform building. Then you layer on the nonprofit status of so many writing organizations (and schools or libraries), plus the idea of “giving back” to the community, and you end up with authors who have a lot of anxiety surrounding a request for what, in the end, is fair compensation.

I myself spoke for free for way too long and continually underpriced myself. But when I started asking for meaningful pay, I was rarely turned down. Of course, I have accrued leverage over the years, and not everyone can successfully make the same asks that I can. You should try anyway and test the limits. Also think creatively about other ways you can make the situation beneficial for you. If you can’t get the compensation you want, is a trade or barter possible? Can you figure out a revenue share model? Can you get a bonus based on performance? Better escalators? Etc.

Parting thoughtsI still fail to negotiate well, and sometimes regret agreeing to terms I know aren’t great. (Sometimes you just get tired and agree so you can move on with your life.) But I have never regretted asking for more or seeking a better deal. The worst that can happen is you get a “no.” Funny enough, I’ve worked with organizations who say “yes” one year and “no” the next—to the exact same terms. You won’t always be successful in getting what you want. But you do have the power to walk away from a deal that’s not serving you well. There will be other offers and opportunities, I promise.

Join me on Feb. 22 for the online class Negotiation Skills for Writers with Pia Owens; all registrants will receive my Contracts 101 guide. Recorded if you can’t make it live!

February 7, 2023

Querying & Submitting in 2023: Q&A with Jeff Herman

Jeff Herman is the author of the long-running marketplace directory Jeff Herman’s Guide to Book Publishers, Editors & Literary Agents, now in its 29th edition. He’s also the coauthor of Write the Perfect Proposal. He has presented hundreds of workshops about writing and publishing and has been interviewed for dozens of publications and programs. His literary agency has ushered nearly 1,000 books into publication, including many bestsellers. He lives in Stockbridge, Mass.

On the occasion of the release of his 29th edition, I asked Jeff the following questions about today’s environment for querying and submitting work, given his decades of experience in the industry.

Jane Friedman: I’m hearing a new level of frustration from writers about agents and publishers who don’t respond at all to queries and even requested manuscripts, not even to send a form rejection. Do you think it’s true there’s been an increase in “no response means not interested,” and if so, what do you make of this?

Jeff: I don’t think any agent or editor can accurately assess if ignoring or ghosting prospective clients has become more common in recent years, but I can be candid about my own experience. It’s always my intention to respond to each author’s submission. That said, I sometimes don’t, at least not in a timely fashion. Why? Because I don’t always get around to reading their submissions. This doesn’t mean I don’t have empathy or that the work isn’t publishable (how can I know that if it’s unopened and unread?). There’s an old Jewish saying, You can only dance at one wedding at a time. I think that sums up why so many writers never hear back.

Most nonfiction authors realize they need some kind of platform—visibility to the intended readership—in order to secure an agent. One question that gets asked a lot: How big of a social media following is necessary? Based on your conversations with agents or publishers, do you think there’s a magic number that makes a difference? Or are agents/publishers looking at this more holistically? I guess what I’m asking is: Just how important is social media?

Tough question to answer. In my opinion, the power of an author’s platform, which includes a social media footprint, is in the eyes of the beholder. And even when someone clearly has a huge platform that leverages a large advance, the book’s sales more often than not never recover the advance. I’d like to say that publishers have learned that a great platform won’t necessarily convert into great book sales, but I’d be mistaken. The platform/sales metric is a moving ball with a mind of its own that doesn’t care what everybody thinks is supposed to happen. Some editors probably suspect that some advances are too high but will go along to get along. And bidding wars usually override smart math. Regardless of reality, publishers want to believe that platforms matter. It follows that writers and their agents need to accommodate their belief system.

Memoir seems to lie in a gray area as far as what materials authors need to prepare. Some agents/publishers want a full manuscript, some want a proposal. Maybe some even request both. How do you advise memoirists to navigate this efficiently? Should they prepare a proposal before starting the submissions process or start by trying to sell on the basis of a manuscript?

In my experience, memoir can be sold on the basis of a traditional nonfiction proposal. However, I think it will need an expansive outline of at least 250 words per chapter and at least 2500 words of sample text. This should be enough to enable editors and agents to assess the work’s viability. Sometimes they might request more, which is a good thing.

If an author has been self-publishing for some time, and decides they want to pitch a new project, should they disclose that in the query letter? If their self-published titles didn’t sell very well, will that be a problem for securing agent or publisher interest?

Bookshop • Amazon

Bookshop • AmazonIf the self-published book has sold more than 1000 copies, I think most traditional people will think that’s pretty good. However, if the sales were due to a one-time promotion and the current Amazon ranking is poor, I advise briefly mentioning the book(s) near the bottom of the query. Interested editors and agents will want the writer to explain why their new book won’t share a similar fate, which can be challenging. Fortunately, most book professionals know that most self-published books don’t accurately reflect what the writer might have achieved with a traditional publisher. In such scenarios, the writer will have to make extra efforts at proving they are in a much stronger position to sell sufficient numbers of the next book if attached to a traditional structure.

Based on the book Jeff Herman’s Guide to Book Publishers, Editors & Literary Agents, 29th Edition. Copyright © 2023 by Jeff Herman. Published by New World Library.

February 1, 2023

How Author Platform Connects to Author Brand

Photo by Peter Aroner on Unsplash

Photo by Peter Aroner on UnsplashToday’s post is excerpted from Brand the Author (Not the Book) by Karen A. Chase (@KarenAChase).

Certain words and phrases are bandied about all the time in publishing, but they don’t always make sense. One of the biggest is author platform. You may have attended enough writing seminars and conferences to recognize that even people in publishing aren’t consistently using the term.

How and where authors reach readers: that’s platform. It’s a combination of four factors, and let’s use the TV show Gilmore Girls to help visualize it.

Message: an announcement shouted to the citizens of Stars Hollow from the gazeboTarget Audience: the Stars Hollow citizens gathered to hear itPlatform Tools: the gazebo and the directional signs to itBrand Elements: the gazebo they see and experienceIf your message and tools are built effectively, those in your target audience will be so invested in your platform, they will personally deliver that message to anyone drinking coffee with Lorelai and Rory at Luke’s Diner.

If you need to run off and watch a few episodes to understand my analogy, I’ll wait here. For those who have already seen the show, let’s start with the author message…

1. Author message (the announcement from the gazebo)I know you have something to say. You wrote a book! But your author message is not the subject of that book. Rather, your author message is tied to why you wrote that book.

For instance, my first novel, Carrying Independence, is about a guy hired to help gather the final signatures on the Declaration of Independence. But why I wrote this story has nothing to do with the document. I firmly believe we can learn about ourselves by traveling and engaging in history.

Sure, other authors are also motivated by one or both of those things, but when I couple my belief with my particular brand of humor and unbridled nerdy enthusiasm, my author message becomes intrinsically mine. It becomes my purpose, and one my readers can experience with me. They can #TravelWithAdventure while #ChasingHistories, too.

For some authors, the reason they write is to provide an escape. For others, it may be to debunk faulty thinking. Once you define your message, you must figure out how to share your message.

2. Target audience (the citizens gathering around the gazebo)These are the loyal readers most likely to gather around your gazebo (real or virtual). If you are a young adult (YA) author, yet your Twitter feed and primary contacts are moms and librarians, you’re not speaking directly to your readers. Or, as I said to a YA author with this problem, your target audience of teenagers is talking about books in the cafeteria while you’re hanging out in the teachers’ lounge sounding like a boring grown-up. Yes, librarians recommend books, but authors should connect with the bullseye of their target—the people most likely to jam their noses into your book and who will then turn to their friend and say, “You also have to jam your nose into this book.”

Your readers hang out in certain places online and physically. They have other books, magazines, movies, vocabulary, and activities they love (or hate). For example, if you write Georgian romances, your readers are likely women ages 16 to 65 who read Jane Austen, follow Colin Firth, know the difference between corsets and stays, and might be members of Regency societies.

3. Platform tools (the gazebo and directional signs to it)If all you have is a gazebo from which to sell your book, your readers will consist of only those citizens who happen to come to the town square. That means you need to think bigger, broader. A platform tool is anything a reader will engage with that comes from you. If they can see it, touch it, or hear it, it’s a platform tool. If you’re a cookbook author or your novel includes recipes in the back, your loyal readers may even taste it!

Tools, like directional signage pointing to the gazebo, are the means by which your target audience finds and engages with you. What are your primary tools? Your book(s), website, and newsletter. You also have social media, advertising, publicity, presentations, and even printed materials such as bookmarks and business cards.

However, not all platform tools are effective at capturing your particular target audience. YA readers are less likely to be on Facebook than on Instagram, for example. And AARP events and retirement communities won’t be ideal places for middle-grade authors to give presentations. Examining your goals and existing assets will help you narrow down which tools are best for you and prioritize which ones to build first.

4. Author brand elements (the gazebo they see and experience)Going back to our Gilmore Girls reference, when the citizens of Stars Hollow gather around to hear your message at that gazebo, what pray-tell does your gazebo look like? Does it look like a faded Victorian postcard, the colorful Barkcloth of Uganda, or a sleek Aston Martin à la James Bond? Brand elements consist of the author photo, the colors on your materials, the fonts that grace all your printed materials, and the way all those elements work together.

Brand elements are not designed using the cover of your books because each book design has its own set of brand elements. Book covers can vary wildly. You might not always have the same publisher or designer. You might write across genres as well. Three of your books could be repackaged and their covers redesigned.

Because book design does not affect your long-term author image, choose brand elements by considering your message, audience, and platform tools. You must also restrain yourself and keep these elements simple. Too many fonts or colors can lead to inconsistencies. Having fewer elements can contribute to greater longevity. All these brand elements, platform tools, and messaging come together to be your …

Author brandAn author brand is the experience readers have when they hear your message and interact with your particular platform tools. Think of the brands you are most loyal to. What do you see? How do you feel about them? If I say Coca-Cola, you can see the swirling font, the red color, the shape of the bottle. You might also get nostalgic about those warm and fuzzy holiday commercials with the polar bears. All of that adds up to how you feel about the brand. The same applies to authors.

Every effective brand has these three characteristics going for it: Unique. Consistent. Authentic.

Unique. REI branding is different from Patagonia even though they both sell outdoor gear. Look at branding for Sadeqa Johnson versus Danielle Steel. Readers feel something different for each of these authors even though they both write historical fiction. Authors, like brands, can’t copy one another.

Uniqueness breeds loyalty. Be who you are. Own who you are.

Consistent. If an author’s PowerPoint presentation looks like his or her website, which also looks like the author’s Twitter page, website and business card, then readers can be certain of who they’re following. Coca-Cola has had that same logo since 1886—it’s consistent, even if the company’s ad campaigns change every year.

Authentic. We live in a transparent world and audiences are getting better at pointing out B.S. when they see it. B.S. = Brand Stupidity. B.S. happens when a brand says one thing but the reality and/or actions are quite another.

That’s especially important when it comes to your author message. For example, I love nearly everything about traveling, and I believe travel is necessary to understanding history. However, if I secretly hated traveling and never left home, eventually my inauthenticity would catch up with me. Your words and actions have to match.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out Brand the Author (Not the Book) by Karen A. Chase (@KarenAChase).

January 31, 2023

Create a Book Map for Your Nonfiction Book

Photo by DS stories

Photo by DS storiesToday’s guest post is by Ariel Curry and Liz Morrow of the Hungry Authors podcast.

Imagine you’re starting out on a road trip. First, you have to know where you’re going; then, you need a map to help you get there.

It’s the same with books. So often, aspiring authors start off on a “road trip” without a clear sense of where they’re going, let alone how to get there—and so they end up lost. We’re all for enjoying the journey just as much as the destination, but if you plan on bringing readers along on your trip, you better well have a plan. No one wants to sit in the car for hours while their driver says, “Let’s take this next turn and see what happens!”

Creating a book map is the best way to ensure you know where you want to take your reader, and how you’re going to get there.

A book map is a visual representation of your book’s structure. It can be as high-level or as detailed as you want, but the goal is that it provides a clear picture of exactly what content is going to go where in your book—creating a “map” that you can follow as you’re writing. Fiction authors commonly use book maps to track their plots and subplots and make sure that open story loops get closed.

But we believe book maps are invaluable for nonfiction books, too, where the goal is to inform, instruct, and inspire a reader. A book map will help you maintain momentum and ensure that the reader’s journey to your destination is as smooth as possible.

Here are a couple examples of book maps we’ve created with authors over the years:

You can make book maps with analog tools like sticky notes or index cards laid out on a table or stuck to a window. A giant whiteboard often comes in handy. Or you can use the digital method, with tools like Mindmeister or Jamboard. The important part isn’t the appearance (although we love a good color-coded map!); it’s the thinking you do to create a logical journey through the book.

Here’s how you do it.

Get clear on the transformation.All books are about transformation. Fiction is about the transformation of a character; memoirs are about the transformation of the author through an event/situation; and other nonfiction books are about the transformation of the reader. That’s what we’re focusing on today.

To figure out your reader’s transformation, you have to ask three questions:

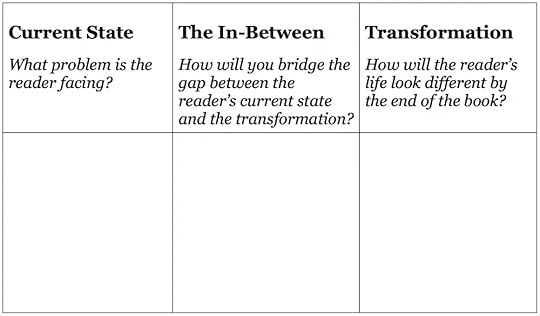

What is the reader’s current state?How do I want the reader to be different by the end of the book? (the transformation)How can I help the reader get there?We like to brainstorm this “transformation tale” in a table like this:

Don’t hold back—put everything you can think of into this table! Feel free to download your own version of this table here so you can play with it.

Creating this transformation tale helps us put boundaries around our book; it helps us decide what belongs and what doesn’t, where to start and where to end.

Map out the middle.The “In-Between” section of your transformation tale is what will become the chapters of your book, so this is where we need to spend most of our time. If you’re feeling stuck on the “In-Between,” ask yourself how you accomplished the same transformation, or what you would say to a friend who came to you for advice in accomplishing that transformation.

As you look at your “In-Between” brainstorm, see if you can identify a possible pattern or order for the chapters to fall into.

Your in-between might follow a sequential order, like steps in a staircase leading up to the destination:

First, this needs to happenThen, this can happen nextAnd that can happen afterwardsThen eventually, you’ll arrive at your transformationOr your in-between might look more like a list of ingredients for a salad—toss everything together, and voila! Transformation.

Whichever approach you take, these ideas will become your chapters. Put each idea on a sticky note or index card, and lay them out horizontally across your window/wall/table. Try them out in different orders. The right order may come to you quickly, or you may have to play around with it until you find the one that feels the most intuitive.

Remember: Your book’s structure should feel intuitive and logical to the reader! If you feel stuck, bring in a trusted friend for their feedback.

Once you have these ideas in the right order, under each idea you’ll want to create cards for the elements that will comprise each chapter. We recommend including for each chapter:

A good hook that captures the reader’s attention at the beginning of the chapter2–3 key points that lead up to the chapter ideaStories to help illustrate those ideasInteractive elements like reflection questions, tools, or exercises to help the reader apply those ideasA closing section that wraps up this chapter and transitions the reader to the next chapter ideaYou might decide to include other elements as well, depending on your book’s content (like data, personal stories from your life, quotes from other books, etc.).

Put each of these elements on separate cards and list them vertically underneath each chapter’s card. Bonus points if you use different colors for each element, so that you can see at a glance where you might be missing something when you look at your whole map!

To do this for each chapter takes a lot of brain work and time. It can often take us 6 to 8 or more hours with clients to make sure we’ve captured everything we want to include in the book. Go slowly and break the process up over multiple days. When you’re ready to start writing, you’ll be so glad you took the time to think through everything!

We find it’s almost impossible for writers to get stuck once they’ve done all of this thinking. A little bit of a time investment up front can save you days, weeks, months, or even years of wandering without a plan for your book.

Helpful remindersHere are the keys to making more efficient and effective book maps:

Practice mapping out your comparative titles first. You’ll learn so much about how other authors organize their thinking on similar topics, and you’ll clearly see how your book can stand out and add value to your reader.Book mapping is iterative and adaptable. Like using Google Maps when you drive, your book map can and should change to redirect you when you run into a theoretical “roadblock.” Remain clear on the ultimate transformation you want to accomplish, but realize that for most books, many roads will get you there. Choose the one that feels most intuitive to you and be willing to try something different if that doesn’t work.Often, when we finish creating a book map, authors step back from the whole thing and realize—that’s it! That’s the book. It’s the best part of the whole process—when you realize that you really can do this. You’ve basically already done it! Writing the book becomes an exercise in simply putting flesh on those bones. Seeing your book map is a big step in building your self-efficacy to write the book.

We love seeing authors’ book maps, too! If you create a book map, please tag us @hungryauthors on Instagram so we can admire your brilliance and share your work with the world!

January 26, 2023

Promoting Your Book as an Introvert in the Age of TikTok

Photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash

Photo by Nick Fewings on UnsplashToday’s post is by author Julie Vick (@vickjulie).

One question I was asked a few times around my book launch was, “How is it to promote a book about introversion when you are an introvert?”

The short answer I usually gave: I’ve figured out ways to make it work.

When I wrote my humorous advice book for introverted parents Babies Don’t Make Small Talk (So Why Should I?), I had been following other authors and the book industry long enough to know that the realities of the industry (even with a traditional publishing deal) meant that authors need to contribute to the marketing of their book.

The path to getting my book published also involved writing a proposal with marketing and promotion sections in which I said what I planned to do for promotion, so I knew the day would come when I needed to actually do those things. My book was also a project that I had spent a lot of my time on, so it was natural for me to want to try to contribute to its success.

What I’ve learned: there are a lot of different ways to promote a book. No one way is going to be the right fit for any author or book. But given my introverted (and at times socially anxious) personality, here are some things that worked for me.

Find comfortable ways to use social mediaI started using social media before my book released to help build a platform and to promote my freelance and humor writing. Putting my work out there definitely took some getting used to, but I eventually found ways to use social media that felt comfortable (and often enjoyable!).

For me, that has meant not posting too much—taking the time to post and then interact with comments on a post can be draining even when I’m enjoying it, so I don’t follow some of the advice that seems to advocate for posting every hour on the hour and only maybe taking a break when you’re asleep. I try to focus on quality over quantity and spend a good portion of time on social media commenting on and sharing other people’s posts that resonate so it doesn’t become all about me.

I also don’t feel comfortable going live on social media or showing my face a lot, but I’ve found that there are plenty of ways to still use the platforms. As a humor writer, that often means posting jokes or videos of my book or sharing the work of other writers in my genre.

I’ve also learned to spend the most time on social media platforms that are a good fit for me. I started out using Twitter because I liked the text-based and casual feel of it and have found it particularly useful for connecting with writers and others in the industry (although it may be becoming less so with recent events at Twitter).

I now also frequently use Instagram and have even dipped my toes into TikTok. On TikTok, I often focus on showing jokes (turns out you can just overlay the text of a joke over a video background) or my own or other humor books and have even had a few videos take off. Different social media platforms appeal to different authors for different reasons but finding a good fit helps.

Focus on what you already knowI feel more comfortable doing something once I’ve practiced it a lot, so I tried to take advantage of skills I already had when my book came out. I’ve been teaching at the college level for over 15 years and got a crash course in teaching on Zoom during the pandemic, so teaching some virtual courses felt like an easy element of book promotion that I enjoyed.

The other skill we as writers already have is, of course, writing. Writing companion pieces (like the one you are reading right now) is something I’ve done and continue to do for book promotion. I think writers sometimes think that promotion has to mean social media, but I’ve found writing freelance pieces to be a good option. I had experience freelancing before my book came out, but even if you don’t, there are lots of great resources out there to get you going.

If there is something that you already know how to do, then think about how you can transfer your skills to book promotion to take advantage of that rather than trying to reinvent the wheel.

Consider podcastsI enjoy listening to podcasts and also enjoy meaningful one-on-one conversations, so pitching podcasts around my book’s topic felt like a natural path. I reached out to podcasts that I enjoyed and have appeared on several podcasts since my book came out.

Most of the podcasts I’ve done have assured me that if I stumbled while saying something I could start over and it could be edited out later. I did not typically need to take advantage of starting over but knowing it was an option helped calm my nerves about talking on the fly, and I’ve found that although I might have some nerves just before recording, they often go away once I’ve settled into a conversation with the host or hosts.

Take advantage of conferencesSince introverts have a reputation for not wanting to leave the house, you might find this recommendation surprising. I find writing conferences draining, but I also love attending them. In a profession that is often solitary, I find the time I spend at conferences learning new topics and meeting other writers in real life (many of which I first developed relationships with online) invaluable.

But a day full of back-to-back events takes a lot of my energy. So, I try to pick and choose what I go to, skipping out on sessions when I’m feeling drained and making sure I have enough time to recharge in my hotel room alone at the end of the day. Virtual conferences have also presented a new way for me to learn from and connect with other writers.

The connections I’ve made with writers at conferences have also been useful in book promotion. A conference I attended last year led to podcast appearances, and many writers I’ve met at conferences have been the ones to help me at many stages in the book publishing process from guidance on how to find an agent to help getting the word out on launch day.

Find your peopleHaving a book come out is inevitably filled with some ups and downs and having other authors to talk to who were going through the same thing was helpful for me. I partnered with other authors on virtual events and we often helped boost each other’s social media posts.

Many of the people I partnered with I had met through online venues like Facebook writing groups and Twitter. If my book had come out in the time before social media, I think forging a lot of these relationships would have been more difficult. But connecting online often feels easier for me than connecting in person, so I appreciate that it’s an option now.

It was helpful to feel like I wasn’t going it alone (except for the times when I wanted to go it alone to recharge in my pajamas at the end of a long day).

Planning for a book launch can be daunting as an introvert (and I suspect, also for people who don’t identify as introverts). But finding the right strategies that fit with your skills and personality can make it easier.

January 24, 2023

How to Pursue a Career in Editing: Advice for College Students

Photo by Matthias Heyde on Unsplash

Photo by Matthias Heyde on UnsplashAsk the Editor is a column for your questions about the editing process and editors themselves. It’s a place to bring your conundrums and dilemmas and mixed feelings, no matter how big or small. Want to be considered? Learn more and submit your question.

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Written Word Media. The author marketing hub – Written Word Media makes effective book marketing easy for authors. Known for our five-star customer service, we have helped over 20,000 authors build their careers. Go to WrittenWordMedia.com to learn more and schedule your book promotion in 5 minutes.

Question

QuestionI’m a college student majoring in English. I have had internships but not in the world of editing, but my dream is to be an editor and writer. Do you have any advice or guidance to offer on how to make this dream a reality?

—Desperate Gen-Zer

Dear Desperate Gen-Zer:I’m desperately glad you asked this question. You’ve hit on one of my main concerns in our industry: Anyone can hang out a shingle as an editor, which results in a very wide range of knowledge and experience levels. I love that you are interested in seeking out a path for developing your skills.

You say you want to be a writer too. That’s useful—the skills you learn in that pursuit are the core of becoming a good editor. In fact, although they are very different skill sets, much of what you can do to master one will serve you well in the other.

You’ve asked a pretty enormous question that I need to address in a manageable number of words, so I’m going to give the quick-and-dirty version of how to develop both careers through two essential approaches: Study and practice, with an emphasis on editing (not least because of the nature of this column).

Study the craftWriting and editing both rest on the same foundation: an understanding of story craft and language. You learn how the sausage is made—and made well—and eventually internalize those skills so that they’re automatic; you don’t have to focus consciously on craft and mechanics because they become a part of you.

There are an overwhelming number of resources for expanding your skills. It’s a lifelong process; after 30 years in this business I’m still learning every day. I’m betting you’re already digging into some of them: craft books, classes, webinars, workshops, blogs and other outlets (like Jane’s!); conferences.

You’re already doing one great thing toward your career in majoring in English, which will give you a sound foundation for both writing and editing. (I can’t tell you how often I think back to my college papers in my own English major and think what wonderful training ground they were for learning to analyze and articulate a text’s effectiveness.)

Another thing you could do now is work with your university publications and gain skills in writing and hands-on editing.

For readers who are past their college days, there are reputable programs for learning editing skills, like those offered by the University of Chicago (the masterminds behind the industry-standard bible, The Chicago Manual of Style) and the Editorial Freelancers’ Association (EFA), taught by career editors.

Be discerning about where you learn—there are countless programs claiming to teach editing skills and offering self-declared certifications, but keep in mind there is no “official” set of standards, training programs, or governing body for offering editorial services. Caveat editor.

For insight into editing specifically, I can’t recommend highly enough master editor Sol Stein’s books Stein on Writing and How to Grow a Novel, and A. Scott Berg’s biography Max Perkins, Editor of Genius, which shows intimately how renowned editor Perkins worked with some of our most venerated authors. There’s even a new documentary, Turn Every Page, about the 50-year collaborative relationship between author Robert Caro and editor Robert Gottlieb.

Try not to get too overwhelmed by the amount of info that’s out there—or to subscribe to one school of thought or system too slavishly. The many approaches and techniques you can learn are all tools for your toolbox that you can draw on. The more you learn, the greater your skill set as both a writer and an editor—and the better you will become at both.

PracticeYou mention internships, and I’m so glad you did—editing is definitely an apprenticeship craft, one that’s most thoroughly and deeply learned by seeing it done and by practicing doing it—over and over and over again. There’s a reason for the system at publishing houses where editors work up from assistant to lead editors—there is no more effective way to learn this skill and craft.

This is a crucial place where training programs often fall short. The misconception that you can learn to be an editor simply from a course or certificate on editing can lead to bad editing, a cardinal sin in my mind that can do great damage to an author’s writing and psyche (and charge them for the “privilege”). In my opinion editors shouldn’t hawk their services before they’ve logged solid, relevant experience in the particular field where they’re working (e.g., publishing or academia or journalism, fiction or nonfiction, and specific genres).

There are so many excellent ways to do that—a couple of which I already mentioned above. But also:

Work with a publishing house as an intern or assistant editorThey are legion now, not just the Big Five in New York—find a small press near you. Back in my day (oh, how I love hearing old-people phrases like this come out of my mouth), I started as a freelance proofreader and copyeditor for the Big Six (at the time), long before electronic editing, when all revisions were made on hard copy and I got to see the editors’ and authors’ work right there on the pages I was reading, comments and all, and I learned what got changed and why.

If you can’t find a publisher in your area, try apprenticing with a reputable working pro. (I’ve mentored a number of high school and college students, both through school programs but also one-on-one when a student or fledgling editor contacted me directly.) This is a great way to see what makes for an effective edit firsthand—and to learn directly from a professional editor how they work, what they look for, and how they offer useful feedback to authors.

Work with the people who work with manuscriptsInterning with a literary agency can be another way to hone your skills in action. Reading endless submissions off the slush pile (your likely entry point at an agency) and learning what agents do and don’t respond to as effective and marketable work is invaluable training ground.

Any practice at analyzing a story and articulating its strengths and weakness is wonderful training: I worked in my baby days reading book and screenplay submissions and writing reports on them for a Hollywood producer, an ad agency that specialized in book campaigns, and a fledgling movie-review database engine.

Learn from IRL manuscriptsOne of the most useful things I ever did as a budding editor was join an especially large critique group (more than 25 members) that met weekly and focused on a single submission each meeting. Not only did I get hands-on regular practice in analyzing and conveying what made a manuscript (someone else’s, crucial for objectivity) effective or not, but even more valuable: I got to hear many other viewpoints as well. It taught me what was useful feedback and what was not, gave me perspective on how subjective a craft editing is, and—not unimportant!—the difference between a positive and constructive approach and a dictatorial or righteous one. The latter offered little value to an author.

Another good way to learn: Sit in on as many industry-pro “read and critiques” as you possibly can—at conferences, retreats, classes, workshops. The great value of these lies in seeing what jumps out at these professionals and hearing why—and, in the best-case scenario, how they offer suggestions for addressing areas of weakness.

There are more and more opportunities to do this: Bestselling author George Saunders offers a regular Story Club on Substack where he and attendees analyze short stories for what makes them work (or not). I do something similar, though less highbrow, with book chapters and other forms of storytelling in my Analyze Like an Editor Story Club. Agent Peter Cox of Litopia offers a weekly Pop-up Submissions program where authors submit a page or two of their WIPs and it’s analyzed by Peter, his industry guests, and a “genius room” of fellow authors. Look for similar opportunities to see pros in action.

Learn from everythingI frequently proselytize the value for authors as well as editors in analyzing every single story you take in, in any medium. Steven King famously advised that “Writers write, and writers read,” and the second part of that is as important as the first—but not just reading (or watching) for pleasure, but with an analytical eye.

Get into the habit of analyzing everything: books you read, movies, TV shows, song lyrics, commercials and advertisements, even company slogans. They are all designed to do what any story does: elicit a reaction in the reader/viewer. How do they do that? What makes it effective (or not)? If you are on the edge of your seat in a book or movie, for instance, stop and consider what you are actually feeling and why—then trace back what elicited that reaction. Then go back and pick apart specifically, concretely how the storyteller set it up.

Learn by doingUltimately the best way to master both editing and writing is to do them as much as possible. With writing that means actually putting words on the page, editing them (more chances to learn your editing craft!), revising, polishing, and finishing a story—and then doing it again. And again. And again. When you’re ready, get your work out there: to agents, to publishers, to readers. Keep writing other things meanwhile.

With editing, start editing. This one is a little trickier, because good editors command commensurate rates, and they’re not cheap. If you aren’t yet experienced or skilled enough to warrant those rates it’s a bit unethical to charge them—so start small.

I did my first developmental editing jobs at very low rates—I had a solid track record as a copyeditor but not as a dev editor, and I didn’t feel right asking an author to take a huge financial chance on me. I was lucky enough to have become friendly with a few high-profile authors through my copyediting work (another benefit of that kind of training—contacts), and they were pleased with my work and told more author friends about me, and I built my résumé and skillset, gradually raising my rates as my skills and experience—and confidence!—increased.

Think of it like any other job—you work your way up in ability and experience, and your salary grows accordingly. Editing is not a quick-profit side hustle to make money off of authors—it’s a demanding, complex skill that takes extensive time, learning, and experience to master. When you are able to offer more, you can eventually charge more.

This may sound like a lot of training and work—and it is. But so is any highly skilled pursuit: You wouldn’t want a surgeon operating on you if she doesn’t have pretty extensive knowledge, skill, and experience.

But oh, it’s rewarding. As a writer you get to bring something new and unique into the world with every story you create—one that might also offer something meaningful to another soul.

Being an editor, in my “book,” is even better yet: You are the midwife to writers bringing hundreds, even thousands of stories into the world—and helping an author fully realize their own creative vision. It’s honestly among the most gratifying experiences I have ever had—and as an editor you get to do it every day.

Good luck to you, Gen Z. You’ve chosen a sometimes tough but often magnificent road. 😊

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Written Word Media. The author marketing hub – Written Word Media makes effective book marketing easy for authors. Known for our five-star customer service, we have helped over 20,000 authors build their careers. Go to WrittenWordMedia.com to learn more and schedule your book promotion in 5 minutes.

January 17, 2023

The Key Value That Makes Retreats Magical

Photo by Kyle Glenn on Unsplash

Photo by Kyle Glenn on UnsplashToday’s post is by Allison K Williams (@GuerillaMemoir). Join her on Saturday, Feb. 4 for the online workshop Create Live or Virtual Retreats That Sell.

Three times a year, I get to spend time with great people in amazing destinations, teaching what I love to see learned. Two more times, I lead virtual retreats, with everyone in their own space, yet somehow deeply connected to each other and their work. Every time, I go home well-paid, my own expenses covered and a healthy profit margin. But the magic of great retreats isn’t that they help the leader’s bottom line—it’s in transcendence, where guests are able to commit to a specific part of their personal development, with guidance and support, experience transformation, and go home feeling as though their work, too, has profited.

What makes that transcendence happen? Three weeks ago, I’d have told you “careful budgeting, flexible scheduling and knowing who’s gluten-free,” but learning to pee again has taught me something more.

Yes, pee. Stick with me, OK?

In Bali, right before New Year’s Eve, I was walking home when a drunk tourist on a motor scooter on the wrong side of the road ran me over. I ended up in the hospital for a week, had surgery, and left with a brand-new plate in my skull that I’ll use to make new friends at TSA checkpoints forever.

In the hospital, my overall project was pretty big—to heal—but my daily focus was very narrow. For the first two days, my only goal was to achieve a 30% recline. Then to start eating. My stretch goal for this “retreat” week was to visit the toilet unaided, because they weren’t going to discharge me if I couldn’t. (I was even more committed because bedpans are not well-made for women.) For three days, I sat up farther and practiced putting my feet on the floor. Finally, I was able to be carefully led to the toilet, where I peed like a champion. It was almost as good a victory as finishing a manuscript—yet still a very small step.

Start with specific, limited daily accomplishments.Achieving life-changing transformation at a retreat—for yourself or for your guests—starts with specific, limited daily accomplishments.

Narrowing focus also means removing outside distractions. In the hospital, I didn’t have to track my medication, because the staff were responsible for what I got, how much and when. When I host a retreat with a single chef, there’s a poster in the kitchen with everyone’s photo on it: Who gets still or sparkling water? Who’s the gluten-free vegan? Who shouldn’t be offered wine at dinner without making a big deal out of it? Details like not having to be (as) responsible for their recovery choices, or trusting the food on their plate, allow your guests to focus on the work. Your guests may not love every meal, but they’ll love not having to choose most of them.

Scale back your own expectations.As a retreat leader, it’s tempting to shoot for the stars for our guests. For solo or friend-group retreats, we make long lists of what we hope to accomplish in our week or weekend away. But too ambitious a goal makes failure inevitable. If I’d been working on “jog around the block,” I’d have spent my days discouraged. Small, daily achievements kept me motivated toward the bigger project.

Figure out where everyone is BEFORE arrival.Finding out on the first day of your retreat that person A is ready for handstands/querying/seven figures and person B needs mindfulness/finished draft/product focus, really screws up your lesson plan. One won’t be challenged; the other might get left behind. Knowing in advance—and checking your notes before daily meetings—lets you confidently usher each person along their retreat path. If you’re actively teaching, include references to specific participants’ goals. Comments like “For Priya, who’s growing her audience, this activity will do X. Sonia, you’re working on individual connections, so focus on Y,” go a long way towards reassuring each guest they’re on the right path—nobody needs to compare themselves to anyone else.

As the leader, narrow your own focus.At my first travel retreat in Tuscany, I made a list of my own writing and work I’d try to get done in my “free time.” Later, I changed the title of the list to “Tasks during retreat HA HA HA.” Release yourself from outside obligations to allow yourself to be fully present for spontaneous discussions or unplanned activities. Often, it’s these unplanned interactions that allow guests to work through their own obstacles. Let any free time be free. (Trust me, you’re going to need a nap.)

Badly led or poorly planned retreats can be physically uncomfortable, emotionally embarrassing, even harmful to the guest’s personal development, and the worst retreat speed bumps usually come from too broad a focus. But small, daily success brings them closer to transformation that they couldn’t have achieved alone.

When planning your own retreat—a group of writing friends, a paid event, or one writer in an AirBnB—narrow the focus and lower your expectations. Last week, it wasn’t my job to make lunch or measure out medication or even wash my own body. Those boundaries let me focus on peeing like a champion. Whether you’re creating business growth plans, raising yoga levels, deepening spirituality or writing books, providing small, achievable steps lets your retreat participants feel that what they’ve done matters. Who they are has changed on a fundamental level. With your retreat, they’ve achieved transcendence.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, consider joining Allison on Saturday, Feb. 4 for the online intensive, Create Live or Virtual Retreats That Sell.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1885 followers