Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 48

May 23, 2023

When Your Publisher Gets the Cover Wrong—Very Wrong

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

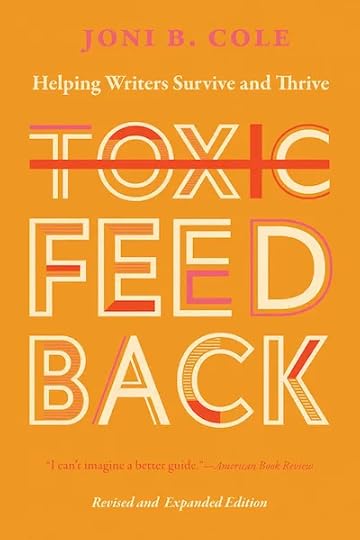

Photo by Annie Spratt on UnsplashToday’s post is excerpted from the new revised edition of Toxic Feedback: Helping Writers Survive and Thrive by Joni B. Cole (@JoniBCole)

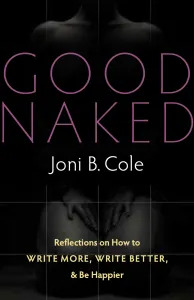

This story starts about eight years ago, with the arrival of a much anticipated email from the publishing house where the first edition of my book, Good Naked: How to Write More, Write Better, and Be Happier, was in production. Wrote the marketing coordinator:

Dear Joni,

Attached is the final version of the cover design for Good Naked, which the designer has asked me to pass along to you. Please note that the white gridlines are watermarks that won’t be present in the finished product…

Even now, years later, I get aftershocks thinking about the first time I opened the attachment and saw that cover design. There, filling my screen, was the image of a naked woman’s body, full-frontal, lingering in the shadows against a smoky backdrop. She was cut off from the neck up and knees down. Against the dark backdrop, two pink circles (representing the Os in the book’s title) drew the eye to the woman’s breasts. Her slender fingers formed a V, framing her pubis. And just below her private parts, spread across her silken thighs, was my book’s subtitle—How to Write More, Write Better, and Be Happier.

In summary, the proposed cover for my book—a cheerful and practical writing guide based on my decades of experience as an author and teacher—depicted a nude, headless woman, beckoning book browsers from the shadows like a back-alley sex worker.

Here, I feel compelled to state that I have nothing against back-alley sex workers. I also will concede that, yes, my writing guide has the word “naked” in its title, but so do a lot of other books, like Naked Statistics, which has a pie chart on its cover. So, when the designer saw the title of my manuscript, what made him think of soft porn? Why did he design a cover better suited to an entirely different type of book, say Fifty Shades of Writing?

I reread the email to make sure I had not misunderstood.

Final version of the cover…Please note that the white gridlines…

Could the marketing coordinator who had written this email to me be any more misguided? How could she think that a few barely perceptible gridlines on the enclosed image would be my primary concern, when there was my name—Joni B. Cole—attached to a work suggesting much more for sale than writing advice?

This story comes to mind as I think about feedback during the publishing process. In this situation, I, the author, was the one tasked with providing feedback, despite being told the cover design was “final” and despite my fear of consequences. I worried that my book was already on a tight production schedule. Could the designer refuse to make changes? If I refused his refusal, could the publisher delay my book’s release, or even pull it from their list? Would I end up blacklisted from the industry, a note on my file listing me as unpleasant, uncooperative, and unwilling to do nudity?

All sorts of worries, real and irrational, cluttered my thinking. But, given the situation, I felt like I had no choice but to reject this cover wholesale. I imagined my new release displayed in the creative-writing section of my daughter’s college bookstore. (And she thought I had embarrassed her in the past!) For moral support, I showed the cover to a few friends, seeking their reactions:

“Is this a joke?”

“Whoa! I thought maybe you’d been exaggerating.”

“Is it me, or is that woman about to get busy with herself?”

The only positive comment about the cover came from my friend Dan. “It’s not that bad,” he shrugged. “Maybe it will sell some books.”

Yeah, right, I thought, and maybe people will assume those are my silken thighs. But that doesn’t make it right.

My friend Dan did make a valid point. Helping a book sell is indeed one of the main considerations when designing its cover. Depending on your publishing contract, you may not have much, or any, say in the final design, and that isn’t completely unreasonable.

Few authors double as designers. Our forte is plot points, not graphic concepts. We may be too wedded to our own artistic sensibilities, right down to our favorite colors. (That dusty rose looked so nice on my bridesmaids’ dresses.) Meanwhile, we aren’t thinking about the big stuff that professional cover designers know to consider. Stuff like, What is in tune with your book’s tone and audience? What is most likely to draw a browser’s attention? What is on trend? Is the type readable from a distance? Is the cover going to work when it is in the form of a one-inch-high icon on Amazon?

In short, if you do have a say in the final design of your cover, just be sure to carefully weigh your tastes against the designer’s eye and marketing expertise. What looks good on your wall won’t necessarily look good on your cover. Also, be aware that you may not love your cover at first sight, but in the end you have to ask yourself whether you will be proud of putting it out there. Remember, people actually do judge a book by its cover, so you don’t want to get in the way of having your new release make a great first impression.

You also don’t want to be one of those authors. My friends who work in publishing have told me stories—oh, how they have told me stories. The following is just one of them. An author of a scholarly book received a cover whose image was one of her choosing, but she was so unhappy about the other elements (apparently the color of the subtitle made her “vomit”) she spammed the designer, the art production manager, the managing editor, the director of the press, and even the CFO. The one person she couldn’t immediately harass was her editor, who was away at a week-long conference. The press director called the editor and told her to “rein in her author,” which was no small task. In the end, almost everyone at the press stopped taking this author’s calls, and while the cover issue was eventually resolved, the author chose to communicate solely with the managing editor after that point.

While much of this chapter has dealt with feedback related to your book’s cover, typically this is the issue (as well as your book’s interior design) where you may have the least input, depending on your contract. Almost every other step of the publishing process, however, invites two-way feedback as you work with your developmental editor, your copy editor, and the marketing team.

As noted in another chapter in this book, it is important to speak up if you truly disagree with, say, your developmental editor’s suggestion to drop the first three chapters. But before you react or overreact, just keep this in mind: My gawd, you are working with a real, live professional editor! (And, trust me, if your real, live professional editor is bored by your opening, your readers are likely to feel the same.) Also, I would not recommend crossing your copy editor, not unless you are the kind of person who knows the past tense of the verb forsake, all 430 uses of the word set, and whether this is the correct spelling of Kyrgyzstan.

All this to say, don’t fail to put your foot down when necessary, but also listen, really listen to the professionals. Be open to their advice, and carry that open-mindedness through every step of the publishing process, from the finalization of the manuscript, through the production of the actual book, through sales and promotion. There is feedback … and then there is feedback from people who make their living publishing dozens and dozens of books a year.

“Trust the process,” as one of my editors once said to me. “The author-publisher relationship is not a competition. It’s a partnership, a dynamic. The publisher is invested financially,” she reminded me, “so they want your book to succeed in every way possible.”

And here I had assumed she’d been working so hard on my manuscript simply because she was my friend.

EpilogueIn case you are curious about what happened to that naked woman on the “final” cover of my writing guide, here is the rest of the story. As soon as I saw that image, I called my editor in a state of high dudgeon. As it turns out, he shared my low opinion of the cover choice, but the designer had voted him down. “Don’t sweat it for now,” my editor told me. “Marketing is on your side as well.” This begged the question: Who was this designer with such sway he could override both my editor and the folks in marketing?

Weeks passed. My print date drew near. Each time I checked in on my sex worker, I was told that the designer remained reluctant to remove her from my cover. As a seasoned author, I am not afraid to speak my mind, but I am also not big on ultimatums. “Replace that cover—or me and my book are walking!” For me, it still feels like a miracle when a publisher accepts my work. It was unfathomable to think I would do anything to jeopardize my “forthcoming release,” two words I love dropping into every conversation. But I just couldn’t accept that cover. This felt bigger than a battle over design. This had the stink of misogyny.

Finally, I got word. Fifty Shades of Writing was no more—I would see a new cover option for Good Naked by the end of the day. This news came in the form of an email from the same marketing coordinator who, weeks earlier, had sent along the original design. In this message she wrote:

Dear Joni,

I’m sorry for your sleepless nights…I don’t know whether I should be putting this in writing, but in all my time here, I don’t think I’ve ever been this opposed to a cover design. I’m rather ashamed that I knuckled under and sent it to you anyway, and I can only imagine how you must have felt.

Later that afternoon the designer put together an alternative with the image of a fountain pen beside a notepad, similar to the clip art used in dozens of writing-related blogs and a far cry from capturing the energy and tone of my book. In forwarding this iteration, the marketing coordinator had failed to delete the designer’s email to her, which I am sure was not intended for my eyes—“See if she’ll like this one,” he had written, as if I were some diva with an endless list of ludicrous demands—No, I said blue M&Ms! Not green! Not red! Blue!

Given I felt my cover deserved more than clip art, I hired an outside graphic designer to submit a different concept. The publisher ultimately chose this cover option for my book, though I heard through the grapevine that the Fifty Shades of Writing designer didn’t like it. (Perhaps he was distracted by the white gridlines?) So, all’s well that ends well, though this story has one more chapter.

Amazon • Bookshop

Amazon • BookshopAbout a year after the release of Good Naked, the publishing house went under, which was a real blow not just because it orphaned my book, but because of all the talented and lovely people who worked at the press, and all the meaningful titles it had released to the world for almost fifty years. I was lucky to find my own happy ending, however, as Good Naked was picked up by a different publisher that invited me to create a second edition. Oh, and it was love at first sight when they showed me their revised version of the cover!

Now, in my better moments, when I think about that designer with whom I so fervently disagreed, I try to let bygones be bygones. I hope that he found employment at some other publishing house, assuming he is no longer living out his male fantasies on the covers of other authors’ new releases. But if the challenge of my own cover struggle has taught me anything, it is this: There is good naked, and there is bad naked, but only one of those can help you write more, write better, and be happier, and it is not the one that has anything to do with soft porn.

May 22, 2023

How to Write Nonfiction When You’re Not an “Expert”

Photo by Darina Belonogova

Photo by Darina BelonogovaToday’s guest post is by book coach and editor Liz Green. Join us on May 31 for Memoir or Self-Help?

Worried you’re not enough of an expert to write your book? That’s OK. You don’t need to be the annoying expert who knows it all. There’s another—far more effective—approach you can take when talking to readers.

Let’s start here: What do you think I want from you? What do any of us want from any interaction with another human being?

Entertainment. Information. Compassion.

Right? Think about it.

What are you looking for when you have a chit-chat with your partner in the kitchen, or get talking to a new acquaintance at one of those awkward networking sessions, or sit down next to Auntie Edna at your cousin’s daughter’s wedding?

I bet you do NOT want to hear Auntie Edna brag about how her kids are sooooooo great, so accomplished, and so much better than your kids.

Cut it out, Auntie Edna.

In your book, no one wants to hear how you’re the be-all, bestest-ever, super-dooper, way-better-than-them savior of humankind. It’s as annoying as Auntie Edna after a glass-and-a-half of chardonnay.

Readers DO want assurance you know what you’re talking about, and they wanna sense they can trust you. But you don’t have to brag about being the best for that.

A much more effective route is to entertain, inform, and show compassion.

Imagine Auntie Edna polishing off her second glass of wine at the wedding reception, and leaning in to share some juicy stories about your cousin’s escapades at his new job, then quietly informing you of her daughter’s impending divorce (so you don’t put your foot in it by asking how the hubby is). Picture her gently asking how you’re feeling after those rough few months you’ve had, while she tops up your own wine glass.

How do you feel about Auntie Edna now? We like her better, right?

Bucketloads of humanityRather than being “expert enough,” you need to know enough about your subject to write about it honestly and insightfully. And beyond that?

You need to be human.

Entertaining.

Informative.

Compassionate.

I assume that even without being “an expert,” you still have something to say—something you suspect others will benefit from. So share that with bucketloads of humanity, and you’ll be just fine.

This approach will shift your book from:

“Do this! Then do that! Listen to the expert!”

to

“Let’s have a chat. I want to share something with you.”

It shifts it down the spectrum from strict self-help to being a little (or a lot) more memoir-y. Conversational. Story sharing.

The brilliant thing is you get to choose how far down the spectrum you go. You can choose to position yourself:

As the authority standing on stage, giving an epic, powerful talk.As the admired teacher in a small classroom setting, guiding students by the hand.As the trusted friend sitting at the dining table, chatting over a cup of tea and whispering heartfelt advice.Or anywhere in between.

Note from Jane: If you want to learn more about the spectrum of self-help to memoir and how to choose where your book will sit on that sliding scale, join us for on May 31 for Memoir or Self-Help? (Recorded if you can’t make it live.)

May 18, 2023

First Pages Critique: Reduce Repetition to Better Seed the Mystery

Photo by Valeriia Miller

Photo by Valeriia MillerAsk the Editor is a column for your questions about the editing process and editors themselves. It also features first-page critiques. Want to be considered? Submit your question or submit your pages.

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Book Pipeline. The 2023 Book Pipeline Unpublished contest awards $20,000 for unpublished manuscripts across 8 categories of fiction and nonfiction. Over the past year, multiple authors have signed with top lit agents and gotten published. Register by May 25.

A summary of the work being critiqued

A summary of the work being critiquedTitle: Return to the Auberge

Genre: mystery/thriller/crime

We’re all a surrogate for someone. Emyla’s twin sister died at age six and now Emyla avoids mirrors. When she reluctantly revisits the French auberge where she worked twenty-two years earlier, she is forced to face not only her tragic memories of the Fleury family who once owned it, but her guilt surrounding her sister’s death. Layers of the past gradually invade the present, until Emyla is forced to decide once and for all to either bury her guilt, or tackle it head on.

First page of Return to the Auberge“I’m not going.”

That was Dr Emyla Brace’s response, yesterday, to her brother’s final attempt to force on her an all-expenses-paid week in the South of France.

And she’d meant it.

So why in hell was she sitting in her Clio outside Alastair’s fancy North Oxford apartment at the soaking crack of dawn, poised to risk her life speeding to Heathrow because her brother couldn’t drag himself out of bed?

Cockroaches. That was why. Or her father’s ultimatum? Maybe a bit of both.

The end of the British summer hammered on the windscreen, mimicking Emyla’s percussive fingers on the steering wheel. She glanced at the dashboard clock: 06:10.

Six on the dot. Right. Why wasn’t Al ever on time?

Pulling her coat tighter, she peered through the rain and dark at the porticoed entrance. At the empty space where he should have been standing ten minutes ago. She grabbed her mobile from its holder and tapped the screen. On the voicemail prompt, she hissed, “Wake up, lazy sod!”

Continue reading the first pages.

Dear Debbie,Thank you for submitting your work. Your story about dealing with the death of a twin is very intriguing, and it reminds me of two recently published novels that take on this same topic: Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet (2020) and Kamila Shamsie’s Home Fire (2017). My recollection of Hamnet, however, is that it focuses on the parents’ grief and how it influences Shakespeare to write “Hamlet.” Home Fire, from what I have heard, is more about burial rites than about loss, much like the play it reimagines, Sophocles’ “Antigone.”

In any case, both these books are considered literary fiction rather than mystery/thriller/crime, as you’ve categorized Return to the Auberge. In some ways, your novel is reminiscent of Agatha Christie’s The Mystery of the Blue Train in that the characters, like Emyla and Alastair, travel from London to the South of France. But as in all of Christie’s books, the emphasis is on who committed the crime, while your novel looks to be more of a character-driven mystery. And what a unique and accomplished main character it features in Dr. Emyla Brace!

Your premise—that Emyla must decide to either bury her guilt regarding her twin sister’s death or tackle it head on—is also impressive. However, I didn’t quite see a mention of her sister, direct or indirect, in these opening pages. It’s possible that Emyla’s and Alistair’s sister will be referenced in upcoming pages, whether during their flight to France or once they arrive there, but I would recommend somehow alluding to her from the get-go. Possibly Emyla recalls a memory about her sister as she is waiting for Alastair. Maybe the trees lining Alistair’s street—or a park Emyla sees in the distance—remind Emyla of where she and her sister used to play when they were little. Or perhaps when Emyla notices the porticoed entrance to Alastair’s building, a deep-seated memory about the last place Emyla saw her sister alive suddenly surfaces? To avoid making the reference to her twin too heavy-handed, Emyla might quickly brush away thoughts of her, suggesting that they are too painful to deal with.

The mystery elements might also be emphasized. The rain certainly gives the story an eerie tone, but currently it comes up several times, not only by means of the (wonderfully vivid) phrases “soaking crack of dawn” and “drizzly charcoal dawn,” but also via the hammering and drizzling on Emyla’s windshield, the puddles Alistair steps through, his waterproof jacket, and three direct mentions of the word “rain.”

In place of some of these lines, you might focus on the moment Emyla notices blood on her finger, which further adds to the eeriness of the story. The line, “Some blood wipes off easily…It doesn’t stick to you, seeping through your skin, merging with your own until you no longer know where it ends and yours begins” is thought-provoking since Emyla seems to be referring to something dark that has nothing to do with the prick on her finger. In place of “’Em! Huh? Airport. Right…’” which might be too casual a dialogue exchange to follow Emyla’s comment, could Alistair try to guess what Emyla means? Or could Emyla mutter “never mind” because she realizes she’s said too much?

On a more practical note, you might better explain how and when Emyla injures herself. If it’s when she puts her phone back in its holder, is this because the plastic holder is broken? The passage in which Emyla tells Alistair that her father is disowning her also creates excellent suspense, as does “the familiar tightening of her chest muscles,” so these lines might warrant elaboration as well. Maybe Emyla experienced this same feeling when her sister died? And her father also threatened to disown her back then, or so she assumed?

In addition, it would be ideal if you could allude to the book’s title in the opening pages. If Emyla worked at the auberge at age 18 and her sister died when they were six, then it’s unlikely that her sister died there. But according to your pitch, it sounds like there’s a link between her sister’s death and the Fleury family that once owned the auberge. Is there a way to shed some light on what it is without giving away too many details? If not, is it possible to hint at how Emyla’s twin died? If, for example, she drowned, then maybe Emyla dreads all bodies of water, including puddles, and feels anxious when Alistair pulls his suitcase through them. (That said, if she avoids mirrors, as per your pitch, then shouldn’t she look away—rather than describe her hair length and color—the second she catches a glimpse of her reflection in the window? Alistair can always be her “mirror” and tell her how she looks once he gets in the car.)

Alternatively, if her sister died of an illness, could Emyla briefly reflect on the fact that she went into medicine to find a cure for the disease that took her sister’s life? (That said, is Emyla a surgeon or a GP—better known as a PCP, or primary care physician, here in the US? Both specialties are mentioned.)

The question you might be asking is how you will be able to pack all this information into the opening pages without overloading them with backstory, and the answer is that it will be tricky, but it can be done! You might start by toning down repetitive details, not just the rain but also Emyla’s resentment of Alistair’s tardiness. It’s one thing that she tells him he’s late, but maybe she doesn’t also need to leave him a voicemail saying, “Wake up, lazy sod!”

And unless Mrs. Pratchett turns out to have witnessed Emyla’s sister’s death or has something to do with the Fleury family, maybe her frustration with the early morning noise can be skipped as well? Some of the pop culture references might also be reconsidered, such as Emyla’s Bon Jovi posters and her mention of Erik Erikson and Eric Morecambe. Although I’m a fan of Bon Jovi as well, I’m not convinced that Emyla’s musical tastes as a teen matter at this point in the story. And not all readers—this one included—will have heard of Erikson and Morecambe.

This is not to suggest that all cultural references must be universal, but other aspects of the story might take priority, namely Emyla’s guilt about her sister. She expresses her guilt about the trip—that it’s “her fault” because “if she hadn’t turned forty, [Alistair] wouldn’t be generously forcing lavish holidays on his big sister.” But as a grown woman, wouldn’t Emyla know that she can’t control her age or the gifts she’s given? What if, instead, Emyla worries that she will be blamed if she and Alistair miss their flight, just as she (believes she) is blamed for everything?

To reiterate, your premise about the loss of a twin is fantastic. So too is your setting in that there’s an evergreen interest in novels set in France. And while the opening to your story is a pleasure to read, it would be even more compelling if it set the stage for the mystery regarding how Emyla’s twin died and why she feels guilty. Now it’s a question of making sure this comes through at the very beginning of your book.

Thank you again for submitting your first pages for review. I hope these comments are helpful!

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Book Pipeline. The 2023 Book Pipeline Unpublished contest awards $20,000 for unpublished manuscripts across 8 categories of fiction and nonfiction. Over the past year, multiple authors have signed with top lit agents and gotten published. Register by May 25th.

May 17, 2023

Harnessing the Power of TikTok: From Self-Published to Traditionally Published Author

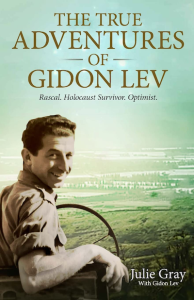

Todays post is by author and editor Julie Gray.

As a writer and a developmental editor, I experience the same highs and lows as the writers I work with. Trying to get an agent and a book deal seems like looking for a needle in a haystack. It’s easy and understandable to get frustrated and give up. Likewise, publishing independently sounds like a confusing marathon without any guarantee of actual sales.

In 2019, I queried agents with my manuscript, The True Adventures of Gidon Lev: Rascal. Holocaust Survivor. Optimist. The manuscript is unusual, and I knew pitching it would be difficult. It’s a book about writing a book about a Holocaust survivor. In other words, I used a meta-narrative to frame and contextualize Gidon’s life story and memories.

I was right; my queries were not successful. After a few months, I gave up. The book’s subject, Gidon, was 83 years old at the time. I decided to publish the book independently so that Gidon’s dream would come true while he could enjoy it. That was in 2020, during the pandemic. Gidon got the book he is so proud of, and to my delight, the book got a starred review in Kirkus and was included in their best nonfiction of 2020 list. It also won an Indie Reader award.

The process of publishing the book independently was an invaluable education for me; I learned every step along the way, from uploading to learning about keywords to getting blurbs and more. I’m really glad I did it. The book sold modestly, but that was okay; Gidon was happy, and I was (and am) also proud of the book and the awards it won.

About a year after the book came out, on a whim, Gidon and I decided to try TikTok. We had no idea what we were doing but figured that #booktok could help us sell more copies. And it did at first. But slowly, our account shifted away from the book toward Holocaust education in general. Today, we have almost half a million followers. Gidon became a TikTok sensation. With a platform like ours, maybe now a literary agent would be interested in the book—even though it was already out as a self-published book.

The accepted wisdom is that it is tough and exceedingly rare for an indie writer to cross into traditional publishing. Who hasn’t heard the extraordinary story of Hugh Howey, whose “Silo” is now airing on Apple TV+ (it’s great, by the way!). There is also the story of Andy Weir, whose book The Martian started as chapters on his website and became available on Amazon for 99 cents. The rest is history. And there are others, too. So–it is possible–but I did not have massive book sales as leverage. But I did have half a million people on TikTok who loved Gidon.

I decided to give querying a shot. What did I have to lose?

I wrote a query letter that started off by acknowledging upfront that my query was unusual. I told the story of the book and its trajectory and, of course, included the surprising phenomenon of TikTok and the resultant media coverage of Gidon. I kept it to one page and hit send eighty-four times.

Reader, I got an agent. Very quickly. In fact, our agent replied on the same day that I sent the query. We signed a contract a month later. Now, an entire “team” is working on our project together with us.

Wait—what project? Well. Because our book was published independently and had had some exposure to the public, our agent (and team) decided we should write a proposal for a different book, something that is similar to The True Adventures, but broader in scope, to include Gidon’s life today, as a Holocaust educator on the world’s biggest social media platform. If this second book does well after publication, then we can discuss rereleasing the first book. This was not exactly what I had in mind—but it is an unexpected opportunity.

The story of The True Adventures is unconventional, and I cannot say it has been a big success quite yet. But it is an example of how things can work out in unexpected ways. By having the audacity to query with a book that had already been published independently, I was able to give new life to the project in general. The takeaway for you, dear writer, is that there are many approaches to getting your book out there to readers. It might happen with a manuscript you wrote five years ago, with a new cookbook you decide to write, or because your manuscript wins an award or otherwise gains attention. Don’t give up. Anything is possible.

May 16, 2023

Why Authors Should Ditch Mailchimp and Move to Substack

Photo by RDNE Stock project

Photo by RDNE Stock projectToday’s post is by publisher and author L.L. Barkat (@llbarkat) of Tweetspeak Poetry.

If you’re an author who’s been using Mailchimp to grow your list and improve sales, it might be time to ditch Mailchimp and move to Substack.

This is a big decision. I understand.

After all, as a small publisher, I recently made the decision to move our Every Day Poems publication to Substack, and it took some real work to successfully do so.

Why did I risk relocating a publication that was approaching its twelfth birthday?

Two big reasons I started the ball rollingMailchimp has seriously raised its prices since it was taken over by Intuit and since it has pivoted to be a heavier e-commerce service. Regarding pricing, I asked Mailchimp for a solution that might be appropriate for their customers who are part of the creator economy, and they said, “You could delete subscribers.” That just didn’t seem like a sustainable solution if the goal is growth.One of our T. S. Poetry Press author/illustrators started a few Substacks last fall and immediately built her lists into the thousands (from nothing!); we watched her book sales start climbing. That sales trend has continued for her and for another author of ours who also moved to Substack.The bottom line?

We saw a chance to cut costs and increase sales. What’s not to love.

Beyond that, we want to suggest 5 more reasons you might want to ditch Mailchimp and move to Substack.

5 reasons to make the move1. You can get paid, instead of paying. Substack is technically a subscription service, and while you can offer your newsletter for free, you can also offer it at a minimum of $5 a month or $30 a year. Some people charge more. Sure, you can charge for your Mailchimp newsletter, too, but you have to pay to play. If your lists are in the thousands at Mailchimp, this can become quite pricey.

We went for the 5 & 30 model at two of the Substacks we now run. And while we lost paying subscribers when we made our initial move, the revenue has since tripled. That’s partly because we also added a new offering: The Write to Poetry. It might also be due to Reason # 2 below.

2. You’ll be in an ecosystem instead of a silo. Substack sends your newsletter to inboxes, just like Mailchimp, but it also publishes your content to the Web. This is extremely important for creating an ecosystem instead of a silo. All your free posts are easily likeable and shareable and, if you allow comments, can provide for engagement.

On top of that, the Substack network allows publications to recommend other publications—sort of the way blogs used to have sidebars where they recommended other blogs. If you really hit it big, you might even get recommended by Substack (that happened for us with Every Day Poems, and we picked up a lot of subscribers when it did!)

3. You can have searchable archives instead of invisibility. Substack has excellent SEO, and your archives (even your paid ones, if you toggle to discoverability) are discoverable by search engines. With Mailchimp, there are no archives except in people’s inboxes. Not optimal.

Does it make a difference? Our Substack stats show that it does. We’ve gotten new free and paid subscribers via Google searches that landed people right on our regular content—content that with Mailchimp would not have been findable by search engines.

4. Your signups will be simple instead of requiring design and coding. It’s super easy to grab the embed code for Substack and put it everywhere on your website. Caveat—no pop-ups at this time, like you can with Mailchimp. Still, there is little to do in terms of code and design. You just grab the embed code provided by Substack, right from your dashboard, and signups become as simple as this:

5. You can export your content if you want to leave, versus having your content lost in fragments forever. Nothing lasts for all time, especially on the Internet. If Substack becomes a place you someday leave, you can take your content with you. On Mailchimp, your content is not downloadable and it’s all in separate pieces.

Need more convincing?First, importing your existing Mailchimp list to Substack is easy. You simply drag and drop your CSV list that you download from Mailchimp. With large lists, in the thousands, you might have to wait a day while Substack reviews it.

Second, your posts can go straight to your audience’s inbox, just as with Mailchimp. Or you can choose to post just to the Web.

Finally, when you send a newsletter to subscribers’ inboxes (the content of which also publishes right to the Web), Substack automatically provides media assets you can use to populate your social channels. It helps if you have nice photographs. Here’s a sample:

Tips for success

Tips for success1. Have a clear proposition, as with the best blogs. In fact, if you want to be eligible to get recommended by Substack, they note they are looking for a clear focus.

2. Publish consistently, which is a data-proven key to success. (If you haven’t read Don’t Trust Your Gut, you really need to. One of the most encouraging points is that authors and artists are more likely to become successful by consistently putting work into the world!)

3. Be a little social, even offer just a “heart” or a smile if people comment on your work. (See the introverted Sadbook Collections for an example. It doesn’t take much, which is good news for many writers who get overwhelmed by the prospect of having to be too social online.)

The end of the matterIf you still need the complexity of creating “Customer Journeys,” I suggest you stick with Mailchimp. But remember, you can also hybridize your approach, as we are doing with The Write to Poetry—starting some clientele on Mailchimp and moving them through several customer journeys, before relocating them to Substack.

In the end, this is the question: To ditch, or not to ditch Mailchimp? The signs say Substack might be best for your future.

Note from Jane: I field many questions these days from writers who are wondering if they should move to Substack. I myself do not use it for my blog, my free newsletter (Electric Speed), or my paid newsletter (The Hot Sheet), and I will not be switching. If you are currently happy or satisfied with your website, blog and/or email newsletter, I would not upend everything to move to Substack. Ask yourself if you’re experiencing FOMO (fear of missing out) or if you have a well-thought-out business reason for moving, as L.L. Barkat does. Also keep in mind that Substack is built on VC funding, which means you’re building on shifting sands. What’s here today might not be here tomorrow. Use the platform for your own ends, and know what you’ll do if the service closes or changes in some way that makes it less attractive for you. While I’m glad Substack makes it easy for people to depart with their emails/subscriptions, it can be very painful and time-consuming to find and build a new home base.

May 10, 2023

Why You Should Start Promoting Your Writing Before You’re “Ready”

Today’s post is by author Catherine Baab-Muguira (@CatBaabMuguira).

Years ago, I had a freelance article go viral, or at least modestly viral, racking up over 50,000 Facebook shares. I received my first-ever invitations to appear as a guest on podcasts and even NPR. I also received dozens of friendly and often deeply personal messages from readers, plus a handful of job offers, right out of the blue.

The funniest thing? That piece was published by mistake. It was 2016, and I’d only just begun to freelance for national publications. I emailed a pitch to a certain online publication’s general inbox, AKA its slush pile. Within a few days, an editor got in touch accepting the idea, but then he hated the draft I turned in. It was too essayistic, he said, and I would need to rewrite the piece as a reported story. I turned in a new version a few weeks later, and a long period of radio silence began. I didn’t hear from the editor again until one random, rainy night when I was standing in line at Kroger, waiting for the clerk to drag my Lean Cuisines across the scanner, and my phone pinged with an urgent email.

The piece would be running tomorrow, the editor announced. Could I please review the draft immediately, sign off, and send in a bio?

Still in line at Kroger, I thumbed open the draft, and a thin trickle of terror ran down my back.

The draft he’d attached was the old one—the one he’d hated. I didn’t know whether to mention this or not. By this point, I’d all but given up on any version getting published, period. In the parking lot, I called a friend on the phone, with no preamble, and he advised me to let it ride. Let the piece come out, get the byline, move on.

The next day, I went to check the site for the piece, except I never made it there because my Twitter notifications had blown up, and I had Facebook DMs from radio stations asking if I would come on their shows.

This felt amazing. Exhilarating. Bewildering. In any case, I was so green that I didn’t realize the piece was unusually successful. I thought this level of attention must be what happened every time you write for a larger publication, which is enough to make me laugh now. I’ve never had a piece gain so much traction since. And today, several iterations of the internet later, I honestly wonder if essays even can go viral anymore. Short-form video is so far and away the dominant currency.

The point is: I wasted that viral opportunity in 2016—fully, completely, in the most comprehensive and self-esteem-annihilating sense.

At the time, I did not have an author website. I didn’t have a blog or an email list. All my socials were set to private, and my personal email address took some serious digging to track down. When NPR got in touch, for instance, they had to do it by Facebook DM, and the message went to my junk inbox, which means I almost missed the chance to do an hour of national media. Oof.

Why didn’t I have a basic online presence in place?I expect the answer is obvious: I was worried what people might think. It was such early days. I’d barely published. What if my old college friends saw me taking myself seriously, how cringe would that be? What if my coworkers or neighbors saw I’d made a website for myself, wouldn’t I seem deluded? Bless her heart, I imagined them saying. How important does she think she is? Look at her spending actual time on LinkedIn!

And so when the chance came to start building a real, meaningful following, I missed it. In my effort to appear nonchalant—which probably wasn’t convincing anyone, anyway—I guaranteed that I would derive as little benefit as possible from publishing articles, from all the work involved, and from all the time and angst it cost me.

Fast forward to 2018, when I was attempting to sell a nonfiction book proposal, and all I could do was tell publishers the piece had hit. I couldn’t speak of an email list, or a Twitter following, or an Instagram account, full stop, much less Instagram followers.

Not coincidentally, my proposal kept getting rejected. One rejection from a major publisher specifically cited my Twitter follower count, still a mere three digits. When I complained to a bestselling friend, he gave it to me straight: “If you’d gotten serious about building a following years ago, you wouldn’t be in this position now,” he said. And he was right.

Are you making the same mistake I did?You may be just starting to publish. Or maybe you’re even earlier in the process, and only beginning to think about dipping your toe in that icy pond. I hope you won’t let self-consciousness prevent you from putting some basics in place. What if your early efforts catch fire, and you don’t have a system for capturing that momentum? I’m mixing metaphors here, but far more importantly, you could be positioning yourself to miss out on any support or interest that comes your way, whether huge or modest.

If your goal is to have a writing career one day, then you should probably have a basic website today. You should probably have your email address listed prominently somewhere, in your social bios, your Linktree, what have you. Unless you’re Sleeping with the Enemy, you want to be easy to find, easy to contact. Set up a mailing list whether you have immediate plans to put out a newsletter or not. Seriously, I’m begging you. Learn from my mistake, friends! Save yourselves! I was an idiot, focusing on the wrong things! You don’t have to be!

Even a mailing list of 84 people—and all of them your sorority sisters or second cousins—is better than no mailing list at all. A modest following plus a clearly identifiable audience for your book can get you a deal. In fact, that’s how it eventually happened for me. Besides, who cares if your earliest self-promotional efforts are cringe? This year is the official Year of Cringe, even of meta-cringe. Chances are real good, anyway, that your frenemies are too preoccupied by their own neuroses to notice what you’re doing, and if they’re not? So be it. Everybody is somebody’s hate-read. You’re nobody till somebody hate-reads you.

Building an author platform is a long, hard road, or one of those epic train journeys in Agatha Christie during which someone’s definitely going to get murdered, maybe you. Best get it over with. Best start now, right away, no matter how rough your memoir draft is, no matter if your novel is only 163 words long as of 5 a.m. this morning. You don’t want to miss out on any popularity (or notoriety) you may happen to generate on purpose or by accident. Also, you’re going to need those PR, marketing, presence-building skills to sell your eventual book to readers, so it’s best to start gaining them ASAP.

Is all this a drag and a pain? Oh yes, absolutely. I hate it. I am thinking but not typing the curse words I would use to describe it if we were talking face to face. Sadly, no writer is allowed to remain anonymous like Pynchon, or gets to live the rural-recluse life like J.D. Salinger, not anymore. Which is a shame because I hear New Hampshire is beautiful this time of year. I bet it’s lovely there right now. I’ll never know.

May 9, 2023

Using ChatGPT for Book Research? Take Exceeding Care

Photo by Jason Tuinstra on Unsplash

Photo by Jason Tuinstra on UnsplashToday’s post is by author and book coach Susanne Dunlap (@susanne_dunlap).

WARNING: Research Rabbit Hole Ahead

I do a lot of research for my historical novels, so I’m interested in knowing about anything that might make that process faster or easier for me. And honestly, I’m curious about ChatGPT in general. So I thought I’d put the app to the test against my usual internet searches and see how it measured up.

Before I get into what I discovered in the course of my experimentation, it’s worth noting that the ChatGPT search window says, “Free Research Preview. ChatGPT may produce inaccurate information about people, places, or facts.” This is important to bear in mind in any research—even in primary sources, where you can easily find conflicting information.

I started by asking questions related to my work in progress.My dual-timeline manuscript takes place in a mill town in Maine at two different times during the 20th century. One key location is the Biddeford Opera House, which was opened in the late 19th century and still exists as Biddeford City Theatre.

I had so many questions about what the venue was like and what shows were mounted there during my two timelines, but I decided to start with the basics.

Question: What is the History of the Biddeford Opera House in Maine?

Google turned up “About 1,470,000 results (0.61 seconds).” The first five results were for Biddeford City Theatre, listing its programs and so on. At the bottom of the page, there were links to some historical information on the Maine Memory Network (great site). I clicked over to that site and found some fascinating pictures, but no history.

Not very impressed with these results, I went over to the conversation starting point in ChatGPT and typed the same question.

In seconds, it came up with a pretty decent potted history that mentioned Sarah Bernhardt, Enrico Caruso, and John Philip Sousa performed in the opera house—something I hadn’t seen in my previous limited research.

Encouraged by this, I decided to get still more specific and ask, “When did Caruso perform at the Biddeford Opera House?” To which ChatGPT answered:

Enrico Caruso, one of the most famous opera singers of all time, performed at the Biddeford Opera House in Biddeford, Maine, on October 22, 1909. Caruso was at the peak of his career at that time, having achieved international fame for his powerful tenor voice and his performances in operas such as “La Bohème,” “Carmen,” and “Pagliacci.”

I tried posing the same question in Google and was still served a dizzying array of more or less relevant results, none of which actually looked like an answer to my question.

Verify, verify.Mindful that ChatGPT can give false information, I set about trying to dig deeper on the web and find more evidence for Caruso’s appearance in Biddeford. I started with the history section of the theatre’s website, which was quite brief. It did not mention Caruso. So I dug still more and discovered that although I couldn’t find other evidence that the famous tenor had performed in the theatre, he was indeed in the US in 1909.

Since I had a specific date to search—thanks to ChatGPT—I went to the web again, and asked the question, “Was Caruso in New England in 1909?”

The first result was the Wikipedia page, as it often is. With such well-known figures, Wikipedia isn’t a bad place to start, because chances are many knowledgeable people have contributed to the page. However, Caruso’s page was one that said, “This article needs additional citations for verification”—suggesting that whatever I found might not, in fact, be any more reliable than ChatGPT.

Even so, I was happy to read this:

In addition to his regular New York engagements, Caruso gave recitals and operatic performances in a large number of cities across the United States and sang in Canada.

But that wasn’t quite enough to be conclusive, so, with the detailed information I got from ChatGPT, I went further through search results on Google. Still nothing. So I widened my search a little and asked about Caruso’s 1909 US tour.

And eureka! The first result was the Library of Congress Research Guide. If I couldn’t trust that, what else could I trust? Off I went down that rabbit hole.

About a half hour later, I found Caruso named in a couple of editions of the Kennebec Journal from Augusta, Maine, notably on October 22, 1909. However, close examination revealed that the name was in an advertisement for a merchant on Congress Street in Portland—an ad for the Auxetophone, an early sound-amplification device. The merchant in the newspaper said that the recorded voices of a number of famous singers, Caruso among them, would be featured in a concert on that date. Nothing said anything about a tour or a live performance.

Was that the source of ChatGPT’s assertion? Possibly. But I wasn’t ready to give up yet.

My next step was to wring yet more information about this possible performance from ChatGPT. I asked what Caruso performed in that concert it mentioned. The response was remarkably detailed:

Enrico Caruso performed at the Biddeford Opera House on November 25, 1909. According to historical records and newspaper accounts, Caruso performed a variety of arias and songs during his performance, including several of his signature pieces such as “Vesti la giubba” from the opera “Pagliacci” and “Una furtiva lagrima” from the opera “L’elisir d’amore”.

Caruso was accompanied by the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, and the performance was reportedly very well received by the audience. According to one newspaper account of the performance, Caruso received several standing ovations and was forced to give several encores before the audience would let him leave the stage.

Overall, Caruso’s performance at the Biddeford Opera House in 1909 was a significant event in the history of the theater and remains an important moment in the history of opera in Maine.

It sounds pretty convincing, right? Note, however, that it gives a different date for his performance than in the answer to the original question, suggesting that ChatGPT might have gotten “confused” by the October newspaper article.

Back I went to Google to search this more detailed question with a date. Google simply said,

It looks like there aren’t many great matches for your search. Try using words that might appear on the page you’re looking for. For example, “cake recipes” instead of “how to make a cake.”

Ah, Google…

What’s encouraging about ChatGPT’s answer, whether or not it’s accurate, is that it provides yet more avenues to explore for information. Perhaps the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra archives would have records that verify this, for instance.

(I didn’t go check that out for this article.)

Check and double-check, backwards and forwardsWhile I was on the theatre’s website, I read that the building had burned down in 1894 and been rebuilt. That was something ChatGPT did not mention in any of its answers to my initial questions.

When I asked the bot specifically whether there had ever been a fire in the theatre, it said no.

Hmmm.

Then I got a little more detailed in my question and asked whether there had been a fire in 1894. To which it answered:

The Biddeford Opera House, also known as the City Opera House, did experience a major fire in 1894. The fire broke out on the night of January 26, 1894, during a performance of a play called “The Two Orphans.” The fire started in the backstage area and quickly spread throughout the building. Despite the efforts of firefighters and volunteers, the building was completely destroyed.

I’m mystified as to what led to a different answer in this case, but it only demonstrates that you’re dealing with a bot, not a person. Be that as it may, ChatGPT’s answer is more detailed than what is on the theatre website, which gave neither the exact date nor the name of the play being performed.

Asking Google the same question, I got scraps of corroborating information that basically parroted the theatre’s website.

How reliable are many sources on the web?Another of the factoids on the Biddeford City Theatre website that wasn’t in any of ChatGPT’s results was that a young actress, Eva Gray, died in the opera house after a performance in 1904. I decided to see what ChatGPT had to say about that specifically.

Here’s what came up:

There is a widely circulated story that Eva Gray, a young actress, died on stage during a performance at the Biddeford Opera House in 1904. However, there is no evidence to support this claim, and it is likely a myth or legend.

Research into historical records and newspaper accounts from the time has failed to turn up any evidence of an actress named Eva Gray performing at the Biddeford Opera House in 1904, let alone dying on stage during a performance.

It at least sounds as though resources have been combed through. And I’ve also asked ChatGPT other research questions that it admits having no answer for, instead suggesting other avenues to explore—which to me gives a little more weight to its results.

The bottom lineI still don’t have absolute proof that Caruso’s concert at the Biddeford Opera House sometime in the fall of 1909 took place. But I think there’s enough evidence available to assume that it might easily have done so. While that wouldn’t be enough for a scholarly paper, it’s certainly adequate for the verisimilitude required of historical fiction. (Note: I have emailed the management at the present-day theatre to see if they have archives I could consult.)

The examples above are limited, but I think they offer a taste of how embracing AI for the purpose of historical research is something authors should consider. It’s not a replacement for what we’ve always done, just another useful tool. You can’t base your research on a single source anyway. We might as well learn all we can about this technology because it’s not going away. After all, knowledge is power.

And when I asked ChatGPT who first said that, this was the response:

The phrase “Knowledge is Power” is often attributed to the English philosopher and statesman Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626), who is known for his influential works on science, philosophy, and politics. However, the exact origin of the phrase is uncertain, and similar expressions can be found in the writings of earlier philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. Nonetheless, Bacon’s use of the phrase in his work “Meditationes Sacrae” (1597) and “Novum Organum” (1620) helped popularize the idea that knowledge and learning are valuable sources of power and progress.

Need I say more?

May 5, 2023

The Fascinating Neuroscience of Scene

Today’s post is by regular contributor Susan DeFreitas (@manzanitafire), an award-winning author, editor, and book coach. Join us on May 11 for the online class Your Novel’s 4 Key Scenes.

There are two fundamental modes in fictional storytelling: summary and scene.

Summary is the storyteller’s voice—the one that leads us skillfully through the story, collapsing and condensing time as necessary in order leave out the irrelevant bits, and tell us what we need to know, in terms of background info on the story.

Scene is the story itself, unfolding in real time. In scene, we’re not listening as someone tells us a story, narrating a series of events—we’re actually living the events of that story for ourselves.

Summary is important, and it’s a tool that hearkens back to the very roots of storytelling. But to my mind, scene is where the real magic happens in fiction.

Scene is important first because it operates on the body of the reader, convincing them on a subconscious level that they’re actually there, in the world of the story, with all of their senses engaged. To my mind, this is what novelist John Gardner was talking about when he said that effective fiction creates a “vivid and continuous dream” in the reader’s mind.

And second, scene is important because it is the most memorable way to share information with your reader. This makes it a critical tool for establishing backstory, revealing character, establishing and advancing conflict, and revealing critical information about the plot.

Skillful storytellers often seem to grasp this intuitively. But why, exactly, does scene work this way? The answer appears to lie in the study of neuroscience.

Scene and Mirror NeuronsConsider the following:

Susan took a sip of her chai, which had gone cold in the time it took her to write the introduction to her post for Jane. Carefully, she set the sturdy earthenware mug back on the table beside her, and tucked the warm blanket back under her feet. It was a cold night, and the spring wind of the high desert was bringing in late-season snow.

According to neuroscience, as you read the passage above—if you were paying attention and involved with what you were reading—the same parts of your brain lit up as if you yourself had been placing that heavy earthenware mug back on the table and gathering that blanket around yourself on a cold night. We know this because we’ve hooked people up to functional MRI machines and then watched which parts of their brains indicated neural activity as they read passages like this.

That means, as far as your brain is concerned, there’s very little difference between reading about someone doing something and actually doing it yourself.

This is based on the action of something called mirror neurons—a special class of brain cells that fire not only when an individual performs an action, but also when the individual observes someone else perform that action. Meaning that when we watch someone reach for their heavy earthenware mug full of tea, our brains precisely model what it would feel like to do the same thing ourselves.

And just as fascinating is the fact that these same sort of simulated actions and experiences appear to show up in our brains when we’re dreaming. Which has led some researchers to speculate that scenes in fiction appear to actually use this preexisting function of the brain, which not only mirrors little bits and pieces of actions we observe in others but actually strings together simulated actions and experiences into a continuous and convincing virtual reality experience.

Scene and Episodic MemoryAccording to neuroscience, we have two different types of memory: semantic and episodic.

Semantic memory is where you store everything you read in school about the history of the Civil War, or the process by which a bill becomes a law, or what have you. You do your best to cram that info into your brain, so that info will be there when it comes time to take the test.

But after the test? It’s use it or lose it. Meaning, if you have no further occasion to use this information—in conversation, say, or at work, or as a contestant on Jeopardy! (my lifelong dream, BTW, as a former high school Quiz Bowl nerd)—your brain will divest itself of all this info you so painstakingly crammed into your semantic memory.

Episodic memory is much stickier.

Let’s say you studied the Second World War in third grade. You may have completely forgotten that the Battle of the Bulge occurred in late 1944 and why it marked a critical turning point in that war. But if I evoke a specific memory from third grade—say, the time your teacher came outside at recess and played a game of kickball with the whole class, and wound up colliding with Chris Gleason on first base, and everyone collapsed in hilarity, it all comes back: the specific texture of the red rubber ball you used for kickball, the bright red of Chris’s face when he realized that five-foot-tall, 98-pound Mrs. Dice was about to collide with him, the way Mrs. Dice laughed so hard her little gray bun came undone, the dust of the kickball field, and the crisp, autumn day.

At least it does for me, because (as you may have guessed) this is a real memory from my real life.

In this way, episodic memory carries more information, in a more lasting way, than semantic memory.

Because scenes put us as readers there in the world of the story, they feel like magic. But skillful storytellers know how to use that magic in precisely the way that will best serve their story—to establish what’s most important in it, in a way that reader won’t forget.

Note from Jane: Enjoy this post? Join me and Susan for her online class on May 11, Your Novel’s 4 Key Scenes.

May 3, 2023

Writer’s Block? Maybe You’re Writing in the Wrong Format

Today’s post is by author and writing coach April Dávila (@aprildavila).

Earlier this year, I took a week-long writing retreat at the Dorland Mountain Arts Colony in Temecula, California. I had an idea for a new project and had written about 10,000 words, but I wanted some focused time to dive in and figure it out.

The week started off well. I wrote 13,000 words in the first two days, exploring characters and drafting scenes that had been percolating in my head, but on the third day everything slowed down. I simply couldn’t think of what else to write.

In the past I would have called it writer’s block, but I don’t believe in writer’s block anymore. In fact, in my coaching program, I devote an entire hour-long lesson to dismantling writer’s block because I believe fervently that it’s not a thing. It’s just a catch-all phrase we use to describe other things that keep us from writing.

But sitting there, staring out the window of my cabin in Temecula at the unusually verdant valley below, I began to worry I had been wrong. What if writer’s block really IS a thing? Not only was it a concern for my immediate circumstances, but it seemed to me that if writer’s block really was a thing, I would have to write a letter of apology to every writer I’d ever worked with. Had I really been wrong all along? In my mind, a spiral of darkness opened like a gaping mouth.

But wait, I thought, I had never, in all my years of coaching, failed to help a writer get unblocked. I just had to coach myself a bit. I mentally stitched up that pit of despair and instead imagined the conversation that might take place between April Dávila the frustrated writer and April Dávila the writing coach.

Frustrated April: The words just aren’t coming.

Writing coach April: Is the material too fresh? Maybe you need to do some more research.

Frustrated April: No, I know what I want the story to be. I’ve been outlining for months.

Writing coach April: Are you maybe feeling overwhelmed, burned out?

Frustrated April: Are you kidding? (gestures at gorgeous view from my cabin that I have all to myself for a whole week) The words should be flowing like vodka at a Sean Combs party. (bangs head against the desk)

Writing coach April: Maybe you’re not writing what you think you’re writing.

Frustrated April: (lifts head) Wait… what?

As soon as I had the thought, I knew it was spot on.

One of the things I explore with blocked writers is the question of whether, perhaps, they’re writing in the wrong format. For instance, they think they’re writing a short story, but it’s really meant to be a poem. Or they’re writing an essay that really should be a memoir.

Turns out, I’m writing a novella. I googled the word count range for novellas (it’s 10,000–40,000) and was flooded with a mix of relief and excitement. Am I really writing a novella? I think I am. I knew this project would be short (it’s political satire), but realizing it’s a novella suddenly made the whole structure fall into place.

I spent Thursday and Friday reorganizing what I had into a new structure, writing some scenes that suddenly needed to be written (no more “writer’s block” here), and then BAM, I had a first draft. Oh, the satisfaction!

What’s more, I felt a renewed sense of confidence in my assertion that “writer’s block” is not a thing.

If you’re feeling blocked and think you might be writing in the wrong format, take this handy little quiz and tally up your score as you go.

Why did you choose the format you chose for your story? That is, if you think you’re writing a novel, ask yourself: why a novel?

It’s what I’ve always written: 1 pointThe story I’m telling is well suited to this format: 0Have you considered other formats (poetry, essay, memoir, novella—even if you’ve never written them before)?

It never occurred to me: 1 pointYes, I’m genre-fluid: 0Are you currently reading a lot in the format you’re trying to write (for example: you are trying to write a novel and are reading a lot of novels)?

No. I’ve been really interested in (fill in style of story you don’t usually read): 1 pointYes: 0If you scored any points at all, you might be writing in the wrong format. Take some time to explore other styles of storytelling. Give yourself permission to grow and change as a writer. Consider the possibilities that could await you as you embrace a new style of writing.

This is one of those rare times in life when realizing you’ve been wrong is actually really exciting.

May 2, 2023

Boost Your Book Launch by Perfecting Distribution and Metadata

Photo by ANTONI SHKRABA production

Photo by ANTONI SHKRABA productionToday’s post is by David Wogahn, the author of Countdown to Book Launch and the president of AuthorImprints, a self-publishing services company. This article is based on his presentation at IBPA’s Publishing University, Launch Plans—Build Out Your Blueprint for Success.

The major self-publishing platforms have made the publishing process easy—perhaps too easy. We’ve been conditioned by our use of consumer technology to expect instant results. Errors are not difficult to fix. A change of heart or opinion? Re-upload the file or edit your book’s listing!

But in practice, some things in publishing can’t be changed, and other changes don’t happen anywhere near as fast as you might think. The truth about publishing is that you basically get one shot with many essential aspects of the process. Do-overs can be expensive if not impossible, or they may not be successful.

During the past ten years, AuthorImprints has helped more than 200 self-publishing authors publish their books. We’ve experienced virtually every conceivable pre-release production challenge, discovered pitfalls to avoid, and found several opportunities you can use to streamline the publishing process. Here are the most important lessons self-publishing authors can integrate into their first or next book-release plan.

Determine your distribution strategy firstThe first question I ask a self-publishing author is if they have special print requirements as these may preclude the use of print on demand (POD). Those requirements can include the need or preference for special paper, color printing, or non-standard dimensions.

Beyond the cost of printing, the big hurdle for books that are not POD is selling the book on Amazon and listing it in the Ingram catalog. For this you’ll need to find a distributor or fulfillment company that can do this for you.

On the other hand, the two big POD providers—Amazon KDP and IngramSpark—offer printing with distribution as a single offering. Compared to printing books in bulk and having to find a distributor, the process is simple to set up, assuming your book meets POD requirements.

This is what makes POD so popular with self-publishers. It’s a terrific solution, but it also carries those expectations of instant results and the assumption that updates are easy. They can be, but make sure you avoid these three gotchas when using IngramSpark. They can bring chaos to an otherwise well-planned book launch:

1. Do not enable distribution until the files are final. IngramSpark clearly states that they may begin printing books “as soon as the title is enabled for distribution.” If you’ve uploaded a draft or advance reader copy, and distribution is enabled, that’s the version your buyer may receive. It has happened to novices and experienced authors alike.

2. While your book is available for pre-order, don’t make changes to the files close to the release date. This relates to the preceding lesson. If your book has been enabled for distribution, IngramSpark states it will be removed from distribution while the changes are processing. I’ve found that books sometimes remain for sale. You never know.

For example, a client’s hardcover was available for pre-order two weeks before the release date when he asked us to update the dust jacket. It was indeed removed from distribution, and as of this writing, three weeks after release date, it still isn’t available for purchase from Amazon.com. Other stores have it, including Amazon.co.uk, but not Amazon.com.

3. Do allow for listing delays. We’ve found that books distributed by IngramSpark will appear on Barnes & Noble relatively quickly, in about a week or so. But we’ve seen it take weeks for a book to appear on Amazon in full—cover, price, and order button. It can also take weeks for the formats to be connected or joined on a single page. Other times, these processes may take only days.

Does that mean Amazon KDP is a better choice? No, they aren’t even an option if you want to offer pre-order. KDP also does not allow you to control wholesale settings, which you need to control so bookstores can order your book.

I suggest you upload final files at least six weeks before release date and don’t make changes to the files.

Get the price right from the startLeaving margins aside, your paperback’s retail price can generally be competitive with traditionally published trade paperbacks. It’s almost impossible, however, to be competitive with hardcover pricing. Printing in bulk helps, but larger publishers also have distribution efficiencies that enable them to price hardcovers more attractively than self-publishers can.

The biggest difference between self- and traditionally published book pricing can be seen with ebooks. One reason for traditional publishers’ high ebook prices is to protect the pricing of their print editions, which in turn benefits bookstores. But traditional publishers also enjoy distribution advantages unavailable to self-publishers via KDP or from a self-service ebook aggregator. Traditionally published books often aren’t subject to the download fees charged by KDP, and the royalties are different. These terms can be negotiated by traditional publishers.

For more on pricing self-published books, read Kim Catanzarite’s post about the wisdom of giveaways and low pricing here on Jane’s blog. Her experience is my own, and I give most of our new author-clients the same advice: price aggressively low from the outset. If you start high and later reduce the price, you may never recapture momentum. You want to maximize reading, not margins. Having lots of readers translates to getting customer reviews. And books with lots of reviews have pricing leverage.

Also: get your metadata right from the start for better discoverabilityNever submit the metadata for your print book until you are 100 percent certain it is final. Certain metadata elements become locked when a print book is set for release. This includes not only the title, subtitle, imprint, and ISBN, but also the book’s dimensions and paper type, and none of it can be changed after the book is released. If changes are needed, you must republish the book.

Here are the three marketing-related tasks you should complete during the book production process to help improve discoverability.

1. List your completely ready, no further changes needed on anything print book for pre-order on IngramSpark at least four weeks (preferably six) before the release date. As noted above, it can take days or weeks for the book to appear on Amazon, ready for purchase. This listing is important for three other reasons:

Assuming you bought ISBNs recently, they probably begin with 979, which means Amazon assigns their internal identifier, called an ASIN. This 10-digit alphanumeric identifier is embedded in the Amazon link to your book. You need the link for marketing.When a book is available for pre-order, you can add it to your Amazon author page, or set up an author page (via Amazon Author Central) if you are a new author. While you’re at it, set up a free author profile on BookBub.You can add or update editorial reviews as they come in. There are fields for this in IngramSpark and Amazon Author Central.2. Assign the ISBN by completing all the required information and clicking the Submit button. A few years ago we did this for one of our client’s books, and the publisher received orders from a library distributor and an indie retailer, Books & Books (Florida). The book was not available from any retailer for pre-order, and Bowker had the only public record. (That’s the thing about the book business; you never know how someone will discover your book.)

3. Order library cataloging from a service that also submits it to the WorldCat database (“the world’s largest library catalog.”) Will it help you sell more books? Hard to say. What I do know is that bookselling is all about discovery, and the more databases (and stores!) you can get your book into, the easier it is for readers, librarians, wholesalers, and retailers to find it.

In summary, distribution planning, pricing, and metadata-release timing can have as much to do with your book’s success as writing and cover design. Done poorly, readers may never have a chance to discover your book.

Typos can be fixed, covers replaced, blurbs adjusted, and keywords updated. But to quote Euripides, “A bad beginning makes a bad ending.”

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1885 followers