Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 45

August 4, 2023

Wattpad Authors Who’ve Gone From Page to Screen

This summer, Wattpad is running their 14th annual Watty Awards, the company’s annual global writing competition. It’s open to writers in nine languages across 11 genres. In addition to cash prizes, one winner will receive a book deal from the Wattpad WEBTOON Book Group, and nine winners will receive adaptation opportunities with Wattpad WEBTOON Studios. (Judging closes on August 8, 2023.)

I asked three past winners about their experience of seeing their work adapted for the major streaming services. They are:

Ariana Godoy, best known for Through My Window, which has more than 350 million reads on Wattpad and has been adapted into a hit film from Netflix and Wattpad WEBTOON Studios. The film is one of the top five most viewed non-English films of all time on the platform. Ariana is a Latina immigrant from Venezuela who was an elementary school teacher before leaving her job to write full time. From Malaysia, Claudia Tan is a new adult romance writer, graduating from Lancaster University with a BA in English Literature and History. Her Perfect series on Wattpad has accumulated over 163 million reads, and nabbed the People’s Choice Award in the Wattys Awards in 2015 and 2016. The series has also been published in French by Hachette Romans and Perfect Addiction (86 million reads on Wattpad) was adapted into a feature film from Wattpad WEBTOON Studios and Constantin Film. The movie was released internationally on Amazon Prime in March 2023 and debuted in the top 10 most-watched movies all over the world, according to Flixpatrol.Beth Reekles is the author of The Kissing Booth, which she first published on Wattpad in 2010, when she was 15 years old. The story won a Watty Award in 2011 and went on to accumulate almost 20 million reads before being published. Reekles signed a three-book deal with Penguin Random House and was named one of Time Magazine’s Most Influential Teenagers in 2013. Produced by Netflix and Komixx Entertainment, The Kissing Booth went on to become one of the most watched films in the world when it was released on Netflix, according to the streamer.Jane: What was your initial motivation for writing and publishing on Wattpad?

Ariana Godoy (AG): I’ve loved reading since I was a kid. Growing up, I didn’t have money to buy books so I would read the few stories that I had over and over. When I found Wattpad and realized it was free, I was thrilled because it had thousands of stories for me to enjoy, and I was even more excited when I realized anyone could post their work. Seeing other authors achieve success motivated me to post my first story in 2009.

Claudia Tan (CT): I mostly wanted to use it as a training ground to hone my writing skills. I was also keen to find a home for the types of stories I wanted to write, but before Wattpad, had no audience.

Beth Reekles (BR): I thought—why not! I was already on the platform as a reader and enjoyed writing, so figured I had nothing to lose. The ability to be anonymous also really appealed to me.

How much were you involved in the adaptation of your work to the screen?

AG: I was quite involved. It was a bittersweet process because as an author, that first time you see the script, it kind of shocks you and it takes time for you to adapt and understand that movies are just a different format, a different way to tell your story. Working with the team and the amazing cast has been incredible, they really pour their heart out to represent the story and I think they did a great job.

CT: I was asked to review the early versions of the script, but changes were up to the studio and the director to implement.

BR: I got to meet with the scriptwriter/director, Vince Marcello, early in the process and give feedback on the script. It was clear that he really understood the characters and the story and I knew I could trust him with The Kissing Booth.

Was there anything that surprised you about the effects of having your work available on a major streaming service?

AG: Oh, definitely. I didn’t expect the movie to get to the top 10 in so many countries and it was amazing to see how many messages I received from fans. I was shocked that my little Spanish story was discovered and enjoyed by people from all over the world!

CT: To be able to capture a wider audience for my writing has been really rewarding. As an author from Malaysia this was a major achievement, and an opportunity that not many people from here have.

BR: Only that I wasn’t able to get a DVD/physical copy (I’m a big fan of keeping DVDs of my favorite movies)! That said, seeing my work on Netflix felt like a natural progression as I started my writing career online.

Has the experience changed how you develop and/or write your stories, especially at Wattpad?

AG: I don’t think it has changed the way I write. I’ve been on Wattpad for 13 years now, so I’m very seasoned on the site and I have built a strong structure around creating new stories.

CT: I don’t think so. I didn’t write these stories to get them made into movies; I just wanted to have fun with it, and Wattpad allowed me to express myself in a way that you might not see on another platform. I think that is what makes my work special, and that’s probably what attracted the studio in the first place. To change it now would feel inauthentic to my audience.

BR: Not for me—I always write the kind of book I want to read, and that’s my priority when I’m working on a new story. I’m definitely not afraid to try something new if it feels right for the book, like my multi-POV adult novel, Lockdown on London Lane, which also started on Wattpad. I’d love to see another of my works adapted to screen, though!

August 3, 2023

Pay Yourself to Write

Photo by Andre Taissin on Unsplash

Photo by Andre Taissin on UnsplashToday’s post is by author, editor and coach Jessica Conoley.

If you want to be the person who supports yourself with your writing career, then it’s time to take a good look at money and how you are going to harness the inherent power of your creative work via your financial habits. It doesn’t matter if you haven’t made a cent for your creative work thus far. How you start looking at money now is going to determine how soon creative paychecks start rolling in.

Writers tell me, “I don’t want anything to do with the money part. I just want to create and leave money to my agent/manager/team/anyone else but me.”

This is a common sentiment for an Uninitiated Writer. I said the same thing back when I took over as managing editor of a magazine. My one caveat to accepting the role was, “I’ll do it, but I want nothing to do with the money.”

A combination of issues make us hesitant to deal with the financial part of our creative career.

The deeply internalized acceptance of the starving artist myth.The belief that accepting money for our art compromises our status as real artists and makes us sell-outs.The conditioning that writers are bad with money and therefore must rely on other people to manage it.The overwhelm at the thought of learning money management skills.The personal money baggage that has to do with how you grew up and saw money being used around you.Delegating your financial responsibilities puts your ability to support yourself through your creative work in other peoples’ hands. This delegation allows others the opportunity to profit from and exploit your talents and body of creative work.

By saying “I don’t want to deal with my money,” you are saying, “I don’t want to deal with the power and freedom that comes with the money I can earn from my creativity.”

When you turn a blind eye to money, you are turning a blind eye to your power. And, when you avoid money from the start of your career, you impede your ability to call the shots in every other aspect of your life.

Let me repeat for those of you who have been force-fed the myth of the starving artist. YOU CAN EARN MONEY LIVING A CREATIVE LIFE.

Financially successful writers do not sell one great masterpiece and live off that windfall for the rest of their lives. Creativity is not a lottery ticket, but rather a building block of a long-term sustainable business. You build financial independence one baby step at a time—the exact same way you build your writing portfolio.

Today is the day you start building financial habits to acknowledge and validate the inherent monetary worth of your creations. To become the creative who has money in the bank for their creative work, here’s how you start:

Get out a pen and paper, or your phone with the notes/voice-memo app. As you read the next four steps, note every immediate reaction you have to the following instructions. Note both physical and intellectual reactions. i.e., clenched jaw and “This author is out of her mind,” etc. Set up a SAVINGS account specifically for your creative income. Make sure there are NO fees or minimum balance requirements.Log in to your online banking and go to settings.Rename the account. I recommend names that remind you that your creative career is fueling this balance. Titles like: $ MY ART MADE or MY BOOKS PAY BILLS or CREATIVE CASH.Go to the visibility setting and turn it off. Make the account invisible, so you don’t see it on the main screen when you log in to the bank.Decide how much and how often you’re going to pay yourself. Start with what you can afford:1¢ for each finished blog post50¢ for each new recipe$1 for a recorded song$2 per hour of practice/studio/writing time, paid every Friday.Pay yourself according to the wage and timeline you set for yourself.What physical reactions did you have? Stomach knot? Tension in the neck? Balled fists? Note those personal physical indicators you are expanding beyond your comfort zone. Your body wants to keep you safe and you’re moving into unknown territory, which makes your body anxious. Take a deep breath and roll out your shoulders. Tell your body out loud, “We’re safe. This is a healthy, safe, new space we’re entering. I’ve got you. Thank you for keeping us safe.”

Physical symptoms are the first indicator that you are experiencing mental dissonance as you level up your identity from Uninitiated to Initiated Creative. By addressing your physical safety first, your mind is more receptive to exploring new ideas and identities.

What intellectual reactions did you have? “You want me to pay myself? That’s cheating. Plus, I’m broke. I haven’t even shared my stuff publicly. Bank accounts are for REAL writers. Besides what good will 30¢ for thirty whole blog posts do me?! I can’t live on that.” What other opinions do you have about opening a savings account and paying yourself every time you create?

Add those to the list and buckle up, because those excuses are places for you to dig into the money mindset issues that keep you from accepting payment for your work. Variations will pop up continuously throughout your creative career.

Identify, acknowledge, dismantle, and act upon your money mindset issues now, so you have the confidence to ask for your full worth when the opportunity presents itself.

By completing steps 2–5 you quiet those dream assassins. Here’s how acting starts an energetic tsunami in the transition from unpaid to paid creative.

Setting up that savings account establishes the intention that you will make and retain money from your creative work.Turning off visibility jump-starts relying solely on your internalized self-trust and self-worth. You are establishing the identity of a creative who has money in the bank as a result of their creative efforts. (Hiding it also lessens the likelihood you will spend the money. Banks want to give you money when you have money. You are setting up a financial power reserve to fuel and sustain you.)You are telling yourself that your creative time, effort, and products have inherent worth. I deserve to be paid. You are practicing: setting prices, expecting compensation, and being a good steward of your money. (For those of you still balking at the idea, remember founders of multi-billion-dollar companies pay themselves a salary.)Every time you pay yourself, you reinforce the habits of billing for completed projects and accepting payment for your work. You are building the identity of “I am a PAID creative.”Now open a new browser, go to your bank’s website, and fill out the form for your new savings account. Pay yourself. You’ve earned it.

August 2, 2023

Building Your Brand on TikTok Isn’t Curation, It’s Authenticity

“To Thine Own Self Be True” by futureshape is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

“To Thine Own Self Be True” by futureshape is licensed under CC BY 2.0.Today’s post is by author Kerry Chaput.

Social media algorithms often feel like a rigged game, with authors standing on the sidelines yelling “Pick me!” Fortunately, my relationship with social media changed the moment I decided to create my own space and let readers come to me.

When I joined TikTok in December 2021, I was prepared to hate every second. Young, witty creators and BookTok accounts were killing it at book marketing, and I was a middle-aged mom struggling with anxiety, whose preferred topic of conversation is Eleanor Roosevelt’s contributions to history.

But I quickly discovered that I ended up right where I belonged. And you belong there too. TikTok, unlike Instagram’s aesthetic values or Twitter’s expectations for witty virality or negativity, is exactly for someone like me.

People crave honesty. So much of our lives is spent pretending to have it all together, when inside we’re crying out for someone to get us. When I shed the idea of “curating” content and started to discuss the things I cared about, my views went up and so did my book sales.

My first viral video was one minute, forty seconds, and put my history nerd status on full display. I discussed the background of my historical fiction series Defying the Crown, and why I cared about the women it highlighted. What I translated to viewers (and readers) was a love for women’s history from a lens of power and success, rather than stories of women’s misery and pain.

It was then I realized the power TikTok holds.

I could shout my beliefs and interests from the rooftops, and find my people, my readers. I could bring attention to the kind of things I write about and value in my young adult novels, and books like them. Fat positivity, inclusivity, sex-positive relationships for young women, self-acceptance, and mental health awareness.

I was inspired to begin a series: Badass Women in History. These are stories of powerful young women who pushed past every barrier to follow their dreams. The videos exist to remind people that history is full of diverse, interesting women who have yet to gain recognition for their incredible lives—and not all their stories are steeped in pain. My second viral video discussed Mileva Einstein’s contributions to science, and my top video celebrates the eccentric Alice Roosevelt, still climbing toward one million views.

There are principles I live by when it comes to TikTok. The most important thing is to always be real. Here is how I honor that realness, and you can too:

1. Focus less on your genre space and more on what stories you identify with.Hashtags are great to identify genre and age category, so let your video speak to your ideals and the things you care about. Your content should connect viewers with universal experiences. Maybe it’s the struggle of parenthood, or the humor you find in the mundane. Perhaps you have a love for calligraphy or ghost hunting, soap making or watermelon carving. Can you show your hobby while discussing writing? Can you connect your unique interests to the reason you write stories? Discover the meaning of your words outside of genre and tropes. There is something personal attached to your stories. Find it and share it with your viewers.

2. Examine what themes find their way into your writing. What aspects of the human condition baffle and intrigue you?We tend to lean into the big questions in our lives through books, and I believe that happens for both readers and writers. Look closely, and you’ll probably find something you’ve struggled to understand popping up in your work. It’s okay to ask questions on TikTok, to build community through shared intrigue or discovering new knowledge.

3. Employ the power of a series.Ask yourself: what can you talk about endlessly, or better yet, what are your obsessions? For me, I honor women in a way history books have failed to do—success, power, bravery. I care immensely about the women I research. My series gives me a chance to celebrate topics I love. You’ll find that if you care about it, other people will too.

4. People want authenticity above all else and TikTok allows us to showcase the messy side of life.A lifelong struggle with generalized anxiety, social anxiety, and panic disorder has left me committed to breaking stereotypes around this disease. I make a point to highlight mental health in my videos. From author check-ins to vulnerable posts about panic attacks, I stay open about mental health—a topic that finds its way into my stories in one way or another.

Not everyone needs to be this vulnerable, but are there struggles or quirks that are inherent to you? In other words, our power often lies in the parts we hide from the world. Find a comfort level in the cringe side of life. There’s a reason social media has created so much stress for people. Often, we see perfectly clean houses, success stories, celebrations, and expensive vacations. Our author journey isn’t all agent representation announcements and book deals. Sometimes, it’s crying in your car in the Target parking lot.

5. Discover why you care about your stories.I want young women to know their voice matters. This one outlook carries me through all my stories and every social media video. Find your mantra. Define your core belief that thumps in the background like a heartbeat, and infuse that into your TikTok. Let viewers know what you stand for. It’s a great introduction to the kind of books your readers can expect.

Passion and authenticity will take you farther than any perfectly scripted monologue. On TikTok, quirkiness and honesty are celebrated. I find that quite refreshing. This is an app that allows you to be perfectly, uniquely you. Here, conformity is out, and individuality is in. Contrary to how it might appear, TikTok success isn’t dependent on age, genre, or physical appearance. You don’t need to be young and beautiful and brilliant. People want to be inspired, and nothing does that more effectively than accepting yourself just as you are, without an ounce of apology.

July 28, 2023

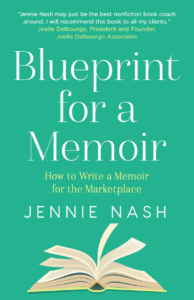

Decide Where You’re Standing in Time as You Write Your Memoir

Photo by Donald Wu on Unsplash

Photo by Donald Wu on UnsplashToday’s post is excerpted from Blueprint for a Memoir by Jennie Nash, founder of Author Accelerator.

Two temporal elements—the time frame of the story and where you are standing in time while you tell your tale—are central to the idea of structure in memoir.

But they are tricky to determine because you are still living the life you are writing about in your memoir, and you existed at all the points in time throughout the story you are telling. It’s easy to think that you are just you and the story is just the story, and to believe that you don’t have to make any decisions around time the way a novelist does. But if you neglect to make conscious choices about time, you risk getting tangled up and writing a convoluted story.

The first decision: choose a time frame for your storyWhat time period will your story cover? Don’t think about flashbacks to your younger self or memories of times gone by; all stories have that kind of backstory and it doesn’t count when answering this question.

Also don’t think about whether you are going to write your story chronologically or present the story in some other way (such as backward or in a braid); these are questions about form that get sorted out later.

For now, just think about what is known as “story present”: the primary period of time that the reader will experience as they are reading the story.

Here are some examples of story present from well-known memoirs:

The several weeks I spent hiking the Pacific Crest Trail (Wild by Cheryl Strayed)The year I planted my first garden (Second Nature by Michael Pollan)The three years I was in an abusive relationship (In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado)The three years consumed by the trial of my rapist (Know My Name by Chanel Miller)The four years when I was a dominatrix (Whip Smart by Melissa Febos)My childhood in Ireland (Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt)The 18 years following the accidental death of my high school classmate (Half a Life by Darin Strauss)The 30-something years of my marriage (Hourglass by Dani Shapiro)My whole life (I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell)If you find yourself considering a time period that covers your whole life or a big chunk of time like the last two examples in my list, make sure that you actually need to include the entire period of time to effectively tell your story.

Dani Shapiro’s Hourglass doesn’t cover her whole life, but it covers many decades. That’s because her topic is itself time—the way it moves and flows in a long marriage, the impact it has on the relationship. Even her title cues us into this truth: She is making a point about the passage of time. The time frame she uses fits her point.

Maggie O’Farrell’s memoir, I Am, I Am, I Am: 17 Brushes with Death, starts in her childhood and covers the entirety of her life up until the moment she is writing the book. It is a beautiful and effective story. But note that the intention of this book is not to tell her life story; it’s to discuss the specific ways that she is mortal and the reality that we are all mortal, and to remind us that every moment is a gift. She imposes a concept onto the material—a form or structure to unify or organize the material so that it’s not just a bunch of things that happened but a very specific and highly curated progression of things that happened. The story presents her whole life, but she only chooses to tell 17 stories. The time frame she uses fits her point as well.

The second decision: where you are standing in time as you tell your taleWhile you are thinking about the time frame of your story, you also must decide where you are standing in time when you tell your story. There are two logical choices:

1. Narrating the story as you look back on itThe first option is that the story has already happened, and you are looking back on it with the knowledge and wisdom gained from having lived through those events. You are standing in time at a fixed moment that is not “today” (because today is always changing). It’s a specific day when the story has happened in the past and the future life you are living has not yet happened. This choice has to do with what we call authorial distance, or how far from the story the narrator is standing. In fiction, a first-person point of view often feels closer to the story than a third-person point of view. In memoir, if you are telling the story from a specific day that is just after the events that unfolded, you will be closer to the story than if you were telling the story from a specific day three decades later.

I wrote my breast cancer memoir just months after my treatment had ended and the friend who inspired me to get an (unusually early) mammogram had died. Her recent death was the reason for the story and part of the framing of it. She died young and I did not; the point I was making was about getting an early glimpse at the random and miraculous nature of life—a lesson that most people don’t really metabolize until they are much older. I wanted to preserve the close distance to the events of the story. If I told that story now, I would be telling it with the wisdom of having lived well into middle age—a very different distance from the story and a very different perspective.

I once worked with a client who had been a college admissions officer at an elite private high school. The pressure of the work, the outrageous expectations of the kids and parents, and the whole weight of the dog-eat-dog competitive culture contributed to him having a nervous breakdown. He wrote a memoir in which he answered college application questions from the perspective of a wounded and reflective adult. It was brilliant, and part of its brilliance was the wink and nod of doing something in his forties that so many people do at age seventeen.

We are talking here about authorial distance related to time, but there is also the concept of authorial distance related to self-awareness. I know that sounds a little like an Escher staircase circling back on itself—and it kind of is. The narrator of a memoir (the “you” who is standing at a certain moment in time) has some level of self-awareness about the events and what they mean. One of the reasons that coming-of-age stories are so beloved is that, by definition, the narrator is awakening to themselves and the world for the first time. There is very little distance (temporal or emotional) between who they were and who they became and there is a purity and poignancy to that transformation. It’s as if they are awakening to the very concept of self-awareness.

It is entirely possible for an adult to write a memoir and not bring much self-awareness to what they are writing about; it’s unfortunately quite common. A narrator who is simply reciting what happened—“this happened to me and then this happened and then this other thing happened”— is not exhibiting self-awareness about their life. They are not stepping back emotionally from it, so they don’t have any perspective to offer no matter how far away they are from it in time. They are just telling us what happened. These kinds of stories tend to feel flat and self-absorbed. They make no room for the reader. They don’t offer any sort of reflection or meaning-making, don’t offer any emotional resonance, and don’t ultimately give us the transformation experience we are looking for when we turn to memoir.

Laurel Braitman, author of What Looks Like Bravery, explains it like this: “I tell this to my students now: You can only write at the speed of your own self-awareness. You do not want the reader to have a realization or insight about your life that you haven’t had already or they will lose respect for you.”

If you are telling your story as you are looking back on it, make a clear decision about exactly where you are standing in time and make sure you have enough self-awareness to guide the reader with authority through the events you are recounting.

2. Narrating the story as it unfoldsThe second logical option in terms of where the narrator stands in time is to tell the story as though you are experiencing it for the first time. There is no temporal distance from the events you are writing about. You narrate the story as the story unfolds, which means that you narrate it without the knowledge of how it all turned out. In this kind of story, the self-awareness that is necessary for an effective memoir is unfolding as the story unfolds as well.

I wrote a memoir about getting married and the structure of it was a “countdown” to the wedding. In this format, the concept is that events were unfolding as I was living them. This wasn’t technically true—I wrote the book after the wedding had taken place—but I had taken extensive notes and was able to preserve the concept of not knowing how people would behave or how I would feel. (This book embarrasses me now—the whole idea of it. I was 25 when I wrote it, so what can I say? I am grateful for its role in my career and here it is being useful as an example.)

In Joan Didion’s memoir, The Year of Magical Thinking, she wrote about the year after her husband dropped dead at the dinner table, and of the difficulty that the human mind has grasping that kind of catastrophic change. In the first pages of the book, she writes, “It is now, as I begin to write this, the afternoon of October 4, 2004. Nine months and five days ago, at approximately nine o’clock….” What she is doing here is signaling to us that there is not a whole lot of authorial distance or self-awareness to what she is sharing. She is figuring it all out—this tendency to think magical thoughts about the dead not really being dead—as she writes. But the key thing is that she knows that she is figuring it out, and she invites us into the process. She has self-awareness about her own lack of self-awareness. She is not just telling us about the dinner and the table and the call to 911.

In Bomb Shelter, Mary Laura Philpott places her narrator self at a point in time when the story is still unfolding; she has perspective and self-awareness, but those elements are still clearly in flux. The New York Times reviewer Judith Warner called this out in her rave review of the book. Warner said, “I want to say something negative about this book. To be this positive is, I fear, to sound like a nitwit. So, to nitpick: There’s some unevenness to the quality of the sentences in the final chapter. But there’s no fun in pointing that out; Philpott already knows. ‘I’m telling this story now in present tense,’ she writes. ‘I’m still in it, not yet able to shape it from the future’s perspective.’” Like Didion, Philpott was well aware of the choice she made around narration and time, and those choices perfectly serve her story.

Can a narrator stand in two different places in time?Writers often get into trouble when they try to combine two narrative stances: They write one scene about their childhood with the innocent voice of a young person and then write another scene with the wisdom and jaded voice of their current self. The trouble comes when they don’t do this on purpose; they do it because they haven’t thought about these questions of time. The result is like head-hopping in fiction: When the writer bounces from character to character, the reader has to struggle to follow the emotional thread of the story, and odds are good that they won’t stick around to struggle for long.

Maintaining narrative distance from your childhood self doesn’t mean that you have to give everything away. Your adult self who is the narrator doesn’t have to be a know-it-all. In I’m Glad My Mom Died, Jennette McCurdy writes about brutal experiences she had as a child actor. The adult McCurdy recalls how she experienced those events and what she felt about them, but she doesn’t give us the conclusion of those events—the realization that her mother was abusive—until later in the book. She tells us what happened when she was a child and why she hated it and how she reacted (she chronicles her descent into disordered eating), but she doesn’t figure out exactly what it all meant until she grows up a bit. So as a reader, we experience this arc of change alongside her. We experience the transformation. What she did not do is give us a child-like experience of the childhood scenes or a flat recitation of the facts.

There are, of course, always exceptions. My book coach Barbara Boyd told me that one of her proudest moments as a coach involved a memoir in which the author, Lorenzo Gomez III, wrote about his experience in middle school using his adolescent point of view and ended each chapter with a letter from his adult self to the adolescent self, using his adult point of view. That book, Tafolla Toro: Three Years of Fear, was turned into a play that high school drama clubs perform. But Gomez did not land on that structure by accident; he made a conscious choice about how to shape his story—and so must you.

As you answer these two questions about time, look back at your why and your point, the super simple version of your story, and your ideal reader. All of those answers will inform your choices about time.

Chronological time versus fractured timeEverything I have written about time, above, has assumed that your memoir is going to be told chronologically. The vast majority of memoirs are stories told in this way. For example:

Know My Name by Chanel MillerWild by Cheryl StrayedMaybe You Should Talk to Someone by Lori GottliebWhen Breath Becomes Air by Paul KalanithiHunger by Roxane GayBetween the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi CoatesLost and Found by Kathryn ShulzBossypants by Tina FeyI’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdyChronological order means that the tale is told from beginning to end the way that it happened in your life. Again, flashbacks and memories don’t count here; including them doesn’t mean that a story isn’t being told chronologically. In a straightforward chronological narrative, there will almost certainly be flashbacks—moments in a narrative when the writer recalls something about their past in order to make sense of what is happening in story present, so they go back in time in order to move forward with more insight—but the story the author is telling still moves through a distinct period of time (story present) in chronological order.

The other thing that doesn’t negate the straightforward chronological structure is the choice to use a flashback as a framing device. In Wild, for example, there is a prologue in which the author has just lost a hiking boot over the side of a canyon, and she throws the other one after it. It’s a scene that appears again about three quarters of the way through the book. Starting her story with that scene sets the stage for what is to come, adds a whole lot of tension, and is a fantastic place to begin. The rest of the story follows Strayed’s preparation for the hike and the hike itself and proceeds in a straightforward chronological way (with a whole lot of flashbacks as Strayed is figuring out her relationship with her mother and to loss and to herself). Despite that prologue, the structure of Wild is still a straightforward chronological narrative.

Choosing a straightforward chronological narrative is a good choice for most memoirs. It’s how we live our lives, after all, and how we tell most stories in real life. There is a naturalness and a comfort to this structure.

But what if you want to tell your story with a timeline that is fractured or deliberately presented out of order? A fractured narrative is different from a story that includes flashbacks because the author leaps around to different time periods and doesn’t “return” to a chronological story present. In a fractured chronology, story present itself is out of order. Story present still exists, because the reader is still experiencing the story within a particular frame, it just doesn’t proceed chronologically.

Sound confusing? It can be. A fractured narrative can be far more difficult to write than a straightforward chronological narrative but, for the right story, it can be a powerful choice to make, especially if you are using fractured time to reflect an experience that was itself somewhat chaotic as you lived it. It gives the reader a sense of being unsettled; although the best fractured narratives also give a sense of safety or authority—we know that the writer is in charge of the journey and taking us on a winding path that will end up where they want us to go. We trust them and we’re happy to follow them. A fractured narrative can also work very well if you are writing about an idea or a concept that permeates a life, like how often we come close to dying (I Am, I Am, I Am) or how a human being copes with the terrible and endless anxiety of loving other people (Bomb Shelter).

My niece Caroline has been teaching herself the art of quilt design. She recently began to design a quilt for a new baby coming into our family. She explained to me that there is a visual language for quilting. Before you get to decide what colors to use, the first consideration for a quilt is the grid: Will it be a traditional grid, a deconstructed (or fractured) grid, or will there be no grid at all (a choice that leads to a freeform style)? Once you decide on the grid, you can decide on scale: Will you zoom way in on your grid to highlight one element of it? Will you zoom way out to show the ebb and flow of the grid? Once those questions are answered, you can finally look at color, and how tone and contrast will function in your quilt.

As she was outlining this visual language, I kept thinking that this process was exactly like the choices surrounding time in memoir. Before you can look at the chapter outline or select the stories you will use to tell your tale, you have to select the underlining structure. If you make the decision to use a fractured chronology, you are choosing to upend the traditional narrative structure in order to tell the story in a way that is less predictable or rigid. Both can result in a pleasing design, but they will have very different underpinnings.

In a story told with a fractured chronology, the narrator is almost always standing in time at the end of the story, looking back at all the events and recalling them in a way that has its own internal logic. A story with a fractured chronology is not random; the writer has deliberately deconstructed the grid and imposed a different kind of order on the disorder.

Two of the books I’ve just mentioned use this tactic: In Bomb Shelter, Mary Laura Philpott is writing about the anxiety and fear she feels as a mother, a wife, a daughter, and a grown-up human, but she begins the story with a scene from her childhood involving stingrays. She then leaps around in time: to that one Christmas when that terrifying thing happened to one of her children, to that time when she was in grade school, to that time when her kids were in grade school, to the time in college when her dad casually mentioned the secret underground bunker that gives the book its name, to that time her child headed off to college himself.

The progression is not in any way random. Mary Laura is a friend, and I had the chance to read an early draft of her manuscript. She was deep in the process of figuring out the order of her stories. Should the story about the terrifying thing (her son’s first epileptic seizure) go first? It’s a dramatic story and a riveting piece of writing. The decision to put it first might have skewed her book to seem like a story about epilepsy, but that was never Mary Laura’s intention. She wanted to write about the larger idea of what it means to be a fragile human who loves other fragile humans, and how difficult it is. Her clarity about her point and purpose—and how each story was serving it—were part of what led her to arrange the stories the way she did. If you are considering writing a fractured chronology, or really any memoir, read this book. The New York Times reviewer whom I quoted earlier called it “genius,” “a masterwork,” and “a spot-on portrait of the complex melancholy of early middle age.”

I Am, I Am, I Am, Maggie O’Farrell’s tale about her 17 brushes with death, does not unfold chronologically. The opening chapter is entitled “Neck (1990).” Chapter 2 is “Lungs (1988).” Later in the book, there is “Cerebellum (1980).” The flow of material from one chapter to the next has its own internal motion separate from chronology. The stories bump up against each other in provocative ways, one sometimes leading to a memory from childhood, another leaping forward in time to a similar scare. There’s something very powerful about this deconstructed presentation: As a reader, we feel unsettled by each event, by the overarching point of the book, and by the way the events are ordered. Everything about it is nerve-racking, and yet that feeling is mitigated by the authority and clarity with which O’Farrell writes. The structure perfectly serves the story.

If you are going to choose to fracture the time in your memoir, make sure you know why you are doing it and consider how you will do it. What will guide you in your choice of how to present the material? You may not have a sense of this yet, which is fine. Sometimes it’s not entirely clear until you start looking at the whole story. But continuing to think about your use of time will eventually lead you to a decision.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, be sure to read Blueprint for a Memoir by Jennie Nash.

July 27, 2023

What Character Arc Isn’t

Photo by Steve Johnson on Unsplash

Photo by Steve Johnson on UnsplashToday’s post is by regular contributor Susan DeFreitas, an award-winning author, editor, and book coach. She offers a wide range of courses on the craft of fiction, as well as a free ebook, Cracking the Code: 10 Craft Techniques That Will Get Your Novel Published.

I write a lot about character arc, and I talk a lot about it with my clients.

Because if there’s a magic bullet for creating a novel that sucks the reader in, holds her attention, and ultimately makes her feel like it was worth the 6+ hours it took to read that book, character arc is it.

Many writers are clueless about the importance of a character arc for their protagonist, but I find that even those who do understand how important it is often still don’t know what it takes to actually make one work in practice.

Basically, there’s one key mistake they’re making: When it comes to the major events of the plot, they’re focusing on how their protagonist feels in the moment, based on different issues in their past, rather than on how that emotional reaction connects with their character arc.

To show you how this works in practice, let’s build a little story, starting with just the plot.

Example 1: Just the plotCallie is a programmer working on AI development. She’s been assigned to the team developing Ella, a large language model designed to provide therapy to those who can’t afford a human therapist, when she makes a discovery: the online therapy that Callie herself has been paying good money for, ostensibly for empathetic human support, is in fact being provided by a prototype of Ella.

Incensed, Callie calls out her online therapy provider for false advertising. Her customer complaint is handled by a chatbot (she knows this, because she helped to build it) and passed on to a “customer care associate” (also an AI, which she can tell by the way it responds to nonsensical statements) and then ultimately to the therapy company’s Director of Communications (an actual human), who tells her that he’s sorry, but he cannot confirm nor deny that her therapist is an AI, though he would be happy to provide her with a free month of therapy, because she sounds pretty worked up over all this.

Callie hacks the transcripts of her own therapy sessions and confirms that she was talking to an AI program, but she can’t go public with this information without sharing her own deepest, most private matters with regulatory authorities, and the public in general. Will Callie sit tight on all of this, or will she reveal these secrets—both hers and that of the online therapy company?

Example 2: Incomplete or unfocused character arcLet’s say the author looks back over this plot and decides they need to “get a character arc in there.” So they develop different elements of the protagonist’s backstory that might make the events of the plot more meaningful—and create a real change for the protagonist at the end.

So the author decides that Callie starts off in this story a very private person, and her big secret—the reason she needs therapy in the first place—is that her family is super toxic. Oh, and Callie is also crippled by perfectionism, due to her super-critical, no-good family.

So in this version of the story, when Callie discovers that her empathetic human therapist is, in fact, an AI program, she’s angry—not just because this company has engaged in false advertising, but also because this version of the program isn’t as good as the one she’s working on, and it shouldn’t be out in the world, it could say the wrong thing and hurt someone (that’s her perfectionism).

And when she’s ultimately passed on to the Director of Communications at that company, she’s intimidated at first, because that guy reminds her so much of her terrible father. She convinces herself that her therapist has to be human, because “Sheila” is so much like the mother she wished she had, growing up.

She hacks her transcripts, just to make sure, and finds out that Sheila is an AI. But she can’t expose the therapy company without exposing her own transcripts about her terrible, no good, manipulating family, and if she does, they’ll be hurt, and maybe disown her.

Callie decides maybe ultimately that’s for the best and does it anyway.

In this version, you could say there’s a character arc—a real change in the protagonist over the course of the story—but it feels like it’s all over the place. Is this a story about cutting ties with toxic family members? Is it about overcoming the desire to protect yourself in order to protect others? Is it about not being so hard on yourself that you require therapy, from either human or bot?

Given this progression, I have no idea. And neither would any reader.

Example 3: Complete character arcSo let’s see if we can narrow this down to something that actually makes sense.

Growing up, Callie was taught not to “spread her business around town,” which essentially meant never asking for help. That’s why, when she got doxxed by a veritable army of trolls as a woman in tech, and developed PTSD around it, she went for an online therapist: Not because she couldn’t afford an in-person therapist, but because going to a therapist at all felt so shameful to her that she wanted to do so as anonymously as possible.

So this AI developer discovers her therapist is an AI, and that her only recourse to exposing this company’s false advertising would be to expose herself—not only as needing therapy, but needing therapy because a bunch of teenage yahoos called her a bunch of misspelled curse words on Twitter. What would her family think? What would the world think, given the confident online persona she projects? Moreover: Would the trolls come for her again?

But maybe doing what she has to do to expose this company’s lies will also show the world just how real the psychological damage of doxxing can be. And maybe if she’s brave enough to ask for help from her online allies in fending off these trolls—showing the same bravery she did in seeking out therapy in the first place—she won’t be so alone this time.

Which means that the events of this story will now force this protagonist to face her greatest fear, making herself vulnerable and asking for help. And when she finally does, for the sake of the greater good, chances are good that readers will stand up and cheer—in part because it’s clear what this story is actually about: It’s about overcoming the fear of asking for help.

The upshotCharacter arc isn’t a thing you can create with a patchwork of different issues and emotional reactions. It’s a thing you create by focusing on one clear thread that runs the whole length of your novel, with each and every plot development pushing the character to confront one particular internal issue—and, ultimately, make a change for the better.

July 26, 2023

The Peril and Promise of Writing in First-Person POV

Photo by Gaetano Cessati on Unsplash

Photo by Gaetano Cessati on UnsplashToday’s post is by author Amy L. Bernstein.

Writing a novel is all about making choices—dozens on every page. Choosing the right point of view (POV) is arguably the most influential choice a writer makes. And choosing first-person POV, well, that may be the most complicated choice of all.

Why?

Because when you build an entire story around the “I” voice, you commit to installing the reader deep inside a single skull. In the hands of a skilled writer, there’s no more fun place to hang out.

“I am the vampire Lestat.” So begins Ann Rice’s rollicking novel, and we quickly realize we are to be guided by an enormously entertaining and self-absorbed narrator with a sly sense of humor.

“Call me Ishmael.” Like Lestat, Melville’s moody anti-hero (a self-described “simple sailor”) takes us on a vivid tour of city streets with a dose of social commentary on the side, followed, in this case, by a harrowing boat ride to track down a whale.

Lestat and Ishamel are each in their own way enormously charismatic and deeply observant of the world around them. A lot happens to them; they are also agents of their own destinies, at least in some respects. These are wonderful skulls to occupy.

No wonder some of today’s best writers gravitate toward first-person because, as Anne Tyler says, “It can reveal more of the character’s self-delusions” than, say, third person.

But to effectively execute this elevated brand of first-person narrative, writers must navigate a complex set of rules and avoid any number of pitfalls that will turn a novel into a flat, dull expanse of prose. I suggest that first-person POV is the most misunderstood and also the most difficult voice to master.

Let’s explore some ground rules (not an exhaustive list!) and common pitfalls before turning our attention to whether writing in first-person is the right choice for your story. (Spoiler alert: It’s often not the best choice.)

Rule #1: ConstraintThe moment you elect first-person POV, you relinquish the option to tap into an omniscient narrator who knows all, sees all, and can travel at will through time and space, or walk through walls, when called for. (This is ironclad unless you write a fantasy main character who possesses omniscient powers, but that’s the exception that proves the rule.) The narrator can only process information the way we do in the real world: through her senses. This rule straps the writer into an exquisite straitjacket.

Rule #2: ComplexityA first-person narrator can lie to himself and everyone around him, but an attentive reader will always know, or have a good guess, about what’s really going on. That’s because the first-person voice exists on two planes simultaneously. On one plane, the main character speaks his truth (however deluded) within the context of the story’s self-contained world. (Rule 1 requires this.) Meanwhile, the reader is analyzing the narrator’s motives and circumstances—and drawing conclusions about what’s really going on. The writer needs to be true to the narrator’s voice and situation while remaining aware of the reader’s craving for moral and emotional ambiguity and conflict.

While this rule also makes sense for third-person POV, it’s worth stating explicitly that using first-person doesn’t let a writer off the hook with respect to composing a layered, nuanced protagonist. Writing “I said…” or “I believe…” doesn’t equate to simplicity.

Rule #3: DevelopmentFirst-person narrators should undergo change just as their third-person counterparts do. The “I” voice in your story is, by definition, unalterably anchored to one person but that doesn’t mean its essence is fixed from first page to last. To the extent that we get to know this person intimately, to love them or hate them, or even find them unknowable, the narrator still needs to embark on a psychological journey. The self-referential “I” is a constant, but the character’s motives and degrees of self-awareness should fluctuate. Lestat, after all, proves an unreliable narrator with shifting desires—alternately bloodthirsty, smug, ambitious, and remorseful.

Adhering to such rules takes patience, persistence, and a hell of a lot of writing and revision. The author Karl Marlantes (Matterhorn) lamented that a lengthy early draft of one of his novels culminated in “psychotherapy drivel.”

Alas, writing drivel is easy to do when wrangling the first-person voice. Here are some of the POV traps writers often fall into while trying to master the form’s particular aspects of constraint, complexity, and character development.

Pitfall #1: Over-relying on the power of “I”The easiest error is to fall back on sentences that begin with “I” because, after all, you’re in the head of an “I” person. This is a prose-killing mistake. Imagine getting through an entire book with this cadence:

I walked into the living room, where both my sisters were already seated on the couch. I asked them who called this meeting. Sally said she did, but I didn’t believe her. I looked at Toni but she didn’t say a word. I couldn’t wait to get out of there, but I couldn’t leave just yet.

This passage lacks meaningful context and subtext; the “I” here is rather airless. We may technically be locked into one skull, but that’s all the more reason to craft a narrator with the power to imaginatively describe interior and exterior landscapes (physical and psychological) as well as to surmise (or project) what others are thinking and feeling in relation to one another as well as toward themselves. Doing so will help you to de-center your narrator’s consciousness, so that the scene isn’t all about, or only about, them.

In The Fault in Our Stars, John Green accomplishes this by turning “I” into “we” in some scenes, which essentially pulls the camera back away from a perpetual close-up:

Pitfall #2: Sticking readers with a boring narratorWe had a big Cancer Team meeting a couple of days later. Every so often, a bunch of doctors and social workers and physical therapists and whoever else got together around a big table in a conference room and discussed my situation…

If you’re going to lock us into one skull, please let it be a very busy and interesting one. (If you make the first error, you’re likely to make this one, as well.) A dull narrator has banal thoughts, participates in low-stakes events or waits passively for things to happen, and doesn’t do enough to help us get to know other characters, let alone chew on the scenery a little. These narrators aren’t people, they’re weak filters for storytelling. (If they were my tour guides at an exotic locale, I’d fire them.) They lack a distinct point of view and aren’t sufficiently wrestling with their own conscience and the outside world. A boring narrator suffocates the reader and doesn’t do enough work on their behalf. We need people like Mark Watney in Andy Weir’s The Martian, whose fierce intelligence continually shines through while he’s trapped on Mars:

Pitfall #3: Over-limiting what the narrator can know or doFirst, I put on an EVA suit. Then I close the inner airlock door, leaving the outer door (which the bedroom is attached to) open. Then I tell the airlock to depressurize. It thinks it’s just pumping the air out of a small area, but it’s actually deflating the whole bedroom.

This is so damn tricky. One head, one heart. Everyone else is unknowable and your narrator can’t, in fact, see through walls, so how is she to know a murder’s taking place in the next room? In fiction, we can draw on the heightened capacities of all five senses to generate hunches, incite a narrator to action, and create every shade of emotion. We can also deploy time, through flashbacks and other devices, to give our narrator scope to think, feel, and act. A narrator may, for instance, dream that a murder is underway in the next room, and awaken to the sound of muffled screams. Life offers endless possibilities for the “I” character to venture far afield, literally and figuratively. Even interior thought can be made as lively as a high-speed car chase, as in this passage from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre:

What a consternation of soul was mine that dreary afternoon! How all my brain was in tumult, and all my heart in insurrection! Yet in what darkness, what dense ignorance, was the mental battle fought! I could not answer the ceaseless inward question—why I thus suffered…

If you choose first-person, you must let your character get out and about, so to speak, and avoid assuming that we only know what they (literally) see in any given moment.

Pitfall #4: Confusing the narrator with you, the authorWe’re discussing fiction here, not memoir. Every author brings aspects of their own personality into their writing, but don’t reduce your first-person narrator to you. As Doris Lessing observed, “It’s amazing what you find out about yourself when you write in the first person about someone very different from you.” Lessing may be right, but you want to avoid slipping into an intimate “I” voice that turns out to be you—the way you speak, your likes and dislikes, your foibles, unless you’re crafting a roman à clef. Remember that your goal is to create a multifaceted fictional character who lives in, and is shaped by, the world of the book. That’s not you, or your world—or not exactly.

By now, you may feel yourself cautiously backing away from using first-person POV. And to be honest, you’re right to be skeptical. It should not be a default choice, but rather a highly examined one.

Imagine how different the Harry Potter series would seem if J.K. Rowling had elected to let Harry narrate his own hero’s journey. Her choice of omniscient voice defines the books’ collective DNA.

How do you know if first-person POV is right for your story?Begin by asking three key questions. If the answer to any of the questions is a resounding yes (you are as sure as you can be), then first-person POV might be the best choice. If you’re unsure or the answer to all three is no, you’re probably better off avoiding first-person altogether.

Is the main character undergoing an experience, journey, crisis, or series of events that is truly unique? That is, whatever is happening to this character isn’t happening to anyone else, even if others are around to bear witness in some fashion. (The Martian’s stranded astronaut is a case in point.)Have you invented a protagonist with especially sharp powers of observation? Someone who is perhaps very “voicey” or, as Rachel Kushner says, the narrator is “very knowing, so that the reader is with somebody who has a take on everything they observe.” (Think of Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye. He’s too obnoxious to be spoken for in third person.)Do you want the reader to over-identify with the protagonist? Some genre fiction (notably, but not exclusively, romance and detective fiction) deliberately erase almost all distance between reader and protagonist as a way to maximize the reader’s entertainment and enjoyment. Crime writer Patricia Cornwell openly confesses, “In the first person, the readers feel smart, like it’s them solving the case.”Writing a compelling first-person novel requires creative ingenuity, extraordinary empathy, and, I believe, a boatload of courage. Never assume that the “I” voice is the easy way to go, because it never is. But if your heart’s set on charting this course, then please write the most compelling, infuriating, conflicted character you possibly can. Confuse us, infuriate us, and make us fall in love with the skull where you’ve stuck us for the next several hours.

Examples of First-Person Character TraitsExplore some of your choices for the protagonist’s voice

Distinctive/Obtrusive. Opinionated, loud, obnoxious, ditzy, immature, etc. The protagonist’s voice cannot be confused with anyone else’s and the reader is often forced to pay attention to the protagonist’s wants and needs. Comes in handy for unreliable narrators.

Reliable. A truth-teller trusted by the reader. Likely an admirable hero, a character who inspires respect and masters adversity in an ethical way. But we still want complexity and conflict (not Dudley Do-Right). Often shows up as the worthy love interest in a romance.

Reticent/Recessive. Protagonist focuses on others rather than self. The words “I” and “me” are used sparingly and the reader’s attention is not constantly on the protagonist. Female heroines in historical fiction are sometimes deployed in this way. So are neuro-divergent characters, such as Eleanor Olyphant.

Observant. Sharply notices the world around them and reports out with detailed or evocative language. May be a good choice for a novel with many personalities and a lot of action or adventure. Good for complex world-building as well.

Unobservant. Scenery and environs seem to go unnoticed, usually because the protagonist is fixated on other things (interior or exterior). A neurotic (but hopefully entertaining and redeemable) protagonist might fit this bill.

July 25, 2023

Why Preparing a TED Talk Makes You a Better Memoirist (Even If You Never Intend to Get on Stage)

Today’s post is by author and book coach Suzette Mullen.

A couple of months ago I did something that left me feeling somewhere between a wet noodle and a very burnt piece of toast.

Picture a TED talk, with a Zoom room as the stage, and a memoir writer in a fugue state with dry mouth and shaky legs giving a 10-minute talk without notes.

I’d been practicing this talk for weeks as part of a public speaking course that had one simple assignment: put together a signature talk. The talk could be related to your business. Or about a cause you’re passionate about. Or it could simply be your story.

As a memoirist, my story was the logical choice. I had to be able to speak about it succinctly and persuasively on all those podcasts I hoped to be on to promote The Only Way Through Is Out, my memoir about coming out and starting over in midlife (releasing February 2024 from the University of Wisconsin Press). Upping my game to promote my book was the reason, after all, that I had chosen to put myself through public speaking hell in the first place.

Within days of the start of the course, the doubt demons began whispering in my ear:

You don’t have anything worth saying.

Everything you want to say has been said before—and better. Hello? Have you heard of Brené Brown & Glennon Doyle?

Do you even have a story, really?

Ten minutes to tell the story I had written 200-plus pages about. That I had wrestled with for years. That I had written oh-so-many drafts of.

I stared at a blank Google doc.

I had no freaking idea how to condense my story into ten minutes.

I started to question whether I even knew what my story was really about.

Yep, I was questioning this even though I’d written a successful query and gotten a book deal.

Figuring what your story is REALLY about is the biggest challenge for most memoir writers.To borrow from Vivian Gornick, what’s the story beneath the situation?

As memoir writers, we know the situation, the things that happened to us, the plot-level events. We know our subject matter. The grief of losing a long-term partner. What it’s like to come out at midlife and leave a whole life behind. What it’s like to live next door to a serial killer and not know it (as was the case with my book coaching client Jamie Gehring who wrote the true-crime memoir Madman in the Woods: Life Next Door to the Unabomber).

But what are the real stories beneath those situations?

That’s a question every memoir writer should ask themselves before they start writing and continue to ask as they write—and in my case, ask even after the book is finished.

A simple question that isn’t simple to answer.

Instead of bailing on the public speaking course (which I really wanted to do), I went back to basics, to the same steps I coach memoir writers through when we work together.

Here are the steps I took when I was struggling to articulate my story for my ten-minute “TED talk”—and that you can also take at various stages of your memoir journey to get clear on the deeper story you were meant to write:

When you don’t know where to startWhen you are stuck in the messy middleWhen your memoir is complete and you need a list of talking points to promote it1. Make a list of 5–7 key moments and write a short paragraph for each one.These scenes are often referred to as “tent pole scenes,” those key moments that you know will be in your memoir no matter what. If any one of those scenes is removed, the tent (i.e. the story) will collapse.

Here are a couple examples of my tent pole scene paragraphs:

I came out to my mother. Told her I was considering leaving my marriage. She didn’t understand. She thought I was too old to start over. Part of me believed she was right. I had only lived one way for my entire life.

When I confided in my sister, she said, “Suzette, you know how obsessed you get with things.” She implied that this was a phase. That I was having a midlife crisis. It wasn’t a phase or a midlife crisis. Still. Who risks everything for a life they’ve been living only in their head?

Just make a list and write those short paragraphs now.

Don’t worry about the order of the scenes. That will come later.

2. Find the commonalities in these key scenes.What do these scenes have in common? Are there metaphors or images that are repeated? Can you see a pattern in these stories that you didn’t see before?

When I did this exercise, I noticed a pattern of safe choices, the idea of avoiding “bumps in the road,” and the use of the word “glowing” to illustrate how I wanted to feel in my life.

If you’re in the midst of drafting your memoir or you’ve completed your draft, likely you’ve used some image systems or have a number of metaphors running through your draft already.

If you are just beginning your memoir journey, here’s your chance to discover some of those patterns.

3. Choose one commonality and prioritize the stories that illustrate it.Choose the metaphor or pattern that shows up the most in your key scenes. In a 200-page book, you will have several, but remember we’re talking about a ten-minute talk here!

This one thing will be the golden thread to hold your talk (and possibly your memoir) together.

Review your key scene list and move up the stories that best illustrate that pattern or metaphor.

You may be able to layer in another metaphor or idea later, but start with one. Remember, this is a ten-minute talk!

I chose “glowing” as the main idea to center my talk around.

4. Create an arc with your top stories.Now it’s time to turn these separate stories into a capital T Talk that has a beginning, middle, and end. Note, this exact arc may NOT be the eventual one you choose for your memoir, but it should reveal the change in you as the protagonist of this story. It should reveal the essence of the real story you want to tell.

I started my talk with a story of when I was a preschooler and wanted to disappear after I was chastised for breaking the rules, and I ended the talk with a moment when I walked through the streets of my new hometown toward my first Pride event ever, hand in hand with the woman who would later become my wife. And guess what? I was glowing.

5. Make sure you explicitly connect the dots and spell out the message of the story.This is a test for you to make sure that you know the point of your story.

Write 1–3 sentences that directly communicate the message of the Talk. “Tell it” versus “show it.” In a short 10-minute TED talk, we want to bring home the message directly after we’ve illustrated it with stories. You may or may not want to do the same thing in your memoir, depending on your style. The balance of “showing” vs. “telling” can vary dramatically. But for the purpose of your Talk, make it obvious.

Here’s how I spelled out the message of my story:

We are all imprinted by our beginnings, those early memories we hold inside us. I grew up believing that life was about being careful, not making mistakes, following the rules, and avoiding the bumps.I wanted the glow I saw on my friends’ faces—and later I would realize that the glow comes when we are willing to make mistakes, break the rules—feel all the feels—including the bumps.It’s never too late to experience the glow. It’s never too late to live out loud, to live authentically and fully. AND it’s never too late to change your story.Hey, I did have a ten-minute story after all! And it WAS already inside the pages of my memoir—I was just too close to see it at the time.

You have a story too—a story that only you can write. If you are struggling to find it, try out these five steps to get clear on the story beneath the situation. Let me know how it goes! I’ll be cheering you on to find your story in the first place—or rediscover it if you’re lost in the messy middle or even at the end of your memoir journey like I was.

And of course, there’s a sixth step you can take: Pitch your talk! Really, do it! Maybe you won’t find it as terrifying as I did to speak in public without notes. And even if you don’t pitch it now or ever as a signature talk, you’ll have a stable of stories you can pull out for those podcast interviews you’ll be landing for your book launch.

July 21, 2023

Pitch Yourself Before You Pitch Your Book

Today’s post is by author Catherine Baab-Muguira. Join her on Wednesday, July 26, for the online class The Author Platform Accelerator.

So much querying advice is the same. No matter which article you’re reading, which podcast you’re listening to, or even the particular genre you’re working in, the guidance rarely varies: Start with story. Spend your first paragraph hooking ’em with plot, characters, conflict.

It’s fine advice as it goes, but when it reaches this level of ubiquity, a problem arises. Most every writer is pitching agents in the exact same way, and it follows that agents’ inboxes are full of lookalike queries. Under these conditions, is it any wonder that agents rarely respond in any personal way, instead relying on form rejections? Perhaps the reason form rejections predominate is because form queries predominate.

Pause for a moment and imagine you’re an agent. Every hour of the day, every day of the year, your inbox is filling up with queries, and 90% or more of those queries spend the first paragraph breaking out all the usual story details about who’s involved, what’s at stake, yada yada rising action, bla bla bla cliffhanger, ad infinitum. The mind glazes over. To read through it all must feel like you’re singlehandedly bailing out the Titanic, and we all know how that story ended.

I’m familiar with this scenario not because I’m a literary agent but because I spent 12 years querying in the conventional way. Then I stopped, reevaluated, began using a different technique I’d gleaned from my day job in email marketing … and basically everything changed. Within one week of sending out my new query letter to eight agents, I received offers of representation from four of them, at which point I faced the incredibly first-world problem of picking among them.

Granted, I was doing a few things differently, including writing in a new genre, and I cannot say precisely what worked. But having eaten, lived, and breathed email marketing for way too long now, I believe I know. What made the biggest difference was changing my first paragraph, and more specifically, pitching myself first, not my project.

Here’s what that looked like in practice:

Hi, [Firstname]—

I’m contacting you after coming across your profile and realizing that you agented [Book Title] as well as [Book Title]. My name is Catherine Baab-Muguira, and I’m a writer who’s contributed to New York Magazine’s The Cut, Playboy.com, Salon.com and FastCompany.com, among others. My June 2016 Quartz essay, “Millennials Are Obsessed with Side Hustles Because They’re All We’ve Got,” has been shared on Facebook more than 50,000 times and also became the focus of an April 2017 episode of NPR’s On Point.

Why query this way, leading with oneself? Let me count the ways:

For starters, if everyone is querying the same way, there’s likely no advantage in your querying that way, too. Successful querying is about standing out, not fitting in.Professionals tend to want to work with other professionals. If you begin by establishing your professional bona fides, then you’ve cleared a potentially major obstacle, right at the beginning.In the same vein, people tend to care about who’s talking at least as much as what’s being said. It’s a mental shortcut we all use to cut down on noise, and its why email marketers agonize over the “from line” of their messages, over whether to sign an email as though it’s from a particular person or the brand that one is representing, etc. Long marketing lecture short, if you lead with whatever personal information makes you seem the most credible, then you’re putting thousands of years of human evolution on your side. Most importantly, the person receiving your email is likelier to keep reading.Why does this all this matter so much? It’s simple. Nothing is as important as an agent reading past the first paragraph of your query. If they don’t read past your first paragraph, they won’t read your second paragraph—much less your manuscript.

You don’t have to be a freelance journalist like me to approach agents in this way, either. When helping friends with their query letters, I’ve pulled the following wowzer details from the pits of paragraph four up to paragraph one, where they belong:

I was part of a Pulitzer-winning reporting team for the New York Times.I was the first woman ever to make partner at [cutthroat Manhattan law firm].I was a Wall Street analyst who witnessed high-level investment scams.Talk about burying the lede! I only wish I’d had this kind of cred to tout when I was querying. Still, my gnawing professional envy isn’t the point. Are you burying the lede in your query letter, too?

Maybe, like my friends, you have a high-status or relevant job. Are you a public defender, a doctor, a librarian, a Wall Street vet, an advertising copywriter, some other kind of media worker, or a PhD in literally anything?

Or you could have some more unusual and intriguing way of making a living. Maybe you’re a maximum-security prison guard, a backup dancer, or a nanny to some obscenely wealthy and dysfunctional family. Any of that could be interesting, especially if it’s relevant to your project, so consider positioning it front and center. Ditto any significant social-media following (say, 10,000 followers or more) that you may have.

Now, perhaps you don’t have a high-status or unusual job, which is true for many of us. Have you published any short pieces? It only takes two journal publications or freelance bylines for you to be able to say, “I’m a writer who’s contributed to [publication] and [other publication].” Meanwhile, freelancing is relatively easy to get into. Get hustling on that front, and in a few weeks or months, you could be opening your query in a whole new way—coming across like you’re established, legible, seasoned, a pro who knows what’s what.

At the very least, it’s worth thinking through why you might want to defy the conventional (and all too common) querying advice. I don’t know about you, but I get tired just thinking what it must be like to be an agent on the receiving end of endless, highly similar solicitations. It makes me want a beer. And a nap. And a day off. If you’ve been querying a long time—12 years, anyone?—then you might try something new. The change could be as simple as the first paragraph of your query, and your writing fortunes just might change, too.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Wednesday, July 26 for the online class The Author Platform Accelerator.

July 20, 2023

It Might Be Time for a Reality Check on Your Writing Goals

Photo by Robert Șerban

Photo by Robert ȘerbanToday’s guest post is excerpted from A Small Steps Guide to Goal Setting & Time Management by writer and creative writing tutor Louise Tondeur.

“God grant us the serenity to accept the things we cannot change, courage to change the things we can, and wisdom to know the difference.”

Reinhold Niebuhr

A goal assumes you want to change something in your life.

And The Alcoholic’s Prayer suggests that there are some things we can change and some things we can’t—some things we can set goals for and some we’re better off forgetting.

We need wisdom to tell the difference, or a blunt and honest look at ourselves.

Many books on goal setting leave out this step, urging readers to do anything in their power to achieve their goals. But there are two important caveats they seem to forget, and they’re important if you’re going to give your goals a reality check:

Would you really do anything to achieve this goal? Some things may be more important than this goal. It depends what it is. You can be pretty certain that a goal like “stop smoking by the end of the year” has almost no downsides. But would you really risk losing your friends and family or your health in pursuit of a goal?In an age that celebrates so-called eternal youth and the power of the individual whilst telling us we can achieve anything we want to, there are actually some things you can’t do.Different goals for different peopleThis is the secret behind the Alcoholic’s Prayer: pinpoint what you genuinely need or want to change.

For example, I’m never going to qualify for the Olympics. I’m not doing myself a disservice by admitting it and it doesn’t matter how hard I apply myself or how many times I say positive affirmations.

But it’s not all or nothing: almost everyone will improve their lives by exercising a bit more.

So during lockdown I decided to start doing yoga regularly. Looking at my son, I knew I wanted to be fit and healthy enough both to look after him and to watching him grow up. This is a big deal for me because it requires a change of attitude.

For me, “do yoga regularly” is a better goal than “win a medal at the Olympics” or “run the Chicago marathon.” But if you are a prospective Olympian: good luck!

The wisdom to tell the differenceYou’re giving your goals a reality check, but how do you tell the difference between what you can change and what you can’t or what you need to change and what you don’t?

First, get up off the sofa and do something. For example, I started with ten-minute beginner yoga videos on YouTube. An elite athlete might speak to a coach or doctor before undertaking a challenging training program. Make the action something small, but something concrete. Have you:

Spoken to an expert?Been on a short course?Spoken to someone who’s already achieved it?Done your research? Do you know enough about it to know whether this goal is for you?Accepted your limitations?Low risk? Jump in!The next stage in giving your goals a reality check is a risk assessment. Firstly, if the risks and the costs are limited, seek out the opportunity to jump in and try something for a short amount of time with low-risk involvement.