Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 42

October 17, 2023

Amazon’s Orange Banner: The Anticlimax of Achievement

Today’s post is by author Jen Craven.

In a world where success is often measured by external markers and symbols, the pursuit of status symbols can be alluring. Whether it’s the coveted “bestseller” label for authors, or a blue checkmark next to your name, these symbols often come with the promise of prestige and validation.

Confession: I was among these seekers, dreaming of how incredible it would feel to see that orange banner on my book’s Amazon page. Number one. Bestseller. It would be the peak of success, the culmination of years of work and energy.

A writer can dream.

And then I got it. One week after my latest book launch, I woke on a nondescript Wednesday to my novel as the #1 new release, orange banner and all.

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t experience a rush of giddiness. I was on top—figuratively and literally. This was the same badge of honor that adorned so many of my favorite authors’ books. Legit authors with legit careers. Now I could say I was alongside them? Incredible!

And so I blasted it out to social media: Woohoo! I hit #1! [insert string of celebratory emojis]

Congratulations came pouring in, and I reveled in being on the receiving end after cheering on other authors for years. It felt good and fun and all the things.

You might think that’s where the story ends, on a high. Sort of. But not exactly.

Not long after posting my exciting news, a weirdness settled in my gut. Was I really making such a big deal about a silly orange banner? It felt a little like carrying a designer handbag just for the logo. You know it’s what everyone wants, but there are plenty of better bags out there.

I messaged an author friend. “Self-promotion is hard. I feel sort of icky.”

“Absolutely not,” she said.

Another friend expanded the sentiment: “Celebrate the crap out of that banner. You earned it!”

Had I? According to the algorithm, yes. Numbers-wise, my book was entitled to the label. But what did it mean? Was my book “better than” so many others? Better than my friends still riding the querying roller coaster or putting out independent titles?

In a word, no.

And that realization brought with it a swift helping of imposter syndrome. It suddenly felt braggy to be shouting my accomplishment from the rooftops. How cringey to be obsessed with a marker that could disappear the following day. To get it was one thing, but to outwardly promote it? Ew, gross. What I’d once envisioned would be such a pinnacle moment, felt anticlimactic once the high wore off, and if truth be told, I was a little embarrassed for putting so much stock in it. What did such values say about me?

For aspiring authors, the dream of becoming a bestseller is often a driving force that keeps them burning the midnight oil. The idea of seeing your book’s name on the New York Times bestseller list is a powerful motivator, and rightly so. Achieving such a status symbol signifies not only creative success but also the potential for financial gain and widespread recognition.

However, once the dream becomes a reality, authors often find themselves grappling with a sense of emptiness.

“Yeah, it was sort of weird,” a writer friend who’d experienced something similar told me. Turns out, the label of bestseller is, in many ways, fleeting. Books rise and fall on those lists, and the euphoria of hitting the top spot can quickly give way to the anxiety of maintaining that status or the realization that it hasn’t fundamentally changed much at all. We’ve all heard of the sophomore slump, right?

But back to the Instagram post with the ecstatic caption. In the age of social media and personal branding, self-promotion is unavoidable to a degree. After all, many authors view their writing and books as a business. While it’s a necessary part of the journey, it often comes with a sense of awkwardness. Around book launches, I find myself wanting to apologize: Yep, I’m posting my book link again, sorry! Sorry to bug you, but would you mind leaving a review?

Then I remember the words of my wise friend: Books don’t sell themselves.

So, what’s the antidote to the anticlimax of status symbols? It might lie in the pursuit of intrinsic, rather than extrinsic, rewards. For many authors, it means writing for the love of storytelling, not just the pursuit of bestseller status. For others, it might mean finding joy in the process, not just the end result.

All this to say, holding the #1 spot was a cool experience, and it felt damn good, but at the end of the day, I call to mind the hundreds of incredible books I’ve read that have never seen that orange banner. Do I think less of them? Certainly not. And that’s the reminder I carry with me moving forward.

Yes, I’ll continue to celebrate reaching personal benchmarks and outward successes—there’s a difference between being proud and being boastful. But I’ll also operate with the mindset that status symbols do not define my worth or my creativity. The true fulfillment comes from within, from the satisfaction of pursuing my passions authentically and the joy of creating something meaningful.

After all, orange doesn’t go with everything.

October 12, 2023

How Connected Settings Give Your Fiction Emotional Depth

Today’s guest post is by writing coach, workshop instructor, and author C. S. Lakin (@cslakin).

The characters we create in our fictional stories do not exist in a vacuum. We writers, aware of this, create places as stage sets or backdrops for the plot. But all too often these settings are ordinary and boring.

Sad but true, setting in fiction is mostly ignored. It’s as if writers feel they must sacrifice attention to setting to meet the needs of the plot—get the story moving!—but nothing could be further from the truth. The more real a place is to readers, the easier they can be transported there to experience the story.

Whether setting is a huge element in your story because of your premise or not, you can make it powerful and impacting by choosing each place carefully. And by creating what I call “connected settings.”

Connected settings are places with emotional ties to the protagonist or other characters. Connected settings evoke specific emotions that hold meaning and charge the scenes with a unique energy.

For example, it may be that the setting is symbolic of some past life event and serves as a reminder of what happened and the feelings associated with it. Imagine a character being asked to an important business lunch in the same restaurant where his girlfriend turned down his marriage proposal. Even though time has passed, maybe years, an echo of that hurt and rejection will affect him while he’s there and, in turn, will influence his behavior and mood.

Placing your characters in environments where emotions are triggered can also heighten inner and/or outer conflict. If you’re feeling tense in a school principal’s office, discussing your child’s misbehavior, your defenses might shoot up and cause you to take a combative stance—all because you yourself spent many hours in such a situation during your turbulent teen years.

So, how do you go about creating these powerful settings?

Think about the key moments in your novel when your character has the greatest insights, pain, confrontation, or despair. Consider the traumas or difficulties in your character’s past and imagine the places she would have experienced them.Keep in mind the subliminal power of mood. Sensory descriptions, lighting, weather, and universal symbolism all play a part in setting the emotional tone of a scene. By carefully selecting words and imagery that evoke specific moods, we layer more emotional impact via the setting.Consider the high moment of your scene and the plot point you are going to reveal. How should your character feel at the end of the scene? How do you want your reader to feel? What is the best setting to drive home that high moment?Let’s see how these three points come into play in the powerful scene in the movie Minority Report in which the protagonist, John Anderton takes the female Pre-Cog, Agatha, to his former home, which his ex-wife, Lara, still lives in. This is perhaps the moment in the movie in which John faces the most pain, despair, and insight (point #1).

John and Lara broke up years ago because their son was kidnapped and presumed murdered. Now, they hardly speak to or see each other, but John needs a temporary refuge for Agatha in order to solve a crime. I have little doubt this whole scenario was invented just so the couple would be in the same room to face the loss of their child.

Lara and John talk in their son’s room, and for a brief moment it’s as if the fast-action plot comes to a screeching halt in a moment of incredible poignancy. This scene is the very heart of the movie. It’s a highly unexpected moment—for the viewer and the estranged couple. For Agatha stops them in their tracks by saying, “There is so much love in this house.” She then “sees” the future their dead son would have had, recounting, “He’s ten years old … he’s surrounded by animals. He wants to be a vet … he’s in high school. He likes to run. Like his father. … he’s twenty-three and in love …” And on and on she goes, seeing this future that could have been—likely would have been. The mood and tone of this moment is intense, unexpected, shattering and magnificent, all at once (point #2).

Although what Lara and John hear breaks their hearts, it somehow breaks through their pain, so that by the end of the movie they get back together and Lara’s pregnant (but not until a lot of suspenseful minutes pass on the screen!). That scene, so powerful due to the characters’ emotional connection to setting, is paramount in John’s character arc. It is the scene that propels him to the place of needed healing. Without it, he would never get there. He would wallow in misery and drugs forever.

How does John feel at the end of this scene? Utterly broken and yet strangely relieved to drench himself in the pain he’s been burying for years. How does the viewer feel? Tremendously compassionate and empathetic over what John and Lara have gone through (point #3).

Could any other setting have had such a powerful effect on the characters or viewers? What could be more painful than sitting in your dead child’s bedroom, amid all those memories—the sweet memories before the tragedy? How do you think that scene would have emotionally impacted the characters and viewers if Agatha said those words to Lara and John in a crowded Starbucks? Don’t answer that.

Every scene in your story serves a purpose. It’s a stepping stone in your character’s journey, a puzzle piece in your plot’s mosaic. But crafting connected settings is a skill that requires careful consideration and a deep understanding of your characters and plot. Here’s an exercise to help you:

Pick one of your scenes (whether written or at the idea stage).Identify your POV character’s goal for the scene—what must he do, learn, or achieve?Jot down what you want him and the other characters involved to feel.Next, imagine 5 different types of settings where this scene might take place, ones that fit the story and are logical locations for your character to visit. Make a list. Often the settings that come immediately to mind are the most obvious, but with a bit of digging, some more creative and interesting choices can be unearthed too.Once you have a few options, look at each potential setting in turn and think of how you can describe the location to evoke a specific mood that will make your character’s emotional reactions more potent. Tension can be a factor too. Depending on what is about to happen in the scene, you might want your character to feel off-balance. Or maybe you wish to lull him into a false sense of security so he doesn’t see what’s coming. Either way, the details you pick to describe the setting will help steer his emotions.Finally, think about what the character will learn, decide, or do as a result of what happens in the scene. The setting can act as an amplifier for this end result simply by surrounding the character with emotional triggers that will lead him toward that decision or action.By carefully choosing settings that trigger emotions, intensify conflicts, and evoke specific moods, you infuse your story with vivid, unforgettable scenes that keep readers engaged from the first page to the last. Have your settings breathe life into your characters and amplify their emotions, so that your story will linger in the hearts of your readers. Embrace the power of connected settings and watch your fiction come alive.

October 11, 2023

How Can I Set Aside the Cacophony of Writing Advice and Just Write?

Image by Goran Horvat from Pixabay

Image by Goran Horvat from PixabayAsk the Editor is a column for your questions about the editing process and editors themselves. It also features first-page critiques. Want to be considered? Submit your question or submit your pages.

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Plottr. Ditch the index cards and unleash your storytelling with Plottr – the #1 rated book outlining and story management software for writers. Use code JANE15 at checkout for 15% off. (Expires Dec. 31, 2023)

Question

QuestionI attend webinars and online conferences, to learn the craft of writing, though I was a poet in another life back when getting my BA. I was raising a child so hedged my bets by double majoring in developmental psychology and creative writing. Hedging my bets gave me less craft lessons.

Now, an empty nester with a lot of time on my hands, I’ve carefully added authors and writing coaches I follow. I used to follow anyone whom I thought could give me the best answers on writing/memoir. Now, though, my inbox is filled with newsletter advice I can’t possibly find time to read. I want to stick with the two and I know and trust: Lisa Cooper-Ellison and Jane Friedman.

Searching for the one author whose advice is the “key” is fruitless. Yet after a conference I still tend to follow a few speakers and their newsletters. Any advice on how to keep to a couple authors and editors I trust and stop the bouncing around between editor to editor and and settle into a chair and write?

—Elizabeth Undiluted

Dear Elizabeth Undiluted,The great news here is that you already recognize what you need to do: Sit down and write. So why can’t you?

The answer lies in whatever underlying needs, fears/anxieties, and/or feelings of responsibility have been driving you to bounce around. And I must admit, as a long-time advice giver (who has no shortage of qualms about my position as one), I can be at fault in this predicament, along with my colleagues, at making people feel they need to stick around for my guidance.

Let’s cut to the chase: You can get by fine without it. Nothing bad will happen if you stop. Maybe you’ll take a little longer to figure out specific craft challenges. Or perhaps you won’t be as sharp on some business issues. On the other hand, you’re likely to have dramatically less anxiety that you’re doing things wrong, or that conditions in the market aren’t favorable for your work, or that you’re inadequate to the task of marketing and promoting. (A lot of inadequacy that writers feel is driven, IMHO, by advice givers.)

That’s the short answer, but here’s the longer one that explores specific reasons you might be avoiding the writing chair.

You have fear of missing out.Speaking personally, I keep logging onto social media platforms I don’t care about and subscribing to countless newsletters because I feel like I’m going to miss out or become uninformed. That said, it’s literally my job to be informed about what everyone’s talking about in the writing and publishing community. But is it your job? Probably not.

It’s highly unlikely you’re going to miss out on a piece of valuable information or knowledge that would dramatically change your writing fortunes, which you seem to realize. It’s more likely, in fact, you’re going to come across harmful information from people who have no business giving you advice. Most important, a lot of the lessons to be learned about writing come from doing it, from the practice, from showing up. So that’s priority number-one. Everything else is secondary to supporting that effort.

That said, I think your strategy to focus on one or two people you trust is excellent. This gives you some reassurance that if there is something you probably ought to know about, one of these people is likely to bring it to your attention. Or you could ask them to point you in the right direction if a specific need or question arises. (I swear I would say this even if you hadn’t mentioned my name as one of your preferred sources! And thank you for that trust.)

The other thing I’d suggest is that the best advice and guidance still tends to come in either book form or class/workshop form, brought to you by experts you know and trust (or that have been recommended by the experts). This is not to discount the many wonderful newsletters, blogs (like this one!), social media accounts, podcasts, and so on that offer advice. But let’s be honest: Most of it is disposable. If it’s not bringing you joy, if it’s not something you actively look forward to (and especially if it’s something that feels anxiety producing or a burden), it’s time to let go of it.

You need more knowledge to tackle your writing challenges.You mention that hedging your bets gave you less craft lessons, which implies you don’t feel as schooled or as advanced as you would like at this point in your writing life. I would dig deeper into this feeling, if it’s there. Is there something about your current writing project that you’re feeling ill-prepared to tackle? Are you feeling deficient in some area? Is there a weakness you wish you could eliminate?

One of the reasons writers avoid writing is that we don’t know next steps on a writing project. Maybe we’ve written ourselves into a corner or we don’t know where the story is headed and can’t figure out the answer. So when you sit down at your desk, you have no clue where to begin. Or you simply procrastinate to avoid the unpleasant feeling of being stuck.

If you can pinpoint what the writing problem is, then I’d look for books that might help you with a breakthrough. Or, if you have the resources, you could consider hiring a professional editor or coach to help you through the impasse. Alternatively, a class or workshop can help for less cost if you’re surrounded by both a great instructor and sharp students.

There are some writers I meet who simply fear messing up and try to gather as much advice as possible before they even begin. Unfortunately, the writing process is more or less defined by messing up and starting over. Writing is revising. Good writing advice can help you avoid the serious pitfalls, or bring clarity to a confusing process, but creative work of any kind is going to involve countless bad ideas. It’s important to work through the bad stuff to get to the good stuff. (And hopefully you’ve gained enough self-awareness to know when you’ve moved past the bad into the good.)

You want to be a good literary citizen—you owe it to these people.Maybe you’re appreciative of the speakers, teacher, editors, and coaches you’ve learned from. You want to support them, so you subscribe to their newsletters and follow them on social and try to engage. It’s a way to be a good literary citizen, to see and be seen—all good things when you’re trying to make your way in the literary community.

But at some point, your writing has to come first. And you’ll outgrow some of the people you used to learn from. A lot of writing advice, by necessity, is for beginners. It tends to get less useful over time as you become more experienced. The people who give advice know this. No one will get offended if you silently drop away. (And if they do, I humbly suggest they have a lot to learn about the business of helping writers!)

Not writing is more enjoyable than writing.Writing is hard work. I mean, yes, it can be enjoyable, but it’s the joy we take in doing challenging work. It requires mental focus. For memoirists, there’s often the additional challenge of emotional drain.

So it’s natural to look for other things to do instead, especially activities that are writing adjacent, like reading writing advice or gathering with other writers to talk shop or joke around.

We all need a break and we can’t be writing all the time. But if you develop a habit of avoiding the work, especially by reading writing advice or attending conferences and classes, ask yourself why. Then read The War of Art by Steven Pressfield, if you haven’t already, to delve deeply into the psychological challenge of producing art, to recognize how we all pretty much do anything to avoid such work.

You’re trying to prepare now for future problems you don’t have.Don’t focus on problems that exist downstream. Focus on the problem that you face now. The experts will be there when you need them.

Imagine that you haven’t read a piece of writing advice for five years. You haven’t subscribed to any newsletters. You have no clue what you’ve missed. But you wish you had their insight on some new challenge or the next step in your journey. Go to Google and search for your favorite expert’s name, plus keywords related to the problem you’re facing. Presto.

Parting advice on adviceIf you think you have this problem, you probably do. But sometimes I find that writers feel guilty about things that they shouldn’t. They’re in fact making great progress! Except they have this ideal in their head of what a real writer should be doing, and they’re not meeting that ideal. Or there’s just a general feeling of “I should be writing more.”

If this is the case, then you might not need to stop following advice givers, or unsubscribing from their newsletters. Instead, put guardrails on it and maybe you’ll feel better in control. Decide there’s only one time or place you’ll delve into all the newsletters with writing advice. You could set up a separate email account, or set up email rules and filters that file them away in a folder. Then, at the appointed time and place, browse for anything that looks juicy and enjoyable. And anything that doesn’t fit your needs or strikes you as manipulative clickbait? Delete with abandon and return to your writing.

—Jane Friedman

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Plottr. Ditch the index cards and unleash your storytelling with Plottr – the #1 rated book outlining and story management software for writers. Use code JANE15 at checkout for 15% off. (Expires Dec. 31, 2023)

How Can I Set Aside the Cacophany of Writing Advice and Just Write?

Image by Goran Horvat from Pixabay

Image by Goran Horvat from PixabayAsk the Editor is a column for your questions about the editing process and editors themselves. It also features first-page critiques. Want to be considered? Submit your question or submit your pages.

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Plottr. Ditch the index cards and unleash your storytelling with Plottr – the #1 rated book outlining and story management software for writers. Use code JANE15 at checkout for 15% off. (Expires Dec. 31, 2023)

Question

QuestionI attend webinars and online conferences, to learn the craft of writing, though I was a poet in another life back when getting my BA. I was raising a child so hedged my bets by double majoring in developmental psychology and creative writing. Hedging my bets gave me less craft lessons.

Now, an empty nester with a lot of time on my hands, I’ve carefully added authors and writing coaches I follow. I used to follow anyone whom I thought could give me the best answers on writing/memoir. Now, though, my inbox is filled with newsletter advice I can’t possibly find time to read. I want to stick with the two and I know and trust: Lisa Cooper-Ellison and Jane Friedman.

Searching for the one author whose advice is the “key” is fruitless. Yet after a conference I still tend to follow a few speakers and their newsletters. Any advice on how to keep to a couple authors and editors I trust and stop the bouncing around between editor to editor and and settle into a chair and write?

—Elizabeth Undiluted

Dear Elizabeth Undiluted,The great news here is that you already recognize what you need to do: Sit down and write. So why can’t you?

The answer lies in whatever underlying needs, fears/anxieties, and/or feelings of responsibility have been driving you to bounce around. And I must admit, as a long-time advice giver (who has no shortage of qualms about my position as one), I can be at fault in this predicament, along with my colleagues, at making people feel they need to stick around for my guidance.

Let’s cut to the chase: You can get by fine without it. Nothing bad will happen if you stop. Maybe you’ll take a little longer to figure out specific craft challenges. Or perhaps you won’t be as sharp on some business issues. On the other hand, you’re likely to have dramatically less anxiety that you’re doing things wrong, or that conditions in the market aren’t favorable for your work, or that you’re inadequate to the task of marketing and promoting. (A lot of inadequacy that writers feel is driven, IMHO, by advice givers.)

That’s the short answer, but here’s the longer one that explores specific reasons you might be avoiding the writing chair.

You have fear of missing out.Speaking personally, I keep logging onto social media platforms I don’t care about and subscribing to countless newsletters because I feel like I’m going to miss out or become uninformed. That said, it’s literally my job to be informed about what everyone’s talking about in the writing and publishing community. But is it your job? Probably not.

It’s highly unlikely you’re going to miss out on a piece of valuable information or knowledge that would dramatically change your writing fortunes, which you seem to realize. It’s more likely, in fact, you’re going to come across harmful information from people who have no business giving you advice. Most important, a lot of the lessons to be learned about writing come from doing it, from the practice, from showing up. So that’s priority number-one. Everything else is secondary to supporting that effort.

That said, I think your strategy to focus on one or two people you trust is excellent. This gives you some reassurance that if there is something you probably ought to know about, one of these people is likely to bring it to your attention. Or you could ask them to point you in the right direction if a specific need or question arises. (I swear I would say this even if you hadn’t mentioned my name as one of your preferred sources! And thank you for that trust.)

The other thing I’d suggest is that the best advice and guidance still tends to come in either book form or class/workshop form, brought to you by experts you know and trust (or that have been recommended by the experts). This is not to discount the many wonderful newsletters, blogs (like this one!), social media accounts, podcasts, and so on that offer advice. But let’s be honest: Most of it is disposable. If it’s not bringing you joy, if it’s not something you actively look forward to (and especially if it’s something that feels anxiety producing or a burden), it’s time to let go of it.

You need more knowledge to tackle your writing challenges.You mention that hedging your bets gave you less craft lessons, which implies you don’t feel as schooled or as advanced as you would like at this point in your writing life. I would dig deeper into this feeling, if it’s there. Is there something about your current writing project that you’re feeling ill-prepared to tackle? Are you feeling deficient in some area? Is there a weakness you wish you could eliminate?

One of the reasons writers avoid writing is that we don’t know next steps on a writing project. Maybe we’ve written ourselves into a corner or we don’t know where the story is headed and can’t figure out the answer. So when you sit down at your desk, you have no clue where to begin. Or you simply procrastinate to avoid the unpleasant feeling of being stuck.

If you can pinpoint what the writing problem is, then I’d look for books that might help you with a breakthrough. Or, if you have the resources, you could consider hiring a professional editor or coach to help you through the impasse. Alternatively, a class or workshop can help for less cost if you’re surrounded by both a great instructor and sharp students.

There are some writers I meet who simply fear messing up and try to gather as much advice as possible before they even begin. Unfortunately, the writing process is more or less defined by messing up and starting over. Writing is revising. Good writing advice can help you avoid the serious pitfalls, or bring clarity to a confusing process, but creative work of any kind is going to involve countless bad ideas. It’s important to work through the bad stuff to get to the good stuff. (And hopefully you’ve gained enough self-awareness to know when you’ve moved past the bad into the good.)

You want to be a good literary citizen—you owe it to these people.Maybe you’re appreciative of the speakers, teacher, editors, and coaches you’ve learned from. You want to support them, so you subscribe to their newsletters and follow them on social and try to engage. It’s a way to be a good literary citizen, to see and be seen—all good things when you’re trying to make your way in the literary community.

But at some point, your writing has to come first. And you’ll outgrow some of the people you used to learn from. A lot of writing advice, by necessity, is for beginners. It tends to get less useful over time as you become more experienced. The people who give advice know this. No one will get offended if you silently drop away. (And if they do, I humbly suggest they have a lot to learn about the business of helping writers!)

Not writing is more enjoyable than writing.Writing is hard work. I mean, yes, it can be enjoyable, but it’s the joy we take in doing challenging work. It requires mental focus. For memoirists, there’s often the additional challenge of emotional drain.

So it’s natural to look for other things to do instead, especially activities that are writing adjacent, like reading writing advice or gathering with other writers to talk shop or joke around.

We all need a break and we can’t be writing all the time. But if you develop a habit of avoiding the work, especially by reading writing advice or attending conferences and classes, ask yourself why. Then read The War of Art by Steven Pressfield, if you haven’t already, to delve deeply into the psychological challenge of producing art, to recognize how we all pretty much do anything to avoid such work.

You’re trying to prepare now for future problems you don’t have.Don’t focus on problems that exist downstream. Focus on the problem that you face now. The experts will be there when you need them.

Imagine that you haven’t read a piece of writing advice for five years. You haven’t subscribed to any newsletters. You have no clue what you’ve missed. But you wish you had their insight on some new challenge or the next step in your journey. Go to Google and search for your favorite expert’s name, plus keywords related to the problem you’re facing. Presto.

Parting advice on adviceIf you think you have this problem, you probably do. But sometimes I find that writers feel guilty about things that they shouldn’t. They’re in fact making great progress! Except they have this ideal in their head of what a real writer should be doing, and they’re not meeting that ideal. Or there’s just a general feeling of “I should be writing more.”

If this is the case, then you might not need to stop following advice givers, or unsubscribing from their newsletters. Instead, put guardrails on it and maybe you’ll feel better in control. Decide there’s only one time or place you’ll delve into all the newsletters with writing advice. You could set up a separate email account, or set up email rules and filters that file them away in a folder. Then, at the appointed time and place, browse for anything that looks juicy and enjoyable. And anything that doesn’t fit your needs or strikes you as manipulative clickbait? Delete with abandon and return to your writing.

—Jane Friedman

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Plottr. Ditch the index cards and unleash your storytelling with Plottr – the #1 rated book outlining and story management software for writers. Use code JANE15 at checkout for 15% off. (Expires Dec. 31, 2023)

October 10, 2023

How to Create Character Mannerisms from Backstory Wounds

Photo by Roman Trifonov on Unsplash

Photo by Roman Trifonov on UnsplashToday’s post is by author and book coach Janet S Fox.

The best way to deepen and enrich our characters is to develop them from long before they enter the story we’re writing. Every character (really, every human being) struggles with one or more wounding experiences that create life-long emotional responses. These backstory wounds result in the lies our characters tell themselves, or what Lisa Cron in Story Genius refers to as “misbeliefs.”

By borrowing from acting techniques, especially those developed by Konstantin Stanislavski, writers can follow a logical sequence of development to create a character that feels real and alive while their wound and misbelief may remain buried and invisible—even to the character.

Backstory wounds in actionBackstory wounds come in all shapes and sizes, but they share one thing in common: Whether seemingly trivial or clearly debilitating, the wounding experience is unforgettable and causes lasting pain. The wounding can be singular or repeated, and because we each experience pain in our own way, even small wounds can be damaging. Examples include bullying, abuse, poverty, loss of a loved one, physical disability, fear during a natural event, failure.

Because we process pain by trying to make sense of it, we turn to self-reflection, and that can quickly turn into self-blame. Self-blame forms the lie or misbelief that dominates all future behaviors.

Here’s an example of the wound and the misbelief in action in a character:

A child witnesses her father leave when her parents divorce. She reflects that the divorce must be her fault—she was naughty, or cranky—and the lie that forms is “My dad left me and Mom because he doesn’t like my behavior, so I must be defective.”

The lie begins to emerge as a statement of fact: “Defective people (like me) can’t form relationships.” This fact perpetuates fear: “I’ll be abandoned again, because I’m defective.” And fear of further wounding holds this character in thrall: “To keep myself from being abandoned again, I won’t form relationships at all.”

This character will grow up with an emotional shield that could result in all sorts of possible character arcs: a cold woman who callously murders her partners; a broken woman who hops from one affair to the next; a timid woman who walks away from any possible partner; and so on.

Character behaviors and traits emerge from the woundCharacter behaviors are patterned by the character’s emotions that result from the misbelief. Actors study human behavior to develop mannerisms or tics that are outward physical manifestations of those misbelief-generated emotions.

We can use the same sequence of developing our characters to create mannerisms, traits, and tics that reflect their deep-seated emotions in a way that shows the wound and misbelief emerging through those gestures.

Here’s the step-by-step exercise to help you uncover your character’s wound, its lasting impact, and how it reveals itself through your character’s actions on the page.

Choose your character, and brainstorm 5 possible wounding backstory events for that character. Try to make them each a little different, with different impact. Remember that these events happened long before the start of your story.Choose what feels like it could be a powerful event for your character and write a full scene around it. You may or may not use this scene in your story; if you do I suggest burying it deep in the narrative.Identify the lie or misbelief that results from the wound that emerges from this scene. For example, bullying might result in the lie that your character must protect himself.Identify the lasting emotions in your character that are produced by the lie. The bullied kid feels that to protect himself, he must act tough; or, he might fear that trying to protect himself will lead to abuse.Identify the behaviors that result from those emotions. The tough kid might bully other kids, or take up boxing, or wear clothing that feels/looks like armor; or the fearful kid might run and hide from any conflict.Identify the mannerisms, traits, or tics that result from those behaviors. The tough kid might affect a swagger, or a sneer. He might wear all black. He might push others out of his way in his rise to the top. He might abuse substances, or conversely refrain from them in order to be fully in control. The fearful kid might have a speech impediment, or an odd way of not looking directly at others, or he might have OCD.To take this back to our woman who was wounded by divorce, she may have traits like standing rigidly and speaking forcefully, or tugging on her sleeves as if to hide her skin, or insisting on perfection in everything and everyone around her because being less than perfect results in abandonment.

The traits that define your character will rise directly from their wound.

The causal chain of backstoryAs you can see, the wounding experience results in multiple possible misbeliefs, which results in multiple possible emotional responses, and so on. Think of this as a branching tree or hierarchy diagram in which each step allows you to pursue the best possible path for your character in terms of your intention. The choice is yours as to how your character responds to the wounding experience and will be based in how you see the emotional, internal arc and its impact on the external conflict arc of your story.

The growth in your character over the course of her journey may be reflected in changes in her emotions, behaviors, and mannerisms, which will subtly convey (by showing, not telling) her emotional arc to your readers.

You’re creating a cause-and-effect chain by starting with something that happened to your character long before page one. Each link you add to the chain will add depth to your character and her emotional journey, and depth to your story as well.

October 4, 2023

The Flashback: A Greatly Misunderstood Storytelling Device

Photo by Hadija on Unsplash

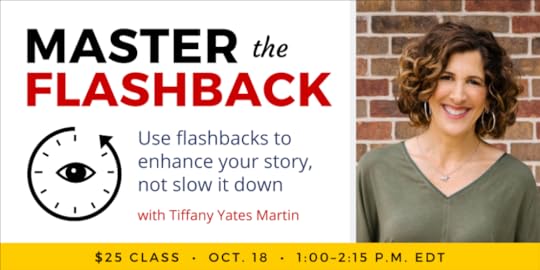

Photo by Hadija on UnsplashToday’s post is by editor Tiffany Yates Martin (@FoxPrintEd). Join her on Wednesday, Oct. 18 for the online class Master the Flashback.

They’re the bogeymen of publishing. Along with prologues, adverbs, and semicolons, flashbacks may be the most vilified—and most misunderstood—of storytelling devices, ones that work only if they don’t seem like devices.

Yet flashbacks are inherently artificial. Even when we are revisiting memories in life, we rarely replay an entire scene from start to finish, chronologically and in full detail. Memory doesn’t work that way; it’s slideshows and not a movie.

But one prime reason that flashbacks are a common literary convention is that, used well, they can be an effective way to present essential information and backstory. Readers have become trained, as with so many fictional devices, to accept the artificiality of flashback provided it doesn’t interrupt their experience of the story.

And there is where the trap lies that so often derails an author’s attempt to use flashback: If not woven seamlessly into the flow of the story, a flashback can draw attention to itself, reveal the author’s hand, and pull the reader out of the fictive dream.

But you don’t have to avoid this potentially potent device as long as you follow a few key guidelines in weaving flashbacks seamlessly into your story.

1. Determine whether a flashback is in fact necessary.Before you start wielding this potent and potentially disruptive weapon, let’s examine why you want to brandish it at all. Flashback is like cayenne pepper—a little bit can add spice and depth to the stew; too much can overwhelm it.

The main misstep I see in flashbacks is using them as backstory dumps of information authors think readers need to know to understand the story or characters. That may in fact be the case, but paving in background via flashback can be like wielding a machete where you needed a scalpel.

There are three main forms of introducing backstory:

Context: This is information woven into the main story throughout, often so seamlessly you don’t even realize how much information you’re getting amid the forward movement of the story.Memory: When characters call to mind details from their past—still within the action of the “real-time” main story.Flashback: A scene from the past presented as if it’s happening “live” before readers’ eyes, which fully interrupts the main story.It’s this last form that makes flashbacks so dangerous. Used unskillfully or too often, they lend an erratic feel and potentially compromise readers’ engagement.

A good, healthy chunk of the time (let’s say 80–85 percent, because you can’t really quantify story with math, but it sounds right), context is going to be the most fluid, seamless, and organic way to incorporate backstory. The rest of the time memory is the most effective device.

That remaining little sliver is where flashbacks come in.

So when you use them, use them judiciously—like that cayenne pepper. Ask yourself what makes flashback the strongest way to incorporate the backstory, worth its many risks. That will often be one of several reasons:

It’s an essential, defining element of the character’s past relevant to the current story and their arc—like their main “wound” or a formative event that dictates or materially affects the character’s journey in this story.It’s a “secret” or reveal that’s finally being fully shared—one central enough to the main story to warrant a full dramatization.It’s brief, woven into a “real-time” scene, and serves to heighten impact, stakes, or meaning in the main story. Often this type of flashback will be just a few paragraphs.2. Determine the most effective placement for a flashback.The most challenging place for a flashback is opening your story. It can disorient or confuse readers—like walking into a room looking backward—and risks feeling like a false promise of what the story is actually about. That said, an opening flashback can work if used deliberately and well, and usually kept ruthlessly short.

There are no real “rules” or systems for where to place a flashback, but a good guideline with all backstory is to ask yourself my version of the “Watergate question”: What does the reader need to know and when do they need to know it?

Overloading readers with backstory before we’re fully invested in the main story hamstrings its effectiveness. The author’s job is to find where a flashback most effectively serves and furthers the main story by offering essential backstory at the most impactful, germane time—which ties into the next guideline.

3. Move the story forward, both within the flashback and in the main story.Imagine a friend is telling you the harrowing tale of her recent car accident when she stops suddenly to relive shopping for that car just days earlier.

That fact may be relevant to heightening stakes and impact for the wreck—dammit, it was her brand-new dream car!—but in the middle of the much more relevant action of the story it stops momentum cold.

This is when flashbacks fail, as if the author is putting the main story on ice while she takes the reader on a journey down Memory Lane.

It’s the trickiest balancing act. Authors should use flashbacks in a way that still move the main story forward, even as we are briefly glancing backward.

That means the flashback should not only encompass its own strong forward momentum within the scene it presents, but its use at its particular point in the story should also serve to move the main story forward—usually in one of the ways described above.

4. Transition smoothly into and out of the flashback.Here’s the make-or-break logistical challenge in flashback deployment: You must fluidly guide readers both into and out of it. That means avoiding a clumsy introductory device like “She remembered it as if it were yesterday” or “The scene unfolded in her mind like a movie…”, or plopping us back into the story afterward with an awkward, “Back in the present…” or “She shook her head to clear the memory.”

There are two common ways to incorporate flashback fluidly: Anchor some key aspect of the flashback in something that’s happening in the current moment. Or, with standalone flashback scenes, a space break is sufficient to set it off as a separate scene from the past. But it’s still useful to segue in and out in a way that ties it to the main story without hanging a lantern on the transition. Learn more here about weaving flashbacks seamlessly into your story.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Wednesday, Oct. 18 for the online class Master the Flashback.

October 3, 2023

Get Started With Dictation: Choosing the Best Techniques and Tools for You

Today’s post is by Sarah Elisabeth Sawyer. She teaches a Dictation Bootcamp for Authors beginning October 17, 2023.

If you’ve heard of authors experiencing tremendous success with dictation but you don’t have a clue where to start, you’re in the right place, my friend.

Yes, there is a plethora of ways to approach dictating your next book, and all of those ways can feel intimidating if you haven’t successfully dictated yet.

Here we will cover:

Picking the best dictation techniquePicking the best dictation toolPicking the best dictation settingI had tried and failed to master dictation multiple times before finally discovering what worked for me. I’ll share some of what I’ve learned to dictate ten books—and counting.

Dictation techniquesThroughout the years of my writing journey, I identified three methods you can employ when dictating:

Watching the screen as you speak your wordsNot watching the screen as you speak your wordsRecording your words and transcribing laterThe first one many people are familiar with. If you’re on your computer using the built-in speech-to-text option (like I’m doing for this post), your words will appear on the screen as you speak them.

The pro to this method is the same as typing your words on the screen. You get to see what you’ve written as soon as you’ve written it.

The con: your inner editor distracts you from drafting your piece.

It’s doubly hard with dictation as you watch errors appear. Homonyms, misspelled character names, incorrect punctuation. These not only drive your inner editor mad, but it can be plain distracting as you try to form the next sentence in your brain.

This doesn’t mean you can’t use the built-in speech-to-text option on your computer or phone to dictate a story. Simply don’t look at the screen.

Which brings us to the second method: Not watching the screen as you speak will keep you in the creative flow as you get down your first draft.

I’ve done dictation long enough for fiction and nonfiction that both methods work for me. However, I prefer to not watch the screen as I speak my words. It’s just too distracting. The danger, however—as I’ve discovered more than once—is if my dictation software halts. Generally, it will make a little ding noise when that happens, but not always. So I could be dictating away only to discover nothing has been captured for several minutes.

To remedy this, I’ve trained myself to check the screen subconsciously to make sure the dictation function is operating correctly.

One final method eliminates that issue: You can dictate your words into a recording device and have it transcribed later. It’s an old-school method (as in dictaphones before smartphones) that works extremely well today.

I know of authors who still use dictaphones to record their words while on a walk or loading groceries in the car. Afterward, some employ a human transcriber and some use software for the transcription.

That brings us to the tools of dictation.

Dictation toolsDon’t worry, we are not about to break your author bank in this section!

For years, I allowed the idea of expensive dictation software to hold me back from speaking my stories. I couldn’t justify spending hundreds of dollars on software when I didn’t know if I could master dictation mentally.

What I discovered after many failed attempts was that the smartphone in my pocket was a much better asset than I gave it credit for. I stumbled onto what worked for me by accident.

In my freelance work, I record interviews for later reference when writing a story. I found a neat little app for my iPad called Voice Recorder and used that for years.

The app eventually offered an upgrade to transcribe the recordings.

Ding!

Given my struggles with dictation, I decided to give it a try and found that the transcription option was remarkably accurate. It was far from perfect, but enough to get me on the road to mastering dictation.

The app today requires a monthly subscription fee of $3. To me, it’s a tiny investment for a tool that can revolutionize your writing life.

The app is far from the only one to offer this kind of power. For my most recent manuscript, I simply dictated with the built-in function on my new iPhone 13. This worked remarkably well, too.

The point is, you do not need to let expensive tools or complicated technology hold you back from incorporating dictation into your writing life.

Dictation settingThe right setting can be critical to our creative flow. Experienced or prolific writers generally can write anywhere, anytime. But not all.

Some swear by routines and the appropriate setting and time to get their stories in. For the most part, you can write in any setting with dictation. Yes, the noise of a coffee shop or a park may make it more challenging, but again, the technology is getting better and better. My iPhone “zooms” in on my voice when I hold it close to my mouth. You can also invest in a headset that gets you a microphone very close to your mouth to overcome external noises.

The benefit of dictation over typing is you can write in even more settings.

Write while walking a nature trail. Write while washing the dishes. Write while laying on your side in bed, eyes closed and fully envisioning the story (my favorite method when writing fiction).

While a quiet place is ideal, just like with any method of writing (by hand, typing, or dictating), you can learn to write in almost any setting.

I prefer privacy when writing, but I’ve done all three in public—typing and dictating and writing by hand.

Dictation can free youLike me, you may have tried to master dictation multiple times. We face huge mental blocks, especially when it comes to dictating fiction. But I want to encourage you to give it another try!

Just start here:

Take out your smartphone right now.Open your messages app and tap your speech-to-text or dictation function.Speak one sentence to a loved one or a writing buddy. Just a “Hi, how’s your day?” will work.Edit if needed and send it.Congratulations! If you did the above, you have begun your journey to mastering dictation.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, consider joining Sarah’s Dictation Bootcamp for Authors beginning October 17, 2023.

September 28, 2023

The Other Pitch Packages Authors Should Prepare

Photo by Vladislav Klapin on Unsplash

Photo by Vladislav Klapin on UnsplashToday’s post is by author Amy L. Bernstein.

When we talk about “pitch packages” in publishing, we’re usually talking about an author’s query letter and synopsis (for fiction), or a book proposal (for nonfiction).

These are standard elements that every author, with a bit of research and consultation, can learn about and craft for themselves or, better still, with assistance from an editor or book coach.

Then there are the other pitch packages that many authors don’t think about, but come in mighty handy as you begin laying the groundwork months before your book is published and even after it’s out.

To some extent, these other pitch materials are a mix-and-match affair. Borrow one phrase from column A, one from column B, and make something new. But pay attention to the nuanced distinctions among them as you write—for as the audience, placement, and formatting varies, so too must the sequence, tone, and scope of your language.

Here’s a rundown of four other pitch packages you will need before, during, and after your book comes out, roughly in order of importance and utility.

1. Podcast pitchWhether or not you are an avid consumer of podcasts, being a guest on a podcast is one of the most effective ways for an author to make an impression on potential readers—and to do so on a reasonably large scale. There are 464.7 million podcast listeners globally as of 2023. This number is predicted to reach 504.9 million by 2024. The share of the U.S. population that listened to a podcast within the last week has skyrocketed from about 7 percent in 2013 to 26 percent in 2022. Only a fraction of these, of course, are geared toward conversations with authors, but that fraction reaches hundreds of thousands of listeners, at a minimum.

Therefore, pitching podcasts should be central to your pre- and post-publication marketing strategy—whether you’re self-published or working with a top publisher.

In some cases, your publisher or PR rep will help get you booked on podcasts. But that’s the exception rather than the rule. The vast majority of authors need to manage this task independently. Finding podcasts to pitch is a topic for another article (hint: it’s remarkably easy to do, given the proliferation of free and subscription-based podcast matching services). But that’s only half the battle. Competition to land a guest spot can be fierce and many hosts book guests six months or more in advance. So you’ll want to plan carefully based on your publication schedule.

To pitch confidently, you need two things: A short email pitch and a companion video (via Zoom, YouTube, Vimeo, or another easy recording platform) that showcases your voice, style, and approachability. (Here’s my all-purpose pitch video, by way of example.)

But first things first. Know your purpose (or purposes) in seeking a guest spot and prepare to share key information:

Do you want to discuss just one book or a body of work?Can you clearly and succinctly describe your brand as an author?Are you willing to discuss broader topics related to genre, your writing process, marketing, self-publishing, and so forth?Do you have expertise to share in areas beyond your author identity? For example, I often discuss book coaching, offer writing craft advice, and how to live a creative life in mid-life.Once you are clear on discussion parameters it’s time to research shows with a relevant track record of programming. Then write an email pitch that:

Acknowledges the host’s areas of interest (citing a prior show is a bonus) and why you’re a good fit.What you’d like to discuss. As with a query letter, this should be short, targeted, and compelling. Be specific and sharpen your hook. Don’t sell your book—sell an idea, a topic, a fascinating question to explore.Note why listeners would find this interesting or noteworthy.Mention any prior experience on podcasts or, short of that, any public speaking you’ve done.Provide a link to your pitch video if you have one.2. Book blurb solicitationTraditional publishers will seek praise quotes (endorsements or blurbs) for your book ahead of publication. This isn’t a review, but a sentence or two highlighting the book’s value and impact, the best of which lands on the cover. You should augment that effort by reaching out to other authors, experts, and influencers on your own. (My publisher believes it’s more effective for authors to reach out directly, but there’s room for debate.)

Honestly, this is hard because it means asking a stranger (in most cases) for a favor—and that stranger may be a celebrity or successful author in their own right. How dare you approach them?

Requesting a blurb is a delicate ask. Pitching by email (especially if you can find a direct contact) is much better than messaging someone on social media, which often feels spammy. (That said: I sent a preliminary pitch to someone on Mastodon and he responded positively. So never say never.)

Your solicitation is structured similarly to the podcast pitch, but I suggest you treat this communication a bit more formally. Keep it short and adopt some or all of this etiquette:

Your first sentences should make it clear how and why you value this author’s work. One trick I use is to share a brief quote from one of the author’s books that speaks to me—and which is relevant to my own book. Don’t overdo the flattery and do not introduce your book or your credentials in the first paragraph.In the second paragraph, put your book in a context that will resonate with this author: Does your story or area of expertise track closely with theirs? Did their work inspire yours? Are you trying to carry their legacy forward in some way? Establish a connection so that you avoid the appearance of reaching out at random. Draw on your hook-for-the-book language to help with this. In the final paragraph, let the author know you’d be grateful if they’d consider writing a short blurb for the book, and that you’d be happy to send it along. Do not attach a file with this solicitation. You can embed an image of your book cover in the body of the email, if you wish. Offer a fairly long lead time—at least three months, though six is better—and make sure that’s a request, not an expectation.3. All-purpose teaser copyYou’re going to need this boilerplate far more often than you may realize. This little mash-up of log line, synopsis, and teaser will serve a number of purposes, including for:

Social media posts, combined with a cover image and a link for pre-orders or direct sales.Soliciting advanced review copy (ARC) readers.Sharing book news informally with your personal network (family and friends).Embedding in a newsletter—yours or another author’s as part of, say, a newsletter swap.Using in a blog post to introduce or discuss the book.Turning into a business card or postcard for conferences and festivals.Using in cover letters as part of a submittal package to a literary magazine to run an excerpt. This is typically helpful when submitting through Submittable.Typically, your all-purpose teaser copy opens with a log line—a punchy sentence or two that captures the “feel” of the book, rather than the plot. This is followed by a very short plot/story synopsis (maybe four sentences) that doesn’t reveal how the book ends but offers the reader a hint or tease about the stakes.

4. Elevator pitchWhen someone asks what your new book is about, don’t get caught stammering! Borrow from your all-purpose teaser, or your log line, or even your book jacket to craft a short, fun answer that you can recite from memory. Use the opportunity to make a strong impression. You never know where that will lead.

Crafting all these pitch packages may seem like a lot of work, and it can be. But you’re making a suite of materials that borrow from one another. If you already have tight book jacket copy, you can borrow some of that for the all-purpose teaser. If you’ve already dropped a log line into your standard agent query letter, then that’s another piece already made.

Parting adviceAbove all, never lose sight of who you’re pitching to and why you want their attention. Oddly enough, the substance of any pitch package isn’t about you, it’s about your work and why it will resonate with others. So customize your pitch for the intended recipient.

September 27, 2023

Is It Worthwhile to Write My Memoir, Especially If a Publishing Deal Is Unlikely?

Photo by Pavel Danilyuk

Photo by Pavel DanilyukAsk the Editor is a column for your questions about the editing process and editors themselves. It also features first-page critiques. Want to be considered? Submit your question or submit your pages.

Today’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Book Pipeline. Editors reviewing unpublished fiction and nonfiction through the Book Pipeline Workshop. “Recommend” submissions are considered for circulation to lit agents and publishers. Learn more and submit—and use code Jane50 for an exclusive $50 off a Pitch Package review! (Ends Oct. 31.)

Question

QuestionIn the eighth decade of my life and after having three books traditionally published—a travel memoir 50 years ago and two novels more recently—I am pondering the wisdom of writing a very personal memoir.

What has moved me most to think about this is the #MeToo movement: I was the victim of date rape while working as a civilian employee on an American army base in France from 1963–1964. While my time in France was indeed a wonderful one, a dream come true, tarnished only by this one incident, I sometimes reflect on the high percentage of women who have suffered sexual abuse, many while serving in the military. I was advised not to report this case by my immediate superior with the very real threat that the perpetrator (an officer) most likely would not be punished, and it would likely mean the loss of my job.

The memoir I am thinking of and which I have partially written is about much more than this incident; it is also about the loss of innocence and the excitement of discovering a foreign culture. It includes the story of my first true romance, an interracial affair. I was the “innocent” white girl in love with an African American enlisted man—two “no-no’s” for I was told during my training that it was absolutely not advised to date enlisted men, but only officers, “men of a higher caliber.” Race was not mentioned but implied by the times and by several other statements. These experiences in addition to the opportunity I had to develop wonderful life-long friendships with several French citizens prompts me to want to share them in a memoir. I would like to know if this is worth my writing; would it be received well or would you offer a caveat to me, to avoid what may be a well-worn subject matter?

—Memoirist with a Dilemma

P.S. I would love to have a traditional publisher if I do finish this memoir, but in today’s world, I think it is highly unlikely I would find one interested in an octogenarian author.

Dear Memoirist with a Dilemma,Oh my goodness, there are so many layers to this question!

I think I want to start by saying that even if #MeToo feels like it’s run its course, even if it feels like the publishing world is tired of women’s stories about rape, or maybe just tired of women’s stories or memoirs, period…I assure you, the market is not oversaturated with memoirs by women in their eighth decade.

Which, as you know, doesn’t mean there’s an easy path ahead of you. The publishing world may not be receptive to a memoir like this for any number of reasons—some of which might be valid and some of which are utter bullshit. Your age might be one of those reasons, but it’s not the only one. Publishing is a highly uncertain field with few guarantees, and the market for memoirs can be particularly uncertain.

As it happens, I’m writing this response on Labor Day, so in answering your question about the value of writing a memoir—and about the worth of writing—I do first want to acknowledge writing (and art-making, generally) as a form of labor that, like any labor, should be fairly compensated, monetarily.

That said, for better and worse, many artistic and writing projects fall largely outside the realm of capitalism. Recently, I was listening to one of the first episodes of the “Wiser Than Me” podcast*, hosted by Julia Louis-Dreyfus; it’s an interview with Isabel Allende (who didn’t start writing novels until 40), who channeled Elizabeth Gilbert giving advice to young writers—which you are not, but maybe this is actually just decent advice for any writer: “Don’t expect your writing to give you fame or money, right? Because you love the process, right? And that’s the whole point, love the process.”

Which is just to say that, if you’re asking whether writing this memoir is likely to justify your time and energy, financially—well, unfortunately, that’s probably a very short response letter. It’s almost certainly not.

But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t write it, or that writing this memoir would be unwise, in some way, or unworthy of your time and energy. The answer, here, lies in the why. Why do you want to write this memoir?

Do you love the process? Do you think you’ll feel better about the world on the average day when you’ve sat down to work on this book than on a day when you haven’t? Do you enjoy writing more than you don’t enjoy it?

If your answers to those questions are enthusiastically positive, then that’s reason enough to write.

There might be other, even more significant reasons to dive fully into this project. Writing a memoir isn’t therapeutic, per se, but the process of writing and rewriting our personal stories can be a rewarding process, one that’s often full of (good) surprises.

In this case, you’re talking about revisiting experiences—including an assault—after 60 years; the opportunity to reshape your story and to reconsider what you make of it might be incredibly meaningful. Indeed, it sounds like you’re already doing this to some extent, inspired in part by the #MeToo movement and other people’s sharing of their stories. One of the reasons #MeToo took off was because it defused and transformed a particular kind of shame and loneliness an awful lot of women had been sitting with for too long. Perhaps you, too, have been feeling that way.

Does revisiting this time and your experiences—the many good ones as well as the bad one—and considering them from fresh and maybe unexpected angles sound appealing and useful? Again, if your answer here is an enthusiastic yes: what are you waiting for?

(This might be an unpopular opinion, but for what it’s worth, I think it’s also completely valid to say, “Nah, I don’t need to relive all that.” But I think you wouldn’t have written in with this question if that were how you felt about it.)

Ultimately, both of those reasons are sort of personal and maybe even a little self-centered. And so what if they are? After all, as Mary Oliver put it in “The Summer Day” (which she wrote at age 62), “What is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?” You really don’t have to please anyone but yourself.

But I also understand that writing a memoir solely for the pleasure of it might not feel entirely satisfactory, either. We want our stories to make connections, and to matter to someone, right?

So I would ask, again, why you want to write this memoir. What kind of impact do you want to make, and on whom? And, once you’ve articulated those answers in some detail, maybe there’s another question to ask, which is whether writing a memoir is the only way to tell the stories you want to tell.

There’s self-publishing. There’s blogging. There’s sharing on social media. Maybe you want to write a collection of shorter pieces, which you could place individually in literary publications or anthologies. If one of your goals is to contribute to a richer, more nuanced history of the military and/or #MeToo and/or racism in our country and its institutions, there are organizations that are dedicated to collecting those stories in particular. Maybe you can write op-eds offering your experiences as a way to provide deeper context into stories that are happening now. Maybe you want to write a series of letters to the younger generations of your family. Maybe, if you have photos, there are ways to incorporate those.

Of course, you can’t guarantee how any of these might land, either, but if you’d take satisfaction from the process…well, I think that’s the main thing. Maybe, actually, the only thing.

Good luck with your project.

* I’m giving a shout-out to this podcast in particular because here’s how Julia Louis-Dreyfus explains the idea behind it in the first episode:

I was really struck by the fact that we just don’t hear enough about the lives of older women. You know what I mean? When women get older, they become less visible, less heard, less seen in a way that really it just doesn’t happen with men. We are ignoring the wisdom of, like, more than half the population. It is just stunning to me that women—old women and, by the way, not even so old women—are so easily dismissed and made invisible by our culture. You know—f**k that bullshit. I want to hear from older women.

And I think this is part of my answer to your letter, too. We need as many stories from older women as we can get.

Today’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Book Pipeline. Editors reviewing unpublished fiction and nonfiction through the Book Pipeline Workshop. “Recommend” submissions are considered for circulation to lit agents and publishers. Learn more and submit—and use code Jane50 for an exclusive $50 off a Pitch Package review! (Ends Oct. 31.)

September 26, 2023

Media Training for Authors: 6 Ways to Become a Go-To Expert

Photo by Sam McGhee on Unsplash

Photo by Sam McGhee on UnsplashToday’s post is by author and media trainer Paula Rizzo.

Authors will often say, “I’ll do media when my book comes out!” And I always inform them—it’s too late. In fact, you need to start before you even have a book.

I know, I know—but it’s true! Don’t panic.

I started a blog at ListProducer.com about list making, how to be more organized and less stressed in April 2011. I knew if anyone was going to take me seriously as an expert, I needed to be seen in the media. So I pursued media attention. Lots.

Why is doing media so important? Well, nothing gives an author or her book a boost like a media mention. It might not always equal book sales, but being recognized in the media is one of the best ways to get people excited about you and your book. And if you’re earlier in the process, it helps to sell your book proposal too. My publisher was impressed that I could get the media’s attention when they signed with me.

I know this from both sides. I spent nearly two decades booking authors for TV appearances. In my career as a journalist and an Emmy Award–winning senior television producer, I noticed something about the authors and experts who made the cut versus the ones who never made it past the pitch. The authors who are chosen for segments already had media under their belts—usually. Television moves quickly and producers can’t be bothered testing out people who are terrified to be on camera. Now as a media trainer I’m able to help my clients get a “yes” from the media.

Now, you might be wondering—how can I begin doing media appearances for the very first time and get the ball rolling?

1. Start before you’re ready.In fact, it’s imperative for you to start before you feel fully “ready.” You’ll probably never feel totally ready, and that’s okay. Once you get started, each experience will add to your confidence. And by the time you’re doing media for your book, you’ll feel right at home. You should also be creating your own content and talking about topics that you care about even if the media doesn’t come knocking right away.

2. Get your feet wet.Don’t be a snob! No opportunity is too small—and in fact, it can actually be better to start with smaller audiences and build up from there. Very few people start with top-tier media. Choose some local outlets to pitch and practice with. Every media experience gives you more name recognition and will move you towards your next gig.

Media begets media. Once you do one interview, you can use that to pitch others. And where do you think producers and editors are looking for experts? Other media! But you have to be there to be found.

3. Get used to rejection.Rejection is more than okay. It’s good, because it means you’re putting yourself out there. Pitching yourself as an author and expert means you’ll deal with a lot of rejection, and it’s something you have to get used to. Try not to get discouraged or take it personally. It just means you weren’t the right fit or it wasn’t the right time. Make sure you follow up—sometimes that’s even more important than the first attempt.

4. Make friends with reporters and producers.As you begin to pitch yourself and start doing media, always maintain friendly relationships with reporters and producers. Whether you book the segment or not, keep in touch so that they remember you for next time. You never know when they’ll need someone with exactly your perspective or expertise!

Then make sure to say yes when they do ask you for a comment. It breaks my heart when authors say they passed on a media interview because they didn’t feel ready. This is why I’m encouraging you to start sooner rather than later: so this doesn’t happen to you! In a producer’s eyes, the expert who doesn’t say yes isn’t serious and they move on to the next—and may never call you again.

5. Remember, TV still matters.Of all the things I’ve done in my career, people were most excited when they saw me appear on television giving an interview. I’ve won an Emmy Award as a television news producer, published two books (Listful Thinking and Listful Living), given keynote speeches and more. But not one of those accomplishments garnered me the social cache and excitement of being featured on television. Does it sell books? I have no idea. Probably not. But it boosted my visibility and contributed to my credibility. (In my experience, podcasts sell books more than other forms of media. Do lots of them! They are great practice too for bigger opportunities.)

6. Get up to speed on what to do before, during, and after a media appearance.Practice what you’re going to say. You don’t want to sound stiff and rehearsed, but you should have an idea of what you’re going to talk about. The more you practice, the easier it’ll be to speak articulately and naturally. Watch episodes of the show you’re appearing on or check out the journalist’s previous work to get a better sense of the questions you might be asked. Sometimes they will share this information in advance, but not always. Practice out loud for television interviews. Trust me on this. You’ll feel strange, but it’s really important that you rehearse how certain words will sound when you say them.

I created a list of the top 10 media questions every author needs to be able to answer in an interview, at a book event or anywhere else! You can grab it here.

Use the Accordion Method. This is a concept I developed for my media-training clients. This means having a short, medium, and long answer to the questions you’re preparing for. That way, you can easily pick how you want to respond based on the amount of time you have. Speaking in soundbites is an essential skill for any author whether you’re doing media, pitching your book, speaking at book events or on stages. It’s something I teach in depth in my online training course Media-Ready Author.

Planning is key. Plan out what you’re going to wear, how you’ll do your makeup and what technology you’ll use if you’re appearing via video call. That way, none of the logistical elements will stress you out on the day of.

Promote it. Tell everyone that it’s happening! You want to create buzz around your media opportunities.

Be in the moment. You want to respond to what your interviewers are actually asking, even if their framing is a little different than what you practiced. You should have talking points and know the messages you want to get across but make sure you’re truly listening and go with the flow. All that practice will set you up to be able to improvise when the situation calls for it.

Always assume you’re on camera. You never want to be caught off guard making a funny face or fixing your hair on camera. Once you’re connected on Zoom or in the studio with the interviewer, assume they could broadcast at all times.

Make eye contact. As a producer, I learned this skill early on, and it’s something I do to this day whenever I speak to someone. When you’re in person with someone, pick one eye and stare into it the whole time you’re having a conversation. That way you don’t have to decide where to look and feel awkward. Just pick one eye and stick with it! If you’re on a video call, look into the camera’s lens, not at yourself on the screen.

Afterward, say thank you! Don’t forget your manners. It’s always polite to thank the reporter or producer in the moment as well as in a follow-up email. Connect with them on LinkedIn and follow them on social media. Get to know what they cover and also what they like personally. This helps to build and maintain relationships that can be fruitful down the line.

I can count on one hand the number of thank-you notes I received during my nearly 20 years as a television producer. Sending one will help you stand out and be remembered.

Repurpose all the content. This content isn’t just for the producer or reporter to use—it’s for you! Make the most of the content by sharing it with your audience online and repurposing it for blogs and social media.

Stay in touch and get asked back. Keep an open line of communication with reporters and producers who you’ve worked with. They already know you, so they’re more likely to work with you again. Leverage those relationships—if they enjoyed working with you once, it makes their job easier to book you again because they know you’ll do well.

When you cultivate these relationships before you have a book, it will be much easier for you to get the media’s attention when your book does come out. The trick is to start right now.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1885 followers