Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 38

February 14, 2024

Hybrid Publishers and Paid Publishing Services: Red Flags to Watch For

Photo by C. G. on Unsplash

Photo by C. G. on UnsplashToday’s post is by author Joel Pitney, founder of Launch My Book.

“It takes them weeks to get back to me.”

“I have no idea where my book is published.”

“Royalties? What royalties? I haven’t seen a penny come my way and it’s been over a year.”

“The cover is fine, I guess. I didn’t have much control over the final product.”

“I wish I had talked to you months ago.”

These are just a few of the comments I’ve heard from authors sharing their experiences with the hybrid publishing companies they’ve chosen to work with. Sadly, I’ve noticed that these conversations have become more frequent in recent years. So if you’re an author starting out on your publishing journey, it’s important to know what to look out for.

In this article, I draw upon the experiences of the many authors I’ve worked with to present common red flags to watch out for.

It’s a confusing landscape for everyone.Alongside the explosion in self-publishing has come a proliferation of companies that help authors publish. These range from freelancers who do the necessary work of self-publishing (cover design, interior layout, and more) to hybrid publishers who publish your book under their name for pay. And like other explosive industries throughout history (think gold rush or the dot-com boom), some of these companies are extremely opportunistic, offering aspiring authors the rainbow (bestsellers, a living wage, overnight success) and delivering something far less.

Unfortunately, many authors find they’ve paid a bunch of money to a company who made them big promises, and whose delivery is far worse than expected.

It’s understandable that many authors end up being scammed in this way. Book publishing is confusing, especially if you have little to no experience with it. When you google something like “find publishing help” or “self-publishing company,” you’re likely to get hundreds of results from a wide variety of companies and experts telling you which way to go. You’ll then get a whole slew of subsequent emails and social media ads perfectly targeted to you. Many of these companies are REALLY good at marketing their services to you. They know what motivates authors and what frustrates them; they make offers that promise to address those core needs.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not against hybrid publishing, or other professional companies that help with self-publishing. I think this is a wonderful option for many people, and there are plenty of solid companies out there. What I am against is the dishonesty and and expectation-inflation I’ve encountered through the experiences of my clients in recent years.

Every time I hear another bad publishing story, I go check out the company for myself. I’ve started to notice common patterns in how such companies present themselves, and I’ve put together a list of tips to help you avoid the bad actors. I’d love to hear your experiences, thoughts, or disagreements in the comments section!

Avoid companies that use hype-filled language.The number one warning sign to look out for is hyperbolic language and big promises on the company’s website or in their advertisements. I’m sure you’re familiar with this kind of thing. Many services use phrases like “bestseller,” “sell your first 10k copies,” or “achieve your dream of being an independent author” to reel you in. One site I visited added the following language to the top of their contact form: “Talk to a bestseller consultant today.” They want to sell you on the dramatic success of your book.

I’m not a pessimistic person, and I’m not against being ambitious about sales and shooting for bestsellers. But it’s important to acknowledge the reality that it’s very rare for self-published books, especially by first-time authors, to achieve the level of success that many companies imply. Hitting a bestseller list (beyond the easily hackable Amazon sub-category bestsellers) is a herculean task. And I believe it should be. So is achieving profitability on your first book.

Like any business, it takes time to build a successful platform for your book. You’ve got to invest time, money, and effort in your platform, experiment with many marketing techniques, and engage and grow your audience over time. It simply doesn’t happen overnight. And yet many of these companies prey upon the ill-informed expectation that it could. So if you see big promises to deliver amazing, super-awesome results in record time, be very wary.

Don’t be fooled by the publisher’s seeming selectivity.Some companies present the air of selectivity, to make the authors they “choose” to publish feel special. By this, I mean that they use a gimmick: authors are required to submit their manuscript for review, making it seem as if your book needs to meet a certain standard threshold. They tell you that they’ll review it and determine whether or not they want to publish it. In this way, they make themselves appear to be more like a traditional publisher.

But the truth of the matter is that few companies are actually as selective as they make themselves out to be. They will generally accept anyone who’s willing to pay for their services. There’s nothing wrong with that! But they should be honest about it.

A similar dynamic is often at play with hybrid publishers associated with traditional publishers. They often tell prospective clients that the “main” publisher they’re associated with will choose the bestselling self-published titles each year and give them traditional deals. While this may be true, it’s oversold; a tiny number ever receive such an offer.

If you see a live chat, run away!Many companies have found the right balance between price and volume to maximize their profits. I’ve certainly done a lot of that analysis with my own business. But scaling up can come at the expense of quality and customer service. Large publishing service companies churn out hundreds of books a year and often find the cheapest workforce to deliver on their services.

This leads to poor design (we’ve all seen plenty of covers, for example, that clearly look self-published) and poor customer service. Account managers are assigned too many authors for them to handle, and have poor response times, overlook important details, and aren’t in touch with the unique needs of their clients. And this leads to the kinds of negative experiences I hear about.

So what do live chats have to do with this? Well, if a company has a live chat option on their website (probably delivered by a bot instead of a real person), they’ve likely scaled to a point that their delivery is going to suffer from low quality and poor customer service. These are all signs that a company is too big to provide the kind of service you deserve. It’s not a 1-to-1 equation, of course, and there are probably some good companies out there who offer live chat. But having that kind of functionality, or other indications of scale, is definitely an indication that you should be careful.

Do your homework. Ask questions about what kind of service you can expect. Ask how many books they publish each year and how many other clients your account manager will be working with. And, of course, check their work, which we’ll cover later.

Bargain prices aren’t in your favor.I’m really sorry to say this, but when it comes to book publishing, you really do get what you pay for. You don’t have to pay premium prices, but in my experience, if you’re on the discount end of the spectrum, the quality of the finished product will also look cheap, and your customer service will likely be poor. So when you’re assessing a company (or freelancer), beware of low prices. Additionally, avoid companies offering limited time offers and 50% off discounts as if you were at a used furniture store.

Take it from someone who publishes books for a living: there’s a reason these companies are offering their services for cheap. Their delivery is going to be second- or third-rate. It’s just not possible to do high quality work at discounted prices in this industry.

So what should you expect to pay? I’ve done a lot of research on this topic, surveying different company websites and comparing prices. At the high end, you’ll likely pay $10,000–$15,000 for the basic services you need to get your book published (copy editing, cover design, interior formatting, and distribution setup). That doesn’t include high-level editing, book marketing or publicity, or paying for a print run, which some services recommend or sell.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, some discount companies charge in the realm of $1,000 to $2,500 to do the same work. And for those prices, it’s likely the work will be low quality.

Don’t get me wrong, paying a lot doesn’t guarantee better quality. Middle and higher tier companies can also deliver low quality work with poor customer service—you’ll just pay more for it. For example, in the past year alone, I’ve worked with two different authors who originally published their books with one of the most popular self-publishing companies (I don’t want to mention their name). The company charges upper to middle tier prices, but their work was of such poor quality and their customer services so unfriendly that these authors decided to break their contracts and re-publish their books, at a high expense to them. Sadly, this kind of experience is more common than you’d expect.

So how do you protect yourself from these kinds of experiences? Check their work.

Beware of shoddy work.One of the easiest ways to determine the quality of a book publishing company is to check out the books they’ve published in the past. This may seem simple on the surface. For example, many companies will simply list some of their clients right on the website. But I suggest digging a little deeper to get the most accurate picture possible. Here are a few tips.

What do their covers look like?This is the most obvious sign of a company’s quality. The vast majority of publishing companies will include covers of books they have published right on their website, and these will give you a quick and easy sense of the quality of work they do. You can also dig deeper than the covers they’re showing you on the site. Go search on Amazon—enter the publisher name into the search window to get a broader list of the titles they’ve published.

How do you perceive quality in cover design? Even to the untrained eye, a good, professional cover should stand out from one that is unprofessional and sloppy. To get a benchmark, take a look at covers of similar genres from big name traditional publishers. One thing I tend to focus on is the relationship between the background images and text on a cover. Pro designers integrate these elements elegantly, whereas lower end cover designs tend to have a lot of awkward contrast between the two.

Check out the book interiorsInterior layout design is as much of an art as cover design. The interior layout is essentially how the book looks on the page, including fonts, headers, page numbers, spacing, and more. And like other design elements, there’s a spectrum of quality among publishers. The best way to review the work of a publisher is to look up their titles on Amazon and use the “Look Inside” function on the book detail page. You can then scroll through a sample of the interior and get a sense of the quality of the work they do.

Did they actually publish the work they are listing?The other day I took a call from an author who wanted to know what I thought of a particular hybrid publishing company that he was considering working. I went to their website and saw all the red flags listed in this article, so my hackles were up. When I started scrolling through the books they claimed to have published, something caught my eye—a very famous book, which I knew for a fact had been published by one of the big traditional publishers. I did a little searching to see if I could find any connection between this company and the book, and there was nothing.

Unfortunately, this is more common than you’d expect. I don’t know how they get away with it, but many companies list books they did not work on. So if something seems a little too good to be true, do some digging to see if their claims can be backed up.

What do their Amazon listings look like?One of the often overlooked signals of a book’s quality is how it’s represented on Amazon. The publishing company, whether traditional or hybrid, is generally the one responsible for setting up a title on Amazon and will have control over the appearance of its detail page. And you can tell a lot from how good a job they do. Here are a few things to watch out for on the page:

The descriptive copy: Is it compelling? Are there formatting errors?Is the “Search Inside” functionality set up for the book?How many categories is the book listed in? Good publishers will make sure the book is listed in at least three.Have they added professional endorsements and testimonials to the listing?Have they set up an Amazon Author Central profile for the author?Does the company’s website appear professional and elegant?This is a big one. It’s my conviction that if a company can’t put together a beautiful website, they definitely won’t do a good job on producing your book. A website reflects a company’s aesthetic sense, attention to detail, and level of visual care, and all three of these elements are crucial to producing a high-quality book. So if the website makes a bad impression, pay attention. There’s likely a strong correlation there.

Your personal calculusAt the end of the day, everyone is going to make their own decisions about which company to hire. And given the wide variety of options available, there’s definitely no one-size-fits-all rule for choosing a company to publish your book. Each one will have strengths and weaknesses, and you’ll need to decide which of those strengths are most important to you. You might even, for example, decide that quality is less important to you than money and choose a lower tier company, and that’s okay.

I just want to make sure that every author is as informed as possible when making such a significant decision as choosing a publishing partner. Whichever company you choose to work with should sincerely value the hard work you put into writing your book, so that your final product is one you can be truly proud of.

I’d love to hear about your experiences in the comments here. Have you worked with a publishing service company or hybrid publisher? And how did it go?

February 13, 2024

Writing Rules That Beg to Be Broken

Photo by Alice Dietrich on Unsplash

Photo by Alice Dietrich on UnsplashToday’s post is excerpted from Ten Easy Steps to Becoming a Writer by Randall Silvis.

I despise rules. Always have. Rules are for accountants and architects, assembly line workers and neurosurgeons. In order to be successful in those professions, there are procedures that must always be followed, variations that must never be employed. The word creative, however, as in the phrase creative writing, demands, at the very least, an imaginative interpretation of the rules.

Thanks to a degree of success over the years, I am asked again and again to lay out a prescription of rules for aspiring writers. This is one request I will not honor. No writer living or dead has discovered a universally foolproof method of churning out successful fiction, and none ever will. How can you discover what does not exist? If success as a writer depended upon nothing but following a list of rules, why are there so many aspiring writers who can’t get published?

The following are some of the so-called rules of writing fiction that I take a special delight in breaking. Creative writing is about possibilities, not about restrictions and limitations.

Never correct or rewrite until the whole thing is down.In 1962, in a letter to a young writer, John Steinbeck added six tips for writing well. The above was one of those tips. Its error lies again, as all rules do, with its use of the absolute never. I frequently will not, because I cannot, begin a story or novel until I have crafted the perfect first paragraph. Of course there is no such thing as a perfect sentence, but the temporary confidence instilled by thinking that I have crafted one is what allows me to tackle a project that will consume my waking and sleeping hours for the next year or more. Stopping now and then to polish a faulty phrase or image is like taking another hit of confidence.

Five or six hits every morning keep me flying through the hours. But if I cannot fix a weakness within a minute or two, I will not allow my momentum to stall out with fretting and hand-wringing. Placing parentheses around the offending phrase, or highlighting the entire scene, will call my attention to it during the first rewrite.

I do not believe, as some practitioners apparently do, that a morning’s work is like a fast-moving stream through which one must dare not stop paddling, not even for a moment. Go ahead and stop if you want to. Pull ashore. Have lunch. Creep up as close as you can to that egret in the tree. Take a nap if you feel like it. In short, do whatever works for you. The imagination is resilient and flexible, and your routine should be too. But only if that works for you. I am most productive when I adhere, albeit loosely, to the discipline of beginning the morning with a bit of meditation, followed by four to six hours at my desk, followed by a good workout or hike. That’s my routine. It doesn’t have to be yours.

Write what you know.In the days of Thoreau and earlier, when it was necessary to walk several miles to consult with someone more knowledgeable than you, Ernest Hemingway’s write what you know might have been sound advice. Hemingway also said that every writer needs a friend in every profession, someone whose expertise can be accessed—a statement that appears to contradict the earlier statement.

In order to do my research back in the 1970s and 80s, I had to visit a small-town library every week to order another load of books on interlibrary loan, which made the librarian my best friend. Today, a writer’s best friend is the internet.

I feel certain that Hemingway’s write what you know admonition was not intended to be an absolute. A clearer rendition of that advice would be to write what you know after you’ve done a ton of research and before you forget it all. And always remember that you are writing fiction. Fiction is stuff you make up. You can do that too. You can make stuff up.

Back at the turn of the millennium, I signed a contract, based on a single opening scene, to write two historical mysteries featuring Edgar Allan Poe for Thomas Dunne Books. I had never before written a historical novel and was not confident I could create a convincing New York City of 1840. In one scene it was necessary for me to get Poe across the East River in short order so that he could hotfoot it to Manhattan. I spent weeks trying to find a bridge he could cross or a ferry that would convey him in the allotted time. No such luck. I was stuck. I moaned about this impasse to a friend of mine who was also a writer, and he said, “It’s fiction, Silvis. Make up a bridge.”

Frequently it is the not knowing that brings a story alive, the writer’s desire to know what he does not, which then leads to the character’s discovery of what she did not know, and then the reader’s delight in participating in that discovery.

Show, don’t tell.A favorite admonition among writing teachers all over the world. This admonition is only half false. The true part is that good fiction is built on dramatic scenes comprised of action, dialogue, description, and conflict—i.e. showing through visual and other sensory details and strong, active verbs. But a certain amount of telling is necessary too. Summary and exposition hold the scenes together. Telling bridges the time gap between scenes and between relevant beats. A little bit of telling, even if it’s something as simple as “Two weeks later,” opens nearly every new scene and every chapter.

So, once again, the problem with the rule is not that it is wholly false but that it is stated too rigidly. Summarization complements dramatization in every novel. In some, it shoulders the narrative load. Sebastian Barry’s Days Without End, for example, is a brilliant novel that is almost wholly told rather than shown.

In general, the more “literary” a novel is, the more it relies on reflection, speculation, and summaries of events. That is why a literary novel is so hard to adapt for the screen; so much of the momentum of the story is interior, taking place only in the characters’ heads.

Screenwriter Charlie Kaufman ran into this very problem when attempting to adapt Susan Orlean’s nonfiction The Orchid Thief for film. The problem was so infuriating that he finally seized upon introducing himself into the story as twins, one of whom was being driven mad by attempting to write the adaptation without sacrificing the book’s artistic integrity, and the other as a hack only too ready to pander to Hollywood’s lack of artistic integrity by changing the story willy-nilly. “Show, don’t tell” is fine advice if you are aiming for a quick sale of movie rights, or if you are fifteen years old and learning how to write in scenes, but the proper amendment of the phrase for the rest of us should be “show when you can, but tell whenever showing isn’t necessary.”

The writing life is mostly a lonely, miserable life.A common refrain among self-pitying writers. This concept is a form of the romantic allure of the suffering artist. Trust me; there is nothing romantic about suffering. If you haven’t done much suffering yet, you will after you have children, and then you will understand how unromantic it is to be a miserable wretch who can’t stop worrying. In David Foster Wallace’s essay “The Nature of the Fun,” he addresses the reader as you and delineates for her the psyche-strangling process she will undergo from aspiring writer to acclaimed author, except at the beginning. “In the beginning,” he writes, “when you first start out trying to write fiction, the whole endeavor’s about fun. You don’t expect anybody else to read it. You’re writing almost wholly to get yourself off.”

I disagree. I expected all of my early stories to be published. (Only a few were.) Nearly every student I taught over a lifetime of teaching fully expected their early work to be published. So when Wallace says you don’t expect anybody else to read it, he’s speaking for himself.

Then comes success, Wallace says. What he should have said is, If you work very hard and are very lucky and talented, then comes success, depending on how you define success, because in most cases it is a very minor success resulting in few readers and little money.

After which, he says, “Things start to get complicated and confusing, not to mention scary. Now you feel like you’re writing for other people,” and the enjoyment you once found in writing “is offset by a terrible fear of rejection,” until you soon discover that “90 percent of the stuff you’re writing is motivated and informed by an overwhelming need to be liked. This results in shitty fiction.”

Eventually, he says, you might somehow shovel your way back to the fun of writing and discover that writing fiction is “a weird way to countenance yourself and to tell the truth instead of being a way to escape yourself or present yourself in a way you figure you will be maximally likable. This process is complicated and confusing and scary, and also hard work, but it turns out to be the best fun there is.”

Yeah, well, Mr. Wallace had himself some issues. It is a bleak journey he chronicles, no less so because it was one he was unable to see through to completion, which eventually led to his suicide. But it is not, despite the second-person address he employed, the journey you must take. It was his journey, the one he plotted for himself, but one tragically tainted by his need to be liked. There is absolutely no reason why any of that bleakness has to be part of your journey.

I have never thought of the writing life as fun or scary or complicated or as a way to be liked. It is sometimes easy, sometimes magical, sometimes maddening, demanding, and exhausting, yet frequently very satisfying. I do it principally for the magic and the mystery and the sense of satisfaction it can elicit. I love words and I love stories, and I take great pleasure from being able to indulge myself in those pleasures every single day. Storytelling is not a way to work out who I am or why I exist; being a father answered most of those questions for me.

Storytelling allows me to share my passion with others and to get paid for it.

David Foster Wallace was a fine but very troubled writer who confused what he was with what he did. This is a common affliction. Do not fall prey to it, because it usually won’t end pretty. If you don’t believe me, have a séance and ask Hemingway, Virginia Wolfe, Hunter Thompson, Sylvia Plath, and John Kennedy Toole.

No matter how authoritative and confident a writer sounds, and no matter how much you admire that writer’s work, he or she is capable of detailing only his or her truth, derived as it was from his or her own idiosyncratic journey. Your journey might be similar or it might be vastly different; it will never be exactly the same as any other writer’s journey.

Yet many writers, in an attempt to be helpful, create lists of rules for aspiring writers. The honest writers speak only in generalities: Write every day. Read voraciously. Write what you want to read. The less honest, or merely less humble, get specific and adamantine: Avoid all adverbs. Never start with the weather. Write short sentences. The more specific a writer’s rule, the less trustworthy it is, and the sooner you should find the nearest exit.

Amazon

AmazonBy all means go ahead and read the rules, if you wish. Give them a try. And if one of them works for you, use it until it stops working, then dump it in the trash heap with all the other useless rules that have been crammed down your throat since your first hour in daycare. Writing is creative, so don’t look to prescriptions or those who preach them. Sit down and create.

Stick with it, and you will figure out the rest along the way. That has always been and will always be the only true way to learn.

My favorite piece of writing advice comes from Margaret Atwood: Nobody is making you do this: you chose it, so don’t whine. That is the only rule you will ever need to post over your desk: Stop whining and write!

February 8, 2024

Author Platform Is Not a Requirement to Sell Your Novel or Children’s Book

Recently an article was published at Vox titled “Everyone’s a sellout now.” The subtitle: “So you want to be an artist. Do you have to start a TikTok?”

The dour conclusion, probably the writer’s predetermined conclusion when she began her research: more or less.

This article makes the classic mistake of conflating all kinds of artists and creative industries and painting them all with the same brush. But specifically, for writers and book publishing, it spreads so many myths and misconceptions about the business of authorship that I’ll be undoing the damage for years. (My inbox last week: Did you see this article!) However, I hope this post helps reduce the length of that battle. So let’s get straight to it.

Agents and big publishers seek authors with platform for adult nonfiction work.Vox: With any book, but especially nonfiction ones, publishers want a guarantee that a writer comes with a built-in audience of people who already read and support their work…

If a debut novelist or debut children’s author seeks a book deal with a big New York publisher, then agents and editors make their decision based on the story premise, the manuscript, and/or whether the project fits with their theory of what sells in today’s market. That theory may be driven by pop culture, by what else is selling well among their clients or at their publishing house, by trends on TikTok—you get the idea.

If you’re a debut novelist with a platform, great! But it’s not going to make up for a lackluster story or premise that’s unappealing to today’s readers. The agent or publisher has to have genuine enthusiasm for the story or writing itself. They tend to trust their instincts on story quality or story marketability, and if they don’t love it, they’ll have trouble convincing anyone else of the same. The general hope is that word of mouth and consistent recommendations by readers and influencers will fuel the book’s success—not the debut author’s platform/following. Most bestsellers occur because of readers saying to their friends and family: you must read this.

Let me be absolutely clear: Agents and publishers don’t read a novel or children’s manuscript, fall in love with it and/or think it will sell in today’s market, then check to see if it’s safe to represent or acquire based on the author’s online following. (However, I have seen such a thing happen with nonfiction. I’ve also seen it happen when an author has a poor sales track record.)

Side note: I’m adding children’s authors into the mix here because, I hope for obvious reasons, it can be problematic to expect children’s writers to build an online following among children (their readers), although some children’s writers do have strong connections in the children’s community—with librarians, educators, teachers, and so on. Children’s books often must meet considerable requirements related to format, word count, education level, curriculum expectations or standards, etc—and platform is usually low on the list of concerns even for nonfiction.

Having an online presence or following is mostly a bonus for the agent or publisher if you’re an unpublished or untested fiction writer. Think it through: if you’re an unpublished novelist who’s building a following, why are others following you exactly? It’s not for your novel, because that’s not published yet. Is it for your short fiction in literary journals? Congratulations! You have a rarefied audience of people who actually read short fiction in literary journals.

Certainly publishing credentials that impress or show you’ve been selected/vetted or validated can help you get the consideration you deserve, or make you more visible to agents or decision makers at publishing houses. And social media will do wonders for building relationships with others in the writing and publishing community. To the extent that being on social media helps you be seen by gatekeepers, sure—this is part of platform, and it can lower some barriers and lead to more connections that help you get published. But we’re not talking about a following of existing readers on social media. We’re talking about relationships and visibility to specific, influential people. You can be visible to such people with a tiny following.

None of this is to say social media doesn’t sell books—it can and it does—but it’s rarely in the way that any writer thinks. It’s not going to sell a novel that readers aren’t motivated to go and tell all their friends about, whether that’s online or offline. And that’s the quality that agents/publishers are looking for when they receive your submission. Authors will find it challenging to support word of mouth on social without having readers’ own enthusiasm for their work present at the same time.

Now, if you’re a TikTok sensation or a self-published author who’s driving tons of views and conversation about your work, that’s when agents and editors approach you. You don’t even have to query. But if your following isn’t enough to proactively attract agent or publisher attention to your door, then I don’t think it plays a meaningful role when you’re going on submission or submitting a query. Does it hurt? No.

In the debut novel deal announcements at Publishers Marketplace, it’s rare to see any mention of platform. But occasionally writing/publishing credentials or occupations are mentioned. Here are some descriptors in early 2024, if any are given at all—the majority have no credentials listed.

Software engineer and contributor to the Drunken Canal and HobartPushcart Prize winningElizabeth George grantee and Warren Wilson MFA graduateManaging editor of fiction for Foglifter Journal and creative writing teacher2023 Reese’s Book Club LitUp FellowYaddo and Macdowell fellowPreviously published in Slate and The Bellevue Literary Review and heard on NPRLambda Literary fellowBook criticRona Jaffe Scholar and Oregon Literary FellowThese credentials mainly testify to the quality of existing writing or involvement in the writing community. This is a critical part of platform that doesn’t require social media activity or self-promotion. Unfortunately, the writer at Vox seems fairly obsessed with TikTok, which is understandable—it’s driving book sales for the likes of Colleen Hoover. But that doesn’t mean debut novelists must now launch themselves into a short-form video career. And it doesn’t mean that for nonfiction authors either.

You can still get a book deal for nonfiction without a platform.Platform is most often a concern for literary agents who are looking for the easiest path to a big deal with one of the conglomerate New York publishers. Telling an author “you don’t have a platform” is one of the easiest and most non-offensive ways to get rid of a project they don’t want to represent. But reasons for rejection tend to be multi-faceted and writers rarely receive the real reasons behind it—especially not “your trauma memoir is derivative and boring” or “your writing lacks anything fresh or exciting.”

Small and independent publishers—who can be equivalent to or better than the biggest New York houses—accept books all the time where the author does not have a platform. (Here’s how to research them.) Authors can approach such publishers directly without an agent. Here’s how to evaluate publishers on your own without the help of an agent.

You can get a book deal for memoir without a platform.Memoir gets acquired all the time without the author having a platform. At the same time, the number-one reason memoir gets rejected is because the author does not have a platform. There’s a lot of memoir being submitted these days, and very little of it is deserving of a nationwide audience. Sometimes, the agent is outright lying about why they’re rejecting the project; it’s easier to say “no platform” than “bad writing” or “boring story” or “won’t sell.” Other times, the agent or publisher is only interested in memoirs by authors with platforms. So how can you tell which is which? One clue is what the agent or publisher asks authors to submit. If they want a proposal, they’re definitely interested in your platform and probably sell memoir based on platform (at least in part). If they want a query and the full manuscript, they probably acquire memoir on the basis of the story and the quality of the writing. But in the end, they may still reject on the basis of platform because they think that’s the kinder way out. Too often, it’s an unkind rejection, because authors get misled into trying to build platform when that’s not really the problem.

In 2022, I researched memoir book deals and found that about 25% were with authors who did not have any identifiable platform.

OK, moving on to the next problematic claim in the Vox article.

There has been no time in publishing history when writers were unaffected by the market—or didn’t have to think about it.

Vox: We like to think of it as the work of singular geniuses whose motivations are purely creative and untainted by the market — this, despite the fact that music, publishing, and film have always been for-profit industries where formulaic, churned-out work is what often sells best. These days, the jig is up.

… Even when corporations did enter the picture, artists working with publishing houses or record companies, for example, had little contact with the business side of things.

In the literary community especially, there’s a persistent and dangerous myth of the starving artist, and the belief that “real art” doesn’t earn money or that “real artists” don’t consider commerce. In fact, art and business can inform each other, and successful writers throughout history have proven themselves savvy at making their art pay.

Mark Twain’s work was sold direct to reader by door-to-door salesmen, which was not considered high status at the time. (Respectable people sold their book in bookstores.) But it was direct to reader that led to the best success and sales for Twain. Little Women was borne out of financial desperation by Louisa May Alcott, who wrote it on assignment, for the market. George Eliot, the great moral novelist, left the publisher she had been loyal to for many years, to work with a publisher offering a higher advance. Etc. The examples are legion. What’s insufferable are the scolds who continually try to make artists and writers feel lesser than if they consider the market or avidly market and promote. T.S. Eliot was such a scold; he called poet Amy Lowell a demon saleswoman of poetry.

I believe there is a productive tension to be found between art and commerce. Richard Nash, who has written eloquently about the business of literature, once told me, “Business and marketing are about understanding networks and patterns of influence and behavior. Writers can handle that.” Meaning: This is not some catastrophe that writers need to be rescued from. See Make Art Make Money by Elizabeth Stevens, which is essentially a biography of Jim Henson, showing how he played art and commerce off each other to magnificent success. (She also wrote about Borges and his day job, and why working a day job was good for his creativity.)

I’m on Andy Warhol’s side when he said, “Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.”

Next:

Vox: Self-promotion sucks. It is actually very boring and not that fun to produce TikTok videos or to learn email marketing for this purpose. Hardly anyone wants to “build a platform;” we want to just have one.

Yes, it does suck if you define self-promotion or platform building as selling out or being on TikTok/social media. This is a simplistic and follow-the-trends perspective that writers get sucked into all the time, to their detriment. Tara McMullin has already written a terrific response about self-promotion that everyone should go and read: Sorry (Not Sorry): Self-Promotion Doesn’t Work.

In this post, I’d like to expand on the idea of platform.

Platform should not be conflated with “social media following” or self-promotion.Platform building is an unwieldy topic to address for authors; no two platforms are alike and building an effective one depends on your resources, strengths, connections. What I can say is that platform should not be equated to “social media following” or self-promotion. It’s just as much about showing that you have connections and belong to networks that can help spread the word about what you do. You might have a sufficient enough platform already to land a book deal, especially if you’re regularly publishing in outlets that your target audience reads. For further inspiration, read this post.

Fortunately, a meaningful and sustainable platform flourishes out of the work itself and is not divorced from what you as an author want to talk about, ordinarily and enthusiastically. However, if you want to sit in a remote garret for the rest of your life and bestow your genius unto the world without ever interacting with a single soul, well, yes—that is going to be quite problematic for your future as a bestselling author.

It’s foolhardy to expect you can just write and publish, and that good things will happen without you playing a proactive role in somehow being visible. And that’s what platform is all about: visibility. You want your work to be seen and most writers want to grow their readership, which typically leads to more earnings or earnings opportunities. Platform is important to the extent that you want or expect to earn a living from your writing and publishing activities. But treating platform as a series of self-promotional tasks, isolated from your own values and strengths, will be a waste of your time and energy.

While platform gives you the power to market effectively, it’s not something you develop by engaging in self-promotional activities. It is not about hard selling, being an extrovert, or pleading “Look at me!” Platform isn’t about who yells the loudest or markets the best. It’s about putting in consistent effort over the course of a career, and making incremental improvements in how you reach readers and extend your network. It’s about making waves that attract other people to you. Ultimately, your platform-building process will become as much a creative exercise as the work you produce.

Author platform has become more important over the years because it is not impressive or meaningful to publish something in the digital era. Many of us now publish and distribute with the click of a button on a daily basis—on social media especially, but also on all kinds of platforms. The difficult work lies in getting attention in an era of “cognitive surplus.” Cognitive surplus is a term coined by author Clay Shirky that refers to the societal phenomenon where we now have free time to pursue all sorts of creative and collaborative activities, including writing. Arianna Huffington once said, “Self-expression is the new form of entertainment,” and author George Packer wrote in 1991, “Writing has become one of the higher forms of recreation in a leisure society.” And even more so now. A writer today is competing against many more would-be writers than even a couple of decades ago.

Still, committed writers succeed in the industry every single day, especially those who can adopt a long-term view and recognize that most careers are launched, not with a single fabulous manuscript, but through a series of small successes that builds the writer’s network and visibility, step by step.

Some people have an easier time building platform than others. If you hold a high-profile position or have a powerful network; if you have friends in high places or are associated with powerful communities; if you have prestigious degrees or posts, then you play the field at an advantage. This is why it’s so easy for celebrities to get book deals. They have built-in platform. That doesn’t always equate to sales, though; plenty of celebrity books have bombed.

I often advise writers: start with your strengths and don’t worry about what you don’t have. Most of us excel in one or two areas of platform-building and leverage that repeatedly to grow our careers. Speaking for myself, I excel at email newsletters and blogging and have used these mediums for my entire freelance career to fuel my business. The hardest and also most exciting thing about any creative life is figuring out your own path. Don’t get tricked into thinking there’s a formula or some platform that you absolutely must use or otherwise you’ll get left behind. It has never been true.

Last but not least:

There is no evidence to suggest publishers are paying authors less than before.Vox: Fewer publishers means heavier competition for well-paying advances, and fewer booksellers thanks to consolidation by Amazon and big box stores means that authors aren’t making what they used to on royalties, despite the fact that book sales are relatively strong. The problem isn’t that people aren’t buying books, it’s that less of the money is going to writers.

There are, of course, author earnings surveys conducted by the Authors Guild and other organizations that try to show that author income is declining, but these reports are seriously problematic and moreover they do not prove that publishers are paying less than before. Consider:

Advances from Penguin Random House (PRH) for the average author (not a top-earning author, which is someone in the top 2%) either stayed the same or increased in the decade after the 2013 merger between Penguin and Random House. This was revealed during the Dept. of Justice antitrust trial against PRH in 2022.During that same trial, PRH CEO Markus Dohle said that PRH in the US committed an “all-time high” of around $650 million in author advances in 2021.In 2021, here’s the CEO of HarperCollins on the publisher’s performance: “Outgoing funds to authors and advances and royalties is continuing to grow, growing faster than revenues.”If the sizes of book deals were declining, Publishers Marketplace deal reports would likely reflect that. No alarm has been raised.Do publishers have unfavorable terms for authors? Of course they do. Ebook royalty payments are too low and it can be impossible for authors to retain ebook or audiobook rights when working with big houses, just to name a couple areas of frustration. But to say publishers are paying less than before would really require advances or royalty rates to be declining, and I have not seen evidence of that. (Anecdotal evidence from a single author does not count; I’m talking about actual industry data.)

I did have the good fortune to look at the granular data collected by the Authors Guild from its latest author income survey. Authors most likely to report their income decreasing over the last five years? Traditionally published authors and those age 65 and up, which isn’t all that surprising if they’re producing fewer works or coasting on backlist. And who is most likely to report their income increasing? Authors publishing serializations and authors 25–44 years old. Overall, self-published authors were slightly more likely to report increased rather than decreased earnings; they were also far more likely to have published a book in the last year.

And this points to a very important dynamic for every author’s income and whether you can make a living from book sales alone: It matters how much you write and publish, not least what category or genre you’re publishing into. It does not matter how much you use TikTok. Publishers and literary agents know this, even if they pretend otherwise to conveniently reject you and your work.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to receive fact-based, researched information about the book publishing industry—not anecdotal evidence or opinions to make you feel hopeless—consider subscribing to my paid newsletter, The Hot Sheet.

February 7, 2024

Why You Need a Press Release in the Digital Age

Photo by Louis Hansel on Unsplash

Photo by Louis Hansel on UnsplashToday’s guest post is by public relations expert Claire McKinney. It serves as an update to her 2017 post, The Difference Between a Pitch and a Press Release.

If you’re wondering whether press releases are still relevant or important, I’m here to convince you that they are.

Why send out a press release?Media relations departments from all types of companies—Fortune 500 to startups—use press releases to communicate with the media. Why do billion-dollar businesses bother to send them out? Because this is still how you send information to the media. A press release is a tool that is considered “approved” copy for any media organization, online or traditional, to use to discuss an outside entity.

Here is a simple example in the book world: It is very likely that someone will review or feature your book and lift copy straight from your release, which is exactly what you want. If a media outlet decides to run a story about your book with a price or on-sale date that’s inaccurate, you can cite information in the press release and ask to have it corrected. If there are factual errors in coverage tied to your release, you can easily point to the problem and ask for a change.

If you want to include a blurb or endorsement, or include a quote from an expert cited in your nonfiction book, a media outlet understands they can use it. If Michelle Obama endorses your book, wouldn’t you want to have her name and her words in your press release? This is an extreme situation, but it illustrates my point.

However, before you email one sentence to a journalist, there are direct benefits you get from writing your own release.

Why am I writing press materials?You are writing this document because it will help you figure out what your core message is.

The core message is the newsworthy or unique aspect(s) you, your book, and your ideas can offer to a target audience—an audience that is most likely to spread word of mouth and/or purchase your book or services. The core message is ultimately part of your elevator pitch.

Creating a release also forces you to think about your competition and how you are offering something different than what every other mystery, romance, literary fiction, self-help guru, history buff, academic author, etc. is writing about. In an online world, this is incredibly important, because most likely, the first place you are going to make your mark is online and with search engines.

SEO (Search Engine Optimization) for press releasesHaving the release available on your website, your publicist’s website, publisher’s website, etc., will help with you or your book appearing in response to search queries. If you Google your book title, you will probably notice Amazon and other big retailers first; your publisher and your own website can appear later. Having a press release can boost this rank in search queries.

Because the competition for ranking is much more competitive these days, you should do some extra work to enhance your release: include keywords or keyword phrases in the text. You can research which ones to use by using Google to search for terms related to your work such as “books about WWII,” “self-help divorce books,” “books about good habits”, “books about joining the circus,” etc. See what comes up in the search window and consider what phrases or keywords will help your press materials rank better in results.

I don’t think paid services like PR Newswire (that publish and distribute your press release) are worthwhile for most books. If you have an amazing news peg, that could be one reason to invest, but there are thousands of releases posted at such PR websites.

For help with SEO, here are some additional resources:

Google Trends is a free tool that lets you see how high a term is ranked in a specific area. If there is no data available for a search term, it means there aren’t enough people looking for it and it isn’t worth using.Ubersuggest is run by Neil Patel, a marketing guru. Free membership gives you access to a limited number of keyword searches. I thought the free version was fine when I was experimenting.Press release structureThis structure is based on how much interesting or provocative information you can share, without overhyping your message. When you introduce the book in the opening paragraphs, you will need to identify it using the entire title with the subtitl; in parentheses include the publication date, imprint, format, price, and ISBN, like this:

The Great Book: A Novel by Bobbie Bobs (imprint name, publication date, format, ISBN, price).

The first paragraph should tell the reader of the release why your story is compelling and what its relevance is to the audience. You will also want to explain why you wrote the book and how your personal story is connected to it.

The next one or two paragraphs should be a short synopsis of the plot if you are promoting a novel, and a list of the main facts or talking points if you are working on nonfiction. You can also include a more in-depth section on yourself and your story as it relates to the content if you believe it will enhance the core message.

Within the release, you will want to mention the book’s title at least two times. In the final paragraph, you need to develop an action statement “Call to Action” (CTA) that will tie up everything and encourage the reader to pick up the book and open it.

Add your short bio under “About the Author” and the specs of the book (the ISBN, etc) below that. Finish it off with the traditional # # # centered on the bottom, which indicates to the media person that all the words preceding the hashtags are approved for the press. To read some examples of releases, go to my website and look under campaigns.

Hire a helper or write your own releaseWriting your own materials gives you the opportunity to figure out what differentiates you and your work from others. This is a cardinal rule in marketing. However, if you are planning to hire a publicist to work on a promotion campaign, then by all means let that person write your materials. I always have a meeting with clients upfront to discuss themes and target audiences, which helps my team craft an effective release. If you’re working on your own to write the release, you can meet with an expert to get some coaching.

Paying someone to write your press materials could cost anywhere from $1,000–2,000, similar to what a resume writer charges. Anyone charging less is not reading your book and working with you to emphasize what makes you unique.

Note from Jane: To learn how to put together a press release and press kit—and learn other book marketing skills—Claire offers online education at courses.clairemckinneypr.com.

February 6, 2024

Demystifying Miscreant Memories and Crafting a More Authentic Narrative

Today’s post is by freelance writer and editor Brittany Foster.

Ask me what I ate for breakfast on Tuesday of last week and I won’t be able to tell you. Maybe a bagel? Fruit? Definitely tea. Unless that’s when I ran out…

This isn’t different from most people. Except I happen to be a memoir writer. And if I can’t even tell you that, how can you trust me to accurately recreate scenes from my distant childhood?

I think the answer lies in having a willingness to objectively examine your miscreant memories to determine where—and if—they belong in your story.

Such as this one:

When I was a child, I remember a colorful houseplant in my mother’s room. Green with pink-streaked leaves. Maybe a croton or a rubber olant. Whatever it was, those leaves called to me, the pastel pink so like sugar cookie icing. I couldn’t resist them. I’d eaten vibrant plants before. Peppermint-flavored teaberries and sun-warmed wild strawberries. Surely, this would be just as delightful.

Squatting on the carpeted floor by the bed, I checked to make sure no one was watching before snapping off a leaf and stuffing it into my mouth. I bit into it and balked. It wasn’t sweet. It was caustic and it burned my tongue, coating my mouth in bitter juice.

Just then, my mother turned the corner to catch me cringing with chunks of leaf stuck to my chin.

“SPIT IT OUT! IT COULD BE POISON!”

I spat a wet, green mouthful of half-chewed leaf onto my stepfather’s jeans, which had been carelessly left in a rumpled pile on the floor. My mother ran to me, peered into my open mouth to make sure there was nothing left, and roughly wiped the spit from my face with her sleeve.

Her yell alerted my stepfather, who came into the room after her.

I was terrified of him. Of being caught between the bed and the wall.

With my mother, I moved to the doorway as she told him what had happened. But he wasn’t relieved. He was angry.

I’d had the audacity to spit on his clothes, dirty and wrinkled as they were.

He started to yell. To come toward us.

My mother grabbed me by the arm, hauling me to the front door as his screams followed us out of the house. He wanted to get hold of me—to punish me—but we were running. She threw me into the car and peeled out of the driveway.

We went to my grandmother’s, who sat me down at the kitchen table with a bowl of old-fashioned mixed candies to soften the plant’s aftertaste. They looked like pieces of red and green sea glass and they stuck to my fingers as I picked through them.

The sound of teaspoons swirling in hot mugs of tea is the last thing I remember.

A few months ago, I asked my mother to tell me what she could recall about that day.

“Oh, Brittany,” she said. “I don’t think that happened—I don’t remember it!”

That checked me. Was I wrong? Had it been a dream?

It couldn’t be.

It’s been a part of my history for decades. I can feel the pink, plush carpet beneath my bare feet. The acerbic taste of the leaf on my tongue. I remember my heart pounding and the tackiness of the bright candies.

But if it really did happen, why doesn’t my mother—my only witness—remember it?

It could be because, to her, it was just another day in our life. More yelling. More running. More trauma. Same old.

It could also be because it didn’t happen to her. She was there, yes. But as a witness, not a victim. Multiple studies have been done on the unreliability of eyewitness testimonies. And, although it’s true that trauma can distort memories, and false memories are more likely to surface in those with PTSD (like me), this has been a very clear and distinct memory in my head for a long time. Its remembrance wasn’t triggered by another event or mental probing.

Being a memoir writer, this leaves me in a bit of a pickle. Especially since, as an MFA student in a creative nonfiction program, one of the key messages our instructors pound into our heads is “don’t make s*@t up!”

And I’m not. At least, I don’t think I am.

The truth is that this memory is real to me. But I can’t tell you with complete certainty that it did or didn’t happen.

When I brought it up with my therapist, she assured me that the memory was, in all likelihood, real. She said that the fact that my senses were so entwined with the memory added to its validity because the same part of our brains that is used to process sensory information (the parietal lobe) is associated with memory retrieval and autobiographical memory.

So, do I write it as truth when my only witness doesn’t remember it? Or do I leave it out, even if it serves my story?

I’m not alone in asking this. It’s an issue that many memoir writers will face. How do you trust yourself or your sources when memory is so fallible? When your witnesses are unreliable or when you’re trying to dig up questionable childhood memories from thirty years ago?

I owe it to my readers to tell them the truth. But what do I do when the truth isn’t black and white? When the only facts I have are based on my memory and they conflict with someone else’s?

The key is to understand how multifaceted truth can be. We only need to look back to the infamous dress or the green needle/brainstorm audio clip to see that reality and truth are intricately tied to perception—both physiologically and psychologically. And if our perspective is wholly unique, the only truth we ever really have beyond blatant fact is our own.

But let me be clear: this doesn’t mean you should serve muddled or unverified memories to your readers as hard truths. Instead, use your skill and experience as a writer to tell them exactly what it is they’re reading. And learn how to work through misty memories.

Some authors do this using footnotes, like Tara Westover. Others, like Caitlin Doughty, distinguish between what she remembers and what was most likely to have happened in scene. Many writers address this in their notes on sources.

And for others, like me, it means putting in the time and work to analyze a questionable childhood memory from a psychological perspective and deciding whether or not it deserves to be part of my narrative. For example, because this particular memory is hard to verify, and I have others that are easier to confirm and that serve the narrative in the same way, I decided not to include it in my book.

However you approach it, just don’t try to pass off murky, half-memories as full-on facts. Your readers aren’t going to expect you to remember every single detail from your life. But what they do expect is honesty. And being upfront about what you do—and don’t—remember is what will give your narrative authority and authenticity.

February 1, 2024

Writing Hasn’t Won Me Fame or Fortune, But It’s Brought Me Friendship

Photo by Daniel Richard

Photo by Daniel RichardToday’s post is by author Liz Alterman.

While querying agents and surviving submission, one thing that may keep you going is visualizing your story out in the world, hopefully, loved by the masses.

Along with that, you may imagine hosting a reading before a packed house or even a small crowd of well-wishers huddled inside your favorite bookstore. But in recent months, multiple viral posts have shown authors, their expressions somewhere between disappointed and devastated, staring at a sea of empty chairs. Unfortunately, this isn’t uncommon.

Even with the best pre-event push, there’s no guarantee you’ll fill the seats. Last March, I had a reading scheduled at a charming new bookstore. The shop’s owners and I posted about it on social media. I invited friends and included it in my newsletter. But as that dark and chilly evening arrived, I had a feeling it would be a low turnout.

Minutes before the event was slated to begin, the store was nearly empty. Making things more awkward, my novel’s editor and my agent, who both lived in the area, were there, witnesses to just how wildly unpopular my book seemed to be.

I paced the shop, wondering if I could go hide in the bathroom and attempt to teleport back to the safety of my home. When a couple walked in, I experienced an embarrassing rush of narcissistic feelings, a desperate, “Please be here for me and not to buy a last-minute gift for the birthday party your child’s attending tomorrow!” neediness.

Mercifully, they took their seats and what began as one of the most cringeworthy nights of my writing career transformed into possibly the loveliest.

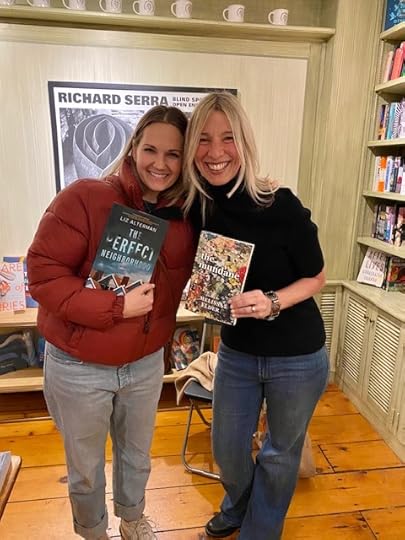

Melissa Elder and Liz Alterman

Melissa Elder and Liz AltermanThe couple—poet Melissa Elder, author of Nostalgia, and her husband Brad, asked thoughtful questions: How did the idea for my novel come about, what did my writing process look like, and could I share my path to publication? (I joke that bookstores should hire them for future events because their questions fostered such an engaging discussion.)

Because it was an intimate gathering (putting a positive spin on it), we got to chat about writing on a deeply personal level and the reading blossomed into a conversation.

Since that evening, Melissa and I have become good friends. Together, we’ve checked out new bookstores and enjoyed long lunches where we discuss our latest reads and the ups and downs of the writing life. We discovered that our shared interests extend to art, photography, and arboretums as well.

We’ve supported one another at subsequent events and I was thrilled to return to that same bookstore when Melissa celebrated the launch of her latest poetry collection.

It might be cliché to invoke the “quality versus quantity” adage here, but I’d happily trade a line out the door for one person who becomes a treasured friend.

That said, if you’re hoping to attract a crowd, I reached out to authors who shared several ways to set yourself up for a successful event:

1. Spread the wordJessica Payne, author of Make Me Disappear, The Good Doctor, and the forthcoming Never Trust the Husband, recommends advertising early and often. “Tell all your friends and family,” she says. “Post about it—more than once!—on your social media, preferably using a bright graphic. I make my own graphics in Canva, and try to go with something that both looks bookish but is easy to read.”

Payne suggests the following posting schedule:

two months outone month outa week outa day or two prior“I also always send this out to my newsletter list,” she says. “I get the impression that some authors think people will simply show up because it’s at a local bookstore that posts about it—but that may have limited reach. You know where your readers are, so meet them there.”

Beyond social media, Payne posts on her local Facebook community pages.

“They’re almost always open to community events,” she said. “I explain I’m a local author, give a tidbit about what I write, then share the details, along with the event graphic. I’ve met many new readers this way and it’s led to invitations to do events at other local locations.”

2. Team up with other authorsPartnering with fellow authors can increase the crowd exponentially and also make things more interesting for attendees. While authors often appear “in conversation” with others who write in the same genres, it’s fun to team up with those whose books fall into different categories. This not only broadens the appeal of the event but also may attract new readers.

Lee Kelly, author of the thriller With Regrets, joined forces with Victoria Schade, author of the romance Dog Friendly and Jenni L. Walsh, author of the historical novel Unsinkable, for an event.

“We had wanted to do something for Jenni’s release and given that Victoria and I write in such different genres, a ‘genre sampling’ seemed to make a lot of sense, as there was little else to thread the books together into one event,” said Kelly.

3. Offer something extraTo bring some cohesion to that event, Kelly, Schade, and Walsh presented “A Shelf Tasting: Three Authors, Three Desserts, A Delectably Good Time,” featuring treats from each of their novels.

Kelly added that having something that combines love of reading with another element makes it more memorable for attendees.

Payne agrees. “I never call it a mere book signing, which gives me visions of a long line to a folding table and little else,” she says. “With my latest event, I’ve called it a bookish party. What I actually put in my newsletter: ‘We will talk all things books and writing. I’ll do a brief reading, answer questions, and yes, as always, there will be wine!’ I don’t think people exactly come up for the wine, but I do think it makes it feel fun, fancy. I try to also have nonalcoholic options.”

Last August, Payne celebrated her birthday at her local library with a “bookish birthday party.”

“I got mini cupcakes and it was fantastic,” Payne says. “I think part of it is remembering this is supposed to be fun for you and your readers, and that you don’t have to do it the way it’s always been done.”

If your event doesn’t turn out as you’d hopedEven when people promise to attend, bad weather, transit problems, sick kids, and work issues often get in the way.

Should this happen to you, it helps to keep in mind that you’re in good company.

In her funny and honest essay, My Life in Sales, Ann Patchett recalls her experience while touring with her first novel The Patron Saint of Liars. Patchett wrote that approaching the stranger at a bookstore’s cash register to introduce herself was often the most awkward part.

“We would look at each other without a shred of hope and both understand that no one was coming,” she explained. “Sometimes two or three or five people were there, sometimes they all worked in the bookstore, but very often, in the cities where I had no relatives to drum up a little crowd, I was on my own.”

If it can happen to Ann Patchett, it can happen to any of us.

Tom McAllister, author of How to Be Safe, shares a similar tale in his essay Who Will Buy Your Book in The Millions, which opens:

“Nobody else is here,” the elderly woman said into her phone. “It’s embarrassing!” She was the first one to arrive at my reading at the Philadelphia Library, a week after the release of my third novel, and two weeks after the pinnacle of my writing life, when that novel was praised in both The New Yorker and The Washington Post, two articles that I had assumed would create something like buzz around me or my writing. It was 6:58, and the reading started at 7:00.”

When things don’t unfold as planned, Payne’s advice is to go with the flow. “My bookish birthday party was going great—until I realized we forgot both the books and the cupcakes at my house, a twenty-minute drive away,” she recalls. “My husband raced off to retrieve them, but in the meantime, I had a crowd of twenty-five-ish staring back at me. So we chatted some, and I explained the situation and laughed with them about it.”

Payne notes the worst part was that initially she didn’t think she had a copy of her book to read from. “But then I remembered I had a digital copy in my Kindle library,” she says. “So I read from that. And then turned that into a fun tidbit to share on my newsletter. In the end, it was fine, funny even. But first there was definitely a moment of panic.”

If you’re hosting an event, publicize it and hope for the best. But attendance is largely out of your hands. If you end up with only a few guests, I hope you get as lucky as I did.

January 31, 2024

The First Rule of Writing Is Writer’s Block Does Not Exist

Today’s post is by SaaS copywriter Alexander Lewis (@alexander-j-lewis).

On New Year’s Eve 2022, I stood in my backyard surrounded by friends, finishing the last drags of a cigar. In the dark, we took turns sharing our hopes for 2023. I knew my goal. It was clear and succinct in my mind because I’d been noodling on it for weeks. But as others shared one by one in a circle, I second-guessed my goal. All the resolutions before mine were about family and health and finding balance in the new year. Would my resolution about business and money seem crass? Could I jinx myself? Too late. It was my turn. I stuck with my original answer, “I’m going to double my writing business in 2023.”

Crass or not, my goal wasn’t outlandish. In past years I’ve grown the business by almost 90%. But 2023 wasn’t like the previous seven years. Not even close. I didn’t merely undershoot a lofty target. 2023 was the first time my writing earnings were lower than the year before. Revenue tipped backward. Jinx!

A lot happened last year. It was a difficult and strange time to be a working writer. There were fears around AI. My sector, tech, suffered an effective bear market which resulted in a slowdown in hiring. Interest rates rose and marketing budgets were reduced. And exactly midway through the year, I endured the biggest health crisis of my life.

There’s just one problem: None of these factors were within my control. I’d be lying or lazy (or both) to say that last year’s under-performance was purely circumstantial. I made a mistake and effectively tied my hands behind my back. What do I mean? In 2023, for the first time in my writing career, I stopped writing for myself.

The best way to write for others is to write for yourselfFreelance writers have the ultimate edge when it comes to sourcing new leads. Every time you publish an article or new social post, no matter the subject, you’re marketing your services as a writer for hire. Words are your product. Writers often meet their first client by accident. You publish a blog, someone reads it, loves it, and asks you to write something similar for them—for a fee.

Call it the “flywheel” of freelance writing. Call it, “building your writer brand.” It all translates the same: The best way to write for others is to write for yourself.

I began freelancing full-time in 2016. From then until 2022, no matter how busy I was with client work, I always made time to write for myself. Blogging. Social media writing. Guest posting. Half the fun of growing a freelance business was writing the stories that no one asked for, but that I wanted to tell.

It worked. The more I wrote for myself, the more others wanted to work with me. The more publications I wrote for, the easier it became to pitch the next one. All I had to do was keep writing…

That’s where the problem originated. If the best way to write for others is to write for yourself, then the opposite is also true. The surest way to slow your writing career is to stop writing for yourself. And damn it! that’s exactly what I did.

The first ruleThe first rule of freelance writing is that writer’s block does not exist.

To write consistently for yourself, you must believe as a fundamental principle that writing is a matter of discipline. As soon as you believe (even partially) that writer’s block exists, you set yourself up for failure. Writer’s block is an excuse, based on fear, that a writer stores in their back pocket. The excuse gives you permission to quit as soon as writing gets hard.

Writing was hard for me in 2023. I think the difficulty started because I was bummed about AI. For me, writing is pleasurable because it is difficult. Now, something that was difficult in nature was made simpler by a machine. It stole some of the fun of writing. So, I stopped writing for a week. One week became a month. One month became a few. And by the end of 2023, I had almost no new personal writing to show for a full year.

I believe writer’s block starts in fear. Most often, I think it’s the fear of perfection. Writers put too much pressure on their first draft. They fear the flashing cursor and never type the first sentence. This has seldom been a problem for me.

Writer’s block arrived for me in the form of a different fear. It was the fear that my work was made meaningless by a machine. It’s silly when I say it out loud. Finding meaning in one’s work is a matter of choice. Besides, if the process of writing is what makes it meaningful to me, then I can continue to write however I please.

Still, I never rationalized my way out of fear. The result was I ignored the blank page. The worst part is that I missed it.

It takes guts to writeThe best writing is scary to publish because it is vulnerable. It takes guts to share your stories and ideas. People can misunderstand. They can object. Clicking publish makes you an easy target to be picked on. Maybe you’re wrong and are called out publicly. Or maybe you’re right and called out anyway.

Every writer must decide for themselves if the vulnerability is worth it. For me, there’s almost no activity I love more than clicking publish on an idea I’ve wrestled with in silence for hours.

A few weeks ago, my wife Sarabeth and I took a walk around Lady Bird Lake in Austin. We let our aussiedoodle Oliver off-leash to sniff around for lost tennis balls at Zilker Park. That’s when I had a new idea for setting resolutions. “What if we set resolutions for one another, based on what we think would make the other happiest?”

We each mulled over possible resolutions in silence for several minutes. I leashed Oliver again as we reached the end of the park. We continued down the sidewalk and then the dirt path. I shared some resolutions for Sarabeth and she gave me a few in turn. One of them was clearly the most important.

“I think you’re happiest when you’re writing,” Sarabeth said.

I still have lofty financial goals for my writing business this year. But my primary goal for 2024 will not be a revenue target, but a writerly one. I am returning to the foundations of a good writing life. My resolution is to rediscover my writing routines and start publishing my work once again.

If the past eight years of freelancing have taught me anything, it’s this: When I write for myself, the revenue takes care of itself.

January 30, 2024

Want to Improve Your Amazon Ranking? Improve or Update All of Your Book Descriptions

Photo by Miguel Á. Padriñán

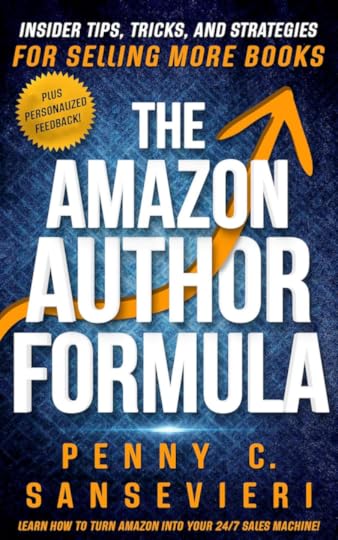

Photo by Miguel Á. PadriñánToday’s post is excerpted from The Amazon Author Formula by Penny Sansevieri.

Let’s say you’re running some Facebook ads and you’re getting lots of clicks, but no sales. This tells Amazon your book isn’t relevant to the search, and that will impact your search rank on Amazon.

Really?

Yes, really.

Amazon’s goal is to serve up things its consumers want to buy; the site isn’t there for window shoppers, and the website is quite intelligent. If someone lands on your book page and immediately clicks off without engaging with your page at all (expanding your book description to reach more, scrolling down to read the reviews), that tells Amazon your book isn’t right for the market; consequently, it becomes harder to rank. So if you’re thinking about your own Facebook ads (or even your Amazon ads) that are getting lots of clicks but no buys, you may want to consider how it’s impacting your relevancy score and your overall visibility on Amazon.

So, how far back does Amazon go when considering your overall relevancy score?

Remember that first book you published that didn’t do well? The cover wasn’t great—you knew it could have or should have been better—but it was your first book, so you took it in stride. You learned from your mistakes and you moved on.

The thing is, Amazon never moves on. Somewhere, lurking in the back end of Amazon is a black mark beside your name, and that mark means, This author once published a book no one seemed to like = low relevancy.

Amazon cares about relevancy. It’s how the entire site—with all of its millions of products—manages to find exactly the thing you’re looking for when you need it. Plug in a few keywords and, boom, the exact widget, lotion, or book you were looking for appears. This is why relevancy is so important and why making sure everything connected to your Amazon account (even the older books you’ve published) is in tiptop shape. This point can’t be overemphasized.

The other element of this as it relates to Amazon ads is that the less conversion you have on your Amazon book page (i.e., the lower your relevancy score), the more your ads will cost you. And if your ads never seem to do well across the board, Amazon will ding your relevancy score as well. If you have an ad set that’s not doing well, kill it.

Is there any hope for that older book that didn’t do well? Fortunately, there are some options. Often, it means revisiting an older title, maybe republishing it, revamping the cover, or in extreme cases, taking it down entirely. But that’s pretty much a last resort.

A few years ago I noticed that our website wasn’t ranking as well as it should for the term “book marketing.” Considering that that’s the work we do, it’s a pretty important term to rank for. Upon investigation, I discovered that a page on our website was broken. By “broken,” I mean it had no keywords, no title tags; it was basically a mess. I fixed it and within about three months, our website was back and ranking again.