Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 36

April 2, 2024

How to Teach Word a Scrivener Trick

Today’s post is by author Wendy Lyons Sunshine.

Just as mountain climbers need a sturdy harness and strong rope to reach the summit, writers depend on robust digital tools to carry us through to a book deadline.

For my latest book, I wanted tools that would let me efficiently juggle a great deal of content and citations. The first choice for my toolkit was Zotero, a citation manager that lets you grab information with a single click of a browser extension, conveniently links text, notes, and tags to the citations, and outputs formatted citations with a few clicks.

But settling on a word processing choice was trickier.

My wish listI spent a few years as a technical writer, hammering out data-heavy documents and ushering them through multiple revision and output cycles. When you’re elbow deep in hundreds of pages, continually moving graphics, tables, and chunks of data, the last thing you want is to format, mouse, scroll, or cut and paste more than necessary. The right tool offers shortcuts and flexibility. Our group relied on specialized software called FrameMaker to boost efficiency and maintain quality.

For my own book, I imagined a tool that could likewise weave together varied content: personal narrative, as-told-to stories, case studies, heavily cited exposition, and graphics. At minimum I wanted:

Auto-generated outlinesTo easily jump forward or back among chapters and sectionsTo easily reorganize material in a modular manner, using high-level drag-and-drop (like cut and paste, but on steroids).Fortunately, the first two capabilities are easy to find. Google Docs and Microsoft Word, for example, both support heading styles and outlining capabilities. My wish for the third capability got me flirting with Scrivener.

Scrivener’s allureProfessional writer colleagues rave about Scrivener’s drag-and-drop flexibility, and I felt compelled to give it a look. After a tutorial, I noodled around with a dummy draft. Scrivener’s “bulletin board” with “notecards” did appear to be a powerful organizational tool, making it easy to focus passages and rearrange content.

What daunted me, however, was how to output a draft and incorporate revisions. From what I could deduce, Scrivener outputs to standard formats, but real editing must be done within Scrivener. That meant any changes that I or someone else marked on a draft (output to Word, for example) had to be input into Scrivener, instead of just accepted into the document. Perhaps I missed something buried in Scrivener’s menus, but I couldn’t see any way to easily and productively collaborate on drafts with my editor.

Stumped, I took a fresh look at Word. Could it be coaxed to approximate Scrivener’s powerful visual and modular drag-and-drop feature?

Ultimately, yes. The trick is inserting many descriptive, often temporary, headings in combination with Word’s styles and navigation pane. Here’s how it works:

Getting Word to behave more like ScrivenerInsert descriptive headings throughout the manuscript. You might insert a heading above each:

ChapterSectionSceneFigure or illustrationSidebarAny unit of content that needs to be easily identified or moved.The goal is to clearly identify where a chunk of content begins. By default, that chunk ends where the next chunk (denoted by a heading of the same level) begins.

Assign stylesOpen Word “Styles” and assign each of the descriptive headings a standardized heading style. Assign “heading 1” style to chapter titles, then assign “heading 2” to other types of content. (This keeps the hierarchy as flat as possible to begin; more levels can be added later, after you get the hang of it.) Here’s an example of a nonfiction manuscript set up this way:

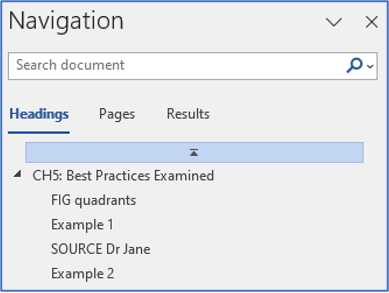

Open the Navigation Pane

Open the Navigation PaneNow that headings are set up, open the navigation pane via View > Show > Navigation Pane. The Navigation Pane will display vertically along the left of the screen. For the sample pages above, it would look like this:

Use the Navigation Pane two ways. First, you can navigate to specific content by clicking on that specific heading. Second, and most wonderfully, you can reorganize content by dragging and dropping the headings. Navigation Pane headings behave much like Scrivener’s index cards and are easily shuffled around.

Dragging a heading moves all associated content together in one bundle. This works beautifully across a large document and is far easier than trying to cut/paste/or drag blocks many pages apart.

Craft headings strategicallyBy crafting brief, standardized headings, you’ll make it easy to scan and browse the Navigation Pane. I sometimes use ALL CAPS to make certain information more prominent.

That’s why in the sample shown above, chapter is shortened to CH#. This leaves room to see more of the full title in the pane and also to scan visually for chapters across the entire book. Source interviews are , and graphic elements are identified as .

For fictionFiction writers can adjust this approach for their needs by crafting headings to describe POV, scene, location, interiority, backstory, etc.

Below, on the left, is an imaginary raw fiction manuscript set up this way. On the right, content has been dragged and dropped into an alternate sequence using the Navigation Pane. Notice that on the right, backstory segments were nested or “demoted” by changing from Heading 2 to Heading 3.

Getting creative

Getting creativeAt one point during my book’s evolution, I wanted to keep an eye on word counts. The Navigation Pane helped there, too. First, I checked a chapter’s word count, then embedded that total into the heading format of , such as “750 CH8 Attunement” or “5000 CH2 Science of Family.” Then I could scan for chapters that were complete versus those that needed more content.

Last stepsWhen the draft was ready for final production, all I had to do was strip out superfluous headings and replace abbreviations with the full spelling.

Despite the extra effort of inserting headings and stripping them out later, this strategy was a huge help. It allowed me to play with my book’s structure and track where I had located case studies, visuals, and so on. It reduced scrolling and prevented messy cut and paste errors. As a final bonus, I didn’t have to master new software while under deadline pressure!

Final note: If you run into trouble, double check Word’s advanced settings to make sure that drag and drop is enabled via: File > More… > Options > Advanced > Allow text to be dragged and dropped.

March 28, 2024

How Do You Know What Backstory to Include?

Photo by Eepeng Cheong on Unsplash

Photo by Eepeng Cheong on UnsplashToday’s post is by editor Tiffany Yates Martin (@FoxPrintEd). Join her for the three-part online class Mastering Backstory for Novelists beginning on April 10.

Backstory tends to fall into two main categories. The first and most ubiquitous kind pervades the story with subtle brushstrokes, filling in texture and depth and color on its characters and world. It is infused throughout almost every line of well-developed story like oxygen—you may never notice it, but it’s essential.

The second paves in elements of character or plot background that play a specific or significant story role. This type of backstory may be more overt, and can even take center stage at times: particular history or circumstances that are integral to the plot.

In both cases, though, backstory risks feeling clumsy or intrusive if it’s not directly relevant to the main, “real-time” story.

Related: Backstory Is Essential to Story Except When It’s Not

The challenge of incorporating backstory fluidly and organically is to know which aspects of a character’s past and the circumstances of their present are in fact essential and intrinsic to the actual story, not extraneous or distracting.

What makes backstory intrinsicCharacters, like human beings, aren’t made up of merely a handful of traits, experiences, and behaviors. They—and we—contain multitudes.

Yet all readers see in your story is one sliver of that complex pie: the remnants and fallout of past and current influences that help determine how characters act, react, and interact in this story.

You can’t bake just a slice of pie, though. As the creator, you’ll want to know more about your story world and the people who populate it—to bring the story more realistically, vividly to life, even if not all of that backstory makes it onto the page. But trying to present all and every detail of those influences would overwhelm the story, dilute it. You have to determine which parts of the character’s life before your story begins are directly intrinsic to the story readers are now experiencing. Backstory is intrinsic when it immediately and materially serves the story in some key way.

Intrinsic backstory has a direct bearing on why the character acts, reacts, behaves, or thinks as she does in this story.Everything characters do, say, and think is rooted in the factors that have shaped them in the past, as well as their present circumstances, aside from what’s actually happening in the scene.

Is your character habitually late for work, going through a divorce, a former combat veteran, an assault survivor, just had a fight with their kids for the millionth time about homework, for example? Any of those factors may play some role in what the character feels, thinks, and does in the scene, even if it’s not about those things.

Authors obviously don’t need to track back the origins of every single aspect of character behavior, but offering shadings of context can deepen characterization and help readers more deeply invest—both in key story areas and where their actions or behaviors might otherwise seem opaque, confusing, or inconsistent.

Bonnie Garmus uses backstory for both these purposes in this scene in Lessons in Chemistry, when protagonist Elizabeth Zott is told horrific news:

When Elizabeth was eight, her brother, John, dared her to jump off a cliff and she’d done it. There was an aquamarine water-filled quarry below; she’d hit it like a missile. Her toes touched bottom and she pushed up, surprised when she broke through the surface that her brother was already there. He’d jumped in right after her. He shouted, his voice full of anguish as he dragged her to the side. I was only kidding! You could’ve been killed!

Now, sitting rigidly on her stool in the lab, she could hear a policeman talking about someone who’d died and someone else insisting she take his handkerchief and still another saying something about a vet, but all she could think about was that moment long ago when her toes had touched bottom, the soft, silky mud inviting her to stay. Knowing what she knew now, she could only think one thing: I should have.

Elizabeth’s history with her brother doesn’t play a major role in the story or her arc, and it has nothing overtly to do with the police informing her of a death. But her flashing back to that moment in this scene lets readers feel the impact of it on her, and explains her seemingly passive reaction. Garmus weaves in specific background details like this one to create a full, believable portrait of why Elizabeth is who she is when readers “meet” her, and to show why she behaves, reacts, thinks, and acts as she does.

Intrinsic backstory has a direct bearing on what is happening in the story and is necessary to fully understand it.Characters don’t exist in a vacuum, and readers need some understanding of the backdrop of their lives, past and current.

That doesn’t mean creating exhaustive descriptions of the company they work for and their entire history there, or info dumps on the geopolitical situation and social mores of the time, or biographical deep dives on their social circle. It simply means setting the stage, painting in enough detail and context so that readers get a realistic sense of the characters, their situation, and the world they live in, where relevant to the story.

In Kate Quinn’s The Alice Network, main character Charlie—back from college pregnant at 19, unwed, and a disgrace to her parents—is en route to Switzerland with her scandalized mother in 1947 for a clandestine abortion, though she plans to sneak off to London on the trip to pursue a lead on her beloved cousin Rose, missing since the war.

Readers need to understand several aspects of Charlie’s backstory to fully invest. The historical and social backstory of Charlie’s world is directly germane in that it makes her pregnancy more scandalous and more urgent—abortion is illegal in the U.S. in 1947, and having a child out of wedlock is likely to cost Charlie her reputation and her future in her upper-middle-class, post-WWII environment. The recent war is also a motivating factor in Charlie’s arc: her brother’s death as a result of the war and her cousin’s disappearance after it.

Quinn gradually laces in context about Charlie’s brother’s suicide after he returned from combat, missing a leg and mentally troubled, a factor intrinsic to Charlie’s state of mind that led to her uncharacteristic behavior with the boys at her school and her pregnancy. Her guilt for not being able to help him is a major driver of her compulsion to find Rose.

The author also threads in Charlie’s backstory with Rose, slowly painting a picture of their unusually close relationship, Rose’s disappearance and its impact on Charlie, and paving in more reasons Charlie feels driven to search for her.

These details of Charlie’s past help readers vividly understand Charlie’s goal of finding Rose, the character’s central driving motivation and the engine of the plot.

Intrinsic backstory has a direct bearing on the stakes in the story.To fully invest in a story and characters, readers need enough context, history, or background to understand why what’s happening in the “real time” story matters right now.

In The Hate U Give, author Angie Thomas has just a handful of pages to make readers care about the character of Khalil, a childhood friend of protagonist Starr’s who has become a drug dealer, before he’s shot in a traffic stop by police. And Khalil’s importance to her is also crucial to establish believably and deeply, as it’s a central motivator for the plot and Starr’s character arc: Will she risk her friendships, her community, and even her life to testify about his death publicly?

So readers need enough backstory on Khalil to care, without stalling out these crucial opening pages of the story.

Thomas does it with several well-chosen snippets of Khalil’s character’s history and circumstances: Starr recalls his grandmother bathing them together when they were very little and “we would giggle because he had a wee-wee and I had what his grandma called a wee-ha,” a shard of memory that connotes childhood innocence.

We learn his mother has been addicted to drugs most of his life, and Starr recalls “the nights I spent with Khalil on his porch, waiting for his momma to come home.” This shows Khalil’s caring side, reveals a factor in his upbringing that is directly germane to his current situation, and also reinforces the lifelong bond between him and Starr.

That connection and his thoughtfulness and care are underscored a few pages later when he teases Starr that he’s older than she is by “five months, two weeks, and three days,” winking as he says to her, “I ain’t forgot.”

And just a few pages later, when Starr badgers him about quitting the job her dad gave him and selling drugs, Khalil says, “That li’l minimum-wage job your pops gave me didn’t make nothing happen. I got tired of choosing between lights and food,” and reveals that his grandmother was fired from her hospital job because her chemo treatments left her unable to “pull big-ass garbage bins around,” and she could no longer support Khalil’s younger brother, abandoned by their mom. These well-chosen details depict relatable, human reasons he felt driven to sell drugs—to care for his family—and build reader investment in his character.

Khalil is present and alive in the story for just 12 pages before he’s killed, but in that brief time Thomas laces in ample backstory to give his character the importance he has to have for the entire plot and Starr’s character arc to be effective. Starr’s relationship with Khalil and his background and family situation are essential for readers to see the fullness of who he is and to care about his death.

Tips for choosing backstory elementsBackstory can clutter the story when:

it isn’t directly relevant to the main story or charactersits sole purpose is to offer information and it doesn’t move the story forwardit’s more detailed/expanded than the story requires and stalls momentumTo keep backstory to just the necessary components:

The facts may be relevant, but not the details (e.g., that your character overcame a stutter early in life may matter, but not the specifics of how).You can convey a wealth of backstory with a single well-chosen representative detail (as Angie Thomas does in the examples above).Backstory is not the story—if it’s taking over your story, you may not be focusing on the right one.Read more: How to Weave in Backstory without Stalling Out Your Story

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us for the three-part online class Mastering Backstory for Novelists beginning on Wednesday, April 10.

March 27, 2024

Using Beat Sheets to Slant Your Memoir’s Scenes

Today’s post is by writer and editor Lisa Cooper Ellison. Join her on Wednesday, April 3, for the online class Craft Your Memoir’s Beat Sheet.

Most memoirs involve some kind of loss—a breakup, a displacement, a dismantled dream, the death of someone dearly loved. The more painful the event, the more you’ll want to write about it. But as you revise, you’ll discover that some (or many) of your scenes aren’t needed.

To figure out what’s important, and how to write about it, you need to identify your memoir’s beats. Beats are part of the Beat Sheet tool Blake Snyder created for his book Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. These turning points work together to create a propulsive story that largely follows the hero’s journey—though once you understand the concept, you can apply it to other kinds of stories, like the heroine’s journey.

While it can be easy to spot the beats in a memoir with a clear quest, even nonlinear memoirs have them. Identifying both the beats and their functions can help you slant your material so that your book includes the right details in the right place to tell the right story.

Let’s say your book involves a breakup. Early drafts might include your courtship, the moment when you truly committed, the initial cracks in the relationship, the fights that led to the big eruption that ended everything, and all the post-breakup things your ex did that thoroughly miffed you.

This is a great start, but even when the relationship plays a prominent role, it’s likely you’ll need to trim things down. Before cutting too many darlings, or giving your book a full on weed whack, you’ll need to identify your book’s narrative arc, or the arc of internal transformation that happens within the narrator. Creating a beat sheet populated with your book’s key moments can help you identify how your narrator changes and which scenes illustrate this transformation.

If we continue with the breakup example, a beat sheet might uncover that your book is a harrowing tale of abuse where the breakup is a moment of victory that wraps up your book. But maybe you’ll discover that you’re actually writing about something else, and the breakup is either an unfortunate (or welcome) casualty of the primary story, or maybe the breakup is simply a catalyst that launches your journey.

Once your narrative arc is clear, you can decide how much real estate the relationship deserves, where the breakup belongs, and how to frame it so that it serves a specific function. To help you see what this looks like, let’s explore how breakups are framed in four different memoirs. (Warning: spoilers ahead!)

Breakup as ordinary worldElizabeth Gilbert’s memoir, Eat, Pray, Love, is about what she discovers about life, love, and herself after divorce. Her ordinary world, or the world before the quest begins, is one where a woman realizes she wants out of her marriage. Her divorce is important, because it sets the stage for what comes next, but it’s not the story, nor is it the catalyst inviting her on her journey.

In one of the book’s opening scenes, Elizabeth presses her head to the floor and realizes she doesn’t want to be married any more. Then, within the first 35 pages of her memoir—during which she gets divorced and has an unhealthy relationship with another man—she decides to travel to Indonesia after being invited by a medicine man (the story’s catalyst). Little of Gilbert’s marriage or divorce makes it into the book.

But what if the relationship takes on a larger role? How might that change the location and slant the breakup takes?

Breakup as opening for something newAccording to Blake Snyder, your midpoint can either be an up moment where “the hero seemingly peaks” or a “low point where the world collapses around them.”

Suzette Mullen’s new memoir, The Only Way Through Is Out, is about risking it all to become who you truly are. It’s an identity story where one of her primary conflicts is whether to stay in her 30-year marriage. The decision to leave happens around the midpoint. Initially, it seems like a victory that makes room for her to pursue what she hopes will be a more authentic life. Then, a discovery about her ex occurs at the All Is Lost moment, which sends her life into a tailspin.

Breakup as unravelingDivorce also plays a prominent role in Safekeeping by Abigail Thomas, a memoir about her second husband. Many writers hope to emulate this book because of the rules it breaks around chronology and point of view. But the story works precisely because it includes a whiff of narrative arc around her relationship with Husband Number Two. In fact, the book’s short vignettes largely chronicle their courtship and marriage, divorce, and reconciliation. Because the whiff of arc exists, it’s possible to identify the book’s beats.

The breakup in Safekeeping also takes place around the midpoint, but unlike Suzette’s false victory, it’s a deep low that Abigail briefly, yet specifically, describes. She stops cleaning, caring, or wearing anything other than her nightgown. Her children scatter. On days when she’s supposed to look for work, she smokes cigarettes, drinks coffee, and wanders, feeling completely lost. It’s so lonely, she welcomes back the raccoons she’d once complained about.

Breakup as reliefSometimes the breakup is the victory that wraps up the book. When that happens, you must decide if it’s the finale or if it’s setting the stage for it.

In Carmen Maria Machado’s memoir, In the Dream House, the narrator spends most of the story pretzeling herself into a shape she hopes her partner will love. The book is filled with push/pull moments where the narrator is rejected only to be sucked back into this toxic relationship’s vortex. At the All is Lost moment, the woman from the Dream House breaks things off with the narrator, but then she recants only to say it was all a mistake. Or was it? The narrator reels, knowing the relationship is poison yet she feels powerless to resist its sweetness. In the Break into Three—or the point where the hero figures out how to solve her problem—she cuts all contact, making the breakup permanent. It’s not the book’s ending, but it’s where the narrator’s healing begins.

You can apply this work to your memoir by following these steps:

Learn all of Blake Snyder’s beats, such as the midpoint, “All Is Lost” or “Break Into Three” (here is a brief summary of all beats)Identify the scenes that serve as beats in your memoirUse your scene list to determine your narrative arcSlant key scenes so they do their beat’s primary workScrap anything that doesn’t belongLearning to do this can streamline your revision process. As you complete this work, you’ll feel more confident about what truly belongs in your memoir, and more importantly, you’ll know which details matter most.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Wednesday, April 3 for the online class Craft Your Memoir’s Beat Sheet.

March 26, 2024

Pay Attention to the Obsessive Workings of Your Mind

Photo by Ian Noble on Unsplash

Photo by Ian Noble on UnsplashToday’s post is by author and editor Lynn Schmeidler (@lynnschmeidler).

On New Year’s Day, during my senior year of college, a gruesome double murder took place in my hometown. The couple stabbed to death in their sleep lived across the street from my aunt and uncle, around the corner from my childhood best friend, doors down from where another old friend grew up.

Like everyone else in the town, I was shocked and frightened by the news. Although fingerprints were left all over the house, no match for them was found. Time passed but the case remained unsolved. The theory: it was a drug crime. The victims were doctors, so someone in search of drugs followed them home on the commuter train, and something went terribly wrong.

Four years later, when a suspect was finally arrested, my connection to the murders became even closer: the young man indicted was the quiet boy from the back row of my fourth-grade class. I was shocked all over again.

The case was big news, not only for those of us with connections to the town, but for the courts as well: the defendant confessed within the supposed guarantee of confidentiality of an AA meeting. He had been drunk; the murder took place in his childhood home; he thought he was killing his parents.

I couldn’t stop thinking about his childhood—what went on in that home that would drive him, in a drunken rage years later, to murder his own parents. And also what it was like for his parents, defending the son who the world knows tried to … meant to … did! kill them. And was he one of the boys I briefly crushed on in fourth grade?

I encourage my writing students to take their obsessions seriously, to follow them, delve into them. What we obsess about is our material. The story of the murders obsessed me. Because it took place in my hometown. Because I grew up with the man who committed the murders. Because the victims were not the intended victims. Because the intended victims were the parents of the man who killed them. The story of the murders, though, had already been told in countless news articles. Even in an episode of Law and Order. My task, then, was to find a way to tell my fiction about the facts.

So I went back to what the story did to me. It destabilized me. I could relate to everyone in the story—the dead, the convicted, the relatives of the dead, the intended dead. Then I asked myself: what else destabilizes me? Contemporary art—its rawness and its familiarity; secrecy—its power to protect and its certainty to betray; #metoo stories—their ubiquity and their endless ability to enrage.

Through the expanded field of these other concerns, I found my way into my own telling of the story: in “The Audio Guide,” a young, female museum intern takes revenge on the museum director (an older married man who seduced her and ditched her) by recording an explicit, tell-all narration for visitors to a disturbing art exhibit inspired by the double murders.

While headlines may inspire stories, ideas need not arrive as made-for-television crime dramas. With a properly tuned antenna there’s enough everyday strangeness to power an observant writer for the rest of their days: At the end of a yoga class one day, I had the distinct impression that we’d been left in savasana a bit too long. I opened my eyes to check the clock and noticed that the teacher was lying awfully still. For a moment I imagined she’d stopped breathing. Sleeping Beauty came to mind. (The yoga teacher was, as central casting and life in a 21st-century yoga studio will have it, a fairy-tale beauty—lithe body, perfect skin, waist-length hair.)

By the time I made it home, the idea of a story had hatched—Sleeping Beauty as told today, in her own words. I am obsessed with fairy tales, especially the original ones that are darker and stranger than their commonly known, sanitized versions. A little research led me to, “Sun, Moon, and Talia,” Giambattista Basile’s early 17th-century precursor to Sleeping Beauty replete with death, rape, birth, and betrayal.

But to allow for the story to explore something meaningful to me I needed more. Something to rub up against, a question to vex. When my students feel stuck, I tell them to think of a story as a braid—what three strands might wind themselves around one another to create a denser texture to their fiction?

So here we are, back to our obsessions. Keep track of them, note them down. I have obsessions enough to weave into a goddess head of plaits. “Corpse Pose” is a braid of Sleeping Beauty, a yoga studio, and a mother-daughter relationship. In my version of the fairy tale, Beauty works for her mother and is laid out on the dais of the studio she owns.

I keep a list of what I notice and can’t seem to let go of, the subjects of my obsessions, the endless supply of everyday strangeness that fill this world: an eerie street name, a rental scam, a joke I take at first to be a real story, a rock star impersonator, a gentleman pickpocket, a breast-pump model, a rare variety of parasitic twins, a vagina makeup, a spontaneously reversed vasectomy, an art film of people sneezing out rodents, a coke-addicted silent film actress with a pet monkey, a 4,900-year-old tree, a roll of unexpectedly double-exposed film showing events from years apart, the relativity of time.

Bookshop • Amazon

Bookshop • AmazonThe trick is to pay attention to the unique workings of your own mind and to note the strangenesses that stick. They are your bones to worry—shake, chew, gnaw, lick. Wear your obsessions down, bury them, then dig them up again. While not all of my strange observations and growing obsessions have made their way into my fiction, each of the ones listed above is present and accounted for in my story collection, Half-Lives. Whether braided, expanded, or sometimes only casually noted, the headlines, facts, and observations that stick to you will seed your own work and grow it into the stories only you can tell.

March 19, 2024

Writing the Other: 4 Not So Easy (But Doable!) Steps

Photo by Agence Olloweb on Unsplash

Photo by Agence Olloweb on UnsplashToday’s post is by author and book coach Samantha Cameron.

Most writers know the importance of portraying underrepresented characters in their work but are anxious when it comes to writing about an identity other than their own. There’s pressure to get it right, and so many ways it can go wrong.

If you feel uncertain in any way about representing an underrepresented community in your work, I want you to pause, take a breath, and embrace this anxiety.

Wait, you might be thinking, aren’t you supposed to be giving me a pep talk about how this is going to be okay?

I will. In a minute. But first, I want you to embrace your anxiety about this issue, because it means you care. It means you understand that representing people whose experiences are different than your own is a meaningful responsibility. Of course you want to do it well, so that you don’t hurt people. And some part of you is worried about backlash if you “get it wrong.”

Because the consequences of getting this wrong can be significant, it can feel overwhelming to even approach this issue. So, some writers shut down and decide they don’t want to approach it at all.

Perfectionism is trying to save you from the dangers of criticism, which feeds you the lie, You’re better off not touching this. Let someone else do it. So, the first important thing to recognize is that there is no such thing as perfect representation. You’re never going to create a character that everyone universally agrees is perfect representation just like you’re never going to create a perfect book that everyone universally loves.

That doesn’t mean you stop trying. Just like you still strive to create a page-turning plot even though you know it will never be perfect. Rather than focusing on doing a perfect performance of what “good” representation is, your focus should be on creating three-dimensional characters and minimizes how much harm you do.

Okay, so how do you even do that? Although there is no formula for “perfect” representation, here are four steps that will pave the way to better representation—and better writing!

1. Conduct wide-ranging, deep research.The first step is to conduct research about the community you are trying to represent. As much as possible, strive to see this community with inside eyes, rather than solely an outsider’s perspective. If your research about what it’s like to be transgender is exclusively from the New York Times, you won’t have the full picture or the same perspective as you would get by reading The Washington Blade, an exclusively LGBTQ+ newspaper, or by reading GLAAD’s reporting.

When you’re doing this research, start with sources that are already available—books, podcasts, blogs, etc.—rather than immediately turning to the people in your life who identify with the community you are trying to represent. I’ve been guilty of this, and I’m grateful to the friends who have indulged my questions and sent me resources before I knew better. Some of your friends and loved ones might be happy to talk to you, but it can be a lot of emotional work. They may not want to unpack that with you. Besides, there are plenty of other people who have made it a part of their paid work to educate people about these topics. Go to those resources first.

2. Engage the help of beta or sensitivity readers.No matter how much research you do, you might miss something. So, seek feedback from sensitivity readers. They will specifically focus on your representation of a particular group. Some guidelines:

Have multiple sensitivity readers with a wide range of experiences. No group is a monolith, so a “pass” from one sensitivity reader does not guarantee your manuscript has avoided all harmful tropes.Look for areas of consensus. If most or all of your readers say that a certain part of your manuscript makes them feel a certain way and it’s not the way you wanted them to feel, that’s an indication to revise.Sensitivity readers are usually described as people who are from within the community you are trying to represent. I read an interesting piece from Brooke Warner in which she points out that while that kind of feedback is useful, you can get very good sensitivity readings from people outside of a community, and not very useful feedback from within. Basically, she’s pointing out that people can internalize tropes, biases and stereotypes about their own identities and not necessarily be aware of how that manifests on the page. Or, a particular person might not be bothered by a trope that really hurts a lot of other people in the community.3. Cultivate your awareness of bias and tropes.Back in 2019, one of my friends pointed me to an excellent Harry Potter podcast called Witch, Please! The hosts are lady scholars who are fans of the series but evaluate it from a critical lens. Before I listened to this podcast, I had very little awareness of anti-fat bias. In the podcast, the hosts discuss the ways that Rowling uses fatness as a shortcut for moral degeneracy. She is able to use these tropes because she can count on her audience to have the same biases. The pervasiveness and invisibility are what makes tropes and stereotypes so pernicious.

I realized when I listened to this podcast that I had a character in one of my books where I’d done basically the same thing. I’d used his fatness as a shortcut for characterizing him as villainous. So, I went and reworked that character. Instead of making him fat, I made him muscular and conventionally attractive and had to rely on other ways of communicating to the reader that this was not a trustworthy guy. In addition to removing that particular anti-fat trope, reworking this relatively minor character made him much more compelling and scarier than he originally had been. Which leads to my next point…

4. Make your characters more than their marginalization.To paraphrase Walt Whitman, we contain multitudes—and so should all your characters. We are all affected by facets of our identity, but that isn’t the whole sum of who we are. So, any time you are adding characters to your cast with an eye on “diversity,” treat them the way you treat any character. This means that you make sure these characters serve a purpose. They aren’t merely there to check the diversity box or be the butt of a joke, but to play a role in the story. They should matter such that their removal would alter the story. It also means making each character distinguishable by traits other than their race/sexual orientation/gender/body etc. So, if you have a gay character, they should also have other traits that distinguish them from other characters the same way that you would distinguish straight characters from each other. In addition to being better representation, this is better writing.

Finally, it’s okay to show your characters grappling with their own biases.Many writers export the pressure we feel to be perfectly informed, anti-biased creatures onto our characters. For kid lit authors, this pressure is especially acute since our characters serve as role models to children. But, it can be more realistic, not to mention a much better learning experience, to show characters who are genuinely confronting their own bias.

Consider this example from Becky Albertalli’s Simon vs. The Homo Sapiens Agenda. Simon is a closeted gay teenager who has been exchanging anonymous emails with another closeted boy at his school. In this scene, Simon is at a Halloween party with his friends:

“Leah, did you know you have a really Irish face?”

She looks at me. “What?”

“You guys know what I mean. Like an Irish face. Are you Irish?”

“Um, not as far as I know.”

Abby laughs.

“My ancestors are Scottish,” someone says. I look up, and it’s Martin Addison wearing bunny ears.

“Yeah, exactly,” I say as Martin sits beside Abby, close but not too close. “Okay, and it’s so weird, right, because we have all these ancestors from all over the world, and here we are in Garett’s living room, and Martin’s ancestors are from Scotland, and I’m sorry, but Leah’s are totally from Ireland.”

“If you say so.”

“And Nick’s are from Israel.”

“Israel?” says Nick, fingers still sliding all over the frets of the guitar. “They’re from Russia.”

So I guess you learn something new every day, because I really thought Jewish people came from Israel.

“Okay, well, I’m English and German, and Abby’s, you know…” Oh God, I don’t know anything about Africa, and I don’t know if that makes me racist.

“West African. I think.”

“Exactly. I mean, it’s just the randomness of it. How did we all end up here?”

“Slavery, in my case,” Abby says.

And fucking fuck. I need to shut up. I needed to shut up about five minutes ago.

There are several reasons why this scene is so effective.

First, Simon’s biases are explicitly called out, giving Simon—and the reader—a chance to learn from them.Second, the call out isn’t just a random attempt to educate the reader. It is specifically relevant to the point of the book, which is about the ways that our assumptions can be misleading.Third, this moment is a plot clue. Several times in the narrative, Albertalli draws attention to Simon’s blind spots about Black people, because it is relevant to the plot.How’s your anxiety?It’s possible that you’ve read all this and now feel more anxious and less confident than you did coming in. You might read this and think, this sounds like hard work.

Yes, it is.

Writing a book is hard work.

Taking care in your representation may not make anyone’s life easier, but at least you reduce your chances of hurting someone or making someone else’s life harder.

So, roll up your sleeves. This work isn’t easy. But you can do it.

Note from Jane: For writers seeking more guidance on this topic, consider Writing the Other by Nisi Shawl and Cynthia Ward.

March 14, 2024

How and Where to Build Your Literary Community

Photo by Andraz Lazic on Unsplash

Photo by Andraz Lazic on UnsplashToday’s post is by writer Star Wuerdemann.

In 2015, I attended a writing retreat with Natalie Goldberg and had a terrible revelation. As I sat in a room among 75 people diligently scribbling in notebooks, I realized: I had no writer friends.

Now, nine years later, I have a solid writing community that continues to grow and support me. Along the way, I had the opportunity to ask Jane Friedman the most important step to take as an early writer. She said, “Build your website.” Then she laughed and admitted that was the pragmatic side; the other most important thing is to build your literary community.

What is literary community and why do people talk about it all the time?

Literary community is the collective connected through the making of literature: writing, reading, and publishing. Word folks, of all kinds. But more than that, it’s the people who are going to cheer you on when you succeed and encourage you when you fail. Which you will. A writing career is a long game; you need folks by your side.

Building community, while similar to networking, isn’t the same. A literary community will have connections that help your career, but it’s also going to be your support network. Your friends. Author Mary Boone, who has published over 70 books, says, “Community is how you are going to get the writing done.”

But I write alone, you protest. Read the acknowledgements of pretty much any book you’ve appreciated and see just how many people get thanked by the author.

But how does one go about building literary community?

It’s hard to make connections alone at your desk. Thankfully, for those who can’t physically show up for a myriad of reasons, there are many virtual opportunities.

Great, you say. Just where do I show up and find people?

Participate on social media (one place)Many writers still mourn the loss of literary Twitter, and rightfully so, but literary folks remain online. Find the social media platform that works for you, not the one you think you should be on. Jane Friedman says, “It’s okay to play to your strengths… Go where you can sustain the activity, otherwise it’s not going to have any effect.”

Pick one place and build a presence there. Follow authors, bookstores, libraries, editors, publishers, literary agents, literary journals. Interact with the people and places that resonate with you. Build your knowledge about what is happening in the world of writing and publishing.

Have conversations in the newsletter spaceNewsletters are having a moment and are a great way to participate in the literary community. Currently, there are a lot of newsletters on Substack which has the benefit of recommendations to other newsletters. Regardless of the platform, you can easily find out if someone has a newsletter from their website or social media. Find newsletters that interest you. Engage with the author and readers via comments.

One of my favorite newsletters is Pub Cheerleaders, co-written by Rachel León and Amy Giacalone, that promotes literary community with encouragement to writers and reading recommendations through book reviews and author interviews. Speaking of…

Be a cheerleaderShow up at local author events. Tip: It’s okay not to buy the book. Your presence is a contribution, especially if you ask a question.Share other writers’ successes on social media: publications, awards, new jobs/roles, etc.Tell people about an essay or story you loved. Put a book in someone’s hands.Tell writers when you appreciate them. Keep it simple and genuine: “I really enjoyed your piece,” or “I appreciated what you said about story structure.” This can be in-person or online. Join associations near and farThere are many professional organizations and associations dedicated to writing. Look for a writing association in your area to find local connections. There are genre-specific organizations that can offer opportunities for connection as well. (Women’s Fiction Writers Association, Romance Writers of America, National Association of Memoir Writers, Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association, Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, to name a few). Check out The Authors Guild, a national organization that strongly advocates for the rights of writers. They also offer educational opportunities.

Take classesIf you live near a city, there is likely a writing center of some sort. If not, find an online class. If you can, take a multi-week class. Being in a regular group more easily fosters connection than a one-off event. There are many paid opportunities, of course, which run the gamut from wonderful to terrible. Do some research on the teacher and the organization offering a class and be thoughtful in your selection. (See Andromeda Romano-Lax’s recent post on Jane’s blog: Workshopper Beware.) And even if you end up in a not-great workshop, you may still find a great writing friend and/or reader.

Can’t afford a class? Writing is sometimes lamented as a “pay to play” game, and while it may be easier to build your community if you can afford paid events, there are many free opportunities and those that have minimal cost. And remember, many institutions have financial aid available these days.

Attend free (or nearly free) eventsWho are the local authors to your area? What events do they have going on? Look for book festivals and literary fairs in your area. See if there are any drop-in writing groups (good places to look: Shut Up & Write! and Meetup). Check out your local bookstores and local library.

Nothing local? I attend free events from all over. I discover them through newsletters, social media posts, and from my writing community. One of my favorite free online events is run by Miami Book Fair called First Draft: A Virtual Literary Social.

Think outside the critique/workshopOften writers think they want a writing group, meaning a group that gives feedback on each other’s work. Critique groups can be wonderful, but there are many other possibilities for groups, most of which cost nothing.

Write-ins. Here in Washington, I’ve coordinated with a local bookstore to start a drop-in writing group in their event space, advertised through their website. Write-ins can happen in-person or online. Do a brief check in, then set a timer for a prescribed amount of work time during which there is no talking. Check in at the end to see how it went for everyone.Writing-specific book club. Pick a craft book you’ve been wanting to read and partner with a friend or small group to read it and discuss. Or pick a book of your genre and do a close reading. One writing friend and I each read a novel for specific craft elements, and then get together via Zoom to discuss.Accountability groups. I belong to an accountability group hosted by authors Tessa Fontaine and Annie Hartnett. They co-lead Accountability Workshops designed to help writers fulfill their commitment to their own writing. Author Jami Attenberg runs #1000wordsofsummer, an online accountability community who commiserate and cheer each other on in writing, you guessed it, one thousand words a day. NaNoWriMo, a challenge to write 50,000 words of a novel in the month of November, has been happening since 1999. Book Banter Groups. Book Banter groups, often run by libraries or bookstores, are folks gathering to talk about the books they are reading and loving. If there isn’t one happening near you, you could start one.Try the Beta Reader Match UpReady to have your project read and still need to find willing beta readers? Several times a year, founder of the podcast The Sh*t No One Tells You About Writing, Bianca Marais, hosts a Beta Reader Match Up. There is a small fee ($20 at the time of writing this) and a detailed questionnaire that helps connect the right writers with each other.

Go to writers conferencesAttending a conference is a great way to connect with the literary community and meet a broad array of folks in the literary world. The Association of Writers & Writing Programs, aka AWP, hosts the largest conference but there are many others. AWP’s website has a directory of Writing Centers and Conferences: AWP Directory.

If you can’t afford a conference, consider volunteering. I volunteered for my first conference and while I didn’t get to attend as many panels, I got to meet and talk with folks I wouldn’t have as a regular attendee.

Consider graduate studyI would be remiss if I didn’t mention graduate study. Many people build their network by attending an MFA program, either in-person or low-residency. But it’s not a slam-dunk—every cohort is different, and not everyone finds their writing community through their program. Plus it can be very costly. I don’t have an MFA, but I do have a robust literary community.

Final thoughtsThe writing world is small. Smaller than you think! Your actions matter—treat other people with respect and kindness.Seek out peers—find the folks who are at a similar place in their writing career or have a similar dedication to their literary goals.Don’t buy into the scarcity construct—be generous. If you’re lucky enough to find yourself with a seat at the literary table, invite a friend to join. Rebecca Makkai says that it’s not just our job to make room, but to make the table bigger. Have faith there is space.Much like writing and revising, building your literary community is both contrived and organic. You must deliberately seek out opportunities, but then allow the friendships and connections to unfold. Put your energy into people and places that are a good fit for you and your writing goals, and your literary community will thrive.

March 13, 2024

Going After the Widest Audience Possible: Q&A with Award-Winning Author Jami Fairleigh

For years now, the Indie Author Project has made an effort to find the best self-published books in communities across the U.S. and Canada. The project encompasses public libraries, authors, curators, and readers working together to connect library patrons with great self-published work, primarily in fiction.

The Indie Author Project recently named their 2023 national contest winner, Jami Fairleigh, of the King County library system in Washington state. Fairleigh is a biracial, Japanese-American writer, urban planner, and hobby collector from Washington. Her writing has been published by Terror House Magazine, Horror Tree, Defenestration, and Amsterdam Quarterly.

Fairleigh has published three fantasy novels, all part of the Elemental Artist series. The first released in 2021; the most recent released spring 2023.

I recently emailed questions to Fairleigh about her self-publishing journey so far, and she graciously responded.

Jane Friedman: Your series falls into the humorous fantasy subgenre and off the top of my head, I can think of one well-known indie author, Lindsay Buroker, who combines fantasy and humor. But your works seem quite different than hers! Who do you consider your comps on either the traditional or indie side?

Jami Fairleigh: Oh boy. Right now, my expression must be much like the cartoon mouse who just got caught trying to steal a wedge of cheese. You know how people say you should write the book you wish someone would write? The part they don’t say is maybe no one has written it because they have no idea where such a book would live.

I like to describe Oil and Dust as post-apocalyptic fantasy with cozy vibes. Like a magical version of Bob Ross wandering around, making messes, and painting happy little clouds in Hugh Howey’s Wool or Emily St John Mandel’s Station Eleven.

Side note, I adore funny speculative fiction. I’m an avid reader of novels from Terry Pratchett, Douglas Adams, and Jasper Fforde. I didn’t intend for anyone to consider Oil and Dust as humorous fantasy, but it’s possible Amazon’s algorithm and I are amused by the same things.

Tell me about your path to publication for the Elemental Artist series. Was self-publishing the plan all along? How did you learn about the process once you decided to self-publish?

Before Oil and Dust, I’d started and abandoned over fifteen novels. Finishing the story surprised me. I sent it to a printer, then squinted at the box for a week. I didn’t know what to do with it. Luckily, I knew one professional author, so I reached out to Lindsey Sparks to ask why she had chosen to trek the indie route. Her passion for retaining her creative freedom and intellectual property really started me thinking, especially since I knew it would take four books to tell Matthew’s story. However, I still didn’t know if Oil and Dust had legs, so I sent it to Kim Kessler, a freelance developmental editor. The process was fantastic. Even better, it showed me it was possible to publish a book the way I wanted to by hiring a team of freelance professionals.

Going the indie route isn’t easy, and it isn’t cheap. For books as long as mine, developmental edits range from $1,000–$5,000 and copy edits are between $2,000–$3,000. That doesn’t include costs associated with proofreaders, formatting (or formatting software), ISBNs, covers, coaching, and marketing-related expenses.

There is a lot to learn if you go indie. But there are many resources to help you. Listen to podcasts, read books, attend online courses, join writing communities on whatever social media platform you prefer. You won’t have to go it alone—the indie-author community is wonderful and very supportive of other indie authors!

Your series covers look fantastic. Tell me about them.

Aren’t they pretty?? Andrew Brown at Design for Writers did a marvelous job. My initial request was impossible (I asked for a cover in “earth” colors but pretty, with a fantasy vibe, and including people silhouettes but no post-apocalyptic landscapes). Somehow, Andrew made it happen. Because I struggled to figure out good comparison titles (see above) I couldn’t use comp book covers as a starting place. Instead, he sent me to comb through the top selling fantasy and science fiction covers. My task was to understand what I did and didn’t respond to. That helped us get specific. It took a couple of iterations for us to come up with the concept of Oil and Dust. Afterward, the rest of the covers fell into place.

Unlike other indie authors I know, your books are available in hardcover as well as paperback and ebook. Did you release all three editions simultaneously? If so, that’s a meaningful investment upfront! Some authors I know will just do ebook and even wait on doing the paperback.

Yes! I actually released four—there’s also a large-print paperback version—and since I wanted to go wide, that meant separate cover versions for Amazon and IngramSpark too. It increased the cost and complexity, but all four versions of each book sell so I feel like I’m better meeting my reader’s needs.

Any plans for audiobook editions?

Absolutely. I wanted to release each audiobook at the same time as the other versions, but the first narrator I picked had production issues, throwing the timing off. As an audiobook fan myself, having a consistent narrator throughout the series is important to me. Instead of publishing the series with multiple narrators, I decided to wait on the audiobook versions until the series was done. Fingers crossed, I’ll publish the last book of the series this year, so we may move forward with audio narration soon!

The Indie Author of the Year Award is tied to the library community and partly chosen by librarians. Did you learn about this award through the library or elsewhere?

My local library organization (King County Library System) is huge, and I didn’t know how to approach them as a new, unknown indie author. Knock on doors with books in hand? Slide a couple of copies through the return book slot? I decided to do some research instead, and I learned about the Indie Author Project. Plot twist, people at the King County Library System were the ones who picked my book as the winner for the 2022 Indie Author Project regional contest (Washington State).

What has worked well for you in finding new readers for your series?

I chose to go wide from the start, wanting my books available to the largest audience possible. It was lucky I did too; Barnes & Noble picked Oil and Dust as one of their Top Indie Picks before it came out. They also picked it as their Nook Serial read in March 2022 right as the second book in the series came out. Many of my readers came from those two opportunities. It didn’t hurt that Oil and Dust also won 12th place in the Book Bloggers Novel of the Year contest (2022) and the Indie Author Project regional contest. From there, it’s primarily been word-of-mouth recommendations!

March 12, 2024

The Case for Pursuing a Traditional Publishing Deal Without an Agent

Today’s post is by author Amy L. Bernstein.

Securing the services of a literary agent has long been the gold standard for authors pursuing a long and successful career in publishing.

It’s easy to understand why. At the turn of the twentieth century, the so-called “author’s representative” emerged as the figure who would help authors cut a better deal with publishers. Most publishers were unhappy about this since agents who skillfully leveraged their clients’ hot properties forced publishers to shell out more money on better terms.

By mid-century, the agenting game was well established. Legendary agents like Sterling Lord (Jack Kerouac and Doris Kearns Goodwin were among his clients) and Robert Gottlieb (Toni Morrison, Robert Caro) impressed writers with their ability to champion talent, nurture genius, and land lucrative publishing deals. Needless to say, authors couldn’t accomplish half so much on their own behalf. The gatekeepers had won—and were here to stay.

Fast forward to today. Agents still function as gatekeepers, especially to the Big Five publishers and many top-tier smaller publishers, such as Tin House (whose open-reading periods are limited to a few days a year). Breakout debuts by authors like Jessica George (represented by David Higham) and stratospheric careers like Bonnie Garmus’ (repped by Curtis Brown) would not be possible without agents in the mix.

But, dear authors, securing an agent is not the only path to getting happily published (outside of self-publishing).

One big reason to consider other strategies (especially with a first book) is that the agenting business model is showing serious signs of wear-and-tear. Many agents readily admit the industry is in flux.

According to the latest member survey by the Association of American Literary Agents, an overwhelming majority of agents report feeling burned out and are working too much uncompensated overtime. And no wonder, as roughly a fifth of them receive 100 or more queries per week. Many also feel underpaid, given that roughly two-thirds depend in part or entirely on commissions—and making a sale can take months, if not years. (Do you imagine this is an elite group? Roughly 30 percent of American agents earn less than $50,000 annually.)

There’s no need to put all your editorial eggs into this one (turbulent) basket.

Scores of traditional small presses operating professionally and ethically in North America (and the UK, Australia, and elsewhere) are open to reviewing manuscripts year-round or seasonally without charging a fee.

Before getting into nuts and bolts on this, let me anticipate some objections that I know are out there, because the lure of agent-magic is strong:

But going directly to a publisher is less prestigious than going with an agent!

Even if that were objectively true, by the time your book is out in the world, readers have no idea how it got there and aren’t thinking about who reps you. The means justify the ends.

But an agent will fight for a better contract, or a bigger advance, than I’d get by negotiating with the publisher myself!

There may be some truth to this, but the tradeoffs are worth considering. For one thing: you’re getting published! A small advance, or no advance, may be offset by your efforts to successfully market your book when it comes out. Secondly, consider spending a few hundred dollars for an attorney to review your contract. The Authors Guild does this for free, and some states (such as Maryland) offer pro bono legal services to artists.

But a small press can’t market my book effectively!

It’s true that the Big Five publishers have bigger marketing budgets for ads and other forms of publicity. But will they put any of that money behind your book? And even big-name authors are increasingly expected to help market their own books and participate on social media.

The best small presses will submit reviews to the same outlets as the Big Five, from Kirkus to Publishers Weekly, and will engage in guerrilla marketing techniques to get you noticed. The gap in marketing efforts is not as wide as you think—and you’ll be expected to self-market with any publisher.

Now that you’ve begun entertaining the idea that getting into bed with a publisher without an agent isn’t the kiss of death, let’s review how you can make that happen. I’m highlighting three strategies to get you headed in the right direction.

1. Find small pressesWith the emergence of AI-assisted search tools, it is easier than ever to generate lists of “publishers accepting manuscripts without an agent.” (That very search term will yield results.) But AI-generated lists in particular may be incomplete as well as misleading, as they are likely to contain publishers that have switched over to agent-only submissions and/or may be outdated. Vanity presses that require authors to pay-to-play may be on that list, as well. So, beware! AI is not entirely reliable or particularly thorough for this task.

Here are five consistently reliable sources for tracking publishers open to queries (also bound to change over time):

Authors Publish. Run by a handful of dedicated saints who routinely refresh annotated lists of publishers and other literary outlets.The Writer’s Center. An independent home for literary arts, originally in the Washington, D.C., area, but now national in scope.Published to Death. Maintained by author Erica Verillo, who frequently writes about writing.Reedsy. A membership-based resource center for authors and publishing professionals.Duotrope. A subscription-based service for writers and artists that offers an extensive, searchable database of publishers and other literary outlets. Updated frequently.2. Vet the pressesResearch each press or publisher thoroughly before submitting. To that end, here’s a vetting checklist.

Vanity press tip-offs. Scour the publisher’s website to ensure they do not charge authors a substantial reading fee or any fees associated with the publishing process. Some writers don’t mind paying, say, $10 for a reading fee to offset a small press’s labor cost or to defray the expense of using Submittable. That’s up to you. A small reading fee isn’t necessarily a red flag. However, a website that devotes more space to touting the publisher’s services and “packages,” as opposed to highlighting the authors it’s published, is a big red flag. Run away—unless you specifically want this model.

Professionalism. Are the covers of published books consistently professional? Are the genres compatible with yours? Are the titles well displayed on the website? Are the authors professionally profiled? Are book reviews excerpted? Are new releases highlighted? These are all hallmarks of a quality publisher. The website itself should also look updated and professional.

Distribution. Is there at least one distribution partner listed, such as Independent Publishers Group, America West, or Baker & Taylor? If not, seek answers on their distribution outlets.

The Amazon test. Look up a handful of the publisher’s titles on Amazon to ensure the listings appear correct, which formats are listed, how the books are priced, and to ascertain how many reviews have been posted. It’s not the only quality indicator, but it is an important one. Single-digit reviews may suggest weak marketing on the publisher’s part—or an unsuccessful marketing partnership between author and publisher.

Presence. How is the publisher faring on social media? Are they posting regularly on Instagram or Facebook? Do you see signs of real engagement? What are their follower numbers like? Some presses have only a few hundred followers while others have thousands. This could affect their ability to spread the word about your title.

Jane also has tips on evaluating small presses.

Step 3: Submit to a small pressOne advantage of submitting to a small press rather than an agent is that many presses will request the full, complete manuscript—and they will read the whole thing before replying to you. At least this way, you know you’ve gotten a truly fair shake.

That said, some presses prefer that you query them with sample pages, as you would an agent. The key is to pay close attention to their preferences and follow them to the letter.

Because some presses have limited open-submission windows, it’s helpful to join their mailing lists and get notified when those windows open. (I post calendar reminders for just this purpose.)

Finally, note that many small presses are open to literary forms other than book-length work, such as novellas, short stories, or chapbooks. Getting a smaller work published first may open the door for your full-length books later on.

Related: Jane has a thorough list of what to ask a publisher before signing if you don’t have the benefit of an agent.

Keep your eyes on the prizeWhile it can be hard to let go of the dream of landing a prestige agent, kicking off your publishing career with a small press is a great way to get to know the industry, build your author profile, and establish a reputation.

This is a fluid business. You have time to prove yourself in the marketplace before seeking an agent. Indeed, with a few books from small presses under your belt, you may be better positioned to catch an agent’s eye.

And if not?

Keep writing. Keep getting published. And don’t worry about “the one that brung you to the dance.” Your ideal reader, browsing in a bookstore, is looking for your story, not your backstory.

March 7, 2024

3 Elements That Make Historical Romance Successful

Today’s post is by author and book coach Susanne Dunlap.

Saying that romance is a genre the literati love to hate is a hackneyed truism. The preponderance of tropes, if they’re not well handled, can give romance a predictable or formulaic feel. Why, then, are they so enduringly popular? Why do they continue to outsell so many other genres, when the story’s outcome in all cases is a given?

I have come late in life to this popular genre. Yet what began as curiosity is fast developing into an obsession. In the past few months, I have read or listened to approximately fifteen different historical romances. Apart from the sheer pleasure of the experience, I’ve learned a great deal about what makes a story worth reading and why the genre is so appealing. My interest—as a historian and historical novelist—is in romances set in the past. But minus the historical setting, I think most of my observations apply to any good romance.

In a nutshell, here’s what I found.

1. Good historical romances always honor reader expectations.A wise woman, Tabitha Carvan, wrote in her fabulous, entertaining memoir This Is Not a Book about Benedict Cumberbatch, that the pursuit of novelty on the part of today’s authors is a recent goal in fiction. She is speaking in the context of the all-absorbing joys of fan fiction, whose adherents are numerous and surprisingly diverse.

One of the many she interviews is a professor of medieval literature in a Canadian university. This woman points out that “Medieval authors never thought, ‘What can I write that is wholly original and uniquely mine?’ Because nobody would want to read that.”

Readers of historical romance come to the genre not for something completely new, but because they have well-defined expectations of what their reading experience will be like. They want the happy-ever-after. They want the meet cute, the smoldering desire (whether it’s ultimately acted upon or not), the relationship transition through ups and downs. They don’t want the protagonists to die, or the wrong people to end up together. And they want this in a setting and society that has been well-researched and feels believable and real.

They return again and again to their favorite authors and select different types of romances not in spite of the similarities, but because of them. Formulaic? Yes. But authors fail to fulfill these expectations at their peril.

2. Good historical romances build absorbing (and historically accurate) worlds.Selecting pertinent, speaking details is vital to bringing any world to life, historical or otherwise. But choosing these so they enhance the social and romantic aspects of your story is something the best historical romance authors have mastered.

Beyond that, the plots benefit from period-dependent twists on the essential romantic journey of the protagonists. The best HRs don’t overlay modern sensibilities on their protagonists, but really mine the strictures and social constructs of the day to build their characters and to add depth and texture to their predicaments—at the same time as revealing the universality of the experience of falling in love.

An example: Laura Kinsale’s Flowers from the Storm combines the requisite British duke (who happens to be a mathematical genius) with a young Quaker woman, whose father is the duke’s partner in mathematical inquiry. Kinsale has done her historical research thoroughly, from the exact nature of British Quaker beliefs and hierarchical structures and how they would affect the behavior of the female protagonist, to the neuroscience that allows her to accurately portray the young duke’s early stroke. Also part of her world are the machinations of a family who thinks the duke has gone mad and consigns him to a mental hospital—seeking to get their hands on his fortune.

Another more lighthearted example: In Bringing Down the Duke, Evie Dunmore places her feisty heroine believably in the world of the suffragist movement in late-nineteenth-century Britain, as well as makes her a student on a stipend at Lady Margaret College, Oxford. How she maneuvers this impecunious young woman into the path of a powerful duke is quite ingenious (if a little far-fetched). But the plot is believable partly because the heroine faces obstacles and forces of opposition specific to the time, partly because the duke has a political life where he must deal with real issues of the day.

And don’t get me started on the variety and appeal of Georgette Heyer’s historical romances! Even the most hackneyed tropes feel fresh and engaging in her deft literary hands, and her research into British society and political and military history in the long Regency is breathtakingly deep—despite the fact that she was writing at a time when the Internet did not exist.

3. Good historical romances are character driven.Really? I hear readers of literary fiction saying to themselves. But aside from differences in period, setting, and historical circumstances, plot in romance—no matter how cleverly contrived—doesn’t offer enough to keep a reader fully engaged from beginning to end.

Put simply, nowhere is the need to make your reader fall in love with your protagonists more important than in a romance. The two halves of a couple of any gender or sexual orientation must be fully rounded, must be relatable and winning in some way, and must power the story with their inner and outer motivations, hang-ups, desires, misbeliefs, and more.

The protagonists I particularly loved surprised me in good ways, or had me cringing as they made the wrong decisions and got into worse and worse predicaments and seemed less and less likely to end up with their soul mates. Their actions were never arbitrary, but seamlessly embedded in who they were in their time and place.

How do historical romance authors achieve this? Primarily by ensuring that the emotion is on the page. But they also make sure that protagonists have goals they cannot easily achieve, and that both internal and external motivations are clear and logical. Additionally, any complications and plot twists must not only affect the protagonists in a believable way, but push them along their inexorable arcs.

Bottom line, don’t judge a book by its genre.My final words of wisdom: read (and write) what you love.

A book that demands intellectual engagement can be immensely pleasurable and rewarding to read. But something that simply transports us to another time and place, where there are no matters of life and death and all works out for the best in the best of all possible worlds, can be just as much so.

And if you approach a book with a writer’s eye, even the most pleasurable, light reading can teach you something that enriches your own storytelling craft.

March 6, 2024

Emotional Intimacy Between Characters Isn’t Just for Romance Novels

Photo by Viktor Talashuk on Unsplash

Photo by Viktor Talashuk on UnsplashToday’s post is by romance author and book coach Trisha Jenn Loehr (@trishajennreads).

When writers think of writing intimate scenes, our minds often go straight to the bedroom—to romantic or sexual intimacy. But that puts an unnecessary constraint on what intimacy is when intimacy can be physical or emotional, platonic or romantic. At its simplest, intimacy in a relationship is the state of closeness or deep familiarity. Regardless of what their relationship is, emotional intimacy between characters often begins long before they get physically intimate (if they ever do) and some level of emotional intimacy belongs in every close relationship.

No matter what you’re writing (even if it’s not romance), emotional intimacy between characters is important to creating authentic relationships and creates the backbone for deep relationships between characters and readers.

Emotional intimacy is a bond based on mutual understanding, vulnerability, and trust.Yes, these are necessary qualities of successful romantic relationships and make those steamy scenes in my favorite romance novels even more fun to read. Emotional intimacy can level up scenes with physical intimacy to the place where the physical interaction feels more profound and more impactful for both the character and the reader.

But pause and consider how important mutual understanding, vulnerability, and trust are to other relationships. A friendship or a familial relationship that lacks any of these things will be either flat and boring or will be full of tension and conflict caused by misunderstanding.

Think about your protagonist, regardless of whether they are romantically involved with anyone. They are likely to have close relationships with at least one, if not multiple, other characters.

A character will have varying levels of closeness (i.e., emotional intimacy) in relationships with:

friendscoworkersparentssiblingscousinsroommatesmentorsand yes, their partner or love interest.There can even be moments of emotional intimacy between acquaintances or strangers who have a shared experience or mutual understanding.

These various levels of emotional intimacy allow the reader to get to know your protagonist and the other characters they interact with. Showing emotional intimacy between characters is a way to show various aspects of who that character is—what they like or don’t like, what they believe, and who they share their thoughts and hopes and dreams and fears with.

Moments of emotional intimacy enable readers to care about characters by seeing them be cared for and care for others. Writing moments of emotional intimacy (or the lack of it) between characters helps your readers assess the dynamics between the characters, their roles in the story, and the arc of change within the relationship or caused by their relationship.

Emotional intimacy is often shown in the small things, the quiet moments, and even moments unspoken.In moments of emotional intimacy, characters are increasingly comfortable together. They open up to one another and communicate their truths, fears, and insecurities. They support each other without needing to be asked, or they validate the other person’s feelings.

Emotional intimacy can be shown through:

remembering someone’s preferencesshared or inside jokesunderstanding non-verbal cueshonest conversations about hopes, fears, dreams, traumaspositive physical reactions to another character that shows a feeling of safety or comfortEmotional intimacy between friends/love interests: In Ali Hazelwood’s contemporary YA romance Check & Mate, one character anonymously sends a hotel room service order of chicken soup and three Snickers bars to another character who is having a stressful day. The recipient knows immediately who sent it (but tries to tell herself she’s wrong). This moment mirrors a scene earlier in the novel when she made him chicken soup while sick and commented on how she was charging him for the supplies she bought, including the “emotional support Snickers bar” that she purchased for herself.

Emotional intimacy between siblings: In Brenna Bailey’s queer small town romance Wishing on Winter, after retiring from his life as a rockstar, a man moves in with his sister to help her out. He goes grocery shopping to fill her fridge and buys all her favorite foods that he can think of, most notably the cookies with the jam in the middle.

Emotional intimacy between an acquaintance/mentor and mentee: In Julie Murphy’s YA novel Dumplin’, a teenage girl expresses her grief at the death of her late aunt. In losing her beloved aunt, she also lost her compass. Her friend suggests that maybe her aunt was only supposed to be her compass until she was able to be her own compass. This interaction spurs the teen girl to choose her own destiny, and leads to the friend becoming a mentor character later in the novel.