Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 37

March 5, 2024

Workshopper Beware: Navigating the Risky Waters of Writing Classes and Retreats

Today’s post is by author and book coach Andromeda Romano-Lax (@romanolax).

Several years ago, I attended a writing workshop held in a beautiful locale, with sumptuous food and dreamy scenery. Only the teaching was bad. And not just bad. It was the most disorganized and downright toxic event I’d experienced in twenty-plus years.

Before attending this event, I thought I’d seen it all: middle-aged writers leaving in tears after being told they should give up on their projects; women being taken to task for their parenting, marriages, or some other personal choice or foible; racist micro-aggressions; genre prejudices; the withholding of attention except for teachers’ pets. There are so many ways for a workshop to go wrong, even when no one is left offended or devastated.

For a time, I attended private workshops or retreats when I jumped genres and was hoping to accelerate the learning process, with some networking on the side. That was the case when I signed up for a screenwriting workshop with a notable Hollywood writer at a high-prestige conference. He cancelled at the last minute due to delays on a movie set, to be replaced by another man who had made one low-budget, poorly rated sci-fi film about fifteen years earlier, and nothing since.

For part of each afternoon, “Nut Spitter,” as I came to privately call him, leaned back in a comfy armchair, eyes closed, one hand on his ample belly as he fed himself pieces of nuts that he would spray outward, in flecks and fragments, as he monologued.

By the second day, I realized I should sit further back in the half-circle.

By the third day, I realized I wasn’t going to learn much about screenwriting.

We never ended up doing any kind of workshopping in that particular “workshop.” We didn’t read screenplays, discuss structure, or do any writing exercises. Over several days, we mostly heard our teacher’s opinions about one-sentence loglines, a subject easily covered in one hour. I let the conference organizers know what was happening, but I didn’t request a refund because I feared offending them. I had a new novel coming out soon, and I didn’t want to burn any bridges. On top of that, tuition had been just part of my expenses. Lodging and airfare cost even more. There was no getting that money back.

Heeding the siren call of a Big Name, as I’ve done at least three other times, doesn’t always lead to disappointment. At one workshop led by one of my all-time heroes, I had a great time. But then again, I wasn’t the person in that same workshop who’d just written a cancer memoir only to be told by the author-teacher (who didn’t write traditional memoir or know anything about marketing), that her topic had been “done” and she’d never see her story in print. (Needless to say, dozens of cancer memoirs have been published since.)

But the big reason I’ve attended workshops, even after I co-founded a nonprofit literary center and found work as a fiction mentor in a graduate creative writing program, was to improve my own teaching. There’s nothing like learning what to do—and what not to do—than by watching another instructor stagger across the minefield that is workshopping.

Because it is a minefield. A group of strangers, who may or may not be your ideal future readers (or sometimes only the instructor herself), passes judgment on the fate of your project, and possibly your entire writing future, following a quick reading of ten or twenty pages. (Or none!)

Hypothetical Workshop Leader may not recognize that pointing out the good helps writers as much as pointing out the bad. The leader may not have done enough teaching or editing to realize that most writers, even experienced ones, often don’t start in the right place in early drafts. A manuscript can appear much stronger—or weaker—once you’ve gotten past the first fifty pages, which is why a short-term class focused on limited pages may be the wrong place for seeking strong judgments about a book-length work. Luckily, in the last decade, many writing centers and private teachers have begun offering year-long writing classes that allow for discussion of full manuscripts.

Of course, sometimes you’re grateful a workshop doesn’t last very long. At the most recent I attended, the one held in the dreamy locale, I chose not to bring home a souvenir I’d bought. Every time I looked at the handwoven table runner, I’d think of the young woman who was pressured into verbally reenacting an exceptionally traumatic episode not shared in distributed pages. Or the several other women who were selectively bullied, ridiculed, or ignored. I worried most for the vulnerable writers who didn’t seem to realize this sort of workshop behavior, while not exactly unique, also wasn’t the norm. Frankly, I wanted to forget all of it.

Amazon • Bookshop

Amazon • BookshopBut much as I tried, I couldn’t. Six months later, I had the idea to use a toxic memoir workshop as the setting for a suspense novel. Called The Deepest Lake, it will be published in May. In the process of writing it, I’ve heard from other writers who have their own workshop horror stories, which is both validating and worrying in equal measure.

That’s not where the story ends. Because as a teacher and book coach, I’ve continued to ponder the damage that workshops—possibly even my own—do at times. Writing groups have their own issues, but at least the members know each other well. Friend Jill may tend to give spot-on advice, but you know that Joe will never accept an “unlikeable” narrator, Judy thinks one must always show and never tell, and Jeri has made it clear she only reads science fiction.

In more democratic, long-term groups, writers can make their own rules, like doing away with the outmoded “gag rule” that says that writers being workshopped shouldn’t speak, even to answer simple questions. Writing groups and longer workshops can allow for flexibility, prioritizing the writer’s needs with a particular draft. Maybe Jill is ready for a line-by-line analysis with strict attention to description and dialogue tags. Maybe Joe’s draft is tender and he doesn’t need prescriptions, only general feedback on whether the premise has energy. Maybe Judy doesn’t care if some readers don’t know what a “pavlova” is because her ideal readers are Aussie dessert experts. Maybe Jeri wants to hear more from people who don’t read science fiction because she’s hoping her interstellar novel will reach an entirely new audience.

But if writing groups can follow those more democratic and sensible rules, why can’t workshops? The answer is: with modifications, they can.

Last year, I learned about a workshop method called The Critical Response Process. Invented by choreographer Liz Lerman in 1990, CRP is a four-step method for giving and receiving feedback in a way that centers the artist and keeps discussions from going off the rails. Recently, as part of an MFA alumni group, I took a seminar on the method and practiced using it. In my next private online workshop, I gave it a try. The constructive atmosphere and positive student evaluations astounded me.

Decades of attending and teaching workshops have given me lots of stories, either vexing or funny. But only recently have I been brought to a belated epiphany. We don’t have to workshop the way we used to. If we do take a chance and sign up for a high-stakes retreat, we should arrive forearmed, aware not only of our right to walk away from manipulative ploys—like being asked to pay more money once you’ve arrived, only one gambit I’ve observed—or downright abusive methods. As students or as teachers, we should also be aware of newer methods, theories, and debates, like the ones outlined in Craft in the Real World by Matthew Salesses and The Anti-Racist Writing Workshop by Felicia Rose Chavez, both of which demystify workshops and make important arguments about the non-neutral nature of “craft.”

Sometimes, for some people, workshops are magical. But writers who attend them should be prepared for all of it—the magic and the toxic and the just-plain-weird. It doesn’t hurt, in-between those fun moments making friends or getting a great massage, to remember that you are the authority of your story.

Learn from others, but hold onto your power. That’s a lesson we writers often need to re-learn very step along the path to publication.

March 4, 2024

Substack Is Both Great and Terrible for Authors

I have been trying to convince writers of the value of a consistent email newsletter for more than a decade. Recently I dug up a 2014 presentation I gave at the James River Writers Conference, where the first slide says, “Email is not dead.” After that slide, I quoted novelist Dana Stabenow, who gave an inspirational talk where she couldn’t resist offering a practical tip at the end:

“Remember this if you remember nothing else from my speech tonight. It turns out that an active buy link in a newsletter targeted at people who really want to get it is the most effective means of selling your book.”

She’s 100% right. But that message is ironically harder than ever to get across in the era of Substack.

Substack launched in 2017 and in its early days, I saw it as a fantastic, easy-to-use platform for starting a paid newsletter. At that time, launching a paid newsletter was not straight forward. I know because I started mine (The Hot Sheet) in 2015. My tech stack was Mailchimp + ChargeBee + WordPress, which worked pretty well and cost a fixed fee of roughly $100 per month. The Hot Sheet was profitable from day one, mainly because I already had a blog and free newsletter reaching 20,000 people. Growth for The Hot Sheet has been steady but slow, with about 2,500 paid subscribers after eight years of continuous operation. It now earns six figures annually.

But if you told me I had to choose between keeping my free newsletter (now at ~30,000 subscribers) or the paid one, I’d keep the free one. There are a few reasons for that, but the biggest by far is that my free newsletter is a better marketing and promotion vehicle than the paid one. The free newsletters make people aware of a million other things I do that earn me (more) money. And the visibility it lends me has been superlative and ongoing since 2009. I feel confident that my free newsletter will not stop publishing until I retire from writing and publishing. Even then, I might still continue it. I actually enjoy doing it, which is part of the secret to most successful and sustainable newsletters.

Substack can confuse authors about the most important purpose of the email newsletterNewsletters remain the best way to directly reach your readers and biggest fans. It helps you be less dependent on publishers, agents, retailers, bookstores, or anyone else to reach readers who enjoy your work. Your email newsletter ideally starts and grows as you become visible to readers and the larger world—because you’re publishing articles and essays, because you’re publishing books, because you’re speaking at events, because you’re active on social media, because people are recommending your work.

If you start an email newsletter to stay in touch with people who’ve read your work, then it’s no great mystery what goes in the newsletter. Generally, it’s news about your work! It offers updates about what you’re working on or anything new you’ve published, listings of events or opportunities to interact, behind the scenes of your writing life, notes about other authors you read or enjoy, and so on. Children’s author Meg Medina has a newsletter like this, as do many published authors.

If you’re an unpublished, unknown writer who has no work available, and no existing readership, could you benefit from and grow a newsletter—on Substack or elsewhere? Absolutely. If that describes you, it likely puts you in the role of “creator.” You have to figure out what you’re going to write, curate, recommend, or offer that’s of value to someone who is a total stranger to you (that is: someone who is not a reader and not an existing fan). In this sense, deciding to launch a Substack is no different than deciding you’ll blog, start a podcast, begin a YouTube channel, or make TikTok videos. You’re going to spend some serious time developing original content to attract an audience.

Some writers do this because they think it will build them a platform that will land a book deal. Maybe it will, maybe it won’t. But I can guarantee one thing: starting a Substack that you charge for can easily hamper your platform-building efforts.

Some writers might like the idea of writing and publishing primarily in newsletter form, just like I do. If that describes you, go for it! Substack is a great tool for that, especially if you know you’ll want to monetize the effort at some point in the future. But you need to know what you’re in for.

Substack is part of the creator economySubstack wants you to be a creator because this is their business model. They’re not like a Mailchimp or ConvertKit or email marketing service provider that charges you a fee for service. They offer you their tools for free, then they make money if you start charging for your newsletter. So every step of the way, Substack will put this idea in your head that you should charge. Or that people will or should or can support your newsletter efforts monetarily. This is not a bad thing if you are indeed pursuing newsletterdom as a creator and you are trying to build an audience who will pay for your work in newsletter form. But…

Getting readers to pay for a newsletter is like playing in master modeUnknown and unpublished writers will have a hard time getting total strangers to either sign up or pay for their newsletter. Even Substack the company counsels its users to build a solid free offering and not paywall everything. Some of the most successful paid newsletters make a majority of their content available for free—and sometimes the most popular content is always free. That may seem counterintuitive—shouldn’t the popular content be behind the paywall? No, it’s the popular content that gets read and shared by people who don’t pay, but might decide to transition to paid once they’re exposed to your writing or value. The people who can be convinced to pay typically want the more granular thing you offer, the more obsessive thing you offer, the more exclusive part of your content. Consider a demand curve like this:

There will always be more freeloaders than people willing to pay. The percentage of people who pay is typically around 1–5% of the people who read you for free.

Where things get complicated: Substack has a built-in social network and recommendation engineToday Substack has become immensely popular because when you write and publish on their platform, it’s more visible and discoverable than your average email newsletter. There’s a web-based version that people can comment on, share, and recommend. Substack also encourages each newsletter writer to recommend other newsletters as part of their sign-up process and profile. Sometimes I refer to Substack as the new, more connected era of blogging—it operates like a blogging tool that collects email addresses and delivers emails for you. But there’s more.

In April 2023, Substack launched Notes, which is a Twitter-like interface laid on top of the whole enterprise. So now you have a community of readers and writers visible to each other and commenting and recommending each other’s Substacks. And based on the reports I see and hear from numerous users, this social network, combined with the built-in recommendations system, leads to faster growth in newsletter subscribers.

If you’re able to achieve this boost, there’s little downside in taking advantage of the network effects if you don’t already have and maintain a newsletter elsewhere. (And yes, plenty of people have switched over to Substack from Mailchimp or similar, both to avoid the fees associated with email marketing providers and to get the added growth and to create paid offerings.)

I’ve also seen writers jump on the Substack bandwagon because they feel platform-building pressure or they don’t want to get “left behind.” And it’s true: there is a very active writing and publishing community on Substack. If you look at my Substack profile, you can see that I subscribe to and read more than 100 publications there. Lots of literary agents, editors, marketers, publicists and well-known journalists use Substack.

But here’s what concerns me: the value of a straightforward, free email newsletter is getting overshadowedWriters who are unpublished or new to platform building will ask me: I can’t gain traction on my Substack. How do I get new readers?

Well, it’s no different than getting people to read your blog, subscribe to your podcast or YouTube channel, or follow you on social media. You have to be providing value or entertainment or something that’s desirable to your target reader. (You also must have some idea of your target readership in the first place!) You need some copywriting skills. You need to write compelling headlines or subject lines. You have to develop a good sense of what gets shared or talked about in online spaces. And obviously this is quite different than writing a novel or a memoir.

Moreover, Substack as a platform-building tool is really best for nonfiction writers. If you’re trying to publish your fiction on Substack, good luck with that.

Writing and publishing on Substack isn’t going to magically lead to a readership without a content strategy behind it. Alternatively, you’ll need built-in platform or visibility that will attract people your way (e.g., George Saunders).

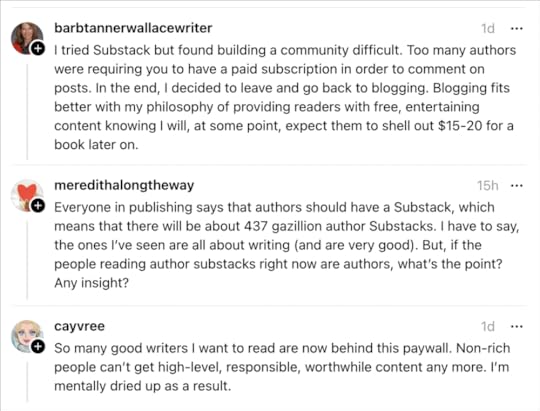

In the long run, I worry that many authors will see the fuss and hype around Substack and decide that email newsletters are overrated. Or if they can’t achieve growth on Substack, they may decide once again that “email is dead.” And the rest of the writers who plow ahead might unfortunately burn out. See these comments I received recently when discussing Substack:

I am not against Substack1, but as usual, I am against the hype surrounding it. By all means experiment and give it a try if it gives you creative energy, and take advantage of its network effects while you can. But you’re not going to miss out if you decide it’s not right for you.

As you become known as an author, or when you publish your first book, I hope you’ll consider establishing a standard and free email newsletter that’s meant to primarily serve your readers, to keep them informed about your work. Because as Stabenow said, those are the people who are most likely to buy your next book. Cherish them.

I am well aware of the controversy surrounding Substack, and some writers have left the platform as a result. Each writer has to make their own personal decision in this matter. There is no exact equivalent to Substack if you want the social layer and recommendation system (and it’s hard to beat the fact it’s free), but there are alternative tools for starting a paid newsletter, such as Beehiiv and Ghost. ︎

︎

February 28, 2024

Tropes: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Photo by Daisa TJ

Photo by Daisa TJToday’s post is by romance author and book coach Trisha Jenn Loehr (@trishajennreads).

Tropes are a staple of genre fiction. Some folks love to hate them; they even use “tropey” as a derogatory term.

And yet, writers still use them.

And many readers still celebrate them.

Why?

Because tropes, simply put, are things like themes, plot devices, archetypes, and structures that pop up regularly in stories, especially stories within distinct genre categories. Tropes have developed from storytelling patterns appreciated by readers and writers alike.

If you think about it, you likely have favorite tropes that draw you in, whether consciously (e.g., I’m looking for a fabulous enemies-to-lovers romance with an only-one-bed scene) or subconsciously (e.g., realizing that half the books on your shelf feature a protagonist battling against—and ultimately overcoming—an evil empire of some kind).

The Good: Tropes are tools for readers and for writers.Tropes help readers find stories with elements they already know they like.

Readers, especially those who read genre fiction like romance, mystery, thriller, science fiction and fantasy, have specific tastes around the types of stories they enjoy. When they read back cover copy that indicates “this book has your favorite elements,” they’re more likely to take that book home and read it.

Just as we gravitate toward friend groups with similar interests or favorite foods for meals and snacks, readers gravitate toward stories they already know they will likely enjoy. If I’m trying out a new restaurant, I’ll often scan the menu for a variation on staples like the club sandwich or fish and chips because I know I usually like those dishes and it’s fun to see how different chefs make their version of a common dish. The same goes for stories. Tropes allow readers to experiment with new authors and new books in a safe way because they are already familiar with some elements of the story.

Tropes are a grab bag of elements for writers to play with. Whether we’re looking at overarching structural tropes in fantasy and sci-fi novels or relationship elements in romance novels, tropes give us a wide array of components to experiment with as we write.

Think about it, how many books or movies can you name that feature one (or more) of the following common tropes?

A grumpy or quirky detectiveA “chosen one” who must save the worldA love triangleAn evil leader who wants all power for themselvesA damsel in distressA fake relationshipA reluctant heroAn ensemble of unlikely companionsYou can probably come up with a long list, right?

After all, as Mark Twain wrote in The Autobiography of Mark Twain, “There is no such thing as a new idea. It is impossible. We simply take a lot of old ideas and put them into a sort of mental kaleidoscope. We give them a turn and they make new and curious combinations. We keep on turning and making new combinations indefinitely; but they are the same old pieces of colored glass that have been in use through all the ages.”

And that my friends, is the goal—to take ideas and story components and put them together in new and interesting ways. The key to using tropes well is to tweak them so that, while still familiar enough to be recognizable and draw a reader in, you’ve used the tropes in unique, memorable ways rather than simply repeating the same thing over and over.

The Bad: Tropes used poorly or in boring, predictable ways annoy readers.When writers don’t do the work to use tropes in surprising ways, readers get bored. Overused tropes plopped into a story without something transforming or fresh leads to predictable stories. That’s when readers toss out the insult of “lazy writing.”

An enemies-to-lovers romance (forgive me for using this example again, but it’s one of my absolute favorites) without a compelling, layered reason for being enemies feels forced. The surface reason for being enemies is usually not the real reason why the two characters dislike one another (even if they think it is). The layers of emotional depth a writer can build using backstory and story-present, bit by bit, to make an enemies-to-lovers trope feel fresh, is what makes it an intriguing take on the trope rather than unnecessary conflict for the sake of keywords.

When a trope gets used in a way that’s too similar to another work, it feels to many readers like the same story with new character names. This is often how people describe Hallmark movies or Nicholas Sparks novels. But many, many, movie-goers and readers love them. Why? Because they recognize the storytelling patterns and elements that they like and are comforted by knowing how the story will progress.

Readers don’t want to read the exact same story over and over again. But they do want to read similar stories that use loved elements in new ways. Tropes used poorly run the risk of becoming clichés.

The Ugly: Writers can stuff too many tropes into their story.Tropes are often confused with clichés. Tropes, in and of themselves, are not so bad, as we’ve already discussed. Clichés and stereotypes, however, are ideas or patterns that are no longer effective storytelling or enjoyable for readers because they are so overused in the same boring way or are no longer acceptable to readers that they become a turn-off rather than a turn-on.

Trope stuffing happens when a writer throws every trope they can think of into a novel in an effort to try to appeal to all readers or all keyword searches at a retailer like Amazon. You’d never toss random spices from your spice rack onto your food with no intentionality for what flavors go together and what quantity works. A few tropes used thoughtfully and intentionally will create a much more interesting and cohesive story than one in which every possible trope is used.

Clichés and stereotypes can be boring and, almost as often, offensive to readers. We are realizing that a lot of stories we’ve loved are problematic and some tropes that used to be common have become unacceptable: The damsel in distress who needs the big suave man to come and save her because she’s incapable of helping herself. The evil villain with no backstory and no depth. That token diverse side character who is immediately killed off or sent on a pointless side quest. The all-white, all-male, all-straight ensemble cast of heroes or anti-heroes.

Being intentional about writing the world we live in—and the world we want to live in—is an important consideration when choosing tropes.

The challengeTake a look at your current work-in-progress. See if you can identify the tropes you’re using. Make a list in one column and then, in the next column, brainstorm ideas for how you can play with those tropes in new, interesting, distinct ways.

If you’re stuck, grab a few of your favorite books from your shelf and think about the tropes they use. What do you enjoy about those tropes? And in what ways did those authors that you enjoyed reading, rework those tropes into something fresh?

Tropes are tools for our art. Just as a painter uses brushes and watercolors to blend and create, we as writers can experiment with, blend and bend, and upend tropes to make our stories both familiar and refreshing for our readers.

February 27, 2024

Author Platform Follows the Work

Photo by John Schnobrich on Unsplash

Photo by John Schnobrich on UnsplashToday’s post is by writer Mirella Stoyanova (@mirellastoyanova).

Note from Jane: Mirella’s original title for her piece was “I’d Rather Be Writing.” I retitled it to make a different point, one that I deeply hope more writers truly grasp and understand, for their sanity and success. I’m grateful to Mirella for her graciousness in letting me retitle.

I have always wanted to sit at the popular kids’ table.

To know that I am enough, as is, is possibly one of the most difficult lessons I have ever had to learn. It’s what led me to become a therapist, and like all good life lessons, it’s one I know I will revisit throughout my lifetime, albeit in new ways.

So it should come as no surprise that my entry into the field of writing might entail a similar kind of learning curve. I can’t help but be lured in by well-intentioned writing advice and industry professionals (some of whom I embarrassingly relegate to near celebrity status) who dole it out.

Last spring, I completed an early draft of my memoir and humbly discovered soon after that fame and fortune would not immediately (or perhaps ever) follow should I decide to pursue the long and winding path to traditional publication.

I was pregnant and due any day, so I took the most reasonable suggestion I was offered: to set my manuscript aside for a nondescript period of time. I then diverted my attention to what other writing-related work I could do as I recovered from childbirth.

Up until that point, I had read and followed the very sensible advice dispensed in two books—Before and After the Book Deal by Courtney Maum and The Business of Being a Writer by Jane Friedman—so I had a few ideas about how I wanted to direct my energy. I was going to continue to learn about platform building. I was also going to figure out what it meant to be a good literary citizen and, I hoped, be one.

I was noble in my pursuit those first few months of my son’s life, even if slightly ineffectual. I read books and attended workshops on related topics, tested out a writing-focused social media page (and failed miserably), and even lugged my husband and our newborn son to an event at our local library where I bought a few 99-cent board books (which was lovely, but ultimately unhelpful).

Being relatively new to the literary world meant that I had only vague notions of how to go about these writing-adjacent activities. I knew little in practice about what it meant for me to build an author platform. With limited time, energy, and no real writing community, I found myself at a loss for how to direct my efforts.

Around this time, I stumbled onto a few popular writing-related resources on social media and while previously I had only ever used my account to follow authors I admired, the lure of indispensable writing advice and built-in community called me right in. I began to engage (as you do) and was delighted to find myself interacting with industry experts of all stripes.

And I’ll be honest, I learned a lot. I studied and honed my craft in virtual workshops led by industry professionals so knowledgeable and passionate about storytelling that I had no doubt as to the quality of their instruction. I also engaged in meaningful conversations with other writers about the industry at large—the challenges it faces, as well as practical solutions for navigating the publishing landscape as an emerging writer.

Then something funny happened. Sort of.

In finding the platform-building content I was so desperately looking for, I somewhat, if only temporarily, lost myself.

It’s a compelling idea for any emerging or otherwise distraction-prone writer—that there is something other than a strong grasp of craft and sheer will that one needs to have to achieve literary success. Like the notion that I must wear the latest trendy clothes or that my hair must be Pantene straight to sit with the popular kids.

I mistakenly believed that to get agented and eventually published that I would need to build an author platform on social media—and that I needed to do it yesterday. Never mind the fact that I am not a published writer nor do I have any literary background or experience.

And I, like any other human being who came of age in today’s quick-fix society, bought right into the hype.

Now I’m going to give myself a little bit of grace here. While ordinarily I consider myself to be highly focused, I gave birth to a very cute, (now) months-old distraction that might have you believe otherwise.

Still, for a while there, things got pretty unhinged.

I fretted over photos, worried about how I would out myself as a writer to friends and family, and prepared—mind, body, and soul—to sell myself out to the creator economy. It was easy to do, after all, much easier than sitting my butt down in a chair and revising my manuscript.

My desire to be liked by these individuals—agents who I may one day query, writing professionals who kindly respond when you comment on their social media pages and offer no shortage of both free and paid opportunities to connect and be a part of their literary communities—almost entirely eclipsed any and all other perspectives on my writing career, including the most important one I need to stay grounded in moving forward. My own.

While author platform is important, I think new writers are particularly vulnerable to getting the order of operations wrong.

The author platform follows the work. Not the other way around.

Notably, none of the authors I admire had particularly robust social media platforms before they became successful.

Why should I, a therapist from Seattle, with my a la carte MFA?

I did post about my writing, eventually, and although (mercifully) none of my friends or family unfollowed me, I later archived the platform-specific content that I wrote up, despite it performing relatively well.

I realize now that my author platform follows from who I am, not how I look on social media—and that it builds from my writing and from my work and membership to various legitimate communities that I show up to and for in very real ways both on and offline—like the social work community here in Seattle and the community of transracial adoptees of which I am a part, here in the Pacific Northwest.

And while I appreciate the advice of well-meaning publication professionals and their effort to build a platform for their businesses (which are not based in the work of writing but rather the work of marketing), as a writer myself, as memoirist of color, and as someone who writes about personal trauma I have experienced, I have a lot to lose if I blindly follow anyone’s half-baked opinion about how to build an author platform, even if it is an expert one.

So I’m excusing myself from the popular kids’ table for now. I’m no longer interested in fitting in at the cost of alienating myself from the very real connections that I have made and choose to maintain over social media.

I know I am enough, as is, and that my people will find me, eventually. But until then, the truth is, I’d rather be writing.

February 22, 2024

Scene, Summary, Postcard: 3 Types of Scenes in Commercial, Upmarket, and Literary Fiction

Photo by freestocks on Unsplash

Photo by freestocks on UnsplashToday’s post is by author, book coach, and developmental editor Lidija Hilje.

It’s often said that scenes are the fundamental building blocks of a story—the smallest units that propel the narrative forward. But what precisely constitutes a scene, and what types of scenes are there?

Typically, when we refer to a scene, we’re talking about it in a classic, strict sense: as a story-relevant event that unfolds in real time. A classic scene contains the smallest piece of the plot and a movement in character arc in response to that plot. The reader follows the protagonist as they move through the scene in real time, and this moment-to-moment development is shown through action, dialogue, description, and internal monologue. Ultimately, the events of the scene challenge the protagonist, leading to a revelation, reaction, or decision that affects the story.

However, especially in literary and upmarket fiction, authors often use other types of scenes. These scenes might not adhere to a strict timeframe and can span months or even years; they might encapsulate the development of a relationship or a character’s personality. This is a summary scene.

Some scenes, on the other hand, don’t necessarily revolve around the protagonist learning something new or making a pivotal decision. Instead, they advance the story by providing deeper insights into the characters and moving the story deeper. This is a postcard scene.

Each type serves a unique purpose. Skilled storytellers use and balance different types of scenes within a single narrative.

Let’s break down each scene type and the best storytelling practices related to them.

Classic sceneA classic scene delves into a story-relevant event, capturing it in real-time and in a specific location. A story-relevant event is a plot point that has the power to push the character’s journey in a positive or negative direction, bringing them closer to or further from their story goal.

As the smallest unit of the story, a scene contains all the essential elements that the overall story should possess: an inciting incident that disrupts the protagonist’s status quo; complications that further challenge the protagonist; a crisis that forces the protagonist to deal with the challenges they’re facing; the climax, when the protagonist finally makes a decision, or reaches a conclusion, or takes a specific course of action; and a resolution which shows us the aftermath of the protagonist’s choice.

The scene moves the story forward by affecting the protagonist: they are faced with new information that has them discovering, unearthing, concluding, deciding.

Let’s say we have a protagonist, June, walking through the park and finding a puppy. The reader follows June closely, and the action unfolds the way it does in real life.

The following is not a full scene, but indicates briefly how a classic scene behaves.

June heard a whimper. It was so quiet she almost missed it. But then, there it was again, clearer, sadder. June neared the bush and knelt. The whimpering stopped. June pushed the branches aside, and two of the most beautiful eyes June had ever seen stared back at her.

“Why, hello there,” June said to the puppy, reaching to scratch its black-and-white head.

The puppy recoiled, and June’s heart twitched. Poor baby, who knew what it’d been through.“It’s okay, little one, I won’t hurt you.”

The puppy couldn’t have been more than a few weeks old. It stared at June with its big, black, starry eyes (…)

Notice how contained in terms of time and space this scene is. Let’s say we continued writing this scene, with a clear and externalized resolution: June decides to keep the dog, despite her landlord not allowing pets. A reader can see how this is going to complicate June’s life—and the story’s plot—going forward.

Summary sceneA summary scene doesn’t unfold in a contained time and space. Instead, it condenses events spanning over a longer period of time. It might convey a specific concept, such as character development, the evolution of a relationship, or the passage of time. The story can meander across various settings and times, spanning years or even decades.

The challenge here is obvious. Even when describing events in a linear fashion, it’s easy to slip into the monotonous pattern of “this happened, then this happened, then this happened.” In essence, the information can come across as dry and disjointed, resembling a list of events rather than a cohesive narrative.

To preserve the storytelling feel even while we are conveying events scattered across a longer period of time, it is important to maintain a through-line: the summary needs to focus on a certain idea. Like a classic scene has an arc, a summary has a progression and a clear takeaway, with the ability to move the story forward.

Here’s an example of a summary with June and her dog.

Over the next few months, June did all she could to hide the puppy from her neighbors, and especially the landlord. Every morning she got up and hid the dog—she named her Dolores because the puppy had the big sad eyes of a flamenco dancer—under her coat or in her gym bag, and took her to the nearby park. She made sure Dolores ran as much as she could, and would throw sticks for her to fetch, and chase her down the park to exhaust some of her tireless puppy energy.

Before she went to work, June would put out enough food and water to get Dolores through the day. She hoped, while she worked, that Dolores was behaving herself, but when she would come home, she would see proof of Dolores’s mischief—the curtains pulled, with teeth holes in them, June’s shoes bitten and chewed, the potted plants displaced from the windowsill. Dolores would squeal with joy for seeing her, and June would have to cough loudly to hide the sound until she closed the door behind her.

But as Dolores grew, it became more difficult to hide her under a coat. She became more restless during the day (…)

The through-line here is that June is hiding the dog and she won’t be able to hide Dolores forever.

The other key to writing a good summary is to give as much precise imagery as possible. The more we can see the events unfolding, the easier it becomes to maintain that sense that we are inside the story. In my example, I compared Dolores’s eyes to those of a flamenco dancer; described Dolores playing catch with June; and detailed what she broke around the apartment.

Postcard sceneA postcard scene is typically used in literary and upmarket fiction and moves the story deeper. A postcard scene feels very internal. Nothing happens plot-wise or even character-arc-wise.

If a classic scene moves us from one point in the story to the next, a postcard sinks us deeper inside the same point in the story. The postcard changes the reader by deepening their understanding of the protagonist or their world.

Literary agent and writing instructor Donald Maass, who first coined the term, explained that the postcard is supposed to feel like its postal namesake. When we send postcards to our loved ones from a faraway place, we have limited space, and we will usually write something like: I’m having a wonderful time. The sunsets are incredible. Wish you were here. In other words, we want the recipient to briefly experience the place we’re visiting the way we are experiencing it. Similarly, the point of a postcard scene is to allow the reader to see what it’s like to be the protagonist, to briefly inhabit their shoes.

Let’s get back to June and her dog and see how a postcard might look.

June knew she couldn’t keep the dog. It was infeasible, unimaginable. Her landlord was a horrible, hard man, and June knew that he would enjoy evicting her over Dolores. And it wasn’t like she’d ever made a decision to keep Dolores, it had been a reaction. Upon reaction, upon reaction. She had taken Dolores in, because what else could she have done that day when Dolores almost got run over by a car? And since then, it was more of the same. June could see in Dolores’s sad eyes what she had seen in the mirror so many times, the kind of pain she still carried within herself. When she became someone no one wanted. But now when Dolores curled up to her in what had become their bed, and looked at her with her wide puppy stare, June could feel the same kind of loss she’d experienced all those years ago. In saving Dolores, it felt like who she was really saving was herself.

In this postcard, nothing changes for June. She doesn’t decide on a new course of action, to either get rid of the dog or fight to keep it. The status quo is maintained. She also doesn’t grow as a character—she doesn’t change into someone who is more or less likely to stand up for what she wants. She doesn’t learn anything new, or reach any new conclusion. But the reader’s understanding of June and her motivations deepens. We see why she is so adamant about keeping Dolores.

Using all types of sceneHere are some considerations for scene usage.

1. Know what type of scenes you are writing, and be consistent with the execution. In my editing practice, I often see a scene bleed into a summary and then back into a scene. While you can use a short summary at the very beginning or end of a classic scene, if you choose to display a certain plot event in real time, follow through on it. Time in a classic scene should flow naturally, the way it does in real life. Be strategic about when you start the scene and when you end it; you don’t want the scene to go on for too long.

Using phrases such as ten minutes later or after awhile in the middle of the scene signals that you are summarizing the passage of time mid-scene, which can have a jarring effect on the reader.

2. Consider your genre when choosing the type(s) of scenes you’ll be using in your novel. Readers of commercial fiction usually appreciate the straightforward way one classic scene leads into the next, and the clarity of the time and place, while literary fiction readers will work harder to make connections themselves. Think of scenes as on a spectrum: all genres use classic scenes, but in literary fiction, classic scenes are often interspersed with summaries and postcards.

3. Be mindful of your scene mix. No matter what you write, be consistent with the balance of scenes you’re using. For example, if you’ve been writing exclusively in classic scenes, the reader is going to expect you to continue in that way. If you switch things up mid-narrative and intersperse a variety of summary or postcard scenes, the reader will feel like they’ve stepped into another type of story. If in the opening chapters you offer a mix of all scene types, the reader will expect you to continue doing so.

February 21, 2024

When—and Why—Reveals Don’t Work

Photo by George Milton

Photo by George MiltonToday’s post is by editor Tiffany Yates Martin (@FoxPrintEd). Join her on Wednesday, March 6, for the online class Secrets, Twists, and Reveals.

Every story is a mystery, the reader seduced by that inexorable pull to know what happens next, and why.

It’s the author’s job to create questions that readers crave the answers to. The more you can delay gratification, the greater the arousal of reader’s desire to know.

At least in theory.

This facet of human nature—our insatiable curiosity—explains the appeal of using secrets, twists, and reveals in stories to arouse it.

And yet if not well constructed, these devices can leave readers with so many questions they disengage. Or the reveal might feel anticlimactic.

Writers must maintain a precarious balance between giving too much information and not enough—between boredom and frustration. But writers also have to entice readers into caring about the unknowns, or even the most shocking reveal will feel hollow.

Let’s examine the most common reasons reveals fail, and how to address them.

Problem: We don’t know enough.You know that friend you have (that all of us have), who courts attention by dropping juicy little hints? “Something really big is in the works—but I can’t talk about it yet.” “Oh, believe me, I could tell you some stories about that….” “Wait till you find out about ________.”

Our curiosity might be mildly sparked but we don’t have enough information, so these coy little hints fall flat and we’re likely to feel manipulated and annoyed. That’s how readers feel when an author drops vague hints at some dramatic unknown. In writing it may look like this:

The man in front of her turned to speak to his companion, and her stomach dropped in recognition. How could it be him, after all these years? After everything that happened, how could he dare to show his face in this town? Please don’t turn around, she thought, even as part of her wanted him to, so she could confront him.

Goodness, something exciting is surely going on here, isn’t it?

Or is it? We don’t know, actually. The character seems to feel that way, but readers have to take it on faith because we don’t have enough context to understand what’s happening.

Solution: Ground readers with enough detail to plant their feet in the story, characters, and situation. Instead of “everything that happened,” what if you added a specific detail, like “after he left her standing at the altar at the church around the corner…”

Problem: We know too much.This issue is like your behind-the-curve friend—the one who may think he’s dropping some shocking intel, but his listeners are already two steps ahead. The result: anticlimax, and a bored audience. It’s the book or movie you put down or stop watching because it feels too predictable; the one that leaves you dissatisfied and feeling cheated because it happened exactly as you expected—the author didn’t surprise and delight.

Solution: Find and address where you’ve telegraphed or tipped your hand and pointed too clearly to what you’re trying to conceal; misdirect the reader.

Problem: We don’t care about the character.Another friend tells stories and drops tidbits of gossip about folks in his orbit, hoping to hook his audience with the mystery. But if we don’t know or care about these people, then we don’t care about their secrets either. It’s not driving us mad to know the answers—but sure, fine, we’ll smile and nod politely.

Investing readers in your characters is the single most important work of storytelling: They are the vehicle in which we ride into the story, the lens through which we experience it. If we aren’t invested in your characters, it’s hard to invest in what happens to them—including what unknowns may await and impact them.

Solution: Make sure readers have reasons to care about what your characters experience, what they want, and what drives them.

Problem: Stakes are unclear.This is the friend who drops bombs with great fanfare, but without context. “I walked around the corner and you’ll never guess who I ran smack into—my old boss!”

If we don’t know why the event or information matters, then these are just facts, neutral and unaffecting.

With reveals in story, it may look like this:

She’d known someone was watching her every move, but everyone said it was all in her head, she was just fanning up drama. But there—the steps behind her were quickening along with her heartbeat as she increased her pace, and no one could deny now that she was being followed.

She was tired of running, tired of being scared. Facing whoever it was couldn’t be any worse than the terror she’d lived under for weeks. She stopped, whirled around—and there he was.

Her uncle. Alive.

This could be a shocking and effective reveal if readers know why the uncle matters, and what it means to her that he’s alive and stalking her.

This is tied in with offering enough context, but more than that, we have to know why that context is relevant to the character—meaning what’s at stake for her. An uncle returning from the dead is a bit unusual, to be sure—but to yield the impact the author seems to want, readers have to know more: What does it mean to the protagonist that he’s alive? Was he a threat she thought long past? A beloved mentor whose loss has gutted her in the story? The benefactor whose inheritance she’s using for a driving purpose of her own, whose return threatens that goal?

When finally pulling back the curtain, authors need to lay enough groundwork for readers to understand the impact the discovery will have on the character.

Solution: Show readers why it matters: Pave sufficient context into the story leading up to the reveal so we can understand what effect it has on the character and what she wants, or offer it immediately afterward to answer our questions.

Diagnosing ineffective revealsIt’s easy to be blind to the weaknesses in your story, and how effective your reveals are. If you’re having trouble, this is where beta readers or critique partners can be invaluable. After their read, ask specific questions about how hooked they felt, whether they were surprised by the reveals, and whether the payoffs felt satisfying.

If your reveals aren’t quite holding together, ask for specifics: Where did your readers figure it out ahead of time, and how? Or where and why did they feel confused or uninvested? What was it exactly about the reveal that didn’t have the impact you intended? Encourage frank feedback—this isn’t the time for kind soft-pedaling.

Once you know what’s not working, you can diagnose the cause from a storytelling perspective using the above pitfalls as a guide.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Wednesday, March 6 for the online class Secrets, Twists, and Reveals.

February 20, 2024

Set Up the Perfect Online Press Kit

Photo by cocarinne

Photo by cocarinneToday’s post is by author and website designer Camilla Monk.

How’s your press kit doing these days? Mine was virtually non-existent until I attended an excellent presentation on author press kits hosted by agent Sarah Fisk for the Authors Guild. Sarah’s insightful and actionable advice led me to reflect on what sort of press kits I—and by extension the bloggers and journalists looking to write about authors and their books—see online: mostly downloadable PDFs with low quality images and limited content.

In other words, the very medium we rely on to advertise our books is, more often than not, useless. Journalists and bloggers will find it easier to harvest whatever they can from your website than download your press kit—unless you turn it into an invaluable tool box for the hurried journalist. Here’s how:

1. No PDFIn the name of all faceless interns trying to glue together an online news article at the last minute, please don’t use a PDF.

Copying text from a beautifully designed PDF file can quickly turn into a headache if the pasted contents end up looking like a mangled soup of words.Images in PDF files are compressed and difficult to extract. Should they screen capture, crop, and export? Convert the PDF into a docx file, then export the images? All terrible solutions that will make bloggers and journalists secretly hate you a little as they struggle to snatch a low-quality pic of you.So, if you’re not doing an online press kit as I recommend in point 2, go for a simple Word document and make everyone’s life marginally easier. You want people to distribute your materials widely: make it easy for them.

2. Have an HTML-based press kit at your websiteA well-constructed HTML page at your website is quite simply the easiest way to share both text and images at various resolutions with your visitors. Set up a page where you’ll gather all the information and offer downloads of any relevant materials (sample, photos, and maybe a docx version of your kit’s content for users who simply can’t work any other way.)

Alternatively, or additionally, you can offer a zipped download of your complete kit, with the text content as a Word file, and subfolders where your media content will be organized and clearly labelled, for example: Media/Author pictures/Jane-Doe-High-Res.jpg

Steer clear of advanced design on your press kit page: you want text that’s easy to copy and doesn’t come laden with unnecessary colors and fonts.

Note: Sarah Fisk advises providing journalists with a recording of your name. This is especially useful if you happen to have a foreign name or one that has a counterintuitive pronunciation—like Pete Buttigieg!3. Make your kit exhaustive but not exhausting

Note: Sarah Fisk advises providing journalists with a recording of your name. This is especially useful if you happen to have a foreign name or one that has a counterintuitive pronunciation—like Pete Buttigieg!3. Make your kit exhaustive but not exhaustingHere, I’ll direct you to Sarah’s most excellent and fairly exhaustive Press Kit Checklist. Read it attentively: you might find items you’d never thought of adding, or never even heard about. More than just a checklist, it’s a great introduction to building your marketing platform at large.

Book club questions, games, fun facts, Q&A? Not everything in this list is relevant to you or your title. Try to pick wisely and not overcrowd your press kit with material that might provide very little value to the media.

The first criteria for any piece of your press kit should be: How does this meaningfully relate to my book? And the second is: How does this contribute to building my professional image?

Note the nuance in the latter: The point is not just to talk about yourself, but rather to construct an image of yourself as an author. Say that you’re writing women’s fiction: anecdotes about your family life and career struggles are relevant not only to your books, but also to the image you want to project to your readers, someone women and parents can relate to. If, however, you’re writing a spy thriller or epic fantasy, this information becomes a lot less valuable and may unnecessarily crowd your kit.

4. Build a solid media galleryYou want that book cover and your author headshots to circulate, so help bloggers and journalists do their job!

Include a full gallery of author pictures, cover images, and book mockups. These can be real shots of your books taken by a photographer, or images you generate with online software like Canva, Placeit, or Smartmockups. (This list is not exhaustive.) For each image, make sure you’re offering both medium and high resolution: online journalists may want a lighter image that they can quickly upload, whereas YouTubers or print media will prefer high resolution materials.

Consider a mood board as well: a collection of high-resolution, royalty-free images that paint the atmosphere of your book. Reviewers will love to tap into those to illustrate their social media posts or videos.

As I mentioned earlier, make sure to clearly label each image and describe what it is, and its resolution (low, medium, or high.)

5. Don’t forget samples and ARC linksWhether you’re traditionally or self-published, you probably have samples of your book (and audiobook, if applicable.) Don’t forget to include those, along with links to Advance Reader Copy platforms like Netgalley, if applicable, to encourage any visitor to read and possibly review your book. Again, the name of the game is to make it easy for anyone to click and find more.

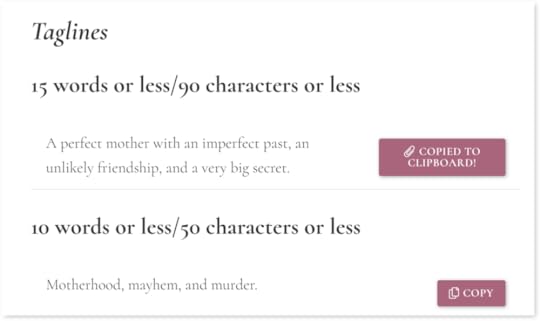

6. Lastly, stand out with copy buttons!It’s such a simple and silly trick and I can’t believe it took me listening to Sarah to think of this. Your press kit targets media who might write about your title on a variety of media platforms: articles, reviews, YouTube videos, etc. They need to work fast and efficiently, and part of their job entails painstakingly copying material from your kit.

So why not make their job ten times easier by dividing your content into sections, each coming with a “copy” button? Want a brief description or tagline to open your review? BAM. It’s done.

This doesn’t require advanced tech capabilities. Here’s an example of what it looks like:

TL;DR: Make it easy for everyone to propagate your press material

TL;DR: Make it easy for everyone to propagate your press materialThis list is not exhaustive, and you might come up with great ideas of your own on how to make it simpler for reviewers and the media to find and use the material they need. Ultimately, that’s all there is to the art of making a press kit—put yourself in the intended user’s shoes and ask yourself:

Is this relevant?Is this easy to find?And is it easy to use and distribute?February 19, 2024

Structure: The Safety Net for Your Memoir

Today’s post is by writer and editor Lisa Cooper Ellison. Join her on Wednesday, Feb. 21, for the online class Find the Memoir Structure That Works for You.

A few weeks ago, I geeked out on structure with screenwriter, filmmaker, and budding memoirist Alyson Shelton. During our conversation, she said, “Structure is the safety net readers fall into. Nailing it is the way we hold space for them and let them know that while we might keep them guessing, or stir up challenging emotions, we’re taking them somewhere important.”

Structure is a safety net for writers too. When it’s missing, they send anxious emails to me and other writing coaches asking what to do. As a writer, I know what it’s like to hang from the trapeze bar of an idea and wonder if I can hold on long enough to find both a point and a satisfying ending.

Writers need to cultivate two types of structure: process and project. Process structure sustains you while you’re drafting and revising. Project structure is what you employ to give your work shape.

Many great writing books teach processes you can follow, but I want to offer you a framework you can use to support yourself regardless of the guidebook you use.

Enter the Circle of Security, a parenting model I encountered during graduate school.

The Circle of Security was created by Robert Marvin, Glen Cooper, Kent Hoffman, and Bert Powell to help parents attend to their child’s needs as they learn to explore the world. Picture an ellipse with a caregiver on one end and images of children at various plot points either moving away from the caregiver as they explore, or reaching back as they seek comfort and reassurance. The caregiver’s job is to pull back as they explore and lean in when they’re feeling unsafe or troubled.

Toddlers need to be able to venture off and investigate the unknown, secure in the knowledge that a parent is there to catch and comfort them if they fall. While writers aren’t toddlers, they also need to venture off, play, meander, and delight in their work while knowing something is there to catch them when doubts emerge, a project veers toward collapse, or the work feels overly emotional or just plain too much.

So how can writers apply this theory to their work?

Build a secure processYour first task is to choose a process to follow. Better yet, form a group that can do this work with you. That way, you’ve got a posse to lean on when the predictable struggles follow.

It doesn’t matter if you select the model Allison K Williams shares in Seven Drafts, the experimental invitations of Jane Alison’s Meander, Spiral, Explode, the journey Sue William Silverman takes you on in Acetylene Torch Songs, or the first-draft guidelines I offer in this post. Pick one. Use the content as your safety net—at least for your next draft—but don’t be afraid to wander off on your own.

When the inevitable doubts creep in, refer back to your safety net. Bask in its comfort and fall into its guidance. If you’re still lost, explore what’s going on with your writing group. When you’re feeling more grounded, wander off again.

Build your memoir’s structureOnce you understand what your story is about, you’re ready to tackle your project’s structure. Some of you will know exactly what this should be. If you don’t, consider whether a simple or complex structure is best for your book. Some structures, like the three-act, will feel like their own safety net, because they deliver a certain level of predictability. The more experimental you are, the more you must serve as that safety net for your reader by truly understanding the story you’re trying to tell and ensuring that the structure you’ve chosen leads them in the direction you’re hoping for.

After you’ve chosen a structure, learn both the basics and nuances of working with it as well as the skills needed to successfully execute it. As you do this, identify one or two exemplar texts to study, and feel free to pick something everyone’s raving about (it needn’t be a comp title for your work). As you mull over which structure might be the best fit, read reviews for these books to see what resonates with readers. Attend to the things people say about how the book is structured or how the story unfolds.

Now, pick it apart. Map the major turning points on note cards. Analyze the thematic threads woven through the narrative. Find the beats where inner change occurs. Do everything you can to understand its construction.

In your next revision, emulate this text’s structure. At this point, don’t worry if it’s a perfect fit. Just see if you can mold your content into it using note cards. After completing this exercise, see if you can expand, fracture, or break free of this constraint to make it your own. If you get lost, or it feels like you’ve broken your book, go back to the map you’ve created for the original text and look at what you might have missed. Once you’ve regained your footing, try again.

If it still fails to work, or it feels like you’re trying to strong arm your story into a structure that simply doesn’t fit, stop. This is a sign that you’ve chosen the wrong structure.

While this might seem like extra work, this process will allow you to truly understand your story and why a specific structure works. The more faith you have in your story’s structure, the more you’ll become the safety net your reader is hoping for.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Wednesday, Feb. 21 for the online class Find the Memoir Structure That Works for You.

February 16, 2024

3 Ways to Experiment with Memoir Structure to Improve Your Narrative Arc

Today’s post is by writer and editor Lisa Cooper Ellison. Join her on Wednesday, Feb. 21, for the online class Find the Memoir Structure That Works for You.

Most memoir first drafts consist of stories writers have told themselves or everyone else. Some of those tales have great punchlines or stab the reader’s heart so deeply they lose their breath. In the beginning, many of us are convinced our only job is to find the words that make those stories sparkle.

But revision teaches us how malleable the truth is. So much depends not on the events themselves, but on how we perceive them. Letting go of capital T “Truth,” we create draft after draft, hoping to at least create something authentic, and maybe beautiful.

Anxieties often spike during this messy middle part of the revision process. One way to calm them—and maybe even have some fun—is to stop searching for The One Perfect Structure and instead spend a few drafts playing around. Experimenting with different forms can teach you important skills and give you the mental flexibility needed to build your narrative arc.

Best of all, it’s possible to do this without hacking your project to pieces—that is, unless you want to.

1. Story draftMemoirs might deal with true events, but they’re closely aligned with fiction. In a story draft, you’ll learn how to employ the elements of storytelling by crafting well-written, engaging scenes that use dialogue, sensory details, and action to bring your story to life. As you string scenes together, you’ll learn how to manage pacing and time.

If you’re a new writer, one of the best ways to learn these skills is to apply a linear, three-act structure to your manuscript. Using this structure as a starting point can teach you how stories work and what’s required to turn your very interesting circumstances into a great book, no matter what structure you ultimately decide on.

To do this without breaking your manuscript, consider writing the key “beat” scenes for your memoir, something Suzette Mullen advocates for in Why Preparing a TED Talk Makes You a Better Memoirist.

2. Letter or epistolary draftPerhaps you’ll finish a story draft and decide that’s all you need to explore. But if the voice is drab, you’re still not sure what your story is about, or you haven’t identified your audience, consider writing at least a portion of your book in letter form.

Epistolary memoirs are written as one, or a series, of letters addressed to a specific person. This structure has a long history in the world of fiction, and includes novels like The Color Purple, Dracula, and Frankenstein. Ta-Nehisi Coates Between the World and Me and Mary Karr’s Lit are two well-known epistolary memoirs addressed to their sons.

Letters are intimate. They take you inside a special relationship. Choosing to write your memoir as a letter to a singular audience can help you hone your voice and decide which scenes truly belong. You can also use this draft to understand your characters.

Gayle Brandeis’s braided memoir, The Art of Misdiagnosis: Surviving My Mother’s Suicide, explores the tangled web of her grief, her mother’s mental illness, and the ways illness and mental illness intersect within this mother/daughter relationship. Gayle’s earliest draft was a straight-forward grief narrative that dealt solely with the aftermath of her mother’s death. But as she began to explore the deeper aspects of her story, she decided to write a draft as a letter to her dead mother. After completing it, she realized her mother needed to have a voice in her memoir. This gave rise to the second arc around her mother’s unfinished documentary, The Art of Misdiagnosis, and the third arc around illness that twines the two women together.

During an interview for the Writing Your Resilience podcast, Laura Davis, author of The Burning Light of Two Stars, talked about how her use of letters evolved over several drafts and why she kept excerpts from certain ones in her published memoir.

To see if this is a good fit, write a single letter to a key character in your memoir, a younger version of yourself, or the reader who most needs your book, and see what you discover. If this work energizes you, consider writing a chunk of your book in this format.

3. Essay draftEssays provide you with an opportunity to build an argument around your topic that can ultimately lead to platform-building bylines and a leaner, more focused narrative arc. They have also been the impetus for several well-known and acclaimed memoirs. Cheryl Strayed’s essay, The Love of My Life, served as the impetus for her memoir Wild. Debra Gwartney’s 2002 radio essay for This American Life led her to write Live Through This: A Mother’s Memoir of Runaway Daughters. Stephanie Land’s essay for Vox led to her book deal for Maid: Hard Work, Low Pay, and a Mother’s Will to Survive.

Writing an essay draft that convinces readers of something can help sharpen your book’s essential argument and become part of the conversation happening around your topic. But sometimes letters, traditional essays, and story drafts aren’t enough—you may still not understand what you’re writing about. If that’s the case, toy around with a hermit crab or braided essay.

Braids allow you to juxtapose items. Take this Brevity essay, The Once Wife by Heidi Fettig Parton, which threads the death of her husband around a trip she took to Germany before the destruction of the Berlin Wall, or Jo Ann Beard’s The Fourth State of Matter. Even if you decide against a braided structure, juxtaposing scenes or events on note cards can lead to new and interesting connections with your material.

Hermit crab essays impose a structure like a syllabus, rejection letter, or body wash instructions onto your material, which forces you to distill your message. This compression, like coal in a cave, can help you create the diamond-like narrative arc you’re looking for. Your essay could encompass your entire book, or a portion of your material. It could even inspire you to write an experimental book, like the Pushcart-Prize nominated memoir, Places We Left Behind by Jennifer Lang.

However you choose to play, note what works, what feels stilted, and what cracks lightning inside you. Those sparks of inspiration are signals that you’re on the way to creating something that’s not just beautiful but authentic and personally true.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Wednesday, Feb. 21 for the online class Find the Memoir Structure That Works for You.

February 15, 2024

What Taylor Swift’s Vault Tracks Can Teach You About Not Killing Your Darlings

Today’s post is by writer and editor Sarah Welch.

I write a lot about killing your darlings. Or, rather, not killing your darlings but saving them for later. These scraps that say something beautiful or important to you, but don’t ultimately fit in your current work-in-progress, can still have serious value for another project down the road. That might be snippets of dialogue, a catchy turn of phrase, or a full-fledged character or plot line.

Not buying it? Let me offer you a little concrete evidence: Taylor Swift’s vault tracks.

Swifties (and I’m one of them) will jump on any chance to listen to new/new-to-them music from Swift, and the vault tracks that come with each album re-record have been gold in so many ways. But what I love about them, as an author, is the peek they give us into a prolific and talented writer’s process. Specifically, they show us what it can look like to save “scraps” for later projects.

Now, before I move on, let me give two disclaimers:

I’m operating under the assumption that, as Swift has said, the vault tracks were written as she worked on each album for the first time. Maybe they were, maybe they weren’t, but with no way to know, I’m choosing to believe her.I’m making conjectures about process based on textual evidence—in this case, lyrics. I have not talked to Swift herself about how she uses her uncut songs to fuel future work. Maybe someday.With that said, here goes.

Vault tracks as scrapsIf the vault tracks are tracks that didn’t make the original albums, then they’re a variation of the “scraps” I tell authors to save from their drafts. They’re scenes, storylines, characters, images, and just pretty combinations of words that don’t fit in the current work in progress for one reason or another.

Let’s look at the Red vault tracks: “Better Man” is a great one to study here, because it’s pretty clear why it was cut from the 2012 album. It’s an amazing country song, but she was transitioning to a poppier sound, and in terms of her evolving image, it held her back rather than moving her forward.

But did she trash the song? No, she turned it over to Little Big Town, who recorded it in 2016, and then she re-recorded it herself for Red (TV). She saw that it was a valuable song, but rather than force it onto an album it didn’t fit, she saved it for the right project, where it thrived.

We can make conjectures about all the vault tracks—maybe some were cut from the original albums to create an emotional balance and avoid too many track-five contenders, while others were cut simply for word count—or, in the case of music pre-Spotify, CD space limitations. Whatever the reasoning, the key is that (thank God) she saved the songs for later instead of tossing them.

Giving scraps new lifeObviously, the mere fact that the songs existed to re-record in the first place is evidence of why saving those scraps is a good move. But if we look more closely at the vault tracks, we can see pieces and fragments of them appear in music she wrote later—images and turns of phrase she set aside for future songs. Let’s look at a few examples.

Castles Crumbling, Speak Now (TV)Swift originally wrote “Castles Crumbling” for her 2010 album, Speak Now, but when it didn’t make the cut, she found opportunities to use the same imagery in future songs, like “Call It What You Want” (Reputation, 2017). The entire context of the song is completely different, of course (with Reputation, she’s turned that crumbling castle into a thing of splendor), but the same image kicks the whole thing off: “My castle crumbled overnight…”

Suburban Legends, 1989 (TV)In “Suburban Legends,” a scrap from 1989, the narrator laments that, “I broke my own heart ’cause you were too polite to do it.” When that song didn’t make the cut in 2014, she held onto the idea, and she used it at least twice in future songs:

“I pushed you to the edge / but you were too polite to leave me” (“coney island,” evermore, 2020)“I broke his heart ’cause he was nice” (“Midnight Rain,” Midnights, 2022)Timeless, Speak Now (TV)I’ve heard this Speak Now vault track called “hilarious,” and I’ll fight anyone else who wants to denigrate it in my presence because I think it’s gorgeous.

I also think it’s Swift’s first time playing with nostalgia in a way that we see happen over and over again in later albums. The vintage photos she finds in the antique shop in 2010 set the stage for plenty of future material:

The sepia-toned account of Bobby and Ethel Kennedy’s relationship in “Starlight” (Red)Her Rebekah Harkness exposé in “the last great american dynasty” (folklore)The blending of her grandfather’s experience in WWII with the realities of COVID-19 in “epiphany” (folklore)Her ode to her grandmother in “marjorie” (evermore)We even see a little bit of it in the vintage feel—and, of course, the 1950s sh!t—of “Lavender Haze” (Midnights)Mr. Perfectly Fine, Fearless (TV)I could write a thesis on how “Mr. Perfectly Fine” sends me right back to 17 years old (my age when Fearless first came out), cruising around in my red Jeep Liberty with my high school besties, but that’s for another blog and another day. (A scrap, you might say, that I should save for later instead of leaving here.)

This breakup bop contains a tiny scrap that you could almost overlook as you scream sing from behind the wheel. In the chorus, Swift refers to her mystery ex as “Mr. Perfectly Fine,” “Mr. Always at the right place at the right time,” and…wait for it…“Mr. Casually Cruel.”

And there it is, a direct path from the boppiest of breakup songs to the most devastating of track fives, “All Too Well” (Red), in which Swift accuses another mystery ex of being “casually cruel in the name of being honest.”

The turn of phrase hits different in each song, but thank goodness she saved it when “Mr. Perfectly Fine” didn’t make Fearless, because there’s no denying it cuts deep in “All Too Well.” (And in the ten-minute version? Forget about it. We’re sobbing.)

Long story short(See what I did there?)

Next time you find yourself making the difficult choice to excise a scene or a character or even a single sentence that you love for the greater good of your novel, think of those cuts as your very own vault tracks. Sure, you could ball them up and trash them (like “crumpled up piece[s] of paper lying here…”), but I encourage you to save them. Stick them in a folder on your hard drive, in a journal, or in a shoebox in the closet—wherever you need to stash them so that, down the road, they can become inspiration for your next masterpiece.

I want to hear from you! How do you save your scraps? Which vault track “scraps” have you been delighted to hear show up in later songs? Email me to talk about your writing, Swift’s writing, or both!

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1885 followers