Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 34

June 4, 2024

Writing Lessons from Jane Austen: Story Questions and Northanger Abbey

Photo by Paolo Chiabrando on Unsplash

Photo by Paolo Chiabrando on UnsplashToday’s post is by book coach Robin Henry.

In case you missed it, 2025 is the 200th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth. There will likely be celebrations, adaptations, and fan fiction abounding all year. It’s worth taking a moment to think about what makes Austen one of the true GOATs in literature.

Great novels ask readers to think about interesting questions. Rather than supply answers, their authors present readers with opportunities to consider two types of story questions:

Big Picture or Thematic QuestionsPlot QuestionsFor example, in a murder mystery the plot question is usually “Who is the murderer?” The big picture question might be “How could an average person be pushed far enough to commit a murder?” or “Why do people hurt each other?” The big picture question generally has a philosophical bent.

In Northanger Abbey, Jane Austen asks story questions through her characters’ goals, motivations, and conflict, as well as the plot. Her characters participate, wittingly or not, in an examination of the big picture question, as well as the plot question.

Austen added a preface to Northanger Abbey while preparing it for publication to explain that because it had originally been finished in 1803, “The public are entreated to bear in mind that thirteen years have passed since it was finished, many more since it was begun, and that during that period, places, manners, books, and opinions have undergone considerable changes.” Austen knew that to enjoy Northanger Abbey fully as a satire of Gothic novels of that earlier time, it was important to understand the books and opinions about books which were in vogue at the time it was originally written.

Her concern is understandable, because the underlying big picture question of Northanger Abbey is, “How do novels affect readers?”

Austen’s thematic story question is clear from the opening, when she introduces Catherine, “from fifteen to seventeen she was in training for a heroine; she read all such works as heroines must read to supply their memories with those quotations which are so serviceable and so soothing in the vicissitudes of their eventful lives.” It is Catherine’s misreading of the Gothic, along with her friend Isabelle’s, that drives the plot, most famously when she suspects that General Tilney has murdered his wife—leading to her crisis confrontation with Henry, and her growth through self reflection.

Catherine uses her reading to learn lessons both good and bad. Though she succumbs to the mistaken idea that the General is a murderer, she is not all wrong about his character. He is somewhat villainous, as is made plain by his banishment of her late at night to a carriage in which she must ride unaccompanied to return to her home. Austen uses this and another carriage episode earlier in the novel to illustrate her characters’ goals, motivations, and conflict. Though Catherine’s reading had taught her that she ought not to go riding alone with John Thorpe, since it was inappropriate and the heroines in Gothic novels are frequently kidnapped or worse in fast moving carriages, she had been persuaded to set aside caution by her inept, non-reading chaperone, Mrs. Allen. When forced into the carriage by General Tilney, she is able to cope because she has grown as a character. She makes it home without incident.

Characters in Northanger Abbey are revealed through their novel reading, misreading, and lack of reading. Henry Tilney is a rational charmer who waxes on the picaresque, a popular writing style of the time. As a wide reader of good sense, he has read novels and does not disparage them, but warns Catherine to be careful not to think life is like a novel, even teasing her about visiting Northanger Abbey when they first arrive. He has read the Gothic novels of which Catherine is so fond, but he takes them for entertainment rather than a life manual, and encourages Catherine to do the same during their confrontation over her suspicions of General Tilney, “Remember that we are English, that we are Christians. Consult your own understanding, your own sense of the probable, your own observation of what is passing around you. … Dearest Miss Morland, what ideas have you been admitting?” (Chapter 24) It is Henry’s disapproval that breaks the spell of misreading for Catherine. She begins to rationally examine the ideas she sees in books.

John Thorpe, in contrast, goes on about novels being nonsense and then explains that the only two he has enjoyed are Tom Jones and The Monk—two books with plenty of sex and seduction, and a deal of it explicit—to Catherine, whom he is supposedly courting for marriage, thus betraying his lack of couth and tact. At this point in their relationship, Catherine is too innocent to catch the references, however Austen’s readers most likely would have done and had fair warning, if they needed it, of Thorpe’s real character.

Notice that the major story question—how do novels affect readers?—is apparent throughout the novel in both plot and character. The characters are different types of readers, and have different reactions to the novels they read: Catherine is naive, Henry rational, Thorpe careless, leaving the reader of Northanger Abbey to conclude that perhaps it isn’t the novels that are the problem.

One cannot write a discussion of novel reading and Northanger Abbey without including that most famous of Austen quotations. After a slightly longish narrator intrusion about how authors themselves denigrate novels by not allowing their heroines to read them, she writes that novels are works “in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.”

Thus, it is clear that posing the question of whether people should read novels and how they should read them is the major story question of Northanger Abbey. The question of novel reading is apparent on every page of the book. It was a major debate in Austen’s time, especially with regard to how women read as opposed to how men read and what they read, all of which are part of the examination of reading in Northanger Abbey.

Notice, though, that the reader is never instructed by Austen as to what the answer to this question is. The intrusive narrator has an opinion, but it is the story of Northanger Abbey which poses various answers to the question of how readers are affected by novels. Different readers have different responses to books and different levels of engagement with literature, which leads the reader of Austen’s novel to form their own opinion, rather than be given the answer. We are never told that Henry is a good reader or that Thorpe is a bad reader, we are left to make that judgment for ourselves.

And what about the Plot question? In a Marriage Plot, much like a romance novel, the question is will they or won’t they, and the answer is, yes they will—it is just a matter of how. Just as each character considers the thematic question, each character has a role to play in answering the plot question. The Allens may have been shoddy chaperones, but their agreement to let Catherine visit the Tilneys allowed her to develop her relationship with Eleanor and Henry. John Thorpe was definitely a cad and Isabelle possibly a libertine (because she read too many Gothic novels, or did she just read the racy parts?), but it is in contrast to them that Eleanor and Henry shine as beacons of sense and attachment.

Austen’s work stands out among her peers and has stood the test of time, partly because of the way she handles story questions. The thematic question is clear and apparent—it remains always present in the actions of the characters and the consequences, and importantly, each character deals with the question in their own way, providing the reader with something to think over in response. As one of the early architects of the novel as a form, Austen’s use of a unifying thematic question elevated and advanced the form, contributing to the development of long form narratives.

Austen was careful not to waste pages on non-plot question related events as well. Each event and character action/reaction leads logically to the next, even when Catherine is basing her actions on her Gothic novels. Within the framework of what she perceives to be true at the time, she is following a line of “story logic” that leads her to take action. Austen lets the characters drive the plot, using the thematic and plot questions as her guardrails in telling the story.

Practice using story questions with your own work

What are your big picture and plot story questions? (at least one of each)List four to six characters from your novel and describe how their actions and decisions reveal the story questions. Limit yourself to 100 words for each character.List the major plot events in your novel (inciting incident, complication, crisis, climax, resolution) and explain how the story question informs each event. Try to keep it to 250 words.May 30, 2024

Crafting Memoir with a Message: Blending Story with Self-Help

Photo by Google DeepMind

Photo by Google DeepMindToday’s post is by Maggie Langrick, publisher at Wonderwell Press.

In my role as founding publisher at Wonderwell Press, I meet many aspiring authors who are stuck on the question of whether to write a how-to book or a memoir.

On one hand, they yearn to share their story but haven’t got the platform or literary cachet required to compete in the narrative nonfiction space. On the other hand, they have helpful insights to share but don’t feel comfortable writing a prescriptive book, especially if their advice stems from personal experience rather than professional expertise.

If you’re grappling with this decision, I have good news for you: You don’t necessarily have to choose one over the other—it is possible to share your story in a way that helps people with a specific issue, rather than simply providing an entertaining read. Enter the “memoir with a message.”

A typical memoir leans heavily on entertainment value through the author’s artistry and storytelling skills. But a memoir with a message goes beyond traditional storytelling and pulls universal lessons out of the author’s personal experience. These memoirs do more than recount the author’s life; they distill insights from those experiences into advice or principles that readers can apply to their own lives.

The best argument for considering this format? Due to their practical value, a memoir with a message can be easier to sell to publishers than a straight narrative memoir, because the publisher will also find it easier to sell this type of memoir to booksellers. Some acquiring editors will ask memoirists to retool their manuscript in this way so that it can be shelved in the self-help section. Some good examples of successful traditionally published books that fall into this category include:

Tough Titties by Laura Belgray (Message: You can be a slacker/late bloomer and still win at life, just like me.)We Are the Luckiest by Laura McKowen (Message: Getting sober is worth it; here’s how I did it.)Unfollow Your Passion by Terri Trespicio (Message: It’s OK to wing it through life; here’s how I did it.)Buy Yourself the F*cking Lilies and Glow in the F*cking Dark by Tara Schuster (Message: You can heal your own mental health issues, just as I did.)I interviewed three of the above authors on my podcast, The Selfish Gift, and in each case, the author told me that she initially pitched a straight memoir in her book proposal before her agent or acquiring editor pressed her to boost the prescriptive elements to make it an easier sell.

Each of these is, in essence, a book of personal narrative that straddles the line between memoir and self-help, though it’s worth noting that each one leans in one or the other direction. The first two are memoir-leaning but clearly speak to specific issues that the author shares with readers, and are positioned as books you would read to help yourself make a shift. The second two lean into self-help but are heavily built around the author’s personal story rather than professional credentials.

Here’s how you can craft a memoir that not only shares your story but also offers the guidance that readers of self-help books are seeking.

Define your core messageBegin by identifying the central message you want to convey through your memoir. What are the lessons you’ve learned from your life experiences that you believe can help others? This message should be a universal truth or insight that extends beyond your own story to connect with a broader audience. Whether it’s overcoming adversity, finding resilience in the face of loss, or mastering the art of happiness, your message will serve as the backbone of your memoir, giving it direction and purpose.

Structure your story strategicallyThe structure of your memoir is crucial in weaving your personal experiences with self-help elements. Unlike a traditional autobiography, a memoir with a message should be organized around key themes rather than sticking to a chronological sequence. Each chapter should focus on a specific aspect of your experience and relate it back to your central message. Use your personal stories to illustrate these themes, and conclude each chapter with reflections or lessons that elevate the narrative from mere storytelling to insightful guidance.

Incorporate teachable momentsAs you recount your experiences, highlight moments that taught you valuable lessons. These moments should serve as stepping stones in the narrative, providing not only a deeper understanding of your journey but also offering readers practical takeaways. For instance, if your memoir focuses on personal transformation, share the challenges and breakthroughs that shaped your path, and distill these into lessons that the reader can apply in their own life.

Engage with honesty and vulnerabilityThe power of a memoir lies in its authenticity and emotional truth. Be honest and vulnerable in sharing your failures as well as your successes. This authenticity creates a connection with readers, making your advice more credible and relatable. Vulnerability can be a potent tool in self-help memoirs, as it encourages readers to reflect on their own lives and challenges with a new perspective. It also positions you as a peer who has been there, rather than talking down to your reader, or coming across as preachy or professorial.

Use reflective questions and exercisesTo enhance the self-help aspect of your memoir, consider including reflective questions, prompts, or exercises at the end of chapters. These tools invite readers to engage actively with the material, apply the lessons to their own lives, and facilitate personal growth. This interactive element can transform your memoir from a passive reading experience into a dynamic tool for personal development.

Maintain a positive, inspirational toneYour tone should inspire and motivate. Even when delving into difficult subjects, don’t show up to the page with an axe to grind. You’re not writing to unload unresolved trauma or resentment on your reader, but to serve as an illuminating example of growth and healing. Highlighting the positive changes in your life as a result of your experiences can motivate readers to seek similar transformations in their own lives.

Give each element the care it deservesA caveat: This is not a superficial remedy for an otherwise weak manuscript. Many industry experts (including Jane Friedman) are cautious about recommending this approach and may even steer new writers away from it because it’s easy to view this as a quick fix. Your book—whether it is a straight memoir, a memoir with a message, or a prescriptive nonfiction book—needs to meet a very high bar to be successful, and there is no literary device clever enough to turn a bad book into a bestseller.

One thing all the titles I’ve held up as examples in this article have in common is that they are excellent books: well-written, insightful, entertaining, and instructive to various degrees. Every element in your book needs to be of high quality, so give each one the care it deserves. Conduct thoughtful research if you are taking a journalistic approach to your message. Thoroughly test any advice or instructions you may be providing to ensure your prescriptions are truly effective and relevant to a majority of your readers. And, of course, be sure to tell a great story rich in insight, color, drama, sparkling dialogue, and satisfying character development.

When executed well, a memoir with a message offers a unique opportunity to touch lives through the power of personal narrative combined with practical wisdom. By clearly defining your message, strategically structuring your story, and integrating actionable advice, you can create a compelling memoir that stands as a beacon of hope and guidance on the self-help shelves.

May 29, 2024

Choosing Story Settings Based on Genre

Photo by Laila Gebhard on Unsplash

Photo by Laila Gebhard on UnsplashToday’s post is by author Jane K. Cleland. Join her on Wednesday, July 10, for the online class Mastering Suspense, Structure & Plot.

Different genres come with different reader expectations that pertain to setting. For instance, readers expect cozies to be set in small towns and hard-boiled detective stories to be based in cities. In some genres, such as fantasy, world building is crucial. For instance, if you’re writing a novel about an underwater civilization, you might:

Integrate challenging terrain, such as caverns and mountain ranges to enable your characters to showcase their athleticism, bravery, or wit.Create longing through juxtaposition by featuring a man who yearns to live on dry land and allow him access to a sand bar where he can see grass and forests, his dream so close, and yet so far away.Invent societal systems that are consistent and logical, and develop characters who understand how those systems operate—a kind of pecking order, perhaps, that allows warriors to inhabit the deeper environs, relegating the rest of society to the less desirable surface areas.In other genres, like historical fiction, readers want to be immersed in the period not only to see what was there and what wasn’t, but to experience how people lived. In Diana Gabaldon’s New York Times bestseller Outlander, the Scottish Highlands come alive with lush descriptions—but these descriptions occur only as characters interact with the environment.

While in the Scottish Highlands in 1945, Claire touches a stone in a circular henge and is mysteriously transported back to 1743. Marrying historical romance to time travel, the events feel contemporary. The fields of heather, the craggy rocks, the dark castles, the mysterious stones, every element evokes a sense of time and place. The book runs to 850 pages, yet because the focus is on incident, not description, the enduringly popular novel is considered a fast read.

Contemporary romance readers also expect settings to transport them to another world. Readers of this genre crave the entire romance package, not simply a love story. They want to vicariously experience a grand romance. They don’t want merely to walk down the Champs-Élysées in Paris—that’s a place they know well (in their imaginations) from the countless books, movies, and television shows that feature it. They want a unique experience. Take them someplace they can’t go on their own, like an appointment at the American Embassy in Paris or a party at the Ambassador’s residence. Don’t merely send them into the National Gallery of Art in London; let them sit in on a curatorial meeting with the King’s archivist. Don’t make them sit passively on the outside patio at Bangkok’s Peninsula Hotel, or if you do, be certain they see something remarkable, like a woman in in a tight black dress and stiletto heels jumping onto a commuter boat traveling along the Chao Phraya River. Readers would rather go on an elephant ride through the jungle outside Bangkok or get a sexy soapy massage in the Huay Kwang section of the city than sit quietly in a hotel room. When writing unusual locations, go big.

This principle isn’t unique to romance readers. All readers want to spend time in settings they don’t know, or settings that, while familiar, are freshly envisioned. Consider John Cheever’s 1964 short story, “The Swimmer,” a retelling of the Greek myth of Narcissus. Narcissus, you’ll recall, died staring at his own reflection shimmering in a pool of water. In “The Swimmer,” which was originally published in The New Yorker, Cheever used his trademark suburban setting to make observations about social status, wealth, and self-aggrandizement. As the story becomes increasingly surreal, readers’ perceptions of suburbia darken.

Judith Guest’s 1976 novel, Ordinary People, also focuses on an affluent suburban family. The nondistinctive environment—the kind of upper-middle-class suburban oasis found in all fifty states—casts the extraordinary events into sharp relief. This idealized family is ripped apart when the eldest son, Buck, is killed in a sailing accident. Conrad, the younger son, survives. Ordinary People follows the three remaining members of the family, Conrad and his parents, as they come to terms with their loss. The book is written in the third-person omniscient voice, in the present tense, with chapters alternating between the surviving son, Conrad, and his father, Calvin. Dealing with themes of life and death, survival and suicide, trust and betrayal, this work of literary fiction uses its affluent location as a counterpoint to the desolate emotions the characters must confront.

Sensory references bring your setting to lifeAfter you’ve determined what your suspenseful setting looks like, it’s time to write. The more sensory references you integrate, the more heightened the suspense. Whether the suspenseful moment is action-oriented (e.g., a ghoulish creature chasing your protagonist through the deserted streets of an urban wasteland, drawing ever closer) or psychological (e.g., a country kitchen where an apparently kind woman’s barbed criticisms grow ever darker), your readers will feel more present if they can experience the situation as if they’re in the scene themselves. Getting your thoughts in order before you put pen to paper ensures your description will enliven the scene, not slow it down.

Whatever settings you choose, they need to align with your theme, support the plot, and help define your characters. This idea of people interacting with places provides rich opportunities for subtle and deep engagement.

Opposites attractSometimes you want to choose a setting that contrasts with your character’s longing or your story’s conflict. For instance, consider how intriguing these paradoxical pairings might be.

A romance between a convicted killer and a lonely woman. Their searing love affair develops in a dingy prison visiting room under a guard’s watchful eye. A memoir focusing on a woman’s dramatic rise from poverty and homelessness to the corporate boardroom. The first time she goes home after reaching this pinnacle of success, she visits an old school chum who now lives in a desolate trailer park.Choosing settings that contrast with your characters’ situations adds spice to your stories, highlighting your thematic underpinnings by encouraging readers to think about the deep issues in your stories.

People interacting with placesOne of the themes in my Josie Prescott Antiques Mysteries is finding community. Josie, after losing her job, her friends, her boyfriend, and her dad, all within a few months, decides to move to Rocky Point, New Hampshire, to start a new life. New Hampshire’s rugged coastline and long, hard winters contrast sharply with the theme, allowing me to write about places that bridge the gap between theme and place. Consider this excerpt from 2016’s Glow of Death:

Frills of white caps and sun-sparked opalescent sequins dotted the dark blue ocean. Rocky Point, New Hampshire, was beautiful in all seasons, from the fiery colors of autumn to the pristine whites of winter to the red buds and unfurled green leaves of spring, but it was summer I liked the most. The wild grasses on the sandy dunes. The buttercups and honeysuckle. The easy breezes. I was a sucker for a breeze.

Rather than simply describing Rocky Point, I let my readers see it through Josie’s eyes.

In Isak Dinesen’s 1938 novel, Out of Africa, the narrator starts with a description of the farm where the protagonist lives. The exposition goes on for more than 3,500 words (more than ten pages) before we come to some dialogue. The narration is written in the first person, so while it might be cumbersome for today’s readers, you are able to see what the protagonist sees, such as trees that are different from those found in Europe.

That reflection occurs in the second paragraph of the novel, and from that singular comment, we garner important information about the character. This technique—slipping backstory into descriptions of setting by letting your readers experience the place alongside your character—is one of the best ways to let your readers in on your character’s secrets, opinions, heritage, longings, and intentions.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Wednesday, July 10, for the online class Mastering Suspense, Structure & Plot.

May 24, 2024

The Compounding Value of Small Group Writing Retreats and Intensives

Photo by Ray Harrington on Unsplash

Photo by Ray Harrington on UnsplashToday’s post is by retired doctor turned writer Sandra Eliason.

When I hung up my stethoscope in 2017, I started writing, believing that my 30-plus years of chart notes, limited as they were, had kept me somewhat in practice. My first degree was in English, and most of my years as a doctor were before computers, when the chart wasn’t automated fill-in-the-blank, and I had an opportunity to tell a patient’s story. Winning the 2016 Minnesota Medicine magazine writing contest encouraged me to go for it.

I soon learned, however, that chart writing and creative writing were two entirely separate endeavors. My career had required me to practice “just the facts, ma’am.” Now, descriptive details of sight and sound, taste and smell were not only important, but necessary to set a scene. To learn how, I took two creative writing classes at the University of Minnesota, signed up for online courses, went to writing conferences, took a year-long memoir-writing course, and attended workshops. I added several writing intensives. All were helpful, and my writing grew. Publication in Best American Essays 2023 encouraged me again. Then, rejections began piling up, convincing me my writing wasn’t “there” yet: I must need more help.

Where to turn next? I found multiple intensives advertised in wonderful and even exotic locations, with excellent teachers. Low-res MFAs beckoned. Residencies advertised. How to choose from the offerings of excellent instructors in enticing venues that would meet my specific needs?

Then I saw Rebirth Your Writing with Allison K Williams aboard the Queen Mary 2, with three additional fabulous teachers—Dinty W. Moore, Amy Goldmacher, and, finally, Jane Friedman. The format intrigued me: multiple teachers, multiple days, one location. A whole week to learn from four people with different perspectives and areas of expertise, and nowhere to go except aboard the ship.

This course design presented opportunities not usually available. Each morning in a combined session, one or more instructors led us to explore setting priorities for our creative life, choosing and using social media, crafting compelling first pages, querying, or being present in your writing. Each instructor made available added one-on-one time, to review specific pages or stuck points in a writer’s work. During breakout sessions, one could stay with a single instructor over the week, or choose a different one each day, depending on which topic addressed the writer’s needs. We participants sorted ourselves to fit our situation, thus also learning from each other—I heard conversations about sessions I did not attend, and which tidbits someone needed at this point in their writing.

Dinty W. Moore reviewed my lagging essays, Allison K Williams helped focus my query and a weak chapter, and Amy Goldmacher showed me how to refine chapter summaries, leaving my afternoons to learn from Jane.

Because of that unique structure, two things happened:

The individual and collective wisdom of instructors, with their interactions, allowed each day’s topic to not only build on the previous day’s, but reinforce it, adding more depth and meaning. Reviewing my notes, I found similar themes recurring. Each time I jotted an idea down, I had increased understanding of the thing I needed to learn, stated in a new way. I had heard much of it before, but in a “one and done” session, it seemed to go into my ears and get lost in my brain. Seven days in the same space, hearing the same teachers’ wisdom, made it stick.Spending many days with the same instructor adds both complexity and clarity to the knowledge—complexity because as each topic builds, the nuances expand, and clarity, because as a topic is better defined, it becomes clearer. I chose my afternoons with Jane because hers was the information I needed most. And although some of it was repeated information for me, once the retreat was over I felt more ready to use the tools I was given than I had after any single course.My retreat week began with an individual session with Jane. I had felt lost about where to enter social media. It seemed like a painful chore I had to do only because agents wanted it. I couldn’t force myself to engage, and the effort seemed futile. Half an hour with Jane refocused my understanding. She helped me see that I had a mission—I had just not defined it. Stating that mission, and learning how to focus social media around it, was exciting; my brain lit up with ideas. With that clarity, each day’s class added to my understanding of how multiple tools could advance my writing career: website best practices, social media use focused around mission, newsletter how-to, book launch ideas. A plethora of things built on each other over each day, and planted themselves in my brain, because they came with understanding of how they fit together, and were reinforced daily.

Writing conferences and classes are important opportunities I will continue to attend. But the format of multiple instructors + the same location + time = a multiplier effect of learning that a single event does not provide. Going forward, I will look for courses offering this method of learning, and I recommend it as an effective tool to advance one’s writing.

Want to read more about this specific retreat and the Queen Mary 2?Queen Mary 2: 10 Things to Know by Elinor FlorenceCrossing the Seas and Dotting the I’s by Margo WarrenTo learn about future opportunities, sign up for news from Allison K Williams’ Rebirth Your Book retreat series.

May 23, 2024

How to Stop Gaslighting Your Memoir Writing Process

Photo by Kristina Flour on Unsplash

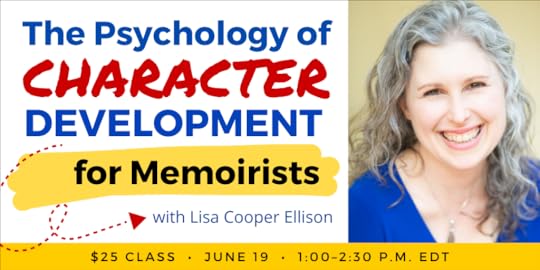

Photo by Kristina Flour on UnsplashToday’s post is by writer and editor Lisa Cooper Ellison. Join her on Wednesday, June 19, for the online class The Psychology of Character Development for Memoirists.

Here are two of the most hated pieces of feedback I’ve given to writers of tough stories:

Your story needs more levity.Your antagonist needs to be more balanced.In response, I’ve watched writers who’ve endured extensive abuse grit their teeth and force themselves to write about the one time Mom took them for ice cream or said a kind thing in hopes of pleasing me. “There,” they often say. “Is that what you’re looking for?”

The effort feels fake to them, and, honestly, it reads that way too. As we review their work, I see the deep pain in their eyes, because what they’ve written pushes against what they’re trying to do: own their version of the truth.

Revisions like this trigger all the old messages they’ve internalized.

Maybe it wasn’t that bad.

You’re overdramatizing.

I didn’t mean it.

If it was that bad, you probably caused it.

Watching them, I can see they’re about to gaslight themselves.

Gaslighting is a term people casually throw around or use incorrectly to avoid confrontations. The term comes from the 1938 play, Gas Light, which was turned into a movie. It’s a form of psychological manipulation where an abuser attempts to sow self-doubt and confusion in their victim’s mind. The message behind gaslighting is that what you see—and most importantly what you feel—isn’t real. It’s one of the many tools narcissists use to meet their needs. If gaslighting happens often, and especially it if happens in childhood, you can begin to do it to yourself.

But you don’t need to be a trauma survivor to gaslight your memoir-writing process. Dr. Ramani Durvasula, narcissism expert and author of It’s Not You: Identifying and Healing from Narcissistic People, says, “Narcissism is, indeed, the new world order.” While some people grow up in homes where dangerous forms of narcissism lead to severe abuse, most of us will encounter lesser forms at work or school and in friendships or romantic partnerships.

There are three times when self-gaslighting can derail your writing process.

If you grew up in a home where “what happens here stays here,” then writing your first few drafts, or showing your story to others, might feel like you’re breaking a cardinal family rule. When this happens, you might try to downplay or delete things family members might disapprove of. During research, memory lapses or inaccuracies you’ve uncovered can lead you to wonder if you’re making it all up. Feedback on sensitive material that suggests the work needs to be lighter or more palatable can cause an internal tug-of-war around whom to please—your reviewers or yourself.Recognize the signsIf you want to stop self-gaslighting, you must first recognize when you’re doing it. Emotional signals include resentment toward instructors, critique group members, or editors for “forcing” you to make situations or characters more appealing; it can also include episodes of panicky doubts and a desire to discount your experiences to please reviewers. You might notice tension in your neck, shoulders, or jaw as you write something that meets their expectations but doesn’t personally ring true. Then there are the memory games we play, hoping to locate that single moment of good in a rotten relationship.

Once you’ve identified the problem, it’s time to address it.

Find your powerNever forget that you are the great architect of your story. Does this mean you’ll never have to revise your memoir in ways that feel challenging or that you resist? Not a chance. But you can recast certain scenes and remain true to your experience. Just keep in mind that how you see things will evolve. That’s why it’s so important to give yourself time to process what happened and dig deeply into your memoir’s deepest truths.

Levity can mean many thingsOnce you’re powered up, examine your options. In fiction, we’re told to be hard on our characters. Give them hell, a writing instructor once told me. In memoir, this advice can result in manuscripts where seemingly unrelated traumas are strung together. But a memoir isn’t pain porn. It’s a story crafted from an interlocking series of events that ratchet up in intensity as the narrator transforms. But if everything in your book goes to eleven, your brain won’t be able to identify what’s important. Like a song consisting of both notes and rests, this journey must include moments of relief where readers can catch their breath. Yet those moments shouldn’t be manufactured.

One way to create levity is by compressing certain moments, culling unnecessary scenes, or cutting repetition. For example, if your memoir includes five instances where your antagonist lies, pick the best one. If more than one is essential, your second, and final versions must up the ante.

If you must add new things, know that levity can come from lots of places.

In Laura Cathcart Robbins’s memoir Stash, the misery of withdrawal and her self-loathing are at first relieved by getting high or sweet moments with her sons. Once she enters rehab, it’s her interactions with her love interest. Laura Davis brings both relief and context to her narrative by inserting letters into The Burning Light of Two Stars. Jennifer Lunden added copious research to her hybrid memoir American Breakdown to both lay claim to her truth and break up the relentless misery of living with a chronic illness. Ingrid Clayton shared some of her mother’s painful history as context for why she chose her narcissistic stepfather over her daughter in her memoir, Believing Me.Trust that creating interesting characters won’t sway your readersIf someone has repeatedly hurt you, trying to make them more redeemable by providing context might hit your gaslight button. But it doesn’t have to.

In a training I attended, renowned addictions specialist Gabor Maté said hurt people hurt people. This is especially true in families. That means hurt is often the fuel for most bad behavior. Abused people often fear readers will see an antagonist’s vulnerabilities and side with them. That might be exactly what happened in real life. But adding context for a character’s actions only makes them more interesting, not better.

In The Liars’ Club, Mary Karr briefly mentions that her mother lost custody of her first two children. Halfway through The Glass Castle, we discover that Rex Walls was likely abused by his mother. Knowing these things prevents these characters from being one sided, but it doesn’t excuse the time Mary’s mother told her to run her broken arm under a bar’s hand dryer, or the scene where Rex sends Jeannette off with a guy he’s hustled at a bar.

Build real insightsWhen writing memoir, the most important—and interesting—thing you can do is make meaning from your experiences. While every memoir should end on a relatively high note of transformation, adding in aha moments along the way can bring lightness to your work that serve as the precious rest notes readers crave. But they’re not just for the reader. While searching for those ahas, you’re connecting with the hero in a younger version of yourself—a connection that empowers you, the writer, and your story. Of all the strategies that can gaslight-proof your writing process, that’s the most important one.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Wednesday, June 19, for the online class The Psychology of Character Development for Memoirists.

May 22, 2024

Is Your Story “Big Enough” to Write About?

Photo by Pixabay

Photo by PixabayToday’s post is excerpted from Heart. Soul. Pen.: Find Your Voice on the Page and in Your Life by Robin Finn (Morehouse Publishing).

Limiting beliefs (also called misbeliefs) are judgments or misinterpretations of reality that hold us back or limit what we can do, be, or achieve. One of the most powerful breakthroughs I had while studying spiritual psychology was that I could change my belief system. I learned that I could consciously identify, revise, and release any beliefs I had that did not serve me, made me miserable, or held me back. I did not have to hold onto beliefs from second grade, or from PTA meetings, or that other people placed on me.

When I changed my beliefs, my life experience changed. That is how powerful and predictive inner beliefs are: they dictate your inner thoughts as well as your outer experience.

While creating a new belief system gave me a sense of relief right away, I did not immediately embrace these new beliefs. It took time. I had to practice daily. I would catch myself falling into my old limiting beliefs and I would need to read, review, and accept my new beliefs over and over again. The more I repeated the new beliefs, the more comfortable I became with them. Eventually, they simply became my new belief system.

After I completed my spiritual psychology program, I wanted to take a writing class. Writing had been calling me for years, but I resisted. Every time I thought about it, I always came up with reasons why the timing was not right. After I earned my master’s degree, I decided now was the time.

But I could feel the limiting beliefs inside of me. I knew they were there. I knew that I held judgments against myself. I knew that I did not believe I was a real writer. I knew that I thought everyone else was cooler and smarter and way more interesting than me, a middle‐aged mother of three. I knew it and I could feel it and I knew I had to face it.

So I examined my beliefs about writing and worthiness by writing down each belief. Mine looked like this:

Only young, hip people have something to say.I am too old to write.It is too late.My writing is embarrassing.The topics I am writing about are boring.No one will care about what I am writing.I am not a good writer.I should stop trying.If I keep writing, everyone will see I am not good enough.I missed my chance.I reviewed each belief according to two main questions:

Does this belief support my goal to write, express myself, unleash my radical self‐expression?Does this belief make me feel good—is it uplifting?If the answer to both questions was “yes,” I kept the belief. If the answer to either question in whole or in part was “no,” I revised or released it.

I created new beliefs that supported my goal to write and express myself. Here were my beliefs when I finished:

I write because I feel called.I am naturally creative.Writing is an adventure.I am curious about what words will emerge.I give myself permission to write what is true for me.I am worthy of hearing and expressing myself.I am safe.I am allowed to be seen.It is enough to show up and write.I am enough.Now is the perfect time.I have compassion for myself.Getting rid of my limiting beliefs about writing, about myself as a writer, and about my own worthiness gave me the sense of relief I experienced when I used the same approach with parenting. But, like before, it also took time to fully embrace these new beliefs. Seven years later, I was a widely published essayist.

Limiting beliefs limit our capabilities.If we want to find our voice, write with abandon, or allow our thoughts and ideas to flow onto the page, we have to stop and look at the beliefs we hold about writing before we start writing. If we do not take the time to identify, revise, and release limiting beliefs, writing often goes like this:

You feel the creative spark or a strong call to write. Some story or seed or idea wants to come out and be expressed. You are excited to write.You buy a new journal, enroll in a writing class, or commit to set aside time to work on a bubbling story, poem, or essay, or simply let out your thoughts on the page. You feel inspired. You begin to write.You read what you wrote and judge it. You decide it is not good. Or you like it and share it with a friend, teacher, or writing group and the feedback you get confuses you or undermines your belief in the idea. You had the best of intentions but now you struggle and freeze.You stop writing.You give up. Amazon • Bookshop

Amazon • BookshopWhen I talk with students who have encountered this phenomenon, they tell me that, deep down, they did not feel their story was enough—not big enough or important enough or worthy enough—to justify spending time writing about it. They tell me they felt they did not have the authority, wisdom, talent, or commitment to write it. They tell me that giving up made them miserable because they deeply wanted to write, but they could not muster the energy or focus or inspiration to keep going. I tell them that writing while holding limiting beliefs about writing is hard. But that does not mean you should give up your writing. It means you should give up your limiting beliefs.

In addition, society sends gendered messages to women about the value of their stories. These messages suggest women’s stories are not important, women’s issues are taboo/inappropriate/should remain hidden, women’s experiences are not interesting, particularly those of older women. These messages look like:

Whoops, woman over thirty, you’re past your prime.Midlife women, you are too old to start writing or to keep writing or to write anything anyone wants to read.You are a mother? People are not interested in your child‐rearing stories or how hard it is to parent or how tired you are of making the same meal every day for three years for picky eaters or that you won’t eat cake at your birthday party because you’re afraid of gaining weight or how crazy your own mother made you feel.No one wants to hear about period pain or pregnancy or menopause. Please keep your bodily functions and your hot flashes, night sweats, and meno‐fog to yourself.Abortion, sexual assault, and workplace discrimination are hot button issues: you better proceed carefully.Your story is boring and/or we have heard it before, so we don’t need to hear it again.Here is what I know about limiting beliefs. We all have them. There are different versions and often originate in childhood or when we are young, but essentially, all say the same thing: you are not good enough so stop writing. They keep us small and quiet. They force us to give up. They plague women by playing on our fears that we are “not enough.” They shut us down. They are designed to protect us and keep us safe from harm. They are not true.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out Heart. Soul. Pen.: Find Your Voice on the Page and in Your Life by Robin Finn.

May 21, 2024

Defining Negative Space in Story

Photo by Randy Laybourne on Unsplash

Photo by Randy Laybourne on UnsplashToday’s post is by author and book coach Deborah Ann Lucas.

I’m a writer who struggles to process information audibly and an artist who is not visual: I can’t absorb and remember the shapes I see. Instead, I’m an intuitive learner and writer, perceiving and processing the world through a different channel than most—kinesthetically. I learn best through touch and my sense of space. This could be considered a disadvantage. But I’ve turned it into an advantage by applying spatial concepts to see the shape of things in my writing.

In college, I gained creative confidence by making clay sculptures and learned about negative space in a drawing class. In the center of a circle of sixteen artists, a long-haired woman on a raised platform held a contorted pose. Nothing but a flush of circulation kept her nude body warm in the crisp, cool air. I hoisted my 30 x 40″ drawing pad onto an easel and began sketching her head, tracing the curve of her neck, around the arm, along the torso, and down her legs. At the edge of the paper, I had no room for her feet, and reached for my eraser to begin again, much like I do when writing.

My instructor materialized behind me. “Work with what you have.” He snatched the 2B pencil from my hand. “Anchor her in the setting to delineate her proportions.” He slid his thumb along the pencil, measuring with his arm straight. “See the shape in between to define the negative space. Measure the relationship between object and emptiness.”

I squinted, shifting from the model to his translation on my paper. He outlined the drapery to the curve of her shoulder, then her midsection to her flexed arm, creating shapes. Between these, I saw a central image emerge, one nestled in the setting—revealing the trees and the forest.

Connecting art lessons to writingYears later, when drafting my memoir, I recognized the parallels between writing and the visual arts. Through metaphor, I saw the connections. The naked model represents my vulnerability as I revealed my deepest fears and regrettable choices, a stark picture when rendered without context. The protagonist floated, unanchored in the frame of the story, when left disconnected from or haphazardly linked to the details of the setting, pulling the reader out of the scene before they could grasp what I hoped to communicate.

Using spaces between elements—formed by shared edges—will add continuity, complexity, flow, tension, and mood to the scene.

Using negative space—literallyIf negative space is a new concept to you, or is vague and hard to lock down, here are a few ways you might incorporate this effective tool into your writing.

The most basic key on your keyboard is the return key. I use it whenever there is a shift in who is talking in dialogue and create white space on the page. This may seem basic, but it is sometimes missed, so worth mentioning.

I hit the return key when I change anything: in dialogue to a different person; a shift to internal thought; a passage of narration or description. I will hit the return key twice when I switch to a new setting, or when I change the focus of the content, making another point. Adding this open space serves as a road sign, telling your reader something is about to change. It also gives them mental time to process the meaning within the story.

Varying sentence and paragraph lengthTo manage pacing, I vary the length of sentences and paragraphs, inserting blank lines or white space inside a chapter to create intentional negative space. This helps to avoid overwhelming or, in contrast, boring the reader with my writing.

The placement and the shape of text blocks can add white space to any page. See the space between the edges of the page and the block of text. Notice how different reading a page feels when it’s crammed with words versus when it contains only a sentence or a brief paragraph. All the possibilities in between alter the flow and the reader’s response. When reading, do you take the author’s cue to pause and process when there is extra space between paragraphs? And at the end of a chapter? Are you aware when editing how effective these breaks are when used with intention?

In All the Light We Cannot See, Anthony Doerr uses short chapters, from two paragraphs to a handful of pages, a classic example of using negative space to make a complex 531-page story more accessible. He controls our emotions through the ups and downs of this dramatic book.

Making spaceExcessive writing, like a busy painting, can produce content that is too much noise to sort through, making the central character hard to decipher. When we find this in our manuscripts, we can create negative space by breaking up our dialogue with internal thought, description, or a blank line, giving the reader a moment of quiet to let the power of the dialogue claim its full impact. An extra blank line between blocks of narration and dialogue facilitates rhythm and flow. Like in music, rests act as a breath, offering relief and adding suspense.

Added details slow the action and create connective tissue between primary elements, giving the reader time to sort out who is who, where they are, and the meaning beneath the surface.

Jon Gingerich in Writing in the Negative suggests how the writer might use empty space to contrast a quiet setting with the turmoil experienced by the main character. For example, in Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf uses a stream-of-consciousness narrative style, leaving spaces for readers to piece together the inner thoughts and emotions of her characters. The negative space in the narrative allows the reader to explore the complexity of the characters’ inner lives.

In “Hills Like White Elephants,” Ernest Hemingway draws us into the experience of a couple on their way to abort as they talk about anything else, creating a discord between their inner turmoil and the banality of what they are saying. The missing core of the story echoes with more power through what is left unsaid, using this negative space as a subtle reflection of their shared loss.

Leaving gaps in timeBy leaving gaps for ideas and concepts inferred but unsaid, you’ll invite the reader to fill these spaces with events and meaning from their own life experience. This leap over the chasm draws the reader into the story, reducing the space they must traverse, mentally and emotionally, to walk the path alongside or in the shoes of the protagonist.

In The Glass Castle, Jeannette Walls leaves gaps with hints of darker events that impacted her childhood, allowing readers to envision between the lines the full extent of the obstacles she faced. By using negative space, readers are engaged on a deeper level, yielding empathy and understanding. Unresolved tensions and unspoken truths help create a powerful and resonant memoir whose story lingers in the minds of readers.

New paragraphs and chapters are like a cut and fade to the next scene in movies. Where you cut and where you pick up the story tells the reader how far they must jump in time or space. A transitional sentence will make a connection smooth for your reader. Offering no transition into the next action makes it jarring.

It is for you to manipulate, depending on what you want the reader to know and how they experience your story. There are as many answers to this as there are writers.

In Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir, Natasha Trethewey uses jumps in time, from her mother’s murder at the hand of a former stepfather to later as she unravels what happened, to show us how it shaped her as an artist. She uses metaphor and dreams to inform her memory. The work is powerfully poetic and tragic; her compelling writing helped me traverse the time shifts without losing me.

When I reached the end, I wanted to understand how she had written a tragic personal story with such finesse and went back to analyze the journey I had taken with her. She uses short and long chapters with intermittent sections of dreams and remembrances. After long, dense paragraphs, she gives us a three-line open space, a pause before proceeding to the next scene, using this element of negative space often in each chapter as a break from the intensity, a place to ponder before.

Controlling what is in focusBy controlling what is in focus, you control the space as perceived by your readers. Like artists using a camera, writers can zoom in on their characters and zoom out to the immediate context or the setting, to compress or expand readers’ focus—startling them or giving them the space to take in details.

Aspects of these techniques can be applied to writing by adjusting the point of view. For example, writing in first person shortens the distance between character and reader, giving the scene intimacy and immediacy. The high energy of this closeness needs intermittent respites from the intensity. Switching to the narrator’s view of the setting opens up the reader’s viewpoint; a broader focus eases the tension. Deepening the depth of field uses negative space to give the reader time to absorb its details or see the scene from a new perspective.

In Schindler’s List, Steven Spielberg adds considerable visual texture to the shots by placing many objects between the two main subjects, shifting the viewer’s focus onto the space between. This deepens the story by focusing on connections between objects that hint or symbolize the undercurrents of the story he is building.

In writing, by highlighting the space around instead of on the primary character, you shift the perspective of a scene and the viewers’ perception of it. By focusing on objects, you can add context and metaphor, change the pacing, and enhance the mood to tell a unique story.

WeavingSymbolic objects woven throughout your scenes or chapters can be a powerful dimension of story. To consciously manipulate them, ask where and why each thread is popping up: Are they held or touched by the protagonist or other character? Or do you place them in the connective tissue between dynamic action—inside the negative spaces?

Using tools to help youIf you step back from your pages, you’ll see the shape of your narrative structure with fresh eyes, like when my art instructor measured with his thumb on the pencil. To accomplish this new perspective, you might try various tools in Word or ProWritingAid to see how you have laid out your building blocks of story.

Your awareness of negative space will give you a new window for understanding your writing and your reader’s response. When you manipulate spaces in between with intention, your readers will stay intrigued with its emotion, mystery, and ambiguity, reading every word to the end. And they will beg for more.

May 16, 2024

The Double-Edged Sword of List Building Promotions

Today’s post is by author Brenda E Smith.

I realized a lifelong dream when I self-published my first book in August 2023. I followed all the marketing advice I received about entering the publishing world, including creating a website and selecting an email service provider. On the last page of my book, I added a reader magnet meant to collect email addresses of enthusiastic readers who would enjoy receiving my newsletters. Like many new authors, my original email list numbered about 100, primarily family, friends and work colleagues. I had a long way to go to reach the limit of 1,000 addresses allowed by the free version of my email service provider.

Learning about list-building promotionsDuring the first few months after launching my book, I collected 100 more email addresses, but at that rate, growing a substantial list would require marketing outreach help. But who could help me? In November, it thrilled me to discover a well-known book promoter’s list building giveaways. Their two-week long promotions include genre specific bundles of 6 or 7 ebooks. To sweeten the deal, one entrant also wins a free Kindle tablet, its image prominently featured in the advertisement for each promotion.

Authors pay $50 to have their book included in a bundled promotion. In return, the promoter guarantees the author a list of at least 250 new email addresses, though sample results of recent promotions on their website boast of generating 1,000 or more addresses. It sounded great, and not too expensive, so I signed up for an action/adventure-themed promotion.

How do they collect list names?The promoter advertises giveaways through Facebook ads, their own reader email lists, and authors who share giveaway links on social media. On the contest entry page, the promoter requires all entrants to check a box indicating they agree to receive emails from the authors whose books are part of the promotion. This proactive opt-in is required by anti-spam policies of all email service providers. When the promotion period ends, the promoter randomly chooses three entrants to win the bundle of ebooks. One of them also wins the free Kindle.

Results of my first promotionInitially, I felt overjoyed to receive the email addresses of 250 readers who entered the giveaway. In two weeks, I had doubled the number of names on my list. When I imported the giveaway addresses, I created a unique group for them within my subscriber database. I promptly sent a welcome email giving them the option to get my book for free during an Amazon promotion the following week. They also received five newsletters over the following three months.

It’s so easy, let’s do it againWhen I signed up for a second, inspiration-themed list building giveaway in January 2024, the promoter sent 732 addresses to my quickly growing list. But adding these new addresses exceeded the number of addresses permitted by my free email account. To accommodate the new names, I reviewed and deleted addresses from the first action-adventure group that never opened any of the five subsequent emails I’d sent. It astounded me that nearly 75% hadn’t even opened the email offering the free ebook!

Violation of anti-spam notificationAfter culling out non-responsive emails from both the action-adventure promotion along with a few from other groups in my subscriber database, 870 names remained, including all the new addresses from the second list-building promotion. After sending a welcome email to the second group and two other newsy emails to the entire list, my email service provider notified me they had suspended my account because I had violated their anti-spam policy. This perplexed me because I’d added no one to my list that hadn’t proactively opted in.

Researching the suspensionImmediately, I replied to the investigator assigned to review my case, asking for an explanation. He told me I’d exceeded their limit for unsubscribes for the last email I’d sent and referred me to their terms and conditions. After digging deep into the minutia of the email service company’s anti-spam policy, I found a paragraph on account suspensions. It read, “We reserve the right to suspend your account immediately and start investigating your activity if your campaigns have a high percentage of spam complaints (more than 0.2%), bounces (more than 5%), unsubscribes (more than 1%) or very small open rate (less than 3%). If it turns out that you were sending emails without permission—we will terminate your account.”

I knew I had done nothing wrong while building my list. How could I control what people did once they were on my list? This punishment felt draconian.

How my unsubscribe rate got my account suspendedI opened and studied the analysis of my last campaign to 870 addresses. Twenty-five addresses had unsubscribed, 3% for that email. Because I had imported the email addresses from the list-building promotions as separate groups of subscribers, I could tell that all 25 unsubscribes came from those two promotions (along with four spam reports). But even worse, once again, 75% of the addresses from the second list-building promotion had opened none of the three subsequent emails I’d sent.

Confronting the book promoterStraight away, I contacted the promoter to question them about the high proportion of names who never opened any of my mails, and to notify them that the high number of unsubscribed addresses had resulted in suspension of my email account. I asked how they obtained these email addresses if 75 percent wouldn’t open a welcoming email about “December Deals,” including an offer to get my ebook for free that they didn’t win.

My analysis: many of the people entering the contest aren’t interested in the books. They only wanted a chance to win the free Kindle tablet. I got an apology and a promise to look into my complaint.

Convincing my email service provider to reinstate my accountMeanwhile, I had to prove to my email service provider that none of the unsubscribed addresses had been added to my email list without their permission. I sent them a link to the promoter’s giveaway entry page so they could verify a block had to be checked off by anyone entering the contest, agreeing to receive emails from the authors. They then agreed I had not violated their anti-spam policy, although I had exceeded their unsubscribe limit. Grudgingly, they reinstated my email account with the stern warning that if it happened again, they would permanently shut down my account.

Protecting my email listI went through and deleted all the accounts from both list-building promotions for fear that if just five more of the list-building addresses decided to unsubscribed in the future, my account would be shut down. The promoter’s director of global operations emailed me to thank me for my candid feedback and promised to continue to monitor the performance and impact of their promotions closely. I asked the promoter for a refund for the two list-building promotions, since I couldn’t trust that the addresses they provided had any value. They have not replied.

Lessons learnedI learned about list-building promotions the hard way and want other authors to avoid this potential pitfall. Many book promoters run these types of contests. When the prime attraction in their advertising is the shiny new ebook reader, they inevitably will attract entrants who are only after the grand prize. Despite checking the box to receive author emails, they may quickly turnaround and unsubscribe from author emails they receive (or worse, report them as spam).

Also, all email service providers set qualitative standards to prevent people from building email lists that deliver spam and clutter subscribers’ email boxes. I’ve discovered that other providers’ standards are less restrictive than my provider’s limits. It’s important that every author is aware of what their provider’s tolerance level is for unsubscribes, bounces, and spam reports.

List-building giveaways specifically hurt authors whose base email lists are small, because doubling or tripling their size from promotions, where the addresses are not people genuinely interested in their books, puts those authors at a higher risk of violating email service policies when those people unsubscribe. For authors with larger established email lists, unsubscribes from list-building promotions may not exceed the email service provider’s qualitative caps. Still, what author, regardless of whether their list is large or small, wants to pay for non-responsive addresses from promoters?

If book promoters are serious about helping authors, they must realize that featuring valuable non-book prizes might provide an incentive for the wrong type of people to enter their giveaways. Also, they must be diligent about monitoring the quality of the addresses they are adding to their lists, weeding out addresses that repeatedly enter giveaway promotions for every genre, so authors receive only addresses of bonafide readers interested in their book.

May 15, 2024

How to Write Compelling Inner Conflict

Photo by Alex Vámos on Unsplash

Photo by Alex Vámos on UnsplashToday’s post is by Angela Ackerman, co-author of the new second edition of The Emotion Amplifier Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Character Stress and Volatility.

Readers connect with characters who are true-to-life, so as we build our story’s cast, we want to ensure they think and behave as real people do. This is especially important when it comes to inner conflict as readers are exposed to a character’s personal struggles and insecurities. These moments are powerful points of connection, so how can we show a character’s inner turmoil in a way that reminds readers of their own experiences?

Psychology!

I know, you probably aren’t a therapist and that one class in college, well, it was years ago. Don’t worry, you won’t have to dive into textbooks to unravel the whys of behavior to put it on the page. Instead, you can pull from your own experiences with cognitive dissonance.

You may know cognitive dissonance as something else–the tension that arises when you feel torn between two different beliefs. The discomfort of examining your priorities when new information calls them into question. Doing or saying something that deep down you suspect—or know—is wrong.

Cognitive dissonance, the psychological discomfort caused by contradicting thoughts, perceptions, values, or beliefs is something we will experience many times over the course of our lives. This inner tension can arise from something small, like whether to tell a white lie to spare someone’s feelings, or something larger, like having to choose between family loyalty or the common good after discovering a sibling is behind a string of robberies.

Being in a situation where things don’t sit right or we’re not sure what to do is not a fun experience, so when we show our character’s dissonance, readers can’t help but relate and empathize.

In the story, our characters may try to ignore or suppress the distress they feel, but eventually it grows to the point where they must resolve it. But internal conflict is called conflict for a reason: the character is pulled in different directions and doesn’t know what to do. And when the right or best decision means a harder road, the choice becomes even more difficult to make.

Moments like this will activate the reader’s emotions because they know what it’s like to make hard decisions. Obviously, there’s pressure on the writer to show all of this well, and once again, psychology can lend a hand.

Using emotional reasoning to solve painful problemsInner conflict is hard to resolve as things are never black and white. In the real world, we apply emotional reasoning whenever we struggle, so we can show our characters doing this, too.

Emotional reasoning is where the character weighs and measures each factor related to their situation—their beliefs, facts about their circumstances, personal experiences, past teachings, the people involved, any possible consequences … the whole nine yards.

I’ll show you an example. Let’s say our protagonist Silva just discovered her best friend Claire is cheating on her husband, Rick. Claire begs Silva to keep this information secret, and normally, she wouldn’t share something told in confidence. But this? Staying silent doesn’t sit right. Silva has strong beliefs about fidelity and views an affair as the worst type of betrayal.

She hates the whole situation and wishes she could go back in time to when she was blissfully ignorant. Instead, she now has an agonizing decision to make—say nothing out of loyalty to Claire or stay true to her moral code and tell Rick.

Silva knows if she tells Rick, she’s nuking her friendship with Claire. But if she says nothing, she’ll struggle to be around her friend, not to mention look herself in the mirror, because keeping the secret makes her feel complicit.

To figure out what to do, she applies emotional reasoning by weighing and measuring the various factors around this situation.

For example, it might be easier for Silva to keep this information to herself if one factor happens to be that Claire’s husband isn’t a nice guy—say, if he’s verbally abusive or controlling. Silva might resolve her dissonance by telling Claire that his behavior is further proof it’s time to leave the marriage.

But what if Rick is a good guy, maybe even someone Silva considers a friend? In this case, keeping the secret means protecting one person by betraying the other.

Another factor could be whether the two have children. What if revealing the truth triggers a divorce and turns the family inside out? She will be responsible in part for that outcome.

As Silva grapples with what to do, she considers other factors, like how good a friend Claire is. She also tries to think back to a time when she kept the truth from someone, or if she’s ever felt as Claire does (needing love in a way her partner doesn’t provide). Another possible factor Silva would consider is if she’s ever experienced betrayal, especially the sort that would put her in Rick’s shoes.

Whatever factors are true for Silva in this situation, you can see how her deepest beliefs and values are being challenged. She must sort and measure to reason out what to do.

It could be that Silva concludes that:

She’s lost respect for Claire and their friendship might not survive, but despite believing the affair is wrong, she agrees not to tell Rick. Silence comes at the cost of her integrity, but she refuses to be responsible for unraveling their family.Her morals won’t let her keep Rick in the dark, and she’s upset Claire has put her in this situation. She decides Claire should bear the brunt of the emotional discomfort and delivers an ultimatum: Either you tell Rick, or I will.She doesn’t want to keep this secret, but she also doesn’t feel right delivering news that could break a family apart. If she continues to run into Rick, she’ll have to say something, so she removes herself from her friends’ lives.Difficult decisions usually carry a price tag—in this case, pain for either Silva or her friends. She doesn’t want to hurt anyone, but there’s no way to avoid it. And one way or the other, she’s being forced to sacrifice friendship, integrity, or both.

Emotional reasoning plants readers in the character’s perspective, helping them understand the why behind a decision. They get a private viewing of the character’s inner struggle and vulnerability, which fortifies the reader-character bond. And because readers have had to weigh and measure themselves, they know it’s a personal process. They may not agree with a character’s end decision, but at least understand the reasoning that brought it about.

Human psychology and its processes allow us to bring authenticity to the page through our character’s realistic emotional responses and behavior, so don’t be afraid to bring it into your storytelling.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, check out the new second edition of The Emotion Amplifier Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Character Stress and Volatility by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi.

May 14, 2024

5 Reasons You Should Consider Writing Your Memoir in Present Tense

Photo by Fallon Michael on Unsplash

Photo by Fallon Michael on UnsplashToday’s post is by author Gina DeMillo Wagner, author of Forces of Nature.

Amazon • Bookshop

Amazon • BookshopWhen my memoir Forces of Nature was on submission with publishers, one editor said she loved the story, but couldn’t get past the fact that I had written it in present tense. In her mind, I’d broken a universal rule: Memoir is about the past and therefore should always be past tense. I respectfully disagreed (and sold the book to a different publisher who shared my vision).

From the very beginning, I felt my story demanded to be told in the present. The memoir takes place in the aftermath of my brother’s sudden death and follows my quest for answers and understanding. The prose has an immersive quality as I navigate complicated grief, investigate his cause of death, and eventually find my footing and place in the world.

Still, present tense was a risk and a technical challenge. I couldn’t approach the narrative with hindsight, though I did achieve distance and clarity. I borrowed tools from my journalism training like datelines to orient the reader to time and place. I distinguished between myself as author, as narrator, and as protagonist. Throughout the writing process, I kept in mind several cinematic, propulsive memoirs I’ve read and loved that also used present tense. I knew it could be done.

Here’s the thing: The best memoirs are not simply a chronicle of events. They are vivid, nuanced, meaningful stories. And there are myriad ways to tell a story. Present tense is just one approach. It’s tough to execute and doesn’t suit every writer or every memoir (or every editor!). But here are a few reasons to give it a try:

1. It lends immediacy and intimacy.Memoirs are personal, but they should also be universal. You want your reader to drop into the story alongside you, and present tense is an invitation. It lends a sense of immediacy. It engages the reader and propels them through your story. They become your co-conspirator or fellow documentarian, emotionally invested in the plot of your life. In effect, you’re telling the audience: This is happening right here, right now, and you’re here with me in the midst of it all. Together, we’ll consider the plot and make meaning of it.

2. It mirrors the experience of grief and trauma.Anyone who has experienced grief or trauma knows that it never really goes away or becomes a thing of the past. Our nervous systems hold onto the sensations and emotions as if they’re happening in the here and now. Details and memories double back on themselves. They grip us in surprising ways. Since so many memoirs deal in grief and trauma, it makes sense that we would write about it in the present. It’s a technique that gives readers access to the interiority of pain and lays bare emotions on the page.

3. It keeps you rooted in scene.Maintaining present tense helps you avoid the boundless, blow-by-blow retelling of events: This happened, and then this happened, and then… Not to mention, without the distance of time, it can be easier to show rather than tell. There’s something visceral, almost electric, about sensory details when you read them in present tense. It keeps the author (and reader) grounded in scene.

4. There is plenty of room for reflection.One of the biggest arguments I see against writing in present tense is that it makes it hard to reflect on your experience or offer the kind of insight and exposition that makes memoir valuable. Yet, our perspective on life isn’t static. It evolves, and it can evolve on the page. The search for patterns and connections can happen in real time.

A reflective voice asks, “So what?” It reaches beneath the surface for deeper meaning. The narrator holds a mirror to herself and her experiences and looks for the truth of it, teases out the threads, finds the subtlety. And that can happen in present, past, or future tense.

How? In present tense, you can signal to your reader when you’re reflecting. You might offer little clues like brushstrokes: “Years from now I’ll realize…” or “In my memory, this is the first time that I…” It’s akin to breaking the fourth wall. Done sparingly, it allows the reader to come to the same realizations alongside you or even develop their own, which lends universality to your story.

5. You’ll learn to trust yourself as an author.You might try writing a draft in present tense and love it. Or you might hate it. It could crack the story wide open. Or in the end, it may not offer the flexibility you need or the structure to contain the story you want to tell. So be it. Even if you scrap the draft, I’m willing to bet your writing will improve thanks to this exercise. You may discover a sharpness, depth, and nuance that wasn’t there before.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1885 followers