Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 31

August 19, 2024

Cooking Up Success: The TikTok Personality Behind a Bestselling Self-Published Book

Every month, I compile three bestseller lists that showcase what books are currently selling through online retail, using Bookstat data.

Two of these lists focus on self-published books exclusively (print format and ebook format), and a third list looks at both traditionally published books and self-published books (print format), but excludes Big Five publishers and other major houses. I call it “Hidden Gems.”

All of these lists tend to put self-published authors front and center, authors who often miss out on appearing on national bestseller lists. Too often that’s because their sales are online-driven or ebook-driven, not because they don’t have sufficient sales. (For example, the New York Times won’t list a book if it’s sold and distributed only through online retail.)

On the July 2024 list, I noticed a new author and title I had never seen before: Matthew Bounds, author of Keep It Simple, Y’all. The book hit #2 on Hidden Gems, and #1 on the self-published print bestseller list.

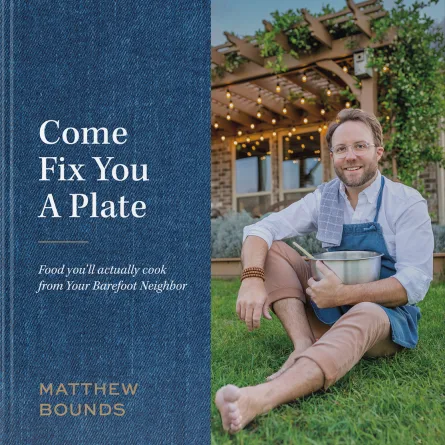

I immediately searched for Matthew Bounds online and saw that he has a combined following of millions across TikTok, Instagram, and Facebook—built in just a couple years. And I discovered that Keep It Simple Y’all is not his first book, it’s his second. He’s known informally as Your Barefoot Neighbor and is based in Gulfport, Mississippi.

I reached out to Matthew to ask if he’d be willing to talk about his journey and the publication of these two cookbooks. He graciously agreed.

So to start from the beginning, I gather from your social media posts that you started all this during the pandemic. Is that correct?

No, I was a little late to the game. All the people who kind of got popular during COVID started in 2020. I didn’t get started until 2022, it was about two years ago. Because actually, after the 2020 election, I was like, I need a break. And I completely deleted all my social media apps. I got rid of everything. I spent over a year just completely off the grid. I read a ton of books, did a whole lot of stuff for myself.

In spring 2022 a friend of mine was like, Hey, I started the TikTok channel for my French Bulldog. Can you go make a TikTok account so you can heart my videos and stuff? I was like, yeah, absolutely. So I went and I made a TikTok account. And that was the first social media account I had made since I got rid of everything. And it did not take me long to get the itch.

What did you start posting on TikTok?

I was posting DIY content, projects I was working on around the house, yard work. I was building a fence, so I was posting footage of that. I was goofing around, doing the trending audio and stuff.

I was also learning to cook. That was my project during the pandemic. I was 39 years old, and I had never learned how. But I had not planned on having a cooking channel, because I can’t cook.

One night, I posted what I was making for dinner, and a few people seemed a little interested. I didn’t even talk through it. I literally just got shots of what I was doing and put music over it. So I did it again. And then I started doing voice overs, saying what I was doing. A few of those popped off and went really viral. So I was doing that more and more.

Your handle is Your Barefoot Neighbor—has that always been the case?

Yeah, when I started that first TikTok account, I had to come up with a username, and I wasn’t officially planning then. Again, I was just getting on there to support my friend. I didn’t know if I was going to make content or not, but I guess I had the foresight to know that if I wanted to make content at some point, I needed a good handle. It was gonna be yard work and DIY, and I just wanted something really casual, approachable and fun. And so I came up with Your Barefoot Neighbor. But now that I cook, people think it’s a play on Barefoot Contessa. It’s not, but it kind of works both ways, I guess.

Tell me about your first book, Come Fix You a Plate—how did that happen?

Last February [2023], a friend of mine called me and she said, “Hey, there’s this printer-publisher, and they’re wanting creators to sign on. They’re gonna make a book for you, I’ve already done one. I told them you would do it. I’m not asking, I’m telling you, you’re good. You’re going to do it. They’re going to call you today, just say yes.” And I was like, All right, cool, yeah, let’s do it.

This is the company Found?

Yeah, they called me and we wrote it in like six weeks. In May 2023, that one launched, and that’s when I got serious. I was like, Okay, I guess I’m officially a cooking show. So, that’s what I did all last year and then this year.

Six weeks to publish a book, that is blazingly fast. Did you just take existing recipes that you had, or did you have to create more on the spot?

Found told me they wanted 50 recipes. I literally got off the phone with them, and I just sat down and started writing everything. There was no theme. It was just, what have I made that’s going viral, right? What’s easy that I know how to do?

I called my mom. I said, Hey, give me your pound cake recipe. There’s a recipe of my mother-in-law’s in there that she always makes. It was a lot of stuff that I already knew. And there were a few fillers because I gotta get 50. Like the stuffed bell pepper recipe. I’m not a big stuffed pepper fan, but, recently, for some weird reason I’ll go through phases where I’m just getting all these people commenting about the same thing they want. And all these people have been commenting and wanting a stuffed bell pepper recipe. I don’t eat stuffed bell peppers. So I was like, OK, you know what? It’s going in the book. I’m gonna come up with a stuffed bell pepper recipe.

There were a ton of typos, because [Found] is more of a printer than a publisher. The appeal is you get it out quickly, but you better double-check yourself, because they’re not editing. They’re going to copy what you send them, and they’re going to put it in the book, and it’s going to go out. I mean, they really have a good model for social media, because social media is fast. If you’re on the upward trend and you’re climbing and you got videos going viral, you know, it’s great, because they can get a book out as fast as you can send them material, and you can ride that wave. So it worked for me at the time. It was perfect.

They send you regular sales reports?

I get one every two hours, so it’s pretty cool. I’m very much a numbers person. When I’m doing big pushes, or I’m trying to hit a goal, it’s really cool to see real-time numbers coming in.

If you wanted to do this book on your own, could you? Do they take any rights?

The contract was for 12 months. After that, you can just take it and go do what you want with it. So I’m past my year mark. At any point, I can just pull my book and redo it myself if I want to.

Found doesn’t sell any place except through their site, correct?

Yeah, that’s one of the big reasons I did the second book myself. Found was great for me when my following on social media was one-tenth of what it is now, so I was pretty much a nobody. They gave me a shot, and that was really great of them. For me to have had such a small audience, and I’ve sold 80,000 copies in a year, I mean, that’s outstanding considering that it’s only available at that one link. [Editor’s note: Matthew later emailed with a more accurate figure: 78,634 copies sold]

Yes, it is! For your second book, Keep It Simple Y’All, that’s just you self-publishing?

This year came around, and I’m literally 10 times the size [on social media]. And I’ve done a TED talk, and I get invited all these places, I go speak at events. I’m always meeting people, and they’re like, “Oh, you have a cookbook. What’s the name of it?” And they open up Amazon, and I’m like, Yeah, so you can’t get it on Amazon, you can only get it at this one place. And I got really tired of having to explain it. I need something that’s really easy for people to find. And so I did it myself.

How many have you sold?

I don’t know the exact number, but between 35,000 and 36,000. We’ve done almost 6,000 in August so far. That’s not too shabby for me. I don’t know what industry standard is, but for me, I’m over the moon.

That puts you at the top of the traditional industry, too! I notice there have been some bad actors mimicking your book or trying to trick people into buying a book that’s not actually yours. That must be very frustrating.

It’s extremely frustrating. It really got to me at first, but I kind of hit a point where I’ve talked about it so much. I put direct links to my book, everywhere, and I’ve posted it a million times. If someone gets scammed at this point, it’s on them. I can’t be responsible for every single purchase. If you look it up on Amazon, it comes right up and it’s got 600 reviews, so I feel like any reasonable person should be able to tell.

There’s a ton of fake Facebook pages that impersonate me, and I do my best to keep up with everything. But at some point people just have to use some common sense. Obviously I am not going to be messaging you, asking you to go buy $125 in Walgreens gift cards. Like, why would I do that?

Do you see much difference in the type of audience you’re attracting on each platform? Stereotypically we say Facebook is older, TikTok is younger. Do you see that come through?

Yeah, my TikTok analytics say that my average viewer is between 34 and 44 or about my age. They seem to trend younger or more progressive, more technologically savvy than my Facebook crowd. On Facebook, they’re the ones where you have to hold their hand and explain, “This is a scam.” The TikTok crowd just seems to get it, they know how to differentiate.

Is this now your full-time living?

It is, I went full time a year ago, last August. I took a two-week break from my job. I was an insurance adjuster, and I was on the customer experience side of it, and I was in between projects. So my boss was like, “Hey, if you want to go focus on your social media for a couple weeks, and then just call me and let me know how you feel.” And on day one, I was like, I’m never going back to work.

Do the books make up a good portion of the income? Or is it gravy?

The books are definitely bread and butter. The books are the biggest part of my income. My day-to-day money is mostly social media income, Facebook money, TikTok money, sponsorships and stuff like that.

I haven’t had time to watch your TED talk, but I was really intrigued by the title of “The Recipe for Aggressively Positive Online Communities.” It’s obviously a philosophy that’s guided you and has led to success. Could you give us the one-minute version of that talk?

The recipe for aggressively positive online communities started out by saying, “Give me a stick of butter and a casserole dish. In less than five minutes a day, I’ll build an active, engaged online community.”

The whole talk is about how social media is what you make it. And if you are determined to have a positive experience, you will attract a positive audience. And there’s also a bit in there where I talk about how I’ve been called an aggressive, swearing Mr. Rogers. And I really love it. I might be kind, but I’m not always nice, and I do cuss a little bit, and I’m very quick to set the tone and tell people what the boundaries are. I think that’s really important. You do have to stand up and kind of snap back at people a little bit and let them know what will and will not fly.

Parting advice?

If anybody is reading this, just do it. It’s never going to be perfect. It’s never going to feel like the right time. You’re going to think of 100 other things you should have done differently after you hit the publish button. But just get it out. Just get it out there, because it’s not doing you any good sitting on your computer. Upload it, get it out there. It’s gonna have typos. You misspelled something, Amazon’s gonna send out literally thousands of copies that are missing pages 72 and 73, but it’s out there, and you don’t know who’s gonna see it, or who’s gonna hear about it or read it or want something more from you. None of that’s going to happen if you don’t just get it out there.

Thank you so much, Matthew.

August 15, 2024

Is It a Book? 5 Ways to Test Your Nonfiction Book Idea

Today’s post is by Bethany Saltman and Fran Hauser, book coaches and co-hosts of the podcast BOOKBOUND.

Writing and publishing a nonfiction book is a big investment—of time, energy, and often money. In our work with authors, we find that people often approach the process with passion and ambition but without any sense of what it really takes to get the attention of an agent or editor, especially in today’s crowded market. That’s why we’ve created these five ways to test your book idea.

1. Do you have a sticky, counter-intuitive idea?It’s not enough to have a good idea. A successful book is an idea about another idea, and the more surprising or “counterintuitive” the better.

We use the seed sentence from the writing teachers Marie Ponsot and Rosemary Deen: “They say _____ but my experience tells me _____” to help writers discover their counterintuitive ideas. You should be able to identify a book’s sticky idea or even the “They Say” right in the title.

These three books make it clear that they aren’t just sharing a big idea with their readers, but that they’re going to make us think differently about something:

Real Self Care: A Transformative Program for Redefining Wellness (Crystals, Cleanses Bubble Baths not Included) by Pooja Lakshmin, MDHow to Love Someone Without Losing Your Mind: Forget the Fairy Tale and Get Real by Todd BaratzThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good Life by Mark MansonDoes your book have a sticky, counterintuitive idea? If not, don’t worry. Try writing ten “They Says” and see where it takes you. This will take some time, and it’s worth it because without a strong idea, you don’t have a book.

2. What kind of publishing path is right for your book?When new authors come to us, they often have an idea in their minds about what getting their dream publishing deal will look like: an agent, a big advance, and a book tour. While they don’t always know it yet, theirs is a fantasy about getting a traditional deal with a Big Five house (Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster, Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan), and, unfortunately, it is usually a fantasy—not because their book isn’t a great idea, but because they don’t have the “platform” (i.e., reach) to justify the investment from a Big Five publishing house. Also, book tours are a thing of the past, even for many Big Five authors.

The great news is that there are many publishing paths available. When we work with authors, we invite them to align their goals with their publishing path. Here are key questions to consider.

Do you already have strong readership or reach—and want a chance at a national bestseller list? Big Five publishers look for nonfiction authors who are already engaging their target readership, then build on the foundation that’s already been created. While publishers help secure nationwide retail distribution and mass media attention, they still rely on authors to get the ball rolling. A significant platform is often a requirement if you want to land on the New York Times bestseller list. Note: you’ll need an agent to be considered by a Big Five publisher.Are you a recognized authority or expert in your field, but don’t have much reach to your potential readership? A traditional publisher outside of the Big Five may be a good fit, and that includes university presses. They may be more focused on the quality of your writing, ideas, or scholarship, especially if they already know how to reach the target readership for your book. They often have the same strengths as the Big Five, but many do not require an agent.Do you expect to sell the book directly to your readership, at events, and/or through online retail? Then you stand to earn much more money via self-publishing if you’re willing to learn the process and assemble whatever talent you need (e.g., editing, design, and production help).Do you want to retain as much control as possible over the final book, but have no desire to manage the publication process? Then you may want to consider a paid publishing service or hybrid publisher to get your book to market if you have the money to invest (costs are typically in the low five figures for high-quality, industry professional results). If bookstore distribution or physical retail distribution is important to you, look for a publisher or service company that has traditional distribution through Simon & Schuster or Ingram Two Rivers.For much more information on the key publishing paths, see this post from Jane.

3. Is there room for it?Let’s face it. Truly original ideas don’t come along every day. And that’s OK! Finding your spot on the shelf is a matter of finding that sweet spot between “proof of concept” (books like yours that have done well) and “white space” (how your book will be different). One way to discover that sweet spot is to hone in on your unique perspective.

One of our favorite case studies for finding room in a crowded market is Bonnie Wan’s bestselling book The Life Brief. Wan is the head of brand strategy and partner at the storied marketing agency Goodby, Silverstein, and Partners. Ten years ago, anguished by the choices she’d made in her life and dangerously close to a divorce, she had an epiphany: her expertise was in helping her clients discover what really mattered about their brands by writing a creative brief. So, she decided to try writing a creative brief about her life. As she puts it, “I was applying the craft of what I had mastered in advertising, but toward very different things.” And voila! Wan found room on one of the most crowded shelves in any bookstore—self-help—by writing a book only she could write.

Here are some other ways to differentiate your book from others like it:

Voice & perspectiveOriginal/counterintuitive way to look at somethingA new piece of researchA fresh form, i.e., adding photos to prose, etc.When asking yourself if there is room for your book, the answer is definitely YES! You just have to get smart about how to position it.

4. Who are you writing for?While it’s natural to want to write a book that will reach the masses, the irony is that the best way to reach a big audience is to write to one specific person. In marketing, this is called your Ideal Customer Avatar (or ICA). We call this person your muse.

We define your muse as the person whose life will change after reading your book. Ideally, your muse is a real person you know, though it can also be your past self. Once you decide who you want to write for, you can explore what your muse really needs by asking about their PPQ: Pain, Problem, Question.

For instance, in Bethany’s 2020 book Strange Situation: A Mother’s Journey Into the Science of Attachment (Random House), her muse was her past self, an insecure young mother.

Her PPQ was:

Pain: What is her core discomfort? The thing that keeps her up at night? I feel like the worst mom in the world.Problem: Because of her pain, what is her central problem? I am so busy beating myself up, I am missing out on my baby’s love (which would actually help soothe my pain).Question: Based on her problem, what does she want to know? Is this normal? Or is there something really wrong with me? And what can I do about it?Keeping your muse in mind is incredibly helpful when writing your book for a couple of reasons. One: writing for one person makes your writing very specific, which is the mark of all strong prose. The other is that connecting with your muse and your desire to help them with their PPQ keeps you engaged in the writing and publishing process—especially when faced with the inevitable challenges and rejections. When you write your book in service to a specific person, you’ll stay inspired even when it’s hard.

5. Are you the one to write it?If you want to write and publish a nonfiction book, you’ve probably heard—perhaps with a shudder of fear —the word “platform.” An author platform refers to your experience and network expertise in the space you are proposing to write about. It’s the thing agents and publishers look for to validate that you are a credible source on your topic (and, of course, they’d like you to leverage your platform to sell books).

And while people often look to social media numbers as an indication of their platform—and certainly when you’re looking at Big Five publishers, numbers are important!—there is much more to it.

We like to think of “platform” as your “author-ity.”

When pitching your book, one of the most important questions you’ll have to answer is why you’re the one to write it. So, in answering that question, consider all of the following:

Education and degrees, including certifications, prizes, and honorsWork experience + major wins at workNetwork: who do you know, and will they endorse and/or amplify your book?Social media presence. And PS: Engagement matters just as much as followers, if not more!Publications and bylines, including all the writing you’ve done professionally, and don’t forget about published academic researchNewsletter (e.g., Substack) and email list—again, engagement, engagement, engagementUnique personal experience with your topicAfter testing your book by asking yourself these five questions, if you discover that YES, your idea really is a book, congratulations! The great news is that now that you’ve gone through this process, you’ll be in a great position to write your proposal, which is your next step. And if not, that’s great news, too.

Books are wonderful tools to share your ideas and insights, but they certainly aren’t the only ones—perhaps your work is better suited for a podcast, a Substack, or a class, or all of the above! In any case, by testing your idea, you’ll be ready to share your work with confidence and true authority.

Note from Jane: Twice a year Bethany and Fran offer a BOOKBOUND Accelerator for aspiring authors who want to turn their great ideas into standout books.

August 14, 2024

Choosing Story Perspective: Direct Versus Indirect POV

Photo by Marc-Olivier Jodoin on Unsplash

Photo by Marc-Olivier Jodoin on UnsplashToday’s post is by editor Tiffany Yates Martin. Join her for a three-part webinar series POV Mastery, starting on Wednesday, August 21.

You’ve developed your central story idea, worked out your plot and stakes, know your characters as deeply as close friends.

But what’s the most effective way to tell their story?

Point of view is rarely the first storytelling element authors focus on when creating their stories, but it can arguably be the most important. Strong, clear, well-chosen point of view serves as a powerful guiding force for readers: inviting us into the story, setting the tone for the journey, and subtly directing how we experience it and how we react.

Point of view is your story’s voice and its vibe, an element invisible to most readers, but which permeates their entire reading experience. Choosing the right one and executing it well may be among the single most challenging and yet most impactful elements of your entire story. Poorly chosen or unskillfully executed point of view can leave readers lost, confused, or just plain detached, unlikely to finish your book.

So, you know, no pressure!

Let’s do a quick review of the various points of view, then look at a key distinction among them to decide which might best serve your story.

Direct and indirect POVWhile there are three main categories of point of view—first person, second person, and third person—in today’s publishing market two are most prevalent: first person and third person. (There are always a few outlier novels written in second person, but they tend to be on the rarer side, so we’ll focus on first and third.)

Of the four POVs most commonly encountered in today’s publishing market, they can be broadly summarized as a choice between direct and indirect point of view.

First-person (“I/me”) and deep third (he/she/they or him/her/their) are more direct perspectives. The narrative voice is that of a character in the story, usually (but not always) the protagonist. Readers live the story directly through their firsthand, immediate perspective, and the narrative is written in the POV character’s voice.Omniscient and limited third can be characterized as indirect perspectives, where there is a separate narrative voice that is not that of the character, but has varying degrees of narrative distance from them.Omniscient point of view is the all-powerful “God” voice, able to see and know anything, go anywhere, travel in time, etc. It’s privy to any character’s thoughts and reactions, but only as an eavesdropper who can report on what they observe. Readers are not privy to the characters’ direct experience.Limited third is confined to the purview of a single POV character at a time. The narrative voice can see and know and report on only what is within that character’s perspective, although it is separate from the character and as such can “notice” things within the scene that the character can’t, like someone standing behind them. As with omniscient POV, limited third has access to characters’ thoughts and reactions, but only as an observer, not directly in their immediate experience—and in this case, only with the single POV character of the scene.For a deeper explanation of these POVs, see Picking a Point of View.

Thinking of the points of view in these two categories—direct and indirect—is a great frame of reference for considering which might best serve your story and you as an author. Each has benefits and challenges that may determine what feels most comfortable for you, what best suits the story’s genre and feel, and which offers you the perspective and narrative power that allow you to tell the story as effectively as possible.

Direct POVFirst-person and deep-third POV can create a strong connection between reader and character, but they also come with certain demands and risks. The deep intimacy of these voices requires profound character development, and can risk a myopic, navel-gazey feel that can compromise momentum with too much interiority (i.e., too much thinking, not enough action).

Direct points of view offer all-access passes to your characters’ immediate perspective. That means there’s no separate narrative voice: the character is the narrator, even in the slightly artificial remove of he/she/they pronouns in deep third. (For more on this sometimes tricky perspective, see Is Deep Third an Actual POV?)

That means every single development in the story must be framed through your character’s firsthand experience of it: their thoughts, reactions, emotions, what they make of things, how they are affected, how it impacts their behavior, etc.

All good stories require keen character development, but with direct POVs authors have to develop an especially comprehensive, minute understanding of who the characters are: their upbringing and how they were shaped by it; how they talk, what and how they think, how self-aware they may be, and how much of their true inner selves they share; their ideology, frame of reference, assumptions and illusions.

You must anchor yourself as the storyteller firmly within your POV characters’ immediate perspective: see through their eyes, think their thoughts, feel their feelings—and the narrative is filtered directly through their frame of reference.

The characters’ blind spots are also the narrative’s blind spots, which can be somewhat limiting for you as the storyteller, but can also offer you opportunities to create heightened suspense and tension by using this as a device to conceal story elements from the reader.

Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl builds much of its suspense this way in its first-person POVs, based on what Nick and Amy each know and don’t know in their constant cat-and-mouse game. Liane Moriarty uses deep third to similar effect in The Husband’s Secret, availing herself of each POV character’s limited perspective to create suspense, build secrets and unknowns to a climactic reveal, and slowly paint the full picture of the story one brushstroke at a time.

In determining whether direct or indirect POV is a better fit for your story, it’s also worth considering its genre, as well as the “feel” you want the story to have, your narrative approach. Perhaps because of the lack of a separate narrative voice, direct POVs may suggest a more casual feel to readers, less formal—as if we’ve been invited right into the character’s reality, rather than having it shown to us by a “gatekeeper.”

Any genre can be told in any POV the author chooses, but direct POVs tend to predominate in those where plunging readers directly into the characters’ perspectives creates intimacy that can heighten the reader’s engagement and their identification with the POV character(s), like young adult, mystery, women’s fiction, and romance.

Indirect POVLimited third and omniscient, the more indirect points of view, allow the author a greater field of vision, a chance to tell the story through a wider lens. They may offer you more storytelling freedom—especially in the limitless perspective of the omniscient voice—but can also readily lend themselves to fuzzy, uncertain, or slipping POV that can leave readers feeling disoriented, confused, or removed.

Indirect POVs can risk prioritizing story action over character development and arc. With indirect POVs, authors must be especially careful not to simply describe or generalize story events, but to create a sense of immediacy and intimacy, despite that layer of narrative remove.

And because they are reporting on characters’ experience rather than directly sharing it, these removed perspectives can risk feeling lifeless and distant, full of emotive “tell” that may leave readers unaffected: “She collapsed in tears, sobs tearing out of her mouth.”

Because readers are deprived of firsthand access to the impact of story events on the characters, the risk is that we don’t feel the actual emotions of the story, just dispassionately observe how they manifest in the characters. If in direct point of view the author can let readers feel and experience the character’s emotions, in omniscient and limited third the challenge is to evoke it in them.

That can be more difficult from the narrative remove of these perspectives. You have to find ways to open the window into the characters’ inner life without breaching the boundary of their direct perspective—reporting on it rather than plunging into it.

The benefit to these more removed perspectives, though, is that readers can know more than the characters do, even about themselves—which can offer you as the storyteller opportunities to heighten suspense and tension with that juxtaposition, and deepen the story’s emotion and impact.

Ann Napolitano takes advantage of this in the omniscient Dear Edward, when readers know the passengers in the “before” section will all be killed save Edward when their plane crashes, but the characters have no idea. Bonnie Garmus does the same with limited-third POV in Lessons in Chemistry, for instance when readers know Calvin is dead before we see the news being broken to Elizabeth.

Because indirect POVs aren’t tethered to characters’ immediate experience, one of the author’s constant challenges in these perspectives is to orient the reader and keep their feet firmly planted in the story’s perspective. We need to understand the narrative viewpoint—the lens through which the narrative voice is observing the story events—without feeling as if the “camera” is swinging crazily around the room.

Indirect POVs entail a separate narrative voice, so they also require development of this added element of the story, in addition to developing each character’s distinct voice.

The narrative voice may reflect the feel of the story to help create the story world, as in many historical novels, where the language and syntax might reflect or evoke the sensibilities of the period. It may be an objective invisible storyteller, a neutral camera panning across the story’s panorama, as in Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half. Or it may establish a definitive “presence” or perspective from which the story is being related—as with Douglas Adams’s Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, which is ostensibly drawn from a self-referential guidebook by the same title, or the unusual first-person omniscient voice of Death in The Book Thief, or Yunior in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.

As with direct POV, any story can successfully use indirect POV, but these removed viewpoints lend themselves well to genres where broader perspective is useful, and the story’s feel may be less informal and chatty: “literary” or upmarket fiction, science fiction and fantasy, action/adventure, police procedurals. It can also work well in suspense/thriller and horror.

POV consistencyStories may incorporate both direct and indirect POVs—say, one story line in deep-third POV and another in limited third, as in Shelby Van Pelt’s Remarkably Bright Creatures.

But some stories seem to flit between both within the same sections of the narrative. This can be the most confusing use of POV, because these stories seem to breach the boundaries between POVs in ways that can easily risk disorienting readers, creating a weak or unclear narrative perspective, or head hopping.

Delia Owens frequently jumps between omniscient, limited third, and deep third in Where the Crawdads Sing, for instance. Kevin Kwan rampantly leaps into direct POV even within indirect limited or omniscient sections of narrative. Even the venerated Jane Austen often blurs the lines between direct and indirect POV.

In trying to pin down the POV “rules” in stories like this—which may play fast and loose with them—authors can often feel confused about how to use POV consistently and clearly.

As with so many elements of storytelling craft, though, it’s not how well you follow the “rules” that determines how successful and effective readers may find your story, but whether or not they engage and invest in it. The only real rule in writing is, if it works, it works. And that’s often a subjective determination, heavily dependent on how clearly the author establishes the story’s perspective not just section to section, but even line by line.

Regardless of which one you’re using, POV is most successful when it doesn’t draw attention to itself or to the author’s hand.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us for a three-part webinar series on POV Mastery. You can enroll for a class specifically on direct POV, indirect POV, and/or Mixed POV—or register for all three with a discount.

August 13, 2024

How I Went From “Big 5 or Die!” to Ecstatic Self-Published Author

AI-generated image (ChatGPT): a cozy sunlit home which is decorated for a party. On the dining room table is a sheet cake decorated with the author’s name and book title.

AI-generated image (ChatGPT): a cozy sunlit home which is decorated for a party. On the dining room table is a sheet cake decorated with the author’s name and book title.Today’s post is by author Denise Massar.

When I started writing my memoir, my publishing goal was Big Five or nothing. I pitied indie authors as also-rans. Anyone could self-publish. Where was the clout?

I had not completely unrealistic dreams of being interviewed by Matt Lauer on the Today Show. (Yep, that’s how long ago I began writing my book.) I imagined being interviewed by Terry Gross on Fresh Air. I dreamed of a book launch party with white twinkly lights and a cake with my book’s cover on it. I wanted my editor to take me to lunch in Manhattan.

I thought I was on my way in spring of 2020 when my book went on submission. My agent, Jacquie, received exciting feedback—one editor wanted audio rights if we could sell print rights somewhere else. Another said she loved my book and pitched it at their editorial meeting but couldn’t convince the rest of her team. That one hurt. A New York publishing house sat around a table and debated making an offer on my book?! While I was what … cleaning the litter box? Astonishing. But ultimately heartbreaking.

Five months later, we ran out of editors to pitch, and my book died on submission.

Amazingly, I got a second chance. Because my book was on submission during the earliest months of the pandemic and we’d received positive feedback, Jacquie thought it was worthwhile to wait a year, let the incestuous (her word, not mine) world of publishing do its thing, see where editors landed, and give it another go.

So, I went on sub again.

And my book died on sub. Again.

I was—offended is truly the best word here—that landing an agent and going on sub didn’t guarantee a book deal. I never considered that my manuscript would reach 50 editor inboxes and not find a publisher. I thought “on sub” was a one-way trip; I didn’t know my once-impeccably-dressed-ingenue of a manuscript could boomerang back to me, wearing a pit-stained white T-shirt with “I’m going to step aside on this one…” Sharpied across her chest.

My agent changed jobs and let me go.

A successful mentor in the publishing industry said to me, “I think your book’s a university press book.”

And I was like, Yes! It’s memoir! It addresses the social issues baked into adoption like racism and classism! My book is totally a university press book!

While it did feel like a considerable step down from the Big Five dream, it was a respectable one. I could still go around throwing out the phrase, “My publisher said…”

Around this time, I found a lump in my neck. Three different specialists said that it wasn’t cancer and because the tumor was lodged between my carotid artery and my jugular vein, it was better to get annual scans to keep an eye on it than to remove it. But an endocrinologist—whom I didn’t trust because she was so young—ran some blood work that revealed I had a genetic mutation, and that, actually, the tumor would turn into cancer. (That newly minted doctor I didn’t trust probably saved my life.)

Things got scary fast. My previously unfazed surgeon was ordering PET scans, stat!

I spent 10+ hours in the bowels of an MRI machine wearing a Hannibal Lecter-like mask to keep my head still. And when you’re in an MRI machine wondering if all of the beeps and bangs and machine-gun-like rat-a-tat-tats of magnetic imagining are going to reveal “tumor characteristics” consistent with malignancy, the very last thing in the world you give a f—k about is Matt Lauer.

It was agreed that the tumor had to come out before it turned into cancer if it hadn’t already. It would be major surgery with a four-week recovery.

One week post-surgery I got the lab results: the tumor was benign.

Quietly healing throughout February 2024, I mostly thought about how happy I was to be here. That I’d been given a pass to keep being here. But, slowly, throughout the spring, my mind eased out of survival mode and I thought about my book: What did I want as an author? What were my publishing goals now?

I knew exactly.

I wanted my kids to see me finish the job. When I started writing Matched, they were five, three, and newborn. They’ll be 16, 14, and 10 when my book publishes. They’ll have dreams of their own threatened by failure, family obligations, work responsibilities, health issues, and wavering confidence, but if they want to achieve them badly enough, they’ll keep going. I wanted them to have a model for what that looks like.

I wanted to hear from people who read my book—readers touched by adoption, readers who’d also searched for secret biological relatives—anyone who connected with my story and felt inspired to reach out. I got a hit of that drug when an essay I wrote for HuffPost in 2023 went viral. In it, I wrote about caring for my mom while she had terminal cancer. I talked about how sadness wasn’t my overriding emotion; though I loved my mom deeply, my primary emotion was stressed-out. The day the essay ran, I received hundreds of Facebook, Instagram, and email messages, and they all said: Same here! Me too! I thought it was just me!

And I still wanted a launch party. I grew up reading about the literary fetes of the 1990s and couldn’t help but imagine my own. The same mentor who’d encouraged me to go the university press route (they all passed on my book, too) helpfully reminded me that even if I’d gotten a book deal, as an unknown debut memoirist, I wasn’t gettin’ a party anyway.

So, I’m throwing my own twinkly, joyous celebration. The book cover cake has been ordered.

The snobby writer I was when I first began my author journey in 2014 would’ve never believed that she’d end up truly ecstatic to be self-publishing her book in 2024. Perspective can’t be rushed. I’m proud of my path from “Big Five or Nothing” to “War-Grizzled Self-Published Author.”

This week, at my launch party, my kids will hear me talk about how hard this journey was and how happy I am that I kept going. I’ll dance in the night air with family and friends.

I’ll receive messages from fellow adoptees saying they had to fight to see their birth certificate, too. Or that they also reunited with their birth mom. Maybe a hopeful adoptive mom will message me saying that she’s still searching for her baby, wondering if it’s ever going to happen for her. And I’ll sit at my desk in my pajamas and reply to every single one of them.

If you’re somewhere in the murky middle of querying, or your book died on sub, or the whole mess is in a goddamn basket somewhere, take a rest if you need to. But then keep going.

Take out a pen and make a list: What do you really want to get out of publishing your book?

Amazon • Bookshop

Amazon • BookshopCan you make it happen? Do you need to be traditionally published to do it?

Maybe you want to do a reading, or a signing, or to see your book in your local library or a bookstore. You can do all of those things as an indie author!

It’s not about Matt Lauer (or Hoda & Jenna), or even Terry Gross.

It’s about holding your published book in your hands. It’s about your story finding your readers, whether 30 or 30,000, and the human connection that your words will spark. It’s about celebrating with the people who were there for you all along.

And you don’t need anyone but yourself to make that happen.

August 8, 2024

When It Comes to Characters We Love, Vulnerability, Not Likeability, Is Key

Today’s post is by regular contributor Susan DeFreitas (@manzanitafire), an award-winning author, editor, and book coach.

Some writers believe that their protagonists must be likeable in order for readers to care about them.

And of course there’s some truth to that, which is why screenwriters adhere to a formula called Save the Cat: Having your protagonist do something kind or admirable or just generally awesome (like saving a cat who’s stuck up a tree) is indeed one path to your reader’s heart.

But the literary world is full of so-called unlikeable protagonists—the sort of people who not only fail to save the cat, but might have run it up the tree in the first place—that readers nevertheless care a whole lot about.

In fact, making your protagonist too good, paradoxically, is an excellent way to make your reader not care about them at all.

Not only because such characters don’t ring true (we all have our foibles and flaws) but because, generally speaking, we don’t turn to fiction for stories about perfect people.

What really makes us care about fictional people are the same sorts of things that make us care about real ones: understanding their soft, squishy underbelly, otherwise known as their vulnerabilities.

Here are three different types of vulnerabilities that will pave a trail straight to your reader’s heart.

1. InsecuritiesWhat does your protagonist hide, and why? What are their weak spots and insecurities?

In Elizabeth Strout’s novel-in-stories Olive Kitteridge, the titular character is a cantankerous old gal who doesn’t care what anyone in town—or even her own husband—thinks of her.

But the person Olive loves most in the world is her son, Christopher, which makes him a vulnerability for her—and when she overhears Chris’s new wife making fun of her dress at their wedding, and implying that Olive will be a difficult mother-in-law, it cuts Olive to the core.

Up to this point in the novel, we’ve seen Olive act in all sort of atrocious ways to people. But no matter how much we’ve disliked her thus far, at this point in the story, our hearts crack open for her.

Why? Because this cutting comment is one aimed straight at her squishy underbelly, which we might think of as the missing scale in Olive’s armor—her insecurity over Christopher’s love. Because if the person Christopher has chosen to spend his life with thinks so little of Olive, perhaps she’s losing his love.

2. FearsWhat is your protagonist afraid of? What is their secret fear?

In Kate Racculia’s YA mystery Bellweather Rhapsody, one of the protagonists, Alice, is established up front in a way that’s clearly unlikeable: She’s a 17-year-old drama queen, so sure of her eventual rise to fame as a singer that she’s keeping a journal for the exclusive use of her biographers after she makes it big.

But Alice has a vulnerability—the fact that the first boy she ever kissed dumped her—and, as the story progresses, we realize, a secret fear: That she’s not good enough to be a star. That she is in fact nothing, no one.

It’s the flip side of her megalomania, and it’s what makes us love her.

Because for Alice, she’s either destined for greatness or a waste of space here on this earth—and that’s such a hard, human, and ultimately relatable thing for a young person to believe.

3. Internal conflictsIn Viet Thanh Nguyen’s Pulitzer Prize-winning literary novel The Sympathizer (and its sequel, The Committed), the unnamed protagonist is a double agent during what Americans know as the Vietnam War—which is really about as unsympathetic a position as any imaginable.

Someone who’s loyal to your side, generally speaking, is a “good guy,” and someone loyal to the opposition may be good-hearted but misguided. But someone playing both sides? That’s a person lacking in any loyalties at all.

What makes us love this protagonist (beyond their inherently hilarious voice) is the fact that they genuinely see both sides in that conflict, in keeping with their multiracial heritage (half French and half Vietnamese). He believes in the communist rhetoric of kicking out the West and redistributing the wealth that Western colonizers have stolen … but he also loves American movies and music and the lofty ideals of democracy.

Talk about an internal conflict!

It’s the fact that the narrator is so conflicted about his loyalties—and his loyalties to his two best friends, who wind up on opposite sides of the war—that makes us love him, despite the terrible things he does.

These examples are pulled from three novels I happened to have close at hand. In reality, pretty much any novel you can pull off your shelf will showcase a fear, vulnerability, or internal conflict for the protagonist early on—because doing so does so much to pull the reader in and make us care.

So if you’re looking for ways to strengthen your characterization—or have received feedback to the effect that readers just don’t care all that much about your protagonist—turn to page one of your draft and ask yourself: Where in this opening can I establish vulnerability?

August 7, 2024

4 Questions to Strengthen Lean Manuscripts

AI-generated image (ChatGPT): book that’s growing happily in size.

AI-generated image (ChatGPT): book that’s growing happily in size.Today’s guest post is by Lisa Fellinger, an author, book coach, and editor.

I have a small confession to make: I’ve never been told I need to cut words from my manuscripts. In fact, I’m the author envious of anyone who needs to do so because I’m the one struggling to get my manuscript up to my target word count. And for a long time, I feared I was the only writer with this issue. So many writing articles and discussions focus on how to cut down an overly wordy novel to fit standard word counts, but I hadn’t seen much advice for how to bulk up a manuscript that fell below those expectations.

But over the years, I’ve found writers with similar struggles. I’m not the only one who starts with a lean first draft that needs to be built up to create a well-rounded story. Neither way of writing is right or wrong—it’s truly about what works for you and your process. The important thing is that you understand your genre’s word count expectations and why those expectations exist and that you put in the work to add or cut words to create a deep story.

While writing lean can sometimes feel like it’s wrong approach, there’s absolutely value in it. Writing a lean first draft allows you to see the main points and events that are most central to the story and work to enhance them, rather than having to uncover those main points underneath a mountain of excess words. I’m often told my writing is clear and easy to follow, which I credit to the fact that I write lean initially and build the story from there.

Still, it’s important that lean writers understand the need to deepen those drafts to become reader ready. Readers crave stories that are rich and immersive; novels that fall far below the standard word counts don’t typically do this.

So, for my fellow lean writers out there, here are opportunities to dig into your story and meet your target word count.

1. Do you have a compelling subplot?Subplots are one of the best ways to deepen stories and bulk up a lean manuscript. However, don’t just throw in any subplot and call it a day. If you decide to add or enhance a subplot, focus on one that adds depth to the main storyline rather than distracting from it. If you try to include an unrelated subplot only to increase your word count, readers will sense that and lose interest.

The subplot should have a clear connection to the overall story and its own arc. And just as minor characters should be as fleshed out, a subplot should be well-rounded and complete in its own right, even though as much time won’t be spent on it.

2. Are you summarizing the hard scenes?This is where I often find the most gold in terms of increasing word count, as well as in the novels I work with for developmental editing or book coaching.

It’s especially common in first drafts for writers to summarize the hard scenes—scenes that either feel technically difficult to write or are especially emotional. Since these scenes require so much work to do them justice, it’s tempting to gloss over them by providing a summary of what happened rather than dramatizing the entire scene.

But readers don’t invest in novels to read summaries of what happened to the characters. They want to experience those events alongside them and feel their emotions in real time. Skipping over those difficult scenes robs the reader of that experience and the opportunity for them to feel a strong connection to your story. While summary is sometimes necessary or the best choice for certain scenes, for scenes that are highly emotional and/or central to the overall story, dramatize them so readers can experience the events and emotions along with your characters.

And—bonus points—dramatizing a scene that you initially summarized will absolutely increase your word count.

3. Are you digging into your characters’ thoughts and reactions?One reason readers often declare “the book was better than the movie” is because books allow for the opportunity to see inside of your characters’ thoughts in a way that movies can’t. So use that to your advantage.

While you don’t want to do this to the extreme—where you’re repeating the same things to the point of boring your readers—you do want to ensure that your readers understand your characters’ reactions to events, especially critical ones. Showing a character’s thoughts can be a good way to bridge the gap between an event and a reaction from a character that doesn’t necessarily make sense. While a reaction might seem odd on the surface, if you can show us the thought process that led them there, then readers will understand it even if another character may not. And digging deep into your characters’ thoughts will build stronger reader connections with your characters.

4. Is your setting clear and detailed enough?I know I’m guilty of this one in my own writing. It’s easy for me to get so caught up in the dialogue between two characters, or exploring a character’s thoughts and emotions, that I forget to include enough detail about where events take place. But readers need to be able to visualize the story as it unfolds rather than wondering where the characters are.

As you’re reading through your manuscript, ask yourself: Would the reader be able to visualize where these events are taking place by the words on the page? While too much setting description can slow your story’s pacing and bore your reader, this is an area where I often see lean writers being skimpy. It’s an ideal opportunity to strengthen the story while also adding to your word count.

Parting adviceTarget word counts exist for a reason. That’s generally the sweet spot where a story will have enough detail and information to create a full, rich story for readers to enjoy without giving way to digressions or slow pacing. While there are always exceptions to word count standards, be honest with yourself about why your story falls outside of them. If you’re below the target like I often am, I hope these questions will help you determine if your story really is complete or if there’s room to add and create an even stronger story.

July 31, 2024

How to Use Tarot to Build Your Brand as a Creative

Today’s post is by Chelsey Pippin Mizzi, author of Tarot for Creativity: A Guide for Igniting Your Creative Practice.

After years of working 9–5 at an agency, my client, Nina decided to strike out on her own and launch a copywriting business. In the early stages of building her business, she came to me to explore the ways that tarot could support and inspire her as a creative business owner.

One of the things Nina was most concerned about in that moment was figuring out how she wanted to be perceived by her customers—her main job as a copywriter was to help small businesses express themselves, but she felt she’d lost her own identity amidst all her efforts to help her clients articulate theirs.

The tarot is an incredibly powerful brand building tool for creatives, because it gives us a rich language for finding—and articulating—ourselves, so Nina and I dove into some exercises that ultimately helped her develop a clear vision of who she was a small business owner, what she wanted to say to her potential customers, and create a framework for how she wanted to say it.

Here are two of the tarot exercises that helped Nina—and many of my clients—discover and solidify their brands.

Own your creative archetypeFirst, I asked Nina to write down three adjectives she would love her ideal clients to use to describe her and the service she provides them. Nina landed on “Honest, Bold, and Bright.”

From there, I laid out all 22 cards of the Major Arcana between us, and asked Nina to pick one or two of the cards that she felt most clearly illustrated what Honest, Bold, and Bright meant to her.

She narrowed it down to two cards: The Fool, and The World, two cards that she felt embodied Honest, Bold, and Bright—but there was more work to do. Which one, I asked, felt more like her? Nina’s answer came immediately: while she admired The World’s wisdom, she was deeply drawn to the Fool’s playfulness. Both cards possessed a confidence, an openness, but Nina knew that she saw herself as that clever, unassuming Fool much more than she saw herself as the simultaneously vulnerable and untouchable World.

So, the Fool became Nina’s creative archetype. Which means that when she’s representing her business—through online content, at networking events, or in client meetings, she refers back to the Fool as a guiding light for how she wants to be seen, and how she wants to interact. Embracing the Fool as her creative archetype gave Nina a fresh new way of thinking about her point of view as a copywriter and small business owner, and she returns to the card regularly while navigating her career and building her brand.

When she’s not sure what to post about on LinkedIn, she thinks about the Fool, and how she can summon the card’s playfulness, its boldness, its honesty, its brightness to articulate a helpful tip or thought-provoking opinion. She plays up her sense of humor, because that’s what the Fool would do. Her brand is full of bright colors, and whenever she enters a room—IRL or digital, she brings the Fool’s charisma and try-anything attitude with her. These days, Nina even turns to the tarot with some of her copywriting clients, inviting them to identify their own brand archetype through the Major Arcana. She then uses conversations that the cards strike up as a foundation for the tone of voice and point of view she infuses into the writing services she provides.

Try it yourselfWrite down three adjectives you’d like your ideal audience or customer base to use when describing you and your creative work.Lay out the Major Arcana in front of you, and choose a card (or two) that best captures those three words, and that feels true to you and how you want to show up in the world.Brainstorm at least three ways you can use the card you’ve chosen to inform your approach to your creative business, brand, and communications.Whenever you feel stuck in your business, refer back to the archetype you’ve chosen, and use it as a jumping off point to figure out what to do next.Tarot your way to contentOne of the most common ways that I use tarot cards as creativity tools is incorporating them into my content planning. I regularly use cards as jumping off points for my blogs, newsletters, and social media posts. It’s simple: I draw a card and ask myself a couple of questions:

How does this card relate to the way I want my audience or customers to feel?How can the message of the card help me solve a problem for my audience or customers?What’s one thing this card inspires me to tell my audience or customers?Of course, as a tarot reader, it makes sense that I would turn to the cards for content generation, but the truth is that my method for content generation through tarot can work for any small business owner.

Let’s look at Nina and her copywriting business once again as an example.

Last year, Nina challenged herself to write a short, regular newsletter in which she shared a daily tip for writing more compelling copy. She decided to use tarot cards to inform what she wrote, just like I do in my tarot business. Once a week, she would sit down and draw five cards—one for each day of the week that she would send out her newsletter. And she asked herself the questions that I shared above.

The Ten of Wands, a card that often represents someone biting off more than they can chew, inspired Nina to write a tip about doing more with less in your copy. Instead of trying to cram every bit of information into a paragraph, she suggested that her followers try focusing on the three most important messages they wanted to share, and she provided a formula for figuring out what those three messages could be.

Judgement, a card about revisiting things we’ve buried and shining a new light on them, was the foundation for a piece Nina wrote about how to find new ideas in old copy. She even ended up offering a service to help her clients audit their past newsletters and blogs and create fresh content based on their previous ideas.

Amazon • Bookshop

Amazon • BookshopAnd the Eight of Pentacles, a card about practice and craft, prompted Nina to share a personal story about how she learned to improve her own copywriting skills and why she still practices writing, even as a professional writer.

None of Nina’s final versions of her articles mentioned the tarot; she simply looked to the images to spark her thinking so she could generate content that was in line with her business.

You can do the same by drawing cards and answering the questions I shared above—you’ll be surprised by how many ideas you’ll be able to generate!

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out Tarot for Creativity: A Guide for Igniting Your Creative Practice by Chelsey Pippin Mizzi.

July 30, 2024

How to Write a Story Retelling

Photo by Elaine Howlin on Unsplash

Photo by Elaine Howlin on UnsplashToday’s post is by developmental editor and book coach Hannah Kate Kelley.

What is a retelling?A retelling is a new spin on a classic story like a fairy tale, myth, or other piece of literature. The writer takes a pre-existing story to borrow some of the original elements while changing others.

Writers love retellings because the story framework is pre-made and there’s already a proven audience for the original tale. Retellings are also empowering because writers can bring fresh perspectives to age-old stories.

But aren’t retellings theft? Actually, no. Retellings essentially honor the original text by reopening the conversation the original author started. Instead of feeling like a thief, think of your adapted story as playing off of, countering, and contributing to that initial conversation.

In your life, you’ve probably encountered many retellings from Disney’s fairy tale renditions to countless comic book blockbuster remakes. In this article, we’re going to look at the following popular retelling examples:

A Court of Thorns and Roses by Sarah J. Maas (a retelling of several stories, including Beauty and the Beast, the Norwegian tale East of the Sun and West of the Moon, and Tam Lin)Circe by Madeline Miller (a retelling of Homer’s The Odyssey)Clueless by H. B. Gilmour (a retelling of Jane Austen’s Emma)Pride: A Pride and Prejudice Remix by Ibi Zoboi (a retelling of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice)The Chosen and the Beautiful by Nghi Vo (a retelling of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby)“The Husband Stitch” featured in Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado (a retelling of “The Girl with the Green Ribbon”)3 characteristics of retellingBefore you build your outline, let’s explore the three primary characteristics of a retold story.

A retelling should be recognizableRetellings are all about celebrating the familiar. Your story retelling needs to include all or many of the major original elements, even if you make significant changes to the setting, plot, characters, and themes. But how close of a retelling do you need to write? You’ve got two options: write a loose retelling or a close retelling.

In a loose retelling, writers can use inspiration from various sources in any degree, meaning they have recognizable characters, events, themes, and other elements, but their main plot will divert away from the original storyline.

Sarah J. Maas does this with her fantasy novel A Court of Thorns and Roses by drawing from Beauty and the Beast, East of the Sun and West of the Moon, and Tam Lin. In terms of her original inspiration fairy tales and legends, Maas says, “[A Court of Thorns and Roses] actually wound up going away from those things; it started off as a retelling of the more original fairy tales, but then moved away.” Though the story begins with a young woman stolen away to live in the home of a powerful and mysterious creature as punishment for her transgression (similar to Beauty and the Beast), protagonist Feyre delves into broader political and inter-court conflicts as the story goes on, culminating in a dangerous physical and emotional trial. Maas uses some of the character traits and plot events from the original texts, but ultimately creates her own storyline.

In a close retelling, writers can still change several elements of the original text, but they tend to stick closer to the main plot by using the same events in the same order, making only small variations. For example, in The Chosen and the Beautiful, writer Nghi Vo retains not only the 1920s era and several main character from the original text The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, but Vo also keeps the key plot events, such as Gatsby’s extravagant parties, his mounting obsession with Daisy Buchanan, and the climactic confrontation in a New York hotel. The unique angle, a queer Vietnamese adoptee narrator, doesn’t change the plot events significantly.

A retelling should also be a standaloneYour retelling should be enjoyable to read whether your audience has read the original text or not. While many of your readers will be familiar with the original story and therefore enjoy the comparisons and allusions you draw between them, your story still needs to be complete on its own.

A retelling must be legalWe already established that retellings are not theft, but there’s a caveat: it all comes down to what is and is not listed on the public domain (also known as the commons), which is a collection of creative works that are no longer protected by intellectual property laws. Once a story hits this list, you are free to adapt and reproduce it any way you wish. That’s why people love to use fairy tales for their adaptations, because no one owns the copyrights to these stories any longer. However, the rules differ from country to country, as well as by the book’s individual copyright, so it’s best to do your due diligence and research before selecting the story you wish to retell. (Here a starting guide from Jane on that.)

Are retellings the same as fanfiction?In many ways, yes. But they are treated differently in terms of both legal use and reader expectations, so they are essentially different genres. Fanfiction is more about celebrating the copyrighted characters of a story which are not yet in the public domain. Can you base your retelling off a non-public domain work? Some writers do. Fifty Shades of Grey by E.L. James actually started out as fanfiction of Twilight by Stephenie Meyer. Though the book has several similarities with the original source, James retroactively removed the copyrighted material in order to publish. Talk about grey area! While it is possible to transform fanfiction into a legally sound published book, there are more hoops to jump through.

I’m no lawyer, so we won’t get into the nitty-gritty of what is and isn’t legally allowed for non-public domain works. Just do your research and be prepared to consult legal counsel if you plan to publish your fanfiction for profit.

So let’s talk about how to write your own retelling. If you’d like a workbook to pair with the following exercises, you can download the free Story Retelling Workbook.

Choose your retelling angleThe first step is to explore what you are going to do differently and why. What will your unique spin be? While this angle can change later, you want to capture this first spark of inspiration because this is the reason you’re writing a retelling after all: to make this story your own.

To find your special angle, ask yourself the following questions:

What do you love about the original story? Explore what made you want to pick up the book in the first place, or what’s kept this tale top of mind for you.What’s missing from this story? Consider which parts didn’t resonate with you or where you can see room for improvement.Can you see yourself in this story? If you can, consider what you would do differently as one of the main characters and how that might send the story down a different path. If you can’t, consider how your perspective or knowledge could alter the story if you were suddenly thrust into the pages.Why are you writing this story? Consider what unique perspectives you as the author bring to your story.And why now? If you have other story ideas you want to pursue, consider why you want to start with this one first.Once you’ve embarked on a little soul-searching, you might have a good list of where to take your story. If not, consider these common retelling angle examples:

Feature a new character’s perspective. You can use a non-main character from the original text, like Nghi Vo does in The Chosen and the Beautiful by using Nick Carraway’s friend and lover Jordan Baker as the narrator instead. Or like writer Madeline Miller does with Odysseus’ villain scorned witch-goddess Circe in the eponymous novel Circe (instead of Odysseus). You can also invent an entirely new character to take the spotlight.Imagine the antagonist as the protagonist. Similar to drawing from a new character’s perspective, this approach goes as far as reclaiming and explaining the villain’s side of things. For example, in Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West by Gregory Maguire the story is told from the Wicked Witch of the West’s point of view, offering a backstory that humanizes her and explores the events that leading up to her infamy. And in the Jane Eyre retelling Wide Sargasso Sea, author Jean Rhys gives Bertha Mason her own voice and backstory, who was originally a minor character depicted as Mr. Rochester’s insane wife he kept hidden in the attic.Explore race, class, gender, or a new cultural lens. Many old texts can perpetuate harmful stereotypes. In “The Husband Stitch” by Carmen Maria Machado, the narrator explores women’s bodily boundaries in her retelling of “The Girl with the Green Ribbon.” Her rendition critiques the original short horror story, where a woman’s husband constantly pesters her about her permanent neck ribbon until she finally allows him to pull the string and immediately dies from the untying that kept her head on her neck. Machado calls out the way men use and control women’s bodies in her retelling.Drop the characters into a new setting or era. For older works especially, it can be fun to use a modern setting, just as H. B. Gilmour does in her popular Emma-adapted novel Clueless, by bringing the romance into a contemporary (okay, well … 90s) high school setting complete with stoners, jocks, and popular kids.Switch up the genre. Consider altering the genre toward horror, sci-fi, fantasy, romance, mystery, and literary fiction, or even a different age genre like children’s, middle grade, young adult, or adult. A good example of this is Pride and Prejudice and Zombies by Seth Grahame-Smith, who transforms the original romance story into a horror novel by incorporating zombies, a pervasive sense of danger, and violent encounters with the undead.If you’re swimming in good ideas, narrow down your selection to one story angle. Then write your unique angle in one simple sentence. For example, I want to explore what the wicked stepmother would look like in Cinderella if she was actually just trying to help.

Analyze the original textBefore you can write your own version, get your analytical hat on and let’s look at the original (OG) story to see which elements you want to keep and which you want to change.

At this point, you want to be in the research phase rather than the writing phase, though you can jot down ideas as they come up. But don’t get lost in research! For this exercise, try to only gather enough information to fill out this brief analysis.

We’re going to look at both the OG text Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen and the retelling Pride: A Pride and Prejudice Remix by Ibi Zoboi. While you want to focus on your analysis before crafting your own story, it’s helpful to discuss these two examples side by side.

Plot pointsFirst, look for all the major plot points that make the OG story recognizable by uncovering how the main plot and the main characters progress to the end. Depending on how loose or close you want your retelling to be, you may choose to diverge away from these plot events—which can be an interesting way to subvert reader expectations and dive into the story you really want to tell. Regardless of whether you want to incorporate all the plot points or build in your own twists, it’s important to be aware of a baseline series of events first.

Let’s break down the major plot points of Pride and Prejudice.

Setup: The marriage prospects of a young woman named Elizabeth Bennet and her four sisters are a constant concern for their mother because of the estate’s lack of a male heir.

Inciting Incident: The wealthy and eligible bachelor Mr. Bingley rents the nearby Netherfield Park, sparking excitement among the Bennet family and their neighbors. His friend, the wealthy and proud Mr. Darcy, accompanies Mr. Bingley to help find him a suitable match and immediately butts heads with Elizabeth.

Midpoint: After a series of rising romantic tension, Mr. Darcy proposes to Elizabeth in a manner that reveals his feelings but also insults her family, which leads her to reject him.

Climax: Elizabeth’s younger sister Lydia Bennet elopes with sly militia man Mr. Wickham, threatening the Bennet family’s reputation.

Resolution: After Darcy’s intervention to save her family’s reputation from Mr. Wickham’s hasty elopement, Elizabeth reevaluates her feelings for him. Darcy renews his proposal, this time with humility and love, and Elizabeth accepts, leading to their marriage and the resolved misunderstandings.

And now let’s look at the major plot points of Pride, which is a close retelling:

Set Up: In the contemporary Brooklyn neighborhood of Bushwick, teenager Zuri Benitez and her family navigate rapid gentrification as she prepares to write her college application essay.

Inciting Incident: The arrival of the wealthy Darcy family, including two handsome and single teenage sons, sparks tension as they move into the renovated mini mansion across the street. Zuri and the younger son Darius immediately butt heads.

Midpoint: After weeks of romantic tension, Zuri and Darius kiss. He asks her out on a date, but she refuses him when she finds out he slighted her older sister and a heated confrontation about their biases and assumptions ensues.

Climax: At a house party, tensions rise between Zuri and Darius over the division between their socioeconomic worlds, when Zuri then discovers her creepy ex Warren is preying on her thirteen-year-old drunk sister.

Resolution: Zuri and Darius reconcile their differences after saving her sister, finding common ground amidst the changing landscape of their neighborhood, even when Zuri and her family have to move to a new home. And Zuri finally finds the inspiration she needs to write her college application essay.

SettingWhether you choose to change the setting or not, it is important to understand the context in which the author wrote the OG story. Not only will this help you understand where the writer came from, but it will also help you understand how they framed the events and crafted their characters.

Obviously, the world looked very different when Jane Austen penned Pride and Prejudice. Young women had strict roles in society which largely had to do with finding a suitable husband to marry, so the story’s subject matter suits the slower, rural setting where the cast of characters can meet exciting marriage prospects among both wealthy gentlemen visitors and the militia.

You can keep the same setting or change it entirely, and both have their advantages. A closer retelling with a similar setting will make the other contrasts starker, whereas a different era or geographical location will make these contrasts subtler.

The setting in Pride and Prejudice:

Location: Meryton, England, a fictional small market town based in rural Hertfordshire and Derbyshire

Time Period: Early 19th century

Setting-Specific Elements

Formal balls and “calling on” neighbors, which were some of the only ways gentlemen and ladies could socialize and assess marriage prospects.Handwritten letters, meant to show the most honest way to communicate feelings in great detail.Long walks, meant to show how characters could be reflective and independent, as well as how they could have chance encounters and travel without carriages.The setting of Pride:

Location: Brooklyn, New York in the United States, specifically in the Bushwick neighborhood

Time Period: Contemporary 2010s era

Setting-Specific Elements

Block parties, dates and community events, which serve as modern equivalents to formal balls, where characters socialize, interact, and form romantic relationships within their neighborhood.Texting, like the handwritten letters in Pride and Prejudice, allows characters to communicate their feelings quickly and directly.Gentrification, where the changing streets of Bushwick expose the community’s evolution, their own identities, and their encounters with others.CharactersThe most memorable parts of retellings are arguably the characters, whose voices and actions stick with readers long after finishing a book. It’s important to analyze who the primary, secondary, and tertiary characters are, what their top traits are, and how they provide all conflict and support for the protagonists.

This is also a good time to note harmful stereotypes the OG text might be perpetuating. If a character’s primary traits are rooted in sexist tropes, like how many of our fairy tales depict women antagonists as ugly, be aware of how you can twist this stereotype on its head.

The main cast of characters in Pride and Prejudice:

Miss Elizabeth Bennet: The primary protagonist, known for her sharp wit and independenceMr. Fitzwilliam Darcy: A wealthy, reserved, and seemingly proud gentleman who becomes one of Elizabeth’s love interestsElizabeth and Mr. Darcy’s internal pride and prejudiceMr. Wickham: A charming but deceitful militia officerSignificant or memorable secondary and tertiary characters:

Mr. Bennet: Elizabeth’s sarcastic and laid-back fatherMrs. Bennet: Elizabeth’s frivolous and marriage-obsessed motherMiss Jane Bennet: Elizabeth’s beautiful and gentle older sisterMr. Bingley: A wealthy and amiable gentleman who rents Netherfield ParkThe main cast of characters in Pride: