Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 27

January 1, 2025

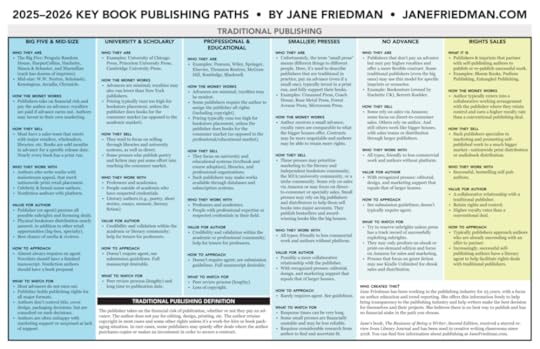

The Key Book Publishing Paths: 2025–2026

Since 2013, I have been regularly updating this informational chart about the key book publishing paths. It is available as a PDF download—ideal for photocopying and distributing for workshops and classrooms—plus the full text is also below.

These PDFs are formatted to print perfectly on 11″ x 17″ or tabloid-size paper.

Traditional publishing paths (1 page)Other publishing paths (1 page)All publishing paths (2 pages)One of the biggest questions I hear from authors today: What is the best way to publish my work?

This is an increasingly complicated question to answer because:

There are now many varieties of traditional publishing and self-publishing, with evolving models and diverse contracts.It’s not an either/or proposition; you can do both. Many successful authors, including myself, decide which path is best based on our goals and career level.Thus, there is no one path or service that’s right for everyone all the time; you should take time to understand the landscape and make a decision based on long-term career goals, as well as the unique qualities of your work. Your choice should also be guided by your own personality (are you an entrepreneurial sort?) and experience as an author (do you have the slightest idea what you’re doing?).

For 2025–2026, I’ve greatly expanded this chart.The chart is now two full pages instead of one. One page focuses on traditional publishing. The other page focuses on alternative paths, including paid publishing options, self-publishing, and informal types of publishing, like Substack newsletters or social media. This chart’s logic is driven primarily by how the money works and how and where the work is sold.

Here’s a quick overview.

Traditional publishing (the big guys and the little guys): I define traditional publishing as the publisher taking on the financial risk, not the author. Bigger publishers typically invest in a print run for the book; smaller publishers may focus on digital forms of publication (ebook, digital audio, and/or print on demand). Sometimes the author sees no income from the book aside from the advance; in today’s industry, it’s commonly accepted that most book advances don’t earn out. However, authors do not have to pay back the advance; that’s the risk the publisher takes.

University & scholarly publishers / professional & educational publishers. For the first time, I’ve added other sectors of book publishing, such as scholarly and professional publishing. These publishers generally do not publish for consumers, or produce the sort of books that bookstores sell or that an average person might buy. With professional and educational publishers, authors may not even retain their copyright. It is a sector of the industry that plays by a set of rules that can be quite different from trade (consumer) publishers.

I’ve included them in this version for clarity and because university presses in particular have become important players for literary writers, especially those producing poetry, short story collections, essay collections, and other works that the big traditional publishers don’t often accept.

Smaller traditional publishers. This is the category most open to interpretation among authors, and every year I struggle with how to describe them because they are so varied. Authors must exercise caution when signing with small presses; some mom-and-pop operations offer little advantage over self-publishing, especially when it comes to distribution and sales muscle.

When a traditional publisher doesn’t offer an advance: This can have important business implications for the author and the book. The author may not receive the same support and investment from the publisher on marketing and distribution. The less financial risk the publisher accepts, the more flexible your contract should be—and ideally they’ll also offer higher royalty rates. That is why I’ve segmented no-advance traditional publishing into its own category, but it’s still a traditional deal as long as the author isn’t paying for costs related to publication. As soon as the author does pay costs (aside from costs related to research, permissions or indexing, which are typically covered by the author), it’s a paid publishing situation.

Rights sales. In the last few years, it’s become much more prevalent for longtime traditional publishers to collaborate with self-publishing authors, allowing the authors to retain digital rights while helping them sell more broadly through print retail. Some newer publishing companies, such as Podium, have focused on such partnerships from the very start.

Of course, all authors can and do benefit from rights sales. Agents normally sell rights for traditionally published authors; increasingly, successful self-published authors have agents to do the same.

Hybrid publishers and paid publishing services. This is where the author pays to publish. Costs vary widely (low four figures to well into the five figures—even six figures). There is a risk of paying too much money for basic services or purchasing services you don’t need. Some people ask me about the difference between a hybrid publisher and paid publishing services. Sometimes there isn’t a difference, but here’s a more detailed answer. It is paramount that any author closely research and study these companies before investing. Scams abound.

Self-publishing. I define this as publishing on your own, where you essentially start your own publishing company, and directly hire and manage all help needed. Here’s an in-depth discussion of self-publishing.

Social publishing. Social efforts will always be an important and meaningful way that writers build a readership and gain attention, and it’s not necessary to publish and distribute a book to say that you’re an active and published writer. Plus, these social forms of publishing increasingly have monetization built in, such as Patreon. I’ve also included serialization platforms here, some which have a social or community component, like Wattpad.

You don’t need permission to use thisFeel free to download, print, and share this chart however you like; no permission is required. Below I’ve pasted the full text from the chart.

Traditional publishing definition: The publisher takes on the financial risk of publication, whether or not they pay an advance. The author does not pay for editing, design, printing, etc. The author retains copyright in most cases and some other rights unless it’s a work-for-hire or book packaging situation. In rare cases, some publishers may quietly offer deals where the author purchases copies or makes an investment in order to secure a contract.

Big Five & Mid-Size Traditional PublishersWho they areThe Big Five: Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Hachette, Simon & Schuster, and Macmillan (each has dozens of imprints).Mid-size: W.W. Norton, Scholastic, Kensington, Arcadia, Chronicle.How the money worksPublishers take on financial risk and pay the author an advance; royalties are paid if advance earns out. Authors may invest in their own marketing.How they sellMost have a sales team that meets with major retailers, wholesalers, libraries, etc. Books are sold months in advance for a specific release date. Nearly every book has a print run.Who they work withAuthors who write works with mainstream appeal, that merit nationwide print retail placement.Celebrity & brand-name authors.Nonfiction authors with platform.Value for authorPublisher (or agent) pursues all possible subrights and licensing deals.Physical bookstore distribution nearly assured, in addition to other retail opportunities (big-box, specialty).Best chance of media & reviews.How to approachAlmost always requires an agent. Novelists should have a finished manuscript. Nonfiction authors should have a book proposal.What to watch forMost advances do not earn out.Publisher holds publishing rights for all major formats.Authors don’t control title, cover design, packaging decisions, but are consulted on such decisions.Authors are often unhappy with marketing support or surprised at lack of support.University & Scholarly Traditional PublishersWho they areExamples: University of Chicago Press, Princeton University Press, Cambridge University Press.How the money worksAdvances are minimal; royalties may also run lower than New York publishers.Pricing typically runs too high for bookstore placement, unless the publisher does books for the consumer market (as opposed to the academic market).How they sellThey tend to focus on selling through libraries and university systems, as well as direct. Some presses who publish poetry and fiction may put some effort into reaching the consumer market.Who they work withProfessors and academics.People outside of academia who have respected credentials.Literary authors (e.g., poetry, short stories, essays, memoir, literary fiction).Value for authorCredibility and validation within the academic or literary community; help for tenure for professors.How to approachDoesn’t require agent; see submission guidelines. Full manuscript desirable.What to watch forPeer review process (lengthy) and long time to publication date.Professional & Educational Traditional PublishersWho they areExamples: Pearson, Wiley, Springer, Elsevier, Thomson Reuters, McGraw Hill, Routledge, Blackwell.How the money worksAdvances are minimal; royalties may be modest.Some publishers require the author to assign the publisher all rights (including copyright).Pricing typically runs too high for bookstore placement, unless the publisher does books for the consumer market (as opposed to the professional or educational market).How they sellThey focus on university and educational systems (textbook and course adoption), libraries, and professional organizations.Such publishers may make works available through databases and subscription systems.Who they work withProfessors and academics.People with professional expertise or respected credentials in their field.Value for authorCredibility and validation within the academic or professional community; help for tenure for professors.How to approachDoesn’t require agent; see submission guidelines. Full manuscript desirable.What to watch forPeer review process (lengthy).Loss of copyright.Smaller Presses (Traditional Publishing)Who they areUnfortunately, the term “small press” means different things to different people. Here, it’s used to describe publishers that are traditional in practice, pay an advance (even if a small one), typically invest in a print run, and fully support their books. Examples: Unnamed Press, Coach House, Rose Metal Press, Forest Avenue Press, Microcosm Press.How the money worksAuthor receives a small advance; royalty rates are comparable to what the bigger houses offer. Contracts may be more negotiable and authors may be able to retain more rights.How they sellThese presses may prioritize marketing to the literary and independent bookstore community, the MFA/university community, or a niche community. Some rely on sales via Amazon or may focus on direct-to-consumer or specialty sales. Small presses may rely on big publishers and distributors to help them sell books into major accounts. They publish bestsellers and award-winning books like the big houses.Who they work withAll types; friendly to less commercial work and authors without platform.Value for authorPossibly a more collaborative relationship with the publisher.With recognized presses: editorial, design, and marketing support that equals that of larger houses.How to approachRarely requires agent. See submission guidelines.What to watch forResponse times can be very long.Some small presses are financially unstable and may be less reliable.Requires considerable research from author to find and ascertain fit.No Advance Traditional PublishersWho they arePublishers that don’t pay an advance but may pay higher royalties and offer a more flexible contract. Some traditional publishers (even the big ones) may use this model for specific imprints or scenarios.Example: Bookouture (owned by Hachette UK), Berrett-Koehler.How they sellSome rely on sales via Amazon; some focus on direct-to-consumer sales. Others rely on author. And still others work like bigger houses, with sales teams or distribution through larger publishers.Who they work withAll types; friendly to less commercial work and authors without platform.Value for authorWith recognized presses: editorial, design, and marketing support that equals that of larger houses.How to approachSee submission guidelines; doesn’t typically require agent.What to watch forTry to reserve subrights unless press has a track record of successfully exploiting subrights.They may only produce an ebook or print-on-demand edition and focus on Amazon for sales and marketing.Rights Sales (Traditional Publishers)What it isPublishers & imprints that partner with self-publishing authors to publish or re-publish successful work.Examples: Bloom Books, Podium Publishing, Entangled Publishing.How the money worksAuthor typically enters into a collaborative working arrangement with the publisher where they retain control and earn a higher royalty rate than a conventional publishing deal. How they sellSuch publishers specialize in marketing and promoting self-published work to a much bigger market—nationwide print distribution or audiobook distribution.Who they work withSuccessful, bestselling self-pub authors.Value for authorA collaborative relationship with a traditional publisher.Retain rights and control.Higher royalty rates than a conventional deal.How to approachTypically publishers approach authors who are already succeeding with an offer to partner.Increasingly, successful self-publishing authors have a literary agent to help facilitate rights deals with traditional publishers.Other publishing paths definition: Any scenario where the author is paying for publication (shouldering the financial risk) or working independently.

If you pay any publisher or company to publish you—as you do in the hybrid and paid publishing service scenarios—some people will call it vanity publishing, but I avoid use of that term. (See later section on “gray areas and controversies.”)

Hybrid PublishersHybrid publishers work like traditional publishers in that they put their name on your book and become the publisher of record. Paid publishing services discussed later may or may not do this—or they may even offer you a choice.

Who they arePublishers that require accepted authors to pay to publish or raise funds to do so.Hybrid publishers have the same business model as paid services; the author pays costs.Examples of hybrid publishers: Amplify Publishing, Page Two, She Writes Press, Collective Book Studio, Matador (UK), Unbound (UK).How the money worksAuthors fund publication; cost varies.Hybrids pay royalties and author signs a publishing contract.Each hybrid publisher and each book carries its own distinctive costs. Package pricing may not include print run, developmental or content editing, marketing and promotion, etc.Because of the cost ($25,000 is a good rule of thumb assuming a print run is involved), it is challenging to earn a profit from book sales alone. Not a sustainable career path for novelists over many titles.How they sellSome hybrid publishers have distribution via Simon & Schuster Distribution Services or Ingram’s Two Rivers. This can help with bookstore placement as well as other types of consumer sales. However, without author investment in marketing and promotion, and a print run, such sales are unlikely; retail placement is never assured in any event. Sometimes retail placement must be paid for by author.Value for authorIf the hybrid has a good reputation and a strong community of authors, this can support sales.Some companies are run by former traditional publishing professionals and offer high-quality results.What to watch forSome services call themselves “hybrid” when they are not a hybrid.Authors often expect editing that does not happen.Authors can be persuaded to pay because they feel selected/special.Paid Publishing ServicesWho they areServices or individuals that help authors publish their work. They differ from hybrids in a few ways: (1) It is often a service agreement, not a publishing contract. (2) Authors often publish under their own name or imprint. (3) The best services do not take a cut of sales or pay royalties. Author earns 100 percent net on book sales.Examples of paid publishing services: Author Imprints, Girl Friday Productions.How the money worksAuthors fund book publication in exchange for assistance; cost varies.Some firms handle all aspects from start to finish and subcontract, paying workers on author’s behalf. With smaller outfits or individuals, they may connect authors with freelance help.How they sellThey don’t sell at all. The selling is up to the author. Some offer paid marketing packages, assist with the book launch, or offer paid promotional opportunities.Some services assist authors in setting up basic distribution available to self-published authors (IngramSpark and Amazon KDP).Value for authorProduce a quality book without navigating the service and freelance landscape solo. Ideal for authors with more money than time.Get help setting up an imprint and understanding how the self-publishing process works before going it alone.What to watch forAvoid companies that take advantage of author inexperience and use high-pressure sales tactics, such as AuthorSolutions imprints (AuthorHouse, iUniverse, WestBow, Archway, and others).Self-PublishingWhat it isThe author manages the publishing process and hires the right people or services to edit, design, publish, and distribute. The author remains in complete control.Authors set up accounts with ebook retailers to sell (Amazon KDP, B&N Press, Apple Books, Kobo), or use an ebook distributor (Draft2Digital).Authors use print-on-demand (POD) to sell and distribute print books via online retail. Most often used: Amazon KDP, IngramSpark. It costs nothing to distribute titles.If authors are confident about sales, they may hire a printer, invest in a print run, manage inventory, fulfillment, shipping, etc.How the money worksAuthor sets the price of the work; retailers/distributors pay based on the price of the work.Most ebook retailers pay 70% of retail for ebook sales if pricing is within their prescribed window (for Amazon: $2.99–$9.99).Amazon KDP pays 60% of list price for print sales, after deducting the unit cost of printing the book.What to watch forAuthors may not invest enough money or time to produce a quality book or market it effectively.Authors may not have the experience to know what quality help looks like or what it takes to produce a quality book.It is nearly impossible to get mainstream reviews, media attention, or sales through conventional channels (bookstores, libraries), unless the author is a known name.When to prefer over hybrid/paid servicesThe author intends to publish many books and make money via sales over a long period.The author is invested in marketing, promotion, platform, and developing an audience for their books over years.Social PublishingWhat it isWrite and publish work in a public or semi-public forum, directly for readers.Publication is self-directed and continues on an at-will and almost always nonexclusive basis.Emphasis is on feedback and growth; sales or income can be challenging.Value for authorAllows writers to develop an audience for their work early on, even while learning how to write.Popular writers at community sites may go on to traditional book deals.Many popular platforms include monetization methods, such as tipping/donations, ad revenue sharing, and premium content options for paying readers.Most distinctive categoriesSerialization: Readers consume content in chunks or installments and offer feedback that may help writers revise. Establishes a fan base, or a direct connection to readers. Serialization may be used as a marketing tool for completed works. Examples: Wattpad, Webtoon.Fan fiction: Work based on other authors’ books and characters. It can be difficult to monetize fan fiction since it may constitute copyright infringement. Examples: Fanfiction.net, Archive Of Our Own, Wattpad.Social media, newsletters, and blogs: All types of authors use popular platforms to share work and establish a readership. Examples: Substack, Instagram, TikTok, YouTube.Patronage: Readers pay regularly for access to you and your content. Popular platforms include Patreon and Substack.Money and rightsAuthor retains copyright and rights to the work generally.Platforms like Substack or Patreon take 5–15% of payments, in addition to payment processing fees.Gray areas and controversiesWhat is vanity publishing? This is a pejorative term going back decades that generally refers to any arrangement where the author pays a company to publish their book. In particular, some people accuse hybrid publishers of being “vanity” publishers, usually in the spirit of calling out business practices they do not like or find deceptive. However, calling any company a “vanity publisher” tends to unfairly judge or shame authors whose best path forward may be paying to publish, whether they use a hybrid or some other company.

How can authors avoid a vanity publisher? Usually when writers ask this question, they want to avoid the bad business practices of some paid publishing services, or they’re trying to avoid the stigma associated with paying to publish. It is better to ask: How can I find a publisher or a service that helps me accomplish my goals? Many writers have not thought about their goals or what they hope to achieve beyond book sales, which are likely to be minimal (less than 2,000 copies). This leads to expensive mistakes and misplaced expectations across all publishing paths.

How can authors find a “good” hybrid publisher? There is no such thing as a “good” hybrid publisher for all authors, just as there is no such thing as a “good” agent or a “good” publisher for all authors. (Read more from me on this.) However, writers may ask this question knowing that some companies call themselves “hybrids” and take more rights (and/or charge higher fees), but don’t adhere to any industry criteria. The better question to ask: What does this publisher/company provide that authors can benefit from or they cannot get elsewhere? The biggest mistake authors make in looking for a hybrid publisher is believing a “hybrid” will be a “level up” from self-publishing or that it’s more “innovative” than traditional paths. The companies themselves often market to authors in this way, and all sorts of paid companies outside traditional publishing play to the author’s ego or harp on how traditional publishing is broken. Authors who believe the system is broken most often self-publish.

Some recognized hybrid publishers focus on publishing nonfiction by business people, thought leaders, and others who can’t secure a traditional publishing deal, want to publish quickly, or want to retain as much control as possible. They often have enough money that the cost is inconsequential and/or they know they will earn back the investment in other ways (e.g., increased business, speaking, clients, etc).

What about assisted publishing or partnership publishing? The meaning of these terms vary depending on who’s using them. In most cases, it refers to a paid publishing or a hybrid publishing service. In other cases, it may be a traditional publisher offering a hybrid or paid service if they’ve rejected authors for a traditional deal. In still other cases, it may mean a profit-sharing arrangement (no advance) with a traditional publisher. Because of the varied meanings, it’s critical to get a clear agreement or contract with all rights, fees, and royalty rates spelled out.

What is indie publishing? Today, “indie publishing” often refers to the community of self-publishing authors. Many years ago (prior to Amazon Kindle and especially prior to the Internet), indie publishing was a term used by small publishers who worked independently from the big conglomerates (the Big Five). The small press community will often still refer to itself as the “indie publishing” community or as “independent publishers,” but if you’re communicating within a group of authors, you can be certain they mean self-publishing. Authors must remember that “small press” does not mean self-publishing or paid publishing. Small presses, as defined by this chart, are traditional publishers who take on the financial risk of publication.

For more information on getting publishedStart Here: How to Get Your Book Published (traditional publishing)Start Here: How to Self-Publish Your BookHow to Evaluate Small Presses—Plus Digital-Only Presses and HybridsA Definition of Hybrid PublishingIMHO: A Nuanced Look at Hybrid PublishersShould You Traditionally Publish or Self-Publish?Earlier versions of the chartClick to view or download earlier versions.

2023–2024 Key Book Publishing Paths2021–2022 Key Book Publishing Paths2019–2020 Key Book Publishing Paths2018 Key Book Publishing Paths2017 Key Book Publishing Paths2016 Key Book Publishing PathsThe Key Book Publishing Paths (2015)4 Key Book Publishing Paths (late 2013)5 Key Book Publishing Paths (early 2013)December 26, 2024

My 2024 Year-End Review: Most Notable Publishing Industry Developments

Photo by Kampus Production

Photo by Kampus ProductionIn my paid newsletter, I regularly report on and analyze what’s happening in the book publishing industry. Here’s a recap of the issues and trends I find most notable and meaningful as we move into 2025.

Best news for authors: increasing and profitable partnerships between self-pub authors and traditional publishersWhile traditional publishers have always picked up successful self-published work, I can’t recall seeing more examples, on both a large and small scale, in prior years. The strategy and success of Sourcebooks’ Bloom Books imprint, an imprint formed specifically to partner with self-published authors, has spread to other imprints at Sourcebooks. Sourcebooks also established a new imprint, Hear Your Story, built on a self-published series that’s been selling terrifically well. (Read my conversation with the team, including CEO Dominique Raccah, from February 2024.) Sourcebooks’ majority owner is Penguin Random House, the biggest of the Big Five publishers.

A bestselling nonfiction title on TikTok, The Shadow Work Journal by Keila Shaheen, was picked up this year by Simon & Schuster as part of a five-book deal. Shaheen reportedly received a seven-figure advance and a 50-50 profit share. Indie cookbook authors, too, have been avidly signed; an example is Matthew Bounds, who I interviewed in August.

When I started digging further into the trend, I found that nearly every bestselling self-published romance author has an agent and a track record of subsidiary rights deals with traditional publishers; authors are able to retain ebook and audiobook rights if they wish. New literary agencies outside of New York City have sprung up to support these authors as well.

I believe it’s by far one of the best industry developments I’ve seen in recent years: good for authors, good for publishers, and possibly great for the future of the author-publisher relationship. Which brings me to …

Startup of the year: Authors EquityIn March 2024, a new publishing company—Authors Equity—launched, offering authors 60 to 70 percent of profits from book sales but no advance. It was founded by Madeline McIntosh, former CEO of Penguin Random House. What I find particularly interesting about the company: The investors are successful, established authors. They include James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, which has sold more than 15 million copies and is published by PRH; Tim Ferriss, author of five number-one New York Times bestsellers (most of his books are published by PRH); and Louise Penny, a Canadian bestselling author of countless mystery novels (one of her publishers is Macmillan).

Some have criticized Authors Equity for not hiring a full complement of in-house editors, designers, etc. I find this criticism baffling because part of the point of Authors Equity is to give authors the freedom and power to determine their own creative team for their project. And one of the challenges of traditional publishing is that sometimes authors end up with mediocre or unenthusiastic editorial and design help—especially editors with limited time to edit.

Others find Authors Equity no different from hybrid publishing or paid publishing arrangements. That I understand, but there are differences. Authors Equity is as selective as any traditional publisher (I cannot tell the average author to go work with them—they would be rejected), and they’re not selling publishing packages or trying to upsell authors on additional services that sometimes add little value. Nor are they charging fees year after year to keep books in print or maintain the author-publisher relationship. In other words: Authors Equity has far more in common with traditional publishing (comparable to what Sourcebooks is doing with self-publishing authors), and I’d consider any author working with them to have scored a great deal. Here is my initial coverage from March. At the time, their first list hadn’t been announced. Now that it has, I think it supports my initial arguments about Authors Equity.

More successful than I anticipated (so far): Spotify’s entry into the audiobook marketIn late 2023, Spotify announced that it would start giving premium subscribers 15 hours of audiobook listening at no additional charge. While it has made some pricing tweaks along the way, that offering for premium subscribers remains in effect. All major publishers continue to be on board with Spotify’s program, despite their reluctance to enter into similar subscription programs offered by competitors.

Now that we have a full year’s worth of book sales data since the launch, it’s clear Spotify has had an effect on the market, boosting audiobook sales by about 10 percent. Storytel, a competitor, credits Spotify for having “made the cake much bigger” by converting music listeners to audiobook listeners. However, it’s unclear to me whether this growth will continue. For now, publishers tout their audiobook growth, with audiobook sales often outpacing ebook sales.

Spotify has always argued there’s a bigger market for audiobooks that hasn’t been tapped because of distribution and discoverability barriers. For example, there’s the “credit worthy” problem in the Audible market: Consumers are less likely to choose shorter books, children’s books, or any book that doesn’t feel “worth” their monthly credit. But with hours-based listening, Spotify is offering subscribers the flexibility to mix it up, explore a range of books, and pick the right book for any moment.

Spotify is absolutely correct that the credit model has warped how consumers buy audiobooks, pushing consumption toward frontlist and bestsellers. In Europe, where subscription programs (e.g., Storytel) dominate, consumption is backlist dominant. Where I have questions: (1) How many Spotify customers go beyond their 15 free credits and pay for additional credits? (2) Is outright credit purchasing or audiobook purchasing necessary for this to be sustainable for Spotify? (3) Whatever publishers have been getting paid by Spotify—and it is a near certainty the biggest publishers receive payout rates that are the same as an audiobook unit sale elsewhere—can and will those rates continue? Were publishers given more money up front to participate? Is Spotify taking a loss right now in the hopes of building a program and audiobook customer base that will be profitable in the future?

Biggest horse out of the barn: AI licensing at a Big Five publisherEven as publishers and media organizations sue OpenAI for copyright infringement, others are deciding to extract as much money as possible through legal licensing arrangements. Some of the most notable companies that have decided to take the money: the Associated Press, Politico, Business Insider, the Financial Times, Dotdash Meredith (the biggest US magazine publisher), News Corp (Wall Street Journal, New York Post, and many other newspapers), Vox Media, and The Atlantic.

The most recent to take the money? HarperCollins. They are the first Big Five publisher to strike an AI licensing deal, in this case with Microsoft for an unnamed model. I find it highly unlikely they will be the last, and AI models and licensing won’t abruptly come to an end because of author outrage or disgust—although authors absolutely have the legal right to opt out of such training. Still, I agree with the Authors Guild statement that says, “It is important to understand that the licensed use of books must replace AI companies’ current unlicensed and uncontrolled use. Moving to a regime of licensed AI use gives authors the power to say no or to insist on limits on output uses and be compensated. The current regime, which relies on fair use, means that authors have no ability to prevent use of their books by AI or control output uses.”

The question of what material AI companies can legally train on without permission or licensing remains open and will ultimately be decided in court.

December 13, 2024

Authors: Think Twice Before Paying to Exhibit at Industry Book Fairs

Photo credit: Clarissa Peterson / CC BY-NC-SA

Photo credit: Clarissa Peterson / CC BY-NC-SAUpdate (December 2024): In 2012, I wrote an earlier version of this article as a warning to self-published authors who fall prey to scams that take advantage of the highly recognized industry trade show, BookExpo (also known as BEA).

BookExpo no longer exists, but there are other trade shows, especially international trade shows, where the industry gathers. A few of the biggest include Frankfurt Book Fair, London Book Fair, and Bologna Children’s Book Fair.

While these trade fairs do what they can to educate and protect authors from making expensive mistakes, be smart and do your research before you make any trade show (those meant for publishing industry professionals and employees) part of your marketing, publicity, and PR plan. Most authors should not pay for visibility at these shows if they are not in attendance themselves in partnership with a publisher, agency or some other organization.

First, a little background: What are publishing industry trade shows?Trade shows are large gatherings of publishing industry professionals, primarily publishers, literary agents, book scouts, and people who sell/buy rights or license intellectual property. They are important primarily to large traditional publishers.

The bulk of any trade show consists of an exhibit floor where publishers purchase booth space to show off their upcoming titles (and authors), sell rights, and network with colleagues. There’s typically a separate rights area where literary agents have tables. Important distributors, retailers and service providers may also exhibit or attend.

Do authors attend trade shows?Yes, but usually at the invitation of their publisher or some other organization—sometimes the trade show itself. Every year, traditional publishers decide what specific titles they want to market at trade shows, and may invite the authors to do signings or events meant to bring visibility to the work pre-publication. Remember that “visibility” in this context means visibility to the trade (the industry), not visibility to consumers.

Sometimes self-publishing authors (typically those who are bestsellers) will also attend because they have rights deals to conduct or otherwise have numerous business partners at the show.

Should authors attend a trade show?If you’re a professional author with a significant history of sales, and already know of other professionals you could potentially meet and network with, then it may be a good opportunity to attend. However, this is not a good opportunity for an author who has just published their first book, and thinks attending might fix their marketing and promotion problems. It will not.

Most important, trade shows are not a shortcut to getting up close and personal with traditional publishers or literary agents, in the hopes one of them will publish or represent your book. You’ll greatly annoy people if you go pitching on the floor, unless it has to do with subrights or licensing. If that is indeed your goal, you should have a very polished pitch, and demonstrate a successful track record. Best-case scenario: set up meetings in advance and don’t ambush people.

Most trade shows are not interested in unaffiliated authors walking the floor, because every editor/agent hides from the author who is pitching their work, especially self-published work that hasn’t sold well.

Avoid paying to have your book promoted at trade showsThere are a handful of opportunities for self-publishing or independent authors to get visibility for their work at trade shows even if they do not attend. As far as I’m concerned—as someone who attended these shows for 20+ years—it is not worth the investment. Here’s why.

The emphasis of the show is on traditional publishing, rights sales and pre-publication marketing, and does not favor self-published title promotion. These are massive, busy shows where traditional publishing insiders talk to other traditional publishing insiders. Yes, there may be some librarians and booksellers, but they’re rarely paying attention to the places where a self-published book may be showcased or promoted.Nobody is going to notice your book there. Your book is likely to be promoted with many other books, with no way of attracting attention even if someone did pause for a second within 50 feet of your book. Imagine setting a copy of your book down in the world’s largest book fair, and expecting someone to not only notice it, but be entranced by it so much they can ignore 10,000 other things happening at the same time.If you—the author—are not present to advocate for it, your book doesn’t stand a chance. Services that offer to promote your book are rarely, if ever, hand-selling or promoting your book in a meaningful way. But they will be happy to cash your check and say that your book had a “presence” at the show. If you want to satisfy your ego, go ahead. But it’s not going to lead to meaningful sales. (I challenge anyone in the comments to provide evidence that a self-published book gained traction at a trade show because the author paid a fee to secure placement—and the author was not present.)Trade shows are quality events, and they present a legitimate marketing and promotion opportunity for some authors and some books. But for the vast majority of authors, it does not make sense to invest what are likely your limited resources in these shows.

For more insight and adviceRead Orna Ross at ALLi on what book fairs (may) offer indie authorsIndie author David Gaughran has long warned against book fairsDecember 10, 2024

What If You’re Writing Novellas? Now What?

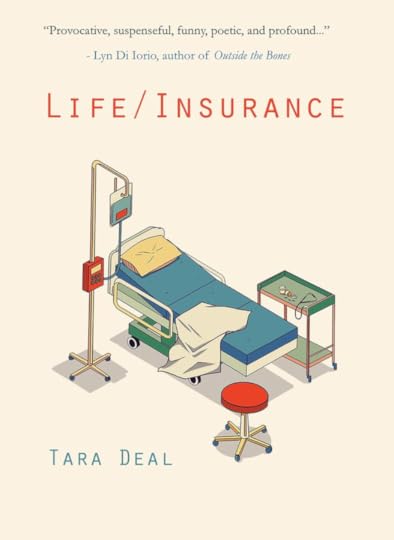

Today’s post is by author Tara Deal, whose novella Life/Insurance is out now.

Pretend you’ve written a novella. And it wasn’t easy. But now it’s done and you’re finished. Now what?

It’s difficult to find someone who wants to publish it. No one wants to spend money on such a little book (whether you’re a publisher or a customer). But what if a novella is all you’ve got? What if a novella is what you love? What if you’ve tried to write a novel, believe me, you’ve tried, because everyone you know thinks you should just write a bestseller and be done with it, how hard could it be? But no. A novella is better. Is that what you feel? A novella is perfect, perched between prose and poetry, allowing the reader (not to mention the writer) plenty of space and time to think about things.

But now that you’ve finished it, what are you going to do with it?

Years ago, after I’d finished what would become my first published novella, I was ready to move on to writing something else (I didn’t realize it would be another novella), but I didn’t want to abandon the one I’d just completed, not yet. It felt like an accomplishment. I wanted to do something with it. Like most writers, I wanted someone else to read it. I wanted to do everything I could for that novella, to give it a chance to exist in the world. Was there someone I could send it to?

Publishers and agents and literary magazines didn’t seem interested in novellas. Or, rather, they didn’t seem interested in a novella from an unknown person. But I didn’t have any connections in the world of literary publishing. I didn’t know anyone. I still don’t.

But what about a novella contest? That was something else. I did some research. Anyone could enter, supposedly. It would be like winning the lottery.

Bookshop • Amazon

Bookshop • AmazonIt might take a bit of work to find the right contest (and you don’t want to enter them all because entry fees add up and you need to save some money for non-novella-publishing pursuits, more of which later), but here are the contests that worked for me.

My first novella, Palms Are Not Trees After All, won the Clay Reynolds Novella Prize from Texas Review Press, in 2007. My second novella, That Night Alive, won the 2016 novella prize from Miami University Press. And my third novella, Life / Insurance, won the Fugere Book Prize from Regal House and is published today.Having won three contests and entered a thousand more (well, I wish there were a thousand novella contests one could enter), I have some tips. Some maneuvers you might want to consider. To put yourself in the best possible position to catch that bit of good luck that is, in the end, the most important thing that is required to win.

1. Do not join a writing group or get input on your manuscript.You don’t want your eccentricities to get flattened out, or deleted entirely. A novella doesn’t need to be a regular story. It can be unclassifiable. People won’t mind. (You can read anything for half an hour! Although, ideally, your novella should take somewhat longer than that to read—or write.) But you don’t need all kinds of character development or emotional entanglements or historical drama or romantic fantasies. You can just write what you like to think. You can play around with the format. I like to write in discrete blocks of text. I don’t like any dialogue. Is that what makes my books stand out? I don’t know. All I’m saying is that maybe your quirk (but not a gimmick!) will grab the random contest reader’s attention after she’s seen too many other things that didn’t make her jump. Think about it. How many times have you tried to read a novel recently and then given up because it’s so boring?

2. Clear out “excess, explication, or autobiography.”That’s Ezra Pound talking about poetry. But I think that’s especially good advice for a novella (or for anything, probably). However long your novella is now, cut it in half (okay, by a third). It’s nice when a novella approaches an elongated prose poem. Which brings me to:

3. Don’t write an elongated prose poem—or even worse, a short story.This is just me, but I hate short stories. If I’m going to read something short, I want something really short (poetry, flash fiction). Although I also enjoy something extra long (say, the multivolume My Struggle by Knausgaard or, from the olden days, Ulysses). The novella, unlike the short story, hits the sweet spot between these two extremes. The novella is an in-between thing that moves from the miniscule to the metaphysical and back again. Or so it seems to me. It’s nice to aim for this chimera-like creation (“an imaginary monster composed of incongruous parts” and also “an unrealizable dream,” according to the dictionary). I love a novella. The heart wants what it wants. The world is an enigma.

4. But what do YOU want? Why are you writing a novella at all?Think about it (but not forever; don’t get depressed; there’s no time to waste). Write what is required. Write what you can’t avoid. I wanted all of my novellas to become novels (in order to make some money; novellas aren’t going to get you anything), but they failed. The novella is the form that the work had to take. I couldn’t make it any longer. I tried. I couldn’t make it any shorter. The form and content found each other. Like magnets. Like magic. Like a magician, you have to keep working until things come together seamlessly, until your art becomes invisible to the audience. Take your time. I once went to a magic show and the magician said that his main trick, a card trick, took him 36 years (or some such) to perfect, and he was still working on it. A novella probably won’t take that long, but maybe? (My last novella, 163 pages, took 10 years, from start to finish.)

5. Which doesn’t mean you should rework your novella to death or let it take over your life.When the manuscript seems finished, or close enough, stop. Put it away for a few months (or a year if you have time to waste), then reread it again, then submit it. (Unless the manuscript makes you cringe, in which case, shred it.) And then forget it. When I won my second contest, I couldn’t even remember which manuscript I had submitted! (Keep a database to help keep track of things like this.) And when you’ve dispensed with that novella and put it out there and done all you could for it, after you’ve made your small contribution to the art of this world, even if it comes to nothing, and you’re ready to move on, then reward yourself and take a break. You don’t have to start another novella, not right away. You can do something else. Refresh. (Which will give you time to start thinking about writing another novella, and who knows, that next novella might be just the thing.) In the meantime, try something like jewelry making (I make my own earrings) or painting nude figures (I accidentally did this when I thought I had enrolled in a class on abstraction) or bookbinding (yes) or whatever. The world is full of things other than novellas, apparently. (You can use whatever you learn from these adventures in your next book. A couple of telling details are all you need in a novella.)

6. When you do submit, embrace the blind contests.I, for one, love a blind contest. I don’t have to worry that no one will have heard of me. If someone hates my work, who cares? They don’t know who I am! I would publish anonymously, too, if I could. Imagine if we could all just read interesting books without worrying about who the author is. That would be a beautiful world. In the meantime, we have blind contests and that fine feeling of submitting your best work, with all its quirks and experimental bits and lyrical prose and insights into the human condition and references to paint colors and impasto techniques, then waiting a year or so or more to hear back and then receiving, should you win, very little money for your oversized efforts (plus the requirement to do your own publicity, which might include things like writing short essays about writing novellas.) What more can I tell you?

Good luck! (Have fun.)

December 4, 2024

What the MFA Does and Does Not Do for Aspiring Novelists

Today’s post is by MFA director Nancy Wayson Dinan.

I wrote my first novel mostly on vibes.

That’s not quite a fair statement. At the time, I had an MFA in fiction, and I was working on a creative writing PhD. I’d gone to graduate school because I wanted to write books, and I do believe that, in school, I got better at writing. [Editor’s note: Need a definition of MFA? Start here.]

What I didn’t get better at was understanding novel structure. And when it came time to query and later promote my book, I had no idea what I was trying to market. I liked the book, and I still do, but I think a lot about what I would do differently now.

In the first edition of The Business of Being a Writer, Jane Friedman states that “it’s not an exaggeration to say that an MFA could even be detrimental to a successful freelance career, because it trains you to be aware of how writing succeeds not on a commercial level, but only on an artistic one—which you may then need to be trained out of.” As the director of an MFA program, and as a working novelist, I find myself agreeing with this statement. One of the things I wrestle with as an instructor is how to make the MFA a more useful degree for aspiring commercial novelists. At the same time, I’m thinking about how to recreate the most useful parts of the MFA experience for novelists who can’t devote years to graduate school.

Now in my classes, we explore the differences between art’s success on a commercial level versus on an artistic level, and what those terms mean. We also look at what the MFA doesn’t usually do, which is the in-depth and explicit craft work that most aspiring novelists crave. We also talk about what the MFA does do—providing professionalization, feedback, and the opportunity to see and submit work in progress—and we discuss ways in which a novelist can learn those things without a graduate degree. I would argue, by the way, that all aspiring novelists should be doing these things, with or without the MFA.

Art’s Success on a Commercial Level Versus on an Artistic LevelWhen I first encountered Jane Friedman’s quote, it stopped me in my tracks. I felt I knew instinctively what it meant—in the MFA world, we often push back against the idea that MFA graduates’ work often sounds the same. I also know many MFA graduates who spend years writing their first novel, sell it (sometimes for a great deal of money), and then flounder writing the next one. Something about being overly invested in the artistic side of writing can really mess with your writing and selling of books.

But part of me, too, resists this idea. What could possibly be so wrong about learning how to write on an artistic level that MFA graduates must then “be trained out of?”

This is a tough question to answer, and I could actually write pages just trying to define my own stance here. Instead, however, I want to reference Robert McKee’s Story, which does a great job of discussing how artistic merit differs from commercial merit in the screenwriting industry. (By the way, I want to make a case that novelists can learn a lot from screenwriting texts!)

In Story, McKee argues that there is a classical design for storytelling, and here’s where the commercial side lies. Readers expect a chain of cause and effect, a closed ending, linear time, and an active protagonist, among other things. Language might not be the focus of a commercial novel, but that doesn’t mean the language is less skilled—it just means that the story is the focus of a commercial novel, and we expect that story to have some conventional structure.

McKee also discusses other forms of story, noting that, as we move away from that classical story structure, we encounter open endings, more internal conflicts, passive or multiple protagonists, nonlinear time, or inconsistent realities. In other words, something that pulls the reader away from that classical story structure, and here’s where the literary novel goes. It might focus on language or on invention or on a unique structure, but it departs from the expected beats of commercial structure. And this is not necessarily a bad thing—many readers love this sort of experimentation. What it does do, McKee warns, is that it shrinks the possible audience of the work, though the audience might now be more dedicated.

In MFA programs, we’re often encouraged to seek alternatives to traditional storytelling, to focus on character and not plot (though, for many reasons, I think this is a false dichotomy). We’re taught to value language and image more than a strong chain of cause and effect. It’s not that we’re actively told to avoid the traditional modes of storytelling, it’s just that other modes are privileged. And when we do see a genre piece in workshop, there’s often a palpable disdain (though this attitude is changing and not something that would ever happen in the program in which I teach).

If literary fiction is what you want to write, then that’s great—here’s where I might slightly disagree with Friedman’s point, because if that’s what you want, then you don’t need to be trained out of it. But if you want to write for a commercial audience, the MFA might not be the best place to learn to do that.

What the MFA Does DoProvides ProfessionalizationUnfortunately, this is an opaque industry, and it keeps its secrets well (though, thanks to resources like Jane Friedman’s blog, things are becoming more transparent all the time!). One of the things the MFA does do is teach you how to be a professional, but you have to be willing to learn.

You have opportunities to meet visiting writers, to attend conferences, and to learn how to handle being edited. You spend a lot of time reading writers that are part of the national conversation and being explicitly invited into conversations that discuss major issues in our field. At some point, you will likely have an opportunity to ask questions of a literary agent (usually done via zoom), and that agent will likely tell you about the querying and submission process. You might meet an editor in the same way. You will often have an opportunity to work on a literary journal, to peek behind the scenes. All of this access, though it doesn’t translate into you getting an editor or an agent or a publication, invites you into the industry in a very specific way.

How to find professionalization without an MFA program

Find writing organizations, and particularly genre groups: Several years ago, I recommended Romance Writers of America to nearly every writer who turned in a story with romantic elements. They were fantastic at professionalization, especially for novelists who were just starting out, but after some well-publicized issues, they seem to be in a rebuilding phase. For now, I recommend organizations like SCBWI (the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators), SFWA (Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association), WFWA (Women’s Fiction Writers Association), and MWA (Mystery Writers of America). If you can, go to a conference. Join a local chapter. Get involved in whatever way you can.Gives You Feedback and Allows You to Submit and to See Work in ProgressAn MFA also gives you feedback on your work, both from your peers and from your instructors, who have hopefully published something in the field and have been professionally edited. Giving feedback is more important here than receiving feedback—you are not likely to publish anything you present in your first year or two of workshop, and you’re probably not even going to publish your thesis, though some writers do! Instead, what this process teaches you is to edit yourself, to see what you’re missing in story and language and motivation, to push a nascent draft into a more developed draft.

In fact, I think this is one of the biggest benefits of the MFA, this opportunity to submit and to see work in progress. You get to experience the development of fiction, not just the finished product, and this can be really helpful. Over the course of two years of workshop, you’ll submit maybe a dozen or so pieces, but you’ll read and respond to hundreds.

You also get to see creative attempts that never go any further. Seeing these false starts is so important for a writer—it takes some of the pressure off. The best writers try things, and sometimes, those new things don’t have legs. It’s okay, and a valuable lesson to learn. You’re almost always a better writer for having tried, because you taught yourself something.

How to give and get feedback outside of an MFA program

You’re going to have to find a critique group or partner, and preferably one who is just as serious as you are about craft. You’re going to need to learn to read unfinished work, and that’s harder to do with someone who’s at a more beginning level than you are. I recommend, again, the genre groups mentioned in the previous answer, as they often have matching programs. Your local library is often a good source—do they have resources for creative writers, including groups that meet? Can you take a class at your local university or extension, and then try to make connections with your classmates that will last beyond the semester? Can you join an online group?A more expensive but very personal option is a book coach. Having a book coach is like having a workshop every week, only your work is always the focus. You can learn a lot very quickly from a good book coach, but you also don’t get the chance to see other people’s work and to train your editorial eye.Be careful with your critique group. You want readers who encourage you, who make you excited to revise. You don’t want—and you never want to be—a reader who makes the writer want to quit writing. (Also, if this does happen to you, recognize that this is almost always coming from a place of insecurity.)Surrounds You with WritersIn your program, you’re surrounded by writers, and since you’re part of this community, you start thinking of yourself as a writer. You have conversations about writing, about POV, about what makes Lauren Groff or Jesmyn Ward so dang good. You learn to take yourself and your craft seriously.

But you also learn to deal with artistic jealousy, to handle a competitive feeling, to genuinely feel joy for somebody else’s success. To get excited when you see the publication of a piece that you saw in its very early stages. To marvel at how far your friend has come, and to realize she might be thinking the same thing about you.

Again, super valuable experience. You don’t have to do an MFA to find a writing community, but you enter the MFA with a cohort, people with whom you’re thrown together.

How to find community outside of a program

You probably already know what my first answer is going to be here: those genre writing groups. One of the most useful things about these communities is that everybody takes each other seriously. You’re rarely going to find a pereson who would ask you why you’re wasting your time with your little writing hobby when you have a family/job/significant other/etc. Social media seems to be good in this space, and Facebook is still one of the best, I find. These days, I only keep my Facebook account for writing, and I’m a member of AWP Community of Writers, WFWA Members-Only, Female Writers, Writers Helping Writers, Women Writers, Women’s Books, Creative Writing Pedagogy, Binders Full of Creative Nonfiction, alumni groups, conference groups, among many others. Find your spot out there—there are a lot of options!Find what your local community has. The library, again, is a great place to start, as are extension classes.Gives You a Credential to Teach in Higher EducationThis is the only part of the MFA experience that you really can’t recreate. If you want to teach in higher ed, you will need at minimum a master’s degree, and even this is usually not enough for a tenure-track job. No amount of writing workshop or conference experience can duplicate this credential.

The unfortunate other side of this point, however, is that the MFA (or a creative writing PhD) does not guarantee you a job. In fact, there’s no way that it can—every year, programs graduate far more degreed writers than there are jobs available. Any university creative writing program will tell you about the hundreds of applicants for each job opening. That’s not to say that you can’t get a job teaching creative writing, but that the odds are against you, and you shouldn’t attend an MFA program just to get that teaching credential. However, many of our graduates teach K-12, and in many states, a master’s degree means an automatic bump in pay, so the MFA can definitely pay off in this way. (I also have thoughts about how to be much more competitive in the tenure-track professor job market, as well!)

What the MFA Does Not Usually DoIn-Depth and Explicit Craft WorkIn an MFA program, you will read a lot and write a lot, and of course, these two activities are the most important craft work you will do. However, when I say that the MFA does not provide in-depth and explicit craft work, I mean that you are not going to encounter craft books that teach you how to do specific things with narrative. You’ll likely encounter craft essays, such as many by Flannery O’Connor or Richard Russo, that will advance a theory or aspect of fiction, but you won’t get instruction that says here’s what an audience expects after the inciting incident, or here are the usual components of a satisfying ending.

I still occasionally meet up via zoom with writers from my PhD program, and I find it interesting how we all went through the program without this type of instruction, but how we all found ourselves, unbeknownst to each other, finding the same craft books after the program was over. Writing a novel is like entering a wilderness, and it is really helpful to have signposts helping us to navigate. Craft books can provide these signposts. How do I tell a story? Robert McKee’s Story and John Yorke’s Into the Woods are fantastic resources (again, both screenwriting resources!). How do I develop a character? Lisa Cron’s Story Genius and Wired for Story are amazing. How do I approach structure (Save the Cat! Writes a Novel is a good basic place to start), navigate plot twists (Mastering Plot Twists by Jane Cleland), or develop my prose (Steering the Craft by Ursula K. LeGuin)? The point is that, even if you do get an MFA, there are times as writers when we’re out there on our own trying to get better. These craft books are a very good place to start, and I’m beginning to include these in my MFA coursework, as well.

Teach You How to Query an AgentIt just doesn’t happen, or at least, I’ve never seen it happen. Part of the issue is that, even after 3 years, most people don’t have a polished manuscript ready. You spend a year writing your thesis project, and that generally isn’t enough time to finish it and revise it. Most students leave their thesis defenses with a list of things they know they still need to work on.

But there’s also this sense that the MFA is to practice the writing side, not the business side. And I know this sentiment is changing, but you’re much more likely to find useful querying and publishing advice at a conference panel.

Plus, there are amazing resources out there: Jane Friedman’s blog, for example, has a ton of information about query letters. Literary agent Carly Watters used to host a super helpful blog, and now she is part of a podcast called The Shit No One Tells You About Writing. SFWA has a great example of a query letter on their site. Seek out quality advice and examples, and see how far you can get. And, again, those genre conferences are great—you can often sign up for a spot with an agent for a query critique.

Also, if you’re interested in the business of writing, selling, and launching a book, I highly recommend Courtney Maum’s Before and After the Book Deal.

Where I Am NowI’m doing my best to have a foot in both worlds—both the academic creative writing world and the professional creative writing world—because I believe both arenas add value to aspiring novelists. But the truth is that Friedman is right: MFA programs do not teach writers how art succeeds on a commercial level. We live in a connected world, however, one in which industry insiders often put their expertise up for public consumption.

I still remember one day in my MFA program when a professor asked me what I was reading those days. “Oh, you know,” I said. “Some craft books.” The professor looked horrified, as if I’d confessed to somehow cheating. “Hmm,” she replied. “I hope they don’t mess you up too much.” After that remark, I didn’t touch a craft book for five years, and when I finally did, I felt like the act was somehow shameful. But it’s not—let’s take the expertise where we can, especially in a profession that is often frustratingly opaque.

December 3, 2024

Create Compelling Suspense and Tension No Matter What’s Happening in Your Story

Photo by Sean Foster on Unsplash

Photo by Sean Foster on UnsplashToday’s post is by editor Tiffany Yates Martin. Join her on Wednesday, Dec. 11, for the online class Mastering Suspense & Tension.

Unless you’ve been living in an underground bunker devoid of wifi access for the last months—or let’s say decades—chances are you’ve been experiencing a fair amount of conflict and uncertainty recently.

These are uncomfortable feelings, and most of us peace- and security-craving people try to avoid them. I don’t know about you, but I’m feeling all full up on tension and suspense at the moment, thank you very much.

But as is so often the case, what makes for effective story doesn’t necessarily reflect our everyday lives, and questions, uncertainties, and friction are the lifeblood of story.

These crucial story elements may be easy to instill in scenes of setback, conflict or challenge, but not every story or scene lends itself to overt tension and suspense. You won’t always have obvious antagonists or arguments. Not every car ride ends in a crash. There aren’t knife-wielding killers lurking behind every door (hopefully).

Some stories are “quieter.” So how can you keep tension strong without scenes of overt tension and suspense?

Lean away, instead of leaning inIt’s an understandable instinct to lean in, full speed ahead, when your characters are headed in the right direction: meeting the love interest, surmounting a challenge, moving closer to a goal. But though you may be moving the story forward, if the road is too smooth, readers may lose interest.

Authors tend to relax tension in these moments: letting their characters lean into the romantic attraction, bask in the victory and enjoy the spoils, relish and flourish in the desired situation.

But tension is the rope pulling your readers through the story—and you are the sherpa holding the other end and leading them forward. The moment you let the rope go slack, movement stops. Even when the path evens out, you must keep that rope taut and pull your reader along.

Let’s use an example to explore what that looks like in story. Say your story premise is that your main character is being stalked by an ex and feels unsafe in her home, so she takes a job at a kids’ summer camp to hide out.

The bulk of the story may take place in the camp, where the protagonist makes new friends, finds romance, and discovers new purpose in her life with the job of leading the kids. But if your main source of story tension is the threat of her stalker and the suspense of whether he will find her, that’s not strong enough to sustain the entire story, and the urgency dissolves as soon as she’s “safe” at the camp. So you still have to find ways to instill every scene, every page—I’d venture to say nearly every line—with the questions and conflicts that are the rocket fuel of compelling story.

The key: Look ahead, not backward (you can’t pull a rope from behind), and focus on the obstacles, challenges, setbacks, and uncertainties in the current situation.

Rather than having the protagonist lean into what’s happening, think in terms of finding ways for her to lean away from it instead. Even amid her journey of self-discovery, look for what she resists, but what draws her in despite herself. For instance, rather than embracing the sanctuary of her hidey-hole, what if she resents having to flee? What if she’s outraged or irritated or upset about leaving her life and job and friends and everything comfortable and familiar? What if she disdains the facilities, complains to everyone around her, finds the kids annoying, phones it in as a counselor?

Authors often worry that a character and storyline like that will be whiny or off-putting or unlikable, jeopardizing reader investment. But there’s plenty of humor and pathos and even endearment to be mined from characters who bemoan and resist their situations—witness films like As Good As It Gets or Private Benjamin or Stripes or 28 Days, or books like Bonnie Garmus’s Lessons in Chemistry, Emily Giffin’s Something Blue, Jonathan Tropper’s This Is Where I Leave You, or Fredrik Backman’s A Man Called Ove.

Rather than alienating readers from the character, you can make us root for their comeuppance or turnaround or redemption. And now you’ve got the makings of a powerful character arc, and somewhere to build from in showing how your on-the-lam protagonist slowly comes to appreciate her surroundings, despite her initial resistance … and that’s where the gold lies.

Now the stakes are higher. Now we get to see how she comes to accept and then appreciate the camp’s wild beauty and the nature and people around her, and you have built-in opportunities to mine endless tension from every single scene:

Rather than relaxing gratefully into the safety offered by the camp’s remoteness on her arrival, maybe she’s horrified by the primitive conditions?Instead of feeling safe and less lonely when assigned to a bunk with three other counselors, what if she squirms at the lack of privacy, feels excluded because all of them seem to already know each other, and bemoans they’re all at least a decade younger than she is?What if, instead of leaning into her romantic interest, she resists it, still stung by her last relationship that turned dangerous and sent her running here, or put off by the other character’s relentless, irritating positivity and cheer … even as she’s powerfully drawn to that person and their annoyingly happy energy despite herself. Every rom-com writer knows that if two characters feel a potent gravitational pull to one another, delicious tension arises from resisting it, not immediately embracing it (or each other).What if, instead of leaning right into a brand-new sense of purpose with the kids, she finds the little rugrats fairly disgusting, until an out-of-control mud fight drags her into their sense of play? Or she’s hilariously inappropriate with them … yet her realness and flaws hit a chord with the kids and to her surprise they adore her and the other counselors start asking how she’s reaching them so effectively? Or she’s the only one who finally connects with the troubled little boy who doesn’t ever speak?All these scenarios give the author so much more juice to squeeze in the story, a series of little battles for your protagonist to face so you create the ups and downs that are the backbone of compelling story, instead of a smooth, boring straightaway.

And while the overarching suspense may come from the premise—if she fails or is kicked out, she’s right back in her stalker’s path—you make the stakes far greater than that by introducing new, even more meaningful suspense questions related to her inner journey: Does she have the stones to tough it out in the wilderness? Will she fail as a counselor or get kicked out and lose her safe retreat? Will she push away the love interest who is exactly what she needs to let go of her cranky or narrow worldview? Will she get out of her own damn way and embrace the opportunities she’s been thrust into?

Braiding together all these uncertainties that are directly related to her character journey weaves a rope strong enough to draw readers all the way through. Suspense questions like this pack much more punch than just the threat of her stalker—which is merely a framing device, a setup, a thread too slender from which to hang the entire story’s tension and suspense.

No matter your genre or premise, tension and suspense are the fuel of propulsive story—perhaps never more so than in the “quieter” stories and the upward trajectories.

That’s when it matters most to keep your foot on the pedal. Remember that triumphs are most compelling when the hero has to fight for them, so give them plenty of obstacles, challenges, setbacks, and uncertainties to navigate even when they’re on the right road.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Wednesday, Dec. 11 for the online class Mastering Suspense & Tension.

November 21, 2024

In Defense of Giving Up

Photo by Sebastian Sørensen

Photo by Sebastian SørensenToday’s post is an abridged excerpt from “In Defence of Giving Up” by Stacey May Fowles in Bad Artist edited by Nellwyn Lampert, Pamela Oakley, Christian Smith, and Gillian Turnbull. Copyright © 2024 by the contributors. Reprinted with permission of TouchWood Editions.

Before my daughter was born, in early 2018, I was mostly convinced my worth lay in writing eight hundred–word pieces in very little time for very little money. As a “permalancer,” as we’re now known, I earned my living and reputation by writing frequent, short pieces about timely issues for a consistent handful of publications, delivering each on a tight deadline and then measuring my credibility via clicks, likes, and shares.

At the time, I was also pretty sure that the price of that worth was having complete strangers call me all sorts of vile names on the internet, and that the insults and threats I commonly found in my inbox were part of what it meant to be “successful.” Declining work wasn’t part of the deal, but professional exhaustion, being treated badly, hustling and fighting to be heard for very little money on very little sleep definitely was.

As far as I was concerned, suffering gracefully was what it meant to be a professional writer, and turning things down—or even creating some reasonable boundaries—meant you just couldn’t hack it. Besides, saying “no thanks” to invitations and assignments just meant that they would be handed to someone else standing right behind you, eager to take your place.

Better to be grateful, teeth gritted, with a smile on your face.

It’s no exaggeration to say that we exist in a poisonously positive culture, one that constantly discourages us from complaining, calling things out, and, of course, quitting entirely. “Never give up,” the personal mantras espouse; “Anything is possible,” the Instagram squares scream—even when we’re on the floor, unsure if we can self-care ourselves back up again.

If only I worked hard enough, I would think. If only I gave it my all, put in those extra hours, exerted myself to the point of exhaustion. If only I was really, truly committed, burning myself out in pursuit of my lifelong dreams, then I could have everything I always wanted. Then people would respect me. Then I would be successful.

In that spirit of “I can do it,” I have put off rest, and care, and healing. I have tried to prove myself worthy by what I can take, by how much I can suffer, by how far I will go—certainly not by how well I write, and definitely not by how well I can take care of myself.

And, by doing all this, I have learned a pretty nasty truth; the more you endure, the more you will be asked to endure.

It’s a well-worn cliché to say that having a baby changes you. Some would even say it’s a smug sentiment, spoken by people justifying the fact that their lives have been irrevocably altered, and not necessarily for the better. But I don’t actually think it’s necessary to have a baby to see the necessity of slowing down, of asserting boundaries, of saying a loud “no, thank you” instead of yes to every opportunity—it just happened to be necessary for me. But getting pregnant a month after that book’s launch was the invitation necessary for a genuine breather.

Professional writing and publishing culture is packed with the kinds of jobs that people respect you for but don’t pay overtime, or even that well at all. You may be admired by peers for your “glamorous” bylines, you may “matter” enough to be part of that beautiful, successful crowd, but you are also constantly on the verge of a health crisis, or an economic crisis, or a total breakdown.

That’s the thing about the pervasive culture of overwork in publishing—it does everything in its power to make you stay stuck. It builds a mystique around what you do and who that makes you, so much so that you desperately miss the frenzy when it’s gone, regardless of how much happier and healthier you are in its absence.

After some time spent being forced to slow down (my daughter turned six this year), I’m certainly no longer convinced that teetering on the edge of burnout is what success really looks like. I no longer think the only way to matter is by checking your email in the middle of the night, by over-scheduling and under-sleeping, by exposing yourself to abuse or destroying yourself in the process of “succeeding.” Instead, I’m committed to trying to find genuine ways to resist the delirious pressure to always be producing.

Bookshop • Amazon

Bookshop • AmazonWe live in a culture that urges us to never quit, that tells us we must follow our dreams at all costs, that anything is possible. But one thing this toxic hustle culture doesn’t teach us is just how healing it can be to simply surrender, give up, and let go. It doesn’t tell us how and when to release our grip or guide us to a place of acceptance and openness to what we can become after doing so. It doesn’t let on how liberating and powerful it can be to opt out and step away.

What I’ve learned is this: If something doesn’t value you, quit it. If something is actively harming you, quit it. If you genuinely hate something, quit it. Because despite what you’ve been told, despite what you’ve clung to and what people will say, giving up can actually be a very good thing.

November 20, 2024

Writing the Author’s Note for a Novel

Photo by Cup of Couple

Photo by Cup of CoupleToday’s post is by author Jennie Liu.

As writers, the happiness and relief are huge when we type THE END to our manuscripts. With each novel I’ve written, this has certainly been the case for me, but with my fourth manuscript, the sensation was slightly diminished because I knew by then what still lay ahead: writing the author’s note.

Now I love a good author’s note. I’m always eager to hear what writers say about their work. I find reading the note is a bit like chatting with the author. But for me, crafting the author’s note is an arduous task. For my historical YA novel, I spent close to thirty hours shaping and trimming down to a two-page piece.

So, what’s included in an author’s note?

The inspiration or your personal connection to the storyThis piece is likely the most interesting to the reader. It can be as straightforward as sharing the spark for your story. You might also discuss your reason or goal for writing the story, the writing process, what you discovered, or how the story changed from your original idea. You can also touch on the theme and how it relates to you personally.

Example: I started writing The Red Car to Hollywood in the spring of 2020 in response to my mounting dread and anger over the call to anti-Asian hate.