Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 24

February 27, 2025

Sometimes It IS About the Research

Photo by Joanna Kosinska on Unsplash

Photo by Joanna Kosinska on UnsplashToday’s post is by author, book coach and historian Christina Larocco.

Nearly a decade ago, I worked as a consultant on a project to digitize manuscript collections related to the women’s rights movement in the Philadelphia region, where I live. It was a great job: I spent the summer of 2016 going from archive to archive, devouring the writing of activists both well-known, like Lucretia Mott and Alice Paul, and less so, like Martha Schofield.

Schofield was born in 1839 to a family of devout Quaker abolitionists whose family farm was a stop on the Underground Railroad. She attended women’s rights conventions with her mother as early as 1854, and in her thirties and beyond she devoted herself to the woman suffrage movement. During the Civil War, she volunteered at a local hospital, which took in hundreds of United States soldiers wounded at Gettysburg and elsewhere. From 1865 until her death in 1916, she taught freed people in South Carolina and tried to stem the tide of racial terrorism across the nation.

When the project was over, I recommended that Schofield’s letters and diaries be digitized. Part of this was selfish: I had fallen in love with and started to write a book about her, and I wanted to be able to continue my research at home in my pajamas. But the reason I fell in love with her was that her papers were so different from anything I had come across in my twenty years as a women’s historian, then or since. It didn’t seem like an ethical dilemma.

Guides to women’s paper collections often issue a version of this disclaimer: “scant information about her personal life.” The first generation of women’s historians was understandably focused on highlighting extraordinary women’s accomplishments, disentangling them from home, family, and the personal or private to show what they had done in the public realms of politics, science, and the arts. For generations, it was only women whose lives adhered to male models of achievement whose papers were deemed worthy of collecting. At the same time, many public women—or their descendants, who were concerned with propriety—purged their records of anything personal.

Schofield, however, wrote about her thoughts and feelings constantly. It was this access to her inner life, not her impressive resume, that made me want to write about her.

Now, part of me worries that digitizing her papers has diluted their power, precisely in the area that first attracted me to them.

Here’s an example: one of the challenges I faced in writing about Schofield was figuring out how to characterize her relationship with Robert K. Scott, a Civil War general, assistant commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and the Reconstruction governor of South Carolina. He and Martha first met in 1866, as he traveled through the state. Late in life, Schofield confessed in both a poem and a letter to her niece that she had loved him. But you wouldn’t know it based on her extant writing from the time—she rarely referred to him by name, and she never identified him as more than a friend.

She did leave behind clues to these deeper feelings, though—ironically, more in her attempts to hide them than anywhere else. As forthcoming as Schofield was, she had a habit of destroying materials she didn’t want people to see. In 1862, she destroyed a group of letters from school friends. In 1865, she dropped her letters to John Bunting, her first love, into the Atlantic Ocean. “Destroy this unread,” she wrote years later into her diary from 1868–1869, when her best friend’s engagement led her to contemplate death.

In other words, if she destroyed it, it’s probably pretty juicy.

So it’s significant that her writing about Scott is rife with redactions. She tore out the page of her diary immediately preceding her first mention of Scott. Sections from pages covering April 1866, when Scott spent days traveling just to visit her and the two declared their love, and June and July 1866, including the day of Scott’s birthday, are neatly excised, as if cut out with scissors. Sometimes she cut out only his name, still evident through context clues.

I know these events happened because she wrote about them later. But I know how much they meant to her because she removed the evidence.

For that reason, I’m glad I first read her diaries in physical form, where I noticed the alterations immediately. They’re much less apparent, much easier to miss completely, in digital form. How can you determine that pages have been removed when only the pages themselves are digitized? How can you even begin to figure out what was on those missing pages if you don’t know they existed?

So, was it wrong to advocate for these papers to be digitized?

Of course not. In-person research presents significant barriers to access, and physical archives aren’t complete either. But it’s worth remembering that documents are objects with their own material lives, often not reproducible by technology.

Writer, book coach, and historian Christina Larocco’s latest book, Crosshatch: Martha Schofield, the Forgotten Feminist (1839–1916), is now available for preorder. This March, she’s giving away 31 free writing strategy sessions to nonfiction writers who love to gather information but sometimes get stuck in research rabbit holes. Grab your free session here.

February 26, 2025

AI & the Slush Pile: Lots of Experimenting but No Implementation (Yet)

Of all the potential uses for AI in the publishing industry, submissions management is one area where help is merited and AI use could—if one is optimistic—see potential improvement for everyone. But its use remains controversial.

This premium article is available to paid subscribers of Jane's newsletter. Login below, or learn more and subscribe.

Username or E-mail Password * function mepr_base64_decode(encodedData) { var decodeUTF8string = function(str) { // Going backwards: from bytestream, to percent-encoding, to original string. return decodeURIComponent(str.split('').map(function(c) { return '%' + ('00' + c.charCodeAt(0).toString(16)).slice(-2) }).join('')) } if (typeof window !== 'undefined') { if (typeof window.atob !== 'undefined') { return decodeUTF8string(window.atob(encodedData)) } } else { return new Buffer(encodedData, 'base64').toString('utf-8') } var b64 = 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/=' var o1 var o2 var o3 var h1 var h2 var h3 var h4 var bits var i = 0 var ac = 0 var dec = '' var tmpArr = [] if (!encodedData) { return encodedData } encodedData += '' do { // unpack four hexets into three octets using index points in b64 h1 = b64.indexOf(encodedData.charAt(i++)) h2 = b64.indexOf(encodedData.charAt(i++)) h3 = b64.indexOf(encodedData.charAt(i++)) h4 = b64.indexOf(encodedData.charAt(i++)) bits = h1 << 18 | h2 << 12 | h3 << 6 | h4 o1 = bits >> 16 & 0xff o2 = bits >> 8 & 0xff o3 = bits & 0xff if (h3 === 64) { tmpArr[ac++] = String.fromCharCode(o1) } else if (h4 === 64) { tmpArr[ac++] = String.fromCharCode(o1, o2) } else { tmpArr[ac++] = String.fromCharCode(o1, o2, o3) } } while (i < encodedData.length) dec = tmpArr.join('') return decodeUTF8string(dec.replace(/\0+$/, '')) } jQuery(document).ready(function() { document.getElementById("meprmath_captcha-67c0208e8194e").innerHTML=mepr_base64_decode("NiArIDEgZXF1YWxzPw=="); }); Remember Me Forgot PasswordEntangled launches two new YA imprints

The home of Rebecca Yarros has announced Mischief Books and Mayhem Books.

This premium article is available to paid subscribers of Jane's newsletter. Login below, or learn more and subscribe.

Tip from a reader: Metalabel for collaborations

The platform enables Substack writers who want to collaborate on creating themed collected writings in a more polished print or ebook form.

This premium article is available to paid subscribers of Jane's newsletter. Login below, or learn more and subscribe.

On the List: The Last One at the Wedding by Jason Rekulak

Jason Rekulak is the author of Hidden Pictures, a national bestseller and winner of a Goodreads Choice Award.

This premium article is available to paid subscribers of Jane's newsletter. Login below, or learn more and subscribe.

Links of Interest: February 26, 2025

The latest in traditional publishing, bookselling, marketing & promotion, culture & politics, and AI.

This premium article is available to paid subscribers of Jane's newsletter. Login below, or learn more and subscribe.

February 25, 2025

3 Little Words That Will Unlock Your Revision

Photo by Eva Bronzini

Photo by Eva BronziniToday’s post is by writer and book coach Monica Cox.

Whether it’s describing your favorite book or pitching your own manuscript, chances are you’re describing the plot or what happens in the story.

Hooks and pitches are all about plot. It’s the easiest thing to latch on to when it comes to story. Plot is often the first thing that comes to us when we sit down to write and ponder the “what if this happens” question.

What keeps our people reading, however, is the emotional journey of the protagonist and how that character arc interacts with and affects the plot. The real magic of story happens when we dig beyond “what if this happens” and ask “what if this happens to this person?”

Let’s look at The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins. The plot is what prompted me, and probably many other readers, to pick up the book—a life-or-death game where young people from each district in the nation are put in a dome together and only one can come out alive, all while the event is broadcast across the nation as entertainment.

What makes the story so resonant isn’t the series of events that could happen in a situation like this. It is Katniss and her journey through the Games. No one wants to be the district’s tribute—it’s essentially a death sentence. But Katniss volunteers for the games. Why? Not for ego or to prove something to the corrupted government (yet…that comes in a later book), but to protect her younger sister whose name is drawn in the lottery.

From the beginning, the reader knows something about Katniss and her heart that will make her someone to root for: she is motivated by love for her sister. Not only does the reader care about Katniss because of that bond, but her love and desire to take care of her family influences how she plays the game, ultimately making the story about so much more than just the plot of personal survival. Talk about emotional resonance!

Donald Maass writes in The Emotional Craft of Fiction: “What shapes us and gives our lives meaning are not the things that happen to us, but their significance.”

It’s not just the plot that makes a good story. It’s the meaning the plot has for the character. Like Katniss in The Hunger Games.

Maass goes on to say: “Plot happens outside, but story happens inside.”

Understanding your character’s emotional arc of change, how that arc plays with the plot, and how the character makes meaning of that plot are the keys to ensuring your story has a strong trajectory, propelling your reader through the book, hooked not only on plot but your protagonist’s experience of it. Your story’s trajectory is that emotional throughline that motivates your character to act and overcome obstacles in an attempt to reach their story goal. It’s the magical third rail of your story that holds up the external machinations of your plot. Without a strong trajectory, the story may just fizzle out or the reader is left wondering why they care about what happens at all.

At some point, plot just isn’t enough.

Ensuring your stories are imbued with meaning can be a gargantuan task. Luckily there are three magic words that will help you determine the strength of your story’s trajectory.

Because Of ThatAt the end of each major scene or chapter, if you were to fill in connector words between them, would they be linked by the phrase AND THEN or BECAUSE OF THAT.

“And then” insinuates that something happened to your characters. More rocks being thrown up at your proverbial protagonist in a tree.

“Because of that,” on the other hand, indicates that your protagonist has made a decision or taken some sort of action as a result of the scene propelling the reader into the next chapter where a consequence or obstacle will no doubt result from this choice.

Can you feel the difference? One reads like a litany of events while the other invites the reader to engage with the story, to deduce, suppose, and react to the actions the protagonist is taking on the page.

To check your manuscript for a strong “because of that” trajectory, start here:

Make meaning. Take a look at each scene or chapter. Summarize the plot of that scene in a sentence or two, then summarize the meaning of that plot point for the protagonist in a sentence or two. Do this for all the major scenes or chapters in your manuscript so you essentially create an outline of both the plot and emotional arc of your story.Look for connection. Now, analyze the silence between scenes/chapters and see which phrase best connects them: “and then” or “because of that”?Work backwards. If “and then” connects your scenes/chapters, ask yourself the following questions to find the problem in the previous scene:Is the problem plot or emotion? There may be too much of one or the other throwing your trajectory out of balance. Too much plot without internal meaning-making leaves the action flat. Too much internal work without a little external plot means there may be too much backstory or info dumping on the page. Take a hard look at what’s out of balance and find a way to incorporate the missing link.Does your character have agency? Are they making decisions in the scene, learning something new that will result in a new choice, taking action, making a decision, or are things simply happening to your character? The beauty in a novel length work is that our protagonists rarely get it right on the first try, so let them make some mistakes and learn some hard lessons. Just remember, that they need to be in charge, or at least think they are, by choosing to do—or not do—something in each scene.What is the scene goal? What does the character want or need in the scene? Do they get it? All the macro story goals your protagonist has should be represented as micro scene goals as well. These goals not only need to advance the plot, but also deepen the meaning for the protagonist forcing her to make scene-specific decisions that will keep readers turning the page to find out how they will impact the macro goal.Can you identify the scene stakes? There are the larger story stakes at play, always, but each scene has something at stake for your character as well, whether it’s a big thing (escaping the bad guy) or a small thing (saving face during a business meeting) based on that scene’s goal. If you can’t identify clear stakes in the scene, focus on what your character stands to lose in this moment and make sure the reader is clear on what that is on the page.Do this for every scene or chapter in your manuscript since there may be different things at play in each scene. For example, in one scene you may lack trajectory from a simple imbalance of plot and meaning, while in another, the stakes may be unclear. Working backward from the connector phrase, however, will point you to the scene or chapter prior to see where you may need to focus your revision work.

Then, as you move forward through your revision, you will be able to strengthen the ultimate trajectory leading to your inevitable and impactful story climax. Because of that, you will have a story that keeps your readers turning pages to see what happens next.

February 19, 2025

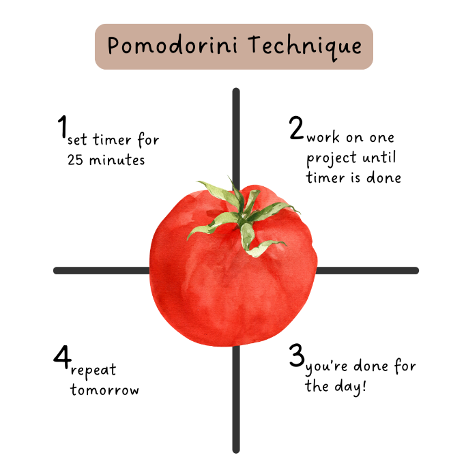

A Tiny Tomato a Day Keeps Writerly Woes at Bay

Photo by Karolina Kołodziejczak on Unsplash

Photo by Karolina Kołodziejczak on UnsplashToday’s post is by doctor and novelist Emma Olive Billington.

I’ve been known to ruin dinner.

Not because I’ve cooked something inedible (although that does happen), but because I am miserable company. Why? Because I am not making progress with my writing.

I’m a doctor and medical researcher who caught the unshakable urge to write a novel in 2019. Six years later, I’ve had no success in finding a cure for the compulsion to write. Worse, I’ve become all too aware of the ill-effects that not writing have on my mood and well-being. The obvious treatment would be to, well … write. And yet, I often have difficulty prioritizing it. As an unpublished hopeful, it can feel difficult to justify taking time away from more urgent (and lucrative) responsibilities to write fiction.

As a result, I would find myself in a self-perpetuating cycle. I’d push off writing one day because I was too busy. That day would turn into a week, and before long, I’d be in Ruining Dinner Mode. Because I didn’t have a reliable way to break the cycle, I’d often be stuck for months before finding my way back to my writing.

That is, until I discovered the life-changing magic of tiny tomatoes.

Like many writers, I have long been familiar with the Pomodoro technique. It’s even been discussed on this blog. Developed in the 1980s by an Italian university student who used a timer in the shape of a tomato—pomodoro in Italian—to break his study sessions into manageable chunks, this technique has become one of the most popular productivity hacks in the book. Not surprising: it’s simple and free. The only equipment you need is a timer. (I use this app, but you can also use your phone timer or the OG tomato timer if you like.)

Here’s how Pomodoro works: Set your timer for 25 minutes. Work on a single task until the timer goes off. Take a five-minute break. Repeat the cycle four times, then either stop for the day or take a longer break (usually 20–25 minutes) and repeat.

The Pomodoro technique is great. It activates my concentration and allows me to produce high quality work. In fact, I use it frequently for my day job. But when I’m in “Ruining Dinner Mode”, the classic Pomodoro method (4 cycles) isn’t always effective for getting me back into writing. By that point, either it’s been so long since I touched my work in progress that spending two hours with it feels impossible, or my schedule is so packed that no amount of calendar gymnastics will provide a consecutive two hour gap. I need something with a very low barrier to entry.

Enter the Pomodorini, or “tiny tomato” technique.

Here’s how it works: Set your timer for 25 minutes. Work on a single task related to your work in progress until the timer goes off … and that’s all! You’re done. Repeat tomorrow.

I’m aware of how silly this sounds, but the Pomodorini technique has changed my life. In the year I’ve been using it, I’ve made progress on my writing more days than not. I’ve pulled apart my first novel, put it back together, and drafted a second novel. There are still periods of time where I’m not writing, but my mindset around those has shifted now that I have an easy way to get back into it.

Importantly, Pomodorini has also made me more pleasant to be around. It is now safe to invite me to a dinner party! (Ina Garten, if you’re reading …)

If you’re interested in trying the Pomodorini technique to reignite your creative life and improve your writerly wellbeing this year, here are a few tips you might find helpful:

1. Start low. I do no more than a single 25–minute session a day for the first week. You might even choose to skip a day or two if you know you’ll be busy. You want this to feel easy!

2. Commit and defend. Once you’ve decided on your session frequency, schedule the sessions in your calendar. Defend this time as if your life depends on it!

3. Try not to be too prescriptive. I usually use my Pomodorini sessions to draft or revise my work in progress. However, on days when my brain refuses to engage in either of these tasks, I let myself use the time for anything that will ultimately push my writing forward. This could be reading a chapter of a craft book or a potential comparative title, researching something relevant to my story, working through a plot problem, or even re-reading my draft. My only rule here is that I must decide what I’m going to work on before starting the session and I can’t abandon ship partway through.

4. When the timer’s done, you’re done. I know that the ‘Pomodorini magic’ is happening when I find myself tempted to sneak in a few unscheduled writing sessions. I try to avoid doing this. I want to keep the momentum going—it’s easier to pick up again the next day if I’m itching to write again, than if I’ve exhausted my writing energy with a marathon session. Instead, when I feel momentum kicking in, I’ll increase the number of days or sessions I schedule for the following week. The key here is to go slowly—you want to make sure you’re being realistic about how much time and energy you have for writing.

5. It’s okay to stop. The point of Pomodorini isn’t to keep doing it forever. It’s to get you out of a creative slump. At some point, either your writing will become so embedded in your routine that you no longer feel the need for a timer, or you’ll hit a roadblock and fall off the writing train again. Both of these situations are expected and normal. Don’t stress: your timer will be there whenever you’re ready to start again.

If you’re in a creative rut, I hope my experience has inspired you to try Pomodorini for a week. If, on the other hand, you think Pomodorini sounds completely ridiculous and only read to the end of this post because you were hoping I’d talk about real tomatoes at some point, here’s my attempt to appease you. This recipe for Baked Feta Pasta with Jammy Pomodorini is guaranteed to save any dinner from the writerly woes.

February 18, 2025

Too Intimidated (or Risk Averse) to Organize a Writing Retreat?

Photo by Sarah Noltner on Unsplash

Photo by Sarah Noltner on UnsplashToday’s post is by writer and book coach Amy Goldmacher. She is leading a cruise writing retreat September 3–10 from New York City to Southampton, England, on the Queen Mary 2.

In the fall of 2022, I went on my first ever writing retreat, a week in Tuscany in company with ten other writers and two respected instructors. I went with the expectation of generating new words on a new project—and instead pivoted and got feedback on a manuscript draft, which I edited when not in group sessions, group meals, group tours, or taking naps to manage the jet lag. I had an amazing time, enjoyed myself immensely, and got a ton of value out of being with a group and revising existing work.

And yet I also thought to myself, “I would design a retreat differently.” But I felt I didn’t know how.

So I took a workshop on creating retreats that sell to flesh out my idea into a plan and a budget. I focused on the value of what I was delivering in addition to creating logistical line items for food, transportation, and lodging for participants.

And then I chickened out. Faced with the financial reality of putting down deposits for hotel rooms and catering without a guarantee that I could fill the retreat and recoup my investment, I decided to not do it.

But I still had a vision of what my ideal writing retreat would look like.

So I took myself on a transatlantic cruise and called it a writing retreat in the fall of 2023. I had a list of things I wanted to work on during this time. Without any group obligations or schedules, I was able to relax and focus on my work. While having all my meals taken care of! And with limited distractions, as I chose not to participate in any of the ship’s entertainment options during the daytime!

Still too chicken to offer my own retreat, I nagged asked the instructor of the Tuscany retreat if I could coach alongside her on her first cruise writing retreat—and she said yes. The retreat on the ocean liner was structured very similarly to the Tuscany retreat: each day had several group sessions and a group dinner; writers could choose how they wanted to spend their free time on the ship or opt in to one-on-one sessions with instructors. It was a fantastic experience, even though it cost me more to go on the trip than I received in remuneration. I went into it knowing that it was my choice to invest in getting this experience in this way. The payoff for me was being able to work with writers individually (and in the group sessions as well) and see them think of their work in new ways, try new techniques, and find new solutions through our time together. And, down the road, several writers came to me for paid coaching, so that retreat will eventually pay off for me in financial ways.

Which brings us to 2025. Now that I have been on a retreat as a writer, taken myself on my own retreat, and co-led a retreat, can I finally lead my own retreat despite the risks?

Yes!

What changed?

I have more confidence after having “retreated” as a writer and as a co-teacher. Some of my fears of hosting my own were related to not knowing what I didn’t know. So I was my own guinea pig.There will always be things out of my control as a host. I can’t control travel costs or cabin availability or whether anyone will sign up, but I can talk about the retreat where I have a presence and I can talk about the benefits of this particular retreat for writers who are interested in this particular retreat.I accomplished a lot on my retreats, even if it wasn’t what I intended at the start—so I can attest that spending time on a retreat is worthwhile.I can share my ideal retreat with others, and those who want to experience a retreat like this will choose it. There’s no “right way” to host a retreat: the only right way is the one that excites the host and in turn, excites the right attendees. I’m so excited to be able to bring a cruise writing retreat to those who want to do it!Note: if taking a cruise is a “hell no!” for you, I’m so glad you know this about yourself! Knowing that organizing travel logistics is not my passion or strong suit, I’ve outsourced those functions to a dedicated travel coordinator. This way, writers can pick the logistics that work best for them, and I don’t have to do it or get stuck with a bill.There will always be financial risk, but I am comfortable with it. I’ve tried to make the “event fee” (the cost of my coaching) as affordable as I can for the value writers will get. I’m very confident writers will make a lot of progress on their projects before, during, and after the retreat with the planning, accountability, and feedback they get from working with me. I know this going into it: I will break even only if four writers attend. But it’s worth it to me to give this venture a try.Note: the travel deposit and the event fee are refundable up until 120 days prior to sailing, which is the cruise industry standard.I can choose how to structure the retreat. I know I don’t want to teach classes; I want to work one-on-one with writers on their individual projects. Which means I really can’t serve more than eight writers on this retreat. Of course, retreats are more profitable the more you scale, but the tradeoff is the 1:1 coaching, accountability, and feedback daily.I can feel the fear and do it anyway. And so can you.

Amy Goldmacher is a book coach and writer who designed a cruise writing retreat for herself in 2023 and co-taught on the 2024 Craft and Publishing Voyage with Jane Friedman, Allison K Williams, and Dinty W. Moore. Amy loves writing while cruising so much that she is leading a cruise writing retreat September 3–10 from NYC to Southampton on the QM2, for those who want to spend a week dedicated to their writing projects with 1:1 support from a book coach while traveling across the Atlantic in luxury. (Deadline to book is May 1, 2025. Reserve now—cabins are likely to sell out because that’s the nature of cruising!)

February 13, 2025

The Humble Neighborhood Library: Why It Should Be Part of Your Book-Enthusiasm-Generating Plan

“Calabazas Branch Library Grand Opening” by San José Public Library is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 [image error][image error][image error].

Today’s post is by author Kelly Turner.

I’m an easy target for an author talk. Truly, I don’t want to meet you for dinner, but I’ll plan a vacation around a book event. I’ve been to author events at bookstores, universities, and theaters. Until recently I’d never been to one at a neighborhood branch library.

While picking up library book holds last month, I noticed local author Jennifer Mathieu had an event at a branch library in my system to promote The Faculty Lounge, her first novel for adults (after seven young adult titles). I met Mathieu at a writers conference last summer. She was warm and approachable. I’d happily support her book. I was also curious about the venue—neighborhood branch? Not the Central Library downtown? The one with underground parking accessible via a hard right from a one-way street? I was game. I reserved my spot online.

When I arrived to the community room at the Dr. Shannon Walker branch at 2 p.m. on a dreary Saturday, nearly all 60 chairs were full. Houston independent bookstore Brazos Books had a sales table at the back. I took a spot on the second row. What followed was the best author event I’ve ever attended.

According to the Panorama Project’s 2019 survey of nearly 200 libraries in 30 states, about half of responding libraries produced ten or more events (including book clubs, speaker series, and author events) each year. Libraries hosting fewer than 10 events per year were more likely to host community book clubs and speaker series than author events. I can’t claim these data are representative of the (over 17,000) public libraries in the US, but given the American Association of Publishers reports nearly $30 billion in US book sales in 2023, there’s capacity for more library events connecting authors and readers.

The way I see it, local library events can help with two problems we face as writers and as people. As writers we’re tasked with a fair amount of psychologizing about our ideal readers: figuring out who they are and where they hang out. As people in 2025, we’re lonely. It’s an epidemic. Partnering with neighborhood libraries can help with both.

I don’t want to undercut independent bookstores, essential players in the book ecosystem. According to Jane’s article on public libraries boosting discoverability, while no formal study has been done, there’s reason to believe library events boost sales in area bookstores. (Libraries also buy the books they lend us.) I’m not suggesting library events instead of bookstore events, I’m pitching both/and.

First, your ideal reader might hang out in a neighborhood library. Most readers don’t have an independent bookstore in their neighborhood. For those that live near a library (or are voracious physical book readers), we might stop by our library by as frequently as we visit the grocery store. Libraries are low barrier-to-entry third spaces full of books waiting for us to borrow, read, fall in love with, and tell a friend about.

Second, about the loneliness. While Mathieu’s event was live streamed, the magic was in sixty people—sixty of Mathieu’s ideal readers, I would argue—showing up to the same IRL place at the same time. Mathieu began several answers in the Q&A by introducing the person asking the question—“Thanks for the question, Barb. Everybody, Barb’s my neighbor.” My impression was that at least a third of the audience was an acquaintance of Mathieu’s at some level or connected strongly to an element of her book (Mathieu’s a veteran high school English teacher).

Don’t mistake a casual, friendly audience with a polite, passive one. In addition to the event being well-attended, the audience was engaged. People had substantive, thoughtful questions.

Consistent with the Panorama report, many libraries offer author talks on the regular, but not the Dr. Shannon Walker branch. This was their first author event. Closing the event, the branch manager shared that a library staff member convinced her to bring in Mathieu after hearing her at a bookstore event. She went for it! They made print and digital marketing materials, expanded their community room to the max, filled the space and brought in Brazos Books to move units. Ninety percent of respondents to Panorama’s survey reported that book sales were a part of book events at their library. One participant elaborated that the area bookstore likes partnering with the library because it has higher seating capacity (200 versus 30 seats)—and employee staff time to manage events—than the local bookstore. The branch manager reminded us that libraries are here to serve our needs. As writers and as people, we need each other. Why not meet at the library?

And there’s no rule saying you can’t try other people’s neighborhood libraries. In Jane’s previous piece, author Nancy Christie mentions in the comments that doing exactly this drives sales in places she’s not well known. Jane’s piece includes a three-item list on what to prepare before approaching a library and information on getting self-published work into their catalogues. According to the Panorama report, 95% of responding libraries booked events with the author directly. In other words, it’s on us.

After the event, people lined up to get their books signed. What else happened was that people talked to each other. One woman asked me if she knew me from line dancing class. She didn’t, but I’ve always wanted to try it. I got the info and attended the class last night.

The woman behind me in the signing line was another neighbor of Mathieu’s, visiting the branch for the first time after a long stint as a family caregiver. Would she have driven to a bookstore 20 minutes away for the event? Maybe. But she didn’t have to. Afterward, she signed up for a library card.

As writers, as readers, and as engaged citizens, let’s not forget those ideal readers who cart home stacks of books each week and might be hungry for connection with their neighbors. Check in with your neighborhood library—what can you create to celebrate your book, someone else’s, or both?

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1885 followers