Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 25

February 12, 2025

New agent at Jane Rotrosen agency

Danielle Marshall was formerly editorial director at Lake Union Publishing (Amazon), among other roles in traditional publishing and bookselling.

This premium article is available to paid subscribers of Jane's newsletter. Access will be available later this month. You can sign up to be notified when subscriptions open.

New literary publishing event for Southern writers, publishers, and others

The Deep South Convening on the Future Success of American Writers will take place on May 24 at the University of Alabama in Birmingham.

This premium article is available to paid subscribers of Jane's newsletter. Access will be available later this month. You can sign up to be notified when subscriptions open.

Links of Interest: February 12, 2025

The latest in traditional publishing, bookselling, the children's market, audio, book marketing, AI, and culture & politics.

This premium article is available to paid subscribers of Jane's newsletter. Access will be available later this month. You can sign up to be notified when subscriptions open.

Expect the Creative Process to Be Uneven and Messy

Photo by Mark F. Griffin

Photo by Mark F. GriffinToday’s post is by writer and creativity coach Anne Carley (@amcarley.bsky.social) who believes #becomingunstuck is an ongoing process. This is the sixth and final post in the series.

There will be little rubs and disappointments everywhere, and we are all apt to expect too much; but then, if one scheme of happiness fails, human nature turns to another; if the first calculation is wrong, we make a second better: we find comfort somewhere.

—Jane Austen, Mansfield Park

In Austen’s novel, Mrs. Grant is explaining to her new, unmarried friend Mary Crawford the positive growth that can happen after a marriage, even to a relative stranger. I like to adapt Austen’s words to the creative life because Mrs. Grant’s message transfers well.

Rubs and disappointmentsAs makers of things that didn’t exist before, we’re each going to deal with “little rubs and disappointments,” high expectations, and dashed hopes. Our human nature is built to turn to another scheme of happiness after one scheme fails. Just like those early GPS units, when surprised by a turn we made, would bleat “recalculating” until they caught up, we’re capable of pausing, adjusting our plan, and reframing our narrative. It’s all part of the deal.

I’m stuck a lot. I imagine many of us are. Point is, that’s not really negotiable. Stuckness is as stuckness does. My stuckness today might look unattainably wonderful to the me years ago who was too crazed a workaholic to make time for regular creative pursuits, instead setting aside long holiday weekends for songwriting binges. Nowadays, a state of fluid creativity happens more often. The rest of the time, it’s reasonable to expect stops and starts. Rubs and disappointments, along with smooth, serendipitous states of flow.

On a bad day, getting stuck can feel like it’s all rubs and disappointments with no meaningful creativity to balance things out. It’s a lousy feeling. The temptation can be strong to attack the stuckness. I suggest another approach.

Bookshop • AmazonFinesse resistance

Bookshop • AmazonFinesse resistanceGoing after the stuckness head on, like an action hero going after the villain, might feel sweepingly cinematic. But a shift in focus, or indirection, or intentional distraction might be wiser than attacking your resistance. Resistance isn’t an enemy to be vanquished. It’s part of a creative life, but doesn’t need to dominate. Normalize resistance as another feature of your everyday experience, and you’ve already loosened its grip. Shift your focus to something mundane that you can do right now, and resistance will start fading, as though you moved the Transparency slider in a graphics app closer to zero.

Relax and rememberInstead of stressing out whenever we encounter stuckness, resistance, and “rubs and disappointments,” we can relax and remember that the creative process is messy and uneven. The meaning we make comes from the work we put in, day after day, year after year. This is the good news. Summing up this series of posts for Jane, I offer the following nuggets for your attention.

Even when an observer might call it lazy, laissez-faire can be your best friend. Trusting the process means accepting that we can’t predict the future, nor can we expect every new element of our work to fit neatly, just clicking into place with what has come before.Keep at it, when everything lights up as well as when it doesn’t. Those golden moments come around again, especially when we routinely persist during their absence.Rewrite/revise with clarity, adjusting your focus as needed. Think of the optometrist’s device, and click away until the sentence or paragraph is sharp.Determine whose voice is on repeat in your head with the discouragement, belittlement, or bullying—and stop listening whenever it isn’t yours.Unclutter your stuff, relationships, and words to clear the way for your own creative flow. Protecting your creative energy this way is surprisingly powerful.Get out of the silo and open your mind to other people’s ideas, responses, and behavior. Doing this will also keep you from isolating and losing your sense of connection to other creative people, while providing them with the support, friendship, and a sense of belonging that all primates require.Sustain your creative process by staying true to yourself. Competition, anger, complaining, and obsessing about the marketplace may not be good focuses for your attention. Consider paying more attention to your creative needs in the moment, instead.In the words of RuPaul, “Fulfillment isn’t found over the rainbow—it’s found in the here and now. Today I define success by the fluidity with which I transcend emotional landmines and choose joy and gratitude instead.”

February 11, 2025

The Perfect Guide for Where to Submit Your Writing (Does Not Exist)

Photo by GeoJango Maps on Unsplash

Photo by GeoJango Maps on UnsplashToday’s post is by Dennis James Sweeney, author of the new book How to Submit.

As writers, we often long for the perfect guide to where we should submit our writing. We want a resource that is dependable, consistent, and navigable. The publishing landscape is complicated! Especially when we are first starting out, we need someone to distill that publishing landscape for us.

But it can be difficult to find a resource that will give you everything you need. Some resources provide a ranking system, organizing publication venues into an ordered list. Others use tags and categories to enable the use of search criteria. When submitting, the closest we can get to “perfect” is assembling a personal combination of these lists, depending on our own publication goals.

Available submission resourcesRanked lists are the most clearly organized submission resource, in that they tell us which venues are most advantageous to publish in if our goal is to achieve prestige for our writing. These kinds of lists are mostly used for literary magazines. They typically base their rankings on the number of awards given to pieces published in each journal:

Clifford Garstang reliably assembles a ranking of the literary magazines most often awarded Pushcart Prizes. He has separate lists for fiction, nonfiction, and poetry.Erika Krouse divides the top 500 literary magazines for fiction into tiers based on prizes, circulation, payment to writers, and “coolness.” Her list also includes information about deadlines, response time, and word count.Most recently, Brecht de Poortere ranks literary magazines based on the relative weight of several prize anthologies. His extensive spreadsheet includes details like reading period, cost to submit, and whether or not it is a print magazine.If you are submitting a full book without an agent, you will likely be looking for small, independent publishers. There isn’t a specific resource that ranks these presses. But browsing the winners and finalists for prizes like the CLMP Firecracker Awards, Lambda Literary Awards, and regional book awards (such as the Mass Book Awards) can give you an idea of the small presses that receive the most public attention. Additionally, book reviews give you an idea of which publishers’ books are being read and considered publicly. Review venues for small press writing include Full Stop, Rain Taxi, and The Rumpus.

If you’re in search of robust lists that don’t rely on a ranking system, there are also plenty of places to turn, not only for literary magazines but also for small presses and literary agents. These resources leave the work of “ranking” publication venues up to you, but they have the benefit of being highly organized based on a number of criteria:

Duotrope (which costs $5 per month) is the most longstanding, comprehensive database for both literary magazines and small presses. It includes a submission tracker, if you prefer to use an external resource instead of your own personal system.Chill Subs, which sprang up in 2022, is like a free, Gen Z Duotrope (although some features have recently been monetized).For the analog among us, Writer’s Market is the print edition of every detail about nearly every submission venue. Additionally, both Poets & Writers and the CLMP maintain extensive lists of literary magazines and small presses that are open for submissions.If you have written a book you want to publish with a Big Five house, you will likely be searching for agents to query rather than looking directly for publishers. Jane Friedman’s post on finding a literary agent is a terrific primer on who needs an agent, how to query an agent, and how to choose the agent who is right for you. In addition, there are several lists and databases that will help you narrow down your search:

Publisher’s Marketplace ($25/month) is the gold standard. While it isn’t exactly a submission resource, it provides a detailed, updated account of all agented book deals in the United States. You can organize these deals by agent, genre, and keyword.Manuscript Wishlist has a searchable database of literary agents accepting submissions, sometimes including a personalized wish list that goes beyond the details included on Publisher’s Marketplace.QueryTracker includes notes from users on recent responses to their queries. Writer’s Market , Duotrope, and Poets & Writers include lists of literary agents alongside their information about literary magazines and independent publishers.These submission resources play an important role in guiding writers toward the right home for our writing. Especially when you combine the insights of several lists, it’s possible to end up with a solid understanding of the landscape of literary magazines, small presses, and/or literary agents.

The limitations of submission resourcesBut still, here’s the thing: Not a single one of these resources is going to tell you exactly where you should submit your writing.

The ranked lists hint at which publications might mean look the “best” to some potential reader in the future. The unranked lists, for their part, give you the capacity to search for the criteria that match your writing.

But can they tell you who each literary magazine, publisher, and agent really is? Can they give you a sense of the character of each submission venue? Can they tell you whether this publishing experience will meet your goals?

That’s one thing these submission resources can’t do: They can’t tell you whether your writing is a fit. No matter how much information you have access to, a database can’t substitute for knowledge of the publication itself.

This problem reminds me of Borges’s very short story, “On Exactitude in Science,” which explores the difficult truth that only a map the size of the territory itself can be truly accurate. The same is true for submission resources. While these lists and databases help guide us toward venues that might resonate with us, it is difficult to fully understand where you are submitting until you go directly to the publications that are being described.

Navigating to their website and poking around is, of course, the first step in this process. But the best way to achieve familiarity with the venues where you are submitting, in my view, is to participate in the publishing landscape. The only “perfect” submission resource is simply getting involved.

Getting involved with literary publications doesn’t have to mean a major output of time. Instead, there are many small routes you can take to a greater familiarity with the venues where you want to send your work.

The perfect submission resource: getting involvedThe easiest way to become familiar with the literary landscape where you’ll submit your writing is being a reader. Read online literary magazines, subscribe to print literary magazines, and read books from a diversity of presses. Set a goal, for example, of reading one new magazine or small press book each season. Look up the agents of books that you appreciate, and read more books they have worked on. Over time, you’ll build up a familiarity with the publication circumstances of the writing that speaks to you.

Attending events is another low-commitment way to get involved and meet others in the literary scene. Many reading series have now migrated to Zoom, so you can attend online or in your local area. Readings hosted by literary magazines or presses, especially, can give you a deep sense of their personality.

You can also get involved in a more active way by contributing your time to a publication or helping to build the conversation around others’ writing. There are several ways to do this:

Write book reviews. Even if you’re inexperienced, writers and publishers always appreciate a thoughtful consideration of their books, and literary magazines are often eager to publish reviews.Conduct interviews with published writers. Literary magazines often publish interviews with authors as well. Taking the initiative to conduct one allows you to get your foot in the door while being in touch with a writer whose work you appreciate.Volunteer as a reader for a literary magazine. Many literary magazines need initial readers of submissions to help them narrow down their queue.Start or help out with a reading series. Writers always need somewhere to present their writing when they come to town. Creating the space for live events puts you in touch with both writers and publishers of just-released books.Follow and engage on social media. As stressful as social media is, it can also be a source of connection and warmth, where you can build a personal relationship with publications’ and agents’ work in real time.Participate in writing groups, workshops, and classes. Getting together with other writers on a regular basis will help you build community and share knowledge, even if it’s not directly related with the publishing world.Just remember: participating in the literary world isn’t a quid pro quo. It won’t feel great—to you or to anyone else—if you get involved so that you can get published. Instead, you’re investing in a community you want to be a part of. As I see it, the entire goal of submitting and publishing our writing is to get involved in a collective literary life. You might as well start now.

To me, the beauty of the publishing landscape is that there is no perfect submission resource. You simply can’t contain the diversity, idiosyncrasy, and varying publishing practices of all the places where we can submit our writing.

This leaves some level of the unmappable in our submission practice, no matter how familiar we become with the publishing world. But it also mirrors the entire experience of being a writer: we dive into the unknown with spirit, with hope, and emerge on the other side knowing a little better who we are.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out How to Submit by Dennis James Sweeney.

February 6, 2025

6 Tips on Writing Disabled Characters

Photo by Marcus Aurelius

Photo by Marcus AureliusToday’s post by James Irwin grew out of a course on disability representation in media and literature he teaches in the disability studies program at Wm. Paterson University.

Good writers create characters that reflect the diversity of our world. Unfortunately, disabled characters in the work of abled writers tends to fall short of the ideal. Most people with a disability rarely see themselves in stories, and when they do the representations can be inaccurate, with some offensively ableist. Too often, writers become lazy and rely on disability stereotypes and tropes, turning these characters into not much more than scenic décor and plot devices. As abled writers, how can we do a better job?

1. Include characters with disabilities in the first place.The widely accepted definition of a disability is any condition of the body or mind that makes it more difficult for the person with the condition to do certain activities and interact with the world around them. That covers a lot of ground, from the mental to the physical, from the internal to the external, from the obvious to the hidden. So, it should come as no surprise that over a quarter of Americans reportedly live with a disability of some type.

Yet the disabled are 34 times more likely than the abled to report they’re not adequately represented. There currently is no data on disabled characters in adult literature, but we know what’s happening in mass media. In the top 100 films of 2022, only 1.9% of characters with speaking roles were shown as having a disability. Only 0.6% of speaking characters were disabled women, and 0.47% were disabled people of color. If you are a black woman with a disability, you are very nearly absent from feature films.

2. Don’t make disability the defining feature.When you write a disabled character, they should not be defined by their condition. They should have their own lives, their own accomplishments, their own complex personalities. The condition doesn’t need to be a matter of concern or comment at all. For example, I’m currently finishing a novel in which a main character has undiagnosed autism. He isn’t aware of it, nor is anyone else, and no one comments that he might be autistic. His condition is just part of who he is. But I know about it, and that knowledge helps me create a character who is consistent in how he conducts himself, reacts to situations, and interacts with others, all of which are a little different than what a non-autistic character would do.

3. Avoid stereotypes and tropes.It is distressing how the same old cliches are applied to disabled characters. Most fall into one of the “big four” of disability tropes: the “magical” disabled, the “evil” disabled, the “inspirational” disabled, and the “redemptive” disabled. Here’s how to identify these stereotypes.

MagicalMagical disabled characters transcend their limitations through nearly super-human abilities, typically to help the lead character. They are usually defined by their disability and their compensating skill, and they rarely have an arc because they are already as developed as they will ever be. Think of the math savant Raymond Babbitt in Rain Man, the quadriplegic criminalist Lincoln Rhyme in The Bone Collector, the Pinball Wizard in Tommy, or any of a horde of blind martial arts masters. Marvel superheroes are often examples, from Charles Xavier’s wheelchair to Echo’s deafness to Moon Knight’s dissociative identity disorder.

EvilIn evil disabled characters the disability causes the villainy (“I’ll get even with the people who did this to me!”) or serves as the physical manifestation of a twisted soul. Think of Captain Ahab in Moby Dick, Darth Vader in Star Wars, or, more subtly, Mr. Potter in It’s Wonderful Life. Look at Richard III: in real life he had one shoulder a little higher than the other but was otherwise a normal man; a hundred years after his death Shakespeare gave him a hunchback, a limp, and a withered arm to shape his wickedness. James Bond villains are a parade of the evil disabled, mostly facial disfigurement.

InspirationalThe inspirational disabled “go beyond” their disability and accomplish marvelous things through pluck and hard work and a good attitude, thus finding some acceptance by the abled community. This is based largely on the notion that a disability is not merely a difference, but a tragic challenge that needs to be overcome. A version is known as “inspiration porn,” a phrase coined by the late Australian activist Stella Young to describe feel-good stories about children running with artificial limbs or a boy with Down syndrome allowed to suit up for the last play of a high school basketball game. This is top-level cringe in the disability community.

RedemptiveThe redemptive disabled exist mostly as a prop, sometimes sacrificing themselves in some manner to prove their worth or give meaning to their life, usually to help the lead character reach their goals. Think Tiny Tim in A Christmas Carol or Quasimodo in Notre-Dame de Paris, or Auggie Pullman in the middle grade novel Wonder. A notorious example is the wealthy young quadriplegic Will Traynor in Me Before You; abled people may read it as a romance, while the disabled read it as confirmation that their life has no value (unless they’re rich enough to bequeath a lot of money to someone), so suicide is a reasonable conclusion.

4. Look to your own experiences.Part of the trouble is that abled writers see the disabled as other, and therefore apply a distanced version of empathy. That is why so many stories ostensibly about a disabled character are actually about the impact those characters have on abled people around them.

But abled writers might be missing how much overlap exists. For example, I have an artificial knee, and for the few years before replacement I had difficulty doing certain activities and interacting with the world around me. In other words, during that time, according to accepted definitions, I absolutely was disabled. However, not once did I say that about myself, in large part because “disabled” is often viewed as a negative label. Nevertheless, I know what it is like to resent the lack of accessibility features in buildings and the condescension from strangers, particularly the passive/aggressive offers of help. Most of us have at some time in our lives experienced a form of impairment that we can use to mine deeper levels of understanding for our characters, even if we never officially thought of ourselves as disabled. Forget the label, tap the experience.

5. Learn from the disabled.The most effective antidote to the harm caused by those stereotypes and tropes is to read what writers with disabilities have to say about their condition and experiences, because a lot of it may surprise you. Remember, there are many forms of disability and a writer with one can’t speak for all of them, so look for books and articles by writers with the conditions relevant to your characters.

For example, my writing of that autistic character owes much to the insights of the academic, inventor, and ethologist Temple Grandin, who documented in multiple books what she gained through her autism. She points out that focusing so intensely and automatically on the deficits causes people to lose sight of the benefits and strengths of the autistic mind.

A good source of perspective on physical disabilities is the DeafBlind speculative fiction writer Elsa Sjunneson. She is a fierce opponent of being marginalized by society, as she makes clear in her book Being Seen: One DeafBlind Woman’s Fight to End Ableism. She lives her life as a rebuke to those would push the disabled into hiding, through both her activities (she is an avid hiker and fencer), and her bold personality. (“People assume I’m going to be quiet and I am loud. I am snarky, I’m sarcastic. I talk a lot.”)

A view on “Invisible” disability can be found in Alyssa Graybeal’s Floppy: Tales of a Genetic Freak of Nature at the End of the World. She writes of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome as both a significant condition as well as essentially unnoticed by others. “It can be lonely and infuriating to be invalidated for ‘not looking sick,’” she says. “However, invisibility sometimes protects me from others’ insidious assumptions…or being treated as if my illness were the only noteworthy thing about me.”

Remember, there is no homogenous disability community. It comprises individuals, with a variety of conditions having a wide range of impacts on their lives. They have their own specific attitudes and relationships with their situations.

6. Apply the Fries Test.Created by the memoirist and poet Kenny Fries in 2017, it was inspired by the Bechdel Test (which measures representation of women in fiction). It asks three questions of a manuscript:

Does the work have more than one disabled character?Do the disabled characters have their own narrative purpose other than the education and profit of a non-disabled character?Is the character’s disability not eradicated either by curing or killing?A lot of work will “fail” the Fries test, but the most important thing about it is the process of applying it. By raising the issues in their minds, and assessing their work from that vantage point, abled writers can educate themselves and build greater understanding and empathy.

Writing characters with disabilities doesn’t have to be complicated or difficult. Doing it better only requires being thoughtful, and putting in a little work to understand what things look like from the character’s position. “I hope people realize they don’t need a degree in disability studies,” says Elsa Sjunneson. “They don’t need to be disabled. They just need to be willing to listen.”

Data sources include the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, World Health Organization, Pew Research Center, Disability Studies Quarterly, Nielsen, USC Annenberg.

February 5, 2025

Free Yourself from Rewriting Paralysis

Photo by Anna Shvets

Photo by Anna ShvetsToday’s post, the fifth in a series, is by writer and creativity coach Anne Carley (@amcarley.bsky.social), author of FLOAT • Becoming Unstuck for Writers, now in its second edition.

Most of us accept the basic reality: We draft and then we rewrite. Edit, take a break (when time permits), revisit, and revise again. Sometimes, though, the revision process meanders off-course, leaving us—and our project—stranded.

Returning to our initial vision, applying reason, and using an outline are certainly useful tools. And yet. Sometimes they are not enough. A deadline focuses the mind, for sure. Walking away is a time-honored method for regaining a fresh view. And yet. For a host of reasons, many of us find ourselves needing to resolve an unfinished piece, and feeling uncomfortably stymied.

Zoom outBecoming unstuck from this kind of paralysis can happen. One way to get out of the weeds is to pull the focus higher, to gain a broader view. Remembering the bigger picture can completely reset the way we look at the project, allowing us to resume work with fresh energy.

Accept some inevitable chaosAnother is to accept the erratic nature of the creative process, which is rarely linear or swift. Sometimes I don’t even know when a piece has started, let alone where its midpoint or end will turn out to be. A random hasty jot in a notebook can become something bigger, later. An old, discarded chunk in the file of a draft that went another direction can come to life by accident when I’m digging around in the compost files for something else.

Just do somethingIt can be smart to pick an arbitrary beginning point, just to start writing again somewhere, anywhere. Later, those words can be excised as throat-clearing that has outlived its usefulness, or moved elsewhere in the piece, or out to the compost heap.

Revision and optometryI like the grace that George Saunders confers on the discomfort of rewriting: “An artist works outside the realm of strict logic. Simply knowing one’s intention and then executing it does not make good art.” He continues with a useful metaphor:

The artist…is like the optometrist, always asking: Is it better like this? Or like this?…As text is revised, it becomes more specific and embodied in the particular. It becomes more sane. It becomes less hyperbolic, sentimental, and misleading.

With each click of the imaginary phoropter (I learned a new word), Saunders is testing, word by word, line by line, trusting himself to recognize each incremental improvement, and repeating that process until the piece is good enough.

Challenge blind loyalty Bookshop • Amazon

Bookshop • AmazonFor me, too much loyalty to my vision, pre-drafting, can interfere with the writing process. For example, this piece began as a post about scope creep. Once I started composing these sentences, though, it turned out to be about rewriting. A novel I’m working on began with one protagonist and her point of view. Then it changed to two of each. It’s now evolved to feature one protagonist whose experiences are interpreted by two additional POV characters.

The persistent rewriting process—sometimes with the added shake-up of getting out of the silo—makes those changes possible.

Just as Saunders suggests, it’s a process. You edit a sentence. Your inner optometrist clicks the dials. The lenses change, bit by bit, sentence by sentence, until things look—and feel—a little sharper, a little better. (I recommend his Saunders’ Office Hours Substack and Story Club, by subscription.)

February 4, 2025

Scene and Structure: The Wave Technique

Photo by Matt Paul Catalano on Unsplash

Photo by Matt Paul Catalano on UnsplashToday’s post is by regular contributor Susan DeFreitas, an award-winning author, editor, and book coach. On Wednesday, Feb. 12, she’s offering a free masterclass for fiction writers: Mastering the Art of Scene.

Often writers of fiction get no instruction whatsoever on how to construct a scene.

And personally, I think that’s ridiculous, because scenes are the places where we as readers most feel like we’re living the story. What would the Harry Potter books be without all that dialogue? What would The Hunger Games be like if Suzanne Collins had relied on summary rather than scene?

Boring, is what they’d be—even though they tell great stories.

But there’s more to it than just having your beloved imaginary people talk to each other on the page, in specific settings, with a little conflict thrown in for good measure.

In fact, there is one technique that will absolutely transform every scene you write, and make those scenes a lot more satisfying from the reader’s POV. Consistently using this technique will also have the effect of making your reader want to read on, because scenes like this feel surprising and dramatic.

That technique? Building toward a breaking point, then revealing something new about the characters, their world, or the plot.

Here’s how this wave structure breaks down.

1. The setupWhat’s important for your reader to know in the scene to come?

I’m talking backstory, background info, world building, gossip about the other characters, whatever it is your reader needs to know in order to understand what’s about to go down in the scene to come. Whatever it is that would add richness, nuance, and depth to their understanding of the scene to come, find a way to work it into the narrative just before the POV character heads into the scene.

2. Scene beginsIf you’re coming into scene from summary (“All week, Lizzie had been thinking about the callous way Erin had dumped Fritz”), make sure you transition clearly into scene (“And then, as she walked into the break room that day in search of her afternoon caffeine, there he was, frothing himself a cappuccino.”)

From there, make sure you establish the basics: What does this room look like? What’s the vibe? Who else is in the room? (Definitely don’t spring a new character on us halfway through the scene who was supposed to have just been lurking by the watercooler or something—unless that character is supposed to be concealing themselves on purpose.)

And what do the other characters/character involved in this scene look like?

Include dialogue or activity that makes it clear what the characters are doing here in this setting, thereby setting the scene.

3. The buildWithout a lot of small talk or throat clearing, the main characters here should make it clear, based on what they’re saying and how they’re acting, what their agenda is in this situation.

If we go with the scenario suggested by my parentheticals above, maybe the POV character, Lizzie, really wants to let Fritz know that the way Erin dumped him was just terrible, and she’s sorry he’s had to go through all that (and maybe that Lizzie isn’t a big fan of Erin, BTW).

Here’s the point where many writers back down or back away. The Fritz character maybe acts a little furtive, and Lizzie doesn’t know why, so there’s a little tension there, but on the whole, things stay nice and surface level and polite.

Which is (you guessed it) boring!

These are cases where I encourage my clients (especially my conflict-averse clients) to push out the conflict—in this case, that might mean having Lizzie press the matter with Fritz, maybe even corner him by the espresso machine, even as it’s obvious to the reader that Fritz really doesn’t want to be having this conversation.

That’s a key part of this technique: Pushing the conflict to the point where something actually changes.

4. The break and the revealFinally, poor Fritz can’t take it anymore: He stops trying to get away from Lizzie, and, exasperated, he confesses that Erin didn’t dump him, he dumped HER.

Scenes that reach this point will strike your reader as powerful and well-crafted. But if it works for your particular scene and your particular story, you can take it one step further for even more dramatic effect (and even more narrative momentum).

5. The double revealFritz reveals that he has, in fact, always had a thing for Lizzie. (And then, you know, maybe Erin comes in to find them snogging by the nondairy creamers.)

Many storytelling authorities (screenwriter Robert McKee among them) will tell you that the measure of whether a scene works or not is whether something has changed by the end of it.

What I’ve outlined above is not only a great way to achieve this, but to achieve that sense of change in a convincing way (by pushing out the conflict first).

By giving us the background info (the setup) before the scene, you give us a sense for what is either common knowledge in the world of the story or known to the POV character about the situation they’re headed into—and you remind us how they feel about it.

By establishing the setting of the scene and its characters in a clear way at the outset, you give us everything we need to fully visualize the scene, and to feel like we’re there ourselves with the characters as these various sources of conflict and tension bubble up.

By giving us the build (and staying with it long enough to create a sense that the conflict or tension has reached the point where “something has got to give”), you create a sense that the breaking point to come is not only fully convincing, but inevitable.

And by working in your reveal (or double reveal) at the breaking point, you deliver important story information in the most vivid and memorable way: via scene.

Even if you don’t adopt this structure for absolutely every scene you write, I’d encourage you to try it for any big revelation in your novel: a plot twist, a new story element, the news that a trusted ally has gone over to the other side, etc.

Now I’d love to hear from you. Have you heard of this sort of structure for scenes? Do you use it in yours? (And if not, what is the most useful technique you’ve found for creating vivid and memorable scenes?)

Note from Jane: On Wednesday, Feb. 12, Susan is offering a free masterclass for fiction writers: Mastering the Art of Scene.

January 30, 2025

Turn Your Short Pieces Into a Finished Nonfiction Book

Photo by Giulia May on Unsplash

Photo by Giulia May on UnsplashToday’s post is by author Lara Lillibridge.

Have you amassed a heap of assorted essays, flash pieces, chapters, ideas, and you think you have enough to turn it into a book? Does it seem scattered and overwhelming and you’re not sure what will fit where and it is all rather daunting?

Never fear—here is a step-by-step guide to turn your hot mess into a hot dish.

1. Ask yourself, “What is my book about?”Come up with an organizing question or statement. Every collection has a theme or arc beyond “These are the best things I’ve written so they should be a book.” Sadly, that’s a hard book to sell.

This process is similar to the old Twitter pitchfests where we had to describe our books in one tweet, back when there were character limits.

Here are examples from my own work:

Which was more formative: Having a lesbian parent, or a bipolar one?What do you owe an abusive/negligent father, now that he is old and lonely?My journey out of divorce, through six years of single parenting, and into the family blender with my new partner.The benefit of this exercise is that you can pull out this line at every future coffee hour or cocktail party when people ask what your book is about, as well as use it to start your query letter.

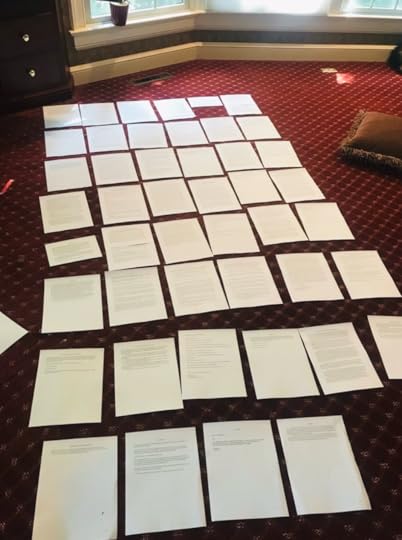

2. Sort out what you have written.What are your major themes?What ages or time periods are you writing about?Do you have a bunch of chapters that are different lengths, styles, or points of view?3. Make a list of every chapter or essay—or print out the entire project.Assign a color for each category you chose in step 2. For example, highlight all the life stages by color, or use different colors for different lengths.

Here’s an example from one of my early drafts:

And the same book, only with sticky notes:

By looking at the project by color, I was easily able to see that I didn’t have enough blue (religion) or purple (childhood) notes. I could also see that I had way too much going on. I chose to eliminate those categories from this project and save them for a future book.

4. Or, make a spreadsheet.On the left, list all your chapters. Across the top, list all the themes or categories you have. Put an X in the box that each essay fits into.

5. Look at your project critically.

5. Look at your project critically.Step back and take a look. Do you have a preponderance of one color? Is your spreadsheet weighted heavily in a few categories? Do you have any outliers that are lone wolves?

6. Seriously consider each theme.Where do you need to strengthen or write more? Can you take essays that fit into multiple categories and shape them to be stronger in one area or another?

If you are sorting by length, what is the rhythm of the collection? Do you have too many fragments in a row?

You can recolor your list as you look at these different topics. I like to save a new document, remove the highlights, and start over.

Here is another one of my projects, sorted by length:

I could easily see where I had too many flash pieces in a row.

7. Consider the emotional weight, particularly if you are writing about trauma.I like to go through my list and rate each chapter based on the emotional intensity. Where will the reader get a breath of air?

Take a memoir or essay collection you love, and go through and assign an emotional weight to each chapter. This is just your opinion—you won’t be graded on it! Different people are affected by different things, so someone else may have a different numbering system. There are no wrong answers. What is the darkest/hardest chapter? How does the author create moments of light for the reader?

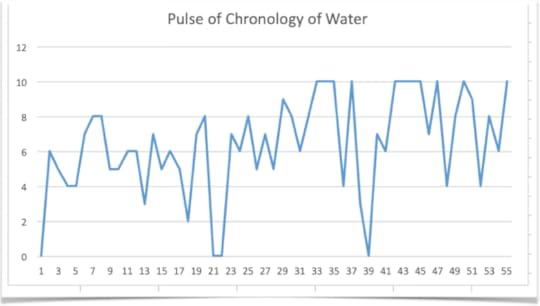

I did this with The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch. I graphed the results and came up with this:

It reminds me of swimming the breast stroke—after we go under into despair, we rise up to lighter moments. This keeps the reader coming back—it delves into heavy material but doesn’t overwhelm the reader to the point where they close the book and walk away.

8. Look at the time jumps.Is there a flow or rhythm to the movement through time? Are you signaling the reader clearly when we flash back or forward?

9. What about repetition?As the same theme comes up, are you expanding, narrowing on the theme so it is adding something new to the project? Or going over the same ground?

10. Consider arc.Is your project moving to a place of change? Consider the arc of each theme. For example, my book, Mama, Mama, Only Mama, is a collection of essays, blogs, and recipes depicting my journey through single parenting.

Here are my thematic arcs:

Recipe for microwaving a frozen dinner to cooking a turkey and touching the carcassRaising kids from diapers to riding bike to school aloneMy relationship with my ex-husband from my walking out the door to wanting to send him a Father’s Day card11. Look at chapter flow.For this I like to print out my chapters and lay them on the floor. Read every last line and see how it connects to the first line of the following chapter.

12. Ask the hard questions!Is your current structure serving you well?Would a different structure strengthen your manuscript?Do you have enough material for each theme?Do these essays really hang together? Or should some be split off into a different project?13. Visualize the flow by doodling.

12. Ask the hard questions!Is your current structure serving you well?Would a different structure strengthen your manuscript?Do you have enough material for each theme?Do these essays really hang together? Or should some be split off into a different project?13. Visualize the flow by doodling.If you are a more visual person, a fun way I learned to play around with ordering segments is from Rebecca Fish Ewan in her book Doodling for Writers. Take a stack of index cards, and draw a simple doodle representing what happens in each essay or chapter. A doodle can form an instant connection, as opposed to reading descriptive summaries over and over. Now lay out your doodles on the table and look at the flow. Move them around until the order pleases you.

Here is a segmented essay I was working on:

14. Congratulate yourself!

14. Congratulate yourself!Once you have concluded that you have the best arrangement for your collection, congratulate yourself! Have an ice cream, a fancy coffee, or an umbrella drink, then find a beta reader or critique partner and get their opinion.

January 29, 2025

It’s Time to Interview Your Own Inner Diminisher

Photo by George Becker

Photo by George BeckerToday’s post is by writer and creativity coach Anne Carley (@amcarley.bsky.social) who is a fan of #becomingunstuck.

Do you feel stuck because you’re convinced that you’re just shoving words around, not really being creative?

Do you often notice harsh commentary in the background when you draft and/or review your words?

Does a voice inside natter or spew or snipe at you?

If taking a break, drinking water, slicing vegetables, or other simple fixes aren’t freeing you from the influence of that voice, consider addressing the judgy elephant in the room.

Whose voice is telling you that you’re not creative?

What is and isn’t creativeMy friend, Jan, spoke calmly. “I wasn’t being creative. I was just picking up words and phrases and changing them around.”

I said, “That’s what being creative is.”

Jan was visibly startled and asked, “How can you say that? I’m shocked that you’d think that.”

As we kept talking, Jan explained their belief that “creativity” is limited to the supreme artistry of the handful of people at the pinnacles of excellent work—the people who do it effortlessly, who lived on a different plane from the rest of us. Jan learned this in childhood, and has always lived with that narrow view. Creativity belonged only to world-famous artists, performers, writers, and inventors—not regular people. And those supernovas didn’t have to work for it, either.

I encouraged Jan to pause and appreciate their problem-solving skills. Pause and appreciate that they can make something from nothing. Pause and appreciate the beneficial impact their words have on others.

“Normal” creativityConsider your own inner diminisher. Jan’s told them they had nothing creative to offer because Jan wasn’t Michelangelo or Toni Morrison or J.S. Bach. Who do you compare yourself to? Whose stellar achievements make yours look shabby and small? What does “normal” creativity look like to you? Like Jan, do you get smacked down by these messages so routinely that you consider it a cost of doing business—just part of an often miserable writing process?

Who taught you that your talents as a writer are limited or nonexistent? Who suggested that you’re not creative enough? Is that person worth listening to? Does that person deserve to hold power over you?

If any of this sounds familiar, you may want to conduct an interview with the source(s) of that negative commentary.

Whose voice is it?Sometimes writers know at once who’s speaking in these unhelpful, critical ways. It’s often a close relative or teacher from the past. With other writers, the voice is a composite of fears and hidden desires. Sometimes it’s the “mean girls” and their ilk, from the writer’s middle school or adolescent years.

My father taught voice and directed choral groups. When he chatted with an adult who announced an inability to sing—and usually declared, “I can’t carry a tune in a bucket”—my dad asked this:

“Who taught you that?”

Invariably, he explained, every person had an answer. They recalled the exact details: the name, role (teacher, choir director, relative), and time in childhood when this determination was made.

Bookshop • Amazon

Bookshop • AmazonTake the time you need to recognize the source or sources of the unhelpful voice(s) inside you. Then interview yourself. Is this commentary to be trusted? Whose is it? Is it your voice, or someone else’s? Like Jan, did someone instill such high standards in you that nothing you ever do will measure up? Like my dad’s singers, did someone crush your creative dreams when you were young? Do you still hear those judgmental opinions inside your head, as though they are your own?

Gaining a little distance, separating you from the pesky unhelpful voice, can be an important step toward creative confidence and autonomy. We work hard enough at our craft. Jettisoning external impediments—like the messages that aren’t even ours—makes a lot of sense.

Do you notice that your writing gets a little easier when you dismiss the voices that aren’t yours?

Note from Jane: This post is based in part on “Who Taught You That?”, a tool from Anne Carley’s handbook, FLOAT: Becoming Unstuck for Writers now available in its second edition wherever paperbacks and ebooks are sold.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1885 followers