Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 26

January 23, 2025

Key Methods for Direct and Indirect Foreshadowing in Your Story

Photo by Nur Demirbaş

Photo by Nur DemirbaşToday’s post is by editor Tiffany Yates Martin. Join her on Wednesday, Jan. 29, for the online class The Art of Foreshadowing.

Imagine Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring in a brightly illuminated studio, or anything Goya ever painted rendered in blazing strokes of Thomas Kinkaid-style light.

In story as in art, what’s hinted at in the shadows can add intriguing layers of depth and interest.

Foreshadowing is a literary device in which future developments in a story are hinted at before they happen, presaging what’s to come. It adds dimension to stories just as shading and shadow add it to visual images: Foreshadowing can heighten suspense and tension, increase momentum, raise a story’s stakes, deepen and develop characters, and pave in key plot developments to give the story more cohesion.

But just as in visual art, the finesse of foreshadowing is in how and where you direct the reader’s attention: How much you use, where, and what effect it creates in the story. The artist achieves those results using dark and light tones. Authors have a similar palette to work with: various shades of direct and indirect foreshadowing.

Direct foreshadowingDirect foreshadowing is the kind readers are likely to notice, overt indications of future developments in the story that are generally used to create expectation, anticipation, or dread and thus increase suspense, stakes, and momentum.

Straightforward statements or detailsThis is the most overt type of direct foreshadowing, where some element of the story clearly sets up a future development.

In the first episode of season two of the Apple TV show Shrinking, for instance, Harrison Ford’s psychologist character tells Jimmy, a protégé in the practice who has been struggling since his wife was killed by a drunk driver, “You can’t spend your life hiding from your trauma. If you don’t truly deal with your past, it’ll come back for you.” The rest of the season deals with the fallout of exactly that happening, both literally and figuratively.

This kind of overt foreshadowing can be used anywhere in the story: within the narrative, dialogue, the title, epigraph, even the chapter or part headings. The title of Death of a Salesman flat-out portends the play’s ending. Liane Moriarty foreshadows central story developments that result from one of the protagonists opening a sealed letter with both the title of her novel The Husband’s Secret and its epigraph about Pandora and her release of “dreadful ills” into the world.

Prophecy and premonitionThese are explicit promises or statements about what’s to come in the story—even if they may not turn out to be literally true or are misinterpreted by the readers or characters.

This can be as straightforward as the literal prophecies the witches offer to Macbeth, which give him false confidence in his invincibility as king but whose meanings later prove catastrophically different from the way Macbeth takes them, or a fortune-teller who prophesies a character’s future that plays out in the story.

But prophecy and premonition can also come in forms that aren’t quite so literal, like one character telling another, “One day you’ll be sorry you treated me this way, and you’ll pay,” or the protagonist reflecting, “I had the disquieting certainty that nothing would ever be the same after this moment.”

Chekhov’s gunThe origin of this narrative principle arose from Anton Chekhov’s advice to a fellow writer: “One must never place a loaded rifle on the stage if it isn’t going to go off,” meaning writers should avoid making false promises to readers. But as a literary device it’s often taken more broadly to indicate an item or element that appears earlier in the story before playing a key role in it later.

In the recent Netflix series No Good Deed, a literal gun is used to foreshadow later events: Ray Romano’s character retrieves a revolver from a hiding place in his home and stashes it in his famous musician wife’s piano; both items later play pivotal roles in the story.

In Knives Out, the prominently featured collection of knives collected by the murder victim that viewers see displayed throughout the film plays a central role in the climax—an event also foreshadowed by the detective’s description earlier in the story of the eventually revealed killer as “Confident, stupid and protected, playing life like a game without consequence until you can’t tell the difference between a stage prop and a real knife.”

Indirect foreshadowingIndirect foreshadowing is often more subtle than direct foreshadowing, and may even go unnoticed by readers until the later events it augurs are revealed, or upon rereading. Most often it’s used in laying key groundwork for those later developments: paving in details about the characters or plot that will make them more organic, cohesive, and inevitable.

This type of foreshadowing is also likely to be employed more liberally than direct foreshadowing, precisely for those reasons: It’s an often crucial tool for adequately developing character and plot, and can be smoothly and almost invisibly painted into the story throughout, like the shadows in a still-life, to add verisimilitude and depth.

Breadcrumbs and cluesThis type of indirect foreshadowing isn’t just for mysteries and thrillers, but crucial in any genre to plant seeds for later developments that might otherwise feel unjustified or sprung on readers, or like an author device. Early in The Hunger Games, for instance, we see Katniss expertly using her bow and arrow to hunt for food—a skill that later plays an essential role in her survival of the titular games.

Threading in clues about a character’s test anxiety or panic attacks, for example, lends greater cohesion and inevitability when we later see they choke during the bar exam; clues about an estranged father and mention of the letter the protagonist wrote him that was never answered keeps his unexpected reappearance in act three from feeling like a deus ex machina; paving in breadcrumbs about a character’s paralyzing fear of heights organically sets up and raises stakes on their climactic struggle to walk onto the Golden Gate Bridge to talk their best friend out of jumping.

Indirect foreshadowing can also come in the form of a statement, but unlike direct-foreshadowing statements they may not be readily recognizable as foreshadowing until later, like the detective’s comment about the killer in Knives Out, or Haley Joel Osment’s character telling Bruce Willis’s in Sixth Sense, “Dead people don’t know they’re dead,” or a sleepless Tyler Durden at the beginning of Fight Club flat-out telling viewers, “With insomnia, nothing’s real.”

Echoed eventsEarlier events or developments in a story can presage similar later higher-stakes developments. In The Hunger Games, Katniss saves Peeta from eating poisonous berries, remembering her father’s warnings about them—an event later echoed at the end with a twist, when she gives them to Peeta so both can eat them to kill themselves together rather than turn on each other, and outfox the rules of the game.

In the Ryan Reynolds movie Free Guy, video game designer Keys and his programmer buddy Mouser enter their game as characters to track down “Guy,” a non-player character gone rogue, manipulating the game environment from the real world to advantage their characters in the game. Those actions are later mirrored in the climax when Keys is on his computer in the real world programming changes to help Guy reach a key objective within the game, as Mouser works against Keys on his own computer to try to stop them.

Symbols/motifsUsing symbolic representations of events to come is a sort of foreshadowing shorthand that can create under-the-radar tension and suspense in readers. In The Godfather movie, the appearance of oranges (the fruit) in a scene indicate impending death and violence; in The Sixth Sense the color red indicates when the spirit world is brushing against the corporeal one.

Readers may not pick up on the symbolism until later in the story or a subsequent read, but it can help create a subconscious expectation or foreboding and lend a feeling of cohesion or inevitability to the story.

Mood/tone/atmosphereThere’s a reason “It was a dark and stormy night” is such a literary cliché; setting a mood or tone can be a viscerally potent way of foreshadowing a story’s later events.

In the movie Edward Scissorhands, reclusive Frankenstein creation Edward lives in a bleak, dark castle atop a gloomy hill that looks down over a cheery pastel-colored community, foreshadowing the joy, belonging, and love he finds when an intrepid door-to-door makeup saleswoman brings him down from his stark solitude in the castle to her home in the neighborhood below.

The film Shutter Island opens with the main character seasick on a ferry traveling under a cloudy gray sky and haunted by creepily scored memories of his wife, headed toward the stark, shadowy, isolated island that houses the mental institution he and his partner have been sent to investigate. The moody atmosphere sets the tone of this dark, twisty story, creating a feeling of unease and dread in readers that signals the protagonist’s slow unraveling on the island.

Finessing foreshadowingUnderstanding the main types of foreshadowing is the foundation for executing it well.

Clumsily placed direct foreshadowing can feel heavy-handed and can actually have the opposite effect you intend, defusing suspense rather than accelerating it.

Inexpert indirect foreshadowing can feel cryptic or confusing to readers if it’s too vague. Or if underutilized, it can undermine the cohesion of the plot and make later developments feel inauthentic or sprung on readers.

The key to finessing this powerful device is understanding what type to use, and where, to shade in the story’s depth, meaning, and nuance.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Wednesday, Jan. 29 for the online class The Art of Foreshadowing.

January 22, 2025

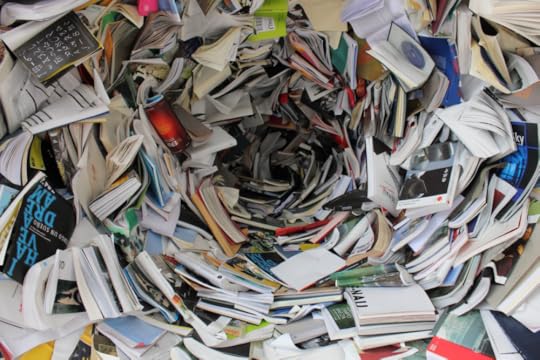

3 Aspects of Managing the Clutter-Tidiness Continuum

Photo by Pixabay

Photo by PixabayToday’s post is by writer and creativity coach Anne Carley (@amcarley.bsky.social) who believes #becomingunstuck is an ongoing process.

When we feel in opposition to our surroundings, we suffer needlessly. When things are too chaotic, we sometimes push to reduce the chaos—cleaning, sorting, donating, pruning—while sometimes, paradoxically, we blunder toward denial, distraction, and further cluttering. One more aspect of the clutter–tidiness continuum is the recognition that your own preferences may change. For example, does the occasional tidying sweep of your desk cheer you up? Do you discover, while tidying, those notes and files that you knew had gone missing? Or do you enjoy piling things up for the duration of a project and then doing a massive celebratory cleanup at the end?

External objects aren’t the only things to consider. When a project itself is confusing to you, that can be a sign that it’s time to stop ignoring the skewed relationships and cluttered thinking that may have gotten you there. Following is a quick look at ways to unclutter stuff, people, and the words we write.

1. Uncluttering StuffIt’s true that clearing objects can clear your head. But sometimes maintaining physical chaos is a way of exerting control over something—anything—when the rest of life can feel out of our hands. Not-clearing might not actually be about stuff at all, perhaps concealing a fear of death instead.

Note: Clutter can be entangled with responses to deep trauma. Trained trauma-informed experts know gentle and effective ways to work with these matters.

Oliver Burkeman reassures us that, once we accept that life’s too short for us to get it all done in one lifetime, we can relax and just choose one next step. Anne Lamott puts it this way: “I think perfectionism is based on the obsessive belief that if you run carefully enough, hitting each stepping-stone just right, you won’t have to die. The truth is that you will die anyway and that a lot of people who aren’t even looking at their feet are going to do a whole lot better than you, and have a lot more fun while they’re doing it.”

Chaos and orderDo you know how much chaos you thrive in? Where are you on the clutter-tidiness continuum? As Dahlia Lithwick so succinctly asked, are you a Chaos Muppet or an Order Muppet? This question, answered honestly, may help you as you shape your work environment to suit you and support your creativity. One person’s cluttered studio is another person’s warm and happy workplace. Know yourself. To me, one key to understanding your acceptable level of chaos is whether you can find the resources you need when you want them. If you can, then the ‘clutter’ may not be important.

Other peopleYou can enjoy a lot more latitude around the nature of your workspace if you can reserve it for yourself alone. If, instead, it’s in a shared space, whether with loved ones, housemates, studio mates, fellow coffee-drinkers, or your landlord, you’ve got some additional considerations to manage.

2. Uncluttering PeopleSpeaking of people, is it possible you need to pull back from some relationships that are cluttering up your creative life? For me, even though there are ways to say no that I am theoretically comfortable with, I still hear this inner voice sometimes that tells me being polite, or just going along, is more important than standing up for what is important to me. Early childhood training, I guess. Can you relate?

Let’s say that you’ve known this person for years. They are routinely self-absorbed, critical of others, including you, and negative in their view of the world. On the other hand, they’ve been helpful to you in the past, in your career, and maybe even as a friend. Can you turn your back on them now? Maybe so. Is your obligation to maintain a relationship more important than your values, your wellbeing, and your meaningful creative work?

Where are you when it comes to people who crowd your psychic space? Are those relationships worthwhile for you now, in light of your creative priorities? Are they chaos agents at a time when you could use a little more order in your life?

3. Uncluttering WordsAnother area where clutter can accumulate, besides with stuff and people, is in the written texts themselves. Are there places where the words don’t sing? Do saggy sentences get you down? Revise your work like a slightly impatient stranger would. Remove extra words/notes/figures/ideas. Don’t say the same thing two or three ways. Cut. Cut. Cut. Remove the cut material to compost if you like. You’re not murdering your darlings, just keeping them somewhere cozy, off to the side.

Here’s one example that can have a big impact: Search your writing for unintentionally included filter words that distance the reader from your meaning. A long manuscript of mine once dropped a few thousand words that way. What a great pleasure that was to lop them away, bit by bit.

When you unclutter your words, in effect you are challenging yourself to take creative risks from a place of strength. This means looking at yourself differently. Being bold. It’s a shock to see how different life is when it’s not governed by fear. The fear doesn’t go away. You can’t expect that to happen. Living with it though, on good terms, can really work.

Bookshop • AmazonBit by Bit

Bookshop • AmazonBit by BitUncluttering your stuff, the people in your life, and your words can streamline your entire process. You can take this challenge on gradually, one task at a time, and pace yourself according to your shifting moods and capabilities. Bottom line: When you reduce unwanted clutter you reduce daily stress, which opens up lovely new possibilities for your creative life.

January 21, 2025

How to Find Your Memoir’s Narrative Arc (There May Be More Than One)

Photo by Willian Justen de Vasconcellos on Unsplash

Photo by Willian Justen de Vasconcellos on UnsplashToday’s post is by Bonny Reichert, author of How to Share an Egg: A True Story of Hunger, Love, and Plenty.

It was a frigid January afternoon, four years ago, when, after a pile of earlier drafts, I sent the version of my book proposal that my agent finally deemed “ready.” We had met at an online speed-dating-type event for authors and agents and, after signing, we’d been working together on this one document for about six months. Many parts of the proposal, like the pitch and the summary, the description of audience and the proposed marketing plan, had come together relatively easily.

“But how are the outline and chapter summaries coming along?” said my agent—I’ll call her Jenn—every time we spoke on the phone. “What about the narrative arc?”

“Right,” I said firmly. “I’m working on that.”

“Good,” Jenn said. “Because honestly, nothing is more important than the arc.”

Bookshop • Amazon

Bookshop • AmazonThe book, How to Share an Egg: A True Story of Hunger, Love and Plenty (released today, with Ballantine PRH in the US and Appetite PRH in Canada) is a food memoir about my experience growing up in the shadow of a traumatic family history, and my journey toward discovering who I am in spite—and because—of that history.

My dad almost starved to death during the Holocaust, and it was stepping into the kitchen and becoming a chef myself that ultimately helped me find joy and make peace with the past. But back when Jenn and I were working on the proposal, I knew the book was about food and my dad and resilience and the Holocaust, and not much more. A progression? An arc? Truthfully, I had no idea.

What I did know was a bit about how to fake it ’til you make it. So, I began to map out chapters, corresponding to key events from my past, as well as foods and food memories that were significant. Soon I noticed clusters: a large cluster of events (and flavors) from childhood; another forming around a short trip to Warsaw I took with my dad as a younger adult; a third big cluster from a more recent solo trip to the ghettos and concentration camps of Poland. From there it wasn’t much of a leap to see that the book would begin in childhood and end sometime after that second trip to Poland. To find the arc, all I had to do was connect the dots chronologically, right?

For the proposal, I managed to create chapter summaries that were fluid enough to convince Jenn that I had the arc figured out, and good enough to get the unwritten book sold at auction in both the US and Canada with a few sample chapters. It was a better outcome than I could have imagined, and I was thrilled. It was not until I started to write in earnest that I realized I had a problem.

The problem was not the first third of the book which, in my outline and summaries, was too long and too detailed but still well defined. Nor was it the last third which, once I had come up with my structure, came to me in a rush, almost fully formed. No, fellow writers, it was the middle, which was a thin rickety bridge I was trying to build between the solid poles of beginning and end.

A memoir is not the story of your life, but a story from your life. I knew this and yet, I didn’t really understand it until I found myself attempting to write my way from childhood to midlife without stopping at every heart break, career change and childbirth along the way.

I did my best, and I got my first draft in on time. When it came back from my editor, it had many admiring and encouraging notes, but the ones that said, about some of the middle chapters, “Why is this here?” and “What does this mean?” were the most confounding. And the most important.

I struggled with the next draft for several weeks, until my editor helped me realize I had to take the middle of the book apart to liberate it from the constraints of strict chronology. I had to cut and regroup and sharpen. I had to transform real life into a narrative path specific to my book, my themes and my message.

Here are some of the tools I used to make that transformation:

Chart the emotional journey of the book—try to draw it. Where is the inciting incident, rising action, climax(es), denouement? Where is the book flat, emotionally?Dig deeper into those flat or saggy sections. Use reverse outlining to discover what those passages are saying and doing within the context of the book’s journey.Move problem sections around according to narrative and emotional logic. For example, when I reverse outlined, I noticed I had a few different moments of “existential crisis” sprinkled over seventy pages. Once I decided to group them together thematically, the section began to sing.Understand there will be many things you want to say that don’t fit the book you’re writing. What is emotionally resonant in your life is not necessarily the same as what resonates for the reader inside the world of the book.Don’t try to force your story into any particular shape. The point is just that you’re working deliberately and charting a path with intention. Some “arcs” are not arcs at all but zig zags, spirals, reverse arcs, etc.How to Share an Egg was in copy when I was preparing to speak at a memoir conference on this exact topic last spring. It had been several weeks since I’d looked at the book, and I pulled out the bound pages my publisher had sent and studied them with a little more distance. It was only then that I noticed something I hadn’t seen before. The book doesn’t have one single arc, but rather, a series of them: There is the main arc that carries the plot about the character (me) and her journey to come to terms with her family’s past (the Holocaust), and then there are others—a “food arc,” that traces the culinary journey of the book; a “dad arc” that charts the changing relationship between father and daughter; a romantic arc that tracks a divorce and the relationship after it, etc. The arcs overlap, and they peak and valley at slightly different times, but overall, their shapes are similar, resolving, for the most part, by the end of the book.

Before my talk last spring, I charted these arcs on a sheet of paper: black for the main arc, pink for food, blue for the Dad arc, and green for romance. Together they look like a colorful mountain range. I keep this diagram taped to the wall near my desk as I begin work my next book. It’s not that it’s going to help in any practical way—every book is different, and I know there are no shortcuts. Still, it makes me happy to know my creative mind was making something logical and organized before my quotidian self even had a clue.

Learn more about How to Share an Egg: A True Story of Hunger, Love, and Plenty by Bonny Reichert.

January 16, 2025

How Deliberate Practice Can Develop Your Writing Skills and Talent

Saint Jerome in His Study by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1480)

Saint Jerome in His Study by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1480)Today’s post is excerpted from Deliberate Practice for Creative Writers by Jules Horne.

Do you believe excellence is in someone’s nature—an innate golden gift they were born with?

Or does it come from nurture—learning, effort, passion and commitment?

Of course, nature versus nurture is a false dichotomy. Born talent and learned talent—in any skill—can’t be separated. They reinforce and inspire each other.

But still, it’s good to examine critically the theory that some people are natural born geniuses in their field, while others get there through learning and practice.

Because one way of thinking is empowering, and the other is profoundly disempowering. And I definitely prefer empowering.

Let’s look at nature first—the idea that people excel because they’re a natural born star.

Well, it’s true that some people have enormous natural advantages in life. Maybe you’re supersensitive to audio and sound pitches, and become a musician. Or have an amazing eye and steady nerves, and try your hand at archery or wildlife photography.

And then, there’s your environment, which is immensely important for learning.

We all have latent talent for many things—writing, gardening, engineering, leadership. But we become good at specific things, in part because of the people and opportunities around us. Mentors, inspirational people, and access to practical equipment.

Bill Gates had a basic computer as a teenager, and spent hours hunkered away, learning how to use it.

The Polgar sisters had a chess-savvy father as their personal trainer.

If you’re a keen angler, you might have friends or family who go fishing, and nurture your interest.

If you’re a guitarist or drummer, you might have friends to jam with, and tips and musical inspirations to share.

Those extra factors spark your latent interest, and make you keen to learn more. So, it’s a self-reinforcing loop.

But maybe you’re on your own, with an unusual passion that nobody else in the neighborhood really gets?

Well, that can be motivational, too. Maybe you have more determination despite everyone—precisely because you’re on your own.

The poet Emily Dickinson was an unconventional recluse whose work was mostly unrecognized in her lifetime. Ray Bradbury was mocked as a child for his love of science fiction and fantasy. The painter Vincent Van Gogh was also marginalized for his uniqueness. The professor of animal science Temple Grandin was misunderstood due to her autism.

Yet all persevered with great passion and became outstanding and influential in their field, despite their uniqueness—or because of it?

Maybe if other people don’t helpfully validate you, you just get on with what you love?

Nature and nurture are so complicatedly interwoven with our individual psychologies and situations.

And in the history of education, the emphasis has shifted between nature and nurture, with each dominating at different times, as different research findings and ideologies come through.

During my teacher training in the 1980s/90s, nurture was dominant. The thinking was: Excellence isn’t simply an innate talent. It can be taught and practiced. This learning movement was influenced by the work of psychologist B.F. Skinner on behaviorism.

The focus was on learning through physical actions, rather than just mental states. “Skills and drills”, repetition and practice, were the way to go.

If you learned French at the time, you might recall the words écoutez et répétez—listen and repeat. I’m a visual learner, so it didn’t go well for me.

Try this

Take a moment to think through times when you learned effectively, and when you didn’t. What sort of situations? Was it quiet, noisy, calm, busy? Were you on your own, with a coach, or in a classroom? What senses were you using? This will be useful for when you’re designing your own unique deliberate practice.

But in time, the pendulum swung in the nature-nurture debate. At the turn of the millennium, influential books such as The Nurture Assumption by Judith Rich Harris and The Blank Slate by Steven Pinker reasserted a focus on nature.

Harris found that learning was more influenced by genes and peer groups than by the nurture of parents and the home. Pinker emphasized biology, rejecting the idea of humans born as blank slates and created by their cultural surroundings. Nature was back in charge.

However, the pendulum has now swung firmly back to nurture, and the importance of learning and practice. This still holds today. It’s a far more more optimistic view, and aligns well with new opportunities for bitesize and individualized learning online.

What led to this change? A big influence on the swing back to nurture was a research paper with the unwieldy title, The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance. This study by Professor Anders Ericsson looked into what it takes to make an expert. And it might have stayed hidden in academic backwaters, if it hadn’t inspired Malcolm Gladwell to write his bestseller, Outliers: The Story of Success.

Even if you’ve not read the book, you’ve probably come across the 10,000 hours idea: that to achieve excellence in any field, you need to put in around—well, 10,000 hours.

The catchy number popularised by Gladwell ignited the public imagination. Maybe we can all become superstars, if we put our minds to it?

To me, it sounds both encouraging and impossible, so I’ve chunked it down to a more manageable concept. It works out at about 20 hours a week, across a decade. That’s about three hours a day, every day, for ten years.

At this point, intriguingly, 10,000 hours starts to chime with other time and practice concepts: Stephen King’s 2,000 words a day, every day. Ray Bradbury’s daily writing in the library, a story a week. Ursula LeGuin’s daily schedule.

The upshot is: it’s about putting the work in.

Of course, 10,000 hours of practice is simplistic. Not everyone who puts the work in achieves excellence.

There was an inevitable backlash. It’s a myth! I’ve been playing guitar for 40 years and still haven’t improved. 10,000 hours will never turn me into a shot-putter—I don’t have that physical ability.

But neither Gladwell nor Ericsson claimed that 10,000 hours of practice is a cast-iron guarantee of success. Ericsson simply uncovered a rough average time that skilled performers took to reach expert level.

And his crucial finding: it’s not about the number of hours you practice—it’s about how you spend them. Quality, not quantity. And the key is: deliberate practice.

Ericsson’s research showed that deliberate practice is a powerful learning strategy for improving performance. He discusses the psychology, the process, and, importantly, practical ways to apply it.

His findings are now a significant element of best practice in education and learning.

Do an online search for “deliberate practice in education,” and you’ll find thousands of sites where teachers are discussing the topic. Deliberate practice is viewed as the backbone of purposeful, systematic learning.

This makes it a great fit for individualized learning, for self-study, and for people short of time.

So many of the literary life stories we love to read are wild, exciting whirlwinds of romance, genius and rock-and-roll habits. If you love this, and find it helps you to write, great.

But if you’re skeptical, it’s worth looking into what might lie behind it, and how deliberate practice can help.

Try this

Invent your own muse. Think back to people who have inspired you in the past. Who lights up your life and gets you excited? Who challenges you with their incisive views and new knowledge? Who is a stern, wise critic who takes no nonsense and sets high standards? Who is way ahead of you on a similar path and is someone to look up to? Who makes you feel strong and alive as a creator? Brainstorm your ideal attributes, fuse them into a character, and have a conversation with them. You might start by asking questions: “What do you want to tell me?” “What do you see as my biggest challenge?” and writing what they tell you.

Try this

Consider the opposite of your ideal muse—your anti-muse. What sort of attributes do they have? What experiences have felt to you like an anti-muse? Brainstorm what you find. What can you learn from this about your needs? What relationships and experiences help you to thrive, and what makes your creativity wither? If you consider the anti-muse as a character, how might you transform them into writing gold, and loosen their power?

Try this

Set up an invisible committee of mentors. You have an unlimited budget, so choose the best. The people can be real or fictional, close family, media stars, historical figures. They don’t have to be friendly, or patient—any committee needs a mix of skills and viewpoints. Crucially, they’re all on your side. You might like to look into Carl Jung’s archetypes to discover more about the internalized mentor figures we all share, or draw on a mix of modern and older archetypes: the Sage, the Critical Friend, the Healer, the Rebel, the Trickster, the Innovator.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out the book Deliberate Practice for Creative Writers by Jules Horne.

January 15, 2025

Get Out of the Silo

Photo by Masood Aslami

Photo by Masood AslamiToday’s post is by writer and creativity coach Anne Carley (@amcarley.bsky.social) who believes #becomingunstuck is an ongoing process.

We’re not alone.

As creative people we want to be alone—and sometimes need to be.

But underneath it all, we’re not alone. We’re primates, which means we’re fundamentally social creatures.

It’s easy for me to forget this truth, and to my detriment. Recently, I got a great reminder. I hope that sharing it may be helpful to other writers who tend hole up in a writing silo of their own making.

A cool acronymThere’s this nonfiction book I’ve been working on for too long. Starting out, it was going great. I had a clear vision, the words flowed easily, and I got some colleagues and readers excited about my ideas. I even had a cool acronym to organize the book around. Then my life blew up. Soon after, the pandemic began. I told myself I could power through anyway, but the book withdrew into a coma. I tried unsuccessfully for a long time to revive it regardless of the chaos surrounding me.

A few years passed, during which I focused my writing on other things. Eventually, I felt ready to return to the comatose nonfiction book project, unseen for years by any eyes but mine. My attitude was good. I could do this. Except I still couldn’t.

I looked at the sentences and paragraphs and chapters in my document. There was plenty of good stuff there. I reviewed constructive comments from early readers of sections of my manuscript. They should have encouraged me. But everything felt distant. I was trapped by the words that were already in place. Even the structure felt off to me.

Get freshFirst, I thought the problem was that the work was stale. I had moved on from the ideas that were frozen in this draft. Good news, right? Over the past few years I’ve learned some things that will be helpful, so why was that a problem? Usually having new insights feels good, because it will improve the overall project. Somehow, I felt stuck on the ground, unable to rise above the words already in place and seed them with fresh ideas.

I continued making false starts, convinced that once I got the creative perspective I needed, things would flow again, as they had when I began, years earlier.

Progress was not made during this period. Although I returned time and again to the manuscript, I left each session having changed next to nothing in the pages. The book was already about 75% complete, so what was the #$%^ problem????

Structural flawsThen came another a-ha moment: The problem wasn’t that I had some new, good things to add to the book and didn’t know where to put them. The problem was the structure itself. I had that cool acronym, and wanted the material to organize itself around the letters into four sections, each a key pillar. But it wasn’t really working. The four sections weren’t equal in weight, or thickness, or nature. A house built on this foundation would topple.

PeoplingThis is where other people came back into the picture. The project and I got out of the silo. Finally!

When it came to the stalled book project, I’d been keeping everyone, writers and non-writers alike, at arm’s length throughout this multi-year period. The most I would say out loud is that I was waiting to return to the project when the energy was there to do a good job.

One day, over coffee with a writer friend, I surprised myself and got into it. My friend was interested, and we had just been talking about their writing struggles, so I went for it, excusing myself in advance if I got too granular with the details. I explained the book project, why I (still) believed in it, and where the problems lay. A lively conversation ensued. Looking a little wary, my friend suggested I needed a different acronym. A veteran of writer groups, I reassured myself not to get defensive, and listened with an open mind. Hmm. My friend made a good point. I said thank you, and resolved to re-think the matter.

My journal entries for the next week or two were full of experiments. Combinations of letters on page after page of my black-and-white college-ruled composition book document the brainstorming process. Nothing quite worked, though, to replace my anchoring acronym.

Whut?Then, on a call with coaching colleagues, it was my turn to bring a problem to the group. I mentioned the whole unfinished book/unsatisfactory acronym thing. And one of my colleagues spoke up. Very quietly, they delivered a truth I really needed to hear. “You know, you don’t have to have an acronym.”

Bookshop • Amazon

Bookshop • AmazonIt was a d’oh moment. Once you see it, you smack your head for having been blind to it for so long. Not only was the acronym structurally unsound, it also forced a false emphasis, away from what I could now see was the heart of the book. The tail no longer wagged the dog. Whew.

Free from the perceived need to have one short word to rule them all, I am looking at the manuscript with fresh eyes. At last. Is the book magically complete? No. Not yet. Traction has resumed, however, and boy howdy does that feel good.

My takeaway from this saga? Get out of the silo. Remember you have friends and colleagues out there in the world. Talk with them. See what happens. Repeat as needed—actually, maybe a little more often than that.

January 14, 2025

Avoid a Creative Slump By Writing and Publishing in a Different Medium

Photo by Google DeepMind

Photo by Google DeepMindToday’s post is by author, filmmaker, and podcaster Elizabeth Rynecki.

Through a quirk of fate, I avoided the dreaded “first-book comedown” that often follows the publication of a debut work. The feeling of having poured everything into a single personal project and then wondering, what’s next? never quite hit me. That’s because after the release of Chasing Portraits: A Great-Granddaughter’s Quest for Her Lost Art Legacy (NAL/Penguin Random House), I pivoted to finishing my documentary film.

Also called Chasing Portraits, the film wasn’t a replica of the book. Instead, the film echoed the story I told in my book. That said, I should be clear: I didn’t actually dodge the slump, I just postponed it—I hit the proverbial wall when it came to finding project number three. But I carried forward an important lesson from projects one and two: Writing in an entirely different medium gives you the opportunity to explore storytelling in fresh and interesting ways.

Initially after the film screenings came to an end, I thought I’d write about my father’s ship salvage career. For more than 30 years my father traveled around the world helping rescue, repair, or recover maritime vessels in distress. But as I pondered my approach, working through his substantial archive of write-ups, reports, and photos of stranded or damaged ships, my younger son’s challenges with ADHD became increasingly debilitating. Strangely enough, as my focus bounced between the two subjects—and as improbable as this sounds—my father’s ship salvage stories slowly metamorphosed into metaphors for understanding my son’s ADHD.

As I debated writing about this unorthodox and unexpected combination, I tried explaining it to my writing group. They didn’t quite grasp the concept of the interwoven essays I envisioned, but encouraged me to follow my heart. Eventually, I had a manuscript. One that I loved and that I felt readers would find compelling. I told agents in my query letter that the book offered readers not a guidebook, but a lived experience of parenting a neurodivergent kid. Unfortunately, the literary agents I queried didn’t share my enthusiasm for the book.

But then something remarkable happened. A friend read the manuscript and he did find it compelling. More importantly, he asked, “What if we turned it into a podcast?”

At first I panicked. I knew shifting to a radically different format wouldn’t just be about moving paragraphs around, killing darlings, and rewriting dialogue. This would require my fully rethinking how to tell the story. But then I remembered a key lesson from my prior projects: different media help you tell your story in different ways.

I decided to go for it, because while I knew this would test me in ways that stretched far beyond a mere rewrite, telling my story in podcast format was a chance to immerse myself and the audience in a very different experience. And ideally, if we (my friend helped with the writing and took the lead on producing the podcast) did it well, we could not only transport listeners into the heart of my family’s stories, but we could add more perspectives of ADHD that could help give the audience a deeper and broader understanding of ADHD.

The process of coming up with the episode format, figuring how to weave together my story, the shipwreck stories, and ultimately the stories of our close to two dozen interviewees, was a process of trial and error. Sometimes what looked good on the page sounded terrible when we recorded it, and sometimes things that didn’t look quite right on the page, flowed well in audio.

Eventually we found our voice for the podcast, both metaphorically and literally, as we decided that I should narrate it. Which, even though I’d done the voice-over for my documentary film, led to my seeking out a voice lesson from a vocal narration coach to help me get closer to the delivery we wanted to nail. As my podcasting partner and I reimagined my original manuscript into a series of six podcast episodes (each focused on a different ADHD topic and different salvage effort), we quickly realized that, while podcasting is very much a modern form of oral storytelling, the medium demands a different structure and rhythm. Our podcast (That Sinking Feeling: Adventures in ADHD and Ship Salvage) required a different balance of pacing, tone, and sound design.

For me, the shift from book to podcast wasn’t about abandoning my book—it was about finding a different but equally compelling through-line. In writing, you can craft a cadence with punctuation to emphasize meaning. Transforming the book into a podcast allowed us to layer the narrative with more nuance. Instead of simply quoting my father’s words on the page, listeners would hear directly from him. And when a ship crashed and exploded into flames, we could do more than just describe it—we could share the actual audio from a U.S. Coast Guard film, making the disaster feel much more immediate.

This isn’t an argument that every author should turn their book into a limited series podcast. But I do believe that the experience of writing for different media is a worthy endeavor. I know a number of authors who have taken filmmaking classes in order to think about book scenes from a movie-going perspective. Other authors have written stage plays to better understand their characters. Writing for different media engages our imaginations in profoundly important ways. And learning to think more critically about how sound, tone, and narration work to carry a story is a worthwhile exercise for all writers.

This is all to say that authors need to be willing to consider beyond the act of writing words on a real or virtual page when trying to best tell a particular story. Ultimately, I think we as writers need to have a very broad view of what counts as reading. This really isn’t a radical idea in the current media environment: the idea of what counts as reading has evolved dramatically over the past 20 years, first with the rise of audiobooks and then with the ubiquity of podcasts and social media. While some people cling to the traditional definition of reading as engaging with printed words on a page, many of us now understand that reading extends far beyond the confines of physical paper. We listen to stories as much as we read them, and watch them too. The underlying lesson for me is that all media have the power to convey emotion, information, and imagination. The question is which is the best way to tell a particular story, and there may be more than one answer. As technology evolves, and our experience with different formats grows and shifts, so too does storytelling.

Podcast storytelling—as opposed to the interview format—offers the potential for a deeply engaging and personal way to engage with audiences. So if you’re an author looking to make a meaningful connection with your audience, it’s a format definitely worth exploring.

For me, pivoting to a different storytelling format has never been about choosing one medium over the other. It’s about embracing the unique strengths of each format. Whether you’re holding a book in your hands or listening to a podcast episode, you’re still engaging with a story, expanding your understanding, and growing. In the same way that it’s important for authors to read widely across genres, styles, and structures, I believe it’s equally essential for writers to consume stories, regardless of source or format. You never know how shifting from one medium to another might spark fresh insights or help you approach your writing in new, unexpected ways.

January 13, 2025

Don’t Write Every Day: 3 Things to Do Instead to Finish Your Book

Photo by Tima Miroshnichenko

Photo by Tima MiroshnichenkoToday’s guest post is by Allison K Williams (@guerillamemoir). Join her on Wednesday, Jan. 15 for the online class Organize Your Writing Life.

We’ve all heard the famous writing advice:

“I like to get ten pages a day, which amounts to 2,000 words. That’s 180,000 words over a three-month span, a goodish length for a book.” —Stephen King

“I only write when I’m inspired, so I see to it that I’m inspired every morning at nine o’clock.” —Peter De Vries

“Just write every day of your life.” —Ray Bradbury

Write every day. Build a habit. That’s the only way you’re ever going to finish a book, right?

Wrong.

I don’t write every day.

I don’t even write every week.

I’m a “binge” writer. With no children, pets, or family members who need care, I’m able to carve out 3–10 days about twice a year to do personal retreats, in a rental apartment or a hotel room. I try to pick places near grocery stores (snacks!) and where it’s easy to take a long, thoughtful walk between chapters.

My binge-writer friends with dogs and toddlers and aging parents try for a weekend or even an afternoon away from the house, with their phone off so they aren’t tempted to “check in.” It can feel weird to separate yourself so firmly from the people you love. But modeling dedication, focus, and commitment to a creative project is also good parenting!

Perhaps writing on a more regular schedule works better for you. You might have a job you enjoy, or students’ work to read, or be the primary keeper of your home life. You value regularity. Rhythm in a schedule helps you focus. Andre Dubus III wrote House of Sand and Fog 17 minutes at a time, sitting in his car after leaving for work 17 minutes early.

As writers, it’s tempting to agonize over the best system, or try to write with the pattern of a writer we admire. But it doesn’t matter which method works best for you.

All that matters is that you choose a project, write it, and ask for support.

ChoosingNarrow your focus. Most writers I know have at least two projects rattling in their head, and it’s difficult to gain the kind of deep, sustained focus writing needs when you’re switching from one world to another. Imagine you’re about to walk through a magic door. On the other side is a guarantee you’ll finish a book, it will sell, and people will love it (if only!). But you can only take one manuscript through the door with you. Which one?

Say a gentle “I’ll be back” to your other work, and see what happens when you focus on one.

WritingWrite on the schedule you want—but make that schedule. Notice how you work best, and work that way on purpose. Maybe you are a daily writer who loves the rhythm. Maybe you’re better at the last minute. If you’re a daily writer, block it on your calendar like a class you paid for. If you’re a binge writer, look ahead and choose the hours or days of writing time. Start accommodating that time now—clear your list, let people know you’re out of commission, block the calendar.

AskingHaving a writing buddy to show up for motivates me a lot. Sometimes I meet a friend to write quietly together on Zoom, or at a cafe. Sometimes I make a deal that I’ll send them pages each day I’m writing. They aren’t obligated to give any feedback, but knowing someone’s waiting makes me push a little farther than working alone. If you have children, ask them what they care about finishing—can you schedule family time where everyone is working on their own painting/dancing/video editing/writing, and you come together to report on progress? (Maybe give prizes for making it through a session without interrupting anyone else!)

As a binge writer, I used to feel lazy and fake, because of course a real writer would use their time better. They’d spring from their bed, rush to the laptop, and bang out their daily word count, just like a real job! And since I didn’t act like a “real job” I must not be a “real writer.”

Then I realized how I work. I’m not starting from nothing. I don’t touch my manuscripts every day, but I stay in touch with the practice of writing sentences and micro-essays on social media. I write most blog posts shortly before they’re due, but I know the rhythm of a post and what makes a click-y headline. I keep a long list of blog post ideas. Every day on social media and in my email, I see what writers care about, what challenges they’re facing, and I think about what advice will help, making notes for when it’s time to write.

As you fit your writing process into your life, enjoy the things you value that take time. Very often, I’m neck-deep in someone else’s manuscript, teaching a webinar, or leading a retreat. I love and value doing those things. And while we can half-ass the things we don’t value to make more time for writing (teach the kids to cook! stop answering email!), it’s harder to pull time and focus away from things we care about doing well. Remember that keeping in touch with your writing isn’t always sitting down at the keyboard to make that day’s word count. Sometimes it’s thinking through ideas in the shower, building up your story in your head, making notes in your phone or your notebook. Sometimes writing looks like typing, and sometimes it looks like keeping in touch with your world.

And fellow binge writers? There are plenty of “real jobs” that operate on the model of “have a baseline of skill and resources and then do it all at the last minute under pressure.” Surgeon. Firefighter. Pilot. And in my case (and maybe yours), Writer.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Wednesday, Jan. 15 for the online class Organize Your Writing Life.

January 9, 2025

The Surprising Complexity of Picture Books

Photo by Kindel Media

Photo by Kindel MediaToday’s post is by author and book coach Janet S Fox.

To most readers, picture books appear to be simple stories, easy to write and short in length. New writers often enter the world of writing for children by attempting to write picture books rather than longer form stories, only to discover that picture books are not easy to write at all.

Good picture books are complex and layered, structured as carefully as a novel yet linguistically closer to a poem. If you are a picture book author but not an illustrator, you need to know how to make a text that will allow room for the illustrator to bring their vision to the work and yet create a complete story.

Protagonist, antagonist, rising and falling action, arc of change, emotion—all of these must be developed in a picture book, and generally with a word count of under 500 words. The words used must be simple enough to be understood by the youngest readers yet engaging enough to entertain adults.

Plot arc is one facet of picture books that can be almost invisible. Yet like all great stories, the arc of character change must be present, and must be driven by cause and effect and not a random string of events.

For an example, let’s study the plot of the picture book Big, written and illustrated by Vashti Harrison. (For you writers who do not illustrate, I have concrete takeaways.)

Cause and effect structureFor everything that happens in a story—including a picture book—the next thing that happens must be a result of what came before. More importantly, what happens next must be the result of what your protagonist has done, for better or worse. Otherwise, your story becomes no more than a string of events.

One inspiration for this way of looking at cause-and-effect forces is a plot plan devised by the movie studio Pixar as #4 in their “22 rules of storytelling” (originally shared on what was then Twitter by Pixar Story Artist Emma Coats), in which you can see how this works:

Once upon a time there was [something].Every day, [something happened]. But one day [something new happened].Because of that, [something else happened].Because something else happened, [something else happened].Until finally, [the final thing happened].And ever since that day, [there was something new].When we fit the Big concept into this template, this is the arc of its story:

Once upon a time there was a little girl with a big heart and big imagination.Every day, she grew and grew. But one day she grew very big in her body, too.Because of that, people around her laughed and scolded and teased.Because they teased, the girl felt she didn’t belong anywhere, like a great big nothing.Until finally, she decided to make space for herself and tell people they’d hurt her.And ever since that day, she liked herself just the way she was.For each action of the protagonist, there must be forward momentum toward both an external goal and an internal desire. Your character must do things in opposition to the antagonist, and because of what they do, things will happen, and that chain of events will lead to an entirely new life for the character.

It’s the words “because of” that are important here:

Because of that, people around her laughed and scolded and teased.

Because they teased, the girl felt she didn’t belong anywhere, like a great big nothing.

The little girl’s external goal is to not be teased and humiliated. Her internal desire is to be accepted for who she is—to belong. The antagonist is everyone around her who criticizes her and puts her in a box from which she must break out to achieve her desire and goal.

Let’s look at Harrison’s actual text, in italics, at each of the story arc steps:

Once upon a time there was [a girl with a big laugh and a big heart and very big dreams].Every day, [she learned her ABCs and 123s, she always said please and thank you…and it was good]. But one day [something big happened].Because of that, [it made her feel small].Because something else happened, [she began to feel not herself].Until finally, [she let it all out…and decided to make more space for herself and was able to see a way out].And ever since that day, [she was just a girl, and she was good].Big has a total of 275 words, not including the illustrated “background” words, and is long for a picture book at 56 pages, not including the foldout; many of those pages are wordless. Of course, one part of the brilliance of Harrison’s story is the way she uses her illustrations, with the girl literally pushing the boundaries of her world until she can break free of others’ negative words.

But her text follows the Pixar template almost to the letter, which creates a complete story arc, with change in the protagonist and cause and effect.

For non-illustrating picture books writersYou who are solely writers must give the illustrator room while limiting word count. Harrison’s small word count is evidence that a picture book is a marriage of poetry and imagery, and this plus her use of a perfect story arc provides an example writers can follow.

Apply this lesson to your idea:

Fashion a story concept that has an arc like Big.Think about the illustrations to a point but leave plenty of room for the illustrator’s imaginative additions.Treat the words as you would if you were writing a poem, with spare, clean language and power-packed metaphors.Use the Pixar template—first, to fill in your concept.Now fill in the template with your actual text, 275 words, more or less.Does your story work with the arc of story, character change, rising/falling action, and cause and effect?

January 8, 2025

When It Lights Up–and When It Doesn’t

Photo by Quentin Guiot

Photo by Quentin GuiotToday’s post, the first in a series, is by writer and creativity coach Anne Carley (@amcarley.bsky.social) who believes #becomingunstuck is an ongoing process.

An artist friend agreed to make the visuals for a video game under development. The brief was to produce tiny, colorful, woodland animals with expressive faces and body language. But super tiny. On a short deadline.

The struggle was real. She only had a few weeks’ time, and the medium, tools, and minuscule scale were all new to her. When we spoke during that period, I could hear the added tension in her voice. She has high standards and wanted to live up to them. Also, as a member of a small team, she felt a lot of pressure to excel, not to let anyone down.

To begin, it was essential that she learn some new game developer software. She applied herself. Frustration and anxiety ensued.

Then one day, her brain and her being pulled all the new information and experiences together. As she explained, “It all lit up for me.” From then on, she could work fast and well. Time flew, and she immersed. She delivered her work for the project on time, and the team got the job done.

Embracing the processThose conversations with my friend reminded me how much of creativity is process. Annoying, unpredictable process can often fill more of our creative time than the fun stuff.

Lurching, staggering, doubling back, sighing, ranting, exploding, sulking, resting—all are as much a part of that process as the moments of clarity, inspiration, hope, vision, understanding, comprehension, connection, and joy. Those golden moments, when it all lights up, are wonderful pleasures, to be sure. The best way to experience more of them is to keep going.

Writers in it for the long haul understand this. Time teaches us all that if we hold out for the golden moments, we wait indefinitely, discarding days, weeks, months, years because the work didn’t present itself appealingly enough.

Mistakes happenAlong the way, not everything we do is going to work out well, or fit with the existing material, or make sense the next day. We goof. We err. We misspeak. We get lost. And that can lead to a sense of stuckness. To extricate ourselves, it can be helpful to recognize the mistake for what it is: another step in the process.

Golden moments happen

Mistakes aren’t a necessary evil. They aren’t evil at all. They are an inevitable consequence of doing something new.

—Ed Catmull and Amy Wallace in Creativity, Inc.

It’s not our job to wait around for the charmed instants when time stands still, and the angels sing. It’s our job to embody the truth that we’ll get more meaningful, deep satisfaction from our creative work by keeping at it. On the good days as well as the mediocre ones. On the days when we sneak in fifteen minutes of drafting a blog as well as the days when we devote four hours to the big project. On the days so hijacked by other things that no writing gets done at all.

Our mission, should we choose to accept it, is to keep going, to frame the writing life as a process, not a necklace of golden moments connected by chains of tedium or worse. It’s all part of the mix, and it’s all worthwhile. Somehow, changing the emphasis to general acceptance, rather than toleration, at best, of the not-fun parts, changes everything. We’re not assessing, comparing, or analyzing how each moment is going. Instead, we’re looking at the whole project from a higher altitude, taking in a broader view, and feeling less jumpy, more matter of fact about it all.

Allison K Williams in her must-have book Seven Drafts talks about this process using water metaphors—waves, rainfalls, and reservoirs. “By thinking about stories, reading widely in our genre, noting ideas on scraps of paper and in our phones, we fill a reservoir of creative energy. We can drink from this well of ideas when it’s not raining inspiration. … The most successful and published writers I know are not waiting around for the wave to lift them up; they’re carrying buckets every day.”

Squirrel moments happenFeeling stuck, I find with my clients, colleagues, and my own work, can be a problem of expectations. If we expect our writing life to feel welcoming and engaging all the time, then when it doesn’t the disappointment can morph into preemptive rejection: I’ll show you, you difficult project. Yeah, I’ll just leave you in the dust while I find another project that’s a lot nicer to me. Yeah.

That works, sometimes, for a while. I’ve done the half-complete-project sashay myself, over the years. Ooh: Squirrel!

Find a rhythm Bookshop • Amazon

Bookshop • AmazonYou know what feels better and lasts longer? Getting into an easygoing relationship with process. Not compulsively evaluating how it’s going, just knowing that a rhythm of regular—maybe daily, or nearly so—interaction with the project will ultimately result in some nice work. It won’t always be sparkly and magical. Those angel voices may quiet down to a low occasional hum. There may be some unmistakable squawks. The process will continue, and, from time to time, light up. The work will get done, with fewer sticking places and more ease.

My artist friend succeeded once she understood that she’d have to trust the process: Her talents, intelligence, and desire would get the project where it needed to go. It took that larger view for her to embrace the sometimes difficult day-to-day reality. At that golden moment when it all lit up, she understood, more than ever, that her trust had been honored. The process worked.

January 7, 2025

Should You Hire a Professional Designer for Your Book Interior?

Photo by Leslie Duarte Castro

Photo by Leslie Duarte CastroToday’s post is by freelance book designer Andrea Reider.

Many independent authors design and format their own books to save money. Working with a professional book designer for your print book interior can cost between $2.00 and $3.50 per page, and there’s no guarantee that a book will sell enough copies to earn back that fee.

However, some authors may have good reason to hire a professional to work on their book interior. Even if you decide to design and format your own book, I hope to make you aware of important elements of book composition.

A professional designer can select the best fonts and graphic elements to showcase your work. Book designers often draw inspiration from the book cover design elements and fonts for the interior. Most professionally designed books use the cover design font treatments for the half title and title interior pages and often for titles and subheads. Designers typically use two main fonts for most books unless there is a reason to include other fonts. The main text is almost always set in a serif font. Times New Roman is a common default for word-processed files, but professional designers rarely use it for books. Some commonly used fonts are Garamond, Minion, Sabon, and Caslon, but there are many other fonts that work well for the main text. Designers may use a sans serif font for chapter titles and subheads.

Most designers will offer several different designs as a starting point with various fonts and design treatments and then come to a final design after feedback from the author. A great book design can range from a typographic treatment without any graphic elements, to an elaborate design using several different design elements. Some effective designs use a repeating image—often a line drawing or simple graphic—on chapter and part opener pages.

A professional designer can help an author determine the best size for their book. Considerations include the topic of the book, the prospective audience, the desired page count, and the most readable type size. There are several standard different book sizes. The most common is 6″ x 9″ but many books are set at the slightly smaller 5.5″ x 8.5″ size. If an author wants a book to have a higher page count, the 5″ x 8″ size is sometimes the best choice. Books with a lot of photographs are often set at larger sizes such as 7″ x 10″ or 8″ x 10″. Workbooks are usually set at 8.5″ x 11″. All of these are standard sizes offered by most print-on-demand services, including Amazon/KDP, IngramSpark, and most print-on-demand and traditional printers.

A professional designer makes sure that your book is properly formatted and adheres to the best practices for typography and layout. Many decisions go into formatting a book, including fonts, proper hyphenation, line endings, and page breaks. Most nonfiction books have chapters that always begin on a right-hand page, whereas the chapter openers for fiction books usually can begin on either left-hand or right-hand pages as they fall. There are good reasons for these long-standing publishing traditions. One big reason is that right-hand chapter openers make it easier for readers to find the beginning of chapters. Another reason is that if there is a change to any chapter that adds or deletes a page, it doesn’t affect the left/right page orientation of the rest of the book. Another consideration in deciding whether to begin chapters on a new right-hand page is the number of chapters or pages in a book. If there are less than 20–30 chapters in a nonfiction book, it’s usually a good idea to start chapters on a right-hand page. If there are more than 30 chapters, publishers often choose to begin chapters left or right in order to avoid having too many blank pages in the book and adding unnecessarily to the page count and printing cost.

Books that have part openers pages often start the part openers on a right-hand page and then the following chapters right or left as they fall, with the first chapter after a part opener usually beginning on a right-hand page.

A professional designer frees up an author’s time to focus on other aspects of publication. Books that are mostly straight text are relatively simple to format using online tools, but books with multiple levels of subheads, extracts, footnotes, and other elements can be a challenge to properly format even for an experienced designer.

Too many books are published with charts and graphs that makes them look amateurish, unprofessional, and are often difficult for readers to understand. Well-designed charts and graphs can set a book apart from those that are done using just basic Microsoft Word functions or produced through online formatting tools. A professional designer will know how to set tabular information in a way that is easy for readers to follow, taking into consideration factors like hyphenation, line length, and aligning numerical text on the decimal point.

A professional book designer ensures the best placement of photographs and images in the book. There are many conventions for proper placements of photographs and images, including the placement and formatting of captions. Most photographs and images are placed at the bottom or top of the next available space after they are called out in the main text. Most nonfiction books will call out a figure in the text by figure number. Some images can be placed within the flow of the text, but it’s often not possible to do so. Determining the best placement requires experience and good layout judgment. Most of the online tools do an inadequate job of formatting pages with images or photographs, often leaving large blank spaces at the bottom of pages. A professional designer knows how to fill out every page in the book in the best way possible and will rarely leave short pages with unused space at the bottom unless there’s a good reason for doing so.

A professional book designer focuses on well-balanced pages. Online tools can produce uneven pages that aren’t balanced across page spreads. In a professionally formatted book, all page spreads are bottom aligned at the same point. Some pages may run one line shorter or longer than the typical page length, but a short page should never be followed by a long page or a long page followed by a short page. There also should never be more than two short or long pages in a row. These are the rules that have been followed by professional designers and typesetters for many years. It may not sound like a huge matter, but it’s one of the factors that go into making a professional-looking book.

A professional book designer pays attention to all page and line endings and breaks, setting each in the best possible manner. Professionals know many ways to finesse line and paragraphs endings and page breaks. A book that is set with bad or awkward endings and breaks can be annoying to readers and lead to a book being perceived as unprofessional and less credible. For good pagination, layouts should avoid widows and orphans, which are single lines appearing at the top or bottom of pages. Most books are set with hyphenation, which can be customized to specify the number of hyphens allowed (it’s best to set the hyphens for a maximum of two in a row with a minimum of three characters at the end or beginning of lines). Children’s and poetry books are usually set without any hyphenation. A professional book designer will know how to apply the rules, and in some cases, where to break or modify the rules to achieve the best possible layout.

A professional book designer can produce ebooks with advanced features. An ebook can look great on your computer screen, but appear terrible when uploaded to Amazon or other sites. Troubleshooting the errors can be a challenging process for even experienced ebook designers. Unfortunately, ebooks often end up looking like stripped-down versions of the print book because some of the features of print design don’t translate well to the ebook format. However, a good ebook designer can do many things to produce a better-looking ebook, including adding color to headings and subtitles and using color versions of any photos and images in the book.

A professional designer can help the author troubleshoot and fix any issues that arise when uploading files to the printer. All book printers, including Amazon and IngramSpark, require that files be formatted exactly to their specifications. It’s not uncommon for the printers to reject files for any number of reasons, sending cryptic error messages that can be difficult to interpret. Even files prepared by professional designers are sometimes rejected by printers for not exactly following their specifications. The issues are usually easily resolved, but for authors who format their own books, having their files rejected can be very frustrating and time-consuming.

While some authors can well format their own books, a professional can save you time and produce results that exceed the abilities of available online tools. As a professional book designer and formatter, I am honored to be able to use my skills to help authors produce attractive and readable books that enhance the reading experience and add credibility to their writing.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1885 followers