Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 30

September 17, 2024

My First Novel Was a New York Times Bestseller. I’m Self-Publishing My Third Novel Today.

Today’s post is by author Cynthia Swanson.

My debut psychological suspense novel, The Bookseller, sold to Harper in 2013 in a pre-empt. I’m not going to lie—it was an amazing deal. The type of deal that compelled me to ask my husband, when I called to break the news, “Are you sitting down?”

Amazon • Bookshop

Amazon • BookshopBy the time The Bookseller released in 2015, Harper had been throwing around the marketing and PR muscle that every author dreams of. They sent out hundreds of advance review copies. They got reviews in major trades, arranged interviews, pitched the book diligently to booksellers in hopes of seeing it make the Indie Next list (which it did), and ran strategically placed ads. For my part, I hired an outside publicist to help me with social media, because I knew exactly zero about building a platform. I cultivated a loyal following, particularly among book clubs. Librarians and booksellers wanted to get to know me—and with my foot in those doors, I fostered now-longstanding relationships with both groups. None of that turned me into a household name, but it was significantly more than a middle-aged, unknown author from Denver would have ever expected.

It also gave me a sense of having “made it.” By all appearances, I had. My agent sold international rights in eighteen countries. For a few glorious weeks, The Bookseller was on the New York Times bestseller list. Julia Roberts’s production company, Red Om, came calling, and I happily signed an option agreement.

Easy street, right?

Amazon • Bookshop

Amazon • BookshopWhile all that was going on, I confidently wrote my second novel, The Glass Forest. But by the time I finished it, my editor had retired from Harper. The editor who took over, more interested in publishing nonfiction than fiction, politely passed.

No worries—my agent took The Glass Forest out on wide sub, and I landed at Touchstone, an imprint of Simon & Schuster. Touchstone was full of smart, sophisticated people who did a fine job with The Glass Forest. It didn’t get the advance, nor the fanfare, that The Bookseller did, but it sold internationally in seven countries and hit the USA Today bestseller list.

I was still on my game. All was well.

Less than a year later, Touchstone announced they were closing their doors. Current Touchstone books were farmed out to other Simon & Schuster imprints—who had their own lists, of course. Unsurprisingly, The Glass Forest was nobody’s priority except mine.

Orphaned twice yet undaunted, I began writing another novel. A pandemic came along, and with it a godsend: the opportunity to edit a collection of stories set in my home city of Denver. Published by Akashic Books, part of their Noir series, Denver Noir was the best group project I ever did. It wasn’t going to launch me (or any of the other thirteen story contributors) into instant fame—but it was gratifying, uplifting, and a hell of a lot of fun to celebrate when we emerged in spring 2022 to promote the finished anthology.

All this time, I was writing my third novel, Anyone But Her. When my agent took it out on sub that summer, we received gracious passes. Lesson learned: despite my street cred, the novel wasn’t ready and shouldn’t have been on sub. I rewrote it, but my agent didn’t share my enthusiasm, and we parted ways.

Within a month, I landed a new agent, who loved the book. She took the rewritten Anyone But Her out on sub in summer 2023. But after an editor has passed on one version of your book, rarely can an agent go back to that editor with an all-new version. “Your previous agent’s list was comprised of many of the same editors I’d have sent the manuscript to,” my new agent said. “They won’t give it a second look, because that’s how the business works.”

Fine, no problem. There are lots of editors out there, and I had a solid reputation and good sales numbers. But again, the passes arrived. “While the writing is wonderful, I don’t see this as Cynthia’s breakout book,” was a common theme.

Herein lies a disconnect between what big publishers want and what many authors want. Most authors are thrilled simply to see their books in print, garnering respectable sales and a developing fan base. However, for a Big Five publisher or midsize house to consider your manuscript, they have to believe that major sales numbers are possible. Generally, this means you’re either a household name or a debut they’re willing to take a chance on, thinking you could be the Next Big Thing—knowing, of course, that for most authors things won’t click, but if they do for some, coupled with the household names, things even out.

Another option is to establish an ongoing relationship with a house or editor. This might not lead to big sales numbers, but if the house and editor know you and your work, often they’re willing to accept more modest sales projections for your books. For many such midlist authors, as long as their editor and/or house sticks around, they’ll likely be okay.

For me, however, that ship had sailed—twice. So, time to give up, right?

Nope. Time, instead, to hire the developmental editor I’d worked with on The Bookseller. A former agent herself, she has an impeccable editorial eye, and I trust her implicitly.

I asked her straight out, “Is this book publishable? Because if it is, I’m thinking about self-publishing it.” Her assessment resulted in a subtle yet important shift to the storyline. I made that shift and the novel is significantly stronger for it. So, I decided to forge a new path.

If you’re among the many authors out there looking for your next (or first) book deal—whether previously published or not, whether agented or not—where does this leave you? Certainly, writing the best book possible should be your top priority. But being realistic about your writing, your career—and the very good odds that at any point, things might go sideways—is also vital.

I’ve shelved fully written books in the past. I expect I’ll shelve others in the future. Sometimes, that’s the right thing to do. But sometimes, it’s not.

Sometimes, the right thing to do is trust your gut and just keep going.

Ironically (or maybe not), the entire premise of Anyone But Her—a mother-daughter story about grief, knowledge, and intuition—is learning to trust your gut. It’s a skill that can be lost in this business when authors feel the crush of self-doubt on a regular basis.

Amazon • Bookshop

Amazon • BookshopNot this time. I’m self-publishing Anyone But Her in ebook and print, and it releases today, September 17. My agent sold the audio rights, and an audiobook is forthcoming from Tantor Media. Advance reader and trade reviews have been great. My followers, fans, and book clubs who have been waiting years for a new novel are excited—and so am I.

This process has taught me lessons I’d never have learned if I’d landed on the easy street I anticipated when The Bookseller released. Become accustomed to expecting the unexpected. It’s essential that before you leap, you learn all you can. Be realistic. Run the numbers. Assess your risk tolerance. That goes for anything, really.

But in the end, you have to just do the thing. Might work out, might not. But if you never try, you’ll never know.

September 11, 2024

The 7 Habits of Highly Ineffective Writers: Powerful Lessons in Personal Sabotage

Photo by Nataliya Vaitkevich

Photo by Nataliya VaitkevichToday’s post is by author Joni B. Cole.

As a long-time workshop leader, I’m in awe of how some writers are masters at putting themselves on a path of creative self-destruction. In a way, it’s a beautiful, albeit demented, thing to behold—sort of like watching Glen Powell wrangling that F-5 tornado in Twisters. As a writer myself, I watch them and think, Wow. And I thought I was good at making myself miserable and getting in my own way.

What is it that makes these master self-saboteurs so good at what they do?

The question got me thinking about Stephen R. Covey’s book The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. The book has sold over 40 million copies and is still transforming the lives of everyone from presidents to parents. After revisiting that book, it occurred to me that highly effective people and highly ineffective writers have a lot in common. Indeed, I’d say they both share the same seven habits, except the latter applies all that initiative in the wrong direction.

What follows are examples of how highly ineffective writers manage to twist Covey’s seven habits for positive change into powerful lessons on personal sabotage.

Habit 1: Be proactive.In his book, Covey writes that highly effective people take responsibility for their choices. They don’t just sit around waiting for whatever befalls them. They make it a habit to act rather than react.

The same goes for highly ineffective writers. Master self-saboteurs preempt any potential criticism of their work by being the first to trash talk it. They don’t succumb to outsiders trying to influence or support them with feedback, instruction, brutal honesty, or praise. When it comes to personal sabotage, highly ineffective writers always make the first move, pooh poohing all routes to a more productive and positive writing life.

Habit 2: Begin with the end in mind.Imagine you are at your own funeral. What are people saying about you at your service? Covey says highly effective people decide how they want to be remembered—from their achievements to the values that guided their success. They then use those insights as the foundation for living a principle-centered life that helps them focus and flourish.

Highly ineffective writers also begin with the end in mind. Often, before they have even started their novels or memoirs, they fast forward to how all their efforts will likely play out:

Their book never sells because, let’s face it, unless you’re a celebrity or know someone, it’s next to impossible to land an agent or publisher, plus no one reads anymore anyway.Or, miracle of miracles, their book does get published, but then they’ll be expected to (ugh!) promote it, and the idea of having to hawk their work feels exhausting, nerve-wracking, and, frankly, beneath them. Indeed, just the thought of marketing their book makes them not even want to write it.Reviews! What’s the point of dedicating so much time and effort into publishing a book, just so a bunch of snobby critics and haters on Goodreads can trash their efforts for no good reason.Or, equally dismal, their book is a smashing success, which means they’ll be under relentless pressure to replicate that success. The highly ineffective writer takes a moment to imagine their own funeral. “I can’t think of anything more pathetic,” says one of the small handful of mourners in attendance, “than an author who turned out to be nothing more than a one-hit wonder.”Habit 3: Put first things first.Highly effective people act. Every day, they manage their time and make choices in a way that feeds their personal and professional life. They say “no” to the things that don’t match their principles and goals, and they prioritize the things that provide meaning and balance in the here and now.

Highly ineffective writers also make choices every day about where they spend their time and energy. First things first, they choose to start their days by texting all their writing friends to see if anyone else got up early to write. Then they check out a bunch of Instagram reels and go down that rabbit hole of celebrity StarTracks until finally, after they’ve finished clicking through a slideshow of fifty unforgettable looks at the Venice Film Festival, they are ready to work on that new chapter…except now it’s time to go to their day job.

And so goes another morning, another week, another weekend. For the highly ineffective writer, every day is a race against the clock to say “yes” to as many things as possible—social media, rearranging the photos on the mantle, volunteering wherever they are needed. The highly ineffective writer is a master of prioritizing anything that is not writing.

Habit 4: Think win-win.Forget about winners and losers. Highly effective people see life as a cooperative, not a competition. When interacting with others, their goal is to seek a mutually beneficial agreement or solution—a win-win where both parties feel satisfied with the outcome.

Highly ineffective writers go a step further with this mindset. They think in terms of win-win-win, which means when they sit down to write, they hope to satisfy three parties. Naturally, they want to fulfill their own creative goals; for example, to write a memoir about their childhood growing up on a small farm in Iowa. But they also want to make sure the people who appear in their story are happy, including their five sisters who read an early draft of their manuscript and all agreed, “That’s not how it really happened!” And lastly, they feel the need to accommodate the members of their writing group, one of whom offered this feedback: “No one is going to want to read about someone’s boring childhood on a smelly family farm in the middle of nowhere.”

With this kind of win-win-win philosophy, the highly ineffective writer sets out to revise in a way that will provide a satisfactory outcome for, well, for pretty much everyone they know.

Habit 5: Seek first to understand and then to be understood.Listening. It’s a tricky skill because lots of people, even if they do allow room for others to talk, only listen enough to figure out what they want to say in return. Whereas a highly effective person makes it a habit to actively and empathetically listen before communicating their own views. They listen with the intent to understand.

Similarly, the highly ineffective writer understands exactly what someone is saying, mostly because they actively put words in the other person’s mouth.

What is said: “I think the opening of your story would benefit from some trimming.”

What is understood: “Burn your entire manuscript.”

Said: “Your novel was a delight.”

Understood: “I’m just being nice so you’ll leave me alone.”

Said: “Thank you for your powerful submission. Unfortunately, your novel is not a good fit for our press.”

Understood: “We hated your novel and we hate you, too.”

The synergize habit is like habit 4 (Think win-win)—only on steroids. Highly effective people look for opportunities in all aspects of their life to unleash the power of collaboration; to create outcomes greater than the sum of their parts.

Given that writing, for the most part, is a solitary act, how does the highly ineffective writer practice a habit that involves teamwork, unity, and the type of math where one plus one equals three? The answer lies deep in their psyche.

Residing within the mind of the master self-saboteur is a quartet of collaborators—the creator, the editor, the critic, and the stan. Every time the highly ineffective writer sits down to write, these other team members unleash a torrent of opinions:

“Generate! Generate! Generate!” the creator insists.

“I don’t care if you’ve only written a few paragraphs,” the editor interrupts, “those passive verbs aren’t going to rewrite themselves!”

Meanwhile, the critic at this mental gathering doesn’t say a word because the musk of his disdain already communicates volumes. And the stan, bless his little heart, keeps piping in, “Your writing is perfect. Don’t change a thing!”

“Synergize! Synergize! Synergize!” the highly ineffective writer intones, while rocking back and forth, squeezing their head. But how can they make the whole greater than the sum of its parts when nothing they write ever seems to add up to anything?

Habit 7: Sharpen the saw.We can all lose our edge from time to time, which is why highly effective people follow a balanced program of self-renewal in four areas of life: physical, social/emotional, mental, and spiritual. They regularly and consistently “sharpen the saw,” so to speak, to create growth and ongoing positive change.

The highly ineffective writer also sets goals in service to self-renewal, often to extremes:

Run a marathon.Greet every sunrise with a sense of awe.Help save a bunch of endangered species. And, most importantly, write, write, write! Every. Single. Day!And therein lies the final lesson in personal sabotage. Because while highly effective people seek a balanced program of self-improvement to renew their edge, highly ineffective writers are determined to make their saws so sharp they inevitably drive themselves right over the edge.

September 10, 2024

Spontaneous Generation and Author Platform

Today’s post is by historian, podcaster and writer Doug Sofer, Ph.D.

This is a little embarrassing. I’m a historian who values logic and evidence, but sometimes I can’t help but believe in a little bit of magic—especially when it comes to building an author platform.

Maybe you’ve felt the same way. Platform-building is full of mysteries that can make even the most rational person start to wonder about magical solutions. Questions like, “What’s my brand?” “Which social media should I use?” “How do I grow my audience?” are just the start. To me, building a platform feels like trying to create something out of nothing. On one hand, we’re told that we need a large audience to get published. On the other hand, we need to get published to build that audience. How do you attract readers if you haven’t yet established yourself? And how do you establish yourself without readers?

It feels like spontaneous generation: the old belief that life could just appear from lifeless matter. For most of history, people thought that living critters—little ones especially—could just materialize into being. It wasn’t until the 17th century that Francesco Redi, an early scientist, began to challenge this idea. He showed that if you kept flies away from rotting meat, no maggots would appear.

Even after Redi’s experiments, belief in spontaneous generation persisted for centuries. In fact, even Redi himself didn’t entirely give up on the idea. While he was disproving spontaneous generation for flies, he still believed in it for other invertebrates. He speculated that plants and animals had some mysterious force within them that could create life. Roundworms might generate inside intestines, or suddenly you’d just be lousy with lice even when there hadn’t been a single other louse in the house. The reason he didn’t just abandon spontaneous generation altogether is that the life cycles of some parasites can be extremely complicated. Without today’s powerful scientific tools, at some point Redi threw up his hands and called it all sorcery.

My big takeaway is that even Redi, one of the people famous for having refuted spontaneous generation, still hedged his bets when reality got too complex. It wasn’t his fault. Settling the question required centuries of additional scientific research, debate, and technological advancements. Only in the 19th century did Louis Pasteur’s work with bacteria finally prove that life doesn’t just hocus-pocus out of thin air.

This whole story is like my own struggles with platform-building. Like Redi, I start thinking magically when things start to feel too complicated. For example, I’ll catch myself believing in stories of spontaneous, overnight success. We’ve all heard about someone’s blog or YouTube channel suddenly going viral. Those are great stories, but they create the false impression that you can build an enormous audience through simple luck. And once I start thinking that way, I start gluing horseshoes to my laptop.

Fortunately, there are some present-day Redis and Pasteurs working out the nonmagical origins of getting lucky. Data scientists have shown that what feels like luck is really the result of consistent work and smart decision making. Consider what Seth Stephens-Davidowitz describes as “Springsteen’s Rule” in his book, Don’t Trust Your Gut. Bruce Springsteen didn’t just rely on talent; he shared his music far and wide, moving his hungry heart out of his hometown in order to increase his chances of being noticed. It’s an example of “hacking” one’s luck and it’s based on Samuel Fraiberger’s research about artists’ success. The ones who flourished took their art shows on the road, traveling to many different galleries of many different kinds. So yes, luck matters—but we can make it work for us through evidence-informed strategy.

And successful authors do much more than simply hack their luck. They also get advice from people with actual, real-world experience in building these kinds of readerships. There are some incredibly helpful resources out there—Jane Friedman’s blog here is definitely one of them. I recently took Allison K Williams’ and Jane’s enlightening Zero-To-Platform Bootcamp webinar, which helped me gain some much-needed perspective. I learned that successful platforms take persistence, patience, and probably a couple of years to build. And that’s okay.

The process is about knowing yourself, what you have to offer, and understanding who will benefit from having your words in their lives. It’s about communicating with your specific population of readers and finding ways to engage meaningfully with them. It requires knowing what kinds of books have been written already, and where there are opportunities to find an appropriate niche for you in the marketplace. Success usually requires a lot more than just being good or lucky. It takes time, persistence, and strategy.

The history of spontaneous generation also shows us that filtering truth out of complex, interconnected variables requires experimentation. On this front, I’ve found the advice from literary agent Max Sinsheimer’s YouTube presentation especially useful. He urges authors to think of the publishing process as an ongoing research project that constantly evolves. That approach makes sense to me because building a rep as a writer is just as complicated as the life cycles of the creepiest and crawliest creepy-crawlies out there. Readers, like other large groups of humans, seem to be as unpredictable as any of the parasites that confounded Francesco Redi.

So I’ll try to cut myself some slack when I start feeling like the whole process is just a bunch of sorcery. When I catch myself riding my broom off to Hogwarts, I just try to return the land of muggles as quickly as I can. If understanding platform-building is ongoing, maybe the real trick is to treat it like a continuing journey and do our best to enjoy the ride. Just like Redi’s quest for truth, it’s about experimenting more, learning, adapting. For my part, it’s also about staying patient and pursuing my aims methodically, instead of wishing for a platform to conjure itself into existence.

September 4, 2024

The Secret Sauce for Writers: Intuition

Today’s post is by author KimBoo York.

What is intuition?

Specifically, what is creative intuition for writers?

The dictionary definition for “intuition” usually goes something like this: “the ability to understand something instinctively, without the need for conscious reasoning.”

But that does not lend itself it trustworthiness. If you can’t provide conscious reasoning for your understanding, do you understand it at all? Or is it a timing issue: you understand something before you can explain it? But then is that not just akin to justification?

As someone who often could answer a complex math problem as a kid but could not for the life of me memorize multiplication tables, intuition has not been my friend, historically speaking. Instead it was the thing that got me in trouble, even with my creative writing.

“Why is this character climbing up the mountain to talk to the old witch?” Dunno, feels right, I guess?

It took a long time for me to realize that I was not the problem. Becca Syme in her book Dear Writer: Are You Intuitive? describes intuition as a form of pattern recognition. It’s not a “gut feeling,” as it is so often described. In fact, it is not a feeling at all. It is your brain connecting dots so quickly that you are not aware of the connections until you look backward to figure out why you know what you know, or did what you did.

I think that is a good start for a definition of creative intuition, and I highly recommend that book for all writers, but I knew there was more to it.

When I was recording a recent episode of Around the Writer’s Table podcast, my co-hosts asked me what my definition of intuition is. I intuitively answered: “It is the combination of experience and imagination.”

I want to stress that experience isn’t just about how many books you’ve read or how long you’ve been writing. It’s about the depth of your engagement with stories, both as a reader and a writer. It’s about understanding narrative structures, character arcs, pacing, dialogue, and all the other elements that make up a good story. It’s about knowing the rules so well that you can break them effectively.

Imagination, meanwhile, is your unique perspective, your ability to make unexpected connections, to see the world in a way no one else does. It’s what allows you to take familiar concepts and combine them in new and exciting ways.

When these two elements come together, that’s when the magic, aka intuition, happens. That’s when you write a scene that surprises even you, or when you suddenly understand your character’s motivations in a way you never did before.

Intuition in practiceIn my post What Is the Worst that Could Happen? I discuss how discovery writers can get ourselves out of a jam by imagining not what should happen next but the absolutely worst thing that could happen next. As an example, I used the tired old trope of a knight rescuing a princess/prince/princette from a dragon.

Our experience as readers and students of literature/writing tells us what is going on: the knight has ridden his warhorse up to the dragon’s lair to rescue the fair maiden princess from certain doom.

Creative intuition is knowing the trope (experience) and then subverting it or using it in an unexpected way (imagination).

Admittedly, subverting that trope is fairly easy and at this point has been done a lot (mix up the genders, turn the dragon into the hero and the knight into the villain, make the dragon and the knight friends, give the princess the agency to save herself, etc.). But that’s part of our intuition as well. Anyone who has been reading modern fairytale retellings will know what has been done, what has worked, and what hasn’t worked (and why). They have experience with that trope, which pushes their creativity even further out into unexpected territory.

In other words, experience counts and uninformed “intuition” is just guesswork.

This is why you hear me saying a lot that intuition (and discovery writing) can be developed, and that studying the craft of writing is critical. As writers, we must read widely as well as study our genre of choice; we must engage in critical analysis of texts; we must put in the time to improve our craft.

But knowledge alone does not create amazing stories. At some point, we have to learn to trust our intuition by allowing our imagination to engage with our experience.

Developing your creative intuitionSo how can we develop this connection between experience and imagination? Here are a few ideas:

Read widely and deeply: Don’t just stick to your favorite genre. Read classics, contemporary works, experimental fiction, nonfiction. Analyze what works and what doesn’t in each book you read.Write regularly: Like any skill, writing improves with practice. The more you write, the more you’ll develop your intuitive sense of story. No, you don’t have to write every day, but you need to take time on the regular to practice your craft.Experiment: Try writing in different genres, styles, or points of view. This stretches your imagination and expands your experience.Analyze your own work: After you’ve finished a piece, take some time to reflect on why you made certain choices. This helps you understand your own intuitive process. I re-read my own work a lot to consider how I could do things differently, what worked, what didn’t. Every time I read an older story, I learn something new about my own process.Engage with other writers: Discuss craft, share work, give and receive feedback. This exposes you to different perspectives and approaches. (You could also listen to my podcasts!)Study craft: Read books on writing, attend workshops, watch lectures. The more you understand about the mechanics of good writing, the more your intuition has to work with.Live life: Experience is not just about books. Travel, meet new people, try new things. All of those experiences feed into your creativity!Trusting your intuitionDeveloping your creative intuition is one thing; trusting it is another. Many writers, especially those just starting out, second-guess their intuitive choices. They worry that if they can’t explain why they made a certain decision, it must be wrong.

But remember, intuition is about pattern recognition happening faster than your conscious mind can process. Just because you can’t immediately explain why something feels right doesn’t mean it’s wrong.

That said, intuition isn’t infallible. It’s a tool, not a magic wand. Sometimes your intuition will lead you astray, and that’s okay. That’s part of the process. The key is to strike a balance between trusting your intuition and being willing to revise and rethink when necessary.

In the end, creative intuition is about developing a deep, almost subconscious understanding of storytelling. It’s about internalizing the rules and conventions of writing so thoroughly that you can play with them fearlessly. It’s about trusting yourself to make bold choices, even when you can’t immediately justify them.

Next time you’re writing and you make a choice that you can’t quite explain, don’t immediately dismiss it. Take a moment to explore it. You might just find that your intuition has led you somewhere amazing!

September 3, 2024

Co-Authoring: How to Keep the Drama On the Page

Photo by Simon Bobsien

Photo by Simon BobsienToday’s post is by author Midge Raymond.

While collaborative writing is common in many fields—science and academia, for example—it’s less common among creative writers, especially fiction writers. Yet I’ve noticed over the years that many novels are co-written, and I’ve always wondered how, exactly, that process worked—until I found myself co-writing a novel with my husband.

When John and I traveled to Australia several years ago, we embarked on a four-day hiking/camping trip to a remote island off the coast of Tasmania with three other couples, most of us strangers to one another. At one point, after learning we were both writers, our companions joked about whether we would one day write about them—and of course, we joked back that we probably would.

Then, John actually did get an idea: The location of this journey (middle of nowhere), the setting (isolated and surrounded by wild animals), and the history (the island was a former convict settlement that now plays a major role in preserving the endangered Tasmanian devils) would be a great setting for a suspense novel. Though we’re each individually published writers, we share the same passion for the environment and have read nearly every word of each other’s work anyway—so we decided to write this book together.

Not every couple can write together—but on the other hand, it can be a natural turn of events when shared ideas happen. For Graeme Simsion (The Rosie Project) and Anne Buist (Locked Ward), married for decades and both successful individual writers, their first collaboration, Two Steps Forward, was inspired by walking the Camino de Santiago together. For Charlene Ball and Libby Ware, married writers whose co-authored mystery novels are published under the name Lily Charles, their first collaboration came to them “after saying to each other several times: ‘We really should set a mystery at the Florida Antiquarian Book Fair.’”

A spark of an idea can lead to wonderful things for co-authors—but whether your writing partner is your spouse, best friend, or a colleague, you do have to proceed with caution. Here are a few tips.

Know when to join forces—and when not toHaving a shared idea may seem to lead naturally to collaborative writing—but this is not always the case. You’ll want to be sure that you and your collaborator are on the same page, so to speak, from the beginning. Before diving into the first chapter, have a conversation about expectations and the collaborative process. What unique skills do you each bring to the project—and how do you choose who tackles which tasks? How do you define success as a team (finishing the book, getting it published, self-publishing)? And, most important, how will you plan to deal with conflict and disagreements?

Ball and Ware caution, “You need to be committed to the joint process from the beginning and to realize that it’s different from writing on your own. When your writing partner suggests a change or wants to take out something you wrote and like, you can either give your reasons for why what you wrote is right for that scene, or you can give it up gracefully, or you can propose a compromise.”

Commitment to both the project and the relationship goes a long way. Buist says of disagreements when writing with Simsion, “We’ve not really had any that a discussion couldn’t fix”—to which Simsion adds, “I just let her win”—to which Buist adds, “No, I give in.” In short, it’s all about good humor and compromise, and you’ll need to be sure you’re both willing to bend if and when you need to.

And if you—or your potential co-author—are accustomed to (or prefer) writing solo, or if you have unwavering beliefs about any aspect of the writing or getting-published process (for example, disagreements over what you want in an agent or an unwillingness to self-publish), you may not be good candidates for collaboration.

Divide and conquerWhen you have a shared idea, be sure you’re also prepared to share the work. And keep in mind that, depending on your goals, the work means not only writing but could also mean outlining, research, querying agents, editing, promotion, and myriad other aspects of the writing and publication process.

Sometimes these divisions of labor come naturally. Of Simsion and Buist, for example, Simsion is more of a planner and uses index cards for a book’s outline. “I tend to drive the process in terms of what we’re doing at any particular time,” he says, “but we are equal partners in what goes on those cards.”

In our case, John is great at plot, theme, and seeing the big picture of a story; I’m more scene-focused and detail-oriented. So while we did the early brainstorming together, he ran with the characters and plot for a while and sketched an outline; then we’d do more brainstorming. Next, he’d write a chapter that was fairly skeletal, and I’d flesh it out with details about the setting, characters, and story, which we’d both figured out together.

Ball and Ware have a similar process: One of them writes a chapter, then emails it to her wife, who then “edits and amplifies it, then writes the next chapter and emails it back.” This worked well for their first mystery, until Ball locked one of the characters in a basement with a dead body and no way out. “After that, we decided to plan together what was going to happen next.”

Though they share the writing, Ball feels more connected with the character of Emma in their bibliomystery series, while Ware identifies more with Molly—and for many writers, having two main protagonists can lead to a natural division of labor. For their books Two Steps Forward and Two Steps Onward, Simsion and Buist each took on a character, with Simsion writing the character of Martin and Buist writing Zoe—then Buist would edit Zoe’s words in Martin’s chapters and Simsion would edit Martin’s words in Zoe’s chapters. However, in their third collaboration, The Glass House, for which the story relies upon Buist’s thirty-five years of expertise in the psychiatric field, Buist wrote most of the novel, followed by a “very long editing process” with their publisher. “The patient stories were left to my experience,” Buist says, “but Graeme then molded them into a story that had an arc within the chapter.”

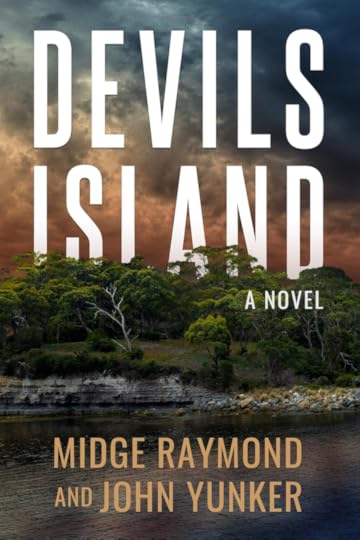

Even after the writing is done, collaborators will need to consider how to handle editing—including with agents and publishers—as well as how to divide publication and promotion tasks. In our case, I happily handled the revision and review of copyedits for Devils Island, since John isn’t as detail-oriented and it’s the kind of thing I enjoy. In turn, being technically skilled (where I decidedly am not), John created our website.

Ball and Ware similarly divide post-writing tasks, with Ware taking charge of social media and Ball focusing on other promotional opportunities—and Simsion and Buist play to their individual strengths as well. “Graeme tends to handle the business and organizational side,” Buist says. “But we do the interviews, talks, and signings together.”

Put the relationship firstWhether you’re friends, colleagues, or a couple, part of successful collaboration is being willing to put the relationship first. This can mean anything from agreeing to compromise to recognizing when to quit if the collaboration or project isn’t working out. You’ll want to be sure you’re able to quit a project without worrying about quitting the relationship.

For collaborators who are acquaintances or colleagues, having a written contract might be the best way to develop and define expectations, deadlines, and exit strategies. This need not be a formal agreement drafted by the writers’ attorneys but rather a list or outline that, simply by being written down, clarifies goals and expectations.

For close friends or partners, the process is usually pretty informal. John and I, for example, didn’t think of any of the potential pitfalls until they were upon us—yet we were both enthusiastic enough about the project (and, fortunately, committed enough to our marriage) to keep moving forward.

When it comes to preserving a relationship, the process of critique can be a delicate one. Buist suggests, “Work out in advance how to deliver feedback.” This is especially important if you’re in a close relationship; as Simsion says, “We’re not as kind as we might be to someone at arm’s length. Recognize that you’re on the same side and that the relationship is more important than the book.”

Having a sense of humor helps, too. John always laughs off my (good-natured) complaints of him creating four characters who have the same name, or when he inadvertently changes characters’ careers or hair colors during the course of the book. Knowing your strengths—and especially knowing your weaknesses—makes it easier to come to agreement, whether it’s about the project or the process. Speaking of agreeing—when Buist says the biggest challenge of writing together is “Graeme criticizing my vomit draft,” Simsion confirms that his biggest challenge is “trying to fix Anne’s vomit draft.” If you know what the challenging parts will be and how you’ll react to them, getting through to the other side is that much easier.

Enjoy the journeyAt the end of the day, writers collaborate because it’s fun. For Simsion and Buist, the writing process usually begins with a bottle of wine. “We leave the day behind and relax,” Buist says. “It’s a time we can be creative but also communicate well. It’s ideal for story outlining, exploring themes, and nutting out problems.”

And while the wine time is relaxing, it’s also part of “an ongoing practice,” says Simsion. “It also means we keep talking to each other about the book, which is important to stop us going off in different directions.”

Amazon • Bookshop

Amazon • BookshopWriting together, Simsion says, has been good for their marriage. “I think that having something you enjoy doing together, making plans around it, actually doing it and, as a bonus, getting affirmation for doing it, is good—maybe even essential—for a marriage.”

Ball and Ware agree. “It has added a common interest that we enjoy talking about even when we’re not officially writing or deciding on what should happen next. And it’s fun.”

As for John and me, we wrote a second novel together and are working on a third. We hold important writerly meetings during happy hour, and are planning a book tour during which we’ll fit in some family and friend reunions. Writing, selling, and promoting a book is hard work, to be sure, but doing it together can help divide the workload and double the joys.

August 28, 2024

Publishing Advice from a Serial Submitter to Literary Magazines

Today’s post is by author Amy L. Bernstein.

Over the last several years, I’ve spent oodles of time submitting short stories, essays, poetry, and novels to literary magazines, contests, and publishers. We’re talking scores of hours devoted to searching, formatting, and submitting my stuff directly to the publishing gods (I’m excluding agents).

This is where I tell you that all that effort paid off, and I have a ton of author bylines to show for it.

But no. The truth is, roughly 99% of my submissions are rejected.

Does that mean I’m a terrible writer? Not necessarily. My odds just about track industry averages. Indeed, the 1% acceptance rule is fairly consistent, whether you’re submitting short fiction or a novel. And memoir is arguably the toughest sell of all.

There’s a disconnect here somewhere, isn’t there? If the odds are so stacked against the average author, why bother submitting anywhere, ever? Why not go out and buy a pack of lottery tickets instead?

Well, it’s simple, really. Unless you plan to self-publish everything you write, you have no choice but to give editors and/or guest judges a chance to evaluate your work on its merits.

If you don’t play, you can’t win.

And if you are allergic to competing, then maybe getting published isn’t for you.

What I do have to show for all the time I’ve spent submitting is a checklist to help authors manage the submission process in ways that mitigate “bright shiny object” syndrome, so you don’t submit to anything and everything that crosses your path. The outcome is never in your control—so you may as well do whatever you can to make the process work for you to the greatest extent possible.

I’m focusing here on short stories, novelettes (under 20,000 words), novellas (under 40,000 words), poetry, and (to a more limited extent) creative nonfiction, such as essays. For advice on submitting book manuscripts to traditional publishers, see this set of articles.

1. Devise a submission strategy that reflects your goalsBefore submitting anything you’ve written (and polished!), think hard about what you hope to achieve on behalf of your writing career. That will help you narrow the submitting field as you seek out publications that will potentially showcase your work in ways that matter to you most. Simply getting published is not always an end in itself; where you publish, the formatting and distribution, the gatekeeping—these all matter in shaping your credentials as an author over time.

The company you keepWhat literary company do you wish to keep? The New Yorker only accepts 0.14% of unsolicited submissions, while other publications accept half or more of submitted work. Are you aiming for an elite literary outlet from the get-go (and willing to wait for it) or are you willing to climb the literary latter, beginning with less prestigious outlets in order to build publishing credentials from there? Do you want to “play” in an international literary community, or is the U.S. just fine?

These aren’t trick questions and there is no single right way to do this. But your submission strategy will feel less random, and possibly even less fraught, if you can rationalize your reasons for submitting as an ongoing part of the process.

For instance, if short stories are your chosen métier, and you wish to become known for that—with an eye toward getting a book published—you’ll want to identify the best outlets for short stories, and continue submitting your very best work to better and better outlets. That puts a big fence around your submission universe. And as your track record improves (you move from lesser known to better known outlets, presumably as your writing improves), editors may pay closer attention to your submission, giving you a tiny edge. (This is by no means guaranteed, but your publishing history counts for something.)

By the way: If you’re wondering how to distinguish the elite (most selective) publications from the rest, there is no single source, but many reliable lists point the way, such as this and this.

Formatting and distributionSome publications are digital-only, while others produce both online and print versions that you (and others) can order through the publisher’s website. Some are distributed by major book distributors like Baker & Taylor, which means libraries and bookstores may stock them. Some literary journals take tremendous care to surround print work with original art, while others do little more than post text and slap on a table of contents. Think about how you want your work to show up—and where—before you submit.

The recognition factorSome literary publications annually submit their best pieces (as determined by the editors) for prizes such as the Pushcart Prize and the O. Henry Prize. If being eligible to compete for this type of recognition is important to you, then check to see whether the publication you’re submitting to does this on half of their contributors. Many do not.

2. Study the fitThe most common mistake submitting writers make—and a huge source of rejection—is the lack of fit between your literary offering and the publication. Note that a huge distinguishing factor among literary publications is the voice they prefer, and whether that voice is genre-dependent or even values-dependent. Be sure you understand this before you submit. For instance, make sure you’re intentional when submitting to a queer literary publication, or a left-leaning culture magazine like Drift, or any other outlet with a specific set of interests. Read several published pieces online before submitting, to make sure your voice is a likely fit.

Likewise, tailor your genre-heavy work to outlets steeped in that genre, ranging from, say, Nightmare Magazine (horror) to Clarkesworld for short science fiction. As obvious as this sounds, writers too often overlook a publication’s milieu—and end up submitting work that isn’t remotely a fit.

3. Follow the publisher’s directions—exactlyAnother major reason for rejection can be traced to a failure to follow directions. Read the directions two or three times before submitting. I often copy the submittal guidance onto a Word file, so I can consult it while gathering pieces (such as a hyper-short bio) or reformatting my document (e.g., separate title page, double-spaced, name in the upper-right corner). If they explicitly state that they don’t want stories over 5,000 words, do not submit your 7,500-word piece and hope for the best.

Frankly, prepping a submission can be a time-consuming pain in the neck. But if you wish to be taken seriously—and evaluated on the strength of your writing—then do exactly as requested. And keep in mind you have a choice here: If the directions are particularly onerous, ask yourself if this is a strategically important outlet for you—and therefore worth your time.

Poetry can be especially tricky. The lines are often single-spaced (not double) and the line and stanza breaks need to be crystal clear. If a poetry outlet accepts a PDF, that will ensure your line structure is preserved.

4. Track open-submission windowsIn a perfect world, every literary magazine would accept work at identical intervals and respond to authors within the same, reasonable timeframe (less than a year!). But that’s not our world. As part of your submission strategy, use your calendar or task list to note when the submission window opens and closes for a publication you are targeting. Some submission periods run the length of a season, some are open for only a few days.

To find who’s open when, search sites such as Submittable, Chill Subs, the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses (CLMP), Authors Publish, and the fee-based Duotrope.

5. Build a relationship with publications accepting your workRather than celebrating a one-and-done when your story or poem is accepted, consider ways to deepen your relationship with that publisher. A number of literary journals also function as presses that accept book-length manuscripts. (A case in point is Able Muse.) And many run paying contests in addition to their general open-submission periods. Begin a conversation with the editor who accepted your work. Express your gratitude and explore what else they may be open to from you. Strike while the iron is hot! (Here’s some inspiration along those lines.)

6. Keep rejection in perspectiveSubmission and rejection are opposite sides of the same coin. You can’t have one without the other. But you can possibly affect your odds, even just a little, by crafting a clear strategy for where you submit, and why. If an outlet that rejects you is important to you, resubmit in a few months (I’ve done that, and it worked!).

Never forget that this is a terrifically subjective business. An editor who rejects your work has many reasons to do so—and not all of them reflect on the quality of your writing. Many publications received hundreds, if not thousands, of submissions and their publishing quotas for a given issue fill up fast.

In some cases, the editors are looking for a range of subject-matter, and perhaps you’ve submitted something that’s too similar to a piece they’ve already accepted.

If you continue striking out after months of effort, it may be time to revisit your submission strategy:

Seek out publications that are less selective (this doesn’t mean bad!).Double down on assessing where your work fits best, in terms of voice and genre.Look for regional outlets that privilege work from your geographic area.And subject your work to an independent editor who can give you a professional opinion on whether you’re ready to publish.The good news is that despite all the challenges facing the publishing industry today, literary magazines of all stripes are alive and well—hundreds of them, catering to virtually every taste and style.

With a thoughtful, realistic submission strategy, you will find the publications ready to share your work with the world and help you parlay your successes into a satisfying career.

August 27, 2024

Crowdfunding for Writers Who Need First-Time Guidance

Photo by Andrea Jaeckel-Dobschat on Unsplash

Photo by Andrea Jaeckel-Dobschat on UnsplashToday’s post is by writer Jason Brick.

The model we’ve come to call crowdfunding has always existed in the form of pre-sales or (in publishing) pre-orders. With pre-sales, a company or individual pitches an idea to likely early adopters. Those who get excited enough buy one in advance, providing some of the money needed to make the product a reality.

Kickstarter made this easier and more accessible by combining the concept with key components of social media. They gave creators—of books, technology, art, or whatever—a platform for presales. That platform handled the transactions, gave the campaign a home page, and provided social infrastructure to help a project gain followers and momentum. It filled a hole in the modern market, and was successful enough to get cloned. Over a hundred crowdfunding platforms exist today, but the overwhelming share of that market belongs to just four. More on that in a bit.

Authors and publishers alike can use crowdfunding to provide the cash needed to produce, promote, and distribute our books at a level that wasn’t possible twenty years ago. Kickstarter and its clones provide the simplest route for authors to fund new books. A successful campaign gives you the money to hire professionals for editing, layout, design, art, and other skills that aren’t in your bailiwick. It creates initial buzz you can leverage for further sales after the campaign has closed. It can produce enough profit to rival advances from some publishing houses.

In short, it makes self-publishing success even more possible by authors who don’t want to deal with the slow timeframe and low royalties of working with a traditional publisher.

What’s new in crowdfunding?The newest crowdfunding platform is ten years old. Crowdfunding is established, and produces about 2 billion dollars in revenue for publishers and journalists annually. In 2020, Brandon Sanderson raised over 40 million dollars with a single campaign. It’s old news. Or is it?

Over the past five years, the crowdfunding scene has seen some major changes that will impact how to succeed if you start crowdfunding your work.

It’s no longer fringeNot too long ago, crowdfunding was the realm of scrappy, independent underdogs making cool stuff happen where traditional publishers were too slow or stodgy to get things done. That was even more true of technology innovations and some really interesting art projects. It was the realm of interesting people doing interesting things, forming tribes of people with similar passions.

Over the past five years, more and more established companies have used crowdfunding for market research, initial cash infusion, and to defray the risk of testing new products. It’s not a fringe operation, but an established business model. A level down the “food chain,” independent crowdfunded publishing projects are still common.

What That Means: The market is saturated on several levels. Your crowdfunded book is not unusual. It’s one of two to three everybody sees on their Facebook feed every day. Among those who see it and are interested, you’re not competing with just other independent authors. You’re also up against professional small presses, who can outspend you on publicity, advertising, and production value.What to Do About It: This doesn’t mean your book can’t succeed in crowdfunding. It does mean you have to come at it in an organized and professional fashion. The days where you can succeed on the basis of an idea are gone. You need a plan, and you need a budget. We’ll talk more about both later on.The rise of PatreonPatreon took a new angle by combining Kickstarter’s idea with something from the Renaissance: patronage. Way back when, it was fashionable for royalty and wealthy merchants to fund artists and their work. Patreon takes a social approach to this. Instead of a single patron providing a lot of money, they provide a platform where creators can get a lot of people to each support them with a little money. With enough followers it can end up being a sizeable income.

The top five writers on Patreon make a minimum of $35,000 per month just off of their account, plus whatever they make from Amazon, speaking appearances, and similar adjunct earnings. The average Patreon account makes between $300 and $1,600 per month. That’s not quit your job money, but it is about twice what the average KDP author pulls in.

What This Means: There’s a potential new model of crowdfunding success for authors. It’s old enough to be proven and to have built up some community, and new enough you won’t be competing with enterprise-level marketing budgets with full-time staff.What to Do About It: First, consider whether or not you’re the kind of writer who can produce new work reliably on a schedule. If not, “traditional” crowdfunding is a better path for you. If you are that consistent writer, decide whether or not you want to learn the new skillset needed for Patreon success. If the answer to both questions is yes, it might be worth giving a try. I’ve recently started a Patreon account to support my flash fiction magazine. It’s early days yet, and I’m still learning. But if you have some fiction at under 1,000 words, I invite you to check us out and submit.Professional crowdfundersI already mentioned that full-time small presses are crowdfunding as their core business model. Besides them, there is an ecosystem of professional crowdfunders who will manage campaigns, coach authors, and generally provide skills and experience most independent authors never had a chance to gain.

What That Means: Success with crowdfunding doesn’t require professional-level training and funding. It does require a basic understanding of what works, and what doesn’t, when you run a campaign. People who try to wing it, even in a way that would have done well in 2016, are unlikely to succeed.What to Do About It: Before starting your first crowdfunding attempt, learn about the field. If you ever pitched an agent, your first step was learning how to pitch an agent. Crowdfunding is no longer any different.BackerKit: new playerIf I’d written this article even a year ago, my advice would be to use Kickstarter. It’s the Coke and Kleenex of the crowdfunding world. It’s Facebook: where the most people hang out, whether or not they love it. Kickstarter’s platform and infrastructure simply provided an insurmountable advantage. That’s still true, however…

BackerKit spent the first decade of its existence helping people with successful crowdsourcing campaigns organize and manage their fulfillment. They provided order tracking, billing, and communication, and would outsource your entire shipping chain if you paid them.

In 2022, they launched their own crowdfunding platform as well. After ten years of watching what Kickstarter did well (and poorly), they set out to provide a better option. In my opinion, they succeeded in terms of support. They don’t have the crowd size yet, but are poised to do so.

What That Means: Right now, BackerKit is still growing their base, but if you click those crowdfunding links that keep coming up on your feed, you’ll find a growing number of them leading to BackerKit. Maybe more important, the majority of the really exciting projects led by thought leaders in the community are over there now.What To Do About It: As of August 2024, Kickstarter is the market leader and most likely your best place to start: Backerkit’s market share is still just 3% of Kickstarter’s. That said, keep an eye on BackerKit. Those numbers and the best advice might change soon.An updated plan of actionWith all the new information, and the heavy-hitting competition, is it impossible for new authors to make it with crowdfunded efforts? I’m here to tell you no. In 2019, Joanna Penn interviewed me about crowdfunding, based on my successful series of Kickstarted flash fiction anthologies. Two years later, I Kickstarted a collection of self-defense stories that netted over $20,000 just from the crowdfunding campaign.

So I’ve had a reasonable amount of success on crowdfunding, in spite of the changed landscape. And I promise, you’re smarter than me. And a better writer. And vastly more attractive. If I can have that level of success, you can do better. Below is a basic plan of action for success you can use as it is, or make the changes your experience and instinct tell you will make it even better.

Most of the coaches and experts I’ve spoken with recommend starting work on a crowdfunding campaign a full year before launch date. Before even that process starts, success begins with two important tasks.

1. Assess your platform“Platform” was a buzzword in the mid 2010s, referring to your total reach to the public. The term has faded a bit, but the concept remains the same. When you begin your crowdfunding journey, the first thing you need is a solid understanding of who is already on Team You. This includes:

Your total followers on social media like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and TikTokSubscribers to any newsletters or email lists you run, or are a regular contributor toYour close circle of professional, hand-to-hand contactsMembership in any groups or associations in which you have a leadership or highly public roleNot all of these people will back your crowdfunding campaign, but a percentage of them will. If you assume 2% will support you—either backing you, or being responsible for somebody else to back you—you’re unlikely to overestimate your platform’s performance.

2. Develop your expansion planOnce you understand the reach of your platform, the second question is how you can expand that reach. Start by making a list of each of your platform assets:

List each of your social media accounts, and their number of followersList each newsletter and their number of subscribersWrite the names of your close professional contactsList the groups you lead, and how many active members each hasCome up with three specific actions you can take for each list item. It’s okay to duplicate, e.g., using “get active on related keywords” for Instagram and Twitter. Follow up by identifying three assets you don’t have yet, but could develop quickly.

Use this sheet as the foundation of your plan to grow your platform as an author. Start working on it today. When you’re ready to start your first crowdfunding campaign, the growth of your following will help. Between now and then, it will still generate publicity, excitement, and sales.

Once you have a realistic sense of your reach, it’s time to dive into the details of your crowdfunding project. This plan applies specifically to traditional crowdfunding. If you’re looking at Patreon, some of what’s below will apply.

Begin with the goal in mindWhat do you want to accomplish? Ask 100 different authors and you’ll get 100 different answers, 150 if you come ask again six months later. That said, most of those answers—and probably yours—will fall along these general lines:

Cover the costs of editing, layout, cover design, and similar up-front expenses with publishing a professional bookLaunch the book with enough backing to make a defined amount of profitLearn how to crowdfund, and see whether or not you like it enough to do againBuild or expand your platformFuel a subscription model for your contentNone of these is the “right” or “wrong” reason to do a crowdfunding campaign. Each one will inform the rest of your decisions. For example, your funding goal will be different if you just want to cover costs versus wanting to make a meaningful profit.

That’s why you consider and define your goal at the beginning. It impacts everything else.

Choose your platformFor a long time, Kickstarter was the best place because it had more people. Like I mentioned above, BackerKit is poised to take the lead, and worth investigating even though it hasn’t as of this writing.

There are two other platforms worth mentioning:

Indiegogo is the Pepsi to Kickstarter’s Coke. It’s a solid platform but gets about one-quarter of the traffic and funding of Kickstarter. Years ago, Indiegogo had the advantage of allowing partially funded campaigns, but Kickstarter began doing likewise. These days, Indiegogo is best for people with a strong existing following, and folks who prefer to avoid market leaders for one reason or another. GoFundMe has even larger market share than Kickstarter. However, it’s for charitable giving and funding things like medical bills or school projects. It’s not appropriate for professional publishing, and I mention here only because you’ve probably heard it mentioned.Finish first or after?This is an important question that will impact the promises you make in your site copy, your fulfillment plan, and your publication timeline. Do you want to finish your book before or after your project funds? Again, there’s no right or wrong answer here, just a right answer for you.

Finish First: Starting your campaign with your book already finished provides several advantages. You have finished product to provide images on your campaign page. You can read finished excerpts during your campaign. Fulfillment is simplified and easy to keep on schedule. On the other hand, it means funding later in your publication journey. If you fail to meet your goals, you’ve written the book and paid for production to no avail.Finish After: This option inverts your process, and the pros and cons. You minimize risk by only moving forward if your project funds, but you don’t have any finished project for promotion. Your fulfillment gets more complicated, takes longer, and is more vulnerable to things going wrong.A Middle Ground: In most of my crowdfunded campaigns, I’ve taken a point in between. When the campaign launches, I have the manuscript finished, but not edited. I’ve done the heaviest lifting in the writing journey, but haven’t spent much money on production. When the project funds, I can move forward with the rest of the process.Make graphics decisionsYou’re going to need art. At a bare minimum, you will need an awesome cover to promote at various places online. If you have interior graphics, you’ll need a plan for those. If you want to get really fancy, you can get custom art for your campaign page.

Make a list of the art you want, then find out how much each piece will cost you. The market is broad and complex, made even weirder by the entry of AI. Jane has some good pieces on getting art for your book here and here.

Whenever possible, negotiate to pay your artist per piece, not by the hour. Most prefer to work that way, and it gives you a static number to include in your budget.

Know your vital statisticsYour personal vital statistics give nurses and doctors a snapshot of your health. Crowdfunding campaigns also have vital statistics. Some marketing gurus will go deep on this, offering a bewildering array of metrics by which to gauge your success. They’re not wrong, but the level of complexity isn’t helpful for those of us just starting out.

For the first few campaigns, we only need to focus on a few numbers:

How much it costs to produce each bookHow much it costs to ship each bookHow much you want to sell each book forThe total cost of your flat-rate expenses (like cover art and marketing)How much profit you want to deriveIf you know these numbers, you can figure out how many copies you need to sell. This tells you how much your campaign needs to make. For example, with some thought and research you find out:

It costs $3.00 per unit to print a book of the size you plan to produceIt costs approximately $5 to package and ship each bookYour flat rate expenses include:$500 for cover art$750 for editing and layoutA $500 advertising spendYou’re testing the waters on this one, and want to make $1,000 profit off this campaignBased on this, you need to cover $1,750 in flat rate expenses and want to bring in $1,000 in profit. Each book costs $8 to print, and a little research shows you can sell books of your sort for $18. That’s $10 gross profit per book.

At $10 gross profit per book, you need to sell 175 copies to cover your flat rate expenses, and 100 copies to bring in your desired net profit…except for one thing.

Kickstarter charges a 5% fee for its services, and your payment processing will run another 3–5%. Assume 10% in fees, so add 10% to the number of books you need to sell. That’s ten percent of 275, or 26.5. We’re not sending people to Mars here, so it’s okay to round that to 300.

Your specifics will naturally be different, but you get the idea. It’s vital to know this information before setting up the rest of your campaign.

Pro Tip: Kickstarter gives lots of publicity mojo to campaigns that meet their initial funding goal early. This has led many pros to set their official funding goal at a fraction of what they actually want so they meet that requirement. This approach has its pros and its cons. It’s up to you.

Create your preview pageThis is a landing page that gives visitors information about your book, and a way to put themselves on a mailing list so you can let them know when you go live. Every major platform offers a free landing page as part of starting your campaign. Kickstarter, Indiegogo, and BackerKit allow you to set up that landing page months before your launch day to start collecting emails and building excitement.

Some others exist, like ClickFunnels, Unbounce, and SamCart. They have advanced functionality that experts can use to fine-tune their prelaunch mojo. Those tools are powerful, but if this is your first crowdfunding project, they will require a whole other learning curve. For beginners, the page from the platform will do just fine.

A word about scheduleAt this point, you’re ready to set a launch date. There are two schools of thought here.

You can set a date for your campaign, then work towards it. Aim for a time where you will reliably have the time and energy to put yourself fully into making it wildly successful.You can create a preview page that allows people to sign up for updates. When you reach a critical mass of signups, you announce the campaign will begin in a few weeks.The second reliably produces better earnings and results. However, it’s more complex and might push you into running your campaign in the middle of other projects. My recommendation is you set a date for your first campaign, then try the preview page method once you’re more experienced and ready for greater complexity.

The campaign itselfWhether you set your launch day at the beginning, or you wait until you have that critical mass of subscribers, eventually you will reach your launch. It’s important that, from launch day minus 30, to a week after closing, you consider this a part-time job you’ve taken on in addition to your other responsibilities.

Yes, that means many authors will be working their day job, seeing to family, trying to write, and be putting 10–20 hours a week into this campaign. That’s a lot, but it’s often worth it. Consider taking time off from writing while you’re in the thick of this.

You can run a campaign for as long as you like, with publishing projects typically coming in at around 30 days. Generally, all campaigns get the majority of their backing during the first and final weeks, so a two-week campaign where you’re highly engaged can also work. It’s up to you.

You can find many excellent, detailed plans for making your campaign work. In my experience, the differences between them are either cosmetic or boil down to personal preference. For your first campaign, pick one you like and follow it to the letter. This isn’t the time to reinvent the wheel. Use a blueprint from somebody who has experienced success, then tweak it for your second campaign once you’ve seen it in action.

Fulfillment and beyondAs tempting as it might be to breathe a sigh of relief at the finish line, you have a long way to go yet. Crowdfunding isn’t just a marathon. It’s a marathon you run after a 60-day sprint. How you behave after closing day will determine a lot about your relationship with your fans, and how receptive people are to your next crowdfunding project.

They key is to keep consistent communication with your backers. Kickstarter explicitly doesn’t guarantee that paid-for campaigns will deliver, and the web is full of horror stories where backer funds disappeared. If you keep your backers posted, they will be forgiving if things fall behind schedule.

However, don’t go overboard with this. A post a week is more than sufficient. You can get by with a simple status update, sharing everything that happened during that week that moved your campaign closer to shipping. On weeks nothing happened, post some kind of preview, even if it’s just a screenshot of your work.

Be sure to make and post an unboxing video when the first books arrive at your home.

Okay, so now what?I get it. This feels like a lot—and it is. Crowdfunding campaigns are not small endeavors. But, just like writing a novel, the trick is to figure out where to grab hold of it. Once you do that, the rest is just one step at a time.

What I recommend is asking yourself four core questions. Once you’ve answered them, you can start at the top and do everything else in its time.

What? Exactly what book (or kind of book) do you want to produce? Think on this until you know enough to write a proposal and outline. That level of specificity will help you figure out the basics of your campaign.Why? What do you hope to accomplish by undertaking a crowdfunding campaign? I went through the most common reasons earlier. Take a moment and review those, then brainstorm any other reasons you might have. Then pick one and focus on that goal.By When? When do you want to see the results of this attempt? I strongly recommend setting that for at least six months out. Preferably you would give yourself a year. Whatever you choose, creating a timeline will help you set up for success.What’s First? What is the first thing you need to do, discover, create, research, or find a mentor about to maximize the success of your campaign? With projects this large, momentum is important. Identify that first thing, and do it today.August 22, 2024

The Importance of Interiority in Novels and Memoirs

AI-generated image by ChatGPT: a writer works on a typewriter in the back of a dark theater; characters are on a stage with a spotlight shining on a single individual

AI-generated image by ChatGPT: a writer works on a typewriter in the back of a dark theater; characters are on a stage with a spotlight shining on a single individualToday’s post is an excerpt from Writing Interiority: Crafting Irresistible Characters by Mary Kole.

A lot needs to be conveyed in a story, from the most superficial ideas to the most profound, and character is the lens through which everything is channeled.

In broad terms, the concept of interiority can be defined as a character’s:

ThoughtsFeelingsExpectationsReactionsInner struggleThese can be expressed in moments big and small. Interiority can be used to mark character growth and change, as well as scene-level reactions to events.

Generally, information can be deployed at four levels of narrative depth.

1. Narration: The reporting of events without reaction or interpretation, as if the character is a security camera, seeing the scene with no specific slant. Though a lot of narration is going to be rendered in a concrete point of view, which is inherently biased, this portrayal of events is about as neutral as you can get. Narration can be played out in a full scene, or in compressed narration, which means a summary of events—like a progress montage in a movie. Most narration is not considered interiority.

2. Interpretation: Interpretation happens when a character sees a scene from a specific emotional or intellectual perspective, with commentary and context that add a personality layer to what is being shown and experienced. Interpretation can be added to small and big moments in a story to develop a character and their unique point of view. We’ll mostly find thoughts, feelings, and reactions at this level of depth.

3. Extrapolation: This involves a character making significant meaning from the stimulus or event in the scene, whether they remember something relevant from the past, change their perception of the present or future, or decide something about the self or another character. Extrapolation is usually reserved for describing bigger or more pivotal moments of character development, or is attached to a reaction or decision that will angle the plot in a different direction due to cause-and-effect logic. In addition to applying to thoughts, feelings, and reactions, extrapolation is closely related to setting, resetting, and analyzing expectations. Here, characters can also ask questions, reexamine their positions, and otherwise dig into what a specific event, relationship, or piece of information means to them in a deeper sense.

4. Subsumation: The character uses the information or stimulus to perform self-reflection and integrate this new information or emotional development into their sense of self, to expose something hitherto unknown about their subconscious, or to grow or change on a deeper level. For example, extrapolation might inspire a character to take a different action, based on perception and interpretation, but subsumation will inspire a character to behave differently from a moral perspective. All of the functions of interiority can come into play at this deepest level, but especially inner struggle.

Contained within these levels of narration is a writer’s opportunity to connect deeply with their own point of view character first, and then, eventually, foster that relationship for readers. By using the tool of interiority, you are adding emotional context for what your character is experiencing in the moment (and outside of it, too, as they remember the past and wonder about the future).

If we review the above list, we’ll notice that narration is going to almost always be present as characters go through scenes and move the plot along. It’s crucial to note that not every moment needs interiority. Sometimes, narration is sufficient. But when we start to go deeper into character perspective with interpretation, extrapolation, and subsumation, we’ll find ourselves adding different layers of depth and meaning. This is the realm of interiority.

The science of thinking, how people think, what they think about, as well as how the mind interfaces with the body and vice versa, has come a very long way in the last century. We are far beyond simplistic (and largely discredited) ideas like a “left brain” or “right brain” personality now. Without getting into psychology and neurology, there’s a very helpful and simple set of questions that can also help you access deeper levels of character and interiority: “And? So?”

If you realize that you’re having trouble getting to a juicy level of depth with your interiority, stop and ask yourself what’s really going on, or how you can make additional meaning for your character in the moment. Here’s an example of how to use “And? So?” when training yourself to think more profoundly about your character’s experiences, reactions, and choices.

Let’s say we have a scene where the protagonist, Sharon, is merely attending a work meeting before anything disruptive happens. (If nothing disruptive ever happens, of course, you may want to consider whether the scene is pulling its weight.) We’ll get some narration of people filtering in, but that’s not exactly story-worthy, so let’s start digging.

And?

Well, what if this is the meeting where the big promotion will be announced?

So?