Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 41

November 7, 2023

3 Common Fears of Hiring a Freelance Editor

Photo by Pixabay

Photo by PixabayToday’s post is excerpted from How to Enjoy Being Edited: A Practical Guide for Nonfiction Authors by nonfiction writing coach and editor Hannah de Keijzer.

Hillary Weiss Presswood is a powerhouse brand strategist who projects confidence like a disco ball. But in the middle of writing her first book she asked me an important, not-so-sparkly question:

“Do you ever find yourself judging clients juuuust a teensy bit?”

Are you judging me?I hear some version of this question often—most editors do—and I understand it completely. You’ve worked really hard. You generally like to be good at what you do. You certainly want to write a good book. And you’ve poured so much of yourself into your writing that sometimes your writing starts to feel like a part of you, so anyone criticizing your writing is criticizing you. That’s painful. It’s also not what’s happening in the author-editor relationship.

Here’s the distinction I like to draw. I’m never judging, but I am using judgment all the time.

Passing judgment—as in to “criticize or condemn someone from a position of assumed moral superiority” (thanks, Merriam-Webster)—has absolutely no place in editing. It honestly doesn’t occur to me. Not even a teensy bit.

But judgment is an essential part of an editor’s job in the sense of informed discernment, “the ability to make considered decisions or come to sensible conclusions” (thanks again, Merriam-Webster). Editors make judgments on every page of your writing, about your writing, so that we can draw out the best in it. I want your book to be clearer and more compelling after I edit it than it was when you passed it to me. Ideally, working with me will also help you level up your own writing and revision skills so you get better as a writer, project after project. My judgment works toward those ends.

But, as LeVar Burton used to say at the end of every Reading Rainbow episode, you don’t have to take my word for it. So what do other editors have to say?

Kendra Olson emphasizes learnable skill instead of bad or good: “An author I worked with on a developmental edit expressed concern that her writing might not be any good. I told her that I tend to view writing as being more or less skillful; in other words, writing is a muscle that can be strengthened. The author-editor relationship plays an important role in this.”

Jennifer Lawler, editor, editing teacher, and Resort Director at Club Ed editorial community, says: “As part of the editor-vetting process, get a feel for how a prospective editor talks about the authors they work with. If their Bluesky account is a constant stream of snark about authors, of course you’re going to feel judged if you have them edit your manuscript. But if you’re working with a good, well-trained editor, they’re going to be focused on helping you do the best work you can. They’re not thinking that you’re an idiot for misspelling your own name. Everyone occasionally makes mistakes, fails to see the broader perspective, and uses fifteen words where three will do. Your editor isn’t judging that, they’re just trying to help address it.”

Language editor Claire Cronshaw says, “If it’s the idea of accuracy that’s scaring you, don’t worry about it. Getting the accuracy right so the story can be enjoyed is where editors and proofreaders can help you. So bring your work to me without fear of embarrassment. I’m not judging you. An editor is not an examiner. An editor is not your teacher. Don’t let school day hang-ups get in the way of your success.”

How do I know when it’s time to let go?Some writers can’t wait to pass their work to an editor so they can stop looking at the damn thing. Others tinker and tinker and tinker, convinced it’s never quite good enough; someone has to pry the manuscript out of their hands. Most folks are somewhere in the middle but wonder when it’s the right time to pass the work off for a boost. So how do you know when it’s time to stop working on your own—when it’s “ready”?

Here’s how you know it’s not ready: if you haven’t done at least one thorough, careful revision on your own, preferably more.

But it is ready if you think it’s as good as you can get it without help, and you want it to be better. It’s ready if you aren’t sure what to do next or even whether it’s making sense to other people. It’s ready if you think the next step is one in which you don’t have as much skill—like if you’re a big-picture thinker but you need help lining up all the little details to support that big picture. It’s ready if you feel you just can’t “see” it anymore. It’s definitely ready if you’ve started to worry that your revisions are actually making things worse or sucking the life out of your writing.

There’s a sneaky second question here: When are you ready to hand the manuscript off to an editor? If you’re having trouble separating yourself from the manuscript—you can see the document is ready to go but you’re not emotionally ready to let it go—take a deep breath. Why aren’t you ready? Would it help to reread the section on judgment above? Consider talking through the why of this with a friend or colleague whom you trust not to tease or shame you, but to listen, help you explore, and invite you to let go.

If you’ve put in the effort to find a professional editor you click with, I hope you will let yourself take the leap, trusting your editor to handle your work with respect and care. A good editor is rooting for your work and for you, doing their best to enliven your book and make you look great in the process. And communicate with your editor. Feeling nervous? Tell them. They may suggest a tweak to their working process, like a midway check-in, that will help set you at ease.

Will you rip the heart out of my book and make it sound like someone else? Amazon • Bookshop

Amazon • BookshopI’ll tell it to you straight: there are some editors out there who are more concerned with their vision and voice than with yours. They might very well smother your book or tear its heart out. But the editor who will do that is, frankly, not good at their job. A good editor will speak up thoughtfully and straightforwardly when they think your preferences are holding your manuscript back, while honoring your style and making the best of your voice shine.

This is one reason why the initial emails and conversations with a potential editor, their testimonials, and the sample edit are so important. Do you like how the editor treats you? Treats your manuscript? How they ask questions and phrase their suggestions? If not, it’s OK to move on and find someone else who will take better care of your work.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out How to Enjoy Being Edited: A Practical Guide for Nonfiction Authors by Hannah de Keijzer.

November 6, 2023

Creative Planning for Authors and Poets

Photo by S O C I A L . C U T on Unsplash

Photo by S O C I A L . C U T on UnsplashToday’s post is by Orna Ross, the founder of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi).

I don’t believe in the old adage that “if you’re failing to plan, you are planning to fail.” Writers understand the subconscious mind and know you can often rely on it to deliver more elegant solutions than hard thinking.

But I do believe in creative planning for authors, the kind of plan that recognises the power of the subconscious. That emphasizes intuition, imagination, and flexibility, as much as structured, data-driven goals and systematic processes, allowing for organic growth and adaptability.

Through my own experiences, and through observing tens of thousands of authors as director of The Alliance of Independent Authors, I’ve seen poor plans and no plans derail many books and authors. Without a system to integrate the learnings from the inevitable failures and vagaries of the creative life, sub-par performance and associated discouragement become almost inevitable.

Maya Angelou said, “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.” Soldiers or social workers might disagree, but yes, blocked, unfulfilled ambitions burn inside us, and create very real, very painful psychological conditions. It doesn’t have to be like this. Recent research and ancient wisdom about the creative process is now available to us all.

And the number one truth about that process is that creative resistance points up where we need to grow, if we’re to achieve the things we want.

The gap between where we are and where we want to be is full of creative challenges.

For many years now, I’ve been working on a creative planning program for writers. It began with my own needs, at a time when planning for me was no more than a to-do list and a daily check-in with my creative self. As a novelist with a traditional publisher, that had worked well enough for me. Or so I thought!

When I took back my rights to become a working indie author, my planning method wasn’t good enough. The to-do list felt like a tyrant. I’d go to sleep ticking tasks off in my head and wake up remembering things I’d forgotten.

I tried other planning systems but either they were too mechanistic and boxed me in, or they weren’t planners at all, just fancy calendars. They didn’t account for the messiness of creativity. They didn’t acknowledge the writer’s need for creative rest and play as well as work. And they had no understanding of the dynamics of creative resistance, block and failure.

As a self-publishing novelist and poet, and director of a busy non-profit, I needed a much more creative planning method.

The common ways authors failWriting a book that finds its readership is quite the challenge, and anyone who sets out to do it can be become derailed at any stage of the process.

Fail to complete the first draft: The vast majority of manuscripts never reach “The End.”Fail to complete the final draft: A wave of creativity carries most writers through the first chapters but things often peter out, or the writer gets caught in the self-editing process.Fail to publish: Getting your book produced and distributed calls for skills that are very different from those needed to write a book. Whether you decide to publish the book yourself or use a traditional publisher, you’ll need to be highly motivated, organized and resilient. For indie authors, there are extra challenges. Writing and publishing draw on very different parts of the cognitive and emotional systems and the number of moving parts can be confusing, especially on a first book.Fail to build an author platform: No matter how you publish, you need to do the author’s part in marketing, promotion and platform building. So many writers fail to even try. Others fail to educate themselves in how books are marketed in these digital days.Fail to profit: If you just want to write and publish a book for personal reasons, all good, but if you want to make a living as a writer, you need to work out how to do it in a way that’s sustainable for you—so you can write and publish more books. For indie authors, publishing is a business and businesses must make a profit to survive.When writers experience any of these failures, they can become utterly discouraged. They unthinkingly feed themselves unproven explanations and assumptions. That they “love writing but hate marketing,” for example, even though for a writer marketing is writing. Or that they are not “good enough,” or that success is a pipe-dream, possible for others but not for them.

All of this becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

There is another way. To understand that writing and publishing are two high-order skills that a successful author takes time to master, and each in their own way. That there is a creative solution to any challenge an author might meet on their way to mastery. That our “failures” are flags, pointing up where we need to grow and change to get where we want to go.

This is where good creative planning comes in. When the inevitable failures happen, without a plan we can be submerged by our feelings and emotions. With a creative plan in place, we can integrate the experience, and the learning it affords us, into our creative process.

Writers at every level, and every stage of development, benefit from creative planning.

What is creative planning?A good creative planning program is much more than a way to divide up time. While it works with quarters, months, weeks and days like any planning system, it allows room for the unexpected and the open-ended messiness that is part of the writer’s life.

Often, there’s an inherent tension between the act of writing (an intimate, self-directed process) and the business of publishing (a public, other-directed process). This tension can be disconcerting for many authors but with a robust creative plan in place, balance becomes possible.

By setting clear boundaries and allocating dedicated time for both pursuits, writers can ensure that their artistic integrity isn’t compromised while still achieving success. When both publishing and writing proceed from creative principles, everything works better.

A robust creative planning system helps us to acknowledge what’s going on for us, and figure out how to harness our own creative energies in an optimal way, through all the varying challenges we meet. It sets us up so creative flow can … well, flow. Getting into flow isn’t just about spontaneous inspiration. It’s about guiding inspiration with intention.

At its core, creative planning is the act of methodically mapping out where you are, where you want to go, and how you are going to process the challenges that are coming up for you today.

It defines and sets clear measures of success that incorporate your mission, passions and sense of purpose into your daily work.It filters time and money through processes that boost creative productivity, author platform, and return on investment.It balances qualities that are often wrongly posited as opposites—productivity and pleasure, purpose and promotion, money and meaning—and integrates the different aspects of the job. An author must wear three hats: maker, manager and marketeer. A good creative plan makes room for all three, each week.It also acknowledges the importance of planning creative rest and play. In our quest for work achievement and the pressure to keep ticking off our to-do lists, we often overlook that creative magic happens in the doing, yes, but also in the undoing. A mind allowed to rest and play is a mind primed for creative flow, when work time comes round.

The act of recharging our creative capacities should not be treated as an afterthought but the very foundation of our most inspired work—in our publishing and platform building, as much as our writing. Creative rest and play aren’t breaks from the process, they are the process. My experience, and the experience of so many of the authors I’ve worked with, is that they should be planned for—or they won’t happen.

Introducing Go Creative! PlanningOver the years, as I navigated the realms of writing and publishing, I developed a planning method that has kept my creative journey both fruitful and joyful, in the face of many challenges. Now I’ve decided to share it, not as a one-size-fits-all solution, but as a framework that respects the individuality of each author.

I’ve observed many authors feeling adrift or overwhelmed but I know that when we harmonize our work, rest and play; our inner maker, manager, and marketeer; our passions, mission and sense of purpose, we ensure that our creative wells never run dry. We support ourselves in the best possible way, as we unfold our own, chosen vision of success.

I want to see as many writers as possible living out their creative dreams, without getting lost in the labyrinth of overwhelm, resistance and block. Through the Alliance of Independent Authors, we offer self-publishing advice that answers questions and solves problems, but this planning program is more personal. All the advice in the world doesn’t help if you’re not on the right path.

The program is born out of my desire to see all authors not just survive but thrive, and is my way of extending a hand to all.

If you’d like to learn more about creative planning, and how to bring the program to other authors, visit my Kickstarter.

November 2, 2023

How to Read (and Retain) Research Material in Less than Half of Your Usual Time

Photo by Stas Knop

Photo by Stas KnopToday’s post is by author Thelma Fayle.

For the last two years, I’ve had unexpected success in experimenting with my “chipmunk research method.” I was inspired to try this technique after hearing an intriguing comment made by my friend Oriano Belusic, past president of the Canadian Federation of the Blind (CFB).

Blind since age seven, he has learned to read at high speeds. (I use the term “read” for audiobooks, as this is the word used by most blind people I know.) Oriano uses a screen reader, which he routinely sets to a speed of 2.5. A speed of 1 is normal audiobook speed for most of us.

When I first stood by his side while he read an email, I could not understand the fast and garbled speech. Yet, Oriano says he is on the slower end of the spectrum when it comes to screen reader speed. He said he knows blind people who, through repetition, practice, and experience can read at chipmunk-fast speeds of 3 or 4.

I was skeptical, but my friend insists anyone can train themselves to discern fast speech. He suggested our brains, with very little coaching, can do unexpected things outside of our usual understanding of “normal.”

I learned he was right.

As a recent MFA graduate (narrative nonfiction), every day I encounter more nonfiction books than I have time to read. So, I decided to try speeding up my research methods by reading the hardcopy version and the audiobook at the same time.

To avoid purchasing two copies of the book, I often borrow the hard copy from the library, and purchase the less expensive audiobook from Audible. Speeded-up listening is not the old speed-reading hype from years ago. That approach involved more scanning than reading and was never successful for me. This is different.

When I started reading a thick book that would normally have taken me two or three weeks to finish, I decided to play around with the audiobook speed. Over a couple of days, I notched it up to 1.2, and then 1.5, 1.8, before eventually pumping it up to 3 a few weeks later. As I read the print book, I keep pace listening to the audio version. The idea may sound improbable, but I felt like I did when I learned to skip French ropes when I was nine. One minute it looked impossible, and the next I was doing it.

The process involves using several senses as I visually read, listen to every word, and underline critical passages (if the hard copy is mine). Keeping up with the fast speed requires studious focus with a simple pause or rewind if I need to stop and reflect. While I was at first doubtful about whether this would work, I have discovered I have uncommon retention of the material using this technique—and believe it or not, after using it for a couple of years I find it relaxing to be intently focused on the content.

I also love knowing that I can pick up any huge nonfiction tome and read it thoroughly in less than a week. This approach is probably better for reading nonfiction than fiction—unless you are reading fiction for research or are under a time crunch.

Below are a few examples of recent successes on my path. I read these titles in one-half to one-third of the completion time listed on the audiobook:

The Complete Essays of Montaigne (Stanford’s Frame translation, 1957) — 883 pages, listed on Audible at 50 hours, took me less than 20 hours to read.Random Family: Love, Drugs, Trouble, and Coming of Age in the Bronx by Adrian Nicole LeBlanc — 436 pages, listed at 20 hours, took me 9 hours.A Swim in the Pond in the Rain by George Saunders — listed at 15 hours, took me 5 hours.Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Futures by Merlin Sheldrake — listed at 10 hours, took me 4 hours.The Golden Spruce by John Vaillant — listed at 9 hours, took me 6 hours. (I slowed down on this one to revel in the hauntingly beautiful nonfiction story. I did not want it to end.)Over time, I have adjusted my research process to read at different speeds. How I feel on the day and the complexity of the text may determine the speed I choose. I am a little slower if the subject is less familiar to me, i.e. science.

My chipmunk research method is a towering time-saver, allowing me to—believe it or not—enjoy researching and doing more of it. I hope this offers you a useful idea to explore.

However, there is a drawback: Reading at a normal audio speed of 1 now feels unbearably slow!

November 1, 2023

How to Turn an Essay into a Book Deal

Photo by CJ Dayrit on Unsplash

Photo by CJ Dayrit on UnsplashToday’s post is by author Catherine Baab-Muguira.

Getting a traditional, “Big 5” book deal is almost unbelievably difficult. Many will try. Few will succeed. What’s more, talent is cheap. Hard work, persistence, unchecked ambition-slash-megalomania? They’re cheap, too.

What can help you land a deal is “proof of concept.” Let me explain.

In marketing, “proof of concept” refers to the process of testing a new product or strategy to assess its sales potential and viability before you go all-in on a full-scale launch. It usually involves conducting a limited, real-world trial, the purpose of which is to gather evidence that will allow you to make a larger, grander case. I did 12 years’ hard labor in corporate marketing. That’s how I know.

When it comes to selling your book, proof of concept means demonstrating there’s a large, enthusiastic audience out there ready and willing to shell out $18 for your masterpiece. And a great way to do this is by publishing a nutshell version of your big, central idea in essay form.

How it worked for meIn the summer of 2017, after months of pitching with no luck, I finally found a home for the essay I was dying to write. It was about how reading the work of Edgar Allan Poe during a deep depression had effectively saved my life. Restarted my creative drive. Renewed my hope for the future.

Numerous prestigious outlets, from the Washington Post to The Atlantic, had rejected or ignored the pitch, so when the literary website The Millions agreed to run it and pay me a whopping $25 for the privilege, I was thrilled. My motivation came down to personal fulfillment and sharing an interesting experience with the world, not fame or money. The token compensation mattered not at all. What I hoped for was an audience, and in that, The Millions more than delivered. My essay went modestly viral in a literary world kind of way, racking up likes and shares on Facebook and Twitter, and became one of the site’s most popular articles of the year.

By this point in my freelance career, I’d grown accustomed to following my own work around the internet. It fascinated me to see Redditors discussing a piece, and to track which newspapers, magazines, and other outlets shared the piece on their socials was especially gratifying. Often these same outlets had rejected the pitch.

This time out felt no different, at least not at first. I googled the title of my article and discovered what readers were saying, a process that brings both pleasure and pain. Then I noticed something I hadn’t expected: my piece was being shared in gigantic Poe fan groups. For instance, by the official Edgar Allan Poe Facebook fan page, which has nearly 4 million members. I’d never realized so many Poe fans existed, or for that matter, that they gathered in dedicated online spaces.

I kept digging, and what I learned lit my brain up. Not only did my fellow fans number in the millions, many shared the same view of Poe as I did: He was their hero, too. A kindred spirit struggling with mental-health issues, and an inspiration to pursue their artistic work despite knowing it would almost certainly go unpublished and unappreciated.

It would be dishonest to say that, from this point, my book proposal wrote itself. Book proposals aren’t easy to write, hahahaha dear God no. But making the case for a self-help book based on the life and work of Edgar Allan Poe became much easier once I could point to the article’s success—and even share emails from readers responding to the piece.

I hadn’t meant to “pilot” my idea, but pilot it I had.

How it can work for youHow this advice applies to nonfiction is straightforward, but it can apply to fiction, too. You could pilot your big novel idea as a short story. You could also pilot it as an essay on your main topic or theme, or the autobiographical experience which inspired you to write the book.

Whatever genre you’re working in, the process remains simple—dare I say easy.

Step 1: Write the pitch.Begin by crafting a compelling pitch for your essay. This pitch should be a concise and engaging description of your idea, clearly conveying the core concept that you plan to explore. (For more on freelance pitching, see here.)

Step 2: Pitch editors at relevant outlets.Identify and research relevant online publications, magazines, or websites that cater to your target audience. Carefully tailor your pitch to these specific outlets, highlighting why your essay aligns with their readers’ interests, and referencing articles the outlet has recently published. Keep in mind you may have to pitch lots of outlets before finding a taker. Begin with your top choices and work down from there.

Step 3: Promote the hell out of your essay.Do not bet on organic success. Instead, once your essay is published, do every last thing you can to maximize its reach. Share it across your socials, obviously, and don’t fail to beg your friends, family, and followers to do the same. Consider tapping into your professional network, too. For example, I belong to Study Hall, an online organization for freelancers with an active listserv, and once a year, members can ask each other to “boost” a particular piece. You may also belong to organizations in which you can ask for support from like-minded individuals, too, which can go a long way toward amplifying your essay’s reach.

Step 4: Gather data by stalking your work around the internet.Keep a close eye on the performance of your essay. Google the headline in quote marks (as in “My essay title”) and see what Redditors are saying. Keep track of views, likes, shares, and comments. If notable people, organizations, or publications share your piece, make a note. This data will help you prove your concept resonates with a large audience, perhaps even a distinguished one.

Step 5: Belabor your essay’s success in your query and proposal.What’s the point of all this? Making a big ol’ to-do about the success of your article. In other words, don’t bury the lede. Foreground that success in your query letter when approaching literary agents, and foreground it in your book proposal, too. You can and should mention its success in your Overview essay and in your Audience section.

Step 6: Maybe do all this in video form, not essay form. I don’t know. You tell me. It’s worth a thought.I’d be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge how much the internet has changed since 2017. The heyday of the “first-person industrial complex” appears to be behind us, with short-form video most definitely emerging as the tool du jour. That doesn’t mean you can’t effectively pilot your book idea. It means you should consider piloting your idea via video, if that’s a thing you’re into and a medium you like. And, frankly, even if it’s not a thing you’re into and not a medium you like. At the very least, consider doing both—piloting via essay and via video. Leigh Stein offers some excellent advice on the point.

Break a leg, friends! And go get that proof of concept.

October 31, 2023

Earn Six Figures as a Writer With This One Weird Trick

Photo by Porapak Apichodilok

Photo by Porapak ApichodilokToday’s guest post is by Allison K Williams (@guerillamemoir). Join her for the three-part class Build Your Developmental Editing Business, beginning on Wednesday, November 1.

“I went with a small press, but I didn’t need my book to pay the bills.”

“It was a nice rejection, but ‘great voice’ isn’t gonna pay the bills.”

“A lot of really great writers still aren’t getting paid enough to pay the bills.”

In a writers group online, my colleagues commiserated—about how hard it is to sell books, about the “memoir industrial complex” that promotes a very few big-deal successes while other authors shell out thousands for classes and editing and invest their time in “building platform” that is still statistically unlikely to get a book deal. Over and over, I see this phrase: pay the bills.

While enough to pay the bills is a perfectly valid colloquialism for “an amount of money that emotionally balances the time and effort I’ve put in,” it’s also a terrible goal. I mean, first, screw this pay the bills crap, why not aim for a life-changing amount of money? If you’re aspiring, reach high. But more importantly, very few authors earn enough to pay the bills in any meaningful way.

Do the math. A generous six-figure advance—we’ll go with $200,000 to make it easy—often gets doled out in four chunks: on signing the contract, on submitting the final manuscript, on publication, and then some months after publication. Usually those chunks are about a year apart. Deduct 15% for the literary agent, 30% for taxes, and congratulations, you’re paying the bills with $27,500/year. Just enough to disqualify a single adult for Medicaid in most US states.

Most full-time writers pay the bills with teaching, speaking, offering classes, freelancing, or as magazine/newspaper staff. Most writers making a living are part of a two-income household, in which writing means less childcare than temping and fewer parking problems than adjunct teaching.

You already know this. And I’m not here to amp up our collective bitterness at the unfairness of our calling. I’m here to say it’s possible to pay the bills as a writer, with one weird trick.

I am a writer. I’m also an editor, a retreat leader, a webinar teacher and a public speaker. I love all of these things—nothing makes me happier than a writer discovering their voice—and they are all possible because the foundation is writing. They also all focus on the reader. The person who needs what I have to teach, write or talk about, and how I can serve them.

I’m embarrassed to say that I’m proud of my income. But I sure do tick off on the Excel sheet which day of the year I hit my goal, and if I can make it earlier in the year than last year. As an editor I get to watch TikTok nuns, listen to Kae Tempest and analyze Legally Blonde and it’s all on the clock. I’ve worked from Starbucks in Hong Kong, the tallest building in Vietnam and my mother-in-law’s porch in Jamaica, and coughed up $17 for airline wifi to send back time-sensitive edits over the Atlantic Ocean from business class. When I lead retreats, I’ve learned to allow two days before and after with room service and a spa, to top up my own emotional reserves after tending to writers for a week.

I live this life due to one weird trick: generosity.I give away about a third of my time to literary citizenship. Even if a writer didn’t sign up for my paid class, if the agent I used on an example slide might be the right agent for them? I’m sure going to tell them when they post on Facebook about finishing their book.

I listen a lot. I jot down what writers love, what writers complain about, what writers fear, what writers hope. We make ourselves approachable when we listen, and we make ourselves hire-able when we are approachable.

I write a lot, and I don’t worry about undercutting my book sales by sharing knowledge. Dealers have always known: give away a sample of your very best stuff, and you’ve got a customer for life. Given how many authors I work with who are writing about their struggle with addiction, I’ve seen this secondhand. I’ve seen this firsthand in my years of work as a street performer. When my partner and I appeared on Dragon’s Den Canada (known as Shark Tank in the US), we began our presentation with, “We have developed a product so compelling, we can give it away on the street, and people line up to hand us money even though they could leave with no penalty.”

The investment we won was six figures. We paid the bills.

The second part of generosity is sharing with your colleagues, not just your audience. When I was a trapeze artist, the industry of performing at corporate events was very secretive. Established performers didn’t want to tell newcomers what they billed, for fear of being undercut on the next bid. Then we all complained about how newbies were setting their prices too low.

The newbies didn’t know any better. Someone had to tell them, and that was me. After a slightly shady club manager called for quotes for Kristin Bell’s birthday party, I called every aerialist I knew in a three-state radius to say, “This is what I bid. I think he’ll try to lowball you.”

We all made more money, and not just on that gig. Now we all knew the going rate. We could choose to bid higher or lower, to compete on quality or on price.

Every time I’ve shared concrete, actionable information, on how to write, on who to pitch, on how much money to ask for, on where to find clients, on how to close the deal, and shared it for free, it’s come back to me sixfold.

Perhaps you prefer to limit your human interaction, or know that giving away a big chunk of your professional time is not for you. You can still make six figures as a writer, if you are so dedicated to your literary craft that your work is about the reader’s need to understand humanity; or you write genre fiction with the reader in mind and learn how to work Amazon ads. (Jane just wrote about how self-publishing authors are outstripping traditional authors on income, by a lot.)

My life changed when I realized how much generosity could do that protectiveness, isolation and fear could not.

That’s the magic formula to make a six-figure living as a writer. Focus on your customer, your client, your reader. Give away a substantial chunk of what you do and make it the good stuff. Help your colleagues up the ladder. Share what you love, as freely as you can.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us beginning Wednesday, November 1, for the three-part class Build Your Developmental Editing Business.

October 26, 2023

What to Expect When You’re Expecting a Parade

Photo by Beth Macdonald on Unsplash

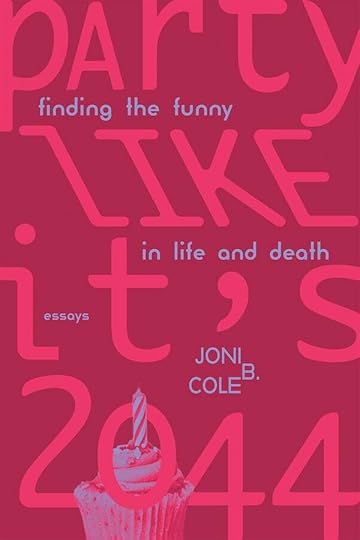

Photo by Beth Macdonald on UnsplashToday’s post is by author Joni B. Cole, author of Party Like It’s 2044: Finding the Funny in Life and Death.

All hail the newly published author. Or not.

A few weeks ago my new book came out, a collection of literary humor essays. You would think given this is my seventh book (from six different publishers), I would be well prepared for this momentous occasion. And in some ways I was.

In the month or two before my book’s release I bought new eyeglasses that make me look more writerly. I also gave the Whole 30 diet a try and, yes, I modified it to the Whole 5 because I cannot not enjoy a glass or two of wine on weekends, but the point remained the same. I wanted to be well prepared for my upcoming author events and I knew from past experience that presenting is a lot more enjoyable if I can not only wear my favorite nice jeans, but also manage to zip them.

I also did a few other things, like update my author website, refine my talking points for book-group discussions, contact regional bookstores and libraries that might want to host a reading or talk, and query writing conferences about teaching workshops on the craft of essays. Last, but hardly least, I sacrificed hours of binge-watching all the TV shows I had missed while writing this new book so that I could research niche publicity opportunities (blogs, podcasts, Facebook writing groups, etc.). My understanding was that I would need to pitch these places myself, knowing that my publicist at the publishing house was already overworked and sick of me.

All this to say, as my pub date neared, I felt ready for the launch of my book. I felt confident. I felt, dare I say, full of myself, and rightly so! The pre-publication buzz (at least in my small circles) had energized me. The head of marketing at my press had actually used the word “commercial” to describe the book. (A first among my various titles.) And the back cover of the book glowed with positive blurbs from highly respected authors, some of whom I didn’t even know, and who didn’t owe me any favors.

What could possibly go wrong? I just hoped when the accolades poured in and the sales figures soared, all this success wouldn’t go to my head.

Then the book’s pub date arrived and… No marching bands. No floats. Some nice bunches of balloons.

For context, I should share that I am not what you would call a “big-name” author, though I am a seasoned author who has been described as a “writer’s writer.” On a related note, while I love my current publishing house for its commitment to quality and diversity, it’s not one of the Big Five, not like, say, Penguin Random House where the lovely (truly) publicist Bianca regularly emails me the nicest queries to see if I would like to interview any of her authors on my podcast—“Sending you big hopes and wishes that you will consider [insert big-name author] as a guest on your show. And just let me know if you’d like a finished hardcover copy!” (Yes, Bianca! I would love a hardcover copy!)

All this to say, if I am being honest about the whole parade thing for my own new release, I knew I’d probably set my expectations way too high, though a midlist author can dream. But what did take me by surprise were several other things that happened (or didn’t happen) in the weeks following the book’s release.

Below are seven lessons I have learned (or relearned in some cases) about what to really expect when a new book is published.

1. Expect to be vigilant. My gosh, the number of little screw-ups I kept encountering in the first weeks after my pub date. In the editorial reviews on my book’s Amazon page, for example, the name of one of my reviewers was misspelled (though it was correct on the book cover). Amazon also failed to include a link to the Kindle edition, an oversight which was finally corrected a month and four days after the book’s release.

Other snafus? Reviewers who had agreed to do write-ups about the book are still waiting for their “advance” copies. Closer to home, one of the bookstores where I have an upcoming event ordered my book two weeks after the pub date, which (briefly) made me rethink my call for buyers to “shop local.” (After checking in with two different sales clerks, I got a nice note from the owner explaining the oversight—“For some reason, the order was coded as backorder cancel, and since it was not yet released it did indeed cancel.”) Whatever the hell that means.

These snags and others—none of them big deals, but still—reinforced that it was up to me to pay attention and be proactive in helping to address any problems.

2. Expect crickets. A bazillion new books come out every day, and the day after that, and after that, all of them clamoring for their own parade. So when I didn’t receive congratulatory notes about my new book from some of my closest friends, or those writing students whom I have taught and nurtured, sometimes for years, well, of course I understood. People are busy with their own lives, their own writing projects. You can’t just stop everything to, say, dash off an email, no matter how much it would mean to that friend or teacher. That’s why I’d like to tell all those people in my life who have yet to acknowledge my new book the same thing my mother often said to me, which always had the desired effect: “I’m not mad…just disappointed.”

3. Expect to fall back in infatuation. By the time I’d finessed every sentence of my manuscript, then reviewed the copyeditor’s notes, then proofed the page proofs, then made a few more tweaks (a no-no after page proofs but you can’t just unsee a word you don’t like), then re-proofed the page proofs (a necessity, thanks to all my last-minute changes), there was one thing I knew for sure. I was sick to death of my book! But then it went to print and a couple months passed and the actual book arrived in stores. Tentatively, I opened a copy to a random essay and started reading. Who wrote this? I thought. My gosh, I like this writer!

4. Expect to find a typo. Miraculously, I have not found a typo in my new book…yet. (Refer back to my comment about proofing and reproofing.) But of course just putting this brag in writing means that now the cosmos is going to plant a typo somewhere in the collection, and one thing I know I can expect is that I will hear about it from some punctilious, well-meaning reader.

5. Expect unexpected reader responses. Like this response from a lovely woman who wrote to tell me she LOVES my book. “Why?” she clarified in her email, “Because I can read it out of order just like I read the Bible!” In addition, despite my misguided belief that this was a book primarily for women, several men have surprised me with thoughtful appreciations. And then there was this response from a formidable academic who told me over breakfast, “I got your book. I wouldn’t have chosen that color for the cover.” And…I thought, expecting a bit more of a reaction. But that was all she had to say, which was unexpected but perhaps for the best, given how this woman terrifies me.

Bookshop • Amazon

Bookshop • Amazon6. Expect to find your happy place in one of the least expected places. I’ve delighted in the arrival of every email from someone who applauds my book. I’ve basked in the glow of a good Amazon ranking, however fleeting. And how fun it has been to blab about me, myself, and I during book events, and on a variety of podcasts and author interviews. But those temporary highs can’t compete with my real happy place, which—surprise, surprise—is still at my desk, working on my next collection of essays, while my cat rests her head on the edge of my keyboard.

7. Expect to let go of any expectations. As a bit of a control freak, at least when it comes to my work, I have reluctantly accepted this lesson. But even I can understand that if you rid yourself of expectations, then you don’t have to feel disappointed or hurt when they aren’t met. On the other hand, well, you just never know, which is why I’m still holding out for a parade. So cue the marching bands, fire up the floats, and start blowing up lots more balloons!

October 25, 2023

First-Page Critique: How to Elegantly Reveal Character Motivations

Photo by Alice AliNari

Photo by Alice AliNariAsk the Editor is a column for your questions about the editing process and editors themselves. It also features first-page critiques.

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Plottr. Ditch the index cards and unleash your storytelling with Plottr – the #1 rated book outlining and story management software for writers. Use code JANE15 at checkout for 15% off. (Expires Dec. 31, 2023)

A summary of the work being critiqued

A summary of the work being critiquedTitle: The Siren Dialogues

Genre: Literary fiction

When Libby Levine is assigned a story on renowned photographer Tanner Bixby, she sees an opportunity to prove her writing chops and win a promotion. As a bonus, the photographer has a vacation cabin on the same island as her boyfriend, Jasper. But Bixby has a surprise agenda: he’s looking to find the long-lost love of his life—who he claims is a mermaid.

When a mysterious, half-conscious woman washes up with the tides, Libby forms an inexplicable bond that challenges what she knows about herself as well as her past decisions and true loyalties. With the arrival of a hurricane, the woman fully awakens and reveals her true nature. And Libby must summon all her power to choose who and what she wants to become and who she’s willing to betray, or run the risk that someone else might choose for her.

From the writer: I’ve had questions whether to present this as literary fiction with magical realism or magical realism with a literary bent. I’ve also wondered if beginning the book with a duck hunt is off-putting to some readers? This is a book that has gone through many iterations over multiple years and I am anxious to get it into the world! Are the character motivations clear? Is the voice engaging? These are some of the big questions I have.

First page of The Siren DialoguesLibby

Libby angled her flashlight beam over Jasper’s tall, lean frame and the wagon load of decoys and gear bumping along the boardwalk behind him. The beam caught the eyes of one of the decoys, a mallard duck carved from wood, bringing it to life just as a warning gong echoed from a buoy and a ship in the distance issued a long, low response. The early morning hour was alive with sound and magnified over the body of the bay. Even her new duck boots made a satisfying slap against the wooden boards. She turned up the collar of her field coat and patted the pockets. Notebook on one side, gloves on the other. She’d need both to capture the day.

Normally she kept her work and personal lives separate. Elizabeth in the city and Libby on the island for her weekend escapes to Jasper’s cabin. This time was different. Soon her new client, the famous photographer Tanner Bixby, would arrive. She would chronicle his stories for a new photography book and give context to his vision. Her boss, Diane, was taking a chance on her and she planned to come through.

Jasper dropped the wagon handle at the dock and hopped into his boat. He switched on the running lights and the engine hummed to life. His was the last craft left in its slip, all the summer people gone back to the city and their boats put in dry dock. He grasped her by the wrist as she stepped from land to water with only the floor of Jasper’s boat between them. Her blood thrummed beneath Jasper’s long fingers. “Easy does it, Libs,” he said.

She squeezed before letting go and settled on the gunwale. Port side, she reminded herself. Port left red like Port wine. Starboard right green. She looked over the side to see if she’d gotten it right and there was the red blaze of the navigation lights in confirmation. The truth was, she was glad this trip would be different. She’d been with Jasper over a year now. Maybe it was time to shake things up.

Continue reading the first pages.

Dear Lisa,Thank you for submitting the first several pages of your novel for a critique. I’m especially intrigued by your subject matter. Back in 2020, when The Washington Post noted that “mermaid mania is coming around to books again,” I wondered if it would wane. Instead, interest has grown, and mermaids are featured in several new books for readers of all ages, at least according to HuffPost. To be competitive in the current publishing market, you’ll likely need a progressive twist on the mermaid (or siren) archetype. If The Siren Dialogues is anything like the comparative title you mentioned, Julia Langbein’s well-reviewed American Mermaid, then you are in a strong position.

Opening your novel with a duck hunt is also, in my mind, a plus. Although some agents and editors might be opposed to the idea of hunting in principle (this one included), it is an American pastime. And while I can think of a few contemporary books that depict some form of hunting (C.J. Box’s novels, Helen Macdonald’s heart-wrenching memoir H Is for Hawk), none come to mind that are about duck hunting, specifically. If your novel is set in a region where hunting is common, or if your novel could be considered historical fiction, then you would be justified in leaving it intact.

My bigger concern about the opening is that the exposition may be getting in the way of the action. Your pitch clearly explains that Libby is embarking on a duck hunt with her boyfriend, Jasper, and photographer Tanner Bixby, whom Libby is to interview for her work. But in your pages, this information becomes blurred, due in part to such descriptions: “The beam caught the eyes of one of the decoys, a mallard duck carved from wood, bringing it to life just as a warning gong echoed from a buoy and a ship in the distance issued a long, low response.”

This line is wonderfully evocative, but it’s also on the long side, and it’s the second line in the book. If the wooden duck isn’t relevant to other events in this scene, and if it isn’t meant to symbolize other inanimate creatures that later come to life, then might this sentence be trimmed or removed?

The boardwalk might not be necessary to mention here, either, since it comes up later in the chapter when Libby hears Bixby’s footfalls pounding the wooden boards. In fact, the first paragraph might work just as well if Libby and Jasper are already on the boat rather than preparing to board it. This setup would enable you to focus on how Jasper is waiting for his friends while Libby is anticipating the arrival of Bixby.

Aside from streamlining the opening paragraphs, I would encourage you to better integrate some of the boating terminology into the story so that it sheds more light on Libby’s motivations. For example, did Libby get “settled on the gunwale” because she believes that sitting on the upper edge of the boat will give Bixby more space to spread out? If so, then it’s no wonder that she is startled when he later “plopped down next to her, upsetting the boat’s balance.”

Or you could have Libby reflect on the day that Jasper taught her the difference between “port” and “starboard,” how the glass of wine he handed her helped her remember, “Port left red like Port wine”—if this is at all accurate? If not, perhaps she can be upset that he’s never explained to her why metal wings are positioned below the hull and aft wings, how he acquired his Russian Volga hydrofoil—or why he enjoys hunting an animal that she could never harm?

If it’s true that Libby once said hunting is “cruel and unusual punishment,” as Topher later reminds her, then you might briefly delve into why she’s seeing Jasper, if they have conflicting beliefs. (Such an explanation would have the added advantage of addressing your concern that some readers will find the duck hunt off-putting.) The line at the end of the fourth paragraph about how Libby has been with Jasper for a year and “it was time to shake things up” makes for a terrific cliffhanger, but right now it’s unclear how Libby feels about him and what kind of change she has in mind.

Another way to further strengthen the opening is to reassess when to bring in the siren. Currently, the point of view switches from third person narration about Libby to the siren’s first (and second) person narration rather suddenly, just as readers are just getting to know Libby. Assuming that you’ve chosen a dual narration for the novel that alternates between Libby’s and the siren’s point of view, it should be easy enough to space out their sections, bringing in the siren sometime after the last line of this excerpt, when Libby declares that she’s “hungry and ready for anything.” Until then, you could potentially foreshadow the siren’s appearance by incorporating a few more light touches of magic to Libby’s section. For example, maybe she notices something inexplicable moving about in the bay, or that the early morning moonlight has a silver glow? The delightful passage later in the chapter, about the “salve that washed away the residual layers of [Libby’s] city self” and how Libby “loved … letting go of one self and embracing the other, as if she were a mythical creature transforming to its true nature,” should make for the perfect lead-in to the introduction of the siren.

As for your question about whether to present this as literary fiction with magical realism or magical realism with a literary bent—perhaps you don’t need to include either descriptor? Since you say that your novel is written in the vein of Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being, the recipient of numerous literary awards, agents will assume that your work is literary as well. What would be more helpful is to indicate how your writing is similar to Ozeki’s, whether in terms of setting, theme, or tone. The other comparative books you’ve chosen, coupled with your title, suggest that your work is speculative. Since “magical realism” is often associated with contemporary Latin American writers, maybe it’s best to avoid this term, focusing instead on the “magical elements” of your novel? Your many impressive publications and accolades, including your Pushcart Prize nomination, also speak volumes about your craft. Be sure to mention them in your bio, as they are certain to garner interest from agents.

Best of luck!

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Plottr. Ditch the index cards and unleash your storytelling with Plottr – the #1 rated book outlining and story management software for writers. Use code JANE15 at checkout for 15% off. (Expires Dec. 31, 2023)

October 24, 2023

How to Use Brain Waves to Enhance Your Writing Practice

Photo by DS stories

Photo by DS storiesToday’s post is by writer, speaker and coach Lisa Cooper Ellison. Join her on Thursday, October 26 for the online class The Psychology of Memoir, Part 3: Completing Your Book.

Insights are the juice of a writing life that take us from not knowing to a god-like understanding of our stories. They feel like a lightning striking inside you and often cause you to say things like a-ha and that’s it!

While you can’t crack your head open and press the insight button, you can set the stage for insights to happen, and for you to do more organized, heads-down work.

To get started, let’s look at how your brain waves work.

Brain waves 101Your brain’s neurons emit electrical waves as they communicate with one another. The five brain waves, from slowest to fastest, are delta, theta, alpha, beta, and gamma. Understanding which ones support specific writing activities can not only enhance your writing life, it can prevent you from unwittingly robbing yourself of that precious juice.

Delta (1–4 Hz) is the slowest brain wave pattern. In adults, they occur during deep, dreamless sleep. When you get adequate deep sleep, you feel refreshed, focused, and ready to take on the day. Good sleep hygiene, which includes things writers might begrudge, like limiting caffeine after 2:00 p.m. (the horror!), shutting off electronics that emit blue light two hours before bed, and setting a regular bedtime, can improve how much deep sleep you get.

Theta waves (4–8 Hz) are the second slowest. They occur during REM sleep and play an essential role in memory formation. They also occur on the edge between sleep and awakening, and are sometimes seen as the gateway to the subconscious. This wave state is associated with creativity, intuition, daydreaming, and fantasizing.

Alpha waves (8–14 Hz) occur when we’re in a state of wakefulness but not really concentrating on anything. When your brain emits a healthy level of alpha waves, you’re more likely to feel relaxed and in a positive state, two things needed for insights to happen. According to neurofeedback practitioner Jessica Eure, “A healthy, robust alpha frequency allows us to tune in to ourselves and tune out the external world a bit while still being fully awake. This allows us to visualize things in our mind’s eye.”

Alpha and theta brain states are great for gathering ideas, making unique connections, or tuning in to what your subconscious has to say. That’s why Julia Cameron encourages writers to not just write in the morning, but to write as soon as you wake up. A groggy mind has access to those theta waves.

Beta waves (14–30 Hz) are fast and active. They occur when we’re in the wide awake state needed for focus and concentration. Harnessing your low beta waves (12–15 Hz) can help you organize your thoughts and increase your productivity. But sometimes we have too much beta, or the beta brain waves we experience are at higher frequencies. High beta states (14–40 Hz) are associated with stress, irritability, anxiety, worry, insomnia, racing thoughts, and being jumpy and hypervigilant. When we’re operating in high beta, the busyness of the brain can make it harder to focus.

Gamma waves (40–120 Hz) are the fastest of your brain waves. They coincide with periods of intense learning, problem solving, and decision making. They also appear alongside alpha and theta during states of flow.

Many factors affect the composition of our brain waves, including genetics, head injuries, illnesses, trauma, stress, and even the medications we take. You can’t reprogram your brain to have more or less of a specific brainwave without treatments like neurofeedback or strict, often hours long, meditation practices, but you can make the most of what you have by engaging the right brain waves for the appropriate writing task.

Capitalizing on your brain wavesFor your brain to function properly, you need to take good care of it. According to Eure’s colleague, Dr. Rusty Turner, “The best things we can all do for our brains are exercise, eat well, disconnect from technology, and have good sleep hygiene.” That’s step one. Next, try to engage the brain waves best suited for your writing session.

If you’re generating new material, spend some time in your upper alpha or low beta brain wave states. This happens when you’re relaxed and feeling both wide awake and focused. (More on how to do this in a minute.)

After generating and revising that new material into something that makes sense, you’ll need to figure out what it means, why it’s significant, and how it connects to other things you’ve written. You can’t force these insights to happen by poring over your work. That’s because the more you focus on a problem, the more you worry about it, which engages your high beta waves. Instead, step away from your work and focus on engaging your alpha waves, with the occasional help from theta. This is where morning pages can come in handy. While Julia Cameron sees them as an emptying of the trash so you can get to real writing, giving yourself permission to wander into story territory soon after waking might help you solve your work-in-progress’s biggest problems.

Meditation is often touted as the way to prep your brain for writing. That’s because meditation calms the brain and encourages alpha and theta wave brain states. But meditation doesn’t work for everyone. In fact, it can be detrimental to trauma survivors and can feel like failure for anyone whose brain has a lot of spindly high beta waves.

If this is you, skip the meditation and instead focus on breathing activities like alternate nostril breathing. This exercise will engage the parasympathetic nervous system, which helps with the formation of alpha waves. Other activities that can help you engage in alpha wave states include warming your hands and feet, getting a massage, taking a shower, and walking in nature.

For editing activities that require a high level of wide-awake focus, give your low beta waves free rein. If you’re getting enough sleep, all you’ll need to do is take a walk, especially on a brisk day, to wake your brain up.

If you’re working on a large-scale problem that requires deep focus, gamma waves are your ally. While the best way to access them is sustained long-form meditation, there’s a hack you can use to access this and other brain states: binaural beats.

Binaural beats are two tones set to specific frequencies, or hertz, that you listen to simultaneously. Studies show that listening to binaural beats can help you temporarily access specific brain waves, though this doesn’t teach your brain to go there on its own.

While you can purchase a binaural beat app, a simple YouTube search will give you plenty of options. To see if binaural beats are right for you, do the following:

Grab a set of stereo headphones.Choose a playlist set to the frequency best suited to your task.Listen for approximately 30 minutes while you’re doing a set task.Notice how you feel. If it’s helping, keep it up. But if you feel agitated, unfocused, or depressed, that doesn’t mean you’re doing it wrong. It just means that frequency isn’t right for you.I personally like binaural beats set to music, though others feel best when all they hear are the specific tones. Mixing it up helps me maximize my brain waves and harness those juicy insights that keep me at my writing desk. My current favorites are this gamma wave mix for hard core editing, and a dreamier cognition enhancer when I want to find the stillness needed to create new work. If you give this a try, leave a note in the comments to let me know what you discovered and how this affected our writing process.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Thursday, October 26, for the online class The Psychology of Memoir, Part 3: Completing Your Book.

October 19, 2023

Why I Prefer to Read Fiction without Lessons or Messages

Photo by Steve Johnson

Photo by Steve JohnsonToday’s post is by writer, podcaster and editor Wayne Jones.

In an episode from the second season of The Simpsons in, yes, 1991, Homer hopes that allowing Bart to donate his rare blood type for a transfusion to save Mr. Burns’s life will result in a substantial financial reward. When they receive only a thank-you card, Homer writes an angry letter to his boss, who ultimately does reward them—but with a huge Olmec god’s head carving that of course is of no practical value to the family. A debate ensues about the moral of the story, but Homer concludes there isn’t one: “It’s just a bunch of stuff that happened!”

I feel the same way, though not dismissively like Homer. I don’t read fiction to be taught anything. For sure, there may be things in fiction that depict the way things are (or should be) in the world, but if that seems like the author’s main purpose, then for me it’s a hard no, as the kids say.

What I want in fiction is a virtuoso demonstration of the use of our messy, malleable, beautiful language. I want to see clichés avoided and in their place fresh, strong, exuberant images and descriptions and stories. I want the author to pay attention to how they are saying something even more than to what they are saying. One of the characters in the great short novel Lord Nelson Tavern (1974) by Canadian writer Ray Smith dismisses Jane Austen because all she wrote about were “the absurd concerns of silly small-town girls in England around 1800.” Another character disagrees, because regardless of subject matter, the important aesthetic for Austen was that everything was “closely observed and accurately rendered.” Again: it’s not the what that counts but the how.

Perhaps the icon in defending fiction lacking messages is the great American writer Vladimir Nabokov, who chose to push back against ridiculous claims made about his character based on some people’s reading of Lolita (1955). Modern editions of the novel now generally include an afterword, “Vladimir Nabokov on a Book Entitled Lolita,” in which he states:

There are gentle souls who would pronounce Lolita meaningless because it does not teach them anything. I am neither a reader nor a writer of didactic fiction, and despite John Ray’s assertion, Lolita has no moral in tow. For me a work of fiction exists only insofar as it affords me what I shall bluntly call aesthetic bliss, that is a sense of being somehow, somewhere, connected with other states of being where art (curiosity, tenderness, kindness, ecstasy) is the norm. There are not many such books.

No morals, no messages. The John Ray whom Nabokov refers to is the fictional writer of the foreword to the novel, who says the exact opposite of what Nabokov believes: “for in this poignant personal study there lurks a general lesson … ‘Lolita’ should make all of us—parents, social workers, educators—apply ourselves with still greater vigilance and vision to the task of bringing up a better generation in a safer world.”

A few weeks ago I began re-reading the short stories of another great American writer, Raymond Carver, whose fiction was published mostly in the 1980s and 1990s (the movie Short Cuts is based on his stories). There isn’t much that’s offensive in the subject matter of Carver’s writing, and certainly nothing close to pedophilia, but there’s also not a single lesson to be found in or between the lines of his extremely spare prose. There are scores of examples. “Kindling” (1999) is about Myers, a man “between lives,” who rents a room in a couple’s home. The story presents the interactions of the three of them as well as the daily routine of the couple, which Myers adapts to. He starts writing things in a notebook, and the story ends after he writes an entry, and: “Then he put the pen down and held his head in his hands for a moment. Pretty soon he got up and undressed and turned off the light. He left the window open when he got into bed. It was okay like that.”

That’s all. Whether this story has a message or a theme depends, I suppose, on your attitude toward fiction, whether you need it to say something in order not to be pointless. I could imagine a reviewer talking about the “theme of adjustment” or the “strong message about resilience and adaptability.” For me, though, these just seem like so much contrived aggrandizing, and I cringe at how such reductions always risk ignoring the real beauties of the story: the tone and pacing, the carefully chosen dialogue, the portrayal of character in just a few actions or words, and so on. I see an analogy in how some people view abstract painting. They ask what it means. Or they say that they can see this or that item from real life in it, just as you might see clouds form something that looks like a face or a teapot or the shape of Newfoundland.

The lack of messaging is not just a hoary technique of the past. The young American writer Tessa Yang, author of the short-story collection The Runaway Restaurant (2022), says in an interview that she doesn’t “write fiction with morals or messages in mind,” and the subject matter is about as far removed from Raymond Carver as you could imagine. In “Night Shift,” a young woman takes a pill to try to keep herself awake, and soon she’s talking to a small green dragon who’s sarcastic and tells bad jokes and riddles. But there’s no “just say no” and no “moral in tow.” Pretty much the entire collection is like that.

When I was a student at the University of Toronto in the early 1980s, I took a course from Northrop Frye, a self-effacing scholar who had read pretty much all of Western literature and made a name for himself with his book Anatomy of Criticism (1957). I was a shy guy then in my early twenties and during the whole term had the courage to ask him only one question, but the answer stuck with me. I forget the details, but he made the distinction between writing (like nonfiction) which is a “structure of belief” and literature, which is a “structure of the imagination.” I still make that distinction. Fiction, short stories, plays, whatever—they are not works which aim to make you learn or believe in something real. Instead, they follow the open and very broad “rules” of the imagination. The skill of the writer can transform just a bunch of stuff that happened into something pretty beautiful.

October 18, 2023

What It Means to Make Your Story Relatable

Photo by Aleksandr Barsukov on Unsplash

Photo by Aleksandr Barsukov on UnsplashToday’s post is by author and educator Deborah Williams.

If you’re a serious writer, chances are good that you have a battered copy of Anne Lamott’s Bird By Bird on your shelf (or, if you’re like me, maybe you’ve committed large chunks of it to memory). But when my first-year college writing students read Bird by Bird, they’re almost always coming to the book for the first time.

Because I’ve taught approximately eighty-gazillion first-year writing courses over the course of my teaching career, I can pretty much predict how the students will respond. Many of them (particularly the international students) will be bashful about the chapter called “shitty first drafts,” because they’re anxious about saying “shitty” in front of a teacher. Many of them will feel deep kinship to the chapter on “Perfectionism” because they got into college (for the most part) by being good at school—and that requires a certain level of Type-A behavior.

“It’s like I feel so seen,” someone will say, to which their classmates will nod in vigorous agreement.

“I can just totally relate,” someone else will say.

That’s when I pounce: “You can relate? You feel connected? How many of you are sixty-something, born-again Christian, recovering-addict, single-mother, dreadlock-wearing white ladies from Northern California?”

They laugh. They’re pretty emphatically not any of those things. They’re eighteen and nineteen, from any number of countries and across the United States, and they probably won’t take another writing class after this one (which is a required course). Almost none of them want to “be writers”; in fact, most of them are headed towards majors in STEM or business.

These “relating” moments demonstrate to my students (and to me, again and again) that connection gets established in the nitty-gritty, in the small nuggets of lived experience. Sure, we all feel love, anger, joy, anxiety—but we recognize ourselves in the particulars. When Lamott describes her anti-writing voices, for example, she characterizes one of those inner critics as a stoned William Burroughs, who tells her that she’s “as bold and articulate as a houseplant.” The description makes me and my students laugh in recognition: “I thought I was the only one who felt that way,” one of my students said. Lamott’s specificity comforts us—we are not alone—even if, like my students, you have never heard of William Burroughs.

I ask my students to show me their “I can relate” moments and then we focus on how that sentence or that section works. Those moments don’t happen by magic, I say; those moments get made. They’re a product of craft. (Okay, and a tiny bit of magic.)

Here’s what we discover, again and again, when we talk about Bird by Bird.

Pour the concreteLamott uses concrete, tangible nouns; Bird by Bird is a master class in “show, don’t tell.” Readers watch as she procrastinates by peering at herself in the mirror to see if she needs orthodontia; we share her pain when she talks about recovering from a tonsillectomy. Even the title of her book comes from a concrete moment: her brother, then in middle school, freaks out about a report on birds that was (of course) due the next day. Her father’s advice to him? Take it bird by bird. She builds on her brother’s freak-out with her own experiences, using the example of writing restaurant reviews for a now-defunct magazine: “I’d write a couple of dreadful sentences, xx them out, try again … and then feel despair and worry settle on my chest like an X-ray apron.”

Panic as a lead apron: who doesn’t recognize that feeling?

Action!As the students point out relatable moments, we look at Lamott’s verbs. Yes, she uses some forms of “to be,” but more often than not, she uses one-word action verbs. Action verbs are like Spanx for your prose: they tighten, streamline, hold it all together; they provide visual cues that preclude the need for adverbs. Stephen King, famously (adverbially) insists that the road to hell is paved with adverbs. Allison K Williams, in Seven Drafts, suggests using adverbs only if the adverb provides some quality of surprise: yelling quietly, or smiling angrily, for example. The distractions that bedevil Lamott before she sits down to write turn her into “a dog with a chew toy, worrying it…chasing it, licking it … flinging it back over my shoulder.” Now, I’m not a dog owner, but I can see all this happening—and I connect it to my own urge to do all the laundry when I’m on a deadline.

You talkin’ to me?Throughout her book, Lamott refers to “we” and to “us” almost as often as she uses “I.” The people she’s talking to are writers and students of writing; she’s not talking to her church community, or to members of AA, or to the PTA. Who is your “we” to whom you’re trying to relate and how can you make that clear? Are you talking to other parents? Survivors of a trauma? Writers? Teenagers? As much as we writers might hope and wish and imagine that our words are for everyone … probably they’re not. Thinking about your “we” is going to help you think about how to craft concrete moments that will bring your “we” into your prose.

And who are you?In thinking about the “we,” it can be tricky to determine how much to divulge as the narrative’s “I.” My students often say that a key “relatable” element comes from Lamott’s willingness to make herself vulnerable—showing us how she wrangles to stay focused. “I never feel like she’s scolding me,” one student said. And yet, even as she’s making herself vulnerable, Lamott makes clear that she’s writing from years of experience. She knows enough about herself as a writer to trust her own process and as a result, she gives us permission to find and then trust our own processes.

What level of disclosure feels right to you? Can you push that boundary just a tiny bit further, to the very edge of what seems possible? It’s at that tipping point, often, that we find those moments of connection that make reading so powerful. Even if you’re writing fiction, knowing your own vulnerabilities can make your characters and your scenes that much more resonant.

In writing memoir, that level of vulnerability and disclosure gets trickier, because your story probably involves other people who might not want to be revealed. Lamott, again, has an answer, which is that if people wanted you to write nicely about them, they should have been nicer to you. It’s a flippant response—but is she wrong?

Relatable doesn’t mean likeableThere are always a few students in class who find Lamott’s humor aggravating; they say that she makes them feel stupid. They admit that some of what she says resonates, but they don’t like her.

Their response raises a question: do we need our characters to be “likeable”? (I’m going to sidestep the entire issue of whether anyone ever asks this question of male characters, or male writers, for that matter.) Think about characters you’ve encountered who resonated with you. Was it because they were paragons who always made the right choices? We might think that what we want when we read are role models, but reading about role models often makes me feel like I’m reading a lecture or a sermon; to use my student’s word, I feel scolded. Connections emerge in the struggle, in moments of transition, as a character tries to chart a new path. That’s where we find recognition, connection, and exploration.

In the novel I’m working on, the central character is a fictionalized version of a (long-dead) writer whose work I’ve admired for years. It’s hard not to make her do everything right, because I don’t want my literary hero to make mistakes. But the story exists, I remind myself, in her stumbles. That’s where I have to locate my action.

Zoom inThink about a trip you took where you ended up with a bunch of snapshots of bridges, buildings, trees, and landscapes in your photo roll. Those are pretty pictures, sure, but after a while, they all blur together. Was that the beach in Maine or the beach in Maryland; was that pretty tree in San Francisco or Japan? Put a few people in the photo and suddenly it’s a story, one that we can write for ourselves even if we don’t know the people involved: those kids are too close to the edge of the waterfall! I would look better in that dress! We hiked that same trail!

That’s not to say that your writing (or your IG posts) shouldn’t have moments of reflection and stillness, which I’ve started calling “zoom out” moments for my students, who have grown up amid the endless digital/visual stream. Too many of those, though, and we’re looking at your story from a drone’s sky-level view, like a David Attenborough nature documentary that never hones in on the snow leopard and her kits.

Where to zoom out? That depends, in some ways, on how you choose to define your “we.” Your audience will need different types of zooming out, different levels of generalization and abstraction. Lamott talks to us as if we’re all in her writing class; we’ve been invited into that room, as it were, and so her levels of abstraction are all designed with the aim of helping novice writers become more confident. When we trust our own process—when we recognize that we have a process—the little procrastinatory moves, the shitty first drafts, the vexed question of how to make our perfectionist selves be quiet, all become easier to handle. Her abstractions, and then her specific and vulnerable scenes of her own struggles, help us to recognize ourselves so that we can get our words—ourselves—onto the page.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1885 followers