Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 44

August 23, 2023

How Can I Convince Editors That My Information Can Be Believed?

Ask the Editor is a column for your questions about the editing process and editors themselves. It also features first-page critiques. Want to be considered? Submit your question or submit your pages.

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Book Pipeline. Late deadline: September 5th for the 2023 Book Pipeline Unpublished contest. Awarding $20,000 to authors across 8 categories of fiction and nonfiction. Multiple writers have signed with top literary agents and been published. Use code Jane10 for $10 off entry.

Question

QuestionI am facing writing a query letter about a topic that many have written in. I am making some very bold statements/claims—it’s true crime [about a serial killer]‚ and I worry those claims will ring with editors as “Oh great, another guy claiming he’s solved this!” Because of overwhelming evidence, I have absolute certainty I am correct, but getting editors to even be receptive is my concern.

—A Writer’s Writer Righting Wrongs

Dear Writer’s Writer,My colleague Allison K Williams often advises writers: If there’s a big, glaring obvious issue with your project or your submission, then “tie bells on it.” In other words, don’t try to hide the problem or pretend the issue doesn’t exist. Address it upfront. Show self-awareness about the challenge and (just maybe) how this could be a strength or selling point.

In the very first paragraph of your query letter, you’ll say something like, “Ever since such-and-such year, thousands of sleuths say they’ve solved [famous serial killer case].” Then you might point to the most recent/popular documentary or article that has recently discussed the case, or gotten the case entirely wrong. This should take about a paragraph.

In the second paragraph, you’ll introduce your book as the definitive solution to the case because of new evidence or research, or whatever sources/access you have that no one else has. This is important for a successful pitch. If this true solution is based on nothing but your armchair musings, editors will indeed have a hard time taking you seriously. Maybe you could get away with it by pointing to some fact that literally everyone else in the world has missed, or a consistent misinterpretation of some kind. But it needs to be a stunning twist or reversal that, let’s hope, is easily understood or explained, because disbelief will take over with lightning speed.

In your other notes submitted with this question, you mentioned, without elaborating, that you are held to a strict non-disclosure agreement. I hope you meant that in regards to submitting your question for this column, and not an NDA that would affect your ability to effectively pitch the book. Editors and agents have little tolerance for authors who play coy at query stage with what they know. They can’t reasonably evaluate a project without you putting all your cards on the table. At the very least, you have to give enough information in the query or book proposal to look credible, and perhaps an agent would be willing to have a phone conversation about how to proceed if you truly have sensitive information.

Unfortunately, most writers I encounter who insist on an NDA or who are working under an NDA never make it to traditional publication. A desire for an NDA can be fundamentally incompatible with the traditional publishing process, and there are precious few people who can insist on secrecy or NDAs—Prince Harry, politicians, or certain celebrities, for example. But these people typically have lawyers on retainer or agents working on their behalf that are accustomed to their special needs, and know how to shepherd them through the publishing process so that everyone is happy.

If you’re an “average” or unknown author? The general response to an NDA will be silent eye-rolling. Agents and editors have seen just about everything under the sun, and you’re not likely telling them anything they haven’t heard before. Your notes mention you’re a co-author on the project, so perhaps the NDA is somehow related to that other person? If so, that puts you in a very difficult position that will likely impede progress.

Finally, your notes also mention that you might need to self-publish due to the sensitivity of the information. Here’s the thing, though: If you’re seeking some level of acceptance or attention from the mainstream media and if you want to achieve the highest possible credibility, then self-publishing may only further reinforce the notion that your information can’t be trusted. While traditional publishing is fallible and notorious for not fact-checking, the top publishers (big and small alike) do exercise some level of quality control. The sales, marketers, and publicists have to be able to pitch the book with some level of confidence or belief in what they’re peddling. And publishers regularly get eviscerated by readers and the media if they put out a book that’s considered harmful or that can be blatantly disproven. (Just see what happened here.)

Self-publishing a book on a well-known serial killer, with the true solution no one’s heard before, will most likely get you shelved with conspiracy theorists and snake-oil salesmen—if the book is discovered at all. The sensitivity of the information shouldn’t affect how you publish. Traditional publishers deal with sensitive information all the time. If this sensitive information can be verified or if you can prove beyond a reasonable doubt that your true solution holds water, then editors and agents will give you fair hearing. But you have to give them the ability to consider your evidence upfront if you want to be taken seriously.

—Jane Friedman

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Book Pipeline. Late deadline: September 5th for the 2023 Book Pipeline Unpublished contest. Awarding $20,000 to authors across 8 categories of fiction and nonfiction. Multiple writers have signed with top literary agents and been published. Use code Jane10 for $10 off entry.

August 22, 2023

Explore the Fictional Character That You Present to Readers

Photo by 愚木混株 cdd20 on Unsplash

Photo by 愚木混株 cdd20 on UnsplashToday’s guest post is excerpted from the new book The Writer’s Voice: Techniques for Tuning your Tone and Style by Anne Janzer (@AnneJanzer).

In December 2022, the New York Times challenged several children’s authors and writing teachers to identify whether ChatGPT or human 4th graders wrote a collection of essays.

The experts could not always tell the difference. Nor could I. Many of us find that unsettling.

When we read, we form an image of the narrator as a human being. With good fiction, characters come to life in our heads. Even when we encounter writing from a “brand” or a chatbot, it’s hard to resist giving it a personality. (I thank automated help chatbots when they answer my questions.)

Your readers probably don’t know you personally. As they read your words, they interpret your voice and create an idea of the person writing those words. They construct an image of you that is, in a sense, a fictional character.

Even the most dedicated journalists, memoirists, and professional writers engage in a type of fiction: the way they portray themselves in print. When we write in our own voice, we present a curated version of ourselves. The complete self would never fit.

We do this almost without thinking. In my survey about writing voice, two-thirds of respondents reported writing in a professional voice for a portion of their work. No doubt they sound different when writing fiction, personal essays, journals, and emails to friends and family.

What happens if we think of ourselves as fictional characters—even if we write nonfiction? Could this increase the fluidity of our writing?

Here are three exercises you can use to explore the fictional character you present, even if you write nonfiction.

Sketch your characterIn this exercise, you’re going to sketch a brief character profile of the narrator (which might be you) as that persona relates to the work at hand.

If you write in your own voice, remember that you present only a specific slice of yourself on the page—the one the reader needs. If you write fiction with an omniscient narrator, that persona still has a point of reference, a lens on the world, and a distinct voice.How about memoir? Isn’t that really you on the page? Yes, although it represents you at a specific time of life. So, draw a quick character profile of yourself at that time, as related to your memoir’s theme. Your entire life won’t fit.

This isn’t the bio that would appear on a book jacket, filled with your credentials—leave that for another time. You’re trying to capture the personality you hope to project in the writing voice. You can do that in a few short paragraphs.

Keep the writing in the third person so you can zoom out and get perspective.

Remember, you don’t have to show this to anyone.

As you do this, consider:

What can you do with the insights from this exercise?Does this shape ideas about what you want your writing voice to be?Pick 3 adjectivesHere’s a useful marketing trick. Pick three adjectives that you would like to embody in your writing. They can be anything: smart, expert, funny, compassionate, nerdy, whatever. The options are nearly infinite—and that’s the fun of it.

You can only claim three, so choose carefully. You’ll be lucky to communicate two consistently.

Now choose one of your adjectives and take it to an absurd extreme. For example, one of my adjectives is curious. If I went overboard, I might write an email like this to friends:

Remember that we’re getting together Saturday for wine tasting at 6pm at Pat’s place. I wonder what wines everyone will bring—and if there are any great tasters in our midst. I read a book by a Master Sommelier, and it includes a tasting grid. Does anyone want to try it with me? Maybe we should make it a blind tasting and see how our different senses compare. Is anyone planning to spit out the wine? And what’s the best food to accompany wine tasting? I’ll do some research and bring a snack that works well.

(See how annoying it can be to go too far?)

Try going overboard with one of your own adjectives. Either write a paragraph or two on a current project or use the following prompt: Write an email to friends about a gathering on Saturday.

Having tried the extreme, consider how far you usually go on this spectrum. Does your writing show up displaying the voice you want? Too much or too little of it?

Try on another characterPick a favorite fictional character—one you know well and that you can inhabit easily.

Choose characters with distinct voices. For example, if you love reading mysteries, pick your favorite sleuth or detective: Hercule Poirot, Sam Spade. Consider any of the Harry Potter characters. Or, try on a movie character.

Put them to work writing for you. How would Snape write that email? How would Yoda begin your blog post?

For example, I tried asking Poirot to describe my favorite hike, and he just complained about his shoes and the lack of a tisane.

Bookshop • Amazon

Bookshop • AmazonIf you don’t have a writing project in mind, use this prompt:

Write about a specific place you love from the perspective of your chosen character, who may or may not love it.

Pay attention to what you learn from writing in another voice.

Was it fun to write in an unfamiliar voice?Did writing as another character shift your perspective? For example, if you used the prompt, did it make you consider the place again through a new lens?Are there elements of that character’s voice you might call on in the future?August 20, 2023

How AI-Generated Books Could Hurt Self-Publishing Authors

Just two days after the Maui wildfires began, on Aug. 10, a new book was self-published, Fire and Fury: The Story of the 2023 Maui Fire and its Implications for Climate Change by “Dr. Miles Stones” (no such person seems to exist). I learned about the book from this Forbes article, but by then, Amazon had removed the book from sale. Amazon had no comment for Forbes on the situation.

Curious about how far the book might have spread, I did a Google search for the book’s ISBN number (9798856899343). To my surprise, I saw the book was also for sale at Bookshop and Barnes & Noble. I tweeted about the situation, noting that IngramSpark, a division of Ingram, must be distributing these books to the broader retail market. My assumption was that retailers, in particular Bookshop, would not accept self-published books coming out of Amazon’s KDP. (Amazon KDP authors can choose to enable Amazon’s Expanded Distribution at no cost, to reach retail markets outside of Amazon.)

It turns out my assumption was wrong. Bookshop does accept self-published books distributed by Amazon, and here things get a little convoluted. Amazon Expanded Distribution uses Ingram to distribute; Ingram is the biggest book distributor and there isn’t really any other service to use for distribution as far as the US/UK.

However, Bookshop’s policy is not to sell AI-generated books unless they are clearly labeled as such, so Fire and Fury was removed from sale after they were alerted to its presence. Bookshop’s founder Andy Hunter tweeted: “We will pull them from @Bookshop_Org when we find them, but it’s always going to be a challenge to support self-published authors while trying to NOT support AI fakes.”

And now we come to why self-publishing authors have reason to be seriously concerned about the rising tide of AI-generated books.

Amazon KDP is unlikely to ever prohibit AI-generated content. Even if it did create such a policy, there are no surefire detection methods for AI-generated material today.Amazon KDP authors can easily enable expanded distribution to the broader retail market at no cost to them. It’s basically a checkbox.Amazon uses Ingram to distribute, and Ingram reaches everyone who matters—bookstores, libraries, and all kinds of retailers. Ingram does have a policy, however, that they may not accept “books created using artificial intelligence or automated processes.”Based on what happened with Fire and Fury, Amazon’s expanded distribution can make a book available for sale at Barnes & Noble and Bookshop in a matter of days.If the rising tide of AI-generated material keeps producing such questionable books—along with embarrassing and unwanted publicity—one has to ask if Barnes & Noble and Bookshop might decide to stop accepting self-published books altogether from Ingram or otherwise limit their acceptance. Obviously not good news for self-published authors, or Ingram either.

What are some potential remedies?Ingram is an important waypoint here. They’ve put stronger quality control measures in place before. Perhaps they can be strengthened to prevent the worst material from reaching the market outside of Amazon.Amazon’s Expanded Distribution requires that authors use Amazon’s free ISBNs. Would it be possible for retailers to block any title with an Amazon ISBN? (ISBNs identify the publisher or where the material originated from.) While that may be unfair to honest people who prefer to use Amazon’s Expanded Distribution, such authors/publishers would still have the option of setting up their own IngramSpark account. IngramSpark has no upfront fees and also provides free ISBNs.Maybe IngramSpark or other retailers put a delay on making Amazon’s Expanded Distribution titles available for sale. Amazon already states it can take up to eight weeks for the book to go on sale. So why not make such titles wait?Free ISBNs unfortunately contribute to this problemISBNs are a basic requirement to sell a print book through retail channels today. In the US, it is expensive to purchase ISBNs—it’s nearly $300 for ten. Amazon KDP does not require authors to purchase ISBNs and will give you ISBNs for free all day if you need them. Over time, others like IngramSpark and Draft2Digital have also made ISBNs free to make it easier for self-publishing authors to distribute their work.

While it’s admirable to lower the barriers for authors who have limited funds, free ISBNs are supercharging the distribution of AI-generated materials to the wider retail market. An immediate way to stem this tide of garbage in the US market? Stop giving out free ISBNs. Make authors purchase their own.

There’s a huge advantage to making authors purchase their own ISBNs: it creates an identifiable publisher of record with Bowker (the ISBN-issuing agency in the United States). The publisher of record would be listed at retailers. Currently, fraudsters using Amazon KDP are able to hide behind Amazon-owned ISBNs; their books are simply listed as “independently published.” It would be marvelous to take away that fig leaf. Sure, fraudsters could create sham entities that mean nothing and are unfindable in the end, but at least you could connect the dots on all the titles they’re releasing—plus Bowker would see who’s doing the purchasing and possibly put their own guardrails in place. My hope is these entities would choose not to buy ISBNs at all and this activity would become limited to the backwaters of Amazon.

Professional self-publishing authors who distribute widely outside of Amazon are buying their own ISBNs already. Those who aren’t? I would consider it, because if nothing changes about the current situation, we may be entering a period where a book without an identifiable publisher (or author) is immediately considered suspect. And that’s another problem for self-publishing authors.

As of this writing, Barnes & Noble still has Fire and Fury listed, with a sales rank of #24. But it is “temporarily out of stock,” which makes sense if Amazon is the distributor and it took down the book. How long will the ghost of it linger?

August 18, 2023

Mining Your Memories: 3 Forms of Memory Every Memoirist Must Know

Photo by Nicolette Attree

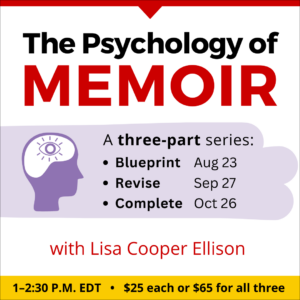

Photo by Nicolette AttreeToday’s post is by writer, speaker and coach Lisa Cooper Ellison. Join her for the three-part webinar series The Psychology of Memoir, beginning August 23.

Does Shaggy from Scooby Doo have an Adam’s apple? Answer quickly. Then survey three friends. Got a partner? Quiz them too.

While this might seem like a strange exercise, it has a direct impact on your memoir.

I recently asked my husband this question. His response: definitely. That’s what I said too! Apparently, millions of people share this memory. Except we’re all wrong. This collective misremembering is called the Mandela Effect. It’s why people swear there was once a cornucopia on the Fruit of the Loom logo or that Curious George had a tail.

This exercise reveals just how fickle, and at times inaccurate, our memories can be. Yet many memoirists begin with a goal of writing and owning their truth. A portion of these writers have been told what they observed, felt, or experienced wasn’t real. After a lifetime of gaslighting, they want to own their version of reality. If that’s you, let me be clear: if you’ve been hurt by others, your feelings are real. I’m certain you vividly remember both what happened and how you felt. Getting all that down is a start, but there’s more to do.

Memoir is a story not just of what you remember, but the sense you make from it. Understanding how your memories work, and what to do with the less reliable ones, will help you with the meaning-making process.

Memories begin as sensory input the brain flags as important.This data is first stored in working memory so we can use it to complete daily tasks like keeping track of the time while cooking. If this data proves useful beyond the task or situation, it gets bumped to short-term memory for overnight processing where it will either be turned into long-term memories or scrapped. From the brain’s perspective, useful equals important to survival. That means threats, your first kiss, best orgasm, or greatest high will get priority over who shot Abe Lincoln. Events associated with strong emotions and things we rehearse throughout the day also take precedence. Much of the rest ends up in your brain’s circular file. Even long-term memories are periodically pruned to make room for new information.

Your age, mood, physical health, and whether you have a trauma history will impact which events you encode as memories, which details are retained, and which moments you recall. For example, if you’re sad, you’re more likely to remember other negative events, whereas if you’re in a great mood, the past you recall is likely to be peachy.

There are three types of long-term memories memoirists will need to mine: semantic, episodic, and procedural.

Semantic memory encompasses your general knowledge, including concepts, facts not associated with your life, vocabulary, and important dates, to name a few. It’s where you filed your answer about Shaggy’s Adam’s apple.

Episodic memories include specific events and experiences that make up your life, like your first visit to the ocean or all the rainy afternoons when you watched Scooby Doo. A portion of these memories will be flashbulb moments. According to Very Well Mind, flashbulb memories are “vivid memories about emotionally significant events.” They’re more likely to form when there’s a widespread crisis or public event, and they differ from trauma memories or flashbacks because, while they’re upsetting in the short term, recalling them years later will not make you anxious. Common flashbulb memories include where you were on 9/11 or when JFK was assassinated, or what you were doing when you learned of the first COVID-19 lockdown.

Procedural memory involves the skills you’ve learned. It’s sometimes called your muscle memory because the things stored there are so ingrained, they’re automatic, like driving a car or speaking your native language.

Memoirists often begin with episodic memories, so knowing how to evoke them is essential. But you’ll need the other two as you write and revise, so don’t discount them. Because memories are associative, the more you work to remember, the more you’ll uncover. Here are a few tips to get you started:

Episodic memory: Engage your senses. Look at photographs, advertisements, magazine articles, and movies from the period you’re writing about. Eat foods associated with that era. Create a memoir soundtrack. If possible, visit locations where your memoir takes place, and don’t just look around, inhale the scent of the air. Run your hands along the walls and door frames. Listen to the hum of the furnace. Make a list of the memories these activities conjure. Semantic memory: List the general facts you remember from your memoir’s timeline, including popular games, toys, car models, clothing styles and slang; key world events; cultural zeitgeists and movements. Next, do a newspaper search and jot down headlines of interest. What memories do they trigger about the world? Do the same with any period documentaries. At this point, don’t worry about accuracy. Just see what you can remember.Procedural memory: While procedural memories might seem unimportant, it’s likely your actions mirror another character’s. Mindfulness can be a huge ally here, because it can help you turn the automatic into the conscious. To access your procedural memories, pay attention to how you walk, eat, drive, or sit. Doing these things slowly will help. Then record what you notice, and more importantly, where you may have learned it. For example, while driving, do you always put your hands on ten and two, or do you steer with one finger just like your father?In your first draft, all you need to do is record what you remember about your most important moments. In later drafts, you’ll do research to clear up any inaccuracies and deepen the context around what matters. But what do you do when you encounter something you SWEAR happened one way, but didn’t? For example, are you forced to denounce your strongly held memory of Shaggy’s Adam’s apple?

Sometimes what you misremember is the story and your job is to call attention to it. But here’s what you can do if that’s not the case.

In his interview with Melanie Brooks for Writing Hard Stories, Andre Dubus III says, “‘We can’t make shit up.” But when it comes to inconsequential items, like the weather or the description of a cartoon character, he says, “We are allowed a small degree of poetic license.” He goes on to describe a pivotal scene from his memoir where “he’s standing staring at his fourteen-year-old self in the mirror after watching his younger brother get beat up, and he vows to never walk away from a fight again.” As he recalls the memory, he says, “I still see every bit of that afternoon, and I see it in a gray, April light.” While he admits he could verify this memory by Googling the weather on that day, he chooses not to and, instead, quotes Tobias Wolff: “Memory has its own story to tell.” Your job is to “trust your memory.” And in your earliest drafts, see where those memories take you.

Note from Jane: if you enjoyed this post, joins us for the three-part webinar series The Psychology of Memoir, beginning August 23.

August 17, 2023

How to Land an Agent for a Graphic Novel

Today’s post is by graphic novelist K. Woodman-Maynard (@woodmanmaynard).

First off, you do not need an agent to get into comics and graphic novels. Comics have a long history of self-publishing and finding readers through conventions and web comics. I personally know many cartoonists who started out by self-publishing and later found an agent more organically through networking or being “discovered” through a convention or anthology.

However, for the sake of this article, I’m going to talk about traditional querying of agents, which is how I’ve found my agents—and I’ve had three (more on that later).

Why have an agent?Agents have two major roles: they help ensure that your work is seen by publishers, and they handle the business and legal side of the relationship with publishers. In exchange, they take a 15 percent commission of what you earn.

Publishers are overwhelmed by submissions, so there’s no guarantee that they’ll even look at your submission if you send it directly to them. (And some don’t accept unagented material at all.) The advantage to having an agent is that they have existing relationships with editors and publishers, which means they’re more likely to read agents’ submissions. They trust the agents to be sending good work their way. Agents can also help you craft your submissions materials so that they will be appealing to publishers.

On the business side of things, agents handle the contracts and negotiations and understand the market rate for work. I saw firsthand how useful having an agent could be when I got an unimpressive offer from a publisher for a graphic novel. If I’d been negotiating on my own, I’d have asked for 20% more, but my agent told me, “That’s a lowball offer. Let’s ask for double that.” So she asked for 200% of their initial offer and they agreed. And in that one move, she more than covered the cost of her commission.

Who should I query?You should only query agents who represent graphic novels, which will narrow down the field quite a bit. And you’ll want to find agents who represent graphic novels similar to the one that you are creating. For example, if you’re writing middle-grade fantasy graphic novels, you probably want to see some similar titles already represented by the agent you’re querying.

I used a spreadsheet to keep track of the agents I was thinking of querying. I included things like links to their websites, their submission guidelines, why I thought they’d be a good fit, the date I queried them, and if I ever heard back. Be prepared for querying to require a lot of waiting. Some agents respond within hours, others take months to respond, and others never respond.

If you know other cartoonists, ask them about their experience with their agents and if they’d recommend them. Talking to people is often the best way to get a sense of which agents are well respected.

How many agents should you query?I recommend querying in batches. I started by querying my top 3–5 agents, waited several weeks to hear back, then moved to the next couple agents on my list. By querying in batches, you give yourself time to edit your query if you get any helpful feedback, and also give your top choices time to respond.

What do you need to pitch?One of the biggest differences in pitching graphic novels compared to text-only books is that you do not need to have the book done in order to find an agent or sell it to a publisher. Instead you create a proposal that includes samples of the final art and an overview of the project.

All agents seem to ask for something different, but here’s a general overview of what you’ll likely need. When querying, be sure to follow the specific agent’s guidelines. Agents receive so many queries, don’t give them a reason to overlook your work because you didn’t follow their directions.

Query letter: See Jane’s article on querying. That’s how I learned to do it!Specs: I like to include projected page count, trim size, full color or black-and-white printing, genre, target age group, and comparable titles.Synopsis (usually 1–3 pages): See Jane’s excellent article on synopsis writing. I still use this when writing synopses for proposals.Sample art: There isn’t a set amount of art that all agents require, but you want to give them enough finalized art to get an idea of your storytelling style, coloring (if applicable), and character design. I tend to think you should submit sequential pages, working from the start of the book. My goal is to make an agent curious to read more. That said, I have heard of people submitting random pages from different parts of the book, but I don’t think that gives agents a good idea of your sequential storytelling capacity, which is very important with comics making. When I was querying my graphic novel adaptation of The Great Gatsby, I had the first chapter of final art done (22 pages), but most agents only wanted to see 10–15 pages. So in my query letter, I said I was attaching the first 15 pages, and could send an additional 7 upon request.Art file format: If submitting sequential pages, I’d recommend submitting them as a PDF to make sure all the pages are kept together, as opposed to individual JPGs. You don’t need super high resolution (and huge) files for submitting to agents, but you don’t want to send pixelated art either. One thing that threw me when I was querying is that some agents state in their querying guidelines that they don’t want any attachments on emails. In that case, you can link to a page on your website where the art is. If you’re concerned about privacy, you can make it password protected and give the agent the password in your query letter. Or you could link to a Google Drive or Dropbox folder.Script: This isn’t required, and some cartoonists don’t even work from scripts, but if you do, it’s a good thing to share with a potential agent if they request to see more content.There isn’t a standard script format, so do a little research and see what works for you and stick with the format throughout the script.What if I’m just the writer (not the artist)?

Writers can query on their own and generally the publisher will find an artist to pair them with for that project. Some agents will represent an artist-writer team, but most prefer to represent individuals.

What if I’m just the artist (not the writer)?It’s my understanding that it’s rare to get an agent as a comic artist not attached to a specific book. Before querying, you should see if the agent will even consider this. Anecdotally, it seems like comic artists (who aren’t also writers) get agents because they also do picture book illustration, or are working in partnership with a writer on a comic, and get introduced that way.

Listen to your gut!During my first time querying agents on a YA fantasy graphic novel, I initially sent out queries to my top agents. I got a few requests to read the full script, but my top choices ultimately passed on my story. So I moved on to agents further down the list. Eventually, I got an offer within a few hours of submitting from an agent at a large literary agency. I was ecstatic, but also wary after speaking with him.

Something didn’t sit right with me and I wasn’t sure he’d actually read my book based on a few comments he made. Even though he had a good track record in Publishers Marketplace, I waffled about whether to accept his offer. But I couldn’t find anything negative about him online, and I reached out to a few clients who said he sold their books and they were generally happy with him. Since I didn’t have any other offers, I decided to go with him, despite my reservations.

After a year, he hadn’t sold my first book and he had my second graphic novel out on submission. However, news started coming out about him as being a poor agent and he was asked to resign from the US professional literary agent organization. After talking to various people I knew in the industry and seeing examples of his actual pitches of my work, I decided to break ties with him.

I was demoralized—those two books represented over five years of work, but I was already working on another book that seemed more marketable—a graphic novel adaptation of The Great Gatsby. So I went back to my original list of agents and pitched Gatsby to one of my top choices of agents (who had rejected my earlier book). Within about a day, she offered to represent me.

I felt burned by my first agent and I was still a little wary, so I decided to meet her in person before signing. After meeting her, I felt confident in her and the agency, both of which had a stellar professional reputation. And a few months later, she sold Gatsby to Candlewick Press and helped negotiate a deal that I was happy with.

What if it doesn’t work out with the agent?You need to be on the same page as your agent and make sure that they’re aligned with your goals, which may change over time. Just like with any relationship, a person may work out for a time, but not be the right fit in the long term, which is what happened with my second agent.

After publishing Gatsby, I was working on a project for a few years that my agent ultimately didn’t think she could sell. I felt compelled to keep working on it and eventually we decided to amicably part ways since I still wanted to try to publish it.

After parting with my agent, I was back looking for an agent for the third time, and feeling demoralized again. However, I’d already published Gatsby, and now had a lot more connections in the graphic novel world.

Since I was co-creating a graphic novel with a writer-friend, my friend reached out to her agent to see if she’d be willing to represent both of us for that specific project. Her agent requested I send along my other work for her to look at. She looked it over and she offered me representation for all of my work. I liked her a lot, she represented several people I knew, had an excellent reputation, and she seemed to understand my work and what I was trying to accomplish, so I signed with her.

And a wonderful postscript with my second agent is that a graphic novel adaptation project came across her desk that she thought I’d be great for, and passed it along to me, even though I was no longer her client. That graphic novel will be coming out in Fall 2025.

Additional resourcesThis page by Nikki Smith has a list of agents who represent graphic novels.Agent Maria Vicente has an excellent article on querying graphic novel agents.August 16, 2023

Book Family Tree: A New Way to Think About Your Book

Photo by veeterzy

Photo by veeterzyToday’s post is by author Ilana DeBare.

Choosing good comparable titles can be a brain-busting challenge for many writers. Comps let agents and publishers know where your book fits in the marketplace, and they’re helpful in crafting a publicity strategy. But it can be hard to find books that feel like an exact match, especially if you’re writing fiction and your novel doesn’t fit neatly into genre categories.

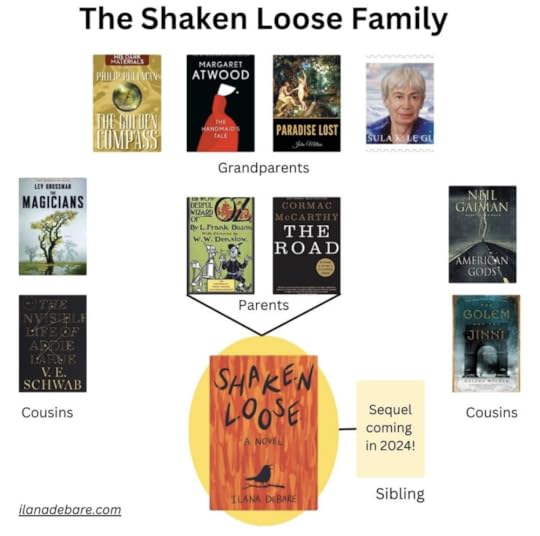

That was the case with Shaken Loose, my debut fantasy novel set in an unjust and unraveling Hell. During the long march to its recent publication, I came up with the idea of a Book Family Tree—an exercise that helped me better understand my own book and where it fit in the world.

It was not only enlightening but fun! So I made a free template that allows other writers to easily create family trees for their own books.

But first, some background.

While querying agents and publishers, I spent countless hours brainstorming potential comps while never feeling that any single one was a perfect match. Shaken Loose challenges organized religion like The Golden Compass, but it doesn’t have that book’s epic sweep; it features nuanced characters with existential dilemmas like The Golem and The Jinni but it isn’t historical fantasy. The landscape and backstory of its Hell are modeled on Paradise Lost, but clearly a 350-year-old poem isn’t a useful comp.

My book had an identity crisis. Or maybe the crisis was mine: I didn’t know where it belonged.

I’m a genealogy hobbyist as well as a writer, so I started playing around with the idea of creating a family tree for my book. If Shaken Loose had parents, who would they be? How about its grandparents? Its cousins?

This turned out to be a great deal of fun. It helped me think more broadly about the influences on my book and identify works that might not be an exact match but were still related.

With a family tree, I could list Paradise Lost as a grandparent—part of my book’s DNA, a foundational influence although vastly different in structure, perspective, and style. As parents, I chose an extremely odd couple—The Wizard of Oz and The Road—that expressed the book’s upbeat “quest for home” plot but also its vein of gritty darkness.

The “cousin” part of the tree was where I placed books that were actual comp candidates—recent upmarket fantasy like The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue. This was a reassuring way for me to think about comps: Cousins share a lot of traits, but no one expects them to be as similar as siblings. Certainly no one expects them to be identical twins.

I came away from this exercise with a better sense of where my book fit into the literary world. It helped me clarify the difference between influences and comps. And when publication day came, I felt like I had good answers if anyone asked me what books and writers had shaped my work.

To be clear: creating a book family tree isn’t a substitute for choosing one or two comps. Don’t try to send a family tree diagram to agents instead of a standard query letter! Nor will a family tree circumvent the task of identifying recent similar books in your genre. But if you’re feeling stymied, it may open up new ways of thinking about your work. And once you’re published, you can use it as a graphic in your marketing.

At the very least, you’ll have a colorful diagram to hang over your desk and remind you that—even if the world hasn’t recognized it yet—you’re a writer in a big, sprawling tradition of other writers.

The Book Family Tree template is available on Canva, a graphic design app with a robust and useful free version. Access it through my website. You’ll be prompted to create a free Canva account if you don’t have one already. Customize the template by uploading cover images of your chosen books, then download your finished diagram. (You can add or subtract “relatives” as you see fit.)

If you share your tree on social media, please tag me: I’d love to meet your family.

August 15, 2023

How to Deal With Rejection: Celebrate!

Today’s post is excerpted from Stop Waiting for Perfect by L’Oreal Thompson Payton (@ltinthecity), published by BenBella Books.

Throughout the years, I’ve learned that the first step toward many of the Big Hairy Audacious Goals we have “only” requires five seconds of courage. We’ve got only in quotation marks here because, well, as you know, life is never that simple, my friends.

But think about it. Sometimes you’re just one submit button away from a life-changing fellowship. Or one phone call away from a contact that could land you your next gig. The possibilities are endless, but first you have to, ya know, do The Thing. Of course, if you put yourself out there, rejection is inevitable. It’s also subjective, but that doesn’t make it hurt any less.

Case in point, shortly after giving a friend a pep talk about rejection being part of the writing process after an essay she’d pitched was deemed “not a great fit,” I received a rejection myself, this time for a literary retreat for writers of color I so desperately wanted to attend. That one stung.

It was time for me to take my own advice and remind myself that not only is rejection part of the process, it can be a blessing. Or as my Twitter peeps (tweeps?) often share, “Rejection is protection.”

There was definitely a time when I didn’t believe this. The heart wants what it wants, y’all. So it never helped when my mom would try to make me feel better by saying, “What’s meant for you won’t miss you” until I got old enough to understand she was right, as much as it pains me to admit.

When I look back at the jobs and opportunities I’ve lost, it was always God setting me up for something bigger and better. In these instances, my setbacks really were a setup for my comeback. But that doesn’t mean I go running toward rejection with open arms. I’m not that evolved.

One way I’ve learned to reframe rejection is by celebrating it. Yes, you read that right. I know it may seem counterintuitive (we’re conditioned to celebrate wins and shroud our losses in secrecy and shame), but I believe celebrating your rejection is part of how you take your power back.

So without further ado, a quick recap of some of my greatest rejections of all time (in no particular order):

Rejected from Georgetown University for undergradRejected from my dream internship—twiceRejected from University of Maryland for grad schoolRejected from Jet—twiceRejected by four literary agents while querying this bookRejected by an independent feminist media company for an executive director positionRejected from a literary retreat for writers of colorRejected for a staff writer position at an outlet I was already freelancing for (that one still doesn’t quite make sense to me)And rejected by another publisher that passed on this book (their loss).That’s not even counting all the pitches and book queries I’ve sent into the ether over the years that received no response at all. It feels like … a lot. But then I think back to a post I read about a writer who aims for at least 100 rejections a year because in order to reach that number, you have to put yourself out there, and that’s worth celebrating in its own right.

Another reason I recommend celebrating rejections is because it means you tried. You did a brave thing, a new thing. You took a risk, and it didn’t work out this time. But so many people talk themselves out of even trying. It’s easy to play it safe, play it small, and not put yourself out there. But the real magic—the real good dope stuff—happens outside your comfort zone.

To help you bounce back from your next rejection (because if you keep trying and keep growing, rejection is inevitable, friends), here’s my four-step recovery plan.

Step 1: Throw yourself a pity partyListen, I’m always one for a good pity party. The more pitiful, the better. I’m talking about eating a pint of Jeni’s ice cream straight from the container while watching The Real Housewives of Potomac reruns with Chinese food on the way via DoorDash and a bottle of rosé nearby. And if you really want to up the pity, consider throwing yourself an actual party complete with party hats and those cute little drink straws. This type of “Go Big and Go Home” mentality works especially well for major rejections, such as failing the LSAT, getting rejected from a fellowship, or breaking up with your partner (even if you’re the one who initiated it).

Give yourself permission to sulk, but set a time limit on it—whether it be two hours, one day, or one week. We must take time to not only acknowledge, but honor our feelings. The crucial part is not letting your pity party morph into a self-loathing spiral. If you don’t trust yourself to get out of said spiral in a timely fashion, enroll the help of a good friend to check in and make sure you’re OK. Your feelings are important, but they do not own you. Reclaim your power.

Step 2: Ask for feedbackI know, I know, you don’t necessarily want to thank the person who rejected you, but it’s important to:

Show gratitude for the time and energy they spent interviewing you/reviewing your application/getting to know you;Not burn any bridges (you never know, their top candidate may not work out); andDetermine what you need to work on or what you want to do differently next time.Not everyone is humble (and mature) enough to ask for feedback, so this will automatically make you stand out to the recruiter, hiring manager, editor, etc. Understand, however, that everyone won’t be able to provide thorough feedback and not all feedback is good feedback. You’ll definitely want to take any and all advice with a grain of salt. Take what you need, or what is applicable to your situation, and leave what you don’t.

Step 3: Apply the feedbackNow it’s time to conduct your own assessment. Evaluate what went well and identify areas of opportunity. Not sure where there’s room to grow? Ask a trusted friend or colleague to tell you the truth, and not one who’s going to constantly tell you you’re the greatest thing since sliced bread (OMG, it’s happened! I’ve officially completed the transformation into my mom).

Bookshop • Amazon

Bookshop • AmazonThis is where an accountability buddy (or accountabilibuddy, as I like to call them) comes in handy because they not only encourage you, they hold you accountable (duh) for your actions, both good and bad. A good accountabilibuddy will hold your hand; a great accountabilibuddy will call you out on your shit (with love). Find yourself a friend who can do both. Then apply your learning to the next application, interview, or whatever you’ve decided to try.

Step 4: Dust yourself off and try againYou tried, you failed, and now it’s time to put yourself back out there. This is the part where so many people get stuck. Will you allow self-doubt to prevail, or will you shake it off, trust your dopeness, and confidently walk back in the ring like the boss that you are? The choice is yours.

August 9, 2023

An Unconventional Facebook Ads Strategy for Authors

Today’s post is by book advertising consultant Matt Holmes (@MatthewJHolmes1).

From April 2020 through to November 2022, I ran Facebook Ads in a way that ticked all the boxes when it came to best practices. But in December 2022, our Facebook Ads took a nose dive—sales, page reads, bestseller rank, and overall royalties all dropped. We went from earning $17,396 in November 2022, to less than $10,000 in January 2023. That’s a big drop in 2 months.

Something had to change. I tested everything—new audiences, new ad creative, higher daily budgets, different ad placements—but nothing worked. Until that is, at the end of January 2023, I had one last push testing something I’d never tested before. I 100% believed this wasn’t going to work and was incredibly skeptical. But what did I have to lose?

Nothing else has worked, but boy did this new strategy work. It tripled our Facebook Ads conversion rates in the UK, and doubled our Facebook Ads conversion rates in the USA, in comparison to the results I’d been having from Facebook Ads since April 2020.

And this new Facebook Ads strategy I discovered is what I’m going to share with you today, that is responsible for the $17,500 month we had in July 2023, with my wife’s 4 fantasy novels (4 books in the main series, plus 1 companion novel).

Here’s what you’ll learn in this article:

Why the traditional method of running Facebook Ads is outdated (and is in fact hurting your results, and your bottom line)My exact Facebook Ads strategy (that shouldn’t work, but does)The biggest lever you can (and should) pull when advertising books with Facebook AdsHow I test Facebook Ads that harness the power of Facebook’s machine learningWhy less is more when it comes to optimizing and scaling your Facebook Ads for bigger and better resultsThe problems with following Facebook Ads best practicesIf you are a member of one or two Facebook Groups discussing Facebook Ads for authors, you have likely come across best practice strategies. Invariably, these discussions revolve around targeting, specifically using something known as Detailed Targeting with your Facebook Ads. On the surface, Detailed Targeting sounds incredibly exciting, but in practice, it’s destroying your results.

Detailed Targeting allows you, as the advertiser, to pinpoint who you want to show your Facebook Ads to, for example:

Women, in the USA, aged 25–60, who have an interest in Stephen King, Amazon Kindle, and the Kindle Store

What could possibly go wrong? After all, these are your ideal readers who are going to love your book!

Well, there are a few things that could and most likely, will, go wrong with Detailed Targeting:

The performance of your Ads is going to get worse and worse over timeYou’re restricting the Facebook Ads algorithm from performing at its bestThe Detailed Targeting audience you choose could be removed at any time (without warning)You will pay more to use Detailed Targeting audiencesPerformance will be volatileIt will be difficult to scale Ads (i.e. spend more) that use Detailed TargetingMany people who are in a Detailed Targeting audience don’t actually belong thereTo top it off, your Ads aren’t even reaching the people who would most likely resonate with your book(s). This is because you are throttling the algorithm too much to be able to do the job it was designed and engineered to do in the first place.

In essence, when you use Detailed Targeting, you are investing in a depreciating asset, that will only become worse and worse over time. How do I know this? Because I used to use Detailed Targeting myself, and I’ve seen all of the scenarios above play out with my own Facebook Ads.

So, if Detailed Targeting is so bad, what do I use? I use a strategy I call Unrestricted Targeting, which we’ll dive into right now.

Here’s my Exact Facebook Ads strategyIf you want to see your Facebook Ads performance skyrocket, you need to use this incredibly powerful tool as it was designed to be used.

You see, what many advertisers don’t realize is that the Facebook Ads you run (i.e. the ads people see on their Facebook feed) create their own audiences, based on the content of those ads. As soon as you publish an ad, the Facebook Ads algorithm is going to analyze that ad and look at elements such as:

The words you use in your adThe style of image in your adThe content of your image (e.g. gender of person, emotions, age, landscape, object, etc.)It’s even going to look at the landing page you’re sending people to from your adAnd many more data points besidesBased on the data the algorithm collects from its analysis, it’s going to start building an audience of people it believes will resonate with this specific ad, and start showing it to those people. As it learns which of these people do and don’t like the ad, it will find more people who have similar characteristics to people that did like the ad, and stop showing it to people who have similar characteristics to those who didn’t like the ad.

And over time, the performance of the ads just becomes better and better, as the algorithm starts learning who does and doesn’t like the ad. You can see from the diagram below just how much restriction you are placing on the algorithm when you follow best practice and use Detailed Targeting with your Facebook Ads.

With this in mind, as I alluded to a little earlier, I want to give the Facebook Ads algorithm free rein to find the ideal audience for my ads, and I achieve this through Unrestricted Targeting.

With Unrestricted Targeting, the only targeting I’m using is:

LocationGenderAgeI am using zero Detailed Targeting—yes, I’m going against all the best practice advice out there for authors, and have been doing so since the beginning of 2023.

You can see my targeting setup illustrated in the screenshot below of one of my Facebook Ads:

As you can see, I’m targeting:

Women, aged 35–65+, who live in the United States

The red arrow in the image above is demonstrating that I’m using zero Detailed Targeting. I use this targeting approach for every single Facebook Ad I run. The results, compared to Detailed Targeting:

Doubled our Facebook Ads conversion rates in the USATripled our Facebook Ads conversion rates in the UKCheaper costsMore scalableMore stable (less volatility)More profitable Facebook Ads (because I’m not spending money testing audiences)The Facebook Ads algorithm loves account simplification because it can work freely, without being restricted everywhere it turns—which is the common scenario it faces with most advertisers. So, I have simplified my Facebook Ads Account Structure in a way that takes full advantage of Facebook’s incredible machine-learning and AI capabilities.

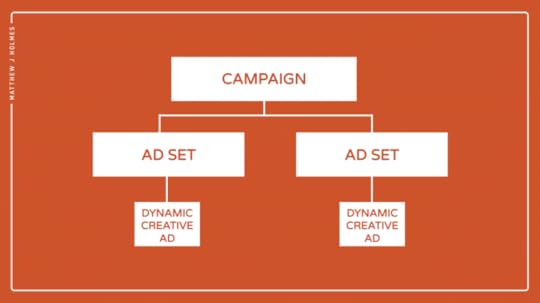

Here’s how it works:I use ONE Campaign per book, per country.All my testing and scaling is performed inside this one Campaign.Within this one Campaign, I have up to 3 active Ad Sets at any one time:1 x Ad Set that contains my winning (proven) Ads1–2 Ad Sets that are testing Ads for me (more on this coming up)Ad Sets are where you define the targeting for your Facebook Ads, as well as where you want your Ads to show across Facebook’s (Meta’s—as this is now the parent company of Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, etc.) ecosystem.

The diagram below shows a visual representation of my account structure:

N.B. “DCT”, as shown in the diagram above will become clear very shortly!

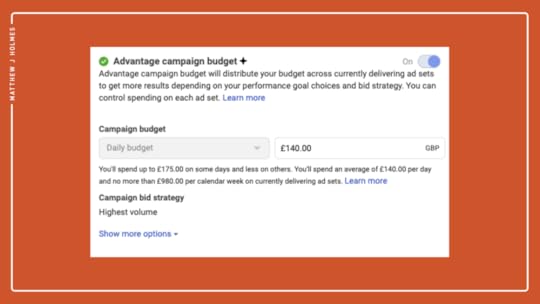

Finally, I set my budget at the Campaign level, not the Ad Set level (another best practice I don’t follow). I do this using something called Advantage Campaign Budget.

This setting will tell Facebook to spend the daily budget you determine (I’d recommend $20 per day at a minimum), on the Ad Sets that contain the ads driving the most engagement—and usually, these ads are the ones delivering most of the sales and/or page reads.

The result of this incredibly simple account structure means that you’ll spend far less time in your Facebook Ads account, allow the algorithm to work to its full potential, and produce more profitable results because you’re showing your ads to people who actually want to see them, and not wasting money testing Detailed Targeting audiences. And on top of all of that, this strategy is going to provide you with more time for writing!

If you’re feeling skeptical about putting so much trust and faith into the Facebook Ads algorithm, I completely understand, as I felt exactly the same when I first started dabbling with this strategy. It feels like it shouldn’t work, but it does. To the tune of $300+ per day in profitable, Facebook Ads spend for myself, with a 2x return on investment.

But it’s not just me this strategy works for, if that’s what you’re thinking. I have shared this exact strategy with countless authors inside my FREE Facebook Ads For Authors Masterclass video series, and I hear success stories multiple times per week.

With the strategy covered, let’s now move onto what is often considered an afterthought by many authors running Facebook Ads (myself included in the beginning), but is in fact the single biggest driving factor of your success.

The biggest Facebook Ads lever you can pullThe easiest thing to do with your Facebook Ads is to change the targeting—i.e. change who you are showing your ads to, using Detailed Targeting. As we’ve already discussed though, using Detailed Targeting is the same as investing in a financial stock or share that will forever tumble downwards.

A more difficult thing to do with your Facebook Ads is work on your skills as an advertiser, creating better and better ad creative—i.e. the ads people are seeing on their Facebook Feed. Focus on this, and your results will explode. Ignore it, and watch your Facebook Ads crash and burn.

Yes, creating better ads is hard, but with the advancement of AI tools such as Google Bard, ChatGPT and MidJourney, creating assets for your ads has in fact never been more simple. It’s not easy, but it is simple.

If your Facebook Ads aren’t working, best practice will tell you to show your ads to a different Detailed Targeting audience. I’m here to tell you that this is the wrong approach. Sure, the ads might work for a short amount of time, but after a few weeks, or months if you’re lucky, you’ll be back in the exact same position.

By committing to working on your craft as an advertiser, and creating better and better ads based on your research and analyzing the data of your own ads, in 3–6 months time you will be so far ahead of where you are today, you will surprise even yourself.

Personally, I have created and launched over 1,500 Facebook Ads for Book 1 of my wife’s fantasy fiction series. That’s a lot of ads. But if you compare the results of my first ads to my latest ads, the difference in quality, professionalism, performance and results is night and day.

If you want to improve your skills at anything in life, you need to commit to doing that thing regularly, analyzing the results, and iterating based on those results. This is partly why I test new Facebook Ads every single week.

The other reason I test Facebook Ads weekly is because I want to provide the Facebook Ads algorithm with plenty of assets and opportunities to find new readers day in, day out, and discover ads that perform well which I can scale up to reach a bigger and bigger audience.

Let’s now jump into my Facebook Ads testing process and I’ll explain how I test Facebook Ads so regularly and the strategy I use to do so.

How I test Facebook Ads (without doing any of the heavy lifting)As I’ve already mentioned (on several occasions), the Facebook Ads algorithm is incredibly powerful and knows more about its user base than we can comprehend. Not only can we harness the power of the algorithm to find our ideal audience through unrestricted targeting, but we can also use it to test our Facebook Ads creative for us. By this, I mean the ads that people are seeing on their Facebook feed, Instagram feed, etc. The method of testing Facebook Ads creative I’m soon going to share with you is another cornerstone of my Facebook Ads strategy, that allows you, as the advertiser, to do much less of the heavy-lifting that is usually required.

The traditional way of testing Facebook Ads is to test ads individually, like this:

As you can see from the diagram above, there are multiple ads within a single Ad Set. This is how I used to test Facebook Ads too. The difficulty and challenge with this approach is that you are essentially forcing certain ads onto people who may not like what you’re showing them, which drives up costs and reduces performance.

Fortunately, there is a solution: it’s called Dynamic Creative. And here’s how the account structure looks when using Dynamic Creative:

As the diagram above shows, with Dynamic Creative, you only have ONE ad within an Ad Set, keeping things much more streamlined and simple.

Here’s the beauty of this strategy though. Within this Dynamic Creative Ad, there are multiple assets:

Multiple imagesMultiple headlinesMultiple primary textsMultiple descriptionsMultiple call-to-action buttonsWhat Facebook will do with Dynamic Creative, is test combinations of all the assets within the ad, and, after a few days, you will know the winning:

ImageHeadlinePrimary textDescriptionCall-to-action buttonThis results in far less guesswork from you, trying to figure out which are the best pieces of a Facebook Ad! You’re letting Facebook do all the testing on your behalf. Once you know what the winning assets are, after Facebook has tested them for you, you can then take those winners and create a “standard” ad (i.e. a Non-Dynamic Creative Ad), and scale it up, with the confidence behind you that every part of this Ad is proven to perform.

I call these Dynamic Creative Ads, DCTs, standing for Dynamic Creative Tests, and, as we covered earlier on in this article, they can be seen in my very simple, but very effective account structure.

So, if you’re not yet using Dynamic Creative, I would urge you to start. It has been an absolute game-changer for not only my own Facebook Ads but also the authors who I have shared this strategy with.

Let’s now move onto the final piece of the Facebook Ads puzzle: optimization and scaling.

Optimizing and scaling Facebook Ads by doing less, not moreOptimization and scaling may sound a little overwhelming, but they are in fact very simple, and we’ll cover what both of these are here. Optimization is simply doing less of what is working and more of what is working. That’s all it comes down to. You’re just making your Facebook Ads more efficient by allowing your budget to be spent on the ads that are working. Once you know how a Facebook Ad is performing (i.e. how many sales it’s generating), if it’s not up to scratch, you simply turn that ad off. This will allow your budget to be spent on ads that are working and converting at an acceptable conversion rate, rather than being “wasted” on ads that aren’t generating many or any sales for you.

If you’re using Facebook Ads to advertise your books that are listed on Amazon, you should 100% be using a free tool provided by Amazon, called Amazon Attribution, which allows you to see how many sales and page reads an individual Facebook Ad is generating for you. This is critical information to understand because, without it, you wouldn’t know which Ads were converting and which weren’t, making optimization very difficult.

I’ve recorded a free video on how to set up and use Amazon Attribution, which includes a full video walkthrough. Click here to watch the Amazon Attribution Setup Video.

I used to “optimize” my Facebook Ads on a daily basis. This was a big mistake, as I never allowed the algorithm to work its magic. I now block out 60–90 minutes per week (on a Monday afternoon) to optimize my Facebook Ads. That’s all it has to take. Over-optimizing your Facebook Ads is a thing, and it will destroy your results. Less is more.

When you’ve optimized your Facebook Ads, you can then think about scaling. Scaling Facebook Ads is also very simple and takes mere seconds.

With the strategy I have shown you in this article, as we are setting the budget at the Campaign level, using Advantage Campaign Budget, the only thing you need to do to scale your ads is increase the budget—which takes all of about 6 seconds! Providing you know your Facebook Ads are converting well, scaling will allow your ads to reach more people. And because you’ve optimized your Ads already, you know you’re putting more money behind Ads that have been proven to convert.

What I will say about scaling is that you shouldn’t go too hard, too soon. Be respectful of your budget and don’t go in too heavy-handed, as this will only halt the momentum and traction you’ve built up with your Facebook Ads.

Instead, what I recommend is that you increase your budget by 10%–20% per week, if you’re profitable. If you’re not profitable, either leave the budget as it is for another week, and let the optimizations you’ve done take effect. Or, drop the budget by 10%–20% and allow that to run for a week.

If you increased your budget from $20 to $100 per day in one hit, Facebook’s algorithm wouldn’t know what to do with such a huge budget increase, and it would likely find poor-quality people to show your ads to, just so it can spend your entire budget each day. By gradually scaling your budget up on a weekly basis, you’re allowing the algorithm the opportunity to learn who your ideal readers are and find more people like them to show your ads to.

Parting thoughtsYou’re now equipped with the knowledge and understanding to start running Facebook Ads for your books in as little as 60–90 minutes per week, using a proven blueprint and strategy, leaving you more time for writing.

Before we wrap up here though, I want to share one big lesson with you that I’ve learned after spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on Facebook Ads.

Always look at the big pictureLooking at your Facebook Ads in isolation is a mistake I see many authors making. This is especially true when you are sending traffic from your Facebook Ads to your book(s) on Amazon.

Amazon has their own algorithm (that is perhaps even more difficult to fathom than Facebook’s algorithm!), and if you can show this algorithm that your books are selling well, Amazon will be more inclined to give your book more visibility. This enhanced visibility allows you to generate what are commonly known as organic sales. In short, organic sales are sales that are “free”, because you haven’t paid for them directly through ads. You will likely have seen your Best Sellers Rank on your book product pages on Amazon.

The lower the number of your Best Sellers Rank, the more visibility (and more marketing) Amazon will give you. Amazon may even start emailing their customers about your books.

To put this into perspective, with my wife’s books, only around 20% of our total sales come from our Facebook Ads. The remaining 80% are organic sales. But without the Facebook Ads driving those sales, our Best Sellers Rank wouldn’t be where it is and we wouldn’t be driving anywhere near that number of organic sales.

The other thing to keep in mind regarding the big picture is that you may only be advertising one book with your Facebook Ads, but if you have multiple books published, a good percentage of readers will go on to read those. And sales of these other books need to be accounted for. It’s not all about the book you’re advertising with Facebook Ads. It’s about all the other books that readers who bought Book 1 will buy over their lifetime.

On a final note…

Facebook Ads are not a magic bullet.They are simply a cog in a machine. A very important cog, but a cog nonetheless. Facebook Ads are an amplification tool that you use to position your books in front of your ideal readers and drive traffic to those books. It’s your book itself and the book product page that has to sell your book.

So don’t neglect honing your craft as an author, because no amount of advertising is going to sell a poor-quality book. Your book sells your book.

Thank you so much for taking the time to read this article; I truly hope you found it of value and that you can start transforming both your Facebook Ads results and your career as an author.

August 8, 2023

First Page Critique: How to Better Establish the Tone in Your Opening

Photo by Sonia Dauer on Unsplash

Photo by Sonia Dauer on UnsplashAsk the Editor is a column for your questions about the editing process and editors themselves. It also features first-page critiques. Want to be considered? Submit your question or submit your pages.

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Book Pipeline. Deadline August 20th for the 2023 Book Pipeline Unpublished contest. Awarding $20,000 to authors across 8 categories of fiction and nonfiction. Multiple writers have signed with top lit agents and been published. Use code Jane10 for $10 off entry.

A summary of the work being critiqued

A summary of the work being critiquedTitle: The Walking Ladies

Genre: mainstream/upmarket fiction

Four women set off on their weekly suburban walk expecting no more than a little cardio and the usual banter about kids and husbands. Instead, they discover a severed arm. The newcomer, Corinne Wilder, is a former war-correspondent with a drinking problem who decides to report on the case to escape her personal problems. Recent empty nester Jorie Eckholm becomes Corinne’s reluctant sidekick, flirting with repressed childhood memories of her best friend, who died after losing her arm in a shark attack. Only plunging into their past traumas can save the women from turning into people they never intended to become—and maybe even from death at the hands of a depraved killer.

THE WALKING LADIES is a complex relationship drama embedded in a murder mystery… with a side of body parts. The book has comedic undertones—think: Janelle Brown’s unlikely character pairings meet Shirley Jackson’s creepy gothic—and will appeal to readers who like character-driven fiction with a serving of suspense.

First page of The Walking LadiesThe sun surfaces behind the eucalyptus trees, spilling rose-colored light onto the street. Jorie can’t will herself to walk faster. She’ll be late, as usual, but she didn’t sleep well again and her feet refuse to hurry.

Turning right onto Sea Breeze and left onto St. John, she spots her friends at the edge of the empty school parking lot. Pegeen’s hands are shoved in the pockets of her warm-up jacket. Melanie is untangling Winkie’s leash from a wooden post. A third figure stands a few yards away, a tall, sculpted-looking woman with a ponytail, bouncing on the balls of her feet like a boxer. The stranger wears three-quarter-length tights that show off her calves and look good on women of Jorie’s age only if they exercise obsessively or are born lucky. Or both.

The Shih Tzu yips as Jorie approaches, anticipating their regular Saturday walk.

“Sorry!” Jorie waves and the women turn. “Were you waiting long?” Jorie has always been the unpunctual one, rushing to beat the bell on those long-past middle-school drop-off days with Steph scurrying alongside trying to eat a waffle folded inside a paper napkin.

“It’s fine.” Pegeen answers automatically. “We were talking about how energetic we’re feeling. I mean, whether we’re feeling energetic.” She backbends and digs her thumbs into the fleshy fold above her waistband, tilting her neck so her frosted blond hair brushes her shoulder. “This is Corinne, by the way. My new neighbor.”

“Pleasure.” The ponytailed woman extends her hand as if they’re at a business breakfast.

Corinne has a tall voice to go with her tall, sculpted body. Her grip is cool and her hand is almost as large as Victor’s. She doesn’t squeeze hard, but Jorie feels she won’t be able to extricate herself until Corinne decides to let go. The handshake’s firmness and formality surprise her. She can’t remember ever shaking hands with Pegeen or Melanie, not even when they first met, over greasy muffins and bitter coffee at the sixth-grade volunteer meeting on the first day of school.

“Nice to meet you.” Jorie says the expected words, although the stranger’s presence unsettles her.

Their group, which they’ve come to refer to as the Walking Ladies, has been just the three of them since they began these weekend walks to fill the void left when their kids started high school. This unexpected presence sends the ground shifting a little, as if an earthquake might be starting. She lets the newcomer pump her arm. Corinne is some years younger than she first thought, with hair that lies sleekly against her skull in a manner Jorie’s red-blond curls never do.

Continue reading the first pages.

Dear Audrey,Thank you for submitting your work for critique. Your opening pages read very smoothly, and your imagery—from the greasy muffins at the volunteer meeting to Corinne’s hair “swishing like a horse tail”—is so much fun. Jorie’s character comes across as smart and perceptive, namely when she realizes why Pegeen walks ahead with Corinne and away from her and Melanie: “Perhaps, having invited her without telling them in advance, Pegeen feels a responsibility to keep Corinne entertained.” The fact that Jorie is an empty nester is another plus: As The Guardian reports, women in this age group and older are “a hugely important demographic and increasingly, want to see themselves represented in books.”

What concerns me, however, is that it doesn’t seem dark enough to be considered a murder mystery, at least not so far. Granted, the group of friends will discover a severed arm, as explained by the summary, but there’s little in the tone or the wording of the novel—besides the brief mentions of Jorie’s anxiety and Corinne’s skull—that indicates the story is about the search for a depraved killer. To lay the groundwork for this plot point, perhaps …

Jorie can have read about a missing person in the paper that morning, assuming the arm belongs to this person? Or maybe, rather than notice Pegeen’s frosted blond hair, Jorie can notice how pale she suddenly looks? Should the rose-colored light of the novel’s first line, though lovely, be replaced with an eerie glow?Could the severed arm be described in an ominous way, especially considering that opening a mystery/suspense novel with a severed body part is a common trope? Novels published this year alone that begin as such include Reef Road by Deborah Goodrich Royce, in which a severed hand washes ashore; City Under One Roof by Iris Yamashita, in which both a severed hand and a foot wash ashore; and Bad Cree by Jessica Johns, which “opens with a startling image: a severed crow’s head in someone’s hand.”

It’s unlikely that the arm found by this group of friends—or more specifically, by Melanie’s dog Winkie—belongs to Jorie’s childhood best friend, who, per the summary, died after losing her arm in a shark attack, but perhaps the two victims can have something in common, such as the same tattoo or a watch, if this isn’t already the case? Creating a link between Jorie’s childhood friend and the murder victim should help make the novel’s premise more haunting and memorable.

Of course, this work is intended to be as humorous as it is dark, but somehow the comedic undertones referenced in the summary aren’t quite coming through. Granted, Melanie is described as a “frustrated stand-up comic,” but right now, though she’s said to “delight in putting a spin on mundane conversations,” she isn’t actually shown to do this. Instead, Jorie only imagines Melanie asking her how “the peach tree [is] shakin,’” for example. To make Melanie’s character funnier, perhaps she can mock Corinne’s “tall, sculpted body” and the “tights that show off her calves” to comfort Jorie, who seems conscientious about her appearance? Alternatively, maybe Melanie, rather than Jorie, should make the comment about how Corinne is “bouncing like a restrained racehorse”? This way, instead of repeating the image of the horse, you can position Melanie’s observation so that it complements Jorie’s, and the two friends can then share a laugh about how they think alike. Alternatively, perhaps Melanie can smell alcohol on Corinne’s breath or clothing (since the summary indicates that Corinne has a drinking problem) and make a joke about early morning drinking?

I’d introduce a conflict for Jorie—who appears to be the principal protagonist and sole narrator of the novel—that is separate from the mystery surrounding the murder. Currently, Jorie mentions several times that she hasn’t been sleeping well, but she doesn’t say why. If her insomnia has to do with Victor or Steph, she might touch on the tension she is experiencing with her husband or daughter. If Jorie is having trouble sleeping because of her career, she might reflect on how the real estate market is in decline. Perhaps this is why, as the summary reveals, she decides to become Corinne’s “reluctant sidekick” as Corinne reports on the murder? It’s possible that the reason Jorie can’t sleep has nothing to do with family or career. Instead, maybe she is haunted by sudden and unexpected nightmares about her childhood friend? If this is her situation, it should fit nicely with the main plot about the discovery of the severed arm. Just be sure to mention Jorie’s childhood friend before or at the same time as the murder victim.

One more suggestion is that you provide additional context about where the story takes place. It’s clear that the main characters live in a hilly neighborhood close to a school, and in some ways, this information is sufficient. But what’s puzzling here is that at least three streets are named, and Jorie is curious about where Corinne moved from. This brings up the question about where Corinne moved to—or where the characters currently live. Given that Jorie walks down a street called “Sea Breeze,” that a shark attack claimed the life of her childhood friend, and that she references earthquakes, it sounds like the story takes place near the coast, specifically the California coast. If so, can Jorie feel the ocean breeze as she walks? Think about how she never cared for the ocean because of what happened to her friend? Then, as the story progresses, she or another character can provide more details about the city or region where it takes place.

I hope this feedback is helpful. Rest assured that The Walking Ladies reads beautifully as is. You might just check that your vision for it matches the content and style. Might I suggest that you have a look at the work of bestselling author Carolyn Brown, in addition to that of Janelle Brown and Shirley Jackson? Carolyn Brown’s novels include The Empty Nesters and The Ladies’ Room, which might be relevant. Best wishes to you!

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Book Pipeline. Deadline August 20th for the 2023 Book Pipeline Unpublished contest. Awarding $20,000 to authors across 8 categories of fiction and nonfiction. Multiple writers have signed with top lit agents and been published. Use code Jane10 for $10 off entry.

August 7, 2023

I Would Rather See My Books Get Pirated Than This (Or: Why Goodreads and Amazon Are Becoming Dumpster Fires)

Update: Hours after this post was published, my Goodreads profile was cleaned of the offending titles. However, the garbage books remain available for sale at Amazon with my name attached.

I did file a report with Amazon, complaining that these books were using my name and reputation without my consent. Amazon’s response: “Please provide us with any trademark registration numbers that relate to your claim.” When I replied that I did not have a trademark for my name, they closed the case and said the books would not be removed from sale.