Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 43

September 21, 2023

3 Ways to Use Theme to Deepen Your Story

Photo by Almos Bechtold on Unsplash

Photo by Almos Bechtold on UnsplashToday’s post is by author, editor and book coach Sharon Skinner.

Theme is a critical element of story, but it is more than just the point you are making. Theme can be used to deepen reader experience, add subplots, increase conflict, ramp up tension, and heighten the overall narrative. It is the sweet syrup that drips and runs into all the nooks and crannies of a deeply layered story.

By staying mindful of your overall theme and thematic topics when writing and revising, you can develop a layered narrative that will resonate with readers both on a conscious and subconscious level and stay with them long after the book (or curtain) closes.

First, identify your themeTheme is foundational. It supports the plot and story like an iceberg, where the majority of it sits beneath the surface. The thematic foundation upon which the story is written drives much of what you can do with story. Having a solid theme—thematic topics and a thematic statement—will help you deliver a story with depth.

You can have more than one theme in your story. However, a single thematic statement keeps your story on track.

Thematic topics versus thematic statementThematic topics can be expressed with single words like love, hate, greed, fear, etc. A single story can touch on multiple thematic topics. A great example of this is Hamilton by Lin-Manuel Miranda. Hamilton touches on a multitude of topics, including power, love, hate, arrogance, loyalty, betrayal, loss, forgiveness…and more.

A thematic statement is what your book is about. Every book is about something. Every writer, whether they initially realize it or not, is making a point. A great way to get at theme is by asking yourself, “What’s the point?”

A thematic statement should be a complete sentence. Broken down to its most succinct, it can read like a line or a meme, but needs to be a complete independent phrase or sentence.

Examples include:

Love conquers all.To err is human.Money is the root of all evil.Absolute power corrupts absolutely.In Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton, ambition is a key topic. Getting from there to the thematic statement is as simple as giving Hamilton a clear line of dialogue: “I’m not gonna give up my shot.” This statement is a complete sentence that not only expresses the goal of the protagonist, Hamilton, it provides a thematic statement for the story. Alexander Hamilton is a man bound and determined to make something of himself by refusing to take no for an answer and taking his shot at greatness.

While Hamilton is a musical, it is also a great story—one that Miranda had to write and develop before bringing it to the stage—and provides some excellent examples for using theme to deepen story.

What is gloriously delicious about the thematic statement in Hamilton, what fills up the subconscious nooks and crannies and deepens the layers of this story, is how this statement is repeated and reflected upon. In the end (spoiler alert) the protagonist does give up his shot. This is the reason for his demise.

Once you have identified your thematic topics and developed a thematic statement, you can use them to deepen the reader experience. Here are three ways to do that.

1. Using theme to add conflict and barriersYour story’s thematic topics are a great source for developing conflict and obstacles for your characters.

When raising the stakes, you want to make it personal, not just the what, but why it matters to the character, not just what’s happening but why it’s meaningful to them.

Use your theme to create conflicts and barriers that bump up against your protagonist’s traits, push their buttons, test them, and strengthen and hone them to be able to face the final challenge that awaits them at the climax of the story. When the characters’ values, beliefs, and growth are at stake, the tension escalates, drawing readers into the story even further.Develop character relationships that are shaped by the thematic topics. How characters interact, clash, or collaborate can highlight the nuances of the theme and contribute to the story’s emotional impact.In Hamilton, Alexander isn’t the only one with great ambitions. However, the ways the characters pursue those ambitions differ drastically. Even allies can have conflicting viewpoints that stem from different interpretations of the theme.

Or, for example, if your theme centers around trust, pit your characters’ ideas and feelings around trust and/or breaking that trust against one another.

2. Using theme to develop subplots and parallel storylinesSubplots can serve as microcosms that mirror or contrast the main plot, allowing you to explore different facets of the theme. These subplots can also involve secondary characters who embody different perspectives on the thematic statement. Your subplots can argue for or against your thematic statement.

In Hamilton, one of the subplots is the duel that his son is involved in. His advice to his son, which is to fire into the air—literally giving up his shot—goes horribly wrong. This foreshadows what is to come. Hamilton’s grief and guilt over his son’s death becomes something he carries with him through the rest of the narrative. And so does the audience.

Which brings us to foreshadowing.

3. Using theme to foreshadowYou can easily integrate thematic elements into your story early on, foreshadowing the events and character developments yet to be revealed. This adds depth and resonance when readers reflect on earlier hints and realize their significance in hindsight.

Hamilton carries with him the guilt of his son’s death, an event that directly foreshadows what is yet to occur. One might think that Hamilton’s future action would be modified based on his son’s death. Yet, when the time comes, Hamilton follows his own advice, resulting in his tragic death. The audience is left reeling, wondering if he did it on purpose, or to prove a point, or…who knows what else?

“I’m not gonna give up my shot. I’m not gonna give up my shot.” He was not gonna give up. And Lin-Manuel Miranda knows exactly what he’s doing when the word shot is repeated over and over.

That’s good stuff. And you don’t consciously see it coming but, subconsciously, it’s layered in there for you. It elevates the story and deepens the experience.

With a story like that, you think about it long afterward. And isn’t that exactly what we want to give our readers? A long-lasting delicious story they can savor long after the final page.

September 20, 2023

How Can You Tell If You’re Starting Your Story in the Right Place?

Today’s post is by regular contributor Susan DeFreitas (@manzanitafire), an award-winning author, editor, and book coach. She is hosting a free masterclass for novelists on Sept. 22, Excellent Openings.

When I help my clients prepare the pitch materials for their novel, it’s not just the query and synopsis we focus on—it’s their opening pages.

Because it doesn’t matter how snappy that query letter is, or how promising that synopsis reads: If the opening pages of the story itself don’t suck the agent or editor in, those pages won’t have the desired effect on readers, which means the book won’t sell.

Needless to say, books that don’t sell are not the type of books agents and editors are interested in.

I’ve written elsewhere about the basics that pros are looking for in the opening pages of a novel: A clear point of view, a compelling voice, compelling characters, specific details, and tension of some type.

I’ve also noted the less obvious things: an internal struggle/vulnerability/weakness that signals the beginning of a character arc; one or more story elements that raise questions, thereby stimulating the reader’s curiosity; and well-integrated backstory.

But none of that answers a burning question so many of us have: How do I know if I’m actually starting in the right place?

After all, there are many different places in the overall timeline of your novel that your story could begin. So what makes one option superior to another?

Beginning writers tend to waffle around at the beginning of a story with a lot of what some folks refer to as “throat clearing”—hence the common injunction to get things moving quickly, and to get the inciting incident on the page as soon as possible.

But take it from me, because I’ve seen it many times: Openings written to the letter of this advice are generally either unintelligible, hard to care about, or both.

“Get the inciting incident on the page as soon as possible” is good advice. But it’s important to understand what “as possible” actually means.

After all, we could all start with The Thing That Sets the Plot into Motion, right? That is always actually possible, in the most basic sense: we could start with the car crash, the aliens landing on the front lawn, the mysterious letter arriving in the mail, or what have you.

But published novels that actually do so are rare. And even movies generally don’t attempt to start with the fireworks of the inciting incident, despite screenwriting’s focus on action, action, and more action.

They aren’t doing that because we first need enough information to understand what the inciting incident means to the protagonist, and why we should care. And to accomplish that, you generally need to get three things on the page before the inciting incident of your novel.

1. Basic contextIf we have no idea where the story is taking place, and the basic context of the protagonist’s life, we cannot understand what the inciting incident means.

Let’s say, for instance, that you’re writing a space opera in which the protagonist is the first mate on a faster-than-light ship bound for a utopian settlement on a rugged, borderline uninhabitable planet on far reaches of the galaxy—and the inciting incident is a blow to the ship’s hull delivered by a hitherto-unknown alien species.

In order for us to understand what that event means in this story, you need to start in a place that allows you to establish the important bits here: the mission of the ship, the sorts of people aboard, and why they decided to pack up their entire lives for Planet X.

You probably also need to start in a way that allows you to establish how far the ship is away from that planet, what recourse to help or aid they may have, and what is currently known (if anything) about alien species in general.

2. ProblemsYour opening also needs to establish who the protagonist of the novel is—and whoever that is, we need to see some problems in this person’s life well before this new alien species decides to ram the hull of their ship with disagreeable bits of antimatter.

In storytelling terms, problems are some sort of external trouble that’s indicative of an internal issue. And though it may seem counterintuitive, it’s actually these sorts of issues that make us care about the protagonist (white setting up what the inciting incident will mean for them, emotionally speaking).

For our space opera, let’s say the external trouble is a power struggle between the first mate and the arrogant chief engineer, which results in a few stern words from the captain to the first mate: If you don’t have what it takes to enforce my authority on this ship, I’ll find someone who does.

And let’s say that this, along with the internal narration of the protagonist, reveals the protagonist’s internal issue: She has imposter syndrome, despite her long list of accomplishments, and therefore fails to command respect.

3. What the protagonist wants, and whyAnd this in turn helps to establish the third essential ingredient of our opening trifecta, which is what the protagonist longs for—which is to say, what they want.

In this case, let’s say that what the protagonist wants is to be respected as a leader.

And why do they want that? Perhaps because her mother was a legendary ship’s captain. Perhaps even the captain of the ship that established the original utopian settlement on this distant, inhospitable planet.

All told, that’s the context we need in order to understand what it really means when this new alien species takes aggressive action against their ship, killing the captain in the process—and making our first mate with imposter syndrome the new captain of a ship under siege.

Will our first mate successfully navigate the fraught territory of first contact? Will she manage to quell the infighting that arises on her ship, and keep the chief engineer from leading a mutiny—long enough to unravel the truth about Planet X, and what really happened to the utopian settlement there?

All that remains to be seen. But given this sort of setup, chances are good that the reader will actually care enough about the protagonist, and understand enough about the story, to read on.

Could this story actually start with the aliens ramming the hull, and then backtrack to cover all of those essential bits I’ve spoken to here? Sure. But that’s a complicated maneuver, and one that would be hard to pull off (maintaining forward momentum with the storyline following that event, while also backtracking to cover the story’s basic bases).

The stronger tactic, generally speaking, is to do what 99 percent of all those books and movies you love actually do: Start just long enough before the inciting incident to establish these three things—the context in which the inciting incident will occur, the main problem in your protagonist’s life prior to it occurring, and what it is this protagonist of yours longs for in life.

Once you’ve established those three things in your novel—whether it takes you three pages or thirty—your reader will be ready for the inciting incident.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join Susan for a free masterclass for novelists on Sept. 22, Excellent Openings.

September 19, 2023

Finding the Funny: 8 Tips on Writing Humor

Photo by Franco Antonio Giovanella on Unsplash

Photo by Franco Antonio Giovanella on UnsplashToday’s post is by author Joni B. Cole, author of Party Like It’s 2044: Finding the Funny in Life and Death.

When I was in elementary school, I can remember being told by more than a few kids, “You think you’re funny but you’re snot.”

Well now, all these years later, the laugh is on those poopyheads because, apparently, I am funny. Or at least the folks at the Erma Bombeck Writing Workshop think so because they’ve honored me with the distinction of “Humor Writer of the Month,” in conjunction with the release of my new essay collection Party Like It’s 2044: Finding the Funny in Life and Death.

But am I a humor writer?

I never thought of myself that way, at least not until after reading the reviews of my first essay collection published over a decade ago. The majority of the essays in that collection dealt with difficult life experiences: my father’s infirmity due to a stroke; friendships cleaved over politics; the ache of separation as my growing daughters started to assert their independence. (What’s so funny about your middle-schooler threatening mortification if you chaperone her class field trip? Had she seen some of the other mothers?)

Because I had to relive painful personal experiences while writing those essays, I was taken by surprise at the tenor of the reviews of that book: “riotously funny…” “honest and hilarious…” “Roll-on-the-floor funny…”.

But of course, being funny can happen even when you don’t exactly feel like laughing. Humor doesn’t discriminate and can sneak into all sorts of situations. I think about the time a woman who had taken several of my writing workshops died rather suddenly. She was my age, meaning she was way too young to be struck down; plus I hadn’t even been aware that she was ill. I felt terrible for her family but (it’s embarrassing to admit this) I’d never liked this woman. For years I’d tried to unsubscribe from her monthly newsletter that I hadn’t even subscribed to in the first place. Then this woman died and her newsletters still kept showing up in my inbox, which I had to admit was kind of funny.

In life, I suspect we’ve all been reminded that humor and gravitas are not mutually exclusive. As a writer, however, I rarely paid attention to this reality. In retrospect, I find it rather funny (funny peculiar, not funny ha ha) that I overlooked humor as a narrative device, particularly because I am what one reviewer of my new essay collection calls, “a writer’s writer.” She went on to refer to me (facetiously, I hope) as “that A+ student you always hate.” (An A+ student! Take that Professor Chesney! Now maybe you’ll rethink that low pass you gave me in your creative writing class.)

In all seriousness, being called a “writer’s writer” is a label I truly appreciate because I take it to mean my work shows how much care I put into the structure, the scene selection, the pacing, the verb choices, the metaphors within my stories. Typically, my creative process is to revisit and revise everything about a googol times. Yet I had never thought to look specifically at the humor in my work, at least not until after my first book fell into this category.

To learn more about the craft of humor writing, I googled “how to write humor,” and the first thing I learned is that words with the letter k are funny—advice that can be traced back to the days of vaudeville. After that, however, I stopped googling the topic. I’m not sure why; maybe because I worried that studying the craft of humor writing might take the fun out of my funny. I know this is ridiculous reasoning, just like I know that writers who refuse to get feedback because they think it might compromise their work are missing out on one of the best resources we have to write more and write better.

Even though I stopped researching how to write humor, I did start paying a lot more attention to this feature of my work. What made something funny? How did the humor enhance the story? Where did I get in my own way? I think this attentiveness has served my essays in myriad ways. For starters, it has helped sharpen my prose. It also has presented me with unique opportunities to deepen characterization, bring into greater relief the poignancy of a scenic moment, and elevate the work overall.

Way back when my first collection was put into the humor genre, it sometimes felt like a mixed blessing. Many times I’d find myself thinking, I’m riotously funny! While at the same time thinking, How the hell did I manage that? Becoming conscious of something you’ve been doing autonomically can do a number on you, like when you start thinking about breathing and then you can’t breathe normally.

Maybe for this reason, I still hesitate to call myself a humor writer. On a related note, when an interviewer references my new book as a collection of “literary humor essays,” I make sure they know which of those two descriptors I prefer. That said, I love the idea of making readers laugh.

While I don’t see myself as an authority on this genre, I have picked up a few tips by tuning in to my own process, and by reading (reading as a writer, that is) notable humor writers who have authored books that make me laugh out loud…and notable humor writers who have authored books that leave me cold. And therein lies an important lesson I have learned in writing and in life—that humor is subjective. You may think you’re funny, while others think you’re snot. (But who cares what those poopyheads think!)

8 tips on writing humor1. Humor…humanity. There’s a reason those words share the same root. You know what’s funnier than a banana peel, or a joke, or puns, or even words with the letter k? People. Ordinary people, including yourself. Even in the most difficult situations, people are funny, if you take the time to pay attention to what makes all of us all too human.

2. Listen in. Paying attention to what you or the people around you are doing and saying is one way to tap into the funny. But paying attention to the thoughts that run through your head—a treasure trove of weird and wonderful material—is often an even richer resource for humor, and a meaningful way to get to know how your mind works.

3. Show, don’t mock. Making fun of people is not funny. Punching down is not funny. But showing characters on the page through their actions, details, dialogue, and internal monologue, now that can lead to successful humor. Why? Because it allows readers to form their own judgments about the character. Instead of trying to force the humor, it lets us decide for ourselves whether we should laugh at (or with) the people on the page.

4. Collect little humor gems. Like this text I just received from Xfinity, my telecommunications provider that has been trying for several hours to get me back online. Good news—your Xfinity service was restored at approximately 1:43 p.m. I’ll have to use that in some future essay—approximately 1:43 p.m.

5. There’s nothing funny about a blank page (or a first, or second draft…) At least in my case. In fact, my early drafts are usually pretty dry and uninspired, but that’s okay because I know how to find the funny, almost always in the process of revision and line editing.

6. Avoid too much self-deprecation. Yes, being up front about your quirks and weaknesses makes for powerful true stories. But overdoing the crazy for comic effect, at least in a personal narrative, can quickly read false and feel tiresome.

Bookshop • Amazon

Bookshop • Amazon7. Less is more. If you’re trying to make every scene or line a laugh riot, you’re trying too hard. I fell into this bad habit for a time, maybe because I felt the pressure to continue to be “roll-on-the-floor funny.” Eventually, I curbed that futile and counter-productive impulse and now I’m not funny. Unless it’s in service to the story.

8. Back to k words. The days of vaudeville may be long gone, but this truth persists. Some sounds really are funnier than others, and the same goes for certain words, depending on the context. I’ll never forget when I was struggling with a certain detail in an essay and swapped out the name “Citibank” for “Deutsche Bank.” So much funnier! (At least I think so.)

September 14, 2023

I Received Conflicting Advice on My Query Letter. What Now?

Photo by Thirdman

Photo by ThirdmanAsk the Editor is a column for your questions about the editing process and editors themselves. It also features first-page critiques. Want to be considered? Submit your question or submit your pages.

Today’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Book Pipeline. FINAL DEADLINE: Friday, Sept. 15th for the 2023 Book Pipeline Unpublished contest. Last chance to compete this season! Awarding $20,000 to authors across 8 fiction & nonfiction categories. Multiple writers have signed with top lit agents and been published over the past few seasons. Register now.

Question

QuestionA few months ago, I submitted my query letter to a well-known, respected query editor, and at the same time to a writing podcast (Print Run—I’m a Patreon member). I got very positive feedback from the show. The agents had small suggested changes, but they liked how clean and simple the query was.

Feedback from the paid editor was much less positive. She said the query was basically only a concept and I needed to significantly expand it to explain a lot more.

I rewrote the query letter as the editor suggested. My gut says the original query was better. But…I paid for professional feedback, so I feel obligated to go with that professional’s opinion.

Do I listen to my gut and the two unpaid professionals? Or listen to the paid editor? I suppose a third option is to try querying with both letters to see if I get a better response to one versus the other.

—Querying in California

Dear Querying in California,Have you ever gotten a bad haircut? Back when the “Rachel” was a big deal, I asked for one. I’m sure it discomfited the whole salon when I locked myself in the bathroom and cried on the floor at how bad I thought I looked. The stylist gave me exactly what I asked for, but it still wasn’t me.

Point being, getting what you paid for isn’t always getting what you need.

If it helps you feel better about the money, average it out—you got advice from three professionals and paid for one. Agents Laura Zats and Erik Hane from Print Run have seen thousands of queries, and they liked yours. Your query sold your book to their taste. Their taste. Another person thought you needed something different, to suit—you guessed it!—their taste.

We will always get conflicting feedback. If one friend-reader loves your manuscript opening, another may think it’s too slow. One agent’s “I love your concept and can’t wait to read more” is another agent’s form rejection. Since your query has already been read in a public forum, let’s look at some highlights.

The original query:

RACING HEARTS is a 81,000 word, single-POV, standalone Contemporary Romance. It would appeal to fans of Head Over Heels by Hannah Orenstein, Part of Your World by Abby Jimenez, and From Lukov With Love by Mariana Zapata.

Your metadata, the nuts-and-bolts info about the book, is very clear. Word count, genre, and two details specific to your genre: that this book is told in one POV and it’s not part of a series.

Katherine Parker doesn’t have dreams, she has plans. They include: perfectly balanced macronutrients; workouts, scheduled in fifteen minute increments; and, one day, rowing for gold in the Olympics. Her plans do not include getting dumped by her jerk-of-a-boyfriend right before her World Cup final. Kath loses by a mile. Then she’s promptly kicked off the team and out of the only home she’s ever loved–the Olympic training center.

Here, we run into a hitch I call “did-not-didn’t.” Tell us what Katherine does do/have/want, rather than opening with the opposite and switching, which jars the reader. Plus, the boyfriend’s clearly a jerk from context. How about this instead:

Allison’s revision: Katherine Parker’s perfectly balanced diet and meticulously scheduled workouts are going to take her to row for Olympic gold. But when her boyfriend dumps her right before her World Cup final, Kath finishes last and gets kicked off the team and out of the only home she’s ever loved—the Olympic training center.

Your next paragraph:

Okay, new plan. With only half a summer to win back her spot–and zero bandwidth for love–Kath returns to her hometown. Unfortunately, she’ll have to train alongside a gaggle of high school rowers and their coach, Adrian Crawford. And Adrian has opinions. Like, instead of supplement-stacked smoothies, he thinks rest days should be spent with corn dogs and mini golf. Worse, he has wide shoulders that even a rower would envy and, when he looks at Kath, he sees more than lists and neuroticism. Perfectly laid plans in tatters, Kath finds herself falling for this full-hearted coach. But if she’s serious about the Olympics–and moving back to the training center–how can her future include Adrian?

The “Okay” diminishes the stakes that are about to be beautifully set up! She’s got a ticking clock, a compelling reason to be in close proximity with the love interest, and a compelling reason not to get together. Perfect romance setup, and this also reveals some of the book’s snappy, contemporary voice.

As a former national team member and resident of the Olympic Training Center in Lake Placid, New York, I bring authenticity and passion to this project. I now live in Sacramento, California with my husband and fun-loving cockapoo. This novel would be my debut.

Great bio. I’d take out “authenticity and passion” because those are a bit Insta-influencer-y to say about oneself, but overall, it’s tight, smart and intriguing.

Let’s take a look at the revised query you wrote after paid feedback. In the new query, the opening paragraph is the same. There’s a small adjustment at the end of the paragraph with the set-up:

Kath bombs the race. Then, she also loses her spot on the national team, her residency in the Olympic Training Center, and all of her remaining sponsors.

But in the original, “the only home she’s ever loved” suggests backstory and existing conflict in Kath’s life. That she doesn’t have much of a support system, which raises the stakes. Losing sponsors means losing income, but what the reader cares about is her heart. But what if we work them into the second paragraph?

Allison’s revision: With only half a summer to win back her spot–and zero bandwidth for love–Kath returns to her hometown. Without sponsors to foot the bill, she’ll have to train alongside a gaggle of high school rowers and their coach, Adrian Crawford.

Now she has a reason to train with high schoolers. More of the revised query:

It’s about as hopeless as a cracked hull.

Ouch. This sounds like an older voice. A gee-shucks voice.

That is, until she’s given a deal to train under Adrian Crawford, her hometown’s high school coach who’s in the running for an elite-level job. If Kath can give him an unbiased evaluation–and get top three at Pan Ams in two months–USRowing will give her the spot back.

Her deal, his job, her evaluation, and a race and a time span and an organization—plus, these are all calculated, business decisions, not romance. They belong in the book but aren’t needed in the query.

Unfortunately, Adrian loves to veer off plan. Like, instead of grinding out laps in an inlet, he has Kath enduring open-water waves. And instead of smoothies and stretching, he thinks rest days should be spent with corn dogs and mini golf. Worst of all, Kath isn’t so irritated by these disruptions. In fact, for the first time in a long time, she’s actually happy.

In this paragraph, your revision uses a nice technique—the conflicts between them are a little more directly related to character. We’re seeing what he does that makes her crazy instead of what he thinks.

Yet, falling for this full-hearted coach is a terrible idea. Love, after all, got her into this damn mess in the first place. Also, Kath is reviewing him for a job. Finally, she’s supposed to be serious about the Olympics and moving back to the training center. So, how can any of her future plans include Adrian?

“Damn mess” = double ouch. And listing four of Kath’s reasons as equally important makes none of them important.

Strategically, to sell a book, this query is still reasonably solid. We’ve got conflict and stakes, and the evolution of the relationship is clear.

But it’s not your voice.

The same details—lost race, high school training environment, hot coach-she-can’t-fall-for are in both queries. But one sounds like fun contemporary romance and one sounds dated.

You already know which query to use, with a couple of tweaks, so I’ll answer the question you didn’t ask:

Did I waste my money?

Nope.

Paying for feedback is a great idea for those who can afford it. When I was querying, I bid at charity auctions in which agents who otherwise didn’t do query critiques donated their services. And agents and editors do give conflicting advice, because their taste differs. Someone’s great haircut is someone else’s nightmare.

But any feedback is valuable. When you receive it, pay attention to your own reactions. What makes you think, “Oh yeah, I hoped that would work but it didn’t?” What makes you push back? Then analyze why. Why should the query/sentence/story be your way and not the other way? What can you do more of in your writing to support that choice?

Even feedback we disagree with is valuable—if we take that next step.

Today’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Book Pipeline. FINAL DEADLINE: Friday, Sept. 15th for the 2023 Book Pipeline Unpublished contest. Last chance to compete this season! Awarding $20,000 to authors across 8 fiction & nonfiction categories. Multiple writers have signed with top lit agents and been published over the past few seasons. Register now.

September 13, 2023

The Hallmarks of a Bad Argument

Photo by Yan Krukau

Photo by Yan KrukauNote from Jane: Today’s post is somewhat tangential to the usual focus of this site, but I’d argue—for nonfiction writers anyway—knowing how to make a decent argument is fundamental to persuasive writing, op-ed writing, and overall literary citizenship. It’s something that I taught in writing classes, in fact, because the students needed the information. Desperately.

Last month, when I was writing and commenting on the AI fraud situation, I encountered some of the most voluble debate of my career—along with some of the most egregious straw-man arguments I’ve ever seen. Sometimes I wondered if people were serious about the points they were making or just really confused. In any event, I often wished for more good-faith arguments from people interested in thoughtful debate.

I have been a subscriber to a newsletter called Tangle for the better part of a year now. It looks at political issues and current events in the US and summarizes what people on both sides are saying. I greatly appreciate how it engages in thoughtful and reasoned debate. Recently, I recommended it in my free newsletter, Electric Speed, and the people at Tangle reached out to me to see if I’d be interested in cross-posting one of their articles on how to make better arguments—by avoiding really bad ones. I immediately said yes.

Because Tangle mainly covers political news and events, the examples you’ll find here are drawn from the political arena. It is probably the first and last time you’ll ever find overtly political content at this site. Keep in mind it’s to illustrate the hallmarks of bad argument and not meant to invite everyone into a political debate. For that reason, I’m turning off comments on this post due to the inevitability of that happening.

If you do wish to comment on this article (in a non-political fashion), you can reach out to me directly through my contact form, or you can comment on social media where I will be sharing this post (Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn). Political comments will be deleted swiftly.

This post is by Isaac Saul, founder of Tangle—and adapted from a Tangle article published on June 23, 2023.

We need more debate.

I’m a firm believer that one of the biggest issues in our society—especially politically—is that people who disagree spend a lot less time talking to each other than they should.

Earlier in June, I wrote about how the two major political candidates are dodging debates. The next week I wrote about how a well known scientist (or someone like him) should actually engage Robert F. Kennedy Jr. on his views about vaccines.

In both cases, I received a lot of pushback. There are, simply put, many millions of Americans who believe that some minority views—whether it’s that the 2020 election was stolen or vaccines can be dangerous or climate change is going to imminently destroy the planet or there are more than two genders—are not worth discussing with the many people who hold those viewpoints. Many of these same people believe influential voices are not worth airing and are too dangerous to be on podcasts or in public libraries or in front of our children.

On the whole, I think this is wrongheaded. I’ve written a lot about why. But something I hadn’t considered is that people are skeptical about the value of debate because there are so many dishonest ways to have a debate. People aren’t so much afraid of a good idea losing to a bad idea; they are afraid that, because of bad-faith tactics, reasonable people will be fooled into believing the bad idea.

Because of that, I thought it would be a good idea to talk about all the dishonest ways of making arguments.

The nature of this job means not only that I get to immerse myself in politics, data, punditry, and research, but that I get a chance to develop a keen understanding of how people argue—for better, and for worse.

Let me give you an example.

Recently, we covered Donald Trump’s fourth indictment, when a grand jury in Fulton County, Georgia, indicted former President Donald Trump and 18 others over allegations of a sprawling conspiracy to overturn Joe Biden’s election victory in Georgia. As usual, we got some feedback and criticism from our readers—which we welcome. A couple people asked why Hillary Clinton isn’t also getting indicted, since she also has disputed that she lost a fair and open election.

This, of course, got me talking about the differences in these cases. Clinton conceded the election the night it was called, Trump didn’t. Clinton’s supporters didn’t swarm the Capitol hoping to overturn the results while she—as president—was silent. Trump’s supporters did, and he was.

Then we started having a conversation about what Hillary Clinton did do. She did say that the election was illegitimate and that Russia tampered, and continues to. She did use a private email server…

And now the topic of conversation has changed, from “did Trump deserve to be indicted” to “should Hillary Clinton have been indicted?”

This is an example of “whataboutism,” where the person you’re talking to or arguing with asks you about a different but similar circumstance, and in doing so changes the subject.

WhataboutismThis is probably the argument style I get from readers the most often. There is a good chance you are familiar with it. This argument is usually signaled by the phrase, “What about…?” For instance, anytime I write about Hunter Biden’s shady business deals, someone writes in and says, “What about the Trump children?” My answer is usually, “They also have some shady deals.”

The curse of whataboutism is that we can often do it forever. If you want to talk about White House nepotism, it’d take weeks (or years) to properly adjudicate all the instances in American history, and it would get us nowhere but to excuse the behavior of our own team. That is, of course, typically how this tactic is employed. Liberals aren’t invoking Jared Kushner to make the case that profiting off your family’s time in the White House is okay, they are doing it to excuse the sins of their preferred president’s kid—to make the case that it isn’t that bad, isn’t uncommon, or isn’t worth addressing until the other person gets held accountable first.

Now, there are times when this kind of argument is useful, and sometimes even enlightening. If we are truly asking where the line for prosecutable conduct is for a presidential candidate, it’s useful to find precedent and see where it is being applied inconsistently. If we’re asking “is the government consistent,” comparing Clinton, Trump, Biden, Nixon—it’s all on the table. The same is true if we’re asking about the bias of media organizations, and seeing if they cover similar stories differently, if the subject of the story is the major element that’s changing.

But if I write a story that says your favorite political candidate answered a question in a very poor way, and you respond by saying, “Well, this other politician said something bad, too—I think even worse. What about that statement?” That wouldn’t be helpful, or enlightening.

Furthermore, context is important. If I’m writing about Hunter Biden’s business deals I may reference how other similar situations were addressed or spoken about in the past. But when the topic of discussion is whether one person’s behavior was bad, saying that someone else did something bad does nothing to address the subject at hand. It just changes the subject.

Straw man argumentsThis is another common tactic, and it’s one you have probably heard of. A straw man argument is when you build an argument that looks like, but is different than, the one the other person is making—like a straw man of their argument. You then easily defeat that argument, because it’s a weaker version.

For instance, in a debate on immigration, I recently made the argument that we should pair more agents at the border with more legal opportunities to immigrate here, a pretty standard moderate position on immigration. I was arguing with someone who was on the very left side of the immigration debate, and they responded by saying something along the lines of, “The last thing we need is more border agents shooting migrants on the border.”

Of course, my argument isn’t for border agents to shoot migrants trying to cross into the U.S., which is a reprehensible idea that I abhor. This is a straw man argument: Distorting an opposing argument to make it weaker and thus easier to defeat.

Unfortunately, straw man arguments are often effective as a rhetorical tactic. They either derail a conversation or get people so off-track that their actual stance on an issue becomes unclear. For the purposes of getting clarity on anyone’s position or having an actual debate, though, they are useless.

The weak manThere are different terms for this but none of them have ever really stuck. I like Scott Alexander’s term, the weak man, which he describes this way: “The straw man is a terrible argument nobody really holds, which was only invented so your side had something easy to defeat. The weak man is a terrible argument that only a few unrepresentative people hold, which was only brought to prominence so your side had something easy to defeat.”

The weak man is best exemplified by the prominence of certain people. For instance, have you ever heard of Ben Cline? What about Marjorie Taylor Greene? I’d wager that most of my readers know quite a few things about Greene, and very few have ever even heard of Ben Cline. Both are Republican representatives in Congress. One is a household name, and the other is an under-the-radar member of the Problem Solvers Caucus. Why is that?

Because Greene is an easy target as “the weak man.” Democrats like to use her to portray the Republican party as captured by QAnon, conspiracy theories, and absurd beliefs because they found social media posts where she spouted ridiculous ideas about space lasers and pedophilia rings.

The weak man is largely responsible for the perception gap, the reality in our country where most Democrats vastly misunderstand Republicans and vice versa. For instance, more than 80% of Democrats disagree with the statement “most police are bad people.” But if you ask Republicans to guess how Democrats feel about that statement, they guess less than 50% disagree; because the weak man is used so effectively that it distorts our understanding of the other side’s position.

Anecdotal reasoningAn anecdote is a short story about something that really happened. Anecdotal reasoning is using that real event to project it as the norm, and then make an argument that your lived experience is representative.

Frankly, I’m hesitant to include this one in the context of today’s post, because I do think politics are personal—and personal experiences should be shared and considered. They are often enlightening, and anyone who reads Tangle knows I regularly lean into personal experience. But they can also be a trap. Anecdotal arguments are dangerous because they can prevent people from seeing that their experience might be the exception rather than the rule.

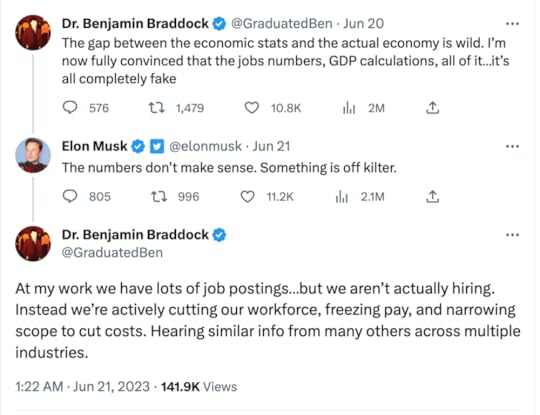

We actually just had a great example of this, too. As you may have heard, our economy is—by most traditional measures—doing well right now. Unemployment, for instance, is near an all-time low. At the same time, though, the tech sector (which is a fraction of the economy) has been experiencing a lot of layoffs and downsizing. This has left many people in tech concluding that the job numbers are somehow wrong or being fudged. Take a look at this exchange on X/Twitter:

This is a classic example of an anecdotal argument. Because personal experiences are so powerful, we struggle to see beyond them. While anecdotes can add color or create context, they shouldn’t be used to extract broad conclusions.

Circular reasoningI would never make one of these bad arguments. And because I wouldn’t make a bad argument, this argument I’m making isn’t a bad argument. And I am not a person who makes bad arguments, as evidenced by this argument I’m making, which isn’t a bad argument.

Exhausting, right? That’s an example of circular reasoning, which uses two claims to support one another rather than using evidence to support a claim. This style of argument is pretty common in supporting broad-brush beliefs. Here are a few examples:

Women make bad leaders. That’s why there aren’t a lot of female CEOs. That there are not a lot of female CEOs proves that women are bad leaders.People who listen to Joe Rogan’s podcast are all anti-vaccine. I know this because RFK Jr. was recently on the podcast spreading lies about vaccines, which proves that his anti-vaccine audience wants to hear lies about vaccines.The media is lying to us about the election in 2020 getting stolen. If the media were honest, they’d tell us that the election had been stolen. And the fact that the dishonest media isn’t telling us that is more proof that the election was stolen.Circular arguments are usually a lot harder to identify than this, and because they’re self-enforcing are often incredibly difficult to argue against. In practice, there are usually a lot more bases to cover that reinforce a worldview, and it’s difficult to address one claim at a time when someone is making a circular argument.

Of course, these aren’t all the ways to make dishonest arguments. There are a lot of others.

There is the “just asking questions” rhetorical trick, where someone asks something that sounds a lot like an outlandish assertion, and then defends themselves by suggesting they don’t actually believe this thing—they’re just asking if maybe it’s worth considering.

There is “black and white” arguing, where an issue becomes binary this or that (is Daniel Penny a good samaritan or a killer?) rather than a complex issue with subtleties, as most things actually are. There’s ad hominem argument, when someone attacks the person (“RFK Jr. is a crackpot!”) rather than addressing the ideas (“RFK Jr. is wrong about vaccine safety because…”). There is post hoc—the classic correlation equals causation equation fallacy (“The economy grew while I was president, therefore my policies caused it to grow.”). There are slippery slope arguments (“If we allow gay marriage to be legal, what’s next? Marrying an animal?”) and false dichotomy arguments (like when Biden argued that withdrawing from Afghanistan was a choice between staying indefinitely or pulling out in the manner that he did). There is also the “firehose” trick, or the Gish Gallop, which essentially amounts to saying so many untrue things in such a short period of time that refuting them all is nearly impossible.

In reality, a lot of the time we’re just talking past each other. There is one particularly annoying example of this I run into a lot, which is when people interpret what you said as something that you didn’t (close to a straw man argument), or ignore something you did say and then repeat it back to you as if you didn’t say it. This happened to me the morning I wrote this article on X/Twitter (of course).

It started when news broke recently about an IRS whistleblower testifying on damning text messages from Hunter Biden that were obtained through a subpoena. I tweeted out a transcript of the message Hunter Biden purportedly sent to a potential Chinese business partner. In the message, Hunter insists his father is in the room with him, and they are awaiting the call from the potential partner. Obviously, this would undercut President Biden’s frequent claims that he had nothing to do with Hunter’s business dealings.

I tweeted this:

“It’s a WhatsApp message, whose to say Joe was even in the room?” one user responded.

“Addicts tend to lie a lot, don’t they? Steal from grandma and such?” another person said.

“Hunter was a crack addict at the time. A crack addict lying for money??? No!!” someone else wrote.

Of course, I aired this possibility right there in my tweet. Again, emphasis mine, I said: “These texts from Hunter Biden insisting his dad was in the room are very, very bad. Hard to know if he was being honest or just bluffing, but Joe was just barely out of office and it looks extremely gross.”

But as people, we often come into conversations already knowing what point we want to make, and we’ll try to make it regardless of what the other person said. In one case, when I pointed out that I had literally suggested this very thing in my tweet, someone responded that it buttressed their point—as if I had never said it all.

Of course, just as important as spotting these rhetorical tricks is being sure you are not committing them yourselves. Dunking on bad ideas, styling ideas few people believe as popular, or using anecdotes to make broad claims are easy ways to “win” an argument. Much more difficult, for all of us, is to engage the best ideas you disagree with, think about them honestly, and explain clearly why you don’t agree. And even more difficult is to debate honestly, discover that the other person has made stronger arguments, adapt your position and grow. Because of the current media landscape, arguments that don’t contain these bad-faith tactics aren’t always the ones that end up in my newsletter, Tangle—but they are the kind of arguments I aspire to employ myself, and the ones I think we should all strive to make.

September 1, 2023

Does Your Multiple Storyline Novel Work? Questions to Ask Yourself

Photo by Aditya Wardhana on Unsplash

Photo by Aditya Wardhana on UnsplashToday’s post is by editor Tiffany Yates Martin (@FoxPrintEd). Join her on Friday, Sept. 15 for the online class Handling Multiple Storylines.

Writing a cohesive, layered, deeply engaging story can feel like conducting an orchestra where you’re also composing and arranging the music and playing every instrument. Add in multiple storylines—more than one POV or timeline—and the task becomes exponentially more complex.

Multiple storylines come with even more challenges than writing a single compelling story thread, but they can also offer faceted, layered stories that deepen the reader’s engagement and experience.

Whether you’re a plotter, a pantser, or something in between, a little forethought and planning can help prepare you for the challenges writing multiples can present. And asking yourself a few key questions can help you ascertain whether multiples are working in your story.

Are multiples even necessary?Oh, sure, it sounds like a fun idea—tell a particular story from the point of view of all the players involved, or weave together different timelines that intersect or affect one another. But not every story lends itself to the format. Watch for the warning signs that your story may not be the multiple you thought it was:

The storylines aren’t meaningfully connected to each other. There has to be a reason for these stories to be unspooling in the same manuscript. How do they affect, impact, or reflect one another? What makes each one intrinsic—what ties them together into one cohesive story arc, theme, or idea? Do they build on one another? Illuminate each other? Intersect, correlate, or even present alternate realities of a single storyline? How would the overarching story arc be diminished or fundamentally changed without all the storylines you’ve included?One storyline or character is consistently more fun to write—and more engaging to read—than the other. Almost every story will be difficult to write at some point—you may stall out, dead-end, or get lost in a detour. But if you or your early readers find yourself repeatedly struggling to get through one point of view or thread of the story, you might consider whether it’s actually meant to be a separate storyline. Writing (or reading) that feels like a slog can be the GPS equivalent of “make a U-turn”—a signal that you’ve gone off course and the route lies elsewhere.One thread peters out or you’re padding. If a storyline wraps up too early, or you find yourself struggling to fill chapters for it, that can be a warning flag. You may be trying to create a separate storyline from something that ought to remain backstory, or you may have a supporting character(s) who isn’t meant to be a POV character.One way to check this is to ask: What overall story are you telling, and whose story is it? Defining these answers clearly can help you determine which threads are intrinsic—as can the next question.

Is each storyline fully developed?A separate POV or timeline in a story is a promise to readers: that this thread is important, that it’s essential to the story in some key way.

If you introduce a POV, readers make an unconscious assumption that this character is essential—and thus we expect them to be fully fleshed out, intrinsic to the story, and to travel a clear arc. If the story encompasses multiple storylines or timelines, readers expect that each one will be fully developed, cohesive, and have its own story arc and resolution.

If not, it may be a sign that that particular thread doesn’t need to be a separate storyline, but might perhaps work better woven into the main story.

How does the story unspool?Structuring multiple storylines has been commonly diagnosed as a leading cause of anxiety, depression, hair loss, fatigue, and digestive issues.

Okay, maybe not in any medical journal, but any author who’s tried wrangling multiples can likely attest to the frustration factor of not only giving each storyline a compelling, fully developed story structure in its own right, but also weaving them together into one effective and cohesive whole.

Multiple-storyline story structure shouldn’t feel random or disjointed—ideally you will lead your readers fluidly between them so that each thread heightens, illuminates, reflects, and/or adds impact to the other(s). That means considering not only the structure and arc of each independently, but how they interrelate throughout the manuscript.

One protagonist may be “up” when the other is down and vice versa, or their arcs may parallel one another—but whatever is happening to one character in their thread should be germane to the other character(s)’ experience and arc in the other.

Romance novels, for instance, often alternate the hero’s and heroine’s POVs in a linear, chronological structure where each storyline offers another facet of or perspective on the other, but both move the overarching story forward, and each character is playing an essential role in furthering the arc of the other. In multiple timeline historical, a “past” thread often sheds light on a later or present-day thread.

In Between Me and You, Allison Winn Scotch alternates both POVs and timelines in telling the story of a couple’s courtship and eventual divorce from each of their perspectives: The wife’s story unfolds chronologically forward from meeting her husband as her career as an actor skyrockets, alternating with his thread told chronologically backward from the end of their marriage, when his once-promising career as a filmmaker is also on the rocks. When the two timelines intersect, the POVs stay separate but the timelines run together.

But a linear structure is far from the only possible choice for multiples. They may be “chunked,” with multiple chapters from one storyline grouped together (as in Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half); or they may be “tree branched,” following seemingly diffuse threads that all lead back to one central trunk (as in Junot Diaz’s The Brief, Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao). Or, one storyline may serve as a framing device for a main storyline, as in Colson Whitehead’s The Nickel Boys or Camille DiMaio’s The Way of Beauty.

Some stories use combinations of these and other techniques. Anthony Doerr in All the Light We Cannot See, for instance, alternates POV chapters chronologically in certain sections of the book, and also offers a linear progression of multiple timelines, one of which spans years while the other spans days.

There are no “rules” for how to structure multiple storylines—except that you should ensure that your structure allows you to answer yes to both of the following questions:

Do you reorient readers early in each storyline?Shifting between storylines can be confusing to readers, and you may risk losing them.

It’s crucial to let readers know not only which thread they’re in early in each transition, but to offer “connective tissue” to remind readers where you left the protagonist of each thread when they last saw them, and—if time has passed in the storyline—what has happened to the characters since.

The former can be accomplished through devices as simple as time or date lines, chapter titles, or section headings (for instance, a character’s name). But you can also do it with context—details about each story, the characters, historical facts, the setting, etc.—or with character voice (as in Shelby Van Pelt’s Remarkably Bright Creatures).

Do readers stay engaged in each storyline throughout?If readers don’t feel fully invested in a storyline, they may put your book down (and not pick it back up). Making sure readers stay fully engaged with each thread is largely a function of all the above—making each storyline essential, fully developed, and tightly structured.

But it’s also a more granular challenge: How do you engage readers deeply chapter after chapter, and keep them hooked and invested even as you move the “camera” away to do the same thing in each additional storyline—over and over again for the entire duration of the story?

Just as in chapter and section ends of single-storyline stories, do you leave readers with some unresolved tension, a question, or some other type of “cliffhanger” each time you transition to another thread? It’s especially crucial with multiples to end in medias res as well as begin there. You’re planting a hook each time you draw readers away from one story that will leave them eager to return to it—and then you take them exactly where they don’t want to go at that moment: to another thread.

But you drop another hook there, beginning the new thread also in medias res, plunging readers into the action, keeping momentum and stakes strong, and building them even stronger as the storyline unspools—before you repeat the process all over again.

Doing this consistently throughout results in the “unputdownable” stories where readers can’t stop turning pages, desperate to know what’s happening in one thread even as they get powerfully sucked into another.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Friday, Sept. 15 for the online class Handling Multiple Storylines.

August 31, 2023

Lessons from 23 Years as a Self-Publishing Novelist

Photo by karina zhukovskaya

Photo by karina zhukovskayaNote from Jane: In the earliest days of my career, I served as managing editor of Writer’s Digest magazine, and one of the nicest parts of my job was calling up winners of our writing contests, including the National Self-Published Book Awards. John Sundman was one of the winners I called—and one of the first self-publishing authors I came to know and consider a friend. I’m delighted that he reached out to me about his return to the writing and publishing space.

After four years of hard work with a well-known New York City literary agent, around Christmas 1999, I gave up on the traditional route and decided to publish my first novel, a Silicon Valley cyberpunk thriller called Acts of the Apostles, myself.

My agent, Joe, had guided me through endless rewrites and three rounds of submissions to publishers in New York and producers in Hollywood. We had some serious nibbles—big name editors took me to lunch, and over one weekend in April 1998, 26 producers read the manuscript in advance of an anticipated auction of the movie rights—but we never got an offer. Joe was willing to work with me on one last rewrite, believing we still had a chance of getting a million-dollar payday. But I had reached my limit. I was flat broke and my wife and children had had more than enough. My dream of literary stardom had cost them plenty.

I formatted the book, got an ISBN number, designed a cover, and somehow convinced a local printer to print 5,000 copies on credit. The printer released a few hundred books to me and locked away the remainder in their warehouse. The deal was that as I sold those books and paid down the bill, the printer would release the rest—in increments.

Desperate to generate some notice, I put the first 13 chapters of the book up on my obscure website. “If you want to read the rest of the book, send me a check for $15 and I’ll mail you a copy.”

I established an Amazon Advantage account and set off in my falling-apart car on a coast-to-coast book tour, pitching my book at hacker meets and scientific conferences, in Silicon Valley cafeterias, on street corners, and even at a bookstore or two. Over three weeks I sold enough books, barely, to cover my expenses. I made it back home by the skin of my teeth. I didn’t have enough money for a McDonald’s Happy Meal or one more tank of gas. I was defeated. I set aside my novelistic ambitions for good and got a day job, back in the world of tech, which I had left five years earlier.

But then a funny thing happened. Checks started showing up in my mailbox. They came from all over. Mostly from Massachusetts and California, but some from as far away as Italy or the Philippines. And with the checks, sometimes, came letters of encouragement. Glowing reviews started appearing on the internet too. Bookstores started faxing in orders. My Amazon ranking went from one million to one thousand.

And then one day while I was hard at work at my job at a software startup near the MIT campus, I got a phone call from an editor at Writer’s Digest magazine. Her name was Jane Friedman, and she was calling to tell me that Acts of the Apostles had won that year’s National Self-Published Book Award and that a check for $500 was in the mail.

Fast forward to 2023. I’ve been a self-publishing novelist longer than some readers of this essay have been alive. In addition to Acts of the Apostles I’ve published two novellas (Cheap Complex Devices and The Pains) and an alternate universe version of Acts, called Biodigital: A novel of technopotheosis.

I’ve also had plenty of day jobs—everything from freelance technical writing for Silicon Valley startups to long-haul truck driving. Whatever it took to pay the bills as I continued to work on my books.

This fall, in conjunction with a new novel, Mountain of Devils, I plan to publish new editions of my four existing titles (in English and in Spanish, ebook and paperback), each with a new introduction by a prominent writer. With people like Cory Doctorow, Ken MacLeod, David Weinberger, and John Biggs vouching for the value of my work, I confess that I feel somewhat vindicated. Those New York publishers who took a pass on Acts of the Apostles twenty-some years ago missed the boat.

I’m not going to address tactical topics such as how to format, publish and distribute your books, or on the pros and cons of recording your own audiobooks, or even how to write a good book in the first place. There are plenty of other authors who address such things; Jane’s resources page is a good place to start looking.

What I am going to offer here, rather, pertains to the mindset required to succeed in this business. Some of it may not apply to you, but it’s a good place to start.

10. Have a thick skin. You are going to encounter naysayers. Some of them may be quite obnoxious. It’s always good to listen to constructive advice, but you don’t owe anything to people who are out to bring you down.

9. Get out into the world. Make yourself known. Be proud. Don’t be shy now. Speak up! When people you’ve just met ask “What do you do?” reply, “I’m a writer.” Even if you’ve only sold one copy of your first book.

8. Get organized. This job entails writing, editing, book design and production, distribution and marketing. And that’s just for starters. Read, study, consider hiring a mentor if you can afford one. Make a plan, and keep track of your progress. You’re now an “authorpreneur.” You’ve got a business to run. Act like it.

7. Expect some failures. Some things just aren’t going to work out. You will make mistakes, and some of them will be embarrassing if not downright humiliating. Learn what you can and then move on.

6. Don’t chase bookstores. Sell direct, sell through Amazon, and through any local retail outfit that invites you. But don’t waste your time trying to get a distributor or to get into bookstores without one. If your book becomes a colossal hit, those bookstores will find you, I promise.

5. Your book(s) must be good. It’s true that some authors have had great success with books that are objectively pretty crappy. Some book gurus even tell you that quantity matters more than quality. “Don’t waste time trying to make your book perfect!” they say. “Keep cranking out titles!” That approach might work for some people, but from what I’ve seen, having a quality product offers a higher probability of success.

4. Be flexible. The publishing world changes fast. When I put the first 13 chapters of my first novel online for free download in 1999 and started selling my novels at hacker meets and scientific conferences, I was hailed as an innovator. There was no such thing as an ebook in those days; no Venmo or Paypal for electronic payments, and there was certainly nothing like BookFunnel to help you build your mailing list and find collaborators to work with. But as the world of self-publishing changed, I didn’t change with it, so now I’m playing catch-up. Don’t you do that.

3. Your mailing list is your greatest asset. It took me much too long to acknowledge that what all the experts were saying about this were right. Make growing your list one of your highest priorities.

2. Be kind. Be helpful. What goes around comes around. Be kind to your readers, be helpful to fellow writers, just try to be a decent person in general. I’m an old guy. I know what I’m talking about. Trust me on this one.

1. Being your own publisher is liberating. I’ve made some money doing this, but frankly, not a lot. I do have high hopes that that’s going to change with my forthcoming releases, but nobody can see the future. Maybe my big launch will be a bust. Yet I consider my self-publishing career a success, and I’m glad that I stopped beating my head against the “real publisher” wall all those years ago.

Being my own publisher forced me out of my comfort zone. It wasn’t always fun or easy, but it opened up a world for me. I’ve hand-sold thousands of books, and in so doing I’ve made hundreds of honest-to-God friends. I put together a panel at SXSW on “the future of the novel in the digital age,” and I even got Jane Friedman to moderate it. I’ve given talks at the DEFCON hacker conclave, in schools, and at the opening of a synthetic biology laboratory at the University of Edinburgh. All in all it’s been a blast.

Good luck! Let’s help each other!

There are lots of ways for indie writers to help each other out. Joint promotions, newsletter swaps, guest blog posts, podcast interviews, introductions, the list goes on. If you think you and I might be able to help each other, let me know. I’m open to suggestions.

August 30, 2023

How to Read to Elevate Your Writing Practice

Photo by cottonbro studio

Photo by cottonbro studioToday’s post is by book coach Robin Henry.

Writers are frequently advised to read more to improve their writing. The problem is, no one seems to tell them how to use reading to elevate their writing practice. Reading alone is not enough—osmosis is not a viable strategy for learning.

You’ll find books on this topic, such as Francine Prose’s Reading Like a Writer and How to Read Like a Writer by Erin Pushman, but they tend to take a generalist approach. They are usually aimed at beginning writers, and contain reading lists that would lay even an enthusiastic graduate student low. Classic literature is great (mostly)—I am a fan! But to write a book that will be a work of art and have a chance of succeeding in the modern marketplace, I suggest writers focus on more recent fiction for their writerly reading.

How to choose books for mentor textsThe first hurdle is choosing which books to use as your mentor texts. Selecting books can be challenging in the modern world, not least because we are spoiled for choice. Hundreds of books are published every year, and writers need criteria to craft their reading lists. Fortunately, as a librarian trained in collection development, I can help.

Read professional reviews rather than those on Amazon or Goodreads. They don’t have to be from the literary establishment (New York Times, LA Times, Washington Post, the Guardian), but they do need to be written by professionals, because you want to know that the books have been analyzed with some attention to plot, tone, character development, language, etc. Choosing books that have been professionally reviewed by at least two sources narrows the universe of books to a manageable number. “Best of” lists and literary prize lists are great places to find books to read, too. They usually include annotations, which can be helpful. Consider NPR, Booklist (the librarian’s favorite), Library Journal, librarian/library blogs, and literary podcasts.

After deciding which review sources or lists you will use, consider genre. Try to select a mix of genres, including the one you write in. One of the best ways to give yourself the distance you need to analyze books is to read outside your usual genre. You will see new ways of writing, as well as different kinds of plots and characters, which serve to feed the imagination. Try adding a little non-fiction, too. Human brains are great at seeing patterns, and varying the field in which one’s brain is searching will help bring novelty to your novel.

Finally, check your newly minted TBR pile for diversity. If you’ve skewed in a particular direction, consider going back to your review sources and seeing what other titles might take your fancy that are not in that demographic—either author or character-wise. Look for international books. Americans especially have a tendency to select American-centric titles. Branch out. NPR’s Books We Love and the international Booker Prize contain books from other countries, either written originally in English or translated.

Questions to keep in mind while you are readingNow that you’ve selected the book(s) you want to read, you are ready to think about a framework to use as you read. It is important to have questions in mind beforehand so that you know what to pay attention to.

In The Well Educated Mind, Susan Bauer suggests that one way to get at the deeper meaning of a book is to ask yourself, “What is the message the author is trying to convey, and do I agree with it?” By analyzing your own response, you will consider reader response versus author intent and how both affect the overall effect of a novel. What readers think the author intended may be different to the message a reader takes from the book. Often the most effective way to convey a message is through questions that the reader asks themselves about the novel. These may be big picture, story questions about human nature, or they may be plot-level questions. The best novels use both.

For example, in the novel I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai, there are many questions the reader could choose to focus on. However, if I consider the author’s intent, I land here:

(Story) How does society’s fascination with true crime reduce victims, especially women, to disposable people and wreak havoc on the lives of suspects, who may or may not be guilty, during the course of an investigation? (Plot) Who really murdered Thalia?The message she sends to me as a reader regarding the story question is that we make victims into girls who never had a chance, so that we can live with the fact that they were harmed. We reduce victims to disposable by blaming them or by arguing that it was fate. We justify the harm done during an investigation as collateral damage in the quest for justice, when in fact, there is no justice. On the plot level, you will know who the real murderer is by the end.

Other questions to ask about a book before you begin reading include nuts and bolts kinds of questions:

What are the basic “facts” of the book?GenreCharacters—who is the central character?Basic plot events and turning points—what is the most important event/decision point?Character arcWhat does the main character want?What stands in her way? (interior and exterior)What does she do to overcome this obstacle?What POV does the writer use?What is the beginning and the end—is there change over time?Finally, choose a few passages you find particularly beautiful and analyze them. Notice the rhythm, word choice, metaphors. What do they teach you about language use? What about the author’s writing did you find particularly enjoyable? Or not? Make notes to inform your own writing. When you see a word or an image you like, write it down so you can ponder it. Writing is a process, and it takes time to internalize the lessons you glean from the beautiful novels you read.

Close reading versus reading for enjoymentAs a former school librarian, I have spent hours in workshops about the different stages of reading enjoyment. “Stages of Growth in Literary Appreciation” by Margaret J. Early is from 1960, but modern scholarship has not altered her basic thesis. There are three stages in reading/literature appreciation. Most people read in all three of them and move between them. When we reach for a summer beach read, we are probably in Unconscious Enjoyment. We know we like it, but are not concerned with why we like it. When we reach for a thriller or a mystery, we are most likely in Self-Conscious Appreciation. We like it and we do care why. We care that the plot makes sense, that the characters are acting in ways that are logical in the story world. When we go looking for literary or upmarket fiction, we are usually reading in Conscious Delight. We know it will take some effort to read this book, but we also anticipate that it will be worth it. We want to think about big questions concerning humanity, we want to be asked to use our analytical powers to understand it. The reward is the experience of reading a deeply beautiful book.

The best writers write for all three stages, because readers come from all of them, and on any given day, they may slide to a different stage. Thus the rise of book club or upmarket fiction and genre fiction by literary writers. If you want your work to have lasting appeal, you will want to keep readers in mind and make it possible for them to enjoy the book no matter where they are. However, when you are reading like a writer, you must be in Conscious Delight. You must understand what you are reading and why; you need to be prepared to analyze it in order to apply the skills you see.

Annotating is one of the best ways to engage with a text. Unfortunately, many readers have been discouraged from writing in books. While you should not write in books you don’t own, annotating your personal copy is completely fine, and in fact I encourage it. Lest you think I am leading you down the garden path, historians study the marginalia in books for clues about what readers are thinking as they read. H. J. Jackson has written several fine academic books about this, including Marginalia: Readers Writing in Books and Romantic Readers: The Evidence of Marginalia. Give the future literary critics something to think about when your library is turned into an archive. Write in your books.

Take notes and flag places where you notice the answers to questions in the framework. Notice where the turning points of the story are. Read again and see if you notice foreshadowing on the second read that you missed the first time. Reading like a writer is a commitment, which is why you choose the books carefully.

Interrogate the text: How does it work to create emotion? How does the language sit with you? How does the writer achieve a spectacular plot twist or something else unexpected? Make notes and think about how it was done. Did an image or a small piece of interiority click with you? Did a choice of verb leap from the page? Make a note.

Apply the lessons to your own workWhen thinking about how to apply what you learn, take it one layer at a time.

Start with the message. What is your intended message to the reader? Do you have it in mind as you write? How do the characters’ choices reflect the message?Next, go to the plot events and character development questions in the framework. Do you see the obstacles (interior and exterior) in your own story? Does your story have the genre markers you see in other works? Does it have the basic plot elements you notice in the books you read?Think about point of view. Are the POV choices you have made the best ones to tell your story? What happens if you retell it from another POV—what changes? Who is narrating the story and how does the narrator’s voice impact the story? When you consider the narrators of the books you have read, what do you notice? How does the telling change with who tells the story?What is the change in characters over time? Be specific. For example, in I Have Some Questions for You, the narrator begins the tale as an unreliable narrator and the main character, but over time, she becomes more truthful and more confident as she uncovers the past, and by the end, she is completely honest with herself and the reader. How does your main character change over the course of the book?Finally, think about language. A possibly apocryphal story about Gustave Flaubert relates that he sometimes worked for hours on a single sentence. Whether or not that is true, art takes time. Using language well is not the purple prose of overwriting, but the true beauty of choosing just the right word for just the right sentence—conveying meaning on more than one level.If you embrace reading like a writer, it may ruin you for Unconscious Enjoyment, it’s true. The tradeoff is that it will open your eyes to the world of how to craft a beautiful and meaningful novel and how to appreciate on a deep level the skill that the art of writing well demands.

August 29, 2023

How to Successfully Pitch Op-Eds and Timely Cultural Pieces

Photo by Steve Johnson on Unsplash