Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 49

April 26, 2023

First Pages Critique: Getting a Handle on Pace

Photo by Nicolas Henderson (CC BY 2.0)

Photo by Nicolas Henderson (CC BY 2.0)Ask the Editor is a column for your questions about the editing process and editors themselves. It also features first-page critiques. Want to be considered? Submit your question or submit your pages.

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Author Accelerator. Is book coaching your dream job? Take the One-Page Book Coaching Business Plan Challenge to find out what kinds of writers you would coach, how (exactly!) you will help them, and how much money you can make doing it. Sign up for our $99 mini-course that launches in May.

A summary of the work being critiqued

A summary of the work being critiquedThe B*tch and the Boy: A True Saga of Fame, Greed, Betrayal, and Murder is about a brilliant man, John Markle, and his narcissistic mother, Academy Award–winning actress Mercedes McCambridge. The two have a love-hate relationship that drives him to kill his wife, children and himself. Because he blames his mother for his failures, the story expands the murder narrative to tell their intertwining life stories. It is a tale of family and relationships immersed in a sixty-year arc through the golden years of radio and World War II, to the glamour of Hollywood and elite schools, to an enviable career and a life built on fraud.

First page of The B*tch and the BoyNovembers in the quiet capital of Little Rock are cool and serene with leafy hardwoods coloring the roadsides and shallow valleys. The city spreads out along the southern bank of the Arkansas River as it flows southeast toward the end of its journey to the Mississippi at the lost town of Napoleon. Located in the center of the state, the terrain eases the foothills of the Ozarks into the flat lands of the Delta. The year was 1987 and the city was in transition with its early eastern downtown blocks forming its commerce even as its retail was following the population and moving further west.

A few blocks south of downtown, Dr. John Markle and his wife, Christine, did not follow the crowd west but chose to live in the heart of the city’s historic residential area. John worked long hours and wanted the location’s proximity to his office. He was a motorcyclist and liked speeding up Main Street toward the river, arriving at his office within five minutes. Located one house from the governor’s mansion, theirs is a tall, three story 1880 Queen Anne. Sited on a treeless corner hilltop, well above surrounding properties, to those driving along Main Street the structure jumps out as peculiarly stark: a lonely fortress ready to offer both protection and seclusion.

At 45, John had been a star for much of his life. In Little Rock he was serving as the economist and a vice president with Stephens Inc., the most influential Arkansas company and largest investment house off Wall Street. Eight years earlier he was brought in as the guru of futures trading from prestigious Salomon Brothers investment firm where he had once been a vice-president in New York City and seemed to know many of the luminaries on Wall Street.

After arriving at Stephens he quickly assumed a leadership role and established himself as an articulate and engaging speaker who offered insight into the turbulent economic landscape of the early 1980s. He also served as a leader and trainer to other traders and headed his own department. The billionaire brothers and owners of the firm, Witt and Jack Stephens, were pleased with his contributions and considered him “”the great team player.” They regularly called him up to the executive floor to speak to clients and attend many of their private luncheons, formally served by white jacketed waiters.

Continue reading the first pages.

Dear Peg,There are a lot of compelling, even flashy, elements to this story, right off the bat: an Academy Award–winning actress (even if not the very most famous actress), a “guru of futures trading,” elite schools, Hollywood, fraud!

And, most important, a crime. (Several, actually.)

There are many ways a writer can approach telling any story, but in the case of true crime stories, it’s conventional to jump in pretty close to the crime. This is especially true in the case of a story like yours, where the primary driving question isn’t so much What happened? as What really happened? or How do we make sense of what happened?

As far as I can tell from the material you sent, the broad facts of the story aren’t in question; this is not a “whodunnit” murder mystery kind of story. You know what happened, and readers who enjoy true crime will also want to know the gory details: Where were the bodies found, and in what state? What were they wearing? Who was killed first? What do you know about the weapon? Who found them?

Granted, this all seems a little bit gruesome, and maybe it’s true that this kind of morbid curiosity isn’t something to be proud of … but it’s also a very human impulse. If you’re going to tell a true crime story, you might as well lean into it. You want to hook readers, emotionally, to get them invested enough in the story to keep reading. You’re also making a promise up front that by the end, they’ll have more insight into this heinous crime, and an answer (perhaps more than one) to the question you pose in your supporting materials: “Why? Why does a respected investment banker brutally murder his wife and children?”

In fact, I should admit that as I was trying to get the shape of this story, I kept returning to the additional material (your author’s note) more than to your opening pages, which are on the slow/quiet side.

Let’s take a look.

“Novembers in the quiet capital of Little Rock are cool and serene…”

Starting with the physical setting of the story isn’t necessarily a bad idea, but it might be helpful to narrow the lens. Rather than taking the very wide view of Little Rock, generally, what if you started with the house, the “lonely fortress” where the deaths occurred. Did people generally think of it as a fortress or unapproachable, even before what happened? Did one of the first responders observe anything unusual, walking up to it on the night of the deaths? Is it vacant, even now, years later?

You can always go back at a quiet moment and paint a picture of fall in Arkansas, or Little Rock’s general topography, or insights into the local population’s migration to the western suburbs. If that seems especially relevant at some point.

Your author’s note, provided with the pages, start with the following:

“Telephones started ringing early on Monday morning…”

The telephones (though I want to know more: whose telephones? And how early?) are something happening. Not a scene, per se, but they lead to scenes, maybe: people making calls, people answering calls, lights going on in houses all over the city, cars driving through the night, lights flashing, people walking into that fortress up on the hill and seeing unspeakable horrors—except not really unspeakable, because you’re going to paint the picture.

Currently, in these first pages, there’s also a lot of back story, about John in particular. These paragraphs span a lot of time in a small space. In fact, there are almost several different time structures happening all at once, in a way that might be disorienting for many readers: We start with John at 45 (his age when he died, in November 1987). Then it’s eight years earlier, and then we take a quick jump back to his childhood for a paragraph, then another leap forward to “early October [1987],” when six years of fraud were discovered. There are a few more leaps: back to childhood, then after he married, and then the day he picks up the phone to ask Mercedes for help, she refuses him, and then he calls daily for five weeks. Finally, “two weeks into his suspension,” John starts writing a letter, and at some point after that, on November 13, he is fired. (The murders happen on the following Monday.)

All to say, it feels like you’re trying to cover a lot of ground in these opening pages. And while it’s hard to know exactly what path the book follows as a whole, it seems like a lot of this ground—John’s childhood and relationship with his mother, the fraud, the letter—will be important to cover in more detail and at a slower pace.

My advice for the beginning of the story, then, is paradoxically both to speed up and to slow down. Speed up, meaning get to some action—whether that’s the murders themselves, or the immediate aftermath. And slow down, meaning get a head of narrative steam going, stretch out a little into the storytelling and trust that if you keep doling out details, readers will stick with you for the bigger story you want to tell and the questions you want to explore.

Good luck with it!

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Author Accelerator. Is book coaching your dream job? Take the One-Page Book Coaching Business Plan Challenge to find out what kinds of writers you would coach, how (exactly!) you will help them, and how much money you can make doing it. Sign up for our $99 mini-course that launches in May.

April 25, 2023

The How, When and Why of Writing Autofiction

Photo by Designecologist

Photo by DesignecologistTodays post is by author Adele Annesi (@WordforWords).

As a writer and instructor of autofiction, I find the genre an inspirational way to explore pivotal life experiences. In this nexus of fact and fiction, writers can mine, select and transform their real life journeys, turning points and discoveries into story. First, let’s define the genre.

Working definition of autofictionShort for autobiographical fiction, autofiction uses elements of autobiography and fiction to examine decisive aspects of the writer’s life. The writer then melds these realities with fictional plot elements, characters and events in a way that often reads like memoir or autobiography. With the lines of fact and fabrication blurred, readers are engaged in wondering what’s real, what isn’t, and how they can figure out which is which. So whether you write fiction, nonfiction or both, at some point you’ll probably consider this genre. Here are its features.

Names: Autofiction writers may have the same name as or a name similar to that of their protagonist.Parallels: Autofiction includes similarities between the writer’s and protagonist’s life. For example, the protagonist may also be a writer so the story may explore the role of writing in the character’s life and may include elements of metafiction: writing about writing and storytelling.Uncertainty: In a genre that blurs reality, there is an organic tension in the story over what’s real and what isn’t. This engages the reader in thinking deeply about the work and the protagonist’s (writer’s) life.Autofiction examples:

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (2019): Named a Goodreads Choice Award Nominee for Best Fiction, this work by Ocean Vuong is a letter from a son to a mother that unearths a family history rooted in Vietnam and serves as a window into aspects of the son’s life his mother never knew. Every Day Is for the Thief (2007): This bestselling first novel, in diaristic form, by acclaimed Nigerian-American Teju Cole depicts a young man’s journey to Nigeria to discover his roots. A Death in the Family (2012): One of the Guardian’s 100 Best Books of the 21st Century, this novel series by Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgaard examines childhood, family and grief.All about adaptationThe auto aspect of autofiction often shares more with memoir than autobiography because the story the writer chooses to tell doesn’t usually cover their entire life. Rather, the writer selects key events, turning points and discoveries that revolve around and elucidate one main theme. Other characters, settings and events can be fabricated to support what the story is about.

To begin the autofiction journey, consider the exploratory dreamstorming technique described in From Where You Dream, by Robert Olen Butler. Here is Butler’s general principle. Go to your writing space, and give yourself time to remember, to watch yourself move through your life. The journey doesn’t have to be linear or chronological. As you recall your life, list your experiences and why they might figure into your story.

Once you have an initial list, differentiate it between events and turning points. Describe what led up to these occurrences, and note their outcome. Beside each, list what you learned or discovered. To develop these moments, consider this from The Situation and the Story, by Vivian Gornick. “Every work of literature has both a situation and a story. The situation is the context or circumstance … the story is the emotional experience that preoccupies the writer: the insight, the wisdom, the thing one has come to say [about the circumstance].”

Reflect on how to arrange your experiences and their depiction, as well as what you’ve learned, possibly in order of increasing clarity. You might save the most important discovery for last or use it as a prologue, promising the reader you’ll reveal how your discovery or change came about and how it impacted your life.

Last, decide how much to tell and how accurately to tell it. Writers are at liberty to decide how much of their life events they want to reveal and how precisely they want to reveal them. One way to decide is what twentieth-century English author (of the Lord Peter Wimsey novels) and essayist Dorothy Sayers described as “serving the work”, meaning whatever best accomplishes your vision for the story.

Revising and completing autofiction

All revision occurs in stages. In autofiction, perhaps more than other genres, the writer uses trial and error to decide whether to depict key story points as mini-scenes, straight narrative, dialogue, summary, or a combination thereof. It’s also important to balance how much of an insight to depict overtly and how much to present as interiority—what a character thinks/feels. And since your story’s theme can change, even in autofiction, consider writing the story first for itself, then revising it based on what you feel it’s really about.

My autofiction novel What She Takes Away (Bordighera Press, 2023) began with a real event—my family’s decision whether to move to Italy. Recalling that time, the warp and weft of family life, and the role of discovery in creativity inspired an entire novel. And if the writer is inspired, the reader will be, too.

Additional reading From Where You Dream by Robert Olen Butler: A must for writers seeking to escape mundane writing Elements of Fiction by Walter Mosley: How to master fiction’s most essential elements The Elements of Story by Francis Flaherty: A primer on key nonfiction techniques that also work for fictionWord for Words blog for writersApril 20, 2023

Why Beta Readers Lead You to Getting Paid for Your Writing

Photo by Pixabay

Photo by PixabayToday’s post is by author, editor and coach Jessica Conoley (@jaconoley). Join us on Thursday, April 27, for the online class Finding & Working with Beta Readers.

Asking someone to beta read for you is one of the first steps you will take toward becoming a well-paid, published, consistent writer. Because, for many of us, the beta reader process is the first time we must own the identity of: WRITER.

Owning your writer identity is the biggest mindset hurdle we face. This is especially true if you’re uninitiated and haven’t yet been published and/or paid for your work. Once you overcome this hurdle, you build up courage to reach for bigger opportunities (and pay checks) in your career.

Building up courage starts long before we are paid, published, or well-known. Building up courage happens in tiny decisions and actions, day after day, year after year. Building up courage starts the moment you realize your manuscript is polished to the best of your ability and you need to ask someone for an objective opinion on your work.

This is when most of us freak out. We no longer have the luxury of hiding in the security of secrecy. We cannot hoard our writing dreams and aspirations in silence any longer. To level up this project you must have objectivity, and the only path to objectivity is letting someone else read your words. To progress you must ask someone to read for you.

While you may think asking someone to read is just about feedback and learning if your characters resonate, you’re simultaneously stepping into the identity of WRITER. In the act of asking, you are forced to try on a new persona. A persona you may not feel you’ve earned. This is why you are scared to ask.

But, over time, after telling enough people and letting them read your words, you feel like a writer. Feeling like a writer changes your internal beliefs because you’ve entirely stepped into the identity of WRITER. And because writers write consistently, your actions change to align with this new identity.

Asking someone to beta read shows you: You can be brave. You can level up.

Writer level-ups often look like this:

I am a writer.I am a consistent writer.I am a published, consistent writer.I am a paid, published, consistent writer.I am a well-paid, published, consistent writer.Now that you know where this one tiny act of courage can take you, let me show you how to make this jump, and I’ll even show you where to find a few beta readers along the way.

How to level up and own your writer identityReframe your feels-so-scary-it’s-time-for-a-beta-reader realization to a phenomenal opportunity. This is the opportunity to baby-step deeper into your writing career by admitting, out loud, to another human that “I am a writer.”Acknowledge you don’t really believe you are writer—yet. Even though your actions confirm you write, and you have the proof of a finished written thing, and think about writing constantly, you still don’t believe you are a writer. It’s totally okay, none of us do at this point.Accept that saying “I am a writer. Would you like to read my book and offer your opinions on it?” is going to feel uncomfortable. Which is totally fine because feelings try to keep you safe by keeping you in your comfort zone, and you are actively expanding your comfort zone, which is uncomfortable.Practice the first half of the ask. Say “I am a writer” out loud while looking at yourself in the mirror. Say it in the car at red lights. Write it over and over, Simpsons-on-the-chalkboard style. Rehearsing ad nauseam gives you a better chance the words will pop out of your mouth before you have a chance to feel or think.Tell a stranger. Someone you’re never going to see again. Type it in the comments of a post on the internet somewhere. Tell your Uber driver. Mention it to a server at a restaurant you never plan to eat at again.Tell your acquaintances. The people who know you tangentially but aren’t involved in every detail of your life. People you haven’t spent one-on-one time with. The people at your gym. The knitting forum. The barista at your favorite coffee shop.The acquaintance step is where you’re going to find your beta readers. When people learn you are a writer, they get excited. They think our job is super cool—because it is. When these acquaintances see you living your dream, it makes them think maybe they can live their dreams too. This is why they will ask you about your writing every time you see them. If the acquaintance turns out to be an avid reader, or even better yet, a reader of your genre, they are the ideal person to ask “Would you like to read my book and offer your opinion on it?”

Acquaintances offer the most objective opinion because they don’t know your intimate life story. They won’t assume you’re writing about your third-grade boyfriend or craptastic day job, because they don’t know about either of them. They are also super flattered to be in on the early-stages-behind-the-scenes of a book, which means they eagerly read and get you feedback promptly. These early readers turn into fans and are the foundation of your platform. They have excitement about your success, because they contributed to it by beta reading, which seals in your new writer identity.

You may have noticed friends and family are not on the baby-step list. This is because family and friends love us and want to keep us safe. The people who know us best are often those overly cautious, well meaning, here’s-all-the-reasons-this-is-not-going-to-work types. Telling them before you own your writer identity is a common way we subconsciously self-sabotage and stall our writing evolution.

Most of us don’t have the emotional muscle to carry around the fears and concerns of family/friends until we’re at the I am a published, consistent writer stage of things. If someone close to you is a permanent Eeyore, I implore you DO NOT TELL THEM. You do not have room for dream assassins whispering in your ear. Find the dream enablers, share with them, and the well-intentioned-dream-assassins can be spectacularly surprised when you have something in print to show them.

Owning your identity as a writer is a key step toward becoming a well-paid, published, consistent writer. Writing something was the first step, now take the next one and tell someone, “I am a writer.”

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Thursday, April 27, for the online class Finding & Working with Beta Readers.

April 19, 2023

How to Make Productive Use of ChatGPT: Q&A with Elisa Lorello

Author Elisa Lorello’s exploratory dive into ChatGPT led her to discover its usefulness to fiction and nonfiction writers, and she shares them all in her new book The AI Author Assistant: How to Use Chat GPT to Optimize Your Writing Progress and Income While Retaining Your Human Touch.

In this Q&A, she reveals some of the terrible titles it spat out (while keeping the really good ones to herself), acknowledges the complicated moral question of writers allowing ChatGPT to do their writing for them, and lists the many ways AI has been helpful to her both creatively and practically.

Elisa Lorello (@elisalorello) is the bestselling author of twelve novels and one memoir. The youngest of seven, she grew up on Long Island and graduated with two degrees from the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth. Since 2010 she’s sold over a half-million units worldwide and has been featured in the Charlotte Observer, Woman’s World magazine, Rachel Ray Every Day magazine, The Montana Quarterly magazine, and Writer’s Digest Online. She’s also been a guest on multiple podcasts and a panelist at BookExpo.

Elisa is a lifelong Duran Duran fan and a proud Gen-Xer, can sing two-part harmony, and devours chocolate chip cookies (not always at the same time). She currently lives in Montana with her husband (bestselling author Craig Lancaster) and their two pets.

KRISTEN TSETSI: Multiple articles about ChatGPT and writing will take one side or the other: they’ll explore writers’ fear of ChatGPT, or they’ll assure writers they shouldn’t fear it at all. As a writer, before ever using it or reading much about it—just knowing that this AI could churn out written material—what were your initial, knee-jerk feelings about it?

ELISA LORELLO: My knee-jerk reaction was the same as many writers: This is not good.

Everywhere I turned, there was an article or a lecture depicting the dangers and negative aspects of AI—people submitting queries to agents that were written by ChatGPT, ChatGPT-generated Buzzfeed articles, etc. I even came across an online course called “Write a Book in 24 Hours with ChatGPT”—I was so curious and skeptical that I purchased it. (It wasn’t a big investment; that said, I do not recommend others buy it. Let’s just say I took one for the team.)

But as a result of that course and experimenting/playing with ChatGPT, I found ways in which ChatGPT could actually be helpful to myself and other writers, and that’s ultimately what inspired me to write The AI Author Assistant. I see it as a little guidebook, a demonstration of as well as a conversation with ChatGPT. I wanted to counter the doom and gloom with an alternate perspective.

In an article in The Independent about the hundreds of AI books that have already appeared on Amazon, Authors Guild executive director Mary Rasenberger says, “This is something we really need to be worried about, these books will flood the market and a lot of authors are going to be out of work.” She then expresses a concern that AI could take the place of existing human ghostwriters, turning “book writing from a craft into a commodity.”

I would argue that book writing is already a commodity more than a craft, in many cases (I ashamedly used to do some commodity co-ghostwriting/editing), but I’m curious to know your thoughts about this: what’s the worst that could happen, do you think?

I think people were sounding the same kinds of alarms about ebooks and the Kindle in 2009–2010. They said ebooks (especially self-published ebooks) were going to kill the printed word and put traditional authors, agents, editors, and bookstores out of business. Digital publishing-on-demand was disruptive, and the industry needed to adjust and adapt.

But here’s the thing: it did. The industry adjusted and adapted, and digital publishing-on-demand is as viable an option as traditional publishing. Moreover, the professional standards for self-publishing significantly increased as a result.

Yes, AI will cause disruption. Yes, there will be a lot of AI-generated books (like, a lot) and content, and yes, there will be a lot of crap to sort through. But I think a savvy reader will know the difference between AI and human, organic writing, and I think publishing will adjust and adapt. Some people will game the system and get rich at the outset, and then the system will catch up and weed them out. Standards will evolve. Because if there’s anything we learned from the rise of ebooks and self-publishing, it’s that fighting or resisting is futile. Downplay the bad and work with the good.

I also think a fraction of the Literary community (capital letter intended) will always rail against genre fiction and mediums like Patreon or Substack or Buzzfeed as “commodity” writing. And hey—I want to make a sustainable living doing this thing that I love. I also want to write the best books and blog posts that I can. Those two things can co-exist.

What led you to see that ChatGPT could be not the nemesis of the writing and publishing community, but an aid to enhance a writer’s existing creativity?

When I was suddenly so creatively fertile! I confess: At first, I was totally looking for “the secret formula” to a bestselling genre novel, and I was curious to see if AI could actually write one. Yet of all the possibilities ChatGPT generated, only one piqued my curiosity. Also, it revealed no secret, just what’s already been said and done. But after a few days of exploration and playing around with titles, tropes, and storylines, every morning in the shower a completely new idea would come to me—and they were good! Not generic, and not necessarily from the AI-generated lists. Moreover, I wanted to experience the pleasure of writing these books myself.

Meanwhile, administrative things I began using it for—outlines and timetables and daily schedules, mainly—were freeing me creatively and improving my productivity and time management. This past month, I started writing two novels with overlapping storylines, kind of like companion novels. ChatGPT generated outlines for each, and I’ve been writing both manuscripts as if they were one novel with alternating POVs. In three weeks, I drafted 35,000 words (combined). At this rate, I predict I’ll complete the first draft of both by the end of June.

Moreover, when I finish writing these two books, I know what the next two will be. It’s like I suddenly gained an edge in productivity, organization, and creativity.

If ChatGPT could do that for a writer like me, then perhaps it wasn’t all bad.

What was your first exploration of ChatGPT like, user-wise? What were your first experiments, and what were your early thoughts about its capabilities or limitations, if you saw any, in terms of how it responded during those first experiments?

At first, I put that course to the test and tried to compile content for a nonfiction book just to see if it actually could be done in the alleged 24 hours. It generated about 10,000–15,000 words of content—hardly enough for the kind of book I had in mind for the test case. Moreover, I noticed factual inaccuracies in some of that content. (ChatGPT sometimes doubles down when you challenge the inaccuracy; it’s a little creepy.) And most AI-generated writing isn’t very good from a craft standpoint.

Next, I did some creative exploration for fiction—titles, story ideas, and even scenes of description and dialogue. For example, I asked Chat GPT “What kind of character would appeal to a Generation X female reader?” Or “What are the most popular tropes for contemporary romance?” When I wrote The AI Author Assistant, I asked for title and subtitle recommendations. In the book, I showed the progress of how I ultimately came up with the title I did.

The most interesting and unexpected result was all that exploration and play sparked ideas of my own. So, for example, if I asked ChatGPT to give me 10 premises for an office romance, I would decide they were all too generic—and then the following morning in the shower a fresh idea for an office romance would come to me.

I also saw ChatGPT’s value in generating story outlines. This was one of the game-changers for me. Writing outlines before I start a novel has always sapped me creatively. By giving ChatGPT the premise at the onset, along with characters and any scenes I might already have in mind, ChatGPT then produced an outline within seconds. Now I had something to work with at the beginning of a manuscript, and I was creatively motivated rather than sapped. And even though the outline tends to be as generic as much of the content ChatGPT produces, it’s fluid and flexible, and place-holds plot points for me. I’m OK with that.

Ultimately, ChatGPT can function as a virtual assistant—you can use it to brainstorm ideas, write outlines, and even prioritize your day’s to-do list. It can also help you with basic research and will deliver it to you quicker than a Google search.

However, beware—as I mentioned earlier, the information isn’t always accurate. In The AI Author Assistant, I included an example of my asking ChatGPT to rank my books from most sales to least sales. It listed seven books, I think (I’ve written over a dozen). The first one was my least-selling, and of all the titles, only three were actually mine.

Additionally, if you ask it to actually write a scene or paragraph for you, be prepared to do a lot of editing and polishing because the prose is wordy, the dialogue is stilted, and the description is cliché and generic.

To offer my own example of ChatGPT doubling down on errors, my husband Ian asked ChatGPT, “Who is Kristen Tsetsi?” After listing some basic information available online, it said I was also the founder of National Freelancers Day. Ian then asked, so it might recognize its error, “Who is the founder of National Freelancers Day?” ChatGPT said, “After double-checking, I can confirm that Kristen Tsetsi is indeed the founder of National Freelancers Day.”

Back to your experiences with it. You write that ChatGPT can “streamline your writing process and progress by generating text quickly, reducing the time spent typing or brainstorming.”

What does that mean? I ask because it reads as if the AI is in fact doing a portion of the writing, and my reflex as a writer is to think that any writing not done by the writer is a form of cheating. (Or plagiarism? Is it plagiarism if the writer is a bot?)

I think ChatGPT wrote that line, actually. [winks] I asked ChatGPT to give me ideas for the ways in which writers can use ChatGPT ethically and responsibly and then applied the responses to The AI Author Assistant as a kind of dialogue.

I think your interpretation isn’t wrong—it could be used that way. And I share your concerns about plagiarism and/or cheating. I wrestled with those questions in the book. Is ChatGPT serving as a ghostwriter? If you cut and paste its content and pass it off as your own, is it plagiarism? Are you cheating your readers and yourself out of an authentic writing experience? I didn’t provide any specific answers because I don’t think they’re hardcore “yes” or “no.” My main goal was to bring the questions, concerns, and discourse front and center.

I use ChatGPT as a springboard. For example, I dislike writing book descriptions, and I always freeze up when it’s time to write one. I asked ChatGPT to write a book description for The AI Author Assistant. I hated what it came up with; however, it unblocked me and I wrote a description on my own. (I used only one line from the AI-generated one, and tweaked it a bit.) I did the same writing copy for Amazon ads. ChatGPT gave me some ideas to work with, and I then created copy in my own words.

In other words, ChatGPT is a buddy. For instance, instead of asking my husband (also a writer, and a busy one at that), “Can you help me brainstorm book titles?” or “Can you help me write this description?” or “Can you help me flesh out this scene?” ChatGPT can serve in that role.

And when it comes to prioritizing a to-do list, ChatGPT saves me a lot of time. I type in the tasks and it not only prioritizes them but also explains why it chose the order it did. Ditto for the outlines. ChatGPT can generate an outline in seconds; it takes me at least a couple of hours (and that’s just the first go-round), and after I do it, I never want to go near the story again.

What command did you use to ask it to write the book description? If I wanted ChatGPT to write some back-cover text (even if I intended to heavily edit it), I would have no idea what to tell it to make it do that. How much should be said about the book? Can you provide command samples for fiction and nonfiction?

For The AI Author Assistant, I gave ChatGPT the premise and objective of the book, as well as keywords that would likely come up in an Amazon search. So I think the command was something like: “Please [I’m very polite] write an Amazon product page description for The AI Author Assistant that highlights the objective of writers using ChatGPT in ethical and responsible ways, and include the following keywords…”

For fiction, I would probably do something similar. “[Insert title] is a contemporary romance in which four friends who haven’t seen each other in 20 years reunite at their hometown mall set for demolition in one week. Please write a description for the back of the book and the Amazon product page that uses these details and keywords…”

I would also give it a word count as a guideline.

ChatGPT tends to write kitschy copy like “Do you love a contemporary romance about second chances? [Title] has quirky characters, second chances, and hearty humor!” You may have to tell it to tamp down the selling while also appealing to the reader.

If someone is writing a novel—let’s say it’s literary—and they’re stuck on the “what next?” of a scene, can ChatGPT help?

I think it can if you use it as a freewriting technique. For example, if I don’t know what scene comes next, I could summarize (or perhaps even copy and paste) the previous scene and outright ask ChatGPT “What do you think should happen next?”

In the past, I’ve tried to unblock myself by typing, “What I’m trying to say is…” and then proceeding to try to work it out on the page, however messy it may be. You can say that to ChatGPT and it could potentially help you organize your thoughts or give you clarity or direction.

The key, I think, is to always make it your own. I’ve gleaned ideas from my husband or my former co-author or a developmental editor, for example. I’ve written dialogue after overhearing two people in a coffee shop or using a conversation I had verbatim. Writers also rely on beta readers for feedback. We’re pulling ideas and information from so many different contexts. It’s how we re-contextualize them that matters. We always need to be responsible and ethical.

In your book’s intro—and the part I’m referring to was written by ChatGPT, which is clear because of the different font you assigned it—there’s a claim that ChatGPT can “help you create marketing and promotional campaigns and materials which, in turn, can increase book sales.”

What can ChatGPT do for authors who are already doing all of the regular things they’ve been told to do to market their work?

I haven’t fully tested its usefulness, but ChatGPT purports to help you generate content for social media marketing, mostly. Also write press releases, book blurbs, ad copy, blog posts, etc.

I’ve been mostly experimenting, asking it to give me sample tweets to promote my most recent novel or brainstorming content ideas for Instagram and/or Facebook. I haven’t applied any of it yet (other than the aforementioned Amazon ad copy). I’ve also outright asked ChatGPT things like “What are some unique ideas for authors to market their books?” or “How can I make my monthly newsletter content engaging besides the usual suggestions of sharing excerpts of my WIP or photos of my workspace?”

Other than ideas for swag, I didn’t see any suggestions that made me go, “Now that is something different.”

I asked for ideas for a Substack series the other day; I might consider a couple of those.

Honestly, most of what ChatGPT suggests has been said and done before. But something about it sparks my creativity and originality. I reject a lot of what ChatGPT suggests and find better ways to write or think about an idea or solve a problem. I like that kind of mental exercise. And if it’s suggesting things I’m already doing, then maybe I’m on the right track and I don’t need to change what I’m doing but rather how I’m doing it.

Many writers get stumped on book titles and would probably love any kind of help they can get. But were any of the title offerings ChatGPT gave you absolutely terrible?

Oh, definitely a lot of terrible titles! But it’s like sifting through multiple pans of dirt for one gold nugget. The fiction titles are especially bad, although I confess there was one that I loved and am going to use in the future (I’m not telling you what it is!).

The advantage is that these lists of titles can be generated in seconds. That’s the “streamlining” of progress and process. I don’t need to type or brainstorm the lists myself. But if I sift through two or three sets of AI-generated lists, I’m bound to spot a nugget I can work with.

For example, the other day I got an idea for a “Freaky Friday” time-travel novella. ChatGPT generated a decent outline, but here are the titles it suggested:

“Mom Swap”“Back to the Past”“Freaky Family”“The Mother-Daughter Time Warp”“A Switch in Time”“My Mother’s Shoes”“Reversing Roles”“The Time-Travel Experiment”“Two Generations Apart”“A Tale of Two Ages”I mean, those are cringe-worthy. I would either request an additional ten after I’ve developed the story or take another long shower and wait for a better title to come to me.

What key cautions would you give writers about using ChatGPT?

I’ve mentioned a couple. For one, the information it feeds you isn’t always accurate. In fact, ChatGPT sent me on a wild goose chase to press releases and webpages that downright didn’t exist. You can’t take the information it provides you at face value.

But if you want to know something like the differences between Millennials and Gen-Z or the characteristics of a particular genre, then it’s a good, quick resource. The other day, I asked ChatGPT how one might go about opening a particular kind of business in a particular location for a potential plot point. It gave me enough background that if the character was going to pursue it, then I could write it in a way that was plausible.

The other caveat is the plagiarism issue we discussed earlier. Where’s the line, and how blurry is it? Is it OK for me to post ChatGPT-generated tweets, for example? Would anyone notice or care? (Maybe I should try it as an experiment!) Is it OK for me to use AI-generated ideas and titles for a blog series, but write my own content? Is it OK for ChatGPT to ghostwrite the content for a site like Buzzfeed, for example, while I collect the paycheck and the credit?

I posit that while we navigate through this technology and its applications, at the end of the day you need to be your own moral compass. And if your compass differs significantly from the industry’s, then you need to take the consequences if they reject it.

Has using AI taught you, or encouraged you to see in a new way, anything about your own writing?

It’s fueled my love for writing and being a writer, which is really saying something given how much I already loved both. I see what AI generates and it makes me want to write better, more creatively, and more productively. It makes me want to be more professional and organized. Ultimately, that’s the feeling I wanted readers to leave The AI Author Assistant with.

Overall, I encourage writers to play with ChatGPT and approach it as such. Have fun with it. Be curious. Once you know what it can and can’t do for you, I think you’ll have a better sense of how to use it in practical and responsible ways.

April 18, 2023

Create Effective Dialogue by Asking the Right Questions

Photo by Korney Violin on Unsplash

Photo by Korney Violin on UnsplashToday’s post is by editor Tiffany Yates Martin (@FoxPrintEd). Join us on Wednesday, May 3, for the online class The Power of Dialogue in Fiction.

Given most of us speak an average of 16,000 words a day, it seems as if writing dialogue should be effortless and natural.

But dialogue in story isn’t like dialogue in real life, which can meander or be riddled with empty filler, circumlocutions, and verbal tics. Story dialogue is more like concentrated orange juice: It gets rid of all the extraneous material and boils down communication to its essence.

To create effective and efficient dialogue that serves the story, you’ll need to ask yourself a few basic journalistic questions: the why, when, what, how, and how much of what your characters say.

WHY are your characters speaking?Dialogue adds wonderful immediacy to a story, but if it’s not used purposefully it can feel superfluous. It’s not an exaggeration to say that every single word your characters speak should be deliberately chosen to serve the story in some purposeful way.

Does the dialogue advance the plot or story? Are the characters—or you as the author—trying to communicate a specific idea or information? Or perhaps to conceal it—to misdirect, obfuscate, or distract?

Does the dialogue offer essential context for the characters or story, or reveal a key plot point, or further the character arc? Are the characters speaking to fill silence? Out of nerves? Out of a desperate desire to connect? To mask what they are feeling? To alleviate discomfort—their own or someone else’s? To please someone else or curry favor? Out of habit? For the sake of politeness?

Good dialogue often multitasks, serving more than one of these purposes to create layers of meaning in story.

WHEN do they speak?When your character speaks and doesn’t speak is an effective way to convey personality and relationships, further character development, advance plot, raise stakes, manage pace, and create suspense and tension.

What does the long silence after your character is told someone loves them reveal about their situation or relationship? What do readers know about the person who whispers constant commentary to their companion during a solemn occasion like a wedding or funeral or church service? Or the one who cracks a joke at just the right moment, or at the most inappropriate time?

How does it further the story and raise stakes and suspense when a character being interrogated refuses to speak—or inadvertently blurts an incriminating piece of information just when it seemed they were in the clear? What does it convey or mean for the story if a character witnesses a wrong and fails to speak up—or does speak, risking the wrath of the wrongdoer?

What your character doesn’t say is often as important and revealing as what they do—and when they choose to speak and choose to be silent can paint a vivid picture of who they are, what they want and why.

WHAT do they say?In life we often speak without thinking, and your characters might also, but as the author you should choose each word with deliberate purpose. How does it move them closer to their goals—or throw up an obstacle? How does it show readers who they are or what they’re feeling or thinking?

What to say will be a function of why your character is saying it—and why you as the author are having them say it. If the scene’s narrative purpose is to advance the story while showing two characters’ relationship, for instance, then your dialogue will focus on those areas, as Jonathan Tropper does in this brief opening excerpt from This Is Where I Leave You:

“Dad’s dead,” Wendy says offhandedly, like it’s happened before, like it happens every day. It can be grating, this act of hers, to be utterly unfazed at all times, even in the face of tragedy.

“He died two hours ago.”

“How’s Mom doing?”

“She’s Mom, you know? She wanted to know how much to tip the coroner.”

We get a lot of info in this excerpt just from the dialogue: that these two are siblings; that their father has just died; that the narrator’s first reaction is to worry about his mom, which indicates something of their relationship; a little bit about what their mother is like from Wendy’s comment about tipping the coroner—which may or may not be a joke, given what the narrative portion tells us is characteristic of her.

Subtext in the dialogue tells us even more: This is how the conversation starts, so we also may infer that Wendy is direct and doesn’t candy-coat anything, and that these two are in touch frequently enough and/or have a close enough relationship that there is no need for introductory pleasantries at the beginning of a call, even one like this. The narrator also seems to react rather calmly to what could be shattering news: That might indicate that Dad’s death is not entirely unexpected, or that the protagonist isn’t close to his father, or that he is a level, nonreactive person…or an unemotional one…or a tightly controlled one. We don’t know yet—this is just one piece of the puzzle that begins to come together as the scene—and the dialogue—progresses.

But the characters’ words aren’t casually chosen. Tropper is using dialogue to introduce the inciting event, several of the main characters (the narrator, Wendy, Mom, and to a degree Dad), and a bit of context on their relationship and history—plus set up the entire story premise. That’s a lot of multitasking for four lines of dialogue.

HOW do they say it?Like everything related to character, the way a person speaks is an amalgam of countless factors in their upbringing, background, situation in life, personality, experiences, etc.

Does their verbiage reflect the regionalisms of their hometown, for instance? What does their vocabulary and word choice say about their background or socioeconomic level or education or personality? How do their reference points or language reflect their background. For instance, does a painter use artistic metaphors and references, notice more aesthetic details, speak in more flowery or descriptive language?

Do they speak quickly or slowly, and why? Do they articulate or elide their words, and what is that a function of? Are they prone to verbosity or more taciturn? Do they choose their words carefully or vomit out everything that crosses their minds? How loudly do they speak and why? What tone do they use—sarcastic, apologetic, measured and calm, brash? What verbal tics do they have and what does that say about the character?

Do they speak straightforwardly and get right to the point, or circle around it until they finally say what they mean? Do they speak forcefully and confidently, haltingly, carefully and deliberately, completely off-the-cuff and stream-of-consciousness? And how does the way they speak change depending on their situation or whom they are talking to?

Considering all these factors not only helps you create believable but effective story dialogue; it’s also the key to making sure your characters don’t all sound alike.

HOW MUCH do your characters speak?Balancing dialogue with narrative is part of the skill of using it effectively, but there are no hard and fast rules. It’s different for every author, every character, and every story.

Dialogue is a great way to dramatize character interactions and bring the story directly to life in front of our eyes, but too much of it can start to feel overly talky, or as if we are reading a screenplay. It can also feel distancing to readers—much of human communication happens below the surface of the words, in story as in real life, and relying only on dialogue leaves readers blind to the richness of the rest of the scene and character dynamics.

But too much narrative without dialogue can also make a story feel distant. Describing everything keeps readers one step removed from the action, as if we’re hearing about it secondhand rather than living it along with the characters directly, and can bog a story down in verbiage and stall momentum.

A good rule of thumb is to think about the purpose of a scene. For instance:

Scenes meant to reveal or develop character or relationships may come to life more vividly in dialogue rather than just narrative description. Introspective “processing” scenes may benefit from more narrative exploration of the characters’ inner lives, context, or situation.Fast-paced, active scenes may move at a stronger clip if they incorporate lean, snappy dialogue amid the action (and thus create more white space on the page); slower, more reflective scenes might be better suited to narrative description.Lighter or humorous scenes generally benefit from more dialogue; serious or dark scenes might be better conveyed through more narrative.Where you do use dialogue, asking “how much” is also a good way to avoid the risk of soliloquies. Character dialogue that goes on too long can feel preachy, info-dumpy, or just plain dull, risking reader interest. (Picture the blowhard at the party who holds court in an endless monologue, while his audience desperately looks for ways of escape.)

Strong dialogue brings your story and characters to life and draws readers intimately, immediately into the scene. Asking yourself the these questions whenever your characters speak will help you make the most of every word of this powerful element of story.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Wednesday, May 3, for the online class The Power of Dialogue in Fiction.

April 13, 2023

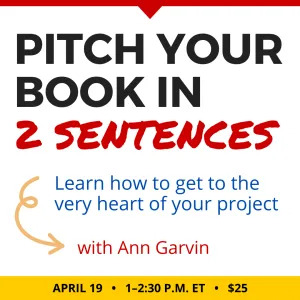

Describe Your Book in Two Sentences: Q&A with Ann Garvin

Today’s post is by author Laura Bird (@laura_at_the_library). Join interviewee Ann Garvin on Wednesday, April 19 for the online class Pitch Your Book in 2 Sentences.

Writing a book is one thing; marketing it is quite another.

Before my debut middle grade novel was published, people would ask me, “What’s your story about?”

I’d bumble through a response as their eyes glazed over, shinier than two Krispy Kremes. I desperately wanted to impart the heart and soul of my book to them, but all I could do was nervously stutter.

I quickly discerned that I needed to hone my marketing skills, or I’d never sell a single copy of my novel. So I called my good friend Ann Garvin, who taught me how to convey the essence of my story in a few punchy sentences.

When we do this, people actually listen, and then they go out and buy our books.

It’s the simplest thing, but also the hardest. Let’s dig in.

Laura Bird: Why is it so hard to describe a book in a couple sentences?

Ann Garvin: A writer who has finished a novel has taken a glimmer of an idea and expanded it into an entire book-length project. They’ve created multiple characters, plot lines, and scenes filled with emotion critical to the finished book. A pitch asks the writer to keep all these things in mind and craft one or two juicy sentences that entice a reader to ask for more. To do this, they must leave the role of creative writer, memoirist, or nonfiction expert and dip their toe into another profession entirely. They have to learn how to market their work. And while a good marketer tells a story, she doesn’t tell the whole story, and that’s where it can get complicated for someone who just wrote a book.

What’s the ideal length of a good pitch?

Two sentences, maybe three, if they are short. Literary agents, editors, and even loved ones are busy, and we all have short attention spans. Writers need to be able to talk about the core of their story, using the fewest, most impactful words possible—or they risk losing their audience’s valuable attention. We’re trying to hook them into asking them for more, rather than explaining everything they might miss if they don’t read our book. One is a flirtation, the other is a monologue, and I don’t know any dating sites that use the monologue system to find love.

What are the components of a good pitch?

An effective pitch will address things like: Who are the main characters? What are they doing and why? Why should I care about this story, and what’s at stake?

I have a pared-down formula that might be helpful. It looks something like this:

[protagonist] + [inciting incident] + [protagonist’s goal] + central conflict

If you start with this formula, you can work your way into a second one that fleshes it out a bit more:

When [inciting incident] happens to [protagonist], they must overcome [central conflict] to get [what protagonist wants]

But this seems to leave out almost everything!

It feels like that, yes, but a pitch gets down to the very core of the story. It’s not a plot summary, a timeline, or an inventory. A good pitch hints at what the character in your project might need to overcome to get what they want. It allows the reader to imagine what it might take to survive and grow from a situation; this imagination is the most enticing thing. The good news is the reader brings their imagination to the meeting; you just need to spark their vision.

What mistakes do writers often make when pitching?

They try and give a complete summary of their book and end up in the weeds, or they write a review of the themes found in the book, leaving out the essence of what characters are doing on the page in order to get what they want.

What is the hardest pitch you’ve ever written?

My first book is about Maggie Finley. Devastated by the loss of a pregnancy, she has returned to her hometown newly pregnant and discovers that a sex offender lives on her street. Maggie rushes from the sublime to the ridiculous to keep her family safe, only to discover her haven is in the unlikeliest of places.

The most challenging thing about this pitch wasn’t that the story was potentially grim; rather, it was how to communicate that this story had quite a lot of humor. So you can imagine it was a very challenging pitch to write! Although I sold it, I’m still not sure I had it right.

How did you figure out the art of good pitch writing?

Each time I write a pitch, I have to work through the process—repeatedly. But I’ve been a professor since 1995, and whenever I’m faced with figuring out a new skill, I teach it. I break it down as if I’m presenting it to strangers, and in the process, I learn it myself. I’ve also spent the last decade teaching and working at pitch conferences and universities to hone my skills.

In the end, though, the writer knows her book best and has the most skin in the game. She knows what her book is about—she just needs to put it in the right words.

You’re giving a class and running a pitch contest. Why?

There are so many talented writers with compelling manuscripts who need help with the next step toward publishing. When I was a new writer, I felt like there was a fire wall between me and agents and editors. It was frustrating, and I didn’t know how to get past it. Maybe it’s the nurse in me, or the educator, but I want to open the gates for other writers to bring their dreams to reality.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join Ann Garvin on Wednesday, April 19 for the online class Pitch Your Book in 2 Sentences.

April 12, 2023

Ask the Editor: How Do You Move Beyond the Three-Act Structure?

Photo by Andrew Neel

Photo by Andrew NeelAsk the Editor is a column for your questions about the editing process and editors themselves. It also features first-page critiques. Want to be considered? Submit your question or submit your pages.

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Author Accelerator. Is book coaching your dream job? Take the One-Page Book Coaching Business Plan Challenge to find out what kinds of writers you would coach, how (exactly!) you will help them, and how much money you can make doing it. Sign up for our $99 mini-course that launches in May.

Question

QuestionHow do you write organically and originally while sticking to Freytag’s Pyramid and the three-act structure? I’ve read Meander, Spiral, Explode by Jane Alison and Craft in the Real World by Matthew Salesses, both of which advocate moving beyond Freytag’s Pyramid and the three-act structure, but how do you do that and keep a genre story moving? (I write science fiction/fantasy for adults.)

—Trying to Escape the 3-Act Pyramid

AnswerHello, Trying to Escape! I’m very glad for your question—the topic hits on an approach to writing that I frequently proselytize to authors.

The answer lies in your question: You say you want to write “organically and originally.” I love that—it’s the very seed of strong, singular storytelling and often the antithesis of “sticking to” a prescribed method or system, as you suggest in your question.

Trying to impose a particular mold onto your story and make it fit is writing from the outside in, rather than letting the story grow from the inside out, which I consider the more organic approach you describe.

It sounds like you may be try-curious, wanting to bust out of the strictures of a rigid approach and find your own—but perhaps a little leery that doing so will dissolve your story’s structure and cohesion?

Let me first offer a way of rethinking approach and structure for any story, not just genre fiction, and then suggest a method for organically finding what your story wants to be and how to most effectively unspool it.

Build your writing buffetI am a big fan of craft books. Huge. I read them the same way I devour self-help, psychology, business, and (I’ll be honest) décor and style books: like popcorn—I can’t get enough.

But if I tried to slavishly dedicate myself to implementing every single system, I’d freeze up. It’s too much, and not everything I read is going to work for or resonate with me, or apply to every personal situation I face. (I’m looking at you, Marie Kondo. You take your folded underwear and get it out of my life.)

I think of all this information as a delightful smorgasbord from which to create my ideal plate. Each of them teaches me about topics I’m interested in and expands the knowledge I can draw upon in creating my preferred menu.

But to play out the metaphor way too far, I may not want the same plate for every meal. Maybe next time I decide to try some foie gras (why not? never had it) but then discreetly spit it into my napkin because it’s gross. Maybe I get a second heaping helping of something I loved—but it’s too much or I get tired of it.

We’ll stop with the gluttonous strained metaphor now, but you see the point? Think of all these craft approaches—many of which offer valuable, actionable, useful suggestions—as items in that cornucopia you can choose from at different times, with different stories. Take elements from various approaches, mix and match—find the right tool at the right time for the right job.

But how does that approach lend itself to creating a solid, cohesive story, rather than risk its riding off the rails?

Define Key Story ElementsWhat most craft techniques have in common is that they build from the basic form of story:

A character is invested in something or wants something; they face what stands in the way of their getting it, with varying results; and their failure or success in achieving it effects some meaningful change (in the character, their world, or both).

There’s lots of nuance and variation on that basic format, but this is what most readers anticipate from story.

Keeping those guiding principles in mind, you don’t have to unspool that story strictly to the three-act structure—or any prescribed system—as long as you hit certain key notes:

If you establish your story’s driving forces—what your characters want and why; what they stand to gain or lose from attaining or failing to attain it; and what action they take or fail to take in achieving it—you have your basic building blocks.Understand that every story needs ups and downs to hold readers’ interest: movement toward attaining those goals, and setbacks away from them. Flat lines are narrative dead space. Create those levels throughout.While there may be many smaller ups and downs, identify the major successes and major setbacks the character experiences in the journey toward their goal—their key high and low points—and then plot a course that leads your character(s) to each. What actions (or failure to act) led to that major triumph or major challenge? What turning point shifts their course toward the next high or low?Move the story forwardYou ask how to make sure you keep the story moving—an excellent question, as forward momentum is essential for every engaging, compelling story. Keep in mind these guidelines for maintaining the propulsive elements of story:

Keep your character(s) urgently pursuing both their overall goal and immediate goals in service to it in every scene throughout the story. Learn more: The Secret to a Tight, Propulsive Plot: The Want, the Action, and the ShiftMake sure readers understand what your character stands to gain or lose at each step of the journey; keep stakes clear, high, and pressing throughout.Keep readers turning pages by raising questions and uncertainty throughout (suspense).Keep them engaged and uncomplacent by making sure every page carries elements of friction, opposition, conflict between your character and what they want both long-term and near-term (tension), whether great or small, internal or external, overt or subtle, direct or indirect.Let us see how your character(s) are affected, shaped, altered at each step along the path as a direct result of their actions and the consequences throughout (character arc).This breakdown sounds overly simplistic—and it is. But these essential elements can serve as building blocks for any story, with any structure, the way that you can use LEGOs to make a house or a plane or a nine-foot-long replica of the Texas Capitol Building.

Worry less about adhering to a particular system of story structure and more about developing the essential elements of story, and it will free you to grow it organically, as you describe—and more originally.

The beauty of writing is that you have godlike freedom to do it any way you want to—to let yourself experiment, explore, and keep developing, shaping, and honing it as you see what works, and what may not be as effective in engaging readers and taking them on the journey you envisioned. And then you can try something else until you find what does. That’s editing and revision, and it’s the most magical part of writing, in my view. (In fact, I based my book Intuitive Editing on this exact idea, of finding your story organically.)

You don’t have to rigidly follow other people’s particular maps. Use them as a guide if you like: Especially if you get stuck or your story is treading water, lost in a detour, or stuck in a dead end, they can be useful tools to get you back on track and moving again.

But find your own route to your destination. You may find yourself falling off the edge of the flat Earth, or you may enter unexplored territories where there be dragons—and bring back never-before-seen wonders.

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Author Accelerator. Is book coaching your dream job? Take the One-Page Book Coaching Business Plan Challenge to find out what kinds of writers you would coach, how (exactly!) you will help them, and how much money you can make doing it. Sign up for our $99 mini-course that launches in May.

April 11, 2023

Are You Giving Yourself Writing Credit?

Today’s post is by author, editor and coach Jessica Conoley (@jaconoley). Join us on April 27 for a class on working with beta readers.

You know when you’ve had a really good writing day and you feel all that positive energy as you wrap up your work session? When you get up from your writing time and you’re ready to slay the rest of the day? That I’ve totally got this feeling is achievement momentum.

Achievement momentum is generative energy that propels you forward. It helps tasks feel easier and goals feel more attainable. You build this positive energy every time you achieve a goal you set for yourself. It is built upon keeping promises to yourself.

You can jump start achievement momentum with one simple tweak: Give yourself credit.

You already plow through countless tasks to move your writing dreams forward: reading this blog post, brainstorming about your next project, talking through a mental block with your coach. But if you’re like 99.9% of us, that stuff doesn’t count because it isn’t immediately evident in your end product. The person who will eventually consume your work won’t see all that behind-the-scenes effort, therefore it doesn’t matter.

But is it really true that all the extraneous writing support stuff doesn’t matter? Could you create that masterpiece of an end product without all of the tangential learning?

No. You could not. You need the sum of all those experiences to create the end product that will change other people’s lives.

It’s time to stop discounting your work. It is time to acknowledge you are doing more to bring your dreams into reality than you think. It is time to tap into your achievement momentum. Here’s how to do it.

Create a “scream in your face” daily visual reminder.One of the hard parts of working on a complex long-term project, like writing a book, is the day-to-day progress isn’t readily visible. Yes, you may have worked three hours, but hitting save on your document doesn’t scream Look how far I’ve come!

Build achievement momentum by having some fun. Let yourself play and dream up ways to reward yourself with reminders of your daily progress. A few ideas:

A sticker chart. Grab a good old-fashioned calendar and throw a sticker up every day you work on your project. This means you get to go sticker shopping, and there are SOOOO many kinds of stickers to please your eyeballs. I assure you stickers are just as rewarding as they were in kindergarten, which is why this is my personal favorite.A count-down chain. In the U.S., kids make paper chains leading up to Christmas and cut off one link of the chain every day—and as the chain shortens so does the excitement that Santa will soon arrive. Is your goal to create every day? Get to linking: three-hundred-sixty-five is the length of your chain. How many chapters do you have to revise? Places you need to research? Interviews you need to complete? That’s your number of starting links.The reverse growth chart. This one is good because it helps you visualize the absence of something, which is very hard to do. Let’s say you have 100 copies of your book you want to sell. If you stacked those books up into a massive tower, how high would it be? Lay out paper to that length, make tick marks of the appropriate size, and tack the paper onto the wall. Every time you sell a book, color in the tick mark. Watch the chart fill in until you hit your goal of zero. You could even put those books into that giant stack in front of the chart.Decide what counts.There are big finish moments that we accept as earning ourselves credit. Most of the time this is something momentous like typing THE END on a manuscript.

But the key to jumpstarting achievement momentum is giving yourself credit for the baby steps that add up to the big finish.

This is where most of us complicate things. We immediately assign qualifications for something to count. Like I have to do all the things on my list to earn a sticker. Only certain types of writing count. Only increased word count days count. Only writing on Tuesdays under a full moon with a fountain pen on handmade parchment counts.

Qualifications set us up for failure. They condition us to believe writing has to be hard. They limit our forward progress so we can stay in our comfort zone—writing, but never showing our work to anyone.

To get clear on what counts, put yourself into brainstorming mode. The #1 rule of brainstorming mode: no value judgments allowed. Here’s an exercise.

Grab a timer and set it for 43 seconds. (Why 43? Because it’s a real nice-looking number that doesn’t easily divide and throws our brains a little off kilter. Brainstorming loves off kilter.)Grab a pen and paper, your notes app on your phone, or open a new document on your computer.Wiggle your toes. Feel every single one of them. Feel how the socks wrap around your foot. Think about all the sensations in your toes and feet until it is borderline comical. When you are more connected to your feet than you ever have been before, brainstorming has been activated.Hit start on the timer.List any and everything you can that gets you closer to your end goal.Choose at least five things from your list that you will give yourself visible credit for when you complete them.Give yourself credit. (Stick the sticker, cut the link, color in the tick mark.)Do you have at least five things you will give yourself credit for? Have you made the tasks realistic and broad enough you are setting yourself up for success? If you did at least one of those things every day for a month, would you be closer to the vision of your ideal writing life?

If you answered yes to all of the above, you’ve found your keys to unlocking personal achievement momentum.

If you really want to make things fun, share your “scream in your face” daily visual reminder with your fans. Here’s a secret: People love to cheer you on. When you let them see that you are making progress, they feel like they are coming on this creative adventure with you. And I promise you, at least one person will see you doing the work and it will inspire them to work toward their dream. By giving yourself credit and sharing it with the world, you are giving someone else permission to be brave and live their dream.

Now go, make your “scream in your face” tracker, and if you want to share it with us here, we’d love to see it. Just leave it in the comments below.

April 7, 2023

How to Find Comp Titles Using ChatGPT

Photo by Matheus Bertelli

Photo by Matheus BertelliToday’s guest post is by John Matthew Fox (@bookfox), author of The Linchpin Writer.

Finding comp titles used to be a gigantic chore.

You’d comb through hundreds of books, trying to find just the right two to suggest in your query letter. You didn’t want books too similar, and yet obviously they couldn’t be very different either.

And most of the time, you had doubts whether you’d picked the right two.

Well, ChatGPT makes finding comp titles easier than ever.

Here are five steps to finding your ideal comp titles for your query letter or book proposal. At the end I’ll put all five steps together in a prompt that you can use for your book.

1. Tell ChatGPT to pick titles published in the last three years.Agents aren’t looking for books published a decade ago. They certainly aren’t looking for books published twenty or thirty years ago.

That’s because when they pitch publishers, they have to include recent titles. That shows publishers there is current appetite for this type of book.

2. Tell ChatGPT to choose mid-level books (not super-famous books).Comp titles should never be Harry Potter and Jack Reacher—I don’t care how similar your book is to them. Sure, it’s one step above “I don’t have any comp titles” but not much better.

By picking super famous books, you are communicating to the agent:

You’re lazyYou don’t read muchYou have an inflated sense of your book’s potentialNow, I know you don’t have access to sales numbers to help you choose the best possible “mid-level” book, and you can’t even ask ChatGPT for Goodreads review numbers or Amazon review numbers. But you can say: don’t include any books that have appeared on bestseller lists.

3. Tell ChatGPT to pick books in your genre.Describe your genre to ChatGPT. Be as specific as possible. For instance, don’t just say fantasy. Say high fantasy, grimdark fantasy, or paranormal romance fantasy.

Don’t just say mystery. Say cozy mystery, gumshoe mysteries, or capers.

If you don’t have a specific, nameable genre, then try some of these words:

upmarket (between commercial and literary)literaryrealistcommercialexperimentalbook club bookyoung adultnew adultcoming of ageThe more specific you get, the more likely ChatGPT will suggest books that are perfect for your comp titles.

You also need to use negative commands, for example (if appropriate):

Do not include nonfiction books.Do not include poetry.Do not include memoirs.4. Choose the number of books.I would recommend asking ChatGPT for either 10 or 20 books.

Anything more than that and you’ll have to do too much research to try to figure out the right titles. Anything less than that and you might not end up with two winners.

Remember, all you need is a couple comp titles. One isn’t enough, and as many as three might not be necessary, at least for fiction. (Nonfiction authors, you may need more for your proposal’s competitive title section.)

5. Specify a certain place or theme or topic.Ask ChatGPT for books set where your book is set (Montana? Thailand?).

Ask ChatGPT for books on similar themes (anxiety? immigration?).

Ask ChatGPT for books on certain topics (divorce, children with special needs).

The more specificity you can provide, the more it will be able to suggest comp titles that are right for your book.

Sample prompts for ChatGPTSuggest 10 comp titles published in the last three years for a literary novel set in New York that features drug use. Do not include any books that have appeared on bestseller lists. Do not include nonfiction books.Give me 10 comp titles for a historical romance novel set in England in the 1800s. Only include books published in the last three years. Do not include any books that have appeared on bestseller lists. Do not include nonfiction books.List 5 comp titles for an upmarket fantasy book about a home for children with magical powers. Only include books published in the last three years. Do not include any books that have appeared on bestseller lists. Do not include nonfiction books.Suggest 20 comp titles for nonfiction books about brain atrophy in the elderly. Do not include bestselling books. Do not include any novels. Do not include any books that have appeared on bestseller lists.After you get some resultsIt’s usually good to ask follow-up questions. So if you didn’t get what you were looking for, give ChatGPT additional questions that specify exactly what you need.

Of course you’ll need to do research on each of the suggested titles. Make sure they exist. (ChatGPT may hallucinate titles that don’t exist.) Do they really overlap with the themes in your book? Ensure they aren’t bestsellers.

In my experience, using prompts like this, ChatGPT is pretty close to the mark on the first round. But if you have a particularly challenging situation, you might need to re-prompt it for another round or two.

For old-fashioned methods of finding your comps, read this post.

April 6, 2023

How to Differentiate Between Desire and Desperation in Pursuit of Publication

Photo by Alexis Fauvet on Unsplash

Photo by Alexis Fauvet on UnsplashToday’s post is by writer and nonfiction coach Amy Goldmacher (@Solidgoldmacher).

Is the desire to get published damaging?

As writers, we want to share our messages and our stories with others. A way of achieving that goal is through publishing. However, an unintended consequence of our drive to get published may be that our deeper internal motivations get overridden by the pursuit of the goal.

The odds aren’t good when the goods are oddHere’s what I mean: I have been submitting a 10,000-word, 2nd-person POV flash memoir in the form of a glossary to competitions and small presses since May 2022. For context, this book is about a woman who becomes the age her father was when he died, and how she realizes the way she grew up doesn’t need to be the way she lives the rest of her life, written in alphabetical glossary entries. It is my story, but it’s also for those who, perhaps facing the downhill portion of the mortality rollercoaster, feel that some of what made us successful may no longer serve us.

Memoir is a crowded and competitive market, and my stylistic choices meant additional barriers to publication. I knew this as I wrote and revised and found the structure that served the story. But, as rejections stacked up, I started to feel more desperate. There are not limitless outlets accepting unconventional works like mine. I scoured the internet for places to submit, regardless of what they were offering, pursuing any opportunity to be picked. I started flinging submissions like spaghetti against a wall to see what would stick. As Meredith from Season 2, Episode 5 of Grey’s Anatomy begged her McDreamy, I too was desperate: pick me, choose me, love me. Does it not feel like the ultimate indication of approval to be selected above all others?

The wrong yes will break your heart worse than a rejectionAnother common waypoint writers experience on the path to publication is the near-miss, when a press says you almost made the final cut. But even more painful is an acceptance that doesn’t fit.