Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 50

April 5, 2023

4 Pillars of Book Marketing, or How to Sell More Books in Less Time

Photo by Ian Hutchinson on Unsplash

Photo by Ian Hutchinson on UnsplashToday’s post is by book advertising consultant Matt Holmes (@MatthewJHolmes1).

When I first started marketing my wife’s books, I thought we needed to be everywhere and do all the things in order to be successful:

Facebook adsAmazon adsBookBub adsYouTube adsPromo sitesFacebook groupsAll other social media platformsNewspapers and magazinesThe list goes on—and on. The truth of the matter though, is that you don’t need to do even half of what’s on that list.

The do all the things approach likely does more harm than good, especially in the beginning. Sure, further down the line, you can start adding to the list, but even then, don’t feel you need to.

My wife’s books currently earn a healthy six-figure income. And we use two traffic sources:

Facebook adsAmazon adsNow three years into the journey, we are starting to explore other traffic sources so as not to rely so heavily on Facebook and Amazon. But these two platforms alone, along with a small spend on BookBub and promotional sites for launches and promotions, drive the results for us.

Royalties for my wife’s books from November 2022

Royalties for my wife’s books from November 2022In this article, I’d like to share with you how I spend 30–60 minutes each day marketing my wife’s books, and how you can do the same.

Marketing for 30–60 minutes per day came about as more of a necessity than anything else; with three children under the age of three in the house, time isn’t something either my wife or I have much of! If you currently have young children or have done so in the past, you’ll know where I’m coming from. So I had to make sure every minute I spent was on the right marketing for us.

Avoiding the shiny objects discussed in Facebook groups, i.e. the latest fads, I identified what was driving results for us and doubled down on them, eliminating everything else.

This is when I (accidentally) identified what I now call the four pillars of book marketing. And, after speaking with many authors over the past couple of years, I believe these four pillars are critical for every author.

Without them, you’ll be spinning your wheels not knowing what to work on and when, or worse, spending your resources on things that don’t move the needle.

So, here’s what you’re going to learn:

What the four pillars of book marketing areWhy 30–60 minutes per day spent marketing is all you needHow and why to craft a strategy for your author businessIdentifying your lever-moving activitiesHow to plan out your days, weeks, and months for maximum productivity and resultsThe 4 Pillars of Book MarketingSome activities in your author business may not be exciting but are essential to keep your business going, such as accounting, taxes, replying to emails, and other admin/auxiliary tasks.

When it comes to marketing and driving book sales, there are really only four pillars that truly matter:

Book product pageTrafficAudience buildingProfitBook product pageSomething I say to authors a lot is: Your book sells your book.

No amount of marketing or advertising is going to sell a poor-quality book.

You could be the best marketer in the world, but if your book itself isn’t up to scratch, isn’t up to the standard it needs to be in today’s world of publishing, it’s not going to sell.

You may be lucky and get a few sales, maybe even a few hundred sales right off the bat. But when the reviews and ratings start coming in, the performance of your marketing is going to decline over time.

This is why, yes, you need to write a stellar book. But you also need to present your book in the best possible light. And you achieve that by creating a superb book product page.

After all, sales don’t happen in your Facebook ads, BookBub ads, Amazon ads, etc. They happen on your book product page. That’s where readers make the decision to buy or not to buy your book.

The key assets of your book product page you need to focus on are:

Book coverBook descriptionPricingReviews and ratingsLook InsideA+ Content, specific to Amazon (optional)With a compelling and engaging book product page in place, all of your marketing and advertising will perform that much better because your conversions (i.e., sales directly from your ads) will be higher.

And the more sales your ads generate, the more organic sales (sales that come as a result of your Amazon rank) you’ll enjoy.

TrafficWithout eyeballs on your books, you will not sell books. Period. Thus, to make sales every day, you need readers to see your books every day. And that is achieved by driving traffic to your book product page. Can you see how these four pillars are starting to connect?

Now, there are many forms of traffic generation, including, but by no means limited to advertising, newsletter swaps, group promotions, and promotional sites. But you don’t need to do all of them. When you’re just starting out, pick one or two platforms and really get those dialed in before you start adding more to your plate.

For my wife’s books, we are exclusive to Amazon. Authors who have books in the Top 500 of the Kindle store generate 80–90% of their sales directly as a result of their bestseller rank. These are all, essentially, free sales.

But to achieve a great bestseller rank and enjoy those organic sales, you need to tickle the Amazon algorithm enough to take notice of you, which you do by driving sales through your own marketing and advertising efforts, such as Facebook ads and Amazon ads.

Audience buildingAs an author, your biggest asset is your books. Your next biggest asset is your audience.

I’m not talking about your Twitter followers or Facebook likes. I’m talking about true fans of your books, who you have direct access to through email.

The issue I have with building an audience on platforms such as Twitter and Facebook is that you’re building this audience on rented ground. If your account on one or more of these platforms is suddenly shut down, you would lose your entire audience overnight.

To avoid this situation, by all means, build an audience on these platforms, but, make sure you are de-platforming people by encouraging them to join your email list, which is best achieved through offering them something in return for their email address, such as a short story, a novella, a bonus chapter, or even a full book; this is commonly known as a reader magnet.

With an email list, you can contact your audience at any time (within reason, of course), ask them to buy your new release, leave a review of your book, and let them know about a flash sale you’re running.

When your email list becomes large enough, you can drive a LOT of sales of your new releases and your backlist, and it won’t cost you a penny in advertising. Your world really is your oyster when you have an email list.

Just respect your audience, don’t spam them, provide value (yes, even entertainment is considered value), and share a little or a lot, whatever you’re comfortable with, about yourself, your writing—even Tibbles, your cat, who accompanies you whilst you write!

Remember, you are communicating with real people, so be sure to treat them as such. And ultimately, be your true authentic self.

ProfitUltimately, if you want to become or remain a full-time author, you need to make a profit (unless you have very deep pockets and don’t need the money).

Royalties are more bragging rights than anything else. The number that really matters is profit, or the money you take home in your pocket after paying for ads, promotions, etc.

The best way to keep an eye on your profit and other financials is to track your numbers. At a minimum, I would recommend tracking the following:

Royalties earnedTotal ad or marketing spend (you could break this down into ad spend for each platform)Total ordersTotal page reads if you’re in Kindle UnlimitedEmail subscribersProfitThis fourth pillar is perhaps the most important because, without profit, you will not be able to continue writing full time (again, unless you have no financial worries).

In your 30–60 minutes of intentional marketing sessions, your task(s) should be focused on one of these pillars.

Why 30–60 minutes per day spent marketing is all you needIn the beginning, I would spend four to six hours per day marketing Lori’s books. Granted, I learned a lot. But at the same time, I was tinkering with things too much, whilst also splitting my time, energy, and limited budget far too thin.

Since then, three children later, I now work on the marketing of my wife’s books for an average of 60 minutes per day; sometimes more, sometimes less, depending on what is happening at the time. If we have a book launch or promotion coming up, I’ll typically spend a little longer than 60 minutes per day, just to make sure everything is in place.

But in a typical week, 60 minutes per day is about average.

And you know what? Since cutting down my time to just 60 minutes per day, results have been better than ever.

In 1955, British author and historian, Cyril Northcote Parkinson, wrote in an article for The Economist that “work expands to fill the time allotted for its completion.”

This became known as Parkinson’s Law.

If you give yourself four hours to set up your Facebook ads, it will take four hours. If you give yourself 60 minutes, you’ll have it completed in 60 minutes.

When I’m in a 60-minute marketing session, here’s what I do:

Step 0: The night before, I plan out exactly what needs to be done in those 60 minutes.Step 1: I sit (or stand) at my desk knowing what I need to work on.Step 2: Put on a pair of noise-canceling headphones and listen to Brain.fm (music that has been composed to help you focus), put my phone in another room, and turn off all notifications on my computer (yes, that includes email!)Step 3: Work the plan! I work on exactly what I planned out the night before, nothing more, nothing less.Step 4: Review my work and reflect on what I’ve done.Step 5 (bonus): Reflect at the end of each week, and ask myself questions to help me improve for the following week.So how do I know what I need to work on? That’s where strategy comes into play.

How and why to craft a strategy for your author businessWithout a strategy, without direction, without knowing where you’re heading and why, you’re drifting. It’s like getting into your car and driving with no destination in mind.

Here’s how I define strategy: A strategy is set of choices or actions you make that positions your books (and your author brand as a whole) on the playing field of your choice (such as Amazon) in a way that you win.

Your strategy will set the intention for every single marketing activity you do. It will help you keep everything on track. It will help you identify what is and isn’t worth your time. What you should say yes to, what you should say no to.

The mistake many authors make is that they have a huge long list of tactics (the individual actions or activities you perform), but no strategy to tie them all together.

The result of this is that marketing becomes overwhelming because they have so much they think they need to do, and end up doing nothing because they have no idea where to start. This is sometimes referred to as paralysis by analysis.

And that’s why you need to identify which tactics truly move the lever for you.

Identifying your lever-moving marketing activitiesThere are countless opportunities out there for authors to market their books, and I completely understand just how tempting it can be to do it all. If you follow that path though, I can promise that you will burn yourself out and become a slave to your business. Ask me how I know!

The better, more sustainable option then, is to identify your lever-moving activities and double down on them. Don’t fret about what other authors are doing and think you need to do that too.

I’m not saying to never test new ideas; just allocate additional time to do so. The 30–60 minutes you spend each day marketing should be 100% dedicated to the lever-moving activities.

The best way I’ve found for identifying lever-moving activities is to write down every single marketing-related task you perform over the course of a week. Then look at that list and identify the 20% of tasks (because that’s all it will be) that are driving 80% of your results. These tasks will fall into one of the four pillars:

Book product pageTrafficAudience buildingProfitHow to plan out your days, weeks, and monthsPlanning may not be the most exciting thing to do (though, admittedly, I rather enjoy the process of planning!), but by taking the time to:

Plan out your goals for the weeks and months aheadKnow what you want to achieve and by when… you’re going to achieve so much more than you would with zero planning, or winging it.

The time you spend marketing will be 100x more effective than you thought possible because you’ll get more done in just 30–60 minutes than you otherwise would in an 8-hour day.

Without a plan, you’ll have 37 different things floating around your head, not knowing which one to work on today. Before you know it, you’ve replied to a few emails, doom-scrolled on your favorite social media platforms, refreshed your KDP dashboard 10 times, and 60 minutes later, you’ve achieved nothing meaningful. I’ve been there. Trust me.

Parting thoughtsI hope I’ve convinced you of the importance of planning your time effectively, and given you permission that it’s OK to not to be doing all the things.

Now, if you want to be everywhere and do all the things, go ahead. Just be very aware that if you’re saying yes to something, you’re saying no to something else. And that something else could very well be one or more of your lever-moving activities. And remember, you don’t need to do more. Try doing less, but doing it better. That’s only possible when you remove all the dead weight from your days, weeks and months, and focus your time, energy, and budget on the 20% of activities that are driving 80% of your results.

April 4, 2023

A Framework for Moving Beyond Your First Draft

Photo by Leah Kelley

Photo by Leah KelleyToday’s post is by author Amy L. Bernstein (@amylbernstein).

Driving along the back roads of Vermont, you learn to appreciate the nearly forgotten charms of the printed roadmap. GPS is spotty in Vermont, and it’s easy to find yourself on a narrow, deeply rutted dirt road that seems to lead nowhere. You get to a place where you literally can’t see the forest for the trees. And then you know you are well and truly lost.

Contemplating what comes after you’ve completed the first draft of a novel is a lot like getting lost in Vermont. The journey up to now has been beautiful and inspiring, but at some point, you have to admit that you have no idea where you’re going or if you’ll ever find your way back home.

For the writer (a traveler of sorts), this predicament raises existential questions: How do you find a way back to the beginning, or else on to the next great destination? What if you can’t decide where to go next? Why does being lost seem fun at first—and then kind of scary, even hopeless?

Getting used to getting lostMany new writers working on a first novel never make it past a first draft—not because they’ve stopped believing in their story or because they’re lazy. They grind to a halt at the very first “The End” because they don’t know what comes next. There is no obvious inciting incident for rewrites and revisions. A great big question—How do I make this better?—often goes unanswered.

Experienced writers, on the other hand, know that their first draft is never their last draft. They know, too, that getting at least a little bit lost between drafts is par for the course. But that doesn’t mean the post-first-draft transition is easy. As in Vermont, where tiny roads branch off in all directions, figuring out which direction to head as you move from first draft to second can be a head-scratcher for novice and experienced writers alike.

Figuring out how to get from “shoveling sand into a box,” as Shannon Hale calls the first draft, to something polished enough to pitch, is not easy even for best-selling authors.

Novelist Jennifer Egan likes her first drafts to be “blind, unconscious, messy efforts.” It’s a long way from there to her polished, deeply researched books. The magic doesn’t happen overnight. John Irving admits to writing first drafts in a matter of weeks, but then spends months or years revising.

Obviously, there is no magical treasure map that every writer can follow. And even if you think you’ve found the right map for your journey, how do you know if your sense of direction is any good?

First drafts are often private affairs, the pages lying in a hermetically sealed vault, away from prying eyes. As Terry Pratchett famously said, the first draft is about you telling yourself the story. How, then, do you gain sufficient critical distance to revise your own work?

Toni Morrison flagged that challenge for all of us. “[Y]ou have to be able to read what you write critically. … [and] surrender to it and know the problems and not get all fraught,” she said.

Alas, we are not all Toni Morrison-level geniuses.

Asking the right questionsI believe we can inject a modicum of sanity into the second-draft process by focusing on universal elements of storytelling that help a writer to set priorities and to answer, at least in part, the “How do I make this better?” question.

This effort begins by focusing on five critical aspects found in most novels. A writer who systematically and honestly checks in on how each aspect functions in her novel—and identifies where rewrites and revisions are needed scene by scene to make these elements work better and harder in service to the story—is on the way to structuring a better draft.

Two big caveats before continuing:

I’m generally referring to mainstream genre and commercial fiction, rather than deeply literary or experimental fiction, where breaking conventional rules of storytelling is expected.Expectations for what a second draft should achieve vary by writer. I’ll impose my bias here: I believe a second draft can and should do a lot of heavy lifting. The whole point of the virgin revision process is to make the story and its characters deeper, richer, and sharper. This is not the draft to be tinkering at the margins.The second-draft checklistThe building blocks of the second-draft revision process are grounded in these five aspects of the novel, which stand alone and also interact with and affect one another:

The main character (MC). The MC must be fully present in the novel: sharply drawn, replete with contradictions, a catalyst for action, and gives the reader a reason to care.Emotional stakes. The stakes should be high, clearly differentiated among the major characters, and serve as a source of tension and conflict.Essential scenes. The goal is to (a) identify scenes ripe for cutting or trimming because they don’t move the story forward or serve as static info dumps; and (b) detect where new scenes are needed to deepen a character’s motivations, reveal conflict, or add other critical texture.Pacing. A novel that unfolds at just one speed (all fast, all slow) is bound to bore or exhaust the reader. Variable pacing among scenes and between chapters is essential.World-building. World-building isn’t only for fantasy, sci-fi, and historical fiction. Every novel is built on rules, and the writer must ensure the rules are consistently applied and sufficiently sketched. Click on image to increase size of chart

Click on image to increase size of chartWhile these five building blocks are not definitive, any writer struggling to figure out what to do with their completed first draft needs to start fresh somewhere. This checklist will, at the very least, send you out along new byways, where you will make fresh discoveries about what you’re trying to say.

The key to making this checklist work for you is to work it hard: Study how each aspect functions on its own in your novel and how they work together to generate conflict, suspense, or whatever big flavors your novel needs to really sing.

Congratulations, by the way, on completing your first draft. Now get to work.

March 31, 2023

Why You Should Be Writing on Social Media

Photo by Karolina Grabowska

Photo by Karolina GrabowskaToday’s guest post is by Allison K Williams (@guerillamemoir). Join us on April 5 for the online class Write Better With Social Media.

Social media doesn’t sell books in any provable way. No one strolls into their local independent bookstore to ask for “This book I saw in a tweet!” We don’t check a box marked “Found it on Instagram” on our Bookshop order. Authors can’t get social media impact statements with their royalties, because publishers can’t get that information either.

Even platform isn’t the point. If you’re a memoirist, you may never build one big enough, and novelists don’t need it.

You should still be writing on social media.

This isn’t about using Facebook, Twitter, or even LinkedIn as a commercial (nothing makes me mute faster than three “buy my book” tweets in a row!). Or trying to kill it on BookTok.

Rather, it’s about using social media in the way we all did ten years ago: as a means to genuinely communicate our ideas, our topics, and our point of view to people who become our audience.

It still works for that.

You don’t have to buy an ad.

You don’t have to dance.

You don’t even have to put on pants.

For authors, social media has four main purposes—but each of these can be done off social media, too.

1. Write betterPosting to social media is a low-stakes submission to the world. No gatekeeper stands between you and your audience, and the fleeting nature of social platforms means if a joke or a flash story bombs, no one will see it again. (If it’s great, it’ll be retweeted and reposted for a good long while.)

I’m a nonfiction writer focusing on writing craft. On social media, I reach—and expand—my audience with information, support, and sharing (parts of) my real self. On Instagram, I’ve written mini-essays: “get to know me,” “hey I write things that make you think,” and “here’s a writing tip.”

I’ve also developed my voice as an essayist with Instagram posts, one of which went on to be published in a “real” literary magazine. The discipline of the character limit helped me consider exactly what words told my story. Like a free-verse poet practicing sonnets, the constraints of each platform focus our work. A 600-word newsletter has a different rhythm than a 280-character tweet. The same principles apply to building a book from an essay or a short story.

Whatever you do, make it yours.

If your life today is, “I got rejected by the same magazine again,” write that. Write about how you made 100 copies of the rejection, folded paper airplanes, wrote “Never give up!” on the wings, and flew them into the playground from the elementary school roof. Or how you dreamed about doing that. Or how you added another hatch mark on the bare plaster of your crumbling bathroom wall, how every day you sit on the toilet and count rejections like a prisoner counting days. No matter which of those is closest to your own experience, someone reading will gasp in shock and recognition, “Me too!” And then they will read you again next week.

2. Generate book materialAbout half of my own book, Seven Drafts, started as posts on the Brevity blog. Reader comments let me know what I left out, or what to write next. When I sat down to write an 85,ooo-word book in four weeks (not kidding!), I started by collecting every blog I’d written about editing and publishing. The material got reorganized, reframed and rewritten, but it was like the Magic Writer Elves had come in the night and left a first draft for me to find in the morning. Your long Facebook comment can be a rant—or a careful examination of why you believe what you do and why that matters.

3. Build literary communityAs I wrote on the Brevity blog a while back, “These ARE my real friends.” Social media recreates the experience we had in high school and college, of frequent, casual meetings and finding out both the big changes and the little details of our acquaintances’ lives until they blossom into friendship. The last writing conference I attended was filled with cries of “I know you from Instagram!” Writers meeting in person for the first time knew what book each other was working on, how the kids were doing and the dog’s name. Those writers had already made connections strong enough to like each other—meeting in real life cemented the bond. Now, two years later, they’re ready to support each other’s books on the way to publication.

4. Be seen alongside comparable authorsBeyond the comparable titles or authors you might list in a query or proposal to show your novel’s tone and genre, social media is a place to position your work next to the authors you love. Engage with their followers, and some will (gradually) become your followers too. Amber Sparks talks about her day and the discoveries in her writing life—you can respond by talking about yours, and one more person sees your name in conjunction with hers, as if you’re already shelved together. I was able to ask more than one author to blurb my book after positive interactions on Twitter and Facebook.

Where you’ll find the payoff for your careerYou do not have to use social media, although you may have noticed that, without it, all four of these purposes take longer, cost money, and/or require privilege to access.

“Building platform” isn’t counting clicks. Platform means becoming a part of the discussion in the community you want to reach. Instead of hating social media on principle, find the platform you like. If you already like social media, write more deliberately. Polish your sentences and your comedy on Twitter. Look for the comp titles you need (and your next read) on TikTok. Learn about publishing and share your own knowledge on LinkedIn and Facebook. Maybe even take a photo and write a mini-essay on Instagram—it’s technically still there!

For both fiction and nonfiction, “building platform” boils down to making your audience aware that you exist, and you’re writing something they care about. By the time your book baby reaches the shelf and your audience is wondering, “Where do I know that author from? Better check this out!” you’ll have polished, published and shared your words so often and so well, they’ll be glad they picked up your book.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, please join us on April 5 for the online class Write Better With Social Media.

March 30, 2023

Banish Writer’s Block in 5 Minutes Flat

Photo by Wilhelm Gunkel on Unsplash

Photo by Wilhelm Gunkel on UnsplashToday’s post is by author and writing coach April Dávila (@aprildavila).

Three years after declaring my intention to be a professional writer, I was frustrated. Despite holding a brand new master’s degree in creative writing, I couldn’t seem to figure out my novel. My short stories were serially rejected by a wide array of publications, I was working full time, and had two little kids. I was exhausted all the time. More than once I considered giving up on my dream of becoming a writer.

Saved by mindfulnessThankfully, I am nothing if not persistent. About nine years into my journey, things began to shift. I finished my manuscript, found an agent, and signed my first publishing deal. A short story I wrote was not only published, it was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. I wrote a second, more complex novel in a fraction of the time it took me to write the first and while I was doing that, my first novel won the 2021 Women Writing the West Award. My writing career finally felt like it had some momentum.

Looking back with curiosity, I noticed that the changes in my writing practice—my ability to quiet my inner critic, my willingness to be with uncomfortable emotions as I wrote them, my resilience in the face of rejection—all centered around a simultaneously increasing dedication to the practice of mindfulness meditation.

Mindfulness meditation, in addition to offering numerous health benefits, can also improve focus, boost creativity, and even offset the cognitive decline associated with aging. None of this is a surprise to me, as it lines up perfectly with my lived experience, but the number one thing I wish I could share with every writer is how meditation allowed me to completely do away with writer’s block. Forever.

Banish writer’s blockI don’t suffer from writer’s block anymore. Mindfulness meditation has allowed me to pull back the curtain, like Dorothy did to the Mighty Oz, and realize that “writer’s block” is just a catch-all phrase we use to describe the thoughts (conscious or unconscious) that keep us from writing.

These thoughts can be simple (is there a writer alive who hasn’t sat down to write and suddenly realized the dishwasher needs to be emptied?) or complex (our fears and anxieties around writing can be formidable), but they are all just thoughts.

Once we learn to see them as such, we can acknowledge them, put them aside, and continue on with our writing.

Mindfulness of thoughtThe technique I used to free myself from writer’s block is actually quite simple and only takes five minutes. It is often referred to as mindfulness of thought meditation. Here’s how it works:

Every day, before you begin writing, set a timer for five minutes, find a comfortable seated position, and take a few deep breaths. Closing your eyes can help to minimize distractions, but it’s not required. Then choose something to focus your attention on, such as your breath or the sounds in the room. This will be your anchor, the place to rest your thoughts for the duration of the meditation.

That’s all there is to it. For five minutes you focus on that anchor and do your best to notice when your mind wanders. (Scroll down for a video of this guided meditation.)

You may notice thoughts like “what’s the point of this?” or “this is boring.” Or you may not even notice that your mind has wandered until you realize you’re planning dinner or drafting an email in your mind. Whenever you notice a thought, whatever it is, just let it go and come back to your anchor.

The goal here is not to make your mind blank. Instead, we aim to notice when we get caught up in thoughts. That moment of noticing is what mindfulness is all about. Then let the thought go and come back to the anchor.

Writing as meditationWhen the timer goes off after five minutes, simply shift your attention so that the writing becomes your anchor. As you start typing, you will notice thoughts arise.

You may suddenly remember a chore that needs doing, or you might hear a little voice in your head telling you that what you’re writing is crap. These are all just thoughts. Let them go and come back to the anchor. Keep writing.

By practicing this five-minute meditation regularly, you will become a master of focus, able to dismiss distractions before they even fully form as thoughts. This kind of concentrated focus leads to the most delicious state of flow. Words pour onto the page and ideas float up as if out of nowhere.

Finding your flowOur modern world is swamped with distractions and our brains simply cannot function optimally when we rapidly switch between tasks. When we multitask we are less creative, make more mistakes, and tire quickly.

You can think of your brain as having a limited amount of processing ability, just like a computer. If we have too many programs running at the same time, our thoughts get slow.

The good news is that we can use this limited processing to our advantage. If we focus intensely on one thing (our writing), our ability to process other things falls away. This is why hours tend to fly by when we’re “in the zone.” Our brains are simply too busy being creative to keep track of the clock. As an added bonus, focusing deeply on something that is interesting to us produces dopamine and makes us feel good.

Even if you only rarely suffer from writer’s block, you can keep this five-minute mindfulness of thought exercise handy to help you break through when it does arise. Once you get used to engaging in that wonderful state of flow whenever you wish, you just might find yourself becoming a regular meditator.

March 29, 2023

How Two Authors Collaborated on a Biography

Today’s Q&A is by author Isidra Mencos (@isidramencos).

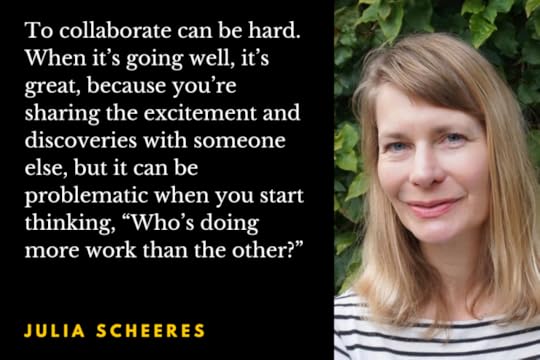

The recently published Listen, World!, co-authored by Julia Scheeres and Allison Gilbert, is a page turning biography of Elsie Robinson, the most read woman journalist of the twentieth century, until now unjustly forgotten.

Julia Scheeres, New York Times bestselling author of the memoir Jesus Land, wrote the book in her hallmark cinematic, vivid style, providing fascinating insight on the life of this trailblazer who defied conventions and relentlessly pursued a writing career until she reached the top. Allison Gilbert provided thorough research on both Elsie’s writings—over 9,000 columns published in papers like The Oakland Tribune and the San Francisco Call and Post and a memoir—and the historical context that brings the Victorian and post-Victorian eras to life in the book.

I talked with Julia Scheeres about the nuts and bolts of their collaboration, the craft choices that made this book such an engrossing read, and the lessons she gleaned from Elsie Robinson’s life and career.

Isidra Mencos: I loved your book, Julia. I understand Allison started this project, and she researched Elsie for a total of eleven years. At what point did she contact you and ask you to help with the writing process?

Julia Scheeres: Allison had failed to sell a book proposal on Elsie Robinson, so she contacted me to help her craft a compelling narrative. We were able to combine her research skills—she’s a former CNN producer—with my ability to create a narrative arc and tell a story scenically. When I started writing and I needed a very specific data point to illustrate a very specific story, I would tell Allison. For example, I could ask her, “Allison, can you find out what the divorce rate was in Vermont in 1912?” and she would find out. It’s great having a co-author because you can divvy up the job and cover the same amount of ground twice as fast.

How did you start your collaboration? Did you read the research Allison had accumulated before you started to write, or did you start by reading Elsie’s memoir and columns?

The research Allison did prior to the writing was mainly of Elsie’s works. She had Elsie’s memoir converted into an electronic format, and she also had someone help her create a database with all of Elsie’s columns, but it wasn’t specific to the book that we ultimately worked on.

One of the first steps I took was to read Elsie Robinson’s memoir. Then we spent a lot of time talking about the scope of the book: where it would start, where it would end, what each chapter would be focused on.

I am a big believer in outlines, so I outlined every chapter: this is what the chapter is about, this is the time period, these are the scenes that I want, this is the research that I need, this is the main tension in this chapter, these are the beats.

For example, the chapter on Hornitos. What was the big drama in this chapter? Well, this is when Christie, Elsie’s husband, finds out she’s living in Hornitos with Robert Wallace, and he cuts her off financially, so Elsie is forced to work as a miner to make ends meet, and at the same time she’s trying to send out freelance articles. This is my favorite chapter, because Elsie is so amazing and hardworking: she gets up in the morning, feeds her kid breakfast, walks four miles to a mine, works all day—backbreaking labor in the hot sun of Hornitos—walks home for four miles, makes supper, helps her son with his lesson plans, and then, when she is exhausted, she types up these short stories and sends them off.

Aside from the main outline with the beats of the story, each chapter had its own folder in our shared Google Drive. For example, chapter 5, “Marriage,” had many folders: a folder with a picture of Elsie’s wedding announcement; a folder with information about the house she moved into, the mansion her in-laws had; a folder with the newspaper her in-laws published; a folder on the church she went to; a folder on her son; and then there were stand-alone documents about women’s sphere, sex in marriage, academic papers about Victorian weddings and expectations; then we would go to her poems and columns to see if she had new reflections on marriage. It was pretty detailed.

How did you decide where to start and end Elsie’s story? Because the last thirty years of her life are summarized in an epilogue.

It made sense to start Elsie’s story in Benicia [where Elsie grew up] because it was so formative in forging her independent character. Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood goes deep into Holcomb, the small town in Kansas where the murders happened. He talks about how it fostered this sense of trust among the town’s people, so when this horrific killing happened, they couldn’t believe it. Our towns form who we are. You were lucky enough to be born in Barcelona, one of the most beautiful cities in the world, cosmopolitan; I was born in a very rural, small Midwestern town which is very cloistered and close-minded; Elsie was born in Benicia when it was the Wild West, and she had a very free childhood. She wandered around, asked questions, talked to anybody she wanted to, the prostitute, the priest, and everyone in between.

And we knew that we wanted to end the book before Elsie became famous, because after someone becomes famous, who cares? A good story in any medium is all about somebody wanting something and then trying to attain that goal, having obstacles thrown up in their way, and getting over them or around them. The interesting part is the struggle, the tension on the page. In life, tension sucks, but in storytelling is absolutely necessary, it’s what makes us want to keep reading, keep following the story.

The introduction finds Elsie at the peak of her career, when she writes a letter to William Randolph Hearst making demands that she wouldn’t have dared make before. Did you know from the beginning that you wanted to open the book with that letter or was it something that you decided later?

It came later. It was a very shrewd decision on Allison’s part to have that intro when Elsie tells William Randolph Hearst, “You haven’t given me a raise in nine years. Why not? And don’t you dare tell me that I should be grateful because I’m a woman.” It immediately shows the reader Elsie’s stature.

Reading the acknowledgments it looks like you used hundreds of sources, from historians, librarians, and others that you interviewed, to books, magazines, newspapers, and of course, Elsie’s enormous production. How did you organize this material?

We worked in Google Docs, because Allison is in New York and I’m in California. We had a huge directory in Google, everything from photographs to primary content, to research, to these obscure academic papers that we came across, that all helped us form the story. I kept having to buy more space from Google because I was running out.

Elsie’s writing is interspersed throughout the book with your own narrative. It’s wonderful because she’s a very engaging writer. I was wondering if you decided consciously how to differentiate your voice, so it wouldn’t be taken over by Elsie’s voice. And how did you go about choosing those fragments? Did you read thousands of columns or mostly the memoir?

When there was a big scene, we always deferred to Elsie to tell the story. That was one occasion where we would let her voice stand on the page. Another occasion would be her descriptions. Some of her descriptions of Benicia in the early days, and what it was like to live there when the sun went down and all the prostitutes marched up the street in their sheer dresses, and all the men would be watching this parade are amazing. Elsie was not only a journalist, she was a poet, she was a fiction writer, she was an illustrator…she had skills in so many different art forms, I was in awe. So I thought, “I’m going to step back and let her tell this.” And it worked great because she has such a distinctive voice.

And how about your voice? Did you feel like you had to choose a different narrative voice than what you used for your previous books?

Obviously we couldn’t use the same flair that you would use in a memoir, so it was a bit more muffled compared to Elsie’s, but there are ways that you can jazz up your sentences or make them sound more interesting. It was a balance of letting Elsie have her space—and she was very ebullient, she could be very effusive and wordy—and having my space, so I tried to almost go in the opposite direction and be very succinct. There were so many cases in this book when truth was stranger than fiction, that I didn’t have to work hard at it. You read the pieces about what it was like for brides in this country when they got married with no information on what to expect on your wedding night. Just finding those pieces of women’s history was fascinating and using them was enough to make the narrative engaging.

I love how you incorporate the context of the era, the place of women in Victorian times, and after the two World Wars, the history of Hornitos, the history of Benicia. You could have gone in a different direction. Say, let’s find a publisher and bring Elsie’s memoir back and write an introductory study. Instead, you decided to write a nonfiction book about Elsie, using pieces of her memoir and her columns. I wonder why you chose to do that and if it was precisely to incorporate all this context.

That’s a great point. Sure, we could have just republished her memoir, but she’d been long forgotten, so that wouldn’t have had any impact. And we wanted to incorporate her context. She overcame tremendous odds to become this renowned journalist, and that was what was interesting, everything she faced and overcame.

And another thing is that she didn’t tell the whole truth in her memoir, there were parts she didn’t include, like her love affair with Robert Wallace. She never admitted to being his lover, but all of the lawsuits [from her husband, who was suing Elsie for divorce and custody of their child on the grounds of adultery] state they were lovers. Robert and Elsie were living together in Hornitos. He was a womanizer, very sensual, and she was starved for attention. How could they not be? That’s why it was more interesting to do a biography because, as you know, having written a memoir, you choose to leave things out, you present one side of yourself to the world and if you become famous, and somebody pokes at your life, they could notice, “Oh, she didn’t write about this affair.” So, in a way it makes the story more objective. It’s a journalistic piece, it’s not hagiography. Yes, she was amazing, but she also did not disclose some facts about herself, which are fascinating.

How long did it take you to write the book?

We asked for a two-year contract because I was working on other things at the same time, but once I started writing, I wrote a chapter a month.

Were you sending a draft of each chapter to Allison?

I would upload every chapter to Google at the end of the month. She would read it and give me feedback, and we would talk about it.

How many of those 9,000 pieces that Elsie wrote did you read?

Allison had an assistant who catalogued all of her columns according to theme, so we could do a word search in this database and find, for example, wherever she mentions her son.

Do you have any plans to produce an anthology of Elsie’s best columns now that you have digitized them, or do you want to leave this for someone else?

There are no plans to do that. It would be interesting, but I’m already moving on to my next project. It feels like all this should be made available somewhere so people could benefit if they are doing research on the era or on women.

The precision of the details in the book is outstanding. It could be a movie, it’s so vividly described. Are you paraphrasing Elsie’s words or are the descriptions based on your own research?

It was a mix. Sometimes we used Elsie’s facts, sometimes it’d be reported facts from going to a place like Hornitos, Benicia, San Francisco, other times we went through old newspapers. The Library of Congress has newspapers dating back to the 1700s that you can search, like the Brattleboro Reformer. We could go through and search for the Crowells, her in-laws, and pull out all this information about their mansion. The same thing about Hornitos, Benicia. There is so much information at your fingertips, and it was during Covid, when many archives were closed, but we were able to access a lot of information online.

What was Elsie’s most inspiring trait for you that perhaps changed you as a writer or as a woman?

Her drive. I feel like I’m pretty organized and driven, I’m able to focus really well, but I’ve been improving working on my focus just because her drive was so outsized. Elsie wanted one thing, and she made it happen. She wanted more than being married to a rich guy and being set for life, which is what success meant for most Victorian women—to be a mother and the wife of a wealthy man. Elsie was bored, and she wanted more; she wanted to be a writer, she wanted to be an artist, and she pursued that goal relentlessly. She fell on her face a couple of times, like when she moved back to California, and couldn’t find enough work and then had to go work in a gold mine in Hornitos. This idea of pursuing what’s important in life, pursuing your dream no matter what, was one thing that I really admired. And another thing (spoiler alert), when her son dies, she suffered greatly but she says at one point, “You know what? Grief is a universal issue. You’re not special because you go through the death of someone close to you. Dust yourself up and get up. You can’t stop living.”

What was the most surprising thing as you were writing this book?

I didn’t know a lot of the context about women’s history. The biggest surprise was learning about Ida Craddock, the activist who tried to offer information on sexuality to women, so on their wedding night they wouldn’t be terrified and surprised about what was going on. She wrote educational tracts for men about how to respect a woman, everything that today is health education class in sixth grade or sex education class in high school. She was arrested for it, and she killed herself rather than going back to prison a second time. Hearing and seeing these stories time after time of women trying to help other women—because we’ve been a second class category of citizenship for so long—was an interesting thread. There wasn’t enough information on women’s health, and gynecology was considered a lesser kind of medicine, so women turned to other women for help, and I wasn’t aware of the extent that this had happened. A sisterhood sprung up.

Amazon • Bookshop

Amazon • BookshopWould you recommend co-authoring to other writers or would you do it again yourself?

To collaborate can be hard. When it’s going well, it’s great, because you’re sharing the excitement and discoveries with someone else, but it can be problematic when you start thinking, “Who’s doing more work than the other?” I didn’t have this issue with Allison because she’s a very hard worker, she’s a reporter, and knows how to make deadlines, so we were a good match. But I know of other collaborations where there’s always someone who’s doing more work than the other person and resentments can happen.

What’s next for you, Julia?

I can’t really say, but I’m working on something related to my Jonestown book that I’m very excited about.

March 28, 2023

What Is Upmarket Fiction?

Today’s post is by literary agent and podcast host Carly Watters (@carlywatters).

Ask five different industry members and you’ll get five different answers. But what really is “upmarket” fiction?

I’ve spent the last thirteen years helping writers get book deals and the last two years on our podcast The Shit No One Tells You About Writing helping unpublished writers learn how to categorize their work and I have an answer to this. Upmarket fiction is a blend of commercial fiction and literary fiction, but how it gets blended is where writers and industry members can’t always agree.

The nuances of upmarket fiction are confusing because the lines are blurry to those who don’t see it every day, but I have a method to share with you to better understand the category. Here’s a definitive guide to upmarket fiction.

It has universal themes everyone can connect to, with a hyper-focused plot.Universal does not mean meandering and expansive. Universal means ideas that travel. Love, loss, grief, trauma, family secrets, and identity show up in upmarket fiction because these are the books that start hyper-specific, like a dust bowl fiction called The Four Winds, and ends up traveling around the country and the world (selling translation rights as they go).

Like Mika in Real Life, we get into them for the plot and end up being swept away by how it makes us feel and then we want to go tell everyone else about it!

Like The People We Hate at the Wedding, we all love the drama of a messy wedding, especially one that includes international travel.

Foreign rights agents never truly know what will sell, but emotionally gripping, universal themes are the books they always want to share with their foreign contacts because they’re not geographically bound. Upmarket novels have potential to sell well in translation because we’re all human.

The aim is thoughtful discussion of real world application.Ripped-from-the-headlines books often fall into this category. Books where the topic is already being discussed in pop culture or the news and captured in fiction like Girls with Bright Futures (social satire of the 1%), We Are Not Like Them and Such a Fun Age (both hold a mirror up to society’s social justice conversations) are great examples. Books that make readers think about “What would I do in that situation?” or “What if that happened to me/my sister/my family?” are ways that readers are pulled into the book in a nuanced way that inspire deep thought about how the reader feels about the subject matter or character conflict and their own personal relationship to it.

It’s a blend of literary and commercial: quality writing with a high-concept hook or unique structureSo here’s where the blend comes in. The literary part is that the quality of writing is high (doesn’t need to be capital L literary, though, and actually shouldn’t be), and the commercial part is the hook. You immediately get why you need to read it and read it now, but you’re going to keep reading because the writing is really strong.

What is a high-concept hook you might ask? The Guncle, One Day, The Midnight Library and This Time Tomorrow come to mind. A high-concept hook is a premise or hook that you can immediately wrap your head around and see how it can drive a novel: a “what if” hook, a hook that might be about an existential question but is captured in a brilliant single line.

Common characteristics of literary fiction

Common characteristics of literary fiction Common characteristics of commercial fictionIt’s a character-driven novel.

Common characteristics of commercial fictionIt’s a character-driven novel.If commercial fiction is plot-driven and literary fiction is quality-of-language driven, then upmarket fiction is character-driven. I think of The Most Fun We Ever Had, Fleishman Is in Trouble, White Ivy or Recipe for a Perfect Wife when I think about characters who propel the book forward. It can be multi-point of view or single point of view. The book often hinges on the growth and/or secrets of this main character or more than one character if it’s multi-point of view. See my case study of Lessons in Chemistry below to learn more.

It’s appropriate for book club discussion.Do people actually want to talk about and debate matters in this book? A lot of writers think their book would be good for a book club, but what does that mean? You want to tour around to book clubs across the country? Or your book has enough material and fodder to get people discussing opposing views and alternate opinions with their closest friends and neighbors?

Luckily, we also have Reese Witherspoon, Read With Jenna and Good Morning America helping us lead the way with national book club choices (and generating lots of sales for the industry!) and I would argue 90% of their monthly book club choices are categorized as upmarket. We have The Last Story of Mina Lee, L.A. Weather, The Fortunes of Jaded Women, Someday, Maybe, and many more national book club picks to choose from.

It’s genre blending and adding mystery.I love a little genre blending in upmarket fiction and Nine Perfect Strangers, The Other Black Girl, Where the Forest Meets the Stars, and Where the Crawdads Sing deliver on this. What mystery are we trying to solve in both a thoughtful and page turning way? Readers are both immersed in solving the puzzle but allowing themselves to be shepherded slowly through the suspense because they want to savor each page. They never want the book to end because then they’d be done! But they also want to know what happens. These types of books get recommended to all the readers’ friends and family, and get high library request rates.

Case study: Lessons in Chemistry

Tone and marketability come to play in this case study. Lessons in Chemistry is an example I want to discuss because the way a book is packaged or marketed and the writing itself can sometimes be at odds. Many readers said the Lessons in Chemistry cover (of the U.S. edition) made it appear more lighthearted than it actually was—the cover wasn’t interpreted to be as “serious” as the subject matter. I believe Lessons in Chemistry to be upmarket but it was packaged more commercially. It didn’t affect sales at all. This book sold very well, so perhaps the cover did the job!

We could contend that this main character wasn’t especially likable, and some might argue that upmarket fiction has to have at least one likable character but I don’t know if I agree. Unlikable characters can certainly get book clubs talking; however, the goal is for readers to finish the book—not just buy it—and likability and entertainment value go far in this category. I chose this for my book club and we had a very intense discussion. I loved it.

Lessons in Chemistry is very character-driven. We spend all of our time with Elizabeth Zott but there’s a high-concept element where she talks to her dog, who is named Six-Thirty, and we also get interiority from her dog’s POV. This allows us to feel incredibly close to Elizabeth while also seeing her from another angle even if it isn’t another person, but Six-Thirty.

The book is historical, but simultaneously feels urgent and contemporary. This is common in upmarket fiction. Lessons in Chemistry is tackling sexism in a historical context, but so much of it still feels relevant today, which gives book clubs the opportunity to talk about what’s changed and what’s still the same. It’s a safe space for discussion because it feels distant and close at the same time.

It was a GMA pick and a 2022 Goodreads Choice winner for best debut novel. The Guardian review said Lessons in Chemistry is “a polished, funny, thought-provoking story, wearing its research lightly but confidently, and with sentences so stylishly turned it’s hard to believe it’s a debut.”

Do you see how each word in that review checks the upmarket boxes?

How do I know if something’s upmarket at first glance?At the time of this writing, the covers tend to have bright elements, large title text, hidden images or icons if you look closely.

Upmarket fiction can published as trade paperback original or hardcover; it depends on the publisher. Some want to capture the trade paperback market and move a lot of units and some want that sturdy hardcover appeal that libraries love and capture a higher price point. These are larger discussions within each imprint.

Finally …The most important thing to remember is that upmarket fiction operates on a spectrum. Some upmarket books will lean more commercial, and some will lean more literary—all authors tackle these issues in a unique way. In my examples above, some are more commercial/upmarket like Nine Perfect Strangers and some are more literary/upmarket like Fleishman Is in Trouble. These are guidelines, not rules, and I love when I’m proven wrong, but I’ve been doing this thirteen years, sold over one hundred books, and I’m generally pretty right!

I know what I’m going to hear from everyone: “I’m pretty sure all good fiction falls into this upmarket category!” And you know what, they might. I’m very willing to discuss these nuances any time, any place, because that’s what makes good books relevant and keeps us talking about writing, marketing, and packaging. However, as an agent it’s my job to recognize these subtle differences and help place these books with the right editors so they can find readers.

March 24, 2023

5 Reasons to Write Your “Taboo” Stories

Photo by Anna Shvets

Photo by Anna ShvetsToday’s post is by writer and editor Katie Bannon (@katiedbannon). Join her on Thursday, March 30 for the online class Writing the Taboo in Memoir.

Writing memoir is always a vulnerable experience, but some stories are especially difficult to tell. Topics like mental illness, sex, and violence are often branded “taboo” and can be among the most challenging material to write about. In many cultures, we’re taught to avoid these topics, and that sharing them is TMI (“too much information”).

But at their best, these narratives speak to our darkest truths and teach us what it means to be human. Despite the challenges of writing about stigmatized topics, sharing our vulnerable, deeply personal stories can be incredibly healing. And not only that, but these stories can make for the most compelling writing for readers.

1. Writing about taboos can give our stories heat and urgency.Emotionally charged, vulnerable experiences lend themselves to high-stakes storytelling. In memoir, we are challenged to answer the question of: “So what?” Why would a disinterested reader, who doesn’t know us from Adam, care about our lives? Taboo topics tend to be rife with conflict and dramatic tension, among our best tools for engaging readers in our stories. What’s more, when we lean into stigmatized topics, we invite readers to wrestle with the same complexities we’re examining in ourselves—this gives our storytelling urgency and nuance, which keeps the reader turning the pages.

2. Vulnerability can make us more trustworthy narrators.In memoir, readers want us to tell the truest, most candid versions of our stories. If they sense that we are holding back, being evasive, or trying to present our lives and ourselves as rosier than the reality, we risk losing their trust. Not shying away from the thorny, messy truths of our lives sends a powerful message to the reader. It shows them we are willing to lay bare our most difficult truths—even when, and perhaps especially when, these are unflattering. Readers respect writers who come across as honest and authentic—facing challenging material head-on, without sugar-coating it, shows our ability to grapple with complicated memories. This kind of honesty can help build our credibility as narrators, while establishing a more intimate connection between the writer and reader.

3. Writing the “unspeakable” allows us to reclaim power.Often, what is categorized as “taboo” or “unspeakable” has a lot to do with power dynamics. For instance, topics like sexual assault and racism have long been stigmatized; this is a way of silencing voices of dissent, those that might disrupt the established social order. Writing about taboos helps jumpstart conversations about some of the most important topics of our day. We can break through the forces that attempt to silence us, instead using our stories as a way of speaking truth to power. This is especially the case in marginalized communities, where voices have been systematically shut out—writing the hard truths can be empowering for the writer, and illuminating for readers.

4. We can reduce shame in ourselves and others.Writing about vulnerable topics has the potential to promote significant healing. When we give voice to the rawest parts of ourselves, we take control of our stories rather than them taking control of us. Writing in this way forces us to investigate the complicated web of our thoughts and feelings, increasing self-acceptance and reducing shame. Additionally, when we are vulnerable on the page, we invite readers to do the same—to face their own difficult truths and find more gentleness and healing. In addressing stigmatized topics, we have the opportunity to cast light on stories that are too often shrouded in shame and secrecy. When a reader sees themselves in our stories, it sends them the message that they are not alone. In a time when isolation and division is on the rise, there is enormous power in helping our readers feel heard, seen, and understood.

5. Taboos speak to our darkest truths as humans.Vulnerability is integral to the human experience. All of us have experienced the shame, guilt, grief, and pain that comes from having difficult experiences. When we write deeply personal stories, we can tap into universal truths that will resonate with any reader. The pain of feeling all alone. Of being otherized. Of not feeling good enough. No matter what the specifics of our “taboo” stories are, we have the capacity to elevate our experiences beyond the personal, digging into the messiest and most essential parts of what it means to be human. This is what distinguishes good memoir writing from great memoir writing—when we can use our own vulnerability as a stepping stone for mining the intricacies of the human experience.

Memoir is all about complexity and vulnerability—leaning into messy truths, rather than the tidy, “prettied up” versions of our lives. While the journey of writing taboo stories has its challenges, the rewards are vast—both for the writer, and for the reader.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Thursday, March 30 for the online class Writing the Taboo in Memoir.

March 23, 2023

What Memoirists Can Learn from Historical Novelists

Photo by Mr Cup / Fabien Barral on Unsplash

Photo by Mr Cup / Fabien Barral on UnsplashToday’s post is by author and book coach Susanne Dunlap (@susanne_dunlap).

At first glimpse, memoir and historical fiction may seem worlds apart. But many of the decisions historical novelists have to make to create a compelling narrative overlap with memoir more than you’d think—especially for writers of biographical historical fiction.

Both genres deal with events that really happened and people who actually existed. And writers of both genres have to make decisions that somehow mold reality into a story with a shape, an arc, and meaning.

It all starts with the question of time.

Timelines and story arcsTime is at the foundation of the entire experience of reading a book. A novel or a memoir is consumed by the reader over a span of time that sometimes expands, sometimes contracts depending on the balance of scene and summary. A reader invests time in the reading of the book, and it has to be worthwhile for them.

It’s your responsibility as a writer to control that passage of time, and it starts with identifying your story’s timeline, finding the optimal beginning and end that will create the satisfying arc that doesn’t exist in history or in life.

To do that involves not just deciding what to include, but what to exclude.

But how do you decide that? How do you know what timespan is going to work best for your memoir?

Before asking that, ask yourself this: Why are you writing this book? What are you trying to say? What is your point? Writers of both fiction and memoir use the particular to illuminate the universal. Underlying your experience is a message you want to convey, sometimes overt, sometimes subtle.

An example: You’re a cancer survivor. You could choose to focus on the period that led up to diagnosis and the choices you made, if you want to make the point that patients have autonomy over those decisions. Or you could choose to cover the treatment, and share your journey and the ways you found to manage the physical and emotional effects, to convey a message of hope and solidarity with other cancer patients.

A memoir that tries to cover the entire experience risks being unfocused and failing to make a point, which could leave a reader wondering why they spent all that time reading your book.

A historical novelist, similarly, might choose not to focus on the most well-known part of the historical figure’s life, instead opting to illuminate that person’s early journey, to show how circuitous and full of obstacles such a route to fame can be, or to foreground the contribution of a spouse, a parent, or a sibling.

Once you have a general idea of your timeline, you then have to decide on the exact moment your memoir begins and ends. The precise scene that gets the story underway for the reader, and the moment at which you have reached the end of that arc in a way that feels satisfying and connects back to the beginning.

I’ll use an example from my own work, The Portraitist: A Novel of Adelaïde Labille-Guiard. I chose as the starting moment the day my 18th-century artist first exhibits her work—and discovers her better-connected, more beautiful, and younger arch rival. The book ends at the only documented meeting between the two women at a dinner party in 1802. They have both changed by then, been tested by the events of the French Revolution and responded to them in different ways.

The plot thickensThe word “plot” comes freighted with associations for readers and writers. At its simplest, it’s what happens. Not just what happens, though, but why it happens. While there are plot-heavy narratives such as thrillers, mysteries, and romance, even the most literary of novels, or the most introspective of memoirs, has a plot on some level. Its inner logic is the same as any story, where scenes are linked by action > reaction > decision > consequence.

That means you have to excavate the choices you made and the actions you took, how you reacted to events and people, and the consequences you had to live with—and do it all in a way that has inner logic. Just narrating a chunk of your life can end up creating a memoir that feels episodic and static. You want your reader to keep asking, “What happens next?” to be compelled to keep reading.

Making that logic clear drives a reader through your story. As soon as you inject something arbitrary, something that is outside the logic that is heading toward your ultimate point, you risk losing the reader. It’s what happens in historical fiction when a writer falls in love with some fascinating tidbit from their research and puts it in even if it doesn’t serve the story.

The sticky thing in both cases is that you’re dealing with reality, with things that actually happened. While a historical novelist can take advantage of a gap in what’s known to invent something that will help their story work, that’s not possible for a memoirist. So what must you do?

It’s up to you to find the thread of the point as you sift through your memories, go back to journals from the time, perhaps talk to other people involved. It’s a process of selection, of editing out those events and experiences that, however interesting and important they are to you, are outside of the cause-effect trajectory of your plot.

You as protagonistYour story—and that of a historical novel—derives its momentum not only from the balance of scene and summary, but from the underlying emotions of the protagonist—and in memoir, that’s you. Your reader has to care about you, be on your side, just as they would any protagonist. And the only way to ensure that happens is to dig deep, to lay yourself open in all your emotional complexity, warts and all.

Here is where the historical novelist has a much easier task. We are digging for clues in our research, in letters and archives. What we don’t find we have license to create—as long as what we create fits with the story and character that exists.

For you, that digging can be uncomfortable and scary. But if you gloss over the deep emotions, your memoir risks not having the impact it could if you allow a reader to know your deepest feelings, the good and the bad.

Your memoir is a storyIn narrative memoir as in fiction, the principles that govern great storytelling apply. I have touched on only a few here. Your memoir requires world building, manipulation of point of view, compelling scenes, descriptions imbued with meaning, structure, and more. And it’s all wrapped up in revealing something not only about yourself, but about something bigger, something universal.

It’s a very tall order. But thinking like a novelist is one way to help you conquer the craft challenges of writing a great memoir.

March 22, 2023

Ask the Editor: How Can I Avoid Lawsuits When Writing Memoir?

Photo by EKATERINA BOLOVTSOVA

Photo by EKATERINA BOLOVTSOVAAsk the Editor is a column for your questions about the editing process and editors themselves. It also features first-page critiques. Want to be considered? Submit your question or submit your pages.

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Book Pipeline. The Book Pipeline Workshop—editors reviewing manuscripts, queries, and synopses. Fiction and nonfiction accepted. All material is considered for circulation to lit agents—multiple Book Pipeline authors have signed with reps and gotten published since 2020! Submit now.

Question

QuestionAfter more editing of my manuscript, I hope to self-publish my book based on my journey with bipolar II disorder. I have included people who came into and out of my life prior to my diagnosis and treatment for this mental illness. Short of changing the names, what actions should I apply to ensure that my truth, as written, will not bring about lawsuits against me?

—Legal Eagle Needed

AnswerDear Needing a Legal Eagle,

I’m so glad you asked this question! If the 2022 Johnny Depp and Amber Heard defamation trial taught us anything, it’s that you don’t have to name names to find yourself in legal trouble.

While getting sued for something in your memoir is exceptionally rare, it can happen. The risks are highest for authors with big platforms, especially if they’re writing about well-known public figures or powerful institutions. But even lesser-known authors can experience legal issues if they don’t perform their due diligence while writing and revising their books.

Of the things you can get sued for, libel is often the biggest potential problem for writers. Libel consists of false written statements, presented as fact, that do damage to the reputation of the person you’re writing about. If what you write is objectively true, the person who is suing is unlikely to win their case—but that doesn’t mean they won’t sue. Also, if you reveal embarrassing but true information about an individual who is not a public figure, you may get in trouble for invading privacy. (What defines a public versus private figure is complicated and may require legal consultation.)

Your question suggests you have some niggling concerns about how the people in your memoir might receive your story. In the land of storytelling, truth is far more malleable than you might realize—especially when writing early drafts. The goal of memoir isn’t to capture the capital T “Truth” of what happened; it’s to mine your experience for meaning that serves your readers and the story. To accomplish this goal, and have the best chance of staving off legal entanglements, there are two areas you’ll want to focus on: (1) researching your facts and (2) understanding your motives.

Researching the facts is about keeping your side of the street clean. You may need to interview witnesses, search through primary source material, read legal documents or medical records, and Google everything you can. Don’t assume your memory is correct; entertain the possibility that your memory may be faulty or incomplete. Look for evidence to support that things happened the way you remember them. If you can’t find evidence, or your memory is hazy, it’s best to admit this right in the story itself. E.g., “I don’t remember exactly how events unfolded that day, but…”

After you’ve checked your facts, consider how you’re portraying your characters. Dig deep and ask yourself if revenge fantasies or vendettas have impacted the way you’ve written about the people populating your book. Only angels are exempt from vendetta fantasies. Mere mortals are bound to our human experiences, which at times are filled with anger. Beta readers and writing group members can help you check for unfairness or imbalances in your character development. You can also do some perspective shifting by writing the same scene from your antagonist’s point of view. I know that’s a tall order, but it will help you better understand what happened, and write with compassion.

If someone has behaved so badly this feels impossible, and you’re certain they belong in your book, double check your research, then work with beta readers to ensure what you’ve written is accurate, balanced, and serves your story.

After you’ve completed your research and have a nearly final, polished draft, then you can think about whether to change names or descriptions. Changing names and identifying details, or creating composite characters, can be helpful if a situation belongs in your story but outing someone isn’t essential. Two memoirs that handle badly behaving characters with grace include Stephanie Foo’s What My Bones Know and Everything Is Perfect by Kate Nason. In Stephanie’s book, her insensitive boss is never identified, while Kate renamed a well-known public figure in her memoir. Yet we can make some educated guesses as to who they’re referring to, which means changing names isn’t a fool-proof shield you can rely on. If someone is in fact easily identified in your memoir, they can still sue successfully for libel or invasion of privacy even if you’ve changed their name and a few details.

If your characters aren’t public figures or affiliated with powerful institutions—and they’re not litigious—revising well and changing identifying features might be all you need to do to stave off a lawsuit. But, if chances for litigation are high, legal vetting might be in order. To legally vet a manuscript, you’ll hire a lawyer who will review your book, and to keep costs in line, it’s best to only submit chapters or passages of concern. A lawyer might suggest items for removal or help you rephrase things in ways that lower your overall risk. Costs vary from the hundreds to thousands of dollars. The Authors Guild has great resources around legal vetting, including this free webinar on vetting legal risk.

Checking all these boxes will certainly lower your risk, but there’s no guarantee you won’t be sued. That’s because we can’t always predict who will be upset. For example, Mary Karr feared her mother would have a meltdown when she read The Liar’s Club, but she loved it. Yet others have told me stories about characters they’d written glowingly about who were miffed by a single word used to describe them.

This might seem like a lot to consider, especially if your plan is to self-publish, but our stories are worth getting right. These suggestions will not only help you create the very best version of your memoir, they’ll help you promote your book with greater confidence, because you’ll know that everything belongs, has been written with care, and keeps your side of the street clean as you create your art.

I wish you the absolute best on your writing journey.

Warmly,

This month’s Ask the Editor is sponsored by Book Pipeline. The Book Pipeline Workshop—editors reviewing manuscripts, queries, and synopses. Fiction and nonfiction accepted. All material is considered for circulation to lit agents—multiple Book Pipeline authors have signed with reps and gotten published since 2020! Submit now.

March 21, 2023

Writing About Native Americans: 7 Questions Answered

Photo by Nik Shuliahin on Unsplash

Photo by Nik Shuliahin on UnsplashToday’s post is by author Sarah Elisabeth Sawyer.

Many authors want to write about Native Americans in their fiction and nonfiction, but they have questions about doing so—and don’t know who to ask. As a tribal member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, I’ve written and published 15 historical fiction books with Native main characters, and over 275 nonfiction articles on Native artists and organizations. In 2012, I was honored as a Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian Artist in Leadership fellow, and a First Peoples Fund Artist in Business Leadership fellow in 2015.

Helping authors of all genres write authentic stories with Native characters is one of my passions. Once authors invest in the skills they need, they’re able to stand behind every word they write. So I’ll answer frequently asked questions I hear from writers.

1. What is the correct way to refer to Native Americans?There are really long, complex answers to this, but I will give a short version here.

Many Natives in Indian Country still prefer the term “Indian,” but because it’s been used derogatorily for so long, you need to take great care if you use it.

“American Indians” is still commonly used, as in the National Museum of the American Indian.

“Native American” is fine as well, though technically anyone born in America is Native American.

My favorite term is “First Americans” and it’s gaining popularity. The Chickasaw Nation has adopted this as their term, and there is the First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City.