Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 74

March 1, 2021

Find the Ending Before You Return to the Beginning

Photo credit: nchenga on Visualhunt / CC BY-NC

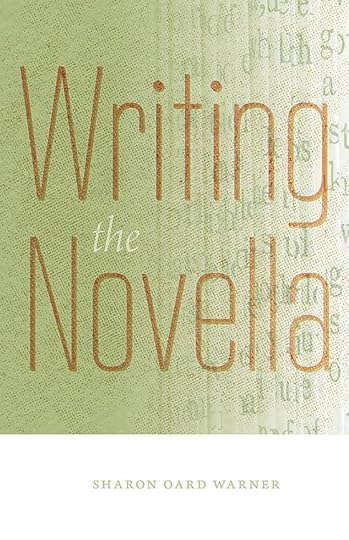

Photo credit: nchenga on Visualhunt / CC BY-NCToday’s post is adapted from the new book Writing the Novella by Sharon Oard Warner.

The first sentence can’t be written until the final sentence is written. —Joyce Carol Oates

When I taught my first graduate fiction workshop in 1994 at the University of New Mexico, I did as my teachers had done: I distributed a calendar, students signed up, and we agreed on a plan for distributing short stories or chapters from novels-in-progress.

A Scandinavian woman in her early seventies got us started with the opening chapter of her novel-in-progress. It introduced an immigrant family embarking on an ocean voyage to America. I made my comments then invited others to offer their perspectives.

After students began speaking, I realized some of them were already acquainted—with each other as well as the chapter under discussion. Later, the author told me that she presented Chapter One each time she started a new workshop, both to familiarize class members with the story and because she had yet to work out the kinks in her opening pages. Her goal, she told me after class, was to publish at least this one novel in her lifetime.

I don’t know whether my student ever finished her book and saw it to print because she was a community member, not someone working toward a degree. But, all these years later, I recognize that my class was more likely a hindrance than a help to her. I say this because I know now that chapters are a different animal than stories. Whereas short stories stand alone, chapters depend for their meaning on what comes before and after.

Like stones in a wall, chapters are parts of something larger, so assessing them in isolation is at best a waste of time and at worst injurious to the work as a whole.

Remember that great Robert Frost poem “Mending Wall”? In it, Frost describes the yearly task of repairing the wall, which amounts to restacking stones that have been dislodged. Some are “loaves” and some are “balls” and getting them to fit together and stay in place is difficult.

We have to use a spell to make them balance:

‘Stay where you are until our backs are turned!’

It’s a balancing act, with boulders and with chapters, and we can only judge them after we put them in place and stand back to see whether the fit is a good one.

The Going-Back-to-the Beginning SyndromeBecause we are anxious and insecure, we tell ourselves that a better beginning will give us the momentum we need to reach the end. But it won’t. It doesn’t. In her book The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master, Martha Alderson lays out the four challenges writers face when they sit down to write. The first one she lists is procrastination. The fourth is “The Going-Back-to-the-Beginning Syndrome.”

Alderson cites various reasons (read rationalizations) that writers use for going back to the beginning instead of proceeding into the messy middle (also known as the rising action) or sneaking up on the end. It’s comforting to return to the beginning, the status quo, when things weren’t falling apart. It’s harder to enter your house when you know the people inside are unhappy—liable to lose their tempers and throw things. Some of us are conflict averse, and what we have to learn is that we aren’t just conflict averse in our real lives. We are also conflict averse in our fiction.

Fight or FlightDuring the revision process of my first novel, my editor Carla Riccio made an interesting observation: Every time your characters get into an argument, one of them leaves the room. We were on the phone, and I burst out laughing because I recognized the problem immediately. Leaving is my first impulse in a situation I find uncomfortable: Hightail it. Make like a tree and leave. My husband the psychologist has nailed me on it countless times. Over the years, I have managed to better monitor and modify my behavior. That said, I had no idea the problem had followed me onto the page.

You probably recognize the term “fight or flight.” It refers to the physiological response we humans have to perceived threats, whether those be mastodons, marital muddles, or the messy middle of a manuscript. Regardless of the risk, some of us are more apt to fight than flee. Others, like me, want to run away, back to the safety of the beginning. Fleeing doesn’t solve anything. Don’t go back to the comfort of the beginning; stay in the messy middle and fight. (And let your characters duke it out, too.)

Taking a Better TripSo, why doesn’t a better beginning give you the momentum you need to sprint to the finish line? The answer is simply that the beginning is speculative. It’s a guess. Writing a book-length fiction is a long journey into the unknown and even if you do all sorts of advance planning, you cannot foresee all the adventures you have ahead of you. (If you could, taking the trip would not be all that much fun, now would it?)

Last May, my husband and I went on a highly anticipated trip to London. We prepared in all the usual ways, and by the time we packed our bags, we had checked weather forecasts, consulted guidebooks, and picked the brains of better-traveled friends. My husband went the extra mile. He watched YouTube videos by Gen-Xers who have already managed to travel the world and are now sharing their top ten lists: Things to bring, things to see, things to avoid.

Writing the beginning of your novel or novella is akin to packing your suitcase for an expensive and lengthy trip to a far-away place. You haven’t been there yet, so you don’t know for sure what you’ll need. When you get back, when you unpack, you will know, for instance, that the hiking boots (or the high heels) were just extra weight. You never got a chance to hike. The umbrella did come in handy and so did the granola bars, though you ate those in your hotel bed and not on a path along the white cliffs of Dover. The best-laid plans. The best-laid plans. Chant it to yourself whenever you imagine that repacking your suitcase is somehow going to make a difference in a trip you haven’t yet taken.

In RetrospectIf I could retrieve the many hours I spent rewriting the first chapter of my first novel, days, weeks, even months would be mine again. At this point in my writing life, I could and would use the time more profitably. Don’t get me wrong: I am all in favor of revision, both large-scale and small-scale revision. I’m also in favor of editing and proofreading. But the occasion for revising the first chapter is after you have written the last one.

Given what I’ve just admitted, it won’t surprise you to learn that the precious, carefully crafted first chapter of my first novel never reached print. My editor waited until the book was about to go to press before advising me to write a completely new first chapter. Having revised the whole book seven times and the first chapter dozens of times, I threw it away and very quickly wrote something entirely new and much better. It stands to reason. All these years later, I knew the story—and the characters. I also knew precisely how the novel ended and, therefore, at long last, how it began.

Note from Jane: if you enjoyed this post, check out Sharon’s new book Writing the Novella.

February 23, 2021

Backstory and Exposition: 4 Key Tactics

Today’s post is by regular contributor Susan DeFreitas (@manzanitafire), an award-winning author, editor, and book coach. She offers a first 50-page review on works in progress for novelists seeking direction on their next step toward publishing.

Landing your novel opening can be tricky. On the one hand, you need to get the reader sucked into the present moment of the story as it’s unfolding; on the other hand, there’s a lot you need to explain about the past, which is precisely the sort of thing that puts readers to sleep.

This info is generally known as backstory (essential information about the characters’ past) and exposition (essential information about the context of the story). Getting it right is one of the biggest challenges you’ll face with your novel.

When the backstory and exposition is excessive, unnecessary, or too obvious, it makes the reader feel like they’ve been hit over the head, hence the term info dump. Examples of info dumps include the sci-fi novel with paragraphs upon paragraphs on the history of faster-than-light travel in the Goltoggan system, or the literary novel that includes so much complicated backstory on the protagonist’s upbringing that not much happens in the present moment.

But when the backstory and exposition aren’t included at all, or are included too sparingly, the reader tends to (in the words of one of my mentors) “bump into the furniture”: Who are these people? Why are they fighting? Why is this fight such a big deal for this one character in particular? And how exactly is it that her skin is now throwing off purple sparks?

Some writers include less in the way of backstory and exposition, while some writers go for more—a key stylistic choice. But one way or another, if the info is essential to the reader’s understanding of the story, that info must be included. What follows are four key tactics for doing so in a way that won’t lose your reader.

1. That old (effective) rule: Show, don’t tell.Next time you see a movie, pay attention to the opening scenes: in many cases, these scenes look like they’re the opening of the actual story, but in reality, they’re just there to establish the ground situation, what life is like for the protagonist before the story really starts.

This technique can work well in fiction too, and in many cases it saves you from having to come right out and explain things. This is such an elegant trick that it has its own tagline: “show, don’t tell.” If you plunk your reader down in the middle of a scene at the opening of your novel, you can use that scene to establish backstory and exposition invisibly, via context, dialogue, and specific details.

Flashbacks can serve this purpose as well: they convey backstory and exposition in a way that’s largely invisible. Rather than feeling like the author is explaining things to us, as readers we’re figuring it out for ourselves.

If you struggle with how to reveal the key bits of backstory and exposition in your novel, the simplest trick is to start earlier in the timeframe of the story, and include an opening scene that establishes the ground situation—and, if necessary, use a flashback as well.

2. Show, then tell.The elegant technique of “show, don’t tell” doesn’t work for all novels, especially speculative ones—or at least it doesn’t work on its own. “Show, don’t tell” is predicated on the reader being able to infer key details about the characters and their world based on their own experience and common knowledge. In speculative stories, that technique tends to break down at some point, because they take place in worlds that differ from our own.

Luckily, there’s an adjacent tactic: “Show then tell.”

For instance, in the example offered above, in which two people are fighting and the epidermis of one of them begins to throw off purple sparks: After a scene like that, your reader won’t find it annoying if you step in with some basic background on this character and her unique relationship to the electromagnetic field, because by doing so, you’ll be answering the reader’s questions rather than hitting them over the head with (what feels like) a whole lot of random info.

If you find yourself struggling with how to convey a complicated bit of backstory or exposition in your novel, see if you can come up with an opening scene that raises serious questions—precisely the questions you want to answer.

3. Present backstory as story.Is your protagonist’s backstory…a long story? Pretty complicated? And is it absolutely necessary to the story you’re trying to tell? Consider making the backstory a story in and of itself.

For instance, if your novel opens with a character on an epic cross-country road trip, you might start the backstory in Chapter One with how she lost a bet with her bestie and therefore had to go confront an old friend of theirs who’s not returning phone calls. From there, each subsequent chapter, while continuing to roll forward in the present moment, might also pick up the thread of the backstory on that road trip, until you’ve caught up with the story in the present.

Or you might share the protagonist’s backstory the way you would an actual story, with an opening chapter that reads like the story of their life. That’s a riskier technique, largely reliant on the storyteller’s voice, but for the right book, it can work well. For instance, this is what John Irving does in the opening chapter of The Cider House Rules, “The Boy Who Belonged to St. Cloud’s”; Elizabeth’s Gilbert’s The Signature of All Things also begins this way, with the line “Alma Whittaker, born with the century, slid into our world on the fifth of January, 1800.”

4. Use backstory as the reveal.Finally, there’s the trickiest technique of all: Withholding the essential backstory and raising questions about it throughout the story, so that a revelation about the protagonist’s past is given the emotional weight of a secret revealed.

This is essentially what Stephen Chbosky does in The Perks of Being a Wallflower: We know that something in Charlie’s past has led him to retreat into himself and away from others. We know too that he attributes this to the death of a beloved aunt when he was younger—but that explanation doesn’t quite make sense, because his reaction seems disproportionate. Later on, at the story’s climax, we discover that he’s repressed his memories of this aunt having molested him, and that’s the real reason he became so withdrawn.

With this technique, the key is to make sure the story raises questions early on about what happened in the past, then offer clues and hints at regular intervals leading up to the big reveal. It’s a technique that works well when you have a novel that’s in some significant way about the impact of the past on the present, or about how we deal with the aftermath of life’s various traumas—especially when you want to do that without coming off as melodramatic or overstated. By “hiding” the past, you make the reader want to explore it.

This post of mine is the result of many years of wrestling with this issue, both in my own work and that of my clients, so I’d love to know: What have you wrestled with in your own work, in terms of backstory and exposition? And what techniques have you found most helpful?

February 10, 2021

Fix Your Scene Shapes to Quickly Improve Your Manuscript

Photo by Sharon McCutcheon from Pexels

Photo by Sharon McCutcheon from PexelsToday’s guest post is by writer, coach and editor Lisa Cooper Ellison (@lisaellisonspen). On Feb. 24, she’ll teach an online class called Heartbeats: Using a scene’s emotional rhythm to build momentum and captivate readers and agents, in partnership with Creative Nonfiction Magazine.

In your final manuscript, every scene should contain a conflict that’s essential to your narrative arc, something that simultaneously captivates the reader and catapults your story forward.

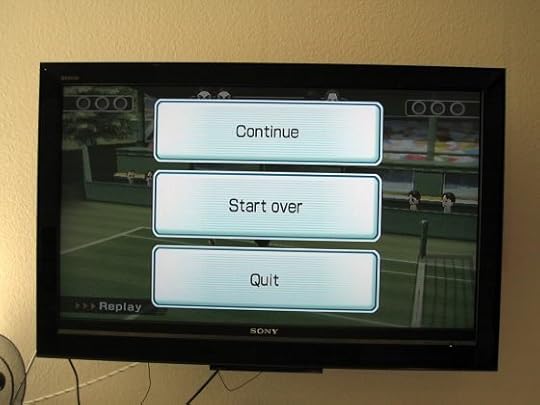

Last week, J.D. Lasica wrote a post on how AI has identified seven universal story shapes. Like stories, scenes also have a shape. Some work well, while others fall flat. But before we examine these shapes, let’s talk about a few important concepts.

When you spend a lot of time on something in your story, you’re saying, “Hey reader, this is super important, so pay close attention to these details.” In other words, you’re giving this part of your story some weight or importance.In an effective scene, your main character has a conflict that peaks in one dramatic moment. That moment is the beating heart of your scene or your emotional beat. Beats have three jobs: resolve the scene’s conflict, reveal your main character’s decision, and propel your story forward. Because beats carry such a heavy load, most of your scene should focus on this moment.Now, let’s talk shapes.

We’ll start with the exemplar.

The Pear

A pear-shaped scene contains a lean entrance followed by some interconnected actions that build to an emotional beat. Once there, the storytelling slows down while the tension rises until we reach a pivotal moment when the main character makes a choice. Sometimes it’s an internal choice only known to the narrator. Other times, it’s an external choice that’s revealed through action or dialogue. When we reach that final riveting moment that resolves the scene’s conflict and sets up future problems, the scene ends.

Books filled with pear-shaped scenes tend to be page-turners that have cinematic appeal, such as Catching Fire from Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games series, Cheryl Strayed’s Wild, and Alexandria Marzano-Lesnevich’s The Fact of a Body. Wild and Catching Fire have been made into movies. HBO is currently adapting The Fact of a Body for television.

Now, let’s talk about some scene shapes that require revision.

The Funnel

The problem: In funnel-shaped scenes, the weight is in the setup. The beginning is filled with rich setting- or character-developing details that evoke a certain mood. There might be a panoramic exploration of the landscape. We might learn a lot about what your character looks like and how he or she behaves before anything happens. Sometimes these scenes lack a clear conflict, or the conflict is outshined by the lengthy opening. When we get to the beat those details that were painstakingly developed are barely mentioned.

The fix: Before you write, identify your scene’s key conflict and the moment when it comes to a head. Consider what choice your main character will make—and it doesn’t have to be grandiose. For example, they could simply fail to respond to some dialogue, because lack of response is a response in storytelling. Then, choose a few select details that will establish your setting. Make sure one of them can do some work in your emotional beat.

As you write, craft a slimmer beginning that quickly gets to the action, then slow down when you reach your emotional beat. Make use of those careful setting details. Once the conflict has been resolved, exit stage left.

The Wind Tunnel and The Watermelon The Wind Tunnel

The Wind Tunnel The Watermelon

The WatermelonThe problem: Wind Tunnels happen in both high- and low-intensity scenes when we breeze through the action without landing on an emotional beat. We know we’re in a wind tunnel when we have a lot of action that follows an “and then, and then” format.

Watermelons are the Wind Tunnel’s large, heavy cousins. Watermelons are high-drama scenes where readers are blasted with actions and events that upset and jar them. There’s no time to rest and nowhere to focus our attention.

Watermelon-shaped scenes are common in memoir drafts when the narrator has gone through something truly awful. Often, they are start-to-finish renderings of a traumatic event where the narrator is powerless and victimized. Because things happen to the narrator, there’s no focal point and no decisions are made. We know we’ve encountered a watermelon when we’re upset and maybe even outraged by what we’ve read, but we don’t know what to do with the scene’s information.

The fix: Identify your pivotal moment and slowly render it. Remember, the pivotal moment is the point where the main character makes a decision. So, even if a lot is happening to your main character, give them some agency.

If you’re wondering how to manage a beat in a high-intensity scene, watch some battle or chase sequences from your favorite movie. You’ll notice there are times when we’re in the fray but, eventually, the action slows down so we can focus on two or three main characters. During these beats, the larger battle fades into the background as we zero in on a pivotal showdown.

The Kite

The problem: You’ve entered late, kept the beginning slim, and rocked your emotional beat. But, when the moment is over, you keep going. Maybe you process the experience through your main character’s internal dialogue or you go on to some new, less important moments. In memoir, you might reflect on what’s just happened. Often, the writer’s goal is to make sure the reader understands the point they’re trying to make. But, like the tail on a kite, the information just hangs there, lowering your dramatic tension.

The Fix: Find your beat, land on that moment, and like the director boss that you are, yell, “Cut!” Scrap anything after the beat that doesn’t propel your story forward. Trust the reader to intuit your intended meaning. If you’re not sure whether your point has been made, send the piece off for feedback sans the extra material. Ask your critique partner to summarize the point of your scene. Compare their summary to your answer. If it generally matches up, yay! If it doesn’t, tell your critique partner what you’re trying to accomplish and see if they can help you brainstorm ways to make the point clearer through action or dialogue.

Your AssignmentChoose a scene that doesn’t seem to be working. If you’ve recently worked on the scene, move on to the next part of the activity. Otherwise, read it quickly without making any changes.

Identify the part of your scene that has the most weight or importance. Remember, the weight in your scene is where you spend the most time. Then draw your scene’s shape.

Now, ask yourself the following questions:

Is your beginning skinny and quick or do you spend a lot of time describing your surroundings?Is your middle fat with high drama, or do you move from one interconnected event to the next in a slim, trim fashion?Do you land on an important moment and then slow down?Does your resolution plant the seeds for future problems?Once the drama has been resolved, do you get the hell out of there or do you hang around?Once you have your answers, go back and rewrite the scenes that will captivate your readers.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, consider joining Lisa on Feb. 24 for the online class Heartbeats: Using a scene’s emotional rhythm to build momentum and captivate readers and agents (in partnership with Creative Nonfiction Magazine).

February 9, 2021

Get Reader Reviews Now to Drive Sales Later

Photo credit: natlas on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-ND

Photo credit: natlas on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-NDToday’s guest post is by author and publisher Mike O’Mary (@Lit_Nuts).

I was recently on a video conference with members of the Independent Book Publishers Association (IBPA). We were talking about “discovery”—aka, how do small publishers (and independent authors, for that matter) let book lovers know about all their great new books?

I currently publish a book promotion newsletter, but prior to that, I ran a small press for several years. On average, we sold 6,000 copies of each book we published, including two that sold more than 20,000 copies, all without traditional distribution and on a tight budget. One of the critical pieces of our strategy: securing reviews so we could do serious advertising later.

But before I get to that: Make sure you have a great book. I know it goes without saying, but don’t expect to sell 5,000 copies of a mediocre book. The steps that follow will get your book into the hands of thousands of readers. If they like your book, you’ll get lots of positive reader reviews, good word-of-mouth, and thousands more readers. If they don’t like your book, you’ll get negative reader reviews and bad word of mouth. Enough said.

Okay, so first you need to get reader reviews on Amazon, BN.com (Barnes & Noble), Goodreads and elsewhere—but especially on Amazon and Goodreads. Here’s how to do that.

Goodreads giveawayConsider doing a giveaway on Goodreads. I know, the idea of “giving away” your book may not sit well with you—especially when I tell you that it currently costs $119 to give your book away via Goodreads. But it’s worth it. You can give away up to 100 free copies of the Kindle edition of your book. Goodreads will handle fulfillment for you. In return, you get your book into the hands of dozens of engaged readers (and on the “Want-to-Read” lists of everybody who expresses an interest in your book), which will very likely lead to reader reviews on Goodreads and/or Amazon or elsewhere. You also get to send a follow-up/thank-you message to everyone who expressed an interest in your book during the giveaway, which is usually hundreds or even thousands of people.

That said, be realistic about your expectations: most of the people who express an interest in the giveaway (and many of the people who actually receive a copy of your book as a result of the giveaway) will not post a review. But many will. If you give away 100 free copies on Goodreads, it’s fair to expect 20–30% of recipients will post reader reviews in the ensuing days/weeks. That’s not a bad return on investment.

Blog tourA blog tour is a great way to promote not just your book, but also yourself as an author. I’ve used several blog tour services, and I can recommend a WOW! blog tour or a TLC Book Tour as effective marketing tools.

Blog tour organizers like to engage readers via eligibility for a drawing (i.e., “leave a comment and be eligible for a drawing for an iPad”), and that’s fine—but your goal is not to get as many people as possible to enter a drawing; your goal is to get your book into the hands of readers. So work with your tour organizer to be sure the host of each blog will be giving away at least a few review copies (preferably digital copies) of your book to their followers with the expectation that recipients will post a reader review online. I also recommend asking your tour organizer to let you review the proposed list of blog tour participants. I always research each proposed participant myself to make sure it’s a good fit—and to make sure they are active bloggers with a decent following.

Another option is to organize your own blog tour. There’s a good list of book review blogs on Reedsy. You can always submit your book for review—but you can also offer to do guest posts. Your proposed post could be simply about your book or about yourself as an author, but a unique angle (an interesting discovery you made while researching/writing your book? practical advice based on the content of your book?) is preferable. Whatever you write about, be sure to think in terms of providing readers with something of value—including the opportunity for some of them to receive a free review copy of your book.

Advertise via email newslettersI’m a big believer in book promotion newsletters. I used them extensively when I was running an indie press, and I now publish one. Newsletters are an economical way for authors to get their books in front of thousands of readers. But with 100+ newsletters out there, you need to know which ones to use. You can read my previous post about Using Book Promotion Newsletters to Increase Sales for advice on how to get the most out of this marketing channel.

Ideally, book promotion newsletters will generate enough sales to at least pay for themselves. But even if you just break even, that’s good! The primary goal through all of this is to get your book into the hands of readers, and to get some reader reviews on Amazon, Goodreads and elsewhere.

KDP Select GiveawayAnother way to get copies of your book out there for reader reviews is through a KDP Select giveaway. To enroll in the program, you need to halt sale of your ebook edition everywhere other than Amazon for 90 days, which is a bit of a hassle (and maybe impossible if your book was published and distributed by a traditional publisher and distributor). But if you worked with a small publisher or self-published, KDP Select may be an option for you.

My small publishing company did not have traditional distribution, so I controlled distribution and pricing myself. So to enroll in KDP Select, I temporarily turned off ebook sales via BN.com and Smashwords (which in turn, turned off sales via Apple, Kobo, and others), and then turned sales back on when I took the ebook out of KDP Select.

While you are in the KDP Select program, your ebook will be available to people who have paid for Kindle Unlimited (they can borrow your book at no cost, and Amazon pays you per page read), and you can give away your ebook for up to five days during your 90-day enrollment. I would give it away for three days early in the 90-day period, and then use the other two days late in the 90-day period. The result will be lots of free downloads, and ideally, a “tail” of paid sales when your Kindle ebook goes from free back to regular price.

Also, I advise promoting the heck out of your KDP Select giveaway. There are a bunch of websites and email newsletters where you can promote a giveaway at no cost or low cost (again, see my previous post on book promotion newsletters). A good giveaway will result in thousands (maybe tens of thousands) of downloads—and ideally, lots more reader reviews and word-of-mouth marketing that you wouldn’t get otherwise.

After your enrollment in the KDP Select Program expires (be sure to set it up so it doesn’t renew automatically), you can turn distribution back on at other retail outlets.

Parting adviceUsing these tactics, your ebook should be in the hands of thousands (if not tens of thousands) of readers, many of whom got your book for free, but also many of whom paid to buy your book. You should also have lots of reader reviews and positive word of mouth, which will help drive and sustain your sales going forward while also giving you the opportunity to do additional marketing based on the strength of your reviews. If so, kudos to you. It’s a lot of work, but it’s all doable. Good luck!

Note from Jane: LitNuts has two offers through March 31. (1) Get a book promotion for $10 using discount code BookPromo10. (2) Schedule a book promotion at the regular price of $25 for a 99-cent Kindle ebook, and LitNuts will buy five copies to use as welcome gifts for new subscribers—and encourage them to post reader reviews online.

February 8, 2021

Building Your Writing Support Triangle

Photo credit: Ken Mattison on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-ND

Photo credit: Ken Mattison on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-NDToday’s post is by author, editor and coach Jessica Conoley (@jaconoley).

Every writer I know who has lasted in the publishing industry for more than five years has one thing in common: a support system that functions on multiple levels. Everything about this industry—querying agents, sending stories out on submission, the erratic way in which we get paid, etc.—is designed to weed writers out and wear us down. But those of us with multi-level support are more likely to weather the storms of self-doubt.

There are three key types of support for writers:

Mentorship: People ahead of you in their career who inspire you.Critique: People who offer feedback on your writing in exchange for your feedback on theirs.Accountability: People who help keep you on track for your writing and career goals.The key to emotional well-being and continued productivity is knowing which part of your support system to call on and when. Once you start looking you can find support everywhere: from writers and non-writers, people you may never meet in real life, or authors who don’t even know you exist.

If you are lacking in motivation and inspiration, invest some time in finding your mentors.After you’ve refined your story to the best of your ability, and a fresh set of eyes would give you some perspective, reach out to your critique partners.If you find it difficult to carve out time to write, lean into the accountability side of your support system.Mentorship: Three LevelsAre you looking for motivation and inspiration? Find yourself a writing mentor. The great part is you don’t even have to be able to access that person in real life.

I have mentors on three levels.

1. Rockstar TitansThese are writers like Neil Gaiman, V.E. Schwab, and Stephen King. These mentors from afar are the authors with million-dollar book deals and fans who tattoo their quotes onto their flesh. If I were fortunate enough to be in the same room with a Titan, I likely wouldn’t be able to speak to them out loud with my words, because OMG “It’s you.”

Luckily these seemingly inaccessible mentors have:

Books you can read and study. How they execute their craft teaches me how to refine mine.Most Titans offer videos on YouTube, speeches, lectures, interviews, and book launches. Snippets of relevant wisdom find their way to me with each viewing.Social media you can engage with. How they interact with their readers and promote their work can serve as a blueprint for my own online presence. Sometimes they do something I don’t like, which teaches me as well.Rockstar Titans have done the impossible—which means it’s possible. And one day, if I finish the draft of this damn book, and the one after that, and the one after that, maybe, just maybe that could be me.

2. Writing GeniusesThese are authors five to ten years ahead of me in their careers. And yes, they’ve amassed awards and published multiple books, but they still walk the same streets as mere mortal me. If I encounter a Writing Genius in real life I could probably muster the courage to talk to them.

Writing Geniuses are still building their platforms, which means they actively engage with their audiences. Luckily, I am their audience.

Retweets, shares, and comments on a Writing Genius’s social media gets your name (and avatar) in front of their eyeballs. After years of my retweeting and positively commenting on a Writing Genius’s posts, she followed me back! More importantly, when I had a technical question on a project, I tweeted her for advice and she responded.Subscribing to a Writing Genius’s email newsletter puts you in direct contact with the author. Unlike social media, where algorithms can filter or bury the authors insights, a newsletter is delivered to your inbox. This direct connection ensures you don’t miss out on the important wisdom the Writing Genius is willing to share. Reading the emails keeps you up to date on what the author is doing. Replies to their newsletter with a short thank you and information about what you found helpful in the article lets the Writing Genius know their work is appreciated. Remember you’re not entitled to a response to an email. Mentors are busy and guarding their time—which is a great lesson in how you may need to employ boundaries with your time. Regardless if they write back or not, it’s good literary citizenship to tell other authors when their work has positively impacted you.Membership to a Writing Genius’s Patreon shows them you are long-term invested in their success, and therefore they are more likely to engage with you. One of the authors I support on Patreon offers monthly virtual classes and work sessions to her patrons. Initially I was too shy to ever speak up in the Q&A sessions, but over time I got more comfortable and learned to ask her for advice.Writing Geniuses have shown me how to navigate the tricky higher levels of this industry, and I owe them a thank you—so when I meet them in the flesh I will muster the courage to let them know how grateful I’ve been for their guidance.

3. Working Role ModelsThese are authors I have face-to-face access to. Often these mentors took it upon themselves to encourage my growth out of sheer generosity and good literary citizenship. They have read my work. They have seen my potential and encouraged me to try new things. They send opportunities my way because they believe in me.

It takes courage to approach someone and ask if they would be willing to help with a few questions regarding our career. You should applaud yourself for reaching out. But, if they say no, or don’t respond to your email, remember they just mentored you. They showed you the most important writer lesson of all: our time is precious, and we cannot say yes to every request and/or opportunity that comes our way.

If they say yes, be respectful of the irreplaceable time they are investing in you. Be prepared. Have questions laid out that you think they can help with. Show them the work you have done to get where you are and let them know where you want to head next. Then, sit back and listen. Listen with your whole body, down to the marrow of your bones. Hear what they’re saying and what they aren’t saying. Ask clarifying questions and delve deep whenever you can.

Working Role Models are two steps ahead of me in their career, but if I work hard we might become colleagues. Maybe one day I will send opportunities to them, the way they have so generously sent them to me.

If it’s time for you to find a mentor, who do you admire? What avenues to you have to connect with them? If you’re unable to connect with them, what are three ways you can learn from them right now without one-on-one access?

Critique: Three TypesEvery writer reaches a point when they can no longer be objective about their own work. Even worse, you can’t figure out what the hell you’re writing in the first place, and, oops, you’re 50,000 words in, but damn that last sentence was fire. You need a fresh set of eyes attached to someone else’s brain. I typically know I’ve hit this wall when I’m moving the same sentence to four different places in a manuscript, deleting it, reinserting it, and then adding a comma because surely that’s going to solve the problem. If you’re tinkering with no progress, call in your critique support.

1. Critique GroupsTo refine your writing, gather a small group of writers who exchange work according to preset rules and time frames. The group format lets you see a variety of reactions to your work, and triangulate information to see what you need to fix. If four out of the five of members of the group say, “I was confused and had no idea what happened in this scene,” you know you have a serious problem. If two of the members get in a huge fight about which one of your characters is the worst, fantastic—you’ve written something that invoked passion in others. If one person hates something, well that’s interesting and helpful feedback, but maybe it’s more about their personal preference than your writing. The added bonus: a critique group will help you develop a thicker skin, which will come in real handy when those reviews start going up at Goodreads.

2. Critique PartnersA good critique partner is worth their weight in gold because they’re willing to read the same chapter again, and again, and again. This is the writer you swap work with on a regular basis and provide reciprocal critiques. It’s helpful to ask for the type of critique you need, depending on the stage of your project.

Big picture edits to check for pacing problems, voice consistency, or other over arcing issues.Line edits when you’re tightening, refining voice, clarifying action, working on visualization, etc.Copy edits to check for grammar, consistency, and formatting issues before you send out for potential publication.Positivity Passes when you need to hear what you’re doing well. The positivity pass is often overlooked and highly underrated. Ask for this type of feedback when you feel like “My writing sucks.” And questioning, “Why am I even doing this?” A PP helps provide some much-needed validation and surely if your CP can find something nice to say about the work you won’t have to throw the whole thing in the garbage.3. Beta ReadersBeta readers are as close to a reader shopping a bookstore as you can get. These are one-time readers who give initial impressions on how your story is coming across. The super fantastic thing: Beta readers don’t have to be writers. They just have to be readers whose opinions you trust.

However, if you’re asking someone to read a full manuscript, that’s a huge time commitment. First, ask if they would read the first ten pages for you. If they’re into your story, then offer to let them read the whole manuscript. If they’re not into the story, it gives them a graceful out. As with your critique group, look for those places where multiple readers comment. This means you’re either doing something really right or really wrong.

Critique lets you see your work (more) objectively. It lets you know your strengths as a writer and points out places where you could spend a little more time revising. If you get your critiques and realize you are great at description, but your dialogue could use work, consider a class to help refine your skills.

Remember: Critiques are other people’s opinions. It is your story, so disregard the feedback that is irrelevant to your vision. Incorporate and revise based upon the feedback that hit home.

Critique support often turns into emotional support as well. Writing is a weird industry and only another writer is going to understand the sting of a query rejection or why it takes four years for your book to get to print. That emotional support has kept me from walking away from this industry more than once, and it all started with swapping some pages.

Accountability: Three StepsOne of the most challenging parts of being a writer is sitting our butts in the chair: getting in the day’s words, or edits, or marketing. For some reason I’ve never been more willing to clean out my fridge than when I have to write a difficult scene. Balancing all of the responsibilities of life, plus our ambitions as a writer, can feel impossible. Especially if we don’t have a deadline looming or the fear of breach of contract to motivate us. If you find yourself doing everything but writing lately it’s time to lean on the accountability leg of your support triangle.

Accountability is tricky. You have to dig into your personal motivations and fear. Once you understand your motivations it is a lot easier to find the right accountability tools. I recommend trying any and everything until one sticks.

If you are concerned with what people think about you, consider a public commitment.Declare “I am a writer.” Publicly. This creates psychological ownership of your writing aspirations. People will ask you what you write, and avoiding the awkward, “Ummmm, nothing right now…” is great motivation to keep you writing. I am a writer is a terrifying declaration to make the first time, but if you tell the Uber driver you’re never going to see again, it feels like there’s less at stake. Work up to telling your friends and family after practicing on a few strangers.Create a newsletter. Decide how often you are going to send out the newsletter, tell people you’re trying an experiment for three months and would they please sign up. Stick to it for one quarter. Knowing your readers are expecting you in their inbox will keep you hitting send. After three months, if you’ve enjoyed the experience, keep going. With newsletters there’s an added bonus. You’re creating a direct link to readers, which translates to building your platform, and publishers love to hear you have a platform when you’re shopping that manuscript or book proposal.Post on social media every business day for a month about your daily writing goal. The internet is always watching. Someone will be inspired by you following your dream. Someone is counting on you to succeed in your writing, because if you can do it, then maybe they can too. You may never know who that someone is, because your followers aren’t always brave enough to reach out and say how you’ve inspired them. But someday, you’ll be signing books, and a random stranger will say, “I saw your daily writing posts, and it made me want to write. I just finished my first short story.”If you hate wasting money, consider a financial commitment.Pay to join a class, workshop, or Patreon offered by a writer you admire. You can find writing courses taught by Rockstar Titans, Writing Geniuses, and Working Role Models. Classes teach you how to refine your craft. Workshops provide the opportunity for feedback on your work. Patreon subscriptions let you see behind the scenes and get you a step closer to your mentor. They also offer the opportunity to build your writing community. Surrounding yourself with like-minded writers committed to finishing their work is always beneficial, and these new acquaintances may end up being good accountability partners.Invest in an editor/coach/therapist. Editors know industry trends and can dissect books in a way your average critique partner isn’t able to. An edit letter gives you a jumping off point on how to move your project forward, and it’s always easier to make progress when we have a road map. A book coach provides accountability and moral support. You may be surprised how much more progress you make when someone is reading over your shoulder. A therapist can help dig into those mindset issues that are holding you back from finishing your manuscript. Maybe you thought your problem was a lack of craft or experience, but when talking through your challenges with a therapist you realize the real issue is your fear of success.Reward yourself when you meet your goal. If your goal is to write every day for one month, go to the bank and take out thirty dollars in $1 bills. Every day you write, add $1 to a jar. At the end of thirty days take the money out of the jar and treat yourself. Want to make the stakes even higher? If you miss a day, take all the cash out of the jar and start over, from zero, on your next writing day. I do a variation of this quarterly, and have ended up with some pretty snazzy treats, like a beautiful Retro Classic Bluetooth keyboard.If you hate to let other people down, consider a one-on-one commitment.Find yourself an accountability partner—an acquaintance whose opinion you value, who is also working toward a goal. Your AP doesn’t have to be a writer, and they don’t have to have the same goal as you. Texting each other daily updates on your individual progress is great motivation. My AP and I have a two-texts-a-day routine. We start our working day with texts of our goals for the workday, and finish with a sum up of what we accomplished. My AP says, “It feels like clocking in and out of work, but in a good way.”Swap work with a critique partner. CPs are writers you exchange work with and provide feedback for, on a regular basis. Ideally you will find someone at a similar level in their writing career. Agree on a page count, deadline, and frequency of work exchanges. (I swap with mine weekly.)Schedule a co-working session. Meeting a friend at the library to do your homework has evolved in the digital era. Now we can co-work with friends halfway around the world via Zoom or Microsoft Teams. There are even apps that will link you up with total strangers to co-work. I run co-working sessions three times a week, for two hours each session. We chat for fifteen minutes, work for forty-five, chat for fifteen, and work for forty-five. Looking at all the Zoom boxes and knowing other people are working as well is motivating. An added bonus for people with chaotic households is you can say, “I have a meeting.” Your family will leave you alone for two hours while you get your words in for the day. Co-working sessions can be a great gateway for people who are transitioning from corporate/work environments with a lot of inherent structure to a free-form/self-motivated work environment.It took me ten years and a lot of experimentation to find the right mix of support, but once I understood my motivations, I was able to hone the tools that worked. If you want to dig into your motivation, Gretchen Rubin’s four tendencies quiz is a good place to start. The quiz is quick and lets you know if you’re the type who needs internal or external accountability. So, the next time you’re tempted to binge Netflix, because it feels too hard to sit your butt in the chair, reach out to your accountability support system.

With a strong writing support triangle, you can move your career forward as you deepen relationships and help others. Taking time to build your support triangle now will give you a strong foundation that keeps you in this industry for decades.

P.S. If you need help building your support system, you’re welcome to try a co-working session with me and my patrons. Reach out to me on Twitter (@jaconoley) and I’ll get you the details.

February 2, 2021

Do Stories Have a Universal Shape?

Today’s post is by author J.D. Lasica (@jdlasica). Disclosure: Lasica serves as editor in chief of BingeBooks, a sister site to Authors A.I., which has provided the underlying data for this piece.

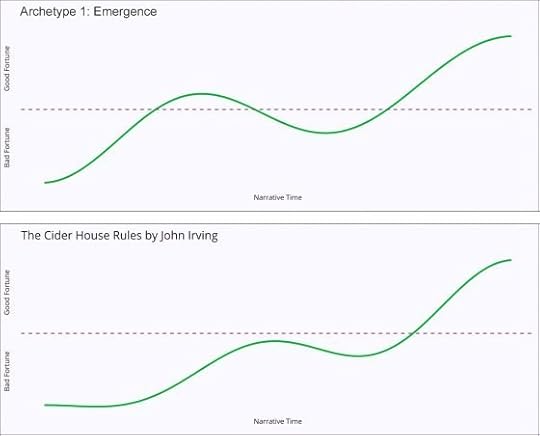

Do most novels share certain storytelling patterns? More than three decades ago, Kurt Vonnegut toyed with the idea that stories have universal shapes. He suggested that, with few exceptions, the stories of classic and modern literature can be grouped into a handful of archetypes.

And now, a new artificial intelligence that analyzes long-form fiction has validated Vonnegut’s theory.

The idea of universal story archetypes is not a new one—but its corroboration by an A.I. brings a new dimension to the debate. Can most popular fiction really be grouped into these rough frameworks or buckets?

As authors, we have a natural tendency to rebel at the idea that our stories can be pigeonholed or typecast. We resist the notion that our heartbreaking works of staggering genius can be considered anything but wholly original.

But that misses the point of archetypes.

Let’s begin by exploring Vonnegut’s thesis—and, quite literally, it was a master’s thesis that Vonnegut proposed to write while studying at the University of Chicago. He argued that classic stories from popular culture through the ages had predictable plot arcs that could be graphed on a piece of paper, on a blackboard or by a computer. The faculty committee rejected the proposed thesis, and Vonnegut would not earn a degree until years later when Chicago awarded him a master of arts degree based on his masterful work Cat’s Cradle.

Vonnegut kept returning to his idea about story shapes throughout his career. He built a lecture around the theory and took it on the road. In his inimitable way, Vonnegut delighted a student audience in a 1985 lecture captured on video that made its way onto YouTube decades later:

Stories have very simple shapes that computers can understand, he argued, adding dryly, “I have tried to bring scientific thinking to literary criticism, and there’s been very little gratitude for this.”

In his writings and lectures, Vonnegut observed that a graph of a story could be charted along a vertical axis. Scenes that evoke good fortune, health and happiness go at the top while events that result in death, disease, poverty or other ill fortune fall below the median line. The horizontal axis denotes narrative time, from the beginning to end of the story. As the plot drives forward, the threads of a story typically take us on a journey through crises, complications, dramatic turns and resolutions.

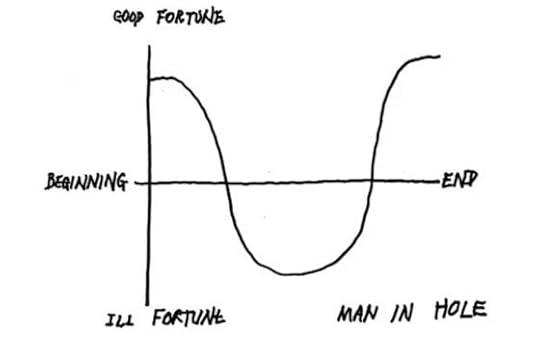

Over time, Vonnegut developed a theory of eight universal story shapes. As he doodled, he often liked to scribble plot shapes. Here are two drawings he made of two of his favorite archetypes, which he called Man in Hole and Boy Meets Girl.

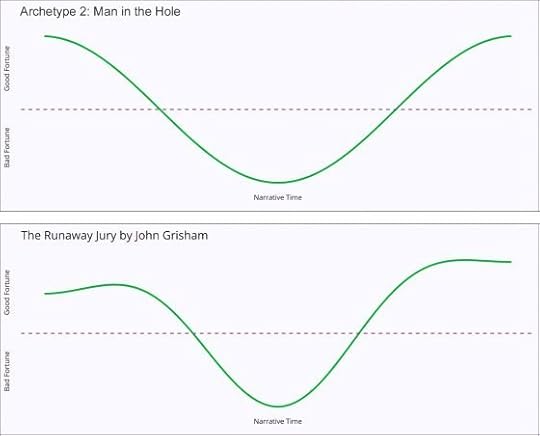

Fast forward three decades. The video of Vonnegut talking about his theory of story shapes caught the eye of scholar and data scientist Matthew Jockers, author of two books on text mining. Jockers went on to write The Bestseller Code (co-authored by Jodie Archer) with the goal of identifying the features that propel a book to the bestseller lists. Based on his research, he wrote an algorithm that was able to predict with 83% accuracy whether a title would be included on the New York Times adult fiction bestseller list or not—based strictly on the contents of the novel. Plot structure and emotional story beats are among the key ingredients, as Vonnegut argued.

Jockers and the data team at the tech startup Authors A.I. have recently created an artificial intelligence named Marlowe that analyzes fiction manuscripts. And after ingesting thousands of popular fiction titles, it turns out that Marlowe concurs with the late Professor Vonnegut about story shapes at a high level, if not in all the specific details.

So what has Marlowe deduced about story shapes?

Here are the major story shapes—visual abstracts of plot archetypes—that Jockers’ artificial intelligence has identified in modern fiction, with recent examples drawn from the bestseller lists:

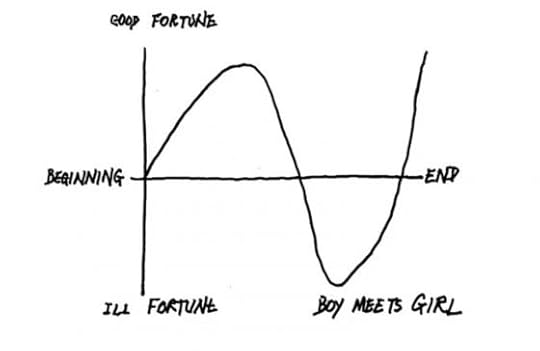

1. Emergence

There’s a broad swath of stories with a lighter touch where the narrative drive centers on the main character’s journey of transformation or her triumph over adverse circumstances. The stories often start with a negative emotional valence, with the protagonist in a tight spot or feeling lonely, sickly or unappreciated. Characters gradually overcome a perplexing or complex series of problems, with the plots often featuring miscommunications, separations and other obstacles until the protagonists achieve success (love, wealth, wisdom) and arrive at a happy ending.

Most romance literature fits this story shape. Broadly speaking, these novels have an overarching plot shape of two lonely souls who meet each other, fall in love, encounter a serious setback or tragedy, overcome it and live happily ever after.

Vonnegut called this a Boy Meets Girl story shape, though he noted that it needn’t be about a boy or a girl. Others have called this kind of story Classical Comedy. The Authors A.I. team of authors and data scientists determined that, while humor is often a feature of this story shape, it is not the defining characteristic. Jockers said that Emergence connotes a journey through difficult times toward a positive outcome.

Classic examples of this shape include Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing and George Barr McCutcheon’s Brewster’s Millions. In modern culture, films like Jerry Maguire and most romantic comedies fit this archetype. In recent literature, John Irving’s The Cider House Rules, Bruce W. Cameron’s A Dog’s Purpose, Danielle Steel’s The Gift and William P. Young’s The Shack fit the Emergence story shape.

2. Man in the Hole

Jockers and his team named this story shape in honor of Vonnegut, who reminded us that this kind of story doesn’t necessarily involve either a man or a hole. (Other theorists have offered different names for this story shape.)

In this story, the protagonist confronts an antagonist or a threat to a person or society at large that must be thwarted. The threat may be a madman, a corporation, a fire-breathing dragon or any formidable foe. The main character must pursue and extinguish the threat, at great personal risk, turning ill fortune back to good—and resulting in a lasting change to himself.

Vonnegut summed up Man in the Hole this way: “Somebody gets into trouble, gets out of it again.”

Classic novels with this story shape include Bram Stoker’s Dracula, James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. Modern examples include John Grisham’s The Runaway Jury, Matthew Quick’s The Silver Linings Playbook, Anita Diamant’s The Boston Girl, Charlaine Harris’s From Dead to Worse, Kathryn Stockett’s The Help and Dennis Lehane’s Sacred.

3. The Quest

We’re all familiar with quest stories, where the protagonist and companions set off on an adventure to retrieve a valuable object or achieve some other tangible goal despite formidable obstacles along the way. The Greek myth of Jason and the Golden Fleece, The Wizard of Oz, Raiders of the Lost Ark and Star Wars are all examples of a Quest saga. Joseph Campbell’s well-known Hero’s Journey is basically a Quest story.

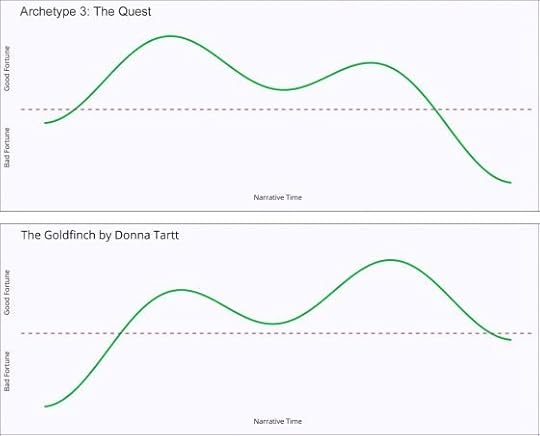

In a computer graph, Quest stories’ narrative arcs resemble the letter M. According to the Marlowe A.I., Richard Adams’ Watership Down, most of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books, Rick Riordan’s The Lightning Thief, Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, Emily Giffin’s Love the One You’re With, Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, Donald E. Westlake’s What’s the Worst that Could Happen? and Steve Berry’s The Lincoln Myth have shapes that correspond to the Quest story archetype.

4. Rags to Riches

The idea here is that a main character (usually the protagonist) gains something she lacks through a happy twist of fate—wealth, prestige, love, power—loses it, then regains it at the end. The hero here is often an unremarkable or downtrodden person who has the potential for greatness and grasps the opportunity to fulfill that potential through luck or pluck. Some have called this story shape Coming of Age.

In his online masterclass, David Mamet describes the rags-to-riches tale as “an underdog story, wherein a simple, relatable character receives newly begotten privilege (whether via luck, conquest, or a magical trickster like a fairy godmother) and must balance the duties that come along with that privilege.”

Examples of Rags to Riches in classic literature include Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper and Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield. Modern examples include Amy Tan’s The Kitchen God’s Wife, Stephen King’s Misery, Robert Ludlum’s The Aquitaine Progression, Liane Moriarty’s Big Little Lies, Anita Shreve’s Testimony, Sandra Brown’s Smoke Screen and Paula Hawkins’ The Girl on the Train.

5. Voyage and Return

In these tales, characters are plunged into a strange and foreign land, come to grips with it, confront setbacks and dark turns but wind up in the end with a return to safety and some form of normalcy—as well as achieving a degree of understanding during their journey from naïveté to wisdom.

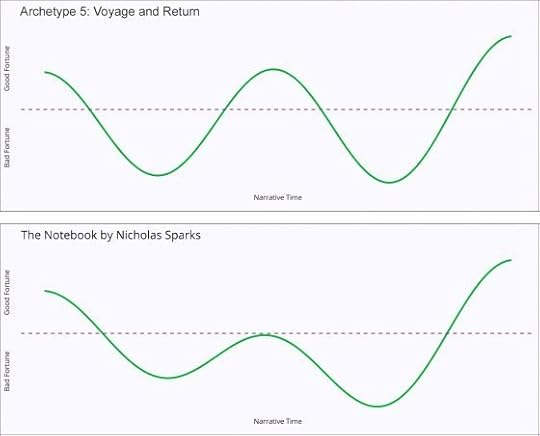

Homer’s The Odyssey, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, James Joyce’s Ulysses and H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine fit this story pattern. In more recent popular fiction, Andy Weir’s The Martian, Nicholas Sparks’ The Notebook, James Patterson’s Hope to Die, Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road use the Voyage and Return story archetype—whether the authors knew it or not.

6. Rise and Fall

Marlowe parts ways with Booker and Vonnegut on this story shape. In these stories, things can start out in positive or neutral territory, a crisis confronts the main characters, they overcome it, things seem to be moving in the right direction but then something awful befalls them at the climax. Jockers speculates that the late Booker called this Rebirth because the plots tend to feature main characters who experience change, renewal or transformation. But those positive values are ultimately thwarted by outside forces. So Jockers and company are calling this story shape Rise and Fall.

In this archetype, a dark force creates a dip into negative emotional terrain in the first act as the protagonist’s values are tested, according to Marlowe’s data visualizations. The characters overcome that challenge at the heart of the plot and achieve some measure of success before things fall apart at the end.

Hans Christian Andersen’s The Snow Queen, Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, French novelist Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve’s Beauty and the Beast, and Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden are classic examples of this story shape. In modern times, E.L. James’ Fifty Shades of Grey, Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, Stephen King’s The Stand, Jodi Picoult’s Leaving Time, Kate Morton’s The Forgotten Garden, Anne Rice’s The Vampire Lestat, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Will Wight’s Unsouled, Jeffrey Deaver’s The Blue Nowhere, Lev Grossman’s The Magicians and Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash are all examples of this story shape, the A.I. analyses say.

7. Descent

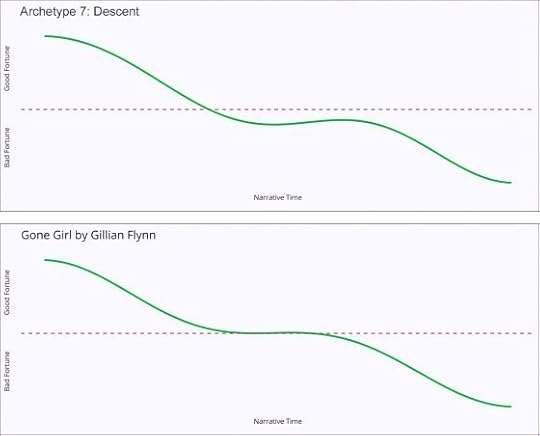

While other story archetypes see endings where the heroes triumph over powerful foes, this story pattern takes a darker turn and ends in loss or death. (Others have called this story shape Tragedy or From Bad to Worse.)

Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, King Lear, Julius Caesar and Macbeth, Gustave Flaubert’s Madam Bovary and Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray are examples of classic literature that fit this story archetype. Modern examples include Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, Lauren Weisberger’s The Devil Wears Prada, Scott Smith’s A Simple Plan, Mary Higgins Clarke’s Where Are the Children, Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October, John D. MacDonald’s The Deep Blue Good-by, Candace Bushell’s Sex and the City, Mark Edwards’ The Magpies, Sara Shepard’s Pretty Little Liars and even Lilian Jackson Braun’s The Cat Who Could Read Backwards are all examples of the Descent story shape, according to Marlowe.

Using story shapes in your writingVonnegut, of course, wasn’t the first scholar to broach the idea of story shapes. Over the years, others have weighed in with their own takes. In 1959 William Foster-Harris distilled stories into three basic buckets: happy ending, unhappy ending and tragedy. Ronald B. Tobias identified 20 story forms in his book 20 Master Plots. In his 2004 book The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker distilled novels into seven basic narrative forms (though his book actually offered nine in all).

Now add Marlowe the A.I. to the list of story shape theorists.

Jockers points out that as you study the masters, you may start to notice certain patterns emerge in their storytelling. For instance, Isaac Asimov tended to favor The Quest and Descent archetypes. John Grisham likes to use the Emergence and Descent archetypes. Dean Koontz typically evokes Rags to Riches. Stephen King studiously avoids Rags to Riches but uses most of the others. Danielle Steel also eschews Rags to Riches in favor of Man in the Hole. Mary Higgins Clark uses several but avoids Emergence and Rags to Riches. Jean Auel (who wrote the Clan of the Cave Bear books) favored Man in the Hole. Agatha Christie preferred Descent and Rise and Fall. Charles Dickens regularly turned to Descent.

“What’s fascinating is that if you pull back the camera and abstract the shapes sufficiently, our A.I. has identified the story archetypes that appear over and over across generations and across genres,” Jockers said. “Readers come to a novel with certain expectations. If you stray too far as an author, it can betray readers’ desires—or worse, bore the hell out of them. Literary experimentalists like James Joyce can get away with this sort of rule breaking. But Ulysses, for all its wonder, never made it onto tens of millions of readers’ nightstands.”

Jockers said his takeaway from the early analyses produced by his company’s artificial intelligence is that archetypes serve as just another tool to help writers form a conceptual framework for their storytelling.

“It’s important to keep in mind there is no one single ‘correct’ way to write a novel,” Jockers added. “Don’t become paralyzed with fear because your story doesn’t seem to match one of these story shapes. It’s important to look at story shapes not as formulas to copy but as storytelling guideposts to help keep the big picture in mind when writing your story.”

In short, you need to decide where you want to wind up before filling in the details of how to get there. And you’ll want to find the story rhythms that work for you.

February 1, 2021

The Importance of Finding Your Marketing Sweet Spot

Photo by Robert F. on Unsplash

Photo by Robert F. on UnsplashToday’s guest post is an excerpt from the new book How to Market a Book: Overperform in a Crowded Market by Reedsy founder Ricardo Fayet (@RicardoFayet).

One of the first (and only) books I read about startup marketing, with a view to apply its advice to growing Reedsy, was Traction. Published in 2014, it’s a fairly old book now, and I wouldn’t necessarily recommend it anymore to startup founders. However, one of its central marketing principles remains crucial to anyone trying to market anything—and yes, that includes you and your book. In fact, I interviewed one of the authors of Traction a few years ago, who said as much.

See, the core idea of the book is that there are hundreds of different ways, or “channels,” to market a product or grow a company. The secret of success is not to do all of them, or even as many as possible. Instead, it’s to find the one or two channels that work for your company and focus all your energy and resources on just those.

I find that this concept translates particularly well to book marketing. In the book realm, these “channels” include Facebook ads, Amazon ads, BookBub ads, price promotions, email marketing, group promos, newsletter swaps, Amazon SEO, Goodreads promos, guest posting, events, social media, and more.

When you’re starting out, you’ll probably be tempted to do all those things, because you’ve read about them everywhere. But that presents the same problem as trying to be on all the social media platforms: first, you don’t have the time for that, and second, you probably won’t be good at all of those platforms.

Finding the sweet spotTake me, for example. I love helping authors market their books, and I’ve run Facebook, Amazon, and BookBub ads; built mailing lists; used reader magnets; organized price promotions; and done everything else under the sun.

So I’ve done all those things, but I know I’m a lot better at some of them than others. When it comes to advertising, for instance, I know I’m much stronger working with Facebook ads than with Amazon ads or BookBub ads.

Other authors, like David Gaughran, are pros at BookBub ads, but hate Amazon ads. And still others have cracked Amazon ads, but don’t even touch the other two platforms.

We all have different sensibilities to different marketing channels—that’s just how we are.

But how we are is just one part of the equation. The other part is how our readers are. You might be a pro at BookBub ads, but if your book is on a niche nonfiction topic, BookBub’s audience for that topic will be pretty limited—and running ads there won’t be effective for long.

While some channels will work for almost any genre (e.g., Amazon ads), many others will only be suited to some genres (or even some particular books).

So how do you find that sweet spot? How do you find a channel you’re good at and that resonates with your readers?

Well, you test. But the thing is …

You can’t test everything at once.The other core principle of Traction intersects with one of the main mistakes I see authors making when it’s time to market their books: they’re trying way too many things at the same time.

It’s natural, after all: if you don’t know what’s going to work, you might as well try ten different things at once to find the one or two that will work.

But the problem is that you’ll never manage to get a channel to work if you’re not focusing all of your energy on it.

Let’s look at an example. You just published your book, but it’s not selling after one week. So you panic (naturally) and perhaps start googling “book marketing ideas.” That’s when you find all of these things you “should be doing” but aren’t. So you could:

Change your Amazon keywordsStart a mailing listStart boosting your posts on FacebookStart an Amazon ads campaign with a few obvious keywordsBook a bunch of price promotion sitesCreate a “reader group” on FacebookStart tweeting five times a dayReach out to fifty book bloggers in your genreAnd you know what? None of these channels is going to work, because you’re going to execute all of them badly. Even if you execute one well and see your book’s sales increase, you won’t know which channel was responsible for it!

All the channels I’ve listed above take time to learn and master. Until you’ve put in that time, you won’t be able to test them properly.

So whenever you’re feeling overwhelmed by marketing (or whenever your to-do list gets out of hand), take a breather and reevaluate: “Do I really need to do all of this?”

Pick only two things, and spend a month focusing on them. Take courses, ask colleagues, read blog posts, and then put in the time to properly test each channel.

That’s the only way you’ll find that sweet spot—or, in other words, that golden channel that will change your marketing forever.

Note from Jane: if you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out Ricardo’s new book How to Market a Book: Overperform in a Crowded Market.

January 26, 2021

The One Thing Your Novel Absolutely Must Do

Photo by Andrea Piacquadio from Pexels

Photo by Andrea Piacquadio from PexelsToday’s post is by regular contributor Susan DeFreitas (@manzanitafire), an award-winning author, editor, and book coach.

Start in the middle.

Get all the important characters on the page in the first chapter.

Reveal what the protagonist wants.

Reveal the protagonist’s vulnerabilities.

Establish what’s at stake.

There are a whole lot of books on the craft of fiction out there, and it can feel like every one of them makes the case for one thing your book must do if it is going succeed. And for the most part, their recommendations are good.

But as far as I’m concerned, the novel is novel, in that it’s constantly being reinvented, which means precepts like those above can go right out the window if it serves the story.

There’s only one thing that any novel must do if it’s going to succeed, and that’s arouse the reader’s curiosity.

According to the emerging body of neuroscience associated with fiction, as soon as a reader’s curiosity is aroused, dopamine is released into their bloodstream, signaling that important information is on the way. The reader starts making predictions about what happens next, whether they’re aware of it or not, and this in turn keeps them turning the pages to find out.

And that, to me, is the foundation upon which every other ambition for a novel is built. Because it doesn’t matter how convincing your characters or setting, how well-wrought their concerns, or how high the stakes in your story—if the reader stops turning the pages, it’s game over.

But what exactly arouses curiosity? And how does curiosity work in different parts of a novel?

1. Curious openingsAt the beginning of a novel, there’s so much we don’t know, and so much we’re just starting to understand. But if the author takes the time to explain the back story in detail, it slow the pace of the story, and the reader will feel like they’ve been hit by an info dump.

In general, the most effective technique for getting the story out of the gate quickly—while still addressing the essential back story and exposition—is to tease it. Which is to say, to allude to what happened in the past, or important elements of the world building, without coming right out and explaining them.

This arouses the reader’s curiosity and makes them want to know more, so they keep turning the pages. This buys you time to get the reader hooked on the story and invested in the characters—so by the time a more detailed explanation is delivered (say, another 2–10 pages in) the reader has no choice but to keep reading.

2. Propulsive plottingOnce you’ve gotten past the opening, the biggest danger zone, in terms of losing your reader, is the middle of the novel.

This is where they’ve had all of their initial questions answered—the ones you raised with your opening, via those curious clues. Now you’ll have a number of “balls in play,” as far as the plot goes, but it’s clear that the central conflict of the plot won’t resolve any time soon (because that would be the end of the story).

So what keeps the reader turning pages? Questions.

Questions about the protagonist’s short-term goals. Questions about side plots. Questions about characters. Questions about virtually anything that is not the central premise of the novel—which is another of way of saying, questions that feel like they might be addressed within the next chapter or two.

For example: Will the protagonist stay with her abusive boyfriend? When will the boss find out what the protagonist has been hiding? Is there actually something shady about that character who seems so helpful? And was that fire in the neighbor’s house actually arson?

If you find yourself struggling with the pacing and narrative momentum in the middle of your novel, ask: What questions drive this section of the narrative? And: Am I focusing clearly enough on those questions to keep the fires of curiosity burning?

3. Unexpected endingsOnce they’re past the middle of your novel, chances are, readers will finish it. But even here, there’s a final battle that curiosity can help you win.

The end of the novel provides the answers for all the questions your reader has about the story (with a few exceptions: sometimes it can serve the story to keep a few strings hanging, especially if you’re writing a series). But even so, the way your story answers those burning questions has a big impact on how your reader will ultimately feel about the book, and what they’ll say about it to their friends.

Since your story first aroused your reader’s curiosity, they’ve been making (unconscious) predictions about what will happen next. And we all love to be right about our predictions, because that makes us feel smart.

But we also love to be surprised by an ending, to discover at least one element in it that, while it fits all the evidence that has been established in the story, and perhaps seems inevitable in retrospect, comes as a surprise.

That sort of surprise leaves us feeling that we’ve been in the hands of a great storyteller—one skilled not just in arousing our curiosity, but using it to show us something new.

It also makes us want to tell our friends about the book, and forces us not to say everything we’d like to, in order to avoid “spoilers.” And what’s more intriguing than a friend who recommends a novel they just read, but can’t tell us about the ending?

Curious indeed!

January 25, 2021

Understanding Third-Person Point of View: Omniscient, Limited and Deep

Photo credit: neil conway on VisualHunt.com / CC BY

Photo credit: neil conway on VisualHunt.com / CC BYToday’s guest post is by editor Tiffany Yates Martin (@FoxPrintEd). Join Tiffany on February 10 for her next class, Master Point of View to Strengthen Your Storytelling.

For most writers, first- and second-person POVs are fairly straightforward (though in the point-of-view family, second might be the eccentric uncle no one quite knows how to engage with).

But third-person can be the family troublemaker, so sensitive and mercurial with all its facets: third-person omniscient, third-person limited, deep third-person. (And don’t even get me started on objective third-person—that guy! Living off the grid somewhere in Montana…)

Yet besides chummy, easygoing first-person, third-person POV dominates the current publishing market, so it’s helpful, as with any difficult family member, to learn to navigate its many moods. And the two biggest bugaboos are uncertain POV and slipping POV.

The Basics of Third-Person POVImagine you are Ant-Man. For non-Marvel nerds, he’s a superhero in a special suit that makes him tiny and able to flit anywhere, including inside of people.

Omniscient third-person POV. You-as-Ant-Man can fly anywhere in the world, even into people’s minds, as well as forward and backward in time. You know anything anyone has ever known—both personal experience and empirical fact. You have access to all the knowledge of the universe, like a god.Limited third-person (also called close third). Ant-Man is on a tether to a single character—you can’t break free. You can go inside her head and be privy to all her thoughts, but no one else’s. Yet as an external observer you can also offer objective commentary on the character, and know more than she knows.“Deep” third-person. This a subset of limited-third. This POV still confines Ant-Man to a single person at a time, but now you have gone subatomic and live deep inside the character—taken over by her to the point where you think her thoughts, feel her feelings, share her experiences past and present, even talk like her at every moment. In essence you’ve become her, so you can only know anything that she knows: what she sees, hears, feels, experiences, does, remembers.Using POV with clarity means understanding and not violating the parameters of whichever one you’ve chosen. Uncertain or shifting POV will make your reader feel ungrounded, unsettled—and unable to deeply engage in the story because we don’t feel we have firm footing in it, even if we can’t place exactly why.

Using POV ConsistentlyThis is where imagining your access as Ant-Man may help prevent POV slips.

In omniscient POV: The narrator can indeed flit into any perspective, but the narrator doesn’t “become” any character. That means you can reveal anyone’s thoughts and reactions—and also comment on them, and also provide perspective that they may not have. You can also offer external observations on all characters—their appearances, expressions, reactions, etc.

But if the narrative slips into anyone’s direct point of view, it’s a POV shift that can subtly disorient readers. And if you-as-narrator zoom around characters’ perspectives too much, you’re “head hopping,” jumping from person to person in a way that can be dizzying for the reader, like someone relentlessly channel-surfing.

In limited third-person: You-as-narrator are still a separate voice or “character”—an observer, a reporter on events rather than experiencing them directly, but imagine there’s an invisible electric dog fence around your single POV character. While you can know and report on what that character thinks and feels, the only way you can convey any other character’s inner life in this POV is through the interpretation of your point-of-view character, based on what he observes in others and around him: external reactions like their expressions, gestures, demeanors, tones, etc.

Also, in limited-third person you the narrator can observe something she misses, like the keys dangling from his hand, or the fleeting sneer across his face, or the way he watches her when she’s not looking. You’re always in the room with her, but not always inside her. (In omniscient you can see all of that, including the keys behind the other character’s back, where he’s been, and what he’s actually feeling.)