Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 76

December 3, 2020

How to Move From First Draft to Second Draft to Publishable Book

Today’s post is by Allison K Williams (@GuerillaMemoir). Join Allison on December 16 for the online class Second Draft: Your Path to a Powerful, Publishable Story.

You’ve heard a lot about the rough draft—the “Vomit Draft” or the “Shitty First Draft” or Jenny Elder Moke’s wonderful “Grocery Draft”:

Y'all stop calling your first drafts garbage. Garbage is what you throw out when you're done with the meal. What you have there is a grocery run – a collection of items that will eventually make a cohesive meal once you figure out which flavors go together.

— Jenny Elder Moke (@jennyelder) May 16, 2020

But what comes next? What do you do with your collection of words that you know aren’t done?

You shape them in the Story Draft.

The Story Draft is creative work done technically. This might be literally your novel’s second draft, or the first revision after a vigorous NaNoWriMo, or when you organize all the material you’ve generated for your memoir.

Or maybe you’re in a later draft, but “there’s no ‘there’ there”—you have beautiful scenes, but they aren’t building a continuous story with tension and conflict. Or you’ve created an amazing world, but too much is going on, and you need to focus the plot. Maybe the narrator is telling a series of experiences, rather than actively living a story.

Start by focusing on the dramatic action.

Experiences happen in dramatic situations. Stories have dramatic action.

Newspapers report dramatic situations. The reader’s emotional reaction comes from their own experience meeting the facts, rather than empathy for the protagonist or a desire to see them “win.”

Car Crash Claims Three is a dramatic situation. It’s not a story unless a protagonist takes an action, as in these examples:

Crash Claims Three: Earnhardt Jr. Vows to Race Again

Crash Claims Three: Outsider Candidate Calls for Traffic-cam Bill

The big-picture dramatic situation must create an intolerable world for the protagonist. For example, in The Hunger Games, Katniss Everdeen’s world holds a yearly kids-kill-kids-on-TV lottery. Pretty dramatic situation! But the dramatic action starts when Katniss’ sister gets picked and Katniss volunteers to take her place. If any other kid gets picked, Katniss goes home relieved and there’s no story.

Your story starts when the dramatic situation gets personal. When it directly affects the protagonist and forces them to take dramatic action; or confront their own inability to act and resolve to change, like when a memoirist embarks on a physical quest or starts a plan of self-improvement.

To find your story’s dramatic action, use the “In a World…” test.

Think about the cheesy movie-trailer cliché. There’s a shot of alien-created devastation. Or a sunrise over a battlefield. Or a sunset over a castle. A deep voice intones:

In a world…

And tells us the hero’s intolerable dramatic situation. Overturning this situation is a high-risk, high-stakes problem.

One man… [or woman, non-binary person or non-gendered being]

That’s the protagonist. In fiction, the hero or main character. In memoir, the author. In our imaginary movie trailer, probably a Hemsworth.

Must…

…take a dramatic action. Embark on the quest. They must do it. Not “kinda-sorta feel like doing it,” not “maybe if they have time,” they must. The action is urgent and compelling and they can’t live without taking this action.

The rest of the movie trailer shows the hero attempting different actions to overturn the unacceptable world or situation and get to the goal. Moments flash of the villain(s) and primary obstacles, including character flaws and physical challenges, and show us the stakes—what the hero will lose if they fail.

For fiction writers, the “In a World…” moment is almost always in the first chapter, often in the first paragraph. It’s usually pretty easy to figure out:

In a world…where Theodore is alone and on the run…One kid must locate a priceless painting before he and his friend are killed by gangsters. (The Goldfinch)

In a world…where poverty can kill you and a girl is a washed-up old maid at twenty…One girl must marry a rich husband without violating her own scruples and avoid the jerk next door. (Pride and Prejudice)

In nonfiction and memoir, the premise is usually clear in the title and subtitle of the book. Seriously! Right there on the cover, expressed in a sentence. What’s the untenable existing situation? What’s at stake for the narrator (memoir) or the reader (self-help)?

Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Coast Trail

Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent and Lead

We should also know the stakes.

Preferably in the first chapter. What’s the positive effect on the reader or narrator’s health and happiness if the situation is overturned, and how will they be harmed if they fail?

In a world…where I’ve screwed up my relationships, taken too many drugs, and slept with too many people…I must walk 2600 miles to find myself.

In a world…where we’re taught that vulnerability is weak and must be hidden…you must connect with others and develop genuine compassion in order to live a wholehearted life.

Chances are, if it’s hard to find your “In a world…” moment, your stakes aren’t high enough. The dramatic situation isn’t personal, or the protagonist doesn’t have enough at stake to make the story compelling.

Now you try it.

Write one of these sentences for your story, adjusting the connecting language as needed:

Fiction/Memoir/Active Story: In intolerable SITUATION, PROTAGONIST must ACTION against OBSTACLE toward GOAL or else/because STAKES.Memoir/Literary Fiction/Self-Help/Quiet Story: In ENVIRONMENT, HERO must EXPERIENCE against PRESSURE toward ENLIGHTENMENT and READER TAKEAWAY needed in CURRENT MOMENT.

Now stand up, deepen your voice, and state the premise of your book. Does it sound cheesy and overdramatic?

If it does, you’ve got a story.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join me and Allison on December 16 for the online class Second Draft: Your Path to a Powerful, Publishable Story.

December 2, 2020

A Beginner’s Guide to Amazon Pre-Orders

Today’s guest post is an excerpt from How to Sell Books by the Truckload on Amazon: 2021 Updated Edition by Penny Sansevieri (@Bookgal).

As you probably know, Amazon allows ebook pre-orders for KDP authors, which helps level the playing field between traditionally published authors and those who self-publish through KDP. Even Amazon will tell you right upfront that pre-orders are great for building buzz. True. But there is a caveat. If you’re a new author with no reader base (yet), you really have to power through your pre-order and work it harder than you would if you had a series of books already out there.

How the Amazon algorithm for pre-orders works

For the last edition of my book How to Sell Books by the Truckload on Amazon, I put it up for pre-order for two weeks. During that time, I started pushing Amazon ads as soon as the book page went live, and this early ad run helped push the book up the bestseller list. I also ran a new kind of promotion that was like a buy one, get one—but instead of gifting a second book, we gave readers who pre-ordered the Amazon book access to a video program.

That push for pre-orders within a short window really helped the book build up a strong head of steam before the actual launch day, when it just exploded. In fact, if you’ve taken one of my classes recently, you know I lead off with all the bestseller status ribbons my book has earned.

There’s a certain amount of momentum that a book captures organically when it first appears on Amazon. It sits in the “new release” section of Amazon, which can be a great spot to attract additional interest. However, if your book is on pre-order and then hits the Amazon system on launch day with little to no buzz, no reviews, and no activity, it’ll quickly plummet due to low sales, which is really hard to recover from. Books that sink down the Amazon list on launch day can take a long time to resurrect. In the testing I’ve done, I’ve seen this kind of recovery sometimes take three months or longer. But even if you have no immediate reviews, running ads will help keep the book up within its category.

In order to avoid your book tanking on Amazon, you need to plan a solid promotional campaign for the day it launches. You can start to drive some interest to the book by letting your friends, family, and followers know it’s coming. If you have anything you can give readers access to that might generate a strong motivation for them to pre-order, then do so. You could give them one of your other books for free if they buy your current one, or if the book is part of a series you could gift them an earlier book in the series if they haven’t read it. Some authors give tote bags. But regardless of the “gift,” make it as creative and original as you can.

Pre-orders for first-time authors

If it’s your first book, and you have no real platform, I’d skip the pre-order. Why? Because a pre-order is a great tool if you’re ready to hit the ground running when your book launches. If you do a pre-order and launch your book, but it takes a month or months to get reviews, it hurts your exposure on Amazon. The system is geared to pushing books that are selling right out of the gate. If you decide to do a pre-order, don’t do a long one—two weeks or a month at the most, and be prepared to move quickly when your launch date arrives.

Most important of all: spend your marketing time wisely. Don’t spend a ton of time marketing your pre-order page as a new author, because even if you have a fan base you likely won’t get a ton of orders. Sure, you can do a small push to friends and family and to a mailing list if you have one, but at this point it’s smarter to consider your use of Amazon categories and keywords, and the work you can do after the book launches, as well as Amazon advertising.

In a good majority of cases, it’s better for new authors not to do a pre-order at all.

A note about reviews: Keep in mind that readers can’t review a pre-order book. If you’re looking to get some early reviews, consider focusing on Goodreads, where you can push for pre-order reviews and provide ARCs (advance reader copies) to potential reviewers.

Pre-orders for published authors

If you have a book out there (or several), and you’ve built a mailing list of fans, then pre-order can build excitement for your upcoming book. But most, if not all, of your marketing should be reserved for when the book is available on Amazon, because that will result in a much bigger benefit for you.

Unless you are James Patterson or some other mega-bestseller, it’s not easy to drive significant numbers to your pre-order page. The other issue is that if a reader wants something now, they may not want to wait for your book to be ready and could end up buying something else instead. That said, pre-order can be a lot of fun for fans who’ve been waiting for your next book.

How long should the pre-order last?

Regardless of the category you’re in, don’t stretch the pre-order time to the full 90 days Amazon allows. If you aren’t spending a ton of time promoting the book, you don’t want it up for too long. My ideal would be actually two weeks. But those two weeks should be spent on a solid, focused effort.

Also, don’t fail to hit the deadline you assigned to the pre-order, because once you select it, you can’t go back! Pick a date you know you can hit. Amazon penalizes authors who miss their pre-order date.

Pricing your pre-order

I would keep it low, even if you plan to raise the price later. You’re competing with millions of titles on Amazon, and your book isn’t even out yet. If you want to entice an impulse buy, keep the pricing low at first. Once the book is live, you can always raise the price.

How to set up your pre-order

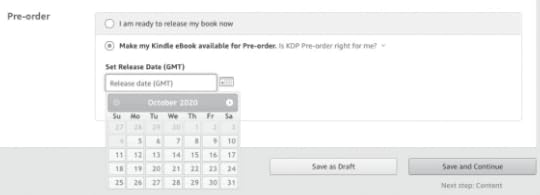

First and foremost, you need to be a KDP author. Your ebook should be uploaded into the KDP system via their author/book dashboard. Once you’re there, you’ll see this:

Once you select a date, the system will tell you that you must get the final book to Amazon no later than four days prior. Additionally, you will need to upload a manuscript for them to approve before they’ll set up your pre-order. The manuscript doesn’t have to be pre-edited; they just want to see what you plan to publish. You’ll need a cover, but it doesn’t have to be a final version. If you’re still a month out with no cover (it happens more often than you think), you can leave the cover blank or put up a placeholder, then add your cover before the pre-order goes live. Here’s what the page looks like when it’s launched on their site:

According to Amazon, the book can be any length, so if you’ve written a novella, you can use pre-order too. Currently there are no limitations, other than that you need to be a KDP author, and, if you’re an indie author, this is for ebooks only.

Pre-order is a fun, cool option for self-published authors, but be mindful of how much of your money and promotional sweat equity you spend. Most readers prefer to buy a book they can read right away. The urge for instant gratification is especially true for ebook readers, because for them, it truly is instant.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, check out How to Sell Books by the Truckload on Amazon: 2021 Updated Edition by Penny Sansevieri.

November 24, 2020

Literary Agents Discuss Foreign Rights and the International Book Market

Today’s guest post is a Q&A by Sangeeta Mehta (@sangeeta_editor), a former acquiring editor of children’s books at Little, Brown and Simon & Schuster, who runs her own editorial services company.

For most writers, it’s a dream come true to have their book published in a foreign country. There’s little that tops the excitement of finding their book in bookstores when they travel abroad, of seeing how different publishers interpret their cover and title, of being able to create a gallery of their foreign editions, print or digital.

But should writers seek publication in the US even if their book’s sensibility isn’t “American”? If they already have a book deal, who should control their book’s foreign rights, their agent or their publisher? How do agents and publishers determine which geographic and language territories they should target around the world, and what sorts of challenges do they face when dealing with foreign publishers?

I spoke with literary agents Priya Doraswamy of Lotus Lane Literary and Carly Watters of P.S. Literary, both of whom have worked extensively in the international market. As with all my Q&As, neither knew the other’s identity until after they submitted their answers to my questions below.

Sangeeta Mehta: Do you actively take on clients who live in other countries? If so, aside from finding a time to communicate, are there any challenges you and your clients face, such as dealing with currency conversions or publicity opportunities? Are American publishers sometimes reluctant to work with writers outside the US for this reason?

Priya Doraswamy: Yes, I do actively take on clients who reside in other countries. While the work itself is fulfilling, there are logistical as well as other challenges that make it difficult sometimes. As you rightly say, one of the challenges is contending with time differences. The other issue is the expense. Before WhatsApp, and other apps, communication by phone was awfully expensive, but now it’s much easier and affordable to communicate with authors in far-flung regions of the world.

The time difference also makes it tough for clients in Asia and Europe to participate in online and in-person marketing and PR opportunities in the US. For instance, authors lose out on virtual live book events, tours and conferences. As for in-person events, unless the author has the means to visit the US, book events, tours and conferences are also ruled out.

The other issue is because of lack of author provenance in the US, it is much harder to elicit TV/radio and press engagements. The only exception is when the author is an international celebrity, or has deep connections to the US media, which then makes it easier for the author to promote their book. Some of my nonfiction authors who reside in Asia and visit the US for work have hired US PR firms to promote their books. Sometimes this route works and sometimes it does not, as it is very specific to each book and each market.

Currency conversions are less of a problem, as there are many platforms to get monies from the US to other parts of the world these days.

It’s really wonderful that American publishers are not hesitant to work with authors residing outside of the US. For fiction, it’s never an issue, but with certain types of nonfiction it could be an issue purely because the author’s connection to the US is necessary to sell the book.

Carly Watters: I do actively take on clients who live in other countries but only if their primary market is for North American sales since I’m a North America-based agent. If the writer is UK-based with a book that is better suited to the UK market, it might be best for them to find a UK agent. There are no currency conversion issues (a lot of publisher payments are going digital—finally!) but there can be many tax forms to fill out.

The theme of many of my answers will be this: great books travel, great writing is the great equalizer and great writing opens doors. American publishers do need books that work for their market (US readers specifically)—publishing is a business—but amazing books by extremely talented authors will find fans domestically, and if economics, marketing, publicity and global trends collide, they’ll find international fans, too.

If the author is not based in the US, the American publisher isn’t going to pay to fly them over to do promotional events, bookstore launches (when we used to do those pre-Covid!) and such. These will be done remotely so authors do lose a bit of that on-the-ground connection with local booksellers, etc.

Describe how you handle foreign rights for your clients and the advantages to your agency’s approach. For example, does your agency have an active foreign rights department that regularly attends international book fairs, such as Frankfurt , London , and Bologna ? Do you partner with co-agents in specific countries or territories? Or do you tend to grant world rights to the publisher?

PD: Great question! As you know, I am a solo agent, which means that I don’t have a rights department in-house. I personally handle all rights. I regularly attend the London Book Fair and the Jaipur Lit Fest to sell rights.

While agents and authors would love nothing more than seeing their books being published across the world in various languages, I have come to understand that not all books have legs to travel the world. The reasons for this are myriad, but if I must narrow it down, the metric is usually how successful sales were in the US coupled with thematic resonance of the book. Having said that, and of significance here, is to know that not every book that has sold successfully in the US will get multiple rights offers from other territories. The same holds true for other regions as well. Just because a book has high sales in one region, there is no guarantee that the book will travel to other regions. While this is discouraging to authors and agents, it is the reality of publishing.

I don’t have a carte blanche rule on granting world rights to publishers, and it’s more on a book-by-book basis. For some of my titles it makes more sense to grant world rights to publishers with a strong rights department team that attend many of the international rights conferences and fairs. In instances where a large publisher shows strong interest for world rights based on their outreach and excitement to take it to the world market, and where the author and I are confident of their approach, we grant world rights.

I also work closely with book scouts, and from time to time, with co-agents.

CW: We work with Taryn Fagerness Agency to sell our agency’s foreign rights. We consult with her every time we’re pitching a new project to work on a strategy for either retaining rights or selling them to the publisher and ask her what the benefits are for each strategy. Publishers are extremely bullish for all rights (translation and audio) right now so it’s a battle to retain them. I only grant world rights to the publisher if the deal is structured in a way that is beneficial to the author (lots of money to compensate for giving up those rights), or it looks like there won’t be many sales, if any, because the book is “too American” or it’s a lifestyle title that’s North America-specific and likely won’t travel anyway. If I grant world rights it’s often for children’s picture books and cookbooks because highly illustrated or photographed books are very expensive to produce and the business model for those really only works if the publisher has the rights (so they can sub-license or distribute them). The publisher also has all the files (graphic, illustrations, edited images) and that whole package stays together when a translation right is sold.

With publishing companies continuing to merge (Simon & Schuster and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt are up for sale) and the bigger publishers acquiring many smaller publishers (there are too many of these to name from the last year), the big publishers think that their rights departments can handle selling the foreign rights and the reality is that they just can’t. They think their in-house rights team is automatically a selling feature, but it’s not. That in-house machine will always be used for the top few percent authors. If rights departments only have 30 minutes at Frankfurt Book Fair to talk about their titles, do you think they can cover everything on their list? They simply can’t. Things slip through the cracks. And as agents we want to prevent that. Everyone is in this business to make money, of course, and to acquire rights to sell them, but agents have their clients’ best interests at heart whereas publishers can treat them like commodities at times.

Do you sometimes broker deals for American clients with foreign publishers rather than with US publishers? If so, how likely is it that the book will eventually be published in the US? What circumstances are usually necessary for simultaneous publication whereby US and UK publishers, for example, release the book on the same date?

PD: Yes, I have brokered deals for American clients with foreign publishers rather than US publishers in the first instance. I have had fairly good success with eliciting US deals after I’ve sold rights in other territories.

Trying to get simultaneous publication across the Atlantic is always challenging since publishers work with different publication schedules and it’s really tough sometimes to match up publication dates.

The more worrisome problem with not being able to match publication dates is the issue of foreign editions “illegally” becoming available via Amazon and other online retailers in US markets before the US edition is available for sale. Pricing of books varies significantly in different territories and is usually much lower when published in Asia. When these editions become available in the US/UK market, it undercuts publishers in their own home markets. As you may know, anyone can be a retailer on Amazon and other online platforms, and these private parties acting as retailers sell books via the platform, disregarding publishing contracts. This is a serious problem for authors, agents and publishers since these private online retailers don’t honor publishing contracts that restrict sales to specific territories.

Over the years, I’ve lost out on opportunities with publishers in Europe and the US who love my projects but refrain from making offers for books that have been previously published in certain territories, as they simply cannot compete with the low priced books coming in from these territories. It’s especially tough for mid-sized and small/independent publishers for whom sales on Amazon and other online platforms are crucial to their business models as they mostly sell their books via online retailers rather than brick-and-mortar stores.

CW: For me, if I’m working with a Canadian client, it can be easier to do a Canadian deal for Canadian English rights and then sell the ROW (Rest of World) after either by separating all rights or selling ROW minus Canada to a US publisher. It’s all about who the primary market is, what the market value is, what’s best for this particular book and what’s best for the author’s brand and career. In order for a book to be published at the same time in multiple countries, it needs to be acquired very early with a publishing date that supports the global partnership (maybe Penguin Random House Canada and Penguin Random House US is a combination that knows how to work well together); that way the manuscript can go into production with both publishers’ editors’ notes and with lots of time to spare.

It’s a challenging situation because as an agent, you have to separate these rights from day one and submit the project with your definition of the open market very clear, with the hopes that you can go ahead and sell this project in translation. However, if you accidently or without paying attention don’t define the territory correctly (for example, “Commonwealth” means different things to different publishers) it’s nearly impossible to sell the rights elsewhere. We try to be as clear as possible from day one and redline the Schedule A with publishers very carefully. Sometimes editors will agree to things to get the deal moving or closed, and then you get the contract draft from the legal department and it does not incorporate what you agreed to in the deal stage. Agents are very important in this process!

In your experience, what determines if a book being published in the US can find an audience abroad? Does it depend mainly on the book’s main themes and if they are universal? The genre or category? The trends of certain markets and how closely they follow those of the US? Or is the publicity surrounding the book deal (or book launch) the biggest predictor of its success around the world?

PD: The good news is that books being published in the US usually have a higher chance of finding a global audience than the other way around since the US is the market-maker for books and media. Oftentimes, publishers and agents from other territories are more willing to consider books for their territories, if the book has been published in the US and has gotten good press and publicity. Fiction in all genres, and nonfiction that relates to health and the human condition (i.e., any themes that are universal to people the world over), garners the most interest from other parts of the world.

CW: It’s an alchemy of sorts. A big “deal story” (six figures, sold at auction, or major pre-empt) is a great starting point. Universal themes that travel are also key. Content that is offensive to other markets is something to consider avoiding. (It could be offensive due to religious preferences; for example, certain animals are sacred in certain markets, and the children’s book publishing industry knows all about being sensitive to that.) Overall, we never know what’s going to sell abroad. If we all knew then we’d have all clients as international bestsellers! Remember that every country also has their own experts, their own bestsellers and national treasures that they love. Especially in nonfiction, you can’t always crack certain markets no matter what you write. I have clients whose books have sold in over 20 territories and it’s amazing, but it’s a bit of a domino effect after a while; no one wants to be the country that misses out when something has sold in over 15 or 20 languages.

Finding a global audience also depends on factors that change as a career progresses. Many of the questions posed here are about one book, but having a career as an international bestselling author means that some of your books are going to hit in the foreign market and some books won’t. And they often aren’t acquired or even published in the same order as the US books (unless they’re part of a series). It’s a very complicated thing to manage the long-term success of an author domestically AND abroad. All markets are different. Just like I’m an expert in North America, there are co-agents on the ground in every territory that know their market, too, and spend a career growing and perfecting their knowledge of it.

How would you advise a novelist writing in English whose story takes place in their home country (whether it’s Canada, the UK, Australia, or India) but whose sensibility is, arguably, American? Would an American agent or publisher be the best fit? If the novel’s sensibility is more specific to the writer’s home country, is it better to explore publishing opportunities there?

PD: Getting published in and of itself is quite a feat, and therefore regardless of where an author is published, it’s an accomplishment. If a writer wants to be published in the US, then my advice would be to seek an agent based in the US, or a non-US agent who has deep connections in American publishing.

CW: The US market is the biggest in the world. The UK market is big too, but the US has the largest amount of readers. It has the biggest connection to TV/film rights, too. Ideally, you’d find an agent whose primary markets are the US and your home country (like myself! I specialize in the Canadian and the US markets and am very strategic about selling rights in North America for both my Canadian clients looking to expand into the US and US clients who have books that will do well in the Canadian market.).

Should writers who are self-publishing, or whose foreign rights have reverted back to them following traditional publication, focus on exporting the American edition of their book if they would like it to sell abroad? Can they assume that this would be easier than licensing translation rights to foreign publishers? Are there any cases in which they should search for a translator, oversee the translation, and then try to find a foreign publisher?

PD: This is a tough one! If the author wants to sell the English edition of the book, then the easiest and most economical way is to offer the print and ebook edition via Amazon or any other online portal that has a wide global reach. However, if the author wants the English edition translated into other languages, then it does become an expensive proposition because there is no guarantee that the translated book will sell in the markets it’s intended for. Truth be told, licensing translation rights is easiest when the US English edition of the work has garnered high sales and has had high visibility in the US.

CW: This is a tricky question because it’s so circumstantial. A self-published author who is a USA Today bestseller is in a different position than a self-published author selling 500 copies a year. I don’t work with a lot of self-published authors so this is not my area of expertise, but they should not search for a translator. If you do not speak the language you want your book translated into, you won’t know how good the translator is. Foreign publishers like to hire their own translators that they know and like.

Generally speaking, should authors expect smaller advances from foreign publishers than from American publishers? Less marketing and fewer sales? Or are there certain foreign book publishers that are comparable to American publishers, especially if they are part of the same global company (Penguin Random House US and Penguin Random House Canada, Bloomsbury USA and Bloomsbury UK, etc.)?

PD: I am going to make a broad generalization here and state that traditional American publishers pay bullish advances when compared to other territories. America has the largest reading market in the world and American book readers are champions of authors and the book industry, as they are always willing to purchase books and take chances on debut authors. Having said that, there are also several European publishers in various territories that also offer bullish advances to authors since they too have a large reading population who are willing to spend money on books.

CW: The American market is the biggest book market in the world. Second is the UK. From a purely economical point of view there isn’t a way for a major Scandinavian publisher to offer the same advance as a major US publisher. A bestseller in Denmark moves a few hundred copies in a week whereas a bestseller in the US, tens of thousands of copies in a week.

The Canadian market can be lucrative and it’s worth separating Canadian rights at times. If the author is Canadian (even if their book is more “American”) an agent should try to sell Canadian rights separately. There are many possible scenarios and the agent needs to be careful from the beginning how they define the rights they’re selling. Another possibility is that the agent could grant World English rights, so the US publisher can potentially sell UK rights through their in-house rights department, while translation rights are reserved by the author to be sold by the agent separately at a later date.

Do you have any other advice for writers who want to better understand and break into the international book market?

PD: Educating yourself about the complexities and intricacies of breaking into the international market is key. There are many excellent resources available for free on the internet that shed light on international rights markets. If you can afford to subscribe to platforms such as Publishers Marketplace in the US and The Bookseller in the UK, that would help greatly, too. Best of luck with your work!

CW: Read Publishing Trends, read about Frankfurt Book Fair, London Book Fair, Bologna Book Fair, and Book Expo. It’s a very specific part of the business. Foreign rights, co-agents, and scouts are so important to an author’s long-term financial success! It takes a village to become an international bestseller. Check out what books are selling in 20–30 countries and buy them. Get a Publishers Marketplace subscription and read the foreign deals.

Priya Doraswamy (@lotuslit) founded Lotus Lane Literary in 2013. Her love for books, people, and background in law makes her career as a literary agent the perfect fit for her passions and talents. She enjoys working with publishers and writers from around the world. Although physically in the EST, her work hours are zone-free. She does admit to occasionally losing track of time zones and waking a writer with an early morning phone call. Priya has been an agent for several years and has sold several books worldwide. She is drawn to all genres of fiction and nonfiction. Prior to her agency career, she was a practicing lawyer in the United States.

Carly Watters (@carlywatters) has a BA in English Literature from Queen’s University and a MA in Publishing Studies from City University London. Her masters thesis was on the social, political, and economic impact of literary prizes on trade publishing. She began her publishing career in London as an assistant at the Darley Anderson Literary, TV and Film

Agency. Since joining the Toronto-based P.S. Literary Agency in 2010 she has become a Senior VP, Senior Literary Agent, and Director of Literary Branding. Carly represents award-winning and bestselling authors in the adult fiction and nonfiction categories. She is known for her long-term vision for her authors and being an excellent collaborator with a nose for commercial success. She has close ties to publishers in the major markets and works directly with film agents to option film and TV rights to leading networks and production companies. Find out more on Twitter, Instagram, the P.S. Literary website, or at Carly’s personal website.

November 23, 2020

Pick Your Pond: How Nonfiction Authors Can Find the Right Positioning

Photo on Visualhunt

Photo on VisualhuntToday’s guest post is an excerpt from the new book Get the Word Out: Write a Book That Makes a Difference by Anne Janzer (@AnneJanzer).

Write what you know. Stay in your lane. Find your niche.

On the one hand, everyone tells you to think bigger, but then they also seem to be saying the opposite: think smaller.

The advice to write for a niche makes sense. It’s much easier to market books when they address discrete audiences or solve specific problems. When you can clearly describe the value you provide, whether as an author or in your career, people will know how to refer you to others.

But this advice is tough to hear and act on. For me, the word niche summons an image of a small nook in a wall that might hold a single vase. It is, by definition, restrictive and confining. No one wants to crawl into a tiny box and commit to spending their career there. (That sounds boring!) You have grander ambitions for your book.

At its heart, “finding your niche” is about positioning yourself and your book in the eyes of others. You do need to differentiate your book from the thousands of others on your topic. If you’re building a career around your book, be able to explain your specific take on the subject. If you’re building a broader author career, over time you will differentiate yourself as well.

First, you are not a book

Your book will consume much of your time and energy and become a major part of your public identity. Decisions about the book can quickly turn into decisions about yourself, your time, your career, your life.

Whew—that’s a lot of pressure for one book!

First, let’s get some perspective. Your book doesn’t necessarily define you. You may write several books and you will do other things. Your life’s work may change directions. Thus, choosing a well-defined focus for your book does not limit you. I’ve interviewed many authors who started in one area, only to discover that their readers drew them into entirely different, but adjacent, topics. Some people and careers cannot be contained in metaphorical boxes.

Most of all, telling a person to stick to a niche sounds an awful lot like the dismissive “Stay in your lane.” No one wants to hear that. Let’s pick a fresh metaphor to position your book.

Ditch the niche and pick a pond

If you look out the window of a plane flying over northern Wisconsin and Minnesota, the ground beneath you reflects the sky. It appears to be as much water as land. This part of the country is dotted with lakes and ponds of all sizes. (Minnesota’s nickname, “The Land of 10,000 Lakes,” is actually an understatement.) Many are connected by rivers, streams, or tiny waterways that traverse swampy areas.

As a teenager at summer camp, I once took a five-day canoe trip during which we had to portage only once. (Portage is a lovely word borrowed from the French for schlepping canoes and baggage over land. It’s much less glamorous than it sounds.) We traveled on connected waterways, from the tiniest of streams to a widening river and large chain of lakes.

I bring this up to expand on the common saying: It’s good to be a big fish in a small pond. Ponds come in many sizes, and types: prairie potholes, vernal pools, and kettle holes are a few of the types. Some are small enough to swim across quickly, others cover many acres. Some people refer to the Atlantic Ocean as “the pond.” Moreover, many are part of a larger system, connected via wetlands, creeks, streams, and rivers. So yes, as an author, you can be a big fish in a small pond—but choose your pond wisely.

Your book can begin by filling a specific pond and work its way to a broader ecosystem of lakes. When you write a book that all the fish in one pond love, a few of those fish will swim to an adjacent pond and tell their friends. Maybe word will reach the open ocean.

When Marie Kondo wrote The Life-changing Magic of Tidying Up, she wasn’t writing for everyone. She was trying to reach people who had way too much stuff in their lives and were willing to go through the wrenching act of discarding most of it. That’s a very specific subject for a finite audience, originally in Japan. The book found a larger readership worldwide, and now she has a Netflix special.

As an author, you will want to choose one or two ponds for the book you are planning to write. The size of your pond depends, in part, on who you are, your subject matter, and the people you hope to reach.

Back to the water metaphor, it takes a different set of skills and equipment to swim in a small fishing hole compared with the vast Pacific Ocean. The same is true for your book. Survey your own abilities as well as the market you hope to reach. How big a fish are you? Authors with a large existing following can choose larger markets, akin to a giant lake or fast-moving river. A well-established publisher can give you access to a larger pond, though most major publishing houses are looking for books addressing large audiences.

Your personal ponds

Picking your pond may require time and careful consideration. You are an eyewitness to the wide variety of interests and experiences that constitute your life. Perhaps you see the nuances of your subject area and want to explore them. Or perhaps the pond you want to swim in is nowhere near your current path. That’s what happened to Kristi Dosh when she found herself practicing corporate law. Her author pond was elsewhere.

Kristi was a lifelong sports fan with a particular passion for baseball. She wrote an article for her law school’s legal journal about collective bargaining in Major League Baseball. When she started practicing corporate law, specializing in commercial real estate finance and tax credits, a partner at her firm passed her journal article to a friend with a sports publication. With that, she began blogging about baseball in her spare time, now with a business perspective.

As her audience grew, the sports editor at Forbes invited her to become a contributor, and she expanded from baseball to all sports. She noticed that the posts about college sports were getting the most views and responses. She says, “People were reading. They were leaving comments. They were emailing me. My social media was growing. I was getting opportunities to be interviewed on TV and radio.”

She’d found her pond. A series of posts on football in the various conferences eventually led her to writing about college football and her book Saturday Millionaires: How Winning Football Builds Winning Colleges.

“But wait,” you might say, “I thought that baseball was her passion?” Well, the market fed her passion. “It’s amazing how much more you enjoy a subject when it’s getting attention and you’re getting positive feedback,” she explains.

The shift to the business of college sports was pivotal for her. But Kristi didn’t make that decision until she had received validation from the market.

Today, Kristi is a publicist who coaches authors and entrepreneurs as they carve out their distinct positioning. She believes that people try to force themselves into a category or space too early in their writing careers. “I think people get stuck trying to develop a niche from the day they decide to blog. You’ve got to give it a space to develop and figure out not only what you enjoy and have the expertise for, but what people want to hear more about. Where is there a gap in your marketplace for your knowledge?”

Your book’s ponds

The book you write may belong in one or more discrete ponds. Even if you believe it has wide appeal, it’s useful to focus on a few distinct market segments while writing, so that you can clearly meet the needs of a well-defined group of people who will spread your ideas. To practice servant authorship, identify discrete groups you hope to serve.

How do you pick a pond? Try zooming in along the following dimensions: subject, audience/market, and unique lens. Experiment with combining these factors to find the ponds that best fit you and your book.

Subject

If you want to write about a huge idea, it’s often easiest to get your arms around a smaller subject that represents the idea. Aldo Leopold, one of America’s most important wildlife conservationists, wrote about the environment around his own Wisconsin farm in A Sand County Almanac. He wrote of wilderness as a concept, starting with his precise location. He used the subject as the jumping-off point for essays and thoughts on man’s responsibility to nature, and in doing so became an influential voice in wilderness conversation and the environmental movement.

A narrow subject doesn’t mean the theme is insignificant. A tightly focused subject may contribute a unique perspective on a wider issue.

Audience or market

My bookshelf has three distinct books on the topic of public speaking:

Present! A Techie’s Guide to Public Speaking by Poornima Vijayashanker and Karen CatlinFrom Page to Stage: Inspiration, Tools, and Public Speaking Tips for Writers by Betsy Graziani FasbinderChampioning Science: Communicating Your Ideas to Decision Makers by Amy Aines and Roger Aines

They’re all about public speaking yet differ in their audiences and approach. The third adds another layer of subject refinement: not only is it for scientists, but it’s specifically about speaking and presenting to decision-makers. I have learned from each one.

Your unique lens

Is your perspective unique? Many big idea books fit this pattern, offering readers a fresh perspective on a large topic. The pond for a big idea book consists of people who are interested in that specific lens.

Books themselves can change ponds once they’re out in the world, while leading you to explore new waterways.

Writing a book may help you better define your career. That’s what happened for April Rinne as she set out to write Flux: Superpowers for Thriving in Constant Change.

April advises startups and governments dealing with the rapid pace of change. Her interests are wide ranging: she speaks and writes about inclusive business innovation, policy reform, sustainable development, and emerging markets. She has a law degree and a finance degree, and is also a certified yoga instructor. She loves global travel and relishes looking at the world from a fresh perspective; her website includes photos of April doing handstands on her travels around the globe.

Her book has become a unifying factor in her career. She says, “This is the first time that I actually can look at a book and a point of view as the container for everything else that I’ve done.”

Hers is a genuine big idea book that represents the intersection of her interests. Instead of a niche, she has a node. “In any network, the most powerful node is not the largest node. It’s the most connected one. If you can position yourself at the intersection of enough spokes, you can have a lot of exposure.”

print / ebook

print / ebookDon’t worry about staying in your lane, but do pay attention to the networks that connect your audiences, your books, and your interests. Of course, which pond you choose depends on where your expertise lies. As you explore the ideas for your book, identify its possible ponds:

Subject: What subject do you want to write about? Can you narrow the subject and still produce a substantial book?Market: How can you define the people who would be most interested? Is there a specific audience of readers you would particularly like to welcome? If so, what would they be looking for and how could you provide it?Lens: What’s unique about your lens on the world?

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, check out Anne Janzer’s new book Get the Word Out: Write a Book That Makes a Difference.

November 18, 2020

The Charm of the Large Word

Photo credit: g2 Duckworth on Visualhunt / CC BY-NC

Photo credit: g2 Duckworth on Visualhunt / CC BY-NCToday’s guest post is by author, editor and writing coach Mathina Calliope (@MathinaCalliope).

Big words get a bad rap.

George Orwell practically outlaws them in his famous essay Politics and the English Language (which, if you haven’t yet read, do, as soon as you finish this). It’s right there in rule (ii): Never use a long word where a short one will do.

Hemingway famously preferred short words to long:

Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words? He thinks I don’t know ten-dollar words. I know them all right. But there are older and simpler and better words, and those are the ones I use.

Using big words may feed our ego. Hemingway clearly thought they fed Faulkner’s. And ego-nourishment is no reason to use a big word.

Esoteric vocabulary is sometimes fingered for deliberate obfuscation (see what I did there?). One of the many lines our country has split along is between regular folks and elites. The former call the latter’s use of obscure words pretentious (or they would if they used big words. Instead they call it snobby). The latter find the former’s avoidance of clarity and precision to be, um, deplorable.

But big words can be beautiful. Notice that Orwell doesn’t categorically prohibit them; he implies room for their use “where a short word” won’t do. Hemingway masterfully combined short words to make big meaning, but not everyone has Hemingway’s talent or wants to imitate his style.

As with every word on a page, a big word must earn its place by communicating something vital to the author’s message. Orwell’s opposition stemmed from reading text bloated with big words that supplied no meaning or clarity. Hemingway’s motivation to avoid them seems more stylistic.

In any case, to earn its place in a text, a big word must be two things: the right word and the best word.

It’s the right word if its meaning is what you intend. It can be tempting to use a word whose meaning we sort of know; we’ve heard it in this context before. But if its meaning isn’t precisely right, some of your readers will know this, and you’ll lose credibility with them. Readers who know its meaning no better than you will not be impressed either, because they will only sort of know what you’re trying to say. Of course using such a word shows that you only sort of know what you’re saying, too.

It’s the best word if using it reduces your overall word count. Take a word like calamities in this sentence: “Not all these calamities would spell death, of course.” The sentence is from a story I wrote about things that can go wrong on a backpacking trip: a turned ankle, a leaking tent, a broken water filter, a snapped hiking pole. Using calamities saved me two words; the alternative is “Not all these things going wrong.” Would disasters have worked? Sure, but calamities is less frequently used, therefore fresher, therefore, in my opinion (yes, this is subjective), more interesting.

If a simpler synonym would be vague (e.g. problems) or if avoiding the big word creates verbosity, let the big word do its work.

One of the English language’s most beautiful features is its many words, each with a shade of meaning ever so slightly distinct from its next nearest relative. This feature lets us write with precision, which gives our ideas clarity, which improves communication, which is, after all, the point of prose.

November 16, 2020

A Successful Author Was Rejected By Her Publisher. Here’s How She Found Another.

Today’s guest post is by memoirist and Brooklyn-based writing mentor Virginia Lloyd (@v11oyd).

With three commercially successful novels published in her native Australia, Fiona Higgins is known for her page-turning stories of contemporary life. Her 2012 debut The Mothers’ Group was a bestseller, as were her follow-ups Wife on the Run and Fearless. They’ve been published in France, Spain, Portugal, Germany, and the Netherlands.

Fiona hoped that with An Unusual Boy, her fourth novel, she’d achieve the goal of publication in the United States and the UK. As her friend and former literary agent (when I lived in Australia), I’ve been Fiona’s developmental editor since her first book. She asked me to send the manuscript to Allen & Unwin, the publishing house that had supported her previous novels with the sort of marketing campaigns most authors only dream of.

Because I knew it was her best book yet, I agreed. We sent her book off and waited, hoping for a positive response.

Instead, she was soundly rejected. Why?

Here’s the story premise of An Unusual Boy

The protagonist is 11-year-old Jackson Curtis. While his life is normal from the outside—with loving but harried parents, two sisters, and a hectic school schedule—Jackson is different from everyone else. Jackson’s brain functions differently from other people’s—health professionals have described it as ‘neuro-diverse’—which leads to misunderstandings and challenges in everything from daily routines to learning and, most significantly, human relationships.

Jackson is present during a disturbing event in an elementary school restroom. His lack of understanding of what takes place there lands him in serious trouble with the police, which has a cascading effect on the world in which he and his family live. The story is advanced through the perspective of Jackson, whose endearing qualities only make his predicament more poignant, and that of his dedicated mother, Julia, who does everything she can to defend her unusual boy from a world set up for ‘normal’.

The first unexpected rejection was followed by a slew of others. The rejection notes never alluded to quality. Each and every one stated that the novel was a wonderfully written, page-turning read—Fiona’s best work to date, even—but invariably referenced marketing. A child protagonist who is neuro-atypical did not constitute an ‘easy sell’, the notes suggested. Did parents really want to read about vulnerability and difference, despite its sensitive depiction?

The most polite variation on the theme was the refrain: We wouldn’t know how to position the book in the market.

So Fiona turned to the slush pile

Frustrated but determined, Fiona came across the website of London-based Boldwood Books. Established by publishing industry veteran Amanda Ridout, Boldwood is an independent publisher of commercial fiction, focusing on social media to drive word of mouth, and word of mouth to drive sales online. Since publishing their first books in August 2019, sales are approaching 2 million books, with 20 top-ten sellers in countries around the world from authors such as Shari Low and Giselle Green. Boldwood won Independent Newcomer Publisher of the Year 2020 at the IPG Independent Publishing Awards.

Fiona submitted An Unusual Boy to Boldwood through the publisher’s website. She believed that Boldwood’s electronic slush pile was a worthwhile bet given that all publishing doors in her home territory had closed to her.

“I fell in love with Jackson from the moment I met him,” says Sarah Ritherdon, Higgins’s editor at Boldwood. “Jackson is engaging, funny, endearing and maddening all at the same time, and I found his voice instantly compelling. As the mother of two boys myself, I also found Julia [Jackson’s mother] instantly relatable—I could imagine being her friend, and I wanted the best for her family.

“When it came to my judgment as a publisher, I never had a moment of pause. Fiona Higgins is a masterful storyteller, who leads us along relatively serenely until the dramatic moment she puts her characters in a truly terrible situation, a mother’s worst nightmare in fact. From that page on we are breathless and captivated all the way to the last page. Now I can tell you, as an editor, that kind of storytelling talent is rare. I knew I had to publish it.”

Boldwood had no reservations about the storyline or positioning the book in a much larger global market, and made Fiona an offer to publish An Unusual Boy.

Taking the publishing path less travelled

While thrilled to finally receive an offer from a reputable publisher, Fiona had to weigh the pros and cons of their model. She knew and had benefited from elements of the traditional book deal: the advance against sales, the sale or return method of ordering and replenishing books from the publisher’s warehouse, the publicity and marketing plan customized to the author’s home territory. With each book she had been paid an advance upfront as a show of the publisher’s confidence in the book’s ability to generate sales and thereby earn back the sum advanced to her.

But Boldwood offers its authors a much higher proportion of royalties in place of a traditional advance. It also publishes in nine formats simultaneously—from physical copies in some locations, to print on demand, ebook and audio editions—which they believe “offer[s] authors opportunities across the board,” according to Sarah Ritherdon. Their focus is on leveraging social media internationally for sales wherever the book piques reader interest.

Fiona had to take on faith Boldwood’s ability to generate sales—and royalty income—for months after a global launch.

After careful consideration, Fiona accepted Boldwood’s offer, and they published An Unusual Boy in October 2020. In her home territory of Australia, Boldwood also took the additional step of partnering with Australia’s largest online bookseller, Booktopia, to produce a trade paper format of the novel to cater to those readers still committed to traditional print copies.

Takeaways for other authors

The experience continues to unfold for Fiona, who is relishing the experiment with Boldwood in such uncertain times.

“Publishing is changing and during this pandemic, people are seeking solace in books,” Fiona says. “Now more than ever, we read to know we’re not alone. There’s a place for all kinds of storytelling, in all manner of formats, all around the world. Traditional publishing remains strong, but alternatives are flourishing too. That’s good for everyone—for publishers, for writers, and especially for readers. I’m glad this story finally found its place in the world, because it’s an important story—about difference, social inclusion and deconstructing the idea of ‘normal’. Any parent will tell you, when it comes to family life, there’s simply no such thing as normal.”

The irony of this ‘unusual’ path to publication for her latest novel isn’t lost on Fiona, either. “The fact that it was a struggle to get An Unusual Boy published is actually quite apt. It’s almost a grand metaphor for what it’s like parenting a neuro-atypical child—families like Jackson’s are living the road less travelled every single day. It’s inspiring and challenging and vulnerable and wonderous all at once.”

print / ebook

print / ebookIt’s early days, but An Unusual Boy is getting traction with five-star reviews on Amazon and Goodreads, and raves from popular authors such as Sally Hepworth, suggesting that Boldwood editor Sarah Ritherdon’s instincts about the novel were sound.

Irrespective of traditional or innovative publishing models, the path to publication remains a long and winding one, with serious questions for aspiring authors to consider at every step. The unusual publication story of An Unusual Boy demonstrates that no matter the publishing road taken, stamina, determination and resilience remain the essential qualities for any author aspiring to see their work published by a third party.

November 11, 2020

Maximizing Book Sales with Facebook and BookBub Ads: Q&A with Melissa Storm

Today’s Q&A is by journalist and romance writer Cathy Shouse (@cathyshouse).

Melissa Storm is a New York Times and multiple USA Today bestselling author of women’s fiction, inspirational romance, and cozy mysteries.

Her latest book, Witch for Hire, was written under her pen name, Molly Fitz, and released in November. Her second book in a series, Wednesday Walks and Wags, released in August from Kensington Books and was an Amazon Best of the Month Selection.

She and her husband and fellow author, Falcon Storm, run a number of book-related businesses together, including LitRing, Sweet Promise Press, Novel Publicity, and Your Author Engine. When she’s not reading, writing, or child-rearing, Melissa spends time relaxing at her home in the Michigan woods, where she is kept company by a seemingly unending quantity of dogs and two very demanding Maine Coon rescues. She also writes under the pen name Mila Riggs.

Cathy Shouse: With so much buzz about the positive impact of online advertising on book sales, will you help sort some facts from myths, specifically when it comes to Facebook and BookBub ads?

Melissa Storm: Learning how to run ads is the second most important thing I’ve done for my author career; the first was learning to write good books! Diving in can be super overwhelming for authors, especially since neither platform has a problem spending all your money whether or not the results are good.

Facebook (FB) has many more moving pieces, but tends to be an easier platform to begin learning. This is in part because FB’s system analyzes the data and helps you optimize. With BookBub ads, there are fewer levers to pull, but you’re completely on your own. Nothing beats BookBub, however, for advertising to non-Amazon retailers—which makes it just as important as Facebook ads if you choose to forego the Kindle Unlimited program.

I suggest picking one platform to become proficient in first before moving on to learn the other. Each has its own quirks and trying to learn them together can be quite confusing!

How can an author optimize their chances of success with ads? It’s often advised not to advertise unless you have more than one book. What do you think?

I believe Facebook ads are the easiest to learn, because if you know how to create a great brand presentation for your book, then you already have a big piece of the puzzle. Often ads work best by using your product description and a cropped version of your book cover art. If those ads don’t convert well, chances are something is off about your branding. Ads can help you identify that and tweak it so you earn better across the board—from newsletters, promo sites, organic discovery, anything!

You can produce a profit when advertising a solo title, but it’s so much easier to make a profit with a series. One tip I have for either Facebook or BookBub ads is to link to your series page instead of a single book. It also helps to have some kind of special offer, like marking the first book down to 99 cents or making it free.

Do you have guidelines to share about ad spending? What about exceeding your budget and not knowing how to staunch the bleeding?

Both BookBub and Facebook have a safety function that many authors don’t know about. For BookBub ads, if you choose CPC (cost per click) bidding and bid low, BookBub will either get you clicks for that amount or it won’t spend your money.

For Facebook ads, under the campaign level, change “Campaign Bid Strategy” from the default “lowest cost” to the secondary option “bid cap.” For authors new to ads, I recommend setting the bid cap at 25 cents. You can move that down as you start to get results. It will take longer to get data this way, but you can also make sure every penny counts!

Do most authors getting started in ads need to take courses to learn how to do it? Or can you hire someone to create ads?

The biggest factor when deciding whether to run your own ads or to hire out is what ads cost you—not just money but factor in your time and also the impact it has on your overall stress level, and how that impacts other aspects of your writing career and life.

If the thought of learning ads sends you into a panic spiral, then hiring out might be for you. Just remember that with a pro, you’re adding the additional cost of their services, and that makes it harder to produce ROI-positive (profitable) ads. That said, ask for recommendations and find someone who not only delivers results you like but openly and consistently and honestly communicates with you. P.S. I offer ad services through my company LitRing.

What are the top three mistakes people make with ads?

Not giving them enough time. Too many authors freak out and turn off the ads while they’re still settling. The data could be lagging a little bit, and you may have turned off an excellent ad.Not adjusting. Ads are not set it and forget it. Even the most evergreen campaigns take a bit of work to get there. I make sure to check my ads daily and turn off any lower performers, so that my money goes to those that work best.Not testing multiple ads or audiences. Data is key with ads and having only one data point with zero context doesn’t tell a very compelling story.

Is it possible to rely too much on ads? Or what about the reverse: if one masters ads, can they slack on the newsletters and social media engagement?

There is no prescription for success, and anyone who tells you otherwise is either looking through the narrow scope of their own experience or is lying to you. My motto when it comes to marketing is “do it first or do it best.” If you hate sending newsletters, your readers will notice. You also can’t be the best at things you don’t enjoy doing, so cut them out of the equation and focus on what you do enjoy—you’ll do it much better.

Just because ads are a crucial part of my success doesn’t mean that the next author can’t be successful without them. It’s one of those things that has huge risks, but huge rewards. I’m willing to gamble with my royalty dollars in the hopes of making more (and almost always I do), but if you’re not, don’t force it. Find your own path. Do what you love.

What are some tips you would you recommend for someone whose ads have produced disappointing results in the past?

The data tells a story, listen to it. Too many authors try to force their way to an ads HEA (Happily Ever After), but the truth is, there’s going to be some conflict and tough times before they run off into the beautiful sunset and make you lots of money forever and ever, amen. Of course, you won’t have very much data to interpret if you’re only running one ad with one audience, as I see so many authors do starting out. Test at least three different ads and five different audiences, so you can compare their performance and do more of what works best!

Would you mind sharing your advertising strategy for your latest indie release? As experienced as you are, is it still more art than science?

My most recent release is Witch for Hire (under my Molly Fitz pen name). I decided last minute that I wanted to launch it to the USA Today Bestseller List, which requires an ad heavy strategy. Of course, launching close to a contentious election makes everything so much harder. Immediately I saw that while my book had some amazing organic launch power, ads were not going to be as easy as they usually are. I had to adjust my strategy as I went and rely more heavily on BookBub ads than Facebook ads. It will be very close as to whether or not I make it. Wish me luck!

November 10, 2020

Emotional Truth and Storytelling: Why It Works and How

Photo credit: rossyyume on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-ND

Photo credit: rossyyume on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-NDToday’s guest post is by national award–winning journalist Robin Farmer (@sonewsy), author of the YA novel Malcolm and Me.

I never fancied myself a fantastic writer. What I do believe I excel at is the ability to capture the emotional truth(s) of a character, scene, chapter, and overall story.

Think about your favorite novels and how they made you feel. Something stirred and lingered, right? You felt—and likely still do—the uncertainty, rage, joy and love that the characters felt. Perhaps your perspective even shifted as a result.

Defining emotional truth

Emotional truth is elusive and difficult to capture. No standard definition exists. Here’s my crack at it: Emotional truth allows readers to feel a certain way about the experiences of people who may lead different lives from them. It’s the lens that allows us to see ourselves in a story that results in a heartfelt connection to a fictional narrative. Emotional truth transcends facts.

What I value most is that emotional truth engenders empathy.

Fostering empathy is the main reason I infuse emotional truth in my work. In these increasingly polarized times, it’s clear empathy is in short supply. Several years ago a report found 40 percent of college freshmen lacked empathy. Reading that left me deeply disturbed. Future leaders need empathy to understand the needs of others. Without it, well…take a look around. Empathetic leaders can build a sense of trust and strengthen their relationships, which can lead to greater collaboration. I’ll leave that here.

I learned the techniques to capture emotional truth during my first fellowship through the Education Writers Association more than twenty years ago. Jon Franklin, author of Writing for Story, served as an advisor to my narrative nonfiction project examining survival tactics of gifted Black students at troubled schools, where being smart carried a stigma. I was intimidated to work with the two-time Pulitzer winner, but he read my three-day series and said, “You got it right.”

How to tap into emotional truth in your story

Here are 10 techniques I use to write with emotional truth.

Be vulnerable. My debut novel, Malcolm and Me, follows a reluctant rebel with the heart of a poet as she navigates a school year fraught with adult hypocrisy. While my protagonist is wounded by a traumatic event involving her Catholic schoolteacher, I knew she couldn’t wallow in pain and self-pity for 272 pages. She doesn’t. She’s funny, often in “good trouble,” and a ball of confusion. Whatever Roberta feels so must my readers. Roberta’s vulnerability was rooted in my teen years. Nothing beats authentic angst.

Mine your secrets. Personal truth feeds the character’s truth. In writing my debut novel, I borrowed the emotional truth about my struggle to forgive, including those I love deeply, and gave it to my protagonist. I could not write that story with authenticity until I dug deep and understood why I had been stuck and what led to a breakthrough. My clarity informed and honed the behavior of my character.

Listen to the “page people.” Just because you created your characters doesn’t mean you know their every move. Sometimes they will surprise you. Let them. Yield to their whims. When they want to be quiet, don’t force them to speak up. Silence can say a lot, too.

Create challenges. Understand what the protagonist and other characters want, then remove it or make it a struggle to obtain. We root for characters we believe in, identify with and want to see succeed. In other words, characters we feel. I once heard someone say that a novel is akin to taking a ride on an amusement park. Readers have purchased tickets and will feel cheated if a ride fails to carry them up and down and make their heart pound.

Balance action. Life is messy and so are people’s reactions to it. But not everything happens at a level 10. Mix big, dramatic moments and scenes with quieter ones, which can also amplify emotional truth.

Cultivate growth. Know the emotional state of your character on page 1 and be clear about the various emotional stages he or she will experience to make it to the end of the story. This growth may not be linear and could include setbacks, but the person must experience changes that feel authentic.

Use your senses. Do you have a song that transports you to your first dance? A perfume or cologne that reminds you of someone no longer alive? Sound, smell, taste and touch evoke powerful emotions to inspire you.

Pick from an “emotional garden.” Collect bits of dialogue, favorite lyrics, phrases, discarded scenes, observations, and reactions—anything that provokes strong feelings and may feed your current or future story. Visit often.

Learn from other writers. Read often. Reading expands your vocabulary and imagination, shows you what works and what doesn’t, and exposes you to diverse worlds. Reading other authors may also inspire you to take risks with your own work.

Revise, rinse and repeat. Emotional truth is an indistinct quality that works when the characters stay with you long after you’ve turned the last page. Weaving it into your work requires patience and practice. Writing is rewriting.

print / ebook

print / ebookI’m big on takeaways. So keep this acrostic handy for how to elevate the emotional tenor of your work:

Embrace the fear of vulnerability.

Mine complexity.

Organize narrative arcs. Be clear about all stages.

Tap into your memories with music and smells—often emotional anchors.

Include powerful emotions with ordinary ones.

Optimize opportunities for a character to accept or reject growth.

Nurture an emotional “garden” of evocative material to inspire you.

Avoid “one note” characters; vary responses.

Listen to the unsaid as much as what’s spoken.

Trust yourself to go deep and transfer what you find to the page.

Read. Read. Read. Read. Read. Read. Read. Read. Read. Read.

Unearth feelings. Great stories reveal how people feel.

Try harder. Get frustrated. Revise. Rinse and repeat.

Have a sense of humor when appropriate.

Defining the emotional truth in stories can be elusive. But the heart of a reader understands it. As a writer, that’s the test we must strive to ace.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out Robin Farmer’s debut YA novel, Malcolm and Me.

November 9, 2020

4 Story Weaknesses That Lead to a Sagging Middle

Photo credit: ce2de2 on Visual hunt / CC BY-NC

Photo credit: ce2de2 on Visual hunt / CC BY-NCToday’s guest post is editor by Tiffany Yates Martin (@FoxPrintEd). Join her on Nov. 18 for the online class Regain Momentum in Your Story Middle.

Is there anything more thrilling for the creative soul than starting a shiny new story? It seduces you effortlessly, promising you a dazzling future, and in the heady flush of new love it feels as if this perfect communion between you will never end.

And then comes the middle of the book.

But when things get tough, that doesn’t mean the story isn’t worth fighting for. Figuring out the problem and resolving it can and should add even more depth and dimension.

When a manuscript loses its momentum, generally the issue is one of several culprits:

The plot has lost its cohesion.The characters aren’t progressing on their arcs.The story stakes have deflated.Tension and suspense have lagged.

Here’s how to spot what may be derailing your story, and ways you can get things back on track.

1. The plot has lost its cohesion.

The best way to spot a sagging middle due to plot is to examine the story’s “bones” to see whether your plot holds together and consistently propels readers along the story arc. My favorite way to do this is to sketch out what I call an X-ray—basically an outline you make after the fact. (Or, for you plotters, repurpose your outline.) It’s a brief list of every single plot event that moves the story forward.

I recommend bullet-point format for this, and it may be one bullet-point event per chapter, or ten—it depends on your story—and each event should be no more than a line or two, around three pages total for the whole story. X-rays take only an hour or so to create, and offer a crystal-clear image of whether and where your plot line might meander or peter out.

Now ask yourself:

Is every plot event a result of an event that preceded it?Does every event inexorably lead to the next?Is each plot event essential to propel the story toward its destination (its resolution)?

If any of these answers are “no,” examine which scenes might be treading water and why—and whether you can fix them or if they can be cut altogether to get the story where it’s going. Maybe you got a little lost in back story, for instance, or taken a plot detour that’s not intrinsic to the central story question. Maybe the story loses direct cause-and-effect sequencing, and becomes episodic.

Try using the South Park creators’ “but/therefore” technique: Does every event connect to the ones preceding and following with “but” or “therefore,” rather than “and then”? You might also try introducing or developing a key subplot, or unexpected new information that deepens and complicates the plot.

2. The characters aren’t progressing in their arcs.

If character development is the culprit, your protagonist may have lost sight of her goals, whether immediate or long-term; what’s driving her may have gone fuzzy; or you’ve forced the characters somewhere they don’t want to go. Ask yourself:

Do each main character’s goals remain clear and strong throughout? Make sure that not only do we see your character’s overarching main goal throughout the story, but that in each scene your protagonist has a clear, strong immediate objective, ideally in service to that overarching goal: Inigo Montoya wants the six-fingered man, but to find him he must rescue and partner with Westley.Do motivations remain strong and clear, both external and internal? Do we know why your character wants each goal, and do we see those reasons vividly and compellingly throughout? Inigo reminds us frequently why he’s so driven toward his goal: The six-fingered man killed his father (and thus should prepare to die).Does this choice or development make sense for the character’s journey, or are you puppet-mastering? Sometimes stories don’t want to go where you want them to. Depending on how they develop, characters’ goals may need to change, or their feelings about them may shift. If you’re shoehorning your characters onto a predetermined path that no longer fits their story, they may rebel and go on strike.

3. The story stakes have deflated.

If readers lose sight of what your protagonist(s) have to gain or lose in the pursuit of their goals, the momentum can drop out of your story. Ask yourself: