Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 80

July 14, 2020

6 Principles for Writing Historical Fiction

Today’s post is by Andrew Noakes (@andrew_noakes), executive editor of The History Quill.

Let’s face it: historical fiction can be a daunting genre to write in. Endlessly fascinating and rewarding, yes. But still daunting.

If you’re diving into this genre for the first time and feeling a little overwhelmed, or if you’re already a historical fiction writer and looking for some guidance to help restore your sanity, then help is on the way. I’ve put together six concrete tips for historical fiction writers—the dos and don’ts of writing historical fiction.

1. Establish your own set of rules for when to bend history for the sake of the story—and stick to them.There are as many opinions on how accurate historical fiction should be as there are historical fiction authors, and they vary widely between those who consider accuracy an optional bonus and those who can be, well, a little bit pedantic. Historical fiction writers tend to get anxious about the possibility of censure if they bend the historical record a little, which is both understandable and healthy, but ultimately you have to tell a good story, and you can’t please everyone.

Rather than worrying about never, ever deviating from history, I advise establishing your own set of rules for when to bend history or not. That way, you’ll be able to make fair and consistent decisions and achieve the kind of balance most readers are looking for. Here are some tips that might help:

There is a difference between altering verifiable facts and filling in the gaps. History is full of mysteries, unanswered questions, and gaps in the record. If what really happened can’t be verified, you have much more freedom to play around with history.History is open to interpretation. As long as you can back up your interpretation through your research, it’s fine to contradict conventional wisdom.Plausibility matters. If you want to bend the historical record, your changes should be plausible. For example, if you want a historical figure to arrive somewhere a few days earlier than they really did, they shouldn’t have been, say, imprisoned or incapacitated at the time.If a historical figure isn’t well known and not a lot has been written about them, you have more room for maneuver than you do if their life has been exhaustively documented. But, if you’re going to make something up, make sure it’s consistent with what you otherwise know about the character, including how they behaved, their interests, and what their values were.If you’re looking for more tips on historical accuracy, do check out The History Quill’s free, official guide to accuracy and authenticity in historical fiction.

2. Do plenty of research—but know what to include and what not to include in your novel.Research is one of the very first steps on your journey to becoming a historical fiction author. Here’s a safety warning: you’re about to dive down a whole load of research rabbit holes. From ancient cutlery to medieval agricultural techniques, there is a lot of stuff historical fiction writers need to know about. Secondary sources are your starting point, but primary sources, particularly letters, newspaper reports, and diaries are also vital.

Don’t be afraid to push the boat out and visit some archives, and, for that matter, do go and visit historical sites relevant to your story if you can. If you want to get really immersed, you can read the fiction of your period, cook the food, or even try and find authentic recreations (or possibly recordings, depending on the era) of the music.

Here’s the thing, though: you’re going to do all of this research, and then you need to discard 95 percent of it. Don’t actually delete your notes, obviously. What I mean is, only a very small fraction of your research should actually make it into your book. The sum total of your research will make the world you create feel real and authentic, and you need to deploy little details carefully and selectively to immerse the reader, but don’t be tempted to show off and dump everything you’ve learned onto the page. Otherwise you’ll end up with a dry tome of a history book, not an engaging historical novel.

3. Include characters who break the conventions and norms of their period—but don’t forget to include context.History is replete with exceptions—people who ignored or rejected social conventions, overcame entrenched political and economic barriers, or challenged the prevailing wisdom of their time. One could argue it would be inaccurate not to include people like this in your historical novel. If every single one of your characters perfectly encapsulates the prevailing culture of their time, then you lose the change, difference, and non-conformity that have always been just as much a part of history.

Most of the trouble with depicting non-conformist characters comes when their non-conformity is represented as normal rather than exceptional. To persuade the reader that your anomalies are authentic, you must provide context. That means showing the obstacles, conflict, and ostracization your characters face. By doing this, you’re implicitly recognizing that they are unusual for their time, while persuading the reader they are nonetheless as real as any other part of the story.

4. Don’t write like you’re in the 14th century.One of the ironies of writing historical fiction is that, in many cases, your dialogue should actually not be historically accurate. If you’re wondering why I would say such a profane thing, this is the reason:

Aleyn spak first, “Al hayl, Symond, y-fayth;

How fares thy faire doghter and thy wyf?”

“Aleyn! welcome,” quod Symond, “by my lyf,

And John also, how now, what do ye heer?”

These lines are from The Canterbury Tales by Chaucer, written in the late 14th century, and I often use them to remind people just how different the language was back then. If you have your characters speaking to each other like this, most readers will put your book down in five seconds flat.

At the same time, historical fiction readers often really hate it when modern-day language creeps into historical fiction, which leaves us caught between a rock and a hard place.

The answer to this conundrum lies in a literary sleight of hand. We must create the impression of accuracy while ensuring the language remains readable and enjoyable. To do this, writers have to avoid modern colloquialisms and keep most of the language neutral, using words that, in some form or another, feel equally at home in history as they do in the modern day. Then you must add some more archaic words and constructions into the mix—not so much as to overwhelm the reader, but just enough that the story feels of a different time. The type of archaic language you select is important here—they have to be words and phrases that are still recognizable, even if they are no longer commonly used. This is an intricate task, but it can also be a fun and rewarding one once you get into the rhythm.

Historical language obviously becomes less alien the closer you get to the modern day, but even 19th century language was sufficiently different that it must be tempered for a modern reader to some degree.

5. Integrate the history seamlessly into the story.In A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens portrays a French aristocrat in his carriage running over a child on the street, before tossing a coin to the devastated father and driving off. The scene perfectly encapsulates the sentiments and forces that generated the French Revolution.

When it comes to striking a balance between history and story, this scene shows us the way. The cold indifference of the aristocratic class, the inequality not only in wealth but in the application of justice, and the debasement of the common person’s humanity all live and breathe in these lines. And yet the scene does not impassively summarise the causes of the French Revolution. Instead, the history is integrated into the story, and Dickens dishes out a history lesson without us even realizing it.

Dedicating large chunks of your story to outlining historical context through exposition or focusing on historical details purely for their own sake will quickly test your reader’s patience. Instead, follow Dickens’ lead and think about how you can illustrate history rather than exhaustively describing it, and try and integrate the smaller details organically. That means not sending your character off to a banquet purely so you can show off all the historical cuisine you researched or into an armory just so you can list all the weapons. Details like this have to fit naturally around the plot, not the other way around.

6. Don’t insist on accuracy if it will cause disbelief (but here’s a workaround if you really must).A paradox of writing historical fiction is that sometimes accuracy must be sacrificed for the sake of authenticity. When you come across something that really happened in history but is just too ludicrous for the modern day reader to believe, often it’s better to leave it out. Like it or not, the impression of accuracy matters more than actual accuracy if you want to tell a story that will be well received.

If there’s some facet of history that you simply must include in your story but you’re concerned the reader won’t believe you, there is one way to gently disarm them: introduce their scepticism into the story. Depict at least one character finding it just as unbelievable as you think the reader might, and then depict another character putting them right. This is a subliminal nudge to the reader acknowledging their scepticism and reassuring them that, yes, this really was a thing. In a pinch, this can work.

So, those are my dos and don’ts of writing historical fiction. If you’re thinking about giving the genre a try or you’ve already started and feel like you’re out of your depth, I hope this guidance will help you move forward with confidence. No one with any sense ever said writing is easy, and historical fiction can be a trickier genre to master than some, but it’s worth every bit of perseverance.

July 13, 2020

Amazon Editorial Reviews: Are You Using This Incredible Section?

Today’s guest post is by Dave Chesson (@DaveChesson) of Kindlepreneur.

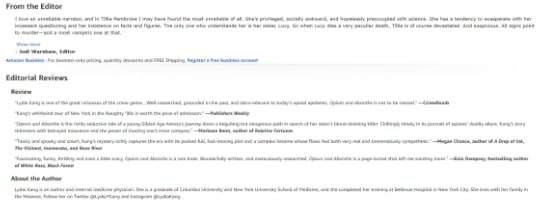

Amazon editorial reviews are one of the most underrated tools in a self-publishing author’s arsenal—that’s because most authors either don’t know what they are or how to access them. Editorial reviews are book evaluations that are usually written by an editor or expert in the book’s genre or field. You can find them on your book’s sales page, just above the About the Author section.

Why are these editorial reviews so important? They’re a legit form of social proof on your book’s sales page.Editorial reviews are NOT Amazon reviews and thus do not follow Amazon review rules.You can reach out to just about anyone to get an editorial review.As you’ll see a little later on in this article, a lot of readers check out the editorial reviews before they decide to buy—along with your blurb, cover and look inside, editorial reviews are one of the factors that help readers decide whether your book is worth their time or not.

Why are these editorial reviews so important? They’re a legit form of social proof on your book’s sales page.Editorial reviews are NOT Amazon reviews and thus do not follow Amazon review rules.You can reach out to just about anyone to get an editorial review.As you’ll see a little later on in this article, a lot of readers check out the editorial reviews before they decide to buy—along with your blurb, cover and look inside, editorial reviews are one of the factors that help readers decide whether your book is worth their time or not.With all that said, it’s pretty surprising that more authors aren’t taking advantage of this editorial review section. Let’s take a look at how you can access the editorial review section and upload your reviews.

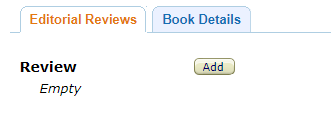

How to Create an Editorial ReviewTo access your editorial review section and enter your editorial reviews, simply follow these steps:

Head over to Author Central and login to your account.Navigate to the Books tab. Select the book for which you want to edit the review section.Here, you’ll find you can edit several areas: Review, Product Description, From the Author, From the Inside Flap, From the Back Cover, and About the Author.

Select the book for which you want to edit the review section.Here, you’ll find you can edit several areas: Review, Product Description, From the Author, From the Inside Flap, From the Back Cover, and About the Author. Hit the Add button.You’ll be given a text box to add reviews and general guidelines for adding them according to Amazon’s specifications. You can add them in the text editor or use the HTML tab to make your reviews look smart using HTML codes.

Hit the Add button.You’ll be given a text box to add reviews and general guidelines for adding them according to Amazon’s specifications. You can add them in the text editor or use the HTML tab to make your reviews look smart using HTML codes. Once you’ve added your review, simply hit Preview, then Save Changes and you’re all set!

Once you’ve added your review, simply hit Preview, then Save Changes and you’re all set!

Now that you know how to upload your editorial book reviews, you might be wondering where to get reputable reviews. It’s no use entering editorial reviews that don’t make sense or don’t offer good social proof for the reader.

Where to Get Editorial ReviewsYou might be a little worried about where to source your editorial reviews. Well, I’ve got some good news for you. Pretty much anything and everything is allowed in the editorial reviews section.

That’s because editorial reviews and customer reviews are two completely separate things. Customer reviews are written by people who have bought your book and is thus a fiercely guarded component of Amazon. Whereas editorial reviews are written by people who’ve received your book and agreed to do a review for you. A really nice one because you can choose what you put there.

The only things Amazon lists to avoid in Editorial Reviews are:

Phone numbers, addresses, or URLsTime-sensitive statements or statements specific to one edition or listingAdvertisements or promotional materialAvailability, price, or alternative ordering/shipping informationProfanity or spiteful remarksObscene or distasteful contentThat’s it!

They’re basically testimonials, and you’re allowed to ask just about anyone to give one for your book—from professional reviewers to your own family members.

Obviously, you’ll want the best possible editorial reviews. I’d advise that you get reputable bloggers or websites to offer you a review, and to ensure that they’re in-line with your genre.

Here are a few tips for finding editorial reviewers:

Look for recognizable domain names in your genre like TopSciFiBooks.com if you’ve written a sci-fi book, for instance—and reach out for a review.Find other authors in your genre or niche and ask them to read your book and give a testimonial.Approach reputable online magazines.Pay a professional reviewer to read your book and give you a testimonial—you could even use Fiverr for this.Remember to grab a 1–2 sentence snippet from each of these sources and to credit them when uploading them to your review section.

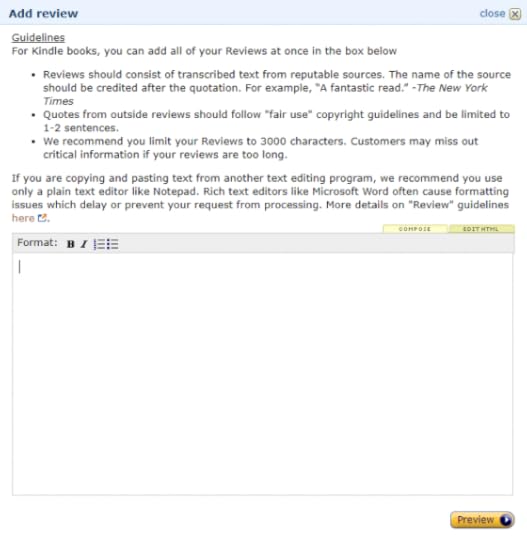

Once you have your reviews, you might be tempted to put them up right away–but the design of your review actually matters. So, let’s take a look at how your review should be structured so you can better take advantage of them.

How to Design Editorial Reviews on Your PageBelow, you’ll find a heat map image that was taken from shoppers on Amazon using a camera that tracked exactly where their eyes would go on the page and where they clicked. The results are pretty amazing and give some great insight into how shoppers make their buying decisions and which information is most important to them.

Check it out:

We noticed the following important fact about these shoppers:

Most people don’t actually read the quote. Instead they focus more on who said it, or their qualifications.

What does that mean for authors?

Well, that they should probably be italicizing their quote and bolding the qualifier. What I mean about a “qualifier” is what would the shopper know. If the person is famous, then bold their name. However, if they aren’t then bold that which makes them pertinent or “qualified” to speak on your book.

For example, if the person who’s given you your editorial review is an author in your genre but isn’t super famous, then the qualifier that you would bold would be “Bestselling author in [genre].” That statement would mean more than the author’s name. If you used a review blog, however, the qualifier is the domain name, not the individual reviewer, especially if that domain name applies to your genre. Like TopSciFiBooks.com applies to sci-fi or Tor.com applies to fantasy.

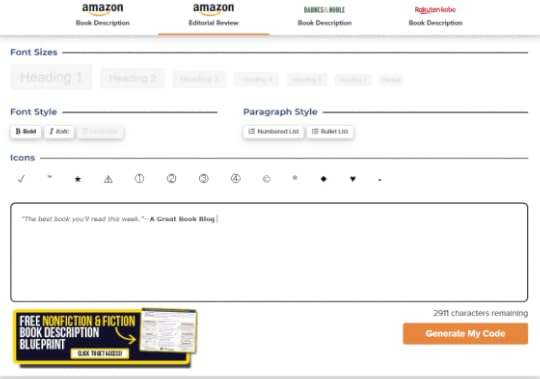

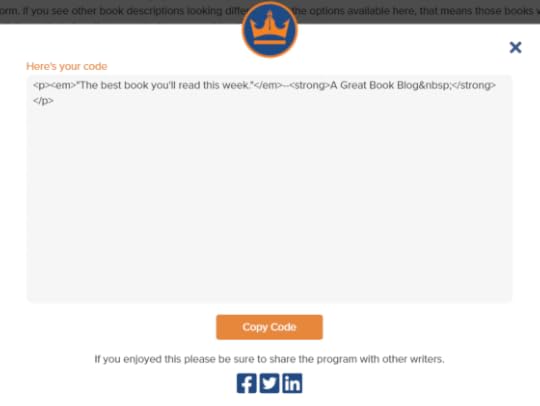

So, if you want to stand out, you need to design your reviews for success. But how do you do that? By using the HTML tab in your review section and using a handy tool I designed for just this purpose.

The Kindlepreneur Book Description Generator allows you to design your editorial reviews and download the HTML code you’ll need to input directly into your HTML tab of the review section for your book in Author Central.

Check it out.

I simply navigate to the Editorial Review Generator, input my text, and play around with it until I have exactly what I want. After that, I simply hit Generate My Code.

And there you have it. I can take this code and upload it directly to Author Central.

So, remember to source those editorial reviews, format them, and take advantage of this section that too many authors ignore.

July 9, 2020

Making the Switch from Nonfiction to Fiction: Q&A with Kate White

Today’s Q&A is by journalist and romance writer Cathy Shouse (@cathyshouse).

Kate White (@katemwhite) is the New York Times bestselling author of fourteen novels of suspense; six standalone psychological thrillers, including Have You Seen Me? (2020); and eight Bailey Weggins mysteries.

For fourteen years she served as the editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan magazine, and though she loved the job (and all the freebies to be found in the Cosmo beauty closet!), she decided to leave eight years ago to concentrate full time on being a suspense author.

Her first mystery, Even If It Kills Her, was a Kelly Ripa Book Club pick and No. 1 bestseller on Amazon. Her most recent Bailey Weggins mystery, Such a Perfect Wife, was nominated for an International Thriller Writer Award.

Recently, Kate answered questions via email about how she morphed into being a fiction writer from a long career as a nonfiction editor and writer.

Cathy Shouse: Many writers dream of writing novels but enter into the field through nonfiction writing. Tell us about your unique introduction to professional writing.

Kate White: The entire time I was growing up, I had a huge desire to write plays and novels, especially mysteries (Yup, I was a Nancy Drew fanatic), and I also loved putting out my own little magazine in high school. I had no idea, though, how to break into any of those areas. My senior year in college I won the Glamour magazine Top 10 College Women contest and appeared on the August cover. Because of my introduction to the Glamour staff, I knew I had a decent shot at getting a job at the magazine. A particular lane of writing suddenly opened up in front of me and I followed it, leaving the other areas of interest behind.

I started as an assistant at Glamour and advanced from there, eventually becoming a full-time feature writer. I ended up writing the first personal essays the magazine ran. Mine were about being single in New York. Ha, my articles were popular but did not become an HBO series.

From that point on I was firmly in the world of nonfiction. I became the editor-in-chief of five different magazines, including Cosmopolitan, and also wrote several nonfiction books. But I still had a secret dream to write fiction.

Your name first came onto my radar in the mid-90s when my employer supplied all the women with your book, Why Good Girls Don’t Get Ahead but Gutsy Girls Do (updated in 2018 as The Gutsy Girl Handbook: Your Manifesto for Success). When you became so successful with nonfiction, were you tempted to stick with what was working?

I loved being an editor-in-chief and I also really enjoyed writing nonfiction. One of the magazines I ran was Working Woman, a really terrific magazine for women in the workforce, and I found it exciting to write about career strategies and leadership secrets, to guide women at a time when they were moving in huge numbers into the workforce. And it was very reinforcing, too. Why Good Girls Don’t Get Ahead not only became a Wall Street Journal bestseller, but it was also considered a bible at the time by many women. My agent encouraged me to keep at it.

But, as I said, I never lost the yearning to write a novel, which I’d tried a few times unsuccessfully over the years.

During the time I was running Redbook magazine, a woman pitching a horoscope column asked to read my palm and she told me, “You love this office but you would also love to be in a little space all by yourself doing something very creative.” I used that crazy experience as a kick in the butt. If I was going to write fiction, I had to do it before I ran out of time.

I wrote four chapters of a mystery novel about a true crime reporter named Bailey Weggins, who freelanced for a top women’s magazine based in Manhattan. I should add that it really helped to recognize that suspense was the right genre for me, not women’s fiction, which I’d attempted before.

I was just getting ready to show it to my agent when I was offered the position of new editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan magazine. I was, of course, thrilled to be offered the job, but I knew I would never be able to write a novel while I was taking on such a huge responsibility. I said yes and stuck a printout of the four chapters in a drawer for the next five months—but eventually came back to it.

I heard one agent say it is a disadvantage to be a nonfiction author and go into novels, although it seems fairly common. What do you tell a journalist or nonfiction writer who expresses interest in writing fiction?

Let me start with the pluses first. Writing nonfiction trains you to pay attention to details and to be an efficient and effective researcher, skills you need for writing mysteries and thrillers. And if you work full-time at a job that involves nonfiction, you’ve probably learned to be darn good at handling writer’s block. When there are deadlines at a magazine, for instance, you don’t get to say, “I haven’t heard from my muse today.” You just write and edit, and if you feel it sucks a little, you probably have time later—like when it’s in a first pass—to tweak.

And it’s possible that writing a nonfiction book first—or making a name for yourself with nonfiction articles—could give you an edge when it comes to both getting an agent and securing a contract for a novel.

My agent [who sold the nonfiction book] suggested we try to sell the mystery with simply a proposal, an outline, and four chapters, and she thought it was only fair to offer it first to my Good Girl publisher, even though we suspected they would pass. To our surprise they bought the book, If Looks Could Kill, as well as a second unwritten mystery, based solely on the material I presented. And they gave me a great advance. This was due in part to the fact that they had a prior relationship with me. They knew from experience that I was reliable and easy to deal with, and that I could be counted on to deliver a full manuscript in a year.

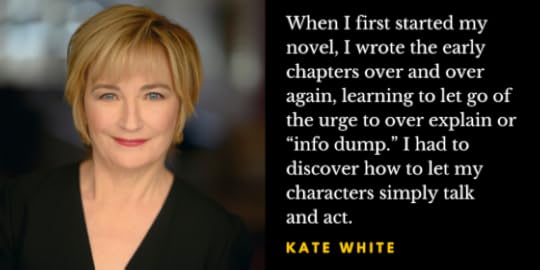

Now here’s the negative. Fiction writing is so different than nonfiction writing. When I first started my novel, I spent a huge amount of time not only trying to be better at writing fiction but also unlearning some of my skills as a magazine writer. They hampered me.

What methods did you find most helpful for making the switch? Did you have a point where you wondered if you could make it happen?

I believe that old adage that nonfiction writing is about telling and fiction is about showing, and I really had to work hard at burning off the need to tell. When I first started my novel, I wrote the early chapters over and over again, learning to let go of the urge to over explain or “info dump.” I had to discover how to let my characters simply talk and act. In a nutshell, the difference between showing and telling is writing, “She smiled,” instead of, “She smiled, feeling happy.”

I never thought I couldn’t do it, but there were plenty of times in the beginning when it was really frustrating. If you make the transition, it’s important to accept that you’re on a learning curve and need to be very patient with yourself.

Here’s what I feel it comes down to: I really think you have to get up one day, put on your author pants, and decide to stop treating the idea of writing a novel as a fantasy. Just do it. Plenty of people have confided in me that they want to write fiction, but they make the mistake of only dabbling, writing during vacations or when they have free moments here and there.

I wrote eight mysteries and thrillers when I was at Cosmo. It wasn’t easy, but many novelists start when they have a day job. I would take my kids to school on the early side (the school had actually opened and there were teachers in the room, I swear!) and then write for a solid hour before my staff arrived at the magazine. On weekends I got up before my kids and wrote for two hours early in the morning. That’s not a lot of time but I forced myself to do what I called “deep work” and really concentrate. It also helped to set a goal of a certain number of pages for each week day (two) and each weekend day (four). The pages added up.

You have to decide to be all in and really put in the time.

I’ve read that Anna Quindlen would write her column one day and her novel the next, not attempting both on the same day.

I think you have to find the system that works for you personally. I can write nonfiction anywhere, any time of day, but for some reason the only time I can compose fiction is in the morning.

When I decided to commit to writing fiction, I was worried I would end up avoiding the task since I had a pretty full plate. So I used a time management technique that I had learned called “slice the salami.” We often avoid important tasks not because we don’t want to do them but because we make them so daunting. The idea is to slice these big tasks down into really small, manageable slices, as small as we need. I thought a lot about how small my daily slice should be for me to be willing to approach it. And I decided 15 minutes. I knew that if I told myself I had to write for only 15 minutes a day in the beginning, I would be able to pull it off. And so that’s what I did. Over time I was able to greatly expand.

So try slicing the salami. Crazy but it works.

How would you describe your genre?

I think of my Bailey Weggins mysteries as amateur sleuth procedurals with a strong whodunit element and also with an irreverent sense of humor. They’re not cozies, though—because Bailey finds herself in some pretty dangerous situations. My standalones are psychological thrillers. They are edgy and I hope really scary, and since there are plenty of twists and lots of misdirection, they play with your mind. I’ve really enjoyed writing both genres.

I’ve tried to stick as much as possible to what I know. Bailey Weggins is a true crime writer for magazines and now mostly websites, and that’s a world I know, of course. The characters in my standalones have jobs that touch on realms I’m familiar with from my magazine career, such as marketing. Or jobs close friends have—and I’m able to really pump them for information.

Today, do you consider yourself primarily a novelist? I’ve noticed your newsletter promotes nonfiction releases (when they occur) and fiction releases, and wondered how you handle promoting both?

It’s funny you ask that because a year or so ago, I made a big decision on that front.

When I decided to leave my job running Cosmopolitan, it was to be my own boss, and I planned to have a kind of bifurcated writing life. I was going to write nonfiction career books and speak on leadership at companies and conferences and also continue to write suspense fiction.

As my going away present from Cosmo, my boss paid my way to the Harvard Business School’s executive education division’s Women’s Leadership Forum, something I was dying to do. Each morning before classes started, groups of around six of us would work as a team with an executive coach. It was as if we all had a small board of advisors and the purpose was to help us each deal with one important question in our careers.

My question: Should I really have this bifurcated career, or should I instead focus on just one type of writing? I explained that I loved doing both.

Well, everyone but one in my group, including the wonderful coach, told me “Do both. You love both, so why not?” Only the Turkish banker had a different view. “Do one,” she said.

Well, I ended up doing both for seven years. I loved sharing career strategies with women and being a public speaker. And I loved being a suspense novelist. But about a year ago I began to realize that it wasn’t really working to serve two masters. There weren’t enough hours in a week to really give my all to each area, particularly with the explosion of social media and all the hours it demands of our time professionally as writers, whether fiction or nonfiction.

I think it’s fine to have a multi-faceted life as a writer if those facets are related and serve each other. Lisa Scottoline writes both suspense novels and humorous essays, which are later published in book form. The essays fit in wonderfully with her career as a novelist because readers are eager to know more about her. But my two worlds were really like apples and oranges, and neither served the other. I even suspect the career expert aspect of my life might have negatively impacted the suspense writing part, making it appear as if I wasn’t all in with being a novelist.

So last year I made the decision to give up the career expert side. And oh, it’s been exhilarating to just be able to concentrate on one thing. Plus, a couple of nice successes happened for me in the last several months—being nominated for an International Thriller Writer Award, having my latest novel sell to the UK (though I’ve sold fiction in a bunch of countries, I’ve never cracked the UK before). I can’t actually trace these things back to my decision, but in some ways it felt like the universe was rewarding me for choosing to be faithful to one lover going forward.

July 8, 2020

How Do Publishers Decide Which Books to Bet On?

Today’s guest post is excerpted from So You Want to Publish a Book? by Anne Trubek (@atrubek), founder and publisher of Belt Publishing.

Each book a publisher launches is its own miniature, stand-alone start-up. Every book is a gamble. Publishing could have a game table on the floor of a Vegas casino, nestled between blackjack and roulette. Bet on which title will earn out, and which will fail. When a title doesn’t break even, the casino swipes the chips off the table. But when a bet wins, it can make up for all those losses. A few bestsellers can support a press despite many money-losing titles.

So how do publishers decide which books to bet on? There’s lots of risk involved when you take a look at a few words sent via email and decide that those words might, in one to three years, end up selling enough copies to earn back the money that you spent to make those words into a book, and then earn a little more so the publisher can take a little bit of money home herself.

Publishers ask two main questions, and they’re the same two questions any capitalist or gambler asks: how much should we stake, and how much might we profit?

To answer those questions, most publishers do a ridiculously complicated set of projections on a profit and loss spreadsheet (P&L). This process involves guesswork into a number of different categories: how much a book will cost to print, how many copies will sell, how many ordered copies will be returned, how much the author will receive in an advance, what the list price will be, what trim size it will have, how much money it will take to market and publicize the book, whether it will be hardcover or paperback, if it will appeal to distributors who help sell the title to accounts like Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and independent booksellers.

Some of these numbers are based on actual data, some are good estimates, and some are inferences based upon past experience. But most of them are magical fairy dust wishes. A P&L is basically a work of fiction, make-believe cells that tally up all the costs and revenue for a project that will not hit the market for another few years. It makes the decision to publish a book look more like a sound business plan than a gut instinct that a little ball will fall on number thirty-one on the wheel, but in truth, roulette may be a good metaphor. It’s silly, really, but it’s the practice of the industry.

Complex and chance-centric as they are, P&Ls provide crucial insight into the business of books. Even if they are often inaccurate or useless for publishers, they are key for anyone interested in the cogs of the industry, and those who assume publishers de facto profit from the labor of writers.

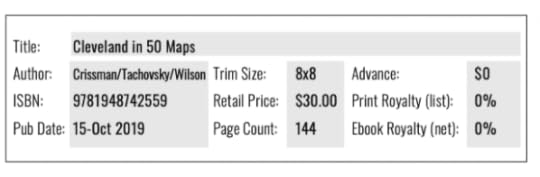

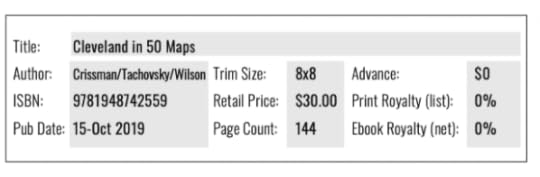

Allow me to walk you through one Belt Publishing P&L that we created to decide whether or not to publish a book called Cleveland in 50 Maps. I have fudged some of the numbers so I don’t reveal the actual pay for various contractors, but the whole is still pretty accurate. I also chose a title that was written in-house by staff, which means there were no royalties or advances. We also entered these numbers before we had a manuscript, or a printer quote, or any of the numbers we entered into the cells. We simply guessed. Like I said, a P&L is a work of fiction.

In the top section, we entered our prospective trim size, list price, publication date, and page count for the book.

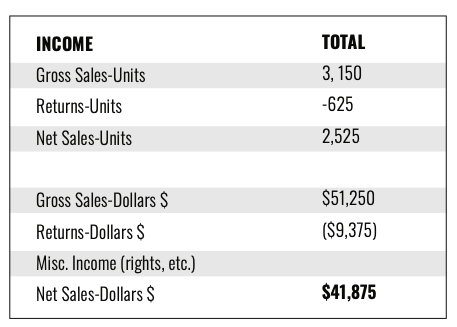

Then we made up some sales numbers—this was one year before the book actually went on sale. We guessed our distributor would order 2,500 copies for this book. Of those, only 1,875 would actually be sold because of the dreaded returns system. (Any book can be returned by a store or distributor to the publisher for full credit.) We hoped for a robust 600 copies that we would sell directly to consumers because we are based in Cleveland and have a lovely crew of fans who understand how important direct sales are to our business model. Under that number we excitedly entered zero returns. Then we added a modest number of ebook sales. (This title is heavy with graphics, and ebooks are notoriously graphic unfriendly.) Usually royalties and advances would be entered here as well, but this book was a special case in that regard, and our costs were lower here as a result. You can see where we would have entered them in the column reserved for advances and royalties above.

According to this model, we would net about $42,000 in sales from this title. Eventually. There is no timeframe on this P&L; it covers the life of the book. Most sales occur in the first ninety days after publication, but a book that becomes a strong backlist title can continue to sell well, if at a slower pace, for years afterward. For Belt’s cash flow purposes, we want to hit our net sales number about twelve months after publication, which is about twenty-four months after we create the initial P&L.

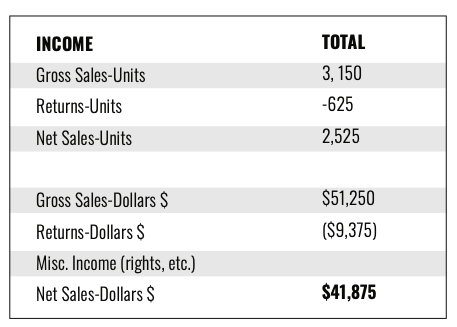

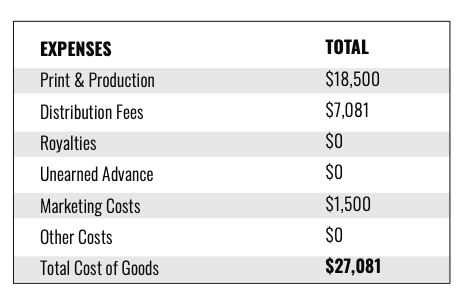

But wait: that $41,875 figure isn’t profit. It’s simply the sales. We still need to count up our expenses, estimating what the book will cost us to make and sell.

The single largest production expense for most books is printing. Paper is expensive! In our P&L, we estimated that this full-color, hardback book of 150 pages would cost $10,000 if we printed 3,000 copies, or about $3.33 per copy. This is a much higher per-unit cost than our more common 200-page paperbacks, which cost between $1 to $2 per unit.

Cleveland in 50 Maps also had a higher retail price of $30, compared to the $16.95 we usually charge for our paperbacks. We estimated that our distributor, who helps us sell copies, would receive about $7,000 for their work on our behalf. (Remember: these are not real numbers, but accurate ballpark estimates. The amount a distributor charges a publisher cannot be revealed publicly.) We added another $1,500 to our production expenses to publicize the book—sending press releases to local media and bookstores to let them know about it and organizing events to promote and celebrate the title.

But wait—there are more expenses! We have to pay an editor, a copyeditor, a proofreader, a cover designer, an interior designer, and others who contributed to the book. We also need to figure in the cost of securing permissions for images. If we are going to make advance copies of the book to send to media and booksellers, we also need to add in those costs, as well as the postage required to ship them.

Below, you can see the hypothetical costs for all of these components of book production. Note that the P&L doesn’t include the costs of a publisher (me!), or office space, or the labor to ship copies. These are considered overhead and might be included in a flat percentage at other publishing houses. But to keep my explanation as simple as possible, I have not included those.

Add all of those numbers together and the total projected cost to bring Cleveland in 50 Maps to readers is $27,081. And if all these numbers prove true, we will make a profit of $14,794, a 35 percent margin.

Again, this was all conjecture when we initially created it. But it turned out to be fairly accurate to reality. This is not always the case. Some P&L projections wildly diverge from actual P&Ls. The single key factor is sales. If we had projected we were going to sell 3,000 copies of Cleveland in 50 Maps and only sold 200, we would have lost money. And this often happens. As I mentioned earlier, conventional wisdom says it happens about 80 percent of the time.

But once in a while—oh, say, one out of five times—a book’s sales far outstrip expectations. Books that sell far more than projected are the backbone of publishing. For example, pretend that instead of $14,000, we netted $100,000 from Cleveland in 50 Maps. Every title holds within it that possibility (as opposed to, say, a restaurant serving steak: it might make profit from every filet mignon it sells, but it will never sell just one steak that quadruples that profit.) And in publishing, that one jackpot can cover many bad bets.

The ability to bet more money on more books is a key difference between independent presses and conglomerate ones. Usually, a conglomerate press can bet a $100,000 advance to an author three years before a manuscript is due, and five years before the book will be published, in the hopes that it might sell enough to profit the company $1,000,000 another two years after that, when the money from sales actually comes in. If they lose the bet, they can write off that advance, and all the other expenses, as a loss. Usually, though, an independent press can neither wait that long nor risk that much money.

For authors with contracts for conglomerate houses, the advantage is that they receive more money up front. But the disadvantage, more often than not, is that failure is built into the deal—most authors will never sell enough copies to receive royalties after the book is released. With independent presses offering smaller, more realistic advances, chances increase that an author might outstrip expectations and receive royalties.

Basing all your business decisions on spreadsheets that are created years before any of the actions the numbers signify occur may not be the healthiest or most accurate method. And at Belt, we regularly make decisions based on non-P&L factors; often, we skip this step entirely. Sometimes, we publish a book because the staff thinks it would be really fun to do so, or it is right up our alley interest-wise, and even if we may not profit, we likely will not lose money on it. Often, we “take a flyer” on a book by an author with no platform or previous publication track record, but who writes such a compelling proposal we want to give them a chance. Other books just seem so “Belt-y”—they represent exactly why we decided to start the press—because they tell an untold regional history or because they are intellectually rigorous without being pedantic—that we have to publish them to stay true to who we are.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, be sure to get a copy of So You Want to Publish a Book? by Anne Trubek.

How Do Publishers Decide What Books to Bet On?

Today’s guest post is excerpted from So You Want to Publish a Book? by Anne Trubek (@atrubek), founder and publisher of Belt Publishing.

Each book a publisher launches is its own miniature, stand-alone start-up. Every book is a gamble. Publishing could have a game table on the floor of a Vegas casino, nestled between blackjack and roulette. Bet on which title will earn out, and which will fail. When a title doesn’t break even, the casino swipes the chips off the table. But when a bet wins, it can make up for all those losses. A few bestsellers can support a press despite many money-losing titles.

So how do publishers decide which books to bet on? There’s lots of risk involved when you take a look at a few words sent via email and decide that those words might, in one to three years, end up selling enough copies to earn back the money that you spent to make those words into a book, and then earn a little more so the publisher can take a little bit of money home herself.

Publishers ask two main questions, and they’re the same two questions any capitalist or gambler asks: how much should we stake, and how much might we profit?

To answer those questions, most publishers do a ridiculously complicated set of projections on a profit and loss spreadsheet (P&L). This process involves guesswork into a number of different categories: how much a book will cost to print, how many copies will sell, how many ordered copies will be returned, how much the author will receive in an advance, what the list price will be, what trim size it will have, how much money it will take to market and publicize the book, whether it will be hardcover or paperback, if it will appeal to distributors who help sell the title to accounts like Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and independent booksellers.

Some of these numbers are based on actual data, some are good estimates, and some are inferences based upon past experience. But most of them are magical fairy dust wishes. A P&L is basically a work of fiction, make-believe cells that tally up all the costs and revenue for a project that will not hit the market for another few years. It makes the decision to publish a book look more like a sound business plan than a gut instinct that a little ball will fall on number thirty-one on the wheel, but in truth, roulette may be a good metaphor. It’s silly, really, but it’s the practice of the industry.

Complex and chance-centric as they are, P&Ls provide crucial insight into the business of books. Even if they are often inaccurate or useless for publishers, they are key for anyone interested in the cogs of the industry, and those who assume publishers de facto profit from the labor of writers.

Allow me to walk you through one Belt Publishing P&L that we created to decide whether or not to publish a book called Cleveland in 50 Maps. I have fudged some of the numbers so I don’t reveal the actual pay for various contractors, but the whole is still pretty accurate. I also chose a title that was written in-house by staff, which means there were no royalties or advances. We also entered these numbers before we had a manuscript, or a printer quote, or any of the numbers we entered into the cells. We simply guessed. Like I said, a P&L is a work of fiction.

In the top section, we entered our prospective trim size, list price, publication date, and page count for the book.

Then we made up some sales numbers—this was one year before the book actually went on sale. We guessed our distributor would order 2,500 copies for this book. Of those, only 1,875 would actually be sold because of the dreaded returns system. (Any book can be returned by a store or distributor to the publisher for full credit.) We hoped for a robust 600 copies that we would sell directly to consumers because we are based in Cleveland and have a lovely crew of fans who understand how important direct sales are to our business model. Under that number we excitedly entered zero returns. Then we added a modest number of ebook sales. (This title is heavy with graphics, and ebooks are notoriously graphic unfriendly.) Usually royalties and advances would be entered here as well, but this book was a special case in that regard, and our costs were lower here as a result. You can see where we would have entered them in the column reserved for advances and royalties above.

According to this model, we would net about $42,000 in sales from this title. Eventually. There is no timeframe on this P&L; it covers the life of the book. Most sales occur in the first ninety days after publication, but a book that becomes a strong backlist title can continue to sell well, if at a slower pace, for years afterward. For Belt’s cash flow purposes, we want to hit our net sales number about twelve months after publication, which is about twenty-four months after we create the initial P&L.

But wait: that $41,875 figure isn’t profit. It’s simply the sales. We still need to count up our expenses, estimating what the book will cost us to make and sell.

The single largest production expense for most books is printing. Paper is expensive! In our P&L, we estimated that this full-color, hardback book of 150 pages would cost $10,000 if we printed 3,000 copies, or about $3.33 per copy. This is a much higher per-unit cost than our more common 200-page paperbacks, which cost between $1 to $2 per unit.

Cleveland in 50 Maps also had a higher retail price of $30, compared to the $16.95 we usually charge for our paperbacks. We estimated that our distributor, who helps us sell copies, would receive about $7,000 for their work on our behalf. (Remember: these are not real numbers, but accurate ballpark estimates. The amount a distributor charges a publisher cannot be revealed publicly.) We added another $1,500 to our production expenses to publicize the book—sending press releases to local media and bookstores to let them know about it and organizing events to promote and celebrate the title.

But wait—there are more expenses! We have to pay an editor, a copyeditor, a proofreader, a cover designer, an interior designer, and others who contributed to the book. We also need to figure in the cost of securing permissions for images. If we are going to make advance copies of the book to send to media and booksellers, we also need to add in those costs, as well as the postage required to ship them.

Below, you can see the hypothetical costs for all of these components of book production. Note that the P&L doesn’t include the costs of a publisher (me!), or office space, or the labor to ship copies. These are considered overhead and might be included in a flat percentage at other publishing houses. But to keep my explanation as simple as possible, I have not included those.

Add all of those numbers together and the total projected cost to bring Cleveland in 50 Maps to readers is $27,081. And if all these numbers prove true, we will make a profit of $14,794, a 35 percent margin.

Again, this was all conjecture when we initially created it. But it turned out to be fairly accurate to reality. This is not always the case. Some P&L projections wildly diverge from actual P&Ls. The single key factor is sales. If we had projected we were going to sell 3,000 copies of Cleveland in 50 Maps and only sold 200, we would have lost money. And this often happens. As I mentioned earlier, conventional wisdom says it happens about 80 percent of the time.

But once in a while—oh, say, one out of five times—a book’s sales far outstrip expectations. Books that sell far more than projected are the backbone of publishing. For example, pretend that instead of $14,000, we netted $100,000 from Cleveland in 50 Maps. Every title holds within it that possibility (as opposed to, say, a restaurant serving steak: it might make profit from every filet mignon it sells, but it will never sell just one steak that quadruples that profit.) And in publishing, that one jackpot can cover many bad bets.

The ability to bet more money on more books is a key difference between independent presses and conglomerate ones. Usually, a conglomerate press can bet a $100,000 advance to an author three years before a manuscript is due, and five years before the book will be published, in the hopes that it might sell enough to profit the company $1,000,000 another two years after that, when the money from sales actually comes in. If they lose the bet, they can write off that advance, and all the other expenses, as a loss. Usually, though, an independent press can neither wait that long nor risk that much money.

For authors with contracts for conglomerate houses, the advantage is that they receive more money up front. But the disadvantage, more often than not, is that failure is built into the deal—most authors will never sell enough copies to receive royalties after the book is released. With independent presses offering smaller, more realistic advances, chances increase that an author might outstrip expectations and receive royalties.

Basing all your business decisions on spreadsheets that are created years before any of the actions the numbers signify occur may not be the healthiest or most accurate method. And at Belt, we regularly make decisions based on non-P&L factors; often, we skip this step entirely. Sometimes, we publish a book because the staff thinks it would be really fun to do so, or it is right up our alley interest-wise, and even if we may not profit, we likely will not lose money on it. Often, we “take a flyer” on a book by an author with no platform or previous publication track record, but who writes such a compelling proposal we want to give them a chance. Other books just seem so “Belt-y”—they represent exactly why we decided to start the press—because they tell an untold regional history or because they are intellectually rigorous without being pedantic—that we have to publish them to stay true to who we are.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, be sure to get a copy of So You Want to Publish a Book? by Anne Trubek.

July 7, 2020

6 Tips to Create a Memorable Virtual Book Launch

Today’s guest post is by author, editor and Olympian Carol Newman Cronin (@cansail).

Like so many authors publishing books in the time of COVID-19, I’d already scheduled an in-person book launch party when everything social suddenly moved online. I’d never hosted a virtual meeting for more than a few people, and I was instantly overwhelmed by the details of gathering 100-plus readers together: what host would be best? Would the meeting be secure? And most importantly, how could I keep so many distracted people engaged for an entire hour, just by talking about my latest novel?

I now believe that a creative online launch can be the most memorable way to celebrate and share the excitement of bringing a book into the world. Long after they clicked “end meeting,” a surprisingly large number of guests reached out to say they’d enjoyed being part of it. “What was your favorite aspect?” I asked each one—and no two answers were the same; there was enough variety for everyone. I even heard from a stranger who joined, not knowing what to expect, and was inspired to buy the book.

To help others create their own memorable book launch, here are six tips based on my own recent experience.

1. Take your audience on a rideThe title of my book is Ferry to Cooperation Island, so a virtual “ferry ride” became our organizational theme. Two friends signed on as co-hosts (and, at the last minute, I also asked my husband Paul to oversee the chat). My friend Liz is a licensed captain, so she opened the meeting with a welcoming “safety briefing” that mimicked what would be said before pushing away from an actual dock. It was an entertaining way to remind guests to turn off video and audio, and to suggest screen settings that would show both shared visuals and the speaker. Liz also reminded folks that it was okay to leave early—though she added that we’d still be at sea, so it might be “quite wet.” Then I toasted the book’s official launch with a glass of Cooperation Punch (I’d chatted up possible recipes on my blog), and we set off together on our adventure.

2. Talk with, not atOnce we were safely underway, my other co-host Kim introduced me and asked me 10 prepared questions about the book’s inspiration, setting, and characters. Despite all our rehearsal time, it came across as a friendly, casual chat rather than a talking-head lecture—just as I’d hoped. And I was able to convey my excitement about the book to a wide audience that included both friends and unknown readers, without ever wondering if I was boring anyone.

3. Stick to the itinerary, but vary the sceneryEvery good “ride” departs from and arrives back at a pre-planned point, but the unexpected sights along the way are what people will remember. The overarching goal for this party was to share my three inspirations for writing the book (Cooperation, Coastline, and a ferry Captain), so while Kim and I were chatting, Captain Liz screen shared photos and graphics I’d collected as part of my research. The only time I insisted on being on-screen myself was for a two-minute reading of the main characters’ first meeting.

4. Add humor and variety, but don’t overcomplicate itJust before our final rehearsal, I decided to include a photo of the five-year-old me—and I’m sure it sparked some drink-spitting laughter. Many of those after-comments specifically mentioned that particular picture. (“Those red sneakers were so darned cute!”) We also paused halfway through the prepared questions for two Zoom polls; we’d originally planned on four, but realized during the final run-through that was two too many. The polls gave viewers a chance to interact with us without disrupting the planned-out portion of the evening. And the answers provided useful data about how many of my previous books they had read, and whether they already owned a copy of this one.

5. Make everyone feel heardOnce she was finished with the visuals, Captain Liz moderated questions that came in via chat. (Husband Paul definitely helped by pasting the early ones into a private chat, so we didn’t have to wait for her to scroll back through the feed.) Liz also called on people who virtually raised their hands, and they were able to ask a “live” question. That system allowed us to maintain some control of the unplanned portion of the evening, while giving everyone who wanted it the chance to feel heard. It also meant I was free to focus on answering well, because others were handling the logistics.

6. End on time, and close wellAt the one-hour mark, Captain Liz announced that we’d made it safely back to the dock and asked everyone to watch their step when disembarking. Then I raised my glass again and thanked everyone for coming. This bookended the introduction in a very satisfying way, and all good stories need a satisfying ending!

When I first started to plan this virtual book launch, it was easy to get completely overwhelmed by the mechanical details. What I now realize is that, online or in person, the basics of public speaking are still what matter most. Prepare a story that will capture your audience and make them feel included, mix in plenty of variety and sensory detail, and frame it well so everyone knows where you’re headed and how long it will take to get there. That’s what turned this virtual launch into such a memorable occasion, and that’s what will work for you too. Who knows, you might even end up agreeing with my conclusion: that online launches are the most satisfying way to share the excitement of publishing our books.

July 1, 2020

Books to Film: The Option Versus The Shopping Agreement

Photo credit: Carbon Arc on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-SA

Photo credit: Carbon Arc on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-SAToday’s guest post is by intellectual property lawyer and author Matt Knight (@MattKnightBooks).

Most writers dream about their book becoming a movie. It’s exciting to think about seeing our creative endeavors on the big screen or television. Plus, who doesn’t like receiving more money?

But adapting a book into a movie is a complicated process. Film and TV producers must corral numerous financial, creative, and business components (one of which are your dramatic rights) in order to develop and produce a finished product for the screen. In fact, the process can be so complicated and protracted that a movie industry friend of mine once said, “These things rarely pan out.”

Should that stop us from dreaming? Heck no! So, for you big dreamers in the crowd, there are two agreements used in motion picture or TV deals that a writer should understand—The Option and The Shopping Agreement.

Side note: If you need a snapshot of the complete start to finish process of book adaptations, see Jane’s article How a Book Becomes a Movie where she breaks down the process into four parts: The Pitch, The Option, Development Hell, and Production.

The Option AgreementOne of the first steps a producer makes when developing a project for the screen is to lock down the story rights. The usual legal vehicle for this is an option contract. The producer options the exclusive rights for a specified time to develop your creative work. During that option period and before the producer commits to purchasing the work, the producer will determine if there is any interest in adapting the work into a film. The option puts money in the writer’s pocket in exchange for putting the book rights on hold during a negotiated time period.

Here are the basic components of a standard option agreement.

1. TermTypically, an option term is 18 months but it can be as little as 6-12 months. Often the option can be renewed once or twice. These renewable periods are shorter than the original option term, and no more than 12 months.

2. PriceThe writer gets paid for each option and renewal. Often the option fees are more than the author received for the book advance and sometimes more than the royalties paid. The option price depends on the material being optioned and the writer. Author notoriety, the popularity of the work, a producer’s desire for the project—these can drive up the price.

While everything is negotiable, an option can range from $500–$500,000. A good gauge is 10% of the purchase price if the story rights are later bought. (More on that below under #5.)

The fees for renewals tend to be higher than the first option. The reason is demand. If there is interest in the project, the renewal option is exercised. Plus, renewals require a writer to put the story on hold for another negotiated term.

3. Dramatic Rights OptionedThe contract language should define with specificity the rights being optioned.

Producers will want as many rights as possible tied into the option, i.e. not just the right to the make the film but also the right to make sequels, TV movies, series, and if they can get it, merchandising and advertising rights too.

For the writer, it would be financially beneficial to option only motion picture and TV rights, and retain other rights like print, electronic, audio, sequel, merchandising, and dramatic stage rights. Any rights retained by the writer can be negotiated for royalties at a later date depending on the project. Some producers might require that you not exercise those retained rights for a specified time period (most likely until after the movie release date). This is called a “hold back.”

Negotiate the option renewals to be contingent on the producer hitting certain markers tied to forward movement in the production of the project. For example, the option may only be renewed if financing has been secured and/or the necessary people are attached to the project (director, actors, and screenwriters).

4. Termination and ReversionThe option should be clear about termination and reversion of rights when the producer decides not to purchase the rights or renew the option within the specified time periods. In addition, it would be beneficial to the writer if the contract language requires an automatic reversion of rights to the author if the adaptation is not produced within a specified number of years.

At the end of the option period and the renewals, the producer must either drop the project or purchase the story rights. If exercised, the rights in the creative work will then be transferred via a purchase agreement.

5. Purchase Price/Purchase AgreementUsually, the purchase agreement will be negotiated in tandem with the option agreement. Budgets are producers’ worst nightmare. If producers believe a project has potential, they need to be certain how much the project will cost, which includes the cost of the option and purchasing the story rights. The last thing producers want when making a film is to have large, unforeseen costs that ramp up expenses and blow out their budgets.

The purchase price will vary considerably depending on the project. Usually, it will be based on a percentage of the film’s budget with a cap. A good gauge is 2–4% of the production budget. If the budget grows, the producers have the insurance policy of the cap. So, if the budget is $5 million, then the purchase price might be $150,000 (or 3% of the budget) with a cap of $275,000 should the budget grow.

The fee for films will be larger than television, which ranges between $25,000–$50,000. If the project becomes a series, payment is usually per episode (lucky you). The option fee is usually counts toward the purchase price. The renewal fees, however, usually are not.

Some producers will offer a writer a share in the film’s “net profits” in lieu of a set purchase price. A percentage of profits sounds enticing, but net profits in the movie industry will always be less than zero. A better option, if you can get it, would be a percentage of “gross profits,” between 2–5%. Everything is project-specific and negotiable, so you might find that a percentage of gross profits are twined with an upfront purchase price.

Authors usually are required to give up creative control once the work has been purchased. Hollywood sticks with their own screenplay writers (although it is not unheard of for an author to write the screenplay … dream big). Rarely does an author get final approval over the creative content in a film. Such creative control is left to the big fish authors (again, dream big). Some contracts allow authors to consult with the adaptation process, but this is not typical either.

The Shopping AgreementWhile the usual vehicle for obtaining control of story rights is the option agreement, a trend with producers is to use a new legal vehicle for putting a writer’s creative rights on hold. Enter stage right—the shopping agreement.

No, it’s not a free trip down Rodeo Drive with an arm full of bags from Dolce and Gabbana. It’s more like a free ride for the producer.

Under a shopping agreement, the writer grants the producer the exclusive right for a limited period of time to use his best or good faith efforts to obtain a proposal or interest in the project from a studio, network, distributor, financier, or some potential buyer. If the producer is able to show interest during the shopping agreement period, the writer agrees to negotiate a more permanent deal with the buyer for the dramatic rights in the creative work. Whether that more permanent deal is an option agreement or purchase agreement is up to the parties, including the buyer.

Under the shopping agreement, the writer agrees that, should the writer negotiate a deal with a buyer for the dramatic rights, the writer will attach the producer to the project during those negotiations. The producer will usually negotiate separately with the buyer too. Typically, the shopping agreement will also contain language to prevent the writer from circumventing the producer and creating a deal directly with the buyer once interest has been shown in a project.

Why the switch from option to shopping? Cash.

There’s no money exchanged in a shopping agreement like there is in an option agreement. For the producer, this is a big benefit. He doesn’t have to spend development funds to put a hold on the dramatic rights. He gets, for free, a short window of time (generally 6–9 months) to secure a potential deal.

Pros and Cons: The Shopping Agreement vs. The Option AgreementWhile at first glance the shopping agreement doesn’t sound so grand for the writer, there are some benefits.

Shopping agreements do not pre-negotiate the purchase price. If there is interest in the project, the writer can command a higher purchase price, one that most certainly will be better than the pre-negotiated option/purchase price.

The term in a shopping agreement is for a short period of time. If the producer can’t deliver, the writer can move on to another potential deal. But if the producer has pitched widely with the project, the likelihood of other opportunities may be greatly reduced.

Shopping agreements give the writer more say in who the producer pitches the project to and if the buyer is acceptable. Option agreements tend to give producers free rein when it comes to who picks up the project.

Shopping agreements give writers more control over their rights. In the option agreement, the producer gets an exclusive option to purchase the dramatic rights to the book (i.e. film and motion picture rights) during the option term. This means the producer has exclusive control over these rights and cannot be circumvented during the option period (by anyone). A shopping agreement, however, allows the writer to keep full control and ownership of the dramatic rights. The producer can only shop the project to selected buyers.

Sadly, most book–movie projects never see the light of day. So, if a writer has signed a shopping agreement, the writer has zero certainties that a project will be made and has zero leverage to shop the book to other producers during the shopping agreement period. The writer’s hands are tied. An option agreement at least puts cash in the writer’s pocket.

Every deal is different, but if the producer has a strong track record of getting projects made, then a writer may want to give the producer a little bit of free shopping time.

In my opinion, an option is often better for the writer because there’s money upfront. Plus, with an option, the producer has skin in the game and more reason to make the project. It does mean that a writer will have to be comfortable with the longer option period where the dramatic rights are under the producer’s control. But hey, you have to give a little to get a little. Hopefully, the payoff will be seeing your book on the silver screen.

June 30, 2020

Marathons, Sprints, and Pounces: 3-Tiered Approach to Book Launches

Today’s guest post is by author Barbara Linn Probst.

Nearly three months after the launch of my debut novel, I’m reflecting on what I’ve learned. Clearly, some lessons will take more than a few months to work their way through all those layers of hope, frustration, weirdness, exhaustion, and joy. But other lessons have coalesced, and I’d like to share one of them with you today.

Before I embarked on this process, I saw it as one big amorphous here’s my book, everyone! But it’s not. Promotion happens at different times and on different scales. Or, I should say, authors do things at different times and on different scales, apart from what publishers or publicists do. I’m calling these launch-related activities marathons, sprints, and pounces—long-lead strategies, mid-range tasks, and sudden opportunities.

Navigating these three distinct realms requires availability, adaptability, and a flexible responsiveness—that is, the ability to manage the spectrum from delayed gratification of long-term plans to that impulsive oh, what the heck? when an opening arises that you never expected. You need all three. At least I did.

MarathonsMarathons are the strategies, relationships, and connections that are built over time in the hope of an eventual payoff. They require a prolonged investment of energy, as well as patience and tolerance for delayed gratification—or no gratification at all, because the context can change in ways that might have nothing to do with you, your book, or anything you did.

We all saw that this spring. In my own case, I had spent months building a relationship with the marketing director at Ghost Ranch, New Mexico, where Georgia O’Keeffe lived and worked, since Queen of the Owls is framed about O’Keeffe’s life and art. I’d hoped that the gift shop might carry the book or allow me to offer promotional material in the Welcome Center. Neither idea worked out, for reasons unrelated to my book, and I resigned myself to “a great idea that didn’t happen”—but then, to my astonishment, the marketing director suggested that I do a special event on-site that would be promoted through all their outreach channels and open to the entire city of Santa Fe. I had a radio interview lined up, a podcast, a bookstore. As you can imagine, it was a dream come true. And then—#pandemic. At best, this endeavor will come to fruition six or seven months later than expected, or in a different way; at worst, never. Either way, I’m certain that I was right to pursue it, because not pursuing it would have been, for me, a huge what-if regret.

Another long-term strategy I undertook was to build a presence on the Georgia O’Keeffe Facebook group, which has over 3,000 members. I spent months sharing images, links, and information—creating a friendly and generous presence—before I even mentioned Queen of the Owls. This seemed to be the perfect market! To my surprise, it wasn’t. I did sell a dozen or so books, but the payoff was hardly in proportion to the amount of time I invested.

As with Ghost Ranch, I would have regretted not doing it, because you never know where the finish line actually is. It could be waiting in the future—one key person who thinks of me when an O’Keeffe-related opportunity arises (i.e., a potential “pounce” that was only possible because of the prior “marathon” I’d run; more about that below).

Marathons also include platform-building and friend-making through Instagram, Twitter, email newsletters, cross-marketing with other authors, and participation in groups of writers and readers. They’re long-term strategies that may have a delayed result or a result that can never be measured, because you can’t tease out the specific effect of any single strategy. Often, it’s the cumulative effect, the repeated exposure across a variety of formats.

Are marathons worthwhile, given their inherent uncertainty? To me, they are. After all, how many strategies truly have a guaranteed, time-stamped payoff? Launching a book is a risk. So are relationships, new jobs, and just about everything that makes life interesting!

SprintsSprints are launch-specific, short-term activities, although they can certainly be planned in advance. They’re the promotional ideas that we keep on our laptops, the “to do” list we’ve culled.

Sprints include cover reveals, contests and giveaways, interviews and chats, podcasts, blog tours, and events at bookstores and book fairs (yes, we will have those again, one day). There’s a lead-up, but it’s shorter than for a marathon, and the sprint itself covers a shorter period of time. To a degree, the payoff can be measured—for example, by the number of books sold at an event.

The specific things you do in the weeks before and after your launch will depend on your personal style, budget, locale, genre, audience, and overall goals. No one can do everything. Trying to manage ten or twelve sprints at once is unrealistic, so you might want to prioritize and/or space them out so you’re engaged in only one or two at a time. Some sprints are free, and some cost money. It helps to ask others who’ve gone before, although everyone’s experience is likely to be different.

If something is in the marathon category, it might also include a sprint or two. For example, if you’ve been devoting a lot of time to building a network on Instagram, at launch time you can also do something specific there—but only if you’ve done the marathon work first. I speak from experience! A mistake I made was trying to promote a sprint on Instagram when I hadn’t put in the long-term effort to build a presence there. I had an idea for an Instagram Countdown to Publication of Queen of the Owls that would involve my posting a new O’Keeffe painting each day, with a quote from the page in the book where the painting was mentioned. It seemed like a great idea (to me)—but no one cared. I hadn’t done the groundwork of creating engagement and community on that platform, so my countdown didn’t generate any interest.

PouncesPounces are the unforeseen opportunities that arise and require an immediate and spontaneous yes—or no. They were my favorite part of the launch process, actually. “Would you be interested in …?”

I can’t recall ever saying no. No matter how small the opportunity, assuming that the only cost was my time, I figured why not? A Zoom interview on a site that typically had two dozen viewers? Sure! That meant two dozen people who might hear about my book for the first time. An interview for someone’s blog, a chance to do an “author hour” on a Facebook group, a few paragraphs for inclusion in an article? All yes. My mantra was: You never know.

Because of the pandemic, the last-minute opportunities that I encountered were mostly virtual, but I’m sure the in-person ones will return—e.g., a sudden opening for a spot at a book fair table or a place on a panel.

Putting it all togetherThere are a few key principles that apply at all three levels:

Manage expectations. Formulate—and adapt—your goals. Let go if something doesn’t work out and move on. Book promotion is a journey into the unknown; effort invested and results obtained are rarely a perfect match. Learn to be nimble and relaxed.

Diversify. Use a variety of elements, from wild and creative to tried-and-true. Keep many irons in the fire, so you aren’t investing or expecting too much from any one endeavor. Disappointment is inevitable, but if you’re ten or twenty percent disappointed when that book club opportunity falls through, it’s a lot easier to rebound than if you’re ninety-five percent disappointed.

Focus on the present. While it’s important to maintain a “big picture” perspective, even the longest marathon is really just the accumulation of small steps—small acts, small moments of now. Each email, each Facebook comment, each thank you.

A book launch requires stamina, resilience, flexibility, and generosity. Most of all, it requires a deep and abiding belief that you have something to offer. The only way I could handle the buy my book message—especially now, during a time like none we’ve ever experienced—was to hold fast to my conviction that stories help. Throughout history, they’ve been sources of healing and renewal and growth, just as interacting with readers is a chance for connection. There’s no need to apologize for that.

This post isn’t intended to be yet another essay about “writing in a time of COVID-19.” Some of my examples relate to the pandemic, because it’s the context in which my own novel launched. Yet the need for long-term, time-sensitive, and spontaneous elements is not COVID-specific. I’d like to think it’s the hallmark of a savvy author.

What about you? Do you gravitate toward one of these approaches more than the others Does one of them sound as if it might be a challenge for you? How does your own experience map onto this way of looking at a book launch? Let us know in the comments.

June 24, 2020

You Win This Round Comma

Photo credit: Mattiii photo on Visualhunt / CC BY-NC-SA

Photo credit: Mattiii photo on Visualhunt / CC BY-NC-SAToday’s guest post is by author, editor and writing coach Mathina Calliope (@MathinaCalliope).

Hardly anyone would argue that commas don’t matter, but plenty of people—including plenty of writers—give them too little thought. At some point in their lives they might have tried to understand all the rules (commas to restrict information? Oxford commas? vocative commas?). They wanted to hug the English teacher who said they could simply use them “wherever you would pause if speaking.”

They went on their way, relieved to think commas were a style choice, there weren’t necessarily hard-and-fast rules, they could let an editor worry about that. Or a reader, who would be saddled with the extra mental work required to discern the author’s intended meaning.

Actually, though, you cannot just put commas where you would pause when speaking. Why? Because the presence or absence of a comma conveys meaning.

Since you’re reading this blog, you’re probably familiar with some egregious examples of comma malpractice, for example, “Let’s eat Grandma.” You know you can save a life with the vocative comma: “Let’s eat, Grandma.”

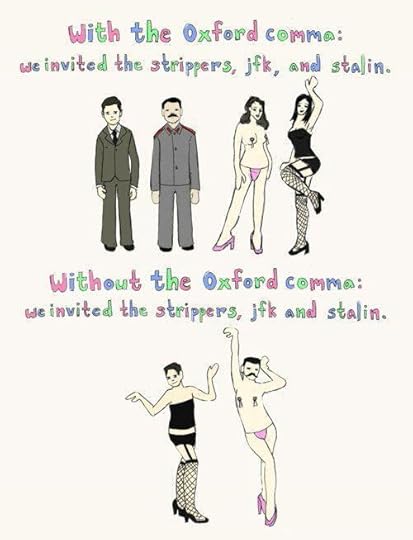

Other chuckle-worthy comma memes populate the internet, such as the picture of Stalin and JFK outfitted for pole dancing versus the one of Stalin, JFK, and two strippers (illustrating the value of the Oxford comma).

My favorite, and the most nerdy, meme is a Tumblr post with a picture of a knife blade in a block of cheese, handle broken off. The caption reads, “You win this round cheese.” The first reply: “actually that is a rectangle cheese.”

Here’s the next reply: “[oxford comma laughing in the distance].”

Then the mic drop: “[vocative comma wondering what oxford comma thinks it’s doing here].”