Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 309

April 8, 2016

A Revolution in Many Tongues

In February of 2015, Ankara Press, a romance imprint of the Nigerian publisher, Cassava Republic Press, debuted a Valentine’s Day Anthology that featured romance stories originally written in English and then translated into the author’s mother tongue. The anthology was published online and was a free download. At the same time, both the original and the translations were read aloud, by the writers themselves or others, and the recordings made available online. As the editors explained in their introduction, the Valentine’s Day Anthology was “a much truer representation of romance in Africa as we can hear and see what romancing in different languages might sound like and mean.”

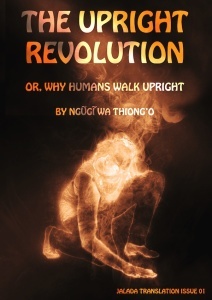

This month, Jalada Africa, an online journal out of Nairobi, has upped the game: publishing a short story originally written in an African language, with translations in 30 African languages. The story, Ituĩka Rĩa Mũrũngarũ: Kana Kĩrĩa Gĩtũmaga Andũ Mathiĩ Marũngiĩ, is by Ngugi wa Thiong’o and was originally published in March 2016 in Kikuyu, a Kenyan language. It has now been translated as The Upright Revolution: Or Why Humans Walk Upright. This makes it the most translated African language story.

Jalada’s intervention has been a long time coming. Back in 1962, a group of young African writers met at the Makerere Writers’ Conference, under the now unfortunate banner, “African Writers of English Expression,” promising to decolonize African literature. The young and optimistic Ngugi also captured this excitement when he enthusiastically concluded in his post-conference write up titled, “A Kenyan at the Conference”: “With the death of colonialism, a new society is being born. And with it a new literature.”

Translation between African languages has yet to be practiced and theorized into critical and popular acceptance. Jalada is undertaking both theory and practice, and saying that African languages can talk with each other. Its call and answer sends out a challenge to writers, scholars and publishers who see African languages in the service of the more useful English. Or conversely, those who understand translation as most desirable when coming from superior European languages into anemic African languages desperately in need of anglo-aesthetics transfusion.

Jalada’s translation initiative is also part of a larger language awakening. Capturing the shift from an English-only consensus to a multiple-languages debate, the 2015 Kwani literary festival titled, “Beyond the Map of English: Writers in conversation on Language” centered and celebrated the language debate. At that festival prizes for the inaugural Mabati-Cornell Kiswahili Prize for African Literature were awarded. Scholar and writer Boubacar Boris Diop has started, Ceytu, an imprint in Senegal dedicated to the translation of seminal works by Frantz Fanon, Aime Cesaire and others into Wolof. In 2013, Chike Jeffers edited an anthology of philosophical texts originally written in seven African languages and then translated into English. And Wangui Wa Goro who translated Ngugi’s Matigari from Gikuyu into English in 1982 has done a lot of work to make African literary translation viable and visible.

When setting up the $15,000 Mabati-Cornell Kiswahili Prize for African Literature, Dr. Lizzy Attree and I were immediately confronted by the absence of structures that are simply taken for granted when it comes to English language writing; there is a dearth of scholarship, and little recognition in the way of prizes. For Kiswahili, with more than 400 millions speakers, literary prizes number no more than five. I do not know of a single journal devoted to literary criticism in an African language, or any writer residencies that encourage writing in African languages. The point is, given a population that will soon reach one billion people spread out in 55 countries, even one hundred African language-centered journals and literary prizes would be pitifully inadequate. African literature needs a lot more of everything.

To be sure, advocates for writing in and translating among African languages have their dissenters. For example, Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani, the author of the novel I Do Not Come to You by Chance, argued in a 2010 New York Times op-ed titled, “In Africa, the Laureate’s Curse”, that because Ngugi wrote in an African language he should not be awarded the Nobel Prize for literature. She argued: “I shudder to imagine how many African writers would be inspired by the prize to copy him. Instead of acclaimed Nigerian writers, we would have acclaimed Igbo, Yoruba and Hausa writers. We suffer enough from tribal differences already. This is not the kind of variety we need.”

To make the argument that languages creates “tribal differences” sounds so asinine in light of Jalada’s translation issue. As Jalada Africa shows: A thousand African languages, a thousand opportunities to make literary history.

Jalada has youth on their side: Like the Makerere generation before, Jalada is composed of young writers who understand their mission to contribute to decolonization: Moses Kilolo, the Managing Editor, Novuyo Tshuma the Deputy Editor, the Treasurer, Ndinda Kioko and other writer administrators are in their 20s and early 30s. Among many others, writer members of the collective include the 2013 Caine Prize Winner Okwiri Odour, the brilliant Mehul Gohil, featured in the anthology Africa 39: New writing from Africa South Sahara, and the gifted poet Clifton Gachugua, whose first collection of poetry, The Madman at Kilifi (University of Nebraska Press 2014) won the Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets.

In translation, there are no indigenous, vernacular, native, local, ethnic and tribal languages producing vernacular, native, local, ethnic and tribal literatures, while English and French produce world and global literature. There are only languages and literatures.

April 6, 2016

Pan African Space Station Lands in New York City

Last November Chimurenga installed the Pan African Space Station at Performa 15 in New York, which was described as a “multi-tiered programming platform that takes the form of a library-of-people” and featured (amongst others) Brooklyn-based African Record Centre/ Yoruba Book Center; artist and educator Nontsikelelo Mutiti; and poet, choreographer, and Afrosonics archivist Harmony Holiday.

As part of the installation, Africa is a Country curated three panels over the course of the weekend, covering reflections on music and migration, identity and cultural expression in photography; as well as the exchange between African and Caribbean music. All the sessions are available on our Soundcloud.

We (via Alice Obar) also made a short video on the PASS installation, featuring interviews with Chimurenga associate editor Stacy Hardy, artist Nontsikilelo Mutiti, and African Record Center co-owner Roger Francis. Not to mention highlights from the panel discussion, as well as some music by Lamin Fofana, Innov Gnawa, and Tanyaradzwa Tawengwa. Check it out below:

April 4, 2016

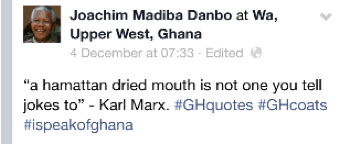

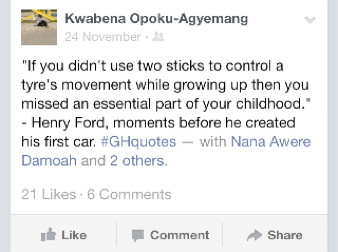

Ghanaian Facebook Proverbs

Surely the American actress Marilyn Monroe never quoted the Akan proverb: “Never laugh at the sloppiness of your mother-in-law’s breast; your wife’s may turn out to be just like that when she grows older”; neither did a young Angela Merkel, long before becoming German Chancellor, ever retort that “Fermented sobolo never got anyone drunk” at the 1972 Oktoberfest! But you would be forgiven for even wondering if either attribution were true had you chanced upon Ghanaian social media spaces just over two years ago.

Ghanaian’s on Facebook and other social media platforms post innovative works, misattributing quotes to well-known figures (who are mainly from the geopolitical West) to create humorous collaborations with their Ghanaian readers, questioning the authority of said geopolitical western figures, and challenging their audience to think about what is assumed to be true. This has evolved from a particular context: a significant portion of the population has access to the Internet, and shares a cultural history and present that demand a fine-tuned sense of irony – an irony that mocks popular “western” figures and the “superior fonts of wisdom” attributed to the West as a whole.

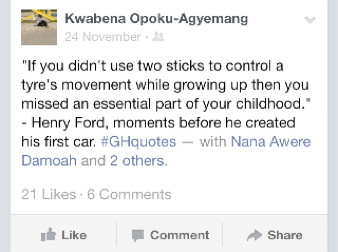

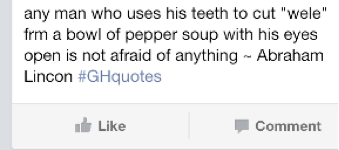

It all started in November 2013 when the Ghanaian writer, Nana Awere Damoah posted on Facebook: “Never introduce your child to the delights of the tilapia head until he or she is old enough to buy for himself or herself – Abraham Lincoln”. A Ghanaian journalist named Abubakar Ibrahim followed suit, also on Facebook: “having an okro mouth does not mean you will be given banku to go with it – Albert Einstein.”

Both Damoah and Ibrahim posted these quotes for their obvious humour. Their respective Facebook communities, mainly other Ghanaians, responded with comments acknowledging the disjunctions. After all, from a Ghanaian (and probably any other) point of view it is hilarious to imagine a 19th-century American president with no known connection to West Africa extolling the virtues of savoring the head of a tilapia (which is a very Ghanaian thing to do). Equally ridiculous is the notion of Einstein idiomatically connecting an “okro mouth”, which signifies gossip (due to the slimy and slippery nature of okro soup) to banku, a staple food which accompanies okro soup (yum).

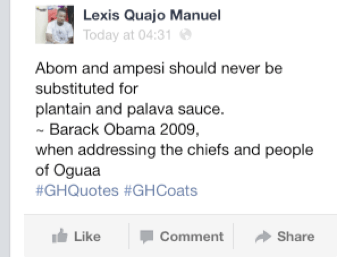

Similar to #WhatWouldMagufuliDo trending across East Africa, these posts spurred a chain reaction that went viral on Ghanaian Facebook and Twitter for several months, as users creatively poked fun at famous figures and criticized issues of national interest. These posts were made up not only of Ghanaian proverbs misattributed to a famous person or fictional quotes misattributed to famous people, but also included common Ghanaian parlance misattributed to famous names and modified quotes from actual authors.

Posts like these were marked by the hashtag #GHCoats, made up of “Ghana” and “Quotes”. (While the “GH” is straightforward, the replacement of “quote” with “coat” is an inside joke for those familiar with Ghanaian phonetics. The play on words also plays with the habits of the bourgeois – who, in Ghana, are associated with formal dressing, including wearing “coats” (quite humorous when you consider the tropical weather inherent to the country – for more satire on this, see the prose of Ayi Kwei Armah in Fragments and the poetry of Kofi Awoonor in “We Have Found a New Land”).

Ultimately, Damoah compiled the innovative Facebook attributions into a free e-book called My Book of GHCoats. My Book of GHCoats can be called conceptual poetry, which is an avant-garde form of literature that comes into being when a poet compiles different pieces of information from various places into a single piece. Thus, we can think about questions relating to authorship, audience and collaboration, all in the context of their relationship with social media.

April 3, 2016

Decolonizing the teaching of economics in South Africa

Recently Ihsaan Bassier, a graduate student in economics at the University of Cape Town (UCT) in South Africa, wrote a thought provoking essay for GroundUp, a local news website, on the need to “decolonize” the teaching of undergraduate economics at that university. Economics in South African universities is currently taught in the manner and methods of the neoclassical school which has been shaped by universities in the West. The neoclassicals emphasise the primacy of markets in resolving questions about production and distribution.

For Bassier, a decolonized curriculum is one that puts the teaching of South Africa’s economic realities (inequality, poverty, unemployment, demographic underrepresentation, racism, etcetera) at the heart of the curriculum. It matters that we decolonize economics, argues Bassier, because most students don’t go onto graduate studies, “where theories are supposedly interrogated.” As a result, “they will enter policy and business [professions] thinking that intervention always harms the poor, that outsourcing is only ever efficient, and that markets are ultimately fair towards employees.”

Bassier’s critique forms part of a broader conversation on decolonizing university curricula that’s currently taking place on campuses across South Africa (and in the United States and parts of Western Europe). That debate has now slowly moved to the disciplines, especially the social sciences and the humanities. See here, here and here.

My own experience at UCT agrees with his general observations. I did all my graduate study there (Honours, Masters and PhD) and taught undergraduate economics in that School from 2012 to 2014. What I’ll do here is add a little to Bassier’s arguments (with examples) and respond to some of the criticisms raised by his essay in South Africa.

Let’s look at the way the “Labour Market” is taught to undergraduates at UCT. The importance of this market cannot be overemphasized given the high levels of unemployment and wage disparities in the country. Naturally, students come to class with the expectation that they will understand what they see around them. Unfortunately, the standard material disappoints.

Start with wages. Students want to know why an executive at a financial company earns R80 million (US$5million) per year and why someone on the janitorial staff might earn only R35,000 (US$2,300); that is about 2,000 times more. The standard story is that wages are determined by “marginal productivity”. In other words, people are paid according to how much they “contribute” to the company. So the executive earns 2,000 times because he contributes 2,000 times more.

This story is only partly true because we know that wage disparities are also a result of executive capture of the compensation process. That is, executives are in many ways determining the sort of pay packages that they receive (see the work of Piketty and friends). A decolonized curriculum would also stress this other channel through which income disparities arise.

Now consider minimum wages. We teach students that minimum wages result in unemployment and the only exception, slipped in as a by the way, is the case of monopsony. That is, minimum wages are only beneficial to workers if the labour market is dominated by a single employer. The logic is simple: a single employer will force down wages so that instituting a minimum wage can actually increase earnings and employment. But the South African labour market is to a large extent dominated by monopsonists. UCT is itself a big player in the market for hiring janitorial staff – that’s precisely what the #EndOutSourcing protests on campuses are about. And so too are Labor brokers. Monopsony, therefore, has to feature prominently when teaching labour markets in the South African context.

But let’s get to the commentary on Bassier’s post. Surprisingly, given what’s at stake, there’s been very little of it. Save for a few references on social media, there was this response of Johan Fourie, a lecturer in economics at Stellenbosch University and avid blogger, that deserves some reaction. One of Fourie’s key accusations, without any basis, was that Bassier wanted to “remove content.” This is of course a distortion of Bassier’s views. Bassier simply wants the curriculum to reflect South African realities. That distinction is important.

Fourie then claims that graduate studies offer a more decolonized curriculum than undergraduate studies. But this is at odds with my own experience as a graduate student at UCT, where the teaching only serves to entrench the neoclassical school. Just flip through the content of the standard graduate textbooks. And even when, as PhD students, we conduct South African-centered research, the research questions are asked through a neoclassical lens. I too would have been a priest of this school had I not sought alternative views.

Finally, Fourie suggests that undergraduates take-up economic history electives as a way of introducing local context to their overall learning. I agree with him on the importance of history, but unlike him, I’d want South African historical context to feature prominently in the compulsory undergraduate economics courses. Students shouldn’t have to take an elective to learn about the role played by the egregious hut tax in the rise of South Africa’s mining industry. Students shouldn’t have to take an elective to learn that the high levels of income and wealth inequality in South Africa today are related to large-scale systematic dispossession and discrimination over the course of history.

Ihsaan Bassier has started a really useful and long overdue conversation about the place of economics teaching in the South African academy. It’s time to start thinking about the answers.

April 2, 2016

It’s good for the future of cinema that Africa exists

It’s only April, but it’s already been a bad year for Hollywood. If you need a reminder: an all-white acting nominee list at The Oscars; a“swag bag” featuring a free trip to Israel; Chris Rock’s tone-deaf stereotypical jokes about Asian Americans; Leonardo DiCaprio wins Best Actor trophy for a role “celebrating the resilience of settler colonialism on land constructed as terra nullius;” and the producers of the new Nina Simone biopic thought it would be good to blacken up lead actress Zoe Saldana. Which reminds of something Senegalese director Djibril Diop Mambety once said: “It’s good for the future of cinema that Africa exists.” Which is why reviving our #MovieNight feature. From now on this will be a fortnightly feature. Here’s our movie night to right all the celluloid wrongs.

(1) One of the most interesting short films to come out of South Africa recently is Jas Boude, a documentary by two University of Cape Town film students that chronicles a day in the life of the 20SK8 collective, a group of skateboarders from the city’s Cape Flats. The film touches on overcoming the continuing violence of apartheid-inherited spacial geographies via some beautiful camerawork and a pumping yet emotive soundtrack by BFake. We thought it was pretty jas.

(2) Nigerian American rapper Tunji Ige just dropped a short documentary called Road to Missed Calls which The Fader has described as “…an incredibly insightful and telling vantage point of an artist who’s at that page turning part of their career, and can go in either direction.” The film starts off with a series of missed call voicemails from the filmmaker and the creative team behind Tunji. While clearly not a great communicator, Tunji is definitely a talented musician, and an artist to watch.

(3) Young eco-conscious filmmakers Sinematella Productions have created a ‘video poem’ shot on location in Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Mozambique, Lesotho and South Africa as an ‘ode to the continent we get to call home.’

(4) Staying with the visual poem theme, London- based fashion photographer Seye Isikalu has created a short film called The Ocean, dealing with “the complexities that sometimes come along with being completely passionate & committed to who or what you love.”

(5) Activist filmmaker Iara Lee, a Brazilian of Korean decent, has made it her life work to seek a more just and peaceful world through the arts. She started a foundation called ‘The Cultures of Resistance Network ‘ and recently made a film on “Africa’s last colony” – the Western Sahara. The film focuses on a group of young Sahrawi activists as they risk torture and disappearance at the hands of the Moroccan authorities, who have been occupying their homeland since the Spanish left four decades ago.

(6) On a sweeter note, South African romantic comedies seem to be really taking off. Happiness is a Four Letter Word is following the success of Tell Me Sweet Something by delivering thick on the rom with a little sprinkle of com. While it presents an imagined Joburg that is more aspirational than realistic, it’s about time black characters get do more than suffer and endure hardship on screen.

(7) In 2012 a blog post by US-based Zambian author Field Ruwe called ‘You Lazy Intellectual African Scum’ caused a social media storm. The story was essentially about a white ex-International Monetary Fund official scolding the writer on a New Year’s eve flight, blaming Zambia’s intelligentsia for its levels of poverty. While it sparked a rigorous debate on the role of intellectuals in African society, it presented a completely skewed version of what Zambians are actually doing to build their country. It also absolved the west of any wrong doing. The film version of the post, by Kenyan student director Kevin Njue has just been released on Buni.TV. You can stream it here

March 31, 2016

A non verb

Ask me who are my top five South African MC’s and Proverb sits comfortably unchallenged at the top. Proverb is one of the few rappers, metaphorically speaking, who can spill blood without drawing a weapon (i.e.without being vulgar). And he confesses that this is because he’d like his kids to be able to listen to his music from a young age.,

Proverb’s policy on vulgarity is one the things that sets him apart from his peers, who like him have daughters and sons yet have no qualms about the vulgar content of their material. “Not for my kids” or “My kids will have to wait”, they argue. It is a challenge, one that is rarely taken on by rappers. Equally challenging, though, is for rappers to produce content that is relevant and current. And Proverbs latest album, “The Read Tape”, has me questioning if he has risen to it.

Listening to “The Read Tape” it sounds like Pro is literally out of words. I want to compare him to Kanye West who hasn’t produced or delivered anything we can call music, since “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy.” But we still listen to him because behind the trash he currently produces is a catalogue that demands attention, or at least acknowledgement.

Proverb, like Kanye, has a catalogue behind him that very few can match, and unless you recall that catalogue, it’s easy to relegate “The Read Tape” to the “just another hip-hop album” bin. Pro has done enough great hip-hop albums – inspirational work, such as “Fourth Wright” – so he doesn’t need to produce “just another” one.

At a time when South Africa is on fire politically, there is sadly zero social commentary on the album. And the word play we know and love Proverb for, is absent or rather childish. There are more freestyles than carefully crafted verses and not a mist of motivation in his rhymes. He sounds like an insecure and tired vet.

Pro solidified his place on the throne South African hip-hop with his back catalogue. “The Read Tape” gives anyone who wants to take a shot, a chance to claim that seat.

March 29, 2016

The art of Wura-Natasha Ogunji: Beauty, stillness, and connection in Lagos

Splitting her time between Austin, Texas and Lagos, Nigeria, Wura-Natasha Ogunji is part of a movement of first-generation visual artists of the African diaspora who have chosen to relocate their art practice to the home country of their parents. Ogunji’s work consists of mixed media work on paper, performance art and video, and explores homeland, diasporic identity, the role of women in Nigerian society and figures from Yoruba folklore.

In this series, the use of hand sewing to create visual commentary about Nigerian modern society brings to mind the vital role that women have historically played as producers of cultural critique, both inside and outside of the home. Commonly associated with[image error]women’s work and the decorative arts, the inclusion of threadwork in Ogunji’s pieces can easily be seen as resistance to the type of cultural production that has been most valued by the art world and what has been dismissed as craft.

Fascinated by the ways in which people negotiate the city using little to no words and how simple gestures incite actions, Ogunji attempts to capture snippets of all that goes unsaid. Creating complex, dreamlike scenes on architectural tracing paper, which appears almost cloth-like against the thread, graphite and ink, Ogunji’s drawings are weightless in material and ethereal in theme. The forms in her illustrations seem to have a life of their own,conspicuously attached to diverse sources of energy: Disc jockeys don vibrant Ankara prints, beams of neon blues and oranges radiate from figures, the Ife heads give (or take) energy from plants at the bottom of the sea, and humming generators give life to blossoming flowers. In four panels Sound Man and the Sea (2015) depicts a man who wears headphones manipulating what could be a sound system or turntable just below the surface of thrashing ocean waves, rendered with gestural dark blue and electric green brush strokes.

[image error]Wura-Natasha Ogunji “Sound Man and The Sea” (2015) Thread, ink, graphite on paper 4 panels (60 x 24 inches each)

Opposite the figure is an Ife head partially submerged in the water, perhaps keeping a watchful eye. In Generators Flowers Ife (2014), two neon green generators power the growth of four orchids. Attached to electrical cords that double as stems, the flowers hover in front of a seemingly live Ife head that has a flower tucked behind her ear. The drawing is likely a comment on the ubiquitous presence of generators in Nigeria, which suffers from frequent electrical outages, but also acknowledges the incredible influence generators have on the lives of modern Nigerians and the role they play in sustaining modern culture.

In these works, as in other drawings from the series, the traditional is never far from the modern, and machines are inextricably linked to human, plant and spiritual life. These relationships are hardly antagonistic but sophisticated and graceful in their chaos. Ogunji reveals oft-overlooked aspects of Africa’s most populous city and asks viewers to see Lagos as an afro-futuristic dreamscape, where beauty survives in the contradictions and the possibilities are endless.

[image error]Wura-Natasha Ogunji “Generators Flowers Ife” (2014) Thread, ink, graphite on paper 23 x 24 inches

Mixed feelings: reflections on the Ivy League

Princeton Campus, image via Flickr.

Princeton Campus, image via Flickr.

In his book, Whistling Vivaldi, Claude M. Steele explains how stereotypes can become a self-fulfilling prophecy, subliminally affecting the behaviors and performance of those who are subjected to them. Though we all recognize that profiling exists, we often forget how much it influences our interactions and experiences, and are only reminded of it when drawn out of our element and thrown into an environment that refuses to recognize us. In the United States – a country that prides itself on social mobility and acceptance – anyone who has straddled color and class lines, is reminded that they do not belong. An illusion of diversity and inclusion masks and protects institutionalized inequality and privilege. Real diversity and inclusion cannot exist without dismantling the latter.

A few weeks ago, I was invited to a dinner at the house of a Princeton alumna, who had graduated ten years before I began my studies there. It was an occasion to discuss equity and diversity issues on campus, given the recent waves of protest at Ivy League institutions, including our alma mater. I typically avoid such events, but, curious, I decided to go, most of all because I did not know why someone like me, who never donated money to the university, never showed interested in alumni affairs and barely maintained a connection to peers or faculty, was invited.

For many who went to an Ivy League school, this type of social gathering is anything but unusual. As I walked in, a gentleman checked my coat and handed me a glass of wine. I sighed a breath of relief for having gone home before coming and changing into a skirt, cardigan and Italian black flats, rather than wearing the black jeans and worn-out boots I had donned to work that morning. I entered awkwardly, surrounded by people who were at ease mingling and making small talk about their philanthropic organizations while nibbling on hors d’oeurves.

One of the first people who spoke to me was an older gentleman from the class of 1971. Interested in what the letters and numbers on his name tag (P00, P002 P004) meant, I asked him.

“I’m a proud parent of three Princeton alums,” he said, “Class of 2000, 2002, 2004.”

“Oh,” I replied, somewhat startled. Then I realized nearly everyone who was within the age of having adult children had one or more child who attended or graduated from Princeton. This was the status quo. Consider the fact that at most Ivy League schools 10%-15% of those who end up enrolling are the children of former graduates. “Legacies” – children of alumni of a generation or so back – number twice as many.

During the dinner there was much talk of the status of equity and diversity on campus, and of what the university was doing to address the challenges that less privileged and minority students faced. This was all valiant, but the way it was done was yet another reminder that to be part of this conversation, to be invited to this dinner, indeed to be a Princetonian, one has to conform to a role. These exclusive parties – despite their underlying philanthropic objective – are evidence of it. To partake in this camaraderie, one is constantly thinking about how to speak “intelligently,” remembering which fork is for the salad and which is for the entree, and the need to laugh at the jokes, but not too loudly. In short, how to fit into a social class that has never been open to people like you. According to Steele (and many others) this is where the dissonance occurs. In the world of the Ivy League class and the world that the majority of us come from, there is very little convergence.

When I left later that evening, I continued to feel unsettled. There was a time, I recalled, when I was an undergraduate, when one of my friends asked me if I wanted to make some extra money. Though I came from a middle-class, immigrant family my parents supported me in colleague by giving me cash for things like food and leisure. Yet, wanting some financial independence, I took the opportunity. A week later, I found myself at a mansion in Princeton Township, dressed in white. This was where I first learned how to open a bottle of champagne and pour a glass of wine neatly and properly. Now, some 7-8 years later, I was a guest at one of these dinner parties being served wine and dinner by a middle-aged black man. Maybe it was just irony but there was something convoluted and sad about this situation. I did not want to be part of this. I do not want my kids to be part of it either

I spent six years of my adult life at Princeton and in most of the time since then I’ve struggled to reconcile what that meant with the person I am. My feelings about the school are mixed. The education I received has undoubtedly opened many doors for me. At the same time it has made me extremely conscious of the fundamental elitism ingrained in an Ivy League education and transmitted from generation to generation. At least now we are beginning to have conversations about this ugly truth. I question, however, if it is truly possible to change and make more inclusive an institution that, at its core, is meant to buttress the modern American bourgeoisie and all its privilege. I hope to be proven wrong.

March 27, 2016

The deep economic and political crises in Angola

Angolan President Jose Eduardo Dos Santos at Vnukovo II government airport in Moscow, 30 October 2006. Image via Getty Images.

Angolan President Jose Eduardo Dos Santos at Vnukovo II government airport in Moscow, 30 October 2006. Image via Getty Images.There’s a lot going on in Angola. Western media have extensively covered the trial and detention of the so-called book club (really a civic activists study group on protest) and the imprisonment of Cabinda activist Marcos Mavungo to the exclusion of other questions. The 15+2 activists, how the book club is known, and Mavungo highlighted economic mismanagement and corruption in their critiques of the government. Meanwhile, a related crisis, the government’s navigation of the ongoing economic crisis (the price of oil plummeted with no prospect of resurgence any time soon), has received less attention outside of the business press.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights enshrines economic rights – like the right to an adequate standard of living and to work. Yet most human rights organizations (Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, etcetera) opt for the more idealistic political rights – freedom of political expression, freedom of association and assembly. It may be why we don´t hear much in the international press about the economic crisis that squeezes daily life for ordinary Angolans more than politics.

Three other events since the beginning of 2016, equally as important as political human rights issues, are also shaping the political scene and refracting the economic crisis.

The first is the passing, on February 27th, of Lúcio Lara, an historic leader of the ruling MPLA during the armed struggle and first decade of independence. Lara was considered the successor to first president, Agostino Neto, but stepped aside so current president, Jose Eduardo dos Santos, could become leader in 1979 . Lara, who clashed with profligate MPLA leaders, effectively retired from politics when the MPLA made the transition from Marxism to neoliberalism in the late 1980s.

Eulogies proliferated. Many read these as critiques of the current regime.

The political scientist and long time Angola observer, Gerald Bender, remembered Lara on his Facebook page. He noted that Lara was known as “o duro” (a hardliner to Washington, hard to keep in line to Moscow, hardcore in terms of his discipline within the MPLA). Mostly, Bender opined, he was a strong nationalist.

Reginaldo Silva pointed to the ongoing racial issues in the MPLA that caused Lara to step away from leadership (and propelled dos Santos to the front), when he, Lara, was an obvious successor to Neto. He also recalled his role in the repression and the political narrowing that followed the 27 de Maio. Both questions inflect current political and social life. If, as according to Silva, absence defined Lara´s political life in the last 30 years, a great part of Lara’s legacy is his archive – a form of historical presence – kept by the Associação Tchiweka (Lara’s nom de guerre).

Sergio Piçarra’s daily comic in Rede Angola best captured popular discourse. That is, the contrast between the old and the new MPLA (doctrinaire Marxism-Leninism versus a capital friendly oligarch building politics) that so many articulated in their eulogies; or, Lara’s singular discipline and uprightness compared to the blurred lines of politics and economic interests, the lack of ethics, and not so up-standing behavior of today’s leadership.

This brings us to the second event of consequence: President Dos Santos´s announcement on March 11 that he will step down in 2018. Angolan writer José Eduardo Agualusa summed up the contradictions in this move in an interview with Cape Verdean radio Morabeza:

We have elections in 2017. What does this mean? If there are indeed elections, he doesn’t know if he will win or lose, so how can he say he’ll leave in 2018? …..On the other hand, if he wins, he will leave just after he’s won? That also doesn’t make any sense because it lets down those who voted for him.

The announcement has renewed the debate about succession. Given that the assumption is that the MPLA will win, who will be Vice President? The current VP, Manuel Vicente (former head of Sonangol) is in hot water, his face splashed across the international media for bribing a Portuguese prosecutor investigating a corruption case against him. The other much chatted option is José Filomeno dos Santos, Zenu, one of president’s sons and the head of Angola’s Sovereign Wealth Fund.

There’s not much news coming from from the Sovereign Fund, of late, as the price of oil is less than half of what it was when the Fund was formed to help leverage oil wealth to diversify the economy and stabilize Angola’s future.

Finally, there’s the horrendous condition of state hospitals in Angola – the main news story in Angola last week. A petition from Central Angola suggested the state take monies from the Sovereign Fund to help remedy the situation.

In the meantime, hundreds, if not thousands, of Angolans have made donations of medical supplies, purchased in local pharmacies at (anecdotally) reasonable prices (something for example that is NOT the case with food these days) to stanch the hemorrhaging. Angola is hit with an epidemic of yellow fever and a spike in malaria cases. Already chronically under-funded, under-staffed, and under-resourced neighborhood hospitals are sending more patients to the central city hospitals. One friend who dropped a donation at the David Bernadino pediatric hospital said it “smelled like death.”

A new minister of health, Dr. Luis Sambo (former WHO Regional Director for Africa), widely praised, has been welcomed with this disaster. $4 million went missing from the Global Fund via the Health Ministry. In the 2016 national annual budget, defense received as much as education and health combined, suggesting that this problem, while not intractable, will not be easy or quick to resolve.

The 15+2 await their judgement today, but most Angolans, unlike the Western media and observers, won’t notice: They are worrying about where to find sugar, how much cassava flour costs, and how to afford and find the medical supplies required for treatment in delapidated health facilities. It’s safe to say that the MPLA has not delivered on any part of its 2012 campaign slogan “grow more to distribute better.”

The economic crises in Angola

There’s a lot going on in Angola. Western media have extensively covered the trial and detention of the so-called book club (really a civic activists study group on protest) and the imprisonment of Cabinda activist Marcos Mavungo to the exclusion of other questions. The 15+2 activists, how the book club is known, and Mavungo highlighted economic mismanagement and corruption in their critiques of the government. Meanwhile, a related crisis, the government’s navigation of the ongoing economic crisis (the price of oil plummeted with no prospect of resurgence any time soon), has received less attention outside of the business press.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights enshrines economic rights – like the right to an adequate standard of living and to work. Yet most human rights organizations (Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, etcetera) opt for the more idealistic political rights – freedom of political expression, freedom of association and assembly. It may be why we don´t hear much in the international press about the economic crisis that squeezes daily life for ordinary Angolans more than politics.

Three other events since the beginning of 2016, equally as important as political human rights issues, are also shaping the political scene and refracting the economic crisis.

The first is the passing, on February 27th, of Lúcio Lara, an historic leader of the ruling MPLA during the armed struggle and first decade of independence. Lara was considered the successor to first president, Agostino Neto, but stepped aside so current president, Jose Eduardo dos Santos, could become leader in 1979 . Lara, who clashed with profligate MPLA leaders, effectively retired from politics when the MPLA made the transition from Marxism to neoliberalism in the late 1980s.

Eulogies proliferated. Many read these as critiques of the current regime.

The political scientist and long time Angola observer, Gerald Bender, remembered Lara on his Facebook page. He noted that Lara was known as “o duro” (a hardliner to Washington, hard to keep in line to Moscow, hardcore in terms of his discipline within the MPLA). Mostly, Bender opined, he was a strong nationalist.

Reginaldo Silva pointed to the ongoing racial issues in the MPLA that caused Lara to step away from leadership (and propelled dos Santos to the front), when he, Lara, was an obvious successor to Neto. He also recalled his role in the repression and the political narrowing that followed the 27 de Maio. Both questions inflect current political and social life. If, as according to Silva, absence defined Lara´s political life in the last 30 years, a great part of Lara’s legacy is his archive – a form of historical presence – kept by the Associação Tchiweka (Lara’s nom de guerre).

Sergio Piçarra’s daily comic in Rede Angola best captured popular discourse. That is, the contrast between the old and the new MPLA (doctrinaire Marxism-Leninism versus a capital friendly oligarch building politics) that so many articulated in their eulogies; or, Lara’s singular discipline and uprightness compared to the blurred lines of politics and economic interests, the lack of ethics, and not so up-standing behavior of today’s leadership.

This brings us to the second event of consequence: President Dos Santos´s announcement on March 11 that he will step down in 2018. Angolan writer José Eduardo Agualusa summed up the contradictions in this move in an interview with Cape Verdean radio Morabeza:

We have elections in 2017. What does this mean? If there are indeed elections, he doesn’t know if he will win or lose, so how can he say he’ll leave in 2018? …..On the other hand, if he wins, he will leave just after he’s won? That also doesn’t make any sense because it lets down those who voted for him.

The announcement has renewed the debate about succession. Given that the assumption is that the MPLA will win, who will be Vice President? The current VP, Manuel Vicente (former head of Sonangol) is in hot water, his face splashed across the international media for bribing a Portuguese prosecutor investigating a corruption case against him. The other much chatted option is José Filomeno dos Santos, Zenu, one of president’s sons and the head of Angola’s Sovereign Wealth Fund.

There’s not much news coming from from the Sovereign Fund, of late, as the price of oil is less than half of what it was when the Fund was formed to help leverage oil wealth to diversify the economy and stabilize Angola’s future.

Finally, there’s the horrendous condition of state hospitals in Angola – the main news story in Angola last week. A petition from Central Angola suggested the state take monies from the Sovereign Fund to help remedy the situation.

In the meantime, hundreds, if not thousands, of Angolans have made donations of medical supplies, purchased in local pharmacies at (anecdotally) reasonable prices (something for example that is NOT the case with food these days) to stanch the hemorrhaging. Angola is hit with an epidemic of yellow fever and a spike in malaria cases. Already chronically under-funded, under-staffed, and under-resourced neighborhood hospitals are sending more patients to the central city hospitals. One friend who dropped a donation at the David Bernadino pediatric hospital said it “smelled like death.”

A new minister of health, Dr. Luis Sambo (former WHO Regional Director for Africa), widely praised, has been welcomed with this disaster. $4 million went missing from the Global Fund via the Health Ministry. In the 2016 national annual budget, defense received as much as education and health combined, suggesting that this problem, while not intractable, will not be easy or quick to resolve.

The 15+2 await their judgement today, but most Angolans, unlike the Western media and observers, won’t notice: They are worrying about where to find sugar, how much cassava flour costs, and how to afford and find the medical supplies required for treatment in delapidated health facilities. It’s safe to say that the MPLA has not delivered on any part of its 2012 campaign slogan “grow more to distribute better.”

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers