Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 306

May 20, 2016

Could Angola have prevented its yellow fever epidemic?

Angola is in the midst of a yellow fever outbreak that has caught worldwide attention. Between December 5, 2015 and Monday of this week the World Health Organization reported 298 deaths and the majority of these have occurred in the capital city of Luanda. While this is the official figure, the actual number of deaths is likely much higher. Many of those who are ill never make it to a hospital or a health clinic.

The rapid spread of this rare, but deadly, disease — which can be prevented with the administration of a highly effective vaccine — is part of “ordinary,” “everyday” life in post-war African countries. As in post-war Liberia, Sierra Leone or Guinea where Ebola claimed the lives of many in 2014 (and is reportedly rising again), Angola suffers from a shortage of hospitals and hospital beds, clinics, doctors, nurses, trained technicians, vaccines, tests, and testing facilities. Like other countries that have experienced long civil conflicts (Angola’s conflict, which only ended in 2002, lasted for 27 years and was preceded by 14 years of anti-colonial war), the country presently does not have the capacity to deal with “the extraordinary” such as a yellow fever outbreak.

Diagnostic capacity is also weak in post-conflict Angola. An assessment conducted by Norway’s Christian Michelsen Institute (CMI) in 2011 of the ability of health care workers to correctly diagnose a number of common illnesses in Angola produced alarming findings. Using patient simulation cases whereby health workers were asked to make a diagnosis based on a set of common symptoms exhibited by a hypothetical patient, CMI found that half the time, diagnoses by a sample of health workers in Luanda were incorrect.

Two thirds of the time, health workers in Uíge, a city in the northeast of Angola, incorrectly diagnosed simulated cases of acute diarrhea with dehydration, malaria, pneumonia and other “typical” diseases.

The health care system in Angola may be even worse off than many other post war countries because the usual assortment of humanitarian aid from non-governmental organizations and donors that arrives after a conflict have barely materialized. After helping to bring under control a terrible outbreak of Marburg virus, a hemorrhagic fever almost as deadly as Ebola, Medecins Sans Frontières reportedly packed up and closed its offices in Angola in 2007.

In December, 2015, USAID officials in Luanda indicated to me that they were facing budget cuts which would likely affect American aid to Angola’s health sector. Indeed, USAID’s projected budget in Angola for 2017 indicates a reduction of 17% available revenue over the past two years. At the same time, it doesn’t appear that USAID has shifted its funding priorities in response to the recent yellow fever outbreak. Its webpage for Angola — last updated two months ago — makes no mention of support for addressing the outbreak of yellow fever.

The paltry overseas development assistance for post-war Angola is lamentable, but in another respect, the current health crisis is very much a crisis of the Angolan government’s own making. It is a product of lavish spending on the wrong projects, conceived and completed in the wrong order in the 14 years since civil conflict ended in 2002. It is the result of top down decisions regarding public spending priorities by government officials cloistered away in air conditioned offices and luxury residential enclaves. According to the World Bank, health care accounted for only 3.6% of the government’s budget on average from 2011-2015 compared with 6% of the budget in Mozambique and 11% in Sierra Leone, two other post war countries.

As the many public billboards dotted around the city of Luanda are keen to stress, the government has financed new housing projects, built new hospitals, supplied water, and extended and repaired road networks. All of these developments arguably improve public health. But the upgrading of informal urban settlements, rather than building from scratch, would have been more cost effective and benefitted a larger number of residents. Also much government expenditure since the end of the war has been on the symbolic instruments of power rather than on the ordinary necessities of urban life. It has been directed at constructing the new legislature, built to resemble the US Capitol, or the new Palace of Justice, inaugurated in 2012.

The current crisis is also the consequence of a failure to reorganize budgetary allocations when the oil boom turned to a bust last year. In the wake of the collapse in oil prices, foreign currency, which is critical to the purchase of imported goods such as medicines, has dried up. The kwanza has lost a third of its value in relation to the dollar over the last year and informal exchange rates are even lower. Angola’s GDP is half what it was two years ago. But that doesn’t seem to have affected the continued appropriation of a large percentage of the state’s revenue by the elite, while the rest of the country suffers.

Luanda is particularly hard hit by dwindling revenues: a quarter of the country’s total population lives in the capital in overcrowded, informal housing. Many residents lack reliable access to safe drinking water and sanitation is often inadequate. In some areas, garbage collection seems to have ceased. All of these conditions facilitate the rapid transmission of disease. Fiscal austerity means less revenue to construct and repair storm drains, which would help control the breeding of mosquitoes. It means less money for continued improvements to infrastructure such as water distribution and sewerage systems. It means less money to pay for garbage collection, road building, and most of all, convenient, fully staffed, public health clinics with proper labs.

The strains on residents of Luanda (not to mention those living in rural and urban areas in the rest of the country where health facilities are fewer in number and even less well supplied), must be great. Reports of two to three hour commutes to get to the nearest hospital and long waiting periods to be seen by physicians abound. At government expense, seven million people in and around Luanda have received yellow fever vaccinations, but the virus is spreading and the supply of available vaccines is insufficient to cover the rest of the country. Now the virus has been reported in Democratic Republic of Congo and there is a real threat of transmission to Namibia and Zambia. Recently, an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association stated that the yellow fever outbreak could become a “global emergency,” owing to the shortage of vaccines. Not surprisingly, such claims by a respected medical journal have generated a mild moral panic and been repeated by major news media such as The Economist. Sadly, in spite of the high number of deaths, the Angolan government has yet to declare this tragedy even a “national emergency.”

May 19, 2016

The state of Nigeria’s (live) music industry

Fans at Gidi Music Festival

Fans at Gidi Music FestivalWith the burst of Afrobeats on to the international scene, much of the world now looks to the Nigerian music industry as the leading charge to establish a permanent African presence on the global pop landscape. In spite of these successes, several players in the local entertainment industry have identified bottlenecks in the Nigerian music scene, and are looking at ways to improve the business that surrounds it.

On a recent trip to Lagos for Gidi Music Festival, I was fortunate to have two separate yet overlapping conversations about the state of the Nigerian music industry. Chin Okeke and Teme Banigo, co-founders of Gidi Music Festival, explained to me that they are trying to raise the bar in terms of music performance in Nigeria. They are doing this by prioritizing live acts over pre-recorded and playback sets.

For those who don’t know, it is rare in much of Africa to see a festival line-up of both established and up and coming artists performing with a full band. On the contrary at Gidi Music Festival, this was a common occurrence. To add to their successes promoting live music through the festival, Chin and Teme’s longer term goals also include opening up mid-sized venues to expand the live music offerings in Nigeria.

Later on my trip I spoke to Jenny Tan, co-founder of Lagos Music Conference, a 2-day event taking place in Lagos this weekend. Jenny’s thoughts illustrate that the conference is sure to stir up a lot of debates in regards to how music is handled both in and outside of Nigeria.

D’Banj at Gidi Music Festival

D’Banj at Gidi Music FestivalThe following interview excerpts contain highlights from these two discussions:

What’s the live music landscape in Nigeria today?

Chin: There’s a lack of infrastructure. What was here in the 1960s and 1970s has been entirely dilapidated. We’re now building up. Most events are sponsorship-driven. If you look at the event space, you’ve got weddings, normally one person foots the bill, or if it’s a branded event, the brand foots the bill. Technically, it doesn’t generate money.

What about venues?

Jenny: There are no medium size venues, so if you’re not an A-list artist, and want to go on a national tour, it’s really difficult. In Lagos you might just about find something, but outside Lagos it becomes really difficult, because either you are looking at stadiums or you’re looking at clubs.

Chin: There’s a lack of venues, we have hotels and tents, some can seat 2,000 people. There are no arenas, and this is an area we want to move into quickly. Right now we’re working on a site that we don’t own [for Gidi festival], but we want to look into acquiring land and building it up, developing the festival and around the festival.

What about promoters?

Jenny: There are also no promoters: not many artists pull a crowd; fans are not particularly loyal or specialized. Mainstream music does not have die-hard fans, so most artists alone are not able to pull a crowd. So if a promoter wants to put on a show, they have to bring the big guns, which you can only do with big sponsors.

Chin: We don’t have promoters in Nigeria because we don’t have enough venues. The cost of putting together a production at the venues we have can never make sense if you look at the numbers. Renting out Eko hotel costs US$80,000, it seats 3,000 people, so if you charge US$50, the numbers never add up.

Jenny: Our system is kind of broken. As a promoter, you look at the potential revenue you can make. You budget about 50% on production, and 30% is supposed to go to the artists. If you were to book talent and apply this formula, nobody can put together an event here, because the artists are too expensive to support the industry. There’s a real disconnect between money they expect and the money they would get without a sponsor.

So the only way to make it work is to do it with sponsors, and I imagine this approach has its own challenges?

Chin: Most brands don’t get it. Their idea of success and their criteria are so warped, because they pay attention to the wrong details. Some brands just want their logo on a flyer, they’re not about creating an experience. Then you have brands who are just interested in the 20 VIP tickets.

Teme: we have brands of consumer goods more interested in the red carpet aspect, instead of their customers’ experience.

Chin: for Heineken, all I had to do was show the brand manager a few things trending, she saw how much engagement had come from a simple event. They do more research, pay attention to the customer experience. Rather than just ask to have their logo everywhere.

Jenny: 90% of events are branded shows. The promoters are the sponsors, they mostly care about banners, VIP seats for the management teams, etc. Nobody cares about the experience.

Yemi Alade at Gidi Music Festival

Yemi Alade at Gidi Music FestivalIt sounds like this system doesn’t push the music or experience?

Jenny: There’s no curation of content. Recently a promoter tried to convince me to put so and so on the bill for an event I was organizing, “otherwise people won’t come”. As opposed to saying for instance, we just want the real hip hop fans, and you put together a hip hop line up. Then you’ve got the hip hop crowd. But what we see is a little bit of everything, and the die hard fans don’t want to go, because they will feel like they’re wasting their time and money.

The fact that people never have a great time, and never share a great experience with fellow fans, makes people not want to attend shows. Most shows start late, drag on til late, it makes it costly or dangerous to go home. It’s a mostly shitty experience to go to a large event. Sometimes they run out of drinks, or don’t even sell drinks altogether. Not to mention security guys treating every single people in attendance like they’re football hooligans, girls getting harassed or robbed. So the overall experience is… not great.

Chin: As long as there are people like us ready to up the game, it will continue to grow. Not as fast as we wish because there aren’t enough platforms, but it’s growing.

Teme: In Nigeria we have an environment where we copy success, so as we grow, people look at our model and try to mimic it. If you even look at what’s happened since we started Gidi Festival, we’ve literally seen other events now calling themselves festivals! So I feel that as our model becomes more and more successful, the industry will lean towards this model of live entertainment. I think artists will now be forced to have a live act that will be more attractive to promoters like us.

It sounds like you all agree that Nigeria needs good promoters and more variety in music?

Chin: The industry is evolving, people are watching, production’s gone a long way. But again there’s a lot of top line and very little bottom line. Everybody’s running with it, it looks great, but there’s very little underneath. Everything sounds the same, so the next wave will be stuff that sounds different, that’s what people will be buying into, just because the other stuff is not sticking anymore. Right now I think we just need a few more people to guide the industry, to be responsible for taking decisions, for deciding what is good or bad, what needs to be done. There’s a storm brewing, there’s the mainstream and there is the stream which influences the main. That’s the idea behind the Collective.

Teme: the audience can now be critical, once they’ve been exposed to better, they can be more critical.

Jenny: When I did parties in New York City, we wouldn’t promote on a Clear Channel radio, we’d promote through the scene. Same thing goes for the music at LMC festival. We’ll drill down social media analytics, we’ll find fans who commented on Kid X’s content, we’ll geotarget, then we’ll let these people know the artist is in town. With a line-up of 15 artists, if you find the fans, if each artist pulls 100 fans, then we can pull a crowd. We don’t need to speak to everybody.

What we are doing this weekend is pioneering in a totally different way, we have booked a non-commercial, non-mainstream line up, but it’s not aspiring artists, it’s good music, it’s curated to fit together. I’m now going to have to prove that it is in fact possible to pull a crowd specific to a genre, and prove that curation can help fill the space.

May 18, 2016

Student protests and postapartheid South Africa’s negative moment

The political theorist Achille Mbembe, from the University of the Witswatersrand in Johannesburg, describes South Africa as experiencing a “negative moment.” Though protest and dissatisfaction with the terms of the “new” South Africa have been brewing for some time, there is a strong sense that the black majority is losing patience with the ruling African National Congress. The student protests, which engulfed campuses for much of 2015, while limited by its narrow base and focus, gave a glimpse of what it could look like if the black majority turned on the ANC.

South Africa’s democratic system is twenty-two years old. The ruling African National Congress (ANC), once a liberation movement, has been transformed into an ordinary political party encumbered by an election cycle mentality, and the largesse of the state. The party also presents a paradox: Dissatisfaction with it and government are at all time highs. Much of the rancor is reserved for the country’s president, Jacob Zuma (2009-), whose regime is associated with the widespread corruption of state institutions and party structures. Yet, the ANC continues to command electoral majorities nationally, and holds executive power in eight of the nine provinces. The exception is the Western Cape, governed by an opposition party, the Democratic Alliance. The ANC also controls all major metros, i.e. large cities, except for one (Cape Town, also run by the DA).

Because of the relative weakness of opposition parties, the fragmentation of the opposition landscape more generally, and the ANC’s continued national dominance, the preferred forms of political opposition are street protests, including wildcat strikes, by workers.

Protests and disruptions are not new in the “new” South Africa. But after an initial honeymoon period (which concluded with the retirement of Nelson Mandela from elected office), protests become synonymous with democratic politics in South African politics.

Between 1999 and 2003, those protests took the form of either service delivery protests or more well organized “social movements.” The former were very local, often spontaneous, mostly parochial, short-lived struggles over housing, electricity and housing evictions. The latter were more planned, media savvy, drew on the language of struggle, allied to the ANC, brought back the language of the antiapartheid struggle and asserted new constitutional rights. The movement for access to affordable AIDS drugs and treatment, led by the Treatment Action Campaign is the best example. The TAC produced what was South Africa first post-apartheid, progressive—and crucially multiracial and national—movement outside the ANC and the trade unions, and forced concessions from the state through the court system.

By the mid to late 2000s, more sporadic, and very violent protests, characterized by retaliatory police violence became ubiquitous. Police violence against protesters were commonplace, so was the security services spying on activists.

But throughout this period, the ANC retained its legitimacy as the guarantor of the post-apartheid settlement. By this I mean the series of political, social and economic deals in which the racial inequalities of Apartheid and wealth disparities largely remain intact and which benefits whites in general. South Africa remains the most unequal country in the world with high levels of unemployment, much of it structural, disproportionately concentrated within the black labor force. At the same time, the ANC promised a better life to black South Africa. To some extent they’ve delivered on it: 45% of households now receive some form of social assistance, more children are enrolled in schools and the government has embarked on an ambitious affirmative action project, creating a black middle class numerically equal the size of the white population.

Then came the fateful events in August 2012 at Marikana, a mine owned by a British multinational in which the country’s current deputy president, Cyril Ramaphosa, was a non executive board member. Police—under pressure from the mine company and the minister of police—murdered 34 striking mine workers in broad daylight. The events shocked South Africa though it, crucially, didn’t result in mass protests. The government subsequently held a public commission which disappointingly did not hold anyone specific accountable, but its symbolism wasn’t lost on South Africans and South Africa watchers. As Dan Magaziner and I wrote on “The Atlantic” magazine’s website in 2012: Though public discourse in South Africa refuse to acknowledge this, Marikana also marked the end of South African exceptionalism. South Africa’s problems are no longer specific to the apartheid legacy, but about more global issues of poverty and inequality, labor rights, corporate responsibility and the behavior of multinational corporations.

In subsequent national and provincial elections in 2014, the ANC retained its electoral majority, but the Economic Freedom Front (EFF), formed merely a few months earlier, gained about 6% of the national vote. Since then, the EFF has replaced the Democratic Alliance as the effective parliamentary opposition in the public’s mind. They use a mix of carnival (they dress like Chavistas), mass protests (they succeeded in getting 50,000 people to march from downtown Johannesburg to the city’s financial quarter where banks and the stock exchange is located) to disrupting parliamentary politics (getting kicked out of the chamber, shouting for President Zuma “to pay back the money” and publicly mocking his association with a wealthy business family).

The student protests are a reflection of this wider unease.

South Africa has 23 public universities, which includes some technikons since upgraded to university status. Most students in higher education institutions are black—a result of the new government’s expansion of college access. While students at historically black universities (like Tshwane University of Technology or the University of the Western Cape) had been protesting over fees and outsourcing of service jobs on campuses, it would be protests over symbols at UCT and Rhodes that would kickstart the student movement. In March, at UCT, students protested the prominence of a statue of Cecil John Rhodes, a divisive colonial figure, while at Rhodes they objected to the name of the university. Those protests morphed into demands for more diverse faculty and to “decolonize” curriculums.

By midyear, the protests linked up with trade unions opposing outsourcing on campuses, and by year end they demanded, first, a freeze on fees increases, and simultaneously free, public higher education. In late October 2015, after students had marched to his office in the capital Pretoria, Zuma announced there would be no fee increase. The movement was distinctive for its use of social media, highlighting patriarchy and sexual abuse in black movement politics, openly questioning the hegemony of the ANC and the failure of the new South Africa to deal with racial and class inequality.

Since the end of 2015, as the essayist TO Molefe (who is sympathetic to the students) has noted in “World Policy Journal,” the student movements have stalled somewhat: “Revolution as becoming isn’t only about what society and individuals should become; the protesters mostly appear to have that part down pat. They want freedom, for real this time, for themselves and those like them. But there is also this perhaps most important question at the center of this principle: How do you co-exist with those whose outsized power you’ve just overthrown?”

Similarly, the insistence on horizontal forms of organization, may hamstrung the students: Everyone is a leader. There is no national, coordinated structure, but a series of movements and allies that draw on student groups, the youth wings of mainstream political parties and SRC’s. As a result, groups like the EFF and the even smaller PAC, a black nationalist party that is relatively marginalized in both liberation and postapartheid politics, have made comebacks among students.

Black racial solidarity is foregrounded in some cases (the movements at UCT and Wits University inhibit white student involvement), but obscures differences in the issues faced by students depending on where they are located in the class structure that is South Africa’s higher education system. The issues and conditions of a black student at UWC is very different from her counterpart at UCT. Similarly, the state has employed significantly more violence in its response to protests at historically black universities where there’s less media coverage and very little middle class outrage.

Then there’s the terminology. The students prefer “decolonization” to “transformation,” the latter preferred by the state and university administrations. But even then, “decolonization” remains an elusive term. It is a big catchall, encompassing symbolic politics, white supremacy, curriculum, patriarchy, demands for diverse faculty, language politics, fees and free public higher education, among others.

Currently, students on some of the elite campuses (most notably Wits, UCT and to some extent Rhodes) are embroiled in internecine battles over sexuality, gender and class.

Finally, and this is a crucial point, less we overstate the extent of this rebellion: The students represent a minority. South Africa’s labor force is characterized by low numbers of college graduates. There are only about one million students enrolled in the university sector out of a population of 54,9 million people. This raises the question of the linkages of these student movements to the larger unease in the society or to link up with causes and groups beyond campuses.

Nevertheless, the student protests coupled with the growing appeal of the EFF and the restructuring of the trade union movement (the largest union federation split) represent an interesting political moment for South Africa. Until now the most vocal opponents of the ANC government in the public sphere were middle class whites. What the student protests have achieved is perhaps point to a possible break in the ANC’s middle class black support (who up until now was solidly for the ruling party) and that, more than street protests in faraway townships, they represent a greater threat to the ANC’s hegemony and, more crucially, the party political system.

* This essay was first published in the May issue of the Africa Workshop Newsletter of the American Political Science Association. The issue focused on the politics of higher education in Africa.

May 15, 2016

‘Fantastically Corrupt’

British Prime Minister David Cameron told Queen Elizabeth II this week that Nigeria and Afghanistan were “fantastically corrupt.” Make no mistake, Nigeria and Afghanistan are corrupt. It’s just ironic coming from Cameron, a beneficiary of tax dodging. But beyond Twitter banter, there is a case to be made that it is actually the UK (and other western countries) that are at the center of the global corruption nightmare. Corruption then, much like beauty, seems to lie in the eyes of the beholder. So who’s the most corrupt of them all? We try to figure this out this week. But like beauty it’s complicated.

(1) First up, where in the world did David Cameron get the idea that Nigeria and Afghanistan were some of the most corrupt countries in the world (and by implication the UK was squeaky clean)? Well, having only a few seconds with the Queen, Cameron didn’t go into the finer details of referencing his source. But we think he got this idea from the famous Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) that’s been reported every year since 1995 by Transparency International. For 2015, the CPI ranked a 167 countries from least corrupt (number 1) to most corrupt (number 167). Nigeria and Afghanistan were ranked 136 and 166 respectively. Cameron’s the UK was ranked 10th.

So going by the CPI Cameron is right, right? Well, what Cameron doesn’t know (or pretends not to know) is that the CPI is riddled with serious methodological problems that raise questions about its usefulness. We cover some of these below.

(2) Much like a beauty pageant with judges subjectively scoring nervous contestants, the CPI is derived by asking “experts” on their “perceptions” of corruption in different countries. And who are these experts, we hear you ask? Alex Cobham of the Tax Justice Network has a useful listing:

[A] group of country economists,” “recognized country experts,” “two experts per country,” “experts based primarily in London (but also in New York, Hong Kong, Beijing and Shanghai) who are supported by a global network of in-country specialists,” “staff and consultants,” “over 100 in-house country specialists, who also draw on the expert opinions of in-country freelancers, clients and other contacts,” “4,200 business executives,” “100 business executives … in each country,” “staff,” “100 business executives from 30 different countries/territories,” “staff (experts),” “100 business executives per country/territory,”…

So the CPI is obtained by aggregating the noise of a tiny set of global elites whose opinions are likely shaped by what they read in elite Western media or those stories brought back home by John from his recent business trip to “Ayngola”.

If you’ve ever been unfortunate enough to attend a cocktail party, then you know that the global elite are not known for having diverse opinions, let alone original ones.

(3) So what happens when the opinions of a global globetrotting elite are stacked up against those of the everyday citizen, the type of citizen the elite are trying to protect from corruption? Well, you get a vastly different picture. Here’s Alex Cobham once more:

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the view changes when the experiences of a group of a country’s citizens are considered instead of restricting the view to elite perceptions only. [University of Minnesota law professor Stuart Vincent] Campbell writes that, in contrast to the CPI ranking which in 2010 put Brazil 69th, behind Italy and Rwanda, “The 2010 Global Corruption Barometer [based on a broader survey of Brazilian citizens] found that only 4 percent of Brazilians had paid a bribe, which is a lower percentage of bribe-givers than the survey found in the United States or any other country in Latin America.

(4) It’s this increasing awareness of the uselessness of perceptions-based measures that’s led the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) to call for a rethinking of how we measure corruption particularly in Africa:

The current predominantly perceptions-based measures of corruption are flawed and fail to provide a credible assessment of the dimensions of the problem in Africa…The present report calls upon African countries and partners to move away from purely perceptions-based measures of corruption and to focus instead on approaches to measuring corruption that are fact-based and built on more objective quantitative criteria.

(5) Back to David Cameron and his gaffe: President Muhammadu Buhari of Nigeria reacted to it by saying he didn’t want an apology from Cameron. All he wanted was a return of stolen Nigerian assets held in British banks, suggesting that Britain was itself a facilitator of corruption. But is Buhari right?

(6) Here’s economist Jeffrey Sachs writing in the Guardian this past week:

The UK and the US are at center of the system of global abuse. Britain created the modern world of global finance in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and Wall Street became co-leader with the City of London after the second world war. In both countries, hundreds of thousands of lawyers, bankers, hedge fund operators, politicians, accountants and regulators have consciously built a system of global tax havens of the rich, by the rich, and for the rich that now hosts more than US$20tn (yes, trillion) of funds hiding from taxes, law authorities, environmental regulation and accountability.

(7) Or according to the Brookings Institution:

For those seeking secret shelters and corporate shells, the mighty U.S. (which unsurprisingly doesn’t feature much in the Panama Papers) is one of the world’s most appealing destinations: Setting up a shell corporation in Delaware, for instance, requires less background information than obtaining a driver’s license… And the U.K. is an important enabler of corruption: It has stood by as its offshore jurisdictions and protectorates operate as safe havens for illicit wealth, which the Panama Papers make clear. The British Virgin Islands, for example, were the favored location for thousands of shell companies set up by Mossack Fonseca.

(8) Friends, no matter how hard you try, those US$5 “gift payments” you made to the police officers at the last checkpoint will never come close to the type of grand-scale corruption detailed in (6) and (7).

(9) And let nobody cheat you that tax havens serve some type of justifiable economic purpose. They don’t. It’s just good old fashioned theft.

(10) Oh, by the way, as we mentioned at the outset that the Honorable David Cameron is himself a beneficiary of tax dodging?

Yes, the whole thing’s a mess. Our heads are also spinning. We best leave it here. Here’s to wishing everybody a corrupt free week.

May 12, 2016

Africa’s Premier League

Africa is a Country is excited to present to you, loyal reader, the Kickstarter campaign for our very first full-length documentary film project.

It’s called “Africa’s Premier League,” it’s going to be a blast, and we’d love to have you on board.

Here’s the lowdown:

Africa is obsessed with the English Premier League. The continent may be divided by old colonial borders, thousands of different languages, and major cultural, political and economic differences. But Africa is united every weekend around the spectacle of English football. Love it or hate it, it’s one of the things that brings people together.

The everyday lives of Africa’s football fans are all different. Yet they share a long-distance love affair, with all the hopes, fears, joys and sadness that comes with it.

If it’s not Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame taking time out to tweet his views on his beloved Arsenal (or TB Joshua making “prophecies” about upcoming matches), then it’s the millions of ordinary Africans across the continent who are glued to TV sets in bars and bespoke viewing centres, from tiny villages to heaving mega-cities like Lagos or Kinshasa.

We want to show, in depth and detail, exactly how English football fits into the ordinary lives of African supporters.

Our film will tell the story of Africa’s passion for the English Premier League, through the eyes of the fans themselves.

Here’s the trailer:

If you love what we’ve been doing at Africa is a Country all these years — bringing you that fresh, incisive analysis of African politics and culture — you’ll love AFRICA’S PREMIER LEAGUE. We’ve never asked our readers for money before, but we need your support in getting this project off the ground.

AFRICA’S PREMIER LEAGUE follows four fans – in Nigeria, Kenya, South Africa and Congo – as they live through the highs and lows of a football season, and explores the overwhelming attraction of English football in Africa.

AFRICA’S PREMIER LEAGUE will be a feature-length documentary film, a web series & a TV series.

With your help, we will take our crucial first step: making a high quality short teaser film on the life of an EPL fanatic in Cape Town, South Africa. We’ll use that to win big backers and distribution for the full-length project.

To help us, go donate here.

This film is about revolution

In the five years since the start of the so-called “Arab Spring,” as poverty, repression, and extremism have continued to impact daily life throughout the Middle East and North Africa, a civil revolution has quietly flourished, one that is complex, creative and marked by discontent. There is, of course, no simple way of describing, or even of dating recent revolutionary movements in the region. When did they begin, and is it remotely accurate to suggest that they have “succeeded” when, in many instances, the status quo remains seemingly undisturbed? Western media outlets may appear to crave simplistic accounts of revolution in the global South, imposing grand narratives as they cover major (typically violent) events, and implicitly suggesting the cessation of revolution by bringing reporters back from a seemingly stabilizing field and discouraging further coverage.

That journalistic accounts of the Arab Spring are now difficult to come by, at least compared with the glut of such accounts in 2011, is one reason westerners may suspect that Arab League countries are now characterized by an emphatically “post-revolutionary” moment – an experience of relative calm. Another, thornier reason may have something to do with the sheer difficulty of defining “revolution” in the first place, particularly in those parts of the world where multiple modes of censorship reign. Who, ultimately, can speak with authority on recent events in Egypt, and, more importantly, how?

Egyptian protesters try to tear down a cement wall built to prevent them from reaching parliament and the Cabinet building near Tahrir Square, in Cairo, Egypt, Thursday, Jan. 24, 2012. Image Credit: Hussein Tallal (AP Photo)

Egyptian protesters try to tear down a cement wall built to prevent them from reaching parliament and the Cabinet building near Tahrir Square, in Cairo, Egypt, Thursday, Jan. 24, 2012. Image Credit: Hussein Tallal (AP Photo)Egyptian filmmakers are, at present, in a particularly complicated position, whether they remain in Egypt or live abroad. With European festivals and funding sources still clamoring for anything that smacks of an “authentic” representation of the Arab Spring, it is almost axiomatic that, by including the word “revolution” in a film’s title or description, Egyptian filmmakers will receive attention, financing and even major awards for their efforts, whatever their practical and ideological relationships to revolutionary action. Emerging from this exoticizing interest in the “Arab Spring” are, inevitably, certain prescriptions for filmmaking – dominant ideas about what, exactly, a documentary on the subject must “be” or “do.”

Jehane Noujaim’s rapturously received The Square (2013), which enjoys the imprimatur of both Netflix (its distributor) and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (which nominated it for the Best Documentary Oscar), is emblematic of the type of film that embraces a charismatic cast of characters through which it frames, personalizes, and even seeks to “master” history. Indeed, The Square presents its protagonists not just as characters in a drama but as individuals with arcs – psychologized trajectories that help the film to narrate the revolution as a living organism with a spectacular birth, awkward adolescence and troubled adulthood. Thus, when the glamorous Ahmed Hassan, having taken a long, luxurious drag on his cigarette, turns to the camera and says, “Let me tell you how this whole story began,” the confident sweep of his declaration references both his intimate self-knowledge and his expansive comprehension of Egyptian revolutionary events. The viewer is expected to trust Hassan’s account of these events as a reflection not simply of his own lived experiences but also of a certain command of history – of how, precisely, “this whole story began.”

Image Credit: Suhaib Salem (Reuters)

Image Credit: Suhaib Salem (Reuters)Shadowed by the global critical success of The Square are numerous documentaries that take a dramatically different approach, many of them by refusing mention of the “Arab Spring” and instead centralizing the struggle to produce creative works during altogether confusing and contradictory revolutionary times.

“It will hit you without warning, and simply carry you away.” sings Gil Scott-Heron in “Third World Revolution.” For filmmaker and scholar Alisa Lebow, such carrying away might well describe the experiences of the participants in her project Filming Revolution, many of whom claim to have moved past the point at which they could conceivably offer any easy answers or linear narratives to explain revolutionary movements, whether to outsiders or to themselves.

Described as “a meta-documentary about filmmaking in Egypt since the revolution,” Lebow’s project has culminated in a website that brings together filmed interviews with 30 Egyptian filmmakers, artists, activists, and archivists, along with examples of key creative works. An illustration of what Lebow calls “interactive documentary,” the website allows users to make their own connections among its thematically organized components, inscribing idiosyncratic research pathways either anonymously or by logging on via Twitter. The site thus positions visitors not as passive recipients of the sort of knowledge that in conventional documentary fashion The Square seeks to construct and impart, but as active agents in an ongoing struggle to scrutinize the innumerable, unheralded intersections between art and activism in Egypt.

Filming Revolution began as a curated set of films for the Istanbul Film Festival, at a time when Lebow was hoping to bring together any audiovisual works remotely related to the term “Arab Spring.” She was also struggling to contextualize Egyptian revolutionary films in relation to earlier examples of revolutionary documentary and documentary-style fiction, from Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1967) to Patricio Guzmán’s three-part The Battle of Chile (1975, 1976, 1979). Eventually opting to move beyond the practical and ideological limitations of both the film-festival circuit and the scholarly monograph, Lebow traveled to Egypt in December 2013 and began conducting interviews there. Arriving just four months after the Rabaa massacre, Lebow encountered what she called “revolutionary fatigue” – a distinctive feeling of lethargy occasioned, in part, by Egypt’s recent state of emergency and associated curfew.

Many of Lebow’s interviewees, selected because they had participated as Egyptians in various revolutionary actions, claimed to be adamantly opposed to the notion that a film could adequately capture, let alone communicate, the fervor of revolution. In interviews accessible on Lebow’s website, they eloquently convey their aversion to tendentious filmmaking strategies – those that disingenuously present revolution as narratable, generating documentaries that are taken to be authoritative examples of historiography, rather than works that question received knowledge, including about documentary itself. In its rhizomatic dimensions, Filming Revolution is an endlessly stimulating index of Egyptian creative practices, and a profound challenge to anyone willing to offer a tidy description of what mainstream journalists continue to call “the Arab Spring.”

May 11, 2016

No place like home for the “go-home blacks”

When an African is forced to leave home – from Somalia, Nigeria, Eritrea or any other country where their lives may be endangered – they know the risks. They know they may find themselves trapped in a refugee camp, waiting often for years to find permanent residence. They know they face a minimum of a month-long trip across the Sahara, called “bahr bila ma” (the sea without water), before reaching the Mediterranean. They know they may get lost in this desert, or run out of water and be forced to drink Benzene. They know they may be held for ransom, and tortured by the smugglers hired, supposedly, to escort them to safety.

If they make it to countries with ports, like Morocco, Algeria or Libya, many live in forest encampments, working multiple jobs to fund the trip across the sea before being extorted again. And once they arrive in Europe, if they haven’t perished at sea, they’re often branded mere economic migrants and are refused asylum before being deported back to the place they fled. Desperate, many will take the trip again across the Mediterranean. And many more follow them.

A recent report reveals there’s been an 80% increase in the number of refugees arriving in Italy compared to the first three months of 2015, with Nigerians, Gambians and Senegalese making up the largest numbers of asylum seekers.

The experience of the typical African refugee is one of rejection, inevitable denials of asylum, and being confronted by persistent anti-African sentiment. Despite this, and the fact that Eritrea, Nigeria, Somalia, Sudan, Gambia and Mali are among the top 10 countries that people are fleeing, Africans are still largely erased from the discussion around the refugee crisis. Instead they pad the ballooning numbers of victims and receive little support in return.

This kind of erasure is not limited to countries in western Europe, where many African refugees first land. We’re seeing similar patterns here in Canada. In late March, when the new federal government revealed its budget, it included a commitment of $245-million to resettle 10,000 Syrian refugees, which is in addition to the 25,000 it had already fast-tracked. We support this action and many other Africans do as well, but something’s wrong with this picture.

Many will say that Syria produces the largest number of refugees and so, they deserve preference. It’s certainly true that Syria ranks as the most affected, but, while we remain in solidarity with all displaced people, we shouldn’t practice a first-past-the-post humanitarianism. Africans are a part of this crisis and if the federal government will make commitments to some it should make them to all.

If you want to privately sponsor a refugee in Canada, there are currently no limits for Syrians. This is also commendable, but Africans face the detrimental effects of caps on private sponsorships and incredibly long delays (often years) in the processing of their applications. Not only have applications of specifically African refugees been put on hold, but also some refugee offices such as the Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto have begun turning away new applications submitted on behalf of African refugees. There are reports of families separated, with children waiting for years in refugee camps while their parents are settled in Canada. The longest delays are for the 18 African countries covered by the Nairobi visa office. Most privately sponsored refugees through that office wait more than three years, and, according to the Canadian Council for Refugees, “rather than increasing the numbers of African refugees to be admitted, the Canadian government has asked private sponsors to submit fewer applications at the Nairobi office.”

Canada’s response to refugees has become less global, neutral, and principled and more targeted. It’s within this selection process that African refugees are systematically excluded. It leaves many marginalized populations outside of the dialogue, further dehumanizing them. If and when these refugees finally reach Canada, they’re usually offered loans to help cover the costs of transportation fees, medical services, and sometimes even first month’s rent. These loans, which are typically paid with interest, are often as high as $10,000. Paying them back means working longer hours and postponing their education in a new country. In contrast, Syrian refugees arriving in Canada after November 4 don’t have to pay back their loans.

Last year, when those images of toddler Aylan Kurdi made it to the front pages of the world’s papers, we were as moved as anybody. And when rallies in support of refugees across the globe were organized, we supported and marched as well. But the truth is that some of us have seen images of washed up African toddlers for years. For some of us, Kurdi was one of many. For some of us, the rousing call from governments and settlement organizations and community groups of “refugees welcome”, was welcome but surprising, as there has been no such commotion when Africans drowned. Indeed, we wonder, with anger and disappointment, why the settler-colonial, Canadian state and our own allies remain silent as Africans continue to die; why we have been rendered what the poet Warsan Shire calls “the go home blacks.”

May 9, 2016

Reading maps, the interventionist state and another $15 billion missing from Nigeria’s government

This week is about charts.

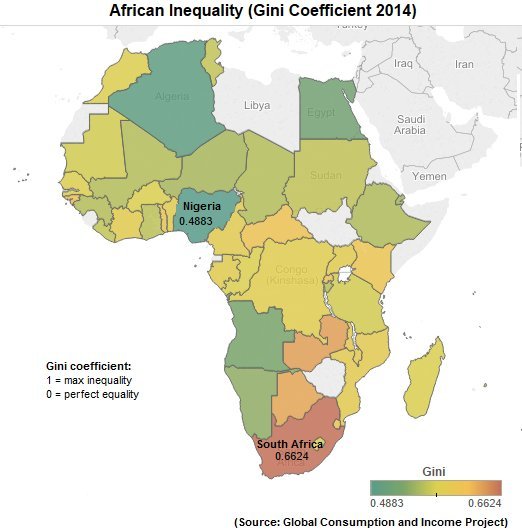

(1) First up, is the chart below from the newly launched Global Consumption and Income Project (GCIP) spearheaded by Professor Sanjay Reddy of the New School for Social Research. (We’ve written before about Professor Reddy’s work challenging the World Bank’s poverty estimates here.) The chart shows levels of income inequality across African countries for the year 2014 (most recent year with available data). Inequality is measured using the Gini Coefficient which measures inequality on a scale of zero to one. (A Gini closer to zero means low inequality while that closer to one means high inequality.)

Surprisingly, Nigeria, with a Gini of 0.4883, has the lowest level of inequality on the continent. Unsurprisingly, South Africa, with a Gini of 0.6624, has the highest inequality measure on the continent. The other countries fall somewhere in between these two extreme cases.

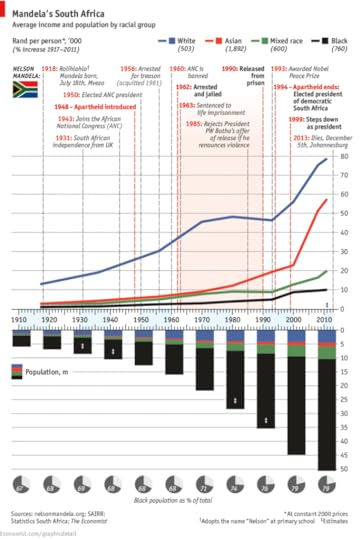

(2) The second chart, just below, digs into the underlying factors behind South Africa’s high inequality. First published by The Economist in December 2013 (after Nelson Mandela’s death), it shows, among other things, the evolution of average incomes per person across different racial groups in South Africa from 1917 to 2011. The first takeaway from the chart is that before the official ending of apartheid in 1994, average incomes for whites rose at rates that were considerably higher than those of other racial groups (see the blue line) – unsurprising as this was Apartheid’s main aim. The second takeaway is that the “freedom bonus” largely accrued to whites only – their average incomes nearly doubled over the period 1994 to 2011. This too is unsurprising as the opening up of South Africa’s economy after 1994 was only going to benefit those who had previously been privileged in accumulating capital (real estate, land, equity, savings, etcetera) and skills.

The chart is a great antidote to those who think history doesn’t matter in South Africa. We are especially looking at you, yes you, the choir that likes to sing the “black people are just lazy” song. (H/T to Josh Budlender on Twitter)

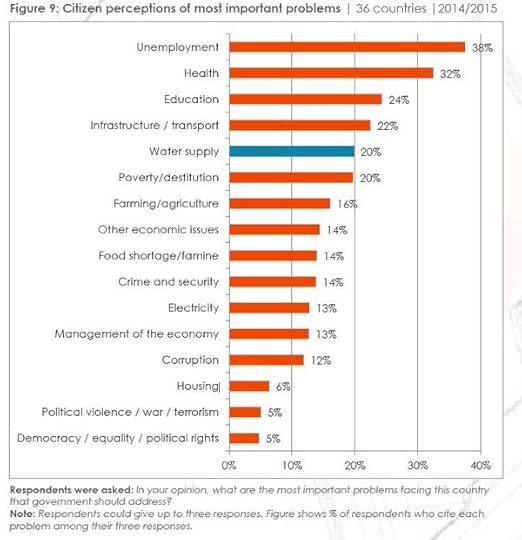

(3) The next chart is taken from Afrobarometer and shows issues that are of most concern to the everyday African across 36 countries (the survey was conducted in 2014 and 2015). The most cited issue of concern is unemployment, followed by health and education. (H/T to Carlos Lopes on Twitter)

That’s on maps for now.

(4) Naturally, we wanted to find out whether the concerns raised in number (3) are reflected in the kind of research questions that economists working on Africa are asking. And what better place to look than the Economic Development in Africa Conference held every year at Oxford University and billed as the premier conference for economists working on the continent (yes, we’ve blogged before about how troubling it is that this conference is held in Oxford). Justin Sandefur of the Center for Global Development went to the 2013 edition and conducted an analysis of the focus areas of the papers presented that year. He split his analysis based on whether the economist was African (i.e. African-based) or non-African. Sandefur found that:

African scholars [were] disproportionately interested in labor (i.e., jobs), firms (possibly jobs again), and monetary policy. Non-African scholars [were] disproportionately interested in political economy, conflict, natural resources, and (an outlier) migration. Roughly speaking, there [was] a division between jobs-focused papers by African researchers and papers by non-Africans focused on institutions.

Does this disconnect surprise anyone?

(5) One of our favourite UN bureaucrats Dr. Carlos Lopes of the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) sat down for an interview with South Africa’s The Daily Maverick to make the case for “interventionist states” in Africa. Here’s a sample:

[African] states need to get involved. The terms “developmental state” or “interventionist state” might be unpopular, but that is exactly what is required for African countries to lift themselves out of poverty, to achieve the kind of economic development required to tangibly improve the lives of hundreds of millions of African citizens.

The idea that governments could intervene in the economic affairs of their respective countries was rendered obsolete by the market fundamentalist ideas of the Washington Consensus.

(6) More on Dr. Lopes: We watched this really insightful talk on understanding Africa’s infrastructure appetite. Here are some facts from the talk that we were unaware of:

Africa as a whole has made more infrastructure investments over the last 5 years than in the 30 years prior to this

Contrary to perceptions, most of this has been financed by local resources (for example Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance Dam and Egypt’s Second Suez Canal project)

African governments can still do more from local resources by collecting more taxes and cutting down on illicit financial flows out of the continent estimated at US$50billion per annum.

(7) We read this rather puzzling sentence in Chapter 11 of the 2014 book “Zambia: Building Prosperity from Resource Wealth” (emphasis ours):

Public ownership [of companies] remains surprisingly popular in Zambia, reflecting both President Kaunda’s ‘African Socialism’ and the controversial record of the privatization program of the 1990s.

Why is any of this surprising? Something is obviously going to be unpopular if it’s controversial. Duh!

(8) Is this the return of the Zim Dollar?

(9) Lastly, why is the government of Nigeria so clumsy? They’ve misplaced another US$15 billion.

May 6, 2016

Liberia needs ‘a history that will be called history after the settlers’

In 1926, following the granting of a 99-year lease to the Firestone Tire Co. by the Liberian government, a group of Harvard scientists and physicians traveled to the West African nation to conduct biological and medical surveys. One Harvard medical student named Loring Whitman recorded the expedition as its official photographer and gathered a database of some of the earliest media available on Liberia. Whitman’s photograph and films, along with documents related to the expedition, form the source base for A Liberian Journey: History, Memory, and the Making of a Nation. Funded by the National Science Foundation, A Liberian Journey is the result of a collaboration between the Center for National Documents and Records Agency in Liberia, the Center for History and New Media at George Mason University, Indiana University Liberian Collections, and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In gathering together the records of the Harvard Expedition, this collaborative project provides “a view of Liberia shaped by the white privilege and racial attitudes of American scientists,” as well as “glimpses of the peoples, cultures, and landscapes of Monrovia and Liberia’s hinterland at a time of rapid economic, cultural, and environmental change.”

Dr. Greg Mittman, a professor of History of Science, Medical History, and Environmental Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, placed this expedition in historical perspective at the launch, pointing out that the 1926 expedition team “included some of the best minds in medical entomology, tropical medicine, botany, mammalogy, and parasitology,” including Max Theiler who, on this trip, “began his research on yellow fever, work that would eventually win him the Nobel Prize for the development of yellow fever vaccine.” In addition to the scientific achievements of the expedition, Mittman also explained that the expedition built a significant archive during their travels, “documenting medical conditions, plant and animal species, and the life and culture among the different ethnic groups of Liberia.” These important discoveries are available to all users and can be navigated through three different gateways. Users can explore the collections contained in the site through the Map, which uses LeafletJS to plot out key points referenced in the collections’ materials. Users can also browse the exhibit focused on Chief Suah Koko, a female chief and key figure in the history of Liberia. Finally, the collection can be browsed according to the item type, from photo to documents to historic films (some of the oldest available on Liberia) and stories. This collection boasts nearly 600 photographs, more than two hours of motion picture footage, oral histories, and documents related to the expedition. All of these items are easily accessible, even on mobile devices due to the choice to build the site on the Omeka platform, in order to “ensure that anyone can access the site especially in areas of Liberia with limited internet connectivity.”

And this is a project meant for Liberians, first and foremost. Attending the launch of Liberian Journeys at the Center for National Documents and Research Agency, President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf envisioned the potential of this project to make Liberian history accessible to all its citizens. “By that,” President Sirleaf explained at the launch, “it will make all Liberians to know about their true history and roles their forefathers played in the past in bringing all of their children up to this point.” Dr. Joseph Guannu, a leading historian of Liberia and one of the featured interviewees in the Stories section of the site, has long been an outspoken advocate of the need for Liberians to recapture their history. “We need a real history that will be called history after the settlers,” Guannu argues, “because a country that does not know its past or where it’s heading, is not a country.” And Liberian Journeys provides a new direction for Liberian history, gathering together important historical artifacts and making them available to anyone through the click of a button.

Users are also encouraged to interact with the site by sharing their own memories of Liberia. You can contact the site administrators with any questions via this link. As always, feel free to send me suggestions in the comments or via Twitter of sites you might like to see covered in future editions of The Digital Archive!

May 4, 2016

The business of lies

Lucifer has been hard at work on “African” social and traditional media over recent months.

Donald Trump dissing Africans. Trump threatening to arrest Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe and President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda. Mugabe calling Trump Hitler’s child. Mugabe proposing to marry Barack Obama. Mugabe dissing Kenyan “thieves”. Tanzania’s President John Magufuli banning miniskirts. Eritrea ordering men to marry two wives or face jail.

The Lord of Lies and his minions of web traffic-grubbing demons are winning, and there just isn’t enough fact-checking holy water to exorcise them from our timelines and your chat groups.

The Internet has lied to the gullible for years, and fake news sites such as SDE, Spectator and Politica of Kenya have been carrying on the tradition.

Helping these children of Lucifer is all of us; That know-all in your chat group who is always “first with the news,” yeah, the one who posts fake news about accidents, goblins and so forth. The Facebook guru who is famous for being famous on Facebook. Outrage Twitter, up at dawn scrolling the timelines looking for things to get angry about. All of us. And Lucifer.

Why do fake news sites exist?

Easy. The love of money is the root of evil, such as all this fake news. Once you click on the link, fake news sites make a few extra dollars on all those ads you see on their web pages. They don’t care if you stay on the site for a long time to read more content; this is why they work hard to create viral, single news items.

Using web tools like webuka and siteprice, you can get an indication of how much these fake websites make in ads monthly. Take, for instance, SDE Kenya, the site that gave us lies about miniskirts being banned in Kenya and the Eritrea thing. In the days after the Eritrea hoax story, the site had an average monthly ad revenue of between $6,000 (via siteprice) and $18,700 (on webuka). Not dead accurate, distorted by fluctuations in views, which went up to 102,000 daily views. But you get the picture.

The statistics show people stay on SDE an average 5 minutes. They don’t need you to stay long. Just long enough to get you reading that one viral fake story and get those ads.

Lucifer’s work is even more profitable elsewhere. Joseph Finkelstein, an SEO expert quoted in an article by the New Republic, said of one of America’s most well-known fake news sites, The Daily Currant:

But at most, over the few years they’ve existed, The Currant may have made as much as $500,000 in revenue—split between two people who are hardly doing any work.

You see the Devil and his work?

Why do they succeed?

Well, no kinder way to say this; they succeed mostly because we are stupid, prejudiced and ignorant. We don’t check facts, or question the source because we’ve come to believe that, as I’ve said here before, everything is true if it’s on the Internet.

We can forgive ordinary web users for having meme fun with fake news. However, it all gets worrying when mainstream media–many with large audiences–also join in, allowing themselves to be duped into providing conduits for fake news.

Check the source. Who said it? Where? Who else is reporting it? These are steps we could take to verify. But then Lucifer whispers “where’s the fun in that,” and we press the share/retweet button, spreading lies.

Mainstream news sites that do that also profit from high traffic to their sites, even if it means sacrificing some credibility.

Why are media being duped?

Fake news websites play on our own prejudices and ignorance. They bank on us, and major news media, wanting for certain news to be true. Some of the news feeds our existing prejudices; about Africa, and even our own countries.

Josh Voorhees, of Slate, in an article he wrote when Drudge fell for a story on The Daily Currant, said fake sites “rely on (mainstream media) wanting to believe a particular story is true.”

And “wanting a story to be true” is the case with all the stories about President Mugabe. When the US legalized gay marriage in 2015, AWD News, a fake news site, wrote that Mugabe had reacted by “proposing marriage to [Barack] Obama.”

In no time, the article had been shared widely on social media. South Africa’s News24 took it as fact and published it. The BBC published the article as fact, linking to the AWD story with no hesitation. The UK’s Daily Mirror also did the same. In December 2015, BBC Africa reported the “I want to marry Obama” quote as one of its “top 2015 quotes.”

Mugabe, we were told, had said all this “in his weekly radio address.” Even Zimbos, who know, or at least should know, that there’s no such thing as a “Mugabe weekly radio address,” believed it.

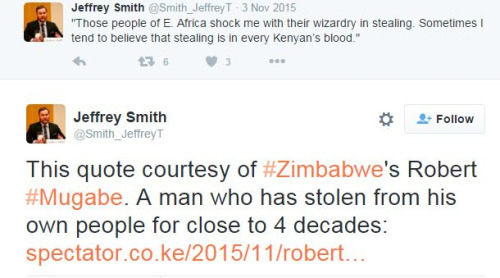

In 2015, Spectator, a fake Kenyan site, wrote a fake story claiming Mugabe had called Kenyans thieves. The story made it into an otherwise great story on Kenyan corruption by the NY Times. After some criticism, to the paper’s credit, the fake quote was removed.

Yet, an example of “wanting fake news to be true” came from Jeffrey Smith, of the US rights group Kennedy Institute. He shared the Kenya story on Twitter; a corrupt man like Bob had no right to be lecturing on graft, he shouted. When told it was all fake, he replied: “Wouldn’t be the first time he’s made such comments.” The “Obama story” was fake too, but, you see, this sounded like something Bob would say.

Which, somehow, makes it all OK. It appears a story doesn’t actually have to be factual, but just believable.

It’s true. I read it on the BBC. It was in the papers too.

One of the major reasons fake news succeeds is gullible “mainstream media” sharing it online. Desperate for content and engagement, and eyeballs to their own websites and paper sales, fake news is pushed on audiences without so much as a basic fact check.

This is how we end up with purportedly reputable news sources such as the BBC reporting it as fact that Mugabe wants to marry Obama.

You get the feeling that, many times, major media do not put stories from Zim or Africa in general through the same credibility tests as they do stories from elsewhere. This is something I’ve blogged before.

Will this ever end?

It won’t. There’ll always be people who lie and people who believe lies. So, no.

Facebook has tried to stop the sharing of fake news on its walls, but it’s all pointless. Because, face it, if people are still crazy enough to believe, and share, fake news, there will always be people crazy enough to produce fake news.

Lies are more fun than facts. Lies are proving to be more profitable for websites. Facts are boring anyway. Even here in Zimbabwe where facts can be more hilarious than fiction.

Facts have never been popular on social media – and that, in fact is, one reason why social media is popular.

*This is an edited version of a post that first appeared on Ranga Mberi’s Tumblr blog.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers