Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 303

June 21, 2016

Pornography and Photography

The Italian photojournalist Michele Siblioni documents nightlife in Kampala, Uganda mostly in the neighborhoods of Kansanga and Bunga: Strip clubs, bars and sex workers are his main subjects.

Siblioni’s website features a video in which one of the women he photographed shows him a tattoo with the words “fuck it sexy” written across her thigh alongside a penis and testicles. When Siblioni asks why she got the tattoo, she says she likes penises and sex. It is this type of back and forth between Siblioni and his models, that draws your attention to his exoticizing of black female sexuality.

The project is now a book, Fuck It. The centerpiece of the book is a cigarette-smoking black women. The effect: the real subject becomes the lens of the photographer himself.

There’s the image of a black woman with an ornamented ring as well as earrings. She is facing Siblioni’s camera at an angle, taking in a long drag of her cigarette. The photograph shows her fake nails, and we do not see her eyes or forehead, which is covered by a blurry finger. The image of women smoking cigarettes is one of the older tropes of sexually provocative imagery. The cigarette is a phallic symbol, and the smoke colors the image with an aura of lust and intoxication.

In another image a black woman is caught midway through her walk on the stage wearing a sequined bra and sequined underwear. Her pose is strong, and her walk is resolute, even as her eyes face the floor. The photograph shows a glimpse of the casual strip shows in Kampala. And there’s the photograph of the nude black woman wrapped in an animal print blanket. Her chest is bare and her vagina shows. She is posing quite assuredly for the camera.

The photographer’s interest lies in the black woman’s physique, and always in her on-display sexuality, reminding one of tropes observable in other African photography surveys where the images have been taken through outside lenses. How the women respond to Siblioni’s camera is key. The camera functions as an erotic tool in the exchange between Siblioni and his black women. The camera attracts and provokes sexually-charged poses. There is yet another black woman sitting on a straight-backed chair in reverse. She looks into the camera, with intoxicated eyes. And, guess what? She is smoking a cigarette.

Other photographs in Fuck It show an environment of rudimentary housing, ghettos, and homeless people. A photograph of a pile of broken egg shells; another of the jacketed security guard with a bow and arrow shows us the surprising dynamics that shape this environment. Siblioni’s vision resolves into a montage of urban decadence and provocative black female sexuality.

The chaotic merges with the pornographic, black women are given the same amount of attention as homeless people, night watchmen and seedy bar scenes. The quixotic way in which Siblioni moves from party to street to egg shells to night taxi conductor to charcoal sacks to swimming pool to boda bike riders, and to heaps of rubbish is both cinematic in its ambition, and recalls the Whitmanesque imperative described by Susan Sontag, “Treat all moments as of equal consequence.” We end up seeing Fuck It as part of the vertigo of a wild party; a half-consciousness of scenes we barely recall afterwards. And yet there is no real subject outside of the photographer himself. The place of the photographer, beside the black females, and security guards and the heaps of rubbish, is that of a benefactor. Siblioni’s naivety in his photographing black female sex workers in Kampala is the obfuscation of being a white male primarily interested in photographing black female bodies.

Danish photographer Jacob Holdt arrived in the US in the 1960s and spent five years hitchhiking across the country. Looking at American Pictures, the photobook Holdt produced, one can draw a few parallels with Siblioni’s book Fuck it. Both are foreign white male photographers spending a few years in another country, where they focus primarily on black people. Both are drawn to depictions of black sexuality, and to the aesthetic of handheld flash photography and grainy film. Both can be viewed in the context of porno miseria – depicting an underclass in a degrading environment.

There’s one Holdt photograph of a black woman in a bathtub staring straight at the camera. Her eyes have a particular kind of sadness. She is completely naked. She’s wearing a choker around her neck. I’m drawn to this image because of Holdt’s depiction of black female sexuality. The photograph is beautiful, and the subject is the woman herself, and her thoughts, her sense of vulnerability.

Holdt’s technique in which black women shared their open nudity with him, and for his camera, has more to do with his political mission in the US. Holdt was interested in the lives of the underclass, and sought – though facetiously – to integrate fully into a life of limited or non-existent wealth. He made this photographic series in order to demonstrate for his native Denmark the devastating effects of those living in a country without welfare, and the country’s industrial capitalism.

Holdt’s images of pornography are defined by his political and moral ambitions. I find the photograph of the nude girl in the tub facing the camera really fascinating because of the allusion again to purity and innocence, but similarly to the presence of the photographer and his moral position. Holdt’s pornography is not made for his own sexual gratification, but rather to expose the intimate lives of black people. His photographic journey is an experiment of living with the underclass. His photography is based on a misguided faith that he could become integrated in the underclass. Holdt also assumes a position of power in his storytelling.

Michele Siblioni, on the other hand, experiences a bar club scene that is tailored to serve an expatriate clientele. The explosion of foreign aid to Africa countries in recent decades has seen the rise of an expatriate population, and of course, of bars, clubs, and sex workers. The idea of Siblioni entering the bar scene in Kampala is also about the economic position of aid workers and the white male expatriates. Not only is Siblioni using his photography to document his own adventures, but the environment he does this within has been constructed to satisfy the white male desire for black women. In contrast, Holdt’s work becomes very intimate, and shows a genuine interest in getting to know his subjects. Holdt is interested in the intensely personal.

I go back to the relationship between Holdt’s pornography and Siblioni’s pornography; Holdt’s pornography is rooted in glimpsing the intimacy of black people as further evidence of exposing the life the underclass. Siblioni’s pornographic imagery is rooted in the specific desire of the photographer to see and to experience exotic sexuality, while prying on the privacy of black women.

In both instances, the photographer is exploiting his subject, though in Siblioni’s case the purpose of shooting the subject is for his own pleasure, and hence the work can be interpreted as characterizing the white male gaze. It seems that the ultimate goal of Fuck It is to achieve the satisfaction of the white male ego, via the camera lens, and through exotic depictions of black women.

June 16, 2016

What African economies need: good, old fashioned industrial policy

Uitenhage vehicle factory, Eastern Cape province. Image via Volkswagen South Africa.

Uitenhage vehicle factory, Eastern Cape province. Image via Volkswagen South Africa.In terms of economic development, most African countries are operating below the least developed country income threshold of $1,035 per person. While developing countries in East Asia, most importantly China, have been lifting millions of people out of poverty at break-neck speed, Africa’s poverty rate has barely budged. In 2011, 69.5% of people in sub-Saharan Africa were living on less than $2 a day, only three percentage points lower than in 1981. As a result, Africa’s share of world poverty is 40% higher today than it was at the turn of the millennium.

The key to China’s rapid growth, and most other countries that have experienced the transition from low to high income, has been industrial policy – targeted interventions by the state to push economies towards the global technological frontier, especially in the manufacturing sector, while relinquishing dependence on agriculture and natural resources.

There are virtually no internationally competitive manufacturing firms in Africa, so the continent desperately needs industrial policy. The report summarized in this post is the result of work I did with Dr Ha-Joon Chang and Dr Muhammad Irfan, for the UN Economic Commission for Africa. Titled Transformative Industrial Policy for Africa. It aims to serve as a guiding tool for using industrial policy in Africa.

Industrial policy as a development theory is nothing new. One of its seminal advocates was Alexander Hamilton, the first treasury secretary of the United States. The core of Hamilton’s argument was that backward economies – which the US was in the late 18th century – needed to protect and nurture their industries in infancy through various policy measures until they could attain international competitiveness. Heeding the advice of Hamilton, successive US politicians made the country a bastion of protectionism: it had the world’s highest average tariff rates on imported manufacturers throughout the 19th century. It is ironic, then, that financial institutions much influenced by the United States – the World Bank and the IMF – thwarted any attempts by African countries to use industrial policy in the 1980s and 1990s. During those decades, neoliberalism swept the world – an ideology that saw the state fit for little more than adhering to the free market. In most of Africa, the state was consequently scaled down. But this also ended up diminishing any hope for industry to flourish.

States can surely fail, but industrialization has never happened without an active state, with its slew of tools and incentives aimed at making firms competitive in advanced sectors of the economy. The report re-emphasizes the significance of state intervention for the purpose of industrialization. In doing so we make two key policy points:

One is the importance of history. Successful catch-up economies have rarely (if ever) formulated successful industrial policy plans out of thin air. Although every country has its own political, economic and social nuances, learning from history is important. That’s why the report dedicates a large chapter to successful cases of industrial policy, from 19th century United States to 21st century Vietnam. The report deliberately provides a wide variety of cases, so that policy makers can pick and choose from this “treasure box” of tools.

Recurring tools include: tariffs and subsidies to nurture industries in their early stages, often handed out to firms on the condition of meeting performance requirements; the provision of long-term subsidized credit to industry through state-owned development banks; and the establishment of state-owned enterprises to take on risk that the private sector is hesitant to underwrite.

Take the example of South Korea between 1960 and 1990. The country’s risky entry into steel was made by the state setting up POSCO, which today is one of the world’s largest steel companies. Steel and other industries received long-term financing from the Korea Development Bank, which in 1957 accounted for 45% of total bank lending to all industries in the country. But this type of financing and other forms of subsidies usually came on the condition of meeting performance standards, like reaching a certain amount of exports in a five-year time frame.

Second, policymakers should take the changing global economic environment into consideration, but should do so with caution. Since the mid-1990s, production networks have become increasingly global and fragmented. A popular argument, especially advocated by international organizations, is that developing countries shouldn’t build entire industries to develop, but rather join a segment of a global value chain, often controlled by big transnational corporations. For example, instead of trying to build their own brand of phones, they should just assemble iPhones for Apple.

However, the report shows that since the 1990s, many countries have become trapped in a low-growth path through this type of segmented specialization. Examples in Central America, such as the Dominican Republic and Mexico, show how countries can be stuck with low-value tasks, be it assembly of electronics products or the sewing of jeans, without creating any linkages to the domestic economy. On this point, the history of economic development is clear: in order to prosper, developing countries need to take ownership of their own industries, not simply be production puppets of transnational corporations based in the West.

Ultimately, industrial policy should be context specific, so the report doesn’t provide a golden formula for success. Ethnically and culturally, the 54 countries in Africa are arguably more distinct from each other than countries in Europe.

But economically, they’re strikingly similar. No African country has structurally transformed its economy, making the move from dependence on agriculture and natural resources to manufacturing. That’s why industrial policy needs to be put on the forefront of the development agenda on the continent.

African economies and the lack of a targeted industrial policy

Uitenhage vehicle factory, Eastern Cape province. Image via Volkswagen South Africa.

Uitenhage vehicle factory, Eastern Cape province. Image via Volkswagen South Africa.In terms of economic development, most African countries are operating below the least developed country income threshold of $1,035 per person. While developing countries in East Asia, most importantly China, have been lifting millions of people out of poverty at break-neck speed, Africa’s poverty rate has barely budged. In 2011, 69.5% of people in sub-Saharan Africa were living on less than $2 a day, only three percentage points lower than in 1981. As a result, Africa’s share of world poverty is 40% higher today than it was at the turn of the millennium.

The key to China’s rapid growth, and most other countries that have experienced the transition from low to high income, has been industrial policy – targeted interventions by the state to push economies towards the global technological frontier, especially in the manufacturing sector, while relinquishing dependence on agriculture and natural resources.

There are virtually no internationally competitive manufacturing firms in Africa, so the continent desperately needs industrial policy. The report summarized in this post is the result of work I did with Dr Ha-Joon Chang and Dr Muhammad Irfan, for the UN Economic Commission for Africa. Titled Transformative Industrial Policy for Africa. It aims to serve as a guiding tool for using industrial policy in Africa.

Industrial policy as a development theory is nothing new. One of its seminal advocates was Alexander Hamilton, the first treasury secretary of the United States. The core of Hamilton’s argument was that backward economies – which the US was in the late 18th century – needed to protect and nurture their industries in infancy through various policy measures until they could attain international competitiveness. Heeding the advice of Hamilton, successive US politicians made the country a bastion of protectionism: it had the world’s highest average tariff rates on imported manufacturers throughout the 19th century. It is ironic, then, that financial institutions much influenced by the United States – the World Bank and the IMF – thwarted any attempts by African countries to use industrial policy in the 1980s and 1990s. During those decades, neoliberalism swept the world – an ideology that saw the state fit for little more than adhering to the free market. In most of Africa, the state was consequently scaled down. But this also ended up diminishing any hope for industry to flourish.

States can surely fail, but industrialization has never happened without an active state, with its slew of tools and incentives aimed at making firms competitive in advanced sectors of the economy. The report re-emphasizes the significance of state intervention for the purpose of industrialization. In doing so we make two key policy points:

One is the importance of history. Successful catch-up economies have rarely (if ever) formulated successful industrial policy plans out of thin air. Although every country has its own political, economic and social nuances, learning from history is important. That’s why the report dedicates a large chapter to successful cases of industrial policy, from 19th century United States to 21st century Vietnam. The report deliberately provides a wide variety of cases, so that policy makers can pick and choose from this “treasure box” of tools.

Recurring tools include: tariffs and subsidies to nurture industries in their early stages, often handed out to firms on the condition of meeting performance requirements; the provision of long-term subsidized credit to industry through state-owned development banks; and the establishment of state-owned enterprises to take on risk that the private sector is hesitant to underwrite.

Take the example of South Korea between 1960 and 1990. The country’s risky entry into steel was made by the state setting up POSCO, which today is one of the world’s largest steel companies. Steel and other industries received long-term financing from the Korea Development Bank, which in 1957 accounted for 45% of total bank lending to all industries in the country. But this type of financing and other forms of subsidies usually came on the condition of meeting performance standards, like reaching a certain amount of exports in a five-year time frame.

Second, policymakers should take the changing global economic environment into consideration, but should do so with caution. Since the mid-1990s, production networks have become increasingly global and fragmented. A popular argument, especially advocated by international organizations, is that developing countries shouldn’t build entire industries to develop, but rather join a segment of a global value chain, often controlled by big transnational corporations. For example, instead of trying to build their own brand of phones, they should just assemble iPhones for Apple.

However, the report shows that since the 1990s, many countries have become trapped in a low-growth path through this type of segmented specialization. Examples in Central America, such as the Dominican Republic and Mexico, show how countries can be stuck with low-value tasks, be it assembly of electronics products or the sewing of jeans, without creating any linkages to the domestic economy. On this point, the history of economic development is clear: in order to prosper, developing countries need to take ownership of their own industries, not simply be production puppets of transnational corporations based in the West.

Ultimately, industrial policy should be context specific, so the report doesn’t provide a golden formula for success. Ethnically and culturally, the 54 countries in Africa are arguably more distinct from each other than countries in Europe.

But economically, they’re strikingly similar. No African country has structurally transformed its economy, making the move from dependence on agriculture and natural resources to manufacturing. That’s why industrial policy needs to be put on the forefront of the development agenda on the continent.

June 14, 2016

The Edge of Wrong

Edge of Wrong Festival via Facebook. Image Credit: Niklas Zimmer

Edge of Wrong Festival via Facebook. Image Credit: Niklas Zimmer“The closer to the edge you are, the more you see of the beautiful valley.” These words, roughly, were attributed to South African composer, Carlos Mombelli, and they inspired the name for The Edge of Wrong music festival (EoW), a South African-Norwegian collaboration for uncompromising, improvised noisemaking.

The 10th edition of this festival took place from the 21-24 April in and around Cape Town, and included a film screening, microphone-building workshop, music hacker lab and two concert nights at the Atlantic House in Maitland, and Moholo Live House in Khayelitsha.

“Experimental music” is, as the term suggest, not so easily categorized, and the event’s line-up mirrored this. From melodious violin improvisation to room-shaking, ear-drum-testing electronic noise and strange pitches, EoW’s ethos was curated, but not elitist. There was a pay-what-you-can cover charge, a make-shift bar and intimate setting, so it was not set up to be a money-maker. What’s more, the accompanying workshops, aimed at making the technology accessible, created a strong community spirit. Using materials that cost less than R20 each, for instance, Norwegian musician and sound artist Arnfinn Killingtveit showed attendees in Khayelitsha how to build a microphone.

There was also a focus on unconventional electronic sounds that, if you weren’t used to hearing them, might sound like random tinkering or unpleasant noise – an excuse to make music badly under the guise of experimenting, some might say. I was interested in understanding these sounds.

I sat down with founders, Morten Minothi Kristiansen (Norway) and Righard Kapp (SA), to find out. Morten had spent some years studying jazz at the University of Cape Town and, although there was a more established scene for experimental music in Norway, he happened upon like-minded musicians here. Righard was one. Together they put on the first, “quite badly organized” festival at the Labia Cinema in 2006. They went on to build a community of experimental musicians in South Africa.

Righard explains that you don’t listen to experimental music the same way you would listen to a catchy song; if this is your expectation, then you might be quite turned off. He believes it is music that not only accepts failure but invites them. It’s “a different kind of theatre,” stripped of embellishment, rooted in performance and very self-aware.

It’s a visceral, immediate thing… that let’s one feel quite empowered… removed from these machinations that keep our lives in bubbles. The best things I have facilitated, I didn’t feel, ‘Wow I did that.’ It was like, ‘Wow it happened.’

Just like a relationship counsellor would tell you to “embrace your mistakes,” Morten believes that mistakes can lead to great music.

We have scientists who get paid a shit load of money to cure cancer… They do experiments… because they’re on their way to something. It’s a bit like that with this music. Of course it’s not about playing badly either. There are ways to define quality in experimental music, and there can be a lot of structure too. A good improviser is somebody who knows his shit, who knows his instrument.

Arnfinn Killingtveit’s performance at the Atlantic House exemplified this expertise and use of structure. He performed, solo, a generative algorithmic composition that would have required about 20 hands if he had to play it conventionally. Through tapping on a table and connecting the motion to timers, calculations were generated according to the interval between each tap. Every time he hit the table, some numbers would stay the same and some would change to create a complex score of physical sounds computed through synth models. By removing human intervention, at least to a certain extent, the composer himself couldn’t be sure of the outcome, producing an otherworldly arrangement.

Exploratory, DIY approaches like the Edge of Wrong festival add value; especially in places where radio airtime has until very recently been monopolized by the American pop genre. Droning noise crescendos are not for everyone, but a free, open space that allows for play and experimentation is. In the same way that we acquire a taste for whiskey or become accustomed to the burn of chili, perhaps we can discover something amazing by sitting and listening to the noise.

June 13, 2016

A Ugandan Spring

On a lunch break with a group of friends last month, our conversation was suddenly interrupted by the roar of a group of fighter jets flying over the hills of Kampala. The seemingly new Russia-made Sukhoi Su 30-MK2 war jets twisted and turned in the air, leaving the residents of Kampala musing at this unusual sight. That very afternoon, the Minister of Information, Jim Muhwezi, addressed a rushed press conference, announcing a government ban on any further media coverage of the newly-announced opposition-led “defiance” campaign. The police chief nodded. The message was clear.

The jets have since become a common sight. Meanwhile, since February, columns of between eight to 10 soldiers can often be seen strolling the streets of Kampala any time of the day. The now all-too-common police vehicles are strategically positioned around the city, well equipped with teargas, policemen and sometimes plain-clothed operatives. At the headquarters of the key opposition party, Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), garrisons of armed men daily stand still, their mean-looking faces sending a warning message to any potential protestor. Homes of key opposition politicians have routinely been placed under siege, and social media has been frequently switched off in recent weeks.

This has been the regime’s grim response to the defiance campaign, which calls for civil disobedience until the government cedes to an independent audit of the election results released in February, which gave the 72 year-old president Yoweri Museveni and his National Resistance Movement (NRM) party – in power since 1986 – a controversial victory, with 60% of the vote, and a fifth term in office.

So far, the regime’s response to the planned protests has revealed its deep-seated fears of a possible “Ugandan spring.” When, in 2011, demonstrations broke out in nearby Egypt, the media – especially social media – proved an indispensable tool to the thousands of youthful protestors in Tahrir Square. The protests spread like a wildfire. Mubarak fell. Soon after, inspired by the Tahrir protests, Kampala witnessed the first serious protest against NRM rule, constituted in the Walk-to-Work protests. They were eventually crushed, largely because the protestors framed their demands purely in economic terms, focusing merely on the escalating prices of oil and foodstuffs. Nevertheless, the protests left an indelible mark on Ugandans’ political psyche.

The recent defiance campaign in Kampala, coming five years later, is a reincarnation of the Walk-to-Work protests, albeit bolder in its objectives. Unlike its predecessor, the defiance campaign is unapologetically political in its demands, challenging the very legitimacy of the Museveni regime, and thus approaching the Egyptian revolution, at least in purpose. That the regime has in no way missed the real message behind the demand for a special audit of election results is evident in the harsher response the campaign has so far received. This, however, has made the future of the planned protests very uncertain, and many Ugandans have been hesitant to identify with them for fear of retribution.

The regime’s message has been clear: the government will take no chances. Any protest movement will be nipped in the bud before it crystallizes. The strategy has paid off – at least for now. The streets have been largely clear. Yet, the recent narrowing of political space, far from containing popular dissent, has made it even more likely that any popular demands in future will have to find expression outside the formal mechanisms of the political system. With faith in the electoral system significantly eroded, popular protests outlawed and the media banned from covering opposition activities, it might only be a matter of time before popular energy erupts in a new movement, one perhaps even more dramatic than that in Tahrir. After all, the North African protests were driven not by the media per se, as NRM logic has it, but by the politics of repression.

The future of the current defiance campaign might be bleak, but the radical nature of its demands, compared to its predecessor, calls for deeper reflection on an important contemporary lesson: the more political space shrinks, the more likely it is that popular discontent will seek for alternative channels through which to articulate itself, sometimes even at the risk of violence.

June 10, 2016

Weekend Music Break No.97

Here’s another Music Break to soundtrack your weekend! This round up is the “other countries” edition with a selection of tunes starting out in Latin America from Cuba to Brazil, and ending up around the rest of the African diaspora. Check it all out via the Youtube playlist below!

Music Break No.97

1) We kick it off with what I’ve been told is Cuba’s biggest tune of 2016, “Hasta que seque el Malecón.” 2) Then we go to Puerto Rico with Ifé and their Orisha-tronica sound (h/t Pablo Medina Uribe). 3) Next up, inspired by the movie “Manos Sucias,” and one of the most heartwarming scenes about music I’ve ever seen recorded on film, Grupo Niche and their classic salsa tune “Buenaventura y Camey.” 4) Then we move from Colombia’s Buenaventura, to the Chocó and rap group ChocQuibTown’s “Nuqui (Te Quiero Para Mi).” 5) I love the idea from a recent article in Globo that Funk is more Baiano then ever — MC Menor da VG runs with that idea and visits Salvador da Bahia during carnival, at the same time showing how o cavaquinho ta conquistando o Funk. 6) UKs Afrobeats don, Fuse ODG, turns in a new video for his tune “Only.” 7) Brussels residents Badi and Boddhi Satva team up on an Afro-Hip-House anthem on “Integration.” 8) South Africans scattered about the world Mo Laudi, Gazelle, and DJ InviZAble unite in the Pantzula dancer featuring “Speak Up.” 9) South African originated Norweigian Nosizwe teams up with Georgia Anne Muldrow on “The Beat.” 10) And finally, Nigerian-American Tunji Ige takes it from Philly to LA with both a West Coast visual and sonic vibe on “War.”

Have a happy weekend, and sports fans, enjoy the many tournaments going on around the world!

The Uber driver and Muhammad Ali

The Uber driver has never heard of Muhammad Ali. I am flabbergasted.

I always sit in the front, even when I am alone in an Uber. It makes me feel more egalitarian. Also in Johannesburg there is the taxi drama and it would nice not to be entangled in violent fights between a dying industry and one that is just being born. Anyway, when I am up front I feel obliged to talk and so a few minutes into our ride, as I am scrolling through my phone looking at Facebook, I say to him, “It’s so sad, Muhammad Ali has passed on,” in a conversational tone.

But he seems confused and asks me who that is. I am equally confused and so I say, “Muhammad Ali. You don’t know him?”

The Uber driver is older than most. He might be around sixty and I wonder why is he driving and where he comes from but his name is Owen and that tells me nothing. He is not from Zimbabwe. This man’s Zulu is not Ndebele. But then I think to myself that if he were from Zimbabwe he would have heard of Muhammad Ali.

Surely – no matter where he is from, he should know who Muhammad Ali is. What kind of person doesn’t know Ali?

I persist. This issue is now becoming more important to me than it ought to. I show him a picture on my phone.

“Him.” I say.

He shakes his great head and there is not a hint of recognition. I tell myself that it’s because he is only half-looking. He is trying to keep his eyes on the road instead of looking at a picture of a man he’s never heard of.

“No, I don’t know that guy.”

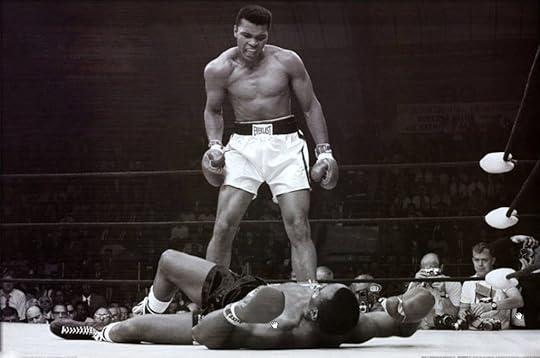

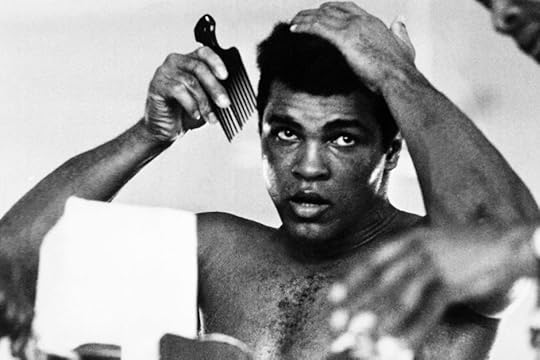

I flick through my phone looking for a younger picture of Ali. I find one of the boxer in his prime. Ali is standing over an opponent looking triumphant. I am distracted for a moment because I have just seen from the caption underneath the picture that the Rumble in the Jungle was in October, 1974. I am surprised. I remember everything about that night. I remember my dad and his friends drinking whiskey in the living room. I remember the cloud of smoke curling under the lamplight. I remember the flicker of the TV screen playing on their faces. I even remember his skin was caramel, even through the black and white of the TV. I remember the crowds screaming and screaming. Ali Bomaye! Ali Bomaye!

But these are not real memories. They are just pieces of nostalgia and other people’s recollections woven into my heart. They have been inserted by the cultural milieu in which I grew up – a product of the privilege of growing up with a television in the house and a father who was mad about boxing. I was barely born when that fight took place. I can’t believe that all of these years I have been carrying around this idea that on the night of that match I was a child curled on father’s lap when in reality, I was only a few months old, asleep in a crib next to my mother, blissfully unaware.

Anyway, this is all a distraction. The matter at hand is the driver.

He doesn’t recognize the younger version of Ali either.

“Anim’azi,” he says. “Is he from South Africa?”

“No, from America.” I tell him, still incredulous but trying not to seem so.

Suddenly I want to cry. I cant ask, “Like where have you been dude?” because I know the answer. He has been here. Or perhaps, put differently, he has never been anywhere and this is not his fault. He has no idea that Ali was the greatest and he doesn’t know anything about Zaire (now Congo again) or Mobutu Sese Seko and I am beginning to understand the full import of this. He may have never heard of the Vietcong and maybe he doesn’t know about the Black Panthers either.

None of this is his fault of course. Still it is remarkable and it troubles me. He is driving a Toyota Corolla Uber and using GPS and he has never heard of Muhammad Ali.

Everyone on my Facebook timeline knows who Muhammad Ali is, but then again everyone on my timeline has been somewhere. Many of them have been pretty much everywhere. Everywhere that counts at least and it is obvious that this Uber driver is from nowhere; at least nowhere that counts. Although he has the app, he is not a citizen of Online. That country, it seems, is a faraway place.

Maybe, all of these years while the Uber driver was alive but walking around this Earth not knowing who Ali was, he has had other things to worry about. Maybe his eyes were fixed too firmly on keeping one foot in front of the other for him to be looking for Muhammad Ali on the horizon.

I – on the other hand – have been to America and back. I read the New York Times. I am part of the New World and I travel to Online frequently. I am plugged in and I am beginning to understand that even though I thought Uber was a signifier of citizenship, I was wrong and so I say to him, quietly and without a hint of the incredulity that I am feeling, “Oh, okay. Well, he’s famous. Anyway, ushonile izolo.”

“Awu, shame.” He says.

***

You assume – because you are both plugged in and you both have smartphones – that you and the Uber driver are the same. You think that somehow you are participating equally in the technological revolution and so you erase your class position and his and in your mind you are sort of like a single being. You turn him into your friend because he has your cell number and you have his and this is a slippery place to be and it is dangerous too because to him your chumminess is also accompanied by your willingness to pay R6 a kilometer and that must feel like a knife in the chest.

Every time you sit in an Uber and ask, “How’s business?” you want him to say, ‘It’s busy, my sister!” and when he doesn’t disappoint you; when he tells you a story about the peak times and how long he has been driving, then you are relieved and soon you begin to believe that Uber is democracy because his car is clean and he is chatty and ‘smartly’ dressed and you can call him by his first name and he can do the same, because…um, the app.

You begin to think that you are just the same and that Uber is justice and economic freedom because he does not smell like mahewu and firewood and there is not even a whiff of his sweat when you get in even though he sits in this car all day long.

You rate him and he rates you and so you begin to believe you are both the same. You forget that you are in the car because you have a credit card and he is driving the car because he probably does not have a credit card. You even forget that he is talking to you and being nice because he needs the money and at the end of the ride you will have to rate him.

You forget that Uber is a brand and using it does not transport you both to Silicon Valley because somehow somewhere along the way Uber came to mean Google and Twitter and all of these things that are very cool and very modern and you forgot in all your coolness and Uber-ing that you are paying a laborer for a service.

It is easy to forget the transactional real-world issues that are at stake when you never have to fumble and touch someone’s hands over rands and cents at the end of a cab ride. You can act as though there was never a transaction at all – as if you just had a momentary casual friendship.

Uber is a fantasy that lets you pretend that your fingertip is not more powerful than your driver’s entire body. You can pretend that he isn’t steering you through the city and across its highways; driving so that you can have your hands free so that you can keep writing and stay connected and get ahead while he drives the same routes over and over again – in a loop that may never take him forward. It is easy to pretend that you aren’t engaging in digital exploitation when it’s all on your phone and on your card and in the ether.

But when your driver has never heard of Muhammad Ali suddenly you realize that you are not his friend and you and he occupy different worlds and you wonder whether you should count yourself lucky that he does not yet see you as his enemy.

The G.O.A.T.

The emotions run high when I think about Muhammad Ali and what he meant to me, to us, as children, growing up during apartheid in South Africa. There were days when it felt like the violence and oppression would never end, that we would not win, that the system was too big, too strong.

We were kids. White supremacy was all around us, on the streets, in Casspirs and Buffels, dressed in army and police uniforms spraying teargas and rubber bullets at us as we walked to school. Nelson Mandela was in prison and his image was banned. We were black and we were being beaten and the system was against us – as it was against millions of others around the world.

During those years, Muhammad Ali was part of what gave us hope, part of what shaped and inspired a psyche of defiance and resistance. As a child schooled in black consciousness and from a Muslim home, here was this black man, a Muslim, with whom I shared a first name, Muhammad, standing up to Empire. Years earlier he had told the most powerful racist establishment on the planet that he would not go and fight their war. And he did that in a way and at a time when it was unimaginable:

Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on Brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights? No I’m not going 10,000 miles from home to help murder and burn another poor nation simply to continue the domination of white slave masters of the darker people the world over. This is the day when such evils must come to an end. I have been warned that to take such a stand would cost me millions of dollars. But I have said it once and I will say it again. The real enemy of my people is here. I will not disgrace my religion, my people or myself by becoming a tool to enslave those who are fighting for their own justice, freedom and equality. If I thought the war was going to bring freedom and equality to 22 million of my people they wouldn’t have to draft me, I’d join tomorrow. I have nothing to lose by standing up for my beliefs. So I’ll go to jail, so what? We’ve been in jail for 400 years.

There can perhaps be no modern equivalent of that statement, given what the world was like then. Ali’s audacity, courage, defiance and strength became part of our collective consciousness. I was too young to have witnessed his feats in the ring but to me his iconic status was about the fight outside the ring. From the witty verbal jabs to the powerful political statements, Ali used his status to challenge, to provoke, to speak truth to power. And he did that with a mix of charm and humor as well as anger and strength. When I think back to those days growing up, he was a superhero. He inspired, gave us courage, made us laugh, gave us permission to dream and provided hope during some very dark times. In that sense, Ali was indeed the greatest. A champion of the world and a champion of the streets.

The Nsibidi Institute Memory Project

In the previous installment of the Digital Archive, we spotlighted Liberian Journeys, a digital nationalist archiving project, collecting key artifacts from the country’s complicated history and combining those with reflections from contemporary Liberians to convey the importance of preserving the nation’s history. Other projects featured here on the Digital Archive, like Nigerian Nostalgia, show the potential for more contemporary histories to be preserved digitally. This week’s featured project, the Nsibidi Institute Memory Project, is yet another endeavor attempting to use digital forums to preserve memories of Nigeria, in addition to promoting the importance of capturing these histories before they disappear.

The Nsibidi Institute, based in Lagos, Nigeria, is dedicated to preserving Nigerian heritage through “homegrown knowledge creation.” These innovative materials are intended to be used to “foster a better understanding of Nigeria — its history, people, knowledge systems and possible futures.” In pursuit of these goals, the Institute works in numerous capacities, using their organization as a platform for rethinking space (as they did with their Open Lagos project and Makoko-Iwaya Waterfront Economic Opportunities initiative), Afro-futurism (read more about Lagos 2060 here), and the communication of culture through various mediums (for instance, check out the Nsibidi Film Hub). The Institute also focuses on the preservation of memory. Initially, their work on memory was funneled through the Between Memory & Modernity project, but has expanded into the Nsibidi Institute Memory Project, launched in 2015.

The Nsibidi Memory Project

The Nsibidi Institute Memory Project’s main goal is to “archive Nigerian history through the people’s voices.” Focused on creating dynamic interactions through audiovisual memory preservation, the project hopes to contribute to broader understandings of “the dynamic between our relative histories, as well as forms of memory and identity within Nigerian society.” The results of this initiative have produced multiple YouTube videos, including montages of responses to evocative questions to one-on-one interviews. In the interviews that have been made available on the Institute’s YouTube channel thus far, the topics of conversation have ranged from the personal (favorite television shows, first jobs, choice of hairstyles, bride price) to the political/historical (the effects of the civil war on their families). Check out a montage of the first year of the project below.

The Memory Project Nigeria: The Journey so Far

Follow the Nsibidi Institute on Facebook and Twitter. Users can find more information about submitting their own videos here. As always, feel free to send me suggestions via Twitter (or use the hashtag #DigitalArchive) of sites you might like to see covered in future editions of The Digital Archive!

*This post is No. 25 in our Digital Archive series covering African archives on the web.

June 9, 2016

In Africa, there should be djembe drums

For the last three months, we have been working on the sound design of my first feature-length documentary, Taking Stock, a film about my father and our third-generation family business in Benoni, a city to the east of Johannesburg. I brought a crew of close friends I had met at film school in the USA to spend a month talking with my father about work, legacy, generational divide and South Africa. This included Jan, our sound man from the Czech Republic.

It’s often only when a sound designer has done a bad job that a casual viewer notices the design; a “clunk” or “buzz” that sounds fake or misplaced or too loud. When done well, few in the audience will think about how the sound contributed to the experience, and fewer understand the process: during the shoot, Jan focused on getting “clean” audio from the people filmed. But, at the same time, he carefully noted the unique flavor of the different spaces we visited, from the busy streets of the Jo’burg central business district, to the outskirts of the Drakensberg, Limpopo’s villages, the walled suburbs of Houghton, and the buzzing Sunday afternoons of Daveyton township. Each of these places sounds different, and each needs to be reflected as such, or it might read false to a viewer who knows the place, if only on a subconscious level.

After the cameras have stopped rolling, it falls to the sound designer to create a world through sound that is both engaging and natural. They will reengineer spaces by adding backgrounds, effects and music, while saving auditory “room” for dialogue, always in service of emotion and story. Someone who has been to Durban, on South Africa’s east coast, knows that it sounds unique, even if they can’t put their finger on the balance of voices, atmosphere and the things that makes it so. When you’re recording on the day, you can’t capture all that, so Jan and a team “build” it, sometimes long after the shoot, in post-production.

After 18 months of picture editing, we began the sound work, with a team of three designers. We met for a review session. Watching a scene outside the family store, I noticed a weird, faint beat. In the background, one of the designers had layered a subtle track of djembe drums. She told me that she had wanted to add something with an African flavor. I laughed and told her that the drums are African, but they don’t make much sense being in the background of a scene downtown. We put in some house music from a passing taxi’s radio instead and moved on to the next scene.

When making a documentary, you live between trying to tell a real story and trying to entertain. But there is sometimes a gulf between these two because entertainment relies to some extent on fulfilling the expectations of a pre-existing genre, regardless of reality. The conventions of these genres are often simplistic: for romantic comedies, the guy and the girl should live happily ever after; likewise, in Africa, there should be djembe drums.

A South African film is operating within a broader international narrative that already has expectations about the concept of “Africa.” These can manifest as expectations about certain kinds of music or voices, certain visual cues, certain people, and more generally, certain kinds of stories. The international success of a documentary can sometimes seem reliant on the extent that it lives up these expectations: stories about poverty in Africa, war in the Middle East, drugs and gangs in Central and South America. If you want to make a film about the Far East, and you want to put butts in seats, you better make it about some kind of human rights violation.

Obvious evidence for this comes from looking at the bodies that provide institutional support. Today there are very few places to apply for documentary production grants if you are not making work about a social justice issue. It can feel like a film taking place in Africa is looked on skeptically by funders if it doesn’t address race or poverty directly. Take a look also at the Oscar nominees for documentary over the last 10 years. The majority of them are about social justice issues, and those which take place in developing countries are far more likely to be so. This holds true for selections at many major film festivals too.

Social justice is an important part of documentary filmmaking, but these stories are not enough on their own to create a realistic sense of a place, person or culture. The documentary filmmaker Jon Ronson notes how journalists tend to look for the “gems” – the facets of a person or event that are most sensational – and then put these all together to make a gripping story. In films, there is a focus on the extreme elements of a society, like genocide, collapse or revolution. This is dangerous, because it doesn’t paint complete pictures of issues or people. A topic is not exclusively described by its extremes.

This incomplete description is more acute in developing parts of the world because there are simply fewer opportunities for stories to be told – with less funding and fewer people in a position to independently spread a unique story. So, a film about a mother and daughter’s eccentricities (Grey Gardens), or about pet cemeteries (Gates of Heaven), or a strange but brilliant artist (Crumb), might struggle to find funding and an audience even more if it comes from a developing part of the world, because it’s not the familiar (read: marketable) international narrative… “If this is a movie about Africa, why am I watching a story about a shoe salesman… we have those here.” Ultimately I think this is a tremendous loss, because these less “extreme” stories challenge preconceptions of elitist difference, while still providing a window onto the unique social fabric of a place.

On a personal level also, the preconceived narrative of “Africa” is tricky for me to navigate because I am not the ideal person to make a story about that Africa. I’m white, Jewish, a descendant of European immigrants to South Africa. I identify completely as South African, but I don’t speak a black language, and I don’t listen to the same music as most South Africans. That’s embarrassing for me to admit, but worse to fake. During the design, I started asking if maybe I should have djembe drums in a scene, and then I had to Wiki-check if djembe drums really even come from South Africa, because I grew up hearing Neil Young at my house, and when I Googled “current music in South Africa,” I found hip hop, not African percussion.

What options exist then while reporting on life from somewhere with a preconceived narrative? Maybe you go after your truthful narrative above all, at the expense of potential marketability – telling your story, say, of a town in India with a love of Superman (Supermen of Malegaon), without unnecessarily mentioning the war with Pakistan, or poverty or Mahatma Gandhi. Or, maybe you look for a middle ground – framing a story in a digestible way for an audience that will never totally grasp the complexity of a whole other life anyway, but at least will be able, here, to interact with some new part of the world (as in celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain’s series on CNN, Parts Unknown). Or should you cynically, accept that “narratives of truth” are decided by individuals anyway, and just give funders whichever narrative they want? I admit I feel tempted to do that sometimes.

Ultimately, it’s the representation of the complexity of truth that I respect most in documentary, and it just feels wrong when that plays second fiddle to entertainment. Sometimes it is frustrating when broad narratives don’t line up with reality, however this seems all the more reason to keep pushing for those stories that correct, improve and enrich the narratives we have from all over the world. And when it’s entertaining on top of that, all the better.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers