Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 299

October 10, 2016

My people them dey stay for poor surroundings*

Makoko, Nigeria. Image via Wikipedia

Makoko, Nigeria. Image via WikipediaIn 2012, the star architect Kunlé Adeyemi unveiled his “floating school” in Makoko, one of more than 100 slums in Lagos, Nigeria’s commercial capital. Most of Makoko’s residents, who are estimated between 40,000 and 300,000, live in makeshift structures built on stilts on lagoon water. The floating school, built by local residents, used wooden offcuts from a nearby sawmill and locally grown bamboo. It sat on 256 plastic drums and was powered by rooftop solar panels. The construction of the floating school gave new hope to residents hoping for more durable, permanent housing structures in the face of regular flooding. It was also viewed as a prototype for housing crises elsewhere on the continent.

One thing the floating school did not do was encourage government intervention to improve the lives of Makoko’s residents. Instead, residents were regularly subject to threats of eviction because Makoko is located on prime land. At best, the international attention (the school won a number of design prizes) slowed attempts by the Nigerian government to finally “clear” Lagos of the slum. It didn’t help when three years after the floating school was first constructed, it collapsed in June 2016, after heavy rainfall.

The global assessment of slums by UN-Habitat shows that 828 million people, or an estimated 33% of the urban population of developing countries, reside in slums. In sub-Saharan Africa, 62% of the urban population resides in such settlements. For Nigeria, the World Bank reported that as of 2015, 48% of the total population (estimated at more than 180 million) reside in urban centers.

Nigeria’s biggest cities – Lagos, Ibadan, Port Harcourt, Aba and Enugu – present a number of urgent problems for urban planners: urban decay, slums, overcrowding and lawlessness, which lead to the loss of land and natural resources. Lagos faces the most acute housing crisis. It began to expand at a breakneck pace with the oil boom of the 1970s. Lagos is now Africa’s largest city with a population that exceeds 10 million. The result has been over-urbanization, meaning that populations are growing much faster than local economies, leading to major social and economic challenges of slum proliferation.

In an effort to alleviate the housing crisis, the Lagos State Government (LSG) and its different agencies contributed a mere 27,000 housing units between 1950 and 2010. Considering that the population of Lagos tripled over this period of time, these efforts have done little to alleviate the acute lack of affordable housing for the poor or lower-class Lagosian. It is estimated that about 500,000 units of housing per annum over the next 10 years would be needed to keep up with the housing demand.

The deterioration of urban centers are the result of, but not limited to, the lack of enforcement of urban development and management regulations by city authorities, and the non-compliance to building laws by developers. Most city authorities in Nigeria are so overwhelmed by the rapid development and spread of informal settlements that their regulatory interventions make little impact. Secondly, the absence of a ‘maintenance culture’ for already existing housing infrastructure is missing from the Nigerian public housing market. The issues of repairs and maintenance are foreign to Nigerians causing rapid decay and deterioration of buildings which affects the sustainability of the urban environment and consequently leads to the development of informal settlements.

Though it is still unclear what the new government’s agenda is with regards to housing delivery regulatory reforms in the past 10 years are helping to create an enabling environment for housing delivery. The LSG plan formulated in 2012 provides a framework for housing, but it is not ambitious to resolve the housing and slum proliferation in the city. The plan focuses on promoting private housing estates or gated communities. Yet, this solely services the upper and middle-classes. A move in the direction of exclusively gated communities/private housing estates hampers societal development, promotes crime and classism.

The majority in Lagos lives in rented accommodation, and is at the mercy of landlords and estate agents who dictate a market that is poorly regulated and monitored. Despite 2011 tenancy legislation that imposes restrictions on advance rental payments, the law is not being enforced and landlords regularly request upfront payments of two or more years. Agency fees are another expense the law has been unable to govern. In Nigeria, agency fees top out at 10%, the highest on the continent. Thus, the urban poor are displaced and deprived access to decent and affordable housing, thereby rendering most of them “homeless.”

In 2014, the LSG launched the Lagos Home Ownership Mortgage Scheme, aimed at financing housing delivery. Under the scheme, the government provides the housing and funds the mortgage facility to be granted by a participating bank. First home buyers are expected to make a down payment of 30% and the balance of 70% spread over the next 10 years at 9.5% interest rate. Sadly, access to financing is still a major barrier for most people. Currently, the LSG is in collaboration with several organizations and initiatives that are increasing awareness on the issues, as well as developing sustainable housing solutions using local materials that are easily accessible, with implementation to commence in 2017.

*Fela Kuti – Coffin For Head of State (1981)

October 9, 2016

Black African immigrants, race and police brutality in America

Image: From Glenna Gordon’s series on Liberian immigrants in Staten Island

Image: From Glenna Gordon’s series on Liberian immigrants in Staten IslandPerhaps the most famous example of “African passing” is the infamous anecdote of former UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan. A student in 1960s U.S., Annan had traveled to the Jim Crow South. He needed a haircut, but was told by a racist white barber: “I do not cut nigger hair.” Annan, who is Ghanaian, responded: “I am not a nigger, I am an African.” In doing this, Annan did not challenge the degradation pre-assigned to him by virtue of his skin color, and accepted the premise that there is something inherently pathological about American blackness to which black people from Africa are impervious.

This line of thought is not uncommon. As Chimamanda Adichie, herself a Nigerian immigrant to the U.S., has stated: “When you’re an immigrant and you come to this country, it’s very easy to internalize the mainstream ideas. It’s easy, for example, to think, ‘Oh, the ghettos are full of black people because they’re just lazy and they like to live in the ghettos.’”

The evidence put forth by the characters that showed up from America on our living room TV in Tema, in Ghana where I spent my early life, seemed bent on conveying that black people were a problematic sect in the United States. Whether from CNN’s discussion of crime and violence, or in the rap videos buoyed by the twin manifesto of brute force and wealth, this perennial drip feeding meant that even before our plane had taken of from Accra and headed to JFK, I’d be admonished by extended family, pastors, market women and an air hostess – none of whom had lived in America – to not become like “those black people,” the Akata people.

The problem of such marching orders is that in America the definition of blackness – with its complex history – often lies in the eye of the beholder. It is as the truth for many Africans, as the novelist Yaa Gyasi wrote, that “when my little brother had the police called on him by our new neighbors while riding his bike on a nearby lot, he couldn’t say to those officers, ‘It’s O.K., I’m Ghanaian-American’.”

Unlike in Kofi Annan’s (problematic) case, most Africans – particularly poorer immigrants – don’t get a “get out of black free” card in instances of race prejudice. It wasn’t the case when four plainclothes officers shot Amadou Diallo (an immigrant from Guinea in West Africa) 41 times, as he pulled out his wallet in 1999. Seventeen years later we are again suffering with the tasering, shooting and summary killing of Ugandan immigrant, Alfred Olango, in San Diego. What these acts of police violence show is that the desire to self segregate in matters of race prejudice is indulging in a fantasy.

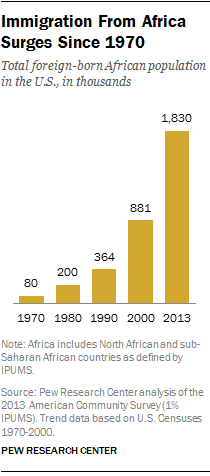

The fantasy may derive from a superiority complex. As Pew research shows, there are more African immigrants with college degrees relative to the overall U.S. population. But respectability or the lack thereof is no reason for someone to die, no matter their race. What matters is that the black immigrant population has grown by 137 percent in the last decade, and forms a relatively larger percentage of the overall U.S. black population. In America these days, Africans are the new blacks. Studies show that by the second generation many black immigrants lose the cadences and other linguistic signs that their parents still maintain. Children leave the tightknit community to go to college, and families in general disperse around the country in search of education and better opportunities, melting into the general black experience in America. Whatever challenges stand in the way of black individuals and families in the U.S.are our prerogatives.

Consider, for instance, the revelation from the National Academy of Sciences’ report on the integration of immigrants into American society. The finding show that black immigrants are “more likely to be poor than the native-born, even though their labor force participation rates are higher and they work longer hours on average.” Although the poverty rate for foreign-born persons in general declined over generations to match the native born, poverty levels among black immigrants rose to match that of the native black population.

Since black immigrants make up a double-digit share of the overall black population in some of the largest metro areas for instance, we have to accept the fact that African immigrants will be victims of the larger epidemic of gun violence that has disproportionately targeted people of color in America. Another tragic aspect of Olango’s case is the fact that he was a refugee. But that is hardly unique; about one-third of immigrants from Africa enter the U.S. as refugees. In Olango’s case, he had had fled his hometown Koch Goma, living briefly in Gulu before traveling to the United States in 1991.

So, you can imagine the extra pain of toiling, through persecution, surviving through camps, making the journey here and putting up with all of the challenges of adapting to a new society and culture in order to construct a home for your family only to have all of that sacrifice and work annulled by the lack of self control or training of an American policeman. As Agnes Hassan, a Sudanese refugee who had been in a camp with Olango asked “We suffer too much with the war in Africa, we come here also to suffer again?”

I remember very vividly, the late afternoon of December 13th 2014 at the Justice for All March in D.C. when Amadou Diallo’s mother, Kadiatou Diallo, said from the stage: “This sorority of sisters, we the moms, we don’t want to belong to this group. We’ve paid a heavy price to be here.” The sombre statement struck my heart, but it was her accent, reminding me of my mother, which was dispiriting and discomforting. It really could have been my mother up there at that moment.

We minimize the power and stake that African immigrants have in the conversation about racism when we forget it was the case of Amadou Diallo, an African, that was one of the first to mobilize protesters and demonstrations against police brutality on a large scale; and in a city like New York nonetheless. Since then we have protested the killings of Sudanese Jonathan Deng, Cameroonian Charley Keunang or Deng Manyoun in Kentucky among myriad cases that we don’t know about because they didn’t trend as popular hashtags post mortem, or they were struggling refugees with no extended family to advocate for them in life.

It can be tempting to want to compare police brutality here to violence back home, as the Nigerian author Adaobi Nwaubani did, when she told PRI after the first presidential debate “I don’t want black people, or white people or whomever to be shot and killed in interactions with the police [in the US], but I can’t pretend that I’m horrified by the fact that the police stopped and searched someone.” This, however, overlooks centuries of targeting and persecution of black people in the country’s history. (Nwaubani, incidentally, also told PR “stop and frisk” does not strike many Nigerians as remarkable.)

As the report from the UN expert group on People of African Descent puts it, “contemporary police killings and the trauma it creates are reminiscent of the racial terror lynching of the past. Impunity for state violence has resulted in the current human rights crisis and must be addressed as a matter of urgency.” Note US Supreme Court Justice, Justice Sotomayor’s suggestion that the “way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to speak openly and candidly on the subject of race, and to apply the Constitution with eyes open to the unfortunate effects of centuries of racial discrimination.”

How would Alfred Olango have known before he texted his friend Steven Ojok back in Kampala on Sunday “you know what, man, I am taking my daughter for dinner”, that there was a coffin with his name on it.

October 7, 2016

Congo Blues

Joseph Kabila, President of the DRC, addresses the UN General Assembly in 2014. Credit: MONUSCO Photos

Joseph Kabila, President of the DRC, addresses the UN General Assembly in 2014. Credit: MONUSCO PhotosLast month, on September 19, protestors descended on the streets of Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), barricaded roads and burned tyres. At issue was forcing President Laurent Kabila to agree to a calendar for the 2016 presidential elections. (In February 2012, the country’s electoral commission scheduled the next presidential elections for November 27 this year, but Kabila has been stalling.)

The following night, some offices of President Kabila’s political party were set on fire, presumably by protestors. The next day, soldiers allegedly set fire to offices belonging to opposition political parties. The government reported 17 deaths as a result of altercations. Opposition political parties estimated that more than 37 people were killed.

The most obvious reading of the ongoing pre-electoral unrest suggest that the DRC is at the brink of another collapse. Pessimism is driven by the fact that in the past 20 years the DRC has been characterized by widespread armed-conflicts and social turmoil. In order to make sense of the current political stalemate we need to consider two important moments in the recent history of DRC: First, the 2005 constitution, and, second, the January 2015 popular outcry over a proposed electoral law that based the 2016 presidential elections on a general census.

In 2005, following years of political uncertainty, Congolese voted for a new constitution. Two provisions dealt specifically with presidential elections. A key provision in the new constitution is Article 70. It limits presidential terms to two, five years each. In addition, Article 64 of the constitution states that “ [a]ll Congolese have the duty to oppose any individual or group of individuals who seize power by force or who exercise it in violation of the provisions of this constitution.”

Kabila is the second longest ruling Congolese president after Mobutu Sese Seko. In Mobutu’s 32 years of dictatorship, political dissent was heavily repressed until Laurent Kabila, aided by Rwanda and Uganda, took power in 1997. In 2001 Laurent Kabila was mysteriously assassinated by one of his bodyguards and his son, Joseph Kabila, through bizarre political machination, became the fourth Congolese president. Throughout his 15 years in the presidency, Joseph Kabila’s legitimacy has been contested. Since 2005, the DRC has had two presidential elections; in 2006 and 2011. Both presidential elections tested the Congolese democracy. Though both elections were heavily disputed, Kabila emerged victorious. The main losers of the two elections, Jean Pierre Bemba and Étienne Tshisekedi, did not pick up guns, instead choosing instead to wait for the end of Kabila’s presidential term to compete again.

Most Congolese assumed Kabila respected the constitution and wouldn’t run for a third term. Emboldened by Article 64, opposition Congolese political parties and their sympathizers were determined to oppose any attempt to extend Kabila’s presidential bid. Everything would come to a head when, in February 2012, the Congolese Independent National Electoral Commission scheduled the next presidential elections for November 2016.

In January 2015, Kabila’s supporters suddenly argued that a new general census was needed in order to establish more accurate voters’ lists. Many in the political opposition interpreted this as a delaying tactic: it would postpone presidential elections by about four years, thus extending Kabila’s presidency. Congolese opposition parties and their followers descended into the streets of Kinshasa and other parts of the country in protest. More than 40 protesters were killed. But the popular uprising forced the government to back down from the proposed electoral law. The only available option left for Kabila to extend his presidency was to delay the elections through political stalemate or other mechanisms, known as glisment électorale or electoral sliding. (In the DRC electoral sliding is an instance in which claims of administrative inadequacies and or political calculations are used to delay the electoral calendar for few months or years.)

However, the sense this time around is that political dialogue will prevail over the language of weapons. Even more significant, is the demand from the ground up for political accountability. This signals two important facts: One, that the people are demanding that institutions, at least the electoral process in this case, function as they ought to, and, two, that the people are basing their political resistance on the law of the nation, as opposed to mere political partisanship.

Undoubtedly the political fate of DRC depends on whether Kabila leaves power peacefully or not. Kabila alone knows where he stands; however, so long as he does not publicly recuse himself from running for a third term many Congolese, including myself, will be suspicious of any dialogue proposed by the government.

October 6, 2016

Transnational Eugenics

Eugen Fischer, an infamous German eugenicist who studied “racial mixing” in colonial Namibia, and whose theories inspired Adolf Hitler, and later eugenics researchers at South Africa’s Stellenbosch University.

Eugen Fischer, an infamous German eugenicist who studied “racial mixing” in colonial Namibia, and whose theories inspired Adolf Hitler, and later eugenics researchers at South Africa’s Stellenbosch University.In mid-September, writer Adam Cohen’s Imbeciles: The Supreme Court, American Eugenics, and the Sterilization of Carrie Buck (published by Penguin this year) . (The awards will be announced today.) The book explores a deplorable moment in early 20th-century American history when much of the American establishment – from John D. Rockefeller Jr. to Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes – were ardent supporters of “eugenics,” the pseudo-scientific classification of humans according to supposed “superior” and “inferior” traits.

The crackpot racial science that underpinned the eugenics movement provided the justification for the sterilization of those who were declared feeble-minded, and the well known Supreme Court decision in Buck v. Bell, which is the focus of Cohen’s book, legitimated such a practice in 1927. But, as readers of AIAC no doubt know, the eugenics movement also perpetuated the racism and anti-Semitism that constituted much of mainstream politics in the US, Europe, and colonial Africa for a good part of the 20th century.

Yet, few works, including Cohen’s, sufficiently recognize the truly transnational character of the eugenics movement, and the ways in which experiments conducted in colonial Africa served as the launching pad for the propagation of ideas and practices that were central to the movement elsewhere in the world. To unpack some of these elements, I interviewed Steve Robins – an anthropologist at the University of Stellenbosch – about his book, Letters of Stone: From Nazi Germany to South Africa, which was also published by Penguin this year (and only available on Amazon if you do not happen to be in South Africa).

Robins’ book tells the story of a Jewish family that is torn apart by events in Nazi Germany in the 1930s and 1940s. It follows the lives of his father and uncle who settle in South Africa during the 1930s, and pieces together the gradual dehumanization and eventual extermination of those relatives who remained behind in Germany.

The story begins with a mysterious photograph. What is the significance of that photograph?

When I was growing up in Port Elizabeth I was aware of a photograph of three women in the dining room, but I didn’t know who they were. I had a sense that they were my father’s family and that they died in Germany during World War II, but no one spoke about them. I didn’t even know their names. It was only much later in life that I discovered that they were my father’s mother and his sisters, i.e. my grandmother and aunts. Those are very close relatives, and yet they weren’t talked about. I was particularly haunted by one of my father’s sisters, Edith.

The book is multi-layered and multi-genred. It is part memoir, part social history, part ethnography. Let’s turn first to the book as memoir, as a personal history of your family in South Africa and of your German relatives. Much has been written about the Holocaust, the death camps, why is this book different?

What makes it different is the time period and the way it crosses continents. The part of the book that deals with my family history really focuses on the 1930s whereas many films, books, exhibitions focus on the early 1940s and particularly on the extermination of Jews. I was incredibly fortunate to have access to family letters to tell a different story. The letters begin in 1936 after my father has emigrated to South Africa and continue until the family who remained in Germany (except for my father’s brother who also comes to southern Africa) was deported and exterminated.

This is a period when the family members don’t know what will happen to them. They are subjected to a raft of about 100 racial laws introduced in 1933 that strip them down to bare life. Throughout this period my father’s family is desperately trying to leave, but the dehumanization of Jews – the stripping of their citizenship, their dignity, their belongings, the process of making them invisible – is relentless.

I wanted to capture the incremental paring down of their lives and I also wanted to show the quotidian or everyday aspects of life that are conveyed by the letters. They are a portal into what this family did with their lives on an everyday basis: the card games they played, the food they ate, their conversations with friends while at the same time my grandmother – who wrote most of the letters – is desperately trying to hold this transcontinental family together and worrying about the health of her sons in Africa. I wanted to do justice to those letters while recognizing that these are not my memories. They belong to others.

For your father and his younger brother, the escape to South Africa in the 1930s saves their lives and allows them to start over again. Your father spends the rest of his life in Port Elizabeth, but South Africa in the 1930s was hardly welcoming to Jews. Can you tell us what was going on and what the effects were on Jewish emigration to South Africa?

During the 1930s and 1940s a number of rightwing Afrikaner nationalist movements, such as the Grey Shirts and Ossewabrandwag, emerged with the aim of mobilizing poor white Afrikaners who had been displaced from the land in the 1920s. These rightwingers, as well as the more mainstream Afrikaner nationalists, portrayed Jews as a particular threat to poor whites because of their purported uncanny commercial acumen, secret brotherhoods and dominance in commerce and the professions. This mobilization culminated in campaigns to prevent German Jews, like my father’s family in Berlin, from finding refuge in South Africa at a time when the clouds of fascism were sweeping across Europe. In 1937, Afrikaner nationalists, such as D.F. Malan and H.F. Verwoerd, successfully lobbied the Hertzog-Smuts government to introduce the Aliens Act, which shut the door on German Jews attempting to flee Europe.

In fact, throughout the book, you draw several linkages between the discrimination against, and the destruction of, Jews in Germany and the exploitation of Africans during the colonial and apartheid periods. Can you talk about what those linkages were and why you thought it was important to connect the two?

Typically accounts of the Holocaust present this catastrophe as a unique event that cannot be compared to any other genocide. This also implies a hierarchy of suffering. In 1996, while visiting the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C., I stumbled across an account of Eugen Fischer, a German anatomist and physical anthropologist who, in 1908, studied the consequences of “racial mixing” amongst the Rehoboth Basters in German South West Africa. Fischer’s study was internationally acclaimed, and helped launch his career as a leader in the field of eugenics. When Hitler came to power in 1933, Fischer’s career took off further and he soon became the leading Nazi racial scientist. Together with the Herero and Nama genocide, Fischer’s scientific career hints at the role of the colonies as laboratories for the incubation of racial hygiene ideas that later boomeranged back to Europe. This calls for us to recognize the entanglement of colonial and European histories of scientific racism and genocide.

To continue the line of thought above, can you talk about the challenge of balancing a personal, emotional story with a more social science approach, as you do when you discuss racial eugenics and the embrace of it not only in South Africa, but also Europe and the US?

I did not want this book to simply be a Holocaust family memoir. Quite early on, I began to realize that the personal story of my family needed to be situated within the wider canvas of world historical events of the 20th century – colonialism, the Shoah and Apartheid. I felt the intertwined histories of the 20th century that my father’s family bumped up against in Europe and South Africa needed to be told in a way that transgressed the straightjacket of histories that stop at the borders of nation-states. This was made very apparent by the transnational scientific trajectory of Eugen Fischer, whose scientific ideas influenced global eugenics as well as immigration restriction policies in Europe, the US and South Africa.

One of the strengths of the book is that it draws attention to the participation and the contribution of many countries, not just Nazi Germany, to the rise of global eugenics

Yes, I wanted to decenter the conventional account of the racial science that underpinned the extermination of Jews, which is typically confined to what happened in Europe; but the United States was one of the leaders in the study of racial eugenics in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Already by 1924, the US had adopted an Immigration Restriction Act establishing quotas for so called “inferior races” who were coming into the United States from Eastern and Southern Europe and these included Jews, Slavs and Italians. Great Britain too had its share of scholars who were involved in the eugenics movement. As Keith Breckenridge has shown, Sir Francis Galton drew on observations of indigenous peoples in the 1850s in what is now Namibia to inform his views on Britain’s urban poor and the “lower classes.”

So the Germans were relative latecomers in this respect. In fact, Fischer’s institute, the Kaiser-Wilhelm Institute in Berlin, was partially funded by both Carnegie Institute and the Rockefeller Foundation.

In some ways, the book clearly implicates also the social sciences in the growth of “racial science”

Anthropology, as I mention in the book, was implicated in the science of racial classification, taking measurements, using anthropometric photographs, collecting artifacts and devising intelligence tests. But, for a long time, anthropology has been doing a lot of critical reflection on race, and on the connections between anthropology and colonialism. Starting with Franz Boas at Columbia in the 1920s, there’s been this effort to unpack the association. Boas refuted the ideas of popular eugenicists, such as Madison Grant, HH Goddard and Charles Davenport. On the other hand, other disciplines, such as sociology and political science, haven’t done this kind of soul searching.

I was surprised to learn in the book that Karl Pearson, famous for Pearson’s correlation coefficient, was a committed eugenicist, who relied on statistics to “prove” the superiority of the professional classes and even advocated removing indigenous people in Uganda for the benefit of Britain. Anyone who uses stats – from simple correlations to big data – knows of Pearson.

The book tries to address some of that. It is part memoir, but also an engagement with the social sciences and even my own place of work, the University of Stellenbosch. When it was founded in 1926, the Volkekunde Department at Stellenbosch (the precursor to the anthropology department) was heavily influenced by racial science. In fact, in 2012, the curator of the museum at Stellenbosch found a skull and several eugenics measuring devices that belonged to the old department. They included a hair color table in a silver case engraved with Eugen Fischer’s name.

Finding Fischer’s “scientific footprint” at Stellenbosch University reveals the transnational character of scientific ideas such as eugenics. This is also part of a film I am making with Mark Kaplan that links together Fischer’s study of the Rehoboth Basters with the racial science policies propagated by the Nazis. In 2015 we also ran a Mellon Foundation-funded project called Indexing the Human that included a series of lectures focused on questions of racial classification and histories of the social science disciplines at Stellenbosch University.

One very important thread in those entangled histories is the parallel you draw with Apartheid.

In fact, that is how I got interested in this. Attending the hearings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1996 and hearing all these stories from South Africans whose family members had died in detention or disappeared triggered my interest in wanting to know more about my family. Many of those who spoke in front of the TRC, they knew their family members were gone but they just wanted to know how they had died and where their bodies were. And that got me started on the journey.

You spoke earlier about the anti-Semitism that your father confronted when he first arrived in South Africa. Why did the treatment of Jewish South Africans change after WWII? Would you say some were co-opted into supporting Apartheid? Having experienced so much discrimination in Germany, Lithuania etc. why do you think some Jewish people overlooked the treatment of Africans during Apartheid while others clearly challenged it?

During the 1930s, South African Jews were fearful of the consequences of rising anti-Semitism and increasing support for Nazi Germany. Afrikaner hostility towards Jewish immigration intensified in the build-up to the war, and later nationalists and future prime ministers B.J. Vorster and Verwoerd openly supported the German war effort. In fact, Vorster was interned at Koffiefontein detention center for his pro-Nazi stance. After the war, Prime Minister Malan’s ruling National Party did a complete about turn. Malan visited Israel in the early 1950s and returned very positive about future relations with the Jewish state. This created the conditions for a long-term rapprochement between Afrikaners and Jews. Whereas the whiteness of Jews had been questioned by both the English and Afrikaners during the early part of the 20th century, the post-war era ushered in a period when the National Party invited Jews into the white fold. It was their concern for their place in the white social order that pushed mainstream Jewry into a Faustian bargain, whereby they became bystanders as Apartheid laws were enforced. It was left to radical Jews in the Communist Party to forcefully resist Apartheid. They become the torch bearers of the historical memory of anti-Semitism and anti-fascism in Europe and South Africa.

Another sub-theme in the book is the complicated relationship that Jewish South Africans have with Israel and Palestine. Can you elaborate on this?

Attending Theordor Herzl Primary School in Port Elizabeth in the early 1960s, I was exposed to an understanding of the Shoah that was tightly tethered to Israeli nationalist accounts of the making of the Jewish state. In this account, the Shoah was spliced onto an ethno-nationalist narrative of collective suffering and redemption. But over the years I began to question this account and I now endorse the late Edward Said’s comment that the Palestinians have become “the victims of the victims”. This has made me increasingly suspicious of all ethno-nationalist projects that appropriate historical accounts of collective suffering for instrumental political ends.

It’s hard to know how to categorize this story – is it personal memoir? At one point, on page 41, you seem to admit it is not your story, that you are “intruding upon… cannibalizing my father’s memories.” On the other hand, in an email to me you called it “experimental ethnography.” Can you explain? What are the challenges in this kind of writing?

While I was writing this book I was not particularly concerned with questions of what genre I was writing in. I was conscious of crossing genre boundaries but it is only now, after the book’s publication, that I have begun to think about this book as an experimental ethnography-cum-family memoir-cum-social history.

To conclude, tell us the significance of stumbling stones or the Stolpersteine, which the title references?

In 2000, the German artist Gunter Demnig laid these small bronze commemorative plaques into the stone pavement outside the Berlin buildings that my father’s family members were deported from. These material objects of memory – with victims’ names and dates and destinations of deportation – reside in everyday, public spaces. Their small size and subtle presence appeals to me precisely because these plaques do not impose themselves on the urban landscape. You hardly notice them until one day the tip of your shoe may bump up against one of them. In fact, the name Stolperstein, which translates into “stumbling stone”, resonates with the ways in which I stumbled across the traces of my family’s past in Germany and South Africa.

October 2, 2016

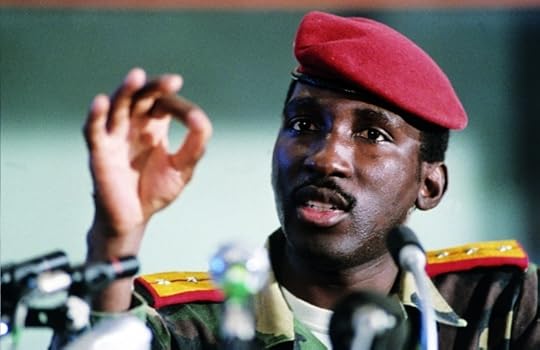

The Upright Man, Thomas Sankara

Burkina Faso is finally beginning to do right by the memory of Thomas Sankara: Yesterday, a foundation in Sankara’s name, unveiled plans for a public memorial. This happens nearly 29 years ago this month after he was murdered and two years since Blaise Compaoré–considered one of the key people responsible for Sankara’s murder– fled the country.

Throughout this time, Sankara remained an inspiration to young Africans and people committed to a radical pan-Africanist future. His supporters and admirers argue that his short four-year reign as President of Burkina Faso from 1983 to 1987 – for all its faults – pointed briefly to the potential of different political futures for Africans, beyond dependency, neocolonialism and false dawns of “Africa Rising.”

Plans for the memorial and a museum were announced at a symposium in Ouagadougou held in Sankara’s honor and attended by nearly 3,000 people. As the BBC reports: “The proposed memorial is estimated to cost around $8m (£6.2m) and will be funded by small contributions from supporters of the former Burkinabe president.”

On October 15, 1987, armed men burst into the office of Sankara, murdered him and twelve of his aides in a violent coup d’état. In events that eerily paralleled those in the Congo 27 years earlier (when a conspiracy of European intelligence agencies and their Congolese surrogates murdered Patrice Lumumba), the attackers cut up Sankara’s body and buried his remains in a hastily prepared grave. The next day Compaoré, who was Sankara’s deputy, declared himself president. Compaoré then went on to rule the country until 2014, when he was forced to flee the country amidst a popular uprising. Between 1987 and 2014, Compaoré both attempted to co-opt and distort Sankara’s memory and making promises to bring his murderers to justice. Nothing ever came of that.

Burkina Faso (known as Upper Volta until 1984) didn’t attract much attention outside West Africa until Sankara overthrew the country’s corrupt and nondescript military leadership in 1983. (It bears repeating that Burkina Faso had been ruled by military dictatorships for at least 44 years of its independence from France. The military before Sankara basically acted as surrogates for French interests in the region. One year after Compaore fled, there was a brief one week coup, but the country has been ruled by democrats and figuring out a new constitution since then.)

Like Lumumba – an earlier principled political leader who was a violent casualty of the Cold War – Sankara proved to be a creative and unconventional politician. He wanted to a chart a “third way,” separate from the interests of the major powers (in his case, France, the Soviet Union and the United States). This, however, resulted in a complex legacy where those who praise his social and economic reforms — discussed below — have a hard time squaring it with his often-undemocratic politics.

In 1985, Sankara said of his political philosophy: “You cannot carry out fundamental change without a certain amount of madness. In this case, it comes from nonconformity, the courage to turn your back on the old formulas, the courage to invent the future. It took the madmen of yesterday for us to be able to act with extreme clarity today. I want to be one of those madmen. We must dare to invent the future.”

The documentary film, Thomas Sankara: the Upright Man by the British filmmaker Robin Shuffield, is probably the best filmic account of Sankara’s rise, governing style, reforms and his eventual murder. It also gives some sense as to why–unlike say Lumumba among Third World nationals or Nelson Mandela among Western elites–people beyond West Africa (and now with students in South Africa) don’t mention Sankara much these days (except for those with more than a passing knowledge of postcolonial African politics).

Sankara openly challenged both French hegemony in West Africa as well as his fellow military leaders (Sankara labelled them “criminals in power”). He called for the scrapping of Africa’s debt to international banks, as well as to their former colonial masters. Check the many clips of him doing just that at public events in Harlem, New York or Addis Ababa.

His reforms were widespread, both at a symbolic level and in terms of political and economic reforms. For one, in 1984 he changed the country’s name from Upper Volta, the name it kept from colonialism, to Burkina Faso. The country’s new name translates as “the land of the upright people.”

Sankara preached economic self-reliance. He shunned World Bank loans and promoted local food and textile production. (There’s a classic scene in Shuffield’s documentary where he had the whole Burkina delegation to an Organization of African Unity meeting decked out in local textiles and designs.)

Sankara outlawed tribute payments and obligatory labour to village chiefs, abolished rural poll taxes, instituted a massive immunization program, built railways and kick-started public housing construction. His administration aggressively pushed literacy programs, tackled river blindness and embarked on an anti-corruption drive in the civil service.

Women, the poor and the country’s peasantry benefited mostly from these reforms. His administration promoted gender equality in a very male-dominated society (including outlawing female circumcision and polygamy). As Sankara told a local audience in 1984: “Socially, [women] are relegated to third place, after the man and the child — just like the Third World, arbitrarily held back, the better to be dominated and exploited.”

He discouraged the luxuries that came with government office and encouraged others to do the same. He earned a small salary ($450 a month), refused to have his picture displayed in public buildings, and forbade the uses of chauffeur-driven Mercedes and first class airline tickets by his ministers and senior civil servants.

But Sankara’s regime was not immune to undemocratic practices.

He banned trade unions and political parties, and put down protests (most significantly one by teachers in 1986). Many people were the victims of summary judgments by people’s revolutionary tribunals, which sentenced “lazy workers,” “counter-revolutionaries” and corrupt officials. Sankara himself would later admit on camera that the tribunals were often used as occasions to settle private scores.

By 1987, he was politically isolated. His enemies – a mix of the French political establishment (he had humiliated President François Mitterand in public on a few occasions) and regional leaders (like Ivorian President Félix Houphouët-Boigny) – began to tire of him.

Compaoré is widely suspected to have ordered Sankara’s murder in order to do the French and regional dictators a favor. Though Compaoré pretended to publicly grieve for Sankara and promised to preserve his legacy, he quickly set about purging the government of Sankara supporters.

In contrast to the cool reception given Sankara earlier, Compaoré was welcomed by Western governments and funding agencies. Within three years, Compaoré had accepted a massive IMF loan and instituted a structural adjustment program (largely seen as one of the major causes for the ongoing economic crises in Africa). Compaoré also reversed most of Sankara’s reforms. Not surprisingly this included the insistence that his portrait hang in all public places as well as buying himself a presidential jet.

While he was in power, Compaoré proved reluctant to investigate Sankara’s death fully. His government wanted to “move on.” Compaoré – whose regime had been implicated in the civil wars in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Cote d’Ivoire and Liberia – even tried a makeover as a “democrat” (he won a series of elections in the 1990s and 2000s), and was a key ally of the US.

After Compaoré fled the country in 2014, he, along with fourteen senior army officers, were indicted for their role in Sankara’s murder. However, the case has stalled.

As Mathilde Monpetit wrote on AIAC in July 2015, Sankara was a key inspiration of anti-Compaore protesters, some even identifying as “Génération Sankara.” But Monpetit wondered aloud about the renewed interest in the liberation politics that Sankara represented; “Is this renewed interest indicative of a revived interest in socialism, or simply the grasping of a people looking for a leader after the end of a political era? Sankara may simply stay the Che Guevara of Burkina Faso, in death representing an image of Burkinabè anti-colonial discontent that need not be compatible with the actions or ideology of the people who put his image on their shirts and walls.”

This weekend’s symposium, however, suggested that Sankara remains a real presence for social movements (and some governments) in Africa. Present were, for example, were activists of Balai citoyen, the citizen movement which played a role in the 2014 uprising in Burkina Faso, as well as Fidel Barro, one of the leaders of Senegal’s Y’en a Marre. Burkina Faso’s cultural minister told the audience: “Those who killed Thomas Sankara simply cut the tree, forgetting the roots. Now, we all know, the strength of the Baobab is based in its roots. Whatever they did, Thomas Sankara remains alive forever.” The foundation building the memorial and the museum insists, however, that it be build by the people and not the state.

The last word goes to Barre told an AFP reporter: “There is a Sankara for economics, a cultural Sankara, an avant-garde Sankara, a Sankara for the democratization of [political] power, a Sankara for the freedom of expression and speech. It is all these Sankara that these youth have come to admire because they want that Africa moves forward. They need that Africa becomes independent. Sankara goes beyond Burkina Faso, he is an African and World treasure.”

* This post draws on a piece I wrote for The Guardian in October 2008 as well as reference a number of posts written on Burkina Faso on this site.

October 1, 2016

Weekend Music Break No.99

After a bit of a vacation, our end of the week round up of 10 videos from or attached to the continent of Africa are back! Enjoy this catch up edition of the Weekend Music Break, curated by your resident praise DJ on our Youtube Channel.

Weekend Music Break No.99

1) First up we have a major global music event with the release of the video for the sonic collaboration between North American First Nations deejay group A Tribe Called Red, Iraqi-Canadian rapper The Narcicyst, and the entire world’s favorite local rapper Yasiin Bey. 2) Next, Al Sarah and the Nubatones release “Ya Watan” off of their latest album out on Wonderwheel Recordings. 3) I’m in awe of the choreography in the video for “Soudani” by Afrotronix from Chad, who is another Montreal-based artist showing the vibrancy of the independent and global music scene in Canada. 4) I’m really happy that Donae’o keeps pushing the UK Funky sound he helped popularize globally in Afropop directions. His “Party Hard” remains as one of if not the foundational song for the global Afrobeats craze. 5) And to illustrate that connection, Nigerians Naomi Achu and Skales come with “Gbagbe” an Afropop song tailored to the day. 6) Africa is a Country contributor Young Cardamom and his collaborator HAB provide the lead single from the Soundtrack to Disney’s Uganda flick Queen of Katwe. 7) Since this writer is Rio de Janeiro based, I have to represent with the biggest Funk tune of the season here, “Malandramente”. Will it’s ubiquity remain through our summer into Carnival? 8) Brazil also has elections this weekend, and while we made a hesitant endorsement for the fraught presidential race in the US, we can give a much more enthusiastic thumbs up to the campaign of Marcelo Freixo who is running for mayor of Rio de Janeiro. And as this campaign jingle shows, we’re not the only ones! 9) Élage Diouf is another Canada-based African artist, and shoots his video for “Mandela” an a return trip home, showcasing the beauty and vibrancy of his homeland. 10) Foresta, Royal Blu & Lila Ike show a different side of Jamaica than we’re used to seeing, a nice change of pace, from the regular image pushed to outsiders by foreign media. And that laid back R&B tune is a perfect way to close out this weekend’s music break, until next time!

September 30, 2016

Mr. Zuckerberg goes to Africa

Image via Techpoint Nigeria

Image via Techpoint NigeriaIn late August and early September, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg visited Nigeria’s Silicon Lagoon and Kenya’s Silicon Savannah. Both visits were “surprises” for the locals and were also Zuckerberg’s first official trips to any African country.

As noted in a recent survey, Kenya and Nigeria are two of the five countries that host 50 percent of Africa’s tech hubs. Tech hubs and start-ups are increasingly seen as key to promoting innovation and wider economic growth on the continent, as highlighted also in the World Bank’s most recent World Development Report 2016, “Digital Dividends.”

Casually dressed in jeans and a t-shirt, Zuckerberg presented himself as a rapidly acclimatizing businessman, fearlessly jogging over the Ikoyi bridge in Lagos and eagerly sampling Nigeria’s jollof rice and Kenya’s ugali and fish. For self-mocking Nigerians, Zuckerberg’s humble disposition stood in stark contrast to that of the country’s local economic and political elites, who insist on their status displays through an impressive and imposing dress sense and numerous prefixes to their names – aptly summed up in this Twitter meme. Or as novelist Okey Ndibe suggested: if Zuckerberg were Nigerian, he would have more likely introduced himself as “Honorable Triple High Chief Sir (Dr.) Alhaji Mark Zuckerberg.”

Zuckerberg’s visit provoked a lot of enthusiasm and was considered proof that Nigeria and Kenya have now firmly established themselves on the global tech map. More generally, it offered a much-needed alternative to dominant global media narratives of Africa as the diseased, poverty-stricken and war-torn continent.

Zuckerberg’s personal story as a self-made business man also serves as an inspiration to many budding African entrepreneurs. It is not unrelated to the continent’s broader fascination with motivational literature, which now dominates many bookshop shelves, or with the neoliberal prosperity gospel of the numerous, flourishing Pentecostal churches. Like self-help books and charismatic pastors, St. Mark of Menlo Park’s visit provided some sense of hope. However, whether Africa will gain from Zuckerberg, or Zuckerberg from Africa, appears the more important question that needs to be addressed.

Zuckerberg is now the world’s sixth richest person, with Forbes estimating his wealth at $51.7 billion. In June 2016, the Chan Zuckerberg Foundation – which Zuckerberg and his partner Priscilla Chan established in December 2015 after the birth their first child – announced its first investment of $24 million in Nigeria’s tech start-up Andela, an amount equivalent to less than 0.5% of Zuckerberg’s estimated fortune. More crucial than the foundation’s investment in Africa’s tech community, however, are Facebook’s explicit strategies in recent years to expand its reach on the continent.

Despite a recent major PR mishap involving the explosion of the when the SpaceX rocket (which was going to launch the Amos-6 satellite and expand broadband internet on the continent), Facebook’s ‘charitable’ mission is to connect the next five billion. Furthermore, Facebook’s Free Basics app now enables African mobile phone users in 21 African countries to access a text-based version of Facebook free of charge while Facebook Lite allows users to run the application with less consumption of mobile data.

Clearly, Facebook is fast gaining ground on the continent: At the end of 2015, the number of Facebook users in Africa was estimated at 124.6 million and numbers continue to grow, particularly in – surprise, surprise – Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa. The growth potential offers Facebook plenty more opportunities in future to collect and trade personal data, or to sell ads aimed at Africa’s seemingly growing middle class (Facebook opened its first ad sales office in Johannesburg in June 2015).

The introduction of Free Basics in India provoked a heated debate as it was seen to violate the principle of net neutrality. Eventually, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) ruled that mobile operators cannot charge differential tariffs for data services, which prevented Facebook from introducing its free app. In the African context, Free Basics has solicited some debate but much less controversy and, so far, regulators on the African continent have not acted against the company.

However, during my recent fieldwork with mobile internet users (which is how most Africans access the internet) in Zambia, Free Basics was not frequently cited as a platform that many were enthusiastically embracing. As I reported in another post, what seems to be more crucial to Facebook’s penetration in Zambia is the sponsoring of social media by mobile phone operators through attractively priced prepaid data bundles. For example, Zambia’s largest mobile operator, Airtel, offers a social bundle that allows users to access social media for an unlimited time over a certain period (a day, week or month) for a low fee. Daily packages are popular and enable users to adjust their data spending according to their income that particular week. With a large proportion of Zambians in informal employment, earnings and incomes are often irregular and daily bundles offer a level of flexibility.

As a result of this, the nature of Zambia’s internet is largely determined by social media. SMS and email are increasingly replaced with Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp. Many small to medium-size businesses do not have websites but market their services on easily managed Facebook pages. Given the subsidized nature of Facebook through data bundles, mobile phone users receive a warning that they will incur data charges as soon as they leave Facebook. For this reason, most Zambian online news sites post full content of articles on their Facebook pages rather than hyperlinks to website content which will be more expensive for users to visit.

Ultimately, this creates an internet experience that largely takes place within the walls of Facebook, raising obvious questions about net neutrality. Zambia’s internet is increasingly a social media internet. So far, this has not as yet provoked a major debate in the country but in neighboring Zimbabwe, the Minister of Information, Communication and Technology and Courier Services recently ordered the Postal Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe to request mobile operators to suspend data bundle promotions amidst protests against government as part of the #ThisFlag movement.

Social media bundles, therefore, are a key instrument that both enable and disable mobile internet access. While so far, much critical debate has focused on Free Basics, data bundles may be the bigger key to Facebook’s growing empire on the African continent.

It remains to be seen who will be able to consume more jollof rice or ugali and fish as a result of this expansion: Africans or Zuckerberg? Facebook certainly enables African mobile internet users to cheaply communicate with friends, to resist state power occasionally and to do business. But the growing concentration of power in one platform raises many questions around net neutrality, datafication and privacy that may require a more critical debate – certainly beyond Zuckerberg’s modest dress sense.

*This is a compendium version of a series of three articles on digital technology and social media in Zambia’s recent elections published on the LSE Blog.

September 29, 2016

What next for Zimbabwe?

This Flag in Cape Town. Image via Wikipedia.

This Flag in Cape Town. Image via Wikipedia.Zimbabwe is going through an evolution, not a revolution. Over the past few weeks, pundits and analysts alike have debated about the future of the country’s nascent citizen movement. In a widely circulated post, the academic Blessings Miles Tendi cautioned against premature optimism, and listed the lack of a united opposition movement, the limited activist base of young middle class urbanites, and underestimating the role of the country’s military (still loyal to President Robert Mugabe) as key factors determining the movement’s fate in future. Meanwhile, Pastor Evan Mawarire (he made the viral #ThisFlag video that kickstarted the protests in Zimbabwe and its diaspora), is possibly in exile in the United States. Nevertheless, #ThisFlag managed to mobilize thousands of Zimbabweans for a national stayaway in June 2016 and tap into people’s simmering disappointment with the ruling Zanu-PF.

#ThisFlag is obviously not the first time that Zimbabweans have raised their voices. On and off over the past two decades, the people have repeatedly expressed their displeasure with the status quo. For much of the early 2000s they rallied behind the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), a coalition of trade unionists and civil society movements. Although the MDC and its allies were subjected to various forms of political repression, its electoral successes forced ZANU-PF into a Government of National Unity (GNU) in 2009. The GNU was, however, disbanded in 2013 when President Mugabe’s ZANU-PF won the elections with results questioned by many observers. But the election also exposed organizational weaknesses within the opposition movement and the MDC. Similarly, there are questions about the strategic direction and ideological coherence of #ThisFlag. Whether the movement can sustain itself is an open question and we know that the hashtags will change, but the demands of Zimbabweans for change will only grow.

So, what is different this time around?

For one, the economic crisis brought about by the GNU between 2009–2013 deeply effected the middle class in Zimbabwe. The majority of people are underemployed or unemployed. Zimbabwe has a staggering unemployment rate of about 80%. Those with jobs are underpaid or have not received their salaries in months or, in some cases, years. Second, is the decline of the industrial sector. There are fewer factories and the majority of large companies that once employed thousands have shut down or drastically reduced production. This summer, I went looking for the famous Kingstons bookstore in Harare, only to learn from an older book vendor at one of the flea markets that Kingston’s closed its doors a few years ago. He had worked there as a manager, but since the shut down has been unable to secure a job and was left with no option but to vend books on the street. The former Longman Publishing House, was functioning at less than 50% of its earlier capacity. In July, the once vibrant tobacco floors were deathly quiet. Locals joked that even city robbers are avoiding the tobacco farmers. Third, it is clear that rural Zimbabweans, who constitute the majority, bear the brunt of the economic crisis. Rural voters also happen to be the largest voting block and support base for the ruling party.

I interviewed an 85-year-old grandmother, living in a small village deep in the valley of Masvingo, in the southeastern part of the country. Unlike most of her friends she is fortunate to have watched all eight of her children grow up, get married and have children. Until recently she had no reason to vote against ZANU-PF or question the way in which it has run the country. She lived through the brutality of the colonial regime and so was willing to give the “boys” – the freedom fighters of Zimbabwe’s liberation war – a chance to right things. She is still a farmer. Her silos are packed with maize, groundnuts and round nuts. She is not in danger of starving. However, in 2016, she is heartbroken that her university educated 45-year-old son, his wife and their five children have relocated home to share her compound. She is still holding on to buckets of Zimbabwean dollars that are now worthless and mourning the loss of her livestock: she sold all her cattle one by one to educate her children who, in their late forties and early fifties, still do not own homes. She has watched her children spend their income on her grandchildren’s education, only to have those grandchildren return home empty handed and jobless. Today, she is frightened by the prospect that the US$500 she has saved under her mattress since 2009, can overnight be rendered useless.

In the early 2000s the option to leave the country and seek employment or political asylum abroad, despite the prohibitive costs, appeared the most logical strategy. Today, however, it is harder for Zimbabweans to migrate, in part because of the wide spread anti-immigration rhetoric in their favored destinations (South Africa, Botswana and the UK) and tougher immigration laws. Furthermore, in the last few months the government has introduced import bans that make cross-border trading unprofitable and undesirable. The majority of Zimbabweans supplement their incomes by engaging in cross border trading, importing goods from South Africa and other nearby countries to sell to the local market. The local use of the US dollar allowed more traders to make a decent living wage. However, the ban on importing certain commodities has robbed a significant portion of the population of their livelihood.

Then there is the collective fear of bond notes. The dollar has been the primary currency since the introduction of a multi currency system in 2009. In early May 2016, the government announced it would introduce a local version of the dollar. Central Bank Governor John Mangudya explained that the bond notes would be backed by a US$200 million loan from the Africa Export/Import Bank and that the local currency would have the same value as the US dollar. The announcement was not well received. Fearing a repeat of the period of hyperinflation witnessed between 2005 and 2008, anti-bond notes campaigns (hashtag: #notobondnotes) have become one of the key rallying points for citizen protests against the government. Zimbabweans are afraid of losing the little savings they have built up following the introduction of the multi currency system and do not trust the government not to over print money.

Finally, tensions within the ruling party have boiled over into the public sphere. Sections of the war veterans (the soldiers who fought in the 1970s liberation war against white Rhodesia) have turned against the ruling ZANU PF and President Mugabe and the vice president, Emerson Mnangagwa, who some see as a successor to the current head of state, was forced to publicly respond to allegations that he may be too ambitious. The challenge for Zimbabwe’s opposition, as Tendi argued earlier, is “… is a well-thought-out and pragmatic approach to the [upcoming] 2018 election [for which Mugabe, now 92 has declared his candidacy again] – one that will unite civil society, the opposition parties, online activists, and urban and rural youth. That is the key to finding a new path ahead.”

September 28, 2016

Budgets, bureaucracy and realpolitik trump human rights advocacy

Ayotzinapa protests via Montecruz Foto Flickr

Ayotzinapa protests via Montecruz Foto FlickrThe year 2015 was El Salvador’s deadliest since the end of that country’s civil war in 1992. According to police records, more than six thousand people were murdered. Elsewhere, in Honduras, Brazil and Columbia, dozens of environmental activists are under attack. And in the Dominican Republic, thousands of Dominicans of Haitian ancestry are on the verge of becoming stateless following the introduction of new legislation governing naturalization and citizenship.

When national legal systems in offending countries fail to address such attacks on human rights, the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights can step in and advocate for people or organizations on the receiving end of these violations. Founded in 1959, the commission is the branch of the Organization of American States (OAS) tasked with monitoring and protecting human rights; the referral body for cases brought before the Inter-American Court. The commission and the court are together referred to as the Inter-American System.

The court has been at the forefront of rights’ development. For example, in 2001, the Awas Tingni, an indigenous community in Nicaragua, won a landmark case against the government. The court’s ruling recognized the community’s right to communal property and recognized indigenous law and custom as a source of enforceable rights and obligations. The commission, in exceptional cases, orders precautionary measures of protection for victims of oppression and human rights leaders, such as Honduran activist Berta Cáceres (who was the subject of such measures before she was murdered in March).

The commission’s work is now under threat. Despite its reach and mandate, its budget is low (only $9 million in 2015). Funding comes from the OAS budget and voluntary contributions – mainly from the US and European countries. The latter have recently decided to cut funds due to the Syrian refugee crisis, allocating more to programs aimed at assisting those displaced by the ongoing war.

In May of this year, the commission stated that it would lay off 40% of its personnel by the end of July, unless OAS members or international donors could guarantee additional funding. Three days before the deadline, the commission announced it had managed to secure funds from the US, Panamá, Chile, Antigua and Bermuda, to meet salary obligations until the fall. Voluntary contributions (ranging from $1,800 to $150,000) and commitment letters from other member states and the UN were also forthcoming. On September 8, the commission announced new contributions from Mexico and Argentina.

The budget crisis is the latest symptom of the deeper fault line affecting the Inter-American System: the fact that its evolution has not been accompanied by regional political integration or any political consensus. Moreover, during the 2000s alternative regional blocs, such as Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), emerged as organizations in competition with the OAS. The case of UNASUR is telling, since it explicitly endorses the sovereignty of the state over other considerations. Regional governments discussed creating a forum on human rights within UNASUR, one that would prioritize state representation instead of a mechanism integrated by independent experts.

In the absence of regional polity, The American Convention (to which members of the OAS are signatories) is difficult to enforce and the subject of realpolitik. This might explain why compliance with the Inter-American System’s decisions is so poor, and why big players, such as Mexico, are excluded from the organization’s annual report ‘black list’ despite their alarming human rights records. As former commissioner Robert Goldman put it, “If the region’s human rights system is to be fully effective, then member states of the OAS must take seriously their role as the collective and ultimate guarantors of the system’s integrity.”

From Brazil to Ecuador, member states are less tolerant of the commission’s criticism. The case of Venezuela, a long-time supporter of the Inter-American System, is perhaps the most extreme. In 2012 it denounced the American Convention and announced its withdrawal from the jurisdiction of the court, after being subject to an extensive country report by the commission titled “Democracy and Human Rights in Venezuela.”

The increasing number of complaints and precautionary measures received annually by the commission – in particular from Mexico and the Northern Triangle – are signs of a declining and often perilous human rights environment. In the 1990s, a caseload of 600 per year was considered a record; in the early 2000s this was routine. In 2015, a record 2,164 petitions and 564 precautionary measures were received by the commission.

The commission’s financial crisis puts its work further at risk: less budget resulting in more delays in cases being processed and referred to the court, fewer country visits and fewer reports. Ultimately these challenges will deeply impact its overall legitimacy. Along with monetary commitments, a regional consensus on the role of the commission needs to be urgently reached – one that puts citizens, not sovereignty and geopolitics, at the center.

September 26, 2016

Policing black women’s hair

Angela Davis meets Zulaikha Patel, the student at the lead of the protests at Pretoria Girls High. Image credit Leila Dee Dougan.

Angela Davis meets Zulaikha Patel, the student at the lead of the protests at Pretoria Girls High. Image credit Leila Dee Dougan.The thickness and texture of my black hair was under constant scrutiny when I was a child. My aunt used to call me bossiekop (from the Afrikaans, meaning bushy head). The kids at school would use terms like Goema hare (candyfloss hair) and kroeskop (fuzzy head). My cousin would joke: “You can’t even put a comb through your hair.”

Black women’s hair was big news in South Africa earlier this month as protests at South African schools across the country saw brave young women stand up against racist policies in the various ‘codes of conduct’ enforced in their places of learning. The demonstrations at middle class, Model C (former whites-only public) schools like Pretoria Girls High, Sans Souci in Cape Town and Lawson Girls High School in Nelson Mandela Bay – all schools where the students are mostly black and the teachers mostly white – were about much much more than hair, but these protests spoke to our roots as a site of struggle, and a route for resistance.

The policing of black hair often begins at a very young age, in the most subtle and intimate spaces, long before you get to school. I hated when my mother “did” my hair. From a young age I knew the hairdryer wasn’t hot enough and the rollers not tight enough to tame my curls. I knew the brush she was using would never leave me with hair straight enough to flick back, or cut a fringe.

My sister and I would sit between my mothers legs. Her on the couch, us taking turns on the pillow at her feet. Armed with a hairdryer and a brush she would pull and tug at our scalps, trying her best to get it “manageable.” My hair would turn out big. Just big. A huge soft afro that was long enough to tie back for school, but nowhere near “tame” enough to delicately shake off the shoulder.

When my mother was done with my hair I would stand in front of the mirror in the room I shared with my older sister, look at my reflection, and cry. I felt so ugly and so helpless with my afro. I knew that my mother could never make me look like the white women in the shampoo adverts. It was only the aunties at the hairdresser who had all the right tools to “fix” my locks.

I have more memories of the hairdresser down the road than I do of nursery school. I must have been as young as five when the women with the dye-stained apron, hair clips gripped to the bottom of her t-shirt, would stack white plastic chairs at the basin so that my head could reach the sink. My neck would ache in the basin dent, the water would always be either too hot, or too cold and the hairdressers’ vigorous shampoo scrubbing would make me dizzy. The rollers were always too tight, the hair pins would be jabbed into my tender, young scalp and the hour sitting under the hot dryer felt like a lifetime.

No one understands the phrase “pain is beauty” like a young black girl who has just been to the hairdresser. And after all that pain I would indeed feel beautiful. I had long, straight hair that I could leave loose, flick and comb through. But it was temporary. My hair would “last” for a mere two days, more specifically, my hair would “last” until school swimming lessons on a Wednesday.

Throughout primary and high school, the code of conduct stated that hair should be “neat,” and is just one example of the many way these institutions, which have their own roots firmly growing from our colonial history, govern not only children but also parents. The outdated and outright racist rules were something our parents tolerated during term time, but over school holidays our curls were left to grow.

Summer holidays would be spent at my cousins house in Atlantis, about an hour from downtown Cape Town. They had a caravan, a massive garden and a huge swimming pool (our favorite). We would swim until our feet and fingers turned rubbery. Our eyes would turn blood red from the chlorine, and we would lie belly-down on the hot bricks to warm our shaking bodies before jumping back in to the freezing cold water. Those were days of Kreol chips, fizzers and two-rand coins pushed into your palm by an adoring aunty or uncle for a Double O soft drink. Bompies (frozen juice) and sugary bunnylicks (ice lollies) would leave your tongue rainbow green, red or orange. But most importantly, they were days of afros, when parents rarely fought the tangles (there was really no point considering we spent most of our time in the pool) and left our hair to it’s natural state because there was no “code of conduct,” no threat of punishment.

The joy of swimming, and bunnylicks and afros was limited to school holidays. During term time swimming would more often than not be followed by tears. I recall my aunt sitting on the edge of the bath and pulling at my cousin’s long, mousy-brown hair as she sat in a tub of amateur alchemy. Everything from whiskey to egg was sworn by to nourish and soften. Half-used jars and tubs of the latest conditioners, oils and moisturizers would line the windowsill above the bath like ammo, a site of battle between mother, and daughter’s curls, all for the sake of looking “neat.”

My white friends hair always looked neat and they didn’t know the amount of time it took, or the pain I had to endure to get my hair looking like theirs. They would plait each others thin, blonde strands while I looked on with envy. After swimming their hair would dry “perfectly” whereas any form of humidity or moisture was my nemesis. Anything from shower steam to a light mist was enough to provide extreme levels of anxiety about whether my hair would “mince” or “go home.”

By that point my curls were long internalized as a mark of shame, and what I was expressing on the outside had much to do with how my hair was managed within the home and at school. A prime example was weekend family gatherings. You see, in my family, Sunday lunch would always be followed by “Sunday hair” in order to get ready for the week ahead.

As the aunties washed the dishes and the uncles read their newspapers waiting for tea at five (I shake my head thinking about the gender norms enforced through mundane family rituals, but that’s for another time), the cousins (all girls), had our own rituals. Relaxer would be followed by curlers, blow drying and a swirlkouse, which would leave the room hot, and smelling like product and burnt hair.

With the money I earned from my first job, for instance, I bought a large hairdryer, rollers and an assortment of round brushes and as a teenager I saw these tools as allies. It was only at university that I threw them all out.

Reuniting with my curls was less a conscious decision to rebel against the system of whiteness that taught me self-hate, and more about being free from the pain of curlers, the dizzying heat from the hairdryer and the hours spent fighting what naturally grew from my head (I would “blow out” my hair almost three times a week, it would take as long as three hours a time).

But of course you’re not free from the arrogance of whiteness once you’ve taken this route. Since going natural I’ve had numerous instances of my hair being touched, patted and pulled at by strangers (mostly white women), who’ve called it “exotic,” have compared it to a pineapple and referred to it as “surprisingly soft.” Hairdressers tell me that they don’t do “ethnic hair” and an Australian tourist once grabbed onto my curls and said “It’s like a sheep” before turning to her husband to say “go on, touch it, she won’t mind.”

To this very day, my grandfather will pass comments before the Rooibos tea has even been poured “Leila, what’s happening to your hair, why don’t you brush your hair?” Why is black hair such a threat?

Thinking back to those Sunday hair sessions, above the hum of the portable hairdryer, we laughed, we shared secrets, we gossiped, we spent time. Isn’t that the real beauty when it comes to black women’s hair? The ritual between sisters, mothers and daughters, spending time and passing down knowledge. Why were we not styling afros and dreads, why not twists and braids, cornrows and locs?

Every black woman has their own stories about their hair, their curls and societies endless need to tame, manage and straighten whether at school, in the home, or both. But the young black women who used their natural hair as a form of protest this month have clearly stated that they will no longer tolerate the racist frameworks, formal and informal, that teach them self-hate.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers