Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 307

May 2, 2016

Malick Sidibé–Directing Light

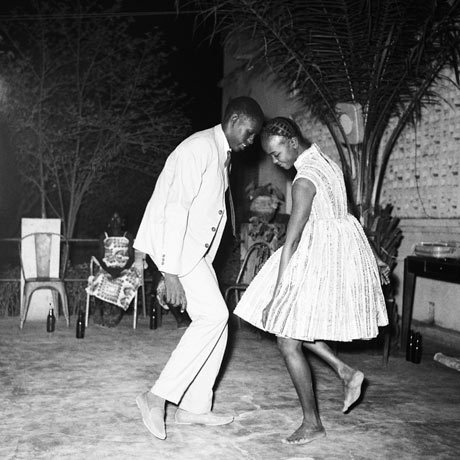

Legendary Malian photographer Malick Sidibé passed away on April 14. Immediately following his death, we published a short tribute by the writer and photographer, Teju Cole. Since then we have reached out to friends and colleagues to reflect on the myriad ways Sidibé directed light in his lifetime – in and outside his camera.

Amy Sall: Malick Sidibé was one of the greatest, pioneering African visionaries to push against Western subjectivity, forging a space for African autonomy and agency to be recognized by the masses. His work shone a beautiful and important light on the robust youth culture, sartorial prowess and rich daily lives in Mali. Whereas Western entities saw Africans as one-dimensional, and developed warped theoretical constructions on who we were, Sidibé fought against such ignorance by simply showing the world who we were, in all of our nuanced glory. We are forever indebted to the Eye of Bamako.

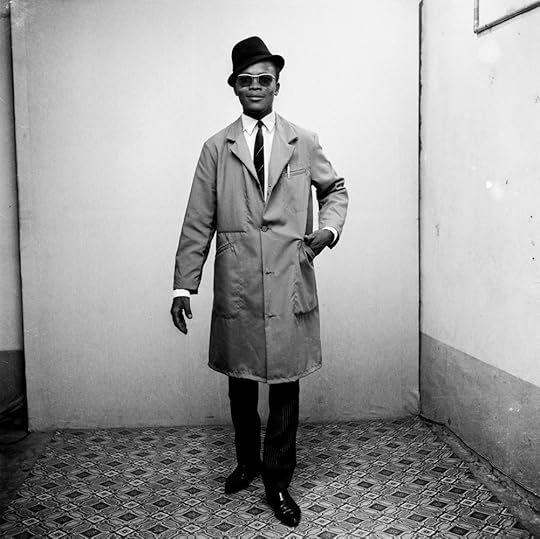

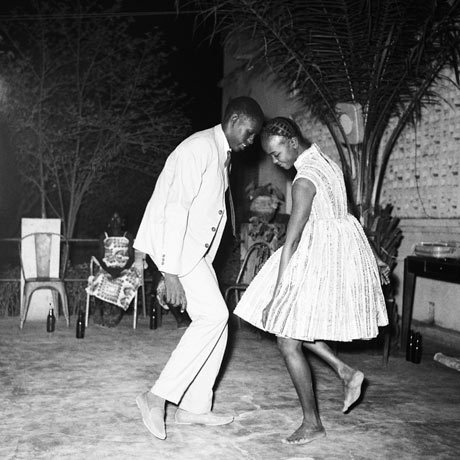

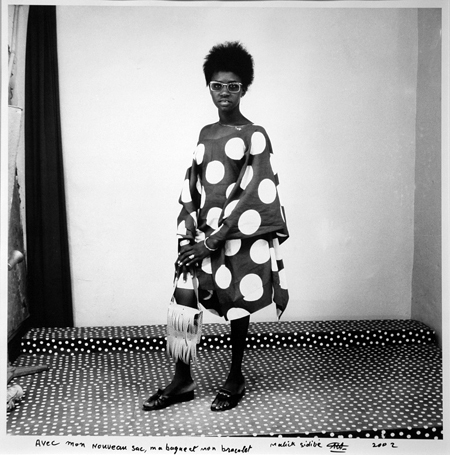

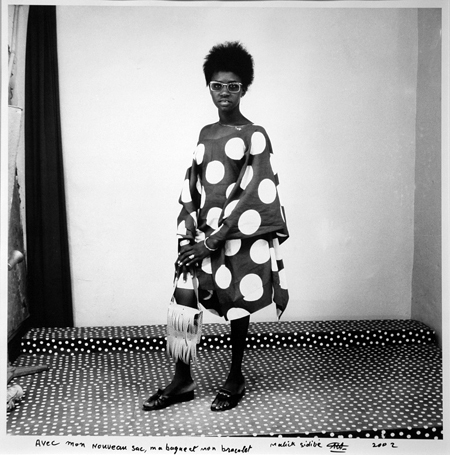

Candace Keller: Malick Sidibé was arguably one of the most influential photographers of our time. Most renowned in international art circles for dynamically composed black and white studio portraits and photographs taken of youth at parties and celebratory events in Bamako, during the 1960s and 1970s, Sidibé’s images have inspired numerous fashion designers, photographers, videographers, and filmmakers around the globe. Accordingly, in the past two decades, Sidibé was commissioned to take fashion photographs for magazines such as Vogue, Elle, Cosmopolitan, Paper, and the New York Times Magazine.

In Mali, Sidibé was the patron saint of photography. For much of his career, he was one of few people in the country who could repair medium format and 35mm film cameras. As a result, Studio Malick became a nexus for photographers. Over time, his studio acquired a large collection of cameras, which he regularly gifted to young men and women aspiring to enter the profession. Later in his career, he facilitated several photographic workshops, training future generations, and as the president of the Groupement National des Photographes Professionels du Mali advocated on behalf of the trade and its practitioners at the National Assembly.

Those who knew him admired his generous, humble spirit, jovial sense of humor, and philanthropic endeavors. For his 21st-century fashion shoots and Vues de dos (Back Views) series, he hired single mothers and orphans from his neighborhood to serve as models, providing them with communal support and a source of income. For decades, as he noticed passersby or was reminded of someone who had recently or long since passed, he would find their portrait in his archives and reprint it for their family – unsolicited – as a memento. As president of his hometown association, he helped provide support for the construction and renovation of schools, roads, and other community resources for his village, Soloba.

Over the past 15 years, as I have studied the history of photographic practice in Mali, spending hours in his studio, darkroom, and home, Malick has remained one of my greatest teachers and an inspiration for what it means to be a good person, neighbor, and friend. Sobekela de don! His legacy lives on in the hearts and minds of those he touched. May he forever rest in peace.

Drew Thompson: Malick Sidibé’s practice flourished outside of the commercial studio, where he initially trained as a photographer. The poses and dress styles of his photographed subjects mirrored the processes of globalization that accompanied the end of French colonial rule in Mali. In fact, his photographs illustrate the material worlds inhabited by his photographed subjects and the forms of appropriation that characterized the presence of diverse technologies like cars, radios, and clocks. Sidibé’s physical movements with the camera blur the boundaries that distinguish social, professional, and political spaces, and as a consequence display the ways in which photography’s practice and acts of looking were fundamental to Malian daily life.

Sidibé humanizes his unidentified subjects through the lenses of fashion, leisure, and romance, and his use of the camera and the prints that resulted prompt a rethinking of popular culture’s role in processes of colonization and decolonization. Furthermore, his pictures were formative to the creation of Recontres de Bamako, the major photography biennial, and the curatorial endeavors of Okwui Enwezor – both of which have transformed the public’s engagement with and study of photographers from the continent of Africa. Sidibé’s photographs represent a distant memory when compared to recent historical events in Mali. In fact, insurgency movements have used the representational contents of and symbolic value embodied by Sidibé’s practice and photographs to challenge political rule and to unsettle state boundaries. What then are captivated viewers to do with such mesmerizing prints and an illustrious professional legacy, especially when the photographer is no longer living and when geopolitical circumstances render the contents of photographic prints as artifacts of the past? Sidibé’s death presents such questions while providing few, if any, answers.

Thato Mogotsi: Upon hearing of the passing of Malick Sidibé ‘The Eye of Bamako’, my initial reaction was one of both sadness and regret. I will never have the opportunity to meet him, to visit him at his world famous studio.

Seeing several artists I knew post portraits on social media, taken in front of one of his recognizable backdrops, or posing with the great man himself, I couldn’t help but feel a pang of narcissistic envy. The visit to Sidibé’s studio, it seemed to me, was considered a kind of art world pilgrimage, one that often coincided with a visit to the long running and ever crucial Recontres de Bamako Biennale.

But then I recalled how seminal Sidibé’s work was for me in my years as a student of photography. It had indeed opened up a whole new way of reading the imaged black body. The weight and density of his extensive archive, gave incredible validity to my understanding of how one might attempt to encapsulate the lived experience of blackness through the language of photography. Sidibé’s work is evidentiary of how, as black artists, there is an innate responsibility we bear — to claim and uphold the visibility of our communities and our imaged self in a world that systemically attempts to diminish or even appropriate it.

We can only hope that future generations will stand to inherit from Sidibe’s legacy, this empowered sense of visual literacy that transcends a cerebral response to photography as a mere technical tool. I remain grateful for the many ways in which his work illuminated my young creative journey, even from afar.

Cherif Keita: Malick Sidibé, the man who lived several lives, has left to join his elder colleague Seydou Keïta, in the land of immortality. What an abundant legacy he has left to posterity.

It was in 2010 that I had the unique opportunity of meeting this father of African Photography. One January afternoon I arrived at his studio in the populous neighborhood of Bagadadji, with 21 American students in tow. Smiles, wide-open arms and loud greetings! It was as if Malick had known each of us in the not too distant past. Truly, we had arrived home, at his studio.

Cherif Keita and his friend Toure, photographed by Malick Sidibé in Bamako in 2010.

Cherif Keita and his friend Toure, photographed by Malick Sidibé in Bamako in 2010.Our conversations over his numerous photo albums were a unique moment for me, the Malian exile, as well as for the young Americans, freshly arrived in Mali, as part of a study trip, with the theme of Malian history and culture. Each photo spoke volumes about a feverish period of my own youth in Bamako, on the eve of the military coup of 1968. My students had finally under their eyes the vibrant social landscape I had tried my best to paint for them in my classes on the other side of the Atlantic.

After spending a good hour traveling through time, Malick told us that it was time to stand in front of his camera. In general, for Malick, it was a matter of simply catching the joyful moment that we were sharing that afternoon. Such was his overall artistic philosophy.

The last time I saw Malick was in June 2015. Not having found him at the studio, I went to his house in Magnambougou, because I had for him a signed copy of a book written by my friend, Professor Tsitsi Jaji, with one of Malick’s photos on the cover. Even though he was ill and weakened by old age, he had not lost his legendary smile. Very quickly, some albums came out, which we had to vigorously dust off before going through them. They are right, those who say that the world has seen only a small fraction of the thousands of photos taken by this tireless photographer.

Cherif Keita viewing photo album with Malick Sidibé.

Cherif Keita viewing photo album with Malick Sidibé.It is said that when Photography was first introduced in Mali and elsewhere in Africa, people were afraid of it, because in the Bamana language, for instance, it was considered a dangerous act: jà tàa meant to take the soul or the shadow of the person who was being photographed. Going from that to Mali becoming the capital of Photography in Africa, clearly we all owe a debt of gratitude to Malick Sidibé – with his mild manners and disarming smile – for having convinced tens of thousands of people to entrust their souls or shadows to a black hand holding a shiny little box that produced a blinding light. Rest in Peace, Malick, illustrious son of the village of Soloba, in Wassulu.

Amy Sall is the editor of Sunu Journal. Candace Keller is an associate professor at Michigan State University. Drew Thompson is a visual historian. Thato Mogotsi is an independent curator based in Johannesburg. Cherif Keita, born in Mali, is a documentary filmmaker and professor of French and liberal arts at Carleton College in Minnesota.

Malick Sidibé: Directing Light

Legendary Malian photographer Malick Sidibé passed away on April 14. Immediately following his death, we published a short tribute by the writer and photographer, Teju Cole. Since then we have reached out to friends and colleagues to reflect on the myriad ways Sidibé directed light in his lifetime – in and outside his camera.

Amy Sall: Malick Sidibé was one of the greatest, pioneering African visionaries to push against Western subjectivity, forging a space for African autonomy and agency to be recognized by the masses. His work shone a beautiful and important light on the robust youth culture, sartorial prowess and rich daily lives in Mali. Whereas Western entities saw Africans as one-dimensional, and developed warped theoretical constructions on who we were, Sidibé fought against such ignorance by simply showing the world who we were, in all of our nuanced glory. We are forever indebted to the Eye of Bamako. [Amy Sall is a photographer and the editor of Sunu Journal.]

Candace Keller: Malick Sidibé was arguably one of the most influential photographers of our time. Most renowned in international art circles for dynamically composed black and white studio portraits and photographs taken of youth at parties and celebratory events in Bamako, during the 1960s and 1970s, Sidibé’s images have inspired numerous fashion designers, photographers, videographers, and filmmakers around the globe. Accordingly, in the past two decades, Sidibé was commissioned to take fashion photographs for magazines such as Vogue, Elle, Cosmopolitan, Paper, and the New York Times Magazine.

In Mali, Sidibé was the patron saint of photography. For much of his career, he was one of few people in the country who could repair medium format and 35mm film cameras. As a result, Studio Malick became a nexus for photographers. Over time, his studio acquired a large collection of cameras, which he regularly gifted to young men and women aspiring to enter the profession. Later in his career, he facilitated several photographic workshops, training future generations, and as the president of the Groupement National des Photographes Professionels du Mali advocated on behalf of the trade and its practitioners at the National Assembly.

Those who knew him admired his generous, humble spirit, jovial sense of humor, and philanthropic endeavors. For his 21st-century fashion shoots and Vues de dos (Back Views) series, he hired single mothers and orphans from his neighborhood to serve as models, providing them with communal support and a source of income. For decades, as he noticed passersby or was reminded of someone who had recently or long since passed, he would find their portrait in his archives and reprint it for their family – unsolicited – as a memento. As president of his hometown association, he helped provide support for the construction and renovation of schools, roads, and other community resources for his village, Soloba.

Over the past 15 years, as I have studied the history of photographic practice in Mali, spending hours in his studio, darkroom, and home, Malick has remained one of my greatest teachers and an inspiration for what it means to be a good person, neighbor, and friend. Sobekela de don! His legacy lives on in the hearts and minds of those he touched. May he forever rest in peace. [Candace Keller is an associate professor at Michigan State University.]

Drew Thompson: Malick Sidibé’s practice flourished outside of the commercial studio, where he initially trained as a photographer. The poses and dress styles of his photographed subjects mirrored the processes of globalization that accompanied the end of French colonial rule in Mali. In fact, his photographs illustrate the material worlds inhabited by his photographed subjects and the forms of appropriation that characterized the presence of diverse technologies like cars, radios, and clocks. Sidibé’s physical movements with the camera blur the boundaries that distinguish social, professional, and political spaces, and as a consequence display the ways in which photography’s practice and acts of looking were fundamental to Malian daily life.

Sidibé humanizes his unidentified subjects through the lenses of fashion, leisure, and romance, and his use of the camera and the prints that resulted prompt a rethinking of popular culture’s role in processes of colonization and decolonization. Furthermore, his pictures were formative to the creation of Recontres de Bamako, the major photography biennial, and the curatorial endeavors of Okwui Enwezor – both of which have transformed the public’s engagement with and study of photographers from the continent of Africa. Sidibé’s photographs represent a distant memory when compared to recent historical events in Mali. In fact, insurgency movements have used the representational contents of and symbolic value embodied by Sidibé’s practice and photographs to challenge political rule and to unsettle state boundaries. What then are captivated viewers to do with such mesmerizing prints and an illustrious professional legacy, especially when the photographer is no longer living and when geopolitical circumstances render the contents of photographic prints as artifacts of the past? Sidibé’s death presents such questions while providing few, if any, answers. [Drew Thompson is a visual historian.]

Cherif Keita: Malick Sidibé, the man who lived several lives, has left to join his elder colleague Seydou Keïta, in the land of immortality. What an abundant legacy he has left to posterity.

It was in 2010 that I had the unique opportunity of meeting this father of African Photography. One January afternoon I arrived at his studio in the populous neighborhood of Bagadadji, with 21 American students in tow. Smiles, wide-open arms and loud greetings! It was as if Malick had known each of us in the not too distant past. Truly, we had arrived home, at his studio.

Cherif Keita and his friend Toure, photographed by Malick Sidibé in Bamako in 2010.

Cherif Keita and his friend Toure, photographed by Malick Sidibé in Bamako in 2010.Our conversations over his numerous photo albums were a unique moment for me, the Malian exile, as well as for the young Americans, freshly arrived in Mali, as part of a study trip, with the theme of Malian history and culture. Each photo spoke volumes about a feverish period of my own youth in Bamako, on the eve of the military coup of 1968. My students had finally under their eyes the vibrant social landscape I had tried my best to paint for them in my classes on the other side of the Atlantic.

After spending a good hour traveling through time, Malick told us that it was time to stand in front of his camera. In general, for Malick, it was a matter of simply catching the joyful moment that we were sharing that afternoon. Such was his overall artistic philosophy.

The last time I saw Malick was in June 2015. Not having found him at the studio, I went to his house in Magnambougou, because I had for him a signed copy of a book written by my friend, Professor Tsitsi Jaji, with one of Malick’s photos on the cover. Even though he was ill and weakened by old age, he had not lost his legendary smile. Very quickly, some albums came out, which we had to vigorously dust off before going through them. They are right, those who say that the world has seen only a small fraction of the thousands of photos taken by this tireless photographer.

Cherif Keita viewing photo album with Malick Sidibé.

Cherif Keita viewing photo album with Malick Sidibé.It is said that when Photography was first introduced in Mali and elsewhere in Africa, people were afraid of it, because in the Bamana language, for instance, it was considered a dangerous act: jà tàa meant to take the soul or the shadow of the person who was being photographed. Going from that to Mali becoming the capital of Photography in Africa, clearly we all owe a debt of gratitude to Malick Sidibé – with his mild manners and disarming smile – for having convinced tens of thousands of people to entrust their souls or shadows to a black hand holding a shiny little box that produced a blinding light. Rest in Peace, Malick, illustrious son of the village of Soloba, in Wassulu. [Cherif Keita, born in Mali, is a documentary filmmaker and professor of French and liberal arts at Carleton College in Minnesota.]

May 1, 2016

The Ghost of the IMF’s Past

It’s May Day today, but we still have some work to do. To the coalface we go.

Is the ghost of the IMF’s past back to haunt Africa? It seems these days that no economic news item about the continent is complete without some reference to “The Fund.” So we kick things off with a story about the IMF’s latest tussle with the government of Mozambique.

(1) It was revealed this past April that Mozambique, previously the IMF’s poster child for a “new Africa”, had not disclosed about US$1 billion worth of debt to the Fund. The Mozambican government maintains it didn’t see the need to disclose the debt because it was contracted to protect the country’s “strategic infrastructure.” For instance, about half of the previously undisclosed amount is said to have been contracted by Pro-Indicus, established by the state in 2012 to protect the country’s newly discovered oil and gas reserves.

Whatever the reasons for the non-disclosure, the IMF’s upset and has since suspended additional lending to Mozambique setting off a chain reaction of similar actions by the World Bank and the UK government.

(2) Still on news about the IMF and Africa: the South African Mail and Guardian wins our headline of the week competition with this: “After fighting hard, Zambia expected to stumble into the IMF’s waiting arms”. Notice that the headline says nothing about those arms being loving arms.

(3) Sticking with Zambia, we came across this paragraph showcasing the dubious promise of privatization and so-called “tax incentives”:

Unfortunately, when [Zambia’s copper] mines were privatized in the 1990s, [at the behest of the IMF, World Bank and other donors] investors in the sector were offered very attractive tax incentives that shielded them from paying higher taxes as the copper prices rose. As a consequence, despite copper making up more than 70% of total exports, the contribution to tax revenues is relatively small compared with other countries. In 1992, when the mines were owned by the state and copper prices averaged $2,280 per ton and production was 400,000 tons, the government was able to collect $200million in revenues and other remittances. In 2004, when the mines [had been privatized] and the copper prices had risen to $2,868 and copper production was 400,000, the government only received about $7million in revenues.

It’s from page 9 of the two-year old study “Zambia: Building Prosperity from Resource Wealth.”

(4) This type of economics that unambiguously promises magical things to appear out of lower corporate taxes and privatization has rightfully been called “voodoo economics.” And we are happy to learn there is now growing opposition to it among the younger generation, like the former New York Times economics reporter Catherine Rampall (now an opinion writer at the Washington Post):

Just 35 percent of respondents [inthe latest youth poll from Harvard’s Institute of Politics] said they agreed with the statement that tax cuts are an effective way to increase growth, which is 5 percentage points lower than last year and the lowest share since the poll first asked a question with this phrasing. This is bad news for Republican candidates, all of whose economic policies are predicated on very generous assumptions about tax cuts and growth.

(5) Talking about voodoo economics, it appears that economists are willing to sacrifice more than half a thumb to publish in the American Economic Review, the profession’s most prestigious scholarly outlet. True story.

(6) One of our favorite economists Dani Rodrik has a really illuminating piece dispelling the myth that protective trade barriers in advanced countries (as advocated for by, for instance, U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders) spell doom for the world’s poor. Professor Rodrik dispenses with the myth not by making things up but by appealing to the actual historical record:

[T]here is nothing in the historical record to suggest that poor countries require very low or zero [trade] barriers in the advanced economies in order to benefit greatly from globalization. In fact, the most phenomenal export-oriented growth experiences to date – Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and China – all occurred when import tariffs in the US and Europe were at moderate levels, and higher than where they are today.

(7) And Professor Rodrik blessed us twice this week by publishing a piece challenging the promise of so-called structural reform – the kind of reform agenda inflicted on Africa in the 80s and 90s. Here’s a sample:

But the [structural reform] policy prescribers, it seems, suffer from selective memory. Structural reform as a remedy for slow (or no) growth has been around at least since the early 1980s. At that time, the World Bank began to insist on economywide liberalizing reforms as the quid pro quo for developing countries in Asia, Africa and the Middle East in return for “structural adjustment loans”…Oddly, though, debate over the reforms pressed on Greece and other crisis-battered countries in the periphery of Europe did not benefit from lessons learned in these other settings. A serious look at the vast experience with privatization, deregulation and liberalization since the 1980s would have produced much less optimism about the benefits of the kinds of reforms Athens was asked to impose.

(8) We found this much retweeted piece by The Economist on the challenges of manufacturing in Africa confusing to read (we weren’t surprised, actually). The piece subtly manages to re-manufacture (no pun intended) the trope that Africans are incapable of doing anything because they are corrupt and so on. The piece rightfully acknowledges that the continent was more industrialized in the 1970s than it is today but (purposely?) neglects to point out that the reasons for de-industrialization over the last 30 years are largely ideological. For instance, much of the continent began to de-industrialize long before the energy crisis that’s currently afflicting it. Whereas the energy crisis is a constraint on industrialization today, The Economist doesn’t explain why de-industrialization happened in the first place. We’ve written before about this type of historical amnesia when it comes to the debate about Africa and industrialization here and here.

(9) Finally, the good team at Zikoko Magazine have put together this useful list of steps needed to start “a successful Nigerian Church Business.” It’s no joke oh. Times are hard and we all have to make a living somehow.

April 29, 2016

Weekend Music Break No.94

A break from the routine of the work week, a weekend music break for you all to enjoy this May Day!

Rest in peace Papa Wemba 2) Netherlands-based Cape Verdean singer Gery Mendes asks if our world is really ready for positive change, is it? 3) I’m in the UK right now, so I had to share Stormzy’s latest. 4) London Global Hip Hop outfit Subculture Sage’s video for “Gold” stars two Zimbabwean gold miners. 5) There’s an H&M in Brixton now. (M.I.A. invites AIAC profile subject Dope Saint Jude along for her collaboration with the brand.) 6) Sean Jacobs spotted this, trap rap video from Northern Nigeria. 7) I’ve noted Kahli Abdu as one to watch for awhile, and he did not disappoint with this banger! 8) The Mavin Records crew out of Nigeria dropped a new one this week. 9) I don’t know much about them, but Chloe and Halle are interesting. 10) And finally, a new Azaelia Banks video just for the hell of it.

Happy weekend!

April 28, 2016

Egypt’s Modern Pharaohs

Except for a brief one-year interlude from June 2012 to July 2013—when Mohamed Morsi was President—modern Egypt has been ruled by military regimes. It began with Gamal Abdel Nasser (1956-1970), who came to power through a military coup. Nasser was succeeded by Anwar al Sadat (1970-1981) at Nasser’s death. When Sadat was assassinated, his deputy Hosni Mubarak took over until the protests of January 2011. When Morsi — Egypt’s first and only democratically elected President — was deposed, another General, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, took power. Sisi, who is currently Egypt’s President, declared in February 2015 that the country’s democratic transition “is complete.”

In a way, Egypt’s military dictators came to resemble its pharaohs, with their highly centralized governments, the creation of a culture of fear, and a cult of personality. In modern Egypt, the portrait of the president hangs in every government office, on billboards throughout the cities and on the sides of roads. Buildings and neighborhood are named for them.

Egyptian filmmaker Jihan el Tahri explores this recent history in a new, three part documentary series, Egypt’s Modern Pharaohs. The series has been screened on the BBC, Arte and at major film festivals. Each part focuses separately on the Nasser, Sadat and Mubarak regimes, who combined ruled Egypt for over 50 years.

The series begins with the accession of Nasser through his coordination of coup by “Free Officers” in 1952 against King Farouk. Nasser, however, did not become Egypt’s first republican president. That honor went to Muhammad Naguib, who was born in Sudan. Within one year Nasser, using his popularity, plotted against Naguib, imprisoning him as well as, subsequently, erasing all traces of Naguib’s contributions to the revolution from public memory.

Sadat, who served as Nasser’s vice president, used his time at the helm to undo much of what Nasser had built. Nasser worked hard to unite much of the Arab world under his leadership — he is credited as the father of Pan-Arabism– but also remembered involving Egypt in costly and disastrous wars in Yemen and with Israel.

Under Sadat, Egypt signed a peace deal with Israel (Sadat visited Israel and spoke in the Israeli parliament, the Knesset) that isolated Egypt politically for at least decade. Sadat also negotiated with the West and opened up the Egyptian economy to western investment.

Hosni Mubarak took up where Sadat left off in his devotion to capitalism and western, especially U.S., political influence. The 30-year rule of Mubarak was defined by the growth of income inequalities and dismantling of the social safety nets that Nasser had put in place. Corruption ran wild throughout the country and the military consolidated its stake over the economy. The only state sector that functioned effectively, was the security apparatus. Forced disappearances, human rights abuses, and extreme police brutality were all widespread during the Mubarak regime.

One aspect of military rule that has remained relatively unexplored until recently, is its relationship to political Islam, which has always garnered large followings of devoted members among ordinary Egyptians. The Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist groups have been in and around Egyptian politics since the early 1920s and the government’s best efforts to weaken them notwithstanding, they always reemerged stronger.

Publicly, Egypt’s military regimes play up their opposition to Islamists, but enjoyed symbiotic relationships between successive Egyptian governments and Islamist groups. In Egypt’s Modern Pharaohs, El Tahri explores this rarely acknowledged mutually beneficial relationship.

Nasser, for example, exploited his relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood to gather popular support for the 1952 coup. Once he had stabilized his dominance over Egypt, he criminalized and imprisoned Muslim Brothers, including prominent Islamic theorist Sayyid Qutb. Sadat eased the grip on political Islam and actively encouraged Wahabism. Sadat’s strategy was to co-opt them so as to neutralize radical Islamists. However, the Islamists would eventually assassinate Sadat. The Mubarak regime then changed course and cracked down on political Islam. Mubarak later changed his mind and allowed the Muslim Brotherhood to participate in parliamentary elections in the early 2000s as independent candidates. The Brothers won several seats and provided a serious opposition to the ruling National Democratic Party.

El Tahri manages to interview all of the major players that were part of the drama of the last 50 years of Egyptian politics. Embers of the ruling party, the Free Officer Movement, 1970s student leaders and leaders of Islamist groups, all get their turn on camera. It’s rare to hear such candor about Egyptian political history and the film does a great job of situating the viewer into the political culture of the time.

My family is Egyptian — my parents migrated to the United States in the early 1980s — and I was brought up with the idea that these central figures in modern Egypt were infallible men of honor and patriotism. This series destroys that illusion. Instead they were characterized by political failure, deceit, corruption and greed.

To get her viewpoint across, El Tahri uses traditional storytelling techniques. At the center of the film are interviews mixed with found footage of historical significance. To add cultural depth to the narrative, she complements these with clips from classic Egyptian films and television shows that depict significant events in history. This is of course vintage El Tahri, whose films add up to an alternative history of “Third Worldism” (see for example her brilliant films on Cuba’s African solidarity campaigns or post-apartheid South African politics).

Egypt’s Modern Pharaohs was funded by a grant through the Doha Film Institute (DFI) in Qatar. Headed by Sheikha Al-Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani, the sister of Qatar’s ruling Emir, DFI is another tool of Qatar’s soft power in the region, which includes the Qatar Foundation, hosting the 2022 World Cup or welcoming many global political and economic summits. Through funding and influence in media, arts, sports, and education, Qatar has worked hard to elevate its political status in the Middle East and globally. Qatar was also a vocal supporter of the Arab Spring. As a result, the military and nationalists in Egypt accuse Qatar of aiding the Brotherhood. After President Morsi was overthrown, Egyptian relations with Qatar deteriorated, with the generals preferring Qatar’s rival Saudi Arabia. The Egyptian military viewed the local bureau of the Qatari public diplomacy broadcaster Al Jazeera as a fifth column for Morsi and the Brotherhood. After he came to power, Sisi closed down Al Jazeera’s office and jailed some of its reporters. Within Egypt, where conspiracy theories are commonplace, the sponsorship of El Tahri’s film by a Qatari foundation will thus arouse suspicion and debate, but that is a red herring. The film has to be judged on its merits.

Wither the Left in Nigeria?

Most contemporary observers of Nigerian politics would be surprised to learn that the Left has been a significant part of the country’s postcolonial history.

Nowadays, the Left includes various groups, ranging from NGOs to pro-democracy and anti-government groups, but my use of the term is restricted to a particular historical process that shaped the establishment, formation and cooperation of different organizations with allegiance to a Marxism-Leninist forms of political economy in post-colonial Nigeria.

Nigeria’s political independence is often credited to nationalist leaders, such as Chief Obafemi Awolowo, Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe and Sir Ahmadu Bello. In the process, commentators minimize the heroic role played by the Labor movement (led by Chief Imoudu), the Zikist movement (led by Chief Mokwugo Okoye) and other Left organizations.

The general strike of 1945 marked the beginning of the struggle that end in the termination of colonial rule in Nigeria in 1960. The Left remained a power after independence, as well. In 1960 for example, protest against a British request to set up a permanent British military base in Nigeria was organized by leftist students and workers, preventing Nigeria from becoming a military outpost of a dying British empire.

This robust Left tradition would continue from independence through the periods of military rule in Nigeria. However, three events in the late 1980s and early 1990s spelled the fate of the Left in Nigeria.

General Ibrahim Babangida came to power in a military coup in 1985, ousting General Muhammadu Buhari, who had overthrown a short-lived elected government (the same Buhari who is the country’s current democratically elected president). In 1986 Babangida, presenting himself as a reformer, appointed the Cookey Commission to chart Nigeria’s political future. The commission—composed of leading leftists–advocated for, among other things: social justice, a return to democracy, and a socialist state. The military rejected most of the recommendations, particularly the one that proposed transition to a socialist state. Babangida also pushed through an IMF loan that the Left vehemently opposed.

Babangida then intensified his repression of the Left. At Amadu Bello University, the military ordered all Marxist books burned and dismissed professors associated with Marxism, such as Festus Iyayi (University of Benin), Toye Olorode and Idowu Awopteu (both of Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile Ife). Patrick Wilmot (born in Jamaica), who taught at Ahmadu Bello, was deported to the UK.

Yet the Left persisted. In the early 1990s, leftists formed a coalition – the National Consultative Forum – to develop a new constitution, establish an interim government, and a timetable to chart the end of military rule and run elections. When the military responded by arresting coalition leaders at the launch, Leftists regrouped as the Campaign for Democracy. Babangida called for elections to elect a civilian in 1993, then annulled the result; he eventually left office later that year. Unfortunately, his successor Sani Abacha proved even more ruthless. Without a viable path to power, leaders on the left were imprisoned, lost their jobs; over time, many conformed to the neoliberal system instituted by the military regime.

This begs the question: given this history of activism despite the odds, why is the Left invisible in contemporary Nigerian politics? In addition to its confrontations with the state, the Left’s fate has been shaped by internal debates about whether change is best promoted through revolution or liberal democracy. This debate has been polarizing and has allowed political and business elites to consolidate power in the post-military era. Unable to articulate a clear political plan, many erstwhile Leftists have gravitated to limited reform agenda of most NGOs: constructive engagement with the state, as opposed to structural change in the socioeconomic and political life of Nigeria. Working with NGOs has transformed Leftists into state partners, no longer interested in taking power but in sharing it. Non-governmental organizations in Nigeria advocate for surface level change in state practices, rather than radical transformation of the state to popular participatory and people-centric democracy. The NGO invasion of trade unions exemplifies this trend. They are content to have their right to protest price hikes preserved as subsidies drop. The Occupy Nigeria movement met a similar fate. Meanwhile, brilliant organizers die mysteriously: For example, in 2005, Chima Ubani was the victim of a suspicious accident on his way to mobilize one such protest.

Nothing describes the current state of the Left better than the participation of those few who represent it in government. These include: Labaran Maku, who was deputy governor in Nassarawa State and later became former President Goodluck Jonathan’s Information Minister; Kayode Fayemi, who was Governor of Ekiti State and is now Minister of Solid Minerals; and Uche Onyeagocha, who became a member of the House of Representatives (the lower house of the national assembly). All are avowed leftwingers, but rely on a political system whose agenda is dictated by the same elite that have turned Nigeria’s state and public resources into private property.

It is the Left’s reluctance to contest power that has given us the present system. While some of today’s elite were hobnobbing with the brutal Abacha regime, on June 4th, 1998 in Benin City, left leaders such as Ubani, Bamidele Aturu, Emma Ezeazu, Salihu Lukman, Dr. Abayomi Ferreira, Uche Onyeagocha and others from across the country, launched The manifesto and Democratic Alternative accompanied by a manifesto that challenged the Abacha regime. The DA, in alliance with the United Action for Democracy, was later at the forefront of the fight against Abacha. When the latter died in 1998 and the present transition to civilian rule was initiated by the Abdulsalami regime, the Democratic Alternative applied and registered as a fully fledged political party, and at a convention in Port Harcourt later that year, declared to sponsor candidates at all levels for elective office. Their ambitions were foiled, however, by lack of funds, the commercialization of the electoral system and the absence of consensus about the nature of political participation by all Left organizations.

The question is: wither the Left in Nigeria? Can the Left perform its historical role by organizing and reshaping the politics of Nigeria for the good of its citizens? At this critical moment the Left has the opportunity to redeem itself by organizing and re-engaging. The Nigerian people are frustrated by the lack of leadership from elite politicians. They want change, but not the kind of change promised by the Buhari administration. Rather, an alternative vision of what Nigeria might be.

This is the moment for left-leaning political parties to cultivate new alliances, and build consensus around issues that are germane to Nigerians – the comatose economy, education, health and jobs. It is time to break the elite stranglehold on politics and shake off the embrace of the current system. The Left’s finest days are yet to come.

April 26, 2016

The Myth of the African travel writer

Bethnal Green, London. By @Nyathikano

Bethnal Green, London. By @NyathikanoThe proposition that I attend the African Travel Writing Encounters (ATWE) workshop held at the University of Birmingham in the UK on a blustery, drizzly day in March came from a close acquaintance who fits the customary profile of a professional travel writer – meaning that he is white and male. Daniel Metcalfe, my acquaintance, followed his own impulse: he travelled solo around Angola for three months and recorded his discoveries, adventures and experiences in the critically-acclaimed Blue Dahlia, Black Gold: A Journey into Angola, published in 2013.

But the line-up of speakers seemed to have been hand-picked explicitly to shake-up such complacent views as I held prior to arriving at the university’s labyrinthine medical school where the workshop took place. With the exception of University of Sussex graduate student Matthew Lecznar, all the male presenters were black African, and all the white ones were female. And the marathon session (we began at nine in the morning and finished late into happy hour) was brought to a triumphant close by the irrepressible and enormously talented Lola Akinmade Åkerström (a Nigerian, now living in Sweden), whose evocative photography is represented by National Geographic Creative and travel writing has been published in a plethora of national and international media outlets.

In fact, Lola’s presentation was one of only three given by Africans who are practicing travel writers. Fellow Nigerian, Pelu Awofeso was another, and Zambian author Humphrey Nkonde was linked to the meeting by telephone after encountering problems in his bid for a British visa (par for the course when you attempt to ram global travel and Africans into the same frame). Most of the remaining presenters hailed from universities and research institutes in Algeria, Brazil, Ghana, Morocco, Nigeria, and United Kingdom – in other words, they were scholars.

And, given that the racial profile of Britain’s academic staff almost precisely mirrors that of the traditional travel writing cohort, I won’t startle anyone by saying that the UK-based academics in attendance were almost all white. In other words, despite the surprising and exhilarating racial diversity on display, it remained true that, like a Montgomery County magnet school, most of the blacks had been bussed (more accurately, flown) in. And the main reason why this matters is because it highlights an important loop-hole in equality and diversity initiatives in UK higher education that arises from the popular notion of the ‘global university.’ Higher education institutions can buy in diversity through funding for international research projects, conferences, networks and the like, while simultaneously falling short of rectifying glaring racial inequalities locally.

Appropriately enough, one of the first papers, delivered by York university-based researcher Janet Remmington, drew attention to the possibilities for unsettling the status quo inherent in travel that is seen as “without purpose” or “meandering.” Her subject, Sol Plaatje, was at one time described by colonial South African officials as a “political native engaged in peregrinations amounting to travel (my emphasis).”

Despite breaking new ground in several ways, the workshop’s presentations – running the gamut from journeys undertaken by Moroccan ambassadors in the 19th century (Hamza Salih) to Samuel Crowther’s expeditions to the Niger (Alexsander Gebara), and inclusive of the contemporary travel writing showcased by Awofeso and Nkonde – failed to reflect the basic concept of the European archetype: travel undertaken for its own sake. African travelers, it would seem, must still justify their movements across the planet (whether the motives be professional, economic or political). Passports may have replaced passbooks for a number of us; but we must still answer the question, “Why are you here?”

No normal sport in an abnormal society

Recently, Aubrey Bloomfield, a graduate student at The New School, and I wrote a piece for The Nation about a sports boycott as a strategy against the occupation of Palestinian land by Israel. Here’s an excerpt:

There appears to be support among Palestinians generally for sporting sanctions against Israel. However, to date BDS has largely been focused on other targets. In recent years, the cultural boycott has become a growing aspect of the movement. While the success or failure of cultural boycotts is debatable (they have had success up to a point), what the South African case points to perhaps is the greater impact of sports boycotts on political attitudes and reform.

One thing that seems to work well—when international diplomacy and common sense have failed—is the threat of withdrawing a rogue nation from the community of sport. In South Africa the slogan “no normal sport in an abnormal society” encapsulated the conviction that as long as the regime excluded the majority of its people from participating in society as equals, it should be excluded from participating in international sports competitions as equals. For white South Africans (and their apologists), sporting isolation was a bitter pill to swallow.

The Israeli government and sports associations’ responses to recent threats of Israeli expulsion from UEFA and FIFA are particularly instructive: Citizens have strong feelings about sport. It is closely tied to national identity, and the symbolic effects of sporting sanctions are more palpable than economic sanctions may be for many citizens (in the way, say, that being denied access to certain commodities may not be).

Up to now, BDS has been largely ambivalent about a sports boycott. Nevertheless, experience has shown that sports boycotts are very powerful tools for international solidarity groups. Ultimately, they could prove crucial in the Palestinian case, forcing a much broader conversation about the Israeli occupation and potentially representing one of the most significant threats yet to the status quo.

April 23, 2016

Shadow and Axed

As promised, here’s the latest instalment of our film news series, #MovieNight.

(1) First up, the not so good news. Shadow and Act, the film website that has a crucial online space for news and critique on films and filmmakers of the African diaspora for the last seven years, may close down. In a recent, very personal, blog post on the site, founder Tambay A. Obenson revealed that the recent sale of Indiewire didn’t include any of its individual blogs as part of the package; meaning the future for Shadow and Act is uncertain. We’ll be holding thumbs and sending out positive thoughts. Here’s an excerpt:

I really believe that there’s a need and public want for a web presence the likes of which I summarized above, and that it could be very successful if properly run; especially in a time when issues like “diversity” are cause célèbre here in the USA specifically; although, as we’ve covered on this blog, you’ll find very similar conversations being had across countries in Europe, countries in South America and continental Africa, as well as our neighbors up north, Canada – regions all over the world where people of color are still unfortunately woefully underrepresented in cinema (in front of and behind the camera), and effectively marginalized. If relaunched, it could be a well-run global brand accessible to anyone with an internet connection, anywhere in the world, that we can all be proud of, and will be extremely pleased to know exists. And if I’m going to do this, I want to do it right and go all the way with it, or not do it at all, which, again, takes hard work, people and of course money to build something of real value.

(2) “MTV is telling stories that mainstream established media refuses to tell you,” quipped a South African colleague about the channel’s South African iteration MTV Base’s new documentary on South Africa’s #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall student movements. Since 2015 these movements have brought the academy to its knees and the nation to a standstill. (To refresh, rewatch our video or visit our archive) Left in the capable hands of director Lebogang Rasethaba (Future Sound of Mzansi) and producer Allison Swank (she used to write for us), this is a very promising project. The documentary premiered on MTV South Africa this week. For those of you who didn’t catch it, here is the trailer:

(3) Still on trailers: The trailer for The Birth of a Nation, from American director Nate Turner, finally dropped and it’s looking great. The opening shot of an American cotton plantation, underscored by Nina Simone’s rendition of Strange Fruit is breathtaking. The film deliberately uses the title of D.W. Griffith’s film (1915), which was lauded for its groundbreaking cinematic techniques and shunned for its racist portrayal of black people (it was used as a recruitment tool for the Ku Klux Klan.) Watch the trailer here.

(4) Bi Kidude was Zanzibar’s own “Iron Lady” – not of politics, but of music. She performed classic taarab around the world, combining her formidable talent with an arresting stage presence and huge personality. To mark the death of “probably the world’s oldest singer” (she was thought to be over 100 years old when she passed away in 2013), Andy Jones’ I Shot Bi Kidude was launched recently in Zanzibar. The film focuses on the mysterious and complicated kidnapping of the musical legend by a family member, and is asequel to Jones’ first film about the star, As Old As My Tongue, which celebrated her music, and her unconvential behavior and free self-expression, which challenged the traditional role of women in an Islamic society. You can stream As Old As My Tongue on Vimeo on Demand here.

(5) The director Gavin Hood (remember Tsotsi, the first South African film to win a Best Foreign Film Oscar) has a new movie out called Eye in the Sky, which deals with the disengaged nature and moral dilemmas of modern warfare. Shot in Cape Town (as a stand in for the heavily Somali neighborhood of Eastleigh in Nairobi) the film is receiving mostly positive reviews from other than Kenyan Somalis. It features an impressive lineup of actors, including Helen Mirren, Alan Rickman and Somali-American Barkhad Abdi. Which leads us to the question: Is Abdi being typecasted? He went from a breakthrough role playing a Somali pirate in Captain Phillips, to a Kenyan Somali intelligence operate in Eye in the Sky, to a drug dealer in Sacha Baron Cohen’s awful (some say offensive) The Brothers Grimsby. His next role will be in Where the White Man Runs Away, about a white journalist who embeds himself among Somali pirates. Here’s the trailer for Eye in the Sky.

(6) The Ghanaian-American co-production Nakom is now available to stream in some regions on Festival Scope. The film follows a Ghanaian medical student drawn back into his farming community after the sudden death of his father, and all the obligations that come with such circumstances. He is forced to make a difficult choice between following tradition and the narrative arc that he has projected for his own life. Co-directed by Kelly Daniela Norris and TW Pitman, and produced by Isaac Adakudugu (who actually comes from Nakom), the film looks to be both contemplative and charming.

(7) The new short film Reluctantly Queer, explores same sex desire in Ghana. Shot on 8mm by the Ghanaian-American director Akosua Adoma Owusu (she also did Kwaku Ananse revolves with a young Ghanaian man “struggling to reconcile his love for his mother with his same-sex desire, amid the increased tensions arising from same-sex politics in Ghana.” Reluctantly Queer premiered at the Berlin Film Festival earlier this year.

(8) Keina Espiñeira, a PhD in Political Science and Visual Studies, who also holds an MA in documentary, has made a migration film called We All Love the Seashore. The film seeks to blend documentary and fiction and collide “myths from the colonial past” with “dreams of a better future.”

(9) Finally, a Nigerian director has ripped off the plot of Spike Lee’s Chi-Raq, about a group of women who withhold sex until their men stop fighting. Lee’s film was ideologically a mess, so no surprises when some people on Twitter judged the Nigerian film to be better. Here’s the trailer for the Nigerian film:

April 21, 2016

When Emperor Haile Selassie went to Jamaica on this day in 1966

Fifty years ago today, Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie visited Jamaica. Hysterical crowds of thousands of people greeted him the airport in the capital of Kingston. The Ethiopian resistance to Italian colonialism and later occupation, legendary in the Atlantic world, drew some of the attention, but it was the Jamaica’s Rastafari population who were particularly enthusiastic. Rastafari revered (and still revere) Haile Selassie as divine. Leonard Barrett, in the first extensive study of Rastafari, explains how, in the first part of the twentieth century, the combination of economic and political crises in Jamaica and the rise in Afrocentric belief systems as promoted by people like Marcus Garvey (and his “Back to Africa” philosophy) led to a belief in Haile Selassie’s reign as more than the continuation of Ethiopia’s monarchical government system. The coronation of Haile Selassie I, King of Kings, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah was the fulfillment of Biblical prophecy. In Kevin McDonald’s film Marley, Bob Marley’s wife, Rita, recalls meeting Selassie and recognizing his divinity.

From 2004 to 2013 I engaged in research that looked at the relationship between Ethiopia and Rastafari, resulting in this book. I was fascinated by the appeal of Ethiopia to Rastafari, but also, crucially, how the Ethiopian population perceived the Rastafari movement. Haile Selassie and his April 21, 1966 visit to Jamaica cast a big spell over this relationship.

Ethiopian academic Alemseghed Kebede, who analyzed various Rastafari thinkers for his Ph.D., was led to his research topic on the role of cultural understanding among Rastafari by his immense curiosity about Rastafari and their view of Haile Selassie. According to Alem, the way Ethiopians view Rastafari is colored by the fact that the latter have a different way of looking at the figure of Haile Selassie:

I was one of those people who was saying to myself, “Why would they consider Haile Selassie as God?” And, secondly, why would Ethiopia, which is a very poor nation, why would they take it as and consider it as the Promised Land? . . . I was dismissing their movement. I was saying that there is no way someone in their right mind could believe that Haile Selassie was a living God. I think there is misconception of the Rastafari when they talk about Haile Selassie. They are not talking about what you and I or the rest of people know. They don’t have this kind of historical view of this person. They have this symbolic understanding about the living God. Then, at that time, during the 1930s, you see Haile Selassie emerging as a very important figure and of course afterwards he is one of the founders of the Organization for African Unity and internationally he is a very interesting figure. All of those things were very important symbolic elements, in order for [Rastafari] to make a decision in terms of who this person was, so I think that is how they came to the conclusion that Haile Selassie was God, and Ethiopia, heaven on earth.

Alemseghed’s explanation points to a gap between what he refers to as an Ethiopian, “historic” notion of Haile Selassie, and the Rastafari “symbolic” view. There is a perceived divide between Rastafari and everyone else—Rastafari have one view and “the rest of the people” have another. His immediate reaction to Rastafari, namely, asking why Haile Selassie and why Ethiopia, demonstrates that the answer and framework of understanding for Ethiopians is very different from that of Rastafari. Exemplifying this situation is a narrative that I have come to term the “Miracle Story,” which describes the April 1966 visit of Haile Selassie to Jamaica in very different ways, depending on the perspective of the storyteller.

“I know that the Jamaicans are here because of our king,” Daniel Wogu, an eighteen-year-old student and Shashemene inhabitant working toward acceptance in a medical program, told me. “They believe that he is sent from God to save them or make the black people free from slavery. They have their own history,” he continued. “As I have learned from Ethiopian history, they say that our king went to their country to visit and there were some unexpected happenings. There was rainfall or something. They say then that this proves that Haile Selassie is not actually a man, but is God.”

Henock Mahari, an Ethiopian reggae musician born and raised in Addis Ababa, the city where he still lives and works, said something similar: “He was once in Jamaica and it hadn’t rained, and then it did rain. They accepted him as a God because of this miracle. They see him as a messiah and call Ethiopia their Promised Land and leave their home to come here and finish their life here.” In a general discussion with my hundred-strong English language class at the Afrika Beza College, a female student told me that “Jamaican people live in Shashemene and they like Ethiopian people very much because Haile Selassie went to their town and at that time there is no rain. When Haile Selassie got there, there was rain. So, after that day, Jamaican people like Ethiopia very much.” Shemelis Safa, a high school teacher in the town, had a similar explanation for why Rastafari move to Shashemene: “As I know, Haile Selassie went to Jamaica. It was very dry and they needed rain. Unfortunately, when this king arrived in Jamaica, the rain came.”

At the patriarchate in Addis Ababa, a scholar of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church described a similar phenomenon and how this divided the perceptions of Rastafari from Ethiopians: “Generally speaking, the understanding we have on [the] issue [of Haile Selassie] between us and the Jamaicans is different. The Rastafarians believe in once upon a time when Haile Selassie visited Jamaica, the country was suffering from drought. And right after his arrival, the rain fall. They consider him a god, because they associate him with what happened.” And a Shashemene-based Orthodox priest also told me of the rain starting when the emperor arrived. Even Haile Selassie’s grandson, Prince Ermias Sahle Selassie, told me that he had also always been told that story. I could recount many more of the same narrative, but they all generally amount to the same thing. There was a drought in Jamaica, and when Haile Selassie arrived in the country the rains started and the people of Jamaica were thankful. No individual I spoke with could provide further information about when or where this occurred or any other aspect of Haile Selassie’s visit. Most importantly, however, no storyteller could provide any specific source for the story. I tried to track down some semblance of source material, but to no avail. The essence of the tale, however, is significant: the miracle of rain directly relates to the consideration of the emperor as divine.

Each of these stories underlines the importance of rain in Ethiopia, given the high numbers of subsistence farmers and the historic prevalence of famine-causing drought. Drought is perhaps mentioned because it makes sense to Ethiopians. In addition, acknowledging a perception of Haile Selassie performing a miracle can justify belief that the emperor is divine by linking him to the Orthodox Christian tradition of reading the miracles of Mary as part of the church service. As philologist Getatchew Haile has written, “miracle stories were designed to be read in the churches and monasteries of the empire, as indeed they still are, during daily church services like the reading of the gospel.” Given the role of miracle stories in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, this reading of the Rastafari faith can be viewed as inserting Rastafari into an Ethiopian understanding of religion. Thus the otherwise strange belief in the former emperor as God can be placed in the context of Ethiopian realities and an Ethiopian narrative of faith. Relief from drought and divine intervention are relevant to Ethiopian culture and belief. This provides an opening for Ethiopians to welcome Rastafari into the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

Watching the documentary footage by Vin Kelly of the Jamaica Information Service of Haile Selassie’s arrival in Jamaica on April 21, 1966, it is obvious from the wet tarmac that something quite different occurred when Haile Selassie arrived in Jamaica. As observer Dr. M. B. Douglas reported to Leonard Barrett, “The morning was rainy and many people were soaking wet. Before the arrival of the plane the Rastafarians said that ‘as soon as our God comes, the rain will stop.’ This turned out something like a miracle, because the rain stopped as soon as the plane landed.” Though this description also described the event as a miracle, it is the complete opposite of the miracle outlined by my Ethiopian informants. Instead of Haile Selassie causing the rain to start, here he stops the rain so the celebration of his arrival can begin.

I see these conflicting narratives of Haile Selassie’s arrival as emblematic of the conflicting narratives of Ethiopian identity—one on behalf of Rastafari, the other on behalf of Ethiopians themselves. Each conception of identity is based on history, faith, and cultural realities which are different for both groups. In addition, there is more than a single sense of Ethiopianness for Ethiopia itself. The various and varied ethnic groups each have their own history, faith, and cultural reality that together work to piece together what it means to be Ethiopian.

Though Daniel Wogu and Shemelis Safa mention the connection to freedom from enslavement and the Solomonic dynasty respectively, the main thrust of the stories is that of the rain falling, a miracle made possible by the man Rastafari revere. It is the only explanation for the Rastafari belief. A story like this does not take into account any of the “symbolic” aspects contributing to a belief in Haile Selassie as divine, discussed by Alemseghed Kebede. However, despite the difference of perspective, the fact that the miracle story can be understood according to an Ethiopian Orthodox narrative underlines the importance of the church as a unique point of integration between Rastafari and the Ethiopian population. Haile Selassie himself seems to have felt this way too, as demonstrated by his reacting to Rastafari by shifting the focus away from his divinity and onto his faith in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

*This post is adapted from MacLeod’s book Visions of Zion: Ethiopians and Rastafari in the Search for the Promised Land, published by NYU Press and available here.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers