Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 311

March 11, 2016

The ‘Big Man’ Syndrome in Africa

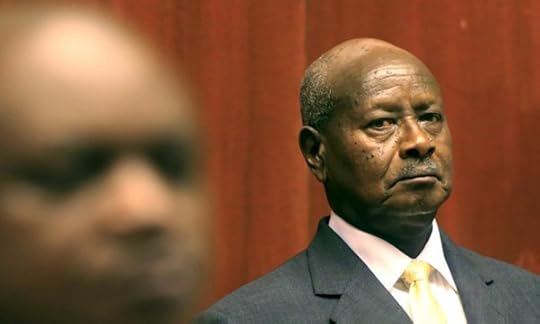

Why do so many African leaders overstay their welcome or break electoral rules? In the recent elections in Uganda, 30 year incumbent Yoweri Museveni won a fifth five-year term. Opposition activists are contesting the results. This has raised again that eternal post-independence question. Museveni is seventy-one years old and has governed since he took power in a military coup in 1986; longer than the majority of the country’s population have lived. Some Ugandans console themselves with the fact that the country’s constitution has an age limit for the presidency of 75 years. But as the South African television anchor Imran Garda joked on Twitter: “Yoweri Museveni declared the winner of Uganda’s election. And the one after this. And the one after that one too.”

Museveni is not alone. More recently Rwanda’s Parliament voted to change electoral rules that would mean Paul Kagame, President of Rwanda since 2000, could govern till 2034. A parliamentary commission that traveled around Rwanda eliciting comment on Kagame’s third term plans, strikingly could only find ten people who disagreed with the proposal. Although questionable, Kagame is genuinely popular, but it is unclear why no one else in Rwanda is qualified to lead.

The Republic of Congo (also known as Congo-Brazzaville) just extended the total 32-year rule of Denis Sassou Nguesso via a referendum marred by irregularities. Elsewhere popular unrest and resistance have followed incumbents’ desire to illegally extend their tenures, as witnessed recently in Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

One ready-made explanation usually trotted out to explain this behavior, is that of the so-called “big man” syndrome, which sources it to African “culture.” However, this disease is rather a product of recent African history. Colonial administrators utilized African traditional structures for “indirect rule,” but deformed them by promoting the power of the chief or the traditional leader at the expense of the precolonial checks and balances mechanisms. Post-independence African presidents have just perfected these systems.

So how do these African leaders retain political power?

The short answer is: Because they can. Electoral systems operate at the discretion of the President. In practice, the President make the rules, breaks them and changes when he wants to (yes, it is normally a he). Museveni, for example, effectively controls the electoral commission and the coercive apparatus of the state: Who controls the count, wins the election and in the lead-up, the police and the army harass and intimidate the opposition, while the president campaigns uninterrupted.

Furthermore, equating popular will with the president’s person is key. The President is always patriotic, and it is only the President who is willing and able to do what is needed. Paul Kagame’s defense was that it was not that he wanted to extend his rule: “It’s the people, you see, they want me to stay on.” And the President always needs more time to fulfill his agenda.

Museveni needs five more years to do something he could not accomplish in the previous thirty.

Furthermore, the Presidency is a family business and there is no future or monetary gain outside politics. Accumulating wealth and business opportunities are tied to controlling the state. So, is the economic fortunes of your allies, party officials and, crucially, the President’s family. Once you are out of office, you lose your ability to steer contracts or get a cut from profits. After tenure, the then former President—or, even more so, his allies—also risk prosecution either for embezzlement or human rights abuses.

Also key is the role of outside forces. The African Union (AU) rarely sanctions leaders who break electoral laws. It is striking that the current AU chairperson (a rotating one-year symbolic post among African presidents) is Idriss Deby of Chad (in power since 1990), that his predecessor was Robert Mugabe (in power in Zimbabwe since 1980) and before that Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz, who came to power in a coup in Mauritania in 2005, filled the seat.

Don’t expect the African Union to expel or sanction Museveni. Four hours after Museveni’s victory, neighboring Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta posted on Facebook: “The people of Uganda have spoken, and they have spoken very clearly.” The rest, even those elected in open, free elections–like Jacob Zuma of South Africa–fell in line.

As for the United States and the European Union, criticism of electoral processes sounds hollow if you keep investing in extractive industries that fund illegitimate rules of Presidents of resource rich countries (as in Angola) or let “War on Terror” considerations (in Uganda, for example), trump democracy. Although the fall in the oil price has dramatically reduced the Angolan state’s income, the revenues from oil still accounts for close to half of the state budget. Which is the source of President Eduardo dos Santos and his family’s personal wealth. There is a joke about Angola: “Who is the public in Angola?” “The President.” “Where does all the money go?” “To the public.”

Just as outside forces do, the political class and the military and police guarantee the president’s rule. But they can also precipitate the president’s downfall. In the DRC, Joseph Kabila is frustrated by members of the political class who are deadlocked over whether to legitimize his illegal efforts to prolong his rule. Even more dramatic were recent events in Burkina Faso and Senegal. There the police and army were used to harass the opposition, yet proved crucial to ending impunity. In 2012 when Senegalese President, Abdoulaye Wade, was outvoted two to one by his opponent Macky Sall, he considered declaring himself winner up until the point when emissaries from the security forces—mindful of the popular opposition against Wade—came to warn him that he would not have their support and that they would respect the election result.

In this context, it is significant that Senegal’s current president, Macky Sall, recently announced a referendum to reduce his mandate by two years. “Have you ever seen presidents reduce their mandate?,” Sall is reported as saying. “Well I’m going to do it. We have to understand, in Africa too, that we are able to offer an example, and that power is not an end in itself.” The actual truth, as Sall (who is facing criticism with the slow pace of change in Senegal) himself when he was running for office told Yen a Marre, the Senegalese youth movement that played a key role in Wade’s exit, was that he, Sall, didn’t want to face the kind of revolt Wade faced.

March 9, 2016

Africa is a Country’s Pan-African Space Station transmission archived

Last November, Africa is a Country teamed up with Chimurenga’s Pan African Space Station library-of-people installation at the Performa 15 Hub in New York City. We were able to curate three panels over the course of a weekend, hosted by: academic and writer (and non-academic soca specialist) Rishi Nath; immigrant rights activist Thanu Yakupitiyage, otherwise known as DJ Ushka of Brooklyn’s Dutty Artz collective; and AIAC photography editor Zachary Rosen.

We wanted to make sure to archive the conversations, so you could listen if you missed them when they went live. So here are the embeds via our Soundcloud for you to enjoy again and again!

Block The Road: The Sound of Afrosoca

An exploration of the recent explosion of cross-Atlantic exchange between Caribbean and African musicians, with Rum N’ Lime Radio co-hosts – Queens-based writer and academic Rishi Nath, and DJ, producer, and Trinidadian Soca ambassador DLife.

Adrift: A soundtrack for migration

A current and former member of the Brooklyn DJ collective Dutty Artz, DJ Ushka (Thanu Yakupitiyage) and Lamin Fofana, talk about Fofana’s recent EP as a jump-off point to discuss migration — from what the Western media has dubbed a European “migrant crisis” stemming from Africa and Syria — to other examples of being “adrift.” The two draw on their personal experiences as immigrants to the U.S from Sri Lanka and Sierra Leone respectively to discuss how they’ve incorporated heavy themes of (im)migration into their work as musicians and activists. What turned into a two-hour podcast, features both Ushka and Lamin’s musical selections as a soundtrack to being adrift – both physically and geopolitically.

Seeing voices: Reflections on African photographic portraiture

Zachary Rosen moderates a discussion with Delphine Fawundu, a Brooklyn-based photographer. In her work she focuses on identities through cultural expression; incorporating themes of social justice, music and history.

March 8, 2016

All you need to know about Uganda’s 2016 elections (and aftermath)

President Yoweri Museveni came to power after a civil war in 1986 and some Ugandans had hopes this election would be different. Initially the signs weren’t good. The police regularly harassed opposition supporters. In January, Museveni refused to participate in the country’s first pre-election television debate (on domestic policy) between presidential candidates, because “such events were for schoolchildren.” Then in early February he changed his mind and took part in a second debate on foreign policy. The debate was a tepid affair, but raised hopes about a more competitive, open contest. Those hopes were soon dashed. The leading opposition candidate Kizza Besigye was arrested a days before voting day, stopping him from addressing yet another packed rally at Makerere University.

Image via Twitter

Image via TwitterThen on Election Day, the Electoral Commission (EC) did not deliver materials to polling stations where the opposition was predicted to dominate. The police and military (who can’t be separated anymore) arrested Besigye again. Since then, Besigye has been under non-stop detention, sometimes driven from his home to police cells, and returned to spend nights at home.

The EC declared Museveni the winner with 60%, omitting results from opposition strongholds in the tally. Meanwhile, the military had occupied Kampala and its environs and to date does not show any signs of a withdrawal plan.

When Museveni was announced winner of the election, no crowds hit the streets to celebrate. The air of tension refused to dissipate even when social media, which had been blocked has been reinstated.

The reactions of other African leaders were crucial. Kenya became the first country to send congratulations to the chagrin of many Kenyans and Ugandans. Burundi, North Korea and Russia followed.

The United States in a statement criticised the poll and mentioned that Uganda deserved better. The opposition called the election a sham and asked the youths to take to the streets to protest. Former Nigerian president Olesegun Obasanjo, on behalf of the Commonwealth Observer Mission called for dialogue, to resolve the impasse. Botswana criticised the poll and called for a peaceful resolution of disputes.

Image via Twitter

Image via TwitterCommentary has been flowing since the election. Here’s what I’d recommend you’d read:

In an article written for TIME.com, Clair MacDougall focuses on the disconnect between the words coming off the US government’s lips condemning the election while the same country continues to line the pockets of Uganda’s military. The Ugandan American Editor of Black Star News, Milton Allimadi, in an open letter to the US President detailed the extent to which the Obama administration has gone to entrench the Museveni dictatorship.

Jamie Hitchen, a researcher at the Africa Research Institute, has a good take on the Electoral Commission’s institutional credibility. He also gives an overview of the numbers. Even better is Development Seed.Their report maps the rigging and ballot stuffing trends.

The journalist and filmmaker Kalundi Serumaga compares the 2016 election to the 1980 election that was so heavily disputed, Mr. Museveni, a candidate who came a distant third took up guns and headed for the tall grass, where he spent five years killing, till he overthrew the ‘elected’ government.

Senior journalist Daniel Kalinaki explains the difference between winning the hearts of the people, and actually taking power in an op-ed column for Uganda’s Daily Monitor.

General David Sejusa, who is in jail over engaging himself in political activities while still a serving soldier writes from his prison cell and provides an insightful analysis of the generational tension in the country’s political space.

Ugandans in the diaspora are also responding to the crisis through protests. Those in Canada were the first. And Boston followed.

Museveni via Reuters

Museveni via ReutersAs for popular culture, the singer Matthias Walukagga has released a song, “Referee” criticising the Electoral Commission (dominated by Museveni loyalists). When musician Bobi Wine released a pre-election song calling for peace, titled “Ddembe,” (peace in Luganda), it was rumored to have been banned. After the election, the musician removed the gloves and released “Situka (Rise)” whose lyrics capture the mood of the times.

When leaders become misleaders and mentors become tormentors, when freedom of expression becomes a target for suppression, opposition becomes our position.

Chrisogon Atukwasize’s cartoons depict the tensions that existed during the campaign period and show no signs of disappearing soon. In one cartoon, Museveni’s party secretary general threatens that the ‘state’ shall shoot any youth who dare to protest the election result. In another, he portrays Electoral Democracy as dead in Uganda.

As for social media, The Kampala Express, a Facebook newspaper edited by journalist Timothy Kalyegira has perceptive post-election updates that show a growing trend of violence in the country. The medical anthropologist Stella Nyanzi’s Facebook timeline has some of the most well-written opinion and reportage about the entire electoral season. Often colored with sexual imagery, Dr. Nyanzi’s writing proves that the lines between the personal and the political do not exist in today’s Uganda.

What about books?

As for the rivalry between Besigye and Museveni, according to many a regime propagandist it is personal. Daniel Kalinaki’s 2014 biography of Besigye, who is considered the country’s President-elect by many disgruntled Ugandans, provides an extensive background to the opposition movement against Museveni. The book can be ordered via Amazon.

Four years before Kalinaki’s book, Olive Kobusingye, a blood relation of Besigye’s published The Correct Line?: Uganda under Yoweri Museveni, which juxtaposes Museveni’s 1980s and 1990s statements about democracy with his deeds in power following Besigye’s first public confrontation of the system in 1999.

Museveni, as usual, gets the last word. It is important for one to read from Museveni’s own pen to put the Besigye (or opposition) perspective in the right context. Sowing The Mustard Seed: The Struggle for Freedom and Democracy in Uganda gives a glimpse into how the man who has ruled Uganda longest, the country’s only living leader (all past leaders are dead) viewed his own contribution to ‘liberating’ Uganda before he took to the bush to fight a five year war, during the war and after he won it and became president.

Finally, we would recommend these people on Twitter: @amgodiva (lawyer-activist), @Natabaalo (journalist), @cathkemi (journalist), @enamara (twitter personality), @bkabumba (lawyer – academic), @asiimwe4justice (lawyer – activist), @RosebellK (blogger), @tomddumba (political strategist), @IsaacImaka (journalist) and @FrankWALUSIMBI (journalist).

March 6, 2016

It’s the economy, N°4

Yes, this is a weekly series. Barclays Bank dominates this week’s missive. Oh, what is 16 plus 6? Don’t tell us yet. Hold that till the end.

(1) This past week, the British bank Barclays announced plans to exit the African market after a formal presence of about a 100 years. The bank currently employs about 40,000 people across the continent.

(2) The initial reaction for many was to think that Barclays was passing a vote of no confidence on the continent’s future. But closer inspection reveals that the African business is being sacrificed (surprise, surprise) to save the mothership. Barclays needs extra capital and some of that will come from selling its Africa business. “It’s not an Africa problem; rather it’s a Barclays problem”.

(3) One cannot even begin to imagine how many of the 40,000 workers feel right now. They’ve worked hard for the bank. Delivered impressive results. And now the future seems uncertain. What will happen next? Will the bank be broken up into smaller bits? Will someone buy the business as a whole? Will the new owners maintain current levels of employment or maintain employee benefits? So much uncertainty.

Africa, foreign capital is not your long-term friend.

(4) Bob Diamond is in talks to buy parts of Barclays’ Africa business. Who is Bob Diamond, we hear you ask? Well, he was in-charge of Barclays during the time that the Libor manipulation scandal was unearthed (Libor is a crucial interest rate that ultimately determines interest rates on mortgages, credit card debt and so on). As a result, he was forced to resign his position as Barclays CEO in July of 2012.

Diamond has been busy buying up banks in Africa since leaving Barclays. Ah, capitalism. Heads I win, tails you lose.

(5) In Zambia, the Ministry of Finance confirmed that a team from the IMF will be visiting the country this coming week to discuss, among other things, the possibility of an IMF Program. “IMF Program” is IMF lingo for a bailout package with strings attached.

Zambia has in the recent past borrowed heavily on international debt markets and is now experiencing the beginnings of what appears to be a sovereign debt crisis.

(6) Buoyed by high commodity prices and plain-old irrational exuberance, many African countries (like Ghana and Zambia) borrowed on international debt markets beginning in the last decade. Commodity prices are now falling making it difficult for countries to service their debt. Some analysts think that debt traps typical of the 1980s and 1990s might be on the horizon. Back to the future, anyone?

(7) Still sticking with the issue of international debt: there is growing debate about corrupt practices associated with either the contraction of debt (see the case of Standard Bank in Tanzania) or with how the proceeds of debt are spent (for example in Kenya and Zambia).

(8) Some more on debt: Carlos Lopes, the head of the UN’s Economic Commission for Africa in Addis, had an insightful op-ed in the Daily Maverick this past week. In the piece, Mr. Lopes tackles some of the myths surrounding Africa’s past indebtedness. For instance, Cold War geopolitics were just as responsible for the debt build up as were domestic factors. Lopes concludes the piece by suggesting ways of managing current levels of debt stress on the continent.

(9) We were shocked to learn this week that only 60% of “economics studies published in the field’s most reputable journals are replicable”. And it appears that authors are exaggerating, by quite a bit, the magnitudes of their results. (And yes, the replication exercise only looked at 18 studies from laboratory experiments published in two journals. Even then, we still think this is cause to worry).

(10) Happily, the movement to reform how economics is taught in Western universities seems to be gaining ground. We would also like to see a similar movement to reform how economics is taught to students in many parts of Africa. The discipline is currently taught through a Western lens and hardly reflects nor sufficiently exposes students to African development realities. The dominant textbooks are chockfull of examples on the market for lattes and cappuccinos. As an undergraduate economics major at the University of Zambia, our resident economist had no clue what a latte or cappuccino was. But he sure as hell knew what the market for munkoyo looked like.

(11) Finally, should we be worried that Nigeria’s Minister of Finance, Kemi Adeosun, cannot correctly add N6 billion to N16 billion?

March 4, 2016

Uganda Belongs to Us

“I was born here/I will live here/And I will die here.”

– G.N.L Zamba, Uganda Yaffe (Uganda Belongs to Us)

—

You must have heard the leopard say that he works for himself, his children and grandchildren when a cheeky Kenyan journalist asked him about retirement from the presidency.

Here is Liz Abwooli, a young Ugandan calling on fellow Ugandans to organise nonviolent campaigns until the leopard’s dictatorship falls. Young Ugandans are knocking on the leopard’s door. They want their country back. They no longer care about which part of the leopard they are touching, they want their country back.

Have you seen these children pelting the leopard’s campaign poster with rocks and stones because they are tired of being tear gassed? Uganda is theirs, too. Uganda is ours. It is not the personal property of the leopard.

The Ugandans may not put their bodies on the streets to be shot by the leopard’s armed gangs. It does not stop their hearts from bleeding from inside. They do not stay away from public protests because they love a 71-year old, who has been in power for 30 years, has cheated elections since 2001, shot his way around opponents and bombed neighbouring and far off countries into supporting him.

The Ugandans have not given the country to the leopard. Even when he continues to treat it as his personal property. Even when he talks of its resources as though they were his personal resources. He even says that he owns the country’s currency. The people went to the ballot, aware that the leopard would steal it. But they went. They told him that they are tired. They told him that this is their country. This is our country.

Who are the people?

Ssekandi Ssegujja Ronald. Young man. In his 20s. Born when the leopard had already taken power. Forget what they say about young people. Ronald is building the country. He is committed. He is training young people in debate. Running activities through an organisation he started with age mates. The leopard’s government does not even think it is their responsibility to do what Ronald is doing. But he is doing it. Building the country. His country. Their country. Our country.

Ronald and his friends have created a platform to mould young people into good citizens. It is Ugandan. It has branches into Rwanda. And Kenya. It is East African. Uganda is his. He has travelled the world, Germany, the United States. He is Uganda. This is his country. His colleagues, Wamala Emmanuel Ssonzi and others own Uganda. This is their country. They are calling. They want their country back. They may not be on the streets carrying branches, it does not mean that they do not want their country back.

Go home, old man. Stop blabbering about your opponents. Slandering them. Your robots may insult Besigye, your armed gangs may humiliate him, the PR company you hired may send automated social media accounts to troll his wife, but hey, the people are saying that they want him for President. Uganda is not your personal property. It is for all Ugandans and they are telling you that the office of the President is Besigye’s. They have appointed him. Go home. Stop threatening to burn everyone. Keep quiet and go home.

Uganda is King Godiva‘s. Fiery feminist, academic, lawyer, consultant. She is in her 20s. Building Uganda. Educated in Uganda and in the United States at top universities, she wants you, Mr. Leopard to go home. She voted. She stood under the sun for hours. Waited. Your man Kiggundu’s plans to disenfranchise her failed. You blocked social media. She bypassed your blockade. She tweeted throughout the day, shared videos with us, updates about everything. Even told us the results. You lost at her polling station. As you did at thousands other polling stations. Uganda is hers. Respect her. She has built Uganda. She is building Uganda. Go home. She wants her country back. She has chosen to hand the job of President to someone else. Go home. Respect her. Uganda is not your personal property.

Young people are putting work into this country. They are building this country. They are not hooligans. They are not idlers on social media. They are building this country. Respect their labour. Respect them. Go home. Uganda is not your personal property. Uganda is ours.

No bullet can paint love in the hearts of Ugandans. You disgust some Ugandans who feel that they can’t tolerate you anymore. They have been patient enough. Some stopped recognising you as their president in 2001, others in 2006, others in 2011, and now many more are saying that you are not their president. Despite our non-recognition of your presidency, we continued to build our country. Respect our labour. Respect us. Our humanity. Our dignity. There is a difference between love for country and support for your illegitimate rule.

We want you gone. Even if Stella Nyanzi prepares to take her children to school a day after the sham electoral result is announced, you are not her president. Her President is Kizza Besigye. You can’t shoot yourself into her heart. Go home, old man. Uganda is not your personal property. Uganda is ours. We have built this country. We build this country daily.

You are an old man. Go home and maybe we will even want to hear your stories. Write books. Develop your pseudo theories about African languages. Leave Uganda’s state properties. Get a life! You will be fine.

We have been building this country despite your corruption, nepotism, greed, name it and you have it. Your unquenchable thirst for blood has not stopped us from building this country. Your war mongering has not stopped us from connecting with people whose countries you have destabilized. We have ignored you for long. We are saying that enough is enough. Go home, old man. Uganda is ours. It is not your personal property.

Young women, professionals, men, Ugandans, unemployed, self employed, business people, the middle class, the lower classes, people in urban areas, people in rural areas, Facebook and Twitter masses, we, the people, ordinary soldiers in the national army, we have chosen Besigye as the President of our country. Of Uganda. Legally. We are telling you old man, that you should go home.

Our hearts have no space for your lies. Your guns will not win our hearts. You have already killed some of us, including a twelve year old! Shameless man! You want to stay in power at all costs. No single life is worth your greed and megalomania. We may stay indoors because your ego and greed blinds you. It is not worth our lives. We are not giving this country to you. We are disgusted. Our President is Besigye. Go. Home. Old. Man. This is our country. We will continue to build it.

We are not grateful to you for anything. We build this country ourselves. Do not tell us no nonsense about things you have brought. We have paid for them. We have contributed. In fact, you have underperformed as president. We are firing you. Go home. Uganda is not your personal property. It is ours.

We are young, we are women, men, from rural areas, urban areas, on Twitter, on Facebook, some of us do not even know about social media. We all are saying, go home old man. This is our country. We may not put our lives on the street for you to shoot. But you know that we want you gone. We shall not cooperate with your regime. We shall continue to build our country while defying your dictatorship. Millions of Ugandans call Besigye the people’s President. Why don’t you go? Go.

This is our country. Leave. Even if you leave tomorrow, or next month, or next year, or even in ten years’ time, you can’t be the people’s President in 2011. GO! Leave. This is our country.

March 1, 2016

Scotland is a continent: ten years of Africa-in-Motion

2015 marked the tenth anniversary of the Africa-in-Motion film festival, the showcase for African cinema in Scotland, which its director Lizelle Bischoff has described as being a wider, more-encompassing arts festival. The festival’s home has traditionally been the Edinburgh Filmhouse, an independent cinema in the city centre. From 2007 onwards, the festival began to take its program to Glasgow, which is now a fully embedded element of the event. These two cities combined are home to 32% of Scotland’s minority population, although Glasgow is the city most associated with diversity. The program has in the past gone on tour in rural parts of Scotland, and participated in UK-wide touring programs, such as 2014’s South Africa at 20.

The festival works across multiple venues, from academic spaces and pop-up venues, to bars, restaurants, and community spaces. The festival is realized through an array of partnerships but principally funded through the arts council, Creative Scotland. The theme of 2015 was ‘Connections’ which was to be understood in a number of ways including ‘political connections, artistic collaborations, generational ties, lost and restored cultural links, and pan-Africanism.’ Additionally the ‘From Africa with Love’ strand featured a number of films and events programmed as part of the British Film Institute’s nationwide ‘Love’ season, and there were Nollywood industry events and premieres sponsored by the current British Council UK-Nigeria 2015/2016 initiative.

It might seem laborious to sketch out this kind of basic organizational framework here, but throughout my attendance of last year’s 10th edition, the question of how to review a film festival holistically was been at the forefront of my mind. In such a programming format and location, where I am seeing the film, who I am seeing it with, who is producing the program, who is and is not speaking to me, and who is funding it (and why) are all very present components of the experience. I am unsure whether it will be of interest to the readership of Africa is a Country, but certainly for me on an individual basis at least, the positioning and responsibilities of Africa-in-Motion in its local context are also primary concerns. I have been going to the festival over this ten year period, and so this review is inevitably informed by an experience accrued over that period. It is worth saying that without Africa-in-Motion, my access to African cinema in Scotland then and now would be limited.

The stand-out film at this year’s festival was Phillipe Lacôte’s Run. The film follows our protagonist through his three lives, which in the question and answer session the director revealed came from a conversation with a former member of the Young Patriots, often classed as a youth movement and militia, active in the recent civil wars in Côte d’Ivoire. Our central character, Run, lives up to his name, and from each of these three lives, he ends up running. In Run’s first life, he is an apprentice and named as successor to the village rainmaker. Despite the role of the rainmaker being all that Run dreamed and wished for, the village elders soon demand that he kill his teacher, which he refuses. Fleeing the scene, he is picked up on the road by Greedy Gladys, a professional eater, who takes Run on as her manager and emcee. Her show tours from town-to-town, in an eating competition to consume as much food onstage as the locals provide her with. Gladys is depicted as being from Burkina Faso – a ‘foreigner’ – a fact which is to play its part in her downfall.

Still from Run, Phillipe Lacôte, 2015, Ivory Coast.

Still from Run, Phillipe Lacôte, 2015, Ivory Coast.Lacôte discussed the film as being a portrayal of violence in the aftermath of the civil war, not yet able to discuss forgiveness and reconciliation. A major theme of the film was that of Ivoirité – a nationalistic term that took on xenophobic ideas during the civil war and was used as the basis to exclude the migrant population. I saw this aspect of the film as holding wider resonance, speaking to many nations worldwide currently struggling with the resurgence of right-wing movements and similar issues of rhetoric around nationhood and citizenship.

The opening film for the 2015 festival was Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Hyènes (Hyenas, 1992), which had previously been shown in the 2007 festival. It is undoubtedly a masterpiece and a satirical take on the relationship between post-independence Africa and neo-imperialism in a globalized, capitalist world. The film tells the story of Linguere Ramatou, an aging woman who returns to her home village of Colobane seeking revenge on her ex-lover. The film was programmed in the Love strand yet despite the storyline, I read this film as neither about love nor revenge. Whilst it is always a welcome opportunity to watch the classics of African cinema, the opening film defines the tone, and in this sense, I found Hyènes to be an unsuccessful choice as it sat awkwardly within this thematic context.

The following evening the program continued with Samba Gadjigo and Jason Silverman’s biopic of Ousmane Sembène. Such a film is an important act and educational tool: a means to make the details of Sembène’s life accessible, public and to continue the process of historicizing his contribution and output since his death in 2007. The film was split into thematic chapters, with short animated markers separating these out, which I found to interrupt the flow of the film. Initially, the film felt one-dimensional; very much in praise of the film-maker, and in fact more a document of the biographer’s own relationship with the filmmaker than a document of Sembène himself. However towards the end, a more nuanced picture emerged, particularly through the interviews with his son and live-in housekeeper. His housekeeper was one of few female voices heard in this film; it is largely a film about a man, told by other men. Documentary footage is used of his second wife speaking about him whilst they were still married, his first wife is never named, and I found this female absence, somewhat ironically, very pervasive.

Still from Black Girl, Ousmane Sembène, 1966, Senegal.

Still from Black Girl, Ousmane Sembène, 1966, Senegal.Sembène! was followed by a Q&A session with producer and director Samba Gadjigo, before a screening of the filmmaker’s first feature film from 1966 La Noire de… Frequently translated into English as ‘Black Girl,’ the translation misses the significance of the ‘de,’ implying ownership. It was a real highlight of the festival; the copy screened a recently restored edition. Shot in black-and-white, the film is saturated in style and is equally poetic and melancholic. The story follows a young woman, Diouana, who obtains her first job as a nanny for a French family in Senegal who move back to France, taking her with them. Cooped up in their apartment on the French Riviera, she is maltreated by her employer and suddenly burdened with all the household chores. Receiving no pay to send home and cut off without communication with her family, she commits the ultimate act of defiance. Relatively short for a feature at 65 minutes in length, the film is perfectly paced, deftly communicating all it needed to say and more in its succinct duration.

Another film of note was Rwandan director Kivu Ruhorahoza’s Things of the Aimless Wanderer. The film is accomplished and beautifully shot, using only a BlackMagic Cinema Camera on this small budget production. It has an unconventional structure, divided between four ‘working hypotheses’ all merging into one another with no resolution. We follow at a distance three nameless central characters: a local man, a local woman and a white male foreigner. The foreigner is visiting whilst producing a travelogue, and gives the film its title ‘from Bantu accounts of early European explorers renowned for getting lost in their wanderings.’

Still from Things of the Aimless Wanderer, Kivu Ruhorahoza, 2015, Rwanda.

Still from Things of the Aimless Wanderer, Kivu Ruhorahoza, 2015, Rwanda.Described as being a deconstruction of ‘masculinity and territoriality’ and the ‘relations between “Locals” and Westerners… paranoia, mistrust and misunderstandings,’ it was set against the context of the Rwandan genocide by the director during the Q&A. A prominent point of discussion in the conversation afterwards was the silence of the female protagonist; unlike the two male characters, she speaks not one word during the entire film. There was a disjoint for me between how the director described her power and gender equality in Rwanda generally, and what I saw onscreen.

Mixed messages were overlaps in two of the films coming towards the end of the festival’s run, Dis Ek, Anna (It’s Me, Anna, 2015) and L’oeil du Cyclone (Eye of the Storm, 2015). Dis Ek, Anna follows a young girl Anna Bruwer, whose step-father sexually abuses her, eventually impregnating her, causing her as a teenager to flee the family home. Later, now working as a seamstress, she is found by her younger sister, who has suffered the same abuse and commits suicide that night in Anna’s home. In revenge, Anna returns to her childhood residence, and shoots dead her step-father. The film unfolds through flashbacks as Anna hands herself in at the station, discloses long-held secrets to her lawyer and psychologist, and in the duration of the court case. I found it difficult to balance this depiction of her harrowing childhood experience with the presence of certain privileges and the privileging of her narrative within the film and its South African context. Without money to pay for her lawyer, a schoolfriend turned lawyer steps forward (they later develop a relationship), she is bailed out of prison, accommodated in an apartment and sees two psychologists.

A second problematic narrative emerges, a sub-plot to Anna’s story, receiving a minority of screen time. The same police officer who first interviews Anna upon handing herself in is also investigating an instance of baby rape and murder in a black township. Despite the community knowing the perpetrator, a repeat offender, he is in hiding and protected. It was unclear to me whether this ‘sub-plot’ was within the original books or was added for this film adaptation. I think it is right that Anna’s experience was contextualized within the wider landscape of South Africa, but the manner in which this was done was very troubling. Furthermore both narratives here involved the rapists, killers and pedophiles being murdered, which I would consider to be an irresponsible message to send to audiences. At Africa-in-Motion the film was described as part of a new generation of Afrikaans filmmaking which also felt questionable.

In a similar vein, L’oeil du Cyclone tells the story of a defense lawyer, who successfully represents in court a rebel army leader against charges of war crimes. Their meetings take place in his cell, where he – at first silent – begins to communicate with his female lawyer. Through the process of defending him, the lawyer uncovers high-level political corruption, even implicating her own father. Despite their progress, the rebel continues to frequently and unpredictably burst out into violence. It again seemed to present a mixed message about reconciliation in a post civil-war landscape.

Exhibition, Ways We Watch Films in Africa, Edinburgh Filmhouse, 2015, Photo Credit: the author.

Exhibition, Ways We Watch Films in Africa, Edinburgh Filmhouse, 2015, Photo Credit: the author.Out with the film-programming, events as part of the 2015 festival included musical performances, storytelling, industry events, public debates and an exhibition in the Filmhouse cinema café, titled Ways We Watch Films in Africa. The works in the exhibition were selected through an open call, for ‘photographers, professional or amateur, to capture film-viewing habits across the African continent [and which brought submissions of] stunning images of street pop-up cinemas, crowded film parlors, mobile phone cinema, film festival screenings and more.’ The exhibition was displayed in a seating area aside to the main café space, in which an exhibition of vintage Polish cinema posters was being exhibited, in line with a concurrent festival. It felt very problematic to me, to be invited in a voyeuristic way from the comfort of the independent cinema space to look at the different ways in which ‘the African continent’ watches cinema. I say this especially when questions are raised regarding the place of an African film festival in Scotland, and the responsibility towards the infrastructure of African cinema on the continent that should come with screening these films in the West.

Criticisms have previously been directed at Africa-in-Motion and African film festivals in Europe more generally, and these have been responded to substantially. However many of the questions already posed are different to my own, which are in a sense questions about how Africa-in-Motion sits within its locality and immediate, visible actions that could be put in place. And so I conclude this review, looking back on ten years and projecting towards a future ten years, with my own series of questions: where has the previous space for experimental films gone; how can the organizational team of the festival be diversified; how can Africa-in-Motion (and the wider film network in Scotland) work to promote more African cinema in other film festivals and mainstream programming across Scotland; and what opportunities can Africa-in-Motion offer to PoC filmmakers in Scotland, especially young practitioners? There may not be a substantial number of filmmakers of color in Scotland, but if this is not encouraged and invested in, it is unlikely to change.

Scotland is a continent: Ten years of Africa-in-Motion

2015 marked the tenth anniversary of the Africa-in-Motion film festival, the showcase for African cinema in Scotland, which its director Lizelle Bischoff has described as being a wider, more-encompassing arts festival. The festival’s home has traditionally been the Edinburgh Filmhouse, an independent cinema in the city centre. From 2007 onwards, the festival began to take its programme to Glasgow, which is now a fully embedded element of the programme. These two cities combined are home to 32% of Scotland’s minority population, although Glasgow is the city most associated with diversity. The program has in the past gone on tour in rural parts of Scotland, and participated in UK-wide touring programs, such as 2014’s South Africa at 20.

The festival works across multiple venues, from academic spaces to pop-up venues, bars and, and community spaces. The festival is realized through an array of partnerships but principally funded through the arts council, Creative Scotland. The theme of 2015 was ‘Connections’ which was to be understood in a number of ways including ‘political connections, artistic collaborations, generational ties, lost and restored cultural links, and pan-Africanism.’ Additionally the ‘From Africa with Love’ strand featured a number of films and events programmed as part of the British Film Institute’s nationwide ‘Love’ season, and there were Nollywood industry events and premieres sponsored by the current British Council UK-Nigeria 2015/2016 initiative.

It might seem laborious to sketch out this kind of basic organizational framework here, but throughout my attendance of last year’s 10th edition, the question of how to review a film festival holistically was been at the forefront of my mind. In such a programming format and location, where I am seeing the film, who I am seeing it with, who is producing the program, who is and is not speaking to me, and who is funding it (and why) are all very present components of the experience. I am unsure whether it will be of interest to the readership of Africa is a Country, but certainly for me on an individual basis at least, the positioning and responsibilities of Africa-in-Motion in its local context are also primary concerns. I have been going to the festival over this ten year period, and so this review is inevitably informed by an experience accrued over that period. It is worth saying that without Africa-in-Motion, my access to African cinema in Scotland then and now would be limited.

The stand-out film at this year’s festival was Phillipe Lacôte’s Run. The film follows our protagonist through his three lives, which in the question and answer session the director revealed came from a conversation with a former member of the Young Patriots, often classed as a youth movement and militia, active in the recent civil wars in Côte d’Ivoire. Our central character, Run, lives up to his name, and from each of these three lives, he ends up running. In Run’s first life, he is an apprentice and named as successor to the village rainmaker. Despite the role of the rainmaker being all that Run dreamed and wished for, the village elders soon demand that he kill his teacher, which he refuses. Fleeing the scene, he is picked up on the road by Greedy Gladys, a professional eater, who takes Run on as her manager and emcee. Her show tours from town-to-town, in an eating competition to consume as much food onstage as the locals provide her with. Gladys is depicted as being from Burkina Faso – a ‘foreigner’ – a fact which is to play its part in her downfall.

Still from Run, Phillipe Lacôte, 2015, Ivory Coast.

Still from Run, Phillipe Lacôte, 2015, Ivory Coast.Lacôte discussed the film as being a portrayal of violence in the aftermath of the civil war, not yet able to discuss forgiveness and reconciliation. A major theme of the film was that of Ivoirité – a nationalistic term that took on xenophobic ideas during the civil war and was used as the basis to exclude the migrant population. I saw this aspect of the film as holding wider resonance, speaking to many nations worldwide currently struggling with the resurgence of right-wing movements and similar issues of rhetoric around nationhood and citizenship.

The opening film for the 2015 festival was Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Hyènes (Hyenas, 1992), which had previously been shown in the 2007 festival. It is undoubtedly a masterpiece and a satirical take on the relationship between post-independence Africa and neo-imperialism in a globalised, capitalist world. The film tells the story of Linguere Ramatou, an aging woman who returns to her home village of Colobane seeking revenge on her ex-lover. The film was programmed in the Love strand yet despite the storyline, I read this film as neither about love nor revenge. Whilst it is always a welcome opportunity to watch the classics of African cinema, the opening film defines the tone, and in this sense, I found Hyènes to be an unsuccessful choice as it sat awkwardly within this thematic context.

The following evening the programme continued with Samba Gadjigo and Jason Silverman’s biopic of Ousmane Sembène. Such a film is an important act and educational tool: a means to make the details of Sembène’s life accessible, public and to continue the process of historicising his contribution and output since his death in 2007. The film was split into thematic chapters, with short animated markers separating these out, which I found to interrupt the flow of the film. Initially, the film felt one-dimensional; very much in praise of the film-maker, and infact more a document of the biographer’s own relationship with the filmmaker than a document of Sembène himself. However towards the end, a more nuanced picture emerged, particularly through the interviews with his son and live-in housekeeper. His housekeeper was one of few female voices heard in this film; it is largely a film about a man, told by other men. Documentary footage is used of his second wife speaking about him whilst they were still married, his first wife is never named, and I found this female absence, somewhat ironically, very pervasive.

Still from Black Girl, Ousmane Sembène, 1966, Senegal.

Still from Black Girl, Ousmane Sembène, 1966, Senegal.Sembène! was followed by a Q&A session with producer and director Samba Gadjigo, before a screening of the filmmaker’s first feature film from 1966 La Noire de… Frequently translated into English as ‘Black Girl,’ the translation misses the significance of the ‘de,’ implying ownership. It was a real highlight of the festival; the copy screened a recently restored edition. Shot in black-and-white, the film is saturated in style and is equally poetic and melancholic. The story follows a young woman, Diouana, who obtains her first job as a nanny for a French family in Senegal who move back to France, taking her with them. Cooped up in their apartment on the French Riviera, she is maltreated by her employer and suddenly burdened with all the household chores. Receiving no pay to send home and cut off without communication with her family, she commits the ultimate act of defiance. Relatively short for a feature at 65 minutes in length, the film is perfectly paced, deftly communicating all it needed to say and more in its succinct duration.

Another film of note was Rwandan director Kivu Ruhorahoza’s Things of the Aimless Wanderer. The film is accomplished and beautifully shot, using only a BlackMagic Cinema Camera on this small budget production. It has an unconventional structure, divided between four ‘working hypotheses’ all merging into one another with no resolution. We follow at a distance three nameless central characters: a local man, a local woman and a white male foreigner. The foreigner is visiting whilst producing a travelogue, and gives the film its title ‘from Bantu accounts of early European explorers renowned for getting lost in their wanderings.’

Still from Things of the Aimless Wanderer, Kivu Ruhorahoza, 2015, Rwanda.

Still from Things of the Aimless Wanderer, Kivu Ruhorahoza, 2015, Rwanda.Described as being a deconstruction of ‘masculinity and territoriality’ and the ‘relations between “Locals” and Westerners… paranoia, mistrust and misunderstandings,’ it was set against the context of the Rwandan genocide by the director during the Q&A. A prominent point of discussion in the conversation afterwards was the silence of the female protagonist; unlike the two male characters, she speaks not one word during the entire film. There was a disjoint for me between how the director described her power and gender equality in Rwanda generally, and what I saw onscreen.

Mixed messages were overlaps in two of the films coming towards the end of the festival’s run, Dis Ek, Anna (It’s Me, Anna, 2015) and L’oeil du Cyclone (Eye of the Storm, 2015). Dis Ek, Anna follows a young girl Anna Bruwer, whose step-father sexually abuses her, eventually impregnating her, causing her as a teenager to flee the family home. Later, now working as a seamstress, she is found by her younger sister, who has suffered the same abuse and commits suicide that night in Anna’s home. In revenge, Anna returns to her childhood residence, and shoots dead her step-father. The film unfolds through flashbacks as Anna hands herself in at the station, discloses long-held secrets to her lawyer and psychologist, and in the duration of the court case. I found it difficult to balance this depiction of her harrowing childhood experience with the presence of certain privileges and the privileging of her narrative within the film and its South African context. Without money to pay for her lawyer, a schoolfriend turned lawyer steps forward (they later develop a relationship), she is bailed out of prison, accommodated in an apartment and sees two psychologists.

A second problematic narrative emerges, a sub-plot to Anna’s story, receiving a minority of screen time. The same police officer who first interviews Anna upon handing herself in is also investigating an instance of baby rape and murder in a black township. Despite the community knowing the perpetrator, a repeat offender, he is in hiding and protected. It was unclear to me whether this ‘sub-plot’ was within the original books or was added for this film adaptation. I think it is right that Anna’s experience was contextualised within the wider landscape of South Africa, but the manner in which this was done was very troubling. Furthermore both narratives here involved the rapists, killers and paedophiles being murdered, which I would consider to be an irresponsible message to send to audiences. At Africa-in-Motion the film was described as part of a new generation of Afrikaans filmmaking which also felt questionable.

In a similar vein, L’oeil du Cyclone tells the story of a defence lawyer, who successfully represents in court a rebel army leader against charges of war crimes. Their meetings take place in his cell, where he – at first silent – begins to communicate with his female lawyer. Through the process of defending him, the lawyer uncovers high-level political corruption, even implicating her own father. Despite their progress, the rebel continues to frequently and unpredictably burst out into violence. It again seemed to present a mixed message about reconciliation in a post civil-war landscape.

Exhibition, Ways We Watch Films in Africa, Edinburgh Filmhouse, 2015, Photo Credit: the author.

Exhibition, Ways We Watch Films in Africa, Edinburgh Filmhouse, 2015, Photo Credit: the author.Out with the film-programming, events as part of the 2015 festival included musical performances, storytelling, industry events, public debates and an exhibition in the Filmhouse cinema café, titled Ways We Watch Films in Africa. The works in the exhibition were selected through an open call, for ‘photographers, professional or amateur, to capture film-viewing habits across the African continent [and which brought submissions of] stunning images of street pop-up cinemas, crowded film parlours, mobile phone cinema, film festival screenings and more.’ The exhibition was displayed in a seating area aside to the main café space, in which an exhibition of vintage Polish cinema posters was being exhibited, in line with a concurrent festival. It felt very problematic to me, to be invited in a voyeuristic way from the comfort of the independent cinema space to look at the different ways in which ‘the African continent’ watches cinema. I say this especially when questions are raised regarding the place of an African film festival in Scotland, and the responsibility towards the infrastructure of African cinema on the continent that should come with screening these films in the West.

Criticisms have previously been directed at Africa-in-Motion and African film festivals in Europe more generally, and these have been responded to substantially. However many of the questions already posed are different to my own, which are in a sense questions about how Africa-in-Motion sits within its locality and immediate, visible actions that could be put in place. And so I conclude this review, looking back on ten years and projecting towards a future ten years, with my own series of questions: where has the previous space for experimental films gone; how can the organisational team of the festival be diversified; how can Africa-in-Motion (and the wider film network in Scotland) work to promote more African cinema in other film festivals and mainstream programming across Scotland; and what opportunities can Africa-in-Motion offer to PoC filmmakers in Scotland, especially young practitioners? There may not be a substantial number of filmmakers of colour in Scotland, but if this is not encouraged and invested in, it is unlikely to change.

February 28, 2016

It’s the economy stupid, N°3

On Twitter, T.O. Molefe announced that our new weekly series #ItsTheEconomyStupid is “My new favourite thing.” And you know, we love affirmation. So, here for T.O. and the rest of you is number 3.

(1) This week we read the transcribed version of an incredible speech given by Alex De Waal in Addis Ababa. The speech was given to the 2015/2016 Cohort of the Next Generation of Social Sciences in Africa fellows. In the speech, De Waal “outlines systematic problems with framings of African political and economic issues” by western academics working on Africa. He takes particular aim at economists and political scientists:

“[T]he state of knowledge about African economics and politics is poor because in the higher reaches of the western academies, the focus is not on generating accurate information, but on inferring causal associations at a high level of abstraction, from datasets. And that those datasets are in fact far too weak for any such conclusions to be drawn.

Second, the structure of academic rewards and careers systematically disadvantages those who either do not have the skills or capacities for this kind of high-end quantitative endeavor (although it is profoundly flawed), or have serious misgivings about it. One result of this is a severe dissonance between actual lived experience, and academic work validated by the academy.”

Frequent readers of Africa Is A Country know how much this bothers us.

(2) Relatedly, we are currently re-reading Charles Chukwuma Soludo’s and Thandika Mkandawire’s edited volume from 1999 “Our Continent, Our Future: African Perspectives on Structural Adjustment”. One of the recommendations of the book, based on the disastrous results of Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs), was a call for African voices to be at the front and center of development thinking about the continent. After all, many African intellectuals (economists, political scientists, civil society, etc…) opposed SAPs right from the beginning but their voices were drowned out.

Sadly, as demonstrated by De Waal’s speech above, little has changed in the 16 years since Soludo’s and Mkandawire’s important volume.

(3) In an attempt to preserve scarce foreign currency and help the struggling economy, authorities in Nigeria have embarked on a #BuyNaijaToGrowTheNaira Twitter campaign. If you (like us) can’t read hashtags, then what you simply need to know is that the campaign seeks to stop the free-fall of the Naira (Nigeria’s currency) by encouraging Nigerians to buy locally manufactured goods.

(4) Nigerian economist Nonso Obikili thinks the #BuyNaijaToGrowTheNaira strategy won’t work. And it’s not because most Nigerians are not on Twitter.

(5) To compound Nigeria’s economic woes, President Muhammadu Buhari in a meeting with the Islamic Development Bank in Saudi Arabia this past week said “the days of Nigeria as a big oil producer with plenty of money are gone”. He’s probably right. The price of oil, Nigeria’s biggest export, has fallen precipitously. There’s little hope that the price will recover anytime soon.

(6) The Zambian Parliament this past week approved an increase in the external debt ceiling from K60bn (about $6bn) to K160bn (about $14bn). The external debt ceiling should, in principle, limit how much external debt is accumulated by the government. However, this is the second time in under a year that the Zambian parliament has approved a lifting of the ceiling – this time around, the ceiling has more than doubled. This begs the question: why even have a ceiling if it’s going to be lifted anyway?

(7) This is the general problem of forcing the copying of what looks like a great thing from somewhere else in the world and pasting it in a place where the context is likely to be different. A parliament should offer checks. But how effective is this mechanism for offering checks if MPs, especially in some of our countries, tend to be easily “persuaded” to vote with the ruling party?

And we are almost 100% certain that an external clipboard-carrying consultant happily ticked-off “yes” on the questionnaire asking whether Zambia had a debt ceiling rule.

Thandika Mkandawire has called this copy and paste mentality “institutional monocroping”.

(8) We are not surprised by the obnoxiously high earnings of corporate executives in South Africa as revealed in the table below from Moneyweb (the table shows total annual earnings for executive directors whose companies are listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange).

Hendrik du Toit, Executive Director at financial services company Investec, received total annual compensation of R80million (we think this is for 2015 but Moneyweb doesn’t make it clear). For comparison’s sake, the most generous minimum wage stipulated for domestic workers in South Africa implies an annual pay of around R30,000. Do the math. Notice also how underrepresented certain demographic groups are on this list?

(9) More on inequality, a new publication called “The Origins of the Superrich: The Billionaire Characteristic Database” covered on the blog Conversable Economist finds that “extreme wealth is growing faster in emerging markets than in advanced countries”.

(10) One of the biggest concerns in applied economics (especially with Randomized Controlled Trials) is the issue of external validity. That is, are the results of obtained from a sample of households or villages in Kenya generalizable to the entire continent? Angus Deaton, winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in economics last year, doesn’t think they are. But are academic economists packaging their journal findings as if their results were generalizable? In other words, do academic economists think that Africa is a country?

David Evans over at the World Bank’s Development Impact Blog has crunched the numbers and doesn’t think so. We are convinced by Evans’ number crunching that Africa is mostly not a country for academic economists. But we wonder how many “policy consultants” or “policy-trepreneurs” are going round selling Rwanda’s evidence to Zambia or vice-versa. We can’t count the number of times we’ve sat in policy seminars or in policy meetings and someone has said “Malawi should do A because A works in Kenya”.

(11) Finally, last week we had much to say about the ambiguous impact of corruption on economic outcomes. Now comes a new book written by Kaushik Basu, who’s currently the World Bank’s Chief Economist and former economic advisor to the government of India, arguing that petty corruption saved India from experiencing the full brunt of the financial crisis.

February 26, 2016

Weekend Music Break No.92

It’s time again for another Weekend Music Break with Africa is a Country! Enjoy this round of tunes and visuals from the continent and its sphere of cultural influence.

The music thing that excited me most all week was coming to find out that Booba joined Sidiki Diabate on stage last December in Paris during his rendition of “Inianafi Debena“, and launched into a live mashup of that song and “Validée“, making all right in the world of Africa-Europe sampling/inspiration/dedication relations; another Bambara-themed hip hop collaboration, Kinté, Le Prince Héritier and Zarkawi Djatta are a revelation out of Cote d’Ivoire (h/t Afropop); Saharawi singer Aziza Brahim releases a video for “Calles de Dajla” to promote her latest album, and to celebrate her people still forced to live outside of their rightful land; A more explicit call to political action is embedded in the video for Jackson Wahengo’s “Eliko la Namibia”; Sammus delivers a sermon on higher education (and mental health) that I’m sure some Africa is a Country readers can relate to; Show Dem Camp, show up with a sunny love-pop video; Throes + The Shine add a third leg to their team up in the form of DRC via Montreal rapper Pierre Kwenders, on their song “Capuca”; the remix of YCEE’s monster hit “Jagaban” featuring Olamide, gets its own video to go alongside the original; I missed the video for this Samini and Popcaan collaboration from two years ago, so here it is now!; and finally, Runtown last year teamed up with Uhuru for a really smooth Naija and South Africa collaboration to take you into Sunday morning!

Happy Weekend!

February 25, 2016

Rearranging the furniture at Stellenbosch

Stellenbosch has been a crucial part of the decolonization drama that swept South Africa in 2015. The past year has highlighted how this town in the Western Cape struggles with the contradictions of its selective historical amnesia. Stellenbosch persists in allegorizing itself as a banal blend of pastoral and techno-futuristic progress, at the heart of which lies a university whose ivory tower is stained by its past incubation of Apartheid’s grand designers and its present parochial protection of white Afrikaans culture.

But while one narrative of the town’s history is proudly made visible via Cape Dutch buildings and old vineyards, there is an insidious will to forget the inconvenient meanings Stellenbosch has had historically. Nobody here wants to say too much about how the university incubated racists, or how the spatial politics of the town bear the very visible marks of forced removal and unjust dispossession. Beneath the narcotizing whitewashed farmers markets and the cack-handed gestures towards placing itself in the present, a deeper and more richly sedimented history lies buried.

This sediment is so deeply buried that it only seeps out when pressure is applied. 2015 was the year that political activism shook Stellenbosch’s windows and rattled its doors. Amid the wider seismic jolts experienced around South Africa, as the Rhodes Must Fall movement and other coterminous groups brought to the nation’s attention how many of our public spaces are decorated by problematic memorializations, Stellenbosch was not spared.

Indeed, Stellenbosch’s bewilderingly phantasmal position in the story white Afrikaans South Africa tells about itself was rudely jolted when students took to the streets. The town and the university’s cosy relationship with white Afrikaner nationalism means it harbours a particularly stubborn streak of ahistorical nostalgia for a glorious (misremembered) enterprising, resourceful and entrepreneurial white Afrikaans past, one in which the stories of Black and Coloured people formed desultory footnotes.

The conscious and unconscious claim of ownership lodged by white Stellenbosch was brought into uncomfortable conflict, then, during a year when the literal and figurative whiteness of the space was brought under extensive scrutiny. Given the sackcloth-and-ashes weeping that followed, it was easy to assume that this was the first time that anything might be termed “political” had disturbed the sleep of Stellenbosch’s privileged. What was happening was a vigorous disruption of the thuggish racialized mythmaking that dominated Stellenbosch’s cultural memory.

The measures to correct the misremembering that has shaped Stellenbosch have been vigorous, and equally vigorously contested by those who would have the town remain as it was: a paean to a South African history, a history those who defended it had claimed as unassailable. In ways that embarrassed and dismayed, the young and old rushed forward in demented and parochial ways to protect Stellenbosch as symbol. The rest is social media history.

What these developments demonstrate is the pervasive power that comes in occupying space, filling it with your symbols and shoring it up against loss. The currents of thought that sacralised racial separation in twentieth-century South Africa persist in places like Stellenbosch, though their exponents may have been excoriated. These currents do so because they are consecrated in museums, where things are exhibited until they cease to please, at which point they are relegated to storerooms.

Museum storerooms are their own exhibits, of course. They shelter things provisionally (the statue of Rhodes that was removed waits in a shrouded room), keeping what still has value for someone. The decision to archive a statue, a bust, or the myriad items that signal a lived history – a pen, a chair – is a curatorial one. When Stellenbosch University removed a plaque honouring HF Verwoerd from one of its buildings, it declared that the item would be lodged in the university archives:

The removal of the plaque forms part of the assessment of all visual elements and symbols on campus, among which the names of buildings, to determine obstacles in the path of unity that should be removed or contextualised.

Note the oddly neutered language (“visual elements and symbols”) that yields nothing (and thus a lot) of the university’s ideological position, and the banality of “the path of unity”, a path seemingly littered with historical bric-a-brac to trip up the unwary. The gloss misleads, drawing our attention away from the fact that these objects continue to be given safe harbour.

***

Greer Valley is a conceptual artist whose latest exhibit, The Chair, seeks to shift the logic structures that work to obscure Stellenbosch’s past. Currently running at the Sasol Museum until the end of February, The Chair performs the self-reflexive work of making visible what has been hidden from view for hundreds of years. Valley’s polemic takes particular aim at Stellenbosch University’s Museum, its displays and collections. The Chair presents alternative readings of these collections, the better to expose how museums collude in the foregrounding of certain kinds of knowledge production.

Valley’s installation opens up intriguing questions around how archives are conceived of, constructed and curated. In particular, the exhibition examines how material culture – the historical flotsam and jetsam that washes up on the shore of the present – is often encoded with non-neutral meanings, by constitutively derailing the artifacts so encoded. Valley’s installation forcefully foregrounds the intellectual indolence that lurks behind the ways that traditional African knowledge was defined as the vaguely monstrous Other of a supposedly civilized Europeanizing centre.

The installation asks what might be at stake when a museum draws delineations between Social Anthropology and Cultural History. In so doing, it challenges the processes that legitimized Apartheid and the regime’s supporting white Afrikaans histories at the expense of other cultural paradigms.

The exhibition opened on a balmy Stellenbosch night, with a performance by the Inzync collective, an ebullient outfit who perform their resistance to Stellenbosch’s conservatism via spoken-word poetry. The collective is part of a changing poetic economy in Stellenbosch, derailing the town’s solipsistic and narrowly defined ideas of what constitutes poetry. The four poets lead us through the exhibition, each of their poems a calling card that recontextualizes the violence of the original museum curations.

In the main room, a forbidding wooden table with a leather top dominates. A grey picture on the wall compels notice: white men, staring out at us. On one side of the table sits a chair that belonged to DF Malan – therein lies the name of the installation. It’s challenged by a traditional Nama carved stool, a thematic that runs throughout the installation. In another part of the room, emcee Adrian Different stages a rap battle against a bust of DF Malan. The performance of resistance via the figure of the emcee is particularly well-struck, connecting the histories of emceeing and rapping to this very white space.

What this exhibition has to say about objects is worth hearing. Malan’s chair – decentralized in the installation – is a site of meaning production. As Visual Arts lecturer Ernst Van der Wal argues, “It is a witness, it is a supporting object as it helped to upkeep and maintain a person and his ideologies at a certain time, and after that it was bestowed to this university with the idea that what he, Malan, as politician and bureaucrat did for South Africa was worthy of being protected, remembered and saved for posterity.”

The Chair exemplifies a broad social shift that compels us to look beyond the frames, that we might better see the set of structuring ideas at work behind the reordering of the historical shards. It does this with an invigorating urgency, drawing its animating impulse from the youthful politics coursing through South Africa’s veins.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers